Abstract

Bacillus methanolicus wild-type strain MGA3 secretes 59 g/liter−1 of l-glutamate in fed-batch methanol cultivations at 50°C. We recently sequenced the MGA3 genome, and we here characterize key enzymes involved in l-glutamate synthesis and degradation. One glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) that is encoded by yweB and two glutamate synthases (GOGATs) that are encoded by the gltAB operon and by gltA2 were found, in contrast to Bacillus subtilis, which has two different GDHs and only one GOGAT. B. methanolicus has a glutamine synthetase (GS) that is encoded by glnA and a 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) that is encoded by the odhAB operon. The yweB, gltA, gltB, and gltA2 gene products were purified and characterized biochemically in vitro. YweB has a low Km value for ammonium (10 mM) and a high Km value for l-glutamate (250 mM), and the Vmax value is 7-fold higher for l-glutamate synthesis than for the degradation reaction. GltA and GltA2 displayed similar Km values (1 to 1.4 mM) and Vmax values (4 U/mg) for both l-glutamate and 2-oxoglutarate as the substrates, and GltB had no effect on the catalytic activities of these enzymes in vitro. Complementation assays indicated that GltA and not GltA2 is dependent on GltB for GOGAT activity in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the presence of two active GOGATs in a bacterium. In vivo experiments indicated that OGDH activity and, to some degree, GOGAT activity play important roles in regulating l-glutamate production in this organism.

INTRODUCTION

The production of l-glutamate is a fast-growing industry, and approximately 2 million tons are produced annually, almost exclusively by Corynebacterium glutamicum fermentation using sugar-based raw materials (1). Genetic and biochemical insight into l-glutamate synthesis and degradation is of fundamental importance to understand nitrogen metabolism in the cells, as well as for metabolic engineering of l-glutamate overproduction. In C. glutamicum, l-glutamate is synthesized by both glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and glutamate synthase (GOGAT) (2), and l-glutamate overproduction can be achieved by downregulating the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) activity (3, 4).

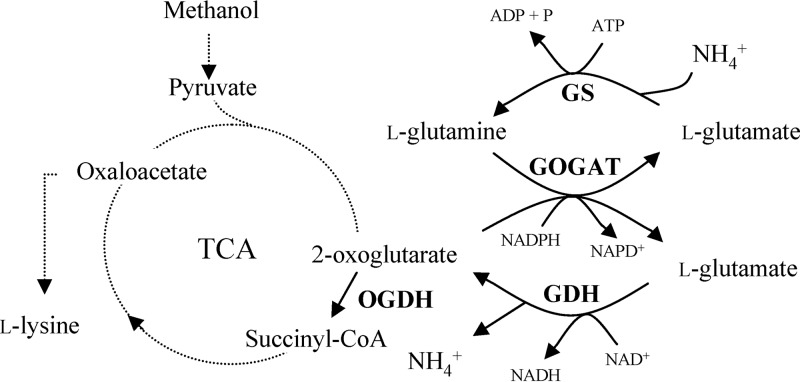

In Bacillus subtilis, the gltAB operon encodes the large (GltA) and the small (GltB) subunit of GOGAT. GOGAT catalyzes a reaction where the NH2 group from the amide group in l-glutamine is transferred to 2-oxoglutarate, forming two molecules of l-glutamate. Glutamine synthetase (GS) is encoded by glnA and catalyzes the synthesis of l-glutamine from l-glutamate and ammonia. Together, these two enzymes form the GOGAT/GS cycle (Fig. 1) that is responsible for ammonium assimilation and l-glutamate degradation and synthesis, and B. subtilis mutants deficient in GOGAT are l-glutamate auxotrophs (5, 6). To our knowledge, the kinetic properties of GOGAT in B. subtilis have not been reported in the scientific literature.

Fig 1.

The B. subtilis 2-oxoglutarate–glutamate–glutamine cycle. Enzymes: GS, glutamine synthetase; GOGAT, glutamine synthase; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; OGDH, oxoglutarate dehydrogenase.

B. subtilis harbors two genes, rocG and gudB, that both encode GDHs. In the most-studied B. subtilis strain, strain 168, GudB is found to be cryptic because of a 3-amino-acid duplication at the catalytic site that renders it nonfunctional (7). Other B. subtilis strains harbor genes encoding two active GDH enzymes (rocG and a version of gudB without the amino acid duplication). It has therefore been speculated whether the cryptic gudB gene is an adaption to growth under laboratory conditions (8, 9). Spontaneous mutants encoding active GudB, denoted GudB1, frequently form in B. subtilis 168 if rocG is inactivated, restoring GDH activity. In these mutants, the gudB gene is decryptified by the deletion of a 9-bp direct repeat which causes the amino acid duplication (7, 10). RocG and GudB1 are different from each other with respect to regulation and biochemical properties, where the expression of RocG is strictly regulated while GudB is constitutively expressed (7, 11). GDH in B. subtilis is devoted to the degradation of l-glutamate into 2-oxoglutarate and mainly thought to take part in the degradation of l-arginine (5). The expression of GDH and GOGAT is regulated as a response to both carbon and nitrogen availability.

In B. subtilis, the transcription of gltAB is dependent on the transcriptional activator GltC (12), the presence of 2-oxoglutarate and l-glutamine, and the absence of l-glutamate (13–15). RocG is expressed in the presence of l-arginine and in the absence of glucose (13), and it inactivates GltC by a direct protein-protein interaction (14, 16). Glutamine has an indirect role in gltAB regulation by affecting the affinity of TnrA for binding to DNA downstream from the gltAB promoter (for a review, see reference 17). TnrA is the global transcription factor for nitrogen metabolism in B. subtilis, and it represses the transcription of gltAB in the absence of l-glutamine (18). GDH and GS in B. subtilis both trigger enzymes involved in metabolic activities, as well as in gene regulation (19). GlnR is a transcriptional repressor encoded by the glnRA operon (20), and the trigger enzyme GlnA binds to GlnR and enhances its DNA affinity. The GlnR-GlnA complex represses its own transcription in addition to that of tnrA, regulating the l-glutamine and l-glutamate synthesis as a response to the l-glutamine availability (19).

Bacillus methanolicus is a thermotolerant and methylotrophic bacterium that has shown high potential as an alternative industrial producer of both l-glutamate and l-lysine from methanol (21, 22). We previously showed that the B. methanolicus wild-type strain MGA3 can produce up to 59 g/liter−1 of l-glutamate in fed-batch methanol cultivations at 50°C (23), and classical mutants secreting up to 65 g/liter−1 of l-lysine and only 28 g/liter−1 of l-glutamate (volume-corrected values) have been selected (23). Until now, genetic and biochemical knowledge of l-glutamate synthesis and degradation in B. methanolicus has been lacking. We recently reported the genome sequences of the B. methanolicus wild-type strains MGA3 and PB1 (24), and in the current study, we present a comprehensive characterization of genes and enzymes with assumed key roles for l-glutamate synthesis and degradation in B. methanolicus MGA3. The impact of our results for metabolic engineering aiming at both maximizing and controlling l-glutamate production is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological materials, DNA manipulations, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli DH5α (Stratagene) was used as the standard cloning host, while strain ER2566 (New England BioLabs) was used for recombinant protein expression. E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in liquid or solid LB medium (25) supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 g/liter−1) or chloramphenicol (10 mg/liter−1) when appropriate. Recombinant E. coli procedures were performed as described by Sambrook and Russell (25). DNA was amplified using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and DNA sequencing performed by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany). B. methanolicus was transformed by electroporation as described previously (26), and recombinant strains were selected on solid regeneration plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (5 mg/liter−1). For small-scale amino acid production, B. methanolicus cells were grown exponentially at 50°C in 100 ml of medium containing 200 mM methanol (MeOH200) in baffled 500-ml shake flasks to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 7 before harvesting (26). High l-glutamate production conditions were applied when appropriate and consisted of regular MeOH200 medium, where the MgSO4 concentration was reduced to 0.15 mM and the medium supplemented with 40 mM sodium acetate. B. subtilis was transformed as previously described (27), and recombinant colonies selected on solid tryptose blood agar base plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (5 mg/liter−1). Complementation experiments in E. coli or B. subtilis strains were done using M9 minimal medium agar plates containing 0.4% glucose as described elsewhere (6, 28, 29).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. methanolicus MGA3 | Wild-type strain ATCC 53907 | ATCC |

| B. methanolicus M168-20 | 1st-generation AEC-resistant mutant of MGA3; l-lysine overproducer | 23 |

| E. coli DH5α | General cloning host | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| E. coli ER2566 | Carries chromosomal gene for T7 RNA polymerase | New England Biolabs |

| E. coli EB4613 | gltD mutant (glutamate synthase deficient) | 29 |

| E. coli JW3841 | glnA 732 del | Keio Collections 28 |

| B. subtilis GP650 | gltC mutant | 14 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHP13 | E. coli-B. methanolicus shuttle vector, Cmr, 4.7 kb | 26, 42 |

| pGEM-T | E. coli cloning vector, Apr, 3 kb | Promega |

| pET21a | E. coli expression vector, His6 tag, T7 promoter, Apr, 5.4 kb | Novagen |

| pET21a-yweB | pET21a derivative with the MGA3 yweB gene PCR amplified and cloned into the NdeI-XhoI sites, Apr, 6.6 kb | This study |

| pET21a-gltA | pET21a derivative with the MGA3 gltA gene PCR amplified and cloned into the NdeI-XhoI sites, Apr, 9.9 kb | This study |

| pET21a-gltA2 | pET21a derivative with the MGA3 gltA2 gene PCR amplified and cloned into the NdeI-XhoI sites, Apr, 9.8 kb | This study |

| pET21a-gltB | pET21a derivative with the MGA3 gltB gene PCR amplified and cloned into the NdeI-XhoI sites, Apr, 5.5 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-yweB | pHP13 carrying yweB coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 7.1 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-glnA | pHP13 carrying the glnA coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 7.2 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-gltAB | pHP13 carrying the gltAB coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 12 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-gltA | pHP13 carrying the gltA coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 11.3 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-gltA2 | pHP13 carrying the gltA2 coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 10.3 kb | This study |

| pTH1mp-odhAB | pHP13 carrying the odhAB coding region, under control of the mdh promoter, Cmr, 10 kb | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Vector construction. (i) pTH1-based vectors for overexpression in B. methanolicus and for complementation of B. subtilis mutant strains.

In order to facilitate the cloning of the large, 6-kb gltAB operon, 3 primer pairs were used to amplify the whole sequence from B. methanolicus MGA3 genomic DNA, 5′-TTTTACATGTGAAACATTATGGACTACCG-3′ and 5′-ACGCTTTTTGCAATGTGACAAG-3′ (1.3 kb, PciI recognition site underlined), 5′-CCTTACCGTAAATGGCTGAACG-3′ and 5′-GGCGTCGCGATCAACATTTCG-3′ (2.3 kb, XbaI and PstI), and 5′-ATTTGCTCGTCCGCAGCAGC-3′ and 5′-TTTTGGTACCAACCATATTTCAGCAGTTCCTTTGG-3′ (2.5 kb, KpnI recognition site underlined). The PCR products were ligated directly into the T/A cloning vector pGEM-T (Promega) and verified by sequencing. The gltAB fragments were then isolated from the respective vectors by XbaI and PciI, XbaI and PstI, and PstI and KpnI digestion, respectively, and collectively ligated into the compatible PciI and KpnI sites of pTH1mp-lysC (replacing the lysC gene), generating the expression vector pTH1mp-gltAB. The pTH1mp-gltAB vector was used in the construction of the pTH1mp-gltA vector. Digesting pTH1mp-gltAB with MscI resulted in fragments of 11.3 kb and 0.7 kb, and the larger fragment was purified and religated to form the plasmid pTH1mp-gltA.

The gltA2, odhAB, glnA, and yweB coding sequences were PCR amplified from B. methanolicus MGA3 total DNA using the following primer pairs: 5′-TTTTACATGTGACCAAGCAATGGAGTCCTTCTGT-3′ and 5′-TTTTGGTACCTTATTCTGTTGAAACAGACGGATCT-3′ (gltA2, 4.5 kb, PciI and KpnI recognition sites underlined, respectively), 5′-TTTTACATGTATGATAAAGCCTTCAATCGGTC-3′ and 5′-TTTTTCTAGAAATCGGATATCCAAATTGCC-3′ (odhAB, 4.1 kb, PciI and XbaI recognition sites underlined, respectively), 5′-TTTTACATGTGATAACAGGGAGGACAAC-3′ and 5′-TTTTTCTAGAACACCAATGGTGTCAAGGG-3′ (glnA, 1.4 kb, PciI and XbaI recognition sites underlined, respectively), and 5′-TTTTCGTCTCACATGTTTAGGAGGTTTACAAATG-3′ and 5′-TTTTGAATTCATTCAATTATTAAACCC-3′ (yweB, 1.3 kb, Esp31 and EcoRI recognition sites underlined, respectively). The odhAB, glnA, and yweB PCR products were A/T ligated directly into pGEM-T, and the inserts verified by sequencing. The pGEM-T derivatives were then digested by PciI and XbaI (odhAB and glnA) or Esp3I and EcoRI (yweB), where Esp3I creates ends compatible with PciI, and the inserts subcloned into the corresponding sites of pTH1mp-lysC (replacing the lysC gene), yielding pTH1mp-odhAB, pTH1mp-glnA, and pTH1mp-yweB. The gltA2 PCR product was digested by PciI and Acc65I and ligated into the corresponding site in pTH1mp-lysC (replacing the lysC gene), yielding plasmid pTH1mp-gltA2. The insert was then verified by sequencing.

(ii) His6-tagged expression vectors for glutamate dehydrogenase and the glutamate synthases.

The coding regions of yweB, gltA, gltA2, and gltB were PCR amplified from B. methanolicus MGA3 total DNA by using the following PCR primer pairs: 5′-AAACATATGGTAGCCGAGAACGGT-3′ and 5′-AAACTCGAGAACCCAGCCTCTGAACCT-3′ (yweB, 1.3 kb, NdeI and XhoI recognition sites underlined, respectively), 5′-TTTTCATATGAAACATTATGGACTACC-3′ and 5′-TTTTCTCGAGTTTAGCGACCGCTTGTAATG-3′ (gltA, 4.6 kb, NdeI and XhoI recognition sites underlined, respectivel), 5′-TTTTCATATGACCAAGCAATGGAGT-3′ and 5′-TTTTCTCGAGTTCTGTTGAAACAGACGG-3′ (gltA2, 4.5 kb, NdeI and XhoI recognition sites underlined, respectively), and 5′-TTTTCATATGGGAAAAGTAACAGGATTT-3′ and 5′-TTTTCTCGAGCGGCAAATTCGTTGTTC-3′ (gltB, 1.5 kb, NdeI and XhoI recognition sites underlined, respectively). The resulting DNA fragments were A/T ligated directly into pGEM-T, and the inserts verified by sequencing. All the pGEM-T derivatives were digested completely by XhoI. The yweB and gltA2 pGEM-T derivatives were also digested completely by NdeI, while the gltA and gltB pGEM-T derivatives were partly digested by NdeI before the full-length genes were subcloned into the corresponding sites of the expression vector pET21a, in frame with the His6 tag sequence, yielding pET21a-yweB, pET21a-gltA, pET21a-gltA2, and pET21a-gltB, respectively. All the constructed vectors were then transferred into the expression host E. coli ER2566.

Affinity purification and enzymatic assays of GDH and GOGAT.

The B. methanolicus genes gltA, gltA2, gltB, and yweB were expressed in recombinant E. coli ER2566 cells harboring plasmids pET21a-gltA, pET21a-gltA2, pET21a-gltB, and pET21a-yweB, respectively, and the gene products were purified from cell extracts essentially as described previously (30). Protein concentrations were estimated spectrophotometrically in a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies), with molecular weight and extinction coefficient settings calculated for the proteins using the ExPASy Prot Param tool (expasy.org/tools/protparam.html) (31). The protein concentrations were as follows: YweB, 8 μg/μl; GltA, 1 μg/μl; GltB, 6 μg/μl; and GltA2, 2 μg/μl. The purity of the proteins was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (25). The purified proteins were snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until they were thawed on ice and used in biochemical analyses.

The GOGAT and GDH enzyme activities were measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the production or consumption of NADH/NADPH. The GOGAT assay mixture generally contained 100 mM glycine-KOH, pH 8.5, 20 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 20 mM l-glutamine, 5 mM MgSO4, and 0.25 mM NADPH, while the GDH assay mixture generally contained 100 mM glycine-KOH, pH 8.0, 50 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 100 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MgSO4, and 0.2 mM NADH for the amination reaction and 100 mM glycine-KOH, pH 8.5, 200 mM l-glutamate, 10 mM MgSO4, and 0.2 mM NAD+ for the deamination reaction. The assay components were mixed in a quartz cuvette and prewarmed to 45°C. The reactions were started by the addition of 0.1 ml enzyme, yielding a total volume of 1 ml, and the production or consumption of NADH/NADPH was monitored at 340 nm for 4 min. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to produce/consume 1 μmol NADH/NADPH per minute under the conditions described above.

Kinetic characterization (Km/Vmax) of the purified YweB, GltA, and GltA2 proteins.

The kinetic parameters for both the amination and deamination reactions were determined for YweB. In the amination reaction, when determining the Km for 2-oxoglutarate, the ammonium and NADH were kept at saturation (50 mM and 0.2 mM, respectively) while the 2-oxoglutarate concentration was varied (1 to 200 mM). When determining the Km for ammonium, the 2-oxoglutarate and NADH levels were kept at saturation (50 mM and 0.2 mM, respectively) while the ammonium concentration was varied (1 to 150 mM). In the deamination reactions, when determining the Km for l-glutamate, the NAD+ level was kept at saturation (0.2 mM) while the l-glutamate concentration was varied (2 to 1,000 mM). The Km and Vmax values for 2-oxoglutarate, ammonium, and l-glutamate were calculated by using nonlinear regression with the Microsoft Excel solver tool to fit the measured data to the Michaelis-Menten equation, as described previously (30). The GDH reaction was found not to follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and the Km values for 2-oxoglutarate, ammonium, and l-glutamate could not be accurately determined by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Instead, nonlinear regression was applied and the results compared visually to plots of the reaction rate versus the substrate concentration. By using a definition of Km as the substrate concentration giving the reaction rate 1/2 Vmax, the Km values for l-glutamate, ammonium, and 2-oxoglutarate were estimated.

The kinetic constants for GltA and GltA2 were also found, and when determining the Km for 2-oxoglutarate, the l-glutamine and NADPH levels were kept at saturation (10 mM and 0.25 mM, respectively) while the 2-oxoglutarate concentration was varied (0.1 to 10 mM). When determining the Km for l-glutamine, the 2-oxoglutarate and NADPH levels were kept at saturation (10 mM and 0.25 mM, respectively) while the l-glutamine concentration was varied (0.1 to 10 mM). The Vmax and Km values for 2-oxoglutarate and l-glutamine for GltA and GltA2 were calculated by using nonlinear regression with the Microsoft Excel solver tool to fit the measured data to the Michaelis-Menten equation, as described previously (30). The values obtained from the regression were then compared to the values obtained from Lineweaver-Burk plots.

Preparation of cell-free B. methanolicus extracts and measurement of OGDH activity.

MeOH200 medium (100 ml) was inoculated with 0.25 ml thawed cells from frozen ampoules in three replicates and grown exponentially until the OD600 was 2.5 to 3.3. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in 4 ml potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5), and resuspended in 3 ml of the same buffer to give an OD600 of ∼9. Cell extracts were prepared as previously described (26). Enzyme assays were performed as follows: the enzyme activity in a total volume of 1 ml was assayed, and the reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.75), 0.25 mM NAD+, 50 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 1 mM coenzyme A (CoA), 1 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 3 mM l-cysteine-HCl, and 1 mM MgCl2. The reaction mixture was prewarmed to 45°C, and the reaction was initiated by adding 100 μl of cell extract. The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (A340) due to oxidation of NADH was monitored spectrophotometrically in a quartz cuvette over a 4-min period at 45°C. The background activity from the cell extract was measured by adding all components but 2-oxoglutarate, and the background activity subtracted from the total activity. The total protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad), using bovine serum albumin as the reference protein.

Determination of amino acid concentrations.

Amino acid concentrations were measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HLPC) essentially as previously described (26, 32). In brief, 0.8 ml cells were mixed with 0.2 ml sulfosalicylic acid (10%). The mixture was then diluted with 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to reach appropriate concentrations for the HPLC analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of genes with putative key roles in the synthesis and degradation of l-glutamate in B. methanolicus MGA3.

Inspection of the B. methanolicus MGA3 genome sequence (24) identified genes putatively encoding GDH (yweB), GS and its transcriptional repressor GlnR (glnRA), OGDH (odhAB operon), and two alternative GOGATs (gltAB operon and gltA2) (Table 2). The gltAB operon is colocalized with gltC, putatively encoding a LysR-type transcriptional activator of the gltAB operon, similar to B. subtilis (12), while the gltA2 gene is located elsewhere on the chromosome. Some bacterial species, including (with GenBank accession numbers in parentheses) Geobacillus klaustophilus (YP_147284 ), Geobacillus thermodenitrificans (YP_001125407 ), Bacillus licheniformis (AAU41048 ), Bacillus subtilis (AEP91025 ), Bacillus megaterium (AEN90044 ), and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (AEB23717 ), harbor the GltA variant exclusively, while other bacteria, such as Bacillus cellulosilyticus (YP_004093989 ), Bacillus pseudomycoides (EEM18769 ), Bacillus mycoides (EEM12809 ), Bacillus cereus (EEK75106 ), and Bacillus thuringiensis serovar Finitimus (ADY19828 ) harbor the GltA2 variant exclusively. Genes encoding both the GltAB and GltA2 variants of GOGAT were found in certain thermophilic bacilli, more specifically, Geobacillus sp. Y4.1MC1 (NC_014650 ), Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius C56-YS93 (NC_015660 ), Geobacillus sp. WCH70 (NC_012793 ), and Anoxybacillus flavithermus WK1 (NC_011567 ). To our knowledge, the functions and activities of these two alternative GOGATs have not been confirmed experimentally in any of the latter organisms.

Table 2.

Key genes and regulatory genes putatively involved in l-glutamate synthesis and degradation in B. methanolicus MGA3a

| Feature of strain MGA3 | Common name | Gene | EC no. | Amino acid identity (%) to protein of: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. methanolicus PB1 | B. subtilis 168 | ||||

| Key genes | |||||

| MGA3_06345 | Dihydrolipoyllysine residue succinyltransferase | odhB | 2.3.1.61 | 89 | 68 |

| MGA3_06350 | Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (succinyl transferring) | odhA | 1.2.4.2 | 83 | 61 |

| MGA3_08930 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | yweB | 1.4.1.2 | 96 | 76/89b |

| MGA3_10580 | Glutamate synthase (NADPH) | gltA2 | 1.4.1.13 | 92 | 28 |

| MGA3_12285 | Glutamate synthase (NADPH) | gltB | 1.4.1.13 | 96 | 75 |

| MGA3_12290 | Glutamate synthase (NADPH) | gltA | 1.4.1.13 | 96 | 71 |

| MGA3_15011 | Glutamine synthetase, type I | glnA | 6.3.1.2 | 98 | 85 |

| Regulatory genes | |||||

| MGA3_11185 | Transcriptional pleiotropic regulator involved in global nitrogen regulation | tnrA | 93 | 60 | |

| MGA3_12295 | Transcriptional activator of the glutamate synthase operon | gltC | 96 | 68 | |

| MGA3_14511 | Transcriptional pleiotropic repressor | codY | 99 | 88 | |

| MGA3_15006 | Transcriptional repressor of the glutamine synthetase | glnR | 94 | 64 | |

See reference 24.

Identities toward B. subtilis RocG and GudB, respectively.

B. methanolicus has only one gene putatively encoding GDH, yweB, in contrast to B. subtilis, which has two genes, rocG and gudB, both encoding GDHs with different catalytic properties (7–9). An odhAB operon putatively encoding the E1 (OdhA) and E2 (OdhB) subunits of the OGDH complex was identified, similar to B. subtilis (Table 2) (24, 33). OGDH catalyzes the conversion of the l-glutamate precursor 2-oxoglutarate into succinyl-CoA (Fig. 1) and further degradation in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and odhAB was therefore included in the current investigations. In addition, a number of regulatory genes (tnrA, codY, gltC, and glnR) that are putatively involved in l-glutamate degradation and synthesis were identified in MGA3 (24); however, they were not the focus of the current study.

Functional confirmation of gltAB and glnA by complementation of auxotrophic Escherichia coli and B. subtilis mutants.

The E. coli mutants EB4613 and JW3841 are defective in GOGAT and GS, respectively, rendering them l-glutamate and l-glutamine auxotrophs, respectively (28, 29). In the B. subtilis mutant GP650, the gltAB operon is not expressed due to a mutation in the transcriptional activator gene gltC (14), rendering this strain an l-glutamate auxotroph. The B. methanolicus gltAB operon and glnA gene were cloned in the expression vector pTH1mp under the control of the strong methanol dehydrogenase (mdh) promoter (23). The resulting pTH1mp-gltAB plasmid was transferred into strains EB4613 and GP650, while the pTH1mp-glnA plasmid was transferred into strain JW3841. The strains EB4613(pTH1mp-gltAB), GP650(pTH1mp-gltAB), and JW3841(pTH1mp-glnA) were then tested for growth properties in defined media (see Materials and Methods). EB4613(pTH1mp-gltAB) and GP650(pTH1mp-gltAB) regained the ability to grow on plates without l-glutamate supplementation, showing that the B. methanolicus gltAB operon can complement the defective GOGAT genes in the mutant EB4613 and glutamate synthesis in strain GP650. Similarly, JW3841(pTH1mp-glnA) grew well without l-glutamine supplementation, confirming that the B. methanolicus glnA gene was able to complement the defective GS gene in this E. coli strain. The EB4613, JW3841, and GP650 strains carrying the empty vector pHP13 were used as controls, and these strains could not grow without l-glutamate or l-glutamine supplementation, respectively.

YweB is an active GDH with a high Km value for l-glutamate (250 mM) and low Km values for ammonium (10 mM) and 2-oxoglutarate (20 mM) in vitro.

GDH catalyzes the reductive amination of 2-oxoglutarate and, together with GOGAT, is involved in the synthesis and degradation of l-glutamate in bacteria (for a review, see reference 17). B. subtilis RocG has been reported to have low Km values for l-glutamate (0.65 mM) and 2-oxoglutarate (0.56 mM) and a much higher Km value for ammonium (55.6 mM) (34). In a separate study, the Km values for RocG and the decryptified GudB for l-glutamate were reported to be 2.9 mM and 17.9 mM, while the Km values for these two proteins for ammonium were 18 mM and 41 mM, respectively (35). Together, these data have been used to argue that both these GDHs are mainly catabolic enzymes involved in l-glutamate degradation in B. subtilis, which is in good agreement with experiments showing that the active versions of the two B. subtilis GDHs do not contribute significantly to l-glutamate synthesis (5). To obtain analogous data on the B. methanolicus YweB, the yweB gene was expressed recombinantly in E. coli, purified, and subjected to kinetic characterization. The purified YweB displayed a high Km value for l-glutamate (250 mM) and much lower Km values for ammonium (10 mM) and 2-oxoglutarate (20 mM). The Vmax values were 1.4 U/mg and 10 U/mg for the deamination (l-glutamate degradation) and the amination (l-glutamate synthesis) reactions, respectively (Table 3). The high Km value for l-glutamate, together with its low Vmax value for the deamination reaction (1.4 U/mg) (Table 3), make it questionable whether YweB plays an important role in l-glutamate degradation in B. methanolicus MGA3 or if it rather has a key role in l-glutamate synthesis. In C. glutamicum, GDH has much higher affinities for ammonium and 2-oxoglutarate than for l-glutamate (2), and it is considered to contribute to l-glutamate synthesis at high ammonium concentrations (5, 36). In an attempt to investigate this experimentally, the B. methanolicus yweB gene was cloned into the expression vector pTH1mp under the control of the mdh promoter (Table 1), and the resulting plasmid was transformed to the gltC mutant B. subtilis strain GP650 (see above). The resulting strain, GP650(pTH1mp-yweB), was tested for growth in defined medium using NH4Cl as a nitrogen source. No growth was observed without l-glutamate supplementation, while normal growth was observed when l-glutamate was supplied. The latter data indicated that yweB cannot complement l-glutamate synthesis in this B. subtilis host under the conditions tested. This result was not in agreement with the predicted role of YweB based on the kinetic properties in vitro (see above), and the biological reason for this discrepancy is unknown.

Table 3.

Biochemical properties of the B. methanolicus YweB protein on different substrates in vitroa

| Substrate | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| l-Glutamate | 250 | 1.4 |

| Ammonium | 10 | 10 |

| 2-Oxoglutarate | 20 | 10 |

The YweB protein was expressed recombinantly in E. coli, purified, and subjected to kinetic characterization (see Materials and Methods).

Both GltA and GltA2 are active GOGATs with similar Vmax and Km values for l-glutamine and 2-oxoglutarate in vitro.

GOGAT catalyzes the formation of two molecules of l-glutamate from l-glutamine and 2-oxoglutarate (Fig. 1) (17). The strain MGA3 gltA, gltB, and gltA2 genes were expressed recombinantly in E. coli, and the respective gene products were purified and characterized biochemically in vitro. Both GltA and GltA2 displayed a Km value of 1.0 mM for 2-oxoglutarate, and the Km values for l-glutamine were also similar and in the same range (1.3 mM and 1.4 mM, respectively). The Vmax value for both proteins was 4 U/mg, tested with both alternative substrates (Table 4). These data confirmed that both proteins are active GOGATs with similar kinetic properties under the conditions tested. The catalytic activities of GltA and GltA2 were dependent on the presence of both glutamine and 2-oxoglutarate. The presence of GltB had no effect on the enzymatic activities of GltA and GltA2, and in addition, GltB did not show any catalytic activity when assayed alone (data not shown). To our knowledge, this is the first description of bacteria harboring genes encoding two active GOGATs and, also, the first kinetic characterization of GOGAT enzymes from any of the bacilli.

Table 4.

Biochemical properties of the B. methanolicus MGA3 GltA and GltA2 proteins on different substrates in vitro

| Substrate | GltA |

GltA2a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | |

| l-Glutamine | 1.3 | 4 | 1.4 | 4 |

| 2-Oxoglutarate | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

Purified GltB protein was not found to have any enzymatic activity alone or in combination with GltA or GltA2 under the conditions tested (see the text).

To investigate this further, we performed complementation assays by using the E. coli gltD mutant strain EB4613 and the B. subtilis gltC mutant strain GP650 (Table 1) as hosts. The gltAB, gltA, and gltA2 coding regions were cloned into the expression vector pTH1mp under the control of the mdh promoter, and the resulting plasmids, pTH1mp-gltAB, pTH1mp-gltA, and pTH1mp-gltA2, were transferred into the two host strains. The resulting strains, GP650(pTH1mp-gltAB), GP650(pTH1mp-gltA), GP650(pTH1mp-gltA2), EB4613(pTH1mp-gltAB), EB4613(pTH1mp-gltA), and EB4613(pTH1mp-gltA2), were tested for growth on minimal medium with NH4Cl as the only nitrogen source. The recombinant strains expressing gltAB and gltA2 displayed normal growth without l-glutamate supplementation, while the recombinant strains expressing gltA did not grow under these conditions. These data confirm that GltA2 and GltAB are active GOGATs in vivo. Interestingly, GltA alone presumably has no such activity in vivo, confirming that GltB is required under such conditions. The latter result was in disagreement with the analogous in vitro data, and the biological reason for this remains unknown.

The gltAB operon in B. subtilis is transcriptionally activated by GltC in the presence of 2-oxoglutarate and absence of l-glutamate (12, 14, 37). It is likely that the B. methanolicus gltAB operon is regulated by gltC, but whether the transcription of gltA2 is regulated by the gltAB-colocalized gltC gene is more questionable. GltC-independent gltA2 transcription could possibly facilitate l-glutamate synthesis under conditions where the intracellular level of l-glutamate is normally too high for gltAB transcription. This might be one important factor explaining how MGA3 is able to accumulate such high l-glutamate levels (23, 32). However, the latter hypothesis needs to be tested experimentally, and this was not within the scope of the current study.

Overexpression of GltAB, GltA2, GltA, GlnA, and YweB had marginal or no effect on l-glutamate production in B. methanolicus MGA3 shake flask cultures.

We previously showed that overexpression experiments can be used to efficiently analyze the role and regulation of a number of genes in the l-lysine biosynthetic pathway in B. methanolicus (30, 38). Here, we used an analogous approach to map the roles of the gltAB, gltA, gltA2, glnA, and yweB genes. The genes were individually cloned into the pTH1mp vector under the expressional control of the strong methanol dehydrogenase promoter (26, 39) and transferred to MGA3. The resulting recombinant strains were grown in shake flasks in methanol medium, and samples were collected for l-glutamate measurements during the growth period as described previously (38). MGA3(pHP13) was included as a control, and this strain secreted 0.8 g/liter−1 of l-glutamate (Table 5). Strains MGA3(pTH1mp-yweB) and MGA3(pTH1mp-glnA) both produced l-glutamate at the same level (0.8 g/liter−1) as the control strain (Table 5). Strains MGA3(pTH1mp-gltAB) and MGA3(pTH1mp-gltA2) secreted 1.1 g/liter−1 of l-glutamate, which is slightly higher (about 1.4-fold) than the control strain. Interestingly, l-glutamate production by MGA3(pTH1mp-gltA) was similar to that in the control strain, which implies that GltB is needed together with GltA for GOGAT activity in vivo (Table 5). The latter result was in contrast to the analogous in vitro results, which could not assign any role of GltB for GOGAT activity (see above), and the reason for this discrepancy is unclear. Although the yields obtained under the conditions tested are low compared to analogous data obtained in high-cell-density cultivations (18, 25, 27), these data may suggest that GOGAT activity represents one bottleneck for increased l-glutamate overproduction by B. methanolicus MGA3 under these conditions. The biological significance of these results for l-glutamate overproduction under industry-relevant fed-batch fermentations remains to be tested, as this was not within the scope of the current study.

Table 5.

l-Glutamate and l-lysine yields obtained in methanol shake flask cultures of recombinant B. methanolicus strainsa

| Plasmid | Overexpressed gene(s) | Host strain | Mean yield (g/liter−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Glutamate | l-Lysine (g/liter−1) | |||

| pHP13 | No gene | MGA3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-gltAB | gltAB | MGA3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-gltA | gltA | MGA3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-gltA2 | gltA2 | MGA3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-yweB | yweB | MGA3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-glnA | glnA | MGA3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ND |

| pTH1mp-odhAB | odhAB | MGA3 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | ND |

| pHP13 | No gene | M168-20 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| pTH1mp-odhAB | odhAB | M168-20 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

Recombinant strains were grown in shake flasks in methanol medium, and samples were collected for amino acid analyses (see Materials and Methods). Maximum production levels are given, and standard errors are indicated. ND, not determined.

OGDH activity plays a key role in regulating l-glutamate synthesis in B. methanolicus MGA3.

2-Oxoglutarate is located at the important branching point of the TCA cycle where it can be converted to l-glutamate or, alternatively, to succinyl-CoA by the OGDH complex (Fig. 1). Control of the OGDH activity plays a key role in achieving overproduction of l-glutamate in C. glutamicum (3, 4, 40). Reducing the OGDH activity will change the flux at the 2-oxoglutarate branching point toward the synthesis of l-glutamate and a concomitant reduced flow of carbon through the TCA cycle. Many methylotrophic bacteria lack a complete TCA pathway (41), and our previous attempts to detect OGDH activity in B. methanolicus MGA3 crude extracts have failed (32). Therefore, to verify the function of the odhAB operon, the pTH1mp-odhAB vector (Table 1) was constructed and transferred to MGA3, and cell extracts of MGA3(pTH1mp-odhAB) were prepared and assayed for OGDH activity. MGA3(pHP13) displayed low OGDH activity (below 0.001 U/mg), while the OGDH activity in MGA3(pTH1mp-odhAB) was 0.015 U/mg, demonstrating that odhAB encodes an active OGDH. Interestingly, the l-glutamate secretion by MGA3(pTH1mp-odhAB) was 8-fold reduced (0.1 g/liter−1) compared to that in in the control strain in shake flask cultivations (Table 5). This result indicates that odhAB represents a key target for manipulations aiming at regulating l-glutamate production in B. methanolicus MGA3.

OGDH overexpression resulted in 5-fold-reduced l-glutamate production and 2-fold-increased l-lysine production in the AEC-resistant B. methanolicus mutant M168-20.

The high potential of B. methanolicus to overproduce both of the amino acids l-glutamate and l-lysine from methanol has been reviewed by us (21). While l-glutamate is a side product of the TCA cycle, l-lysine belongs to the aspartate family of amino acids. Thus, these two amino acids are products of competing biochemical pathways from the common precursor metabolite oxaloacetate (OAA). For the development of efficient l-lysine overproducers, it will be important to diminish wasteful l-glutamate production (32). We previously showed that the overexpression of pyruvate carboxylase activity in the S-(2-amino-ethyl)cysteine (AEC)-resistant, homoserine dehydrogenase 1 (hom1)-deficient, and l-lysine-overproducing MGA3 mutant host strain M168-20 (23) resulted in slightly reduced l-glutamate synthesis. However, this manipulation had no positive effect on the l-lysine production (23). Our results (see above) suggest that the overexpression of OGDH results in an overall increase in TCA activity, eventually leading to an increased OAA supply in the cells. It was therefore of interest to test whether odhAB overexpression might be beneficial for l-lysine production in host M168-20. The recombinant strain M168-20(pTH1mp-odhAB) was established, and analysis in shake flasks demonstrated that it displayed 5-fold-reduced l-glutamate production (0.1 g/liter−1) and about 2-fold-increased l-lysine production (0.24 g/liter−1) compared to the levels in the control strain M168-20(pHP13). It was plausible to assume that the increased OGDH activity resulted in an increased OAA supply in the cells under the conditions tested, which is in favor of l-lysine production.

Concluding remarks.

In this report, three genes (gltA2, yweB, and glnA) and two operons (gltAB and odhAB) encoding key enzymes with roles in l-glutamate metabolism in B. methanolicus MGA3 were investigated. The predicted functions of all gene products were experimentally verified, and by combining biochemical data in vitro with biological roles in vivo, we have obtained new insight into the genes and enzymes involved in l-glutamate synthesis and degradation in this organism. In contrast to the genetically related B. subtilis, B. methanolicus has two active GOGATs and only one GDH, and our combined results indicate that all three proteins are important for l-glutamate synthesis in B. methanolicus. We show that l-glutamate production by MGA3 under small-scale conditions can be downregulated by the overexpression of OGDH activity and that this manipulation also has a positive effect on the production level of l-lysine in the AEC-resistant B. methanolicus host M168-20. The latter is the first example demonstrating that manipulations of primary metabolism enzymes can be used to improve l-lysine production in B. methanolicus. Summarized, the results presented here should represent an important basis for future metabolic engineering aiming at either maximizing or controlling l-glutamate synthesis from methanol by thermotolerant B. methanolicus strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Research Council of Norway.

We thank Tone Haugen and Lihua Yu for technical assistance and Jörg Stülke for kindly providing the B. subtilis GP650 strain.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernstrom JD. 2009. Symposium summary. The roles of glutamate in taste, gastrointestinal function, metabolism, and physiology. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90:881S–885S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm N, Burkovski A. 2011. Engineering of nitrogen metabolism and its regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum: influence on amino acid pools and production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89:239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asakura Y, Kimura E, Usuda Y, Kawahara Y, Matsui K, Osumi T, Nakamatsu T. 2007. Altered metabolic flux due to deletion of odhA causes l-glutamate overproduction in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1308–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J, Hirasawa T, Sato Y, Nagahisa K, Furusawa C, Shimizu H. 2009. Effect of odhA overexpression and odhA antisense RNA expression on Tween-40-triggered glutamate production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 81:1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belitsky BR. 2002. Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells, p 203–231 Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick L. (ed), Biosynthesis of amino acids of the glutamate and aspartate families, alanine, and polyamines. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commichau FM, Gunka K, Landmann JJ, Stülke J. 2008. Glutamate metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: gene expression and enzyme activities evolved to avoid futile cycles and to allow rapid responses to perturbations of the system. J. Bacteriol. 190:3557–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 1998. Role and regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:6298–6305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kada S, Yabusaki M, Kaga T, Ashida H, Yoshida K. 2008. Identification of two major ammonia-releasing reactions involved in secondary natto fermentation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 72:1869–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeigler DR, Prágai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB. 2008. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J. Bacteriol. 190:6983–6995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunka K, Tholen S, Gerwig J, Herzberg C, Stülke J, Commichau FM. 2012. A high-frequency mutation in Bacillus subtilis: requirements for the decryptification of the gudB glutamate dehydrogenase gene. J. Bacteriol. 194:1036–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commichau FM, Wacker I, Schleider J, Blencke HM, Reif I, Tripal P, Stülke J. 2007. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis mutants with carbon source-independent glutamate biosynthesis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12:106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohannon DE, Sonenshein AL. 1989. Positive regulation of glutamate biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 171:4718–4727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belitsky BR, Kim HJ, Sonenshein AL. 2004. CcpA-dependent regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 186:3392–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commichau FM, Herzberg C, Tripal P, Valerius O, Stülke J. 2007. A regulatory protein-protein interaction governs glutamate biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis: the glutamate dehydrogenase RocG moonlights in controlling the transcription factor GltC. Mol. Microbiol. 65:642–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belitsky BR, Wray LV, Jr, Fisher SH, Bohannon DE, Sonenshein AL. 2000. Role of TnrA in nitrogen source-dependent repression of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182:5939–5947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2004. Modulation of activity of Bacillus subtilis regulatory proteins GltC and TnrA by glutamate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 186:3399–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunka K, Commichau FM. 2012. Control of glutamate homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis: a complex interplay between ammonium assimilation, glutamate biosynthesis and degradation. Mol. Microbiol. 85:213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonenshein AL. 2007. Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:917–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Commichau FM, Stülke J. 2008. Trigger enzymes: bifunctional proteins active in metabolism and in controlling gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 67:692–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher SH, Sonenshein AL. 1984. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase mutants pleiotropically altered in glucose catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 157:612–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brautaset T, Jakobsen ØM, Josefsen KD, Flickinger MC, Ellingsen TE. 2007. Bacillus methanolicus: a candidate for industrial production of amino acids from methanol at 50°C. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74:22–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrader J, Schilling M, Holtmann D, Sell D, Filho MV, Marx A, Vorholt JA. 2009. Methanol-based industrial biotechnology: current status and future perspectives of methylotrophic bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 27:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brautaset T, Jakobsen ØM, Degnes KF, Netzer R, Nærdal I, Krog A, Dillingham R, Flickinger MC, Ellingsen TE. 2010. Bacillus methanolicus pyruvate carboxylase and homoserine dehydrogenase I and II and their roles for l-lysine production from methanol at 50°C. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87:951–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heggeset TMB, Krog A, Balzer S, Wentzel A, Ellingsen TE, Brautaset T. 2012. Genome sequence of thermotolerant Bacillus methanolicus: features and regulation related to methylotrophy and production of l-lysine and l-glutamate from methanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:5170–5181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakobsen ØM, Benichou A, Flickinger MC, Valla S, Ellingsen TE, Brautaset T. 2006. Upregulated transcription of plasmid and chromosomal ribulose monophosphate pathway genes is critical for methanol assimilation rate and methanol tolerance in the methylotrophic bacterium Bacillus methanolicus. J. Bacteriol. 188:3063–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoch JA. 1991. Genetic analysis in Bacillus subtilis. Methods Enzymol. 204:305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goss TJ, Perez-Matos A, Bender RA. 2001. Roles of glutamate synthase, gltBD, and gltF in nitrogen metabolism of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:6607–6619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakobsen ØM, Brautaset T, Degnes KF, Heggeset TM, Balzer S, Flickinger MC, Valla S, Ellingsen TE. 2009. Overexpression of wild-type aspartokinase increases l-lysine production in the thermotolerant methylotrophic bacterium Bacillus methanolicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:652–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. 2003. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3784–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brautaset T, Williams MD, Dillingham RD, Kaufmann C, Bennaars A, Crabbe E, Flickinger MC. 2003. Role of the Bacillus methanolicus citrate synthase II gene, citY, in regulating the secretion of glutamate in l-lysine-secreting mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3986–3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resnekov O, Melin L, Carlsson P, Mannerlöv M, Vongabain A, Hederstedt L. 1992. Organization and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis odhAB operon, which encodes 2 of the subenzymes of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Mol. Gen. Genet. 234:285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan MI, Ito K, Kim H, Ashida H, Ishikawa T, Shibata H, Sawa Y. 2005. Molecular properties and enhancement of thermostability by random mutagenesis of glutamate dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69:1861–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunka K, Newman JA, Commichau FM, Herzberg C, Rodrigues C, Hewitt L, Lewis RJ, Stülke J. 2010. Functional dissection of a trigger enzyme: mutations of the Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase RocG that affect differentially its catalytic activity and regulatory properties. J. Mol. Biol. 400:815–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leigh JA, Dodsworth JA. 2007. Nitrogen regulation in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:349–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Picossi S, Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2007. Molecular mechanism of the regulation of Bacillus subtilis gltAB expression by GltC. J. Mol. Biol. 365:1298–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nærdal I, Netzer R, Ellingsen TE, Brautaset T. 2011. Analysis and manipulation of aspartate pathway genes for l-lysine overproduction from methanol by Bacillus methanolicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:6020–6026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brautaset T, Jakobsen ØM, Flickinger MC, Valla S, Ellingsen TE. 2004. Plasmid-dependent methylotrophy in thermotolerant Bacillus methanolicus. J. Bacteriol. 186:1229–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawahara Y, Takahashi-Fuke K, Shimizu E, Nakamatsu T, Nakamori S. 1997. Relationship between the glutamate production and the activity of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase in Brevibacterium lactofermentum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 61:1109–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chistoserdova L, Kalyuzhnaya MG, Lidstrom ME. 2009. The expanding world of methylotrophic metabolism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:477–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haima P, Bron S, Venema G. 1987. The effect of restriction on shotgun cloning and plasmid stability in Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol. Gen. Genet. 209:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]