Abstract

Alphavirus nonstructural protein 2 (nsP2) has pivotal roles in viral RNA replication, host cell shutoff, and inhibition of antiviral responses. Mutations that individually rendered other alphaviruses noncytopathic were introduced into chikungunya virus nsP2. Results show that (i) nsP2 mutation P718S only in combination with KR649AA or adaptive mutation D711G allowed noncytopathic replicon RNA replication, (ii) prohibiting nsP2 nuclear localization abrogates inhibition of antiviral interferon-induced JAK-STAT signaling, and (iii) nsP2 independently affects RNA replication, cytopathicity, and JAK-STAT signaling.

TEXT

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a member of the Alphavirus genus within the Togaviridae family. In humans, infection by this mosquito-borne virus can result in the development of a high fever, rash, and incapacitating, sometimes chronic, arthralgia. In the last decade, CHIKV outbreaks occurred throughout the Indian Ocean region, including La Reunion, infecting up to one-third of the human population, before infecting millions of people in India and Southern Asia (1, 2). CHIKV is a positive-strand RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm of infected cells. The genome contains four nonstructural proteins (nsP1 to nsP4) that are directly translated from the genomic RNA (gRNA). The viral structural proteins are translated later in infection from subgenomic mRNA (sgRNA) (3).

nsP1 is a methyltransferase and is associated with cellular membranes (4), nsP3 is a phosphoprotein that recruits host factor G3BP and consequently inhibits the formation of cellular stress granules (5, 6), and nsP4 is the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3). nsP2 contains the viral helicase, protease, and a putative C-terminal methyltransferase domain; associates with many host proteins; and can effectively shut down host cell protein synthesis (7–11). Alphavirus nsP2 also contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) in its C-terminal domain (CHIKV nsP2 KR649-650) (Fig. 1A, top). nsP2 from related Semliki Forest virus (SFV) and Sindbis virus (SINV) has been shown to translocate to the nucleus (12–14), as specific mutations within the NLS retained SFV nsP2 in the cytoplasm and reduced its cytopathicity (15). In the nucleus, nsP2 of Old World alphaviruses (SFV, SINV, and CHIKV) has been reported to inhibit host cell mRNA transcription via degradation of a subunit of DNA-directed RNA polymerase II (RPB1) (16). Mutation of a conserved proline residue in a site homologous to CHIKV nsP2 P718 (Fig. 1A, bottom) rendered SINV noncytopathic and alleviated the transcriptional inhibition via RPB1 (16–18).

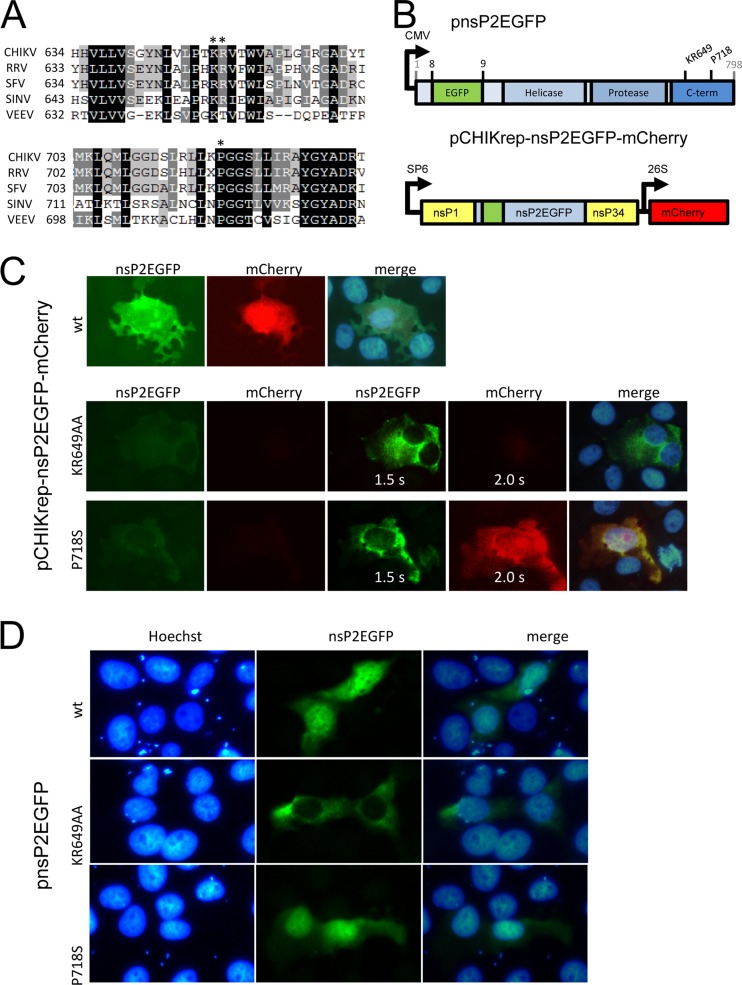

Fig 1.

CHIKV nuclear localization depends on an intact NLS. (A) Partial amino acid alignment of alphavirus nsP2s. RRV, Ross River virus; VEEV, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Asterisks indicate the conserved amino acids lysine (K) and arginine (R) in the NLS at CHIKV nsP2 position 649 (top) and the conserved proline (P) at position 718 (bottom). (B) Schematic representation of pnsP2EGFP (top) and pCHIKrep-nsP2EGFP-mCherry (bottom). EGFP has been inserted between amino acids 8 and 9 as indicated. The locations of conserved site mutations (KR649 and P718) are indicated. (C) Vero cells were transfected with in vitro-transcribed CHIKrep-nsP2EGFP-mCherry wild-type (wt) RNA and the KR649AA and P718S mutants. After 24 h, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min at room temperature and nuclei were visualized by Hoechst 33342 staining (10 ng/ml). All samples were visualized with identical exposure times prior to being overexposed. (D) Vero cells were transfected with pCMV-nsP2EGFP, nsP2EGFPKR649AA, or nsP2EGFPP718S. After 24 h, cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst stain and visualized with a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1m inverted microscope in combination with an X-Cite 120 series lamp.

In addition, alphavirus nsP2 has been shown to antagonize the host's main antiviral response, the interferon (IFN) response, in two ways: (i) beta interferon (IFN-β) transcription via global host shutoff and (ii) downstream type I/II IFN-induced Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling (16, 19–22). Upon activation, phosphorylated STAT1/2 proteins translocate as dimers into the nucleus to activate the transcription of antiviral genes, bringing the cell into an antiviral state (23). Inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation and/or nuclear translocation is an important determinant of alphavirus virulence (22, 24).

Previously, we showed that CHIKV replication is sensitive to prestimulation of cells with IFNs but becomes largely resistant to IFNs once replication has been established (21). In addition, we showed that individually expressed CHIKV nsP2 is a potent inhibitor of IFN downstream signaling by blocking STAT1 nuclear translocation. In the context of CHIKV replicon RNA replication, the mutation P718S within the nsP2 gene abrogated the inhibitory effects of nsP2, reallowing STAT1 to translocate to the nucleus upon stimulation with IFN (21). Since the C-terminal domain of nsP2 appears to be highly multifunctional and is associated with host cell shutoff and cytopathic effect (CPE), the inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling, viral replication, and nuclear translocation of nsP2, we set out to determine whether or not these characteristics of nsP2 are intrinsically connected.

We began by investigating the cellular distribution of CHIKV nsP2. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was fused within the N terminus of nsP2 (essentially as described for SINV [14]), in a CHIKV replicon expressing mCherry from the 26S subgenomic promoter (21), creating CHIKrep-nsP2EGFP-mCherry (Fig. 1B, bottom). Mutations in the NLS (KR649AA) or P718 (P718S) were introduced, creating CHIKrep-nsP2EGFPKR649AA-mCherry and CHIKrep-nsP2EGFPP718S-mCherry, respectively. Transfection of in vitro-transcribed CHIKrep-nsP2EGFP-mCherry RNA into Vero cells showed that nsP2EGFP not only translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus but also supports functional viral RNA replication and sgRNA expression as indicated by mCherry expression (Fig. 1C, top panel). Both the mutated replicons were hardly detectable when the same exposure time was used as that with wild-type CHIKrep-nsP2EGFP-mCherry. However, longer exposure times revealed that nsP2EGFPKR649AA was exclusively localized to the cytoplasm and that the mCherry signal was barely detectable (Fig. 1C). Although overall protein levels were much lower, nsP2EGFPP718S distribution and the mCherry signal resembled those of the wild-type replicon (Fig. 1C).

Since these mutations in the C terminus of alphavirus nsP2 clearly affect viral protein expression, we introduced both the mutations in the NLS (KR649AA) or P718S into a plasmid that individually expressed nsP2-EGFP from a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (Fig. 1B, top) creating pnsP2-EGFP, pnsP2-EGFPKR649AA, and pnsP2-EGFPP718S, respectively. As expected and similarly to expression from replicon (Fig. 1C), individually expressed nsP2EGFP fusion proteins localized to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 1D, top panels). In line with what was found for SFV, disruption of the NLS in CHIKV nsP2 blocked nuclear localization and retained nsP2 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1D, middle panels) (12, 15). In contrast, the P718S mutation still allowed nuclear translocation and displayed a distribution of the nsP2EGFP fusion protein similar to that of wild-type nsP2 (Fig. 1D, bottom panels). In the context of replicon RNA replication (Fig. 1C), the fraction of nsP2EGFP in the nucleus was somewhat smaller than individually expressed nsP2EGFP (Fig. 1D). Most likely, more nsP2 is retained in the cytoplasm when it interacts with other nsPs to form replication complexes. These results demonstrate that CHIKV nsP2 is present in the nucleus during RNA replication and upon individual expression but requires an intact NLS for nuclear translocation.

Since alphavirus nsP2 causes shutdown of host cell protein synthesis and is cytotoxic (11, 15, 17), we investigated the effect of the mutations in the C terminus of CHIKV nsP2 on host cell protein synthesis. CMV promoter-driven expression plasmids (21) encoding nsP2KR649AA and nsP2P718S mutants were transfected into Vero cells together with a plasmid constitutively expressing Renilla luciferase (Rluc). Cells transfected with a control plasmid expressing EGFP were either left untreated or treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis. Both CHX treatment and wild-type nsP2 expression reduced the amount of translated Rluc considerably, whereas both mutants did not decrease Rluc protein synthesis (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, nsP2KR649AA even seemed to increase Rluc synthesis (Fig. 2A). Although alphavirus nsP2 is known to modulate host cell translation, possible mechanisms that could enhance general translation have not been reported (11, 15, 17, 18, 25).

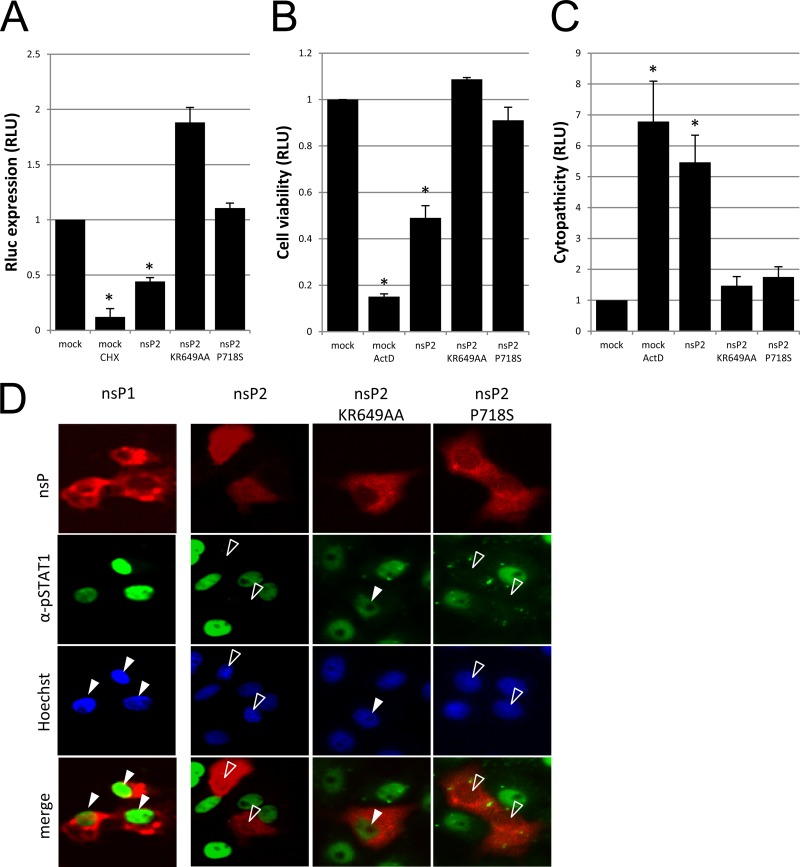

Fig 2.

Mutations in CHIKV nsP2 differentially influence host shutoff-mediated cytopathicity and the inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling. (A to C) Vero cells were transfected with either control plasmid pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) or CMV-nsP2, CMV-nsP2KR649AA, or CMV-nsP2P718S. (A) In addition to the nsP2 plasmid, cells were cotransfected with plasmid constitutively expressing Renilla luciferase (pRL-TK; Promega). Control cells were either left untreated or treated with CHX (0.5 μg/ml) for 24 h, before Rluc expression was measured. Values are depicted as the average duplicate samples from two individual experiments. Error bars represent 1 standard error, and an asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the mock treatment (Tukey honestly significant difference [HSD] test, P < 0.05). RLU, relative light units. (B and C) Cells were transfected with the nsP2 variants or control plasmid. Controls were either treated with ActD (2 μg/ml) for 48 h or left untreated. After 48 h, cell viability (B) or caspase activity (C) was measured with luminescence-based assays (CelltiterGLO and Caspase-GLO 3/7 assays; Promega). Values are depicted as the average of triplicate samples from three individual experiments and relative to the mock treatment. Error bars represent 1 standard error, and an asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the mock treatment (Tukey HSD test, P < 0.05). (D) Vero cells were transfected with the indicated mutants of pCMV-nsP2. After 24 h, cells were fixed and permeabilized with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in phosphate-buffered saline. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 3342. STAT1 nuclear translocation was visualized with anti-pSTAT1 primary antibody (phospho-Tyr701; SAB Signalway antibody) and the secondary antibody GaR-AF488 (Molecular Probes). Open arrowheads indicate the nuclei of nsP2-positive cells that lack the signal for pSTAT1. Solid arrowheads indicate nsP2-positive cells with nuclear pSTAT1.

Subsequently, the level of cytotoxicity induced by CHIKV nsP2 and its mutants was investigated in cell viability and apoptosis assays. Vero cells were transfected either with the control plasmid or with plasmids encoding one of the nsP2 mutants. Cells transfected with the control plasmid were either left untreated or treated with actinomycin D (ActD) to induce CPE through transcriptional inhibition (26). Both treatment with ActD and transfection with nsP2 resulted in severe CPE and thus reduced the total cell viability (Fig. 2B). In sharp contrast, expression of either the nsP2KR649AA or nsP2P718S mutant did not induce any CPE over the course of the experiment. In a parallel experiment, the level of nsP2-induced apoptosis was determined by measuring effector caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 2C). The presence of either ActD or nsP2 resulted in a significant induction of caspase activity compared to the mock treatment. In line with results from the cell viability assay, both mutant nsP2 proteins did not induce any caspase activity. Together, these results indicate that mutation of the NLS (KR649) or the conserved proline at P718 abrogates host cell shutoff and significantly decreases the cytotoxicity of nsP2 and the subsequent induction of apoptosis.

Previously, we reported that in the context of CHIKV RNA replication, nsP2P718S allows STAT1 nuclear translocation, whereas wild-type nsP2 is a potent inhibitor of JAK-STAT signaling (21). Because not only residue P718 but also KR649 is important for viral replication, host cell shutoff, and associated CPE, we investigated whether or not there is a connection with the inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling by individually expressed nsP2. Vero cells were transfected with either wild-type pCMV-nsP2, -nsP2KR649AA, or -nsP2P718S. Since nsP1 alone did not have any effect on STAT1 nuclear translocation, pCMV-nsP1 was used as a control (Fig. 2D, far left) (21). At 24 h posttransfection, STAT1 phosphorylation was induced with IFN-β. Immunostaining with phospho-STAT1 antibodies showed that nsP2 wild type clearly inhibits STAT1 nuclear translocation (Fig. 2D, middle left). The NLS mutant nsP2KR649AA completely lost the ability to inhibit STAT1 nuclear translocation, indicating that a functional NLS in nsP2 may be required for blocking the JAK-STAT pathway (Fig. 2D, middle right). Unexpectedly, given the previously observed abrogation of JAK-STAT inhibition by a CHIKV replicon with a P718S mutation in nsP2, the individually expressed nsP2P718S mutant still inhibited STAT1 nuclear translocation to the same extent as did wild-type nsP2 (Fig. 2D, far right).

We therefore hypothesized that reduced RNA replication of the CHIKV replicon carrying the P718S mutation could explain the observed lack of inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling in our earlier study (21). We set out to determine what the (combined) effects of the NLS and P718S mutations were on CHIKV RNA replication and cytopathicity. In a puromycin-selectable CHIKV replicon which was described previously (21), we engineered both mutations either separately or together, creating CHIKrep-nsP2KR649AA-pac2AEGFP, CHIKrep-nsP2P718S-pac2AEGFP, and CHIKrep-nsP2KR649-P718S-pac2AEGFP, respectively. In vitro-transcribed RNA was transfected into BHK cells, and puromycin selection was started 24 h posttransfection (hpt) (Fig. 3A). The double mutant (CHIKrep-nsP2KR649-P718S) proved easily selectable (Fig. 3A, panel e) and is similar to a recently described noncytopathic CHIKV replicon that acquired a 5-amino-acid insertion of unknown origin that disrupted the NLS (18). However, multiple attempts to select cells that expressed replicons with single nsP2 mutations were unsuccessful (Fig. 3A, panels c and d). In one of these experiments, however, a single colony of the CHIKrep-nsP2P718S-pac2AEGFP mutant survived and grew out to a stable, CHIKrep-pac2AEGFP-expressing cell line. Sequencing of the nsP2 gene revealed that nsP2 had acquired a second-site mutation, D711G. To exclude the possibility that additional adaptive mutations outside nsP2 were acquired, we engineered a replicon with only the D711G and P718S mutations (CHIKrep-nsP2D711G-P718S-pac2AEGFP). Transfection into BHK cells displayed a noncytopathic phenotype, and as a result, these cells were readily selected with puromycin (Fig. 3A, panel f).

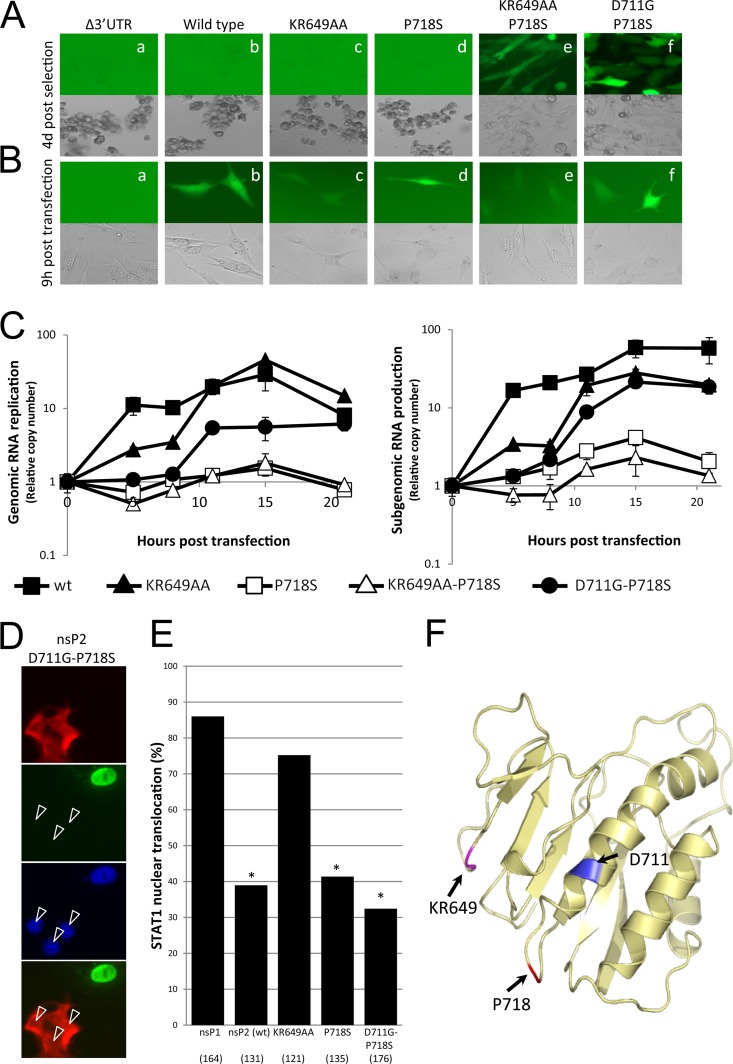

Fig 3.

CHIKV nsP2 requires multiple mutations to establish noncytopathic replication, independently of STAT1 nuclear translocation. (A and B) BHK cells were transfected with in vitro-transcribed RNA of the various mutants of CHIKrep-pac2AEGFP (a to f). (A) At 24 hpt, cells were selected for noncytopathic replicon replication expressing the puromycin resistance gene (pac) by adding puromycin (5 ng/ml) to the medium. Pictures were taken at 9 h (B) and 5 days (A) posttransfection. (C) Vero cells were transfected with in vitro-transcribed RNA of the indicated mutants of CHIKrep-pac2AEGFP. At indicated times posttransfection, total RNA was harvested (Maxwell, LEV16 simplyRNA cell kit; Promega) and reverse transcribed (SuperScriptIII; Invitrogen) using random primers. Genomic RNA replication was measured using semiquantitative PCR (IQ SYBRgreen; Bio-Rad). Depicted is a representative of 2 independent experiments. Values represent the averages from duplicate samples, after being normalized for a nonreplicating replicon (lacking the 3′ UTR) and relative to input RNA at 0 h posttransfection. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. (D) Vero cells were transfected with nsP2D711G-P718S and fixed and stained for pSTAT1. Open arrowheads indicate the nuclei of nsP2-positive cells that lack the signal for pSTAT1. (E) Vero cells were transfected with the indicated mutants of pCMV-nsP2 and immunostained with pSTAT1 24 hpt. Values represent manual cell counts of STAT1-positive nuclei, relative to nsP1. Values within parentheses represents population size. Asterisks indicate significant decrease from nsP1 (binomial test, P < 0.01). (F) Model of the C-terminal domain of CHIKV nsP2. Loop structures 1 to 4 and residues KR649 (magenta), D711 (blue), and P718 (red) are indicated.

To investigate whether reduced cytopathicity was due to nsP2-related host cell modulation and/or affected replication efficiency, we measured CHIKrep RNA replication in a time course experiment. BHK cells were transfected with either wild-type CHIKrep-pac2AEGFP (Fig. 3B, panel b), a replication-defective variant lacking its 3′ untranscribed region (UTR) (CHIKrep-pac2AEGFP-Δ3′UTR) (Fig. 3B, panel a), or one of the above-described mutants (Fig. 3B, panels c to f). Cells were harvested at different times posttransfection, and the relative copy numbers of CHIKrep gRNA and sgRNA were quantified by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) via amplification of parts of the nsP1 and the pacEGFP genes, respectively. At 15 hpt, all replicons had reached peak RNA copy numbers (Fig. 3C). The transfected cells were not subjected to puromycin selection, making it likely that the observed decrease after 15 h was caused by proliferation of untransfected cells and/or cell death induced by CHIKV RNA replication. At 15 hpt, wild-type CHIKrep displayed an ∼30-fold increase in relative copy numbers of gRNA (Fig. 3C, left) and an ∼60-fold increase of sgRNA (Fig. 3C, right). The gRNA levels of the KR649AA mutant were similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 3C, left). The primers used to amplify sgRNA also amplify the corresponding fragment from the gRNA. Since the level of sgRNA amplification was comparable to that of gRNA, this indicates that the actual production of sgRNA was severely impaired (Fig. 3C, right). The lack of mCherry production during CHIKrep-nsP2EGFPKR649AA-mCherry replication confirms the reduction in sgRNA production (Fig. 1C). The P718S mutant had a very low level of gRNA replication (Fig. 3C, left) with a respective ∼3-fold increase of sgRNA at 15 hpt. (Fig. 3C, right). Reduced replication rates of both mutant replicons correspond to what was found for other alphavirus replicons that carry mutations at homologous sites (15, 18). The severely diminished sgRNA production of CHIKrep-nsP2EGFPKR649AA has not been reported previously. These observations and those presented by others indicate that various mutations at these sites can differentially affect the efficiency of alphavirus replicon RNA replication, depending on the alphavirus species (15, 18). The replicon with both the KR649AA and P718S mutations has an intermediate phenotype, resulting in low-level production of gRNA and sgRNA (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, RNA replication of the D711G-P718S replicon was partly rescued by this novel adaptive mutation, as observed by increased gRNA (∼7-fold) and sgRNA (∼12-fold) levels at 15 hpt (Fig. 3C).

These results indicate that, unlike those of other alphaviruses, CHIKV replicons require multiple mutations in the C terminus of nsP2 for establishment of noncytopathic replication. Since the mutations KR649AA and P718S completely reduced the cytotoxicity of nsP2 when it was individually expressed (Fig. 2B and C), the inability to select both CHIKrep-nsP2KR649AA-pac2AEGFP and CHIKrep-nsP2P718S-pac2AEGFP replicons is likely to be the result of reduced production of sgRNA messenger and gRNA replication, respectively (Fig. 3C). The reduced replication efficiencies of replicons with the P718S mutation (Fig. 1C and 3C) explain the absence of inhibition of STAT1 nuclear translocation observed in our previous study (21). In addition, we identified a novel combination of mutations (D711G-P718S) that allows noncytopathic replication combined with relatively high sgRNA levels. This replicon may be an attractive tool for biotechnology applications where high-level protein expression from noncytopathic viral vectors is desired. In addition, this novel replicon carrying combined D711G and P718S mutations allowed us to investigate whether or not the inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling is intrinsically linked to noncytopathic RNA replication. We introduced the D711G mutation in pCMV-nsP2P718S to create pCMV-nsP2D711G-P718S. When STAT1 localization was assayed in the presence of this novel double mutant, it proved to be a potent inhibitor of JAK-STAT signaling (Fig. 3D). A manual count of cells displaying STAT1 nuclear translocation in the presence of either nsP1, wild-type nsP2, or one of the described nsP2 mutants clearly showed that only nsP2KR649AA was no longer able to inhibit STAT1 nuclear translocation (Fig. 3E). This shows that noncytopathic RNA replication is independent from the inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling and that a functional NLS is a prerequisite for the inhibition of STAT1 nuclear localization.

In conclusion, we show that host cell shutoff and associated CPE induced by CHIKV RNA replication are caused by CHIKV nsP2, and we have summarized our data in Table 1. The shutoff caused by overexpression of nsP2 has been clearly described by others and is a result of transcriptional arrest via degradation of DNA-directed RNA polymerase II (16). Mutations that rendered other alphavirus replicons noncytopathic (KR649AA and P718S) completely restored host cell protein synthesis and efficiently prevented nsP2-induced CPE. Unlike the situation in other alphaviruses, multiple mutations in the C terminus of nsP2 are required to establish noncytopathic CHIKV RNA replication in mammalian cells. Here, we show that directed mutagenesis of the NLS (KR649AA) in combination with the P718S mutation is sufficient to sustain noncytopathic RNA replication and selection of replicon cell lines. Moreover, we also identified a second combination of mutations, including a novel adaptive second-site mutation (D711G-P718S), not affecting the NLS and resulting in higher sgRNA synthesis than that for the other mutations. Interestingly, neither P718S alone nor P718S in combination with this novel adaptive mutation reversed the inhibition of STAT1 signaling, when nsP2 was individually expressed. Disruption of the NLS, however, abolished the inhibition of STAT1 nuclear translocation, indicating that a functional NLS within nsP2 is a pivotal determinant for inhibition of STAT1 nuclear translocation. Whether the lack of nuclear nsP2 reallows STAT1 to translocate to the nucleus or whether a mutation within the NLS disrupts an additional function of the nsP2 C-terminal domain will be the subject of future investigations. The three-dimensional structure of the C-terminal domain of CHIKV nsP2 reveals that the residues KR649-650 and P718 are both located at the tips of externalized loop structures (loops 2 and 4, respectively), whereas the novel adaptive mutation at amino acid D711 is located within the alpha helix at the base of loop 4 (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, this region of the C terminus of nsP2 has been shown to directly bind nsP3 in the viral replication complex of SINV (27). Modifications in the nsP2-nsP3 interaction could explain the differential replication efficiencies of the mutant CHIKV replicons. Taken together, these results show that the C terminus of nsP2 is a truly multifunctional domain distinctly involved in the regulation of RNA replication, cytopathicity, and the inhibition of IFN-induced JAK-STAT signaling.

Table 1.

Summary of dataa

| Characteristic | Figure(s) | Level for strain: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | KR649AA mutant | P718S mutant | KR649AA-P718S mutant | D711G-P718S mutant | ||

| Nuclear localization | 1C and D | + | − | + | NT | NT |

| CPE | 2B and C | + | − | − | − | − |

| gRNA replication | 3C | + | + | − | − | +/− |

| sgRNA production | 3C | ++ | − | +/− | − | + |

| JAK-STAT signaling inhibition | 2D, 3D and E | + | − | + | NT | + |

Symbols and abbreviation: −, negative; +/−, intermediate; +, positive; ++, strongly positive; NT, not tested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joeri Kint and the facility services from the Zodiac (Building 122, Wageningen University and Research Centre) for allowing experimental work at odd hours. We also thank Mark Sterken and Casper van Schaik for help with the Maxwell instrument and Corinne Geertsema for technical assistance and cell culture.

This work is supported by the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7 VECTORIE project number 261466).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Townson H, Nathan MB. 2008. Resurgence of chikungunya. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102:308–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suhrbier A, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Gasque P. 2012. Arthritogenic alphaviruses—an overview. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8:420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strauss JH, Strauss EG. 1994. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 58:491–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solignat M, Gay B, Higgs S, Briant L, Devaux C. 2009. Replication cycle of chikungunya: a re-emerging arbovirus. Virology 393:183–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fros JJ, Domeradzka NE, Baggen J, Geertsema C, Flipse J, Vlak JM, Pijlman GP. 2012. Chikungunya virus nsP3 blocks stress granule assembly by recruitment of G3BP into cytoplasmic foci. J. Virol. 86:10873–10879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Panas MD, Varjak M, Lulla A, Eng KE, Merits A, Karlsson Hedestam GB, McInerney GM. 2012. Sequestration of G3BP coupled with efficient translation inhibits stress granules in Semliki Forest virus infection. Mol. Biol. Cell 23:4701–4712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rozanov MN, Koonin EV, Gorbalenya AE. 1992. Conservation of the putative methyltransferase domain: a hallmark of the ‘Sindbis-like' supergroup of positive-strand RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2129–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomez de Cedron M, Ehsani N, Mikkola ML, Garcia JA, Kaariainen L. 1999. RNA helicase activity of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein NSP2. FEBS Lett. 448:19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gorchakov R, Frolova E, Sawicki S, Atasheva S, Sawicki D, Frolov I. 2008. A new role for ns polyprotein cleavage in Sindbis virus replication. J. Virol. 82:6218–6231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bourai M, Lucas-Hourani M, Gad HH, Drosten C, Jacob Y, Tafforeau L, Cassonnet P, Jones LM, Judith D, Couderc T, Lecuit M, Andre P, Kummerer BM, Lotteau V, Despres P, Tangy F, Vidalain PO. 2012. Mapping of Chikungunya virus interactions with host proteins identified nsP2 as a highly connected viral component. J. Virol. 86:3121–3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gorchakov R, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2005. Inhibition of transcription and translation in Sindbis virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 79:9397–9409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peranen J, Rikkonen M, Liljestrom P, Kaariainen L. 1990. Nuclear localization of Semliki Forest virus-specific nonstructural protein nsP2. J. Virol. 64:1888–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rikkonen M, Peranen J, Kaariainen L. 1994. Nuclear targeting of Semliki Forest virus nsP2. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 9:369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atasheva S, Gorchakov R, English R, Frolov I, Frolova E. 2007. Development of Sindbis viruses encoding nsP2/GFP chimeric proteins and their application for studying nsP2 functioning. J. Virol. 81:5046–5057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tamm K, Merits A, Sarand I. 2008. Mutations in the nuclear localization signal of nsP2 influencing RNA synthesis, protein expression and cytotoxicity of Semliki Forest virus. J. Gen. Virol. 89:676–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akhrymuk I, Kulemzin SV, Frolova EI. 2012. Evasion of the innate immune response: the Old World alphavirus nsP2 protein induces rapid degradation of Rpb1, a catalytic subunit of RNA polymerase II. J. Virol. 86:7180–7191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dryga SA, Dryga OA, Schlesinger S. 1997. Identification of mutations in a Sindbis virus variant able to establish persistent infection in BHK cells: the importance of a mutation in the nsP2 gene. Virology 228:74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pohjala L, Utt A, Varjak M, Lulla A, Merits A, Ahola T, Tammela P. 2011. Inhibitors of alphavirus entry and replication identified with a stable Chikungunya replicon cell line and virus-based assays. PLoS One 6:e28923. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Breakwell L, Dosenovic P, Karlsson Hedestam GB, D'Amato M, Liljestrom P, Fazakerley J, McInerney GM. 2007. Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein 2 is involved in suppression of the type I interferon response. J. Virol. 81:8677–8684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frolova EI, Fayzulin RZ, Cook SH, Griffin DE, Rice CM, Frolov I. 2002. Roles of nonstructural protein nsP2 and alpha/beta interferons in determining the outcome of Sindbis virus infection. J. Virol. 76:11254–11264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fros JJ, Liu WJ, Prow NA, Geertsema C, Ligtenberg M, Vanlandingham DL, Schnettler E, Vlak JM, Suhrbier A, Khromykh AA, Pijlman GP. 2010. Chikungunya virus nonstructural protein 2 inhibits type I/II interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling. J. Virol. 84:10877–10887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simmons JD, White LJ, Morrison TE, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Johnston RE, Heise MT. 2009. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus disrupts STAT1 signaling by distinct mechanisms independent of host shutoff. J. Virol. 83:10571–10581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Randall RE, Goodbourn S. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simmons JD, Wollish AC, Heise MT. 2010. A determinant of Sindbis virus neurovirulence enables efficient disruption of Jak/STAT signaling. J. Virol. 84:11429–11439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. White LK, Sali T, Alvarado D, Gatti E, Pierre P, Streblow D, Defilippis VR. 2011. Chikungunya virus induces IPS-1-dependent innate immune activation and protein kinase R-independent translational shutoff. J. Virol. 85:606–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sawicki SG, Godman GC. 1972. On the recovery of transcription after inhibition by actinomycin D. J. Cell Biol. 55:299–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shin G, Yost SA, Miller MT, Elrod EJ, Grakoui A, Marcotrigiano J. 2012. Structural and functional insights into alphavirus polyprotein processing and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:16534–16539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]