Abstract

Alphavirus replicase complexes are initially formed at the plasma membrane and are subsequently internalized by endocytosis. During the late stages of infection, viral replication organelles are represented by large cytopathic vacuoles, where replicase complexes bind to membranes of endolysosomal origin. In addition to viral components, these organelles harbor an unknown number of host proteins. In this study, a fraction of modified lysosomes carrying functionally intact replicase complexes was obtained by feeding Semliki Forest virus (SFV)-infected HeLa cells with dextran-covered magnetic nanoparticles and later magnetically isolating the nanoparticle-containing lysosomes. Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture combined with quantitative proteomics was used to reveal 78 distinct cellular proteins that were at least 2.5-fold more abundant in replicase complex-carrying vesicles than in vesicles obtained from noninfected cells. These host components included the RNA-binding proteins PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K, which were shown to colocalize with the viral replicase. Silencing of hnRNP M and hnRNP C expression enhanced the replication of SFV, Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), and Sindbis virus (SINV). PCBP1 silencing decreased SFV-mediated protein synthesis, whereas hnRNP K silencing increased this synthesis. Notably, the effect of hnRNP K silencing on CHIKV- and SINV-mediated protein synthesis was opposite to that observed for SFV. This study provides a new approach for analyzing the proteome of the virus replication organelle of positive-strand RNA viruses and helps to elucidate how host RNA-binding proteins exert important but diverse functions during positive-strand RNA viral infection.

INTRODUCTION

Semliki Forest virus (SFV) belongs to the genus Alphavirus of the family Togaviridae. Alphaviruses can replicate in invertebrate vectors and in vertebrate hosts. Infection of mosquito cells can persist without detriment to the host, but infection of vertebrate cells is usually associated with cell death. SFV and Sindbis virus (SINV) are the most-studied members of their genus, and in contrast to several other alphaviruses, such as Western, Eastern, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses and the recently reemerging Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), SFV and SINV are not typically associated with serious human illness (1, 2).

The SFV genome is a positive-stranded RNA molecule of approximately 11.5 kb. Four nonstructural (ns) proteins (nsP1 through nsP4) are translated directly from the genome as a single polyprotein precursor, P1234. Structural proteins are translated from a subgenomic (SG) mRNA generated from an internal promoter located on the complementary, negative-strand template (1) (Fig. 1A). Only ns proteins are required for virus replication, indicating that they represent virus-specific components of replication complexes (RCs). SFV P1234 is processed by nsP2 protease in a well-controlled manner (3–5). Together with the polyprotein processing intermediate P123, nsP4 is capable of negative-strand RNA synthesis, which occurs during an early stage of infection and is halted approximately 3 to 4 h postinfection (p.i.). Once processing is complete, mature RCs, which synthesize only positive-strand RNAs, are formed (6–8). Only a fraction of each ns protein produced during infection is included in the RCs; the rest localizes to different locations within the cell or becomes destroyed (9–12). The functions of nsPs excluded from RCs are less clear; nonetheless, their participation is critical for infection. For example, nsP1 induces the formation of filopodia-like structures on the plasma membranes (PMs) of infected cells (11, 13). In its free form, nsP2 induces cytotoxic effects, such as shutting down cellular transcription and translation (14–16), and suppresses cellular antiviral responses (17, 18). nsP3 has been shown to localize to cytoplasmic granules, but the biological implications of this observation are only beginning to be elucidated (12, 19–23). Individual molecules of nsP4 are not stable outside RCs and are rapidly degraded (9).

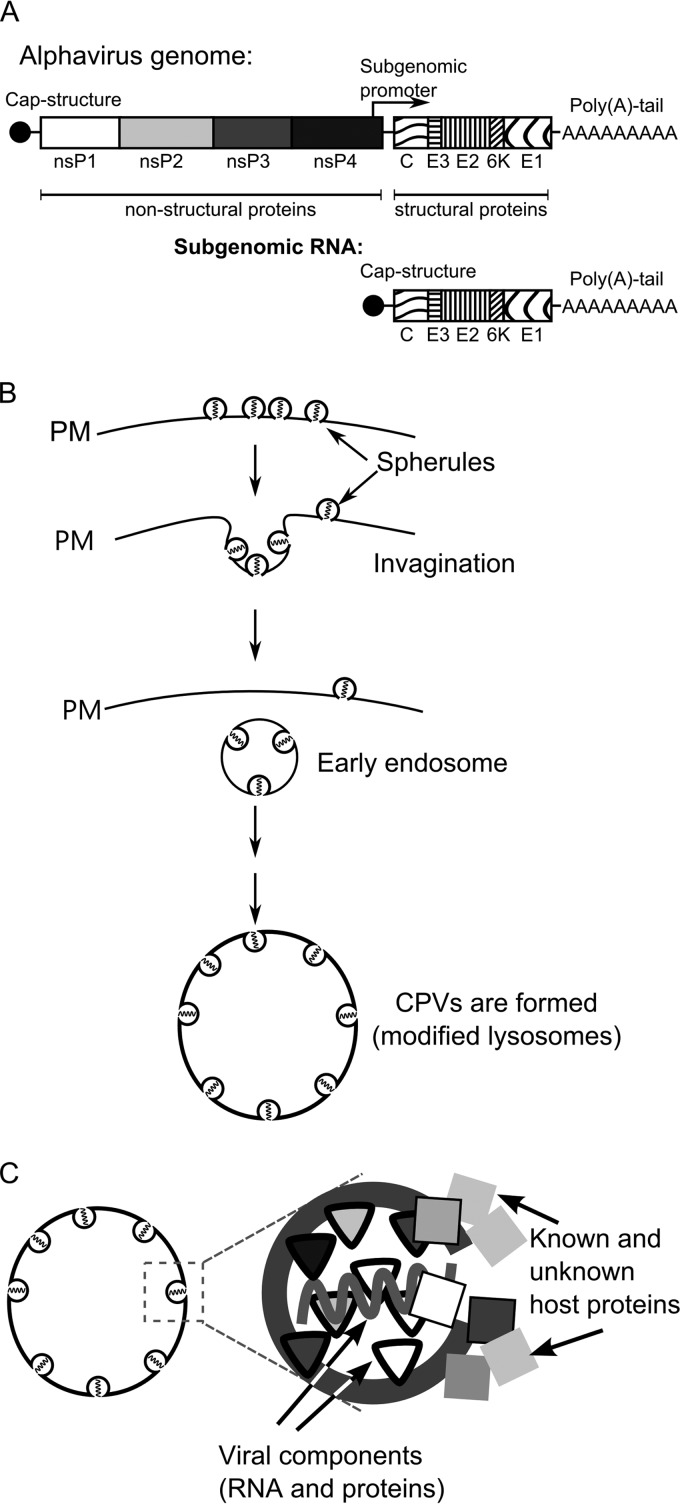

Fig 1.

Alphavirus genome and the CPV-1 formation pathway. (A) Schematic representation of alphavirus genomic and SG RNAs. Open reading frames for nonstructural and structural proteins are shown. (B) Formation of virus replication organelles of alphaviruses begins with the formation of spherules on the plasma membrane (PM) of infected cells. Next, the spherules are internalized via endocytosis, and early endosomes that carry spherules are formed. In the later stages, those endosomes fuse with lysosomes in a step-by-step process leading to the formation of large virus replication organelles designated CPV-1s. (C) A spherule is a membrane invagination, which in addition to viral RNA and virus-encoded proteins also contains or is associated with an unknown number of host proteins.

In mammalian cells, the alphavirus RCs are assembled on the PM, where numerous, small invaginations (spherules) of approximately 50 nm in diameter are formed (Fig. 1B). Each spherule represents a site of viral RNA synthesis (24, 25). However, the exact copy number, stoichiometry, and locations of different nsPs within the alphavirus RCs are unknown. Later, the spherules are internalized via an endocytic process that requires a functional actin-myosin network, and they can subsequently fuse with each other and with lysosomes of infected cells (24). Thus, during the later stages of infection, the alphavirus RCs are attached to the membranes of modified endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 1B). Finally, organelles characteristic of viral replication, historically named type 1 cytopathic vacuoles (CPV-1s), are formed (1, 24, 25). Each individual CPV-1 is a large vesicle (0.6 to 2.0 μm in diameter) that harbors numerous spherules (26) and is positive for lysosomal markers, including the lysosome-associated membrane glycoproteins 1 and 2 (Lamp1 and Lamp2) (10). In contrast to smaller vesicles formed during endocytosis, CPV-1s are static, localize around the nucleus of infected cells (24), and produce viral positive-strand RNAs until cell death.

The formation of virus replication organelles is obviously associated with changes in the protein composition of corresponding subcellular compartments. However, processes other than replication may also result in virus-induced changes in the protein content of cellular organelles. In addition, many viruses also induce general changes in the protein composition of infected cells; for example, proteomic changes may occur as a result of the inhibition of cellular macromolecule synthesis or the activation of host antiviral responses. These changes can be monitored by various approaches, including quantitative proteomics, which has been used to characterize changes in the total proteome of CHIKV-infected cells (27) or the nucleolar proteome in coronavirus- or influenza virus-infected avian cells (28, 29), to analyze changes in endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrion contacts induced by human cytomegalovirus infection (30), to elucidate the signaling pathways impaired in human hepatoma cells during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection (31), and to identify host proteins associated with picornavirus RNAs (32). The identification of relocalized host cell components and/or host cell components with altered quantities during infection is especially important for understanding positive-strand RNA viruses. Since the ns proteins encoded by these viruses are apparently not sufficient to perform all of the functions essential for a successful infection, numerous host components are most likely involved in the infection process (Fig. 1C).

Recent genome-wide studies performed for several viruses revealed hundreds of host-encoded proteins that interact with viral proteins and RNAs or otherwise participate in different stages of viral infection, including RC assembly, RNA template recruitment, synthesis, and viral RNA stabilization. Similarly, several host-encoded proteins restrict viral infection (33, 34). A map of the cellular factors that interact with the alphavirus nsPs and RNAs is slowly emerging. However, the different approaches used to identify these proteins have produced divergent results. In previous studies, pulldown experiments using cells infected with SINV carrying tagged nsP2, nsP3, or nsP4 revealed largely overlapping sets of coprecipitating cellular proteins, including the 14-3-3 proteins, G3BP1 and G3BP2, PARP-1, and different hnRNPs (19, 20, 35–37). An approach based on comparing cytoplasmic membrane fractions obtained from mock-infected and infected cells identified hnRNP K as an interaction partner for alphavirus replicase proteins (38). hnRNP K has also been shown to interact with the SINV SG RNA (38), whereas another cellular protein, HuR, binds to the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of genomic and SG RNAs of SINV (39) but not CHIKV (40). In addition, genome-wide yeast two-hybrid screening identified numerous CHIKV nsP-interacting proteins (41). In that study, the largest number of interacting cellular proteins were identified for nsP2; however, only a small number of these overlapped with interaction partners identified via pull-down of tagged SINV nsP2 (36). Furthermore, RC-bound nsP3 and nP3 located in cytoplasmic granules have been shown to interact with different host proteins (42), and the same may be true for other nsPs. Consequently, the precise roles and functions of the identified host proteins in the context of alphavirus infection remain to be elucidated. The small overlap between the results obtained with different methods indicates that only a fraction of host proteins important for alphavirus infection have been identified by either of these approaches; therefore, many important host components still remain to be identified.

Cellular proteins do not necessarily need to stably interact with RCs or nsPs to affect viral replication; such associations may be transient and/or indirect, evading detection by pull-down or yeast two-hybrid experiments. However, all positive-strand RNA viruses of eukaryotes are known to reorganize intracellular membranes to create specific virus replication organelles. Thus, the association of host proteins with viral replication organelles, as reflected by the changes in their abundance in these specific cellular regions, can serve as an indicator of their importance for viral RNA replication. The ability to distinguish the changes in the protein composition of viral replication organelles from other virus-induced changes requires the isolation of these organelles. To date, the isolation of membranes roughly corresponding to viral replication organelles has been achieved only for a few positive-strand RNA viruses. Lipid raft domains, the sites of hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication, have been analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis followed by mass spectrometry and by stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (43, 44) combined with mass spectrometry (45). Furthermore, Golgi apparatus-enriched fractions, which are associated with coronavirus RNA replication, have been analyzed using SILAC-based quantitative proteomics (46). In both cases, more than a hundred host proteins that displayed significant increases or decreases in abundance upon virus infection were identified. Though the viral replication organelles analyzed in these studies were not isolated in their functional forms, quantitative proteomic analysis of virus replication organelles has proven valuable for studying proteins that are associated with the replication of RNA viruses.

In this study, we took advantage of the CPV-1 formation pathway and loaded HeLa cells with small dextran-covered magnetic beads, which incorporate into CPV-1 structures in infected cells or into lysosomes in mock-infected cells. For the first time in a study of the proteome of positive-strand RNA virus replication organelles, we showed that membranous vesicles collected from infected cells via magnetic enrichment harbored functionally active viral replicase. The protein content of these vesicles was compared to that of vesicles similarly isolated from mock-infected cells using a SILAC-based quantitative proteomics approach. Seventy-eight host proteins that were at least 2.5-fold more abundant in CPV-1s than in the endolysosomes of mock-infected cells were identified. The colocalization of several of these host proteins with RCs of SFV was confirmed using confocal microscopy. In addition, the small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated silencing of host protein expression confirmed that these factors affected SFV, SINV, and CHIKV infection in cultured HeLa cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (PAA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (PAA). L-HeLa cells used in proteomics experiments were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS. To label HeLa cells with stable isotopes (H-HeLa cells), the cells were grown in SILAC DMEM (PAA) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (PAA), heavy arginine (0.133 mM, CNLM-539; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc.), and heavy lysine (0.266 mM, CNLM-291; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc.) for at least eight generations. BHK-21 cells were grown in Glasgow minimum essential medium (GMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 2% tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco). All growth media contained 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (PAA).

Preparation of samples for analysis.

The sample preparation process is outlined in Fig. 2A. Approximately 108 HeLa cells were mock infected or infected with SFV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. At 1 h p.i., medium containing infectious virus was replaced with medium containing dextran-covered magnetic nanoparticles (fluidMAG-DX; Chemicell) at a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml. At 11 h p.i., the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fresh medium without magnetic particles was added. One hour later, the cells were washed three times with PBS, scraped, collected, and precipitated by centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 min; 1/50 of the cells were then removed and lysed with Laemmli lysis buffer. The remaining cells were suspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Scientific]). After 20 min of incubation on ice, the cells were sheared using a tight glass Dounce homogenizer. The nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 900 × g for 10 min at 4°C. One-tenth of the obtained postnuclear supernatant (PNS) was divided into two parts. One sample was mixed with hypotonic lysis buffer supplemented with 30% glycerol to obtain PNS-synth fraction, and the second sample was subjected to methanol-chloroform precipitation followed by the addition of Laemmli lysis buffer (PNS-prot fraction). Another 1/10 of the PNS was divided into two halves; both of these samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to obtain P15 (pelleted material) and S15 (supernatant) fractions. Laemmli buffer was added to the P15 fraction obtained from one of the samples (P15-prot fraction), and the pelleted material from the second one was resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer supplemented with 15% glycerol (P15-synth fraction). S15 fraction was treated similarly to PNS fraction to obtain S15-synth and S15-prot samples. The remaining PNS was used for magnetic enrichment by a high-gradient magnetic separator and appropriate separation columns (Miltenyi). Before loading the sample, each column was washed with 3 ml of PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA-PBS). BSA-PBS was used because in the absence of BSA, the yields of functional replicase organelles were low and inconsistent. The sample was loaded onto the column, and the column was washed with 10 ml BSA-PBS and removed from the separator. The bound material was eluted with a BSA-PBS solution. The collected sample was divided into two halves and was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to collect the magnetic fractions. Laemmli buffer was added to one of the obtained samples (Mag-prot fraction), and the pelleted material from the other sample was resuspended using hypotonic lysis buffer supplemented with 15% glycerol (Mag-synth fraction). The PNS-prot, S15-prot, P15-prot, and Mag-prot samples were heated at 60°C for 20 min and subsequently used for immunoblotting experiments. The PNS-synth, S15-synth, P15-synth, and Mag-synth probes were stored at −80°C and used for the analysis of SFV RNA replicase activity.

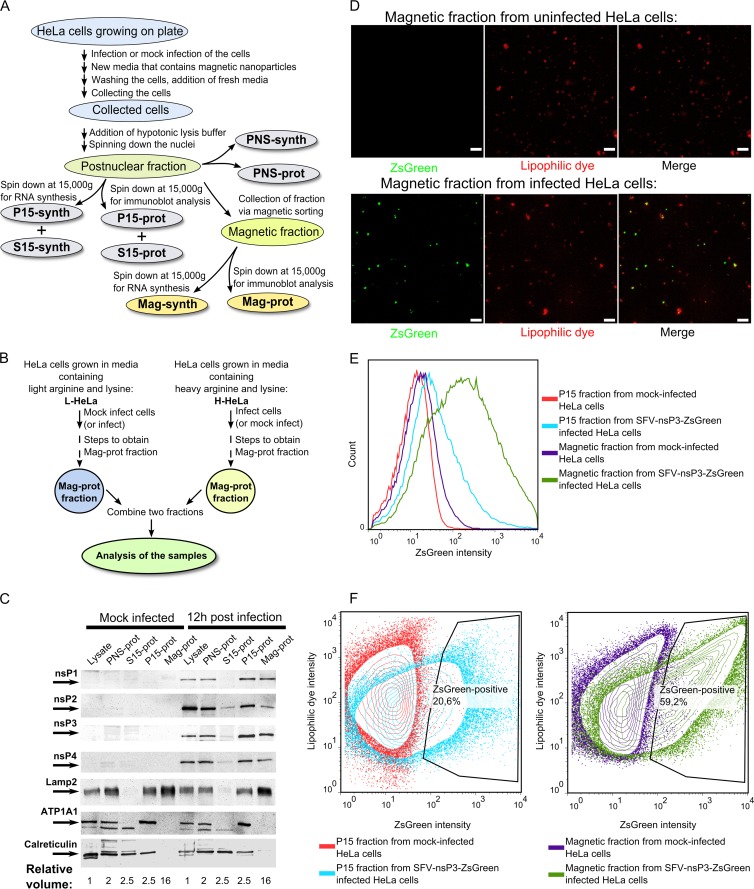

Fig 2.

Purification and analysis of SFV replication organelles. (A) An overview of the process used to obtain different cellular fractions. (B) The setup used in quantitative proteomics experiments. In the forward setup, H-HeLa cells were infected with SFV at an MOI of 1, and L-HeLa cells were mock infected. In the reverse setup, L-HeLa cells were infected with SFV at an MOI of 1, and H-HeLa cells were mock infected. In both setups, the cells were collected at 12 h p.i., and Mag-prot fractions were prepared. For each experiment, samples from L-HeLa and H-HeLa cells were combined at a 1:1 ratio and analyzed using the Orbitrap instrument. (C) Immunoblot analysis of the cell lysates and PNS-prot, S15-prot, P15-prot, and Mag-prot fractions from infected and mock-infected HeLa cells. Viral proteins were detected using antibodies against SFV nsPs; the cellular proteins Lamp2, ATP1A1, and calreticulin were used as markers for lysosomes, the PM, and the ER, respectively. The names of the detected proteins and their positions on the blot are shown on the left. The numbers below the images indicated the volume of initial lysate that was used to obtain sample analyzed on the Western blot. (D) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of magnetically purified fractions from uninfected and SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected HeLa cells. ZsGreen was detected by auto-fluorescence; CellMask deep red stain was used to stain the membranes. Combined Z-stacks are shown in both panels, and the white bars mark 5 μm. (E) An intensity histogram of ZsGreen for P15 and magnetic fractions from uninfected and SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected HeLa cells. (F) Contour plots of ZsGreen (on the x axis) and CellMask deep red stain lipophilic dye (on the y axis) for the P15 (left panel) or magnetically purified (right panel) fraction from uninfected cells is overlaid with its counterpart from SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected cells. The gating shows the percentage of ZsGreen-positive vesicles in P15 and magnetic fractions obtained from infected cells. In panels C, D, E and F, the data from one of three reproducible experiments are shown.

Flow cytometry.

The samples for flow cytometry were prepared essentially as described above except that HeLa cells were infected with SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen (47). P15 and magnetic fractions collected from both infected and uninfected cells were not separated into -prot and -synth samples; instead, the pelleted material was resuspended in 1 ml cold PBS supplemented with 2.5 μl CellMask deep red stain (Invitrogen). Samples were incubated on ice for 20 min, washed two times with PBS, and analyzed with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For each sample, 100,000 events were recorded, and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 7.6.5).

Immunoblot analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE with 10% gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and detected using primary antibodies against nsP1, nsP3 (48), nsP2, nsP4 (3), hnRNP C (ab97541; Abcam), hnRNP M (HPA024344; Sigma-Aldrich), PCBP1 (R4030; Sigma-Aldrich), hnRNP K (ab52600; Abcam), Lamp2 (ab25631; Abcam), ATP1A1 (ab7671; Abcam), calreticulin (NB600-103; Novus Biologicals), or β-actin (sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (LabAs Ltd.) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were used to develop the blots as described previously (12).

RNA synthesis assay.

The volume of PNS-synth, S15-synth, P15-synth, or Mag-synth fractions was brought to 50 μl by adding hypotonic lysis buffer supplemented with 15% glycerol and then combined with a 2-fold synthesis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 100 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μg/ml actinomycin-D, 4 mM ATP, GTP, and UTP, 2 mM CTP, 1 mCi/ml [α-32P]CTP [800 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer], and 1,600 U/ml RNasin [Promega]). The reactions were carried out at 30°C for 90 min and were stopped by the addition of SDS (2% final concentration) and proteinase K (100 μg/ml; Thermo Scientific). RNA was purified with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and separated on a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel. The gel was dried on a vacuum dryer, and the incorporated radioactivity was detected using a Typhoon Trio instrument (GE Healthcare).

Proteomics analysis.

Magnetic fractions from infected and mock-infected H-HeLa and L-HeLa cells were obtained as shown in Fig. 2B. The samples were denatured in urea lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 10 mM HEPES [pH 8.0]), and the H-HeLa and L-HeLa cellular samples were combined. The proteins were reduced for 1 h at 20°C in a 1 mM dithiothreitol solution and were alkylated for 1 h in 5 mM iodoacetamide in the dark. Endoproteinase LysC (Wako) was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 4 h at room temperature. The sample was diluted with a digestion buffer (50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in water). Sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) was added, and the sample was incubated overnight at room temperature. Enzyme activity was quenched by adding 1% trifluoroacetic acid, and the resulting peptides were desalted using Stage Tips (49).

The digests were analyzed in three technical replicates with liquid chromatograpy–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an Agilent 1200 series nanoflow system (Agilent Technologies) connected to an LTQ Orbitrap Classic mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source (Proxeon). Purified peptides were loaded on the self-packed fused silica emitter (150 mm by 0.075 mm; New Objective) packed with Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ 3-μm particles (Dr. Maisch) using a flow rate of 0.7 μl/min. The peptides were separated with a 150-min gradient from 2 to 40% of B (A, 0.5% acetic acid; B, 0.5% acetic acid–80% acetonitrile) using a flow rate of 200 nl/min and sprayed directly into the LTQ Orbitrap Classic mass spectrometer operated at a 180°C capillary temperature and a 2.4-kV spray voltage. The LTQ-Orbitrap instrument was operated in data-dependent mode with the full scan in the Orbitrap followed by consecutive MS/MS scans in the LTQ. Full mass spectra were acquired in profile mode with a mass range from m/z 300 to 1,900 at a resolving power of 60,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM). Up to five data-dependent MS/MS spectra were acquired in centroid mode in the linear ion trap for each Fourier transform mass spectrometry (FTMS) full-scan spectrum. Each fragmented ion was dynamically excluded for 60 s.

Protein identification and quantification were performed using the MaxQuant software package (version 1.1.1.36) (50). For this, the human database (containing 112,497 entries, reviewed and unreviewed canonical sequences and isoforms) was supplemented with reviewed and unreviewed SFV sequences (21 entries); both databases were downloaded from UniProtKB on 12 December 2010. MS/MS spectra were searched against this database using the MaxQuant software search engine Andromeda (51) with default parameters. Oxidation of methionine and acetylation of the protein N terminus were used as variable modifications, and carbamidomethylation of cysteine was used as a fixed modification. Analysis was limited to peptides with a length of six or more amino acid residues and a maximum of two miscleavages. A maximum false-discovery rate of 1% at both the peptide and protein levels was allowed. At least two peptides were required for protein identification, and two or more SILAC ratio counts were required to report a protein ratio, in a total of three biological replicates.

Protein hit list analysis.

To generate a protein interaction network, an online version of the STRING database (http://string-db.com) was used (52). The active prediction methods were “gene fusion,” “co-occurrence,” “experiments,” “databases,” and “textmining,” and the confidence level was set to high. In addition, the proteins were grouped according to their functions using the software program DAVID (http://david.%abcc.ncifcrf.gov) (53, 54) and the UniProtKB database (http://www.uniprot.org).

VRP production.

An SFV replicon vector expressing Renilla luciferase (Rluc) fused with nsP3 and firefly luciferases (Ffluc) from mRNAs transcribed from the SG promoter was constructed using a pSFV1 vector (55). The resulting recombinant replicon was designated SFV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc. This replicon and the SFV-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) replicon (12, 56) were packaged into viral replicon particles (VRPs) as described previously (12). The titer of the obtained SFV VRP stock was determined in HeLa cells using rabbit antiserum against nsP1 and an immunofluorescence procedure. Similarly, CHIKV- and SINV-based replicon vectors, designated CHIKV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry and SINV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry, were generated and packaged into the corresponding VRPs. Titers of the obtained VRP stocks were determined by counting the number of infected HeLa cells displaying mCherry fluorescence. Detailed cloning procedures and the replicon sequences are available upon request.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

For indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, HeLa cells were grown on coverslips in 35-mm dishes. At 50% confluence, the cells were infected with SFV or with UV-inactivated SFV at an MOI of 5 (a high MOI was used to achieve synchronous infection of cell culture); mock-infected cells were used as a control. At specific time points, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and treated with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-PCBP1, anti-hnRNP C, anti-hnRNP M, or anti-hnRNP K; mouse anti-double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (J2; Scicons) or mouse anti-Lamp2; and guinea pig anti-nsP3 (10). Incubation with primary antibody was followed by incubation with secondary anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 405, anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, and anti-guinea pig antibodies conjugated to Alexa 568 (all from Invitrogen). The samples were analyzed using an Olympus FV1000 microscope.

To visualize the vesicles in the magnetic fractions obtained from SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected HeLa cells or from mock-infected HeLa cells, the corresponding samples were treated with CellMask deep red stain as described above. After the treatment, a sample was loaded on a glass slide, covered with a cover glass, and analyzed using a Carl Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope.

siRNA transfection and the luciferase activity assay.

HeLa cells grown in 24-well plates were transfected with siRNAs with RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen) when they reached 50% confluence. Combinations of three siRNAs (Ambion) were used to silence PCBP1 (s10094, s10096, and s224175), hnRNP M (s9259, s9260, and s9261), hnRNP C (s6719, s6720, and s6721), or hnRNP K (s6737, s6738, and s6739) expression. Each well received 1.5 pmol total siRNA (0.5 pmol each); 1.5 pmol of silencer negative control no. 2 siRNA (AM4613; Ambion) was used as a control. The viability and growth of transfected cells were analyzed using the xCELLigence system (Roche).

To perform the luciferase activity assay, siRNA-transfected HeLa cells were infected with SFV, CHIKV, or SINV VRPs at an MOI of 0.01 at 48 h posttransfection (p.t.). For all three viruses, a low MOI was used because the titer of CHIKV VRP stock for HeLa cells was low. This was due to the mutation in the CHIKV envelope glycoprotein E1. It has been shown that Val residue 226 of E1 is responsible for inefficient entry of CHIKV into HeLa cells (57); however, this defect does not affect the replication and transcription of CHIKV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry, lacking the corresponding region. At selected time points, the infected cells were lysed using passive lysis buffer (Promega), and the activities of Rluc and Ffluc were measured using a dual-luciferase detection kit (Promega). Student's t tests were used for statistical analysis.

One-step growth curve and Northern blotting.

At 48 h p.t., siRNA-transfected HeLa cells were infected with SFV at an MOI of 5. At selected time points, aliquots of medium were harvested; the viral titers in the collected samples were determined using plaque titration on BHK-21 cells. Alternatively, the total RNA from 106 cells was purified at 4, 6, and 8 h p.i. with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Northern blot analysis was conducted as described previously using an RNA probe complementary to the 3′ UTR of the SFV genome (12).

RESULTS

Vesicles carrying functionally active alphavirus RCs can be purified via magnetic enrichment.

RCs of different positive-strand viruses are typically complicated and fragile structures. Compartmentalization of RCs into specific viral replication organelles theoretically provides the capacity to purify these functional assemblies. However, this approach is generally hampered by the lack of suitable methods, since the standard methods used for subcellular fractionation may not preserve the functionality of viral replicase, as is the case with SFV replicase (58). The unique pathway underlying the biogenesis of alphavirus replication organelles (24, 25) suggested that a method originally used for studies of proteins involved in endocytosis (59) could be used to isolate functional viral replication organelles. This method involves feeding cells with dextran-covered magnetic nanoparticles, which incorporate into lysosomes that can then be purified by magnetic isolation. Indeed, SFV CPV-1s frequently contain endocytosed BSA-coated gold particles if the particles are introduced into the growth medium after infection (10). Therefore, magnetic nanoparticles added to the growth media of SFV-infected cells could also be incorporated into CPV-1s.

For analysis, HeLa cells were infected with SFV at an MOI of 1. A relatively low MOI was used to minimize the possible impact of endocytosed virions on the protein content of SFV replication organelles which have endosomal/lysosomal origin. One hour after infection, the medium containing magnetic particles was added. Eleven hours later, the cells were harvested and fractionated; the same procedures were performed with mock-infected control cells (Fig. 2A). The analysis of the final samples revealed that the distributions of cellular markers, characteristic of different membranes, were similar in the samples from infected and mock-infected cells (Fig. 2C). The lysosomal marker Lamp2 was detected in PNS-prot, P15-prot and Mag-prot samples. Based on the observed levels of Lamp2, it was roughly estimated that obtained PNS contained at least half of the lysosomes present in cell lysate. Most likely not all of these lysosomes contained magnetic particles in amounts sufficient for efficient binding to magnetic separator; hence, only approximately 15% of lysosomes (the estimation is based on the amounts of Lamp2) (Fig. 2C) were captured using magnetic enrichment. At the same time, this fraction was clearly depleted of the Na+/K+ ATPase alpha-1 subunit (ATP1A1), a PM marker, and calreticulin, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker (Fig. 2C). Hence, lysosomal vesicle-enriched membranes were obtained by magnetic isolation. Moreover, all of the SFV nsPs were detected in lysate, P15-prot, and Mag-prot fractions from infected cells. As is typical for cells at a late stage of SFV4 infection, no ns polyprotein precursors or their processing intermediates were detected using this analysis (data not shown). In comparison to the crude P15 sample, the relative quantities (compared to the quantity of Lamp2) of all ns proteins in the Mag-prot fraction were somewhat reduced. The reduction was especially evident for nsP2 (Fig. 2C), most likely because it has no membrane binding capacity on its own and is known to associate with ribosomes (60). In the P15 fraction, a large portion of ribosomes associated with ER-derived vesicles and were consequently removed together with nsP2 by magnetic purification.

We then infected HeLa cells with SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen, which expresses the nsP3-ZsGreen fusion protein. The ZsGreen fluorescence colocalized with all nsP3-containing structures (data not shown); this property has previously been used to reveal the pathway of alphavirus RC formation and relocalization (24). A deep red lipophilic dye was added to P15 and magnetically purified fractions to confirm the membranous nature of the obtained structures. Fluorescence microscopy of magnetically purified samples revealed that, as expected, the obtained membranous structures had a vesicular appearance. Furthermore, more than half of vesicles from SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected cells were positive for ZsGreen (Fig. 2D). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that approximately 15 to 20% of membranous structures in the P15 fraction from SFV-nsP3-ZsGreen-infected cells were positive for ZsGreen and that magnetic purification resulted in an approximately 3-fold increase in their abundance (Fig. 2E and F). ZsGreen-negative vesicles in magnetically purified samples were most likely endo- and lysosomes that do not carry RCs. Some of these may originate with cells which were not infected at the time when magnetic beads were added to growth medium; at an MOI of 1, only approximately 60% of cells get initially infected. Furthermore, not all the cell lysosomes are carrying RCs even if the higher MOI is used (11, 24). Since the Mag fraction was strongly depleted by PM and ER markers (Fig. 2C), a majority of these structures could not originate with the ER or PM (Fig. 2C). Therefore, we can conclude that the fractions enriched with alphavirus replication organelles were successfully obtained through magnetic purification.

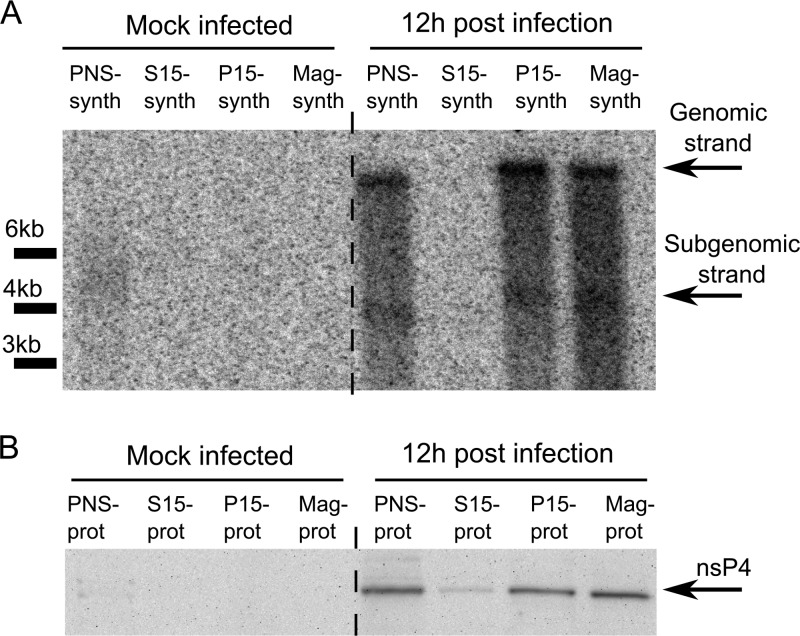

P15 fractions from alphavirus-infected cells synthesize viral RNAs, but subsequent fractionation of P15 samples by ultracentrifugation is associated with the loss of this function (58). Similarly, it has been shown for arteri- and coronoviruses that complexes purified using ultracentrifugation are inactive, since their activity is dependent on an essential soluble host factor that does not copurify with these complexes using differential centrifugation (61, 62). To assess whether magnetic purification also results in the loss of viral RNA synthesis, we performed an RNA synthesis assay in the presence of [α-32P]CTP. Consistent with previous reports, the P15 fraction from infected cells synthesized both genomic and SG SFV RNAs (Fig. 3A); no reduction in RNA synthesis (compared to findings for the PNS fraction) was detected. Relative to the level of the catalytic nsP4 subunit, a similar yield of RNA strands was also gained when the magnetically purified fraction (Mag-synth) was used in the assay (Fig. 3). Thus, magnetic enrichment, which uses mild treatments and is faster than ultracentrifugation-based fractionation, did not damage the RNA synthesis capacity of RCs.

Fig 3.

Viral RNA synthesis in the SFV replicase-containing fractions. (A) 32P-labeled RNAs produced by the PNS-synth, S15-synth, P15-synth, and Mag-synth samples from mock-infected and SFV-infected cells were separated on a denaturing 1% agarose gel and detected by autoradiography. Positions corresponding to viral genomic and SG RNAs are shown on the right, while positions of RNA length markers are shown at the left of the panel. (B) The relative levels of SFV nsP4 in the PNS-prot, S15, P15-prot, and Mag-prot samples detected by immunoblotting.

Identification of proteins overrepresented in the fraction containing alphavirus replicase organelles.

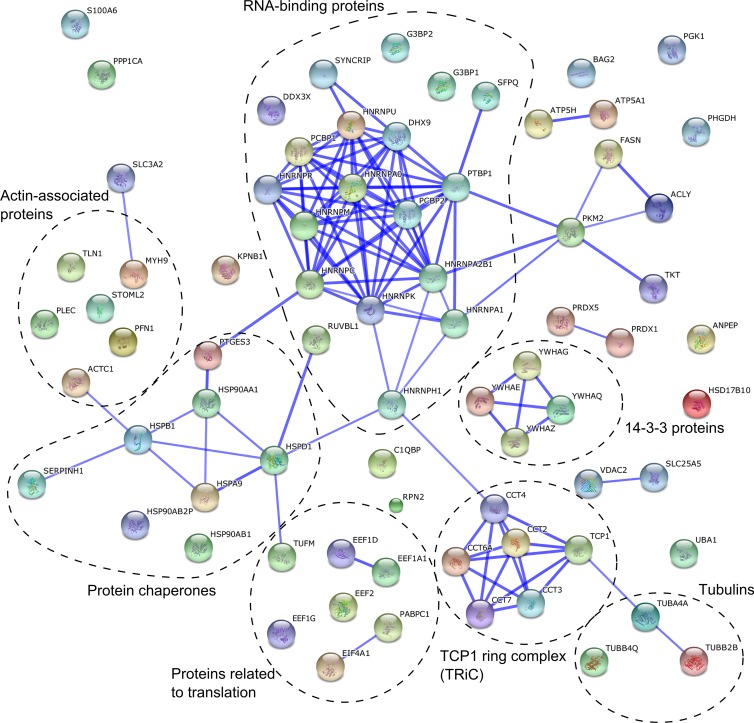

A SILAC-based gel-free quantitative proteomic method was employed to identify host proteins that were enriched in the SFV replication organelle-containing magnetically purified fraction. To increase the reliability of the results, reciprocal experiments were performed using heavy (H) and light (L) HeLa cells (see Materials and Methods). In the forward experiment, H-HeLa cells were infected and L-HeLa cells were mock infected, and in the reverse experiment, L-HeLa cells were infected and H-HeLa cells were mock infected (Fig. 2B). The experiment was performed three times: the forward experiment was performed twice, and the reverse experiment was performed once. The cells were harvested at 12 h p.i., which corresponds to the late stage of infection when large virus replicase organelles are formed around the nucleus but cells do not show major cytopathic effects. Next, magnetically purified fractions from the H-HeLa and L-HeLa cells were analyzed using mass spectrometry (Fig. 2B). The vesicular protein content was assessed using at least two unique peptides per protein. Since the presence of BSA in the samples did not allow signal normalization to the total protein content, the data obtained in each experiment were normalized to Lamp2, which is a standard marker for both lysosomes and SFV CPV-1s (10), to correct for any loss of sample during the purification procedures. Nearly 300 host proteins, including more than 50 lysosomal proteins, were identified in all three experiments (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Host proteins were considered to be associated with SFV replication organelles if they were on average (the geometrical mean of normalized data from three experiments) at least 2.5 times (cutoff value also used by Mannova and coworkers [45]) more abundant in the samples obtained from infected cells than in those from control cells. SFV-encoded proteins were not included in this list. Additionally, we excluded histones, which were considered potential contaminants, and ribosomal proteins, since we could not distinguish individual nsP-associated ribosomal proteins (60) from proteins that were part of the ribosomes engaged in the translation of viral mRNAs made by RCs (63). Seventy-eight proteins met all of our criteria, being comparable to the list of proteins identified in the study of HCV replicase organelles containing membranes (45). One-third of these proteins were RNA-binding proteins (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Some other proteins that we identified are involved in protein folding (e.g., HSP90AA1 and TCP1 ring complex), cytoskeleton (e.g., PFN1 and tubulins), and translation (Fig. 4). Notably, in contrast to findings in studies of materials from HCV- and coronavirus-infected cells (45, 46), we did not find any host proteins that decreased in abundance by a factor of 2.5 or more in the SFV CPV-1 fraction.

Fig 4.

Interaction network of proteins revealed by a gel-free proteomics approach. A network was created using the STRING database. The database was queried for host proteins that showed more than 2.5-fold enrichment in the vesicle fraction obtained from infected cells. The thickness of the blue lines between two nodes correlates with the confidence of the interaction between the proteins these nodes represent. The functional grouping of proteins is added to the graph.

Table 1.

Proteins enriched >2.5-fold in the viral replication organelle (CPV-1s) fraction obtained from SFV-infected cells by magnetic sorting and identified via comparative SILAC-based proteomic analysis

| Protein | Uniprot IDa | Fold enrichment | Previously found to be associated with alphaviruses (reference[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G3BP1 | Q13283 | 10.8 | Yes (19, 20, 25, 35, 42) |

| G3BP2 | Q9UN86 | 9.7 | Yes (19, 20, 25, 35, 42) |

| hnRNP M | P52272 | 5.1 | No |

| hnRNP A0 | Q13151 | 4.9 | Yes (19, 36) |

| DHX9 | Q08211 | 4.8 | No |

| hnRNP A2B1 | P22626 | 4.2 | Yes (19, 36) |

| hnRNP U | Q00839 | 4.2 | Yes (19, 36) |

| hnRNP H1 | P31943 | 4 | No |

| hnRNP R | O43390 | 4 | No |

| HSPB1 | P04792 | 4 | No |

| PTBP1 | P26599 | 3.8 | No |

| SYNCRIP | O60506 | 3.8 | No |

| SFPQ | P23246 | 3.7 | No |

| TUBB2C | P68371 | 3.6 | Yes (20) |

| hnRNP C | P07910 | 3.6 | Yes (36) |

| PPP1CA | P62136 | 3.6 | No |

| EEF1G | P26641 | 3.6 | No |

| hnRNP A1 | P09651 | 3.6 | Yes (19, 35, 36) |

| hnRNP K | P61978 | 3.5 | Yes (38, 41) |

| EIF4A1 | P60842 | 3.5 | Yes (36) |

| TUFM | P49411 | 3.5 | No |

| S100A6 | P06703 | 3.5 | No |

| PABPC1 | P11940 | 3.4 | Yes (41) |

| DDX3X | O00571 | 3.4 | No |

| TUBA4A | P68366 | 3.3 | Yes (20) |

| PCBP2 | Q15366 | 3.3 | No |

| TCP1 | P17987 | 3.2 | No |

| ACLY | P53396 | 3.2 | No |

| PHGDH | O43175 | 3.2 | No |

| TUBB2B | P07437 | 3.2 | Yes (20) |

| CCT2 | P78371 | 3.1 | No |

| PTGES3 | Q15185 | 3.1 | No |

| UBA1 | P22314 | 3.1 | No |

| ANPEP | P15144 | 3.1 | No |

| PCBP1 | Q15365 | 3 | No |

| PKM2 | P14618 | 3 | No |

| MYH9 | P35579 | 3 | Yes (19) |

| CCT4 | P50991 | 2.9 | No |

| BAG2 | O95816 | 2.9 | No |

| SLC25A5 | P05141 | 2.9 | Yes (41) |

| TKT | P29401 | 2.9 | No |

| EEF1D | P29692 | 2.9 | No |

| HS90A | P07900 | 2.9 | No |

| PGK1 | P00558 | 2.9 | No |

| CCT7 | Q99832 | 2.9 | No |

| YWHAQ | P27348 | 2.9 | Yes (20, 35) |

| C1QBP | Q07021 | 2.9 | No |

| CCT6A | P40227 | 2.9 | No |

| HSP90AB1 | P08238 | 2.8 | Yes (20) |

| HSP90AB2P | Q58FF8 | 2.8 | Yes (20) |

| TUBB4 | Q13509 | 2.8 | Yes (19, 20) |

| STOML2 | Q9UJZ1 | 2.8 | No |

| ATP5A1 | P25705 | 2.8 | Yes (20) |

| EEF2 | P13639 | 2.8 | Yes (35) |

| CKB | P12277 | 2.7 | No |

| LRPPRC | P42704 | 2.7 | No |

| TUBB4Q | Q3ZCM7 | 2.7 | Yes (19, 20) |

| RPN2 | P04844 | 2.7 | No |

| SERPH | P50454 | 2.7 | Yes (4) |

| EEF1A1 | P68104 | 2.7 | Yes (19, 36) |

| VDAC2 | P45880 | 2.7 | No |

| PRDX5 | P30044 | 2.7 | No |

| FASN | P49327 | 2.7 | No |

| KPNB1 | Q14974 | 2.7 | No |

| RUVBL1 | Q9Y265 | 2.7 | No |

| YWHAG | P61981 | 2.7 | Yes (20, 35) |

| YWHAZ | P63104 | 2.7 | Yes (20, 35) |

| ATP5H | O75947 | 2.6 | No |

| SLC3A2 | P08195 | 2.6 | No |

| PRDX1 | Q06830 | 2.6 | No |

| PFN1 | P07737 | 2.6 | No |

| TLN1 | Q9Y490 | 2.6 | No |

| ACTC1 | P68032 | 2.6 | No |

| HSD17B10 | Q99714 | 2.6 | No |

| HSPA9 | P38646 | 2.6 | No |

| CCT3 | P49368 | 2.5 | No |

| YWHAE | P62258 | 2.5 | Yes (20, 35) |

| PLEC | Q15149 | 2.5 | Yes (35) |

| HSPD1 | P10809 | 2.5 | No |

ID, identifier.

Several of the proteins identified in this study have previously been shown to be associated with alphavirus infection through alternative methods. The RNA-binding proteins G3BP1, G3BP2, hnRNP C, hnRNP K, and hnRNP A1 interact with ns proteins or genomic and SG RNAs of SINV (19, 35, 36, 38, 64); moreover, hnRNP K has been shown to bind CHIKV nsP2 (41). Thus, the SILAC-based proteomics approach is suitable for identifying cellular proteins that colocalize and/or interact with alphavirus RCs. It is noteworthy that the results from several research groups have revealed that some of these proteins, including PCBP1 and PCBP2, also participate in poliovirus (PV) and HCV infections (65, 66). Furthermore, a SILAC-based quantification showed that the G3BP1 and G3PB2 proteins are upregulated in the Golgi apparatus-enriched fraction from coronavirus-infected cells (46).

We found nearly 50 host proteins that were not previously known to colocalize with alphavirus RCs and that are most likely important for SFV replication (Table 1). Late in alphavirus infection, when RCs are fully formed and internalized and viral negative-strand RNA synthesis has terminated, the cellular proteins associated with RCs would be expected to be predominantly associated with the synthesis and utilization (i.e., translation, stabilization, and transport) of viral positive-strand RNAs. Therefore, it was not surprising that the RNA-binding proteins were particularly abundant in the list of cellular proteins identified (Fig. 4). We chose to analyze the impact of four of these RNA-binding proteins, PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K, on alphavirus infection. Of these proteins, hnRNP M exhibited the highest degree of enrichment, and PCBP1 exhibited the lowest degree of enrichment in the replicase organelles; hnRNP C and hnRNP K displayed intermediate degrees of enrichment (Table 1).

RNA-binding proteins colocalize with SFV replication organelles.

Alphavirus infection stimulates the relocalization of numerous host proteins, but this relocalization is not always directly related to viral replication. For example, the nsP2-mediated cessation of host transcription has been shown to cause nonspecific redistribution of different RNA-binding proteins in BHK-21 cells during the late stage of SINV infection. This relocalization was especially evident for hnRNPA0 and hnRNPA1 and was observed to a lesser degree for hnRNP K; however, no relocalization was observed for hnRNP C (67). Because all of these proteins were also detected in this study and others (Table 1), it was crucial to assess whether PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K colocalized with SFV replicase in infected HeLa cells.

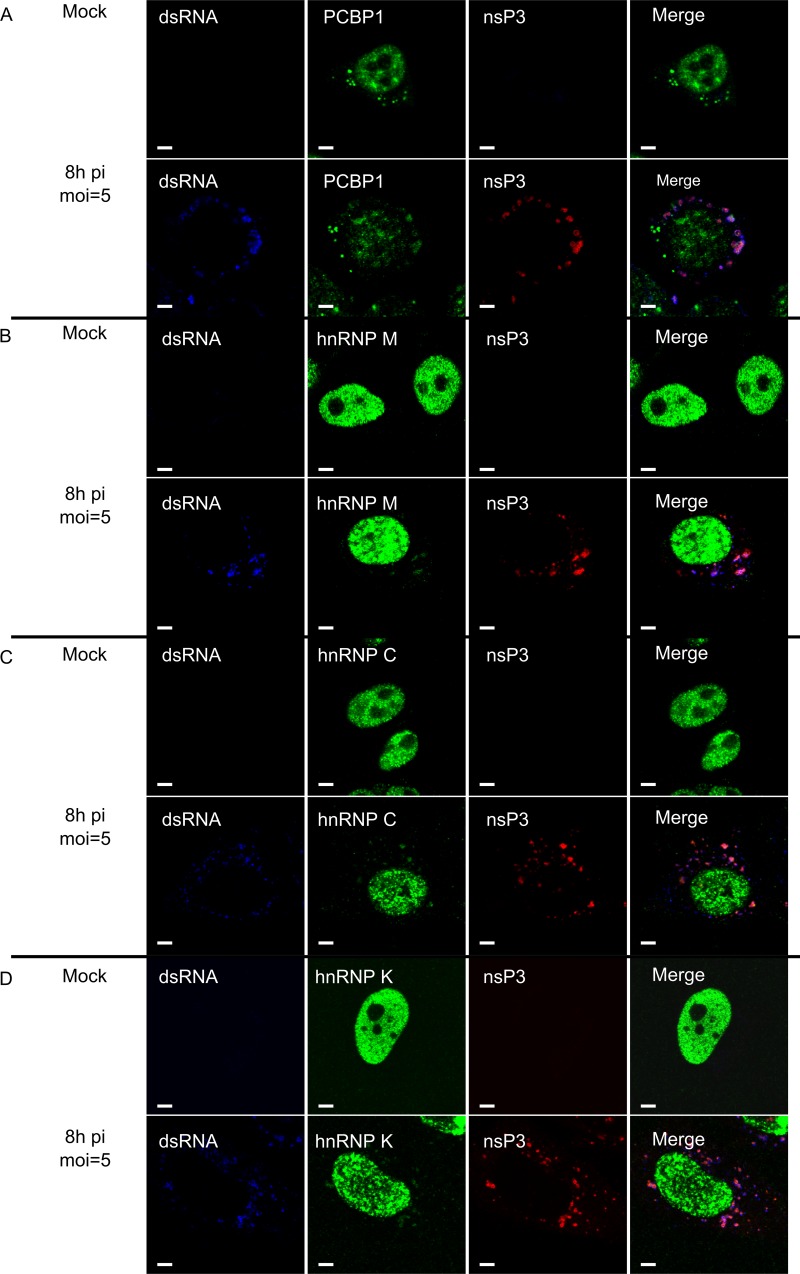

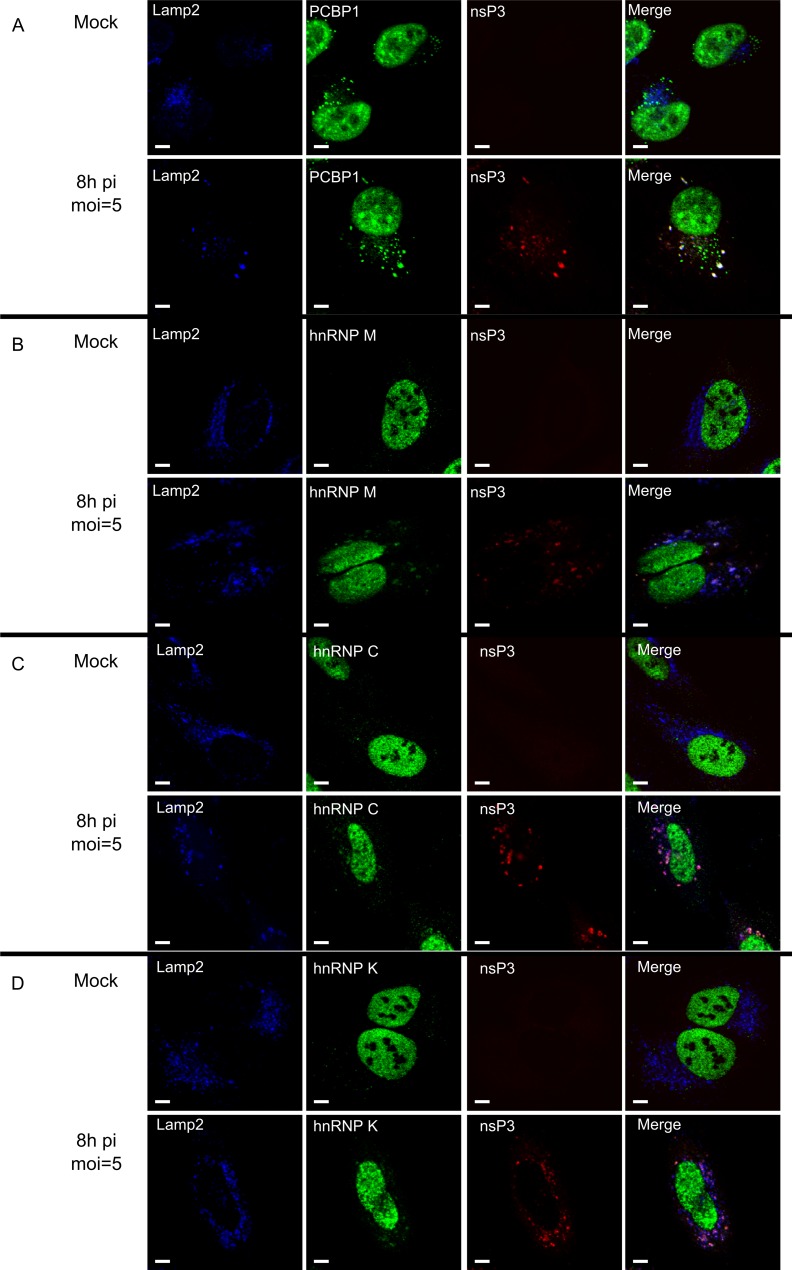

In uninfected cells, PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K localized predominantly to the nucleus; only PCBP1 also localized to cytoplasmic granular structures (Fig. 5A), consistent with its role in RNA granule biology (68). When HeLa cells were infected with SFV at an MOI of 5, a large-scale migration of any of these proteins from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was not detected at 8 h p.i. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic localization of these proteins was not diffuse, as observed for RNA-binding proteins relocalized due to the nsP2-mediated cessation of cellular transcription (67). Instead, a small but clearly detectable protein fraction was present in the cytoplasm, where the protein almost exclusively colocalized with dsRNA and SFV nsP3 at 8 h p.i. (Fig. 5) and 12 h p.i. (data not shown). The only exception was PCBP1, which was also detected in granule-like structures that were not colocalized with SFV nsP3 or dsRNAs, a finding that is consistent with the observations made with uninfected cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, in SFV-infected cells, PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K colocalized with the lysosomal Lamp2 protein (Fig. 6). In contrast, when cells were infected with UV-inactivated SFV, no changes in the localization of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K were observed (data not shown), confirming that relocalization was dependent on virus replication. Thus, the analyzed host proteins specifically colocalized with markers for viral replication organelles (CPV-1s) and with those of SFV RCs.

Fig 5.

PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K colocalize with SFV nsP3 and dsRNA. SFV-infected and mock-infected HeLa cells were fixed at 8 h p.i., permeabilized, and probed with antibodies for dsRNA (blue) and SFV replicase (anti-nsP3; red). The cells were also probed with anti-PCBP1 (A), anti-hnRNP M (B), anti-hnRNP C (C), or anti-hnRNP K (D) antibodies (all shown in green on the corresponding panels). Images were obtained using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. One optical slice is shown at each panel. White bars, 5 μm.

Fig 6.

Colocalization of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K with lysosomal marker Lamp2 and SFV nsP3. SFV-infected and mock-infected HeLa cells were fixed at 8 h p.i., permeabilized, and probed with antibodies for Lamp2 (blue) and SFV replicase (anti-nsP3; red). Cells were also probed with anti-PCBP1 (A), anti-hnRNP M (B), anti-hnRNP C (C), or anti-hnRNP K (D) antibodies (shown in green on the corresponding panels). One optical slice is shown at each panel. White bars, 5 μm.

Silencing of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, or hnRNP K expression affects SFV infection.

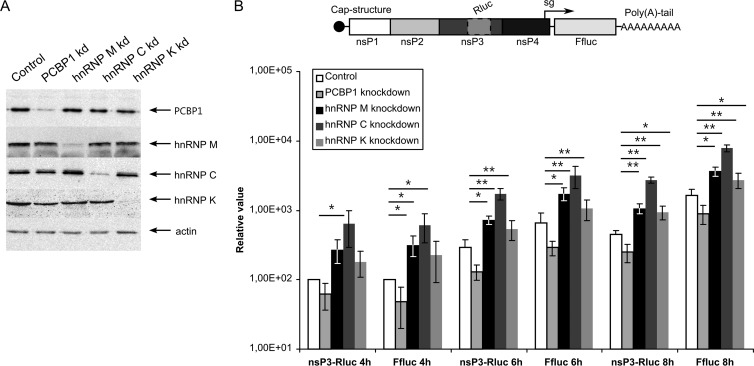

Although the migration of the RNA-binding host proteins from the nucleus to the viral replication organelles serves as an indicator of their roles in viral RNA metabolism, this migration does not reveal the functional significance of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, or hnRNP K in SFV infection. Therefore, we analyzed the effects of siRNA-mediated silencing of protein expression on SFV infection. To reduce unforeseeable off-target effects, mixtures of three siRNAs, each used at a low concentration, were used for every target. All four siRNA mixtures were highly efficient in reducing the expression levels of their expected targets at 48 h p.t., as determined by immunoblotting. In contrast, transfection with control siRNA did not affect the protein levels (Fig. 7A). None of the siRNA mixtures had cytotoxic effects on the transfected cells throughout the experiment (data not shown). All subsequent experiments aimed at revealing the effects of reduced levels of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, or hnRNP K on SFV infection were performed using HeLa cells at 48 h p.t.

Fig 7.

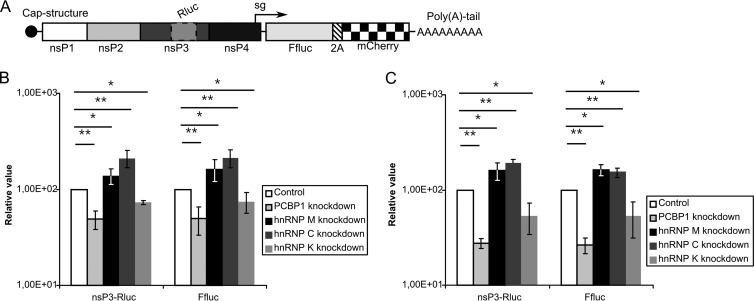

Effects of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing on SFV replicon vector. (A) Detection of the efficiencies of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing by respective siRNAs; negative control, cells transfected with control siRNA. The targeted proteins in the transfected HeLa cells at 48 h p.t. were detected by immunoblotting, and actin served as a loading control. (B) Top, schematic representation of the SFV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc replicon. Bottom, Rluc and Ffluc activities from siRNA-transfected HeLa cells infected with VRPs containing the SFV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc replicon at an MOI of 0.01. The cells were collected at 4, 6, and 8 h p.i., and the measured Rluc and Ffluc activities were normalized to those from control siRNA-treated cells at 4 h p.i. (set to 100). The mean values of four independent experiments are presented on the graph. Error bars indicate standard deviations. “∗” and “∗∗” denote statistical significance: P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

First, siRNA-transfected cells were infected with SFV VRPs at an MOI of 0.01. The SFV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc replicons used in this assay expressed Rluc fused to nsP3 from genomic RNA and Ffluc from mRNAs synthesized from the SG promoter (Fig. 7B), allowing accurate estimation of virus-mediated gene expression for both RNAs. This replicon design was chosen because hnRNP K specifically binds to SG but not genomic SINV RNA, suggesting that it may participate in SG RNA transcription (38). PCBP1 silencing resulted in an approximately 2-fold reduction in Rluc and Ffluc expression throughout the experiment (Fig. 7B). In contrast, hnRNP M or hnRNP C silencing significantly increased the amounts of both markers throughout the experiment; expression levels increased approximately 3-fold and 5-fold in hnRNP M- and hnRNP C-silenced cells, respectively (Fig. 7B). Thus, whereas the presence of PCBP1 positively impacted SFV infection, hnRNP M and hnRNP C acted as negative regulators. The effect of hnRNP K silencing reached statistical significance only at 8 h p.i., when both Rluc and Ffluc activities were approximately 2-fold higher than in cells transfected with control siRNA. Thus, hnRNP K had the least impact on SFV infection. Furthermore, knocking down each analyzed host protein affected the expression of markers from both ns and structural regions of the SFV to the same extent, indicating that PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K do not affect the synthesis and/or translation of SG RNAs specifically.

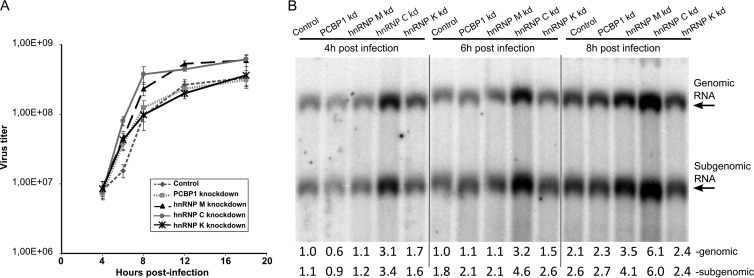

To assess the effects of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, or hnRNP K on the production of infectious virions, one-step growth-curves were obtained using siRNA-transfected HeLa cells infected with SFV at an MOI of 5. A comparison of these curves revealed that hnRNP M silencing accelerated SFV multiplication and increased the final SFV titers 3- to 4-fold. The effect of hnRNP C silencing was even more evident; by 6 h p.i., the titer of virus released from the cells transfected with the corresponding siRNAs was approximately four times higher than the titer obtained from control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 8A). These data are consistent with the prominent effect that silencing those proteins has on SFV replicon-mediated protein expression (Fig. 7B). The effects of PCBP1 or hnRNP K silencing on viral multiplication could not be detected using the one-step growth curve assay, which is consistent with the smaller effects of the corresponding knockdowns observed in the previous experiment (Fig. 7B).

Fig 8.

Effects of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing on SFV replication. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs 48 h prior to infection with SFV at an MOI of 5. (A) One-step growth curves of SFV in transfected cells. Aliquots of growth medium were collected at 4, 6, 8, 12, and 18 h p.i., and the virus titer was determined by a plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated at 4, 6, and 8 h p.i. A 5-μg sample of the total RNA was separated on a denaturing agarose gel. A probe complementary to the SFV 3′ UTR was used to detect genomic and SG RNAs. The results of quantification (shown below the panel) were normalized to the amount of genomic RNAs in control siRNA-transfected cells at 4 h p.i., which was taken as 1 (1). The experiment was repeated three times; data from one representative experiment are shown.

The expression of reporter proteins (Fig. 7B) and the release of infectious virus progeny (Fig. 8A) depend on virus entry, viral RNA synthesis, and protein translation. To study the effects of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing on SFV entry, we used VRPs containing SFV-EGFP replicons. Since the number of EGFP-positive cells remained unchanged, we concluded that none of these proteins has a significant effect on the early stages of SFV infection (data not shown). To study the effects of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing on SFV replication, RNA samples from infected HeLa cells were analyzed by Northern blotting. In line with the data from previous experiments, hnRNP C silencing increased the synthesis of both genomic and SG RNAs; this effect was detectable as early as 4 h p.i. (Fig. 8B). In hnRNP M-silenced cells, the increase in viral RNA production was less prominent and became clearly detectable only at 8 h p.i. Consistent with the one-step growth curve, silencing of PCBP1 or hnRNP K did not exhibit long-lasting effects on SFV RNA synthesis (Fig. 8B). Nevertheless, a small reduction in RNA replication was detected in PCBP1-silenced cells at 4 h p.i., whereas silencing of hnRNP K expression resulted in a slight activation of SFV replication at both 4 and 6 h p.i. (Fig. 8B). Although these effects were small, these findings do correlate with the trends observed in the VRP experiments (Fig. 7B).

Taken together, the data obtained from hnRNP C silencing experiments indicated that the protein was involved in suppressing viral RNA synthesis, which affects the expression of viral proteins and ultimately viral growth. The effects of hnRNP M silencing were similar except that no effect on RNA replication was detected at 4 or 6 h p.i. (Fig. 8B); nevertheless, an effect on viral gene expression was readily observed using the reporter-based assay at these time points (Fig. 7B). This discrepancy is most likely attributable to the higher sensitivity of the reporter-based assay when performed using a low MOI; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that hnRNP M silencing also could result in enhanced viral RNA translation. With the exception of the replicon-based assay (at 8 h p.i.), hnRNP K silencing did not significantly affect SFV multiplication (Fig. 7B and 8A and B). The PCBP1 silencing data were the least consistent, since PCBP1 silencing clearly reduced the expression of both markers with the replicon vector (Fig. 7B), but did not significantly affect viral growth (Fig. 8A) and had only a minor, transient effect on viral RNA synthesis (Fig. 8B). Again, this discrepancy may be attributable to the higher sensitivity of the low-MOI replicon-based assay.

Silencing of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, or hnRNP K expression also affects SINV and CHIKV infections.

The Alphavirus genus is rather heterogeneous and is divided into several serogroups. SFV belongs to the same serogroup as CHIKV, whereas SINV belongs to a different serogroup (1). The RCs and CPV-1s, as well as the pathways used for the biogenesis of RCs and CPV-1s, are similar between SFV and SINV (24, 25). The sets of host proteins that interact or colocalize with the SFV and SINV replicases also clearly overlap (Table 1). However, these observations do not unequivocally indicate that all cellular factors affect the infection cycles of different alphaviruses in the same manner. To assess whether the RNA-binding proteins found to colocalize with the SFV replicase also participate in SINV or CHIKV infection, CHIKV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry and SINV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry replicon vectors were constructed. Similar to SFV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc replicons, these replicons expressed Rluc and Ffluc markers, but they also expressed the fluorescent protein mCherry (Fig. 9A), permitting the titration of corresponding VRPs without the use of CHIKV- or SINV-specific antibodies. The assay using siRNA-transfected cells was performed as described above, except that luciferase activities were measured only at 8 h p.i., since this time point was the only one at which hnRNP K silencing yielded statistically significant effects with the SFV replicon (Fig. 7B). PCBP1, hnRNP C and hnRNP M silencing affected SINV and CHIKV infection in the same way as SFV infection; however, the effects of silencing these proteins were less prominent than for SFV (compare Fig. 7B and Fig. 9B and C). In contrast, the effect of hnRNP K silencing on CHIKV and SINV infection was opposite to that observed for SFV (compare Fig. 7B and 9B, 9C). Thus, consistent with previous publications (38, 41), hnRNP K was found to function as an activator for CHIKV and SINV infections, whereas it functioned as a repressor for SFV infection.

Fig 9.

PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K silencing affects CHIKV and SINV replicons. (A) A schematic representation of the CHIKV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry and SINV-nsP3-Rluc-SG-Ffluc-2A-mCherry replicon RNAs. (B and C) The expression of PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K was knocked down by the indicated siRNAs, and the cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01 with CHIKV (B) or SINV (C) VRPs 48 h later. The cells were collected at 8 h p.i. The measured Rluc and Ffluc activities were normalized to those from the control siRNA-treated cells (set to 100). The experiments were repeated four times, and the error bars represent standard deviations. “∗” and “∗∗” denote statistical significance: P values of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

DISCUSSION

To exert a variety of biological functions fully, viruses require the engagement of factors encoded by the host. Similarly, every host has numerous components that directly or indirectly limit viral growth. Several of these components exhibit prominent qualitative effects on viral infection, whereas the effects of others may be minor and difficult to detect. Although the currently available data indicate that positive-strand RNA viruses preferentially target conserved host functions and proteins, a large fraction of the host proteins that are subverted is unique to each virus (reviewed in references 33 and 34). Host components and viral factors form a complex interaction network, thus complicating our understanding of the virus-host interplay.

Changes in protein levels in cellular compartments that upon viral infection become virus replication organelles are more likely to occur if a protein is somehow involved in virus replication. In this study, we identified host proteins that colocalize with mature SFV RCs and that may affect their function. In previous studies, immunoprecipitation of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged nsP2 or nsP3 was used to identify their interaction partners (19, 35, 36, 42). However, this approach does not differentiate between host proteins associated with RCs and those associated with individual nsP2 and nsP3. To overcome this limitation, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using FLAG-tagged SINV nsP4, with the assumption that mature, unincorporated nsP4 is unstable (9, 20). However, in practice, the SINV P34 polyprotein, which is not processed into individual nsP3 and nsP4 proteins, accumulates at late stages of infection (69, 70). P34 may be excluded from RCs, but both of its parts are able to interact with cellular proteins. Moreover, P34 was the predominant form of nsP4 immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG antibodies. Therefore, the list of host proteins identified in the study of FLAG-tagged SINV nsP4 was similar to the panel of proteins obtained from the immunoprecipitation experiments with viruses expressing tagged nsP3 (35). In contrast, there is only a small overlap between the lists of host proteins that bind nsP2 identified by pull-down (36) or genome-wide yeast two-hybrid screening (41). Such a discrepancy is common for most if not all viruses (34) and indicates that neither of the approaches identifies all of the players that are important for virus-host interactions. Therefore, alternative approaches are necessary.

The difficulties in isolating viral replication organelles with retained RNA-synthesizing capability have limited the application of quantitative proteomics to the studies of intact viral replication complexes. In this study, we took advantage of a unique property of alphaviruses: their RCs form on the PM, are then internalized via endocytosis (24, 25), and finally localize to large vesicles of endolysosomal origin, which are the virus replication organelles called CPV-1s (Fig. 1). We demonstrated that dextran-covered magnetic beads were incorporated into lysosomes, permitting the collection of these specific vesicles via magnetic enrichment. This approach has been successfully used to identify new proteins that participate in endocytosis, namely, flotillins (59), and to study receptor-driven endocytosis (71); however, to the best of our knowledge, it has not been applied in studies of viral infections. To compare CPV-1s and lysosomal vesicle components from uninfected cells, we employed the gel-free SILAC-based proteomics approach.

Not all of the lysosomes isolated from alphavirus-infected cell culture represented virus replication organelles (Fig. 2F). At an MOI of 1, approximately 40% of cells are not immediately infected but can endocytose magnetic beads. In addition, some lysosomes formed in infected cells may not carry RCs. On the other hand, magnetic isolation has an advantage over ultracentrifugation-based separation, since lysosomes, which exist prior to cell feeding, would not be present in the purified samples unless they fuse with endosomes formed after the addition of magnetic beads. Consequently, this approach cannot be applied in studies of early-stage SFV infection, during which the CPV-1s have not yet been formed; thus, only the cells at later stages of infection could be analyzed. This method resulted in rapid and efficient purification of organelles that not only contain SFV ns proteins (Fig. 2C) but also carry them in the form of functional RCs capable of viral RNA synthesis (Fig. 3A). Notably, mature alphavirus RCs synthesize only positive-strand RNAs; hence, purified replication organelles may not carry specific host components that are important for the early stages of infection, such as RNA template recruitment, cellular membrane remodeling, and viral negative-strand RNA synthesis. An additional limitation of this experimental scheme is the inability to identify all host factors that directly interact with SFV replicase components, since the amounts of some of these factors may not be substantially increased in CPV-1s compared to normal lysosomes. Similarly, whether proteins identified by this method interact directly with SFV nsPs and/or RNA molecules remains unknown.

In contrast to previous studies of the proteome of lipid rafts in HCV-infected cells and Golgi apparatus-enriched membrane fractions during coronavirus infection (45, 46), we did not identify any proteins that were downregulated by a factor of 2.5 or more in CPV-1s. This result is consistent with the observation that approximately 40% of vesicles in magnetically purified samples did not contain SFV RCs (Fig. 2F). However, the lack of downregulated proteins may also reflect a specific property of the alphavirus replicase organelles. It is noteworthy that in a very recent study of the total proteome of CHIKV-infected cells, only 8 cellular proteins were found to be upregulated while 37 were downregulated (27). Furthermore, only three proteins, including PCBP1 and hnRNP C, were identified in both our and their studies. Thus, changes in the total proteome of infected cells and those in cellular compartments converted to virus replication organelles are different. Clearly, the method used in this study allowed the identification and quantification of numerous proteins overrepresented in the lysosomal membranes of infected cells that may interact with SFV nsPs or RNAs at later stages of infection or that may otherwise affect viral infection. Indeed, several proteins identified by this approach have been previously shown to be associated with SINV replication, including G3BP1, hnRNP A1, and hnRNP U (Table 1). Thus, the results of previous studies of alphavirus replicase complexes validate the results obtained using our approach and vice versa.

With all genome-wide screens, there are concerns regarding the biological relevance of the findings. For alphaviruses, yeast two-hybrid screens led to the highly confident identification of 22 interactions, but only two of these proteins were found to affect viral replication in cell culture (41). In contrast, all of the proteins that were selected for additional analysis in this study affected SFV infection. For example, hnRNP C silencing resulted in a 4-fold increase in SFV multiplication and a 5-fold increase in SFV gene expression (Fig. 7B and 8A and B). These findings can also be considered successful in the context of published proteomics studies of virus replication organelles. Of the five proteins selected for functional analysis by Mannova and colleagues, three affected HCV replication, and the effect was always less than 2-fold (45). In the case of coronavirus infection, 2 of the 13 analyzed proteins affected viral replication, and these proteins altered viral replication by less than 2.5-fold (46). We cannot rule out the possibility that the proteins studied here had strong effects on alphavirus infection by pure chance or due to the specific selection of RNA-binding proteins. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the purification and subsequent analysis of functional replication organelles of positive-strand RNA viruses has benefits over simply separating and analyzing replication-associated membranes from infected cells. Although the exact method used in this study is not applicable outside the Togaviridae family, advanced methods allowing the efficient isolation of different cells and/or cellular organelles are emerging (72, 73) and can be adopted for the isolation of virus replication organelles.

Many host proteins involved in the regulation of RNA synthesis of positive-strand RNA viruses are conserved cellular RNA-binding proteins (discussed in references 32 to 34). Such proteins were also abundant in the list of putative alphavirus replication organelle-associated host proteins (Fig. 4). Due to the specificity of our approach (see above), we reasoned that these proteins may affect the later stages of alphavirus infection. Therefore, PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K were chosen for further experiments. The selection of these proteins was based not only on their relative enrichment in the samples from virus-infected cells (Table 1) but also because these proteins are associated with the replication of other positive-strand RNA viruses, including dengue virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), enterovirus 71, PV, and HCV (66, 74–79). Furthermore, these proteins form parts of larger, multiprotein complexes and have numerous functional connections (Fig. 4). Thus, information regarding the effects of silencing of the selected proteins also provides insight into the significant and complex role of the hnRNPs in alphavirus replication in general (80, 81).

Many host RNA-binding proteins that are important for positive-strand RNA virus replication have natural functions unrelated to viral RNA synthesis (82, 83). In uninfected cells, PCBP1 and PCBP2 localize to nuclei, where they regulate splicing and mRNA stability (83), and these proteins are also found in processing bodies (68). These proteins have been thoroughly studied in the context of PV infection, where PCBPs were shown to bind to the 5′ cloverleaf-like structure and an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) located in the 5′ UTR of the PV genome (78, 84). Furthermore, they interact with functional viral proteins, and both are cleaved by viral 3C/3CD protease during infection. The cleaved form of PCBP2 facilitates the switch from viral RNA translation to viral RNA replication (65). Based on this phenomenon, we also assayed whether PCBP1 was cleaved in SFV-infected cells and found that this was not the case. Similar results were obtained for hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K, none of which was found to be cleaved or degraded to any detectable extent during the course of SFV infection (data not shown).

Confocal microscopy analysis confirmed that PCBP1, hnRNP M, hnRNP C, and hnRNP K were in the vicinity of SFV RCs (Fig. 5 and 6), reaffirming that their relocalization during the late phase of SFV infection is not random. siRNA-mediated silencing of hnRNP C and hnRNP M in HeLa cells increased SFV gene expression and replication (Fig. 7B and 8A and B). This positive effect was unexpected because hnRNP C has been shown to be essential for PV replication, possibly by maintaining the 3′ end of negative-strand PV RNA in a single-stranded form (79, 85). Whether hnRNP C exerts similar effects in the context of alphavirus infection remains to be determined. Moreover, the fact that silencing of hnRNP C has positive effects on viral RNA synthesis (Fig. 8B) has yet to be addressed. Conversely, PCBP1 silencing reduced the synthesis of reporter proteins expressed both from genomic and SG RNAs of the SFV replicon but failed to affect or only minimally affected viral RNA synthesis and SFV growth in cell culture (Fig. 7B and 8A and B). These effects were also observed when SINV- and CHIKV-based replicons were used instead of SFV (Fig. 9). Thus, similar to the case with PV, PCBP1 is also required for efficient infection by different alphaviruses. However, since alphavirus genomes lack 5′ cloverleaf-like structures and IRES elements, the mechanism by which PCBP1 contributes to infection by these viruses is likely different from that used during PV infection. In contrast, the results obtained using cells with reduced hnRNP K levels indicated that this protein had little impact on the RNA synthesis and multiplication of SFV, but hnRNP K deficiency suppressed SINV and CHIKV infections (Fig. 9), as reported previously (38, 41). Thus, not all host proteins analyzed in this study affected different alphaviruses in the same way. One possible explanation for this observation is that the effect of hnRNP K on alphavirus replication may depend on its concentration; the protein may act as an inhibitor at certain concentrations and as an activator at other concentrations. Moreover, these concentrations may not be identical for different alphaviruses. Alternatively, the localization and sequences of specific regions within the genomic RNA that hnRNP K utilizes for binding may vary among different alphaviruses, resulting in diverse effects.

Importantly, our experimental approach led to the identification of two host proteins, hnRNP M and hnRNP C, as factors that restrict alphavirus replication. This finding parallels the results of a recent study by Cristea et al. (20), which showed that silencing of two replicase interactors, G3BP1 and G3BP2 (which we identified as proteins that were most enriched in SFV viral replication organelles) (Table 1), allowed for more efficient SINV replication. Therefore, we can conclude that numerous host factors localized to viral replication organelles actually limit viral replication rather than facilitating it (20). This conclusion is further supported by the results of quantitative proteomics-based studies of HCV and coronavirus replication-associated membranes; the silencing of identified proteins more often resulted in the activation of viral replication (45, 46). Thus, the presence of a large number of proteins that limit viral replication in virus replicase organelles may be a tendency shared by positive-strand RNA viruses. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that these proteins may represent novel antiviral factors that the cell uses against positive-strand RNA viruses. A recent finding that hnRNP C is upregulated in CHIKV-infected cells (27) is coherent with this hypothesis. However, the presence of inhibiting factors is not necessarily disadvantageous for viruses. Such proteins may represent the factors that viruses use to control the infection process; for example, these proteins may be used to switch from the translation of the genomic RNA to viral replication. The changes in the amounts of these host proteins may result in changes in the balance of different viral activities and thus affect virus production. The additional value of the restriction of viral replication can be used by viruses to establish persistent infection. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of action of these proteins and to further detail their significance in alphavirus infection.

Notably, regardless of the method used to assess alphavirus-interacting host proteins (or, in the case of this study, alphavirus replicase-colocalizing host proteins), several RNA-binding proteins, including many hnRNPs, are reproducibly identified as interactors. hnRNPs harbor a wide spectrum of functions, ranging from the regulation of mRNA transcription to the regulation of mRNA localization (82, 83). Furthermore, despite common structural elements, each hnRNP displays different functions. Correspondingly, it is difficult to precisely predict how these proteins affect viral RNA replication. Nonetheless, an increasing number of publications indicate that many hnRNPs play important roles in the replication not only of alphaviruses but also of RNA viruses in general. Additionally, different viruses use different host proteins to achieve similar goals (for excellent recent reviews, see references 33 and 34). Our study contributes to this understanding by revealing that different viruses may also use the same cellular proteins for different purposes. Thus, although our knowledge is incomplete concerning the effects that these proteins exhibit on different viruses, it is clear that the results obtained with one virus are not always transferable to another virus, even when the viruses are closely related. Similarly, proteins from different hosts may have different effect on the virus. For example, it has been recently shown that the human nsP2 interacting protein NDP52 reduces nuclear localization of CHIKV nsP2 and limits cell shutoff induced by nsP2 while mouse NDP52 lacks these functions (86). Taken together, these results also challenge the popular view that cellular proteins that affect viral replication represent potential targets for novel antiviral therapies. The divergent functions of many of these proteins during infections with different viruses suggest more cautious approaches, since inhibitors that could suppress the replication of some viruses may instead activate the replication of others. Additional studies to determine the exact mechanisms of action of cellular factors that positively and negatively regulate viral replication are thus needed before the putative anti- or proviral potentials of these targets can be harnessed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research described in this article was funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement no. 261202 (ICRES), the Estonian Science Foundation, grant 7407, and the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund via the Center of Excellence in Chemical Biology in Estonia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 July 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01105-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Strauss JH, Strauss EG. 1994. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 58:491–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney M-C, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes J-M, Pettinelli F, Biscornet L, Diancourt L, Michel S, Duquerroy S, Guigon G, Frenkiel M-P, Bréhin A-C, Cubito N, Desprès P, Kunst F, Rey FA, Zeller H, Brisse S. 2006. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 3:e263. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merits A, Vasiljeva L, Ahola T, Kääriäinen L, Auvinen P. 2001. Proteolytic processing of Semliki Forest virus-specific non-structural polyprotein by nsP2 protease. J. Gen. Virol. 82:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Golubtsov A, Sizemskaja V, Kääriäinen L, Ahola T. 2003. Regulation of the sequential processing of Semliki Forest virus replicase polyprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41636–41645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lulla A, Lulla V, Tints K, Ahola T, Merits A. 2006. Molecular determinants of substrate specificity for Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protease. J. Virol. 80:5413–5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lemm JA, Rümenapf T, Strauss EG, Strauss JH, Rice CM. 1994. Polypeptide requirements for assembly of functional Sindbis virus replication complexes: a model for the temporal regulation of minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis. EMBO J. 13:2925–2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shirako Y, Strauss JH. 1994. Regulation of Sindbis virus RNA replication: uncleaved P123 and nsP4 function in minus-strand RNA synthesis, whereas cleaved products from P123 are required for efficient plus-strand RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 68:1874–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]