Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) alters the regulation and expression of a variety of cytokines in its host cells to modulate host immune surveillance and facilitate viral persistence. Using cytokine antibody arrays, we found that, in addition to the cytokines reported previously, two chemotactic cytokines, CCL3 and CCL4, were induced in EBV-infected B cells and were expressed at high levels in all EBV-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). Furthermore, EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1)-mediated Jun N-terminal protein kinase activation was responsible for upregulation of CCL3 and CCL4. Inhibition of CCL3 and CCL4 in LCLs using a short hairpin RNA approach or by neutralizing antibodies suppressed cell proliferation and caused apoptosis, indicating that autocrine CCL3 and CCL4 are required for LCL survival and growth. Importantly, significant amounts of CCL3 were detected in EBV-positive plasma from immunocompromised patients, suggesting that EBV modulates this chemokine in vivo. This study reveals the regulatory mechanism and a novel function of CCL3 and CCL4 in EBV-infected B cells. CCL3 might be useful as a therapeutic target in EBV-associated lymphoproliferative diseases and malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

The first documented human oncogenic virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), is associated with several lymphocyte disorders, including infectious mononucleosis, Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, T cell lymphoma, NK cell lymphoma, AIDS-associated lymphomas, and posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) (1). In vitro, EBV has the ability to immortalize primary B cells, generating lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). EBV-immortalized LCLs are characterized by several features, including the aberrant production of cytokines and chemokines, unlimited proliferation, and a clumping morphology. Spontaneous reactivation to lytic progression is observed in approximately 5 to 10% of LCLs. These pieces of evidence indicate that EBV infection of B cells may create a favorable microenvironment for immortalization and the formation of lymphomas (1).

EBV has a DNA genome of 172 kb that encodes nearly 100 genes (1). EBV preferentially infects B cells. The life cycle of EBV is biphasic with latent and lytic stages. In the latent stage, the EBV genome remains episomal and its expression is limited. The products include six EBNAs (EBNA1, -2, -3A, -3B, -3C, and -5), three latent membrane proteins (LMPs; LMP1, -2A, and 2B), two small RNAs (EBER-1 and -2), and BamHI-A rightward transcripts (BARTs). In vitro, EBV lytic replication can be activated in latently infected cells by various stimuli, such as tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate, sodium butyrate, and immunoglobulin cross-linking (1). In vivo, EBV remains latent in healthy, infected individuals; however, lytic cycle progression often occurs in the immunocompromised.

Among the EBV-encoded products, LMP1 and LMP2A are two well-known membrane proteins that trigger an array of cellular signaling (2). Functionally, LMP1 mimics the constitutively activated ligand-independent CD40 and LMP2A can hijack the downstream effectors of the B cell receptor (BCR) (2). Thus, LMP-mediated changes of host gene expression are crucial for B cell survival, differentiation, proliferation, and immortalization (2). This not only benefits their replication but also contributes to virus-induced oncogenesis.

There is a broad spectrum of virus-encoded human chemokine homologues. For example, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes CXCL-2, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) encodes CCL4, and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes CCL1, CCL2, and CCL3 (3). Although no human chemokine homologue is found among the proteins encoded by EBV, the upregulation of chemokines has been reported in various states of EBV infection: (i) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, engagement of gp350/220 of EBV and the EBV receptor CD21 inhibits CCL3 production (4). (ii) In monocytes, EBV virions recognized by Toll-like receptor 2 trigger the induction of CCL3, CCL4, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and interleukin-8 (IL-8) (5). (iii) In purified tonsil B cells, CCL20, CCL19, CCL11, CCL24, CCL1, CCL13, and CCL5 are induced at days 2 to 7 postinfection (6). (iv) In our study of purified peripheral B cells, CCL3, CCL4, and IL-8 were shown to be significantly upregulated by EBV infection at day 7 postinfection. (v) Significant amounts of CCL22 are expressed in the sera of patients with infectious mononucleosis (7). (vi) In EBV-transformed LCLs, this and a previous study have shown that CCL3, CCL4, and CCL22 are constitutively expressed at high levels but CCL5 and CCL17 remain at low levels (8).

CCL3 and CCL4 belong to the CC chemokine subfamily and are also well-known to be the macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) and MIP-1β, respectively. In this study, we systematically analyzed the expression of chemokines during EBV immortalization and demonstrate that EBV induces high-level expression of CCL3 and CCL4 in primary B cells. Both chemokines are also produced by EBV-immortalized LCLs. We have shown that LMP1-mediated Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) activation plays a critical role in the induction of CCL3 and CCL4 expression. Blocking these two chemokines significantly suppresses cell proliferation and causes the death of LCLs, suggesting that CCL3 and CCL4 may constitutively deliver proliferating and survival signals in LCLs. Furthermore, CCL3 levels are significantly elevated in EBV-positive plasma from posttransplantation patients compared to the levels in EBV-negative control patients. Taken together, our results indicate that LMP1 induces a unique CCL3 and CCL4 autocrine loop that promotes the development of EBV-associated lymphomas and lymphoproliferative diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of CD19-positive B cells for EBV infection.

Isolation of B cells was described in our previous paper (9). Purified B cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in 12-well plates with 1 ml RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum plus 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and then infected with the EBV stock at a 100-fold dilution.

Cytokine antibody array.

Supernatants of EBV-infected or uninfected CD19-positive B cells were collected on the 7th day postinfection and applied to RayBio human cytokine antibody array 7 (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell lines and treatments.

Akata is an EBV-negative Burkitt's lymphoma cell line. L428 cells were derived from Hodgkin's lymphoma. Establishment of LCLs was described in our previous paper (9). HEK293T is a human embryonic kidney cell line, and TW01 is a nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line. HEK293T and TW01 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum plus 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. In the assays of inhibitor treatments, LCLs and HEK293 transfectants were treated with 5 to 25 μM JNK inhibitor (SP600125; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or 1 to 10 μM NF-κB inhibitor (BAY11-7082; Merck).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR.

Extraction of total cellular RNA and synthesis of cDNA were described in our previous paper (9). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA was detected using TaqMan primer/probe sets (predeveloped assay reagents; Applied Biosystems). CCL3 mRNA was detected using forward primer 5′-CAGAATTTCATAGCTGACTACTTTGAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCTTCGCTTGGTTAGGAAGA-3′, in combination with Roche Universal Probe Library probe 71 (Roche Diagnostics Corp., IN). CCL4 mRNA was detected using forward primer 5′-CTTCCTCGCAACTTTGTGGT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CAGCACAGACTTGCTTGCTT-3′, in combination with Roche Universal Probe Library probe 20.

Western blotting and antibodies.

Cell lysate collection, antibodies (anti-Rta, anti-EBNA1, and anti-LMP2A antibodies), and Western blotting were described in our previous paper (9). The proteins of interest were detected by the use of specific antibodies against GAPDH (Biodesign, Memphis, TN), LMP1 (Dako, Denmark), caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., MA), and poly(ADP ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), phospho-IκBα (Cell Signaling), phospho-JNK (Cell Signaling), β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

ELISA.

CCL3 and CCL4 protein concentrations in the culture supernatants were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids.

The plasmids for expression of EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A, and Rta and their control vector, pSG5, were described in our previous report (9). The plasmids expressing lentivirus-based full-length LMP1 (pSIN-LMP1) and truncated LMP1 (pSIN-LMP1ΔCTAR1, pSIN-LMP1ΔCTAR2, and pSIN-LMP1ΔCTAR1+2) were described in our previous paper (10). Plasmids expressing the lentivirus-based constructs shLMP1, shLuciferase, and shCCL3 were constructed by insertion of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) fragments into the pLKO.1 plasmid through the 5′ AgeI and 3′ EcoRI sites. The shRNAs were targeted to the sequences 5′-GCTCATTATTGCTCTCTAT-3′ of LMP1, 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCT-3′ of luciferase, 5′-CGGTGTCATCTTCCTAACCAA-3′ of CCL3-3, 5′-CAACCAGTTCTCTGCATCACT-3′ of CCL3-4, and 5′-TTCGATTTCACAGTGTGTTTG-3′ of CCL3-6. A series of luciferase reporter plasmids driven by the CCL3 promoter (nucleotides −980 to +102, −637 to +102, −256 to +102, and −124 to +102) or CCL4 promoter (nucleotides −935 to +79, −221 to +79, −107 to +79, and −88 to +79) fragment were inserted into the pGL2-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI) through the 5′ KpnI and 3′ BglII sites. To construct the pCCL3 (nucleotides −980 to +102) mutated reporter plasmid, the putative AP-1 site (TTGGATA) within the CCL3 promoter region (nucleotides −139 to −133) was mutated to AAAGATT by site-directed mutagenesis. To construct the pCCL4 (nucleotides −935 to +79) mutated reporter plasmid, the AP-1 motif (TGACGTCA) within the CCL4 promoter region (nucleotides −101 to −94) was replaced by GGATGTCG using site-directed mutagenesis.

Preparation of infectious lentivirus.

The methods for the production of lentiviruses were described in our previous paper (9).

Reporter assay.

HEK293T cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates and transfected with 0.625 μg CCL3 or CCL4 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid combined with 0.125 μg pSIN-LMP1 and 0.05 μg pEGFP-C1 (Promega) as a transfection control, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 72 h, the luciferase activities and green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence intensities of the cells were determined using a Bright-Glo luciferase assay system kit (Promega).

CCL4 neutralization assay.

LCLs were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/ml and treated with the doses of CCL4 neutralization antibodies indicated (BioVision, Mountain View, CA) or rabbit control Ig (Dako). After incubation for 2 days, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) was added to each well and the plate was then incubated for 18 h. Cells were harvested, and the amounts of incorporated [3H]thymidine were measured using a β counter (LS 6000 IC; Beckman).

Propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis.

Cells were fixed in 75% ethanol at −20°C overnight, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 1 ml PBS with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide, and analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Detection of EBV genome in plasma.

DNA extraction from plasma samples was performed as described previously (11). The EBV genome in plasma was quantified by detection of EBNA1 DNA using quantitative PCR. The primers were EBNA-1162F (5′-TCATCATCATCCGGGTCTCC-3′) and EBNA-1229R (5′-CCTACAGGGTGGAAAAATGGC-3′), and the probe was EBNA-1186T (5′-FAM-CGCAGG CCCCCTCCAGGTAGAA-TAMRA-3′, where FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein and TAMRA is 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine.

RESULTS

CCL3 and CCL4 are induced in EBV-infected B cells.

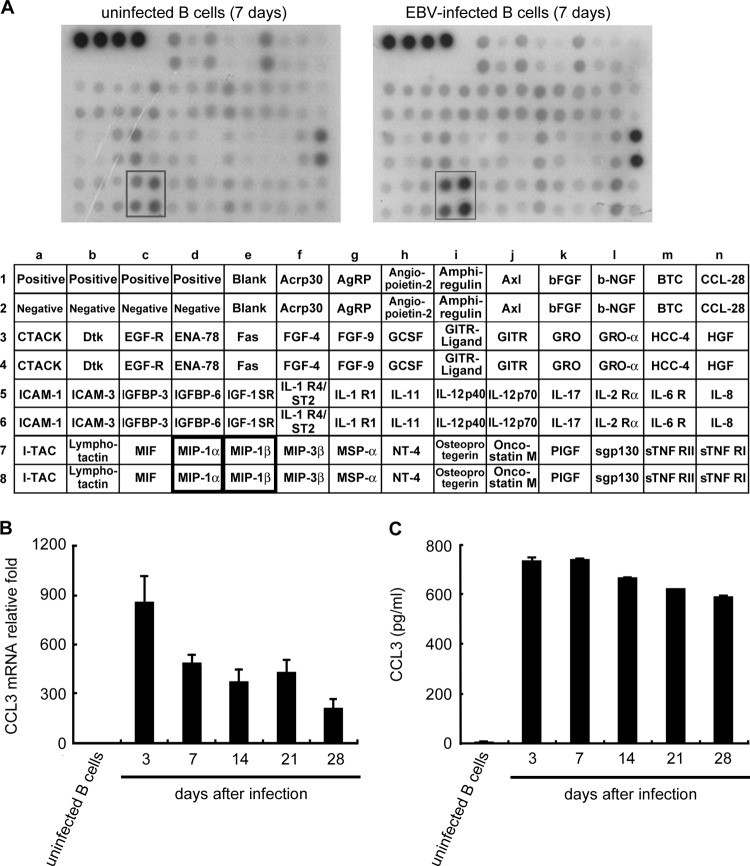

Manipulation of cellular growth factors is a strategy used by EBV to promote B cell proliferation and immortalization (1). To investigate the alteration of cytokine or chemokine expression following EBV infection, the expression profiles of EBV-infected and uninfected primary B cells were compared using antibody arrays. As shown in Fig. 1A, CCL3 and CCL4 production was clearly induced in EBV-infected B cells at day 7 postinfection. To determine the kinetics of expression of CCL3 and CCL4, EBV-infected B cells were harvested until generation of immortalized LCLs at day 28. As shown in Fig. 1B to E, CCL3 and CCL4 transcripts and proteins were rapidly induced at 3 days postinfection. Although the CCL3 and CCL4 transcripts declined slightly after 7 days of infection, large amounts of CCL3 and CCL4 accumulated in the culture medium up to day 28. To determine whether CCL3 and CCL4 are produced during the vigorous growth of LCLs, culture supernatants from various LCLs were examined. Stable production of CCL3 (range, 10.6 to 33.1 ng/ml) and CCL4 (range, 7.14 to 29.2 ng/ml) was detected in all LCLs tested; however, CCL3 and CCL4 were undetectable in uninfected primary B cells (Fig. 1F and G). These results clearly demonstrate that CCL3 and CCL4 are induced during EBV-mediated B cell immortalization and continuously expressed in LCLs.

Fig 1.

EBV infection induces CCL3 and CCL4 production. CD19-positive B cells were purified and then infected with EBV strain B95.8 or left uninfected. Supernatants of the cells were collected and subjected to cytokine array analysis at day 7 postinfection (A). At the time points indicated, the RNA and supernatants of the cells were collected to detect the amounts of CCL3 and CCL4. CCL3 (B) and CCL4 (C) mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR. The relative fold changes in CCL3 and CCL4 mRNA levels were derived by normalizing the CCL3 or CCL4 level of each sample to its GAPDH level and then standardized to that in uninfected B cells. Secreted CCL3 (D) and CCL4 (E) proteins in the culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. The CCL3 (F) and CCL4 (G) protein concentrations in the culture supernatants of 13 different LCLs were determined by ELISA. The results represent the amount of CCL3 or CCL4 (ng/ml) per 1 × 106 cells. AgRP, agouti-related protein; bEGF, basic epidermal growth factor; b-NGF, nerve growth factor b subunit; BTC, betacellulin; CTACK, cutaneous cell-attracting chemokine; EGF-R, epidermal growth factor receptor; ENA-78, neutrophil-activating protein 78; FGF-4, fibroblast growth factor 4; GCSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor; HCC-4, liver-expressed chemokine; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IGFBP-6, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6; IGF-1 SR, insulin-like growth factor 1 SR; I-TAC, interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant; MIF, migration inhibition factor; NT-4, neurotrophin 4; PIGF, placental growth factor; sTNF RII, tumor necrosis factor RII.

LMP1 plays a major role in inducing CCL3 and CCL4 expression.

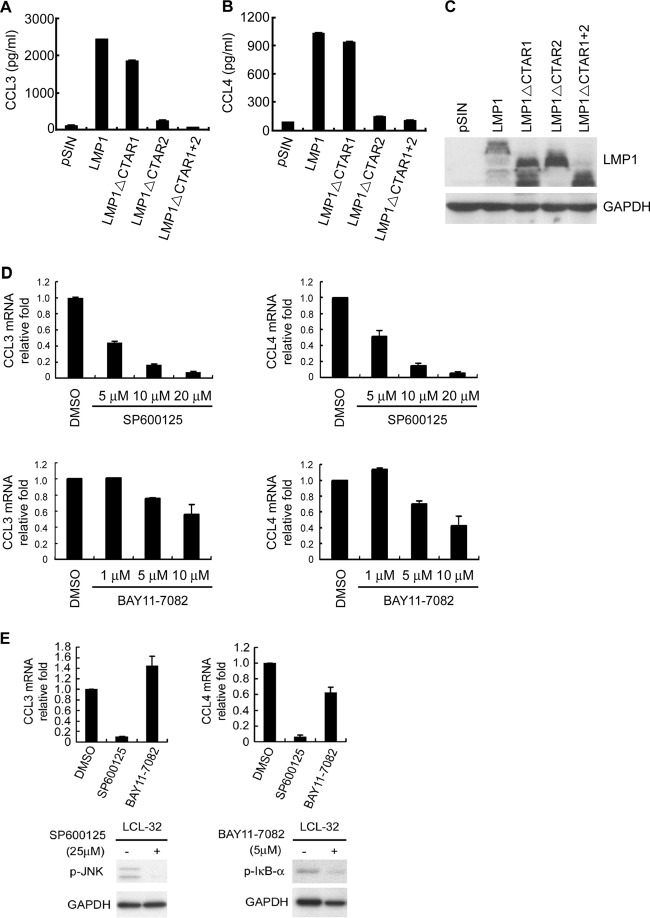

Previous studies showed that both EBV latent and lytic proteins are expressed during early infection (9). To reveal the mechanism by which EBV induces the production of CCL3 and CCL4, plasmids expressing EBV genes, including EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A, and Rta, were transfected into TW01 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. As shown in Fig. 2A to C, LMP1 greatly enhanced CCL3 and CCL4 expression at the mRNA level. We confirmed the LMP1-mediated induction of CCL3 and CCL4 in two EBV-negative Burkitt's lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma cell lines, Akata and L428. LMP1 also apparently increased CCL3 and CCL4 expression at the mRNA and protein levels in Akata and L428 cells (Fig. 2D and E). To show that LMP1 is the key regulator of CCL3 and CCL4, LMP1 was knocked down in LCLs by shRNA interference (Fig. 2F). As shown in Fig. 2G and H, the levels of CCL3 and CCL4 transcription significantly decreased in two LMP1-knockdown LCLs.

Fig 2.

EBV-encoded LMP1 mediates the induction of CCL3 and CCL4. TW01 cells were transfected with 2 μg plasmids expressing EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A, and Rta and their control vector, pSG5. After 48 h, RNA and proteins were extracted from the cells and used for RT-qPCR to quantify the amounts of the CCL3 (A) and CCL4 (B) transcripts. The relative fold changes in CCL3 and CCL4 mRNA levels were determined by normalizing the CCL3 or CCL4 level of each transfectant to its GAPDH level and then to that in vector control cells. Protein expression was confirmed for each transfectant by Western blotting (C). Akata and L428 cells were transduced with LMP1 or its vector control, pSIN, by lentivirus infection at a multiplicity of infection of 4. At 5 days postinfection, RNA and supernatants were collected (D) for detection of CCL3 and CCL4 as described above and LMP1 expression was determined (E). Two LCLs were transduced with shRNAs of LMP1 or luciferase by lentivirus infection. After 5 days, the cells were selected with 10 μg/ml puromycin for 1 week. The efficiency of LMP1 knockdown was verified by Western blotting (F), and the transcripts of CCL3 (G) and CCL4 (H) were quantified by RT-qPCR.

The CTAR2 domain of LMP1 is required for CCL3 and CCL4 induction.

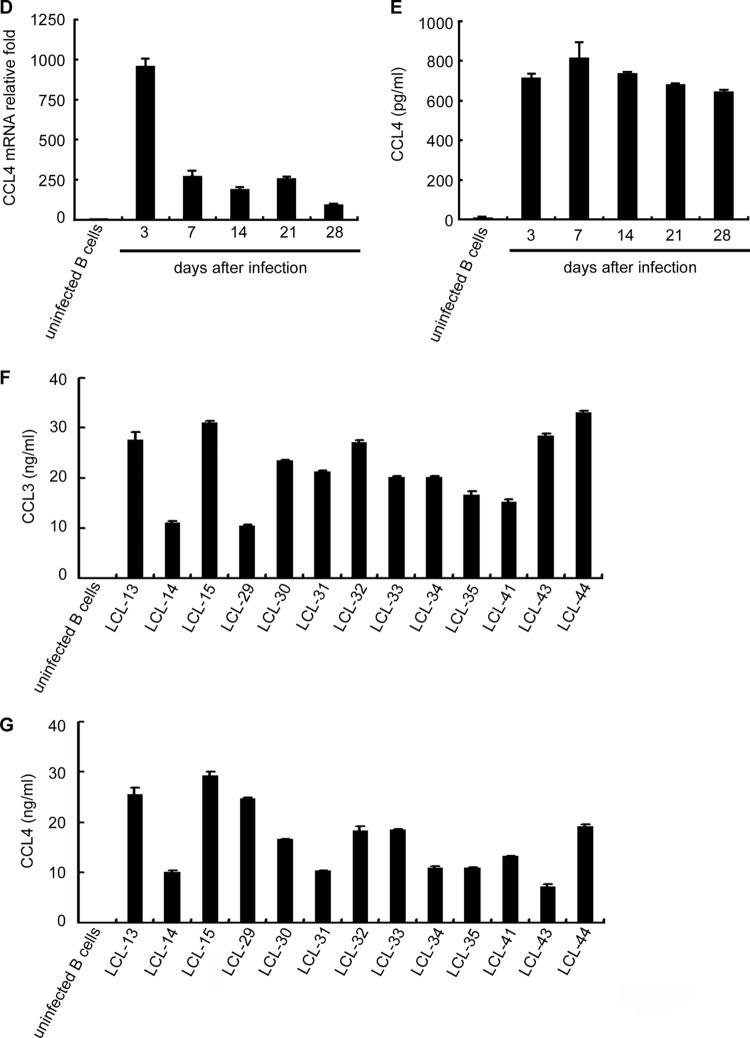

LMP1 is a transmembrane protein encoded by the EBV BNLF1 gene. It has a short N terminus, 6 transmembrane regions, and a long C terminus consisting of 3 activating domains, CTAR1, CTAR2, and CTAR3, mediating important signal transduction, such as in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase, JNK, p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, NF-κB, and JAK-STAT pathways (12, 13). To dissect the signaling pathway, we determined which region of LMP1 is crucial for CCL3 and CCL4 induction. Figures 3A to C show that deletion of the CTAR2 domain apparently abolished the ability of LMP1 to induce CCL3 and CCL4 expression. Previous studies have shown that the CTAR2 domain of LMP1 interacts with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors and the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain and constitutively activates downstream signaling molecules, including the JNK and NF-κB pathways. To explore further which LMP1-activated signaling pathways are potentially involved in the induction of CCL3 and CCL4, assays were carried out with inhibition of JNK and NF-κB. As shown in Fig. 3D, the JNK inhibitor (SP600125) but not the NF-κB inhibitor (BAY11-7082) efficiently blocked LMP1-elicited CCL3 and CCL4 expression in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, we further demonstrated that the phosphorylation of JNK and IκB-α was blocked in the presence of SP600125 and BAY11-7082 (Fig. 3E). Taken together, our data show that the EBV-encoded LMP1 is the key inducer of CCL3 and CCL4 via its CTAR2 domain and that induction is mediated through the JNK-activated pathway.

Fig 3.

LMP1-activated signaling pathways transactivate CCL3 and CCL4 promoters. Akata cells (1 × 106) were transduced with LMP1, LMP1 with a CTAR1 deletion (LMP1ΔCTAR1), LMP1 with a CTAR2 deletion (LMP1ΔCTAR2), LMP1 with both CTAR1 and CTAR2 deletions (LMP1ΔCTAR1+2), or the vector control, pSIN, by lentivirus infection at a multiplicity of infection of 4. At 5 days postinfection, supernatants from the cells were collected for detection of CCL3 (A) and CCL4 (B). (C) Expression of LMP1 protein and LMP1 deletion mutants in the cells was confirmed by Western blotting. (D and E) LCL-32 was treated with SP600125 or BAY11-7082 at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. The CCL3 and CCL4 transcripts were quantified by RT-qPCR, and the relative fold expression of CCL3 and CCL4 was normalized to the amounts of CCL3 and CCL4 transcripts in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells. The expression of phosphorylated JNK, phosphorylated IκB-α, and GAPDH was detected by Western blotting. (F to I) Schematic illustration of the CCL3 and CCL4 promoters that drive the expression of the luciferase gene in the reporter plasmids. Predicted transcription factor binding sites in the region are labeled. HEK293T cells were transfected with LMP1-expressing plasmid or the vector control in combination with pCCL3 (F) or pCCL4 (G) reporter plasmids with serial deletions at the 5′ end and pEGFP-C1 as a transfection control. After 72 h, the relative luciferase activity of each transfectant was normalized to its GFP intensity and standardized to that of the vector control cells. In addition, HEK293T transfectants were treated with SP600125 or dimethyl sulfoxide for 48 h. The relative luciferase activity of each transfectant was normalized to its GFP intensity and standardized to that of the vector control cells (H and I).

LMP1 transactivates CCL3 and CCL4 promoter activities.

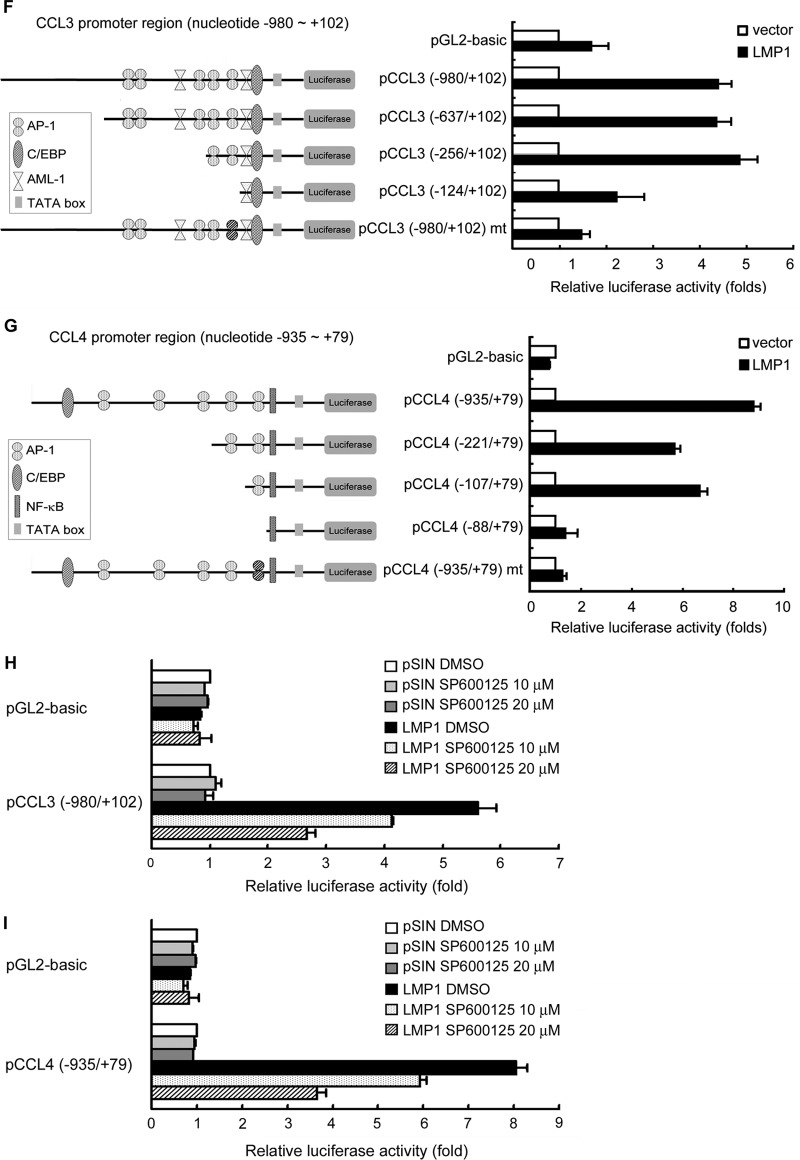

In order to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which LMP1 elicits CCL3 and CCL4 production, CCL3 and CCL4 promoter constructs in which sequence from the 5′ end was serially deleted were generated to investigate critical LMP1-responsive elements in the promoter. Putative transcription factor binding sites, AP-1, AML-1, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), and NF-κB sites, have been identified in this region on the basis of computer sequence analysis. Figure 3F (left) shows that the luciferase activity of the CCL3 promoter, spanning nucleotides −980 to +102, could be activated by about 4.5-fold by LMP1. On the basis of the relative fold activation of serial deletion constructs, the LMP1-responsive element seemed to be located at nucleotides −256 to −124, a region which contains a putative AP-1 site. Further mutation of the AP-1 site within the region from nucleotides −139 to −133 apparently diminished LMP1-induced CCL3 promoter activity, suggesting that LMP1 may transactivate CCL3 expression through the AP-1 site in the CCL3 promoter. As shown in Fig. 3G, the luciferase activity of the CCL4 promoter, spanning nucleotides −935 to +79, was induced about 9-fold by LMP1. According to the relative promoter activities of the serial deletion constructs of the CCL4 promoter, the LMP1-responsive element seemed to be located at nucleotides −107 to −88, a region which contains a predicted AP-1 motif. Further mutation of the AP-1 motif within this region completely abrogated LMP1-elicited CCL4 promoter activity. To further demonstrate whether the JNK pathway is required for LMP1 to activate promoters of CCL3 and CCL4, promoter activities were measured in the presence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125. As shown in Fig. 3H and I, the JNK inhibitor indeed suppressed LMP1-mediated CCL3 and CCL4 promoter activities. Taken together, our results indicate that the AP-1 sites in the CCL3 and CCL4 promoters are important for LMP1-mediated CCL3 and CCL4 induction.

Autocrine CCL3 mediates LCL survival and proliferation.

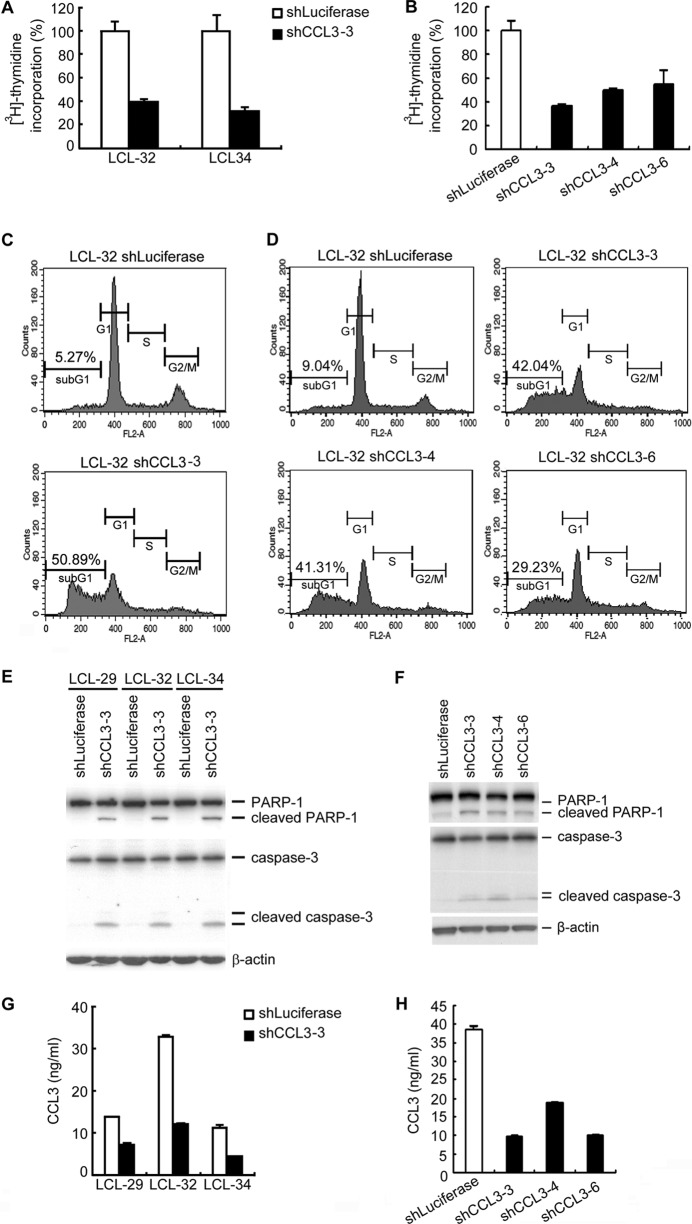

On the basis of clinical observations, autocrine CCL3 is involved in the proliferation of multiple myeloma cells (14). Therefore, we sought to determine whether CCL3 plays a role in LCL growth and survival by an shRNA approach. To exclude the possibility that shRNA was off target, three CCL3 shRNAs were included in our study. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, CCL3 could affect LCL proliferation. Furthermore, a significant increase in the sub-G1 population of CCL3-knockdown cells was observed compared to the number of cells of the shLuciferase control LCL (Fig. 4C and D). In addition, the proapoptotic molecules PARP-1 and caspase-3 were cleaved in CCL3-knockdown LCLs but not in control cells (Fig. 4E and F). Detection of CCL3 expression by ELISA indicated the knockdown efficiencies of CCL-3 shRNAs (Fig. 4G to H). These results indicate that decreased CCL3 expression results in increased apoptosis of LCL.

Fig 4.

Knockdown of CCL3 induces cell apoptosis in EBV-transformed LCLs. LCLs were infected with lentiviruses carrying luciferase or CCL3 shRNAs. (A and B) After 6 days, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added to each well and incubation was continued for 18 h. The cells were harvested, and the incorporated [3H]thymidine was quantified. (C and D) After 7 days, the cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide, followed by flow cytometric analysis. Representative data from LCL-32 are shown. (E and F) Expression of PARP-1 and caspase-3 was analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin served as the internal control. (G and H) CCL3 protein concentrations in the culture supernatants of the LCLs were determined by ELISA to confirm the efficacy of the shRNAs.

Autocrine CCL4 mediates LCL survival and proliferation.

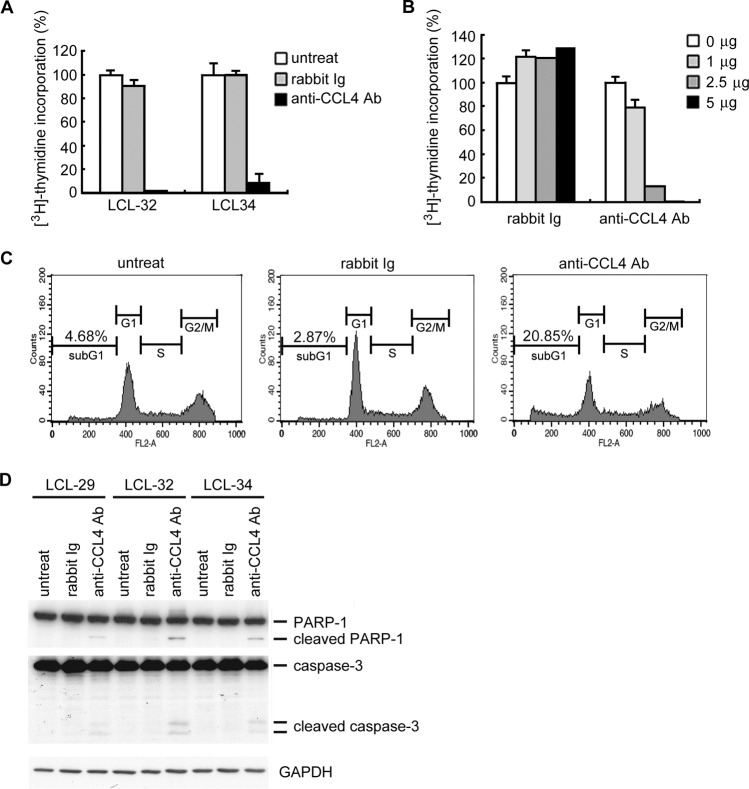

The biological effect of CCL4 in LCLs was investigated by treatment with CCL4-neutralizing antibodies. As shown in Fig. 5A, inhibition of cell proliferation was observed following treatment with CCL4-neutralizing antibodies. Compared to the rabbit Ig control, over 90% of cell proliferation was inhibited by CCL4-neutralizing antibodies in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). We also determined whether CCL4 influences cell cycle regulation. Figure 5C shows that the sub-G1 population of LCLs increased after blockade of CCL4 by neutralizing antibody, which indicates that the percentage of apoptotic cells in the total cell population increases with anti-CCL4 antibody treatment. Analysis of downstream mediators of apoptosis, the cleaved form of caspase-3 and PARP-1 (Fig. 5D), indicated that CCL4 plays an antiapoptotic role. In conclusion, our results suggest that LMP1-mediated induction of CCL3 and CCL4 protects EBV-infected B cells from apoptosis, and this may contribute to the ability of EBV to immortalize these cells.

Fig 5.

Blockade of CCL4 inhibits LCL proliferation and promotes apoptosis. LCLs were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and treated with 2.5 μg/ml of CCL4 neutralization antibody or control rabbit Ig. Two days later, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added to each well. (A) After 18 h of incubation, the cells were harvested and the incorporated [3H]thymidine was quantified. (B) LCL-34 cells were treated with the amounts of CCL4 neutralization antibody or control rabbit Ig indicated. Two days later, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added to each well. After 18 h of incubation, the cells were harvested and the incorporated [3H]thymidine was quantified. (C and D) LCLs were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and treated with 2.5 μg/ml CCL4 neutralization antibody or control rabbit Ig. After 72 h of incubation, apoptotic cells were detected by propidium iodide staining (C), and the expression of PARP-1, caspase-3, and GAPDH was visualized by Western blotting (D). untreat, untreated; Ab, antibody.

The CCL3 level is increased in the EBV-positive plasma of immunocompromised patients.

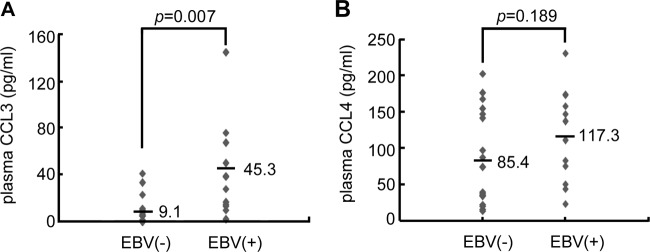

Organ transplant recipients may develop PTLD involving EBV-infected B cells, and the EBV load is of concern regarding this complication (15). Therefore, we examined the correlation between the plasma EBV load and the protein levels of CCL3 and CCL4 in immunosuppressed and immunocompromised patients. Tables 1 and 2 list the clinical characteristics and plasma CCL3 and CCL4 levels of organ transplant recipients and other patients with EBV-related hemophagocytotic syndrome and EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorder. These patients were divided into EBV-negative and EBV-positive groups according to whether the EBV genome was detected in their plasma. The average CCL3 levels in EBV-negative (n = 18) and EBV-positive (n = 12) plasma were 9.1 and 45.3 pg/ml, respectively. EBV-positive individuals had significantly higher concentrations of CCL3 than the EBV-negative group (P = 0.007; Fig. 6A). In addition, we also measured plasma CCL3 concentrations in healthy individuals, and these ranged from 0 to 10 pg/ml (data not shown), suggesting that EBV conceivably upregulates the expression of CCL3 in vivo. However, the CCL4 concentrations did not differ significantly between EBV-negative and EBV-positive plasma (85.4 versus 117.3 pg/ml; P = 0.189; Fig. 6B). Measurement of plasma CCL4 concentrations in the healthy individuals showed considerable variation, with the concentrations ranging from 15 to 210 pg/ml, with an average of 100.1 pg/ml (data not shown), indicating that EBV may not be the only factor influencing CCL4 expression in vivo.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and plasma CCL3 and CCL4 concentrations in EBV-negative immunocompromised patients

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/gendera | Diagnosis | Concn (pg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL3 | CCL4 | |||

| 1 | 5/M | Hemophagocytotic syndrome | 5.0 | 21.8 |

| 2 | 15/M | Bone marrow transplantation | 5.0 | 39.3 |

| 3 | 3/F | Liver transplantation | 10.0 | 19.3 |

| 4 | 4/F | Liver transplantation | 5.0 | 35.3 |

| 5 | 9/F | Liver transplantation | 0.0 | 74.4 |

| 6 | 4/F | Liver transplantation | 0.0 | 175.9 |

| 7 | 11/F | Liver transplantation | 0.0 | 33.7 |

| 8 | 8/M | Bone marrow transplantation | 0.0 | 168.0 |

| 9 | 4/M | Liver transplantation | 33.3 | 202.5 |

| 10 | 4/F | Liver transplantation | 11.6 | 147.5 |

| 11 | 13/F | Bone marrow transplantation | 8.3 | 73.8 |

| 12 | 8/M | Bone marrow transplantation | 6.6 | 141.3 |

| 13 | 11/F | Liver transplantation | 1.6 | 15.0 |

| 14 | 6/F | Liver transplantation | 0.0 | 13.8 |

| 15 | 4/F | Bone marrow transplantation | 8.3 | 96.9 |

| 16 | 9/F | Liver transplantation | 5.0 | 36.9 |

| 17 | 7/M | Liver transplantation | 23.3 | 87.5 |

| 18 | 1/F | Liver transplantation | 41.1 | 154.4 |

| Avg | 9.1 | 85.4 | ||

M, male; F, female.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and plasma CCL3 and CCL4 concentrations in EBV-positive immunocompromised patients

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/gendera | Diagnosis | Concn (pg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL3 | CCL4 | |||

| 1 | 5/M | Hemophagocytotic syndrome | 50.0 | 136.8 |

| 2 | 15/M | Bone marrow transplantation | 16.6 | 43.8 |

| 3 | 3/F | Liver transplantation | 39.4 | 158.1 |

| 4 | 4/F | Liver transplantation | 10.0 | 75.5 |

| 5 | 5/F | Liver transplantation | 67.5 | 50.5 |

| 6 | 19/M | Bone marrow transplantation | 144.6 | 230.9 |

| 7 | 15/M | Lymphoproliferative disorder | 38.6 | 147.3 |

| 8 | 18/F | Liver transplantation | 28.3 | 23.1 |

| 9 | 9/F | Bone marrow transplantation | 13.3 | 83.1 |

| 10 | 6/M | Liver transplantation | 15.0 | 174.4 |

| 11 | 5/F | Liver transplantation | 76.1 | 173.1 |

| 12 | 10/M | Lymphoproliferative disorder | 44.6 | 110.9 |

| Avg | 45.3 | 117.3 | ||

M, male; F, female.

Fig 6.

CCL3 levels are elevated in EBV-positive plasma from organ transplantation patients. Plasma samples were collected from patients posttransplantation. After detection of the EBV genome, the samples were divided into two groups, EBV negative (n = 18) and EBV positive (n = 12). CCL3 (A) and CCL4 (B) protein concentrations were quantified in the patients' plasma samples by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

The molecular mechanisms of cell immortalization by EBV remain largely unclear, although several lines of evidence indicate that the induction of cellular factors and maintenance of telomeres are the key factors of immortalization (16, 17). Recently, autocrine and paracrine loops of chemokines and chemokine receptors have been shown to govern the tumor microenvironment, contributing to cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and immunosuppressive responses (18). Many oncogenic viruses hijack chemokine systems to manipulate the proliferation of infected cells (19). For example, KSHV-encoded homologs of CCL1, CCL2, and CCL3 (3) and an ORF74 chemokine receptor are involved in the tumorigenesis of KSHV-associated malignancies, such as Kaposi's sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma (20). In addition, the induction of a CCL12 and CXCR4 autocrine loop by human papillomavirus is required for transformation of infected keratinocytes (21). In this study, we report that CCL3 production is dramatically induced in the plasma of EBV-positive organ transplantation patients (Fig. 6A). Thus, chemokine expression induced by EBV infection may play various roles in the progression of EBV-associated malignancies.

Overexpression of CCL3 and CCL4 has been observed in B cell-related tumors, including multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)(14, 22). Functionally, CCL3 can directly trigger survival and proliferation signaling in multiple myeloma by acting as an autocrine survival and growth factor (14). In addition, high levels of CCL3 and CCL4 are induced in CLL following B cell receptor stimulation. Both chemokines may sustain CLL cell survival (23). The biological functions of CCL3 and CCL4 in EBV-infected B cells have been investigated only to a limited extent; despite that, EBV infection is associated with many human B lymphomas. In this study, blockade of CCL3 and CCL4 expression by EBV-transformed LCLs suppressed cell survival and growth (Fig. 4 and 5). Thus, CCL3 and CCL4 serve as survival and growth factors in B cells. In addition, patients carrying high copy numbers of EBV have significantly higher levels of CCR5, a binding receptor of CCL3 and CCL4 (24). In our study, we found that CCR5 is highly expressed during primary infection and constitutive expression is maintained in EBV-immortalized LCLs (data not shown). On the other hand, patients with a CCR5 gene deletion have a nonfunctional CCR5 chemokine receptor, leading to a low EBV load in sera after transplantation (24).

On the basis of our study and previous studies, most chemokines upregulated in EBV-infected cells, including CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL17, and CCL22, are induced by EBV LMP1 (7, 25). Functionally, LMP1 mimics constitutively activated CD40, which provides proliferating and antiapoptosis signaling in B cells. Acting as a critical EBV oncogenic membrane protein without enzyme activity, LMP1 uses diverse strategies to influence host gene expression. These genes, detailed below, are involved in the control of cell differentiation, survival, proliferation, and cell mobility. (i) LMP1 can upregulate tyrosine kinases, such as recepteur d'origine nantais (RON) and epidermal growth factor receptor, which are important for cell growth and migration (10, 26). (ii) The synthesis and secretion of IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 can be enhanced by LMP1, and these then act in an autocrine manner to promote cell proliferation and affect the host immune response (27–29). (iii) LMP1 can stimulate the antiapoptotic genes A20, BCL-2, and survivin to prevent infected cells from apoptosis (30–32). (iv) LMP1 can facilitate the degradation of p53 by augmenting the expression of mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (33, 34). (v) LMP1 can promote cell motility and invasion by upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP1) and MMP9 (35, 36). (vi) LMP1 upregulates the expression of DNA methyltransferase, Twist, and Snail, which then prevents the expression of E-cadherin and promotes the formation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (37–40). Mechanistically, LMP1 influences host gene expression via interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (2). According to documented reports, CTAR1 and CTAR2 have the potential to trigger JNK and NF-κB signaling. From our data, it seems that the CTAR2 motif of LMP1 is the key contributor to CCL3 and CCL4 induction (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, we have shown that LMP1-mediated JNK activation promotes CCL3 and CCL4 gene expression (Fig. 3D). In addition, we showed that AP-1 binding proteins are important for LMP1-induced CCL3 and CCL4 expression, in addition to the well-known role of NF-κB.

Several mouse models have demonstrated that LMP1 is the key EBV product involved in tumor formation. LMP1 transgenic mice over 12 months old have a 40% to 50% incidence of spontaneous B cell lymphoma (41). Furthermore, B cells expressing transgenic LMP1 undergo rapid lymphoproliferation and lymphomagenesis in T cell-deficient mice (42). These results indicate that LMP1 is a key transforming viral protein involved in regulating the cell cycle, survival, and growth of EBV-infected B cells.

To regulate chemokine expression, many viruses also encode G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) which mimic cellular chemokine receptors functionally to influence chemokine expression (43, 44). So far, a broad spectrum of viral GPCRs has been shown to be encoded by human DNA viruses, such as EBV, KSHV HCMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7 (45). The EBV-encoded GPCR BILF1 is a lytic gene and serves as a constitutively activated receptor through the Gi protein (46). EBV BILF1 plays a role in immune evasion during lytic cycle progression by downregulation of surface major histocompatibility complex class I molecule expression (47) and inhibition of CXCR4 signaling by heterodimerization with that protein (46).

Overall, we have shown that EBV LMP1 can upregulate CCL3 and CCL4, which is required for prevention of apoptosis and for cell proliferation. Finally, we are the first to report that EBV-positive transplantation patients have significantly increased CCL3 concentrations in their plasma compared to the concentrations in EBV-negative patients. Thus, our results indicate that CCL3 may be involved in regulating EBV reactivation in patients posttransplantation and that CCL3 may be a good target for the diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis of PTLD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tim J. Harrison of the UCL Medical School, London, United Kingdom, for critically reviewing the manuscript.

We declare no competing financial interests.

This work was supported by the National Science Council (NSC-100-2320-B-002-100-MY3 to C.-H.T.; NSC-98-2320-B-182-038-MY3 and NSC-101-2325-B-182-002 to S.-J.L.) and the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-EX102-10031BI to C.-H.T.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Thorley-Lawson DA, Allday MJ. 2008. The curious case of the tumour virus: 50 years of Burkitt's lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:913–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dawson CW, Port RJ, Young LS. 2012. The role of the EBV-encoded latent membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Semin. Cancer Biol. 22:144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin D, Gutkind JS. 2008. Human tumor-associated viruses and new insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer. Oncogene 27(Suppl 2):S31–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jabs WJ, Wagner HJ, Maurmann S, Hennig H, Kreft B. 2002. Inhibition of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α production by Epstein-Barr virus. Blood 99:1512–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaudreault E, Fiola S, Olivier M, Gosselin J. 2007. Epstein-barr virus induces MCP-1 secretion by human monocytes via TLR2. J. Virol. 81:8016–8024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ehlin-Henriksson B, Liang W, Cagigi A, Mowafi F, Klein G, Nilsson A. 2009. Changes in chemokines and chemokine receptor expression on tonsillar B cells upon Epstein-Barr virus infection. Immunology 127:549–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakayama T, Hieshima K, Nagakubo D, Sato E, Nakayama M, Kawa K, Yoshie O. 2004. Selective induction of Th2-attracting chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 in human B Cells by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 78:1665–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miyauchi K, Urano E, Yoshiyama H, Komano J. 2011. Cytokine signatures of transformed B cells with distinct Epstein-Barr virus latencies as a potential diagnostic tool for B cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 102:1236–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsai SC, Lin SJ, Chen PW, Luo WY, Yeh TH, Wang HW, Chen CJ, Tsai CH. 2009. EBV Zta protein induces the expression of interleukin-13, promoting the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines. Blood 114:109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chou YC, Lin SJ, Lu J, Yeh TH, Chen CL, Weng PL, Lin JH, Yao M, Tsai CH. 2011. Requirement for LMP1-induced RON receptor tyrosine kinase in Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation. Blood 118:1340–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lo YM, Chan LY, Lo KW, Leung SF, Zhang J, Chan AT, Lee JC, Hjelm NM, Johnson PJ, Huang DP. 1999. Quantitative analysis of cell-free Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 59:1188–1191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shair KHY, Bendt KM, Edwards RH, Bedford EC, Nielsen JN, Raab-Traub N. 2007. EBV latent membrane protein 1 activates Akt, NFκB, and Stat3 in B cell lymphomas. PLoS Pathog. 3:e166. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morris MA, Dawson CW, Young LS. 2009. Role of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein-1, LMP1, in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Future Oncol. 5:811–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lentzsch S, Gries M, Janz M, Bargou R, Dorken B, Mapara MY. 2003. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1 alpha) triggers migration and signaling cascades mediating survival and proliferation in multiple myeloma (MM) cells. Blood 101:3568–3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuppers R. 2003. B cells under influence: transformation of B cells by Epstein-Barr virus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:801–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Counter CM, Botelho FM, Wang P, Harley CB, Bacchetti S. 1994. Stabilization of short telomeres and telomerase activity accompany immortalization of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed human B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 68:3410–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sugimoto M, Tahara H, Ide T, Furuichi Y. 2004. Steps involved in immortalization and tumorigenesis in human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines transformed by Epstein-Barr virus. Cancer Res. 64:3361–3364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. 2007. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:79–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Damania B. 2004. Oncogenic gamma-herpesviruses: comparison of viral proteins involved in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:656–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holst PJ, Rosenkilde MM, Manfra D, Chen S-C, Wiekowski MT, Holst B, Cifire F, Lipp M, Schwartz TW, Lira SA. 2001. Tumorigenesis induced by the HHV8-encoded chemokine receptor requires ligand modulation of high constitutive activity. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1789–1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chow KYC, Brotin M, Ben Khalifa Y, Carthagena L, Teissier S, Danckaert A, Galzi J-L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Thierry F, Bachelerie F. 2010. A pivotal role for CXCL12 signaling in HPV-mediated transformation of keratinocytes: clues to understanding HPV-pathogenesis in WHIM syndrome. Cell Host Microbe 8:523–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burger JA, Quiroga MP, Hartmann E, Burkle A, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Rosenwald A. 2009. High-level expression of the T-cell chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 by chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells in nurselike cell cocultures and after BCR stimulation. Blood 113:3050–3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zucchetto A, Benedetti D, Tripodo C, Bomben R, Dal Bo M, Marconi D, Bossi F, Lorenzon D, Degan M, Rossi FM, Rossi D, Bulian P, Franco V, Del Poeta G, Deaglio S, Gaidano G, Tedesco F, Malavasi F, Gattei V. 2009. CD38/CD31, the CCL3 and CCL4 chemokines, and CD49d/vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 are interchained by sequential events sustaining chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell survival. Cancer Res. 69:4001–4009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bogunia-Kubik K, Jaskula E, Lange A. 2007. The presence of functional CCR5 and EBV reactivation after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 40:145–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lai HC, Hsiao JR, Chen CW, Wu SY, Lee CH, Su IJ, Takada K, Chang Y. 2010. Endogenous latent membrane protein 1 in Epstein-Barr virus-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells attracts T lymphocytes through upregulation of multiple chemokines. Virology 405:464–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kung CP, Raab-Traub N. 2008. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor through effects on Bcl-3 and STAT3. J. Virol. 82:5486–5493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang YT, Liu MY, Tsai CH, Yeh TH. 2010. Upregulation of interleukin-1 by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 and its possible role in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth. Head Neck 32:869–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eliopoulos AG, Stack M, Dawson CW, Kaye KM, Hodgkin L, Sihota S, Rowe M, Young LS. 1997. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1 and CD40 mediate IL-6 production in epithelial cells via an NF-kappaB pathway involving TNF receptor-associated factors. Oncogene 14:2899–2916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lambert SL, Martinez OM. 2007. Latent membrane protein 1 of EBV activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to induce production of IL-10. J. Immunol. 179:8225–8234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fries KL, Miller WE, Raab-Traub N. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 blocks p53-mediated apoptosis through the induction of the A20 gene. J. Virol. 70:8653–8659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rowe M, Peng-Pilon M, Huen DS, Hardy R, Croom-Carter D, Lundgren E, Rickinson AB. 1994. Upregulation of bcl-2 by the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein LMP1: a B-cell-specific response that is delayed relative to NF-kappa B activation and to induction of cell surface markers. J. Virol. 68:5602–5612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guo L, Tang M, Yang L, Xiao L, Bode AM, Li L, Dong Z, Cao Y. 2012. Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein LMP1 mediates survivin upregulation by p53 contributing to G1/S cell cycle progression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 29:574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu HC, Lu TY, Lee JJ, Hwang JK, Lin YJ, Wang CK, Lin CT. 2004. MDM2 expression in EBV-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Lab. Invest. 84:1547–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li L, Guo L, Tao Y, Zhou S, Wang Z, Luo W, Hu D, Li Z, Xiao L, Tang M, Yi W, Tsao SW, Cao Y. 2007. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus regulates p53 phosphorylation through MAP kinases. Cancer Lett. 255:219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lu J, Chua HH, Chen SY, Chen JY, Tsai CH. 2003. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-1 by Epstein-Barr virus proteins. Cancer Res. 63:256–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshizaki T, Sato H, Furukawa M, Pagano JS. 1998. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 is enhanced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3621–3626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsai CN, Tsai CL, Tse KP, Chang HY, Chang YS. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus oncogene product, latent membrane protein 1, induces the downregulation of E-cadherin gene expression via activation of DNA methyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:10084–10089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Horikawa T, Yang J, Kondo S, Yoshizaki T, Joab I, Furukawa M, Pagano JS. 2007. Twist and epithelial-mesenchymal transition are induced by the EBV oncoprotein latent membrane protein 1 and are associated with metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 67:1970–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fahraeus R, Chen W, Trivedi P, Klein G, Obrink B. 1992. Decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased invasive capacity in EBV-LMP-transfected human epithelial and murine adenocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 52:834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horikawa T, Yoshizaki T, Kondo S, Furukawa M, Kaizaki Y, Pagano JS. 2011. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces Snail and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 104:1160–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kulwichit W, Edwards RH, Davenport EM, Baskar JF, Godfrey V, Raab-Traub N. 1998. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces B cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:11963–11968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang B, Kracker S, Yasuda T, Casola S, Vanneman M, Hömig-Hölzel C, Wang Z, Derudder E, Li S, Chakraborty T, Cotter SE, Koyama S, Currie T, Freeman GJ, Kutok JL, Rodig SJ, Dranoff G, Rajewsky K. 2012. Immune surveillance and therapy of lymphomas driven by Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP1 in a mouse model. Cell 148:739–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sodhi A, Montaner S, Gutkind JS. 2004. Viral hijacking of G-protein-coupled-receptor signalling networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:998–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alcami A. 2003. Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:36–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nicholas J. 2005. Human gammaherpesvirus cytokines and chemokine receptors. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nijmeijer S, Leurs R, Smit MJ, Vischer HF. 2010. The Epstein-Barr virus-encoded G protein-Coupled Receptor BILF1 hetero-oligomerizes with human CXCR4, scavenges G alpha i proteins, and constitutively impairs CXCR4 functioning. J. Biol. Chem. 285:29632–29641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zuo J, Currin A, Griffin BD, Shannon-Lowe C, Thomas WA, Ressing ME, Wiertz EJ, Rowe M. 2009. The Epstein-Barr virus G-protein-coupled receptor contributes to immune evasion by targeting MHC class I molecules for degradation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000255. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]