Abstract

BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) is a widespread human pathogen that establishes a lifelong persistent infection and can cause severe disease in immunosuppressed patients. BKPyV is a nonenveloped DNA virus that must traffic through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for productive infection to occur; however, it is unknown how BKPyV exits the ER before nuclear entry. In this study, we elucidated the role of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway during BKPyV intracellular trafficking in renal proximal tubule epithelial (RPTE) cells, a natural host cell. Using proteasome and ERAD inhibitors, we showed that ERAD is required for productive entry. Altered trafficking and accumulation of uncoated viral intermediates were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization and indirect immunofluorescence in the presence of an inhibitor. Additionally, we detected a change in localization of partially uncoated virus within the ER during proteasome inhibition, from a BiP-rich area to a calnexin-rich subregion, indicating that BKPyV accumulated in an ER subcompartment. Furthermore, inhibiting ERAD did not prevent entry of capsid protein VP1 into the cytosol from the ER. By comparing the cytosolic entry of the related polyomavirus simian virus 40 (SV40), we found that dependence on the ERAD pathway for cytosolic entry varied between the polyomaviruses and between different cell types, namely, immortalized CV-1 cells and primary RPTE cells.

INTRODUCTION

BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) is a human pathogen that is ubiquitous throughout the population. Studies show that up to 90% of adults are seropositive for BKPyV, which is believed to infect individuals during early childhood and establish a persistent subclinical infection for the lifetime of the host (1). While BKPyV does not usually cause disease in healthy individuals, it can lead to severe disease in immunocompromised patients, particularly in bone marrow and kidney transplant patients. Under conditions of immunosuppression, reactivation of BKPyV in the bladder or kidney causes hemorrhagic cystitis or polyomavirus-associated nephropathy (PVAN), respectively. There are currently no effective antivirals against BKPyV, and the current treatment protocol is palliative or, in renal transplant patients, reduction of immunosuppressive therapy, leaving the patient vulnerable to graft rejection. Graft loss occurs in up to 50% of cases of PVAN (2), due to either the virus or rejection. Before useful antiviral drugs can be developed, a deeper understanding of the BKPyV life cycle is necessary, including the details of intracellular entry. These early interactions between BKPyV and the host cell have yet to be fully elucidated.

In the interest of studying BKPyV in a relevant biological setting, our laboratory previously established a cell culture model of BKPyV infection using primary renal proximal tubule epithelial (RPTE) cells (3). This is based on the observation of histologic sections and transmission electron micrographs of PVAN patient biopsy specimens, indicating lytic infection by BKPyV in RPTE cells (4–6). We have shown that the intracellular trafficking pathway of BKPyV in RPTE cells begins with binding to the ganglioside receptors GT1b and GD1b, followed by internalization and a pH-dependent step within the first 2 h after adsorption. The virus subsequently relies on microtubules (7–9) and traffics through the endocytic pathway to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it arrives approximately 8 h postinfection (hpi) (9). Sometime after ER trafficking but before 24 hpi, the virus enters the nucleus, where transcription of early regulatory genes occurs, followed by DNA replication and late gene expression. It is unknown, however, how BKPyV gets from the ER to the nucleus. Two possible routes have been proposed: the virus can cross the inner nuclear membrane directly from the ER lumen, or the virus can cross the ER membrane into the cytosol, from where it can subsequently enter the nucleus, likely via the nuclear pore complex.

In order for the BKPyV genome to undergo replication and transcription in the nucleus, it must be uncoated and released from the viral capsid. The BKPyV capsid structure consists of three proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3. The major capsid protein, VP1, oligomerizes into pentamers during virion production and makes up the outer shell of the particle, with 72 pentamers stabilized by inter- and intra-disulfide bonds (10). It is believed that these disulfide bonds become reduced and/or isomerized by host disulfide reductases and isomerases when the virus infects a naive cell and traffics through the ER (9, 11). One molecule of either minor capsid protein, VP2 or VP3, is associated with each pentamer and is concealed by VP1 from antibody detection until disassembly begins in the ER (12, 13).

Evidence from previous studies has implicated a role for components of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway during infection with polyomaviruses (14–17). ER quality control (ERQC) mechanisms of the cell include the ERAD pathway as a means by which secretory proteins in the ER that cannot attain their proper conformation are sent into the cytosol and degraded by the proteasome (18). The feature of ERAD that makes it an enticing host pathway for a nonenveloped virus to co-opt is that it provides a mechanism for ER-localized proteins—in this case the viral particle—to be sent across the ER membrane into the cytosol. ERAD depends on an intricate collection of chaperones and transmembrane proteins that recognize a misfolded protein, target and shuttle the protein to a retrotranslocation complex, translocate the substrate across the ER membrane into the cytosol (where it is ubiquitinated), and send it to the proteasome for degradation (18). One set of ERAD translocation complex proteins, the Derlin family, has been found to be necessary for mouse polyomavirus, simian virus 40 (SV40), and BKPyV, through experiments with small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdowns or dominant negative constructs (9, 14, 17). Proteasome function has also been shown to be necessary for both SV40 and BKPyV infections (9, 14), and treatment with the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin resulted in an increase in disassembly products of the BKPyV capsid (9), suggesting that blocking proteasome function may alter the disassembly and entry pathway of BKPyV.

It was the goal of this study to further investigate the entry route of BKPyV during and after ER trafficking, focusing on the role of the ERAD pathway and the proteasome. This is the first study to examine polyomavirus ER-to-cytosol trafficking in the context of a natural host cell. We show that the proteasome and ERAD system do play a role in the trafficking of BKPyV, as specific inhibitors block an early step during infection. We also show that proteasome inhibition causes a change in the ER localization of BKPyV and an accumulation of detectable VP2/3 protein, indicating disassembled particles in the ER. Additionally, we provide evidence that BKPyV enters the cytosol. Interestingly, however, we show that proteasome and ERAD inhibitors do not prevent BKPyV VP1 protein from entering the cytosol. Moreover, our data suggest that differences exist in the trafficking of polyomaviruses in different cell types, as seen with both BKPyV and SV40 in RPTE cells compared to CV-1 cells. Altogether, this report provides new evidence that the ERAD pathway is involved during BKPyV entry and that there are important differences in the trafficking and entry of polyomaviruses in different cell types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

RPTE cells were grown in renal epithelial basal growth medium (REGM) with SingleQuots Bulletkit from Lonza at 37°C and 5% CO2 and passaged up to six times as previously described (19). The CV-1 cell line (African green monkey kidney cells; ATCC) was grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Cambrex).

Transfections.

The CD3δ-yellow fluorescent protein (CD3δ-YFP) plasmid was obtained from Addgene, Cambridge, MA (plasmid 11951) (20). Transfection complexes were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions, using TransIT-LT-1 (Mirus) reagent at a 1:6 ratio of DNA to the transfection reagent. Cells were seeded on glass coverslips in a 12-well plate and transfected with 0.5 μg plasmid per well at approximately 70 to 80% confluence. Medium was changed 12 h posttransfection, and infections were initiated at 24 h posttransfection.

Infections.

Purified BKPyV (TU variant) was propagated and purified as previously described (19). SV40 was a gift from Billy Tsai (University of Michigan). The viral titer was measured by fluorescence focus assay as previously described (9). Infections were performed when RPTE cells or CV-1 cells were approximately 70 to 80% confluent. Cells were first prechilled for 15 min at 4°C. Purified virus was mixed with cold REGM or serum-free DMEM for RPTE cells or CV-1 cells, respectively, and virus was bound for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were washed once with cold medium and then switched to warmed serum-containing medium and incubated at 37°C for the desired time. For ganglioside receptor pretreatment, cells were incubated 24 h before infection with either GM1 or GT1b and then washed 3 times with medium. Biotinylated BKPyV was prepared by incubating virus particles with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Drug treatments.

Epoxomicin (Sigma, Enzo Lifesciences) and Eeyarestatin I (Santa Cruz Biotech) were each dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used at 10 μM. Brefeldin A (BFA; Sigma) was dissolved in ethanol and used at 1.25 μg/ml. A WST metabolic assay (Roche) was used to ensure that drug treatments did not cause significant cytotoxicity under the conditions used. Ganglioside GM1 or GT1b (Santa Cruz Biotech) was reconstituted in water and used at 3.2 μM.

Preparation of cell lysates.

Whole-cell protein lysates were harvested in E1A buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7], 250 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40, with protease inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF; 5 μg/ml], aprotinin [5 μg/ml], Naf [50 mM], sodium orthovanadate [0.2 mM], and leupeptin [5 μg/ml] added right before use). Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay. For cytosolic fractionation, a 100-mm plate or 2 wells (of a 6-well plate) of cells were infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 infectious units (IU) per cell with BKPyV or SV40. Cells were harvested at 16 hpi for BKPyV and 12 hpi for SV40 by treatment with 0.25% trypsin for approximately 1 min or until cells detached from the plate. Trypsin was inhibited with an equal volume of 1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, and cells were collected in 4 ml cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were pelleted at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C and then resuspended in 1 ml 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (Sigma) in PBS for 45 min on ice. After alkylation, cells were again pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl 0.01% digitonin (for RPTE cells) or 0.05% digitonin (for CV-1 cells) in HCN buffer (150 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 20 mM NEM, and protease inhibitors PMSF [5 μg/ml], aprotinin [5 μg/ml], NaF [50 mM], sodium orthovanadate [0.2 mM], and leupeptin [5 μg/ml] added right before use) for 10 min on ice. The cytosolic fraction was separated from the pellet fraction by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant (cytosolic) fraction was removed, and the pellet was washed with 500 μl 1× PBS. The pellet fraction was solubilized by resuspension in 100 μl E1A lysis buffer and then clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min. To isolate either BKPyV or SV40 genomic DNA from cytosol-enriched supernatant fractions, equal amounts of lysate based on protein concentration (150 ng) from each sample were treated with 5 μg proteinase K (Qiagen) for 1 h at 37°C. DNA was then isolated from the samples with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen).

Western bloting.

Equal amounts of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE (8% for T antigen [TAg] and 10% for all other proteins) under reducing or nonreducing conditions and transferred overnight onto a nitrocellulose membrane at 60 V by wet transfer. Membranes were blocked in 2% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T). Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 2% milk in PBS-T as follows: TAg was detected with mouse monoclonal antibody pAb416 (21) at 1:1,000; BKPyV VP1 was detected by mouse monoclonal antibody P5G6 at 1:5,000; ER proteins were detected by mouse anti-BiP (BD Biosciences) at 1:1,000 and rabbit anti-PDI (Enzo) at 1:2,000; SV40 VP1 was detected by mouse monoclonal anti-VP1 (a gift from Billy Tsai; originally from W. Scott) at 1:2,000; rabbit anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling) was used at 1:10,000, and mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; Abcam) was used at 1:5,000; horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated ECL anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (GE) were used at 1:2,000 to 1:5,000; and streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (GE) was used at 1:1,000.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

RPTE cells were grown on coverslips, infected as described above, and fixed at 24 hpi using cold 95% EtOH–5% acetic acid. Coverslips were treated with RNase for 1 h at 37°C to avoid any RNA background staining. Coverslips were then prehybridized by incubation in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 4% SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]) for at least 30 min at 37°C. The fluorescently labeled DNA probe against the viral genome was prepared using a nick translation kit (GE) with Cy3-dCTP and pBR322 plasmid containing the TU BKPyV genome. Unincorporated nucleotides were filtered using a Bio-Rad Quickspin column. The hybridization step was performed by first diluting the probe in hybridization buffer, denaturing the probe and coverslips at 95°C for 2 min, and immediately incubating the denatured coverslips with the denatured probe overnight at 37°C in a humidified chamber. The next day, the coverslips were washed once with 2× SSC at 60°C, once with 2× SSC at room temperature, and once with 1× PBS at room temperature. Coverslips were then costained for indirect immunofluorescence or mounted on slides using Prolong Gold Antifade with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

At the desired time postinfection, cells were fixed and permeabilized with 95% ethanol–5% acetic acid. Coverslips were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS and then probed with primary antibody diluted in 5% goat serum. Antibodies used were mouse anticalnexin (BD Biosciences) at 1:40, mouse anti-BiP (Santa Cruz) at 1:200, and mouse anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP) at 1:100 (Santa Cruz). Anti-VP2/3 was raised by Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., against the peptide sequence CKTGRASAKTTNKRRSRSSRS and obtained as affinity-purified antibodies after processing from hyperimmune sera from immunized rabbits. Secondary antibody Alexa-Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) was used at a 1:200 dilution. Coverslips were mounted onto slides using Prolong Gold Antifade with DAPI (Invitrogen). Imaging was done on a Zeiss LSM 510-META laser scanning confocal microscope using a C-Apochromat 63× objective and 1.0-μm optical section at the University of Michigan Microscopy and Imaging Analysis Laboratory.

qPCR.

Before quantitative PCR (qPCR), samples were diluted 100-fold. Primers used to quantify BKPyV were 5′-TGTGATTGGGATTCAGTGCT-3′ and 5′-AAGGAAAGGCTGGATTCTGA-3′, and primers used to quantify SV40 were 5′-AAGCAAAGCAATGCCACTTT-3′ and 5′-CACTGCAGGCCAGATTTGTA-3′ (Invitrogen). Both pairs amplify a region of the TAg open reading frame.

RESULTS

Productive infection requires the proteasome and ERAD pathway.

Because previous studies indicated that the proteasome may play a role during entry of BKPyV (9, 14), we became interested in further clarifying the function of the proteasome and whether the ERAD pathway is involved during infection. To examine whether the proteasome was involved in an early step during infection coincident with transit through the ER, a time course of drug treatment was performed to determine when infection would no longer be sensitive to proteasome inhibition. We used epoxomicin, which is a potent inhibitor of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome and also blocks the trypsin-like and peptidyl-glutamyl peptide hydrolyzing activities (22). RPTE cells were subjected to synchronized infection with BKPyV, and samples were treated with epoxomicin at different time points postadsorption, beginning with 0 h. Whole-cell lysates were harvested at 24 hpi, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for the early protein, TAg, as a readout for genome delivery to the nucleus. Compared to untreated cells, samples with epoxomicin added at time points until 18 hpi were inhibited for infection by BKPyV (Fig. 1, top). These data indicated that BKPyV no longer required proteasome function after approximately 18 hpi. These kinetics fit within the range of time between ER trafficking and nuclear entry; BKPyV traffics through the ER between 8 hpi and 16 hpi (9), and early gene expression can be detected beginning at about 24 hpi (3).

Fig 1.

Time course of proteasome and ERAD pathway involvement during infection. RPTE cells were infected at 5 IU/cell at 4°C for 1 h, moved to 37°C, and treated at the indicated time points with either 10 μM epoxomicin (Epox) or 10 μM Eeyarestatin I (EerI). Whole-cell lysates were harvested at 24 hpi, resolved by reducing SDS-PAGE, and probed for TAg and GAPDH. Similar results were obtained for at least 3 independent experiments. M, mock infected; UT, untreated.

Since the proteasome can function independently from the ERAD system, we decided to address the role of the ERAD pathway during early infection with the ERAD inhibitor, Eeyarestatin I (23). Eeyarestatin I targets the AAA-ATPase p97, which lies upstream of the proteasome as a cytosolic component of the ERAD pathway and is thought to provide the driving energy for extraction of ERAD substrates from the ER (24). Interestingly, similar inhibition kinetics were seen with Eeyarestatin I as with epoxomicin, a block in TAg expression until 18 hpi (Fig. 1, bottom), which supports the possibility that the proteasome may act as part of the ERAD pathway to allow BKPyV to exit from the ER. Together, these data support a role for the proteasome and ERAD during entry of BKPyV, at a step between ER trafficking and nuclear entry.

Trafficking of BKPyV is altered by proteasome inhibition.

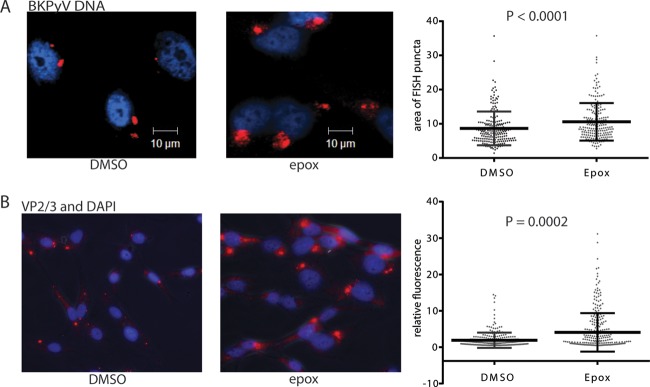

To corroborate results from the drug treatment time course, we employed an imaging approach to assess the effects of ERAD inhibition on BKPyV trafficking. RPTE cells were infected with BKPyV and then treated with epoxomicin or the vehicle DMSO at 6 hpi. Cell viability was not affected under these conditions. BKPyV DNA was detected by FISH with a fluorescently labeled probe that recognizes the viral genome. At 24 hpi, FISH signals appeared as puncta throughout the cell, with some signal adjacent to the nucleus. In the presence of epoxomicin, there was a change in the pattern of FISH signals: we saw a slight but reproducible increase in the average area of the puncta, representing an accumulation of the virus, in a juxtanuclear position (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

BKPyV trafficking is altered when ERAD is inhibited. RPTE cells were infected at 5 IU/cell at 4°C for 1 h and then moved to 37°C. Cells were treated with 10 μM epoxomicin (epox) or DMSO at 6 hpi and fixed at 24 hpi. (A) BKPyV was stained by FISH against the viral genome, and nuclei were stained with DAPI and then imaged by confocal microscopy. The relative size of fluorescent areas was measured using ImageJ software on >260 puncta from each condition collected from three independent experiments. (B) Fixed cells were stained for VP2/3 and DAPI and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Quantitation of relative fluorescence was performed on VP2/3 staining alone per cell using ImageJ software on a total of 200 cells from three independent experiments. Values are corrected total cell fluorescence to normalize for cell size. Statistical analysis for both panels was performed by independent-sample t test using GraphPad Prism software. Scatter plots show each data point value along with the mean and standard deviation.

FISH staining labels all viral genomes within the cell, regardless of whether they are following a productive or nonproductive pathway. Because of this ambiguity, we became interested in using a viral marker that more likely represents virus that is following a productive infectious pathway. As polyomavirus travels through the ER, the capsid begins to disassemble and rearrange (9, 14). The minor capsid proteins VP2 and VP3, which are normally hidden beneath the outer layer of VP1, become exposed and available for interactions with antibodies (13). Since VP2/3 exposure represents virus that has at least entered the ER and undergone some disassembly, an important prerequisite for infection, we decided to use VP2/3 staining to observe the effects of ERAD inhibitors on viral disassembly. RPTE cells were infected at an MOI of 5 IU/cell for 24 h, with epoxomicin added at 6 hpi, and fixed and labeled by indirect immunofluorescence against VP2/3. Compared to cells treated with DMSO, there was an increase in the intensity of VP2/3 staining in epoxomicin-treated cells (Fig. 2B). Exposure of VP2/3 to antibody recognition was prevented by brefeldin A (BFA) treatment, which inhibits ER trafficking of the virus (data not shown). These data showed that proteasome inhibition does not inhibit uncoating but seems to inhibit a later trafficking step such that it leads to some accumulation of uncoating intermediates.

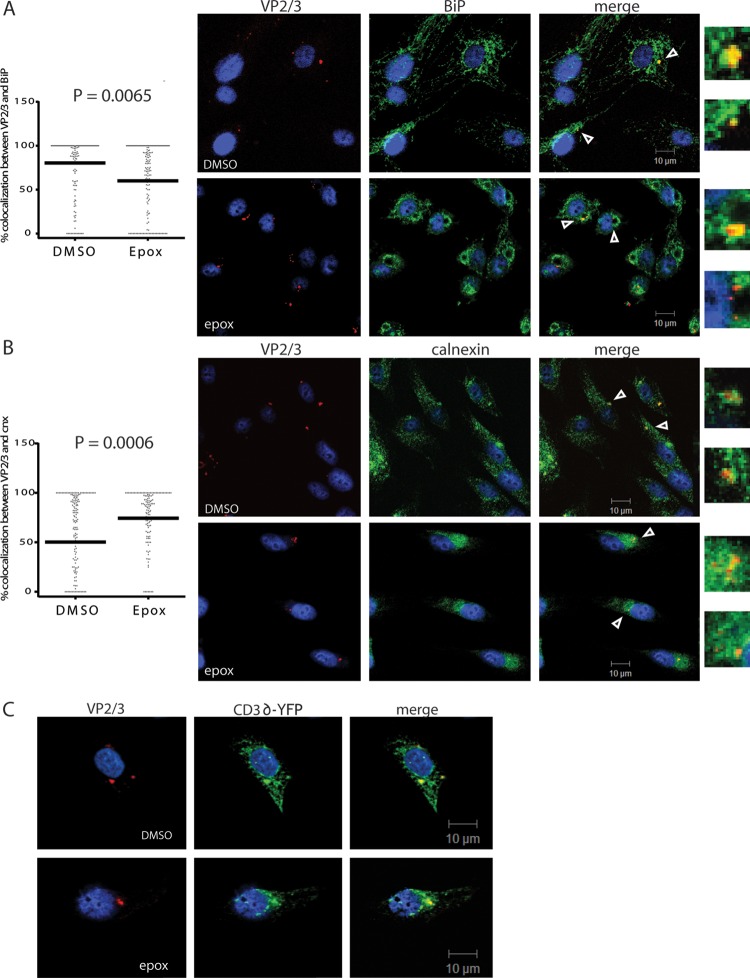

We hypothesized that if the proteasome was acting in the ERAD pathway, and the ERAD pathway was necessary for BKPyV trafficking out of the ER, then proteasome inhibition may lead to incoming virus becoming trapped within the ER. To address the localization of partially uncoated virus with the ER, we costained for VP2/3 and the ER marker BiP. We found that in both untreated cells and epoxomicin-treated cells there was a range of colocalization between VP2/3 and BiP at 24 hpi, between 0 to 100% per cell, with the median colocalization in untreated cells at 82% (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, however, we noticed that with epoxomicin treatment, the pattern of both VP2/3 and BiP staining changed: distinct areas became devoid of BiP, VP2/3 puncta became more localized to a juxtanuclear area, and median colocalization decreased to 53% (Fig. 3A). A number of reports have described an ERQC compartment where ERAD machinery becomes concentrated and substrates accumulate (25–27). This subcompartment is induced or exaggerated upon proteasome inhibition, possibly to sequester potentially harmful unfolded and aggregation-prone proteins, and is positive for calnexin while often devoid of BiP (25–27). Therefore, we next looked at calnexin costaining with VP2/3. In untreated cells, there was again partial colocalization between VP2/3 and calnexin, with the median at 50%. In contrast to the pattern of VP2/3 and BiP colocalization, there was a significant increase in colocalization between VP2/3 and calnexin with epoxomicin treatment, where median colocalization increased to 75% (Fig. 3B). These data showed that inhibition of the proteasome leads to relocalization of the virus to a calnexin-rich subregion of the ER that is deficient for the chaperone BiP.

Fig 3.

BKPyV behaves like an ERAD substrate. RPTE cells were infected at an MOI of 5 IU/cell and fixed at 24 hpi. Fixed cells were stained for VP2/3 and the ER marker (A) BiP or (B) calnexin (cnx), and images were taken by confocal microscopy. Arrowheads point to enlarged colocalized areas on the right. Colocalization of the individual VP2/3 puncta with calnexin or BiP was measured using MetaMorph software at the Center for Live Cell Imaging at the University of Michigan. Statistical analysis was performed as for Fig. 2. The line represents the median colocalization for each condition. (C) RPTE cells were transfected with CD3δ-YFP and the medium was changed at 12 h posttransfection. Transfected cells were infected at 5 IU/cell at 24 h posttransfection, treated with 10 μM epoxomicin at 6 hpi, and fixed at 24 hpi (48 h posttransfection). Fixed cells were then stained for CD3δ-YFP with anti-GFP and capsid proteins with anti-VP2/3 and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Since the changing colocalization of BKPyV with BiP or calnexin suggested that BKPyV may be handled like an ERAD substrate, we asked whether the virus might colocalize with a commonly studied ERAD-targeted protein. We chose to examine CD3δ, a transmembrane protein subunit of the T cell receptor complex that is sent through the ERAD pathway when it is not assembled into the complex (28). RPTE cells were transfected with a CD3δ-yellow fluorescent protein (CD3δ-YFP) construct and then infected with BKPyV 24 h posttransfection. Cells were fixed at 24 hpi and stained for VP2/3 and YFP to identify the transfected CD3δ. Confocal microscopy showed that VP2/3 and CD3δ colocalized within the ER at 24 hpi during normal infection and remained associated with CD3δ in the presence of proteasome inhibition (Fig. 3C). We could not quantify colocalization with CD3δ-YFP because transfection efficiency is extremely low in RPTE cells. Overall, these data suggest that BKPyV is shuttled to the same location with the ER as a substrate of the ERAD system, possibly due to interaction of BKPyV with the same recognition factors as a bona fide ERAD substrate.

BKPyV enters the cytosol after ER trafficking occurs.

The route taken by BKPyV into the nucleus after trafficking through the ER is unknown. The two possible pathways that have been proposed include crossing the ER membrane into the cytosol, from where the virus then undergoes active transport into the nucleus, or crossing the inner nuclear membrane directly into the nucleus without passing through the cytosol. To address the question of whether BKPyV traffics through the cytosol during infection, a biochemical assay was employed that allows for separation of a cellular lysate into a cytosol-containing fraction and a fraction including membrane-containing cellular components. Low-percentage digitonin treatment selectively permeabilizes the plasma membrane by targeting the more cholesterol-rich membrane while leaving organelle membranes intact (29). This assay was previously used for measuring retrotranslocation of ERAD substrates and is well established as a means to address cytosolic entry of polyomaviruses (29, 30).

Employing this fractionation, we first asked whether we could see the appearance of monomeric VP1 capsid protein, which is a product of disulfide bond reduction in the ER, in the cytosol over time (9). To do so, we resolved the protein fractions using nonreducing SDS-PAGE. In this assay, only VP1 monomers, pentamers, or oligomers from viral capsids that have undergone reduction or isomerization in the cell migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix. We harvested infected cells under alkylating conditions, to prevent any postharvest disulfide bond isomerization, at various time points after infection and isolated the cytosolic fraction via the digitonin permeabilization method. The integrity of the fractionation was confirmed by the absence of the ER protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and presence of GAPDH in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4A). We were able to detect monomer bands as well as higher-molecular-weight bands in the cytosolic fraction. We observed the appearance of VP1 monomers in the supernatant beginning at approximately 18 hpi, with a slight increase in monomers over time (Fig. 4A). This timing was consistent with the timing of ER trafficking of BKPyV. As expected, treatment with the ER trafficking inhibitor BFA reduced the appearance of monomers in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4B). Monomers were not completely absent in the cytosolic fraction, most likely because we could only treat with BFA for 2 h before it became toxic. This may have allowed time for some virus to reach the ER early or for retrograde transport to regain function (31). The appearance of ER proteins (BiP or PDI) in the cytosolic fraction of BFA-treated samples was seen consistently. This may be explained by the disruption of secretory pathways by BFA and the potential for these ER proteins to undergo export from the ER in small vesicles that may be present in the cytosolic fraction (32).

Fig 4.

BKPyV enters the cytosol. (A) RPTE cells were infected at 5 IU/cell, harvested at the indicated time points under alkylating conditions, and fractionated into pellet and supernatant fractions. Fractions were separated by nonreducing SDS-PAGE and probed for VP1, ER marker PDI, and cytosolic marker GAPDH. One-third of the protein for the supernatant was loaded for the pellet fractions, and the film was exposed for a shorter time. VP1 bands here include monomers and higher-molecular-weight species that have entered the nonreducing gel. (B) RPTE cells were infected at 5 IU/cell and treated at 6 hpi for 2 h with 1.25 μg/ml BFA or left untreated, harvested at 16 hpi under alkylating conditions, and then separated into pellet and supernatant fractions. Fractions were resolved by nonreducing SDS-PAGE and probed as described above but with BiP as the ER marker. “VP1” here represents monomers that have entered the nonreducing gel. (C) RPTE cells were infected with biotinylated BKPyV at 5 IU/cell, harvested at 16 hpi under alkylating conditions, and assayed as described for panel A. The Western blot was first probed with streptavidin-HRP to show the presence of biotinylated VP1 monomer (biotin-VP1) and then probed for VP1, PDI, and GAPDH.

To ensure that the VP1 in the cytosolic fraction indeed represented incoming BKPyV rather than VP1 that was newly synthesized during infection, purified BKPyV was labeled with biotin. RPTE cells were infected as described above and harvested at 24 hpi. The Western blot, probed with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase, showed a band in the cytosolic fraction that ran at slightly lower mobility than the VP1 in the unlabeled virus-infected fractions (Fig. 4C). We noted that biotinylation of VP1 prevented recognition by the VP1 monoclonal antibody. The presence of biotinylated VP1 in supernatant indicated that the protein visualized in the cytosolic fraction in Fig. 4A is indeed from the infecting virus. These data together support our conclusion that the VP1 monomer visualized in the cytosolic fraction is from incoming virus.

Inhibition of ERAD does not prevent BKPyV VP1 entry into the cytosol.

The previous experiments suggested that ERAD plays a role in BKPyV exit from the ER. We next wanted to test whether the proteasome inhibitor or ERAD inhibitor would therefore prevent entry of BKPyV into the cytosol, since ER exit and the proteasome are usually tightly linked (18, 33). RPTE cells were infected at an MOI of 5 IU/cell and treated at 6 hpi with epoxomicin or Eeyarestatin I, harvested at 16 hpi, and separated into pellet and cytosolic fractions; proteins were resolved by nonreducing SDS-PAGE and probed for VP1. Unexpectedly, neither inhibitor prevented VP1 monomers from appearing in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 5A), and in fact, treatment with epoxomicin led to an increase in the VP1 monomer signal in the supernatant fraction compared to cells treated with DMSO alone. We also saw a consistent increase in monomeric VP1 in the pellet fraction with epoxomicin treatment, while there was a decrease with Eeyarestatin I.

Fig 5.

ERAD inhibition does not prevent cytosolic entry of BKPyV. (A) RPTE cells were infected with BKPyV at 5 IU/cell at 4°C for 1 h and treated with 10 μM epoxomicin (Epox), 10 μM Eeyarestatin I (EerI), or DMSO at 6 hpi, harvested at 16 hpi under alkylating conditions, then separated into pellet and cytosolic fractions, and assayed as for Fig. 4. (B) BKPyV genomic DNA isolated from treated and untreated supernatant fractions was measured by qPCR and normalized to untreated levels. Averages from three independent experiments are shown, with error bars representing standard deviations. A one-tailed t test was performed; the significance for BFA treatment was a P value of 0.0008, and that for epoxomicin treatment was 0.03. Eeyarestatin I treatment did not cause a significant decrease in DNA.

We also examined whether viral genomes were present within the cytosolic fraction and whether their appearance was sensitive to the inhibitors. Viral DNA was isolated from equal amounts of the supernatant protein fractions treated with proteinase K followed by isolation of DNA on a PCR purification column. The proteinase K treatment was performed to release viral genomic DNA that may have been still associated with partially disassembled capsids. In agreement with VP1 monomer levels, there was much less viral DNA in the cytosol of infected cells treated with BFA (Fig. 5B). As opposed to the increase in VP1 monomers in the cytosol of epoxomicin-treated cells, however, there was approximately 2-fold less viral DNA. In the cytosol of cells treated with Eeyarestatin I, there was no consistent difference in viral DNA levels.

Trafficking requirements differ between viruses and cell types.

Recent studies have shown that trafficking from the ER to the cytosol of the closely related polyomavirus SV40 is blocked when the proteasome or ERAD is inhibited, based on appearance of SV40 capsid proteins in the cytosol (15, 16, 30). Since our results with BKPyV in RPTE cells differ from what has been published for SV40 in CV-1 cells, we decided to examine the trafficking of BKPyV in CV-1 cells. To improve the infectivity of BKPyV, we first incubated CV-1 cells with the BKPyV receptor GT1b. Cells were then infected with BKPyV, harvested at 16 hpi under alkylating conditions, and fractionated into pellet and supernatant fractions. Interestingly, there seemed to be little to no effect of epoxomicin treatment on the appearance of VP1 monomers in the cytosol, even though TAg expression was inhibited (data not shown) and BFA treatment still led to a consistent decrease in VP1 monomers (Fig. 6A). Next, we looked at viral DNA levels in the cytosol using qPCR as described above. Viral genomes were inhibited from entering the cytosol by both BFA and epoxomicin, similar to what was seen in RPTE cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig 6.

Cell-type-specific requirements for polyomavirus trafficking. (A) CV-1 cells were infected with BKPyV and treated with BFA, epoxomicin (Epox), or DMSO as for Fig. 5A. Pellet and supernatant fractions were separated and assayed as for Fig. 4. (B) BKPyV genomic DNA from the CV-1 supernatant fractions was quantified by qPCR and represented as in Fig. 4B. A t test determined significance of the decrease in BFA treatment to be a P value of 0.02 and for epoxomicin treatment to be a P value of 0.02. (C) RPTE or CV-1 cells were inoculated with 5 IU/cell SV40 at 4°C for 1 h, then moved to 37°C, and incubated in the presence of 10 μM epoxomicin, 10 μM Eeyarestatin I (EerI), or DMSO. RPTE cells were incubated for 24 h with 3.2 μM ganglioside GM1 prior to infection. Whole-cell lysates were harvested at 24 hpi, resolved by reducing SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed for TAg. (D) As in panel C, RPTE cells were infected with 5 IU/cell SV40 in the presence of 1.25 μg/ml BFA, 10 μM epoxomicin, 10 μM Eeyarestatin I, or DMSO. Proteins were harvested under alkylating conditions at 10 hpi and fractions analyzed as for Fig. 4. The Western blot was probed for SV40 VP1 monomers, PDI, and GAPDH. (E) SV40 genomic DNA was isolated and quantified by qPCR. Values for each condition were normalized to untreated levels; the averages from three independent experiments are represented, with error bars showing the standard deviations. A t test was performed for each condition; the significance in CV-1 cells was a P value of 0.008 for BFA treatment, with no significant decrease for epoxomicin treatment. In RPTE cells, a P value of 0.01 for BFA treatment and a P value of 0.01 for epoxomicin treatment were considered significant.

Next, we wanted to evaluate the effect of our inhibitors on SV40 infection in both CV-1 cells and RPTE cells. First, we determined whether the inhibitors could prevent infection of CV-1 cells. To allow productive infection of RPTE cells with SV40, cells were incubated with the SV40 receptor, ganglioside GM1, for 24 h before infection (3). Interestingly, epoxomicin treatment strongly inhibited infection in both cell types, as assayed by TAg expression, but Eeyarestatin I inhibited infection only of RPTE cells (Fig. 6C). Since there was no effect on infection, turnover of transfected CD3δ-YFP was used to confirm that Eeyarestatin I was indeed inhibiting ERAD in CV-1 cells (data not shown). The different effects of epoxomicin and Eeyarestatin I on SV40 TAg expression suggest that requirements for infection differ between these cell types.

Next, we wanted to address SV40 cytosolic trafficking in the RPTE cell system. After incubation with GM1, RPTE cells were infected with SV40 at an MOI of 5 IU/cell and fractionation was performed at 10 hpi to separate membrane-bound organelles and cytosolic components. This infection was shorter because SV40 traffics more rapidly than BKPyV, with TAg expression detectable at 12 hpi by Western blotting (data not shown). As shown in the top portion of Fig. 6D, epoxomicin inhibited SV40 VP1 monomers from entering the cytosol of CV-1 cells, as has been previously reported (15, 30). However, appearance of cytosolic SV40 VP1 was not inhibited in RPTE cells: VP1 monomers increased in the cytosolic fraction when cells were treated with epoxomicin (Fig. 6D, bottom portion) in the same way as seen with BKPyV (Fig. 5). For both cell types, Eeyarestatin I prevented SV40 VP1 monomers from appearing in the cytosol, which was interesting since the drug does not inhibit infection in CV-1 cells (Fig. 6C). In RPTE cells, the SV40 VP1 monomers accumulated in the pellet under epoxomicin treatment and decreased in the pellet with Eeyarestatin I treatment, while in CV-1 cells, there was not a noticeable change in VP1 monomer levels of the pellet. BFA strongly inhibited VP1 from appearing in the pellet in CV-1 cells, however. Finally, we looked at SV40 DNA levels in the cytosolic fractions of both CV-1 and RPTE cells. Although the appearance of VP1 protein within the cytosol was affected differently by epoxomicin and Eeyarestatin I, we saw a similar decrease in cytosolic viral genomes (Fig. 6E). Together, these data suggest that the appearance of VP1 protein within the cytosol does not correlate with viral genomes.

DISCUSSION

Uncovering the mechanism of virus entry and trafficking is important for understanding viral pathogenesis and identifying antiviral targets. Furthermore, since viruses are obligate intracellular pathogens, studies of host-virus interactions often elucidate unknown intracellular pathways and illuminate known pathways, adding to the understanding of basic cellular biology. Previous findings implicated components of the ERAD pathway, including the proteasome, during early events of polyomavirus infection (9, 15, 16, 30). The possibility of ERAD involvement led us to pursue the role of the proteasome during BKPyV infection and whether it was acting in the context of the ERAD pathway and possibly in viral trafficking out of the ER. In this study, we have found that BKPyV requires a functional proteasome and ERAD pathway during entry, and we also found that inhibition of these cellular mechanisms leads to a sequestration of BKPyV within an ER quality control subcompartment. Additionally, we have found that both BKPyV and SV40 capsid proteins and DNA reach the cytosol during infection in both RPTE cells and CV-1 cells. Interestingly, we have found that the appearance of VP1 monomers in the cytosol is independent of ERAD function, and a number of differences exist between cell types and between viruses.

We hypothesized that proteasome function was required during BKPyV entry, and we found that the proteasome played a role at an early point during infection by examining sensitivity to epoxomicin treatment. Proteasome function was required before 18 hpi, which is a time point after ER trafficking as determined previously by treatment with the retrograde trafficking inhibitor BFA (9). In addition, we know that epoxomicin does not inhibit TAg gene transcription when TAg is expressed from a transfected plasmid (data not shown). A role for the ERAD pathway was supported by the treatment time course with Eeyarestatin I, which also inhibited TAg expression when added before 18 hpi. We also found that reduction of p97 protein, the target of Eeyarestatin I, by siRNA led to inhibition of infection (data not shown); however, cytotoxic effects were observed in the p97 knockdown cells, causing us to view this result with caution.

Since inhibition of the ERAD pathway abrogated infection, we were interested in visualizing where the blockage was occurring within the cell. We hypothesized that if BKPyV was unable to traffic to the nucleus without the ERAD pathway, we might see an accumulation of virus outside the nucleus. In support of this, we saw a reproducible increase in the amount of virus genome accumulating, much of it in a juxtanuclear position. We then visualized partially uncoated virus particles by staining for the minor capsid proteins VP2 and VP3, which become available to antibody recognition only after capsid disassembly begins. Interestingly, we observed a change in the morphology of the ER following epoxomicin treatment, as ER-resident proteins BiP and calnexin showed different staining patterns, suggesting their partitioning to different ER subdomains. BKPyV localization within the ER also changed, colocalizing more with calnexin under proteasome inhibition than under untreated conditions. A number of recent studies describe an ERQC subcompartment that is enriched in certain ERAD and ERQC factors, including calnexin, but is devoid of other ER proteins such as BiP (25–27). This subcompartment is exaggerated upon proteasome inhibition, and ERAD factors and substrates such as CD3δ accumulate within this area (26). If BKPyV is handled like an ERAD substrate, an increase in the concentration of viral disassembly factors within the ERQC compartment may explain the accumulation of partially disassembled virus in the epoxomicin-treated cells, as shown by the increase in total VP2/3 immunofluorescence. In further support of BKPyV acting as an ERAD substrate, we detected colocalization between BKPyV and CD3δ, and this colocalization was still detected under proteasome inhibition.

Recent findings with SV40 support the role of ER-localized ERAD components during polyomavirus passage into the cytosol. These factors include DnaJ chaperone family proteins and the abundant ER chaperone BiP, all discovered in unbiased siRNA screens for modulators of SV40 infection (16). These factors were shown to be necessary after partial disassembly and VP2/3 exposure but before cytosolic entry of SV40. Another ERAD protein, Bap31, was also found to be necessary for entry of SV40 into the cytosol, and these authors found that an interaction between VP2 and Bap31 was necessary for cytosolic entry (15). Interestingly, Bap31 has been described as a shuttle for ERAD substrates to the ERQC compartment (25). Proteasome inhibition may increase the concentration of other ERAD substrates, titrating Bap31 away from the virus and thus decreasing ER exit of the virus particle. In addition, this may cause BiP to move away from the ERQC compartment and BKPyV.

In support of a role for an ER-to-cytosol entry step, we detected VP1 monomers in the cytosol at a time point that follows ER trafficking. Detection of VP1 protein by nonreducing SDS-PAGE supports the conclusion that the capsid protein in the cytosol has first passed through the ER, where it has undergone reduction and/or isomerization by oxidoreductases, especially since VP1 monomers are diminished in the presence of BFA. The amount of VP1 is just above the limit of detection by Western blotting, suggesting that a very low percentage of input virus particles reach the cytosol. Because of detection issues, we were not able to use VP2/3 as a readout for virus in the cytosol by Western blotting.

The appearance of BKPyV capsid protein in the cytosol, along with ERAD involvement, points to a co-opting of the ER-to-cytosol retrotranslocation pathway by the virus. Surprisingly, however, we were not able to prevent appearance of VP1 monomers with ERAD inhibition by epoxomicin or Eeyarestatin I in RPTE cells. Rather, we saw an accumulation of VP1 monomers in the cytosol in the presence of epoxomicin, and no difference with Eeyarestatin I. Since the ERAD inhibitors prevent infection as measured by TAg expression, these data seemed to go against the hypothesis that inhibition of the proteasome and ERAD pathway would prevent trafficking of BKPyV out of the ER. For this reason, we asked whether the viral genome was also reaching the cytosol, since transport of the viral genome to the nucleus is necessary in any potential productive pathway. Interestingly, in the presence of epoxomicin, there was a decrease in BKPyV genomes present in the cytosol. These changes in viral DNA levels within the cytosol support the possibility that some infectious virus particles may be trapped within the ER when ERAD is inhibited, even though VP1 protein can still enter the cytosol. The inconsistent effects of Eeyarestatin I treatment on viral DNA levels in the cytosol may suggest that the inhibitor is targeting other trafficking pathways besides ERAD that lead to inhibition of TAg expression.

A number of recent studies have evaluated ER-to-cytosol trafficking of SV40 based on the presence of capsid protein VP1 in the cytosol. Our studies, however, seem to suggest that VP1 and viral genomes may represent different events or pathways, separate or overlapping. Importantly, these events differ between cell types and even between viruses. Compared to infected RPTE cells, BKPyV-infected CV-1 cells show a different phenotype of VP1 entry into the cytosol, where there seems to be no difference between epoxomicin-treated and untreated cells. And as has been previously published (15, 30), SV40 VP1 does not enter the cytosol in epoxomicin-treated CV-1 cells, while in RPTE cells it undergoes the same accumulation as BKPyV. While the variation in levels of cytosolic VP1 in the presence of trafficking inhibitors suggests that virus trafficking may differ between cell types, the effect on cytosolic viral genomes is similar in each cell type and between viruses.

The level of viral genomes in the cytosol with epoxomicin treatment ranged from about 50% of the value without treatment for BKPyV to about 80% for SV40. Although an inhibitory effect of epoxomicin treatment is consistent with proteasome function being required for ER exit, the fact that TAg expression is much more strongly inhibited in the presence of the inhibitors than the cytosolic entry of viral DNA raises the question of whether the viral genomes in the cytosol are part of the infectious pathway. If cytosolic trafficking is a productive pathway, perhaps the proteasome acts after transport of the infectious particle across the ER membrane. On the other hand, our results could be explained by nonspecific effects of proteasome inhibition: i.e., aggregates or other misfolded obstructions within the ER lumen would prevent effective passage of virus through the ER to its next proper destination. This nonspecific effect is supported by the change in ER morphology and accumulation of disassembled virus that we observe under proteasome inhibition. This result is consistent with a possible model in which the cytosolic viral components represent a nonproductive or dead-end pathway. Originally, inhibition of SV40 VP1 from entering the cytosol by epoxomicin in CV-1 seemed to support cytosolic trafficking as a productive pathway, since it correlated with a block in TAg expression. However, SV40 VP1 monomers are also inhibited by Eeyarestatin I even though the drug does not inhibit overall infection. Moreover, in RPTE cells, VP1 monomers from both viruses can enter the cytosol under either drug treatment, while TAg expression is prevented with both treatments.

This study raises an interesting question about differences in the biology of the cell types used for studying polyomavirus entry. It is well accepted that protein expression levels (34), cell cycle regulation (35), and other aspects of cell biology differ between cell types, and these discrepancies should be considered when studying cell biology of a viral infection. We also cannot rule out species-specific behavior of cells. The experiments in this report were performed with primary cells that are a natural host cell of BKPyV and are more likely to represent the biology of BKPyV lytic infection in the natural host.

Previous results also have questioned whether SV40 travels through the cytosol as its productive route of infection. Some studies have shown transient disturbances in the nuclear membrane that occur around the time of nuclear entry (6, 36), suggesting that trafficking from the ER to the nucleus occurs by crossing the inner nuclear membrane through temporary disruption in the lipid bilayer. This model cannot yet be ruled out to describe BKPyV nuclear entry. One interesting thing to consider is the hydrophobic nature of the minor capsid proteins. Both VP2 and VP3 of SV40 have been previously shown to have membrane lytic properties and to be able to at least partially insert into ER membranes (37). If the virion can penetrate the ER membrane to enter the cytosol, then it is reasonable to believe that it may also be able to penetrate the inner nuclear membrane to gain direct access to the nucleus. Penetration may be limited to a membrane that is contacting the cytosol if specific cytosolic proteins are required for the process. Also, even though there is no precedent for an ERAD substrate to be translocated into the nucleus, an inner nuclear membrane-localized ERAD E3 ligase has been identified in yeast and may suggest a way for the ERAD pathway to be combined with direct nuclear entry (38). Another possibility that would further support cytosolic trafficking as a productive pathway is if a disassembly step occurs within the cytosol. A better understanding of BKPyV disassembly will be required before the process of nuclear entry can be fully elucidated.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates involvement of the ERAD pathway during BKPyV entry and infection and provides evidence that there are complex interactions between polyomaviruses and the host cell machinery. Additionally, the data presented here regarding the observed cell type differences in polyomavirus trafficking call for reexamination of the current paradigm for cytosolic trafficking of polyomaviruses. This study emphasizes the relevance of primary cell models of infection and provides avenues for further investigation to determine how polyomaviruses enter the cell nucleus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Billy Tsai, Christiane Wobus, Akira Ono, and Kathleen Collins for critical review of the manuscript. We also appreciate the reagents and assistance in experiments from Billy Tsai and Takamasa Inoue. We additionally thank the Microscopy and Imaging Analysis Laboratory and Sam Straight from the University of Michigan Center for Live Cell Imaging for assistance with microscopy and colocalization analysis, respectively.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI060584 to M.J.I. and in part by NIH grant CA046592 to the University of Michigan Cancer Center. S.M.B. was supported by the Mary Sue and Kenneth Coleman Award.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Bennett SM, Broekema NM, Imperiale MJ. 2012. BK polyomavirus: emerging pathogen. Microbes Infect. 14:672–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuypers DR. 2012. Management of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 8:390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Low J, Humes HD, Szczypka M, Imperiale M. 2004. BKV and SV40 infection of human kidney tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Virology 323:182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drachenberg CB, Beskow CO, Cangro CB, Bourquin PM, Simsir A, Fink J, Weir MR, Klassen DK, Bartlett ST, Papadimitriou JC. 1999. Human polyoma virus in renal allograft biopsies: morphological findings and correlation with urine cytology. Hum. Pathol. 30:970–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nickeleit V, Hirsch HH, Zeiler M, Gudat F, Prince O, Thiel G, Mihatsch MJ. 2000. BK-virus nephropathy in renal transplants—tubular necrosis, MHC-class II expression and rejection in a puzzling game. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 15:324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC, Wali R, Cubitt CL, Ramos E. 2003. BK polyoma virus allograft nephropathy: ultrastructural features from viral cell entry to lysis. Am. J. Transplant. 3:1383–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eash S, Atwood WJ. 2005. Involvement of cytoskeletal components in BK virus infectious entry. J. Virol. 79:11734–11741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moriyama T, Sorokin A. 2008. Intracellular trafficking pathway of BK virus in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Virology 371:336–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang M, Abend JR, Tsai B, Imperiale MJ. 2009. Early events during BK virus entry and disassembly. J. Virol. 83:1350–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li TC, Takeda N, Kato K, Nilsson J, Xing L, Haag L, Cheng RH, Miyamura T. 2003. Characterization of self-assembled virus-like particles of human polyomavirus BK generated by recombinant baculoviruses. Virology 311:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsai B, Qian M. 2010. Cellular entry of polyomaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 343:177–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stehle T, Gamblin SJ, Yan Y, Harrison SC. 1996. The structure of simian virus 40 refined at 3.1 A resolution. Structure 4:165–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Norkin LC, Anderson HA, Wolfrom SA, Oppenheim A. 2002. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 is followed by brefeldin A-sensitive transport to the endoplasmic reticulum, where the virus disassembles. J. Virol. 76:5156–5166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schelhaas M, Malmstrom J, Pelkmans L, Haugstetter J, Ellgaard L, Grunewald K, Helenius A. 2007. Simian virus 40 depends on ER protein folding and quality control factors for entry into host cells. Cell 131:516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geiger R, Andritschke D, Friebe S, Herzog F, Luisoni S, Heger T, Helenius A. 2011. BAP31 and BiP are essential for dislocation of SV40 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1305–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodwin EC, Lipovsky A, Inoue T, Magaldi TG, Edwards AP, Van Goor KE, Paton AW, Paton JC, Atwood WJ, Tsai B, DiMaio D. 2011. BiP and multiple DNAJ molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum are required for efficient simian virus 40 infection. mBio 2:e00101–11. 10.1128/mBio.00101-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lilley BN, Gilbert JM, Ploegh HL, Benjamin TL. 2006. Murine polyomavirus requires the endoplasmic reticulum protein Derlin-2 to initiate infection. J. Virol. 80:8739–8744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. 2011. Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 334:1086–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abend JR, Low JA, Imperiale MJ. 2007. Inhibitory effect of gamma interferon on BK virus gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 81:272–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Menéndez-Benito V, Verhoef LG, Masucci MG, Dantuma NP. 2005. Endoplasmic reticulum stress compromises the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:2787–2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harlow E, Whyte P, Franza BR, Jr, Schley C. 1986. Association of adenovirus early-region 1A proteins with cellular polypeptides. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:1579–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meng L, Mohan R, Kwok BH, Elofsson M, Sin N, Crews CM. 1999. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:10403–10408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q, Li L, Ye Y. 2008. Inhibition of p97-dependent protein degradation by Eeyarestatin I. J. Biol. Chem. 283:7445–7454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolf DH, Stolz A. 2012. The Cdc48 machine in endoplasmic reticulum associated protein degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823:117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wakana Y, Takai S, Nakajima K, Tani K, Yamamoto A, Watson P, Stephens DJ, Hauri HP, Tagaya M. 2008. Bap31 is an itinerant protein that moves between the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and a juxtanuclear compartment related to ER-associated degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:1825–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kondratyev M, Avezov E, Shenkman M, Groisman B, Lederkremer GZ. 2007. PERK-dependent compartmentalization of ERAD and unfolded protein response machineries during ER stress. Exp. Cell Res. 313:3395–3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kamhi-Nesher S, Shenkman M, Tolchinsky S, Fromm SV, Ehrlich R, Lederkremer GZ. 2001. A novel quality control compartment derived from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:1711–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang M, Omura S, Bonifacino JS, Weissman AM. 1998. Novel aspects of degradation of T cell receptor subunits from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in T cells: importance of oligosaccharide processing, ubiquitination, and proteasome-dependent removal from ER membranes. J. Exp. Med. 187:835–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Le Gall S, Neuhof A, Rapoport T. 2004. The endoplasmic reticulum membrane is permeable to small molecules. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inoue T, Tsai B. 2011. A large and intact viral particle penetrates the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to reach the cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002037. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ulmer JB, Palade GE. 1991. Effects of brefeldin A on the Golgi complex, endoplasmic reticulum and viral envelope glycoproteins in murine erythroleukemia cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 54:38–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takemoto H, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Miyata Y, Yahara I, Inoue K, Tashiro Y. 1992. Heavy chain binding protein (BiP/GRP78) and endoplasmin are exported from the endoplasmic reticulum in rat exocrine pancreatic cells, similar to protein disulfide-isomerase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 296:129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mancini R, Fagioli C, Fra AM, Maggioni C, Sitia R. 2000. Degradation of unassembled soluble Ig subunits by cytosolic proteasomes: evidence that retrotranslocation and degradation are coupled events. FASEB J. 14:769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pan C, Kumar C, Bohl S, Klingmueller U, Mann M. 2009. Comparative proteomic phenotyping of cell lines and primary cells to assess preservation of cell type-specific functions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8:443–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Geiger T, Wehner A, Schaab C, Cox J, Mann M. 2012. Comparative proteomic analysis of eleven common cell lines reveals ubiquitous but varying expression of most proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11:M111.014050. 10.1074/mcp.M111.014050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Butin-Israeli V, OBen-nun-Shaul Kopatz I, Adam SA, Shimi T, Goldman RD, Oppenheim A. 2011. Simian virus 40 induces lamin A/C fluctuations and nuclear envelope deformation during cell entry. Nucleus 2:320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Daniels R, Rusan NM, Wilbuer AK, Norkin LC, Wadsworth P, Hebert DN. 2006. Simian virus 40 late proteins possess lytic properties that render them capable of permeabilizing cellular membranes. J. Virol. 80:6575–6587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Swanson R, Locher M, Hochstrasser M. 2001. A conserved ubiquitin ligase of the nuclear envelope/endoplasmic reticulum that functions in both ER-associated and Matalpha2 repressor degradation. Genes Dev. 15:2660–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]