Abstract

Herpesvirus nucleocapsids are assembled in the nucleus, whereas maturation into infectious virions takes place in the cytosol. Since, due to their size, nucleocapsids cannot pass the nuclear pores, they traverse the nuclear envelope by vesicle-mediated transport. Nucleocapsids bud at the inner nuclear membrane into the perinuclear space, forming primary enveloped particles and are released into the cytosol after fusion of the primary envelope with the outer nuclear membrane. The nuclear egress complex (NEC), consisting of the conserved herpesvirus proteins (p)UL31 and pUL34, is required for this process, whereas the viral glycoproteins gB and gH, which are essential for fusion during penetration, are not. We recently described herpesvirus-induced nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) as an alternative egress pathway used in the absence of the NEC. However, the molecular details of this pathway are still unknown. It has been speculated that glycoproteins involved in fusion during entry might play a role in NEBD. By deleting genes encoding glycoproteins gB and gH from the genome of NEBD-inducing pseudorabies viruses, we demonstrate that these glycoproteins are not required for NEBD but are still necessary for syncytium formation, again emphasizing fundamental differences in herpesvirus-induced alterations at the nuclear envelopes and plasma membranes of infected cells.

INTRODUCTION

Herpesvirus maturation takes place in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of infected cells. After capsid assembly and DNA encapsidation in the nucleus, the newly formed nucleocapsids leave the nucleus by budding at the inner nuclear membrane and fission, resulting in a primary enveloped particle located in the perinuclear cleft. Subsequent fusion with the outer nuclear membrane releases the nucleocapsid into the cytosol, where final tegumentation and envelopment take place (reviewed in references 1–4).

The nuclear egress complex (NEC) consisting of conserved herpesvirus proteins homologous to pUL31 and pUL34 of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is necessary for efficient nuclear egress. The type II tail-anchored membrane protein pUL34 localizes to the nuclear envelope and interacts with the soluble nucleoplasmic pUL31, thereby linking it to the inner nuclear membrane (5, 6). The NEC recruits cellular (protein kinase C) and viral kinases (pUS3 and pUL13), which phosphorylate lamins, resulting in local dissolution of the nuclear lamina (7–10).

In the absence of either pUL31 or pUL34, viral replication is severely impaired but not totally abolished (5, 6, 11, 12). To uncover potential other pathways for leaving the nucleus, the residual infectivity of pseudorabies viruses (PrV) lacking pUL34 or pUL31 was used for serial passaging in cell culture. After repeated passaging infectious virus progeny designated as PrV-ΔUL34Pass and PrV-ΔUL31Pass could be isolated which efficiently replicated in the absence of either component of the NEC. In contrast to wild-type PrV, the passaged mutants leave the nucleus via a fragmented nuclear envelope designated as nuclear escape, thereby circumventing the need for NEC mediated vesicular transport (13, 14).

Whereas formation and fission of the primary envelope is mediated by the NEC, its fusion with the outer nuclear membrane remains enigmatic. It has been suggested that the herpesviral glycoproteins gB and gH, which are necessary for fusion during entry and for direct viral cell-to-cell spread, are also required for NEC-mediated nuclear egress (15). The trimeric gB is thought to be the core herpesviral fusion protein, since it exhibits strong structural homology to other class III viral fusion proteins, such as vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G (16). The role of the heterodimeric gH/gL complex in fusion is unclear. It has been speculated that it induces hemifusion, while the action of gB leads to expansion of the fusion pore, ultimately resulting in full fusion (17). However, these data were subsequently challenged (18). Unlike gB, gH does not exhibit any signatures typical for or homology to any other viral fusion protein, and recent data point to a regulatory role for the gH/gL complex (19), suggesting that gH/gL activates gB after receptor binding (20).

Although the relevance of gB and gH/gL for viral entry and direct cell-to-cell spread is undoubted, data on their significance during nuclear egress differ. In HSV-1 the simultaneous deletion of gB and gH resulted in the accumulation of primary enveloped virions in the perinuclear space with ∼5-fold reduced titers in the supernatant, whereas single deletion of either gB or gH showed little defect, indicating that the presence of either gB or gH is beneficial for nuclear egress (15). This contrasts with the situation in entry and direct cell-to-cell spread, for which either protein is essential. In addition, phosphorylation of gB by the alphaherpesvirus specific kinase pUS3 (21) could explain the accumulation of primary enveloped virions in the perinuclear space in the absence of pUS3 (22–24). In contrast, for PrV neither deletion of gB, gD, gH, or gL nor combined deletions of gB and gD, gB and gH, gD and gH, or gD, gH, and gL had any effect on nuclear egress. Moreover, ultrastructural immunolabeling studies did not detect viral glycoproteins in the inner nuclear membrane or in the primary virion envelope (25), making it highly unlikely that they are involved in nuclear egress in PrV. Thus, it has been suggested that cellular proteins of a hitherto cryptic vesicular nucleocytoplasmic transport pathway that is hijacked by the virus mediate nuclear egress. This assumption has been supported recently by the observation of nucleocytoplasmic transport of large cellular RNP complexes following a pathway resembling herpesvirus nuclear egress (26).

During characterization of pseudorabies virus mutants PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass, which are infectious in the absence of the NEC, we observed that infected cells form large syncytia, indicating that fusion is no longer strictly controlled in these mutant viruses, in contrast to wild-type PrV-infected cells. Thus, we speculated that nuclear envelope fragmentation might be the result of this excessive fusion activity. Here, we show by deleting either the gH or the gB gene from the genomes of PrV-ΔUL34Pass and PrV-ΔUL31Pass that nuclear envelope breakdown is not dependent on gH or gB, nor is virion formation in the cytosol. In contrast, syncytium formation by these mutant viruses still is, demonstrating that neither nuclear egress nor nuclear escape is dependent on the known viral fusion machinery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The generation of RK13-gH/gL (25) and RK13-gB cells (27) has been described. Deletion mutants lacking gB or gH were derived from PrV-ΔUL31Pass (13) and PrV-ΔUL34Pass (14). gH-negative mutants were isolated after cotransfection of PrV-ΔUL31Pass or PrV-ΔUL34Pass genomic DNA and plasmid TN77-ΔgHgfp into RK13-gH/gL cells. In the recombination plasmid, a 607-bp SmaI fragment within the gH open reading frame was deleted and substituted by a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression cassette under the control of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) immediate-early promoter/enhancer complex. For the deletion of gB, genomic DNA was cotransfected with plasmid P021, which also carries the GFP expression cassette (27) into RK13-gB cells. Transfection progeny was screened for autofluorescent plaques, which were picked and purified until only fluorescent plaques were visible. PrV-ΔgH and PrV-ΔgB derived from PrV strain Kaplan (PrV-Ka) (28) have been described (25, 27).

Western blotting.

For immunoblotting, RK13 cells were either infected with PrV-Ka, PrV-ΔgB, PrV-ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL31Pass, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass, PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 or infected with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB at an MOI of 0.2 or left uninfected. After 18 h, the cells were scraped into the supernatant, pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. The cell lysates were separated on SDS 10 or 12% polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with skim milk and subsequently incubated with monospecific rabbit sera against pUL31 (5), pUL34 (11), pUL38 (unpublished), gI (29), gB (30), or gH (31). Bound antibody was detected after incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) or, after incubation with monoclonal antibodies against gE (29), with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (Dianova). After incubation with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific), the blots were analyzed using an imager (VersaDoc; Bio-Rad).

Replication kinetics.

To establish kinetics of replication, RK13, RK13-gB (27), or RK13-gH/gL cells (25) were infected at an MOI of 0.1 and harvested at different times after a low-pH treatment (32). Cells were scraped into the supernatant and lysed by freezing at −70°C and thawing. Cellular debris was removed after centrifugation, and titers were determined on RK13, RK13-gB, or RK13-gH/gL cells. The mean values from three independent assays were calculated and plotted. The corresponding standard deviations are given.

Plaque assay.

RK13 cells in 6-well tissue culture dishes were infected under plaque assay conditions with 2 × 104 PFU in 1 ml with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH. The complementing cell lines RK13-gB and RK13-gH/gL were infected with 200 PFU/ml. For PrV-Ka, PrV-ΔUL31Pass, and PrV-ΔUL34Pass, 200 PFU/ml were used on RK13 cells, as well as on RK13 cells expressing gB and gH/gL. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were fixed with ethanol and stained with an antibody against the major capsid protein pUL19 (11). Antibody was detected after incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen) and photographed using a Nikon eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope.

Electron microscopy.

RK13 cells were infected with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH at an MOI of 1 or with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB at an MOI of 0.1. After 1 h, the inoculum was replaced by fresh medium. At the appropriate time after infection (16 h for PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH and 22 h for PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB), the cells were fixed and processed for electron microscopy as described previously (11). For quantitation of nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD), ca. 70 nuclei per virus infection were counted and differentiated into intact and ruptured nuclei.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of gB and gH deleted PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass.

PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass were isolated after several passages of either PrV-ΔUL31 or PrV-ΔUL34 in rabbit kidney (RK13) cells (13, 14). Both passaged mutants replicate to similar titers as PrV-Ka in RK13 cells, although they lack the NEC components pUL31 or pUL34. Nucleocapsids of the mutant viruses are released through a fragmented nuclear envelope, alleviating the need for NEC-mediated vesicular translocation. Since both passaged mutants, in contrast to the parental viruses, showed a highly syncytial phenotype in cell culture, it was speculated that enhanced fusogenicity might be the reason for the deregulation of nuclear envelope stability. To test this, gH or gB deletion mutants of PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass were isolated. To this end, genomic DNA of the passaged mutants was cotransfected with recombination plasmids expressing GFP instead of either gH- or gB-coding sequences. gB deletion viruses were isolated on RK13-gB and gH-negative mutants on RK13-gH/gL cells. RK13-gH/gL cells were used since they expressed gH more stably than single gH expressing cells (data not shown). Autofluorescent plaques were purified to homogeneity and further analyzed. Viral DNA was isolated and tested for correct deletion of gB or gH coding sequences and insertion of the GFP expression cassette by restriction enzyme digestion and Southern blotting (data not shown).

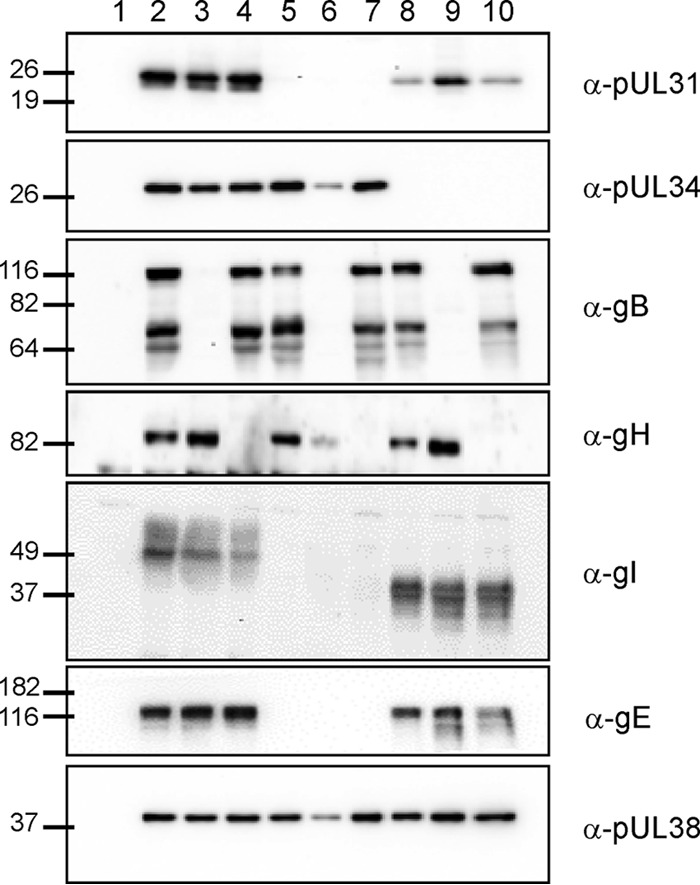

To examine protein expression of the generated deletion mutants, RK13 cells were infected with phenotypically complemented gB and gH deletion mutants and with the corresponding parental viruses and harvested after ∼18 h. Western blots were incubated with polyclonal sera directed against pUL31, pUL34, pUL38, gI, gB, or gH or with a monoclonal antibody specific for gE. As shown in Fig. 1, PrV-ΔUL31Pass and mutants derived from it lacked pUL31 as expected (Fig. 1, lanes 5 to 7). Similarly, PrV-ΔUL34Pass and corresponding mutants were negative for pUL34 (Fig. 1, lanes 8 to 10). gB could not be detected in lysates of cells infected with PrV-ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB (Fig. 1, lanes 3, 6, and 9), whereas gH was not expressed in PrV-ΔgH-, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH-, and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH-infected cells (Fig. 1, lanes 4, 7, and 10). Monospecific serum against the capsid triplex protein pUL38 served as a loading control, and anti-gI antibodies were used to differentiate the passaged viruses and mutants derived thereof, which comprise a mutation in gI, leading to a smaller expression product in PrV-ΔUL34Pass and the absence of gI in PrV-ΔUL31Pass due to a deletion in the unique short region eliminating the gene for its interaction partner gE (Fig. 1, lanes 5 to 7) (13). Viral protein expression was generally lower in cells infected with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, since the replication of this virus was not fully rescued on the complementing cells resulting in ∼10-fold-lower titers of virus progeny than with the other mutants. Therefore, only an MOI of 0.2 could be achieved.

Fig 1.

Western blot analysis. RK13 cells were infected at an MOI of 2 with PrV-Ka (lane 2), PrV-ΔgB (lane 3), PrV-ΔgH (lane 4), PrV-ΔUL31Pass (lane 5), PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH (lane 7), PrV-ΔUL34Pass (8), PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB (lane 9), and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH (lane 10) or at an MOI of 0.2 with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB (lane 6) and then harvested at 18 h postinfection. Uninfected cells (lane 1) were used as a control. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (10 or 12%), blotted, and incubated with antisera as indicated on the right. Molecular masses (in kDa) of marker proteins are indicated on the left.

Growth properties of gB- and gH-negative PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass virus mutants.

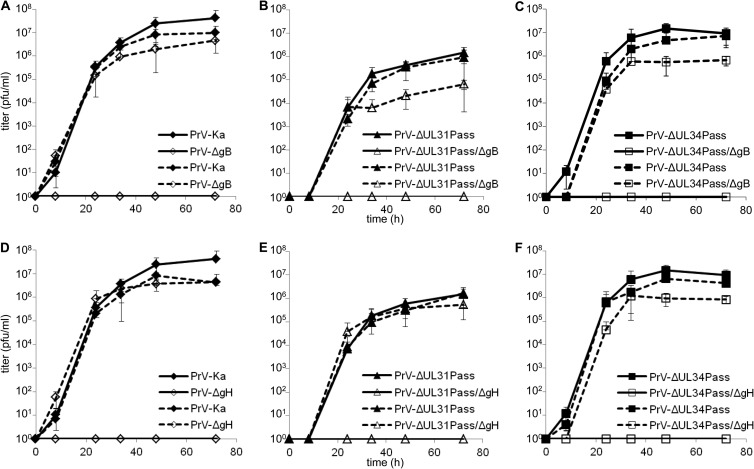

To test for in vitro replication of the gB- and gH-negative mutants, RK13 cells and cell lines expressing the wild-type glycoproteins gB and gH/gL were infected with an MOI of 0.1, harvested at different times postinfection, and titrated on complementing cells. As shown in Fig. 2, none of the gB or gH deletion viruses of either PrV-Ka or the passaged mutants was able to productively replicate on noncomplementing RK13 cells, whereas the replication defect was complemented on RK13-gB or RK13-gH/gL cells, respectively.

Fig 2.

Replication kinetics of PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass mutants lacking gB or gH. (A to C) RK13 (continuous line) or RK13-gB (dashed line) cells were infected with PrV-Ka and PrV-ΔgB (A), PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB (B), or PrV-ΔUL34Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB (C) at an MOI of 0.1. (D to E) RK13 (continuous line) or RK13-gH/gL (dashed line) cells were infected with PrV-Ka and PrV-ΔgH (D), PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH (E), or PrV-ΔUL34Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH (F), also at an MOI of 0.1. At the indicated time points postinfection, cells were scraped into the supernatant, and virus progeny titers were determined on RK13, RK13-gB, or RK13-gH/gL cells as appropriate. Mean values of three independent assays and the corresponding standard deviations are indicated.

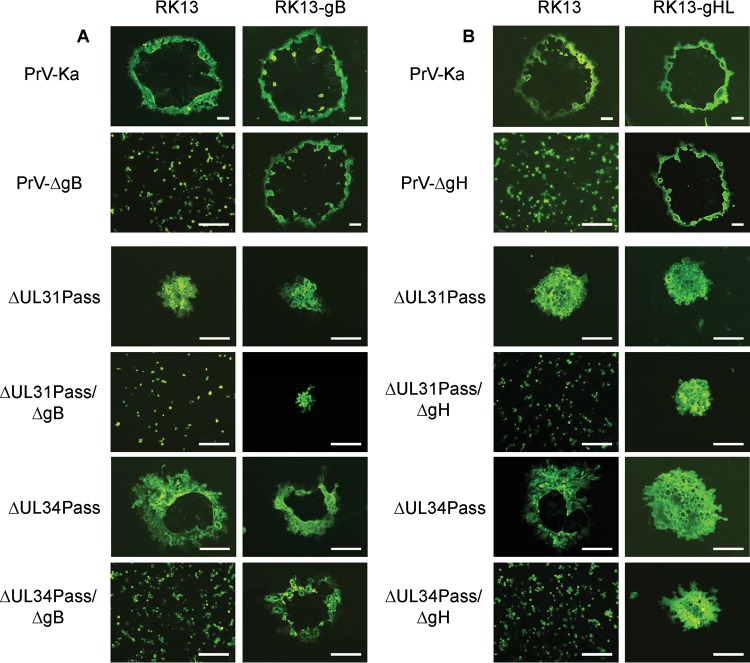

The plaques formed by PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB on RK13-gB cells were comparable in size to those formed by the parental viruses (Fig. 3). As with the passaged viruses on RK13 cells, the plaques were smaller than those formed by PrV-Ka but showed a syncytial phenotype. On RK13 cells infected with gB deletion mutants of either the passaged mutants or PrV-Ka, only single infected cells could be observed. Similar results were obtained for the gH-negative mutants. The plaques formed by PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH on RK13-gH/gL cells were phenotypically similar to those of PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass. On RK13 cells, however, again only single infected cells could be found. No fusion of infected with neighboring cells was observed with passaged mutants lacking gB or gH, indicating that also in the passaged mutants both proteins are necessary to induce membrane fusion. For unknown reasons, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB produced the smallest plaques on complementing cells, which parallels less efficient complementation by these cells in the replication analysis. However, in both assays, an effect of the transcomplementing gB was clearly visible, although not to the level of the parental virus.

Fig 3.

Plaque formation of PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass mutants deficient in gB or gH. (A) RK13 cells were infected under plaque assay conditions with 2 × 104 PFU per well of PrV-ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB. RK13-gB cells were infected with 200 PFU of PrV-Ka, PrV-ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL31Pass, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL34Pass, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB. (B) Similar conditions were used for the infection of RK13 and RK13-gH/gL cells with PrV-Ka, PrV-ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL31Pass, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass, or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH. After 2 days of incubation, the cells were fixed with ethanol and stained with antiserum against pUL19. Bars, 200 μm.

PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass mutants lacking gB or gH induce nuclear envelope breakdown.

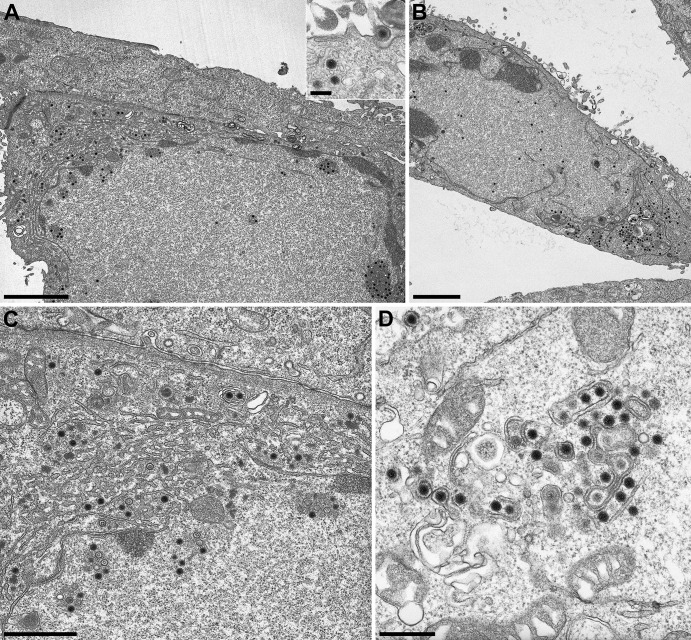

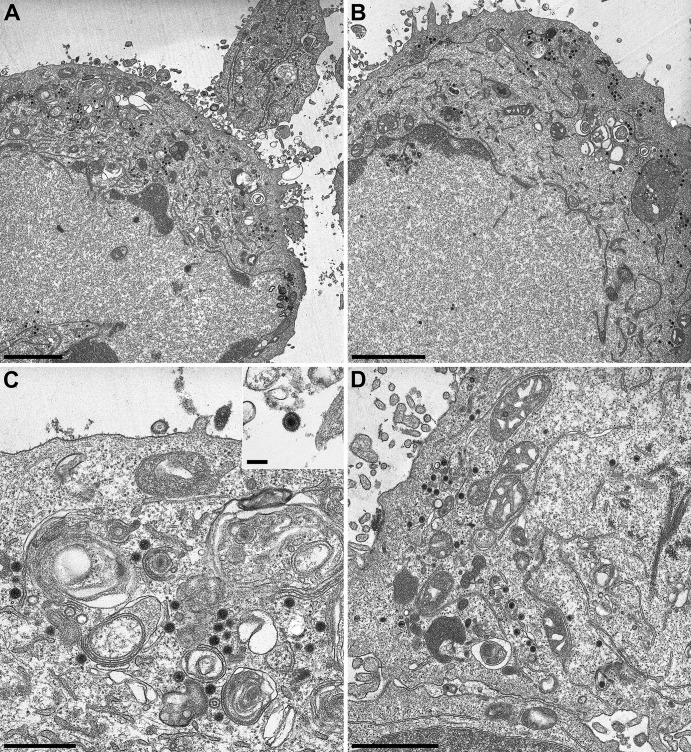

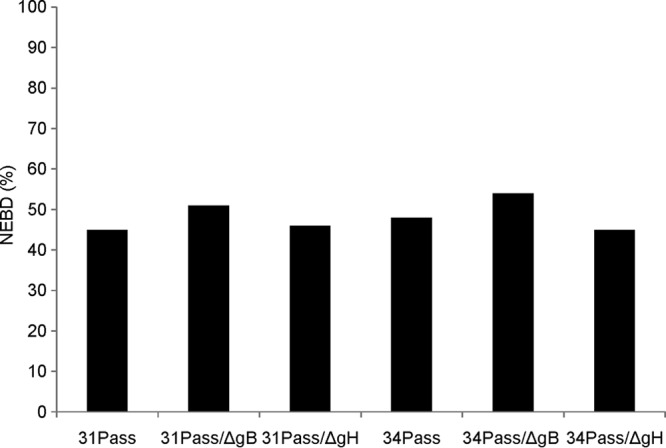

Both passaged UL31- and UL34-negative viruses induce NEBD. To determine whether gB and gH are involved in NEBD, we analyzed PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH using electron microscopy. To this end, RK13 cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB, ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH, or ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH for 16 h or at an MOI of 0.1 with ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB for 22 h and processed for ultrastructural analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, absence of gB from PrV-ΔUL31Pass did not preclude nuclear envelope fragmentation nor intracytoplasmic maturation of virion particles (Fig. 4C) and their release (Fig. 4A, inset). Similar observations were made for PrV-ΔUL34Pass lacking gB. Deletion of gH from either passaged virus also did not block NEBD (Fig. 5A and B) nor cytoplasmic virion maturation and release (Fig. 5C and D). Quantitation of nuclei showing NEBD revealed that after infection with either passaged virus, as well as with the gB- or gH-deficient mutants, a similar proportion of ca. 50% of the nuclei were ruptured (Fig. 6). Thus, NEBD occurred independently of the presence or absence of gB or gH, and nucleocapsids which gained access to the cytosol via the fragmented nuclear envelope proceeded with regular virion maturation demonstrating that the phenotype observed in the absence of gH or gB resembled that in parental PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass (13, 14). However, syncytium formation which was routinely detected in PrV-ΔUL31Pass- and PrV-ΔUL34Pass-infected cells, was abolished in the absence of either gB or gH demonstrating that the viral fusion machinery is not required for NEBD but remains essential for cell-cell fusion also in cells infected by PrV mutants inducing NEBD.

Fig 4.

Electron microscopic analysis of cells infected with gB deletion PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass mutants. RK13 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB for 22 h (A and C) or at an MOI of 1 with PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB (B and D) for 16 h and then processed for electron microscopic analysis. Bars: 2.5 μm, A and B; 1 μm, C; 500 nm, D. For the inset in panel A, the bar represents 200 nm.

Fig 5.

Electron microscopic analysis of cells infected with gH-deficient PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass mutants. RK13 cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH (A and C) or PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH (B and D) for 16 h and then processed for electron microscopic analysis. Bars: 2.5 μm, A and B; 700 nm, C; 1.4 μm, D. For the inset in panel C, the bar represents 200 nm.

Fig 6.

Quantitation of NEBD in gB- or gH-deficient mutant viruses. Approximately 70 nuclei were analyzed ultrastructurally in cells infected by the indicated virus mutants, and the percentages of nuclei exhibiting NEBD were determined.

DISCUSSION

During herpesvirus infection, nucleocapsids have to be translocated from the nucleus into the cytosol for continuing virion maturation. In wild-type virus infections, this process is mediated by the NEC triggering primary envelopment at the inner nuclear membrane, followed by de-envelopment at the outer nuclear membrane (ONM). This regulated nucleocytoplasmic vesicular transport of nucleocapsids can, however, be bypassed in the absence of the NEC by herpesvirus-induced NEBD. Although transgenic expression of both components of the NEC, pUL34 and pUL31, is sufficient for the formation and fission of vesicles from the inner nuclear membrane resembling primary envelopes (33, 34), the machinery mediating fusion of the primary envelope with the ONM is still unknown, as are the molecular details of NEBD. Since both processes involve remodeling of lipid membranes it has been postulated that the viral fusion machinery active during entry and direct viral cell-to-cell spread, which includes gB and gH, may be involved. Whereas there are indications for involvement of gB and gH in nuclear egress of HSV-1 (15), this is not the case for PrV (25).

NEBD-inducing PrV mutants lacking pUL34 or pUL31 had been passaged serially in cell culture, leading to the development of a highly syncytial phenotype (13, 14). Syncytium formation indicates a deregulation of membrane fusion. Thus, this deregulation could also exert its effects on the nuclear envelope resulting in NEBD. Since gB and gH are required for virus-induced membrane fusion during entry and direct viral cell-to-cell spread, are crucial for syncytium formation, and have been postulated as being involved in nuclear egress, we tested whether these proteins may participate in NEBD in the absence of the NEC.

Replication kinetics showed that PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB were unable to replicate productively on noncomplementing cells and that they are unable to spread from infected to noninfected cells similar to gB-negative wild-type PrV-ΔgB (27, 35, 36). The defect of PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB was complemented on RK13-gB cells, demonstrating that the mutation found in PrV-ΔUL34Pass is not involved in the observed NEC-negative phenotype. PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgB, however, replicated to ∼10-fold-lower titers compared to PrV-ΔUL31Pass, even on complementing cells. The results obtained for PrV-ΔUL31Pass/ΔgH and PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgH were similar to PrV-ΔUL34Pass/ΔgB. Both virus mutants were unable to replicate on RK13 cells, just like PrV-ΔgH, but replicated comparably to their parental viruses on RK13-gH/gL cells. These results clearly show that gB and gH are essential for viral replication also in the highly passaged NEC-negative virus mutants.

Ultrastructural analysis of gB or gH deletion passaged pUL34- or pUL31-deficient viruses showed that they are still able to induce NEBD as efficiently as the parental mutants (Fig. 4 to 6). However, in contrast to the parental virus mutants, syncytium formation was not observed. Thus, whereas the requirement for gB and gH for productive replication and fusion of plasma membranes between infected and uninfected neighboring cells is identical to that seen in wild-type PrV, neither of the proteins is required for nuclear egress via the NEC nor for nuclear escape via NEBD. In HSV-1, a double deletion of gB and gH showed the greatest effect on nuclear egress (15). We did not attempt to isolate respective double deletion mutants of our passaged viruses and thus cannot exclude that the simultaneous deletion of both essential glycoproteins would exert some effect on NEBD. However, results from the single deletions supports our suggestion that nuclear events during PrV replication are not dependent on the action of the viral entry fusion machinery.

Whole-genome sequence analysis of the genome of PrV-ΔUL34Pass revealed several mutations, including a mutation in gB, whereas the passaged UL31 deletion virus had no changes in gB (13). This already indicated that the mutation in gB might not be involved in the observed NEBD (13). This has now been proven by analysis of the gB deletion PrV-ΔUL34Pass, which is still capable of mediating NEBD.

It remains unclear how the passaged UL31- and UL34-deficient viruses induce NEBD. In noninfected cells, nuclear envelope breakdown is induced either during mitosis or apoptosis (38). HCMV can induce a process at late time points of infection, which is similar to mitosis. For this pseudomitosis, cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) plays an important role (39, 40). TorsinA is important for the maintenance of the nuclear envelope. Recently, it has been shown that overexpression of wild-type TorsinA leads to the bulging of the outer nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm, whereas the inner nuclear membrane remained undisturbed (41). TorsinA, the product of the DYT1 (TOR1A) gene, is a member of the AAA+ (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) superfamily of ATPases (42, 43). Infection of TorsinA overexpressing cells with HSV-1 not only impaired viral replication but also inhibited the de-envelopment of primary virions, resulting in their accumulation (44). When embryonic fibroblasts derived from TorsinA knockout mice were infected with HSV-1, breakdown and vesicularization of the nuclear envelope was observed. This phenotype was impaired after infection with a virus deficient in gB and gD (Richard Roller, unpublished data), indicating that these viral glycoproteins might be involved in the observed NEBD. In contrast to these results, we show here that PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass deficient in gB or gH are still able to induce nuclear envelope breakdown, pointing to a different mechanism for TorsinA-related NEBD compared to NEBD induced in the absence of the NEC.

Serial passage of herpesviruses often results in the increased formation of syncytia (45, 46). The enhanced fusogenicity correlates with mutations either in gB (45, 47–50), gK (46), or pUL20 (51). Syncytial mutations in gB were found in two conserved regions of the cytoplasmic domain. Region I is found next to the transmembrane domain and contains residues R796 to E816/817. Region II is located centrally in the cytoplasmic domain and includes residues A855 and R858 (47). The syncytial mutations in gK are mainly located in domain I, which is in the extracellular part of the protein. Additional syncytial mutations are C243, I304, and R310 (52–57). In addition to gB and gK, pUL20 is involved in virus-induced cell fusion. It has been suggested that gK and pUL20 together regulate the fusogenic capacity of gB (58, 59). However, in PrV-ΔUL34Pass no mutation was detected in gK or UL20, and the mutation found in gB, Q148R, has not been linked to syncytium formation. In PrV-ΔUL31Pass no gB mutation was detected (13). Interestingly, during serial passaging of PrV-ΔUL31Pass, a deletion of the gE-encoding gene occurred (13), which, however, apparently did not impair syncytium formation. This finding is in contrast to reports from HSV-1 and varicella-zoster virus (60, 61), possibly indicating differences in the function of the fusion apparatus between the different viruses.

In summary, we were able to show that gB and gH do not participate in virus-induced NEBD but are important for the formation of syncytia in PrV-ΔUL31Pass and PrV-ΔUL34Pass.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Meinke, M. Sell, and P. Meyer for expert technical assistance and M. Jörn for photographic help.

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Me 854/12-1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H. 2006. Herpesvirus assembly: a tale of two membranes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H. 2009. Herpesvirus assembly: an update. Virus Res. 143:222–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson DC, Baines JD. 2011. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:382–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mettenleiter TC, Müller F, Granzow H, Klupp BG. 2013. The way out: what we know and do not know about herpesvirus nuclear egress. Cell Microbiol. 15:170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter TC. 2002. The interacting UL31 and UL34 gene products of pseudorabies virus are involved in egress from the host-cell nucleus and represent components of primary enveloped but not mature virions. J. Virol. 76:364–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds AE, Ryckman BJ, Baines JD, Zhou Y, Liang L, Roller RJ. 2001. U(L)31 and U(L)34 proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1 form a complex that accumulates at the nuclear rim and is required for envelopment of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 75:8803–8817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park R, Baines JD. 2006. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces activation and recruitment of protein kinase C to the nuclear membrane and increased phosphorylation of lamin B. J. Virol. 80:494–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muranyi W, Haas J, Wagner M, Krohne G, Koszinowski UH. 2002. Cytomegalovirus recruitment of cellular kinases to dissolve the nuclear lamina. Science 297:854–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mou F, Forest T, Baines JD. 2007. US3 of herpes simplex virus type 1 encodes a promiscuous protein kinase that phosphorylates and alters localization of lamin A/C in infected cells. J. Virol. 81:6459–6470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamirally S, Kamil JP, Ndassa-Colday YM, Lin AJ, Jahng WJ, Baek MC, Noton S, Silva LA, Simpson-Holley M, Knipe DM, Golan DE, Marto JA, Coen DM. 2009. Viral mimicry of Cdc2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 mediates disruption of nuclear lamina during human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000275. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2000. Primary envelopment of pseudorabies virus at the nuclear membrane requires the UL34 gene product. J. Virol. 74:10063–10073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roller RJ, Zhou Y, Schnetzer R, Ferguson J, DeSalvo D. 2000. Herpes simplex virus type 1 U(L)34 gene product is required for viral envelopment. J. Virol. 74:117–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm KS, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Muller FM, Fuchs W, Mettenleiter TC. 2012. Analysis of viral and cellular factors influencing herpesvirus-induced nuclear envelope breakdown. J. Virol. 86:6512–6521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2011. Nuclear envelope breakdown can substitute for primary envelopment-mediated nuclear egress of herpesviruses. J. Virol. 85:8285–8292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farnsworth A, Wisner TW, Webb M, Roller R, Cohen G, Eisenberg R, Johnson DC. 2007. Herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gB and gH function in fusion between the virion envelope and the outer nuclear membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:10187–10192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heldwein EE, Lou H, Bender FC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Harrison SC. 2006. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science 313:217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanian RP, Geraghty RJ. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 mediates fusion through a hemifusion intermediate by sequential activity of glycoproteins D, H, L, and B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2903–2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JO, Longnecker R. 2010. Reevaluating herpes simplex virus hemifusion. J. Virol. 84:11814–11821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atanasiu D, Cairns TM, Whitbeck JC, Saw WT, Rao S, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. 2013. Regulation of herpes simplex virus gB-induced cell-cell fusion by mutant forms of gH/gL in the absence of gD and cellular receptors. mBio 4:e00046–13. 10.1128/mBio.00046-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atanasiu D, Whitbeck JC, Cairns TM, Reilly B, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. 2007. Bimolecular complementation reveals that glycoproteins gB and gH/gL of herpes simplex virus interact with each other during cell fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:18718–18723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wisner TW, Wright CC, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y, Mou F, Baines JD, Roller RJ, Johnson DC. 2009. Herpesvirus gB-induced fusion between the virion envelope and outer nuclear membrane during virus egress is regulated by the viral US3 kinase. J. Virol. 83:3115–3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2001. Effect of the pseudorabies virus US3 protein on nuclear membrane localization of the UL34 protein and virus egress from the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2363–2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagenaar F, Pol JM, Peeters B, Gielkens AL, de Wind N, Kimman TG. 1995. The US3-encoded protein kinase from pseudorabies virus affects egress of virions from the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt 7):1851–1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds AE, Wills EG, Roller RJ, Ryckman BJ, Baines JD. 2002. Ultrastructural localization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL31, UL34, and US3 proteins suggests specific roles in primary envelopment and egress of nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 76:8939–8952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klupp B, Altenschmidt J, Granzow H, Fuchs W, Mettenleiter TC. 2008. Glycoproteins required for entry are not necessary for egress of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 82:6299–6309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speese SD, Ashley J, Jokhi V, Nunnari J, Barria R, Li Y, Ataman B, Koon A, Chang YT, Li Q, Moore MJ, Budnik V. 2012. Nuclear envelope budding enables large ribonucleoprotein particle export during synaptic Wnt signaling. Cell 149:832–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nixdorf R, Klupp BG, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 2000. Effects of truncation of the carboxy terminus of pseudorabies virus glycoprotein B on infectivity. J. Virol. 74:7137–7145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan AS, Vatter AE. 1959. A comparison of herpes simplex and pseudorabies viruses. Virology 7:394–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brack AR, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Tirabassi R, Enquist LW, Mettenleiter TC. 2000. Role of the cytoplasmic tail of pseudorabies virus glycoprotein E in virion formation. J. Virol. 74:4004–4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopp M, Granzow H, Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Mundt E, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 2003. The pseudorabies virus UL11 protein is a virion component involved in secondary envelopment in the cytoplasm. J. Virol. 77:5339–5351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC. 1999. Glycoprotein gL-independent infectivity of pseudorabies virus is mediated by a gD-gH fusion protein. J. Virol. 73:3014–3022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mettenleiter TC. 1989. Glycoprotein gIII deletion mutants of pseudorabies virus are impaired in virus entry. Virology 171:623–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Fuchs W, Keil GM, Finke S, Mettenleiter TC. 2007. Vesicle formation from the nuclear membrane is induced by coexpression of two conserved herpesvirus proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7241–7246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai PJ, Pryce EN, Henson BW, Luitweiler EM, Cothran J. 2012. Reconstitution of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus nuclear egress complex and formation of nuclear membrane vesicles by coexpression of ORF67 and ORF69 gene products. J. Virol. 86:594–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauh I, Mettenleiter TC. 1991. Pseudorabies virus glycoproteins gII and gp50 are essential for virus penetration. J. Virol. 65:5348–5356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peeters B, de Wind N, Hooisma M, Wagenaar F, Gielkens A, Moormann R. 1992. Pseudorabies virus envelope glycoproteins gp50 and gII are essential for virus penetration, but only gII is involved in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:894–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peeters B, de Wind N, Broer R, Gielkens A, Moormann R. 1992. Glycoprotein H of pseudorabies virus is essential for entry and cell-to-cell spread of the virus. J. Virol. 66:3888–3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buendia B, Courvalin JC, Collas P. 2001. Dynamics of the nuclear envelope at mitosis and during apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58:1781–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hertel L, Chou S, Mocarski ES. 2007. Viral and cell cycle-regulated kinases in cytomegalovirus-induced pseudomitosis and replication. PLoS Pathog. 3:e6. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hertel L, Mocarski ES. 2004. Global analysis of host cell gene expression late during cytomegalovirus infection reveals extensive dysregulation of cell cycle gene expression and induction of pseudomitosis independent of US28 function. J. Virol. 78:11988–12011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grundmann K, Reischmann B, Vanhoutte G, Hubener J, Teismann P, Hauser TK, Bonin M, Wilbertz J, Horn S, Nguyen HP, Kuhn M, Chanarat S, Wolburg H, Van der Linden A, Riess O. 2007. Overexpression of human wild-type torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol. Dis. 27:190–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozelius LJ, Hewett JW, Page CE, Bressman SB, Kramer PL, Shalish C, de Leon D, Brin MF, Raymond D, Corey DP, Fahn S, Risch NJ, Buckler AJ, Gusella JF, Breakefield XO. 1997. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat. Genet. 17:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White SR, Lauring B. 2007. AAA+ ATPases: achieving diversity of function with conserved machinery. Traffic 8:1657–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maric M, Shao J, Ryan RJ, Wong CS, Gonzalez-Alegre P, Roller RJ. 2011. A functional role for TorsinA in herpes simplex virus 1 nuclear egress. J. Virol. 85:9667–9679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamiak B, Ekblad M, Bergström T, Ferro V, Trybala E. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein G is targeted by the sulfated oligo- and polysaccharide inhibitors of virus attachment to cells. J. Virol. 81:13424–13434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pertel PE, Spear PG. 1996. Modified entry and syncytium formation by herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants selected for resistance to heparin inhibition. Virology 226:22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gage PJ, Levine M, Glorioso JC. 1993. Syncytium-inducing mutations localize to two discrete regions within the cytoplasmic domain of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 67:2191–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bzik DJ, Fox BA, DeLuca NA, Person S. 1984. Nucleotide sequence of a region of the herpes simplex virus type 1 gB glycoprotein gene: mutations affecting rate of virus entry and cell fusion. Virology 137:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baghian A, Huang L, Newman S, Jayachandra S, Kousoulas KG. 1993. Truncation of the carboxy-terminal 28 amino acids of glycoprotein B specified by herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant amb1511-7 causes extensive cell fusion. J. Virol. 67:2396–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai WH, Gu B, Person S. 1988. Role of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus type 1 in viral entry and cell fusion. J. Virol. 62:2596–2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spear PG. 1993. Membrane fusion induced by herpes simplex virus, p 201–232 In Bentz J. (ed), Viral fusion mechanisms. CRC Press Inc, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foster TP, Alvarez X, Kousoulas KG. 2003. Plasma membrane topology of syncytial domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein K (gK): the UL20 protein enables cell surface localization of gK but not gK-mediated cell-to-cell fusion. J. Virol. 77:499–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Debroy C, Pederson N, Person S. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of a herpes simplex virus type 1 gene that causes cell fusion. Virology 145:36–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pogue-Geile KL, Spear PG. 1987. The single base pair substitution responsible for the Syn phenotype of herpes simplex virus type 1, strain MP. Virology 157:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bond VC, Person S. 1984. Fine structure physical map locations of alterations that affect cell fusion in herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 132:368–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pogue-Geile KL, Lee GT, Shapira SK, Spear PG. 1984. Fine mapping of mutations in the fusion-inducing MP strain of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 136:100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruyechan WT, Morse LS, Knipe DM, Roizman B. 1979. Molecular genetics of herpes simplex virus. II. Mapping of the major viral glycoproteins and of the genetic loci specifying the social behavior of infected cells. J. Virol. 29:677–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melancon JM, Luna RE, Foster TP, Kousoulas KG. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 gK is required for gB-mediated virus-induced cell fusion, while neither gB and gK nor gB and UL20p function redundantly in virion de-envelopment. J. Virol. 79:299–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foster TP, Melancon JM, Baines JD, Kousoulas KG. 2004. The herpes simplex virus type 1 UL20 protein modulates membrane fusion events during cytoplasmic virion morphogenesis and virus-induced cell fusion. J. Virol. 78:5347–5357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balan P, Davis-Poynter N, Bell S, Atkinson H, Browne H, Minson T. 1994. An analysis of the in vitro and in vivo phenotypes of mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 lacking glycoproteins gG, gE, gI, or the putative gJ. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1245–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cole NL, Grose C. 2003. Membrane fusion mediated by herpesvirus glycoproteins: the paradigm of varicella-zoster virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 13:207–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]