Abstract

The paramyxovirus pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) is a rodent model of human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) pathogenesis. Here we characterized the PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell repertoire in susceptible C57BL/6 mice. In total, 15 PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes restricted by H-2Db and/or H-2Kb were identified. These data open the door for using widely profiled, genetically manipulated C57BL/6 mice to study the contribution of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells to PVM pathogenesis.

TEXT

Pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) is an enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus that belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family (1, 2). PVM, a natural rodent pathogen, is used as an animal model for the study of human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV). PVM and hRSV elicit a robust respiratory infection, have similar clinical as well as pathological features, and induce release of an abundance of specific cytokines (cytokine storm) which correlates directly with disease severity in hosts infected with either virus (3–8). hRSV is one of the leading causes of death in children under the age of 5 years, resulting in as many as 199,000 deaths worldwide (9). Because hRSV replicates poorly in mice, i.e., a large inoculum (>106) of virus is required to establish a detectable infection, it is unclear if hRSV inoculation of mice accurately recapitulates the pathogenesis of hRSV infection (10). Therefore, PVM infection is a desirable model for detailed investigation of paramyxovirus infection within its natural host and the immunologic consequences.

CD8+ T cells have been reported to play a prominent role in eradicating hRSV and PVM infections but have also been shown to elicit intense immune-mediated disease (11–16). However, such studies of PVM- and epitope-specific cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity have been primarily restricted to mice bred on the H-2d BALB/c background, thus limiting the use of the plentiful gene knockout and knock-in models available primarily on the H-2b background (17). Here, we report initial evidence for PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes within C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice. These data provide an improved platform to study CD8+ T-cell responses in genetically engineered mice on the H-2b background.

The amino acid sequence of the PVM strain 15 proteome (18) was analyzed for H-2 major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding capacity using the previously described ANN and SMM algorithms (19) available from the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) (http://www.iedb.org/) (PMID 19906713). Predictions were retrieved in February 2012. A set of 176 peptides that scored in the top 1% range for each allele/size for H-2Db (9- and 10-mers) and H-2Kb (8- and 9-mers) were selected and synthesized by Synthetic Biomolecules (San Diego, CA) for further analysis. The 1% threshold was selected based on previous data demonstrating that this threshold is sufficient to identify the vast majority of the H-2b class I-restricted response (19).

Ten C57BL/6 mice were either mock infected or infected with 1.5 ×103 PFU of recombinant PVM (rPVM) strain 15, kindly provided to us by Peter L. Collins (20). On day 8 after infection, lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) were harvested and pooled; single-cell suspensions were then generated using collagenase D enzymatic digestion of lung tissue and mechanical disruption (21). Single cells were plated at a concentration of 8 ×105 cells per well in a 96-well round bottom plate with 1 μg/ml of individual, algorithm-predicted PVM peptides and incubated in the presence of brefeldin A (4 μg/ml) for 5 h. The cells were then surface stained for CD8a as well as Thy1.2, fixed, reversibly perforated with saponin (2%), stained intracellularly for gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and evaluated by flow cytometric analysis. Exposure of PVM-challenged CD8+ T cells to 15 of the selected peptides induced production of IFN-γ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of PVM epitopes recognized by CD8+ T cells from PVM-challenged C57BL/6 mice

| Sequence | Proteina | Position | Predicted allele | Fold increase in IFN-γ+b |

IC50 (nM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | MLN | H-2Db | H-2Kb | ||||

| GAPRNRELF | N | 339 | Db | 4.38 | 5.88 | 51 | 9,386 |

| CSFHNRVTL | M | 146 | Db | 3.18 | 3.29 | 525 | 2,772 |

| AGLDNKFYL | G | 299 | Db | 2.26 | 4.21 | 660 | 6,222 |

| LSSVNADTL | F | 254 | Db | 3.58 | 3.21 | 126 | 12,621 |

| RVVVNQDYL | L | 545 | Db | 3.94 | 1.93 | 75 | 4,171 |

| SSVANIDSL | L | 1234 | Db | 4.34 | 2.05 | 643 | 1,337 |

| LTVFNFAYL | L | 1480 | Db | 2.91 | 2.24 | 118 | 6.6 |

| INWNFIRI | NS2 | 65 | Db | 2.58 | 1.93 | 32,297 | 51 |

| INYSALNL | N | 363 | Kb | 2.92 | 3.79 | 15,281 | 82 |

| CSFHNRVTL | M | 146 | Kb | 2.47 | 2.81 | 414 | 392 |

| AVIRFQQL | F | 184 | Kb | 2.10 | 2.45 | 53 | |

| FSTRFYNNM | L | 302 | Kb | 4.49 | 1.83 | 60 | |

| VSPVYPHGL | L | 1052 | Kb | 5.73 | 5.69 | 37,000 | 3.1 |

| LTVFNFAYL | L | 1480 | Kb | 2.08 | 1.90 | 721 | 62 |

| MSYDYPKM | L | 1623 | Kb | 2.55 | 3.45 | 14 | |

PVM proteins: nucleoprotein (N), matrix protein (M), attachment glycoprotein (G), fusion glycoprotein precursor (F), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L), nonstructural protein 2 (NS2).

Fold increase values were determined by calculating the numbers of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells following PVM-peptide exposure/IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells following pulse with an irrelevant peptide.

Using a previously described methodology (22), the identified epitopes were tested for their capacity to bind purified H-2Db and H-2Kb. Each epitope was found to have the capacity to bind the corresponding predicted MHC class I allele with high or intermediate affinity, with inhibition of labeled peptide binding by 50% (IC50) of 51 to 660 nM and <0.5 to 392 nM for H-2Db and H-2Kb, respectively (Table 1). Considering both the predicted and measured Db and Kb binding data, it appears that each molecule is the putative restriction element for seven and six epitopes, respectively. In addition, the L1480–1488 epitope is potentially restricted by both H-2b class I molecules.

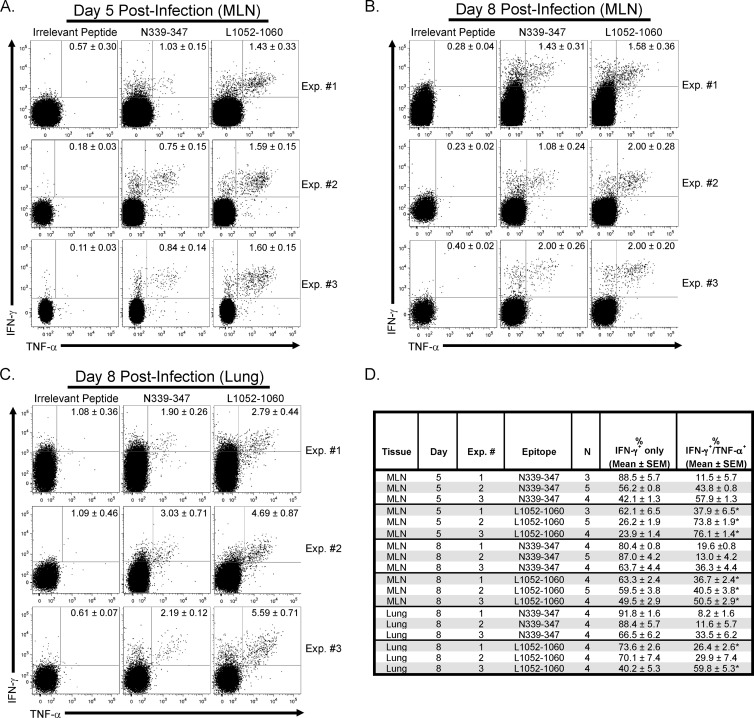

Two of the epitopes that induced the greatest IFN-γ production by PVM-challenged CD8+ T cells, PVM nucleoprotein (N)339–347 and polymerase (L)1052–1060, were subjected to peptide stimulation, enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay, and chromium release assay. Three to five C57BL/6 mice were euthanized on days 5 and 8 postinfection with 3 × 103 PFU of rPVM strain 15. Single-cell suspensions from the MLN and lung were subjected to the N339–347 and L1052–1060 peptide stimulations as described above. IFN-γ-positive (IFN-γ+) CD8+ T cells were not detected above background in the lung at day 5 after infection (data not shown). However, N339–347 and L1052–1060 peptide stimulation produced significantly greater frequencies of IFN-γ+ tumor necrosis factor alpha-negative (TNF-α−) CD8+ T cells as well as IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells in the MLN on days 5 (Fig. 1A and D) and 8 (Fig. 1B and D) postinfection, and in the lung on day 8 (Fig. 1C and D) after infection, compared to irrelevant peptide-pulsed cells. Further, in three separate experiments, L1052–1060 peptide stimulation yielded significantly (P < 0.05) greater percentages of IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells from the MLN (day 5 and 8) and lung (day 8; 2 of 3 experiments) judged against cells stimulated with N339–347 peptide (Fig. 1D); therefore, L1052–1060-specific cells exhibited greater antiviral cytokine secreting potential.

Fig 1.

Ex vivo evaluation of N339–347 and L1052–1060 PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell cytokine production. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 3 × 103 PFU of rPVM strain 15. Lung was harvested on day 8, and MLN was removed on days 5 and 8. Single-cell suspensions were generated from lung by collagenase D digestion (2 mg/ml, 30 min at 37°C with agitation) and mechanical disruption, while MLN were subjected to mechanical disruption only. Single-cell suspensions were incubated in the presence of irrelevant, N339–347 or L1052–1060 peptide (1 μg/ml) and brefeldin A (4 μg/ml) for 5 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. CD8+ T cells were evaluated for IFN-γ and TNF-α positivity by intracellular cytokine staining. (A to C) Representative dot plots of gated CD8+ T cells (Thy1.2+, CD8+, CD4−) from three individual experiments (Exp.) from the MLN on day 5 (A), MLN on day 8 (B), and the lung on day 8 postinfection (C). All gated cells within the representative dot plots depict total IFN-γ+ cell numbers. Numbers within the representative dot plots depict the average ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the results from the experimental group stimulated by the specified peptide for that individual experiment. (D) Summary of the data from three separate experiments from both the MLN (days 5 and 8 after infection) and lung (day 8 postinfection), including the frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells positive for IFN-γ only and showing IFN-γ/TNF-α dual positivity. Data represent a total of 3 to 5 mice per group for each tissue for the three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 (compared to the frequency of IFN-γ/TNF-α dual-secreting N339–347-stimulated CD8+ T cells).

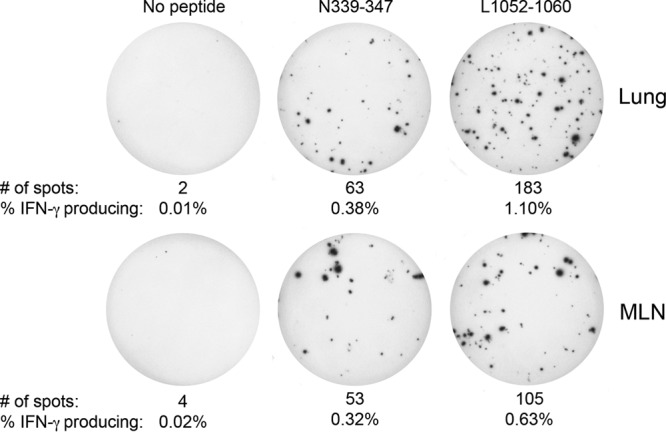

Subsequently, CD8+ T cells were purified from the lung and MLN of seven PVM-infected mice on day 8 postinfection. These purified CD8+ T cells were cocultured with purified antigen-presenting cells (APCs) from the spleens of naive C57BL/6 mice. Cocultures were incubated without peptide, or in the presence of 1 μg/ml of either N339–347 or L1052–1060 PVM-specific peptides, and subjected to an IFN-γ-specific ELISpot assay (BD Pharmingen). IFN-γ immunopositivity was detected in both the lung and MLN after N339–347 and L1052–1060 peptide stimulation, while cells cultured in the absence of peptide yielded few spot-forming cells (Fig. 2). In addition, as observed in the peptide stimulation assay, in the MLN on day 5 and in the lung on day 8, greater frequencies of IFN-γ-producing cells were detected following L1052–1060 peptide stimulation than were detected with N339–347 peptide-exposed cells (Fig. 2). Lastly, three separate lung single-cell suspensions derived from pooled samples from three PVM-infected C57BL/6 mice exhibited functional cytotoxic activity against 51Cr-labeled MC57 cells incubated with either L1052–1060 or N339–347 peptide but similar MC57 cells incubated with irrelevant peptide at effector/target ratios of 25:1 and 12.5:1 did not (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Detection of N339–347 and L1052–1060 PVM-specific CD8+ T cells by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Seven C57BL/6 mice were infected with 3 × 103 PFU of rPVM strain 15 and euthanized on day 8 postinfection. The MLNs and lungs from infected mice were pooled and processed into a single-cell suspension as mentioned above, and CD8+ T cells were isolated to >96% purity using a CD8+ T-cell negative-selection kit (StemCell Technologies). Purified CD8+ T cells were cocultured with splenic APCs isolated to >94% purity from naive C57BL/6 mice using an EasySep Mouse APC Positive Selection kit (StemCell Technologies). CD8+ T cells and APCs were cultured at a ratio of 1:1 (5 × 104 CD8+ T cells to 5 × 104 APCs), and the CD8+ T-cell input was subjected to five 3-fold, serial dilutions while the number of APCs remained constant (5 × 104 APCs/well). Cocultures were supplemented without peptide or in the presence of N339–347 or L1052–1060 peptides in the 96-well plate provided (IFN-γ ELISpot kit; BD Pharmingen). Cocultures were incubated for 18 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Wells shown represent the second serial dilution (16.7 CD8+ T cells to 5 × 104 APCs). Numbers of spots and frequencies of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells are listed.

In summary, we successfully identified PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes within H-2b C57BL/6 mice. Comparisons between PVM-specific peptides L1052–1060 and N339–347 revealed that the former induced a greater CD8+ T-cell antiviral cytokine response. Documenting PVM-specific CD8+ T-cell epitope responses in conjunction with genetically modified mice should facilitate efforts to expand our knowledge about the role of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the pathogenetic effects of immunity operative in hRSV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is publication number 21853 from the Department of Immunology and Microbial Science, The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI).

This work was supported in part by USPHS grants AI074564 (M.B.A.O., K.B.W.) and AI009484 (M.B.A.O.), NIH NIAID contract HHSN272200900042C (J.S., A.S.), and NIH training grants NS041219 (K.B.W.) and AI007244 (K.B.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Compans RW, Harter DH, Choppin PW. 1967. Studies on pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) in cell culture. II. Structure and morphogenesis of the virus particle. J. Exp. Med. 126:267–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harter DH, Choppin PW. 1967. Studies on pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) in cell culture. I. Replication in baby hamster kidney cells and properties of the virus. J. Exp. Med. 126:251–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Dyer KD, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. 2000. Pulmonary eosinophilia and production of MIP-1alpha are prominent responses to infection with pneumonia virus of mice. Cell Immunol. 200:98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Gao JL, Murphy PM, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. 2000. The chemokine macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha and its receptor CCR1 control pulmonary inflammation and antiviral host defense in paramyxovirus infection. J. Immunol. 165:2677–2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garofalo R, Kimpen JL, Welliver RC, Ogra PL. 1992. Eosinophil degranulation in the respiratory tract during naturally acquired respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Pediatr. 120:28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garofalo RP, Patti J, Hintz KA, Hill V, Ogra PL, Welliver RC. 2001. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha (not T helper type 2 cytokines) is associated with severe forms of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 184:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison AM, Bonville CA, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. 1999. Respiratory syncytical virus-induced chemokine expression in the lower airways: eosinophil recruitment and degranulation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159:1918–1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. 2008. Pneumonia virus of mice: severe respiratory infection in a natural host. Immunol. Lett. 118:6–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins PL, Melero JA. 2011. Progress in understanding and controlling respiratory syncytial virus: still crazy after all these years. Virus Res. 162:80–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bem RA, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. 2011. Animal models of human respiratory syncytial virus disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 301:L148–L156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon MJ, Openshaw PJ, Askonas BA. 1988. Cytotoxic T cells clear virus but augment lung pathology in mice infected with respiratory syncytial virus. J. Exp. Med. 168:1163–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Saleeby CM, Suzich J, Conley ME, DeVincenzo JP. 2004. Quantitative effects of palivizumab and donor-derived T cells on chronic respiratory syncytial virus infection, lung disease, and fusion glycoprotein amino acid sequences in a patient before and after bone marrow transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:e17–e20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey S, Krempl CD, Schmitt-Graff A, Ehl S. 2008. Role of T cells in virus control and disease after infection with pneumonia virus of mice. J. Virol. 82:11619–11627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham BS, Bunton LA, Wright PF, Karzon DT. 1991. Role of T lymphocyte subsets in the pathogenesis of primary infection and rechallenge with respiratory syncytial virus in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 88:1026–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostler T, Davidson W, Ehl S. 2002. Virus clearance and immunopathology by CD8(+) T cells during infection with respiratory syncytial virus are mediated by IFN-gamma. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:2117–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srikiatkhachorn A, Braciale TJ. 1997. Virus-specific memory and effector T lymphocytes exhibit different cytokine responses to antigens during experimental murine respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Virol. 71:678–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claassen EA, van der Kant PA, Rychnavska ZS, van Bleek GM, Easton AJ, van der Most RG. 2005. Activation and inactivation of antiviral CD8 T cell responses during murine pneumovirus infection. J. Immunol. 175:6597–6604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krempl CD, Lamirande EW, Collins PL. 2005. Complete sequence of the RNA genome of pneumonia virus of mice (PVM). Virus Genes 30:237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moutaftsi M, Peters B, Pasquetto V, Tscharke DC, Sidney J, Bui HH, Grey H, Sette A. 2006. A consensus epitope prediction approach identifies the breadth of murine T(CD8+)-cell responses to vaccinia virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:817–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krempl CD, Wnekowicz A, Lamirande EW, Nayebagha G, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. 2007. Identification of a novel virulence factor in recombinant pneumonia virus of mice. J. Virol. 81:9490–9501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh KB, Teijaro JR, Wilker PR, Jatzek A, Fremgen DM, Das SC, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Shinya K, Suresh M, Kawaoka Y, Rosen H, Oldstone MB. 2011. Suppression of cytokine storm with a sphingosine analog provides protection against pathogenic influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:12018–12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidney J, Southwood S, Oseroff C, del Guercio MF, Sette A, Grey HM. 2001. Measurement of MHC/peptide interactions by gel filtration. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 18Unit 18.3. 10.1002/0471142735.im1803s31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]