Abstract

In most forms of prion disease, infectivity is present primarily in the central nervous system or immune system organs such as spleen and lymph node. However, a transgenic mouse model of prion disease has demonstrated that prion infectivity can also be present as amyloid deposits in heart tissue. Deposition of infectious prions as amyloid in human heart tissue would be a significant public health concern. Although abnormal disease-associated prion protein (PrPSc) has not been detected in heart tissue from several amyloid heart disease patients, it has been observed in the heart tissue of a patient with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (sCJD), the most common form of human prion disease. In order to determine whether prion infectivity can be found in heart tissue, we have inoculated formaldehyde fixed brain and heart tissue from two sCJD patients, as well as prion protein positive fixed heart tissue from two amyloid heart disease patients, into transgenic mice overexpressing the human prion protein. Although the sCJD brain samples led to clinical or subclinical prion infection and deposition of PrPSc in the brain, none of the inoculated heart samples resulted in disease or the accumulation of PrPSc. Thus, our results suggest that prion infectivity is not likely present in cardiac tissue from sCJD or amyloid heart disease patients.

INTRODUCTION

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) or prion diseases are a group of rare, fatal, and infectious neurodegenerative diseases that include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle (BSE), and sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) in humans. The conversion of the soluble and normally protease-sensitive host prion protein (PrPC) into a highly aggregated and protease-resistant form, PrPSc, is a central event in prion pathogenesis and PrPSc is the primary component of the infectious prion. In humans, prions may be acquired by ingestion or inoculation of prion-contaminated materials, by exposure to prion-contaminated surgical instruments or via transplantation of tissues that can harbor prion infectivity. In the latter instance, cornea, dura mater, and cadaver-derived human growth hormone have transmitted sCJD (1), while variant CJD (vCJD), which is linked to exposure to BSE (2), has been transmitted via blood (3, 4) and blood products (5). Thus, from a public health perspective, it is critical to understand which tissues harbor infectivity for each type of prion disease in order to prevent accidental transmission of prions via inoculation, transplantation, or prion-contaminated medical instruments.

PrPC is expressed in almost every tissue in the body and can be found at high levels in several organs such as the brain, heart, and spleen (6, 7). Although theoretically PrPSc could accumulate in any tissue that expresses PrPC, its distribution can vary. For example, PrPSc in human vCJD is found not only in the brain and spinal cord but also in the spleen, tonsils, and peripheral lymph nodes (8, 9). In the most common form of human prion disease, sCJD, PrPSc is detected in central nervous system (CNS) tissues (9–11) and occasionally in other tissues such as skeletal muscle (12–14). Since the distribution of PrPSc varies depending upon the type of prion disease, the risk of transmission of prion infectivity from peripheral (i.e., non-CNS) tissues has to be determined experimentally for each prion disease type.

Humans expressing PrP molecules without the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) cell membrane anchor accumulate abnormal PrP amyloid in the brain and develop a form of prion disease (15). After infection with mouse scrapie, transgenic mice expressing mouse prion protein without the GPI membrane anchor not only develop a prion disease due to accumulation of PrP amyloid in the brain (16) and other tissues (17) but also develop an infectious cardiac amyloidosis with high levels of PrPSc and infectivity in the heart (18). These data raised the possibility not only that PrPSc might be deposited in the heart of individuals with prion disease but also that abnormal forms of PrP could be an unrecognized component of amyloid heart disease in humans (19). Consistent with this possibility, PrPSc has been reported in the heart of one sCJD patient (20), in muscle tissue (including heart) of BSE-infected nonhuman primates (21), in a BSE-infected macaque with a prion-amyloid cardiomyopathy (22), and in several chronic wasting disease models (23, 24). In contrast, several studies have failed to detect PrPSc in either sCJD heart tissue (9, 12, 19) or human amyloid hearts (19), and heart tissue from several sCJD patients did not transmit disease to nonhuman primates (25).

However, prion infectivity can be present in a tissue even in the absence of detectable PrPSc. For example, in both wild-type mouse models of BSE (26) and transgenic mouse models of prion infection (27–29), significant infectivity can be detected in brain material that is negative for PrPSc by both immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry. Similarly, even though PrPSc is restricted primarily to tissues of the CNS in sCJD (9–11), transmission studies in nonhuman primates occasionally detected infectivity in PrPSc-negative tissues such as lung, liver, and kidney (25). The occasional detection of prion infectivity in non-CNS tissue in sCJD could be the consequence of a low titer of infectivity in the tissue and/or a barrier to prion infection between human and nonhuman primates, either of which could decrease the efficiency of prion transmission across species. Species barriers in prion diseases are defined by extremely long incubation times at first passage compared to incubation times at later passages (30, 31). They are strongly influenced by the sequence of host PrPC and can be overcome using transgenic mice expressing PrPC with the same amino acid sequence as PrPSc (32).

In order to determine whether prion infectivity is present in human heart tissue, we have inoculated archival formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded brain and heart tissue from two sCJD patients, as well as PrP-positive heart samples from two amyloid heart disease patients, into transgenic mice overexpressing human prion protein. These mice have no significant species barrier to infection with the most common form of sCJD. Our results show that although both brain samples triggered a prion infection, neither clinical nor subclinical prion infection occurred in mice inoculated with any of the heart tissue samples. Although the samples we tested are limited, our data suggest that prion infectivity is not likely present in either sCJD heart or PrP-positive amyloid heart tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

The anti-hamster PrP monoclonal antibody 3F4 has been described previously (33) and recognizes an epitope encompassing amino acid residues 109 to 112 present in both hamster and human PrP (34). The 3F4 antibody was made in-house at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories from the tissue culture supernatant of hybridoma cells.

PV30 denotes an affinity-improved variant of the recombinant anti-PrP antibody P that recognizes a peptide epitope composed of PrP residues 96 to 105 (35). Regions of the parental antibody P sequence were randomized using an overlap PCR methodology employing an NNS doping strategy (36). Two independent mouse antibody-phage display libraries were constructed. In the first, a total of six residues within the first and third light-chain-complementary-determining regions (CDR1 and CRD3, respectively) were targeted for mutagenesis. In the second, four residues within the heavy-chain CDR3 were randomized. The two resulting libraries contained an average of 5 × 108 variants. Phage library selection was carried out in solution against synthetic biotinylated bovine and human PrP (residues 90 to 145). Using this strategy, over 30 different variants of the parental P antibody with improved kinetic constants were recovered. Of this number, Fab clone PV30 demonstrated an 88-fold improvement in binding kinetics for human PrP 23-231 when measured against the parental P antibody using surface plasmon resonance (Kd = 0.18 ± 0.07 nM for PV30, versus 16.61 ± 0.1 nM for antibody P).

Tissue samples.

For all tissues and homogenates studied, the superscript “FFPE” is used to denote material derived from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue while the superscript “Froz” is used to denote material derived from frozen tissue.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded brain and heart tissue from patients diagnosed with CJD in 1979 (CJD1FFPE) and 1981 (CJD2FFPE), as well as heart tissue from two amyloid heart disease patients (AHD1FFPE and AHD2FFPE), were obtained from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Additional FFPE amyloid diseased hearts were obtained from individual cases from repositories at the University of California, San Francisco, CA (Stephen DeArmond), the VA Medical Center, La Jolla, CA (Paul Wolf), the Amyloid Research Center at the Royal Free and University College Medical School, London, United Kingdom (Mark Pepys), and the Department of Repository and Research Services, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC (Sherman A. McCall). Normal heart (NHt1FFPE and NHt2FFPE, left ventricle) and normal brain (NBr1FFPE, cerebral cortex) tissue were kindly provided by Gerald Bordin, Department of Pathology, Scripps Green Hospital, La Jolla, CA.

Prnp genotype.

DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue using the Puregene DNA purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted DNA was amplified by PCR, and the product was digested with the restriction endonuclease NspI (New England BioLabs) as described earlier (37). The size of the NspI digestion product differs depending upon whether there is a codon for methionine or valine at amino acid position 129. Using DNA extracted from FFPE tissue sections, we were able to determine the Prnp genotype of AHD2FFPE as homozygous for methionine at codon 129 but have as yet been unable to clearly determine the genotype of the samples CJD1FFPE, CJD2FFPE, and AHD1FFPE.

Mouse lines and prion isolates.

The transgenic mouse lines overexpressing human PrPC (Tg66) and hamster PrPC (Tg7) have been described previously (38, 39). The control sCJD stock brain homogenate was derived from a frozen brain sample of sCJD MM type 1 from a patient homozygous for methionine at codon 129 in PrP (CJDFroz) and was kindly provided by Robert Rohwer (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD). The CJDFroz stock had a titer in Tg66 mice after intracranial (i.c.) inoculation of 2 × 105.5 ID50/g of brain (ID50 is the dose at which 50% of the animals become infected). The stock frozen brain homogenate of the hamster-adapted scrapie strain 263K (263KFroz) had an i.c. titer of 2 × 109.3 ID50/g of brain.

Inoculation of FFPE scrapie-infected transgenic mouse brain.

All animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Rocky Mountain Laboratories Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol 2007-10). The Rocky Mountain Laboratories are fully accredited by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care, and this study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

A frozen brain from Tg7 mice that had been i.c. inoculated with hamster 263KFroz scrapie was fixed for 4 days in formalin and then paraffin embedded. The FFPE brain was stabbed with a 271/2 gauge needle four times for ∼10 s per stab in order to coat the needle with infected brain material. The needle was then used to inoculate Tg7 mice i.c., and the mice monitored for scrapie. After the needle stabs, the same block was heated to remove the tissue from the paraffin and the tissue incubated in Pro-par clearant (Anatech, Ltd.) overnight at room temperature, followed by additional 2- and 1-h incubations in Pro-par the following day. The brain was rehydrated by rinsing in decreasing amounts of ethanol (100, 95, 80, 70, and 50%) for 30 min for each rinse. The brain material was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to give a final 20% (wt/vol) solution. The homogenate was vortexed, sonicated for 5 min, diluted 1:1 in 0.64 M sucrose, and centrifuged for 1 min at 1,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and diluted 1:10 in PBS–2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and then 50 μl was inoculated i.c. into Tg7 mice, which were subsequently monitored for disease.

Preparation of human FFPE brain tissue was similar to that for the Tg7 brain with the following minor modifications. The rehydrated tissue, which ranged in weight from 20 to 201 mg, was homogenized in PBS–0.16 M sucrose to give a final 10% (wt/vol) solution. This solution was vortexed, sonicated for 5 min and centrifuged for 1 min at 1,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and diluted 1:10 in PBS–2% FBS and then 50 μl was inoculated i.c. into Tg66 mice. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded human heart tissue was processed in the same way except that, due to the small amount of tissue available, the solution was not centrifuged prior to inoculation.

Human tissue immunohistochemistry.

Normal and sCJD human brain and heart tissue sections were deparaffinized in Pro-Par clearant, followed by rehydration in decreasing amounts of ethanol. The slides were rinsed in distilled water and treated with formic acid (99%) for 10 min, followed by a 5-min rinse in double-distilled water. Slides were immersed in 1 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0), placed in a Biocare decloaking chamber, and treated at 120°C and at 20 lb/in2 for 20 min. After cooling, slides were stained using an automated Ventana Nexus Stainer (Ventana Medical Systems). The primary antibody was the mouse monoclonal anti-PrP antibody 3F4, which was added to the slides undiluted for 30 min. The secondary antibody was biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:250 in 1% normal goat serum (30 min), followed by a 1:3 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Biogenex) for 30 min. The chromogen used for development was Ventana AEC (Ventana Medical Systems). Control slides without primary antibody incubation were used as specificity controls.

Human amyloid heart tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in decreasing amounts of ethanol. For sections not treated with proteinase K (PK), antigen retrieval was carried out in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at 100°C for a total of 100 min. Slides were incubated for 2 h in a 1:200 dilution of the anti-PrP antibody PV30, followed by a 30-min incubation with a 1:250 dilution of biotinylated anti-human IgG (Jackson Laboratories). Slides were processed using an automated Discovery XT staining system (Ventana Medical Systems).

Human amyloid heart tissue sections that were processed for PK digestion were deparaffinized, washed in water, and then incubated in 88% formic acid for 30 min, followed by another water wash. Sections were treated with 25 μg of PK/ml for 10 min at 26°C, rinsed in water, and hydrolytically autoclaved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 15 min. The primary antibody was either the anti-PrP antibody PV30 at a dilution of 1:400 in 5% dried milk for 1 h at room temperature (50 μl/slide) or preabsorbed PV30. For preabsorbed antibody, PV30 (1 mg/ml) was mixed with 5 mg of a biotinylated PrP peptide derived from amino acids 89 to 112 that contains the PV30 epitope. The solution was incubated with mixing for 1 h at 4°C, followed by 3 h at 37°C with occasional stirring. After a 4,000 rpm spin to remove any precipitate, the supernatant was passed over an avidin column, and the pass-through was collected. This was concentrated to the original starting volume, and 50 μl was used per slide.

Slides were stained with Thioflavin S (ThioS) using a 1% solution of ThioS in distilled water. Slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in decreasing amounts of ethanol (100, 95, and 70%) using three 5-min washes for each solution. After a distilled water rinse, sections were incubated in 1% ThioS for 5 min, followed by three 5-min washes in 80% ethanol and one brief rinse in distilled water. Coverslips were affixed using Prolong Gold with or without DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen).

Tg66 brain tissue immunohistochemistry.

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded Tg66 brain tissue was deparaffinized in Pro-Par clearant, followed by rehydration in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Slides were immersed in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0), placed in a Biocare decloaking chamber, and treated at 120°C and at 20 lb/in2 for 20 min. After cooling, the slides were stained using an automated Discovery XT staining system (Ventana Medical Systems). The primary antibody was biotinylated 3F4 (Covance) diluted 1:50 in Ventana antibody dilution buffer (Ventana Medical Systems). After a 60-min incubation, the slides were rinsed and developed using a DAB Map XT detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems).

Western blotting.

Brains from Tg66 mice were homogenized in PBS to give a final 20% (wt/vol) solution. Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), sodium deoxycholate, and Triton X-100 were added to the homogenate to give final concentrations of 0.1 M, 1%, and 1%, respectively. PK was then added to a final concentration of 63.3 μg/ml, and the reaction was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Protease activity was inhibited by the addition of 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride to a final concentration of 0.01 M, a volume of 2× sample loading buffer (1 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 6 mM EDTA, 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.04% bromophenol blue) equal to the sample volume was added, and the sample was boiled for 3 min. A total of 0.6- to 0.7-mg brain equivalents were loaded onto a Novex 16% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis samples were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Membranes were developed using either enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) or Advanced ECL (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blots were developed using a 1:3,000 dilution of the 3F4 monoclonal antibody derived from hybridoma tissue culture supernatant. The secondary antibody was either a 1:3,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare) for ECL or a dilution of 1:250,000 for Advanced ECL.

RESULTS

Lack of a significant species barrier to human prion infection in mice overexpressing human prion protein.

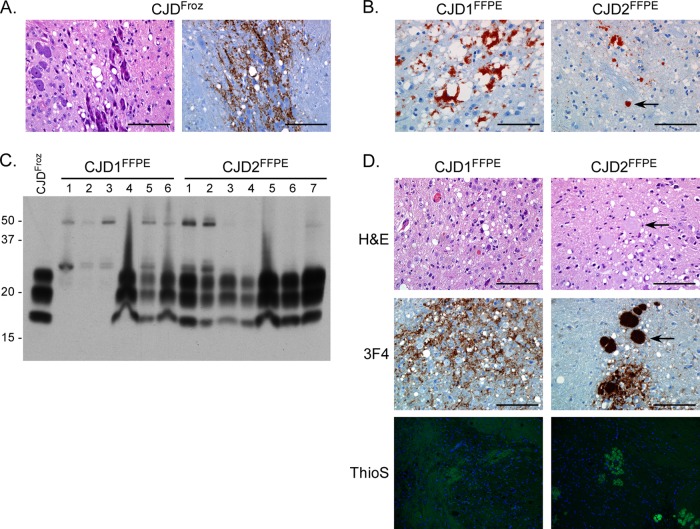

To determine whether or not there was a species barrier to infection between Tg66 mice and human sCJD, mice were inoculated with a stock homogenate made from a frozen brain sample of a common form of CJD, sCJD MM type 1 (CJDFroz). Consistent with previous reports (38), Tg66 mice developed disease after ∼169 days (Table 1). Clinically ill mice demonstrated spongiform change and both synaptic and perineuronal deposition of PrPSc in multiple areas, including the pons (Fig. 1A), thalamus, and hypothalamus (data not shown). There was no significant change in the incubation time of human CJDFroz that was passaged three times through Tg66 mice (Table 1). The fact that the disease incubation time of CJDFroz did not significantly change over multiple passages in Tg66 mice indicated that, as expected, there was no significant species barrier between Tg66 mice and infection with the most common form of sCJD.

Table 1.

Lack of a significant species barrier to sCJD MM type 1 prion infection in Tg66 mice

Each passage represents Tg66 mice inoculated with 50 μl of a 10−2 dilution of brain homogenate. The inoculum at passage 1 was sCJD MM type 1 (CJDFroz).

That is, the number of Tg66 mice with clinical disease over the total number of inoculated mice.

That is, the mean disease incubation time in days postinfection (dpi) ± standard deviation (SD) in days.

Fig 1.

Intracranial inoculation of FFPE sCJD brain tissue causes clinical or subclinical prion infection in Tg66 mice. (A) H&E (left panel)- and 3F4 (right panel)-stained sagittal sections from a clinically positive Tg66 mouse 167 days after inoculation with control CJDFroz brain homogenate. Spongiosis and PrPSc deposition (brown stain) are present in the pons. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Section of cortex stained with the anti-PrP monoclonal antibody 3F4 from a patient diagnosed with sCJD in 1979 (CJD1FFPE) or 1981 (CJD2FFPE). Both samples are positive for spongiosis and PrPSc (red stain). The arrow in the right panel indicates a unicentric PrPSc plaque. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Western blot analysis of brain homogenates from Tg66 mice inoculated with homogenates made from FFPE sCJD brain samples CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE. Each lane represents 0.7-mg brain equivalents of an individual mouse brain, except for the lane labeled CJDFroz, which represents brain homogenate from the sCJD MM type 1-positive control sample. The CJD1FFPE sample lanes 1 to 3 represent three mice that were euthanized for non-prion-disease-related causes at 113, 127, and 131 days postinfection. The blot was developed with the anti-PrP mouse monoclonal antibody 3F4 and the ECL development system. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. (D) H&E-, 3F4-, or Thioflavin S (ThioS)-stained sagittal brain sections from a Tg66 mouse at 234 (CJD1FFPE) or 648 (CJD2FFPE) days postinoculation with brain homogenate derived from FFPE sCJD brain samples. Spongiosis and PrPSc deposition (brown stain) are present in the midbrain in CJD1FFPE-inoculated mice and in the pons in CJD2FFPE-inoculated mice. The arrows in the top two right panels indicate a plaque visible in both the H&E- and 3F4-stained sections. ThioS-positive plaques were present only in animals inoculated with the CJD2FFPE sample. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Detection of hamster scrapie infectivity in FFPE hamster brain tissue.

The amount of FFPE human tissue available for inoculation was limited, and two techniques were tested to determine a relatively efficient way to recover enough tissue for inoculation into mice: (i) needle stab and (ii) removal and rehydration of tissue from the paraffin block. In order to determine the viability of the two techniques, the brain from a clinically positive Tg7 mouse infected with the hamster scrapie strain 263K (263KFroz) was formalin fixed for 4 days and paraffin embedded. The FFPE brain was stabbed with a needle that was then used to inoculate Tg7 mice i.c. The FFPE brain was then removed from the block, rehydrated, and homogenized, and the resulting homogenate (263KFFPE) was inoculated i.c. into Tg7 mice.

As shown in Table 2, slightly over half of the Tg7 mice inoculated with the 263KFFPE needle stab developed scrapie after ∼100 days, almost double the 52-day incubation time of mice inoculated with a brain homogenate stock of 263K hamster scrapie (Table 2, 263KFroz). In contrast, all Tg7 mice inoculated with 263KFFPE homogenate developed scrapie after ∼70 days (Table 2). A standard hamster 263K scrapie incubation time curve in Tg7 mice was used to roughly estimate the amount of infectivity recovered by needle stab at ∼1 ID50, while the amount of infectivity recovered by rehydration and homogenization of the FFPE brain tissue was ∼1,000 ID50. These values are consistent with previous studies of the amount of infectivity present in formaldehyde-treated 263K-infected hamster brain (40). Based on these results, the FFPE human tissue was processed for inoculation by removal from the block, rehydration, and homogenization.

Table 2.

Infection of transgenic mice overexpressing hamster PrPC with frozen or FFPE 263K scrapie-infected hamster brain

| Sample | Brain samplea | Clinical/totalb | Mean dpi ± SDc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 263KFroz | Frozen homogenate | 7/7 | 52 ± 5 |

| 263KFFPE | FFPE-stab | 6/10 | 99 ± 10 |

| 263KFFPE | FFPE-homogenate | 9/9 | 70 ± 7 |

Samples were inoculated into Tg7 mice overexpressing hamster PrPC. For both homogenate samples, 50 μl of a 10−2 dilution of the starting material was inoculated intracranially.

That is, the number of mice with clinical scrapie over the total number of inoculated mice.

That is, the mean disease incubation time in days postinfection (dpi) ± standard deviation (SD) in days.

Detection of PrPSc in archival formalin-fixed human brain tissue samples.

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded brain and heart tissue from two patients diagnosed with sCJD in 1979 and 1981 were obtained from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Since these individuals were diagnosed prior to the discovery of prion protein, it was unclear whether or not the fixed brain samples were positive for PrPSc. In order to confirm that PrPSc was present, sections were taken from each sample and stained with the mouse monoclonal antibody 3F4, which recognizes an epitope within human PrP. As shown in Fig. 1B, brain tissue from the first sample (CJD1FFPE) showed significant PrPSc deposition and spongiform pathology. PrPSc was found in dense perivacuolar deposits, as well as in both coarse and synaptic-like deposits. Brain tissue from the second sample (CJD2FFPE) was also positive for PrPSc but, unlike CJD1FFPE, demonstrated occasional unicentric plaque-like deposits of PrPSc (Fig. 1B, arrow) in addition to occasional perineuronal and synaptic-like deposition. In the limited sections analyzed, spongiform change did not appear to be as extensive in CJD2FFPE as in CJD1FFPE (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the brain samples, neither heart tissue sample showed any PrP positivity using the anti-PrP antibody 3F4 (Fig. 2A). PrPSc was therefore easily detectable in brain, but not heart, samples from both sCJD patients. The presence of PrPSc in the brains of these patients definitively confirmed the original diagnosis of sCJD.

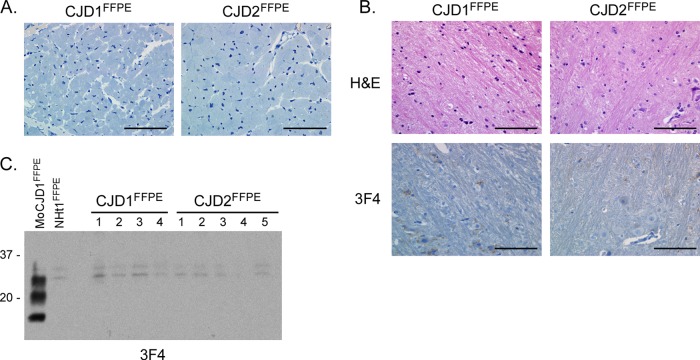

Fig 2.

Lack of PrPSc and spongiform pathology after i.c. inoculation of FFPE sCJD heart tissue into Tg66 mice. (A) Section of heart stained with the anti-PrP mouse monoclonal antibody 3F4 from a patient diagnosed with sCJD in 1979 (CJD1FFPE) and 1981 (CJD2FFPE). Both sections are negative for PrP. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) H&E- and 3F4-stained sagittal brain section from Tg66 mice 755 days postinoculation with heart homogenate derived from samples CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE. Unlike mice inoculated with the corresponding brain material (Fig. 1D), there is no spongiform change or PrPSc deposition in the midbrain in CJD1FFPE-inoculated mice or in the pons in CJD2FFPE-inoculated mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Western blot analysis of brain homogenates from Tg66 mice inoculated with FFPE heart homogenates derived from samples CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE. Each lane represents 0.7-mg brain equivalents of an individual mouse brain. MoCJD1FFPE, brain homogenate from a Tg66 mouse inoculated with CJD1FFPE; NHt1FFPE, brain homogenate from a Tg66 mouse inoculated with FFPE normal human heart sample. The blot was developed with the anti-PrP mouse monoclonal antibody 3F4 and the ECL advanced development system. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left.

Detection of sCJD infectivity in archival FFPE human brain tissue.

In order to determine whether sCJD infectivity was present in the FFPE brain tissue samples, both CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE samples, as well as a non-CJD FFPE brain (NBr1FFPE) were removed from the block, rehydrated, and homogenized in PBS to make a final 10% (wt/vol) brain homogenate. This material was then inoculated i.c. into Tg66 mice, and inoculated animals were monitored for disease. No clinical disease was observed in mice inoculated with NBr1FFPE (Table 3). In contrast, Tg66 mice inoculated with the CJD1FFPE sample developed clinical disease with an incubation time of ∼214 days, longer than control mice inoculated with homogenate derived from a frozen sCJD brain (CJDFroz, Table 3). Mice inoculated with CJD1FFPE that were clinically ill were positive for PrPSc by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C), although three mice that were lost due to intercurrent disease between 113 and 131 days (Table 3) had little or no detectable PrPSc (Fig. 1C, CJD1FFPE lanes 1 to 3). Perineuronal and synaptic-like deposition of PrPSc, as well as spongiform change, was seen primarily in the midbrain (Fig. 1D) and pons in clinically ill mice. PrPSc was not deposited as amyloid, as indicated by the lack of thioflavin S (ThioS) staining (Fig. 1D). A second passage of CJD1FFPE into Tg66 also caused clinical disease after ∼180 days (data not shown), confirming the presence of sCJD prion infectivity in the original sample. Thus, sufficient prion infectivity was present in the CJD1FFPE sample to initiate prion infection and PrPSc formation in all surviving Tg66 mice.

Table 3.

Infection of Tg66 mice with frozen or FFPE human brain and heart tissue

| Samplea | Tissue homogenate | PrPSc | Clinical/totalb | Mean dpi or rangec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CJDFroz | Brain | Positive | 4/4 | 163 ± 6 |

| CJD1FFPE | Brain | Positive | 3/3d | 214 ± 15 |

| Heart | Negative | 0/6 | 370–755 | |

| CJD2FFPE | Brain | Positive | 0/7 | 495–648 |

| Heart | Negative | 0/7 | 127–755 | |

| AHD1FFPE | Heart | Negative | 0/6e | 130–562 |

| AHD2FFPE | Heart | Negative | 0/6 | 354–622 |

| NBr1FFPE | Brain | Negative | 0/4 | 420–709 |

| NHt1FFPE | Heart | Negative | 0/4 | 404–581 |

| NHt2FFPE | Heart | Negative | 0/4 | 464–729 |

Samples were inoculated into Tg66 mice. For all samples, 50 μl of a 10−2 dilution of the starting material was inoculated intracranially.

That is, the number of mice with clinical disease over the total number of inoculated mice.

That is, the mean disease incubation time ± standard deviation (SD) in days or the range in days of non-TSE-related intercurrent deaths. dpi, days postinfection.

The number excludes three intercurrent deaths at 113, 127, and 131 days postinfection (dpi). Brain tissue from these mice had little or no PrPSc (see Fig. 1).

This number excludes one intercurrent death at 88 dpi.

In contrast to both the CJD1FFPE sample and the positive control sample CJDFroz, a homogenate derived from the fixed human brain sample CJD2FFPE did not cause clinical disease in Tg66 mice after i.c. inoculation (Table 1). However, all mice inoculated with CJD2FFPE were positive for PrPSc by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C), suggesting that they were subclinically infected. These results were confirmed via immunohistochemical analysis using the 3F4 antibody (Fig. 1D). Unlike CJD1FFPE, mice inoculated with the CJD2FFPE sample had synaptic-like PrPSc staining as well as large, PrPSc-positive plaques in the pons (Fig. 1D), hypothalamus, cortex, and corpus callosum, as well as subpially (data not shown). These plaques were ThioS positive (Fig. 1D), indicating that PrPSc was deposited as amyloid. In addition, both spongiform change and large plaques were visible by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 1D). A second passage of CJD2FFPE into Tg66 is in progress and has resulted in clinical disease roughly 400 days postinoculation (data not shown), confirming that the first passage into Tg66 mice induced a subclinical prion infection. Thus, using Tg66 mice, we were able to detect both clinical and subclinical levels of sCJD infectivity in FFPE brain tissue which, at the time of inoculation, was >26 years old.

Lack of prion infectivity in sCJD heart tissue.

The neuropathological profile associated with a given prion isolate remains the same whether the infectious homogenate is derived from the brain or a non-CNS tissue (41). Therefore, if the formalin-fixed heart tissue from samples CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE contained prion infectivity, they should trigger the same pathology as the corresponding fixed brain tissue when inoculated into Tg66 mice. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded CJD1FFPE and CJD2FFPE heart samples, both of which were determined to be negative for PrPSc by immunohistochemistry using the 3F4 antibody (Fig. 2A), were removed from the block, rehydrated, and homogenized in PBS to make a final 10% (wt/vol) heart homogenate. This material was then inoculated i.c. into Tg66 mice, and the mice were monitored for disease. After 755 days, when the experiment was terminated, none of the inoculated mice had shown any sign of clinical disease (Table 3). There was no PrPSc deposition in any area of the brain (Fig. 2B), including the regions of the brain that had been strongly PrPSc positive following inoculation of the corresponding FFPE brain samples. The lack of PrPSc in the brain was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2C). Thus, we were unable to detect any sign of prion infectivity in heart tissue from two sCJD-positive individuals.

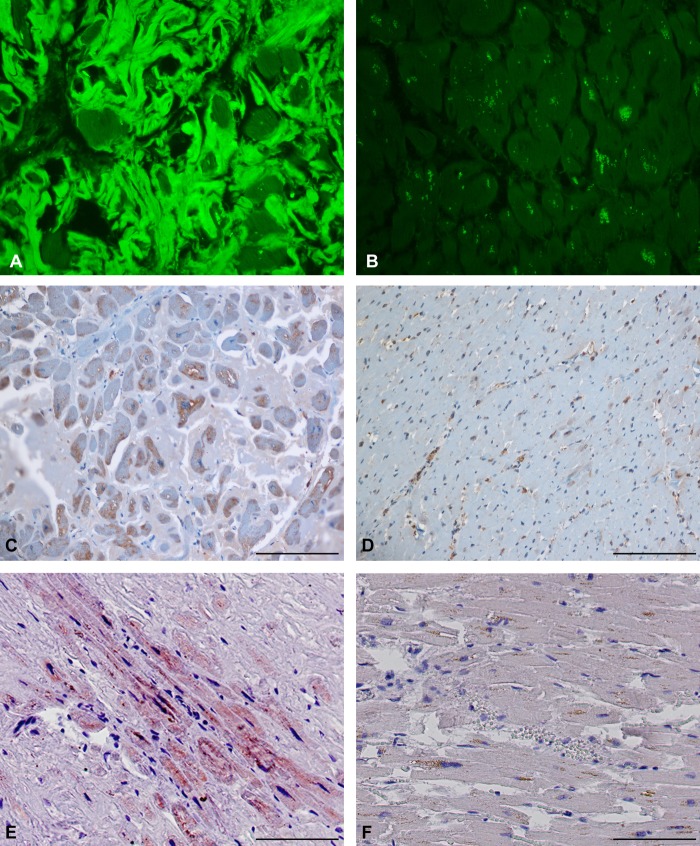

Detection of prion protein in amyloid heart disease tissue.

We have previously shown that transgenic mice expressing PrPC without the GPI membrane anchor can accumulate high levels of PrPSc amyloid and infectivity in the heart after infection with mouse scrapie (18). These results suggested the possibility that abnormal prion protein deposited as amyloid in human heart tissue might also be infectious. We tested heart tissue samples from 42 cases of human amyloid heart disease for the presence of protease-resistant prion protein. Of the 42 samples tested, 6 were positive for PrP, an example of which (AHD1FFPE) is shown in Fig. 3. ThioS staining confirmed the presence of cardiac amyloid in AHD1FFPE (Fig. 3A) but not in normal heart tissue (Fig. 3B). Cells in the AHD1FFPE sample were positive using the anti-PrP antibody PV30 (Fig. 3C), which has a very high affinity for human PrPC (see Materials and Methods). The positive signal remained following PK digestion (Fig. 3E), suggesting the presence of protease-resistant PrP. The specificity of the stain for PrP was confirmed by the loss of positive signal using PV30 antibody that had been preabsorbed with a PrP peptide containing the PV30 epitope from residues 96 to 105 (Fig. 3F). In contrast, in the NHt2FFPE sample, PV30 staining was primarily associated with blood vessels and not cells (Fig. 3D), and all samples of normal heart tissue were negative for protease-resistant PrP (data not shown). Overall, no protease-resistant PrP was detected in 30 nonamyloid heart samples, suggesting that the signal observed in the amyloid hearts was specific to the diseased tissue. Thus, consistent with the possibility that abnormal PrP might accumulate in the heart, protease-resistant PrP was present at detectable levels in at least a subset of individuals with amyloid heart disease.

Fig 3.

Amyloid and protease-resistant PrP are present in FFPE amyloid heart tissue. (A) Section of heart tissue from sample AHD1FFPE stained with ThioS. Significant ThioS immunofluorescence indicative of amyloid can be seen surrounding the cells. (B) Section of heart tissue from sample NHt2FFPE stained with ThioS. No significant immunofluorescence is present. (C) Section of heart tissue from sample AHD1FFPE stained with the anti-PrP antibody PV30. Antibody reactivity is represented by the brown stain over the cells, indicating the presence of PrP. The pale blue stain surrounding the cells is amyloid. (D) Section of heart tissue from sample NHt2FFPE stained with the anti-PrP antibody PV30. Antibody reactivity is localized primarily to blood vessels and blood cells. (E) Section of heart tissue from sample AHD1FFPE stained with the anti-PrP antibody PV30 after treatment with PK. Antibody reactivity is represented by the brown stain over the cells and indicates the presence of protease-resistant PrP. (F) Section of heart tissue from a patient diagnosed with amyloid heart disease (AHD1FFPE). The section was stained with PV30 preabsorbed with a peptide containing the PV30 antibody epitope. No positive signal was seen. For all panels, the scale bar represents 100 μm.

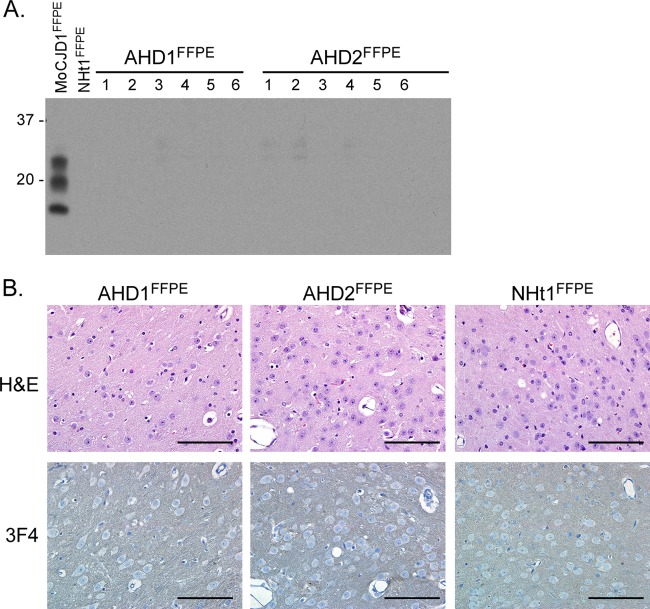

Lack of prion infectivity in amyloid heart disease tissue.

In order to determine whether or not the PrP signal detected in cardiac tissue from amyloid heart disease patients was indicative of prion infectivity, FFPE amyloid heart tissue from two prion protein-positive patients (AHD1FFPE and AHD2FFPE) and two nonamyloid heart samples (NHt1FFPE and NHt2FFPE) were removed from the block, rehydrated, and homogenized in PBS to make a final 10% (wt/vol) heart homogenate. This material was then inoculated i.c. into Tg66 mice, and the mice were monitored for disease. None of the mice inoculated with FFPE amyloid heart tissue demonstrated any sign of clinical disease up to 622 days postinoculation, whereas mice inoculated with FFPE nonamyloid heart tissue showed no signs of clinical disease up to 729 days postinoculation (Table 3). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that there was no PrPSc in the brain of any mice inoculated with AHD1FFPE and AHD2FFPE (Fig. 4A), and immunohistochemical analysis of brain tissue showed a level of 3F4 reactivity indistinguishable from that of Tg66 mice inoculated with normal fixed heart tissue (Fig. 4B). Thus, there was no detectable infectivity in PrP-positive amyloid heart tissue, strongly suggesting that the signal detected by the PV30 antibody was not infectious prion protein.

Fig 4.

Lack of PrPSc and spongiform pathology after i.c. inoculation of Tg66 mice with FFPE amyloid heart tissue positive for protease-resistant PrP. (A) Western blot analysis of brain homogenates from Tg66 mice inoculated with heart homogenate derived from FFPE amyloid heart disease samples AHD1FFPE and AHD2FFPE. Each lane represents 0.7-mg brain equivalents of an individual mouse brain. MoCJD1FFPE brain, brain homogenate from a Tg66 mouse inoculated with CJD1FFPE; NHt1FFPE, brain homogenate from a Tg66 mouse inoculated with NHt1FFPE. The blot was developed with the anti-PrP mouse monoclonal antibody 3F4 and the ECL advanced development system. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. (B) H&E- and 3F4-stained thalamus from Tg66 mice 562 (AHD1FFPE), 622 (AHD2FFPE), or 581 (Nht1FFPE) days postinoculation with homogenate derived from FFPE human amyloid heart disease or normal heart samples. There is no spongiform change or PrPSc deposition in any sample. Scale bar, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

We were unable to induce clinical or subclinical prion infection following inoculation of fixed heart tissue from two sCJD patients into transgenic mice overexpressing the human prion protein. One caveat to our experiments is that we used FFPE tissue in our inoculations. It has been known since the 1930s that scrapie can survive formalin fixation (42) but, as shown here (Table 2) and in previous work (40), fixation in formalin can reduce infectivity by several logs. This could have an impact in tissues with lower levels of prion infectivity. For example, a recent study has shown that, while homogenates derived from vCJD appendix could transmit disease to 50% of transgenic mice expressing human PrPC, an FFPE vCJD appendix did not cause an infection (43). We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that low levels of infectivity which might have been present in sCJD heart tissue were inactivated following formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. However, our results are in agreement with previous studies that used sensitive Western blotting techniques (9, 12), immunohistochemistry (19), or inoculation of nonhuman primates (25) to assay for sCJD infectivity in heart tissue. Thus, our results are consistent with the conclusion that prion infectivity is not likely to be present in the hearts of patients with sCJD.

A common amino acid polymorphism at codon 129 in human PrP, encoding either a methionine or valine, can influence the efficient transmission of human prions into transgenic mice expressing human PrP (44–46). With the exception of AHD2FFPE, which is homozygous for methionine at codon 129 (see Materials and Methods), we have as yet been unable to clearly determine the amino acid residue at codon 129 of our FFPE tissue samples. It is therefore possible that a mismatch at codon 129 could influence the transmission of infectivity into Tg66 mice, which overexpress human PrP with a methionine at codon 129. It is important to note, however, that inoculation of sCJD from different Prnp genotypes can still lead to efficient clinical and/or subclinical infection in transgenic mice overexpressing human PrP with a methionine at codon 129 (45). Thus, if sufficient levels of infectivity were present, we would still expect that, regardless of genotype, some percentage of Tg66 mice inoculated with PrP-positive FFPE heart tissue would be positive for PrPSc by immunohistochemistry or Western blotting.

The identification of an infectious cardiac amyloidosis with high levels of PrPSc amyloid and infectivity in the heart of a transgenic mouse model of scrapie (18) raised the possibility that abnormal forms of PrP might also be an unrecognized component of amyloid heart disease in humans. Interestingly, Jansen et al. (15) found mutations in human Prnp that resulted in the absence of the GPI anchor in PrP, which predisposed to amyloid plaque formation in the CNS. Given the multiorgan distribution of PrPSc amyloid in mice expressing PrPC without the GPI anchor (17) and the recent identification of a prion amyloid myopathy in a BSE-infected macaque (22), PrPSc amyloid might also be present outside of the CNS in humans with anchorless PrPC. However, the presence of PrPSc and prion infectivity in the heart and other organs has not yet been assessed in the human cases where PrP does not contain the GPI anchor (15). Consistent with the possibility that amyloid heart tissue might contain prion infectivity, we were able to detect PrP positivity in 6/42 (14%) human amyloid heart disease samples. However, inoculation of two of these positive samples into Tg66 mice did not lead to disease (Table 3), indicating that the PrP detected was not infectious PrPSc.

Although the signal in the PV30-positive amyloid heart samples does not appear to be infectious PrPSc, the fact that it could be blocked by a PrP peptide specific to PV30 (Fig. 3F) suggests that it could a form of PrP that is abnormal but noninfectious. It is well known that normal PrPC expression can increase under stressful conditions such as hypoxia (47) or ischemia (48) and that the overexpression of normal PrPC in muscle tissue can lead to increased protease resistance and myopathy (49, 50). It is therefore possible that the PrP signal detected by PV30, which was cell associated (Fig. 3C and E), was a result of some form of cellular stress which led to an increase in PrPC expression and the production of abnormal forms of PrP that were more protease resistant. This would explain why PrP-specific signal was detected by the PV30 antibody even after PK digestion. Consistent with this possibility, cell-associated PrP staining was not detected in nonamyloid heart tissue (Fig. 3D) or in heart tissue from the two sCJD cases examined (Fig. 2A and data not shown). That PrP was detected only in a minority of the amyloid heart disease cases examined may explain why PrP-positive staining was not seen in a previous report that examined a smaller number of human amyloid heart samples (19).

One advantage of the present study over previous infectivity studies of sCJD heart is in the assay system used, i.e., the Tg66 mice. Unlike the nonhuman primate studies, and as evidenced by the fact that there was no change in incubation time when sCJD MM type I was passaged in Tg66 mice three consecutive times, there is no significant species barrier to transmission of the most common form of sCJD. Furthermore, the mice appear to be sensitive enough to detect relatively low levels of infectivity. Inoculation of the CJD1FFPE sample led to clinical disease in all recipient mice, indicating that the tissue analyzed contained more than a single 50% lethal dose (LD50), i.e., the dose of inoculum that would lead to fatal disease in 50% of the animals. However, while inoculation of the CJD2FFPE brain sample also led to PrPSc accumulation in all of the mice, there was insufficient infectivity to induce clinical disease. This indicated that less than one LD50 was present in the CJD2FFPE sample. Thus, these data suggest that the Tg66 mice are a sensitive enough assay system to detect less than one LD50/50 μl of 1% brain homogenate. By comparison, it has been conservatively estimated that a highly sensitive Western blotting technique can detect brain PrPSc levels equivalent to ≥1,000 LD50/ml (i.e., ≥20 LD50/50 μl) (12).

Earlier studies had demonstrated that CJD infectivity could be recovered from FFPE tissue that had been stored for 7 months (51) and 21 months (52). Our results demonstrate that FFPE sCJD brain tissue stored for as long as 28 years still contains sufficient prion infectivity to infect 100% of inoculated animals. Thus, FFPE sCJD tissue can harbor >1 ID50 of sCJD infectivity. The fact that prions can survive for decades in archival tissues reinforces the fact that extra precautions should always be used when manipulating or disposing of archival sCJD tissues.

Our results also suggest that the characteristics of different sCJD prion isolates can be maintained following formalin fixation and storage over decades. Deposition of PrPSc in the brain samples analyzed differed between the two isolates. In particular, unicentric PrPSc plaques were frequently found in the CJD2FFPE sample but not in the CJD1FFPE sample (Fig. 1B). The pattern of PrPSc deposition in the brains of Tg66 mice inoculated with CJD1FFPE or CJD2FFPE brain material was consistent with this difference. Mice inoculated with CJD2FFPE had abundant PrPSc-positive plaques, whereas CJD1FFPE inoculated mice did not (Fig. 1D). To the best of our knowledge, these are the first data to suggest that formalin fixation, followed by paraffin embedding and long-term storage, does not eliminate the differences in neuropathological phenotypes induced by different prion isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Byron Caughey and Karin Peterson for critically reviewing the manuscript and Pedro Piccardo and Blaise Favarra for helpful pathology discussions. We also thank Cynthia Favarra, Nancy Kurtz, and Dan Long for technical assistance with the immunohistochemistry and Anita Mora for graphical assistance.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and USPHS grant AG04342.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown P, Brandel JP, Sato T, Nakamura Y, Mackenzie J, Will RG, Ladogana A, Pocchiari M, Leschek EW, Schonberger LB. 2012. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, final assessment. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:901–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay GA, Knight RS, Ironside JW. 2011. The molecular epidemiology of variant CJD. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2:217–227 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wroe SJ, Pal S, Siddique D, Hyare H, Macfarlane R, Joiner S, Linehan JM, Brandner S, Wadsworth JD, Hewitt P, Collinge J. 2006. Clinical presentation and pre-mortem diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease associated with blood transfusion: a case report. Lancet 368:2061–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llewelyn CA, Hewitt PE, Knight RS, Amar K, Cousens S, Mackenzie J, Will RG. 2004. Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet 363:417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peden A, McCardle L, Head MW, Love S, Ward HJ, Cousens SN, Keeling DM, Millar CM, Hill FG, Ironside JW. 2010. Variant CJD infection in the spleen of a neurologically asymptomatic UK adult patient with haemophilia. Haemophilia 16:296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendheim PE, Brown HR, Rudelli RD, Scala LJ, Goller NL, Wen GY, Kascsak RJ, Cashman NR, Bolton DC. 1992. Nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution of the scrapie agent precursor protein. Neurology 42:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horiuchi M, Yamazaki N, Ikeda T, Ishiguro N, Shinagawa M. 1995. A cellular form of prion protein (PrPC) exists in many non-neuronal tissues of sheep. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt 10):2583–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadsworth JD, Joiner S, Hill AF, Campbell TA, Desbruslais M, Luthert PJ, Collinge J. 2001. Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immunoblotting assay. Lancet 358:171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Head MW, Ritchie D, Smith N, McLoughlin V, Nailon W, Samad S, Masson S, Bishop M, McCardle L, Ironside JW. 2004. Peripheral tissue involvement in sporadic, iatrogenic, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: an immunohistochemical, quantitative, and biochemical study. Am. J. Pathol. 164:143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitamoto T, Mohri S, Tateishi J. 1989. Organ distribution of proteinase-resistant prion protein in humans and mice with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Gen. Virol. 70(Pt 12):3371–3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hainfellner JA, Budka H. 1999. Disease associated prion protein may deposit in the peripheral nervous system in human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 98:458–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peden AH, Ritchie DL, Head MW, Ironside JW. 2006. Detection and localization of PrPSc in the skeletal muscle of patients with variant, iatrogenic, and sporadic forms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Am. J. Pathol. 168:927–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glatzel M, Abela E, Maissen M, Aguzzi A. 2003. Extraneural pathologic prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:1812–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs GG, Lindeck-Pozza E, Chimelli L, Araujo AQ, Gabbai AA, Strobel T, Glatzel M, Aguzzi A, Budka H. 2004. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and inclusion body myositis: abundant disease-associated prion protein in muscle. Ann. Neurol. 55:121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen C, Parchi P, Capellari S, Vermeij AJ, Corrado P, Baas F, Strammiello R, van Gool WA, van Swieten JC, Rozemuller AJ. 2010. Prion protein amyloidosis with divergent phenotype associated with two novel nonsense mutations in PRNP. Acta Neuropathol. 119:189–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chesebro B, Trifilo M, Race R, Meade-White K, Teng C, LaCasse R, Raymond L, Favara C, Baron G, Priola S, Caughey B, Masliah E, Oldstone M. 2005. Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie. Science 308:1435–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee AM, Paulsson JF, Cruite J, Andaya AA, Trifilo MJ, Oldstone MB. 2011. Extraneural manifestations of prion infection in GPI-anchorless transgenic mice. Virology 411:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trifilo MJ, Yajima T, Gu Y, Dalton N, Peterson KL, Race RE, Meade-White K, Portis JL, Masliah E, Knowlton KU, Chesebro B, Oldstone MB. 2006. Prion-induced amyloid heart disease with high blood infectivity in transgenic mice. Science 313:94–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tennent GA, Head MW, Bishop M, Hawkins PN, Will RG, Knight R, Peden AH, McCardle LM, Ironside JW, Pepys MB. 2007. Disease-associated prion protein is not detectable in human systemic amyloid deposits. J. Pathol. 213:376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashwath ML, Dearmond SJ, Culclasure T. 2005. Prion-associated dilated cardiomyopathy. Arch. Intern. Med. 165:338–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzog C, Riviere J, Lescoutra-Etchegaray N, Charbonnier A, Leblanc V, Sales N, Deslys JP, Lasmezas CI. 2005. PrPTSE distribution in a primate model of variant, sporadic, and iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Virol. 79:14339–14345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krasemann S, Mearini G, Krämer E, Wagenfü-hr , Schulz-Schaeffer KW, Neumann M, Bodemer W, Kaup F-J, Beekes M, Carrier L, Aguzzi A, Glatzel M. 2013. BSE-associated prion-amyloid cardiomyopathy in primates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19:985–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bessen RA, Robinson CJ, Seelig DM, Watschke CP, Lowe D, Shearin H, Martinka S, Babcock AM. 2011. Transmission of chronic wasting disease identifies a prion strain causing cachexia and heart infection in hamsters. PLoS One 6:e28026. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jewell JE, Brown J, Kreeger T, Williams ES. 2006. Prion protein in cardiac muscle of elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) infected with chronic wasting disease. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3443–3450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown P, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Rodgers-Johnson P, Asher DM, Sulima MP, Bacote A, Goldfarb LG, Gajdusek DC. 1994. Human spongiform encephalopathy: the National Institutes of Health series of 300 cases of experimentally transmitted disease. Ann. Neurol. 35:513–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasmezas CI, Deslys JP, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin JM, Fournier JG, Hauw JJ, Rossier J, Dormont D. 1997. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science 275:402–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barron RM, Thomson V, Jamieson E, Melton DW, Ironside J, Will R, Manson JC. 2001. Changing a single amino acid in the N terminus of murine PrP alters TSE incubation time across three species barriers. EMBO J. 20:5070–5078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barron RM, Campbell SL, King D, Bellon A, Chapman KE, Williamson RA, Manson JC. 2007. High titers of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy infectivity associated with extremely low levels of PrPSc in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 282:35878–35886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manson JC, Jamieson E, Baybutt H, Tuzi NL, Barron R, McConnell I, Somerville R, Ironside J, Will R, Sy MS, Melton DW, Hope J, Bostock C. 1999. A single amino acid alteration (101L) introduced into murine PrP dramatically alters incubation time of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. EMBO J. 18:6855–6864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickinson AG. 1976. Scrapie in sheep and goats, p 209–241 In Dickinson AG. (ed), Slow virus diseases of animals and man. North Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimberlin RH, Walker CA. 1979. Pathogenesis of scrapie: agent multiplication in brain at the first and second passage of hamster scrapie in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 42:107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prusiner SB, Scott M, Foster D, Pan KM, Groth D, Mirenda C, Torchia M, Yang SL, Serban D, Carlson GA. 1990. Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 63:673–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. 1987. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J. Virol. 61:3688–3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolton DC, Seligman SJ, Bablanian G, Windsor D, Scala LJ, Kim KS, Chen CM, Kascsak RJ, Bendheim PE. 1991. Molecular location of a species-specific epitope on the hamster scrapie agent protein. J. Virol. 65:3667–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safar JG, Scott M, Monaghan J, Deering C, Didorenko S, Vergara J, Ball H, Legname G, Leclerc E, Solforosi L, Serban H, Groth D, Burton DR, Prusiner SB, Williamson RA. 2002. Measuring prions causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy or chronic wasting disease by immunoassays and transgenic mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1147–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang WP, Green K, Pinz-Sweeney S, Briones AT, Burton DR, Barbas CF., III 1995. CDR walking mutagenesis for the affinity maturation of a potent human anti-HIV-1 antibody into the picomolar range. J. Mol. Biol. 254:392–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop MT, Hart P, Aitchison L, Baybutt HN, Plinston C, Thomson V, Tuzi NL, Head MW, Ironside JW, Will RG, Manson JC. 2006. Predicting susceptibility and incubation time of human-to-human transmission of vCJD. Lancet Neurol. 5:393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Race B, Meade-White KD, Miller MW, Barbian KD, Rubenstein R, LaFauci G, Cervenakova L, Favara C, Gardner D, Long D, Parnell M, Striebel J, Priola SA, Ward A, Williams ES, Race R, Chesebro B. 2009. Susceptibilities of nonhuman primates to chronic wasting disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1366–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Race R, Oldstone M, Chesebro B. 2000. Entry versus blockade of brain infection following oral or intraperitoneal scrapie administration: role of prion protein expression in peripheral nerves and spleen. J. Virol. 74:828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown P, Rohwer RG, Green EM, Gajdusek DC. 1982. Effect of chemicals, heat, and histopathologic processing on high-infectivity hamster-adapted scrapie virus. J. Infect. Dis. 145:683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Outram GW, Fraser H, Wilson DT. 1973. Scrapie in mice. Some effects on the brain lesion profile of ME7 agent due to genotype of donor, route of injection and genotype of recipient. J. Comp. Pathol. 83:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon WS. 1946. Advances in veterinary research. Vet. Rec. 58:516–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wadsworth JD, Dalmau-Mena I, Joiner S, Linehan JM, O'Malley C, Powell C, Brandner S, Asante EA, Ironside JW, Hilton DA, Collinge J. 2011. Effect of fixation on brain and lymphoreticular vCJD prions and bioassay of key positive specimens from a retrospective vCJD prevalence study. J. Pathol. 223:511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asante EA, Linehan JM, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Gowland I, Wood AL, Welch J, Hill AF, Lloyd SE, Wadsworth JD, Collinge J. 2002. BSE prions propagate as either variant CJD-like or sporadic CJD-like prion strains in transgenic mice expressing human prion protein. EMBO J. 21:6358–6366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asante EA, Linehan JM, Gowland I, Joiner S, Fox K, Cooper S, Osiguwa O, Gorry M, Welch J, Houghton R, Desbruslais M, Brandner S, Wadsworth JD, Collinge J. 2006. Dissociation of pathological and molecular phenotype of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in transgenic human prion protein 129 heterozygous mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10759–10764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bishop MT, Will RG, Manson JC. 2010. Defining sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strains and their transmission properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:12005–12010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams WM, Stadtman ER, Moskovitz J. 2004. Ageing and exposure to oxidative stress in vivo differentially affect cellular levels of PrP in mouse cerebral microvessels and brain parenchyma. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 30:161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weise J, Crome O, Sandau R, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Bahr M, Zerr I. 2004. Upregulation of cellular prion protein (PrPc) after focal cerebral ischemia and influence of lesion severity. Neurosci. Lett. 372:146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westaway D, Dearmond SJ, Cayetano-Canlas J, Groth D, Foster D, Yang SL, Torchia M, Carlson GA, Prusiner SB. 1994. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and the central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell 76:117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang S, Liang J, Zheng M, Li X, Wang M, Wang P, Vanegas D, Wu D, Chakraborty B, Hays AP, Chen K, Chen SG, Booth S, Cohen M, Gambetti P, Kong Q. 2007. Inducible overexpression of wild-type prion protein in the muscles leads to a primary myopathy in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6800–6805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr 1976. Survival of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease virus in formol-fixed brain tissue. N. Engl. J. Med. 294:553 (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown P, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Gajdusek DC, Cathala F, LaBauge R. 1986. Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human brain tissue. N. Engl. J. Med. 315:1614–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]