Abstract

We are interested in the root microbiome of the fast-growing Eastern cottonwood tree, Populus deltoides. There is a large bank of bacterial isolates from P. deltoides, and there are 44 draft genomes of bacterial endophyte and rhizosphere isolates. As a first step in efforts to understand the roles of bacterial communication and plant-bacterial signaling in P. deltoides, we focused on the prevalence of acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) quorum-sensing-signal production and reception in members of the P. deltoides microbiome. We screened 129 bacterial isolates for AHL production using a broad-spectrum bioassay that responds to many but not all AHLs, and we queried the available genome sequences of microbiome isolates for homologs of AHL synthase and receptor genes. AHL signal production was detected in 40% of 129 strains tested. Positive isolates included members of the Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria. Members of the luxI family of AHL synthases were identified in 18 of 39 proteobacterial genomes, including genomes of some isolates that tested negative in the bioassay. Members of the luxR family of transcription factors, which includes AHL-responsive factors, were more abundant than luxI homologs. There were 72 in the 39 proteobacterial genomes. Some of the luxR homologs appear to be members of a subfamily of LuxRs that respond to as-yet-unknown plant signals rather than bacterial AHLs. Apparently, there is a substantial capacity for AHL cell-to-cell communication in proteobacteria of the P. deltoides microbiota, and there are also Proteobacteria with LuxR homologs of the type hypothesized to respond to plant signals or cues.

INTRODUCTION

Many Proteobacteria use acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) quorum-sensing (QS) signals for cell density-dependent gene regulation. Generally, AHL QS involves two regulatory genes, a member of the luxI family of AHL synthase genes and a member of the luxR family of AHL-responsive transcriptional regulatory genes. The luxR-luxI regulatory circuit in the marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri uses the freely diffusible N-3-oxohexanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL) as a proxy for cell density to activate luminescence (lux) gene expression (1). Dozens of species of Proteobacteria possess homologs of luxI and luxR systems (2). The luxI homologs code for enzymes that collectively generate a variety of AHLs. Most of the described AHLs are fatty acyl AHLs with acyl groups of various lengths (C4 to C18). These AHLs possess either a hydroxyl, a carbonyl, or no substitution on the third carbon and can vary in the degree of side chain saturation (3, 4). More recently, LuxI homologs have been identified that synthesize aromatic (5, 6) and branched-chain AHLs (7). The luxR and luxI homologs are often but not always tightly linked, and AHL-responsive transcription factors show the greatest sensitivity to the signal produced by their cognate AHL synthase. Bacteria can contain multiple luxI-luxR homologs. For example, Pseudomonas aeruginosa possesses two AHL QS systems, the LasI-LasR system and the RhlI-RhlR system (8–10). Proteobacteria genomes can also possess orphan or solo luxR homologs. These are luxR homologs without a paired luxI homolog (2, 11). In fact, some bacteria have luxR homologs and do not have any luxI homologs. For example, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium possess a luxR homolog called sdiA, which codes for a transcription factor responsive to AHLs produced by other bacteria (12). Some luxR homologs in plant-associated bacteria code for transcription factors that respond to plant-derived signals of unknown composition rather than AHLs (reviewed in reference 13).

Recently, we have undertaken a microbiome study in an effort to better understand the dynamic interface that exists between plant microbes and their hosts by using the woody perennial Populus as a model (14). Populus has intimate associations with arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal fungi (15), as well as endophytic and rhizosphere bacteria (14, 16). It was the first tree to have its genome fully sequenced (17), and it has potential as a biofuel feedstock for cellulosic ethanol production (18). Because we know that AHL quorum sensing occurs in many plant pathogens, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens (19), Pantoea carotovora (20), and Pseudomonas syringae (21), and in beneficial plant bacteria, such as Bradyrhizobium japonicum (7) and Rhizobium leguminosarum (22, 23), we were interested in assessing the prevalence of AHL QS systems and orphan luxR genes among members of the Populus deltoides (Eastern cottonwood) microbiota. rRNA sequence analysis revealed distinct bacterial endophyte and rhizosphere P. deltoides root microbiota (14). The rhizosphere is dominated by Acidobacteria (31%) and Alphaproteobacteria (30%), and endophytes are mainly Gammaproteobacteria (54%) and Alphaproteobacteria (23%) (14). Interestingly, nearly 35% of the endophytic bacterial sequences were comprised of a single Pseudomonas fluorescens-like operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (14). Approximately 1,100 bacteria have been isolated from P. deltoides tree roots collected from sites in Tennessee and North Carolina (24). Furthermore, draft genome sequences are available for over 40 different isolates, of which about half are members of the genus Pseudomonas (24, 25).

The rhizosphere and endophyte strain collection and available genomic sequence data (24, 25) have allowed us to take a census, or inventory, of the prevalence of AHL production and luxI and luxR homologs in members of the P. deltoides microbiome. We view this as a first step toward understanding the roles these factors play in the biology of this tree. Here, we describe a survey of 129 P. deltoides bacterial isolates for AHL production and an informatics investigation of the draft genomes of 44 isolates for luxI and luxR homologs. Our results suggest that AHL signaling is prevalent among members of the P. deltoides rhizosphere and endophyte microbiota, that solo or orphan luxR homologs are even more prevalent than complete AHL circuits, and that homologs of the putative plant signal-responsive LuxR enzymes exist in some members of the P. deltoides microbiota.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Over 1,100 bacterial isolates from P. deltoides root samples taken near either the Caney Fork River (isolates with AP, GM, BT, or CF strain designations) in central Tennessee or the Yadkin River (isolates with YR strain designations) in North Carolina were available for our study (14, 26). Rhizosphere isolates were obtained as described elsewhere (14, 25). Isolates designated endophytes were obtained as follows: roots were surface sterilized via serial washes in sterile water, 3% H2O2, 6.15% NaOCl as described previously (14), and surface sterility was confirmed by touching the washed roots to LB plates and observing a lack of microbial growth. Fine roots were pulverized with a sterile mortar and pestle in 10 ml of MgSO4 (10 mM) (14). The large debris was allowed to settle, and 100-μl samples were plated on R2A agar plates (Difco), which were incubated at 25°C. Colonies arising after several days of incubation were picked and restreaked a minimum of three times on R2A agar at 25°C. The isolation of Rhizobium sp. strain PDO1-076 has been described elsewhere (25).

Screening selected isolates for AHL production.

We assessed the ability of 129 isolates representing several genera of Proteobacteria to produce fatty AHLs as follows: isolates were grown in 5 ml of buffered tryptone yeast extract broth [0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.13% CaCl2, and 50 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7] or DM medium [50 mM potassium phosphate, 0.1% (NH4)2SO4, 0.2% NaCl, 7 mg/ml MnSO4·4H2O, 0.02% MgSO4·7H2O, 8 mg/ml CaCl2·2H2O, 0.07% l-arginine, 0.01% l-glutamine, 1 mg/ml biotin, 1 mg/ml thiamine, 20% glucose] broth with shaking at 30°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the culture supernatant fluid was extracted twice with equal volumes of acidified ethyl acetate and concentrated as described previously (27). Extracts were screened for AHL activity by using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens KYC55 (pJZ372, pJZ384, and pJZ410) bioassay method (28).

LuxI and LuxR phylogenies.

We queried the 44 P. deltoides draft bacterial genome sequences for genes encoding LuxR or LuxI homologs by using the Integrated Microbial Genomes Database (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/w/main.cgi). We aligned homologs by using Clustal W (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton protein distance algorithm, followed by the distance matrix-based Fitch algorithm in PHYLIP (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html), and visualized with Phylodendron Treeprint (http://www.es.embnet.org/Doc/phylodendron/treeprint-form.html).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Production of AHLs by selected P. deltoides rhizosphere and endophytic Proteobacteria.

As assessed by 16S rRNA gene sequence relationships, the collection of P. deltoides rhizosphere and endophytic isolates represented 85 bacterial genera. The most-abundant taxa were Actinobacterium, 14%, Bacillus, 17%, Alphaproteobacteria, 22%, Betaproteobacteria, 16%, and Gammaproteobacteria, 22% (24). We limited our screen to Proteobacteria because AHL QS is believed to be limited to this taxon. We screened 44 rhizosphere isolates and 85 endophytes from roots of mature P. deltoides trees for the production of AHLs that can be detected by a broad-range bioassay that responds to AHLs with fatty acyl chains ranging in length between 4 and 18 carbons (see Materials and Methods; also see references 28 and 29). The bioassay can also detect AHLs with the common substitutions that occur on carbon 3. The assay shows various sensitivities to different AHLs. Therefore, the strength of a response does not necessarily correlate directly with the level of an AHL. There will be a strong response to relatively low levels of the cognate AHL, N-3-oxooctanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC8-HSL) and a weak response to much higher concentrations of other AHLs, like N-butyryl-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL). Furthermore, some AHLs are not detected at all by this assay, the aryl-AHLs being a case in point (5). Given these limitations, we nevertheless found that 51 isolates (40%) produced detectable AHLs. The production of AHLs was most prevalent in the Alphaproteobacteria (80% produced AHLs), whereas AHL production was detected for 20% of Betaproteobacteria and 19% of the Gammaproteobacteria (Table 1; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Among the endophytes, 34% produced detectable AHLs, and we detected AHL production by 50% of the rhizosphere isolates screened (see Table S1).

Table 1.

Census of AHL-producing isolates and isolates with luxI and luxR homologs

| Taxon | % of isolates (no. examineda) positive for AHL productionb | % of genome sequences (no. examineda) positive for: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| luxI homologc | luxR homologc | ||

| Alphaproteobacteria | 80 (44) | 100 (10) | 100 (10) |

| Betaproteobacteria | 20 (5) | 17 (5) | 60 (5) |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 19 (80) | 21 (24) | 96 (24) |

A total of 129 isolates were screened for AHL production, and 44 draft genomes were analyzed.

Determined as AHL activity in the Agrobacterium bioassay.

As defined by COG3916 for luxI homologs and pfam03472 for the AHL-binding domain of luxR homologs in the IMG JGI database (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/w/main.cgi).

As efforts to understand the role of the microbiome in the biology of P. deltoides continue, it is useful to obtain a sense of the potential for bacterial communication and signaling or cuing in this cottonwood host. We have learned that Proteobacteria are prevalent components of the microbiome (14) and that many genera of Proteobacteria utilize AHL quorum-sensing systems to control gene expression (3, 30). Furthermore, AHL quorum sensing has been shown to occur within members of many of the taxa represented in the collection of P. deltoides rhizosphere and endophyte isolates. Our analysis demonstrates that there is significant potential for AHL signaling in both the rhizosphere and endophytic environment of mature P. deltoides trees, as close to 50% of the isolates we screened produce AHLs (Table 1). Previous metagenomic analyses have revealed that there is capacity for AHL quorum sensing in soil, sewage sludge, the endophyte community of rice, and elsewhere (31–33). Furthermore, screens for AHL production by Proteobacteria isolated from rice and oat rhizospheres are similar to the results we report for the Eastern cottonwood isolates. Thirty-five percent of rice rhizosphere isolates (33) and 23% of wild oat rhizosphere (34) isolates showed AHL production. Forty percent of the isolates we screened showed AHL production. Our results support an emerging view that AHL quorum sensing is prevalent in the rhizosphere and endophyte communities of a variety of plants.

An inventory of luxI and luxR homologs in the sequenced genomes of P. deltoides-associated bacteria.

There are draft genome sequences of 44 bacterial isolates from P. deltoides (24, 25). We identified luxI and luxR homologs in these genomes by searching for AHL synthase COG category COG3916 and the transcription factor pfam AHL-binding region motif pfam03472, respectively. As expected, no AHL QS genes were found in the five available genomes from members of the Firmicutes or Bacteriodetes. Among the 39 sequenced Proteobacteria genomes, we identified 18 luxI homologs and 72 luxR homologs (Table 2; also see Table S2 in the supplemental material). One hundred percent of the Alphaproteobacteria genomes had at least one luxI and one luxR homolog. Twenty percent of the Betaproteobacteria genomes had a luxI homolog, and 60% had a luxR homolog. Of the Gammaproteobacteria genomes, 21% had a luxI homolog and 96% had a luxR homolog (Table 1). We found that nearly half of the isolates screened produce AHLs (Table 1), and these data appear to underestimate the potential for AHL production among the screened isolates, as some isolates have homologs of AHL synthases but failed to produce AHLs that could be detected with the bioassay we employed (Table 2). The potential to detect AHLs appears to be even more prevalent than the potential to produce AHLs, with the prevalence of at least one luxR homolog in about 90% of the draft genome sequences (Table 1).

Table 2.

Inventory of luxI and luxR homologs in draft genomes of P. deltoides rhizosphere and endosphere bacterial isolates

| Proteobacteria taxon, bacterial genusa and isolate identifier | Origin of isolate | No. of: |

Produces AHLb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| luxI-luxR homolog pairs | Orphan luxR homologs | |||

| Alphaproteobacteria | ||||

| Bradyrhizobium, YR681 | Endosphere | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Caulobacter, AP07 | Rhizosphere | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Novosphingobium, AP12 | Rhizosphere | 1 | 0 | Yes |

| Phyllobacterium, YR531 | Endosphere | 1 | 2 | Yes |

| Rhizobium, AP16 | Endosphere | 1 | 4 | Yes |

| Rhizobium, CF080 | Endosphere | 1 | 3 | Yes |

| Rhizobium, CF122 | Endosphere | 1 | 6 | ND |

| Rhizobium, CF142 | Endosphere | 2 | 6 | Yes |

| Rhizobium, PD01-76 | Rhizosphere | 1 | 5 | Yes |

| Sphingobium, AP49 | Endosphere | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Betaproteobacteria | ||||

| Acidovorax, CF316 | Endosphere | 0 | 2 | ND |

| Burkholderia, BT03 | Endosphere | 1 | 2 | Yes |

| Herbaspirillum, CF444 | Endosphere | 0 | 0 | ND |

| Herbaspirillum, YR522 | Endosphere | 0 | 0 | ND |

| Variovorax, CF313 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Gammaproteobacteria | ||||

| Pantoea, GM01 | Rhizosphere | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Pantoea, YR343 | Rhizosphere | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Polaromonas, CF318 | Endosphere | 0 | 0 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM16 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM17 | Endosphere | 2 | 0 | Yes |

| Pseudomonas, GM18 | Endosphere | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Pseudomonas, GM21 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM24 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM25 | Endosphere | 0 | 2 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM30 | Endosphere | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Pseudomonas, GM33 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM41 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM48 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM49 | Rhizosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM50 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM55 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM60 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM67 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM74 | Rhizosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM78 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM79 | Endosphere | 0 | 2 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM80 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM84 | Rhizosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

| Pseudomonas, GM102 | Endosphere | 0 | 1 | ND |

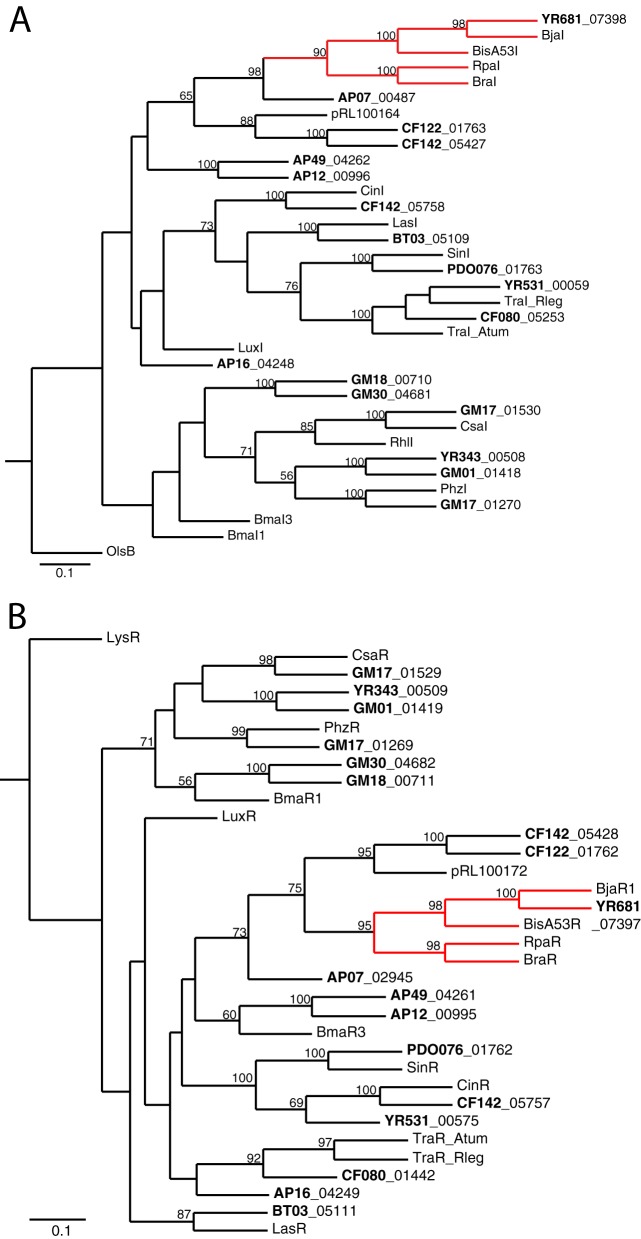

From the perspective of AHL quorum-sensing researchers, it is of interest that luxI homologs were identified in the genomes of three isolates that did not produce detectable AHLs (Table 2). These isolates included bacteria that were identified as Bradyrhizobium sp. strain YR681 and Caulobacter sp. strain AP07 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There are several possible explanations for the lack of AHL detection in cultures of these three isolates. The conditions we used to grow the isolates may not be appropriate for AHL synthesis or the encoded LuxI-type enzyme may not be functionally active, but another intriguing possibility is that these strains could produce novel AHLs that are not detected by using the Agrobacterium bioassay. We note that our phylogenetic analysis places the LuxI homologs of the three isolates within a subgroup of LuxI homologs known to catalyze the synthesis of noncanonical AHLs (AHLs with acid side chains that are not straight-chain fatty acids), such as RpaI and BjaI (Fig. 1A). Because of its relatively high homology with BjaI from B. japonicum strain USDA110 (7), we predict that the LuxI from Bradyrhizobium YR681 synthesizes isovaleryl-HSL. Although the Agrobacterium reporter responds to long-chain AHLs, it does not respond to this branched-chain acyl-HSL (7).

Fig 1.

Phylogenetic trees of LuxI-LuxR family members from Populus bacterial isolates (bold lettering) and select Proteobacteria. The scale indicates the number of substitutions per residue, and bootstrap values as the percentage of 100 samples are shown for nodes with values of 50% or greater. (A) Phylogenetic tree of LuxI AHL synthases from members of the Populus bacterial isolates and select Proteobacteria. The subfamily tree of AHL synthases that synthesize atypical QS signals is highlighted in red. OlsB, an ornithine acyltransferase, is included as an outgroup. (B) Phylogenetic tree of LuxR-type receptors from members of the Populus bacterial isolates and select Proteobacteria. The subfamily tree of LuxRs that responds to atypical QS signals is highlighted in red. LysR, a transcriptional regulator containing a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif, is included as an outgroup. Detailed information for each LuxI and LuxR homolog is given in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Cognate pairs of luxI-luxR homologs.

Generally, luxI genes and their cognate luxR genes are in close proximity. This was true in the case of almost all of the genomes with luxI homologs. There were three exceptions, Caulobacter sp. AP07, Phyllobacterium sp. strain YR531, and Rhizobium sp. strain CF080. For Caulobacter sp. AP07, the luxI (PMI01_00487) homolog-containing contig is small, and the luxI homolog is close to the end of the contig. There is only one luxR homolog in the AP07 genome (PMI01_02945), and it is also near the end of a small contig. It is possible that these genes are in close proximity in the genome, and it is equally possible that they are at a considerable distance from each other. Both Phyllobacterium sp. YR531 and Rhizobium sp. CF080 have multiple luxR homologs and a single luxI homolog. For both of these genomes, the luxI homolog (PMI41_00059 and PMI07_05253) and a luxR homolog (PMI41_00575 and PMI07_01442) are adjacent to clusters of conjugal transfer (tra and trb) genes but on separate contigs. We believe the QS gene organization in these genomes might be similar to that of A. tumefaciens, where traI and traR, which are encoded on the same Ti conjugal plasmid, are separated by a large stretch of DNA encoding opine catabolism genes and are adjacent to conjugal transfer genes (19). In fact, the Phyllobacterium sp. YR531 and Rhizobium sp. CF080 LuxI homologs are phylogenetically close to the A. tumefaciens TraI (Fig. 1A).

Phylogeny of the AHL QS genes.

We constructed phylogenetic trees of the polypeptides encoded by the luxI homologs and luxR homologs that constitute apparent AHL QS systems (Fig. 1A and B). Several of the LuxI homologs are very closely related to well-characterized AHL synthases from other bacteria. The LuxI homologs in Rhizobium sp. strain CF142 and PDO1-076 show 88% or higher amino acid identity to CinI in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae strain 3841 and SinI in Ensifer (formerly Sinorhizobium) meliloti strain 1021. The LuxI homolog in Bradyrhizobium sp. YR681 (PMI42_07398) shares 74% amino acid identity with BjaI from Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain USDA110. Pseudomonas chloroaphis strain 30-84 PhzI and CsaI are 99% identical to those in isolate GM17 (PMI20_01270 and PMI20_01418, respectively). This is not surprising, because multilocus sequence typing places isolate GM17 as a Pseudomonas sp. that is most closely related to P. chloroaphis (D. Pelletier, unpublished data). We find the phylogenies of the LuxI homologs from Bradyrhizobium sp. YR681 and Caulobacter sp. AP07 particularly interesting. These LuxI homologs are most closely related to a subclass of LuxI homologs that produce non-straight-chain fatty acyl-HSLs. Two of the known members of this subclass, RpaI and BraI, catalyze synthesis of the aryl-HSLs p-coumaroyl- and cinnamoyl-HSL (5, 6), and the third, BjaI, synthesizes isovaleryl-HSL (7). For several reasons, stated above, the production of these signals would escape detection by the A. tumefaciens bioassay, and both Bradyrhizobium sp. YR681 and Caulobacter sp. AP07 were negative in this bioassay. The predicted cognate LuxR homologs' phylogenies are shown in Fig. 1B. Consistent with the idea that these LuxR homologs coevolved with their predicted LuxI cognates, the tree is similar, although not identical, to the tree of LuxI homologs.

Orphan or solo luxR homologs.

Many of the genomes showed an excess of luxR homologs over luxI homologs or possessed one or more luxR homologs and no discernible luxI homolog (Table 2). The excess luxR homologs are orphans or solos (11). There is a limited literature on orphans, but we know that some orphan LuxR homologs respond to AHLs produced by the bacteria in which they occur (35), some respond to AHLs produced by other bacteria (12, 36), and some do not respond to AHLs, instead responding to plant-derived elicitors (37–40). All three categories are likely represented in the P. deltoides isolates for which genomic sequence information is available. There are examples of isolates, like CF122 and others, with a cognate luxI-luxR homolog pair and several additional luxR homologs. We speculate that in at least some cases, one or more of the additional luxR homologs codes for a transcription factor that interacts with a self-produced AHL. There are examples of isolates with multiple luxR homologs and without luxI homologs. The proteins these luxR homologs encode might respond to AHLs produced by other bacteria (Fig. 2), or they might respond to plant-derived compounds (Fig. 3).

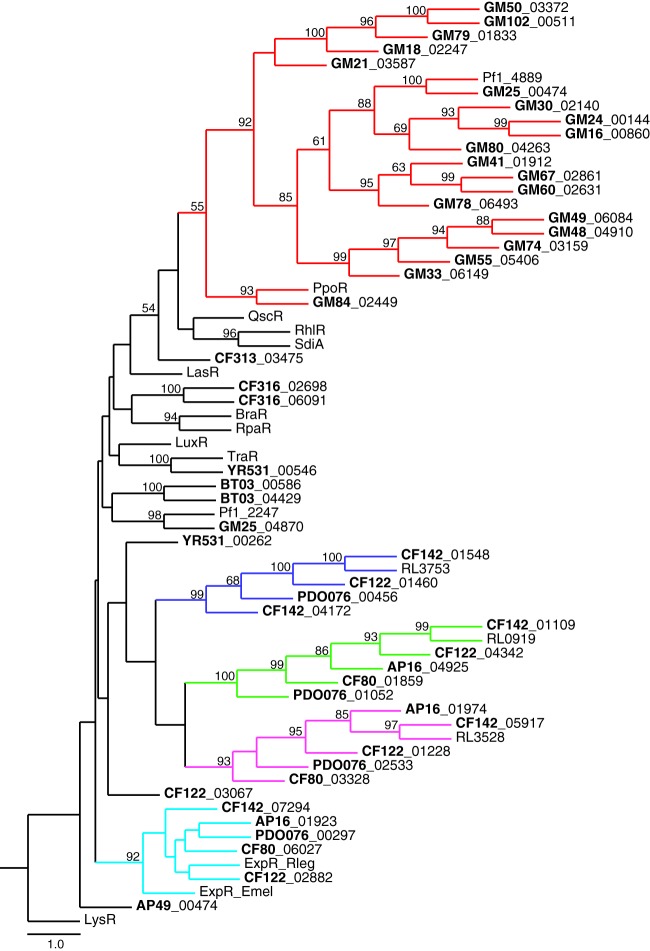

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic tree of likely non-plant-responsive solo LuxR polypeptides from Populus bacterial isolates (bold lettering) and select Proteobacteria. The scale indicates the number of substitutions per residue, and bootstrap values as the percentage of 100 samples are shown for nodes with values of 50% or greater. Each subfamily tree of solo LuxR receptors present in multiple isolates is highlighted in a separate color. The Pseudomonas subfamily PpoR homologs are highlighted in red. The Rhizobium subfamily ExpR homologs are highlighted in turquoise. Rhizobium subfamily LuxR members without a described homolog are highlighted in blue, green, and magenta. LysR, a transcriptional regulator containing a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif, is included as an outgroup. Detailed information for each LuxR homolog is given in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Fig 3.

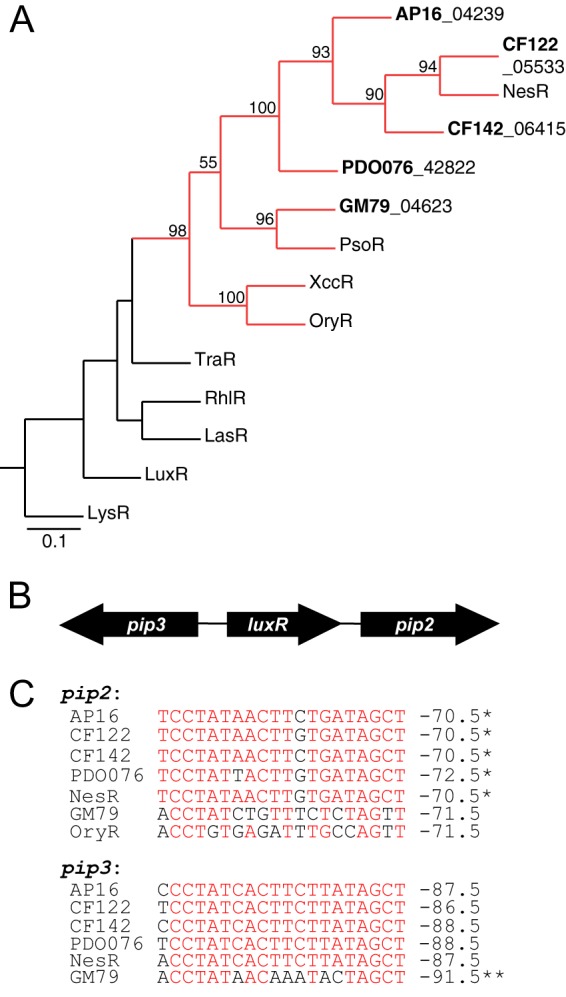

Likely plant-responsive LuxR homologs are present in Populus isolates. (A) Phylogenetic tree of selected probable plant-responsive LuxR family members from Populus bacterial isolates (bold lettering) and selected Proteobacteria. The scale indicates the number of substitutions per residue, and bootstrap values as the percentage of 100 samples are shown for nodes with values of 50% or greater. The subfamily tree of LuxR receptors that respond to a plant compound is highlighted in red. LysR, a transcriptional regulator containing a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif, is included as an outgroup. Amino acid sequence information for each LuxR homolog is detailed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. (B) Gene organization map of the plant-responsive luxR and pip genes in Pseudomonas sp. strain GM79 and Rhizobium sp. strains AP16, CF122, CF142, and PD01-076 (similar to nesR in E. meliloti strain 1021). (C) Sequence alignment of putative R-binding sites found upstream from the pip2 and pip3 genes. Site positions in which there is a majority agreement are colored red. The coordinates on the right indicate where the inverted repeat is centered relative to the ATG start site (in bp). A single asterisk indicates that the binding site overlaps the 3′ coding region of the luxR gene, and a double asterisk indicates that the binding site overlaps the 5′ coding region of the luxR gene. The oryR gene is adjacent to only a single downstream pip gene (analogous to pip2); the DNA sequence of the OryR-binding site is shown for comparison.

We have constructed phylogenetic trees of those polypeptides encoded by solo luxR homologs (Fig. 2) thought not to be responsive to plant compounds because they do not have the sequence signatures and genomic context typical of the hypothesized plant-responsive class (this class is discussed below and in the legend to Fig. 3). Presumably, these solo LuxRs respond to AHLs produced either by other bacteria or by the bacteria themselves (possible in those cases in which an isolate possesses a luxI homolog). There were four subfamilies of solo LuxRs that were present among multiple isolates of Rhizobium species, including homologs of ExpR (Fig. 2, turquoise lines) from Rhizobium leguminosarum and E. meliloti (41), indicating that each of these LuxR homologs is common among the Rhizobiaceae. There was also a Pseudomonas subfamily of solo LuxRs, which includes PpoR from Pseudomonas putida (42), which was conserved in 20 of 21 Pseudomonas isolates (Fig. 2, red lines). Although these pseudomonad solo LuxRs do not share high levels of amino acid identity (e.g., PpoR and Pf1_4889 are 29% identical and 60% similar), their genes are flanked by the same genes on the chromosome, suggesting that a ppoR homolog was present in a common ancestor of these strains. The prevalence and conservation of solo LuxR subfamilies among nearly all our isolates suggest that they play a role in the biology of these bacteria.

Orphan LuxR proteins predicted to respond to plant-derived compounds.

Our analysis not only shows a significant potential for AHL signaling in the rhizosphere and endophytic populations of P. deltoides, it also suggests a potential for a transcriptional response to specific plant-produced chemical elicitors through one of the subgroups of proteins encoded by luxR homologs. There is relatively little known about the LuxR homologs believed to respond to plant-derived elicitors; the most-studied examples are from plant-pathogenic members of the genus Xanthomonas (37, 39, 40). The LuxR homologs in these bacteria activate the expression of adjacent proline iminopeptidase (pip) genes, which are virulence factors (13). The plant metabolites that serve as ligands for these LuxR homologs have yet to be elucidated. Other orphan LuxR homologs predicted to respond to plant metabolites have been identified on the basis of protein sequence and the context of neighboring genes (13). The genes that code for these predicted plant-responsive LuxR homologs are flanked by pip homologs. Members of this family also code for polypeptides with substitutions in one or two of the conserved residues in the AHL-binding region (Y61W [Y mutated to W at position 61] and/or W57M) (reviewed in reference 13). We identified five luxR homologs with the above-mentioned characteristics (Fig. 3A), four of which are in Rhizobium species genomes and one in a pseudomonad. All five of these genes are embedded between pip2 and pip3 homologs in an organization similar to that of E. meliloti nesR (Fig. 3B), a gene that has been reported to be involved in stress adaptation and competition during root nodule development (43). There are inverted repeat DNA elements found in the regions upstream from pip2 and pip3 (Fig. 3C). Similar inverted repeats occur in the pip regions of plant-pathogenic Xanthomonas sp. Plant-beneficial Pseudomonas fluorescens strains have similarly organized pip loci except that they lack the inverted repeat sequences. Evidence suggests that the inverted repeats are binding sites for LuxR homologs (13).

Taken as a whole, our results support an emerging view that AHL quorum sensing is prevalent in the rhizosphere and endophyte communities of a variety of plants. Our work extends the knowledge base not only to include Eastern cottonwood but also to show that there is a great capacity for AHL signal production, which was universal among the Alphaproteobacteria isolates we examined and lower in the Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria isolates. Most of the isolates we examined showed a capacity for AHL recognition by orphan or solo LuxR homologs even if there was not a capacity for AHL production. Our analysis also supports the view that some Proteobacteria possess LuxR homologs that may be capable of responding to plant metabolites. We are now poised to begin to understand what roles AHL quorum sensing plays in the biology of the Eastern cottonwood and other plants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathan Ahlgren for his assistance in phylogenetic tree analyses.

This research was sponsored by the Genomic Science Program, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research, as part of the Plant Microbe Interfaces Scientific Focus Area (http://pmi.ornl.gov). Oak Ridge National Laboratory is managed by UT-Battelle LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725.

A.L.S., C.R.L., R.P.M., D.A.P., T.-Y.S.L., and P.K.L. performed the experiments. A.L.S., D.A.P., C.S.H., and E.P.G analyzed the data. A.L.S., C.S.H., and E.P.G wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 July 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01417-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Engebrecht J, Silverman M. 1984. Identification of genes and gene products necessary for bacterial bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:4154–4158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Case RJ, Labbate M, Kjelleberg S. 2008. AHL-driven quorum-sensing circuits: their frequency and function among the proteobacteria. ISME J. 2:345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waters CM, Bassler BL. 2005. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:19–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead NA, Barnard AM, Slater H, Simpson NJ, Salmond GP. 2001. Quorum-sensing in gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbial Rev. 25:365–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaefer AL, Greenberg EP, Oliver CM, Oda Y, Huang JJ, Bittan-Banin G, Peres CM, Schmidt S, Juhaszova K, Sufrin JR, Harwood CS. 2008. A new class of homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals. Nature 454:595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahlgren NA, Harwood CS, Schaefer AL, Giraud E, Greenberg EP. 2011. Aryl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in stem-nodulating photosynthetic bradyrhizobia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:7183–7188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindemann A, Pessi G, Schaefer AL, Mattmann ME, Christensen QH, Kessler A, Hennecke H, Blackwell HE, Greenberg EP, Harwood CS. 2011. Isovaleryl-homoserine lactone, an unusual branched-chain quorum-sensing signal from the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:16765–16770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochsner UA, Reiser J. 1995. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:6424–6428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson JP, Gray KM, Passador L, Tucker KD, Eberhard A, Iglewski BH, Greenberg EP. 1994. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:197–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesci EC, Iglewski BH. 1997. The chain of command in Pseudomonas quorum sensing. Trends Microbiol. 5:132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patankar AV, Gonzalez JE. 2009. Orphan LuxR regulators of quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:739–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperandio V. 2010. SdiA sensing of acyl-homoserine lactones by enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) serotype O157:H7 in the bovine rumen. Gut Microbes 1:432–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez JF, Venturi V. 2012. A novel widespread interkingdom signaling circuit. Trends Plant Sci. 18:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottel NR, Castro HF, Kerley M, Yang Z, Pelletier DA, Podar M, Karpinets T, Uberbacher E, Tuskan GA, Vilgalys R, Doktycz MJ, Schadt CW. 2011. Distinct microbial communities within the endosphere and rhizosphere of Populus deltoides roots across contrasting soil types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5934–5944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gehring CA, Mueller RC, Whitham TG. 2006. Environmental and genetic effects on the formation of ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal associations in cottonwoods. Oecologia 149:158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taghavi S, et al. 2009. Genome survey and characterization of endophytic bacteria exhibiting a beneficial effect on growth and development of poplar trees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:748–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuskan GA, et al. 2006. The genome of the black cottonwood, Populus tricocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313:1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sannigrahi P, Ragauskas AJ, Tuskan GA. 2010. Poplar as feedstock for biofuels: a review of compositional characteristics. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 4:209–226 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuqua WC, Winans SC. 1994. A LuxR-LuxI type regulatory system activates Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer in the presence of a plant tumor metabolite. J. Bacteriol. 176:2796–2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirhonen M, Flego D, Heikinheimo R, Palva ET. 1993. A small diffusible signal molecule is responsible for the global control of virulence and exoenzyme production in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora. EMBO J. 12:2467–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinones B, Dulla G, Lindow SE. 2005. Quorum sensing regulates exopolysaccharide production, motility, and virulence in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18:682–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schripsema J, de Rudder KE, van Vliet TB, Lankhorst PP, de Vroom E, Kijne JW, van Brussel AA. 1996. Bacteriocin small of Rhizoobium leguminosarum belongs to the class of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone molecules, known as autoinducers and as quorum sensing co-transcription factors. J. Bacteriol. 178:366–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray KM, Pearson JP, Downie JA, Boboye BE, Greenberg EP. 1996. Cell-to-cell signaling in the symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium Rhizobium leguminosarum: autoinduction of a stationary phase and rhizosphere-expressed genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:372–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown SD, Utturkar SM, Klingeman DM, Johnson CM, Martin SL, Land ML, Lu TS, Schadt CW, Doktycz MJ, Pelletier DA. 2012. Twenty-one Pseudomonas genomes and nineteen genomes from diverse bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere and endosphere of Populus deltoides. J. Bacteriol. 194:5991–5993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown SD, Klingeman DM, Lu TS, Johnson CM, Utturkar SM, Land ML, Schadt CW, Doktycz MJ, Pelletier DA. 2012. Draft genome sequence of Rhizobium sp. strain PDO1-076, a bacterium isolated from Populus deltoides. J. Bacteriol. 194:2383–2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weston DJ, Pelletier DA, Morrell-Falvey JL, Tschaplinski TJ, Jawdy SS, Lu TY, Allen SM, Melton SJ, Martin MZ, Schadt CW, Karve AA, Chen JG, Yang X, Doktycz MJ, Tuskan GA. 2012. Pseudomonas fluorescens induces strain-dependent and strain-independent host plant responses in defense networks, primary metabolism, photosynthesis, and fitness. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25:765–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer AL, Hanzelka BL, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. 2000. Detection, purification and structural elucidation of the acylhomoserine lactone inducer of Vibrio fischeri luminescence and other related molecules. Methods Enzymol. 305:288–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, Chai Y, Zhong Z, Li S, Winans SC. 2003. Agrobacterium bioassay strain for ultrasensitive detection of N-acylhomoserine lactone-type quorum-sensing molecular: detection of autoinducers in Mesorhizobium huakuii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6949–6953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao M, Chen H, Eberhard A, Gronquist MR, Robinson JB, Connolly M, Teplitski M, Rolfe BG, Bauer WD. 2007. Effects of AiiA-mediated quorum quenching in Sinorhizobium meliloti on quorum-sensing signals, proteome patterns, and symbiotic interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20:843–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuqua C, Greenberg EP. 2002. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signaling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao Y, Winans SC, Glick BR, Charles TC. 2010. Identification and characterization of new LuxR/LuxI-type quorum sensing systems from metagenomic libraries. Environ. Microbiol. 12:103–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasuno E, Kimura N, Fujita MJ, Nakatsu CH, Kamagata Y, Hanada S. 2012. Phylogenetically novel LuxI/LuxR-type quorum sensing systems isolated using a metagenomic approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:8067–8074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sessitsch A, Hardoim P, Doring J, Weilharter A, Krause A, Woyke T, Mitter B, Hauberg-Lotte L, Friedrich F, Rahalkar M, Hurek T, Sarkar A, Bodrossy L, van Elsas JD, Reinhold-Hurek B. 2012. Functional characteristics of an endophyte community colonizing rice roots as revealed by metagenomic analysis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25:28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeAngelis KM, Lindow SE, Firestone MK. 2008. Bacterial quorum sensing and nitrogen cycling in rhizosphere soil. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 6:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JH, Lequette Y, Greenberg EP. 2006. Activity of purified QscR, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa orphan quorum-sensing transcription factor. Mol. Microbiol. 59:602–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyszel JL, Soares JA, Swearingen MC, Lindsay A, Smith JN, Ahmer BM. 2010. E. coli K-12 and EHEC genes regulated by SdiA. PLoS One 5:e8946. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Jia Y, Wang L, Fang R. 2007. A proline iminopeptidase gene upregulated in plant by a LuxR homologue is essential for pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Mol. Microbiol. 65:121–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramoni S, Gonzalez JF, Johnson A, Pechy-Tarr M, Rochat L, Paulsen I, Loper JE, Keel C, Venturi V. 2011. Bacterial subfamily of LuxR regulators that respond to plant compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:4579–4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferluga S, Bigirimana J, Hofte M, Venturi V. 2007. A LuxR homologue of Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae is required for optimal rice virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8:529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chatnaparat T, Prathuangwong S, Ionescu M, Lindow SE. 2012. XagR, a LuxR homolog, contributes to the virulence of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines to soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25:1104–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards A, Frederix M, Wisniewski-Dye F, Jones J, Zorreguieta A, Downie JA. 2009. The cin and rai quorum-sensing regulatory systems in Rhizobium leguminosarum are coordinated by ExpR and CinS, a small regulatory protein coexpressed with CinI. J. Bacteriol. 191:3059–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramoni S, Venturi V. 2009. PpoR is a conserved unpaired LuxR solo of Pseudomonas putida which binds N-acyl homoserine lactones. BMC Microbiol. 9:125. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patankar AV, Gonzalez JE. 2009. An orphan LuxR homolog of Sinorhizobium meliloti affects stress adaptation and competition for nodulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:946–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.