Abstract

Sulfolobus species have become the model organisms for studying the unique biology of the crenarchaeal division of the archaeal domain. In particular, Sulfolobus islandicus provides a powerful opportunity to explore natural variation via experimental functional genomics. To support these efforts, we further expanded genetic tools for S. islandicus by developing a stringent positive selection for agmatine prototrophs in strains in which the argD gene, encoding arginine decarboxylase, has been deleted. Strains with deletions in argD were shown to be auxotrophic for agmatine even in nutrient-rich medium, but growth could be restored by either supplementation of exogenous agmatine or reintroduction of a functional copy of the argD gene from S. solfataricus P2 into the ΔargD host. Using this stringent selection, a robust targeted gene knockout system was established via an improved next generation of the MID (marker insertion and unmarked target gene deletion) method. Application of this novel system was validated by targeted knockout of the upsEF genes involved in UV-inducible cell aggregation formation.

INTRODUCTION

Sulfolobus islandicus is a hyperthermophilic archaeon that inhabits solfataric geothermal springs and grows optimally at about 65 to 85°C and pH 2 to 4. It was first isolated from acidic springs located in Iceland by Zillig and coworkers in 1994 (1). A later study showed that S. islandicus strains were also widely distributed in hot springs of Yellowstone National Park and Lassen Volcanic National Park in the United States, as well as Mutnovsky Volcano and the Uzon Caldera/Geyser Valley region on the Kamchatka Peninsula in eastern Russia, with evidence that this microorganism is geographically isolated by large distances between hot springs (2). S. islandicus is of special interest as it serves as a model system for understanding fundamental cellular processes, particularly DNA replication, repair, and recombination, in the crenarchaeal division of the archaeal domain. Utilization of S. islandicus in this way will require a powerful genetic system for in vivo analysis.

Since the establishment of electroporation-based transformation protocol in Sulfolobus by Schleper et al. in 1992 (3), great efforts have been made to develop targeted gene knockout systems in this genus. A major breakthrough was the development of a lactose selection-based targeted gene disruption system via homologous recombination in a spontaneous lacS (encoding beta-galactosidase) deletion mutant derived from Sulfolobus solfataricus 98/2 (4). The inability to use lactose as a sole carbon and energy source meant that the lactose selection system was not expanded into other closely related Sulfolobus members, i.e., Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and S. islandicus (5). However, in 2009, She and coworkers first reported an unmarked gene knockout system relying on uracil prototrophic selection and 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) counterselection in a strain with a large spontaneous pyrEF deletion derived from S. islandicus REY15A (6, 7). The pyrEF/5-FOA bidirectional system has also been established for allelic exchange as well as unmarked gene deletion in S. acidocaldarius and S. islandicus LAL14/1 (8–10). In combination with the indicative marker gene lacS (not used for lactose selection here), versatile gene deletion methodologies have been established in S. islandicus REY15A and applied for functional analysis of genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and recombination (11–13). However, uracil-based selection cannot be efficiently employed in other S. islandicus strains due to the interference caused by background growth of the pyrEF-deficient strain on solid medium (14). Recently, the genetic system in S. islandicus was further improved by developing a broadly applicable antibiotic marker based on overexpression of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (CoA) reductase gene (hmgA) to confer resistance to simvastatin (15). Relying on the simvastatin resistance marker, a shuttle vector-based transformation system and gene disruption system has been established in S. islandicus REY15A and S. islandicus M.16.4, respectively (14, 15). However, posttransformation, simvastatin-resistant (Simr) cells usually exhibit significantly retarded growth, and it is therefore necessary to enrich Simr cells in liquid medium containing simvastatin prior to direct isolation of Simr colonies on plates (14). In addition, a large number of spontaneous Simr mutants can easily be generated due to native gene amplification, as reported for genetic manipulation of Thermococcus kodakarensis and Pyrococcus furiosus (16–18) making simvastatin resistance difficult to use as a stringent selective marker.

Despite the fact that pyrEF and simvastatin resistance markers have been applied in genetic studies for hyperthermophilic crenarchaea S. islandicus, a stringent positive selection method is still lacking. Here, we aimed to further develop versatile genetic markers in S. islandicus, particularly stringent positive selectable markers to be utilized in chromosomal gene deletion. As a candidate, we deleted the arginine decarboxylase-encoding gene (argD), involved in polyamine biosynthesis, which has been previously demonstrated to result in agmatine auxotrophy in the euryarchaea T. kodakaraensis and P. furiosus (19–21). We used this novel selection marker in combination with two existed pyrEF and lacS markers to improve the recently developed MID (marker insertion and unmarked target gene deletion) methodology (11), which was validated by rapidly constructing upsEF mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and cultivation conditions.

S. islandicus M.16.4 and its derivatives, described in Table 1, were routinely cultivated in a tissue culture flask (Corning) at 75 to 78°C without shaking. DT medium (pH 3.5), used for strain cultivation, contained components as follows (in 1 liter Milli-Q H2O): 1× basal salts (K2SO4, 3.0 g; NaH2PO4, 0.5 g; MgSO4, 0.145 g; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.1 g), 20 μl trace mineral stock solution (3.0% FeCl3, 0.5% CoCl2 · 6H2O, 0.5% MnCl2 · 4H2O, 0.5% ZnCl2, and 0.5% CuCl2 · 2H2O), 0.1% (wt/vol) dextrin, and 0.1% (wt/vol) EZMix-N-Z-amine A. Nutrient-rich DY medium was prepared by replacing EZMix-N-Z-amine with tryptone. To solidify plates, prewarmed 2× DT or DY medium supplemented with 20 mM MgSO4 and 7 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O was mixed with an equal volume of fresh boiling 1.7% Gelrite and then immediately poured into petri dishes. For growth of uracil- and agmatine-auxotrophic strains, 20 μg/ml uracil and 20 μg/ml agmatine were added to DT or DY medium, respectively. Particularly, 50 μg/ml 5-FOA and 1 mg/ml agmatine were used for counterselection of mutants. Escherichia coli Top10 (Invitrogen) was used for general molecular cloning manipulation and grown on Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to the medium when required.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmids | Genotype and/or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. solfataricus P2 | Wild type | DSMZ |

| S. islandicus | ||

| M.16.4 | Isolated from Mutnovsky Volcano Region of Kamchatka (Russia), wild type | 26 |

| RJW002 | ΔpyrEF; the complete pyrEF gene was deleted from S. islandicus M.16.4 | 14 |

| RJW003 | ΔpyrEF ΔlacS; lacS was deleted from S. islandicus RJW002 | This study |

| RJW004 | ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS; argD was deleted from S. islandicus RJW003 | This study |

| RJW005 | ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS::SsoargD; SsoargD was integrated at the lacS locus of S. islandicus RJW004 | This study |

| pCY-SsoargD-T | S. islandicus RJW004 harboring shuttle vector pCY-SsoargD | This study |

| RJW006 | ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS ΔupsEF; upsEF was deleted from S. islandicus RJW004 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRJW1 | pUC19 carrying the simvastatin resistance marker (Simr) | 14 |

| pRJW2 | Based on pRJW1; Simr was replaced by the SsopyrEF marker at the NcoI and MluI sites | This study |

| pRJW3 | pRJW2 carrying the lacS expression cassette from S. solfataricus P2 | This study |

| pRJW8 | pRJW3 carrying the argD expression cassette from S. solfataricus P2 | This study |

| pPIS-lacS | lacS knockout plasmid, pRJW2 carrying Up- and Dn-arm of lacS | This study |

| pPIS-argD | argD knockout plasmid, pRJW3 carrying Up- and Dn-arm of argD | This study |

| pC-SsoargD | SsopyrEF marker in pKlacS-Simr was replaced by SsoargD marker | 14 and this study |

| pMID-upEF | upsEF knockout plasmid, pRJW8 carrying Up- and Dn-arm of upsEF and a partial upsF (Tg-arm) | This study |

| pSSR/lacS | pRN2-based Sulfolobus-E. coli shuttle vector carrying lacS marker and Simr | 15 |

| pCY-SsoargD | pSSR/lacS carrying SsoargD marker | This study |

Plasmid construction and DNA manipulation.

The plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1, and the PCR primers used are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

(i) Construction of cloning vectors carrying various marker cassettes: pRJW2, pRJW3, and pRJW8.

The pyrEF gene driven by its native promoter-terminator system (∼1.86 kb) was amplified from S. solfataricus P2 using primer set SsopyrEF-F/R, which contained NcoI and MluI restriction sites, respectively. The NcoI/MluI-digested PCR products were used to replace the simvastatin resistance marker (Simr) from pRJW1 (14) at corresponding sites, generating pRJW2.

Construction of pRJW3, an ∼1.9-kb lacS expression cassette composed of lacS together with its native promoter and terminator, was amplified from S. solfataricus P2 using primer set SsolacS-F/R and inserted into pRJW2 at the SalI and MluI sites. To construct pRJW8, an ∼0.75-kb argD expression cassette containing argD and its native promoter and terminator was amplified from S. solfataricus P2 using primer set SsoargD-F/R, introducing NcoI and EagI-SphI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The resulting PCR products were digested with NcoI and SphI and then inserted into pRJW3 at the same sites, yielding pRJW8.

(ii) Construction of lacS, argD, and upsEF knockout plasmids.

A plasmid integration and segregation (PIS) method (7) was employed to construct lacS and argD knockout plasmids. In brief, 0.6- to 0.8-kb up- and downstream flanking regions of lacS were amplified from S. islandicus M.16.4 using primer pairs lacS-Up-F/R and lacS-Dn-F/R, respectively. The two PCR products were digested with MluI/PstI and PstI/SalI, respectively, and then cloned into pRJW2 at MluI and SalI sites by a triple-ligation strategy, generating the lacS knockout plasmid (pPIS-lacS) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Similarly, 0.8- to 1.0-kb up- and downstream flanking regions of argD were amplified from S. islandicus M.16.4 using primer pairs argD-Up-F/R and argD-Dn-F/R, respectively. The two PCR products were purified, digested with BamHI/KpnI and KpnI/SalI, and then cloned into pRJW3 at BamHI and SalI sites by triple ligation, generating the argD knockout plasmid (pPIS-argD).

A recently developed marker insertion and unmarked target gene deletion (MID) method (11) was utilized for upsEF knockout plasmid construction. For this, 0.8- to 0.9-kb up- and downstream flanking regions of upsEF and a partial upsF (Tg-arm, ∼1.0 kb) were amplified from S. islandicus M.16.4 using primer pairs upsEF-Up-F/R, upsEF-Dn-F/R, and upsEF-Tg-F/R, respectively. SalI-KpnI-digested Up-arm and KpnI-BamHI-digested Dn-arm were cloned into pRJW8 at SalI and BamHI sites by triple ligation, yielding pKupsEF-LR. Subsequently, SphI-EagI-digested Tg-arm was inserted at the same site of pKupsEF-LR, generating the upsEF knockout plasmid (pMID-upsEF).

(iii) Construction of an argD-complemented plasmid and argD-based shuttle vector.

Two SsoargD marker cassettes with different restriction sites were amplified by primer sets SsoargD-F/R1 and SsoargD-F2/R2 from S. solfataricus P2, introducing NcoI/MluI and SalI/XmaI sites, respectively. The simvastatin resistance marker (Simr) in pKlacS-Simr (14) was replaced by a SsoargD marker at the NcoI and MluI sites, generating the argD-complemented plasmid (pC-SsoargD). The SalI-XmaI-digested SsoargD marker was inserted into Sulfolobus-E. coli shuttle vector pSSR/lacS (15) at the corresponding sites, giving rise to pCY-SsoargD.

Transformation of S. islandicus.

S. islandicus competent cells were prepared following the procedures described previously (22), and the final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of cells was adjusted to 10 to 15. Circular, linearized knockout plasmids (∼1 μg) or shuttle vectors (0.5 to 1 μg) were transformed into 50 μl S. islandicus competent cells by electroporation using the Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad) with input parameters of 1.2 kV, 25 μF, and 600 Ω in 1 mm cuvettes (Bio-Rad). The constant time was basically in the range of 13.5 to 14.5 ms. After electroporation, transformed cells were immediately regenerated in 800 μl incubation solution [0.3% (NH4)2SO4, 0.05% K2SO4, 0.01% KCl, 0.07% glycine, pH 5] at 75°C for 30 min without shaking. For transformation using pyrEF as a selectable marker, transformed cells were usually incubated in defined DT liquid medium for about 2 weeks and then spread onto DT plates. For transformation using argD as a selectable marker, 850 μl transformed cells were mixed with top gel solution (5 ml DY rich medium, 5 ml 0.4% Gelrite) and then poured onto corresponding bottom plates (0.85% Gelrite) by overlay cultivation. Plates were incubated at 75 to 78°C for 10 to 12 days in sealed plastic bags or boxes. When an indicative marker (lacS) was contained in the plasmids used for transformation, 2 mg/ml X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) solution was used to spray single colonies that appeared on the plates.

PCR screening of transformants and mutants.

Single colonies on the plates were picked and suspended in 100 μl DT medium. The colonies were analyzed by PCR amplification using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 25-μl reaction mixtures (with 2 μl cells as DNA template) under the following conditions: 94°C for 5 min; 34 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 to 30 s per kb for amplification; and a final extension for 10 min. The PCR products were assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Growth curve of S. islandicus.

When comparing the growth of the S. islandicus wild-type strain and the argD deletion mutant, the cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Cell debris was washed using DT medium three times by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min in order to remove the residual agmatine completely, and then the cells were resuspended in DT medium. The proper volume of cells was inoculated into 45 ml DTU (DT containing uracil) or DTU-A (DTU containing agmatine) liquid medium by careful calculation to make the initial OD600 of each sample 0.008. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical cell density at 600 nm on a CO8000 cell density meter (WPA, Cambridge, United Kingdom) every 12 h.

UV irradiation and microscopy analysis of S. islandicus cells.

UV treatment (75-J/m2 UV dose, CL-1000 UV cross-linker) of S. islandicus cells was conducted primarily according to a procedure described previously (23). Ten microliters of UV-treated or untreated cells was carefully taken after 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 8 h of incubation and used for microscopy analysis of cell aggregation following a protocol developed previously (24).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of a ΔargD mutation in an S. islandicus RJW003 (ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) background.

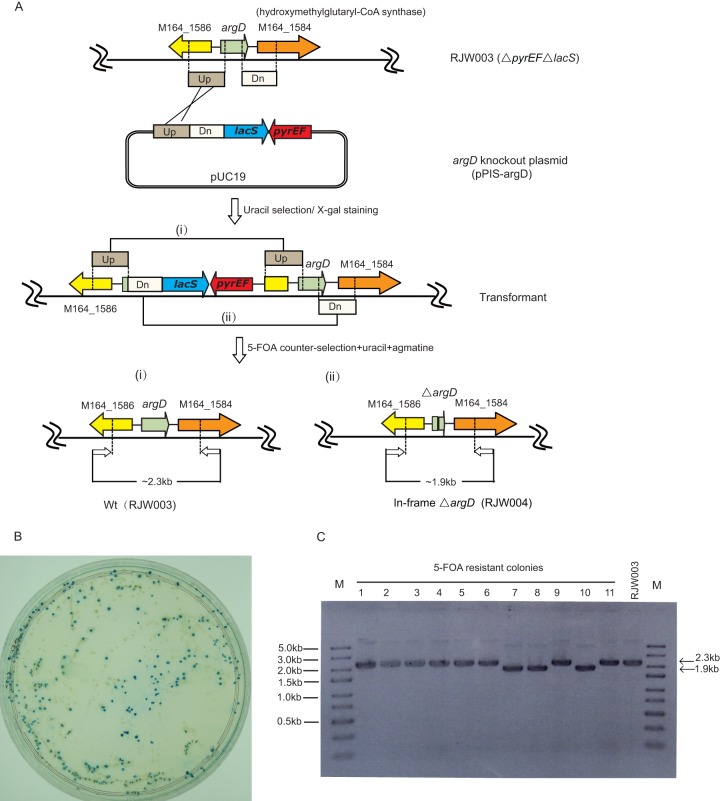

SSO0536 has been identified to have the activity of arginine decarboxylase, which catalyzes l-arginine to produce agmatine in S. solfataricus P2 (25). Using this gene as a query, we identified that SisM164_1585 in the S. islandicus M.16.4 genome shares 98% identity with SSO0536 by Blastp analysis (26). In order to investigate the function of SisM164_1585 genetically and exploit the possibility to develop it as a positive selectable marker in S. islandicus, an in-frame unmarked deletion mutation of SisM164_1585 (named argD in our study) was first generated in background strain S. islandicus RJW003 (ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) by taking advantage of a modified PIS method, utilizing the hybrid marker pyrEF-lacS (Fig. 1A) (7). Because pyrEF-deficient strains exhibited good growth on solid Gelrite plates, transformed cells were first enriched in uracil-free liquid medium for 2 to 3 weeks and then spread on plates. As shown in Fig. 1B, background growth (LacS−, white colonies) occurred on the solid DT plates even after a long enrichment process for uracil prototrophs in liquid medium prior to plating, clearly showing that the trace uracil in Gelrite, the polymer used to solidify the medium, was the key factor that decreased the strictness for uracil-based selection.

Fig 1.

In-frame deletion of argD via a modified plasmid integration and segregation (PIS) method. (A) Schematic of the modified PIS strategy. A circular argD knockout plasmid (pPIS-argD) containing hybrid maker pyrEF-lacS and upstream and downstream flanking region of argD was transformed into genetic host RJW003 (ΔpyrEFΔlacS). The pPIS-argD was integrated into the host chromosome via single crossover at either Up- or Dn-arm, and resulting uracil prototroph transformants can be selected on uracil-free medium. A second single crossover at Up- or Dn-arm generated either revertants or argD deletion mutants in the presence of 5-FOA. (B) X-Gal staining of pPIS-argD-transformed cells. Transformed cells were enriched in uracil-free liquid medium for three rounds (5 days for each round) and then spread on a uracil-free plate. Positive transformants and background colonies were distinguished by X-Gal staining. (C) PCR screening of argD deletion mutants. 5-FOA-resistant colonies were screened by PCR using argD flankP-F/R as primers. Lane M was loaded with the GeneRuler Express DNA ladder (Thermo Scientific).

Three blue colonies from the plates were identified by PCR using the primer set argD-flankP-F/R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and one positive transformant, designated pPIS-argD-T, was then used for counterselection on plates containing uracil, 5-FOA, and 1 mg/ml agmatine. Eleven 5-FOAr colonies were randomly selected and identified by PCR with primers argD-flankP-F/R. As shown in Fig. 1C, three colonies appeared to have the expected ∼0.4-kb deletion in the argD locus (lanes 7, 8, and 10), while the remaining colonies exhibited the same phenotype as the background strain (RJW003), apparently generated by reversion. One correct ΔargD recombinant, designated S. islandicus RJW004, was purified three times by streaking and then used for further studies.

argD is essential for S. islandicus cell growth.

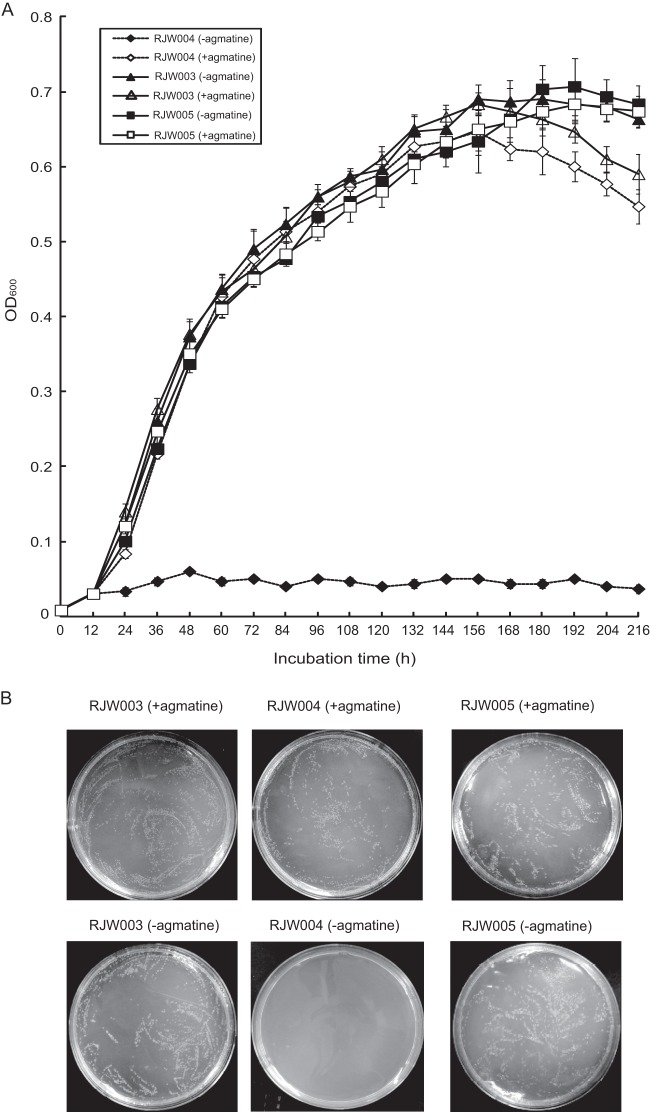

The growth of the ΔargD mutant (RJW004, ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) was first examined in DTU (DT medium containing uracil) liquid medium in the presence or absence of agmatine. As seen in Fig. 2A, with the concentration of agmatine tested (0.02 mg/ml), the wild-type strain (RJW003, ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) did not show any obvious differences with or without agmatine, whereas the ΔargD mutant had no growth in the absence of agmatine even after 9 days of incubation. Growth of the ΔargD mutant was restored by addition of 0.02 mg/ml agmatine, clearly indicating that argD plays a key role in the biosynthesis of agmatine, which is indispensable for growth of S. islandicus strains. As seen in Fig. 2B, for the wild-type strain, no significant differences were observed with or without agmatine on solid medium, and for the ΔargD mutant, no colonies were formed on the plates without supplementation of exogenous agmatine. Again, growth of the mutant strain occurred when agmatine was added to solid medium. The growth of the ΔargD strain was also tested in DYU (DY medium containing uracil) nutrient-rich liquid or solid medium, and very similar results were obtained, suggesting that no residual agmatine existed in commercial tryptone or Gelrite.

Fig 2.

Growth of RJW003 (ΔpyrEF ΔlacS), RJW004 (ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS), and argD-complemented strain RJW005 in liquid medium (A) and plate medium (B). All S. islandicus cells were cultured in DT medium. When needed, uracil and/or agmatine was added at final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Cells were washed three times and resuspended in DT medium. For growth in liquid medium (A), S. islandicus cells were inoculated at an initial OD600 of 0.008 for each sample, and cultures were taken every 12 h for monitoring. Error bars represented standard deviations from three independents experiments. For plating (B), serial 1:10 dilutions of cells were made, and 200 μl diluted cells (10−4) were spread on a DTU or DTU-A plate directly for 10 to 12 days; 200 μl undiluted RJW004 cells were spread on a DTU plate.

Genetic complementation assay of argD mutants.

ΔargD mutants were genetically complemented by introducing a copy of the previously characterized argD gene (SSO0536) from S. solfataricus P2 on plasmid pC-SsoargD with flanking regions of the M.16.4 lacS gene (Fig. 3A). When this plasmid (linearized by SphI) was transformed into host strain RJW004, single colonies could be readily formed on agmatine-free plates after 7 to 10 days of incubation, while no background colonies appeared without any plasmid transformation (Fig. 3B). PCR analysis of six agmatine-prototrophic colonies by primer set lacS-flankP-F/R showed that the SsoargD marker was inserted into the lacS locus in S. islandicus RJW004 via double-crossover homologous recombination (Fig. 3C). One correct recombinant, named RJW005, was purified three times and used for growth analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, RJW005 can grow well both in liquid medium and on solid plates without agmatine. Transformation/recombination efficiencies were also evaluated by performing three independent experiments using linearized pC-SsoargD, and it was estimated that each microgram of DNA can generate about 20 to 30 colonies.

Fig 3.

Genetic complementation of argD deletion strains. (A) Schematic diagram of argD complementation. Plasmid pC-SsoargD, containing the SsoargD marker and upstream and downstream flanking regions of lacS, was designed to allow simple integration of the argD marker on the RJW004 chromosome at the lacS locus via double-crossover homologous recombination. (B) Transformants were selected on rich medium by relying on agmatine prototrophy selection. (C) PCR analysis of argD complementation strains. The lacS loci in strains M.16.4 (wild type), RJW004 (ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS), and RJW005 (ΔargDΔpyrEFΔlacS::SsoargD) were checked by PCR using lacS flankP-F/R as primer pairs.

Interestingly, using the S. islandicus ArgD protein (SisM164_1585) as a query sequence for Blastn searching in genomes of several well-studied crenarchaea, including S. solfataricus, S. acidocaldarius, Sulfolobus tokodaii, Metallosphaera sedula, and Acidianus hospitalis W1 (27–31), a homologue of the ArgD protein with a high identity range, from 74% to 98%, was found. Compared with the distantly related crenarchaeon Aeropyrum pernix (which optimally grows at 95°C), there was 49% sequence identity with ArgD (32). These findings suggested that ArgD, involved in the polyamine biosynthesis pathway, was relatively conserved and that application of the argD gene as a selectable marker could potentially be expanded in these hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Most importantly, the extremely stringent trait of the agmatine-based selection system used even in nutrient-rich medium will not only completely eliminate the background growth of the uracil-based selection system in S. islandicus, S. acidocaldarius, and M. sedula (8, 14, 33) but also definitely accelerate the isolation of transformants, especially in genetic manipulation of S. solfataricus (4, 22).

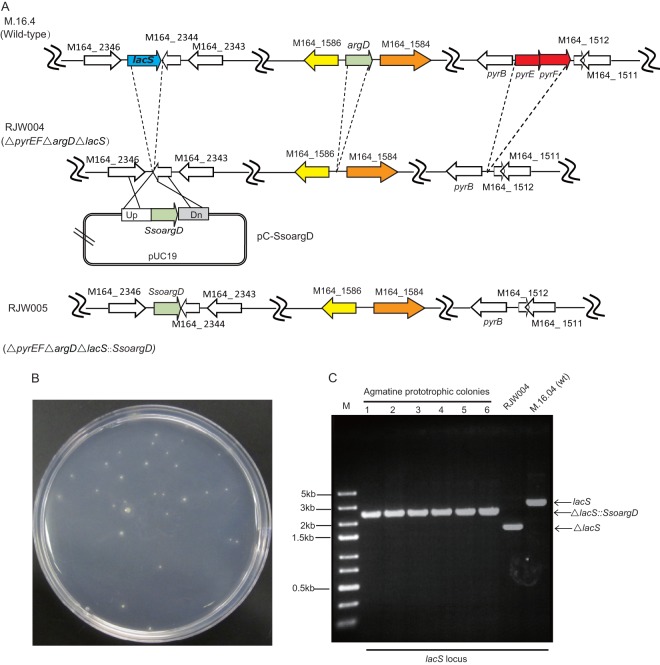

Transformation of Sulfolobus-E. coli shuttle vector based on agmatine selection.

The development of the stringent agmatine-based selection system allowed us to make an accurate evaluation of the transformation efficiency in this organism for the first time. To construct the vector harboring the SsoargD marker, the Sulfolobus-E. coli shuttle vector pSSR/lacS (15, 34) was further modified by inserting the SsoargD marker at corresponding sites, yielding pCY-SsoargD (Fig. 4A). One microgram of plasmid DNA (<5 μl) was used to transform host strain RJW004, followed by incubating with either basal salt solution or three other different recovery solutions: Milli-Q water, 20 mM sucrose, and β-alanine–malate solution (22, 35). It was found that the highest number of transformants was obtained with β-alanine–malate buffer (data not shown), and this regeneration buffer was further used to evaluate the transformation efficiency of pCY-SsoargD. Figure 4B shows one example of transformation results with pCY-SsoargD on X-Gal-stained DY nutrient-rich plates containing uracil. As the lacS gene was also contained in this plasmid, colonies on the plates were then stained with X-Gal solution, and it turned out that each colony could be stained blue, as expected. Plasmid DNAs were isolated from two random blue transformants (named pCY-SsoargD-T) and digested with HindIII restriction enzyme, and they showed the same size patterns as the plasmid DNA purified from E. coli strains (Fig. 4C), indicating that vectors were not integrated into host chromosome but replicated independently. We further retransformed the plasmid isolated from S. islandicus back into E. coli strains, and HindIII digestion analysis of 10 samples showed that they had the exact same pattern mentioned above (data not shown). Two independent transformation experiments were performed by using the optimized protocol, and the transformation efficiency was estimated in the range of 102 to 104 colonies/μg plasmid DNA (Fig. 4D). This result is lower than the results reported by Deng et al. for S. islandicus REY15A based on uracil prototrophic selection (104 to 106 colonies/μg plasmid DNA) (7) but are comparable to those of Zheng et al. (∼104 colonies/μg plasmid DNA in S. islandicus REY15A) and Jaubert et al. (102 to 103 colonies/μg plasmid DNA in S. islandicus LAL14/1), in which simvastatin selection and uracil prototrophic selection were employed, respectively (10, 15). This variation in transformation efficiency may result from background growth in uracil selection that has been reported for S. islandicus (14, 36). In addition, many other factors, including experimental conditions, may impact the difference in transformation efficiencies between S. islandicus M.16.4 and S. islandicus REY15A, as have been described previously for other Sulfolobus species (S. solfataricus and S. acidocaldarius) (22, 35, 37, 38).

Fig 4.

Shuttle vector pCY-SsoargD-based transformation. (A) Construction of pCY-SsoargD. SsoargD was inserted into the SalI and XmaI restriction sites of pSSR/lacS, which harbored a simvastatin resistance marker (Simr) and lacS gene (15). (B) Plating of RJW004 (ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) transformed with pCY-SsoargD on rich medium containing uracil. Transformants were stained with X-Gal solution. (C) HindIII digestion of pCY-SsoargD extracted from E. coli (lane 1) or S. islandicus strains (lanes 2 and 3). (D) Evaluation of transformation efficiency for S. islandicus. One microgram of plasmid DNA of pCY-SsoargD was transformed into two different batches of fresh competent cells by electroporation. For transformation of each batch of competent cells, three replicates were performed.

Construction of a ΔupsEF mutation using an improved host marker system via the MID strategy.

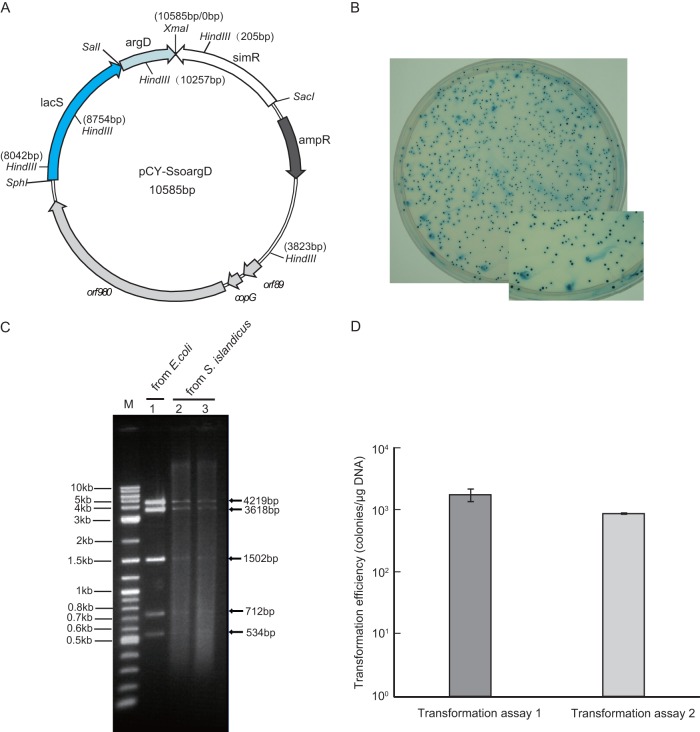

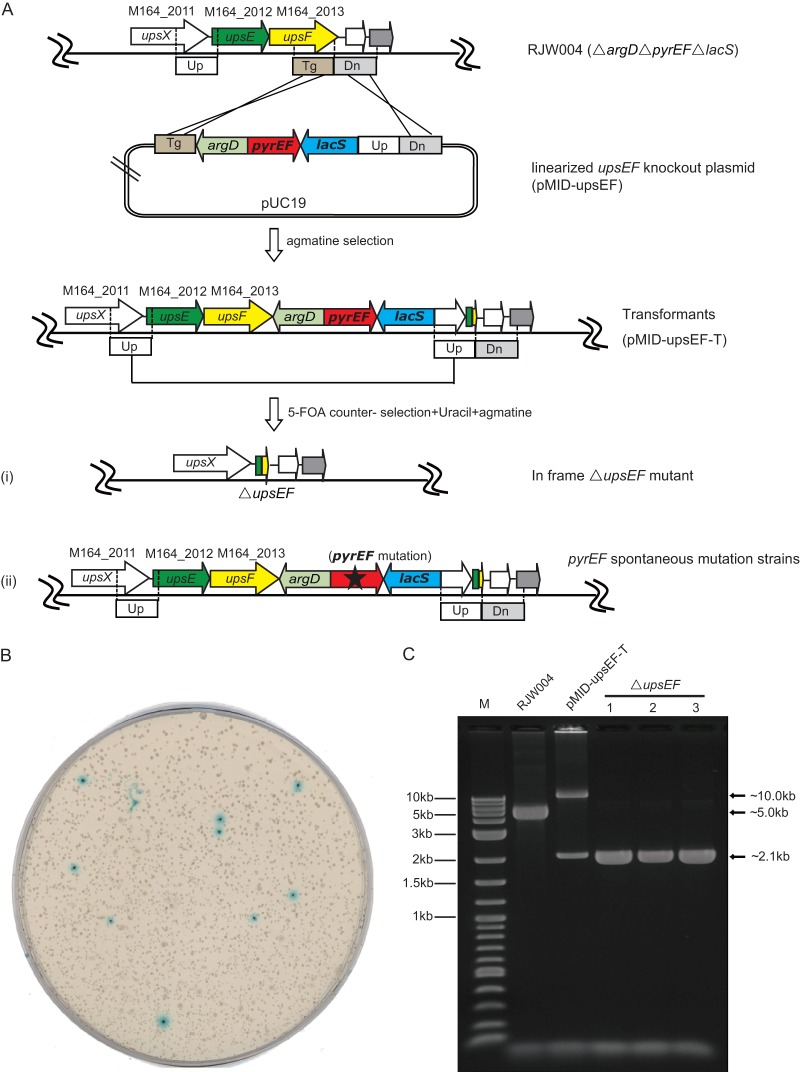

The host strain S. islandicus RJW004 (ΔargD ΔpyrEF ΔlacS) in combination with the vector carrying the hybrid marker module argD-pyrEF-lacS constituted a novel host marker system with greatly improved efficiency for chromosomal genetic manipulations. To test this novel system, we constructed a mutant with an in-frame deletion of upsEF via a next-generation marker insertion and unmarked target gene deletion (MID) strategy (11) (Fig. 5A). The upsEF (upsE and upsF) genes have been previously shown to be cotranscribed and to encode the key components for the type IV pilus assembly system in S. solfataricus and S. acidocaldarius (8, 23, 39). To construct upsEF deletion mutants, the upsEF knockout plasmid (pMID-upsEF) carrying homologues of upsEF (Up- and Dn-arm), a partial upsF (Tg-arm), as well as the hybrid selectable marker argD-pyrEF-lacS was first linearized and then transformed into host strain RJW004. Relying on agmatine selection, transformants with pMID-upsEF inserted can be readily obtained in nutrient-rich plates. PCR analysis of one transformant using upsEF-flankP-F/R showed that the marker module was successfully inserted into the host chromosome at the expected positions (Fig. 5C), and this transformant was named pMID-upsEF-T for the following studies. To further isolate unmarked upsEF deletion mutants, cell cultures of pMID-upsEF-T were spread onto plates containing uracil, 5-FOA, and agmatine (1 mg/ml). X-Gal visualization analysis of plates showed that blue colonies and white colonies formed with a ratio of more than 1:100 (Fig. 5B). The blue colonies were generated by spontaneous mutation in the pyrEF loci of pMID-upsEF-T, whereas the white colonies could be generated only by homologous recombination occurring between two repeated Up-arms, which resulted in the hybrid marker module as well as the target gene upsEF being excised from the host chromosome together (Fig. 5A). The selection of only strains that possess the deleted module is a notable advantage of the MID method over the PIS method, in which both the mutant and a regeneration of the original strain theoretically occur at equal frequencies. To confirm upsEF deletions, three white colonies were examined using primer pairs located outside the upsEF flanking region, and this showed that an ∼2.9-kb fragment was deleted in comparison with host strain RJW004, corresponding to the length of upsEF gene (Fig. 5C). One correct colony was selected and named RJW006 for further study.

Fig 5.

In-frame deletion of upsEF via next-generation marker insertion and unmarked target gene deletion (MID) method. (A) Schematic of the modified MID strategy. A linearized MID plasmid consisting of upstream (Up), downstream (Dn), and partial (Tg) sequences of upsF was transformed into genetic host RJW004. Transformants with the marker module inserted via double crossover between the plasmid and chromosome were easily selected by agmatine selection on rich medium. An in-frame upsEF deletion mutant with the marker removed was generated by further single crossover at two repeat Up-arms, which can be easily selected by 5-FOA counterselection in combination with X-Gal staining. (B) Plating of pMID-upsEF transformants (pMID-upsEF-T) on medium containing agmatine, uracil, and 5-FOA, followed by X-Gal staining. (C) PCR diagnosis of the upsEF gene alleles from the host strain and strains with pMID-upsEF-T and ΔupsEF. Diluted cell cultures were employed for PCR amplification using primer set upsEF flankP-F/R, which was designed outside Up- and Dn-arms. The excepted size range of PCR products was as follows: wild-type gene, ∼5.0 kb; recombinant allele, ∼10.0 kb; mutant allele, ∼2.1 kb. Two-log DNA ladders (0.1 to 10.0 kb) were loaded in lane M.

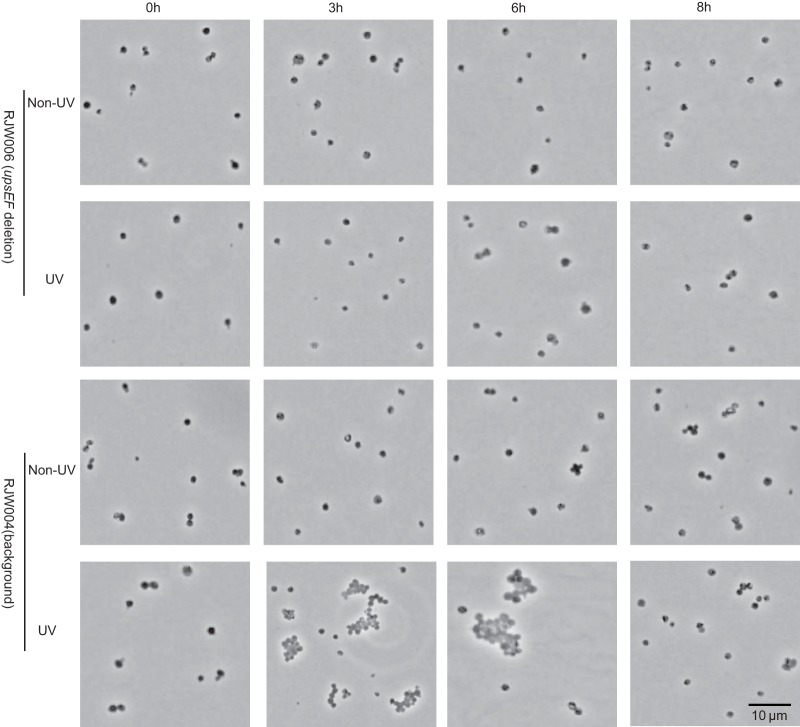

To demonstrate the phenotype of RJW006, we investigated the formation of cell aggregates of RJW004 (background strain) and RJW006 (upsEF deletion mutant) under the condition of UV exposure (75 J/m2) or without UV exposure according to a procedure described previously (23). As shown in Fig. 6, we found that large cell aggregates (>10 cells/aggregate) were generated frequently at 3 to 6 h of incubation when RJW004 (background strain) was treated by UV but not in the strain where upsEF was deleted, supporting the results that UV-inducible cell aggregation was mediated by upsEF in S. islandicus and that the upsEF gene probably plays a biological function similar to that described in S. solfataricus, S. acidocaldarius, and S. tokodaii (23, 39).

Fig 6.

Microscopy analysis of RJW006 (upsEF deletion mutant) and RJW004 (background strain) after UV treatment or without UV treatment. Ten microliters of S. islandicus cells was fixed on a Gelrite-coated microscope slide and then analyzed using Olympus BX60 (phase contrast). Representative micrographs of cells at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 8 h of incubation after UV treatment or without UV treatment are shown.

Conclusions.

Genetic manipulations in the hyperthermophilic archaeon S. islandicus have been challenging due to a lack of powerful positive selectable markers. We expanded the genetic toolbox for S. islandicus by developing a stringent positive selectable marker, argD, which greatly accelerated the isolation of transformants by directly spreading transformed cells on nutrient-rich plate medium. Since the polyamine biosynthesis pathway is relatively conserved in most hyperthermophilic archaea, argD may be developed as another broadly applicable selectable marker in hyperthermophilic archaea. In combination with the two existing pyrEF and lacS markers that we developed previously, a more efficient host marker system consisting of a hybrid marker module (argD-pyrEF-lacS) and a host strain with corresponding gene deletions was established. Based on this novel host marker system, we further developed the next generation of MID methodology for constructing markerless gene deletion mutations in S. islandicus chromosome and demonstrated its efficiency by deleting the upsEF genes in S. islandicus M.16.4. The development of versatile genetic markers, including hmgA, pyrEF, lacS, and argD, as well as novel host marker systems not only will allow us to conduct more sophisticated genetic studies (i.e., chromosomal gene exchange) in S. islandicus, which has served as model system for studying evolutionary genomics in archaea (40), but also will greatly facilitate genetic manipulation in other Sulfolobus species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We especially thank Qunxin She and Yulong Shen for providing Sulfolobus-E. coli shuttle vector pSSR/lacS, Marleen van Wolferen and Sonja-Verena Albers for helpful suggestions on the protocol of microscopy analysis for cell aggregation formation in S. islandicus cells, and William W. Metcalf for use of his microscope.

This work was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (grant number NNX09AM92G) and the NASA Astrobiology Institute under Cooperative Agreement no. NNA13AA91A issued through the Science Mission Directorate.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 July 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01608-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zillig W, Kletzin A, Schleper C, Holz I, Janekovic D, Hain J, Lanzendörfer M, Kristjansson JK. 1994. Screening for Sulfolobales, their plasmids and their viruses in Icelandic solfataras. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16:606–628 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitaker RJ, Grogan DW, Taylor JW. 2003. Geographic barriers isolate endemic populations of hyperthermophilic archaea. Science 301:976–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schleper C, Kubo K, Zillig W. 1992. The particle SSV1 from the extremely thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus is a virus: demonstration of infectivity and of transfection with viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:7645–7649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worthington P, Hoang V, Perez-Pomares F, Blum P. 2003. Targeted disruption of the alpha-amylase gene in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 185:482–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkner S, Lipps G. 2008. Genetic tools for Sulfolobus spp.: vectors and first applications. Arch. Microbiol. 190:217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.She Q, Zhang C, Deng L, Peng N, Chen Z, Liang YX. 2009. Genetic analyses in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus islandicus. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng L, Zhu H, Chen Z, Liang YX, She Q. 2009. Unmarked gene deletion and host-vector system for the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Sulfolobus islandicus. Extremophiles 13:735–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner M, van Wolferen M, Wagner A, Lassak K, Meyer BH, Reimann J, Albers SV. 2012. Versatile genetic tool box for the crenarchaeote Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Front. Microbiol. 3:214. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakofsky CJ, Runck LA, Grogan DW. 2011. Sulfolobus mutants, generated via PCR products, which lack putative enzymes of UV photoproduct repair. Archaea 2011:864015. 10.1155/2011/864015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaubert C, Danioux C, Oberto J, Cortez D, Bize A, Krupovic M, She Q, Forterre P, Prangishvili D, Sezonov G. 2013. Genomics and genetics of Sulfolobus islandicus LAL14/1, a model hyperthermophilic archaeon. Open Biol. 3:130010. 10.1098/rsob.130010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Guo L, Deng L, Wu Y, Liang Y, Huang L, She Q. 2010. Revealing the essentiality of multiple archaeal pcna genes using a mutant propagation assay based on an improved knockout method. Microbiology 156:3386–3397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C, Tian B, Li S, Ao X, Dalgaard K, Gokce S, Liang Y, She Q. 2013. Genetic manipulation in Sulfolobus islandicus and functional analysis of DNA repair genes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41:405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samson RY, Xu Y, Gadelha C, Stone TA, Faqiri JN, Li D, Qin N, Pu F, Liang YX, She Q, Bell SD. 2013. Specificity and function of archaeal DNA replication initiator proteins. Cell Rep. 3:485–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Whitaker RJ. 2012. A broadly applicable gene knockout system for the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus islandicus based on simvastatin selection. Microbiology 158:1513–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng T, Huang Q, Zhang C, Ni J, She Q, Shen Y. 2012. Development of a simvastatin selection marker for a hyperthermophilic acidophile, Sulfolobus islandicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:568–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumi R, Manabe K, Fukui T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. 2007. Disruption of a sugar transporter gene cluster in a hyperthermophilic archaeon using a host-marker system based on antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 189:2683–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hileman TH, Santangelo TJ. 2012. Genetics techniques for Thermococcus kodakarensis. Front. Microbiol. 3:195. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipscomb GL, Stirrett K, Schut GJ, Yang F, Jenney FE, Jr, Scott RA, Adams MW, Westpheling J. 2011. Natural competence in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus facilitates genetic manipulation: construction of markerless deletions of genes encoding the two cytoplasmic hydrogenases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2232–2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda W, Morimoto N, Imanaka T, Fujiwara S. 2008. Agmatine is essential for the cell growth of Thermococcus kodakaraensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 287:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santangelo TJ, Cubonova L, Reeve JN. 2010. Thermococcus kodakarensis genetics: TK1827-encoded beta-glycosidase, new positive-selection protocol, and targeted and repetitive deletion technology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1044–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins RC, Sun J, Jenney FE, Jr, Chandrayan SK, McTernan PM, Adams MW. 2011. Homologous expression of a subcomplex of Pyrococcus furiosus hydrogenase that interacts with pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase. PLoS One 6:e26569. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albers SV, Driessen AJ. 2008. Conditions for gene disruption by homologous recombination of exogenous DNA into the Sulfolobus solfataricus genome. Archaea 2:145–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frols S, Ajon M, Wagner M, Teichmann D, Zolghadr B, Folea M, Boekema EJ, Driessen AJ, Schleper C, Albers SV. 2008. UV-inducible cellular aggregation of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is mediated by pili formation. Mol. Microbiol. 70:938–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frols S, Gordon PM, Panlilio MA, Duggin IG, Bell SD, Sensen CW, Schleper C. 2007. Response of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus to UV damage. J. Bacteriol. 189:8708–8718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles TN, Graham DE. 2008. Crenarchaeal arginine decarboxylase evolved from an S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 283:25829–25838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reno ML, Held NL, Fields CJ, Burke PV, Whitaker RJ. 2009. Biogeography of the Sulfolobus islandicus pan-genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8605–8610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.She Q, Singh RK, Confalonieri F, Zivanovic Y, Allard G, Awayez MJ, Chan-Weiher CC, Clausen IG, Curtis BA, De Moors A, Erauso G, Fletcher C, Gordon PM, Heikamp-de Jong I, Jeffries AC, Kozera CJ, Medina N, Peng X, Thi-Ngoc HP, Redder P, Schenk ME, Theriault C, Tolstrup N, Charlebois RL, Doolittle WF, Duguet M, Gaasterland T, Garrett RA, Ragan MA, Sensen CW, Van der Oost J. 2001. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7835–7840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Brugger K, Skovgaard M, Redder P, She Q, Torarinsson E, Greve B, Awayez M, Zibat A, Klenk HP, Garrett RA. 2005. The genome of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a model organism of the Crenarchaeota. J. Bacteriol. 187:4992–4999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, Jin-no K, Takahashi M, Sekine M, Baba S, Ankai A, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Fukui S, Nagai Y, Nishijima K, Otsuka R, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Kato Y, Yoshizawa T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Masuda S, Yanagii M, Nishimura M, Yamagishi A, Oshima T, Kikuchi H. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. DNA Res. 8:123–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auernik KS, Maezato Y, Blum PH, Kelly RM. 2008. The genome sequence of the metal-mobilizing, extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula provides insights into bioleaching-associated metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:682–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You XY, Liu C, Wang SY, Jiang CY, Shah SA, Prangishvili D, She Q, Liu SJ, Garrett RA. 2011. Genomic analysis of Acidianus hospitalis W1, a host for studying crenarchaeal virus and plasmid life cycles. Extremophiles 15:487–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, Yamazaki S, Haikawa Y, Jin-no K, Takahashi M, Sekine M, Baba S, Ankai A, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Fukui S, Nagai Y, Nishijima K, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Masuda S, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Kubota K, Nakamura Y, Nomura N, Sako Y, Kikuchi H. 1999. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res. 6:83–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maezato Y, Johnson T, McCarthy S, Dana K, Blum P. 2012. Metal resistance and lithoautotrophy in the extreme thermoacidophile Metallosphaera sedula. J. Bacteriol. 194:6856–6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng N, Deng L, Mei Y, Jiang D, Hu Y, Awayez M, Liang Y, She Q. 2012. A synthetic arabinose-inducible promoter confers high levels of recombinant protein expression in hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus islandicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:5630–5637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurosawa N, Grogan DW. 2005. Homologous recombination of exogenous DNA with the Sulfolobus acidocaldarius genome: properties and uses. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudbergsdottir S, Deng L, Chen Z, Jensen JV, Jensen LR, She Q, Garrett RA. 2011. Dynamic properties of the Sulfolobus CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems when challenged with vector-borne viral and plasmid genes and protospacers. Mol. Microbiol. 79:35–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berkner S, Grogan D, Albers SV, Lipps G. 2007. Small multicopy, non-integrative shuttle vectors based on the plasmid pRN1 for Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and Sulfolobus solfataricus, model organisms of the (cren)archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e88. 10.1093/nar/gkm449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maezato Y, Dana K, Blum P. 2011. Engineering thermoacidophilic archaea using linear DNA recombination. Methods Mol. Biol. 765:435–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajon M, Frols S, van Wolferen M, Stoecker K, Teichmann D, Driessen AJ, Grogan DW, Albers SV, Schleper C. 2011. UV-inducible DNA exchange in hyperthermophilic archaea mediated by type IV pili. Mol. Microbiol. 82:807–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C, Krause DJ, Whitaker RJ. 2013. Sulfolobus islandicus: a model system for evolutionary genomics. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41:458–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.