Abstract

Natural heterogeneity in the structure of the lipid A portion of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produces differential effects on the innate immune response. Gram-negative bacterial species produce LPS structures that differ from the classic endotoxic LPS structures. These differences include hypoacylation and hypophosphorylation of the diglucosamine backbone, both differences known to decrease LPS toxicity. The effect of decreased toxicity on the adjuvant properties of many of these LPS structures has not been fully explored. Here we demonstrate that two naturally produced forms of monophosphorylated LPS, from the mucosa-associated bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Prevotella intermedia, function as immunological adjuvants for antigen-specific immune responses. Each form of mucosal LPS increased vaccination-initiated antigen-specific antibody titers in both quantity and quality when given simultaneously with vaccine antigen preparations. Interestingly, adjuvant effects on initial T cell clonal expansion were selective for CD4 T cells. No significant increase in CD8 T cell expansion was detected. MyD88/Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TRIF/TLR4 signaling pathways showed equally decreased signaling with the LPS forms studied here as with endotoxic LPS or detoxified monophosphorylated lipid A (MPLA). Natural monophosphorylated LPS from mucosa-associated bacteria functions as a weak but effective adjuvant for specific immune responses, with preferential effects on antibody and CD4 T cell responses over CD8 T cell responses.

INTRODUCTION

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin, is a common term used for the major cell wall constituent of Gram-negative bacteria, which differs in composition depending on the bacterial species in which it is formed. For decades, endotoxic forms of LPS have been studied as natural adjuvants for specific immune responses, especially antigen (Ag)-specific antibody and T cell responses (1–3). The toxicity associated with LPS structures has precluded their use as effective and safe vaccine adjuvants. However, the discovery and characterization of monophosphorylated lipid A (MPLA), a chemically degraded structure from Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota Re595 LPS, have yielded a preparation that is less toxic than its parent LPS molecule but similarly immunostimulatory. Therefore, MPLA works well as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Lipid A structural features known to account for the maintenance of adjuvant properties and the loss of toxicity include the number of phosphate groups, as well as the number, type, and location of fatty acid residues (4–6). Although the most abundant structure in the S. Minnesota MPLA used in these studies is a hexa-acylated structure (Fig. 1), the preparation also contains a mixture of underacylated lipid A structures, including penta-, tetra-, and triacylated forms known to be less potent, less toxic, or less antagonistic of TLR4 signaling than the parent LPS molecule (7, 8). Further, the absence of a single phosphate residue from the synthetic form of Escherichia coli lipid A is enough to decrease the production of proinflammatory factors, with little effect on many other products associated with adaptive immunity, including type I interferon (IFN) and IFN-inducible products (9–11). Although MPLA is a partially degraded form of an endotoxic LPS produced after chemical extraction (12), low-toxicity forms of LPS (LT-LPS) are produced naturally as cell wall constituents of bacterial species colonizing various mucosal linings, including the oral and intestinal cavities (13–15). These LPS forms are structurally similar to MPLA (Fig. 1). The LPS structures from Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, and Prevotella species are naturally monophosphorylated but penta-acylated, whereas MPLA is primarily hexa-acylated (16–18). Like MPLA, LPS obtained from these bacterial species is less toxic than E. coli LPS (17, 19). The published Bacteroides fragilis LPS structure has been shown to be at least 1,000-fold less toxic than E. coli LPS in vivo after d-galactosamine priming (20). The striking differences in toxicity in response to the various Gram-negative species LPS forms has led Munford to propose that the structural features of LPS act as guides enabling the host Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MD2 receptor system to distinguish the low-toxicity commensal Gram-negative bacteria from the more highly pathogenic members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (21).

Fig 1.

Predominant structures of the LPS preparations used as adjuvants.

Possible mechanisms that may account for the reduced toxicity of these LPS forms include (i) decreased affinity for the TLR4/MD2 receptor, (ii) differential ability to associate at the initial steps of TLR4 engagement, from lipoprotein binding protein (LBP) and CD14 to MD2 and TLR4 binding (22–24), and (iii) differential or preferential signaling through one or both signaling adaptor proteins associated with TLR4: MyD88 or TRIF. Coats et al. have demonstrated that the penta-acylated Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS (Pg 1690) structure is monophosphorylated on the 4′ carbon of the diglucosamine head group and has intermediate TLR4/MD2-stimulatory effects through NF-κB (6). Furthermore, this preparation functions as a weak TLR4 agonist in vitro, and that weak agonism of TLR4 activates a subset of the genes activated by endotoxic E. coli LPS, suggesting a hierarchy of transcriptional activation through TLR4 agonism based on the strength of the signal (18). Interestingly, the specific set of genes activated after partial or weak TLR4/MD2 agonism with P. gingivalis LPS in vitro was focused on cellular immune responses, with the majority of the genes associated with either immune cell adhesion or cell trafficking (18). Similarly, MPLA-stimulated cells have demonstrated a bias toward utilizing the TLR4 signaling adaptor protein TRIF, as opposed to MyD88, in eliciting cellular responses (25), which could help explain the retention of immune-stimulatory activities even when toxic activities are markedly decreased (26–28).

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Prevotella intermedia are two mucosa-associated Gram-negative species that produce predominately low-toxicity forms of LPS identical or similar to the published LT-LPS produced by B. fragilis (16–18, 20). In this report, LPS forms obtained from these bacteria were examined for adjuvant properties in vivo. S. Minnesota LPS (SmLPS) and S. Minnesota MPLA (SmMPLA) were used as benchmark TLR4 adjuvants for comparison to the adjuvant effects elicited by LPS from B. thetaiotaomicron (BtLPS) or P. intermedia (PiLPS). Adjuvant effects on the antigen-specific antibody response and the initial T cell clonal expansion were assessed. Each preparation tested influenced the expression of antigen-specific IgG subtypes, both the amount and the kinetics of the antigen-specific antibody response. Additionally, these LPS preparations led to preferential antigen-specific clonal expansion of CD4 T cells but had no effect on CD8 T cell antigen-specific expansion. Together, these results indicate that BtLPS and PiLPS structures function in vivo as immunological adjuvants; however, their effects are smaller and less broad than that of endotoxic SmLPS or its related SmMPLA form.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

BALB/cByJ and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6Nai-[Tg]OT-I-[KO]RAG1 (OTI) and C57BL/6-[Tg]OT-II-[KO]RAG1 (OTII) (29–31) mice were originally purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and were bred to Cd45a(Ly5a)/NAi (B6.SJL) mice so that they were no longer RAG1 deficient and were congenic to C57BL/6 at the Ptprca, Cd45 locus, resulting in mice referred to as OTI.SJL and OTII.SJL. Mice were bred and housed in a specific-pathogen-free barrier facility at the Institute for Cellular Therapeutics, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, and were cared for according to specific University of Louisville and National Institutes of Health animal care guidelines.

Reagents.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine Engerix-B (GSK Biologicals), including aluminum hydroxide (alum) as an adjuvant, was purchased from the University of Louisville Hospital pharmacy. Recombinant hepatitis B virus surface antigen (rHBsAg) subtype adw was purchased from Aldevron. Egg white albumin was isolated from endotoxin-free embryonated eggs (Charles River) and was found to contain less than 0.05 endotoxin units/ml as measured by a quantitative chromogenic Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (QCL-1000; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). Formalin-inactivated influenza virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) was purchased from Charles River. Ovalbumin peptides for OTII (Ova323-339; ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR) and OTI (Ova257-264; SIINFEKL) mice were synthesized and found to be endotoxin free by CPC Scientific (Sunnyvale, CA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and incomplete Freund's adjuvant were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin subtype secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (IgM, total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG2c) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.

Lipid A and LPS preparations.

SmLPS and SmMPLA were purchased from InvivoGen for the egg white albumin immunization experiment and from Alexis Biochemicals for the remainder of the experiments. B. thetaiotaomicron and P. intermedia LPS preparations were obtained using a modified Tri reagent protocol for LPS isolation, as described previously (32, 33). Dried LPS samples were suspended in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) containing 1% SDS, heated at 100°C for 1 h, and then lyophilized overnight. Pellets were washed in ice-cold 95% ethanol containing 0.02 N HCl, followed by three 95% ethanol washes. LPS preparations were subjected to a final Bligh-Dyer extraction, which consisted of 1.16 ml of a chloroform-methanol-water mixture (1:1:0.9), in order to remove the residual carbohydrate contaminants. Lyophilized preparations were suspended to a stock concentration of 1.0 mg/ml in DMSO. Therefore, DMSO (Sigma) was added as the vehicle control to levels consistent with those used in the LT-LPS treatments.

Immunizations.

Groups of 5 or 6 C57BL/6J mice were immunized subcutaneously (s.c.) in each of the two hocks, at the base of the leg posterior to the knee joint, with 0.2 μg Engerix-B, a commercially available HBV vaccine (total, 0.4 μg per mouse) that already contains alum as an adjuvant. The HBV vaccine was combined with either a vehicle control, 1.5 μg SmLPS (Alexis Biochemicals), 5 μg SmMPLA (Alexis Biochemicals), 5 μg BtLPS, or 5 μg PiLPS. A single boost immunization (at 5 weeks) was the same as the primary immunization. Serum samples were collected by lateral tail vein bleeds 2 weeks after the primary immunization and 1 week after the boost. Formalin-inactivated influenza virus (A/PR/8/34) particles (iPR8) were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and groups of five C56BL/6J mice were immunized subcutaneously with 0.25 μg iPR8 (total, 0.5 μg per mouse) and either a vehicle control, 1.5 μg SmLPS (Alexis), 5 μg SmMPLA (Alexis), 5 μg BtLPS, or 5 μg PiLPS. The second (at 5 weeks) and third (at 20 weeks) immunizations were the same for each group. Serum samples were taken at 4 weeks for primary immunization and then 1 week following each subsequent immunization. Egg white albumin (40 μg) was emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant along with either a vehicle control (DMSO), 10 μg SmLPS (InvivoGen), 20 μg SmMPLA (InvivoGen), 20 μg BtLPS, or 20 μg PiLPS. Groups of six BALB/cByJ mice were immunized with 100 μl of the emulsified vaccine preparations subcutaneously in the flanks. Second (at 4 weeks) and third (at 16 weeks) immunizations were the same for each group, except that 10 μg egg white albumin was used as the antigen. Serum samples were obtained at 3 weeks for primary immunization and then 4 days after subsequent immunizations. All serum samples were stored at −80°C until enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed to determine the titers of antigen-specific antibody present. No animal exhibited signs of endotoxemia during these experiments. The amounts used (1.5 to 10 μg SmLPS or 5 to 20 μg SmMPLA, BtLPS, or PiLPS) are much lower than those used to study the toxic effects of LPS (typically 50 to 200 μg).

Antigen-specific antibody titers determined by ELISA.

An antigen specific to the immunization protocol (rHBsAg, iPR8, or egg white albumin) was adhered to Immulon 2 ELISA plates. Wells were blocked overnight at 4°C using 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS. Replicate plates were used; serial 10-fold dilutions of the serum samples were made; and 100 μl of each dilution was incubated on the Ag-coated plates. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM, total IgG, IgG1, IgG2c (or IgG2a), and IgG2b secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used to detect specific isotypes. Titers are expressed as the inverse of the dilution required to reach the half-maximum value of the absorbance curve, as determined by SoftMax Pro software.

BM-DC derivation, culture and qRT-PCR.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DC) were prepared according to the protocol of Lutz et al. (34). Bone marrow cells were collected from femurs and tibiae of C57BL/6 mice, and 2 × 106 cells were placed in bacteriological culture plates for 10 days in a complete medium, RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Valley Biomedical), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; R&D Systems). Cultures were given new medium and GM-CSF on days 3, 6, and 8. Nonadherent cells were collected on day 10 and were verified by flow cytometry to be 90 to 95% CD11c+ CD11b+ MHCII+ Gr1− before use in experiments. For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, 1 × 106 BM-DC were rested for 2 h in 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences) in complete medium. The cells were then activated with increasing concentrations of the test adjuvant preparations. After 2 h, total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen), and 0.5 μg total RNA was used to make cDNA by using qScript cDNA synthesis kits (Quanta) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was diluted 2-fold and was then amplified with 0.5 μM target (endothelin1, Ifit1, ip10, or il10) or control (gapdh) QuantiTect primer assays from Qiagen. qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 real-time system C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) with Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA abundance was calculated by the comparative cycle method (ΔΔCT) using vehicle control (DMSO)-treated cells for normalization.

Primary human monocyte culture.

Deidentified human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individual healthy donors were obtained as a waste product of polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) isolation from another group at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. PBMC monocytes were enriched by plating 2 × 106 cells per well in 24-well tissue culture plates for 2 h in 0.5 ml complete medium. Adherent cells were enriched by washing away the nonadherent cells with three washes consisting of 1× Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Life Technologies). The resulting cells were then rested for an additional 2 h before being activated by increasing concentrations of adjuvant preparations. RNA isolation and qRT-PCR were performed, and the results were analyzed as described above for mouse BM-DC. PCRs used undiluted cDNA with 0.5 μM target (human IL-6, endothelin1, or IFIT1) or control (human GAPDH) QuantiTect primer assays.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni post hoc analysis was used to compare the serum antibody titers in vivo. One-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis were used to compare the mean values for adjuvant-dependent T cell clonal expansion.

RESULTS

Naturally occurring LT-LPS preparations promote a balanced isotype profile after vaccination.

The abilities of the BtLPS and PiLPS forms to function as immunological adjuvants were assessed with three separate immunization antigens. Because a preliminary study detected no antigen-specific antibody when SmLPS or SmMPLA was used as the adjuvant for soluble egg white albumin given subcutaneously, each of the antigens chosen was given along with a known adjuvant to ensure that an antibody response would be mounted in the time allotted (data not shown). The antigens were (i) a commercially available hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine, which contains aluminum hydroxide, (ii) formalin-inactivated PR8 (iPR8) influenza virus particles, which have endogenous TLR7 agonist RNA, and (iii) egg white albumin emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. The doses of antigen and adjuvants used in each protocol were chosen to optimize the adjuvant effects. Previous studies had also determined that 2- to 3-fold more SmMPLA than SmLPS is needed to elicit similar levels of peak T cell clonal expansion in different groups of mice (26), and the LT-LPS amounts used were matched to that of SmMPLA. Because stock LT-LPS preparations were suspended in DMSO, enough DMSO was added to each vaccine preparation to control for the DMSO present in the LT-LPS-adjuvanted vaccine preparations.

An alum-containing HBV vaccine supplemented with the natural LT-LPS preparations was given subcutaneously to groups of C57BL/6 mice. DMSO alone was added for the baseline control group, while SmLPS or SmMPLA was added for positive-control TLR4 agonist groups. Titers of antigen-specific antibodies in serum were used to monitor the developing immune responses after immunization. Adjuvant responses would be indicated if either BtLPS or PiLPS was able to change or supplement the alum-directed Th2-like antibody response (inducing IgG1) with a Th1-like response (inducing IgG2c or IgG2b). All HBV vaccine-treated C57BL/6 mice mounted similar IgM responses to HBsAg (Fig. 2A). However, higher total-IgG titers than those for the vehicle control group were observed after the first immunization for all LPS-treated groups (Fig. 2A); therefore, increased isotype switching occurred in each of the LPS-treated groups. As expected, the titers of the IgG1 subtype (Fig. 2A) were significantly increased after both primary and boost immunizations with only alum, and there was no difference from alum when any of the LPS forms was added (35, 36). The control immunization group had increased IgG2b titers after the boost immunization, whereas IgG2c titers remained low throughout. The IgG2b responses were nearly identical in all the groups with LPS as an adjuvant. Although no increase in the complement-fixing IgG2c subclass was evident with any of the groups after the primary immunization, each of the LPS-treated groups had high titers after the boost immunization, which is typical after a sufficient immune response is mounted. Both BtLPS and PiLPS increased IgG2c titers after this immunization, but titers for the BtLPS-treated group were lower than those for the SmLPS-treated group. No such difference was noted between the PiLPS- and SmLPS-treated groups. Both the BtLPS and PiLPS groups exhibited IgG2b titers significantly higher than that of the control vaccine group and not significantly lower than those elicited by SmLPS or SmMPLA after both the primary and boost immunizations. The increase in the breadth of the IgG subtypes after the inclusion of either BtLPS or PiLPS in these immunizations indicates immune adjuvant activity in these preparations.

Fig 2.

Antigen-specific antibody responses in sera of HBV vaccine-immunized C57BL/6 mice. (A) Groups of C57BL/6 mice were immunized s.c. with an HBV vaccine in the absence (+DMSO) or presence (3 μg SmLPS, 10 μg SmMPLA, 10 μg BtLPS, or 10 μg PiLPS) of LPS preparations on day zero, followed by a boost immunization 5 weeks after the primary immunization. Serum was sampled before and after each of the immunizations, and the titers of HBsAg-specific IgM, total IgG, IgG1, IgG2c, and IgG2b were determined by ELISA by limiting dilution. Arrowheads indicate times of vaccination. (B) Antigen-specific IgG2a titers after the third immunization with egg white albumin emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant with either a vehicle control (+DMSO) or one of the adjuvant preparations. (C) Antigen-specific IgG2b titers after the second immunization with iPR8 influenza virus particles and either a vehicle control (+DMSO) or one of the adjuvant preparations. Results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means of the antibody titer, calculated as the inverse of the dilution factor (df) needed to give the half-maximum value (max1/2) of the absorbance curve after 10-fold serial dilutions. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the DMSO control group at a 95% (P < 0.05) confidence level, as determined using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

The antibody responses in the two other immunization protocols also demonstrated the adjuvant activity of the LT-LPS preparations (see Tables S1 to S5 in the supplemental material). In the first protocol, BALB/c mice were given three subcutaneous immunizations of egg white albumin in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. The results from this protocol were initially hampered by relatively higher titers of antigen-specific antibodies, especially IgM and IgG2b isotypes, in the preimmunization serum samples (data not shown), possibly caused by environmental exposure to ovalbumin in feed or bedding. A similar polyclonal antiovalbumin response was seen in unimmunized BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania infantum (37). After the third immunization, each LPS preparation tested increased the titers of the complement-fixing, Th1-associated isotype IgG2a in most vaccinated mice (Fig. 2B). The BtLPS group had several low responders (titer, ≤200), which increased the variability observed, thus making the difference between the vehicle control and BtLPS groups insignificant (Fig. 2B).

Subcutaneous immunization of C57BL/6 mice with iPR8 virus particles and the LPS preparations elicited increased titers in all immunized groups, including the DMSO control group (see Tables S6 to S10 in the supplemental material). Following the second immunization, minor differences in titers of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-associated isotype IgG2b were detected between the control group and the groups treated with SmLPS, BtLPS, or PiLPS, but not SmMPLA (Fig. 2C). However, the subsequent immunization increased all isotype titers and eliminated the differences between the DMSO control and LPS-treated groups (data not shown).

Together, the results from these three immunization protocols clearly demonstrate adjuvant activity for BtLPS and PiLPS, meaning that the inclusion of either preparation leads to increased titers and/or a more diverse repertoire of antibodies to various T cell-dependent antigens, therefore indirectly providing evidence for effects on T cell responses.

Natural LT-LPS preparations from B. thetaiotaomicron and P. intermedia serve as adjuvants for the initial clonal expansion of CD4+ T cells in vivo.

Adjuvant signals are required for productive or sustained clonal expansion of naïve CD4 or CD8 T cells in response to purified antigen in vivo (1, 38). LPS is a natural adjuvant that increases the number of cell divisions and the rate of cell survival during and after T cell activation and clonal expansion (1, 39, 40). SmMPLA also acts effectively as an adjuvant for initial T cell clonal expansion in vivo, which we and others have shown is dependent on the TLR4 signaling adaptor TRIF (25, 26). Using a standard adoptive-transfer model of ovalbumin-specific T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic (Tg) CD8 and CD4 T cells (OTI.SJL and OTII.SJL cells, respectively), we assessed the effects of LT-LPS on initial T cell clonal expansion compared to the effects elicited with SmLPS and SmMPLA. After adoptive transfer of OTI (CD45.1) and OTII (CD45.1) Tg-TCR cells (1 × 105 and 1.5 × 105, respectively), C57BL/6 (CD45.2) recipients were treated with antigenic peptides mixed with either a vehicle control or one of the LPS forms as an adjuvant through intravenous injection. The fold increases in OTI and OTII cell accumulation in the spleen or perfused lung tissue at peak clonal expansion for mice treated with an adjuvant over the levels for controls given only the peptide antigens with DMSO were calculated. As shown in Fig. 3, each of the preparations tested increased the number of splenic antigen-specific T cells; therefore, each of the LT-LPS preparations was able to serve as an adjuvant for initial T cell clonal expansion. BtLPS treatment increased the level of CD4 T cells (OTII) to approximately one-half or one-third of the response seen with SmLPS or SmMPLA, respectively. PiLPS increased the CD4 clonal expansion to a level similar to that for SmLPS. The adjuvant effects of the LT-LPS preparations on CD8 T cell numbers were markedly lower than that for SmLPS or SmMPLA. BtLPS increased the number of CD8 T cells in the spleen 3-fold over that with the antigen alone, while the PiLPS increase was near 4-fold.

Fig 3.

Short-term T cell clonal expansion is increased in the spleens of animals immunized with any of the LPS preparations. (A) Schematic of the adoptive transfer and immunization protocol used on recipient C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mice. Spleen cells (105 OTI.SJL cells and 1.5 × 105 OTII.SJL [CD45.1] cells) were transferred 2 days before intravenous immunization with antigenic peptides in the absence (DMSO) or presence of TLR4 agonists. The numbers of cells present in primary (spleen) and secondary (lung) organs 3.5 days after immunization were determined. (B) Numbers of antigen-specific CD4 (OTII) and CD8 (OTI) T cells recovered in each tissue were determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as fold increases, calculated as the number of cells recovered from adjuvant-treated mice divided by the average number of cells recovered from the group treated with the antigen only, with no adjuvant (DMSO). Data are from two independent experiments, with triplicate mice used in each. Results for the individual recipients from experiments 1 (circles) and 2 (triangles) are shown. The horizontal line indicates the average fold increase for the combined groups. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the DMSO control group as determined by one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis (P < 0.05).

Because adjuvant signals are needed for activated T cells to migrate to nonlymphoid sites after activation (41, 42), the number of activated T cells in the lungs is an indicator of TLR-dependent adjuvant effects in vivo. Adjuvant-specific increases in the numbers of CD4 T cells in the lungs were markedly greater than those with the antigen alone (averages, 16.9-fold ± 3.2-fold for BtLPS and 12.2-fold ± 3.5-fold for PiLPS), though less than those observed with SmLPS or SmMPLA. However, the increases in the numbers of OTI CD8 T cells in the lung were only marginal for recipients of either LT-LPS preparation and did not reach significance. The numbers of CD8 T cells in the lungs, and the fold increases in these numbers, for groups receiving SmLPS or SmMPLA as an adjuvant increased significantly, but the fold increases were lower than those observed for CD4 T cells.

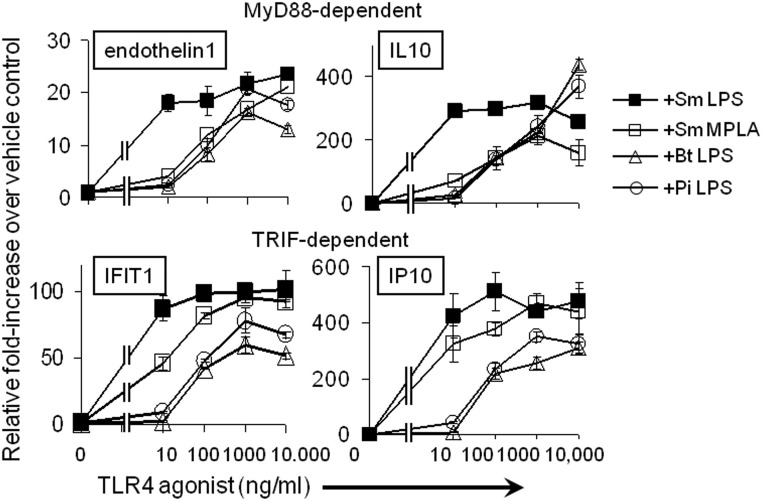

Natural LT-LPS preparations are equally ineffective at inducing factors associated with MyD88-dependent or TRIF-dependent TLR4 signaling.

Previous studies have demonstrated that SmMPLA functions as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4 in vivo (25). The TRIF-biased terminology stems from the observations that TLR4/MyD88-dependent signaling outcomes after SmMPLA stimulation were diminished from those obtained with SmLPS. Although effects were indicated on both TLR4 signaling branches, the TRIF-dependent outcomes were less severely diminished than the MyD88-dependent outcomes (9, 25). Moreover, it was found that CD8 T cell expansion was more dependent on TLR4/TRIF signaling than was CD4 T cell expansion (25). Therefore, we assessed the abilities of BtLPS and PiLPS to induce MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent transcripts in BM-DC. As shown in Fig. 4, transcript levels for two MyD88-dependent factors, endothelin-1 and interleukin 10 (IL-10), were increased in a dose-dependent manner for all monophosphorylated preparations, whereas the SmLPS MyD88-dependent responses had already reached their peak at the lowest dose tested (10 ng/ml). The SmMPLA, BtLPS, and PiLPS preparations each required more agonist to reach the maximal induction seen with the lowest dose of SmLPS, and their curves are comparable to each other until they reach the 10,000-ng/ml dose, where the SmMPLA response is lower than the BtLPS or PiLPS response. Transcript levels for the TRIF-dependent factors, IFIT1 (interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1) and IP-10 (gamma interferon-inducible protein 10), were similar for SmLPS and SmMPLA, except, again, at the lowest concentration used (10 ng/ml), where SmLPS had maximally increased each transcript, while SmMPLA required 100 ng/ml to reach maximal induction of IFIT1 transcript levels. The natural B. thetaiotaomicron and P. intermedia LT-LPS preparations also increased these TRIF-dependent transcripts in a dose-dependent manner, but even more than either SmLPS or SmMPLA was required for maximal increases (occurring at 1,000 ng/ml). In contrast with the results for the MyD88 products, the maximal induction obtained with either LT-LPS form was lower than that obtained with SmLPS or SmMPLA (Fig. 4). Hence, BtLPS and PiLPS have similarly low increases in the mRNA levels of MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent factors, and as such, TRIF-biased signaling effects were not observed with these TLR4 agonists.

Fig 4.

LT-LPS preparations have lower relative effects than SmLPS or SmMPLA through TLR4/MD2 on either the MyD88- or the TRIF-dependent branch. BM-DC were treated with increasing concentrations of the LPS preparations for 2 h. qRT-PCR was performed to detect fold increases in steady-state levels of the MyD88-dependent endothelin-1 and IL-10 transcripts or the TRIF-dependent IFIT1 and IP-10 transcripts. Results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means for triplicate determinations from one of two independent experiments.

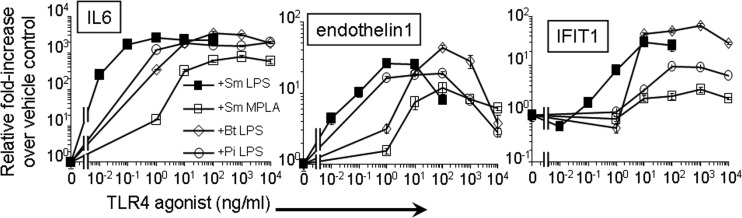

Species differences in TLR4 sensitivity to various LPS structures are well characterized (43). Several forms of LPS that act as antagonists on human TLR4/MD2 are partial or weak agonists for mouse TLR4/MD2. Also, human TLR4 responds to lower concentrations of LPS than mouse TLR4 (44). We therefore assessed the transcriptional induction of some TLR4 response factors using LT-LPS preparations on an enriched population of primary human monocytes. As expected, the minimal dose of SmLPS (0.01 ng/ml) increased the numbers of transcripts of proinflammatory factors IL-6 and endothelin-1, a response quite different from that induced by SmMPLA. Levels of induction with the LT-LPS preparations fell between the levels with these benchmark TLR4 agonists. Although the PiLPS dose curves for both IL-6 and endothelin-1 mRNA were similar to the SmLPS curve (Fig. 5), the BtLPS dose curve was similar to the SmLPS curve only for IL-6. The endothelin-1 mRNA response to BtLPS required more agonist to reach the maximum and was similar to the SmMPLA response but achieved higher maximum induction (Fig. 5). The LT-LPS induction curves for the TRIF-associated product IFIT1 were intermediate between the highly induced levels with SmLPS and the poorly induced levels with SmMPLA, which barely increased more than 2-fold at higher doses (1,000 ng/ml). PiLPS required more agonist and reached a lower maximal induction of IFIT1 mRNA than either SmLPS or BtLPS. However, BtLPS increased IFIT1 mRNA expression in human monocytes to a maximum similar to that with SmLPS but required more agonist to do so (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

LT-LPS preparations activate primary human monocytes. Primary human monocytes, enriched from PBMC preparations by adherence to plastic, were treated with increasing concentrations of the LPS preparations for 2 h. qRT-PCR was performed to quantify relative increases in levels of the inflammatory markers IL-6 and endothelin-1 and the type I IFN-dependent marker IFIT1. Results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means for triplicate determinations from one of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although previous reports have routinely suggested that naturally occurring LT-LPS structures may represent a new class of immunologic adjuvants, to our knowledge these studies represent the first test of their ability to function as such in vivo, increasing antigen-specific immune responses. The results presented here suggest that the TLR4 responses to these and other LT-LPS forms may indeed be a means to fine-tune the innate immune response so as to elicit the most desired immune effector functions against any number of microbial infectious agents.

The LPS forms tested were obtained from the mutualistic gut bacterium B. thetaiotaomicron and the oral and systemic pathogenic bacterium P. intermedia. Structurally, these forms are very similar to one another and to the B. fragilis LPS, previously determined to be of low toxicity (20). However, they differ from the S. Minnesota LPS and MPLA forms at key areas known to influence TLR4 activation, mainly in the length and number of acyl chains (Fig. 1). Although previous structure/function studies suggest that these penta-acyl LT-LPS forms should have decreased TLR4/MD2 signaling, the extra length in the acyl chains may help offset the loss of the sixth fatty acid chain within the MD2 hydrophobic pocket and allow activating interactions between these LPS forms and TLR4 (6). Each of the LT-LPS forms activated human MyD88- and TRIF-associated transcripts in primary human monocytes (Fig. 5), indicating agonistic signaling through human TLR4/MD2. When we included these LT-LPS forms as adjuvants for mice vaccinated with the alum-containing HBV vaccine, both BtLPS and PiLPS increased the titers and broadened the IgG subtypes produced during the antigen-specific antibody response. The broadened antibody response caused by the LPS forms therefore increased potential effector functions mediated by the induced HBsAg-specific antibodies. The effects on the antibody response were comparable to those obtained with SmMPLA, with no effects on the IgG1 titers (45–47). The development of IgG2b was observed regardless of the nature of the LPS form used. Therefore, naturally produced LT-LPS preparations were nearly as effective as SmMPLA at increasing the IgG differentiated class switching within the antigen-specific B cell population. Changes in the amount and the quality of the antibody repertoire are well-characterized indicators of differentiated CD4 T cell responses, because isotype switching requires help from CD4 T cells through cytokine production and cell surface interactions (46, 47). The demonstrated increase in CD4 T cell clonal expansion in the OTII/OTI adoptive-transfer model is consistent with inferred adjuvant activity on CD4 T cells.

Increases in early T cell clonal expansion after antigen stimulation were also noted using LT-LPS forms as the only adjuvant compounds present. The adjuvant-dependent increase was more evident in antigen-specific CD4 T cells than in CD8 T cells. The ability of activated T cells to migrate from the spleen and/or lymph nodes to extralymphoid organs, an effect that is strongly correlated with adjuvant treatment and increased T cell memory (42, 48), was measured using the LT-LPS forms during activation. Because the antigen remains in the lung after intravenous administration, the lung is an ideal extralymphoid site for this assay. The adjuvant-dependent increases in the numbers of CD4 (OTII) T cells in both the spleen and the lung were lower with the LT-LPS preparations than with either SmLPS or SmMPLA, but the effects were similar with the BtLPS and PiLPS treatments. Although the LT-LPS exerted a moderate adjuvant effect on CD4 (OTII) T cells, only a small adjuvant-dependent increase was noted for the CD8 T cells (OTI cells) in the same recipients. In fact, there was no increase in the number of lung CD8 T cells with either LT-LPS form over that for recipients given antigenic peptides alone. The observation of differing effects on CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells is reminiscent of previous results with this adoptive-transfer model, where TRIF-deficient recipients did not support TLR4 adjuvant-dependent expansion of CD8 OTI T cells, while CD4 OTII cells were only partially affected (25). That CD8 T cell expansion is more dependent on the set of signals provided through the TLR4/TRIF-dependent pathway than CD4 T cell expansion is supported by other studies demonstrating greater dependence of CD8 T cells than CD4 T cells on TLR4/TRIF signaling, and the associated production of type I IFN, for expansion and survival (49–51).

The selective deficit in CD8 T cell expansion with the LT-LPS could suggest poorer utilization of the TRIF signaling branch from TLR4, compared to that for classically defined TLR4/MD2 agonists. Decreased LPS activation of NF-κB in BtLPS-treated HEK293 cells expressing human TLR4/MD2 has been reported previously (6). Here we showed that BtLPS and PiLPS each increased the number of MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent transcripts in mouse BM-DC in a dose-dependent manner; however, the responses from both signaling branches required at least 10- to 100-fold more agonist to reach maximal induction than in the case of SmLPS. The decrease in potency for MyD88-dependent products with BtLPS or PiLPS was comparable to that obtained with SmMPLA. These differences in TLR4/MD2 potency and efficacy (Fig. 4) may help explain the decreased in vivo adjuvant effects, especially on the CD8 T cells. Many studies have shown that TRIF-dependent factors are required for increased CD8 T cell survival after activation, in addition to increased proliferation during the initial antigen encounter (25, 38, 49, 50). We have recently reported that TRIF-dependent production of type I IFN and the subsequent type I IFN-dependent increase in the number of costimulatory molecules on certain subsets of dendritic cells in vivo play key roles in CD8 T cell expansion, while CD4 T cells are not as responsive to type I IFN-dependent effects (51). Although deficits in CD8 expansion could be related to differences in antigen processing, the use of antigenic peptides in this study decreases the dependence of the CD8 T cell response on processing. Also, each of the adjuvant molecules utilizes the same receptor system, TLR4/MD2. Accordingly, any difference in peptide loading into major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules would reflect partial agonism of TLR4, and the diminished effects are still appropriately attributed to partial receptor agonism by the LT-LPS forms.

In summary, two naturally produced LT-LPS structures increased the scope of antigen-specific antibody responses to vaccine antigens and increased initial T cell clonal expansion. These LT-LPS preparations induced responses comparable to one another, and the antibody responses were similar to those induced with SmLPS and SmMPLA. The responses evoked indicate that these molecules truly act as immunological adjuvants for specific humoral immunity, with increased antibody titers and a broadened IgG subtype repertoire, but are likely unable to serve as adjuvants for cellular or cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-dependent responses, because they did not significantly increase initial CD8 T cell clonal expansion. The ability to induce such a characteristic response makes these LT-LPS forms particularly well suited to be adjuvants for chronic infectious agents, especially for intracellular parasites or bacteria, where Th1-like responses with various levels of dependence on complement-fixing antibody are required for clearance and protection, and where CD8 T cells can be pathogenic (52–57). Whether these adaptive immune patterns will hold true for LT-LPS from other organisms or for other weak or partial TLR4/MD2 agonists is undetermined. It is likely that the responses will depend on the abilities of individual structures of LT-LPS to induce the expression of important subsets of genes in the human TLR4/MD2 system (18).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the NIH grants NWRCE 5U54 A1057141 (to R.P.D.) and R01 AI071047 (to T.C.M.).

We thank Carolyn Casella for critical analysis of the paper and its results.

P.M.C. and D.M.H. performed and analyzed experiments. P.M.C. wrote the preliminary manuscript drafts. P.M.C., T.M.C., R.P.D., and T.T.T. contributed to experimental design and interpretation and manuscript revision. T.T.T. and R.P.D. isolated and purified the LT-LPS preparations in all experiments.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01150-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vella AT, McCormack JE, Linsley PS, Kappler JW, Marrack P. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide interferes with the induction of peripheral T cell death. Immunity 2:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skidmore BJ, Chiller JM, Morrison DC, Weigle WO. 1975. Immunologic properties of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS): correlation between the mitogenic, adjuvant, and immunogenic activities. J. Immunol. 114:770–775 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs DM. 1979. Synergy between T cell-replacing factor and bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the primary antibody response in vitro: a model for lipopolysaccharide adjuvant action. J. Immunol. 122:1421–1426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribi E. 1984. Beneficial modification of the endotoxin molecule. J. Biol. Response Mod. 3:1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldrick P, Richardson D, Elliott G, Wheeler AW. 2002. Safety evaluation of monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL): an immunostimulatory adjuvant. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 35:398–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coats SR, Berezow AB, To TT, Jain S, Bainbridge BW, Banani KP, Darveau RP. 2011. The lipid A phosphate position determines differential host Toll-like receptor 4 responses to phylogenetically related symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria. Infect. Immun. 79:203–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zähringer U, Salvetzki R, Wagner F, Lindner B, Ulmer AJ. 2001. Structural and biological characterisation of a novel tetra-acyl lipid A from Escherichia coli F515 lipopolysaccharide acting as endotoxin antagonist in human monocytes. J. Endotoxin Res. 7:133–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawahara K, Tsukano H, Watanabe H, Lindner B, Matsuura M. 2002. Modification of the structure and activity of lipid A in Yersinia pestis lipopolysaccharide by growth temperature. Infect. Immun. 70:4092–4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cekic C, Casella CR, Eaves CA, Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H, Mitchell TC. 2009. Selective activation of the p38 MAPK pathway by synthetic monophosphoryl lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 284:31982–31991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embry CA, Franchi L, Nunez G, Mitchell TC. 2011. Mechanism of impaired NLRP3 inflammasome priming by monophosphoryl lipid A. Sci. Signal. 4:ra28. 10.1126/scisignal.2001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, Guderian JA, Windish HP, Baldwin SL, Laughlin EM, Duthie MS, Fox CB, Carter D, Friede M, Vedvick TS, Reed SG. 2011. Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PLoS One 6:e16333. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson AG, Tomai M, Solem L, Beck L, Ribi E. 1987. Characterization of a nontoxic monophosphoryl lipid A. Rev. Infect. Dis. 9(Suppl. 5):S512–S516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara T, Ogawa T, Sobue S, Hamada S. 1990. Chemical, immunobiological and antigenic characterizations of lipopolysaccharides from Bacteroides gingivalis strains. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattsby-Baltzer I, Mielniczuk Z, Larsson L, Lindgren K, Goodwin S. 1992. Lipid A in Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 60:4383–4387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumada H, Haishima Y, Umemoto T, Tanamoto K. 1995. Structural study on the free lipid A isolated from lipopolysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2098–2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isogai H, Isogai E, Fujii N, Oguma K, Kagota W, Takano K. 1988. Histological changes and some in vitro biological activities induced by lipopolysaccharide from Bacteroides gingivalis. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A 269:64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reife RA, Coats SR, Al-Qutub M, Dixon DM, Braham PA, Billharz RJ, Howald WN, Darveau RP. 2006. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide lipid A heterogeneity: differential activities of tetra- and penta-acylated lipid A structures on E-selectin expression and TLR4 recognition. Cell. Microbiol. 8:857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Coats SR, Bumgarner RE, Darveau RP. 2007. Hierarchical gene expression profiles of HUVEC stimulated by different lipid A structures obtained from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 9:1028–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coats SR, Reife RA, Bainbridge BW, Pham TT, Darveau RP. 2003. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide antagonizes Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide at toll-like receptor 4 in human endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 71:6799–6807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancuso G, Midiri A, Biondo C, Beninati C, Gambuzza M, Macri D, Bellantoni A, Weintraub A, Espevik T, Teti G. 2005. Bacteroides fragilis-derived lipopolysaccharide produces cell activation and lethal toxicity via toll-like receptor 4. Infect. Immun. 73:5620–5627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munford RS. 2008. Sensing gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharides: a human disease determinant? Infect. Immun. 76:454–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham MD, Seachord C, Ratcliffe K, Bainbridge B, Aruffo A, Darveau RP. 1996. Helicobacter pylori and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharides are poorly transferred to recombinant soluble CD14. Infect. Immun. 64:3601–3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham MD, Bajorath J, Somerville JE, Darveau RP. 1999. Escherichia coli and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide interactions with CD14: implications for myeloid and nonmyeloid cell activation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. 1999. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 189:1777–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mata-Haro V, Cekic C, Martin M, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. 2007. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science 316:1628–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson BS, Mata-Haro V, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. 2005. Peptide-stimulated DO11.10 T cells divide well but accumulate poorly in the absence of TLR agonist treatment. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:3196–3208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson BS, Chilton PM, Ward JR, Evans JT, Mitchell TC. 2005. The low-toxicity versions of LPS, MPL adjuvant and RC529, are efficient adjuvants for CD4+ T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78:1273–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Didierlaurent AM, Morel S, Lockman L, Giannini SL, Bisteau M, Carlsen H, Kielland A, Vosters O, Vanderheyde N, Schiavetti F, Larocque D, Van Mechelen M, Garçon N. 2009. AS04, an aluminum salt- and TLR4 agonist-based adjuvant system, induces a transient localized innate immune response leading to enhanced adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 183:6186–6197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. 1992. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell 68:869–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. 1994. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 76:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. 1998. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol. Cell Biol. 76:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Qutub MN, Braham PH, Karimi-Naser LM, Liu X, Genco CA, Darveau RP. 2006. Hemin-dependent modulation of the lipid A structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 74:4474–4485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coats SR, Jones JW, Do CT, Braham PH, Bainbridge BW, To TT, Goodlett DR, Ernst RK, Darveau RP. 2009. Human Toll-like receptor 4 responses to P. gingivalis are regulated by lipid A 1- and 4′-phosphatase activities. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1587–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKee AS, Munks MW, MacLeod MK, Fleenor CJ, Van Rooijen N, Kappler JW, Marrack P. 2009. Alum induces innate immune responses through macrophage and mast cell sensors, but these sensors are not required for alum to act as an adjuvant for specific immunity. J. Immunol. 183:4403–4414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW. 2009. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:287–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deak E, Jayakumar A, Cho KW, Goldsmith-Pestana K, Dondji B, Lambris JD, McMahon-Pratt D. 2010. Murine visceral leishmaniasis: IgM and polyclonal B-cell activation lead to disease exacerbation. Eur. J. Immunol. 40:1355–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marrack P, Kappler J, Mitchell T. 1999. Type I interferons keep activated T cells alive. J. Exp. Med. 189:521–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson BS, Mitchell TC. 2004. Measurement of daughter cell accumulation during lymphocyte proliferation in vivo. J. Immunol. Methods 295:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengupta S, Jayaraman P, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. 2007. Unrestrained glycogen synthase kinase-3β activity leads to activated T cell death and can be inhibited by natural adjuvant. J. Immunol. 178:6083–6091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jenkins MK, Khoruts A, Ingulli E, Mueller DL, McSorley SJ, Reinhardt RL, Itano A, Pape KA. 2001. In vivo activation of antigen-specific CD4 T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:23–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reinhardt RL, Khoruts A, Merica R, Zell T, Jenkins MK. 2001. Visualizing the generation of memory CD4 T cells in the whole body. Nature 410:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Tsai JH, Wilson CB, Miller SI. 2002. Human Toll-like receptor 4 recognizes host-specific LPS modifications. Nat. Immunol. 3:354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowen WS, Minns LA, Johnson DA, Mitchell TC, Hutton MM, Evans JT. 2012. Selective TRIF-dependent signaling by a synthetic toll-like receptor 4 agonist. Sci. Signal. 5:ra13. 10.1126/scisignal.2001963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosewich M, Schulze J, Eickmeier O, Telles T, Rose MA, Schubert R, Zielen S. 2010. Tolerance induction after specific immunotherapy with pollen allergoids adjuvanted by monophosphoryl lipid A in children. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 160:403–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snapper CM, Paul WE. 1987. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science 236:944–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snapper CM, Peschel C, Paul WE. 1988. IFN-γ stimulates IgG2a secretion by murine B cells stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 140:2121–2127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khoruts A, Mondino A, Pape KA, Reiner SL, Jenkins MK. 1998. A natural immunological adjuvant enhances T cell clonal expansion through a CD28-dependent, interleukin (IL)-2-independent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 187:225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. 2005. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 174:4465–4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogasawara K, Hida S, Weng Y, Saiura A, Sato K, Takayanagi H, Sakaguchi S, Yokochi T, Kodama T, Naitoh M, De Martino JA, Taniguchi T. 2002. Requirement of the IFN-α/β-induced CXCR3 chemokine signalling for CD8+ T cell activation. Genes Cells 7:309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandhapudi SK, Chilton PM, Mitchell TC. 2013. TRIF is required for TLR4 mediated adjuvant effects on T cell clonal expansion. PLoS One 8:e56855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coban C, Ishii KJ, Uematsu S, Arisue N, Sato S, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Hisaeda H, Horii T, Akira S. 2007. Pathological role of Toll-like receptor signaling in cerebral malaria. Int. Immunol. 19:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belnoue E, Potter SM, Rosa DS, Mauduit M, Gruner AC, Kayibanda M, Mitchell AJ, Hunt NH, Renia L. 2008. Control of pathogenic CD8+ T cell migration to the brain by IFN-γ during experimental cerebral malaria. Parasite Immunol. 30:544–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brodskyn CI, Barral A, Boaventura V, Carvalho E, Barral-Netto M. 1997. Parasite-driven in vitro human lymphocyte cytotoxicity against autologous infected macrophages from mucosal leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 159:4467–4473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faria DR, Souza PE, Duraes FV, Carvalho EM, Gollob KJ, Machado PR, Dutra WO. 2009. Recruitment of CD8+ T cells expressing granzyme A is associated with lesion progression in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 31:432–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Hatam F, Heinzel FP, Bouvier J, Turck CW, Locksley RM. 1993. Targeted activation of CD8 cells and infection of β2-microglobulin-deficient mice fail to confirm a primary protective role for CD8 cells in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 151:2077–2086 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibson-Corley KN, Boggiatto PM, Mukbel RM, Petersen CA, Jones DE. 2010. A deficiency in the B cell response of C57BL/6 mice correlates with loss of macrophage-mediated killing of Leishmania amazonensis. Int. J. Parasitol. 40:157–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.