Abstract

During urinary tract infections (UTIs), uropathogenic Escherichia coli must maintain a delicate balance between sessility and motility to achieve successful infection of both the bladder and kidneys. Previous studies showed that cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) levels aid in the control of the transition between motile and nonmotile states in E. coli. The yfiRNB locus in E. coli CFT073 contains genes for YfiN, a diguanylate cyclase, and its activity regulators, YfiR and YfiB. Deletion of yfiR yielded a mutant that was attenuated in both the bladder and the kidneys when tested in competition with the wild-type strain in the murine model of UTI. A double yfiRN mutant was not attenuated in the mouse model, suggesting that unregulated YfiN activity and likely increased cytoplasmic c-di-GMP levels cause a survival defect. Curli fimbriae and cellulose production were increased in the yfiR mutant. Expression of yhjH, a gene encoding a proven phosphodiesterase, in CFT073 ΔyfiR suppressed the overproduction of curli fimbriae and cellulose and further verified that deletion of yfiR results in c-di-GMP accumulation. Additional deletion of csgD and bcsA, genes necessary for curli fimbriae and cellulose production, respectively, returned colonization levels of the yfiR deletion mutant to wild-type levels. Peroxide sensitivity assays and iron acquisition assays displayed no significant differences between the yfiR mutant and the wild-type strain. These results indicate that dysregulation of c-di-GMP production results in pleiotropic effects that disable E. coli in the urinary tract and implicate the c-di-GMP regulatory system as an important factor in the persistence of uropathogenic E. coli in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) organisms are the most prevalent isolates of patients with urinary tract infections (UTIs). Unlike many other bacterial infections, UTIs are common in young healthy women and are among the most frequently diagnosed infections in the United States (1–5). The contributions of colonization and virulence factors such as type I fimbriae, iron acquisition systems, and hemolysin to successful infection of the urinary tract by UPEC are well documented (6–14). However, the contribution of second messengers such as bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) to virulence have thus far not been well documented for UPEC. Given the recent advances in the understanding of the downstream effectors of c-di-GMP, interest in the role of c-di-GMP signaling in the virulence of bacterial pathogens has increased.

c-di-GMP is created by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) from two GTP molecules and is broken down to 5′-phosphoguanylyl-(3′-5′)-guanosine (pGpG) by specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Other enzymes are responsible for further breaking down pGpG to two GMP molecules. All DGCs possess the GGDEF (Gly-Gly-Asp-Glu-Phe) active-site domain, and PDEs are associated with the EAL (Glu-Ala-Leu) domain (15). Various external or internal stimuli are sensed by the DGCs and translated to the various c-di-GMP effector molecules to alter the behavior of the bacteria. Because c-di-GMP effectors are present at all levels of regulation, including transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational functions, c-di-GMP signaling can produce rapid responses to quickly changing environmental conditions. The most common alterations made by c-di-GMP signaling in E. coli are changes in motility and production of adhesins and exopolysaccharides. In general, increased levels of c-di-GMP decrease motility and increase multicellular community behaviors, while the reverse is true when c-di-GMP levels are low (16–27).

Groups working with nonpathogenic K-12 strains of E. coli have established a link between curli fimbria production and c-di-GMP levels (20, 28, 29). Curli fimbriae are coiled surface structures that promote both adhesion to surfaces as well as cell-cell interactions. The curli locus is organized in two divergent operons (csgDEFG and csgBA), and the transcriptional activator CsgD stimulates expression of csgBA as well as its own operon. CsgA is the major subunit of the curli fiber, and CsgB is needed for the nucleation of the CsgA oligomer. Increased levels of c-di-GMP lead to increased activity of CsgD, although this effect likely involves other intermediary proteins (20, 29–32). Various studies have demonstrated the ability of curli fimbriae to induce an immune response through Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) activation and generation of proinflammatory fibrinopeptides and by activating inducible nitric oxide synthase, a defense mechanism that produces large amounts of nitric oxide (33–35). Increased bacterial resistance to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in curli-fimbriated E. coli has also been demonstrated (36).

Increased activity of CsgD also indirectly affects the production of cellulose. Expression of adrA and yedQ, two genes that encode DGCs, is activated by CsgD. The subsequent production of c-di-GMP by either or both of the proteins AdrA and YedQ, depending on the strain of E. coli, stimulates increased activity of BcsA, the catalytic subunit of the cellulose biosynthetic machinery. Transcription levels of the cellulose operons (bcsEFG and yhjRQbcsABZC) do not seem to be affected by c-di-GMP levels (16, 20, 31, 37–39). Production of cellulose in concert with curli fimbriae seems to dampen the immune response produced by the curli fibers (36). The coproduction of these factors also produces a distinctive in vitro plate phenotype termed the rdar morphotype, for the red, dry and rough colonies observed on agar plates that contain Congo red dye (29). The rdar phenotype is similar to the small-colony variant (SCV) phenotype seen in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates.

This study investigated the links between the DGC YfiN and its activity regulator YfiR, first identified in a screen for loss of motility in E. coli K-12 (40), with changes observed in curli fimbriae production, cellulose production, and motility. The implications of the expression and activity of these systems for the virulence of UPEC strain CFT073 in the urinary tract were also assessed using the mouse model of UTI. Deletion of yfiR and subsequent increased activity of YfiN lead to increased production of curli fimbriae and cellulose and a near total loss of motility. We further show that these phenotypes lead to attenuation in the competitive mouse model of UTI. This is the first report to demonstrate that proper control of c-di-GMP production is essential for UPEC to mount successful infections in the urinary tract.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

E. coli strain CFT073 was isolated from a patient with pyelonephritis at the University of Maryland Medical System. Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB), morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) glycerol broth, tryptone broth (2 g tryptone and 1 g NaCl in 200 ml double-distilled water [ddH2O]), or filter-sterilized human urine collected from a female volunteer. Curli fimbriae and cellulose expression was determined by growth on modified LB agar plates (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 15 g agar per liter ddH2O with or without 40 μg/ml Congo red and 20 μg/ml Coomassie blue added after autoclaving) or urine agar plates (750 ml sterile human urine mixed with an autoclaved mixture of 15 g agar in 250 ml ddH2O with or without 40 μg/ml Congo red and 20 μg/ml Coomassie blue). Swimming motility was assessed in 0.3% tryptone agar plates (1 g tryptone, 0.5 g NaCl, and 0.3 g agar per 100 ml ddH2O), and swarming motility was assessed on 0.45% swarm agar (0.3 g meat extract, 1 g Bacto peptone, and 0.45 g agar per 100 ml ddH2O, with 0.5 g glucose added after autoclaving). Antibiotics were added in the following concentrations as appropriate: 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 200 μg/ml carbenicillin. A 10 mM concentration of arabinose was added to the media to induce expression from the pBAD promoter when necessary.

Construction of mutant strains, allelic repair, and complementation systems.

All primers used for the generation of deletion mutants and cloning are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All nonpolar gene deletions were performed using the λ-Red recombination system developed by Datsenko and Wanner (41). The PCR products used for transformations in CFT073 were generated off pKD3 or pKD4 templates using primers specific for the targeted gene. The kanamycin- or chloramphenicol-marked gene deletions were then transduced into a fresh CFT073 background using the EB49 transducing phage (42). The antibiotic resistance cassette used to replace the target gene was removed using a Flp recombinase encoded on pCP20 (41). All gene deletions were verified by PCR and loss of antibiotic resistance on LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic. The yfiR locus was repaired in the yfiR deletion mutant by insertion of the kanamycin cassette via λ-Red near, but outside, the yfiLRNB locus, being careful not to disrupt any other loci. The EB49 transducing phage was used to transduce the wild-type yfiLRNB locus into the yfiR deletion mutant background. Restoration of the locus was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Complementation of the yfiR deletion strain was obtained by cloning PCR-amplified yfiR into the NcoI-PstI restriction sites of pBAD24d. Sequencing of the resulting plasmid confirmed the insertion of yfiR. pBAD30-yhjH and pBAD30-yhjHE136A were obtained from Ute Römling (15). The lacZ transcriptional fusion strains used for the β-galactosidase assays were obtained using the pFUSE system (43). Briefly, approximated 500 bp of the 5′ end of the targeted gene was cloned into the XbaI/SmaI sites of pFUSE to link the gene to the plasmid-encoded lacZYA locus. The resulting plasmids were used in a tetraparental mating with two other strains carrying the transposase on a suicide plasmid for homologous recombination into a CFT073 ΔlacZ::Kan background strain. This method produces a transcriptional fusion of the lacZYA operon with the targeted gene in the CFT073 genome. Kanamycin and chloramphenicol were used to select positive strains, and inserts were verified by PCR and sequencing.

Murine model of UTI.

Colonization of the urinary tract was determined using the competitive murine model of urinary tract infection as described previously (44). CFT073ΔlacZYA was used as the wild-type strain, and the various mutants had an intact lacZYA locus. To select for piliated bacteria, all bacterial strains were grown statically in 3 ml LB at 37°C for 2 days. The pellicle formed on the rim of the test tube was then transferred to fresh LB, incubated for 2 more days, and, finally, passaged again to 40 ml LB for a final, 2-day incubation. The broths were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) ∼0.4 with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the wild-type strain and the mutant strain were mixed equally. The mixed broth was then pelleted and washed once in 1× PBS and resuspended in 500 μl 1× PBS. Isoflurane-anesthetized 6- to 7-week-old female Swiss Webster mice (Harlan, USA) were inoculated via urethral catheterization with 50 μl (∼108 CFU) mixed bacterial suspension. Mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation, and the bladder and kidneys were aseptically harvested in 1× PBS. The organs were homogenized, serially diluted in 1× PBS, and plated on MacConkey agar medium (Fisher, USA). Ratios of surviving strains were determined by counting white (wild-type) and red (mutant) colonies. Colonization levels were graphed and analyzed using a paired Wilcoxon signed-ranked test and Prism (GraphPad). Competitive indices were calculated by dividing mutant CFU by wild-type CFU from the mice and then dividing this ratio by the ratio of the mutant to the wild type in the original inoculum. All animal experiments were approved by the UW-Madison Animal Care and Use Committee.

β-Galactosidase assay.

All β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (20). Briefly, bacterial strains were grown on LB agar plates without salt and containing 200 μg/ml carbenicillin and 10 mM arabinose if necessary. Plates were incubated for 16 to 20 h at 30°C. The bacteria were then collected with cotton swabs and suspended in 3 ml tryptone broth without salt to an OD600 between 0.4 and 0.8. Five hundred microliters each broth was mixed with 500 μl Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 60 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, β-mercaptoethanol [pH 7.0]), 20 μl chloroform, and 10 μl 0.1% SDS and vortexed for 10 s. Samples were then incubated at 28°C for 5 min, and 200 μl 4-mg/ml o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) was then added. The reaction was stopped with 500 μl Na2CO3. The OD420 and OD550 were then recorded, and the Miller units were calculated according to the following equation: Miller units = 1,000 × {[OD420 − (1.75 × OD550)]/(t × V × OD600)}, where t is the reaction time in min and V is the volume of bacterial broth used in milliliters.

Congo red and calcofluor binding assays.

Congo red binding assays were performed as previously described (45). Briefly, strains were swabbed on LB agar plates without salt containing 200 μg/ml carbenicillin and 10 mM arabinose if necessary. Plates were incubated for 16 to 20 h at 30°C. The bacteria were collected with cotton swabs and suspended in 5 ml tryptone broth with 40 μg/ml Congo red (Sigma-Aldrich) and without NaCl. Samples were taken for dilution plating on LB plates, and broths were separated into two tubes and incubated with shaking at 37°C for 2 h. The bacteria were pelleted at 8,000 rpm, and the OD490 was determined for the supernatants. The amount of Congo red dye left in the supernatant was determined using a standard curve of known concentrations of the dye.

Congo red plates were used to determine the rdar morphotype of each strain as previously described (45). Strains were grown statically in 3 ml LB at 37°C for 2 days. The pellicle formed on the rim of the test tube was then transferred to fresh LB, incubated for 2 more days, and, finally, passaged again to 3 ml LB for a final 2-day incubation. Broths were dilution plated onto Congo red plates and incubated for 5 to 7 days at 30°C. Colony morphology was then recorded. To determine cellulose production, strains were streaked on LB plates without salt containing 200 μg/ml calcofluor (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 mM arabinose if necessary. Plates were grown at 30°C overnight before the results were recorded.

Western blot analysis of CsgA expression.

Strains were grown overnight at 30°C on LB plates without salt with carbenicillin and arabinose for induction of pBAD-yfiR strains. Bacteria were collected using cotton swabs and resuspended in 1 ml 1× PBS. A sample of each broth was taken for plate counts, and the remaining sample was prepared according to recommendations from the laboratory of Matt Chapman at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. The bacteria were pelleted at 8,000 rpm, resuspended in 100 μl 99% formic acid, and incubated for 10 min on ice. Samples were then evaporated to dryness using a Speedvac. Pellets were resuspended in 200 μl 2× CRACK buffer (4% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.2% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 200 mM dithiothreitol). The Precision Plus Protein dual standard (Bio-Rad, USA) and the samples were then loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE gels and run at 250 V for 3 h. Amounts loaded were normalized using the CFU obtained from the plate counts. Gels were either Coomassie stained or transferred to nitrocellulose at 40 V for 1 h. Nitrocellulose membranes were then blocked with 5% milk in 1× Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-CsgA antibody (1:7,000) (obtained courtesy of the Chapman laboratory) was added, and blots were incubated overnight at 4°C. Blots were then washed 3 times with 1× TBST and probed with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:20,000) in 5% milk in 1× TBST for 30 min at room temperature. Blots were washed with 1× TBST 3 more times and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (GE Healthcare, USA).

Motility assays.

Swimming motility was assessed in 0.3% agar tryptone plates. Strains were grown overnight at 37°C in tryptone broth. Broths were adjusted to an OD600 of ∼0.1 with fresh tryptone broth before 2 μl was injected in the center of the agar swim plates. Ten-microliter volumes of the same broths were placed on the surface of swarm agar plates to assess swarming motility. Swim plates were incubated for 12 h at 30°C, and swarm plates were incubated for 2 days at 30°C. Assays were independently repeated at least three times.

RESULTS

Predicted functions of the YfiLRNB system of E. coli CFT073 are similar to those of the YfiBNR system of P. aeruginosa.

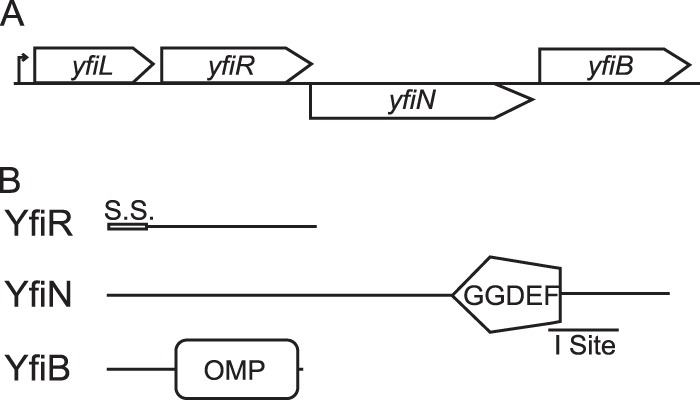

Recent reports on P. aeruginosa identified the YfiBNR system as a regulatory complex that plays a role in the development of the SCV phenotype important for persistence in a subcutaneous catheter model. YfiN was identified as an active membrane-associated DGC, and YfiR was identified as a periplasmic regulator of YfiN activity (46, 47). The authors proposed that YfiB sequesters YfiR to the outer membrane, which, in turn, relieves repression of YfiN activity (47). In the analogous operon, E. coli contains an additional gene, yfiL, that has no predicted function (Fig. 1A). Like their P. aeruginosa counterparts, E. coli YfiN has a predicted active-site domain with the conserved GGDEF sequence, while YfiR has a predicted signal sequence for export to the periplasm with a predicted cleavage site between amino acids 22 and 23 (Fig. 1B). YfiN also has a predicted allosteric inhibition site for feedback inhibition by c-di-GMP (Fig. 1B). However, the sequence identity at both the nucleotide and protein levels between the P. aeruginosa and E. coli proteins is low, with only 30% and 39% amino acid identity between the two predicted YfiR proteins and YfiN proteins, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Organization of the yfiLRNB locus and predicted protein functions. (A) The yfiLRNB locus consists of four genes that are expressed off a single predicted promoter. (B) YfiR is a predicted periplasmic protein of unknown function with a signal sequence (S.S.), and YfiN is a predicted membrane-bound diguanylate cyclase with an intact GGDEF active site and an allosteric inhibition site (I site). YfiL and YfiB are predicted lipoproteins of unknown function.

A yfiR mutant is attenuated in vivo.

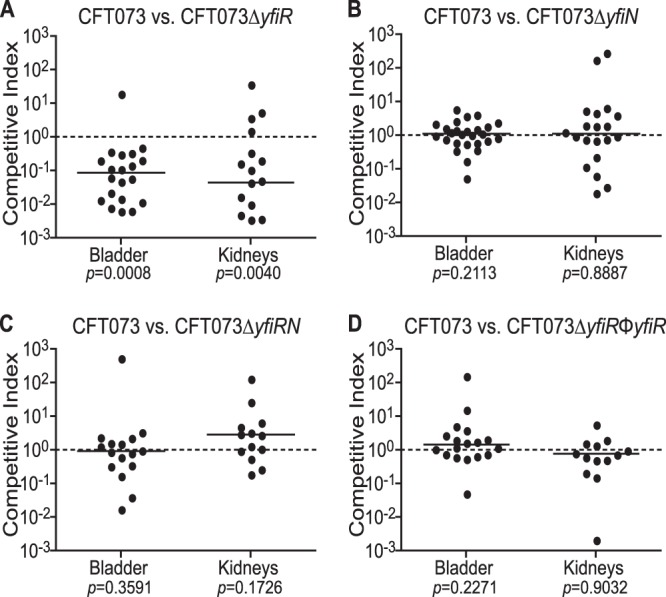

A yfiR mutant of P. aeruginosa was attenuated in the acute phase of a murine skin infection model (46). To test this phenotype in E. coli CFT073, a nonpolar yfiR deletion mutant was constructed and tested in competition with the wild-type strain in the murine model of urinary tract infection. As shown in Fig. 2, the yfiR mutant was attenuated in both the bladder (P = 0.0008) and kidneys (P = 0.004) at averages of 7.4-fold and 24.8-fold, respectively, at 48 h postinfection (Fig. 2A). Single deletions of yfiN (Fig. 2B), yfiL (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), and yfiB (see Fig. S1B) were not attenuated in vivo. Similarly, deletion of yfiN from the yfiR mutant rescued the competitive defect of the yfiR single mutant (Fig. 2C), suggesting that unrestricted activity of YfiN c-di-GMP production leads to attenuation in the urinary tract. Allelic restoration of the yfiR mutation to its wild-type form by transduction also resulted in loss of attenuation in vivo (Fig. 2D). Single infections with the yfiR mutant and wild-type CFT073 also showed that the yfiR mutant is carried at lower loads in the bladder and kidneys than the wild-type strain at 48 h postinfection (see Fig. S1C). Growth curves performed in LB, minimal media, and urine showed no difference in the growth rates between wild-type CFT073 and the yfiR mutant (see Fig. S2A). The yfiR mutant also competed like the wild-type strain in competitive LB broth and urine cultures (see Fig. S2B). These results indicate that a simple growth defect is unlikely to account for the attenuation of the yfiR mutant in the urinary tract.

Fig 2.

Deletion of yfiR causes attenuation in the mouse model of competitive UTI. Shown are results for coinfection of female Swiss Webster mice with CFT073 ΔyfiR (n = 21) (A), CFT073 ΔyfiN (n = 26) (B), CFT073Δ yfiRN (n = 16) (C), or the CFT073 ΔyfiR phage restoration mutant (n = 18) (D) and CFT073 ΔlacZYA using the mouse model of UTI. The competitive indices were calculated by the following equation: (yfi mutant CFU recovered/wild-type CFU recovered)/(mutant inoculum CFU/wild-type inoculum CFU). The solid line indicates the median value.

Growth on agar plates induces expression of the yfiRNB locus.

To determine the optimal conditions for expression of yfiR and yfiN, transcriptional fusions linking yfiR and yfiN to lacZYA were made using the pFUSE system (43). Strains were grown to exponential or late log phase in tryptone broth cultures or on LB agar plates overnight. β-Galactosidase assays were then performed on the strains. No expression was detected in the broth cultures (data not shown), but expression was detected when the strains were grown on the LB agar plates (see Fig. S3). This indicates that expression of the yfiRNB locus may be surface induced.

Deletion of yfiR causes a motility defect.

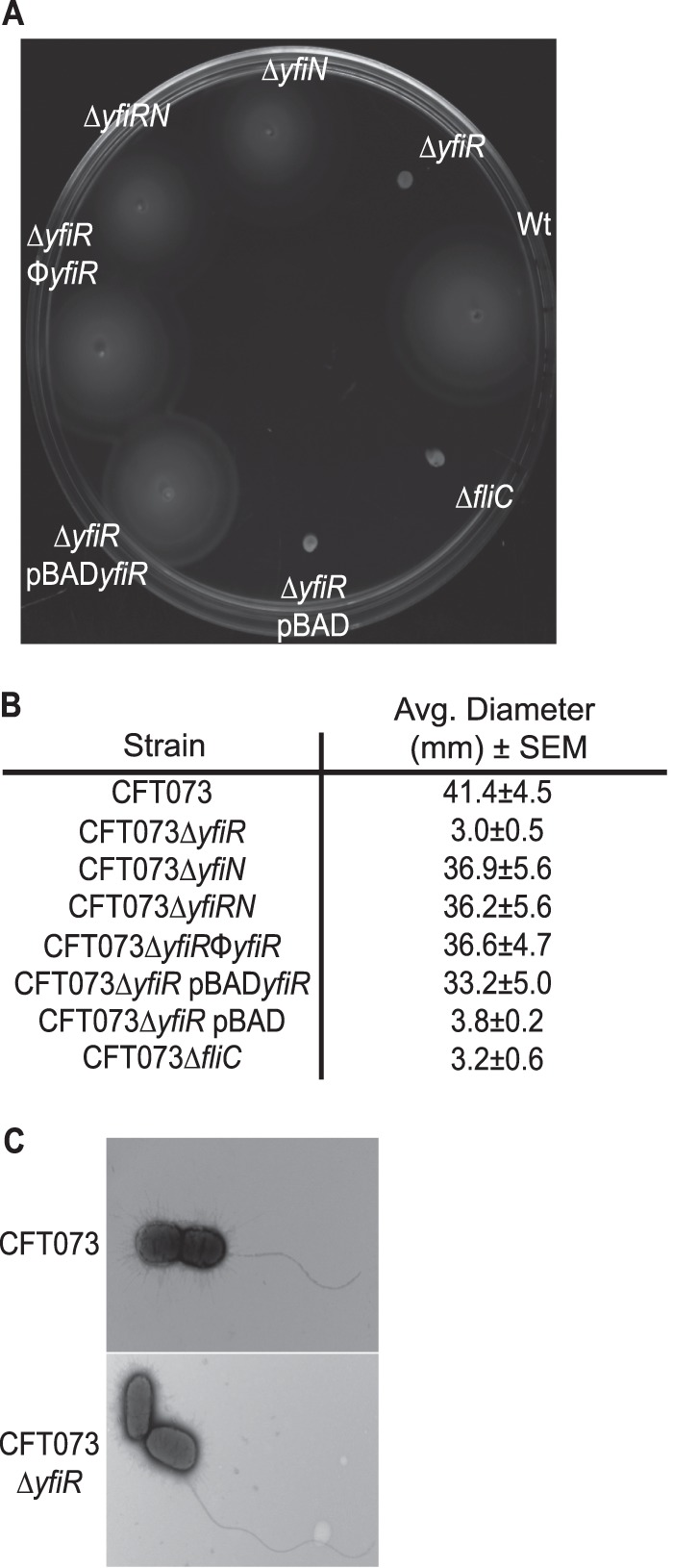

The detrimental effects of increased levels of c-di-GMP on motility are well documented (15, 22). To determine whether the mutant strains used in this study also displayed motility defects, the strains were grown in 0.3% tryptone swim plates and compared to the wild-type strain. A representative image of a swim plate and the average diameter of each strain's swim ring are shown in Fig. 3A and B. As expected, the yfiR mutant showed a drastic decline in its ability to swim out in the agar plates. The yfiN, as previously shown (48), and yfiRN mutants behaved like the wild-type strain. Complementation of the yfiR mutant with arabinose-induced pBADyfiR restored motility to the wild-type level, as did restoration of the yfi locus with a CFT073 transducing phage. The swimming defect observed with the yfiR deletion strain does not seem to be due to an inability to assemble the flagella. Intact flagellar filaments can be observed in electron micrographs of the cells, and motility is seen in live bacteria observed under a light microscope (Fig. 3C). This suggests that the motility defect observed in the agar swim plates for the yfiR deletion mutant may be caused by the bacteria becoming stuck in the agar rather than the complete lack of functional flagella.

Fig 3.

Motility phenotypes of mutants with alterations in the yfiLRNB locus. (A) Swim phenotype in 0.3% tryptone agar plates with 10 mM arabinose grown at 30°C. (B) Average diameters of swim rings of strains grown in 0.3% tryptone agar plates at 30°C. (C) Transmission electron micrographs of wild-type CFT073 and CFT073 ΔyfiR grown in 0.3% tryptone agar plates at 30°C and 37°C.

Deletion of yfiR causes increased production of cellulose and curli fimbriae.

In other strains of E. coli, as well as other species of bacteria, an increase in c-di-GMP levels usually results in increased fimbriation and exopolysaccharide production. E. coli strains specifically upregulate production of curli fimbriae and cellulose (15, 20, 22, 29, 49). A phenotypic assay to test whether curli fimbriae and cellulose are being produced involves plating the bacteria on LB plates that contain Congo red dye but lack salt. After 5 to 8 days of growth, colonies that express both products will have a deep red, rugose phentotype that is referred to as the rdar morphotype (for red, dry and rough). Colonies that produce only curli fimbriae will lack the rugose characteristic but will still be deep red and slightly rough. Expression of cellulose only results in a rugose colony that is pink instead of deep red, and loss of expression of both products results in a colony that is white and smooth (29, 50). Wild-type CFT073 and the yfiRNB locus mutants were grown for 6 days in LB at 37°C without shaking before serial dilution and plating on LB Congo red plates. The colony phenotypes obtained for each strain under these conditions are shown in Fig. 4A. All colonies obtained for the yfiR deletion mutant displayed the rdar morphotype, while the wild-type strain and the yfiN and yfiRN deletion mutants produced a mix of rdar and smooth and white colonies. Both the rdar and the smooth and white colony types of the wild-type strain would give a mixture of smooth and white and rdar colonies when replated on fresh LB Congo red plates (data not shown). The two distinct colony types obtained for the wild-type strain and their ability to revert to the opposite morphology suggest that at some point during their growth, the bacteria commit to a regulated state that results in either the production or suppression of curli and cellulose. It is not clear at this time what the signal(s) may be that promotes either state or how those signals are propagated through the progeny to ultimately produce a colony that is either all rdar or all smooth and white. Restoration of the yfiR mutation via transduction returned the phenotype of the yfiR deletion mutant to a mixture of both rdar and smooth and white colonies (Fig. 4A and B). Phenotypes on plates containing calcofluor, a fluorescent dye that binds cellulose, confirmed that yfiR deletion strains produce cellulose (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Overexpression yfiR carried on pBAD in the CFT073Δ yfiR background produced all smooth colonies, although most were slightly rough in the center, presumably from loss of arabinose induction as a result of metabolism (see Fig. S5A). Congo red binding assays were also performed on lawns of bacteria grown overnight at 30°C on LB agar plates without NaCl. As expected, the yfiR mutant bound more Congo red dye per CFU than the other strains, and this increase in bound Congo red was mitigated either by restoration of the mutated yfi locus to the wild type or by plasmid-expressed yfiR (Fig. 4C).

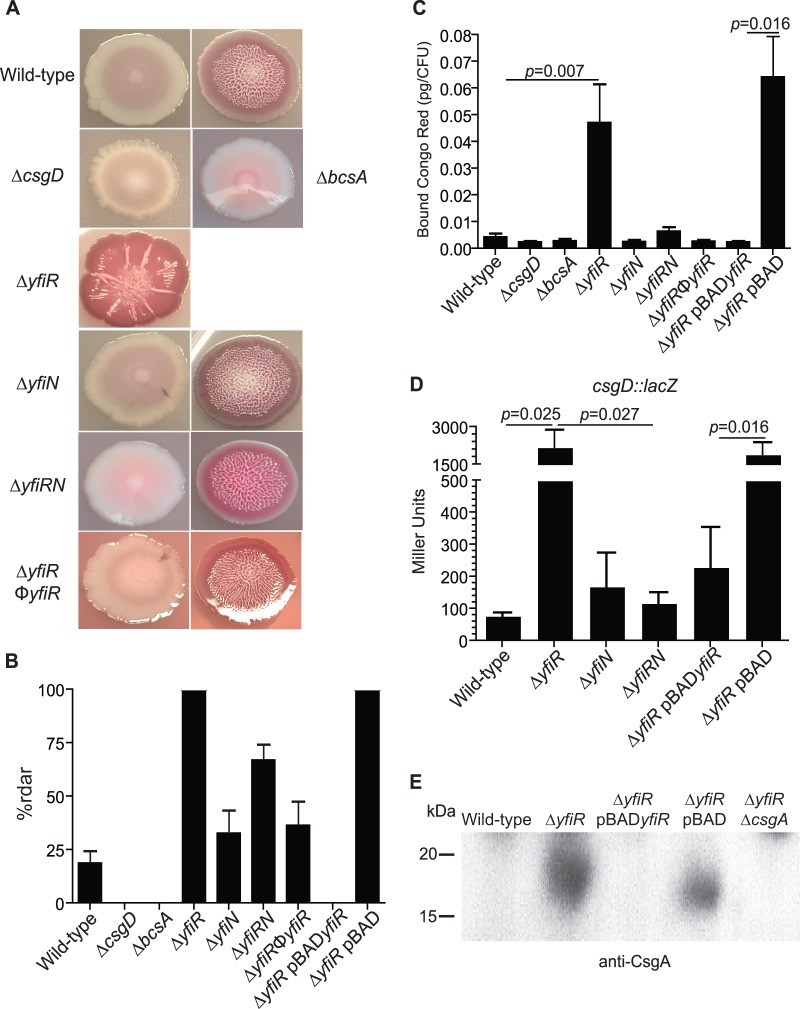

Fig 4.

Curli fimbriae and cellulose production are increased in CFT073 ΔyfiR. (A) Phenotypes of yfiLRNB locus mutants grown on LB Congo red plates at 30°C. All colony phenotypes that were observed are pictured. (B) Percentage of mutant colonies from the LB Congo red plates displaying the rdar phenotype. (C) Congo red binding assay in liquid broth. The amount of Congo red dye bound is presented as pg of bound dye per CFU. P values were calculated using Student's t test. (D) β-Galactosidase assays performed on wild-type CFT073 and CFT073ΔyfiR strains with the csgD::lacZYA transcriptional fusion. P values were calculated using Student's t test. (E) Western blot of acid-treated, whole-cell preparations grown on LB no-salt plates at 30°C. A rabbit anti-CsgA antibody was used to detect CsgA monomers.

To determine whether deletion of yfiR altered expression of csgD, the promoterless lacZYA locus was inserted directly downstream of csgD to create a transcriptional fusion using the pFUSE system (43). Expression levels of csgD could then be monitored by β-galactosidase assays. Deletion of yfiR resulted in a drastic increase in the Miller units expressed off the csgD operon (Fig. 4D). Deletion of both yfiR and yfiN in the csgD::lacZYA strain returned csgD expression to wild-type levels, as did complementation with pBADyfiR in the yfiR deletion strain (Fig. 4D). Increased production of the curli fibrils was verified by Western blotting using an antibody specific for CsgA, the major curlin subunit (Fig. 4E). Electron micrographs of the wild-type and yfiR mutant strains also showed an increase in what appear to be curli fibrils in the yfiR mutant (see Fig. S6). Plate phenotypes and expression of the adrA operon suggested that expression of adrA, but not yedQ (data not shown), is affected by CsgD activity (see Fig. S5A and B). Expression off the bcs operon was also monitored using the same system to place lacZYA downstream of bcsA. However, bcsA and bcsE expression levels in the mutant strains remained unchanged from the wild-type strain (see Fig. S7). This is not surprising given that c-di-GMP is thought to bind directly to BcsA to increase its activity levels and, thus, elevate cellulose production.

As CFT073 did not form a robust biofilm in plastic plates in our hands, pellicle formation on sterile glass test tubes was monitored as the closest equivalent to the biofilm plate assay. Deletion of yfiR dramatically increased pellicle formation. As in the Congo red binding assay, additional deletion of yfiN or complementation with a plasmid-borne copy of yfiR in the yfiR deletion mutant returned pellicle formation to the wild-type level (see Fig. S8A and B).

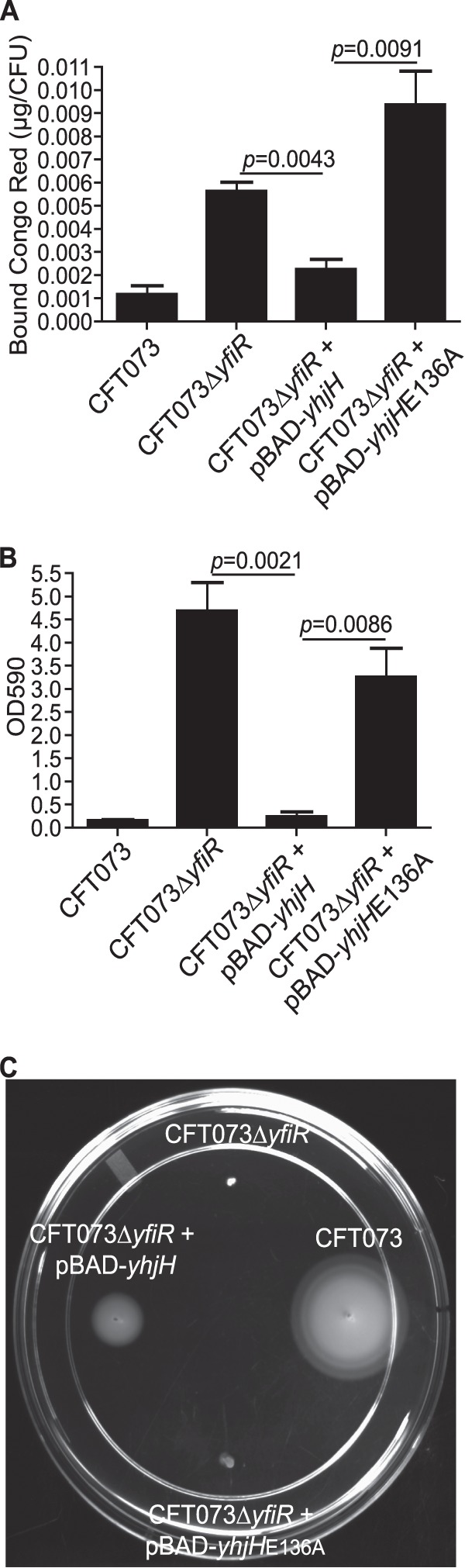

Expression of a phosphodiesterase reverses the phenotype of CFT073 ΔyfiR to the wild type.

The increase in curli fimbriae and cellulose production and pellicle formation in the yfiR deletion strain is likely due to increased levels of c-di-GMP. To test whether this is the case, wild-type yhjH, which encodes a proven phosphodiesterase (15), was expressed from a plasmid in CFT073 ΔyfiR and tested in the Congo red binding assay, pellicle formation assay, and swimming motility assay. As predicted, expression of yhjH reduced the amount of Congo red dye bound, reduced pellicle formation, and increased swimming motility in comparison to the yfiR deletion strain (Fig. 5). Expression of the yhjHE136A mutant, an active-site mutant that cannot break down c-di-GMP, did not have an effect on any of the noted phenotypes when expressed in the yfiR deletion strain, indicating that the phosphodiesterase activity and the resulting reduction in c-di-GMP levels are indeed required for the reversal of the observed phenotypes (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Expression of yhjH reverts the CFT073 ΔyfiR phenotypes to the wild-type forms. (A) Congo red binding assay in liquid broth. Expression of yhjH from pBAD plasmids was induced with 10 mM arabinose. P values were calculated using Student's t test. (B) Optical density of crystal violet stain bound and released from pellicles formed by each strain after growth in MOPS glycerol broths for 16 h at 37°C. Expression of yhjH from pBAD plasmids was induced with 10 mM arabinose. P values were calculated using Student's t test. (C) Swim phenotype in 0.3% tryptone agar plates with 10 mM arabinose grown at 30°C.

Deletion of yfiR does not increase sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide or iron limitation.

Past reports indicate that increased levels of c-di-GMP lead to an increase in sensitivity to peroxide stress and a decrease in the expression of iron acquisition genes (31, 51, 52). To determine if the yfiR mutant was more sensitive to peroxides than wild-type CFT073, hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assays were performed in both liquid culture and disc diffusion agar. No differences between the wild-type strain and the yfiR mutant were observed in either assay (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). To determine whether the yfiR deletion mutant would have trouble growing in an iron-limited environment like the host, both the wild-type and mutant strains were grown in LB with 2,2-dipyridyl, an iron chelator. Again, no differences in growth were observed between the wild-type and yfiR mutant strains (see Fig. S10).

Deletion of ycgR in the yfiR mutant partially restores colonization levels in the mouse model.

Motility is a known fitness trait of uropathogenic E. coli strains in the urinary tract and is needed for ascension of the ureters to reach the kidneys (13, 53, 54). Recent studies indicate that YcgR can bind c-di-GMP and then interact with the flagellar motor. This interaction acts to either inhibit rotation or keep the flagella turning counterclockwise, causing smooth-swimming cells that may become stuck in the agar matrix (55, 56). To determine whether the swimming defect seen in the yfiR mutant causes the attenuated phenotype in vivo, ycgR was deleted from the yfiR mutant and tested in the competitive mouse model of UTI. Swim plates of this mutant confirmed that motility was partially restored (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). As shown in Fig. 6A, this partial restoration of motility did not result in recovery of the yfiR deletion mutant to wild-type colonization levels in vivo. By itself, a single ycgR deletion mutant was not attenuated in the competitive mouse model against wild-type CFT073 (see Fig. S12A). Given that the colonization levels were not restored, full motility may be needed for full virulence, or another factor may also be partially responsible for the observed attenuation of the yfiR deletion mutant.

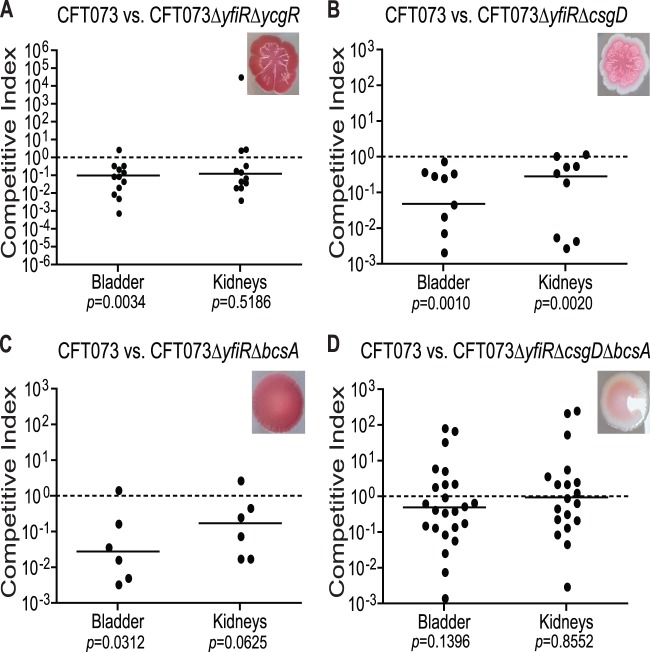

Fig 6.

Deletion of both bcsA and csgD from the yfiR deletion mutant restores fitness to wild-type CFT073 levels in the mouse model of competitive UTI. Shown are results for coinfection of female Swiss Webster mice with CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔycgR (n = 14) (A), CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔcsgD (n = 11) (B), CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔbcsA (n = 7) (C), or CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔcsgD ΔbcsA (n = 24) (D) and CFT073 ΔlacZYA using the mouse model of UTI. The insets show the phenotypes of the mutants on Congo red plates grown at 30°C. The competitive indices were calculated by the following equation: (yfi mutant CFU recovered/wild-type CFU recovered)/(mutant inoculum CFU/wild-type inoculum CFU). The solid line indicates the median value.

Deletion of both bcsA and csgD in the yfiR mutant returns colonization to wild-type levels.

Previous studies have shown that curli fibers produce an immune response by activating the host coagulation system and thus promoting an influx of white blood cells (34). However, curli fimbriae can also promote resistance to the host antimicrobial peptide LL-37 (36). Additional mutations in the yfiR deletion strain were therefore made to determine if the increased expression of curli fimbriae, or possibly even the increase in cellulose production, could be responsible for the attenuation of the yfiR deletion strain in vivo. Deletion of csgD or bcsA from the yfiR mutant did not return colonization to wild-type levels in the competitive UTI model, although perhaps a slight improvement in the mutant fitness is seen in the kidneys for both double-deletion strains (Fig. 6B and C). Strains with single deletions of csgD or bcsA competed like the wild-type strain in vivo (see Fig. S12B and C). Additional deletion of csgD from the ΔyfiR ΔycgR double-deletion strain also did not relieve the attenuated phenotype in the mouse model (see Fig. S12D). However, when both csgD and bcsA were deleted from the yfiR mutant, colonization was restored to wild-type levels (Fig. 6D). The motility of the double and triple mutants was determined using tryptone swim plates, on which they remained poorly motile like the yfiR single mutant (see Fig. S11). All mutant strains were also tested on calcofluor plates, which showed that only deletion of bcsA from a yfiR deletion strain eliminated cellulose production (see Fig. S13).

Urine inhibits the rdar morphotype and csgD expression.

In addition to growing the mutant strains on LB Congo red plates, we inoculated them on urine agar Congo red plates to see whether exposure to urine caused a change in the rdar phenotype. All of the wild-type CFT073 colonies grown on the urine Congo red plates displayed a smooth and white phenotype, indicating that urine represses the expression or activity of the proteins needed for production of cellulose and curli fimbriae (see Fig. S14A in the supplemental material). Similar results were obtained when the wild-type strain was grown in liquid urine and then plated on LB Congo red plates (see Fig. S14B), suggesting that the effect urine has on the regulatory controls for curli fimbriae and cellulose are long-lasting. The change was not permanent, though, because a return of the rdar phenotype was observed after growth in LB liquid culture followed by growth on LB Congo red plates (data not shown). Congo red plates that combined urine and LB were also tested with the wild-type strain as a control to ensure that the loss of the rdar phenotype was not due to growth inhibition on the urine-only plates (see Fig. S14A). The presence of urine also affected the phenotype of the yfiR mutant on the urine Congo red plates, but all colonies were still deep red and somewhat rugose (see Fig. S14A), which indicated that curli fimbriae and cellulose were both still being produced. Growth in liquid urine followed by growth on LB Congo red plates produced no differences in the rdar phenotype for the yfiR mutant (see Fig. S14B). Salt (NaCl) is a known inhibitor of the rdar phenotype (29, 57). To determine which salts found in urine might be responsible for the all-smooth-and-white phenotype seen in wild-type CFT073, individual salt components of urine [NaCl, Ca3(PO4)2, K2SO4, KCl, KHCO3, MgCO3, and MgSO4] at their physiological concentrations were added to LB Congo red plates for testing with the wild-type strain. Of the salts tested, only NaCl produced a phenotype similar to that found on the urine Congo red plates (see Fig. S14A).

To determine whether urine and NaCl affected the expression of csgD, the wild-type and yfiR mutant csgD::lacZYA strains were employed. β-Galactosidase assays performed on cells grown on urine plates showed a decrease in expression from the csg promoter in the presence of urine compared to LB, although this change was not yfiR dependent. However, expression levels in the yfiR mutant remained elevated compared to those in the wild-type strain under all conditions tested (see Fig. S14C in the supplemental material). Growth on LB-NaCl plates caused no change in expression compared to growth on LB-only plates (see Fig. S14C).

DISCUSSION

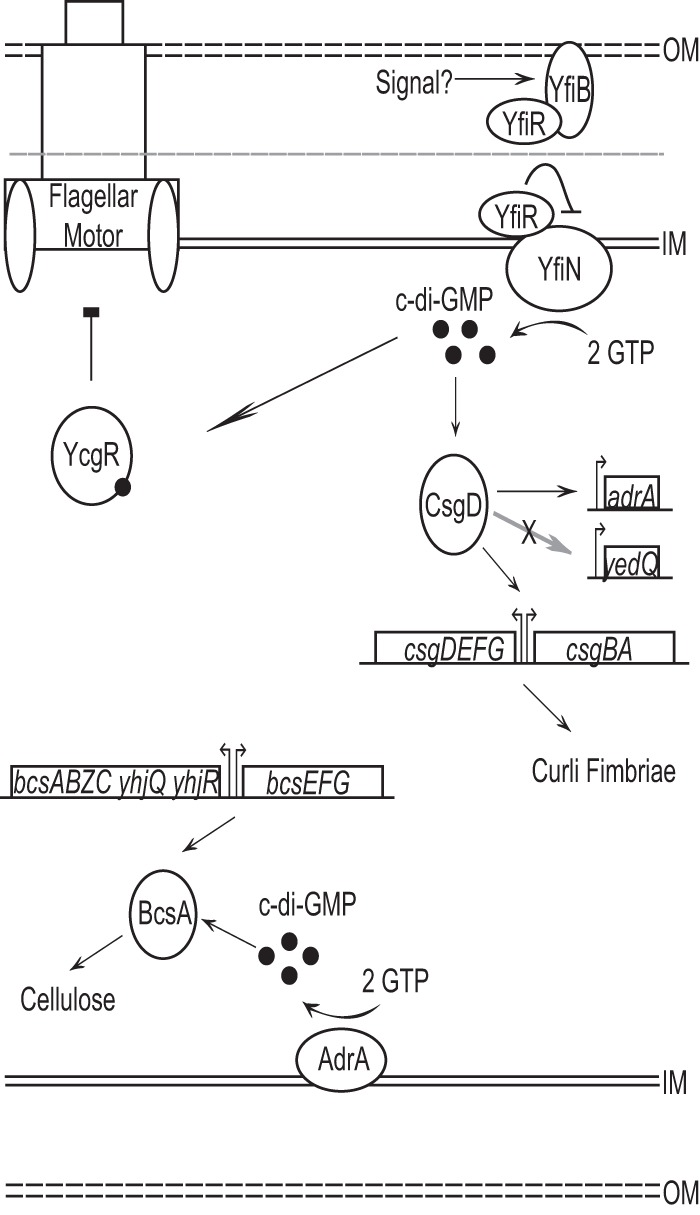

We set out to study the effect of altering the levels of the signaling molecule c-di-GMP on the pathogenesis of the model uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073. We suggest in this report that loss of periplasmic YfiR relieves inhibition of the activity of the membrane-bound DGC YfiN, and this leads to an elevation in cellular c-di-GMP levels (Fig. 7). Loss of yfiR and the presumed increase in c-di-GMP levels then lead to an increase in production of both curli fimbriae and cellulose, a reduction in swimming motility, and, ultimately, attenuation in the mouse model of UTI. Spurbeck et al. found that deletion of yfiN decreased adherence of CFT073 to cultured human bladder epithelial cells (48). However, single deletions of yfiL, yfiB, or yfiN in this study did not attenuate E. coli CFT073 in vivo. This discrepancy may be explained by the expression of other fimbriae by CFT073 that may compensate for any loss of curli-mediated binding in vivo. It is also possible that the human bladder cells used by Spurbeck et al. and the bladder epithelium of the Swiss Webster mice express different receptors that allow for binding by different sets of fimbriae; thus, fimbriae that are important for establishing infection in the human bladder may differ from those necessary for the colonization of the mouse bladder. Additional deletion of yfiN from the yfiR deletion strain or allelic restoration of the yfiR deletion strain brought urinary tract colonization back to wild-type CFT073 levels. This indicates that YfiR exerts an inhibitory effect on the activity of YfiN that is important for maintaining control of c-di-GMP levels in vivo. Without this control of c-di-GMP signaling, the bacteria become impaired in their ability to colonize the urinary tract.

Fig 7.

Model of the putative YfiLRNB system and its downstream effects on curli and cellulose production. YfiR is a predicted periplasmic inhibitor of YfiN diguanylate cyclase activity. In the absence of YfiR, YfiN produces c-di-GMP, which, in turn, increases the production of curli fimbriae and cellulose and inhibits motility. CsgD, AdrA, BcsA, and YcgR are all predicted to interact directly or indirectly with c-di-GMP to produce the indicated phenotypes.

A study of the homologous P. aeruginosa system postulated that YfiR prevents the dimerization of YfiN, a state that is necessary for activity of most DGCs. The follow-up report further indicated that YfiB sequesters YfiR, which would inhibit its ability to disrupt YfiN dimerization (47). Overall, though, the function of YfiB and the mechanism by which the YfiRNB system operates are still largely unknown. Further studies would be necessary to determine the hierarchy of the YfiRNB system and the set of external stimuli that may activate or repress YfiN activity. Our work also indicates that at least transcription of the yfi locus may be surface induced in CFT073. If attachment to the host epithelium also induces expression of this locus, the regulation of both yfiLRNB transcription and YfiN activity could give insights into the series of events necessary for successful colonization of and persistence in the urinary tract.

The downstream targets of increased c-di-GMP levels in E. coli CFT073 are similar to those that were previously described for other E. coli strains (22). The loss of yfiR resulted in decreased motility, increased expression of the csgD promoter, and increased production of both curli fimbriae and cellulose. Expression of yhjH, which encodes a phosphodiestrase, in the CFT073 ΔyfiR background returned these phenotypes to the wild type. The phosphodiesterase activity of YhjH was required for this reversal, suggesting that an increased c-di-GMP level is indeed the factor driving the increased expression of curli fimbriae and cellulose and the observed decrease in motility in the yfiR deletion strain. The motility defect of the yfiR deletion strain was partially rescued by additional deletion of ycgR. YcgR is capable of interacting with the flagellar motor to either promote smooth swimming or act as a braking mechanism when it is bound to c-di-GMP (55, 56). Deletion of ycgR therefore prevented alteration of flagellar rotation by this mechanism. Although the additional deletion of ycgR partially relieved the attenuation of the motility phenotype, the CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔycgR strain was still attenuated in the urinary tract. This observation indicates that the motility defect did not contribute to the in vivo attenuation. However, motility may be just one factor involved in the attenuation of the yfiR deletion mutant, and restoration of motility alone may not have been enough to rescue colonization to wild-type levels in vivo.

Included in these possible contributing factors, the elevated production of curli fimbriae and cellulose also appears to have a detrimental effect on the colonization ability of CFT073. The link between the expression of csgD and the activity of the cellulose biosynthetic machinery was established previously in E. coli K-12 strains. CsgD not only activates expression of the curli operon but also activates expression of adrA and yedQ, genes that encode DGCs. The c-di-GMP produced by either AdrA or YedQ would then stimulate increased activity of the cellulose synthetic machinery by binding to components of its core catalytic module (29, 39, 50). Deletion of adrA in CFT073, but not yedQ, resulted in a loss of cellulose production on LB Congo red plates. Therefore, we postulate that AdrA expression stimulated by CsgD activity is the likely link involved in CsgD-dependent increases of cellulose production in E. coli CFT073.

Curli fibers are known activators of the host coagulase system that leads to increased influx of immune cells and inflammation (34). Another report also implicated the expression of curli fimbriae in the absence of cellulose production as an immune stimulant that results in increased clearance of uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89 from the urinary tract (36). In contrast to these reports, a CFT073 ΔyfiR ΔcsgD mutant was still attenuated in the competitive mouse model of UTI even though it was confirmed that curli fimbriae were no longer being produced. Only additional deletion of bcsA from the ΔyfiR ΔcsgD mutant rescued the attenuated phenotype. Although the yfiR single-deletion mutant did not display any growth defects in vitro in various media when grown singly or in competition with the wild-type strain, it is possible that the increased stress of the urinary tract environment resulted in the attenuation of the metabolically overburdened mutant. The significant amount of cellular resources being consumed for the production of large and unnecessary amounts of curli fimbriae and cellulose may divert resources away from the production of other virulence or colonization factors vital for infection of the urinary tract. Further studies into alterations in the global production of bacterial proteins in the yfiR deletion mutant could give insight into whether the expression of any other virulence factors was altered.

Given that single deletions of csgD or bcsA did not attenuate CFT073 in vivo, biofilm formation associated with curli or cellulose is likely not a persistence factor involved in colonization in the urinary tract. Additionally, growth in urine decreases expression of csgD and inhibits the rdar morphology. The salt content of urine appears to be the main suppressor leading to this outcome. Growth at 37°C also inhibits the production of these biofilm components (data not shown). Although curli and cellulose may be produced during UTIs, these data suggest that robust curli and cellulose-dependent biofilms are not formed by E. coli CFT073 in our mouse model of UTI and may instead be more important for adaptation and persistence in environments outside the urinary tract.

This study not only emphasizes the importance of regulation of curli fimbriae, cellulose production, and motility in the virulence of UPEC in the urinary tract but also highlights c-di-GMP production as a key regulator of these products. Although the bacteria seem to survive well in the short term in the absence of curli fimbriae and cellulose, these molecules could still play a role in the persistence of the bacteria in the urinary tract during chronic infections. Given the abundance of DGCs (∼19) and PDEs (∼17) in E. coli, c-di-GMP most likely also plays an important role in the survival of the bacteria in vivo. Further studies into the distinct or perhaps redundant roles played by the various DGCs and PDEs should illuminate the steps in the fine-tuned control that the bacteria have over the expression of their colonization and virulence factors to mount successful infections in the host.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK063250-06 and by the National Institutes of Health, National Research Service Award AI55397.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01396-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacheller CD, Bernstein JM. 1997. Urinary tract infections. Med. Clin. North Am. 81:719–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faro S, Fenner DE. 1998. Urinary tract infections. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 41:744–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooton TM. 2000. Pathogenesis of urinary tract infections: an update. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46(Suppl 1):1–7; discussion, 63–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunin CM. 1994. Urinary tract infections in females. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:1–10; quiz, 11–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orenstein R, Wong ES. 1999. Urinary tract infections in adults. Am. Fam. Physician 59:1225–1234, 1237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Buckles EL, Lockatell CV, Hebel JR, Johnson DE, Tang CM, Donnenberg MS. 2002. Type 1 fimbriae and extracellular polysaccharides are preeminent uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence determinants in the murine urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1079–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg MS, Welch RA. 1996. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, p 135–174 Mobley HLT, Warren JW. (ed), Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia EC, Brumbaugh AR, Mobley HL. 2011. Redundancy and specificity of Escherichia coli iron acquisition systems during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 79:1225–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kau AL, Hunstad DA, Hultgren SJ. 2005. Interaction of uropathogenic Escherichia coli with host uroepithelium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielubowicz GR, Mobley HL. 2010. Host-pathogen interactions in urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 7:430–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith YC, Rasmussen SB, Grande KK, Conran RM, O'Brien AD. 2008. Hemolysin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli evokes extensive shedding of the uroepithelium and hemorrhage in bladder tissue within the first 24 hours after intraurethral inoculation of mice. Infect. Immun. 76:2978–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiles TJ, Kulesus RR, Mulvey MA. 2008. Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 85:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright KJ, Seed PC, Hultgren SJ. 2005. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli flagella aid in efficient urinary tract colonization. Infect. Immun. 73:7657–7668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto S, Nakata K, Yuri K, Katae H, Terai A, Kurazono H, Takeda Y, Yoshida O. 1996. Assessment of the significance of virulence factors of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in experimental urinary tract infection in mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:607–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simm R, Morr M, Kader A, Nimtz M, Romling U. 2004. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1123–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amikam D, Galperin MY. 2006. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22:3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Argenio DA, Miller SI. 2004. Cyclic di-GMP as a bacterial second messenger. Microbiology 150:2497–2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengge R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenal U, Malone J. 2006. Mechanisms of cyclic-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40:385–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kader A, Simm R, Gerstel U, Morr M, Romling U. 2006. Hierarchical involvement of various GGDEF domain proteins in rdar morphotype development of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 60:602–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills E, Pultz IS, Kulasekara HD, Miller SI. 2011. The bacterial second messenger c-di-GMP: mechanisms of signalling. Cell. Microbiol. 13:1122–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Povolotsky TL, Hengge R. 2012. ‘Life-style' control networks in Escherichia coli: signaling by the second messenger c-di-GMP. J. Biotechnol. 160:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Römling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. 2005. c-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57:629–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Romling U, Gomelsky M. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP. The PilZ domain protein controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30310–30314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 187:1792–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe AJ, Visick KL. 2008. Get the message out: cyclic-Di-GMP regulates multiple levels of flagellum-based motility. J. Bacteriol. 190:463–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan H, Chen W. 2010. 3′,5′-Cyclic diguanylic acid: a small nucleotide that makes big impacts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39:2914–2924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bokranz W, Wang X, Tschape H, Romling U. 2005. Expression of cellulose and curli fimbriae by Escherichia coli isolated from the gastrointestinal tract. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:1171–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Römling U. 2005. Characterization of the rdar morphotype, a multicellular behaviour in Enterobacteriaceae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:1234–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammar M, Arnqvist A, Bian Z, Olsen A, Normark S. 1995. Expression of two csg operons is required for production of fibronectin- and congo red-binding curli polymers in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 18:661–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brombacher E, Baratto A, Dorel C, Landini P. 2006. Gene expression regulation by the curli activator CsgD protein: modulation of cellulose biosynthesis and control of negative determinants for microbial adhesion. J. Bacteriol. 188:2027–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Römling U, Bian Z, Hammar M, Sierralta WD, Normark S. 1998. Curli fibers are highly conserved between Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli with respect to operon structure and regulation. J. Bacteriol. 180:722–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsén A, Jonsson A, Normark S. 1989. Fibronectin binding mediated by a novel class of surface organelles on Escherichia coli. Nature 338:652–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson K, Russell W, Morgelin M, Herwald H. 2003. The conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin at the surface of curliated Escherichia coli bacteria leads to the generation of proinflammatory fibrinopeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 278:31884–31890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tükel C, Nishimori JH, Wilson RP, Winter MG, Keestra AM, van Putten JP, Bäumler AJ. 2010. Toll-like receptors 1 and 2 cooperatively mediate immune responses to curli, a common amyloid from enterobacterial biofilms. Cell. Microbiol. 12:1495–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kai-Larsen Y, Luthje P, Chromek M, Peters V, Wang X, Holm A, Kadas L, Hedlund KO, Johansson J, Chapman MR, Jacobson SH, Romling U, Agerberth B, Brauner A. 2010. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli modulates immune responses and its curli fimbriae interact with the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001010. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Römling U. 2002. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 153:205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross P, Mayer R, Benziman M. 1991. Cellulose biosynthesis and function in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 55:35–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zogaj X, Nimtz M, Rohde M, Bokranz W, Romling U. 2001. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1452–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girgis HS, Liu Y, Ryu WS, Tavazoie S. 2007. A comprehensive genetic characterization of bacterial motility. PLoS Genet. 3:e154. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battaglioli EJ, Baisa G, Weeks AE, Schroll R, Hryckowian AJ, Welch RA. 2011. Isolation of generalized transducing bacteriophages for uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:6630–6635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, van der Velden AWM, Stojiljkovic I, Anic S, Heffron F. 1996. Identification of a new iron regulated locus of Salmonella typhi. Gene 183:207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redford P, Welch RA. 2006. Role of sigma E-regulated genes in Escherichia coli uropathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 74:4030–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma Q, Wood TK. 2009. OmpA influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation by repressing cellulose production through the CpxRA two-component system. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2735–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malone JG, Jaeger T, Spangler C, Ritz D, Spang A, Arrieumerlou C, Kaever V, Landmann R, Jenal U. 2010. YfiBNR mediates cyclic di-GMP dependent small colony variant formation and persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000804. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malone JG, Jaeger T, Manfredi P, Dötsch A, Blanka A, Bos R, Cornelis GR, Häussler S, Jenal U. 2012. The YfiBNR signal transduction mechanism reveals novel targets for the evolution of persistent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airways. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002760. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spurbeck RR, Tarrien RJ, Mobley HL. 2012. Enzymatically active and inactive phosphodiesterases and diguanylate cyclases are involved in regulation of motility or sessility in Escherichia coli CFT073. mBio 3:e00307–12. 10.1128/mBio.00307-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pesavento C, Becker G, Sommerfeldt N, Possling A, Tschowri N, Mehlis A, Hengge R. 2008. Inverse regulatory coordination of motility and curli-mediated adhesion in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 22:2434–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteiro C, Saxena I, Wang X, Kader A, Bokranz W, Simm R, Nobles D, Chromek M, Brauner A, Brown RM, Jr, Romling U. 2009. Characterization of cellulose production in Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and its biological consequences. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1105–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Méndez-Ortiz MM, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Membrillo-Hernandez J. 2006. Genome-wide transcriptional profile of Escherichia coli in response to high levels of the second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8090–8099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacey MM, Partridge JD, Green J. 2010. Escherichia coli K-12 YfgF is an anaerobic cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase with roles in cell surface remodelling and the oxidative stress response. Microbiology 156:2873–2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lane MC, Alteri CJ, Smith SN, Mobley HL. 2007. Expression of flagella is coincident with uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension to the upper urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:16669–16674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwan WR. 2008. Flagella allow uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension into murine kidneys. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298:441–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, Kaever V, Sourjik V, Roth V, Jenal U. 2010. Second messenger-mediated adjustment of bacterial swimming velocity. Cell 141:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. 2010. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “backstop brake” mechanism. Mol. Cell 38:128–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prigent-Combaret C, Brombacher E, Vidal O, Ambert A, Lejeune P, Landini P, Dorel C. 2001. Complex regulatory network controls initial adhesion and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli via regulation of the csgD gene. J. Bacteriol. 183:7213–7223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.