Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is an opportunistic pathogen that causes severe nosocomial infections. Strain ATCC 19606T utilizes the siderophore acinetobactin to acquire iron under iron-limiting conditions encountered in the host. Accordingly, the genome of this strain has three tonB genes encoding proteins for energy transduction functions needed for the active transport of nutrients, including iron, through the outer membrane. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that these tonB genes, which are present in the genomes of all sequenced A. baumannii strains, were acquired from different sources. Two of these genes occur as components of tonB-exbB-exbD operons and one as a monocistronic copy; all are actively transcribed in ATCC 19606T. The abilities of components of these TonB systems to complement the growth defect of Escherichia coli W3110 mutants KP1344 (tonB) and RA1051 (exbBD) under iron-chelated conditions further support the roles of these TonB systems in iron acquisition. Mutagenesis analysis of ATCC 19606T tonB1 (subscripted numbers represent different copies of genes or proteins) and tonB2 supports this hypothesis: their inactivation results in growth defects in iron-chelated media, without affecting acinetobactin biosynthesis or the production of the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA. In vivo assays using Galleria mellonella show that each TonB protein is involved in, but not essential for, bacterial virulence in this infection model. Furthermore, we observed that TonB2 plays a role in the ability of bacteria to bind to fibronectin and to adhere to A549 cells by uncharacterized mechanisms. Taken together, these results indicate that A. baumannii ATCC 19606T produces three independent TonB proteins, which appear to provide the energy-transducing functions needed for iron acquisition and cellular processes that play a role in the virulence of this pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii has emerged as an important human pathogen associated with a wide range of human infections, mainly in hospitalized and immunocompromised patients (1, 2). It has become alarmingly clear that A. baumannii clinical isolates have developed mechanisms of resistance to currently available antimicrobial chemotherapies, making treatment of serious infections caused by this pathogen a significant challenge in human medicine (2–5). Although much is known about antibiotic resistance and the epidemiology of infections caused by A. baumannii, the virulence properties and the pathobiology of this emerging pathogen are still poorly understood. Therefore, it is important to gain insight into the basic mechanisms this organism utilizes to persist in the host environment. Recent reports from our laboratory have demonstrated that the virulence of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T is dependent on the expression of adherence properties (6) and active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions (7, 8). However, further understanding of these properties is needed in order to elucidate their roles and exploit them as potential targets for new therapeutic approaches.

Iron is essential for the growth and survival of both the human host and bacteria. This crucial metal is required as a cofactor for critical enzymes that are involved in many basic cellular functions and metabolic pathways, such as electron transport, amino acid and nucleic acid biosynthesis, and protection from free radicals (9–11). In the human host, free iron is tightly controlled and is kept to low levels to prevent possible oxidative damage. Iron is sequestered in the host by high-affinity carrier proteins, such as ferritin, transferrin, and lactoferrin, or is bound to the protoporphyrin ring in hemoproteins. In response to iron limitation within the host, bacteria express high-affinity iron acquisition systems that directly bind these host proteins, or they synthesize and secrete ferric-binding compounds known as siderophores, which remove iron from these host iron pools (9, 11).

The ExbB-ExbD-TonB system provides Gram-negative bacteria the energy needed to transport host iron-carrier and iron-siderophore complexes into the periplasm once these complexes are bound to cognate TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors (12, 13). This system transduces the proton motive force (PMF) to facilitate the active transport of substrates through the outer membrane. Much work has been done toward understanding the mechanism and components of the TonB system in Escherichia coli K-12. ExbB and ExbD are inner membrane proteins, with homology to flagellar motor proteins MotA and MotB, that use the PMF to generate an energized form of TonB (14). TonB is a periplasmic protein that is anchored into the inner membrane by its hydrophobic N-terminal domain and is associated with both ExbB and ExbD. A rigid proline-rich spacer/periplasmic domain spans the periplasmic space, and a structurally conserved C-terminal domain (CTD) interacts with specific regions of TonB-dependent receptors located in the outer membrane (12, 15). The energized CTD of TonB mediates a conformational change of the TonB-dependent receptors by interacting directly with a conserved hydrophobic five-amino-acid region, termed the TonB box, located in the N-terminal plug domain of the receptor (16). This leads to the transport of the associated ligand into the periplasm and the de-energization of TonB by a poorly understood mechanism. Currently, three potentially viable models are proposed: the propeller, the pulling, and the periplasmic binding protein-assisted models; all of these have limitations preventing consensus for a single accepted mechanism (16).

All sequenced E. coli strains have several potential TonB-dependent receptors and only one set of exbB, exbD, and tonB genes; therefore, these receptors have to compete for the TonB complex (17, 18). Many bacteria overcome competition for TonB by harboring several distinct copies of genes coding for TonB and/or ExbB and ExbD. Pseudomonas syringae has nine different operons coding for TonB proteins (15). Vibrio cholerae has two different TonB complexes: TonB1-ExbB1-ExbD1 (subscripted numbers represent different copies of genes or proteins), linked to hemin utilization functions, and TonB2-ExbB2-ExbD2, associated with growth at high osmolarity (19, 20). Pseudomonas aeruginosa contains three tonB genes, one of which is important for motility and pilus assembly rather than for iron transport (21). It is becoming apparent that these multiple TonB systems have overlapping as well as distinct roles, in addition to being linked to virulence in pathogens such as P. aeruginosa (22), Vibrio anguillarum (23), and V. cholerae (20). In this regard, we wanted to explore the function of TonB in A. baumannii. Recent proteomic (24) and transcriptomic (25, 26) analyses of A. baumannii have predicted approximately 20 TonB-dependent receptors, some of which appear to be iron regulated. Specifically, the function of BauA, an iron-regulated TonB-dependent receptor that transports ferric acinetobactin (27, 28), indicates the presence of genes coding for an active TonB system within the genome of this pathogen. No reports on the features of TonB energy-transducing systems in A. baumannii are present in the literature, even though three highly conserved putative tonB genes are predicted in all available A. baumannii genome sequences: two occur as components of exbB-exbD-tonB operons and one as a monocistronic copy. This study highlights the importance of the TonB systems of A. baumannii in iron acquisition and adherence as well as their potential role in virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar (29) were used to maintain all bacterial strains. M9 minimal medium (30) was used for growth under chemically defined conditions. Iron-rich conditions were produced by adding FeCl3 (dissolved in 0.1 N HCl) or hemin (dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH), and iron-deficient conditions were produced by adding the synthetic iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (DIP), to LB or M9 medium. When applicable, unless otherwise noted, A. baumannii and E. coli strains were grown in the presence of the following antibiotics: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml), gentamicin (75 μg/ml), kanamycin (40 μg/ml), tetracycline (20 μg/ml), and trimethoprim (20 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. baumannii | ||

| 17978 | Clinical isolate | ATCC |

| 19606T | Clinical isolate; type strain | ATCC |

| 19606T s1 | basD::aph; 19606T acinetobactin production-deficient derivative; Kmr | 27 |

| 19606T 2234 | ompA::EZ::TN〈R6Kγori/KAN-2〉 derivative of 19606T; Kmr | 6 |

| 19606T 3069 | entA::aph; 19606T acinetobactin production-deficient derivative; Kmr | 8 |

| 19606T 3180 | tonB1::aph; derivative of 19606T; Kmr | This work |

| 19606T 3201 | tonB2::aacC1; derivative of 19606T; Gmr | This work |

| 19606T 3202 | tonB1::aph tonB2::aacC1; derivative of 19606T; Kmr Gmr | This work |

| 3180-994 | 3180 mutant harboring pMU994; Kmr Apr | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Used for DNA recombinant methods | Gibco-BRL |

| TOP10 | Used for DNA recombinant methods | Invitrogen |

| W3110 | Wild type; F− λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 rph-1 | 53 |

| KP1344 | W3110 tonB::bla; Ampr | 54 |

| RA1051 | W3110 ΔexbBD::aph ΔtolQR; Kmr | 55 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-Blunt II | PCR cloning vector; Kmr Zeor | Invitrogen |

| pBR322 | Cloning vector; Ampr Tetr | 56 |

| pBCSK+ | Cloning vector; Cmr | Stratagene |

| pUC4K | Source of aph cassette; Ampr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pPS856 | Source of aacC1 cassette; Gmr Ampr | 57 |

| pEX100T | sacB conjugative plasmid for gene replacement; Ampr | 58 |

| pRK2073 | Conjugation helper plasmid; Tmr | 59 |

| pWH1266 | A. baumannii shuttle vector; Ampr Tetr | 60 |

| pMU672 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2; Kmr | This work |

| pMU673 | pCR-Blunt II harboring W3110 exbB-exbD; Kmr | This work |

| pMU674 | pCR-Blunt II harboring W3110 tonB; Kmr | This work |

| pMU762 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB2; Kmr | This work |

| pMU823 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB3-exbB3-exbD3; Kmr | This work |

| pMU849 | pMU672 with exbD1.1::aacC1; Kmr Gmr | This work |

| pMU850 | pMU672 with exbD1.2::aacC1; Kmr Gmr | This work |

| pMU905 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB1; Kmr | This work |

| pMU912 | Insertion of pMU905 cloned into pBCSK+; Cmr | This work |

| pMU962 | Insertion of aph into pMU912; Cmr Kmr | This work |

| pMU966 | Insertion of pMU962 into pEX100T; Ampr Kmr | This work |

| pMU975 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB2; Kmr | This work |

| pMU976 | Insertion of pMU975 into pBCSK+; Cmr | This work |

| pMU978 | Insertion of aacC1 into pMU976; Cmr Gmr | This work |

| pMU982 | Insertion of pMU978 into pEX100T; Ampr Gmr | This work |

| pMU990 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB1; Kmr | This work |

| pMU994 | pWH1266 harboring tonB1; Ampr Tets | This work |

| pMU999 | pCR-Blunt II harboring tonB3; Kmr | This work |

| pMU1003 | Insertion of pMU999 into pBCSK+; Cmr | This work |

| pMU1008 | Insertion of aacC1 into pMU1003; Cmr Gmr | This work |

| pMU1009 | Insertion of pMU1008 into pEX100T; Ampr Gmr | This work |

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Tmr, trimethoprim resistance; Zeor, zeocin resistance.

The MIC of the iron chelator DIP was determined in LB or M9 minimal broth containing increasing concentrations of DIP. Cell growth was determined spectrophotometrically at 600 nm after overnight (12- to 14-h) incubation at 37°C in a shaking incubator set at 200 rpm.

General DNA procedures and sequence analysis.

Total DNA was isolated by using a miniscale method adapted from previously published research (31). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a commercial kit (Qiagen). DNA was digested with restriction enzymes as indicated by the supplier (New England BioLabs) and was size fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis (29). DNA nucleotide sequences obtained by standard BigDye-based automated DNA sequencing (Applied Biosystems) were examined and assembled using Sequencher (Gene Codes). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analyzed with DNAStar, BLAST, and analysis tools available through the ExPASy Molecular Biology Server (http://www.expasy.org). The multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of TonB CTD amino acid sequences provided by H. Vogel was assembled using ClustalX and MEGA5 (32). Phylogenetic analysis of the TonB MSA was visualized using MEGA5 as described previously (15). The secondary structure of each CTD was analyzed using the Jpred Web server (http://www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/www-jpred/index.html) with the Jalign algorithm.

Functional analysis of A. baumannii tonB-exbB-exbD systems.

The putative tonB-exbB-exbD systems were PCR amplified from A. baumannii ATCC 17978 genomic DNA with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and primer sets 3173 and 3174 (tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 [subscripted numbers used for exbD1.1 and exbD1.2 represent related but not identical copies of exbD]), 3314 and 3315 (tonB2), and 3402 and 3403 (tonB3-exbB3-exbD3) (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). These amplicons were cloned into pCR-Blunt, generating pMU672, pMU762, and pMU823, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Each plasmid was transformed into E. coli RA1051 (ΔexbBD::aph ΔtolQR) or E. coli KP1344 (tonB::bla) separately to test its role in iron acquisition, as described for the analysis of the AfeABCD iron transport system of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (33). To test whether exbD1.1 and exbD1.2 are functional, each exbD component was individually interrupted by inverse PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) with primers 3451 and 3452 (exbD1.1) or primers 3453 and 3454 (exbD1.2) and with pMU672 as the DNA template (Fig. 1A; see also Table S1). The pPS856 SmaI fragment harboring the aacC1 gene, which codes for gentamicin resistance, was inserted into each amplicon, generating exbD1.1::aacC1 (pMU849) and exbD1.2::aacC1 (pMU850), respectively (Fig. 1A). The resulting plasmids, pMU849 and pMU850, were transformed into E. coli RA1051 to test their roles in iron acquisition under increased iron chelation conditions. The exbB, exbD, and tonB genes were PCR amplified from E. coli W3110 genomic DNA with Pfu DNA polymerase and primers 3179 and 3180 (exbB-exbD) or 3177 and 3178 (tonB) (see Table S1). The amplicons were cloned into pCR-Blunt to generate the pMU673 and pMU674 plasmids (Table 1), which were transformed into E. coli RA1051 or E. coli KP1344, respectively. As a negative control, pBR322 was transformed into E. coli W3110, RA1051, and KP1344. The presence of the plasmid in each complementing strain was confirmed by restriction analysis of plasmid DNA isolated from cells cultured overnight with appropriate antibiotics.

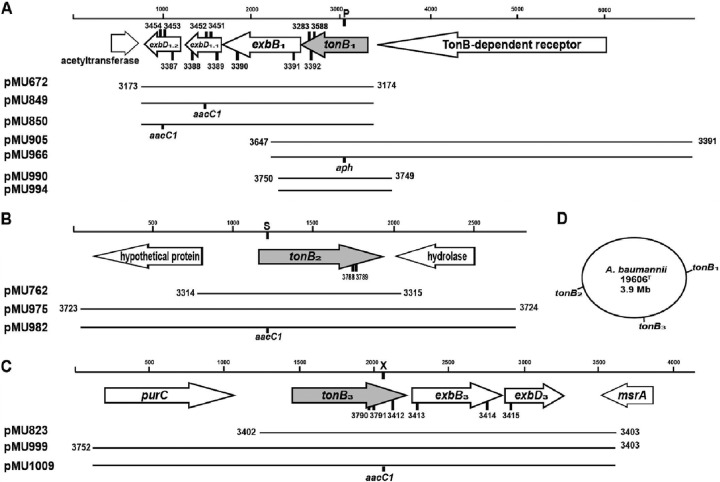

Fig 1.

Genetic maps of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T TonB systems. Shown is the genetic organization of the ATCC 19606T DNA regions harboring the TonB1 (A), TonB2 (B), and TonB3 (C) transducing system genes. The designations of the recombinant plasmids used in this work are given on the left. DNA positions (in base pairs) are given at the top of each panel. Horizontal arrows indicate the locations of predicted coding regions and their directions of transcription. Below the coding regions, the chromosomal regions that were PCR amplified and were used to generate the recombinant plasmids are shown, with the primers used for PCR amplification. Vertical bars indicate the insertion of the aph or aacC1 gene, coding for kanamycin or gentamicin resistance, respectively, at the PmlI (P), SphI (S), or XbaI (X) restriction site. Numbers above or below vertical bars indicate the locations of primers used for inverse PCR mutagenesis (3451 and 3452, 3453 and 3454), RT-PCR (3387 to 3392, 3412 to 3415), or qRT-PCR (3283 and 3588, 3788 and 3789, 3790 and 3791). (D) Locations of the three tonB loci in the ATCC 19606T chromosome.

Site-directed insertional mutagenesis of tonB genes.

A 4.4-kb fragment containing tonB1 and flanking DNA was PCR amplified from A. baumannii ATCC 19606T genomic DNA with Phusion DNA polymerase and primers 3391 and 3647 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplicon was cloned into pCR-Blunt to generate plasmid pMU905 (Fig. 1A). The amplicon was excised from pMU905 by EcoRI digestion and was subcloned into the EcoRI site of pBCSK+, generating pMU912. The pUC4K HincII fragment harboring the aph gene, which codes for kanamycin resistance, was inserted into the unique PmlI site of tonB1, generating pMU962. The tonB1::aph fragment was excised from pMU962 by BamHI and EcoRV digestion. The fragment was end-repaired and was cloned into the SmaI site of pEX100T to generate pMU966 (Fig. 1A).

A 2.8-kb fragment containing tonB2 and flanking DNA was PCR amplified from A. baumannii ATCC 19606T genomic DNA with Phusion DNA polymerase and primers 3723 and 3724 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplicon was cloned into pCR-Blunt to generate plasmid pMU975 (Fig. 1B). The amplicon was excised from pMU975 by XhoI digestion and was subcloned into the XhoI site of pBCSK+, generating pMU976. The pPS856 SphI fragment harboring the aacC1 gene, which codes for resistance to gentamicin, was inserted into the unique SphI site of tonB2, generating pMU978. The tonB2::aacC1 fragment was amplified from pMU978 by PCR using primers SK and T7 (Invitrogen) and Phusion DNA polymerase, and the amplicon was cloned into the SmaI site of pEX100T to generate pMU982 (Fig. 1B).

A 3.3-kb fragment containing tonB3 and flanking DNA was PCR amplified from A. baumannii ATCC 19606T genomic DNA with Phusion DNA polymerase and primers 3403 and 3752 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplicon was cloned into pCR-Blunt to generate plasmid pMU999 (Fig. 1C). The insert was excised from pMU999 by SacI and XhoI digestion and was subcloned into the cognate sites of pBCSK+, generating pMU1003. The pPS856 XbaI fragment harboring the aacC1 gene was inserted into the unique XbaI site of tonB3, generating pMU1008. The tonB3::aacC1 fragment was excised from pMU1008 by PvuII digestion and was cloned into the SmaI site of pEX100T to generate pMU1009 (Fig. 1C).

Triparental matings were conducted using A. baumannii ATCC 19606T as the recipient, E. coli DH5α cells containing pMU966 or pMU982 as the donor, and E. coli DH5α cells containing pRK2073 as the helper. For the generation of a double mutant, ATCC 19606T 3180 (tonB1::aph) and E. coli DH5α cells containing pMU982 were used as the recipient and donor strains, respectively, together with E. coli DH5α cells containing pRK2073 as the helper. Exconjugants were selected on LB agar plates containing either kanamycin or gentamicin and 15 μg/ml streptomycin, which was used as a counterselecting antibiotic. Cells from these plates were plated onto LB agar containing either kanamycin or gentamicin plus 5% sucrose and 750 μg/ml ampicillin to ensure the loss of pMU966 or pMU982, respectively. PCR analysis confirmed the proper allelic exchanges using primers 3283 and 3706 (tonB1) and primers 3314 and 3725 (tonB2) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Genetic complementation of mutants.

The A. baumannii ATCC 19606T tonB1 gene was PCR amplified from the parental strain genome with Phusion DNA polymerase and primers 3749 and 3750 (Fig. 1A), which include BamHI restriction sites (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The blunt-ended amplicon was ligated into pCR-Blunt and was transformed into E. coli TOP10. The cloned tonB1 gene was subcloned from pMU990 into the E. coli-A. baumannii shuttle vector pWH1266 as a BamHI restriction fragment to generate the cognate derivative pMU994 (Fig. 1A). The recombinant derivative was electroporated into the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T tonB1::aph derivative 3180 as described previously (34). Transformants that grew after overnight incubation at 37°C on LB agar containing 500 μg/ml ampicillin were tested for their abilities to grow under iron-limiting conditions. The presence of pMU994 in the complemented strain was confirmed by restriction analysis of plasmid DNA isolated from cells grown in LB broth containing 150 μg/ml ampicillin.

Iron utilization assays, detection of siderophore compounds, and detection of the BauA acinetobactin receptor protein.

Strains were tested for their abilities to use various iron sources by use of bioassays as described previously (27). Briefly, A. baumannii ATCC 19606T and each of the isogenic derivatives were inoculated into molten LB agar containing DIP in concentrations that would not allow bacterial growth (300 μM). Sterile paper filter discs were saturated with 10 μl of either FeCl3 (10 mM stock), hemin (10 mg/ml stock), a cell-free supernatant of an M9 overnight culture of ATCC 19606T containing acinetobactin, or sterile water, and the discs were then placed on the surfaces of inoculated agar plates. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were observed, and the cell growth around individual discs was recorded. Replicate experiments were performed three times, with a fresh biological sample each time.

The presence of iron-regulated extracellular phenolic compounds in M9 culture supernatants was detected by the Arnow colorimetric assay (35). Siderophore utilization bioassays were used to test the production of acinetobactin by using the ATCC 19606T acinetobactin-deficient derivative s1 as a reporter strain (27). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the diameters of growth halos were quantified. The production of the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA was examined by Western blotting with specific polyclonal antibodies as described previously (27).

Transcriptional analysis of tonB expression.

Total RNA was isolated from three independent combined 1-ml cultures of the parental ATCC 19606T strain or the tonB1::aph derivative 3180 grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 100 μM FeCl3 or 100 μM DIP by using hot phenol as described previously (36). Each RNA sample was further purified using the Qiagen RNeasy total-RNA isolation system, including the RNase-free DNase in-column treatment, before amplification by one-step reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (Qiagen). Primers 3387, 3388, 3389, 3390, 3391, 3392 (tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2), and 3412, 3413, 3414, and 3415 (tonB3-exbB3-exbD3) (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify the intergenic regions of each predicted polycistronic operon. The amplicons were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and were sequenced (29). PCR of total RNA without reverse transcriptase and with the appropriate set of primers was used to test RNA samples for DNA contamination, and PCR with no template served as a negative control.

Gene transcription under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions was measured by the Qiagen real-time one-step QuantiTect SYBR green quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) system according to the manufacturer's recommendations and as described previously (37). A 166-bp internal fragment of tonB1 was amplified with primers 3283 and 3588 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material); a 154-bp internal fragment of tonB2 was amplified with primers 3788 and 3789 (see Table S1); and a 133-bp internal fragment of tonB3 was amplified with primers 3790 and 3791 (see Table S1). Amplification of a 155-bp internal fragment of the constitutively expressed gene recA with primers 3545 and 3546 (see Table S1) served as an internal control, while a 124-bp internal fragment of bauA was amplified with primers 3273 and 3353 (Table S1) to serve as an iron-regulated positive control. The tonB1, tonB2, tonB3, and bauA transcript levels, calculated from a standard curve for each sample, were normalized to recA cDNA levels under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions. Samples containing no template or no reverse transcriptase served as negative controls. Experiments were performed twice in triplicate, using total RNA extracted from fresh biological samples each time.

Galleria mellonella killing assays.

The killing of Galleria mellonella larvae was determined as described previously (7). Bacterial cells previously grown for 24 h in LB broth were collected by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). The control groups included larvae that either were not injected or were injected with sterile PBS or with PBS supplemented with 100 μM FeCl3. The test groups included larvae infected with the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, or with the isogenic mutant 3069, 3180, 3201, or 3202 (Table 1), which were injected in the absence or presence of 100 μM FeCl3. Because mutant 3069 had an iron utilization deficiency due to inactivation of the entA acinetobactin-biosynthetic gene (8), it served as a negative control. After injection, the larvae were incubated at 37°C in darkness, and death was assessed at 24-h intervals over 6 days. Caterpillars were considered dead, and were removed, if they displayed no response to probing. The results of any trial were omitted if more than two deaths occurred in the control groups. The experiments were repeated three times using 10 larvae per experimental group (n = 30), and the resulting survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method (38). P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant for the log rank test of survival curves (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Fibronectin-binding assay.

Fibronectin-binding assays were performed as described previously (39), with some modifications. Briefly, a sterile 96-well culture plate was coated overnight at 4°C with 125 μl per well of fibronectin (10 μg/ml), bovine serum albumin (BSA) (20 μg/ml), or PBS (39). Bacterial cells were grown for 24 h in LB medium at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm, collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice, and resuspended with sterile PBS to a comparable optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The coated 96-well plate was seeded with 50 μl of approximately 105 bacteria per well (either the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, or the isogenic mutant 2234, 3180, 3201, or 3202 [Table 1]) and was incubated for 3 h at 24°C. Inocula were estimated spectrophotometrically by the OD600 and were further confirmed by plate counts. The wells were washed six times with sterile PBS to remove unbound bacteria. Adherent bacteria in each well were collected with 125 μl of sterile PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and were vortexed for 30 s, serially diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. Following incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the CFU were counted, and the number of bacteria that attached to wells coated with immobilized fibronectin or BSA, or to non-protein-coated wells, was calculated. The number of attached bacteria found under each condition tested was normalized to the number of ATCC 19606T cells attached to BSA-coated wells. Counts were compared using the Student t test; P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. Replicate experiments were performed three times in triplicate, using fresh biological samples each time.

A549 cell adherence assay.

A549 human alveolar epithelial cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 as described previously (6). Monolayers were infected in modified Hanks' balanced salt solution (mHBSS; the same as HBSS but without glucose) as described previously (37). Briefly, uncoated 24-well tissue culture plates were seeded with approximately 105 A549 cells and were incubated for 16 h. Bacteria were grown for 24 h in LB medium at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm, collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice, and resuspended with sterile mHBSS. For bacterial adherence, A549 monolayers were singly infected with 105 cells of the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, or the isogenic mutant 2234, 3180, 3201, or 3202 (Table 1) for 2 h in mHBSS. Inocula were estimated spectrophotometrically by the OD600 and were confirmed by plate counts. The infected monolayers were washed five times with sterile mHBSS, lysed with 500 μl of sterile distilled water (dH2O) containing 0.1% Triton X-100, serially diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. The numbers of CFU reflecting bacteria attached to A549 cells were recorded after overnight incubation at 37°C. The number of attached bacteria for each strain tested was normalized to the number of ATCC 19606T bacteria attached to A549 cells. Counts were compared using the Student t test; P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. Replicate experiments were performed three times in triplicate, using fresh biological samples each time.

RESULTS

Analysis of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T TonB systems.

In silico searches of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T genome (BaumannoScope Project Information; https://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/microscope/about/collabprojects.php?P_id=8) for genes encoding proteins with functions related to TonB (Pfam 03544) in their C-terminal domains (CTDs) identified three coding regions, two occurring as components of predicted tonB-exbB-exbD operons and one occurring as a monocistronic copy (Fig. 1A to C), located far apart from each other in the chromosome of this strain (Fig. 1D). The predicted tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 (ACIB1v1_190012 to -190015) operon is flanked by an upstream open reading frame (ORF) transcribed in the same direction, coding for a predicted TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor, while the downstream ORF, transcribed in the opposite direction, codes for a predicted acetyltransferase family protein (Fig. 1A). This predicted system contains four genes: tonB1 (ACIB1v1_190012), coding for a 26-kDa protein, exbB1 (ACIB1v1_190013), coding for a 31.1-kDa protein, and two exbD components, exbD1.1 (ACIB1v1_190014) and exbD1.2 (ACIB1v1_190015), coding for 15.2- and 17.3-kDa proteins, respectively. A second, monocistronic tonB locus, tonB2 (ACIB1v1_570149), predicted to code for a 28.6-kDa protein, is flanked by an upstream ORF transcribed in the opposite direction, coding for a hypothetical protein, and a downstream ORF transcribed in the opposite direction, coding for a metal-dependent hydrolase protein (Fig. 1B). A third TonB genetic system, tonB3-exbB3-exbD3 (ACIB1v1_360047 to -360045), is located between an upstream ORF transcribed in the same direction, coding for formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase (purC), and a downstream ORF transcribed in the opposite direction, coding for a peptide-methionine (S)-S-oxide reductase (msrA) (Fig. 1C). This predicted system contains three genes: tonB3 (ACIB1v1_360047), coding for a 27.4-kDa protein; exbB3 (ACIB1v1_360046), coding for a 24-kDa protein; and exbD3 (ACIB1v1_360045), coding for a 14.7-kDa protein. The in silico genomic searches also showed that there is synteny, along with significant amino acid sequence similarity, between the three TonB systems shown in Fig. 1 and those present in the chromosomes of A. baumannii strains AYE, ACICU, AB0057, ATCC 17978, and SDF and the environmental isolate Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. It is noteworthy that a fourth, hypothetical tonB gene has been identified as part of a gene cluster, potentially involved in iron acquisition, in A. baumannii strains ACICU, SDF, and AB0057 but not in the genome of strain ATCC 19606T (25).

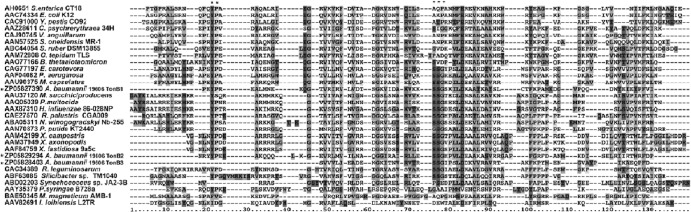

The CTD is the best-understood and best-conserved region of the three TonB domains (15). Accordingly, the predicted secondary structure of each ATCC 19606T TonB CTD, as determined by Jpred, shows that all three contain two α-helices and three β strands (data not shown), a pattern consistent with the CTD structures of other known TonB proteins (15). BLASTP analysis of the CTD from each ATCC 19606T TonB protein suggests a different lineage for each of them. The CTD of TonB1 is most closely related to the TonB from Leptothrix cholodnii (51% identity; 65% similarity); the CTD of TonB2 is most closely related to the TonB from Psychrobacter arcticus (59% identity; 74% similarity); and the CTD of TonB3 is most closely related to the TonB from Bordetella petrii (51% identity; 65% similarity). From previous bioinformatic and phylogenetic analyses of the CTDs of 263 different TonB sequences from 144 Gram-negative bacteria, nine different CTD clusters have been established (15). The multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the TonB CTD sequences reveals differences between the CTDs of the three ATCC 19606T TonB proteins (Fig. 2). A highly conserved YP motif found in the beginning of the TonB CTD, identified only in TonB1 and TonB2 from ATCC 19606T, has been shown to be in close contact with the TonB boxes of outer membrane protein receptors, as shown in the crystal structures of FhuA-TonB and BtuB-TonB complexes (15). A conserved SSG motif identified in numerous different TonB sequences and identified in each ATCC 19606T TonB is believed to play a role in outer membrane receptor recognition. Based on the neighbor-joining bootstrap tree (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) generated from the MSA shown in Fig. 2, the CTD of each ATCC 19606T TonB protein falls into a different phylogenetic cluster. These results suggest that each tonB gene found within the A. baumannii genome is a distinct genetic unit and that these genes could have been acquired from unrelated sources.

Fig 2.

Alignment of TonB C-terminal domains. Shown are representative sequences from each of the nine CTD clusters of Gram-negative TonB proteins, including the three TonB proteins from ATCC 19606T (asterisked). Regions of similarity are shaded based on their degrees of similarity. The highly conserved YP and SSG motifs are shaded and marked with asterisks above the alignment.

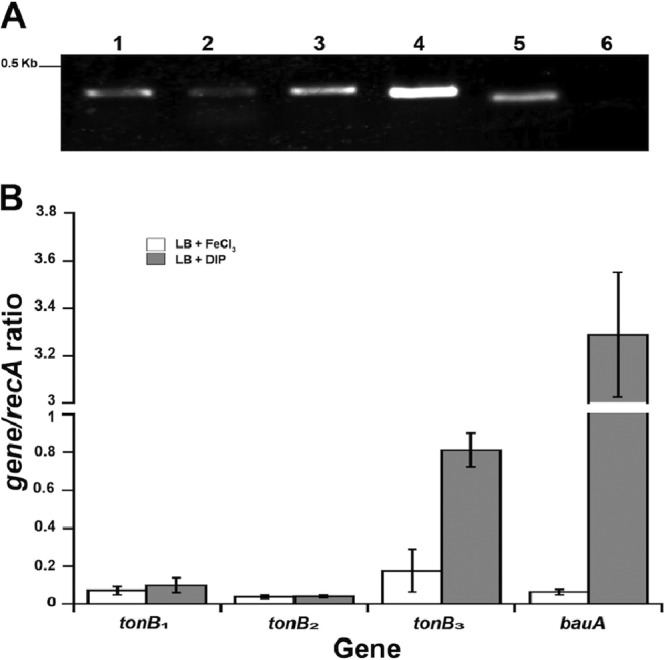

The short intergenic regions between the ORFs in tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 and tonB3-exbB3-exbD3 (Fig. 1) suggest that these genes are cotranscribed. The polycistronic transcription of these genes was confirmed by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) using total RNA from ATCC 19606T cells grown under iron-depleted conditions with primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) designed to amplify the intergenic regions between each predicted ORF shown in Fig. 1A and C. The resulting amplicons exhibited the predicted sizes and nucleotide sequences, indicating that each of these predicted tonB operons is expressed as a single mRNA unit under conditions of iron limitation (Fig. 3A). Taken together, these results show that A. baumannii ATCC 19606T codes for and expresses three different putative TonB energy-transducing complexes, which could provide the necessary energy to a variety of TonB-dependent receptors predicted to be on the surface of the A. baumannii cell. However, it is not known whether each protein complex works as an independent, complete unit or as hybrid complexes where different components of each protein system work in different combinations because of potential functional cross talk between functionally equivalent proteins. This possibility is particularly interesting when one considers TonB2, which could interact with either the ExbB1-ExbD1.1-ExbD1.2 or ExbB3-ExbD3 protein complex or with different protein permutations of these two protein complexes that allow the expression of energy transduction functions needed for iron acquisition.

Fig 3.

Transcriptional analyses of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T tonB, exbB, and exbD genes. (A) RT-PCR analysis using ATCC 19606T RNA isolated as described in Materials and Methods and the primer pairs indicated in Fig. 1, which were designed to amplify the intergenic regions between tonB1 and exbB1 (lane 1), exbB1 and exbD1.1 (lane 2), exbD1.1 and exbD1.2 (lane 3), tonB3 and exbB3 (lane 4), and exbB3 and exbD3 (lane 5). Lane 6, control with no reverse transcriptase. The 0.5-kb λ HindIII fragment is indicated on the left. (B) qRT-PCR of each ATCC 19606T tonB gene in response to available free iron. Transcription of recA and bauA, constitutively expressed and iron-regulated genes, respectively, was used for internal controls. RNA isolated from ATCC 19606T cells grown in LB broth with the addition of 100 μM FeCl3 (open bars) or 100 μM DIP (shaded bars) was used as the template with specific primers. The error bars represent the standard errors for two assays performed in triplicate.

Differential expression of each A. baumannii tonB gene.

Because of their roles in iron acquisition, the production of the TonB energy-transducing system components is subject to iron regulation; in E. coli, under iron-depleted conditions, the abundances of these proteins increase 2.5- to 3-fold because of transcriptional regulation (40). Accordingly, the role each distinct tonB gene could play in iron acquisition was investigated by examining their differential transcription in response to available free iron in the culture medium. qRT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from ATCC 19606T cells cultured in LB broth with the addition of 100 μM DIP showed a 4.5-fold increase in tonB3 transcription over that for RNA isolated from cells grown in LB broth with 100 μM FeCl3 (Fig. 3B). However, no significant changes in the transcription of tonB1 or tonB2 in response to the availability of free iron in the medium were observed (Fig. 3B). These results correspond to a recent global transcriptomic analysis of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 cells cultured under iron-rich and iron-chelated conditions, which found a 7.17-fold difference in tonB3 transcription in response to free iron (26). As a positive control, the qRT-PCR analysis of the same RNA samples showed a 50-fold increase in bauA expression under iron-chelated conditions over that under iron-rich conditions (Fig. 3B), a result that matches our previously reported findings (37). Together, these results suggest that tonB3 could play a major role in energy-transducing functions under iron chelation, while tonB1 and tonB2 could have only a minor role in this cellular process under these conditions.

Functional roles of A. baumannii TonB systems.

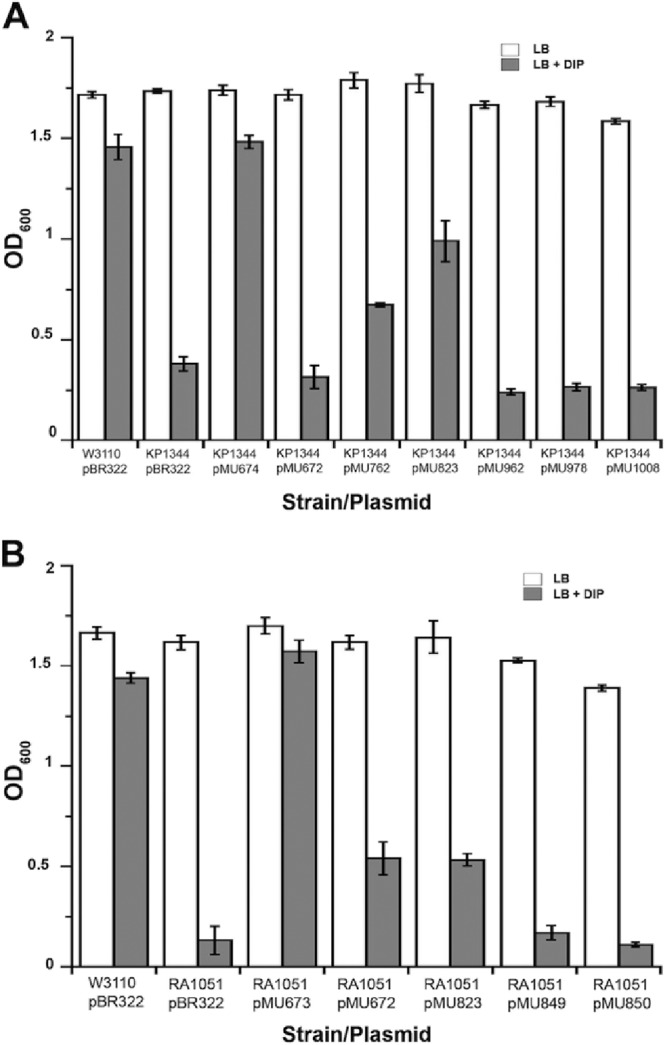

Although the E. coli W3110 TonB protein (BAA14784) and the three predicted ATCC 19606T TonB proteins are analogous in predicted function, the global alignment of their CTDs revealed relatively low levels of identity and similarity between W3110 and ATCC 19606T TonB1 (21% identity; 47% similarity), TonB2 (18% identity; 43% similarity), and TonB3 (22% identity; 50% similarity). Therefore, the functional roles of these predicted energy-transducing genes were tested by their capacities to restore the growth of E. coli W3110 derivative KP1344 (tonB::bla) under iron chelation, as determined by the transformation of KP1344 with each cloned ATCC 19606T tonB determinant. The genetic complementation of E. coli KP1344 with pMU762, which harbors tonB2, or pMU823, which harbors tonB3 together with the exbB3 and exbD3 coding regions (Fig. 1), restored bacterial growth under conditions of iron limitation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, transformation of E. coli KP1344 with pMU672, which harbors the tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 coding regions (Fig. 1), could not restore bacterial growth under conditions of iron chelation (Fig. 4A). The complementing activity of each ATCC 19606T tonB gene was further confirmed by the fact that transformation of E. coli KP1344 with copies of each tonB gene disrupted by site-directed insertion of a DNA cassette coding for antibiotic resistance (pMU962, pMU978, or pMU1008) abolished bacterial growth under conditions of iron limitation (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Growth of E. coli cells harboring plasmids coding for TonB energy transport features from A. baumannii and E. coli. (A) Growth of E. coli W3110 harboring pBR322 and of KP1344 (tonB::bla) harboring pBR322, pMU672, pMU674, pMU762, pMU823, pMU962, pMU978, or pMU1008 in LB broth (open bars) or LB broth plus 200 μM DIP (shaded bars). pMU674, a pCR-Blunt II derivative harboring the W3110 tonB gene (Table 1), was used as a positive control. (B) Growth of E. coli W3110 harboring pBR322 and of RA1051 (ΔexbBD::aph ΔtolQR) harboring pBR322, pMU673, pMU672, pMU823, pMU849, or pMU850 in LB broth (open bars) or LB broth plus 200 μM DIP (shaded bars). pMU673, a pCR-Blunt II derivative harboring the W3110 exbB and exbD genes (Table 1), was used as a positive control. OD600 readings were taken after overnight incubation (12 to 14 h) at 37°C in a shaking incubator. Error bars represent standard errors for three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Global alignment of the ATCC 19606T ExbB1-ExbD1.1-ExbD1.2 and ExbB3-ExbD3 proteins to the ExbB-ExbD proteins from E. coli W3110 also revealed low levels of identity and similarity between the latter and ATCC 19606T ExbB1 (24% identity; 39% similarity), ExbB3 (32% identity; 49% similarity), ExbD1.1 (33% identity; 49% similarity), ExbD1.2 (30% identity; 45% similarity), and ExbD3 (32% identity; 49% similarity). Thus, the functional roles of the ATCC 19606T exbB and exbD genes were tested by genetic complementation of the E. coli W3110 iron acquisition mutant RA1051 (ΔexbBD::aph ΔtolQR). Transformation of RA1051 with pMU672 or pMU823, harboring the ATCC 19606T tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 or tonB3-exbB3-exbD3 genes, respectively, restored growth under iron-limiting conditions, suggesting that these A. baumannii genes code for energy transduction functions needed for enterobactin-mediated iron acquisition (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the growth-enhancing effect of tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 in E. coli RA1051 was abolished when either the exbD1.1 (pMU849) or exbD1.2 (pMU850) gene was interrupted (Fig. 4B). Whether the insertional inactivation of exbD1.1 has a polar effect on the expression of exbD1.2 remains to be tested.

In each case, transformation of KP1344 or RA1051 with the cognate parental W3110 tonB (pMU674) or exbB-exbD (pMU673) copies restored growth to wild-type levels (Fig. 4A and B). Taken together, these observations suggest that the exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 and exbB3-exbD3 genes found in A. baumannii code for active energy transduction functions, whereas the tonB2 and tonB3 genes, but not the tonB1 gene, found in A. baumannii appear to function in E. coli to provide energy transduction functions needed for growth under iron chelation. As mentioned above, it is not known whether the complementing activity observed is due to the action of a particular ExbB-ExbD-TonB protein unit or to a hybrid unit in which proteins coded for by genes located in different tonB loci work together because of potential cross talk among functionally equivalent proteins.

Growth and iron acquisition phenotypes of isogenic tonB insertion derivatives.

The roles of the A. baumannii TonB systems in energy-transducing functions needed for iron acquisition were further investigated by generating isogenic derivatives of ATCC 19606T. ATCC 19606T isogenic derivatives with insertions in tonB1 (strain 3180), tonB2 (strain 3201), or both tonB1 and tonB2 (strain 3202) (Table 1) were successfully generated by site-directed mutagenesis as described in Materials and Methods. In contrast, the same conjugation methods, as well as different protocols, including liquid conjugations using various helper/donor/recipient ratios, failed to generate a proper tonB3 insertion mutant. Electroporation of ATCC 19606T cells, as described below for the construction of complemented strains, using either circular or linear plasmid pMU1008 DNA or DNA amplified by PCR with pMU1008 as the template, also failed to produce a proper tonB3::aacC1 insertion derivative.

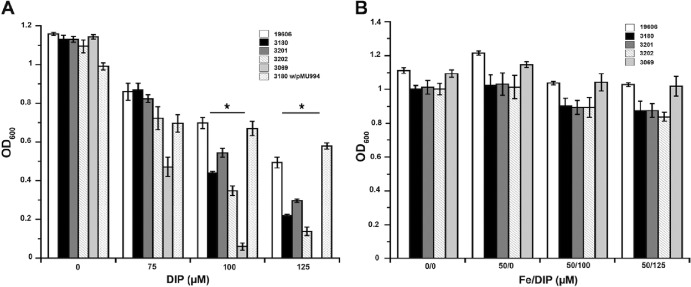

ATCC 19606T isogenic mutants 3180, 3201, and 3202 showed growth comparable to that of the parental strain in LB and M9 media without antibiotics or DIP (data not shown). In contrast, when cultured in M9 minimal medium with increasing concentrations of DIP, each isogenic tonB insertion derivative showed a significant deficiency in growth (P ≤ 0.05) compared to that of the parental strain, and the tonB1 tonB2 double mutant was more deficient than the single insertion derivatives (Fig. 5A). However, this growth deficiency was not as drastic as that of strain 3069 (entA::aph), which contains an insertion in entA that abolishes acinetobactin biosynthesis. A similar growth phenotype was observed in LB medium; however, much higher levels of DIP were required to produce the same effect, as expected considering the defined nature of the M9 minimal medium (data not shown). The growth-deficient phenotype of each derivative in M9 medium containing 100 μM or 125 μM DIP can be corrected to wild-type levels by the addition of 50 μM FeCl3 (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that TonB1 and TonB2 are required for A. baumannii to grow to levels similar to those of the wild-type strain under iron-limiting conditions. Whether TonB3 has functions essential for bacterial viability that are independent of the iron concentration in the medium, a possibility suggested by the failure to produce an insertion mutant, needs to be examined in more detail.

Fig 5.

Effect of tonB inactivation on bacterial growth under iron limitation. (A) Growth of the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, the 3180, 3201, 3202, and 3069 isogenic derivatives, and 3180 transformed with pMU994, carrying the parental tonB1 copy, in M9 minimal medium containing increased concentrations of DIP. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) from results for ATCC 19606T. (B) Growth of strains ATCC 19606T, 3180, 3201, 3202, and 3069 in unsupplemented M9 minimal medium (0/0) or in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 50 μM FeCl3 alone (50/0) or with 50 μM FeCl3 plus 100 μM (50/100) or 125 μM (50/125) DIP. OD600 readings were taken after overnight incubation (12 to 14 h) at 37°C in a shaking incubator. Error bars represent standard errors from three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

The role of the tonB1 gene in the phenotype of the 3180 (tonB1::aph) mutant was further confirmed by the fact that electroporation of pMU994, a derivative of the pWH1266 shuttle vector harboring the tonB1 parental copy, was enough to restore growth in chelated M9 minimal medium (Fig. 5A). To further ensure that the phenotype of 3180 (tonB1::aph) was not due to a polar effect on the transcription of downstream exbB1, exbD1.1, and exbD1.2 coding regions, RT-PCR was performed. The predicted amplicons were obtained when RNA isolated from 3180 cells and primers flanking the cognate intergenic regions were used (data not shown). Although this result indicates that an insertion in tonB1 did not affect the transcription of downstream genes of this polycistronic operon, the data do not exclude the possibility of polar effects at the translational level.

Arnow's colorimetric tests and siderophore utilization bioassays using the ATCC 19606T s1 derivative (which does not produce acinetobactin but expresses all functions needed for its internalization) as an indicator strain showed that each of the isogenic tonB insertion derivatives (3180, 3201, and 3202) produces catechol and acinetobactin at levels similar to those detected with the parental strain, ATCC 19606T (data not shown). Immunoblotting of whole-cell lysate proteins obtained from the parental strain and each isogenic tonB insertion derivative (3180, 3201, and 3202) with anti-BauA polyclonal antibodies showed similar levels of production of the outer membrane acinetobactin receptor BauA in all strains only when they were grown under iron-chelated conditions (data not shown). Iron utilization bioassays showed that each isogenic tonB insertion mutant grew around filter discs saturated with FeCl3, hemin, or an ATCC 19606T M9 cell-free culture supernatant, which contains acinetobactin, deposited on LB agar supplemented with 300 μM DIP and seeded with cells of each strain (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). However, the growth halos of the three ATCC 19606T tonB insertion mutants around discs containing acinetobactin or hemin were smaller than those of the parental strain (see Table S2). Taken together, these results indicate that all ATCC 19606T TonB isogenic derivatives produce acinetobactin, as well as critical acinetobactin transport proteins, such as the BauA outer membrane receptor. However, their capacities to transport iron-containing compounds, such as ferric acinetobactin and hemin, are lower than that of the parental strain because of deficiencies in energy-transducing processes needed for the transport of these compounds across the outer membrane.

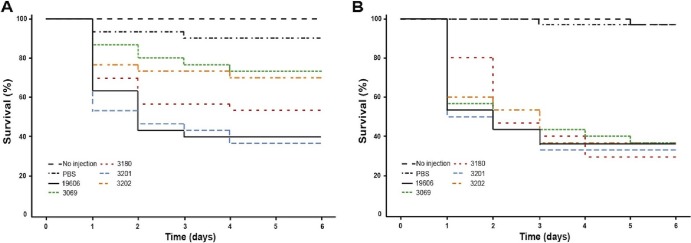

Role of TonB in virulence.

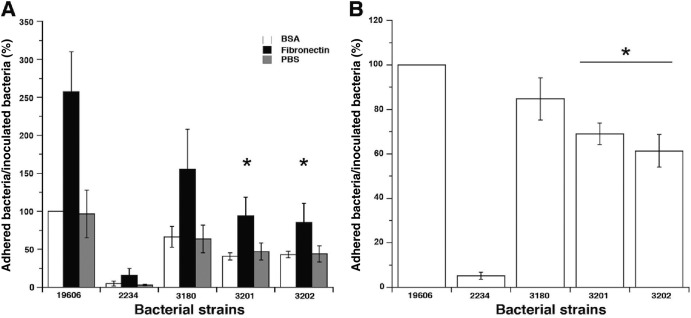

The role of each TonB protein in the virulence of ATCC 19606T was examined using larvae of the greater wax moth, G. mellonella, as an experimental infection model. This model has been used successfully to determine the virulence role of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system and to test the efficacy of antibiotics in the treatment of A. baumannii infections (7, 41). The G. mellonella model showed that 60% and 63% of the caterpillars injected with the parental strain or the 3201 (tonB2::aacC1) derivative, respectively, were killed 6 days after injection (Fig. 6A). Injection with the 3180 (tonB1::aph) derivative resulted in killing of 47% of the injected caterpillars 6 days after injection; however, this level of virulence is not significantly different (P = 0.3182) from that of the parental strain (Fig. 6A). Injection with the 3202 (tonB1::aph tonB2::aacC1) derivative resulted in 30% killing of the injected caterpillars over the 6 days (Fig. 6A). The difference in killing between strain 3202 and the parental strain is significant (P = 0.0243). As shown previously, strain 3069 (entA::aph), serving as our negative control because of its iron uptake deficiency due to the inactivation of the entA acinetobactin-biosynthetic gene (8), resulted in the killing of 27% of the injected caterpillars over 6 days. The addition of 100 μM FeCl3 to the inocula resulted in comparable virulence, with increased killing rates (compare Fig. 6A and B), for all strains tested, results significantly different from those for the PBS-plus-FeCl3 control (P = 0.01). These observations suggest that no TonB protein individually is essential for bacterial virulence; only when both TonB1 and TonB2 are disrupted is the level of virulence significantly reduced from that of the wild-type strain, ATCC 19606T.

Fig 6.

Role of TonB in virulence. G. mellonella caterpillars (n = 30) were injected with 1 × 105 bacteria of the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, or the tonB1 (3180), tonB2 (3201), tonB1 tonB2 (3202), or entA (3069) insertion derivative in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 100 μM FeCl3. As negative controls, caterpillars were injected with comparable volumes of PBS alone or PBS plus 100 μM FeCl3. Caterpillar death was determined daily for 6 days after incubation at 37°C in darkness.

Attachment to immobilized fibronectin.

Recent reports (39, 42) have shown that the adherence of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to host cells is mediated by binding to fibronectin, a host extracellular matrix protein that could have a role in bacterial adhesion and internalization. One of the A. baumannii outer membrane fibronectin binding proteins identified in ATCC 19606T is a 78-kDa TonB-dependent copper receptor protein (ACIB1v1_730004) (39). Therefore, the contribution of the TonB systems to adherence to immobilized fibronectin was tested using the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, and the isogenic tonB insertion mutants. The cells of all A. baumannii strains tested adhered more to polystyrene wells coated with fibronectin than to BSA-coated or uncoated wells (Fig. 7A). The parental strain, ATCC 19606T, showed 2.5-fold-greater attachment to fibronectin-coated wells than to BSA-coated wells, a finding in agreement with results published in a recent report (39). The level of attachment of the 3180 (tonB1::aph) derivative, while reduced, was not significantly different from that of the parental strain (P = 0.195) (Fig. 7A). In contrast, significant reductions in the proportions of cells adherent to immobilized fibronectin from those for the parental strain were observed with both the 3201 (tonB2::aacC1) (P = 0.021) and 3202 (tonB1::aph tonB2::aacC1) (P = 0.017) derivatives. Strain 2234, an isogenic ATCC 19606T derivative with impaired production of the OmpA protein, which binds fibronectin (39), served as a control; its adherence to immobilized fibronectin was significantly reduced (P = 0.01), to levels comparable to those observed with BSA-coated or non-protein-coated wells, but was not completely abolished (Fig. 7A), findings that matched previously reported observations (6). No tonB insertion derivative strains showed a significant difference from the parental strain in attachment to non-protein-coated wells (Fig. 7A). These results indicate that TonB2 has a greater role than TonB1 in the ability of ATCC 19606T cells to bind immobilized fibronectin, without affecting their capacity to adhere to uncoated plastic surfaces.

Fig 7.

Binding of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells to immobilized fibronectin and A549 epithelial cells. (A) Counts of adherent bacteria in wells coated with BSA (open bars) or fibronectin (filled bars), or in uncoated wells (shaded bars), after a 3-h incubation with 1 × 105 bacteria of the parental strain (19606) or an ompA (2234), tonB1 (3180), tonB2 (3201), or tonB1 tonB2 (3202) insertion derivative grown overnight in LB broth. (B) Counts of adherent bacteria after a 2-h infection of 1 × 105 A549 cells with 1 × 105 bacteria of the strains used for panel A. For both fibronectin and A549 cell binding, attached cells were recovered with 0.1% Triton X-100, serially diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. Data are presented as the ratio of CFU counts recovered after infection to the CFU counts of the cognate infecting inoculum. The fibronectin and A549 ratios were normalized by assigning the value of 100% to the binding of ATCC 19606T bacteria to immobilized BSA and A549 epithelial cells, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) from ATCC 19606T. Error bars represent standard errors for three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Attachment to A549 cell monolayers.

To further assess the role of TonB in attachment to biotic surfaces, the interactions of the parental strain, ATCC 19606T, and the tonB insertion derivatives with A549 human alveolar epithelial cells were examined. Infection of A549 cell monolayers with ATCC 19606T for 2 h resulted in the recovery of 10% of inoculated bacteria adherent to the A549 monolayers (Fig. 7B). Infection of A549 monolayers with the 3180 (tonB1::aph) derivative did not result in a significant difference from the parental strain (P = 0.20) in the proportion of attached bacteria (Fig. 7B). However, infection of the A549 monolayers with the 3201 (tonB2::aacC1) or 3202 (tonB1::aph tonB2::aacC1) derivative resulted in a significant reduction (P ≤ 0.01), of 32% or 39%, respectively, in the proportion of attached bacteria from that for the parental strain (Fig. 7B). As reported previously (6), strain 2234, an ATCC 19606T ompA insertion derivative, showed a significant reduction (P ≤ 0.01), but not a complete loss, of bacterial attachment to the A549 monolayers (Fig. 7B). Thus, these observations suggest that TonB2 plays a more relevant role than TonB1 in the interaction of ATCC 19606T cells with A549 human respiratory epithelial cells, a process that could involve a TonB-dependent outer membrane protein.

DISCUSSION

In almost all sequenced Gram-negative bacteria, one or more TonB systems have been identified. Studies of these TonB systems have focused on iron transport and virulence functions, along with similarities to the E. coli TonB system. While iron is a primary ligand for TonB-dependent transporters, other molecules, such as vitamin B12, nickel, and carbohydrates, are also transported in a TonB-dependent manner (18). With the increase in the number of available sequenced organisms revealing multiple tonB genes, the notion of how TonB works cannot be based solely on work on the single TonB system present and expressed in E. coli. Currently, nothing is known about the functions of the TonB systems in A. baumannii, except for hypothetical genomic annotation (25). The genome of the A. baumannii type strain, ATCC 19606, harbors three tonB gene clusters, which are present in all sequenced A. baumannii genomes and are predicted to be involved in the transduction of energy needed for the transport of nutrients across the outer membrane. Our current observations begin to elucidate the role of each distinct A. baumannii ATCC 19606T TonB system with regard to nutrient acquisition, surface attachment, and virulence.

A functional role of these A. baumannii energy-transducing components is supported by their capacity to correct the iron utilization deficiency of E. coli KP1344 (tonB::bla) and RA1051 (ΔexbBD::aph ΔtolQR) mutants. Both the exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 and exbB3-exbD3 components are sufficient to restore E. coli RA1051 growth under iron chelation, while only tonB2 and tonB3 are able to correct the growth defect of E. coli KP1344 under this condition, although neither ATCC 19606T tonB gene works as well as the parental E. coli copies. This observation could be due to loss of proper gene regulation because of tonB2 and tonB3 expression from a high-copy-number plasmid, resulting in an altered stoichiometry of the protein components of this system. However, it is more likely that low amino acid sequence homology, along with divergences within the CTD among E. coli and A. baumannii TonB proteins, should be considered a cause of the reduced growth of the complemented E. coli strains shown in Fig. 4.

The presence within the A. baumannii tonB1-exbB1-exbD1.1-exbD1.2 cluster of two contiguous copies of exbD genes, both of which are needed to restore the growth of E. coli RA1051 under iron limitation, is of interest. To our knowledge, only two reports have previously described two ExbD proteins encoded within the same TonB cluster in other Gram-negative microorganisms (43, 44). In both cases, it was found that only one of the two ExbD proteins was involved in iron uptake functions, an observation that contrasts with our results showing that both exbD products are required for iron acquisition. With the additional ExbD component, this particular TonB system could have an enhanced energy-transducing ability due to particular interactions among the components of this system, as well as with TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors, a possibility that remains to be explored.

The fact that each A. baumannii ATCC 19606T isogenic tonB insertion derivative produces a fully functional acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system, which is the only completely functional high-affinity system expressed by this clinical isolate when cultured under laboratory conditions (8), indicates that the growth defect of these mutants is due to their inability to transport sequestered iron effectively. This possibility is further supported by the fact that the growth-deficient phenotype of each derivative under increased iron chelation can be corrected by the presence of free inorganic iron in the medium. However, our data indicate that although the ATCC 19606T tonB1 and tonB2 genes play a role in siderophore-mediated iron acquisition, the tonB3 copy seems critical for energy-dependent outer membrane transport processes, including the acquisition of essential iron. This conclusion is supported by the fact that tonB3 transcription is iron regulated, which is most likely associated with the presence of a predicted Fur box upstream of the tonB3 promoter region (26), and our inability to generate a viable insertion derivative. Interestingly, the predicted amino acid sequence of the TonB3 protein does not include the highly conserved YP domain within the CTD. This observation may reflect potentially unique functional properties of this ortholog, a possibility that remains to be tested experimentally.

Iron acquisition and utilization play a central role when bacteria are cultured under laboratory conditions, as well as in host-pathogen interactions involved in the pathogenesis of infections, which can be studied using different experimental models. The G. mellonella model has been used previously to study different bacterial pathogens, since the larvae mount an innate immune response similar to that of the human host, which includes the function of phagocytic cells, the production of humoral and cellular pattern recognition receptors, and the production of antimicrobial peptides (45). Additionally, the iron-binding proteins present within the hemolymph of the larvae (46) and the observation that G. mellonella hemocytes associate with A. baumannii cells (41) indicate that there are iron reservoirs within the larvae that pathogens can use during colonization and infection under the iron-limiting conditions imposed by this invertebrate host. In line with these observations, A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells successfully infect G. mellonella larvae only if they express an active acinetobactin iron uptake mechanism (7, 8) as well as proper intracellular iron utilization functions (37). Accordingly, the virulence of ATCC 19606T depends on the expression of TonB-dependent energy transduction functions, as shown by the significantly lower virulence of the tonB1 tonB2 double mutant 3202 than of the parental strain. In contrast, inactivation of the tonB1 or tonB2 gene has only a modest effect on virulence. These results, together with the potentially essential role of tonB3 and its iron-regulated expression, indicate that, though redundant, the three TonB-mediated energy transduction systems could play different roles in the physiology and virulence of A. baumannii.

Host colonization and infection entail the interaction of the pathogen with host cells and products, such as the components of the extracellular matrix. Thus, the greater adherence of A. baumannii to plastic covered with immobilized fibronectin than to uncoated or BSA-coated plastic surfaces was not surprising, considering the recent report by Smani et al. (39). These investigators made a similar observation and identified OmpA, a 34-kDa outer membrane protein, and a TonB-dependent copper receptor as potential A. baumannii fibronectin binding proteins. Our data collected with the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T ompA-deficient mutant corroborate the results collected using neutralizing anti-OmpA antibodies (39). Our data also lend support to the involvement of a TonB-dependent receptor protein in adherence, since inactivation of the ATCC 19606T tonB genes, particularly tonB2, reduces bacterial adhesion to immobilized fibronectin. Additionally, there is a direct correlation between the binding of bacteria to immobilized fibronectin and their association with A549 human alveolar epithelial cells, which are normally covered by a mucin layer, further supporting the hypothesis that A. baumannii utilizes this glycoprotein to interact with host target cells and tissues. It is worth noting that the adherence responses shown in Fig. 7B are most likely not due to the expression of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions or an iron-deficient environment, since we showed that ATCC 19606T derivatives impaired in the expression of acinetobactin biosynthesis or transport functions displayed an adherence phenotype similar to that of the parental strain (7). It should also be noted that the data shown in Fig. 7A and B were obtained with bacteria cultured in LB broth, which contains enough free iron to repress the production of ATCC 19606T iron-regulated proteins (24), and the solutions and materials used in these assays were not treated to remove free iron. Taking all these points into account, our data indicate that the interaction of A. baumannii with fibronectin, either immobilized on an abiotic surface or present on the surfaces of epithelial cells, is due in part to uncharacterized TonB-dependent processes rather than to the expression of iron acquisition functions or the effect of an iron-restricted extracellular environment. Considering that A. baumannii often causes respiratory and wound infections, binding to fibronectin is a reasonable outcome, since the ensuing inflammation response causes an influx of this extracellular matrix component to the infection site as part of the mechanisms the host uses to facilitate wound healing (47). The binding of fibronectin to abiotic medical implants and devices, such as prostheses and catheters, also explains the persistence of A. baumannii and other pathogens, including Pasteurella multocida, Salmonella enterica, and Streptococcus pyogenes (48–50), a problem that has negative effects on the treatment of bacterial infections (51).

Our data clearly indicate that TonB-dependent processes play a critical role in the interaction of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells with fibronectin-coated abiotic or biotic surfaces. This conclusion is in agreement with the observation that fibronectin binds TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors present in Bacteroides fragilis, P. multocida, and A. baumannii (39, 48, 52). However, the molecular factors and processes involved in these interactions are not clear at the moment. The conclusion that fibronectin binds TonB (39, 52) is not in agreement with the known subcellular location and topology of TonB. This is a cytoplasmic membrane-anchored protein that spans the periplasmic space, interacts with the N-terminal domain of TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors, and most likely is not exposed to the extracellular environment. On the other hand, the experimental evidence showing the binding of fibronectin to TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors and the negative effect of TonB inactivation may indicate that fibronectin-surface protein interactions may involve energy-dependent receptor conformational changes similar to those described for nutrient transport. Alternatively, one of the ATCC 19606T TonB proteins, such as TonB2, could play a role in the export of fibronectin binding proteins to the bacterial outer membrane, a possibility supported by the observation that the product of the P. aeruginosa tonB3 gene is required for type IV pilus assembly and twitching motility (21). Therefore, on the basis of these observations, it seems reasonable to propose that the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T TonB2 ortholog plays a role in attachment and colonization, as well as in iron acquisition. Clearly, all these are interesting possibilities that remain to be confirmed experimentally.

In conclusion, the results of this investigation highlight the presence of three complementary but distinct TonB systems in A. baumannii. The expression of multiple TonB-dependent energy transduction systems may allow this pathogen to scavenge essential nutrients, such as iron, more efficiently in different environments. Additionally, they may provide a biological advantage, allowing bacteria to respond to environmental cues more effectively over the course of an infection and ultimately aiding in the survival and propagation of this pathogen, which causes severe human infections worldwide.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from Public Health (AI070174) and NSF (0420479) grants and by Miami University research funds.

We are thankful to A. Kiss and the Miami University Center of Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics for support and assistance with automated DNA sequencing and with nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic analyses. We are grateful to R. Larsen, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio, for providing the E. coli KP1344, RA1051, and W3110 strains and to H. Vogel and B. Chu, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, for providing the MSA TonB sequence database.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 July 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00540-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mortensen BL, Skaar EP. 2012. Host-microbe interactions that shape the pathogenesis of Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Cell. Microbiol. 14:1336–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calhoun JH, Murray CK, Manring MM. 2008. Multidrug-resistant organisms in military wounds from Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466:1356–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerqueira GM, Peleg AY. 2011. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. IUBMB Life 63:1055–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez F, Endimiani A, Bonomo RA. 2008. Why are we afraid of Acinetobacter baumannii? Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6:269–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaddy JA, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2009. The Acinetobacter baumannii 19606 OmpA protein plays a role in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and the interaction of this pathogen with eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 77:3150–3160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaddy JA, Arivett BA, McConnell MJ, Lopez-Rojas R, Pachon J, Actis LA. 2012. Role of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions in the interaction of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T with human lung epithelial cells, Galleria mellonella caterpillars, and mice. Infect. Immun. 80:1015–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penwell WF, Arivett BA, Actis LA. 2012. The Acinetobacter baumannii entA gene located outside the acinetobactin cluster is critical for siderophore production, iron acquisition and virulence. PLoS One 7:e36493. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM. 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. 2004. Iron and microbial infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:946–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. 2004. Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:611–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postle K, Kadner RJ. 2003. Touch and go: tying TonB to transport. Mol. Microbiol. 49:869–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postle K. 2007. TonB system, in vivo assays and characterization. Methods Enzymol. 422:245–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cascales E, Lloubes R, Sturgis JN. 2001. The TolQ-TolR proteins energize TolA and share homologies with the flagellar motor proteins MotA-MotB. Mol. Microbiol. 42:795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu BC, Peacock RS, Vogel HJ. 2007. Bioinformatic analysis of the TonB protein family. Biometals 20:467–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. 2011. TonB or not TonB: is that the question? Biochem. Cell Biol. 89:87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadner RJ, Heller KJ. 1995. Mutual inhibition of cobalamin and siderophore uptake systems suggest their competition for TonB function. J. Bacteriol. 177:4829–4835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schauer K, Rodionov DA, de Reuse H. 2008. New substrates for TonB-dependent transport: do we only see the ‘tip of the iceberg'? Trends Biochem. Sci. 33:330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Occhino DA, Wyckoff EE, Henderson DP, Wrona TJ, Payne SM. 1998. Vibrio cholerae iron transport: haem transport genes are linked to one of two sets of tonB, exbB, exbD genes. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1493–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seliger SS, Mey AR, Valle AM, Payne SM. 2001. The two TonB systems of Vibrio cholerae: redundant and specific functions. Mol. Microbiol. 39:801–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang B, Ru K, Yuan Z, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. 2004. tonB3 is required for normal twitching motility and extracellular assembly of type IV pili. J. Bacteriol. 186:4387–4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takase H, Nitanai H, Hoshino K, Otani T. 2000. Requirement of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa tonB gene for high-affinity iron acquisition and infection. Infect. Immun. 68:4498–4504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stork M, Di Lorenzo M, Mourino S, Osorio CR, Lemos ML, Crosa JH. 2004. Two tonB systems function in iron transport in Vibrio anguillarum, but only one is essential for virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:7326–7329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nwugo CC, Gaddy JA, Zimbler DL, Actis LA. 2011. Deciphering the iron response in Acinetobacter baumannii: a proteomics approach. J. Proteomics 74:44–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antunes LC, Imperi F, Towner KJ, Visca P. 2011. Genome-assisted identification of putative iron-utilization genes in Acinetobacter baumannii and their distribution among a genotypically diverse collection of clinical isolates. Res. Microbiol. 162:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eijkelkamp BA, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT, Brown MH. 2011. Investigation of the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii under iron limiting conditions. BMC Genomics 12:126. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Connerly PL, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH, Actis LA. 2004. The siderophore-mediated iron acquisition systems of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Vibrio anguillarum 775 are structurally and functionally related. Microbiology 150:3657–3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihara K, Tanabe T, Yamakawa Y, Funahashi T, Nakao H, Narimatsu S, Yamamoto S. 2004. Identification and transcriptional organization of a gene cluster involved in biosynthesis and transport of acinetobactin, a siderophore produced by Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T. Microbiology 150:2587–2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barcak JG, Chandler MS, Redfield RJ, Tomb JF. 1991. Genetic systems in Haemophilus influenzae. Methods Enzymol. 204:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhodes ER, Menke S, Shoemaker C, Tomaras AP, McGillivary G, Actis LA. 2007. Iron acquisition in the dental pathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: what does it use as a source and how does it get this essential metal? Biometals 20:365–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2002. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii insertion derivatives generated with a transposome system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6353–6360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnow L. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-tyrosine mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531–537 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mussi MA, Gaddy JA, Cabruja M, Arivett BA, Viale AM, Rasia R, Actis LA. 2010. The opportunistic human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii senses and responds to light. J. Bacteriol. 192:6336–6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimbler DL, Park TM, Arivett BA, Penwell WF, Greer SM, Woodruff TM, Tierney DL, Actis LA. 2012. Stress response and virulence functions of the Acinetobacter baumannii NfuA Fe-S scaffold protein. J. Bacteriol. 194:2884–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan EL, Meier P. 1958. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Statist. Assn. 53:457–481 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smani Y, McConnell MJ, Pachon J. 2012. Role of fibronectin in the adhesion of Acinetobacter baumannii to host cells. PLoS One 7:e33073. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgs PI, Larsen RA, Postle K. 2002. Quantification of known components of the Escherichia coli TonB energy transduction system: TonB, ExbB, ExbD and FepA. Mol. Microbiol. 44:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peleg AY, Jara S, Monga D, Elipoulos GM, Moellering RC, Mylonakis E. 2009. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis and therapeutics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2605–2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dallo SF, Zhang B, Denno J, Hong S, Tsai A, Haskins W, Ye JY, Weitao T. 2012. Association of Acinetobacter baumannii EF-Tu with cell surface, outer membrane vesicles, and fibronectin. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:128705. 10.1100/2012/128705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez B, Alvarez J, Menendez A, Guijarro JA. 2008. A mutant in one of two exbD loci of a TonB system in Flavobacterium psychrophilum shows attenuated virulence and confers protection against cold water disease. Microbiology 154:1144–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiggerich HG, Puhler A. 2000. The exbD2 gene as well as the iron-uptake genes tonB, exbB and exbD1 of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris are essential for the induction of a hypersensitive response on pepper (Capsicum annuum). Microbiology 146:1053–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nichol H, Law JH, Winzerling JJ. 2002. Iron metabolism in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47:535–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grinnell F. 1984. Fibronectin and wound healing. J. Cell. Biochem. 26:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dabo SM, Confer AW, Hartson SD. 2005. Adherence of Pasteurella multocida to fibronectin. Vet. Microbiol. 110:265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dorsey CW, Laarakker MC, Humphries AD, Weening EH, Baumler AJ. 2005. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium MisL is an intestinal colonization factor that binds fibronectin. Mol. Microbiol. 57:196–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]