Abstract

The nephrotoxicity of polymyxins is a major dose-limiting factor for treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. The mechanism(s) of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity is not clear. This study aimed to investigate polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in kidney proximal tubular cells. Polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in NRK-52E cells was examined by caspase activation, DNA breakage, and translocation of membrane phosphatidylserine using Red-VAD-FMK [Val-Ala-Asp(O-Me) fluoromethyl ketone] staining, a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, and double staining with annexin V-propidium iodide (PI). The concentration dependence (50% effective concentration [EC50]) and time course for polymyxin B-induced apoptosis were measured in NRK-52E and HK-2 cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with annexin V and PI. Polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in NRK-52E cells was confirmed by positive labeling from Red-VAD-FMK staining, TUNEL assay, and annexin V-PI double staining. The EC50 (95% confidence interval [CI]) of polymyxin B for the NRK-52E cells was 1.05 (0.91 to 1.22) mM and was 0.35 (0.29 to 0.42) mM for HK-2 cells. At lower concentrations of polymyxin B, minimal apoptosis was observed, followed by a sharp rise in the apoptotic index at higher concentrations in both cell lines. After treatment of NRK-52E cells with 2.0 mM polymyxin B, the percentage of apoptotic cells (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) was 10.9% ± 4.69% at 6 h and reached plateau (>80%) at 24 h, whereas treatment with 0.5 mM polymyxin B for 24 h led to 93.6% ± 5.57% of HK-2 cells in apoptosis. Understanding the mechanism of polymyxin B-induced apoptosis will provide important information for discovering less nephrotoxic polymyxin-like lipopeptides.

INTRODUCTION

Gram-negative pathogens, in particular Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, that are resistant to most current antibiotics present a significant problem globally (1, 2). Unfortunately, the development of new antibiotics to treat infections caused by these problematic pathogens has decreased precipitously over the last two decades (2). As a consequence, “old” polymyxins have been revived as a last-line therapy (3, 4). Two polymyxins, namely, polymyxin B and polymyxin E (synonym, colistin), have been available clinically since the late 1950s but were abandoned in the 1970s due to their potential for nephrotoxicity (5, 6). There is little doubt that there is an association between polymyxin therapy and nephrotoxicity (7–9), and recent clinical studies have shown that the incidence rate is up to 60%, depending on the definition of nephrotoxicity (7, 10–12). Unfortunately, the mechanism(s) of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity is not clear (13).

Acute tubular necrosis and increased serum creatinine concentrations have been reported associated with polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity (8, 14). Cumulative dose- and duration-dependent increases of serum creatinine have been observed in rats (15) and humans (16, 17) after intravenous administration of colistin methanesulfonate (CMS), an inactive prodrug of colistin. Pharmacokinetic studies indicated that both polymyxin B and colistin undergo very extensive net tubular reabsorption from tubular urine back into blood in the kidney (18, 19). Furthermore, colistin-induced tubular apoptosis in rats was reported, and coadministration of antioxidants appeared to be protective against colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (20–22). Therefore, it is very likely that polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity is related to kidney tubular cell apoptosis. Apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death (23), is characterized by a series of events, including activation of a family of cysteine-containing aspartate-directed proteases known as caspases (24, 25), condensation and fragmentation of nuclei (26, 27), mitochondrial alterations (28, 29), translocation of membrane phosphatidylserine (30, 31), formation of apoptotic bodies (26), and cell death (32). The mechanism(s) of polymyxin B-induced apoptosis has not been investigated. In the present study, we investigated the characteristics of polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in cultured rat and human kidney proximal tubular cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Polymyxin B (sulfate; catalog number 81334; lots 12168230506110 and BCBD1065V; minimum potency, 6,500 IU/mg, which is greater than the USP specification of not less than 6,000 IU/mg) and staurosporine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (NSW, Australia). A stock solution of 40 mM polymyxin B in Milli-Q water was prepared and sterilized with a syringe filter (Millex-GV; 0.22 μm; Millipore). Staurosporine stock solution (1 mM) was prepared in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA, USA) and used as a positive control.

Cell culture.

Rat (NRK-52E) and human (HK-2) kidney proximal tubular cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were employed. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was utilized for NRK-52E cells. HK-2 cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (BPE) (0.05 mg/ml) and human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) (5 ng/ml). All components of the growth medium were purchased from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Victoria, Australia). NRK-52E (0.5 × 105 cells/ml) and HK-2 (0.25 × 105 cells/ml) cells were seeded in 12-well plates or 8-well chamber slides in growth medium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 h and 48 h, respectively. The medium was then removed by aspiration, and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4; Invitrogen). The treatments described below were then conducted in DMEM supplemented with 0.1% FBS for NRK-52E cells and in K-SFM supplemented with BPE (0.05 mg/ml) and EGF (5 ng/ml) for HK-2 cells.

Assessment of polymyxin-induced caspase activation, DNA damage, and membrane translocation of phosphatidylserine.

Initially, activation of caspases, an essential step for the execution of apoptosis (24, 25), was examined using a CaspGLOW red active caspase staining kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA) (33). Briefly, NRK-52E cells were cultured in 12-well plates and incubated with or without polymyxin B (1.0 mM) for 24 h and then treated with Red-VAD-FMK [Val-Ala-Asp(O-Me) fluoromethyl ketone] (1:3,000) in DMEM at 37°C for 30 min. Activated caspases were detected by laser scanning microscopy (a Nikon A1-R confocal microscope with NIS-Element imaging software) using excitation/emission wavelengths of 561 nm and 570 to 600 nm. Staurosporine (1.0 μM)-treated cells were employed as the positive control. As activated caspases trigger caspase-activated DNase (CAD), an enzyme responsible for the fragmentation of DNA (34, 35), we further detected the DNA damage in polymyxin B-treated NRK-52E cells by in situ detection of DNA fragments using a TUNEL Universal Apoptosis Detection kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA). In the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, NRK-52E cells after incubation for 24 h in the presence or absence of polymyxin B (1.0 mM) on chamber slides (Nunc Lab-Tek Chamber Slide system; 8 wells on Permanox; Sigma-Aldrich) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by incubation for 10 min at 25°C with blocking solution (3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol). Then, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in aqueous 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium citrate, followed by incubation with TUNEL reaction mixture containing 45 μl equilibration buffer, 1 μl biotin-11-dUTP, and 4 μl terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) solution for 0.5 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate and 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS at 25°C for 10 min in the dark. Cells treated with 20.0 U/μl DNase I for 20 min were employed as the positive control. The samples were visualized using a Nikon A1-R confocal microscope with NIS-Element imaging software.

Membrane translocation of phosphatidylserine, another consequence of caspase activation (30, 31), was measured to assess polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in rat and human kidney proximal tubular cells by double staining with annexin V and PI. This was conducted using an Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V/Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Invitrogen) as described previously, with minor modifications (36, 37). Both NRK-52E and HK-2 cells were cultured in 12-well plates and incubated with or without polymyxin B (1.25 mM for NRK-52E cells and 0.5 mM for HK-2 cells) for 24 h. Staurosporine (1.0 μM) was employed as the positive control to induce apoptosis. After incubation, cells in plates were centrifuged (150 × g; 5 min), and the supernatant was discarded; then, PBS (pH 7.4) was added and the plates were centrifuged again (150 × g; 5 min). The PBS was discarded, and the cells were detached from the plates using 300 μl of trypsin-EDTA solution (0.25% and 0.05% for NRK-52E and HK-2 cells, respectively; Invitrogen) for ∼3 min at 37°C. The trypsin was inactivated with 1.0 ml of DMEM for NRK-52E cells and K-SFM for HK-2 cells. The cell suspension was centrifuged (450 × g; 5 min) in 1.5-ml tubes, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) and centrifuged (450 × g; 5 min). The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold 1× annexin-binding buffer. Five microliters of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated annexin V and 1.0 μl of PI (100 μg/ml) were added to the cell suspension and incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. Then, 0.4 ml of ice-cold 1× annexin-binding buffer was added, and induction of apoptosis was monitored immediately by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (FACSCanto II; Becton-Dickson, CA, USA). Fluorescence emission was measured at 530 and 575 nm using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Annexin V-positive/PI-negative and annexin V-positive/PI-positive cells were considered early and late apoptotic cells, respectively, and both were counted as total apoptotic cells (38). The percentage of apoptotic cells in the total number of cells is designated the apoptotic index.

Assessment of the concentration dependence and time course of polymyxin-induced apoptosis.

NRK-52E and HK-2 cells were cultured in 12-well plates and incubated with and without polymyxin B (final concentrations, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.0, and 4.0 mM for 24 h for NRK-52E cells and 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, and 0.5 mM for 16 h for HK-2 cells) to evaluate concentration-dependent apoptosis. The concentration of polymyxin B required to induce 50% of maximal apoptosis (50% effective concentration [EC50]) was calculated by fitting a Hill function, with basal response to account for the low degree of apoptosis in the absence of drug, using unweighted nonlinear least-squares regression analysis in GraphPad Prism (V5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Time-dependent induction of apoptosis was measured in the presence of polymyxin B (2.0 mM) at 1, 6, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h for NRK-52E cells and 0.5 mM polymyxin B at 6, 12, 16, and 24 h for HK-2 cells. Cells treated with staurosporine (1.0 μM) were employed as the positive control to induce apoptosis. Induction of apoptosis was measured by FACS as described above. All experiments were conducted in three independent replicates, and data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD).

RESULTS

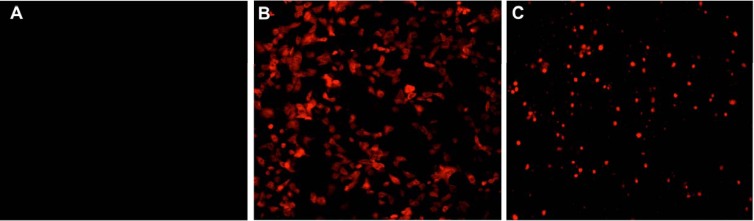

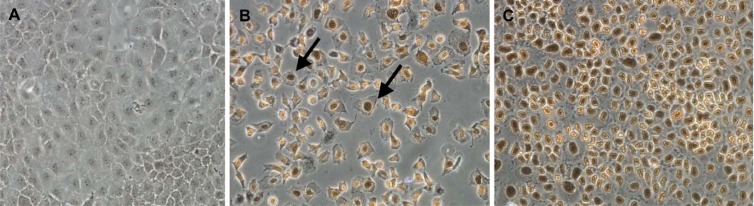

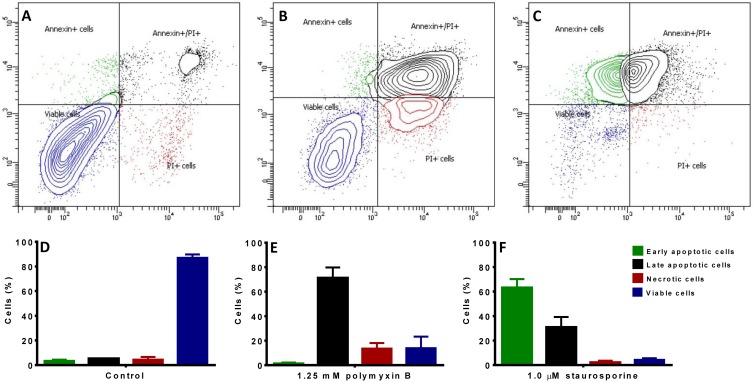

Unlike the untreated negative-control cells (Fig. 1A), pancaspase activation, a key characteristic of early-stage apoptosis, was observed in NRK-52E cells after 24 h of incubation with 1.0 mM polymyxin B, similar to the staurosporine-treated positive-control cells (Fig. 1B and C). DNA breakage, usually followed by activation of caspases, was also observed from in situ TUNEL staining; compared to the untreated control without TUNEL-positive nuclei (Fig. 2A), polymyxin B-treated NRK-52E cells showed dark-brown TdT-labeled nuclei (Fig. 2B), an important biochemical hallmark of apoptosis, similar to the nuclei of the DNase I-treated cells (Fig. 2C). Both the pancaspase activation and TUNEL assays indicated that polymyxin B induced apoptosis in rat kidney tubular cells. Subsequently, externalization of phosphatidylserine was examined in polymyxin B-treated NRK-52E and HK-2 cells. The untreated control NRK-52E cells showed minimal labeling (8.63% ± 0.9%) (Fig. 3A) with annexin V and annexin V-PI, compared to the labeling of the cells treated with polymyxin B (72.6% ± 7.9%) (Fig. 3B) and staurosporine (93.7% ± 1.4%) (Fig. 3C); the corresponding viability data are presented in Fig. 3D to F.

Fig 1.

Confocal microscopic visualization (magnification, ×20) of caspase activation in NRK-52E cells using Red-VAD-FMK staining. (A) Control cells. (B) 1.0 mM polymyxin B. (C) 1.0 μM staurosporine.

Fig 2.

Immunohistochemical images of apoptotic nuclei (arrows) in NRK-52E cells treated with vehicle (control) (A), 1.0 mM polymyxin B (B), and 20.0 U/μl DNase I (C).

Fig 3.

Double staining with annexin V and PI in NRK-52E cells. (A) Control cells. (B) 1.25 mM polymyxin B. (C) 1.0 μM staurosporine. In each panel, the upper left quadrant represents cells stained by annexin V (early-apoptotic cells), the bottom right quadrant represents cells stained by PI (necrotic cells), the upper right quadrant represents cells stained by both annexin V and PI (late-apoptotic cells), and the bottom left quadrant represents cells not stained by annexin V or PI (viable cells). (D to F) Viability data for panels A to C. (D) Control cells. (E) 1.25 mM polymyxin B. (F) 1.0 μM staurosporine. The error bars represent standard deviations (SD).

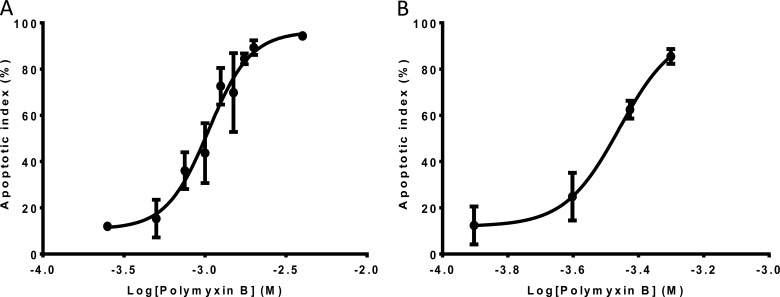

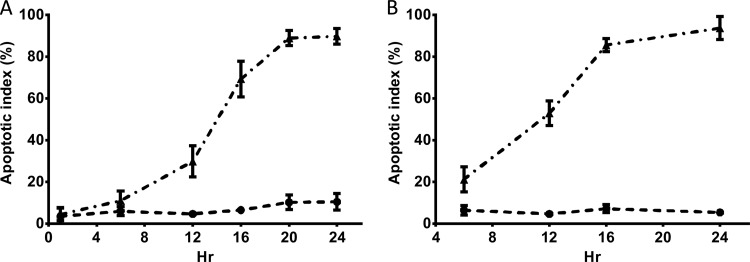

The concentration-dependent apoptosis induced by polymyxin B is shown in both NRK-52E and HK-2 cells (Fig. 4). Polymyxin B displayed EC50 (95% confidence interval [CI]) values of 1.05 (0.91 to 1.22) mM for NRK-52E cells after 24 h of incubation and 0.35 (0.29 to 0.42) mM for HK-2 cells after 16 h of incubation. After 24-h polymyxin B treatment with 2.0 mM for NRK-52E cells and 0.5 mM for KH-2 cells, the percentages of apoptotic cells were >80% for both cell lines (Fig. 4). Therefore, these concentrations of polymyxin B were employed for examination of time-dependent induction of apoptosis by polymyxin B (Fig. 4). The time dependence of polymyxin-induced apoptosis was also examined by FACS (Fig. 5). Minimal induction of apoptosis was observed at 6 h in NRK-52E cells treated with 2.0 mM polymyxin B, followed by rapid induction of apoptosis until 24 h, when a plateau was reached. Compared to NRK-52E cells, HK-2 cells appeared more susceptible to polymyxin B treatment. At 0.5 mM polymyxin B, rapid induction of apoptosis was observed up to 16 h with no substantial increase of the apoptotic index after 16 h. Similar time courses of apoptosis were also observed with human kidney proximal tubular HK-2 cells after treatment with a range of concentrations (0.125 to 1.0 mM) of polymyxin B (data not shown). The apoptotic indices of the untreated control cells of both NRK-52E and HK-2 did not change over the same period. Similar changes in viability were observed for both NRK-52E and HK-2 cells (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Apoptotic indexes of NRK-52E (A) and HK-2 (B) cells as a function of the polymyxin B concentration (24 and 16 h, respectively). Means ± SD (n = 3) are shown.

Fig 5.

Apoptotic indexes of NRK-52E (A) and HK-2 (B) cells incubated with polymyxin B (2.0 and 0.5 mM, respectively) for different times (mean ± SD; n = 3). ▲, polymyxin B treatment; ●, control treatment with vehicle only.

DISCUSSION

Based upon our recent pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies, the concentrations of both polymyxin B and colistin in plasma in many patients may be suboptimal with the currently recommended dosage regimens (19, 39–41). Administration of doses higher than those in the approved product information for polymyxins may be required to achieve optimal clinical efficacy; however, the potential for nephrotoxicity is a major dose-limiting factor (19, 39, 42). Our recent study in rats showed that colistin induced apoptosis in the kidney (21). The mechanism(s) of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity is poorly understood. The aim of the present study was to investigate polymyxin B-induced apoptosis in rat and human kidney proximal tubular cells.

Extensive tubular reabsorption of polymyxins was reported previously (18, 19, 43). This may lead to accumulation of polymyxins in kidney tubular cells, thereby predisposing to nephrotoxicity. The proximal tubule is the most common site of nephrotoxicity induced by many other toxicants (44–46). Therefore, immortalized tubular cell lines originating from rat and human kidney tissues are widely utilized for in vitro evaluation of the nephrotoxicity of drugs (44, 47, 48). A recent study using the porcine renal proximal tubular cell line LLC-PK1 showed that polymyxin B induced ∼50% necrosis at 0.5 mM and did not cause apoptosis when measured with the DNA-staining reagent 4′,6′-diamidine-2′-phenylindole (DAPI) (49). Unfortunately, DAPI is not specific for apoptosis measurement (50). Additionally, a low level of expression of unidentified transporter(s) responsible for polymyxin B uptake could be a potential explanation for the lack of apoptosis in LLC-PK1 cells after treatment with 0.5 mM polymyxin B (51). In the present study, NRK-52E rat kidney proximal tubular cells were first examined, as our previous polymyxin pharmacokinetic and nephrotoxicity studies were conducted in rats (15, 18, 22). Importantly, the concentration- and time-dependent apoptosis induced by polymyxin B in NRK-52E cells was also observed in the human kidney proximal tubular cell line HK-2 (Fig. 4 and 5).

Positive labeling with Red-VAD-FMK of NRK-52E cells exposed to polymyxin B showed the presence of activated caspases (Fig. 1). Activation of caspases is a common phenomenon in apoptosis of kidney tubular cells due to nephrotoxic injury (52, 53). Activation of caspases can be triggered by two potentially interacting and reversible pathways mediated by mitochondria (intrinsic) and cell surface death receptor (extrinsic) (54). Polymyxins are known to interact with phospholipids of membranes and strongly bind with mitochondria in mammalian cells (55, 56). Conceivably, activation of caspases by polymyxin B could be mediated by intrinsic and/or extrinsic pathways of apoptosis, and this warrants further investigation. Activated caspases are also essential for the regulation of CAD, a cytosolic endonuclease responsible for the DNA breakage activity that propagates apoptotic cell death (54). Therefore, in the present study, DNA breakage was investigated using an in situ TUNEL assay to detect the free ends of DNA after breakage, one of the important biochemical characteristics of apoptosis (57, 58). Dark-brown TdT-labeled nuclei were detected in the polymyxin B-treated cells, providing evidence for apoptosis (Fig. 2). This observation is consistent with the reported colistin-induced apoptosis in rat kidneys (21). For further investigation of polymyxin B-induced apoptosis, we utilized double staining with annexin V and PI. Apoptotic cells have externalized membrane phosphatidylserine; therefore, annexin V, a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein that binds to phosphatidylserine with high affinity, serves as an excellent quantitative apoptotic marker using FACS (59). Polymyxin B treatment (1.25 mM for 24 h) caused apoptosis in NRK-52E cells (annexin V-positive and annexin V-PI-positive cells; Fig. 3B), consistent with the results obtained with the pancaspase and TUNEL assays (Fig. 1 and 2). Furthermore, polymyxin B treatment led to rapid transition of the NRK-52E and HK-2 cells from early apoptosis to late apoptosis, as shown by the colabeling with both annexin V and PI. A key finding of the present study was that all three different assays, i.e., activation of caspases (Fig. 1), DNA damage (Fig. 2), and translocation of membrane phosphatidylserine (Fig. 3), confirmed that polymyxin B induced apoptosis in kidney tubular cells.

Using the quantitative FACS method, we revealed that polymyxin B induced apoptosis in a concentration- and time-dependent manner in both NRK-52E and HK-2 cells (Fig. 4 and 5). This finding is in line with the cumulative dose- and time-dependent kidney proximal tubular injury reported recently after intravenous administration of CMS in rats (15, 22) and humans (17). Additionally, dose-dependent kidney toxicity was also observed after polymyxin B treatment in rats (14). In the present study, the EC50 values of polymyxin B (0.35 and 1.05 mM for HK-2 and NRK-52E cells, respectively) are higher than the concentrations of colistin reported recently in the homogenate of kidney tissue (i.e., ∼ 0.1 mM) from rats with histological evidence of nephrotoxicity following several days of treatment with colistin (21). There are at least two potential explanations for this apparent discordance. First, the tissue concentration is an average value in the tissue homogenate that very likely does not represent the concentration of polymyxins within kidney tubular cells after extensive reabsorption. Second, in the cultured cells, uptake of polymyxins may be limited by the magnitude of the expression of an as-yet-unidentified transporter(s) compared to that in kidney tissue. In fact, there may be no disagreement between the EC50 values observed here and the concentration of polymyxins in rat kidney tissue homogenates (21). As demonstrated in the cell culture studies reported here, the extent of cell toxicity as measured by the apoptotic index is the result of the combination of time and concentration. In the cell culture studies, the incubation period was 16 or 24 h for HK-2 and NRK-52E cells, respectively, whereas in vivo (in rats or patients) nephrotoxicity may result from several days of exposure to concentrations that may be somewhat lower than those causing toxicity after 16 or 24 h in cell culture.

In the present study, the different EC50s of polymyxin B (0.35 and 1.05 mM for HK-2 and NRK-52 cells, respectively) between the human and rat cell lines suggest that polymyxin B-induced apoptosis is cell line dependent (Fig. 4 and 5). Clearly, our study highlights the need for further investigations into the mechanisms of polymyxin-induced apoptosis and its association with nephrotoxicity due to polymyxin treatment.

Conclusion.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal that polymyxin B induces apoptosis in rat and human kidney proximal tubular cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of polymyxin-induced apoptosis and nephrotoxicity may provide invaluable information for developing a novel therapeutic strategy using nephroprotectants and for discovering less nephrotoxic polymyxin-like lipopeptides for treatment of infections caused by the very problematic multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jumana Yousef for her technical support in cell culture and the TUNEL assay.

J.L., R.L.N., P.A.H., and T.V. are supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant (ID 1026109). J.L., R.L.N., and T.V. are also supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI098771). J.L. is an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellow, and T.V. is an Australian NHMRC Industry CDA Fellow.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE, Jr, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. 2006. Bad bugs need drugs: an update on the development pipeline from the Antimicrobial Availability Task Force of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:657–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergen PJ, Landersdorfer CB, Zhang J, Zhao M, Lee HJ, Nation RL, Li J. 2012. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ‘old' polymyxins: what is new? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 74:213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. 2005. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1333–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randall RE, Bridi GS, Setter JG, Brackett NC. 1970. Recovery from colistimethate nephrotoxicity. Ann. Intern. Med. 73:491–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price DJ, Graham DI. 1970. Effects of large doses of colistin sulphomethate sodium on renal function. BMJ 4:525–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubin CJ, Ellman TM, Phadke V, Haynes LJ, Calfee DP, Yin MT. 2012. Incidence and predictors of acute kidney injury associated with intravenous polymyxin B therapy. J. Infect. 65:80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. 2006. Toxicity of polymyxins: a systematic review of the evidence from old and recent studies. Crit. Care 10:R27. 10.1186/cc3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dezoti Fonseca C, Watanabe M, de Vattimo MDF. 2012. Role of heme oxygenase-1 in polymyxin B-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5082–5087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elias LS, Konzen D, Krebs JM, Zavascki AP. 2010. The impact of polymyxin B dosage on in-hospital mortality of patients treated with this antibiotic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2231–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kvitko CH, Rigatto MH, Moro AL, Zavascki AP. 2011. Polymyxin B versus other antimicrobials for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastewski AA, Caruso P, Parris AR, Dizon R, Kopec R, Sharma S, Mayer S, Ghitan M, Chapnick EK. 2008. Parenteral polymyxin B use in patients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia and urinary tract infections: a retrospective case series. Ann. Pharmacother. 42:1177–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. 2006. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelraouf K, Braggs KH, Yin T, Truong LD, Hu M, Tam VH. 2012. Characterization of polymyxin B-induced nephrotoxicity: implications for dosing regimen design. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4625–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace SJ, Li J, Nation RL, Rayner CR, Taylor D, Middleton D, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Turnidge JD. 2008. Subacute toxicity of colistin methanesulfonate in rats: comparison of various intravenous dosage regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1159–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falagas ME, Fragoulis KN, Kasiakou SK, Sermaidis GJ, Michalopoulos A. 2005. Nephrotoxicity of intravenous colistin: a prospective evaluation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 26:504–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartzell JD, Neff R, Ake J, Howard R, Olson S, Paolino K, Vishnepolsky M, Weintrob A, Wortmann G. 2009. Nephrotoxicity associated with intravenous colistin (colistimethate sodium) treatment at a tertiary care medical center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1724–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. 2003. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1766–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Cao GY, Superti SV, Lutz L, Barth AL, Ramos F, Boniatti MM, Nation RL, Li J. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:1298–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozyilmaz E, Ebinc FA, Derici U, Gulbahar O, Goktas G, Elmas C, Oguzulgen IK, Sindel S. 2011. Could nephrotoxicity due to colistin be ameliorated with the use of N-acetylcysteine? Intensive Care Med. 37:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, Nation RL, Li J. 2012. Ascorbic acid protects against the nephrotoxicity and apoptosis caused by colistin and affects its pharmacokinetics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:452–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, Nation RL, Li J. 2011. Melatonin attenuates colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4044–4049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC. 1997. Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell 88:347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hengartner MO. 2000. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samali A, Zhivotovsky B, Jones D, Nagata S, Orrenius S. 1999. Apoptosis: cell death defined by caspase activation. Cell Death Differ. 6:495–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. 1972. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 26:239–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyllie AH. 1980. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature 284:555–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenner C, Kroemer G. 2000. Apoptosis. Mitochondria—the death signal integrators. Science 289:1150–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green DR, Reed JC. 1998. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281:1309–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin SJ, Finucane DM, Amarante-Mendes GP, O'Brien GA, Green DR. 1996. Phosphatidylserine externalization during CD95-induced apoptosis of cells and cytoplasts requires ICE/CED-3 protease activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28753–28756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Frasch SC, Warner ML, Henson PM. 1998. The role of phosphatidylserine in recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 5:551–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balasubramanian K, Schroit AJ. 1998. Characterization of phosphatidylserine-dependent beta(2)-glycoprotein I macrophage interactions: implications for apoptotic cell clearance by phagocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29272–29277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verga Falzacappa C, Mangialardo C, Madaro L, Ranieri D, Lupoi L, Stigliano A, Torrisi MR, Bouche M, Toscano V, Misiti S. 2011. Thyroid hormone T3 counteracts STZ induced diabetes in mouse. PLoS One 6:e19839. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. 1998. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature 391:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S. 1998. Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature 391:96–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong XL, Jia RH, Yang DP, Ding GH. 2006. Irbesartan attenuates contrast media-induced NRK-52E cells apoptosis. Pharmacol. Res. 54:253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han KH, Lee UY, Jang YS, Cho YM, Jang YM, Hwang IA, Ghee JY, Lim SW, Kim WY, Yang CW, Kim J, Kwon OJ. 2007. Differential regulation of B/K protein expression in proximal and distal tubules of rat kidneys with ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292:F100–F106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonsson A, Persson JL. 2009. Induction of apoptosis by staurosporine involves the inhibition of expression of the major cell cycle proteins at the G(2)/M checkpoint accompanied by alterations in Erk and Akt kinase activities. Anticancer Res. 29:2893–2898 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, Paterson DL, Shoham S, Jacob J, Silveira FP, Forrest A, Nation RL. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3284–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Forrest A, Tsuji BT, Li J, Nation RL. 2010. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic investigation of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa using an in vitro model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3783–3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudhani RV, Turnidge JD, Nation RL, Li J. 2010. fAUC/MIC is the most predictive pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic index of colistin against Acinetobacter baumannii in murine thigh and lung infection models. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1984–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nation RL, Li J. 2009. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22:535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandri AM, Landersdorfer CB, Jacob J, Boniatti MM, Dalarosa MG, Falci DR, Behle TF, Bordinhao RC, Wang J, Forrest A, Nation RL, Li J, Zavascki AP. 23 June 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/cit334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen YC, Chen CH, Hsu YH, Chen TH, Sue YM, Cheng CY, Chen TW. 2011. Leptin reduces gentamicin-induced apoptosis in rat renal tubular cells via the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 658:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quiros Y, Vicente-Vicente L, Morales AI, Lopez-Novoa JM, Lopez-Hernandez FJ. 2011. An integrative overview on the mechanisms underlying the renal tubular cytotoxicity of gentamicin. Toxicol. Sci. 119:245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei Q, Dong G, Franklin J, Dong Z. 2007. The pathological role of Bax in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 72:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taneda S, Honda K, Tomidokoro K, Uto K, Nitta K, Oda H. 2010. Eicosapentaenoic acid restores diabetic tubular injury through regulating oxidative stress and mitochondrial apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 299:F1451–F1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JW, Bae EH, Kim IJ, Ma SK, Choi C, Lee J, Kim SW. 2010. Renoprotective effects of paricalcitol on gentamicin-induced kidney injury in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298:F301–F313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM, Denamur S, Vaara T, Vaara M. 2012. Novel polymyxin derivatives are less cytotoxic than polymyxin B to renal proximal tubular cells. Peptides 35:248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galluzzi L, Aaronson SA, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, Andrews DW, Baehrecke EH, Bazan NG, Blagosklonny MV, Blomgren K, Borner C, Bredesen DE, Brenner C, Castedo M, Cidlowski JA, Ciechanover A, Cohen GM, De Laurenzi V, De Maria R, Deshmukh M, Dynlacht BD, El-Deiry WS, Flavell RA, Fulda S, Garrido C, Golstein P, Gougeon ML, Green DR, Gronemeyer H, Hajnoczky G, Hardwick JM, Hengartner MO, Ichijo H, Jaattela M, Kepp O, Kimchi A, Klionsky DJ, Knight RA, Kornbluth S, Kumar S, Levine B, Lipton SA, Lugli E, Madeo F, Malomi W, Marine JC, Martin SJ, Medema JP, Mehlen P, Melino G, Moll UM, Morselli E, Nagata S, Nicholson DW, Nicotera P, Nunez G, Oren M, Penninger J, Pervaiz S, Peter ME, Piacentini M, Prehn JH, Puthalakath H, Rabinovich GA, Rizzuto R, Rodrigues CM, Rubinsztein DC, Rudel T, Scorrano L, Simon HU, Steller H, Tschopp J, Tsujimoto Y, Vandenabeele P, Vitale I, Vousden KH, Youle RJ, Yuan J, Zhivotovsky B, Kroemer G. 2009. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring cell death in higher eukaryotes. Cell Death Differ. 16:1093–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Girton RA, Sundin DP, Rosenberg ME. 2002. Clusterin protects renal tubular epithelial cells from gentamicin-mediated cytotoxicity. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282:F703–F709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jo SK, Cho WY, Sung SA, Kim HK, Won NH. 2005. MEK inhibitor, U0126, attenuates cisplatin-induced renal injury by decreasing inflammation and apoptosis. Kidney Int. 67:458–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Servais H, Van Der Smissen P, Thirion G, Van der Essen G, Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM, Mingeot-Leclercq MP. 2005. Gentamicin-induced apoptosis in LLC-PK1 cells: involvement of lysosomes and mitochondria. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 206:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cryns V, Yuan J. 1998. Proteases to die for. Genes Dev. 12:1551–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feingold DS, HsuChen CC, Sud IJ. 1974. Basis for the selectivity of action of the polymyxin antibiotics on cell membranes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235:480–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunin CM. 1970. Binding of antibiotics to tissue homogenates. J. Infect. Dis. 121:55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. 1992. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 119:493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gold R, Schmied M, Rothe G, Zischler H, Breitschopf H, Wekerle H, Lassmann H. 1993. Detection of DNA fragmentation in apoptosis: application of in situ nick translation to cell culture systems and tissue sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 41:1023–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, Keehnen RM, Pals ST, van Oers MH. 1994. Annexin V for flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on B cells undergoing apoptosis. Blood 84:1415–1420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]