Abstract

Vaginal infections caused by Candida glabrata are difficult to eradicate due to this species' scarce susceptibility to azoles. Previous studies have shown that the human cationic peptide hepcidin 20 (Hep-20) exerts fungicidal activity in sodium phosphate buffer against a panel of C. glabrata clinical isolates with different levels of susceptibility to fluconazole. In addition, the activity of the peptide was potentiated under acidic conditions, suggesting an application in the topical treatment of vaginal infections. To investigate whether the peptide activity could be maintained in biological fluids, in this study the antifungal activity of Hep-20 was evaluated by a killing assay in (i) a vaginal fluid simulant (VFS) and in (ii) human vaginal fluid (HVF) collected from three healthy donors. The results obtained indicated that the activity of the peptide was maintained in VFS and HVF supplemented with EDTA. Interestingly, the fungicidal activity of Hep-20 was enhanced in HVF compared to that observed in VFS, with a minimal fungicidal concentration of 25 μM for all donors. No cytotoxic effect on human cells was exerted by Hep-20 at concentrations ranging from 6.25 to 100 μM, as shown by 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide tetrazolium salt (XTT) reduction assay and propidium iodide staining. A piece of indirect evidence of Hep-20 stability was also obtained from coincubation experiments of the peptide with HVF at 37°C for 90 min and for 24 h. Collectively, these results indicate that this peptide should be further studied as a novel therapeutic agent for the topical treatment of vaginal C. glabrata infections.

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade there have been increasing reports of vaginitis due to non-albicans Candida species, which now accounts for 20% of Candida vaginal infections (1). Candida glabrata has emerged as an important fungal pathogen, and its clinical relevance is partially due to its intrinsic or rapidly acquired resistance to azole antifungal drugs, such as fluconazole, commonly used in the treatment of mucosal infections (1, 2). It has been postulated that the rise in C. glabrata prevalence from recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis observed in the last few decades is related to the widespread use of fluconazole, to which this species is less sensitive than C. albicans and other non-albicans Candida species (1, 2). Recent reports have revealed an increase of C. glabrata clinical isolates that display resistance not only to azoles but also to echinocandins (3, 4). This aspect complicates the management of C. glabrata vaginal infections, which, as a result, are difficult to eradicate and often end up in recurrent episodes (1).

Considering the limitations of the currently available antifungals, it has become mandatory to identify new classes of antimicrobial compounds to provide an effective antifungal strategy for a broad range of fungal pathogens, including C. glabrata.

In this regard, natural anti-infective agents, such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), represent a promising approach due to their wide-spectrum activity, rapid mode of action, and microbicidal effect on multiresistant microorganisms (5). Interactions between AMPs and the microbial surface play a crucial role in determining the activity of membrane-active AMPs. The positive charge of the vast majority of AMPs allows the initial interaction with the negatively charged cell wall and, later, with negatively charged phospholipids in the inner membrane. Following interaction with the lipid bilayer, most AMPs cause displacement of lipids, alteration of membrane structure, and membrane perforation (5).

Structurally different AMPs, obtained from different organisms, including amphibians, plants, and mammals, have been proven to exert antifungal activity versus clinically relevant Candida species (6). However, C. glabrata has been shown to be scarcely susceptible to a wide spectrum of AMPs of different derivations; among these are histatin, cathelicidins, defensins, and magainin (7–10).

We have previously shown that the human liver-derived peptide hepcidin 20 (Hep-20) exerts antifungal activity against C. glabrata clinical isolates characterized by different levels of susceptibility to fluconazole (11). In addition, the fungicidal effect exerted by Hep-20 on C. glabrata isolates in sodium phosphate buffer (SPB) was potentiated under acidic conditions (pH 5.0) (11), according to a proposed mechanism by which, at acid pH, protonated basic residues of Hep-20 facilitate the interaction with negatively charged fungal surfaces, as already reported for other peptides (12, 13). The enhanced fungicidal activity of Hep-20 observed under acidic conditions suggested that this peptide could be used as a therapeutic agent in the topical treatment of C. glabrata vaginal infection.

However, a direct in vitro application of promising AMPs as novel therapeutic agents has been held back by several limitations, including a significant reduction of their antimicrobial activity in the presence of biological fluids due to physiological concentrations of salts, such as K+, Na+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ (14–17). In addition, clinical trials performed so far on AMPs have been restricted to topical applications due to their poor bioavailability associated with host protease susceptibility and unknown toxicity profiles (18).

Therefore, to evaluate the potential application of Hep-20 in the topical treatment of C. glabrata vaginitis, the peptide activity was evaluated in (i) a vaginal fluid simulant (VFS), resembling human secretion, and (ii) in human vaginal fluid (HVF), collected from three healthy donors. In addition, despite the peptide previously being shown to produce no significant effect on human erythrocytes (11) and on erythroleukemia K562 human cells (19), we further investigated Hep-20 toxicity versus human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and an epithelial cell line (A459) by 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide tetrazolium salt (XTT) reduction assay and propidium iodide (PI) staining. Indirect evidence of the peptide stability was also obtained by coincubating Hep-20 in the presence of HVF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strain and growth media.

A Candida glabrata clinical isolate resistant to fluconazole (BPY44; MIC, 256 μg/ml) was used in this study (11). BPY44 was grown in Sabouraud broth (Liofilchem s.r.l., Teramo, Italy) at 30°C for 18 h. The strain was maintained on Sabouraud agar (Liofilchem s.r.l.) for the duration of the study.

Antimicrobial peptide.

Synthetic Hep-20 was purchased from Peptide Specialty Laboratories GmBH (Heidelberg, Germany). The physical properties of Hep-20 are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Hep-20 was diluted in Milli-Q water to obtain a stock solution of 8 mg/ml.

Fungicidal activity of Hep-20 in VFS.

A vaginal fluid simulant mimicking human vaginal secretions was used to evaluate whether the activity of Hep-20 was maintained under such conditions. The VFS was prepared as described by Owen and Katz and the solution pH adjusted to 4.5 using HCl, with the following composition: NaCl, 3.5 g/liter; KOH, 1.4 g/liter; Ca(OH)2, 0.22 g/liter; bovine serum albumin, 0.018 g/liter; lactic acid, 2 g/liter; acetic acid, 1 g/liter; glycerol, 0.16 g/liter; urea, 0.4 g/liter; and glucose, 5 g/liter (20).

The solution was then filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (Merck Millipore, Rome, Italy) and stored at −20°C prior to use. The fungicidal activity of Hep-20 against BPY44 was evaluated in a microdilution assay performed in VFS 4-fold-diluted in sterile deionized water to mimic average fluid dilution induced by vaginal suppository (21).

Briefly, the C. glabrata BPY44 fluconazole-resistant isolate was grown in Sabouraud medium to exponential phase at 30°C and suspended in deionized water at a concentration of 1 × 107cells/ml. Ten microliters of fungal suspension was incubated in the presence of Hep-20 (concentrations ranged from 25 to 100 μM) in 100 μl of VFS with and without EDTA, a chelator of divalent cations (1 mM final concentration).

Following a 90-min incubation, samples were diluted 10-fold in water, and 200 μl was plated onto Sabouraud plates and incubated for 24 h to determine the CFU number. The fungicidal effect was defined as a reduction in the number of viable yeast cells of ≥3 log10 CFU/ml compared to that of the untreated control (11, 13).

HVF extraction.

HVF was collected from three healthy donors (D1 to D3), who ranged in age from 26 to 42 years and had regular menstrual cycles of approximately 28 days. To account for protein content variability over the menstrual cycle, HVF was collected twice from two of the donors, before and after ovulation. The human vaginal fluid was collected as described by Valore and coworkers (22), with minor modifications: tampons (O.B. Pro Comfort Mini) were inserted in the vagina for 8 to10 h and then transferred into centrifuge tubes. Thirty ml of 10 mM SPB, pH 5.0, was added to each tampon and incubated under agitation at 37°C. The fluid retained in tampons following a 4-h incubation was squeezed out by centrifuging at 3,800 × g to remove epithelial cells and tampon debris. In order to reverse the extreme dilution due to the extraction procedure, the fluid was centrifuged through a 3-kDa filter spin unit (Merck, Millipore) for 3 to 4 h up to a final volume of 1 ml. The effective protein concentration of HVF was then measured by Lowry assay versus a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard solution (100 mg/liter BSA stock solution) (23). HVF was then diluted appropriately (final protein concentration, 2 g/liter) (24) and stored at −20°C until further use. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and all volunteers gave their informed written consent.

Fungicidal activity of Hep-20 in HVF.

The fungicidal activity of Hep-20 against BPY44 was evaluated by killing assay performed in HVF, quantified as described above, and diluted to a protein content of 2 g/liter (24). C. glabrata BPY44 was grown in Sabouraud medium to exponential phase at 30°C and suspended in deionized water at a concentration of 1 × 107cells/ml. Fungal suspensions were incubated in the presence of Hep-20 (ranging from 3.12 to 50 μM) in a 4-fold-diluted HVF in sterile deionized water with and without 1.5 mM EDTA (final volume of 100 μl). Following incubation for 15 min to 24 h at 37°C, each mixture was diluted 10-fold in water, and 200 μl was plated onto Sabouraud plates and incubated for 24 h to determine CFU numbers. The fungicidal effect was defined as a reduction in the number of viable yeast cells of ≥3 log10 CFU/ml compared to the untreated control (11).

Evaluation of Hep-20 degradation in HVF.

Hep-20 (5 μg) was incubated in 4-fold-diluted HVF from D1 and D2 for 90 min and for 24 h, respectively, at 37°C under agitation in the presence or absence of EDTA. Four-fold-diluted HVF with or without 1.5 mM EDTA was included in the analysis as a control. Hep-20 (5 μg) incubated alone was used as a negative control of degradation. Following incubation, samples and controls were boiled for 10 min in SDS-loading buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 10% glycerol) and separated on 17.5% Tricine-SDS-PAGE gels (25). Molecular mass markers (7 to 175 kDa) and samples were processed for 2 h in a stacking gel (4% polyacrylamide; Sigma-Aldrich) at 10 mA and for 4 h at 30 mA in a separating gel. Following electrophoresis, gels were stained with EZ blue reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Bands were visualized with the Image Master apparatus (VDS; GE Health Care, Milan, Italy). To evaluate the contribution of HVF proteases to Hep-20 degradation, experiments were performed in parallel in vaginal fluid pretreated to 100°C for 5 min to inactivate proteases (26).

PBMC isolation and A549 culturing.

Heparinized venous blood obtained from 6 healthy volunteers was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Euroclone, Milan, Italy) containing 10% (vol/vol) sodium citrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and layered on a standard density gradient (Lympholyte-H; Cedarlane, Euroclone). Following centrifugation at 160 × g for 20 min at room temperature, supernatant was removed, without disturbing the lymphocyte/monocyte layer at the interface, in order to eliminate platelets. The gradient was further centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected from the interface. Cells were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% sodium citrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and suspended in RPMI 1640 (Euroclone) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Euroclone) at a final cell concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml.

Human non-small-cell lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells (ATCC CCL-185; LGC Standards, Sesto San Giovanni, Italy) were cultured in tissue culture flasks in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) (Euroclone) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Cell cultures were maintained in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. When cells grew to confluence, they were treated with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) and split in new flasks.

PI staining of PBMCs and A549 cell line incubated with Hep-20.

Cell viability was analyzed by flow cytometry by evaluating PI incorporation in PBMCs and A549 cells after a 24-h exposure to Hep-20. Isolated PBMCs were seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate (1 × 105 cells/well), and Hep-20 was added to wells at a final concentration of 6.25 to 100 μM. Cells incubated with complete medium alone served as a negative control, while PBMCs incubated with cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) (2 mg/ml final concentration) were used as a positive control. Plates were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were then transferred into 12- by 75-mm polystyrene tubes and washed in Dulbecco's PBS (D-PBS; Euroclone), and 5 μl of a 50 mg/liter solution of PI (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each tube. Following an incubation at room temperature for 4 min in the dark, 15,000 events were acquired ungated in a flow cytometer (FACSort; BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) was used for computer-assisted analysis. In order to evaluate PI incorporation by A549, cells were detached with trypsin from a culture flask, counted, and suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine (5 × 104 cells/ml, final concentration). Two hundred microliters from the suspension was seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate (1 × 104 cells/well), and cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 24 h to allow adhesion. Fifty microliters of complete medium containing Hep-20 or cycloheximide at desired concentrations were then added to each well. Following a further 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed, and exposed to PI and analyzed as described for PBMCs. Experiments were repeated three times. The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated by subtracting spontaneous PBMC/A549 cell death, measured in cultures in the absence of Hep-20 or cycloheximide, according to the following formula: % cytotoxicity = [(PI-positive cellssample − PI-positive cellsspontaneous)/100 − (PI-positive cellsspontaneous)] × 100.

XTT reduction assay on PBMC and A549 cell line incubated with Hep-20.

The effect of Hep-20 on cell viability was also assessed using a colorimetric assay based on the reduction of XTT into a water-soluble orange formazan product by mitochondrial dehydrogenases of viable cells. The XTT-PMS solution was prepared according to Scudiero and colleagues (27). In order to improve cellular reduction of XTT, N-methylphenazonium methyl sulfate (PMS), an electron coupling agent, was used. Briefly, XTT (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared at 1 mg/ml in prewarmed (37°C) D-PBS and PMS at 5 mM in D-PBS (1.53 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich). A 0.025 mM PMS-XTT solution was prepared by mixing 5 ml of fresh XTT (1 mg/ml) and 25 μl of 5 mM PMS immediately before use and sterilized by filtration (0.22 μm; Millipore). PBMCs and A549 cells were suspended in complete medium and seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate as described above. Cells were then incubated with Hep-20 at desired concentrations (6.25 to 100 μM final concentrations), complete medium alone as a negative control, and Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) (0.5% [vol/vol] final concentration) as a positive control. After a 24-h incubation in the presence of 5% CO2, 50 μl of the XTT-PMS solution was added to each well. Following a further incubation (3 and 1 h for PBMCs and A549, respectively), the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was measured using a microplate reader (model 550; Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) in order to quantify the formazan production, which gave an indirect measure of cell viability. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated three times.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Instat software (GraphPad). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the activity of Hep-20 in VFS and HVF and for cytotoxicity studies. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Fungicidal activity of Hep-20 in VFS.

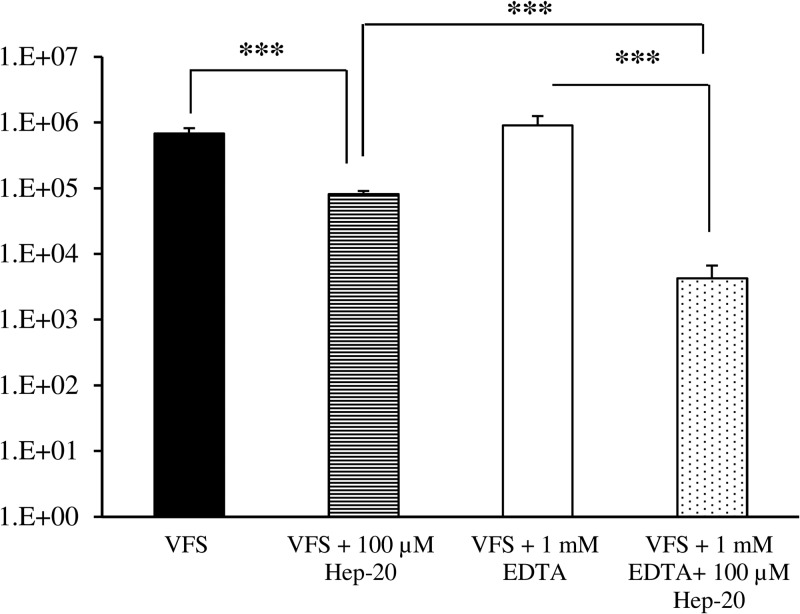

In order to evaluate whether the activity of Hep-20 was maintained in a biologic fluid simulant, killing assays on C. glabrata BPY44 were performed in a 4-fold-diluted artificial fluid (VFS) with Hep-20 concentrations ranging from 25 to 100 μM. Hep-20 did not produce any fungicidal effect (at least 3 log reduction in CFU number) at any of the concentrations tested (data not shown), but a significant reduction in BPY44 CFU number was observed only with the highest peptide concentration (Fig. 1). To evaluate whether the reduced activity of the peptide was due to the presence of inhibitory cations, experiments were repeated in 4-fold-diluted VFS supplemented with the chelating agent EDTA. Preliminary experiments performed using different EDTA concentrations (0.75 to 4 mM) indicated that 1 mM EDTA potentiated the peptide activity. As shown in Fig. 1, the addition of 1 mM EDTA to VFS significantly enhanced the antifungal activity of Hep-20 against C. glabrata at a concentration of 100 μM following a 90-min incubation period (P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA), demonstrating its fungicidal potential.

Fig 1.

Killing assay of C. glabrata BPY44 in 4-fold-diluted VFS, with and without 1 mM EDTA, in the presence of 100 μM Hep-20. Fungal cells incubated in the absence of Hep-20 serve as a viable control. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

Antifungal activity of Hep-20 in HVF.

Killing experiments were performed in 4-fold-diluted human vaginal fluid (HVF) collected from 3 healthy donors (D1 to D3). The total protein content in HVF was quantified by Lowry assay, and the fluid was diluted to obtain a protein concentration of 2 g/liter. This value was chosen to represent an average protein content of HVF, which was reported to vary between 0.018 and 3.75 g/liter (24).

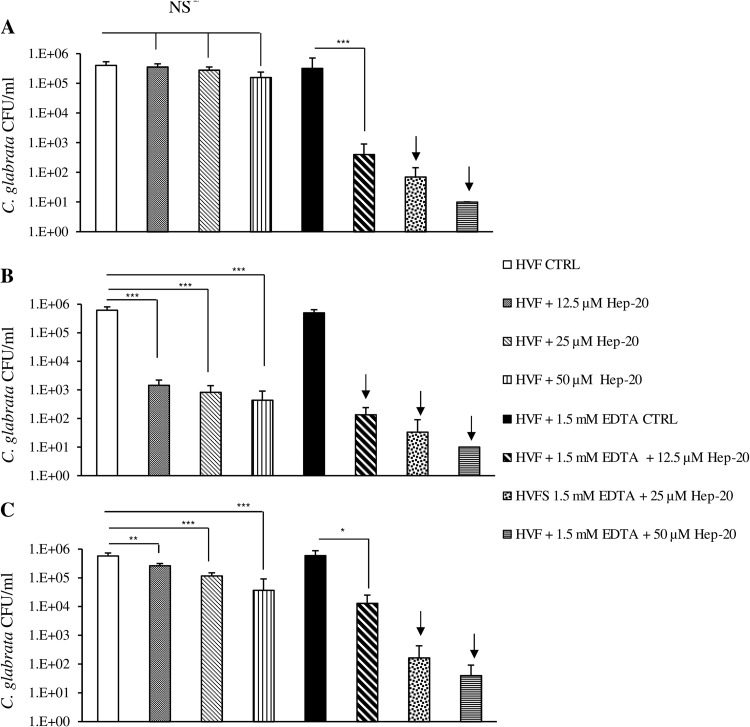

When the peptide was coincubated for 90 min at 37°C with C. glabrata in the presence of HVF from D1, no antifungal activity of Hep-20 was observed up to a concentration of 50 μM. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2A, no significant difference was observed between untreated control and treated samples for all of the peptide concentrations tested (12.5 to 50 μM). Notably, this results was not confirmed when fluid from donor 2 was used in the killing assay. In this case, a highly significant reduction in C. glabrata CFU number could be evidenced in HVF (P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2B). Fluid from donor 3 gave an intermediate result with a significant decrease in HVF fungal burden (P = 0.0003 by one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2C) following 90 min of incubation at 37°C. In an attempt to restore the peptide activity, which could have been hampered by ion concentration, experiments were performed in parallel using human vaginal fluid supplemented with EDTA.

Fig 2.

Fungicidal activity of Hep-20 against C. glabrata BPY44 in 4-fold-diluted HVF from donor 1 (D1) (A), donor 2 (D2) (B), and donor 3 (D3) (C). Fungal cells incubated in the absence of Hep-20 serve as a viable control (CTRL). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations from at least three independent experiments. The arrows indicate fungicidal effect. NS, not significant. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Preliminary experiments performed on 4-fold-diluted HVF and different EDTA concentrations indicated that 1.5 mM EDTA potentiated the Hep-20 activity in HVF, producing a fungicidal effect with 50 μM Hep-20 (data not shown).

Coincubation of Hep-20 with HVF from the three donors in the presence of 1.5 mM EDTA restored fungicidal activity following 90 min of incubation at 37°C, with a minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC) of 25 μM (Fig. 2A and C) and 12.5 μM (Fig. 2B). Although not fungicidal, even the lowest peptide concentration used (12.5 μM) caused a significant reduction in BPY44 CFU number in vaginal fluid collected from D1 and D3 (Fig. 2A and C; P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively).

Experiments were repeated using vaginal fluid from donors 1 and 2, collected before and after ovulation. For each of the two donors, the results obtained in HVF collected before ovulation did not significantly differ from those obtained with HVF collected postovulation (data not shown).

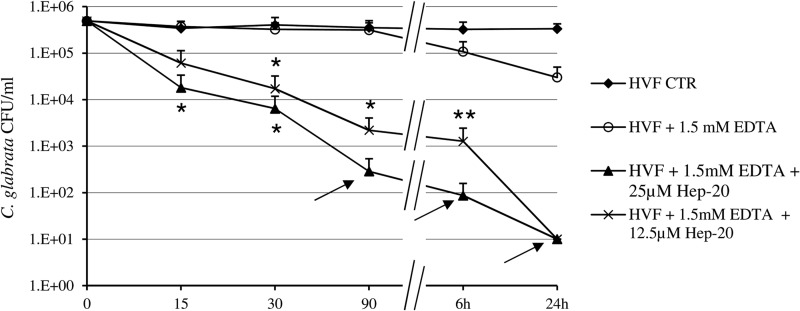

Time-killing assay of 12.5 and 25 μM Hep-20 versus BPY44 performed in HVF from donor 1 confirmed that the highest peptide concentration exerts a fungicidal effect following 90 min of incubation in the presence of 1.5 mM EDTA (Fig. 3). Notably, a statistically significant reduction in fungal cell number (P < 0.05) was observed starting at 15 min of incubation with 25 μM Hep-20 and at 30 min with 12.5 μM Hep-20 (Fig. 3). When coincubation was prolonged to 24 h, Hep-20 produced a fungicidal effect at a lower concentration as well (12.5 μM) (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Time-kill curves of Hep-20 (12.5 and 25 μM) against C. glabrata BPY44 in 4-fold-diluted HVF from D1 with and without 1.5 mM EDTA. Fungal cells incubated in the absence of Hep-20 served as a viable control (CTRL). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. The arrows indicate fungicidal effect. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Evaluation of Hep-20 degradation in HVF.

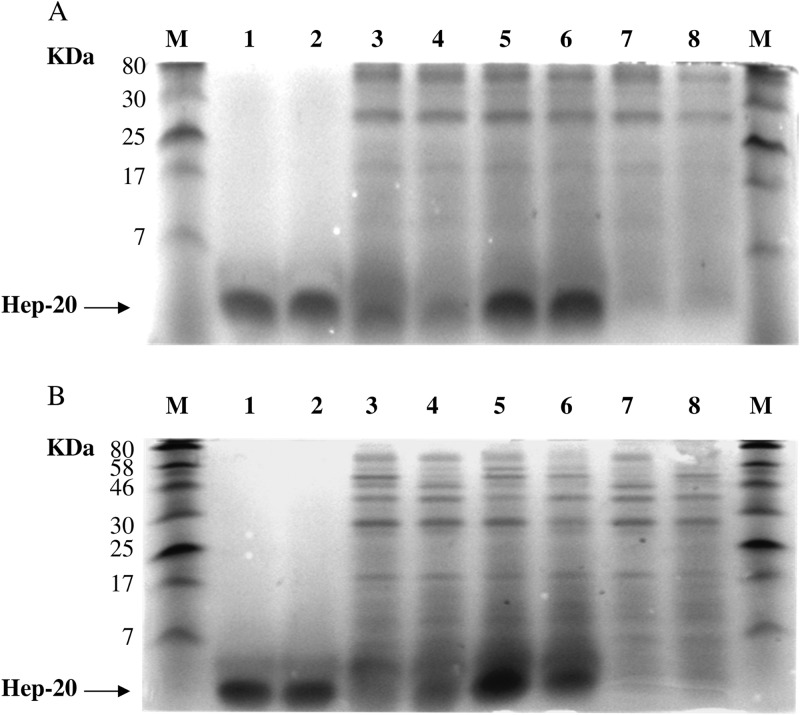

The stability of Hep-20 was evaluated by coincubating the peptide in the presence of HVF collected from two healthy donors (D1 and D2). The peptide was incubated in the presence of 4-fold-diluted HVF for 90 min and for 24 h at 37°C. In parallel, the same experiment was performed on HVF preheated at 100°C for 5 min to inactivate proteases in the fluid. Samples, including HVF plus Hep-20 with and without 1.5 mM EDTA, HVF plus EDTA, Hep-20 alone (5 μg), and Hep-20 alone incubated for 90 min and for 24 h, were separated in a 17.5% Tricine SDS-PAGE gel. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, no band corresponding to the molecular mass of Hep-20 (lanes 1 and 2) could be observed in 4-fold-diluted HVF (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 7 and 8). Coincubation for 90 min and for 24 h at 37°C of the peptide with HVF from D1 (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 3 and 4) resulted in a partial degradation of Hep-20 compared to that of the peptide alone (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 1 and 2). Preheating of HVF resulted in a complete lack of peptide degradation (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 5 and 6). The same results were obtained with HVF from donor 2, with a similar extent of peptide degradation (data not shown).

Fig 4.

SDS-PAGE gels of the peptide alone and coincubated in the presence of HVF from donor D1 following 90 min in HVF at 37°C (A) and 24 h of incubation in HVF at 37°C (B). Lane M, molecular marker (7–175 kDa); 1, Hep-20 (5 μg); 2, Hep-20 (5 μg) plus 1.5 mM EDTA; 3, HVF plus Hep-20; 4, HVF plus 1.5 mM EDTA plus Hep-20; 5, HVF (preheated at 100°C for 5 min) plus Hep-20; 6, HVF (preheated at 100°C for 5 min) plus Hep-20 plus 1.5 mM EDTA; 7, HVF plus 1.5 mM EDTA; 8, HVF (preheated at 100°C for 5 min) plus 1.5 mM EDTA.

Propidium iodide staining.

The potential cytotoxic activity of Hep-20 was assessed by PI staining of PBMC and A549. To this aim, PBMC and A549 cell suspensions were incubated for 24 h in the presence of Hep-20 at concentrations ranging from 6.25 to 100 μM and in the presence of 2 mg/ml cycloheximide as a positive (death) control. PBMC and A549 cellular suspensions were coincubated with PI for 4 min and then processed by flow cytometry. Hep-20 produced a negligible cytotoxic effect at all of the concentrations tested on PBMC and A549, with more than 90% viable cells posttreatment.

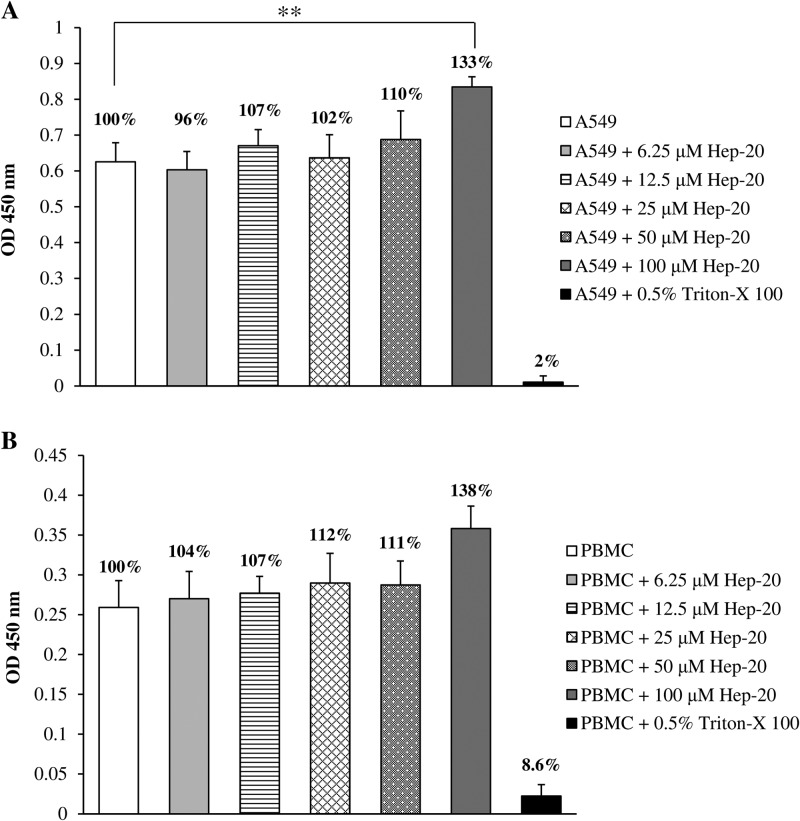

XTT reduction assay.

The cytotoxicity of Hep-20 on PBMC and on a human-derived epithelial cell line (A549) was also assessed by XTT assay. PBMC and A549 cell suspensions were incubated for 24 h in the presence of different concentrations of Hep-20 (6.25 to 100 μM) and in the presence of 0.5% Triton-X as a positive (death) control. Following this incubation, PBMC and A549 cellular suspensions were coincubated with XTT for 3 and 1 h, respectively, at 37°C, and OD450 values provided information on cell metabolic activity. Notably, none of the Hep-20 concentrations tested (6.25 to 100 μM) showed any cytotoxic effect on PBMC and A549 cells (Fig. 5A and B). Instead, a stimulatory effect could be observed at the highest peptide concentration tested, which was statistically significant in the case of A549 (Fig. 5A; P = 0.0033 by one-way ANOVA).

Fig 5.

OD values (at 450 nm) of formazan salt production by A549 cells (A) and PBMCs (B) incubated with concentrations of Hep-20 ranging from 6.25 to 100 μM. Triton X-100 (0.5%, vol/vol) served as a positive control. The vitality percentage, shown for each condition, was calculated by considering the negative control as 100% viability. Data are expressed as means from three separate experiments ± standard errors of means. **, P = 0.0033.

DISCUSSION

Candida glabrata vaginitis is difficult to treat due to an intrinsic reduced susceptibility to azoles, in particular to fluconazole, which is widely used for the topical treatment of this mycosis (1, 28). For this reason, there is an urgent need to individuate novel strategies for the treatment of these mycoses. In this regard, the therapeutic potential of natural anti-infective agents, such as AMPs, has generated much interest due to the potential therapeutic approaches that these molecules offer (5).

The present study was focused on human Hep-20, which was demonstrated to exert antimicrobial activity against clinically relevant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species (13).

We have recently shown that Hep-20 produced a fungicidal effect on C. glabrata clinical isolates with different levels of fluconazole susceptibility (11). This finding was particularly interesting in view of the scarce susceptibility this species presents to AMPs as well as to azoles (3, 7–10). Furthermore, the enhanced fungicidal activity of Hep-20 observed under acidic conditions suggested that this peptide could be used as a therapeutic agent of C. glabrata-related infections in body regions characterized by low pH, such as the vaginal region (11). No data are currently available with regard to the mode of action of Hep-20 on C. glabrata. Indirect information can be extrapolated from a recent study based on the interaction between Hep-20 and Escherichia coli (29). This study demonstrates a greater tendency of the peptide to destabilize the E. coli membrane under acidic conditions than at neutral pH through formation of pores, as evidenced by the release of β-galactosidase from Hep-20 treated cells at pH 5.0 and formation of blebs (29).

To verify the applicability of the peptide in the vaginal environment, the antifungal activity of Hep-20 was measured in an artificial vaginal fluid simulating human vaginal secretions (VFS). Considering that the average volume of vaginal fluid ranges from 0.5 to 0.75 ml (21), in our experiments VFS was diluted 4-fold to mimic fluid dilution by a vaginal suppository (20, 21).

In this experimental condition, the Hep-20 fungicidal effect previously observed in SPB (11) was not confirmed for any of the concentrations tested (25 to 100 μM). This finding suggested that Hep-20 activity could be inhibited by the presence in the medium of VFS components, such as BSA, and mono- and divalent cations, such as Ca2+, K+, and Na+ (20). Indeed, the antimicrobial activity of several AMPs has been shown to be markedly reduced in biological fluids due to the presence of proteins, other components, or physiological concentration of salts, such as K+, Na+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ (14–17).

Among the different mechanisms proposed to explain the loss of antimicrobial activity of AMPs in biological fluids, it has been hypothesized that the presence of divalent cations, such as calcium and magnesium, mediates an electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged membrane of microorganisms. This creates a barrier preventing the interaction between AMPs and microbial plasma membrane. In an attempt to restore the activity of the peptide in VFS, experiments were repeated in the presence of 1 mM EDTA. This synthetic chelating agent forms strong complexes with cations, and it is widely used as a stabilizer in food and in pharmaceutical vaginal applications (30, 31). In vitro studies have demonstrated that prolonged exposure of ectocervical tissue to EDTA can produce a toxic effect at concentrations higher than 2.5 mM (31). Furthermore, EDTA has been demonstrated to inhibit hyphal development in C. albicans and to exert antifungal activity against Saccharomyces cerevisiae at concentrations of 10 and 17 mM, respectively (30, 32). In a study performed on human saliva by Wei and Bobek, the addition of EDTA enhanced the antifungal activity of different peptides, such as MUC7, histatin 5, and magainin, against C. albicans compared to saliva alone (14).

In our experiments, the addition of EDTA to the VFS resulted in a significant enhancement of Hep-20 fungicidal activity against C. glabrata BPY44 following 90 min of incubation at 30°C. This finding reinforced the view that divalent cations inhibit the activity of Hep-20: the presence of EDTA most likely enhanced Hep-20 activity by removing cations that protect the cell membrane from interaction with the peptide or by sequestering ions which are required by fungal intracellular enzymes (14, 30).

This finding was particularly interesting in view of a potential application of this peptide in the topical treatment of fungal vaginitis. To further pursue this possibility, the fungicidal activity of Hep-20 was evaluated in HVF collected from 3 healthy donors (D1 to D3) and diluted to a final protein concentration of 2 g/liter to consider HVF biological variability (24).

Killing experiments in HVF indicated that a biological variability occurred among vaginal fluid collected from three different donors, since for two of them a significant reduction in the number of viable fungal cells was induced by Hep-20 in the fluid alone following 90 min of incubation at 37°C. However, in the case of D1, no antifungal activity was observed in HVF in the absence of EDTA. This finding indicates that vaginal fluid composition differentially affects the peptide activity. Indeed, it is recognized that HVF contains several AMPs, such as calcoprotectin, lysozyme, SLPI, HBD1-2, HNP1-3, and LL-37, which could act synergistically with Hep-20, overcoming the natural inhibitory effect caused by ions or other fluids components (22, 26, 33). Notably, when 1.5 mM EDTA was added to the HVF, Hep-20 exerted a complete fungicidal effect versus C. glabrata BPY44 following 90 min of incubation, and it was maintained after 24 h of incubation. Interestingly, the Hep-20 MFC that produced a fungicidal effect was 25 μM for all donors, a quarter of the peptide concentration that significantly reduced fungal cell number in VFS. In addition, experiments performed using HVF collected before and after ovulation gave similar results for each of the donors considered, suggesting that variation of HVF composition during the menstrual cycle does not significantly influence Hep-20 activity. Overall, the results obtained on Hep-20 fungicidal activity in VFS and, more importantly, in HVF reinforced the view that this peptide is a promising candidate for topical treatments of C. glabrata vaginal infections.

In order to assess the potential of Hep-20 as a therapeutic agent against C. glabrata vaginal infections, we investigated whether the peptide retains its activity in physiological conditions. The results obtained in this study demonstrated that Hep-20 maintains its antifungal activity in the presence of EDTA at pH, salt concentration, and protein content similar to those found in vivo (VFS). Moreover, this finding was also confirmed when the peptide activity was evaluated in HVF. At present, no data are available with regard to the stability of the peptide in HVF. Indirect evidence of Hep-20 stability was obtained in this study from coincubation experiments of the peptide with HVF at 37°C at two different time points, 90 min and 24 h. SDS-PAGE gels indicated that when the peptide was coincubated with HVF left unsupplemented or supplemented or with 1.5 mM EDTA, Hep-20 was partially degraded at the two time points considered. However, when the peptide was coincubated with preheated HVF, Hep-20 gave a band similar in intensity to that of the untreated peptide, suggesting that the partial degradation observed was mainly due to fluid trypsin-like proteases. Indeed, a proteomic analysis on cervicovaginal fluids identified several proteases, such as serine (e.g., kallikreins) and cysteine (e.g., cathepsins) ones, which could degrade Hep-20 (26, 39). Further experiments will be required to understand the exact mechanism leading to this partial peptide degradation following 90 min or 24 h of incubation in HFV. Nevertheless, killing experiments performed in HVF clearly demonstrated that, even if partially degraded, the peptide is still able to exert fungicidal activity against C. glabrata at both 90 min and within 24 h. However, the partial degradation of the peptide may be overcome by synthesizing hepcidin-derived peptides containing d-amino acids and/or by incorporating these peptide analogues in nanoparticles, enhancing the bioavailability of Hep-20 in HVF.

Even if Hep-20 is a human-derived peptide, therapeutically active concentrations can be higher than physiological ones. Therefore, it is mandatory to investigate the potential cytotoxic effects exerted by this peptide on human cells. Previous data report a lack of hemolytic effect on human erythrocytes (11).

In this study, we expanded upon the Hep-20 cytotoxicity experiments by evaluating the effect of different peptide concentrations on human PBMC and a human-derived epithelial cell line (A549) by PI staining and XTT reduction assay. The results obtained showed that all Hep-20 concentrations tested (6.25 to 100 μM) produced negligible or no cytotoxic effect on PBMC and A549 cells, as demonstrated by PI staining and XTT assay. These results are in agreement with a study by Park and coworkers in which Hep-20 was tested for cytotoxicity on erythroleukemia type K562 human cells at concentrations of up to 30 μM (about 3,000-fold higher than that found in urine), with no significant effect on human cells (88% viable cells post treatment) (19).

It is worth underlining that Hep-20 produced a significant increase in A549 cell metabolism at the highest concentration tested (100 μM). This result is not surprising, since it is reported that some antimicrobial peptides, such as hBD-2, are able to induce A549 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (34). In addition, the role of AMPs in wound healing is supported by data on the activity of cathelicidin LL-37, hBD-2, and hBD-3 (35–37). These peptides are highly expressed in epidermal keratinocytes in response to injury or infection of the skin (35–37). It has also been shown that treatment with exogenous hBD-3 leads to an enhanced re-epithelialization of wounds in animal models (37). Hep-20 shares a high structural homology with defensins, and it could exert a similar stimulatory effect on A549 cells (38).

In conclusion, despite the fact that further studies are still needed to characterize the peptide mode of action and to optimize Hep-20 fungicidal activity, our results indicate that this peptide or its derivatives should be further studied as novel therapeutic agents for the control of vaginal C. glabrata infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support was obtained from Fondi di Ateneo, University of Pisa.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00904-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kennedy MA, Sobel JD. 2010. Vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by non-albicans Candida species: new insights. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 12:465–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter SS, Galask RP, Messer SA, Hollis RJ, Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA. 2005. Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida species causing vulvovaginitis and epidemiology of recurrent cases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2155–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfaller MA. 2012. Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am. J. Med. 125(Suppl. 1):S3–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrosky-Zeichner L. 2013. Candida glabrata and FKS mutations: witnessing the emergence of the true Multidrug-Resistant Candida. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56:1733–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancock RE, Sahl H-G. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zasloff M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joly S, Maze C, McCray PB, Jr, Guthmiller JM. 2004. Human beta-defensins 2 and 3 demonstrate strain-selective activity against oral microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1024–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmerhorst EJ, Venuleo C, Beri A, Oppenheim FG. 2005. Candida glabrata is unusual with respect to its resistance to cationic antifungal proteins. Yeast 22:705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmerhorst EJ, Venuleo C, Sanglard D, Oppenheim FG. 2006. Roles of cellular respiration, CgCDR1, and CgCDR2 in Candida glabrata resistance to histatin 5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1100–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benincasa M, Scocchi M, Pacor S, Tossi A, Nobili D, Basaglia G, Busetti M, Gennaro R. 2006. Fungicidal activity of five cathelicidin peptides against clinically isolated yeasts. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:950–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavanti A, Maisetta G, Del Gaudio G, Petruzzelli R, Sanguinetti M, Batoni G, Senesi S. 2011. Fungicidal activity of the human peptide hepcidin 20 alone or in combination with other antifungals against Candida glabrata isolates. Peptides 32:2484–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kacprzyk L, Rydengård V, Mörgelin M, Davoudi M, Pasupuleti M, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A. 2007. Antimicrobial activity of histidine-rich peptides is dependent on acidic conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768:2667–2680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maisetta G, Petruzzelli R, Brancatisano FL, Esin S, Vitali A, Campa M, Batoni G. 2010. Antimicrobial activity of human hepcidin 20 and 25 against clinically relevant bacterial strains: effect of copper and acidic pH. Peptides 31:1995–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei GX, Bobek LA. 2005. Human salivary mucin MUC7 12-mer-L and 12-mer-D peptides: antifungal activity in saliva, enhancement of activity with protease inhibitor cocktail or EDTA, and cytotoxicity to human cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2336–2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batoni G, Maisetta G, Esin S, Campa M. 2006. Human beta-defensin-3: a promising antimicrobial peptide. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 6:1063–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei GX, Campagna AN, Bobek LA. 2007. Factors affecting antimicrobial activity of MUC7 12-mer, a human salivary mucin-derived peptide. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maisetta G, Di Luca M, Esin S, Florio W, Brancatisano FL, Bottai D, Campa M, Batoni G. 2008. Evaluation of the inhibitory effects of human serum components on bactericidal activity of human beta defensin 3. Peptides 29:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeung AT, Gellatly SL, Hancock RE. 2011. Multifunctional cationic host defence peptides and their clinical applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68:2161–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park CH, Valore EV, Waring AJ, Ganz T. 2001. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7806–7810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen DH, Katz DF. 1999. A vaginal fluid stimulant. Contraception 59:91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai BE, Xie YQ, Lavine ML, Szeri AJ, Owen DH, Katz DF. 2008. Dilution of microbicide gels with vaginal fluid and semen simulants: effect on rheological properties and coating flow. J. Pharm. Sci. 97:1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valore EV, Park CH, Igreti SL, Ganz T. 2002. Antimicrobial components of vaginal fluid. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 187:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomás MS, Nader-Macías ME. 2007. Effect of a medium simulating vaginal fluid on the growth and expression of beneficial characteristics of potentially probiotic lactobacilli, p 732–739 In Méndez-Vilas A. (ed), Communicating current research, educational topics and trends in applied microbiology. Formatex, Badajoz, Spain [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schägger H, von Jagow G. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw JL, Smith CR, Diamandis EP. 2007. Proteomic analysis of human cervico-vaginal fluid. J. Proteome Res. 6:2859–2865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scudiero DA, Shoemaker RH, Paull KD, Monks A, Tierney S, Nofziger TH, Currens MJ, Seniff D, Boyd MR. 1988. Evaluation of a soluble tetrazolium/formazan assay for cell growth and drug sensitivity in culture using human and other tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 48:4827–4833 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Fiori B, Ranno S, Torelli R, Fadda G. 2005. Mechanism of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:668–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisetta G, Vitali A, Scorciapino MA, Rinaldi AC, Petruzzelli R, Brancatisano FL, Esin S, Stringaro A, Colone M, Luzi C, Bozzi A, Campa M, Batoni G. 2013. pH-dependent disruption of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and model membranes by the human antimicrobial peptides hepcidin 20 and 25. FEBS J. 280:2842–2854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubo I, Lee SH, Ha TJ. 2005. Effect of EDTA alone and in combination with polygodial on the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53:1818–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sassi AB, Cost MR, Cole AL, Cole AM, Patton DL, Gupta P, Rohan LC. 2011. Formulation development of retrocyclin 1 analog RC-101 as an anti-HIV vaginal microbicide product. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2282–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gil ML, Casanova M, Martínez JP. 1994. Changes in the cell wall glycoprotein composition of Candida albicans associated to the inhibition of germ tube formation by EDTA. Arch. Microbiol. 161:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh PK, Tack BF, McCray PB, Jr, Welsh MJ. 2000. Synergistic and additive killing by antimicrobial factors found in human airway surface liquid. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 279:L799–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhuravel E, Shestakova T, Efanova O, Yusefovich Y, Lytvin D, Soldatkina M, Pogrebnoy P. 2011. Human beta-defensin-2 controls cell cycle in malignant epithelial cells: in vitro study. Exp. Oncol. 33:114–120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorschner RA, Pestonjamasp VK, Tamakuwala S, Ohtake T, Rudisill J, Nizet V, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL. 2001. Cutaneous injury induces the release of cathelicidin anti-microbial peptides active against group A Streptococcus. J. Investig. Dermatol. 117:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sørensen OE, Cowland JB, Theilgaard-Mönch K, Liu L, Ganz T, Borregaard N. 2003. Wound healing and expression of antimicrobial peptides/polypeptides in human keratinocytes, a consequence of common growth factors. J. Immunol. 170:5583–5589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch T, Spielmann M, Zuhaili B, Fossum M, Metzig M, Koehler T, Steinau HU, Yao F, Onderdonk AB, Steinstraesser L, Eriksson E. 2009. Human beta-defensin-3 promotes wound healing in infected diabetic wounds. J. Gene Med. 11:220–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan JB, Poppe L, Haniu M, Arvedson T, Syed R, Li V, Kohno H, Kim H, Schnier PD, Harvey TS, Miranda LP, Cheetham J, Sasu BJ. 2009. Hepcidin revisited, disulfide connectivity, dynamics, and structure. J. Biol. Chem. 284:24155–24167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moncla BJ, Pryke K, Rohan LC, Graebing PW. 2011. Degradation of naturally occurring and engineered antimicrobial peptides by proteases. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2:404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.