Abstract

A 70-year-old male rural worker was referred to our clinic with widespread grey pigmentation of the skin and nails. The condition had been asymptomatic for its entire duration (5 years). He reported past intranasal application of 10% Silver Vitellinate. A skin biopsy was performed and histology corroborated the clinical diagnosis of Argyria. This case represents a currently rare dermatological curiosity. Although silver colloids and salts have been withdrawn and/or banned by some drug surveillance agencies, they continue to be freely sold and unregulated as food supplements and as ingredients in alternative medicines, thereby risking the emergence of new cases of silver poisoning.

Keywords: Argyria, Silver compounds, Skin pigmentation

Abstract

Um homem de 70 anos, trabalhador rural, foi referenciado à nossa consulta por dermatose assintomática, com 5 anos de evolução, caracterizada pela pigmentação acinzentada generalizada da pele, mais evidente em áreas fotoexpostas, e das lâminas ungueais. Relatava no passado o uso prolongado de Vitelinato de Prata a 10%, por via nasal. Foi efetuado exame histológico de biopsia cutânea que corroborou o diagnóstico clínico de Argiria. O caso representa uma curiosidade dermatológica, atualmente rara. Apesar de abandonados e/ou proibidos por algumas instituições de farmacovigilância, a prata coloidal e sais de prata continuam a ser comercializados como suplementos alimentares, como parte de medicinas alternativas e sem regulação, podendo fazer ressurgir os casos associados à toxicidade pela prata.

INTRODUCTION

The medicinal use of silver dates back to the beginning of medical history. Its current routine use as mainly an antibacterial and antifungal agent in chronic wound care products, medical devices and certain textiles, calls for a reappraisal of one of its potential side effects.

Argyria is a rare disease caused by the chronic absorption of products with a high silver content which surpass the body's renal and hepatic excretory capacities, leading to silver granules being deposited in the skin and its appendages, mucosae and internal organs (including the eye, kidney, spleen, bone marrow and central nervous system), and causing them to acquire a blue-grey pigmentation.1 The amount of absorbed silver required to cause generalized Argyria pigmentation is unknown. Several different types of exposure (accidental, therapeutic, occupational and environmental), routes of administration (oral, intranasal and percutaneous) and intervals of exposure from 8 months to 5 years have been described.2-6

Skin pigmentation is caused not only by silver deposition (in sulfite or selenite forms) in the dermis but also, according to some authors, by the stimulation of melanine synthesis. The reason why the grey color is more evident on photoexposed skin areas is unknown. It is believed that silver attains a brownish-black tone through a chemical reduction reaction or through a photomediated exacerbation of its stimulatory effect on melanine synthesis.1

Except in cases involving abrupt absorption of exaggerated amounts of silver, cases of significant morbi/mortality are extremely rare. The quantity of silver present within the bodies of Argyria patients has no significant effects on health, notwithstanding cosmetic considerations.6,7 It is generally considered to be an incurable condition, with no known way of removing the silver deposits from affected tissues. We identified an isolated report on the use of Nd:YAG Q-switched laser which resulted in the skin being returned to normal pigmentation.8

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old male rural worker, with a part history of chronic sinusitis and diagnosed with colon adenocarcinoma around one month prior to our observation, was referred to us with widespread grey pigmentation of the skin and nails (Figures 1 and 2). The condition had been asymptomatic for its entire duration (5 years). The patient denied the use of drugs, namely fenotiazines, antimalarials, amiodarone and mynocicline.

FIGURE 1.

Grey pigmentation of the skin, mainly visible on the head and photoexposed areas of the neck and neckline

FIGURE 2.

Grey pigmentation of the fingers and nail plates in their entirety

However he reported past intranasal application of 10% Silver Vitellinate as a nasal decongestant and antiseptic. He could provide no details of the posology or length of application of this drug, allegedly prescribed by his otolaryngologist. He denied any other forms of contact with silver in his job or elsewhere. We observed diffuse grey pigmentation of the skin (more evident on sun-exposed areas), and also of the oral and labial mucosae and nail plates.

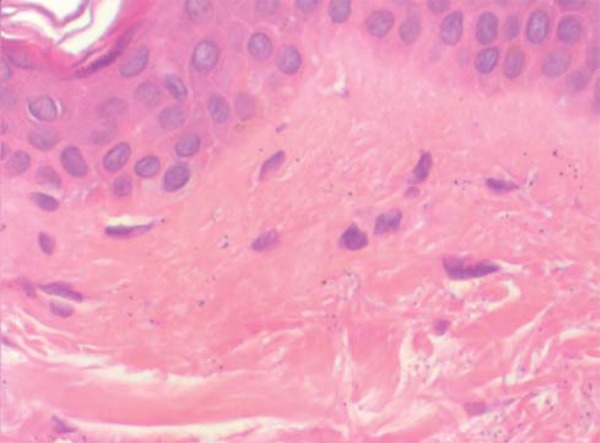

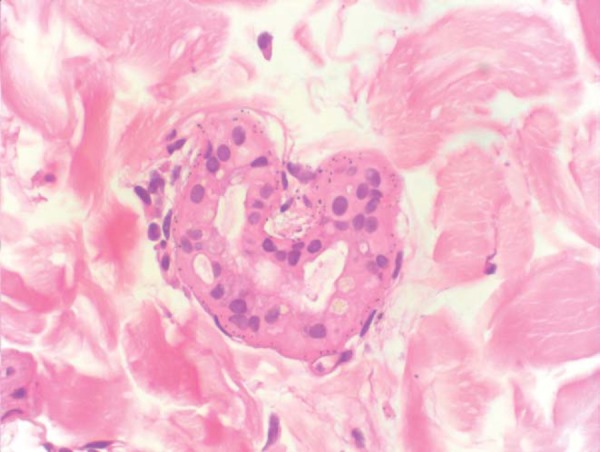

Blood tests failed to reveal any apparent alterations, namely in electrolytes, or in the metabolism of iron or copper. Histological examination of a biopsy of photoexposed truncal skin revealed an unaltered dermal and epidermal architecture, deposition of extracellular brownish-grey granules at the dermis, sparing the epidermis, arranged in clusters or individually, in a greater amounts at the basal membrane of the eccrine glands (Figures 3 and 4).

FIGURE 3.

Histopathological examination of the skin fragment revealed free brown/grey granules on the upper dermis (H&E ´ 400)

FIGURE 4.

Brown/grey granules in a linear fashion on the basal membrane of eccrine glands (H&E ´ 400)

Bearing in mind the diagnosis of Argyria, the recent identification of a locally advanced rectum adenocarcinoma, the patient's age and overall clinical status, only measures associated with the aggravating factors were addressed i.e. to limit the amount of unprotected sun exposure. The patient declined further suggested follow up, having decided that his main priority was to care for his cancer.

DISCUSSION

In this particular case, identification of the vehicle, exclusion of other concomitant drugs and clinical and histological tests confirmed the diagnosis of Argyria.9

Other ingested substances and certain specific diseases may however produce abnormal cutaneous pigmentation and clinical signs similar to those encountered in Argyria. Substances and diseases that may induce a grayish-blue tone resulting from photoaggravation include amiodarone, phenotiazines, criryasis, hemochromatosis. Meanwhile, bisbutya etc can cause a generalized, uniform effect, while predominantly localized reactions can be the result of ochronosis, mynocicline specific type II pigmentation pattern, antimalarials and a number of topicals. Blueish (eventually grayish) pigmentation of the nail plate may also be observed with antimalarials, minocycline or gold salts (more rarely).

The pattern of histological alterations induced by a cutaneous pigmentation agent is sometimes specific. In this case, the identification of extracellular clusters of granules disposed in a linear pattern on the basal membrane of eccrine glands was sufficient to corroborate the diagnosis of Argyria. (Chart 1).9

Chart 1.

Main differential diagnoses of Argyria

| Disease | Chemical Substance(s) | Presentation | Histology |

| OCHRONOSIS | Blue, Black/Blue pigmentation, mainly localized. | Collagen fiber basophilia. | |

| Alkaptonuria | Unmetabolized Homogentisic Acid | Autossomic Recessive Disease. | Free coarse deposits or intrahistiocytic, perivascular or periadnexal granules. |

| Exogenous Ochronosis | Phenol derivatives (e.g. antimalarials) | The pigment distribution depends on administration route. | |

| Reversible. | |||

| HEMOCHROMATOSIS | Iron (hemosiderin) | Generalized Hyperpigmentation (blue-grayish pigmentation possible) (photoaggravated). | Hypermelanosis of the basal cell layer. Hemosiderin granules within histiocytes and on the basal membrane of sweat glands. Perls +* |

| Reversible. | |||

| CHRYSIASIS | Gold (e.g. gold salts) | Generalized blue-grey pigmentation (photoaggravated). | Perivascular and intrahistiocytic granules on the intermediate and upper dermis. |

| Irreversible. | |||

| PHENOTIAZINES | (e.g. chlorpromazine) | Generalized blue-grey pigmentation (photoaggravated). | Intrahistiocytic, perivascular and free superficial granules. |

| Reversible. | |||

| MINOCYCLINE | Several patterns. | Intrahistiocytic and perivascular pigment. Perls +, Fontana-Masson + | |

| In type II pattern there is blue-grey localized pigmentation on the limbs. Reversible. | |||

| AMIODARONE | Generalized blue-grey pigmentation (photoaggravated). | Perivascular intrahistiocytic pigment on the intermediate dermis. | |

| Reversible. | Fontana-Masson +, PAS +, Ziehl-Neelsen + e Sudan black + |

* - The "+" sign denotes findings highlighted by the stain mentioned.

However, except for cases involving heavy metals, the skin biopsy may not always allow drug-induced pigmentation to be distinguished from other causes which may be equally responsible for an increase in melanogenesis. If the patient's clinical history offers few explanations it might prove worthwhile to measure the metal concentrations in blood, urine or skin. Electron microscopy, if and when available, could also be useful.

Although withdrawn (and banned) by some drug surveillance agencies such as the FDA, colloidal silver and/or silver salts are still sold as food supplements, as ingredients in alternative medicines and are easily available on the Internet and can even be prepared at home. In such circumstances an increase in cases associated with silver toxicity cannot be ruled out.3,10

Certain regulated silver-containing materials are nevertheless still available for medicinal use. These include dental amalgam, nanocrystalline dressings or silver foams, silver sulfadiazine in cream or impregnated dressings, silver nitrate pencils and silver fibers in specialized clothing fabrics. In all these formulations percutaneous absorption is possible. While an intact cutaneous barrier is effective against silver penetration, special attention should however be paid to products designed to apply to lesions or burn areas, and which can lead to cases of localized or (more rarely) systemic Argyria.1,4

Footnotes

Study conducted at Santo António dos Capuchos Hospital - Central Lisbon Hospital Center (E.P.E)- Lisbon, Portugal

Conflict of interest: None

Financial funding: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Lansdown A. A pharmacological and toxicological profile of silver as an antimicrobial agent in medical devices. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/910686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowden L, Rover M, Hallman J, Lewin-Smith M, Lupton G. Rapid onset of Argyria induced by a silver-containing dietary supplement. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:832–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon H, Lee J, Lee S, Lee A, Choi J, Ahn Y. A Case of Argyria following colloidal silver ingestion. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:308–310. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher N, Marsh E, Lazova R. Scar-localized Argyria secondary to silver sulfadiazine cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:730–732. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(02)61574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson R, Elliott V, Mondry A. Argyria: permanent skin discoloration following protracted colloid silver ingestion. BMJ Case Reports. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prescott R, Wells S. Systemic argyria. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:556–557. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.6.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirsattari S, Hammond R, Sharpe M, Leung F, Young G. Myoclonic status epiplepticus following repeated oral ingestion of colloidal silver. Neurology. 2004;62:1408–1410. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120671.73335.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han TY, Chang HS, Lee HK, Son SJ. Successful treatment of Argyria using a lowfluence Q-switched 106-nm Nd:YAG laser. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:751–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dereure O. Drug induced skin pigmentation. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;2:253–262. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt D, Park B, Hoang M, Jacobe H. Argyria secondary to ingestion of homemade silver. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S105–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]