Abstract

Purpose

To use beveled femtosecond laser astigmatic keratotomy (FLAK) incisions to treat high astigmatism after penetrating keratoplasty.

Methods

Paired FLAK incisions at a bevel angle of 135 degrees, 65% to 75% depth, and arc lengths of 60 to 90 degrees were performed using a femtosecond laser. One case of perpendicular FLAK was presented for comparison. Vector analysis was used to calculate the changes in astigmatism. Fourier domain optical coherence tomography was used to examine incision morphology.

Results

Wound gaping requiring suturing was observed in the case of perpendicular FLAK. Six consecutive cases of beveled FLAK were analyzed. Fourier domain optical coherence tomography showed that beveled FLAK caused a mean forward shift of Bowman layer anterior to the incisions of 126 ± 38 μm, with no wound gaping. The mean magnitude of preoperative keratometric astigmatism was 9.8 ± 2.9 diopters (D), and postoperatively it was 4.5 ± 3.2 D (P < 0.05). Uncorrected visual acuity improved from 1.24 ± 0.13 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution preoperatively to 0.76 ± 0.38 postoperatively (P < 0.05). Best spectacle–corrected visual acuity improved from 0.43 ± 0.33 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution preoperatively to 0.27 ± 0.24 postoperatively (P = 0.22). Visual results were reduced in 2 patients by cataract progression. Between 1 and 3 months after beveled FLAK, the keratometric cylinder was stable (<1 D change) in 5 of 6 patients, and regressed in 1 patient. No complications occurred.

Conclusions

Beveled FLAK incisions at varied depth are effective in the management of postkeratoplasty astigmatism. Early postoperative changes stabilized within 1 month in most patients. Further studies are needed to assess long-term outcomes.

Keywords: femtosecond laser, beveled, keratotomy, astigmatism, penetrating keratoplasty

Astigmatism is a major factor compromising visual recovery after penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), with magnitudes greater than 5 diopters (D) occurring in up to 38% of cases.1 Numerous approaches have been used to address this problem, including manual2 and mechanized arcuate keratotomy,3,4 compression sutures,5 photorefractive keratectomy (PRK),6 and laser in situ keratomileusis.7,8 Until recently, the technique of manual curved astigmatic keratotomy, originally popularized by Merlin,9,10 has been the most widely used procedure for the treatment of astigmatism greater than 6 D. However manual astigmatic keratotomy is associated with poor reliability and predictability in terms of astigmatism reduction, and associated complications include perforation, infection, gaping of the incision, and irregular astigmatism.

The advent of the femtosecond laser has brought promise of improved accuracy, safety, and reproducibility in the treatment of high postkeratoplasty astigmatism.11 The same program settings on the femtosecond laser, which are used to create precise graft–host matching in femtosecond-enabled keratoplasty, can be used to create astigmatic keratotomy stromal incisions with precisely customized shape, depth, and orientation.12 Several authors have reported positive results with femtosecond laser astigmatic keratotomy (FLAK) at 90 degrees to the corneal surface, and complication rates such as full thickness perforation are lower with this technique.11–15 However, FLAK with a 90-degree incision orientation is still associated with the same problem of wound gaping that occurs with manual astigmatic keratotomy incisions. The gaping astigmatic incision becomes filled with an epithelial plug (Fig. 1A), followed by gradual extrusion of the plug, and replacement with hypercellular scar tissue, a process that can take from 6 months to 5 years.16 This process may explain late changes in corneal curvature, which occur because of increased separation of the edges of the wound. A gaping keratotomy incision is also a potential site for infectious keratitis and causes sensations of grittiness and discomfort for the patient.

FIGURE 1.

OCT of (A) perpendicular astigmatic keratotomy incision and (B) beveled incision. A, FLAK incisions were made perpendicular to the corneal surface in one patient. Postoperatively this patient had marked discomfort due to gaping of the incision, and required suturing. Even after suturing (arrow) there remained an epithelial plug in the wound (red circle). B, After a FLAK incision beveled at 135 degrees, forward shift of the Bowman layer is evident anterior to the incision. No wound gape or epithelial plug formation occurred.

In this preliminary study, we evaluated the effect on postkeratoplasty astigmatism of a FLAK incision, which is beveled at a 135-degree angle. We hypothesized that by creating a beveled incision, the anterior cornea would slide forward for a short distance relative to the cornea posterior to the incision, thereby leading to an increase in curvature of the anterior cornea and a corresponding reduction in astigmatism while simultaneously avoiding wound gape (Fig. 1B). Therefore, we conducted a small pilot study to test the efficacy and safety of beveled FLAK incisions for the correction of post-keratoplasty astigmatism.

METHODS

The study design was a prospective noncomparative interventional case series. The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California.

Study inclusion criteria were high postkeratoplasty astigmatism, complete removal of sutures at least 6 months before FLAK, contact lens intolerance, and a stable refractive error. Corneal topography was evaluated by standard axial power display from the Orbscan II system (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY). Eyes with a high degree of topographic bowtie astigmatism were included. Moderate asymmetry or skew in the bowtie pattern were accepted, but highly irregular patterns of topographic astigmatism were excluded from FLAK.

Patients were reviewed at 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months postoperatively. Preoperative and postoperative evaluations included uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) and best spectacle–corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), slit-lamp examination, tonometry, and subjective refraction. Intraoperative pachymetry was performed with a 50 MHz ultrasound pachymeter (Corneo-Gage Plus; Sonogage, Inc, Cleveland, OH).

Beveled FLAK Technique

The paired arcuate incisions were placed on the steep corneal hemimeridians as identified on the axial power maps of each eye. The arc lengths were determined by the astigmatism magnitude and ranged from 60 to 90 degrees. Because of the small optical zone diameter, arc length less than 60 degrees may create split steep axis and lead to irregular astigmatism, whereas arc length more than 90 degrees can be counterproductive. Graft vertical and horizontal diameters were measured with a caliper and averaged. The incisions were placed 0.4 mm inside the graft margin in all cases. We placed the beveled FLAK incisions within the graft to preserve the integrity of the host rim so that subsequent regrafting procedures would not be adversely affected.17 The % incision depth was adjusted for each eye according to the magnitude of topographic astigmatism to be corrected.

The incision bevel angle was 135 degrees (anterior side cut). We selected a 135-degree angle for the incision because that was the maximum bevel angle (45 degree deviation from 90 degrees) that we thought could be practically used without excessively limiting the optical zone diameter. Assuming a corneal thickness of 600 μm and a 70% incision depth, if we used 150 degrees (60-degree deviation from 90 degrees) bevel, then the optical zone diameter would be reduced by 1.45 mm, compared with 0.84 mm with a 135-degree incision, as demonstrated by the following equations:

All surgeries were performed under topical anesthesia using the Intralase 60 kHz femtosecond laser (AMO, Inc, Santa Ana, CA). The 3 and 9-o’clock axes were marked on the limbus at a slit lamp. A speculum was used to keep the eye open and the eye was centered under an operating microscope. The 3, 6, 9, and 12-o’clock positions were marked with a surgical marker pen (Gentian violet) just outside the edge of the graft under the operating microscope. The axis of the steep meridians was not marked during the surgery. A central 6-mm ring mark was placed on the corneal graft. Three ultrasound pachymetry measurements were taken between this mark and the graft edge along the planned incision path for each arc. The minimum pachymetry from the 6 measurements (3 from each arc) was multiplied by the planned % depth to obtain the absolute incision depth setting for the laser. The speculum was then removed and the operative eye was centered under the femtosecond laser. The head was positioned so that the cardinal ink marks were aligned with the cardinal positions on the laser’s video display. After placement of the suction ring and applanation lens, the incision positions on the laser’s monitor screen were centered on the graft edge using computerized controls. The beveled FLAK incisions were programmed as anterior side cuts at an angle of 135 degrees on the Intralase enabled keratoplasty software program. The pulse energy setting was 1.4 μJ. Incision depth ranged between 65% and 75% of the minimum pachymetry (most frequently 70% depth was used). Paired simultaneous incisions were made on opposite steep hemimeridians. In cases of skewed astigmatism, skewed incisions corresponding to the steep astigmatic meridians were used, leaving a minimum of 90 degrees uncut between incisions. Asymmetric arc lengths were used to correct asymmetric bowtie astigmatism. The arc lengths ranged between 60 and 90 degrees.

After the creation of the paired arcuate incisions with the femtosecond laser, the suction ring and applanation cone were removed. The speculum was replaced and the eye was again centered under the surgical microscope. The incisions were opened under the guidance of a keratoscopic reflection using a Sinskey hook. At the end of surgery, drops of topical antibiotic (0.3% gatifloxacin) and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory (bromfenac sodium 0.09%) were placed on the surface of the eye. Postoperatively, the operative eyes received topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1%) and antibiotic eye drops 4 times daily for 1 week.

Analysis of Astigmatism

Vector analysis of astigmatism,18–21 including on-axis analysis22–24 was performed in this study. The astigmatic analysis terminology used in this article was adapted from the scheme described by Huang et al22 and Eydelman et al.20 We will use case 1 as an example to show the definition of terms.

Cardinal and Oblique Components of Astigmatism

The magnitude of preoperative keratometric astigmatism is 12.00 D with a steep axis of 148 degrees. Then, the cardinal component of preoperative keratometric astigmatism (KAc-pre) is:

The oblique component of preoperative keratometric astigmatism (KAo-pre) is:

The magnitude of postoperative keratometric astigmatism is 4.70 D with a steep axis of 37 degrees.

Then the cardinal component of postoperative keratometric astigmatism (KAc-post) is:

The oblique component of postoperative keratometric astigmatism (KAo-post) is:

Intended Astigmatic Correction

The intended astigmatic correction is the negative of the preoperative keratometric astigmatism. It represents the cylindrical lens that is needed to cancel preexisting keratometric astigmatism. For this example, the intended astigmatic correction has a magnitude of 12.00 D and an axis of 58 degrees (90 degrees from preoperative steep axis).

Surgically Induced Astigmatic Correction

The surgically induced astigmatic correction (SIAC) is the vector difference between the postoperative keratometric astigmatism and preoperative keratometric astigmatism.

The cardinal component of SIAC is:

The oblique component of SIAC is:

The magnitude of SIAC is:

The axis of SIAC is:

Error of Angle

The error of angle (EA) measured whether the treatment was applied at the correct axis.20 It is the angular difference between the axis of SIAC and the axis of the intended astigmatic correction. In this example,

On-Axis Astigmatism Analysis

On-axis astigmatism analysis measures how much SIAC was along the axis of intended correction22–24 (hence the name “on-axis”).

The SIAC along the axis of intended correction (on-axis SIAC) is:

Therefore, the residual astigmatism along the axis of intended correction is:

Ideally, the above value should be zero. A positive value indicates undercorrection and a negative value indicates overcorrection.

The SIAC orthogonal to the axis of intended correction (off-axis SIAC) is:

Ideally, the EA and off-axis SIAC should be zero.

Relating Magnitude of SIAC to the Depth and Arc Length of FLAK Incision

Because the effect of the incision is related to both depth and arc lengths, we devised a composite measure of the magnitude of incision:

Optical Coherence Tomography

A Fourier domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) system operating at 830-nm wavelength (RTVue with corneal adaptor module by Optovue Inc, Fremont, CA) was used to obtain cross-sectional images of the beveled FLAK incisions. The system had a transverse scan width of 6 mm, an axial resolution of 5 μm, and a speed of 26,000 axial scans per second. Topography and line scans were performed for all patients in the study. Line scans were 6 mm in length and perpendicular to and centered on the FLAK incision arcs. The number of frames averaged for each line scan was 16.

Bowman layer visualized on OCT was used as the landmark for measuring the forward shift after beveled FLAK. The distance between Bowman layer at the inner and outer edges of the beveled FLAK incision was measured using the caliper function on the RTVue Fourier domain OCT.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of visual acuities was performed in units of logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR). The Student paired t test was used to assess the difference between preoperative and postoperative vision and refraction. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Operative and Clinical Findings

We performed FLAK incisions oriented perpendicular to the corneal surface in one patient. Postoperatively this patient had marked discomfort because of gaping of the incision, which was filled by an epithelial plug (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no epithelial plug formation was seen after beveled FLAK incisions (Fig. 1B).

We performed beveled FLAK incisions for the correction of postkeratoplasty astigmatism in 6 eyes of 6 patients. The incision arc lengths were 78 ± 8 degrees (mean ± standard deviation; range, 60–90 degrees). The incision depth was 71 ± 4% of corneal thickness (range, 65%–75%). Four cases had skewed steep axes on corneal topography. In these cases, the placement of the arcuate FLAK incisions was skewed up to 20 degrees to match the topographies (Table 1). In one case of asymmetric astigmatism, we made a longer incision arc on the steeper hemimeridian (Fig. 2). However, despite the increased arc length, the meridians just outside the arc remained steep after the procedure, creating irregular astigmatism (Fig. 2C). This effect would have been more marked if a shorter arc had been used.

TABLE 1.

Data on Visual Acuities, Keratometric Astigmatism, Beveled FLAK Treatments Performed, and Outcomes for Each Patient

| Case | Preoperative Snellen UCVA | Preoperative Keratometric Astigmatism (D) | Preoperative Axis | FLAK Incision Depth (%) | FLAK Arc 1 Axis (degrees) | FLAK Arc 1 Length (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20/200 | 12 | 148 | 75 | 150 | 60 |

| 2 | 20/30 | 7.9 | 95 | 65 | 94 | 80 |

| 3 | 20/40 | 10.7 | 78 | 70 | 70 | 80 |

| 4 | 20/50 | 9.7 | 121 | 75 | 115 | 80 |

| 5 | 20/25 | 5.34 | 15 | 70 | 20 | 70 |

| 6 | 20/80 | 13.3 | 95 | 71 | 85 | 82 |

| Case | FLAK Arc 2 Axis (degrees) | FLAK Arc 2 Length (degrees) | Postoperative Snellen UCVA | Postoperative Keratometric Astigmatism (D) | Postoperative Axis (degrees) | Achieved SIAC Magnitude (D) | EA (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 325 | 90 | 20/70* | 4.7 | 37 | 15.81 | −5.7 |

| 2 | 280 | 80 | 20/60* | 3.1 | 95 | 4.80 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 270 | 80 | 20/20 | 1.2 | 58 | 9.81 | 2.3 |

| 4 | 305 | 80 | 20/50 | 2.8 | 135 | 7.35 | −5.2 |

| 5 | 180 | 70 | 20/20 | 4.75 | 80 | 9.15 | −11.7 |

| 6 | 280 | 82 | 20/30 | 10.5† | 98 | 3.06 | −10.5 |

Postoperative visual outcome reduced by development of cataract.

Significant regression of astigmatism occurred in this case.

FIGURE 2.

Case example: beveled FLAK with skewed arcs. Beveled FLAK was performed on the left eye of a patient after a zigzag configuration femtosecond laser-assisted keratoplasty for keratoconus. The beveled incisions are only faintly seen on slit-lamp photography (A), where the red dotted arcs are drawn just outside the incisions and the vertical white arrow indicates the orientation of the OCT scan. The arcuate incisions were skewed (not 180 degrees apart) to follow the skew in the steep hemi-meridians on preoperative topography (B). The arcuate FLAK incisions were 70% deep, 80 degrees wide, and centered at 70 and 270 degrees. Before FLAK, UCVA was 20/400 and BSCVA was 20/40. Refraction was −4.25/+ 6.0 × 90 degrees. Keratometric astigmatism measured 10.7 D with the steep axis at 78 degrees. At the 1-month postoperative visit, UCVA was 20/40, BSCVA was 20/20, refraction was −2.0/+0.25 × 80 degrees, and keratometric astigmatism had reduced to 2.3 D at 60 degrees on the postoperative topography (C). Cross-section drawing (D) and OCT (E) shows thickening of the corneal graft anterior to the beveled FLAK incision, and thinning of the graft posterior to the incision. The forward slide of Bowman layer on the anterior side of the wound relative to the posterior side was measured to be 128 μm on the OCT image. Epithelial thickness modulation smoothes over the Bowman layer shift, and there is no gaping or epithelial plug in the wound.

All the incisions opened easily using a Sinskey hook. Intraoperative keratoscopy showed undercorrection of astigmatism in all cases (ie, the short axis of the elliptical reflection was aligned along the steep preoperative meridian before and after opening the wound with the Sinskey hook). Therefore, we opened the wound fully using the Sinskey hook in all cases without attempting to titrate treatment by partial opening.

No wound gaping could be observed at the slit lamp postoperatively after beveled FLAK. The FLAK wounds were very faint and difficult to detect at the slit lamp. On the first postoperative day, all patients were comfortable and noted improved vision.

Patient Characteristics

The study included 6 eyes of 6 patients, 4 men and 2 women, who had a history of high astigmatism after PKP. Indications for PKP included keratoconus in 4 eyes, and corneal scarring secondary to microbial keratitis, and herpetic keratitis in 2 eyes. The mean interval between PKP and FLAK was 1.3 ± 0.45 years. Three PKPs were performed with conventional trephines and 3 were performed with a femtosecond laser. The diameters of the initial grafts were measured to be 8.0 mm for patients 1 to 5 and 7.8 mm for patient 6. The consecutive series of beveled FLAK procedures were performed between March 2009 and March 2010. Mean follow-up after FLAK was 4.5 months (range, 3–6 months).

Visual Outcomes

Mean Snellen UCVA improved from 20/348 (range, 20/200–20/400) preoperatively to 20/114 postoperatively (range, 20/50–20/400). Mean ± standard deviation UCVA expressed in LogMAR units improved from 1.24 ± 0.13 pre-operatively to 0.76 ± 0.38 postoperatively (P < 0.05). Mean Snellen BSCVA improved from 20/54 preoperatively (range, 20/30–20/200) to 20/42 postoperatively (range, 20/20–20/70; Table 1). Mean ± standard deviation LogMAR BSCVA improved from 0.43 ± 0.33 preoperatively to 0.27 ± 0.24 postoperatively (P = 0.22). The visual results after beveled FLAK were moderately reduced in 2 patients by the development of nuclear sclerosis cataract (Table 1). When these 2 patients were omitted from the analysis, mean LogMAR UCVA was 0.49 ± 0.1 postoperatively compared with 1.2 ± 0.17 preoperatively (P < 0.05), and BSCVA was 0.14 ± 0.19 postoperatively compared with 0.35 ± 0.21 preoperatively (P = 0.12). Mean Snellen UCVA preoperatively was 20/333 (range, 20/200–20/400) and postoperatively was 20/63 (range, 20/50–20/80). Mean Snellen BSCVA preoperatively was 20/49 (range, 20/80–20/25) and postoperatively was 20/ 30 (range, 20/50–20/20).

Refractive Outcomes

The mean magnitude of the preoperative keratometric astigmatism was 9.8 ± 2.9 D, and postoperatively it was 4.5 ± 3.2 D (P < 0.05; Figs. 3, 4). The mean postoperative manifest refractive cylinder was 2.88 ± 1.78 D, which was reduced from a mean of 6.71 ± 1.36 D preoperatively, a reduction of 3.83 D or 57% (P < 0.01). The mean preoperative and postoperative refractive spherical equivalents were −2.3 ± 2.5 D and −5.2 ± 5.2 D, respectively, but the myopic shift was not statistically significant (P = 0.22).

FIGURE 3.

Plot of the mean reduction in keratometric astigmatism magnitude after beveled FLAK.

FIGURE 4.

Doubled-angle plot of preoperative and postoperative keratometric astigmatism after beveled FLAK. WTR, with-the-rule; ATR, against-the-rule.

The preoperative topographic astigmatism had a cardinal component of 4.22 ± 7.62 D (predominantly with-the-rule) and an oblique component of 2.67 ± 6.0 D. The postoperative topographic astigmatism had a cardinal component of 2.81 ± 4.1 D and an oblique component of 0.16 ± 2.85 D (Fig. 3). There was a 33% reduction in cardinal astigmatism (P = 0.66) and a 94% reduction in oblique astigmatism (P = 0.34).

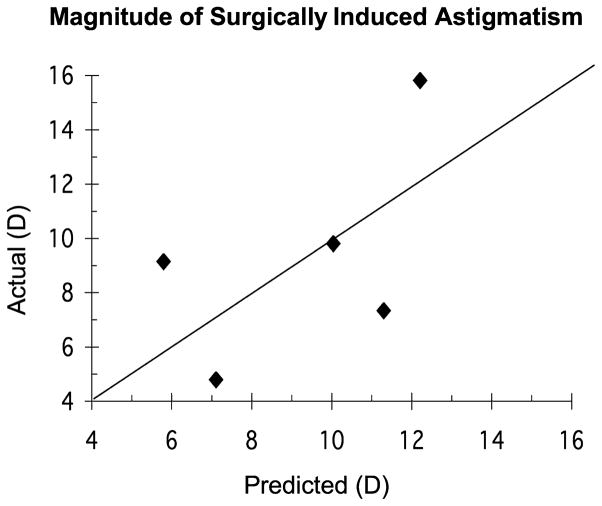

The magnitude of intended astigmatic correction was 9.82 ± 2.88 D and the SIAC was 8.33 ± 4.47 D, showing a general tendency for undercorrection. The residual astigmatism along the axis of intended correction was −1.73 ± 5.08 D, showing a trend toward undercorrection (P = 0.07; Figs. 4, 5). The SIAC orthogonal-to-intended correction was 1.40 ± 1.72 D, showing no significant systematic bias (P = 0.42) in the axis of achieved SIAC compared with the intended correction. The EA was −5.1 ± 5.5 degrees, again showing no significant systematic bias. The absolute EA was 5.9 ± 4.6 degrees.

FIGURE 5.

Doubled-angle plot showing the on-axis analysis of residual keratometric astigmatism after beveled FLAK. CW, clockwise; CCW, counter clockwise.

Incision Morphology

Fourier domain OCT clearly demonstrated the beveled FLAK incision morphology (Figs. 1, 2). On cross-sectional imaging of the FLAK incision sites, a mean forward shift of Bowman layer measuring 126 ± 38 μm (range, 103–191 μm) in magnitude was seen in all cases. The stromal FLAK incision and the graft–host junction were both characterized by lines of increased reflectivity, extending within the stroma from the subepithelial to the preendothelial layers. We measured the thickness of the cornea at the inner and outer edges of the beveled incision on OCT. Mean thickness at the inner edge of the incision measured 639 ± 36 μm, which was significantly greater than the outer edge thickness, which measured 591 ± 53 μm on average (P < 0.01).

Stability

At 3 months after beveled FLAK, in 5 of 6 patients, the magnitude of the keratometric cylinder remained stable within 1 D of the cylinder magnitude at postoperative month 1. Three of these patients had 6 months follow-up and remained stable to within 1 D up to this time point. No patient demonstrated significant progression of the effect of the astigmatic keratotomy. The magnitude of the astigmatism change between 1- and 3-month postoperative visits was 1.26 ± 1.1 D, showing no significant trend toward progression or regression (P = 0.36).

Regression of astigmatism occurred in 1 patient. In this patient (Patient 6; Table 1), a satisfactory reduction in keratometric astigmatism was initially observed, from 13.3 D preoperatively to 7.7 D at the 1-month postoperative visit. However, by postoperative 3 months, regression of astigmatism magnitude to 10.5 D occurred together with a corresponding decrease in visual acuity. No visible scar was observed. This patient subsequently underwent successful PRK to reduce this residual astigmatism.

Safety and Complications

No intraoperative or postoperative complications were associated with beveled FLAK. One patient experienced a 3-line decrease of BSCVA during the follow-up period, despite a reduction in keratometric astigmatism from 12 to 4.7 D, because of the development of nuclear sclerosis cataract. No other patient experienced a postoperative reduction in BSCVA. There were no cases of intraoperative microperforation, macro-perforation, allograft rejection, wound dehiscence, infectious keratitis, or overcorrection of astigmatism.

Development of Provisional Nomogram

To develop a nomogram, we need to use regression analysis to link incision parameters to surgical effect. For this purpose, we excluded the case (Patient 6; Table 1) with near complete regression. Linear regression analysis with the simplest model showed that the magnitude of SIAC was significantly correlated with the incision magnitude (P = 0.004). The regression equation is given below.

Model 1

| (1) |

This simple model yielded R2 = 0.89 and a root-mean-square residual error of 3.31 D.

However, previous literature has shown that the degree of achieved astigmatic correction was highly correlated with the magnitude of preoperative astigmatism, even when the incision parameters were held constant.10 Therefore, to develop an accurate nomogram, both the incision magnitude and preoperative astigmatism must be taken into account.

Model 2

| (2) |

The more complex model yielded R2 = 0.91 and a root-mean-square residual error of 3.01 D (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Plot of the actual versus predicted magnitude of surgically induced astigmatism.

A provisional nomogram was developed using model 2 and an intentional undercorrection of 10% (Table 2). The nomogram-generating equation is as follows:

| (3) |

Table 2.

The Nomogram of Beveled FLAK

| Corneal Astigmatism (D) | Arc Length (degrees) | Incision Depth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 4.00 | 60 | 63 |

| 5.00 | 65 | 65 |

| 6.00 | 65 | 68 |

| 7.00 | 70 | 68 |

| 8.00 | 70 | 70 |

| 9.00 | 75 | 69 |

| 10.00 | 75 | 70 |

| 11.00 | 80 | 69 |

| 12.00 | 80 | 70 |

| 13.00 | 85 | 69 |

| 14.00 | 85 | 69 |

| 15.00 | 85 | 70 |

| 16.00 | 85 | 70 |

Note that the nomogram equation is nonlinear—the incision magnitude increases more slowly at higher levels of preoperative keratometric astigmatism. For the nomogram, we chose progressive increases in arc lengths and depths for increasing magnitudes of astigmatism correction. The incision depths were chosen to stay within the range that was used in our case series. For the purpose of developing the nomogram, we assumed that all FLAK incisions would be paired and symmetric (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Astigmatic keratotomy involves placing 1 or 2 deep, curved corneal incisions perpendicular to the steep meridian of the corneal astigmatism. Studies in human and cadaver eyes have shown that the efficacy of astigmatic incisions is dependent on the length and depth of incisions,25,26 the diameter of the optical zone,26 and the age and sex of the patient.2,27 In this pilot study, we took advantage of the potential of the femtosecond laser software to create beveled incisions. This procedure resulted in a significant decrease in astigmatism and a significant improvement in visual acuity. However, it was not possible to accurately predict the outcome for each case. Like manual astigmatic keratotomy and vertical femtosecond incisions, the outcomes after beveled FLAK continue to be subject to both the inherent variability of the wound healing process and the variable tension present within the graft itself. Titrating the effect of the laser incision by partial opening using the Sinskey hook was not effective because, although intraoperative keratoscopy indicated under-correction in all cases, some cases later showed overcorrection. Hence, it is probable that in some cases progression of the incision effect occurred in the early postoperative period (before the 1-month postoperative visit).

In this study, we chose to use variable depth astigmatic keratotomy incisions as described by Akura et al,27,28 rather than using deep cuts at 90% depth and varying the arc length as in standard astigmatic keratotomy or limbal relaxing incisions. This was because our incisions were placed within the corneal graft border, close to the optical zone, unlike conventional astigmatic keratotomy incisions in the peripheral cornea. In this situation, deep cuts located within the graft rim may lead to wound destabilization and gaping. Also, if the length of the incision arc is too short, it can split the broad quadratic steep region of astigmatism into a narrow flat region bordered by 2 narrow steep regions, thereby increasing the likelihood of postoperative irregular astigmatism (Fig. 2).

The 54% reduction in astigmatism achieved using beveled incisions at depths ranging from 65% to 75% is similar to or better than those achieved by vertical incisions: the 55% reduction in keratometric astigmatism reported by Hoffart et al14 after FLAK, the 47% reduction achieved by Buzzonetti et al,11 and the 36% reduction reported by Kumar et al.23 This is notable given that the beveled incision depth ranged from 65% to 75%, whereas the vertical incisions were at 90% depth. Greater reductions up to 70% of astigmatism magnitude have been reported using standardized perpendicular manual incisions at 600 μm depth. However, at this depth, the risk of perforation requiring resuturing is high. The reductions in astigmatism achieved in this study are in the upper range of those achieved in other studies while simultaneously further reducing the risk of corneal perforation, destabilization, or gaping by using shallower incision depths. We were also able to treat cases of irregular astigmatism (including skewed axes and asymmetric bowtie astigmatism) to some limited extent by using asymmetric arc lengths and skewed incision placements.

We evaluated the predictability of astigmatic correction after beveled FLAK based on keratometric data from corneal topography, which showed undercorrection of astigmatism in most cases. Outcomes could potentially be further improved by modifications to the incision nomogram to increase the length or depth of incisions. Buzzonetti et al11 reported a systematic misalignment of keratometric refractive correction of 49 degrees using Intralase astigmatic keratotomy. We were able to reduce misalignment using reference marks, and the mean EA was only −5.1 ± 5.5 degrees.

In this study, Fourier domain OCT enabled detailed viewing of the wound architecture produced by beveled FLAK incisions. In agreement with our hypothesis, OCT imaging showed that after a beveled incision at 135 degrees, the anterior cornea does slide forward in relation to the posterior cornea, and the realigned stroma heals without wound gaping or the formation of an epithelial plug. The cornea on the inner edge of the beveled incision is released from radial tension and therefore slides forward under circumferential tension and becomes thickened. The forward movement and thickening of the cornea both served to flatten the incision axis and achieve astigmatic correction. The concomitant increase in anterior corneal curvature produced a reduction in astigmatism, which was effective in correcting both regular bowtie and skewed astigmatism, with a mean overall reduction in keratometric and subjective astigmatism of 56%.

We observed a trend toward a postoperative myopic shift after beveled FLAK, probably because of the increased central corneal curvature, which occurs because of the release of axial tension in the graft and a concomitant increase in the corneal vault. PRK is frequently required to further augment the effect of astigmatic keratotomy; hence, a small myopic shift may prove advantageous in allowing the use of myopic astigmatic PRK ablations. The myopic astigmatic PRK is preferable to hyperopic astigmatic PRK in eyes that have undergone PKP, because the smaller ablation zone can be safely confined within the graft without sacrificing any host tissue.

The conclusions that can be drawn from this small pilot study are limited by the small patient numbers and short follow-up time. The predictability of the astigmatic correction achievable using beveled FLAK remains only fair, and there are still frequent over- and undercorrections. However, the overall reduction in astigmatism achieved in this study seems to be comparable with or better than previous post-PKP astigmatic keratotomy results. Although the incisions we used were relatively shallow, we were nevertheless able to achieve large astigmatic corrections. A potential concern regarding beveled FLAK incisions is that the forward shift and increase in anterior curvature might be progressive over time. We saw no evidence of this during the postoperative follow-up period, and it may be that the lack of gaping or epithelial plug led to better wound healing and stabilization. Other studies have reported over-correction after femtosecond astigmatic keratotomy; however, we found regression to be a greater problem, with significant regression occurring in 1 patient.

Finally, we have developed a provisional nomogram (Table 2), which others are welcome to use. In developing our nomogram, we took note of published results that showed the effect of FLAK in the treatment of postkeratoplasty astigmatism to be related to the preoperative astigmatism magnitude.10 Wilkins et al10 concluded that the magnitude of the astigmatic correction achieved using arcuate keratotomy in postkeratoplasty astigmatism depends on the magnitude of the preoperative astigmatism, and therefore no role exists for nomograms in the treatment of postkeratoplasty astigmatism. We only partially agree with this philosophy. A linear nomogram may not be optimal in this situation; however, it is possible to develop a nonlinear nomogram that takes the effect of the preoperative astigmatism magnitude into account. Because the provisional nomogram is based on only 5 cases, there is a great need to refine the nomogram with a greater body of data. Therefore surgeons are invited to contact the corresponding author (DH) for the purpose of pooling results and building a better nomogram.

In conclusion, beveled FLAK incisions at varied depth are effective in the management of postkeratoplasty astigmatism while avoiding the problem of wound gape. Further studies will allow enhancement of incision nomograms and observation of long-term outcomes after beveled FLAK.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants RO1 EY017723 and RO1 EY018184; a grant from Optovue, Inc, and endowment funding from the Charles C. Manger III, MD Chair in Corneal Laser Surgery, and the Skilling Foundation; grants from the Irish College of Ophthalmologists (to C.C.) and Optovue, Inc (to M.T. and D.H.); speaker honorarium travel support, patent royalty, and stock options from Optovue, Inc (to D.H.); royalties from a patent on optical coherence tomography licensed to Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc (to D.H.).

References

- 1.Williams KA, Ash JK, Pararajasegaram P, et al. Long-term outcome after corneal transplantation. Visual result and patient perception of success. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:651–657. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price FW, Grene RB, Marks RG, et al. Astigmatism reduction clinical trial: a multicenter prospective evaluation of the predictability of arcuate keratotomy. Evaluation of surgical nomogram predictability. ARC-T Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:277–282. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100030031017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffart L, Touzeau O, Borderie V, et al. Mechanized astigmatic arcuate keratotomy with the Hanna arcitome for astigmatism after keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borderie VM, Touzeau O, Chastang PJ, et al. Surgical correction of postkeratoplasty astigmatism with the Hanna arcitome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)80127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel MR, Shapiro MB, Krachmer JH. Relaxing incisions with augmentation sutures for the correction of postkeratoplasty astigmatism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:441–447. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77768-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John ME, Martines E, Cvintal T, et al. Photorefractive keratectomy following penetrating keratoplasty. J Refract Corneal Surg. 1994;10(2 suppl):S206–S210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahar I, Kaiserman I, Mashor RS, et al. Femtosecond LASIK combined with astigmatic keratotomy for the correction of refractive errors after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41:242–249. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100303-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arenas E, Maglione A. Laser in situ keratomileusis for astigmatism and myopia after penetrating keratoplasty. J Refract Surg. 1997;13:27–32. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merlin U, Bordin P, Rimondi AP, et al. Factors that affect keratotomy depth. Refract Corneal Surg. 1991;7:356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins MR, Mehta JS, Larkin DF. Standardized arcuate keratotomy for postkeratoplasty astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzzonetti L, Petrocelli G, Laborante A, et al. Arcuate keratotomy for high postoperative keratoplasty astigmatism performed with the intralase femtosecond laser. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:709–714. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090707-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nubile M, Carpineto P, Lanzini M, et al. Femtosecond laser arcuate keratotomy for the correction of high astigmatism after keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahar I, Levinger E, Kaiserman I, et al. IntraLase-enabled astigmatic keratotomy for postkeratoplasty astigmatism. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:897–904. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffart L, Proust H, Matonti F, et al. Correction of postkeratoplasty astigmatism by femtosecond laser compared with mechanized astigmatic keratotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:779–787. 787.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kymionis GD, Yoo SH, Ide T, et al. Femtosecond-assisted astigmatic keratotomy for post-keratoplasty irregular astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiferman RA, Schultz GS, Nordquist RE, et al. Corneal wound healing and its pharmacologic modification after refractive keratectomy. In: Waring GO III, editor. Refractive Keratotomy for Myopia and Astigmatism. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1992. pp. 749–779. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjortdal JO, Ehlers N. Paired arcuate keratotomy for congenital and post-keratoplasty astigmatism. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:138–141. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holladay JT, Moran JR, Kezirian GM. Analysis of aggregate surgically induced refractive change, prediction error, and intraocular astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:61–79. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holladay JT, Dudeja DR, Koch DD. Evaluating and reporting astigmatism for individual and aggregate data. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eydelman MB, Drum B, Holladay J, et al. Standardized analyses of correction of astigmatism by laser systems that reshape the cornea. J Refract Surg. 2006;22:81–95. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20060101-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alpins N. Astigmatism analysis by the Alpins method. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:31–49. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00798-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang D, Stulting RD, Carr JD, et al. Multiple regression and vector analyses of laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia and astigmatism. J Refract Surg. 1999;15:538–549. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19990901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar NL, Kaiserman I, Shehadeh-Mashor R, et al. IntraLase-enabled astigmatic keratotomy for post-keratoplasty astigmatism: on-axis vector analysis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1228–1235. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpins NA. Vector analysis of astigmatism changes by flattening, steepening, and torque. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23:1503–1514. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akura J, Matsuura K, Hatta S, et al. Experimental study using pig eyes for realizing ideal astigmatic keratotomy. Cornea. 2001;20:325–328. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200104000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duffey RJ, Jain VN, Tchah H, et al. Paired arcuate keratotomy. A surgical approach to mixed and myopic astigmatism. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140286043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akura J, Matsuura K, Hatta S, et al. Clinical application of full-arc, depth-dependent, astigmatic keratotomy. Cornea. 2001;20:839–843. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akura J, Matsuura K, Hatta S, et al. A new concept for the correction of astigmatism: full-arc, depth-dependent astigmatic keratotomy. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]