Abstract

Norsolorinic acid, isolated from the Aspergillus nidulans, was investigated for its anti-proliferative activity in human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells. To identity the anticancer mechanism of norsolorinic acid, we assayed its effect on apoptosis, cell cycle distribution, and levels of p53, p21/WAF1, Fas/APO-1 receptor, and Fas ligand. The results showed that norsolorinic acid induced apoptosis of MCF-7 cells without mediation of p53 and p21/WAF1. We suggest that Fas/Fas ligand apoptotic system is the main pathway of norsolorinic acid-mediated apoptosis of MCF-7 cells. Our study reports here for the first time that the activity of the Fas/Fas ligand apoptotic system may participate in the anti-proliferative activity of norsolorinic acid in MCF-7 cells.

Keywords: norsolorinic acid, breast cancer, p53, Fas/APO-1, Fas ligand, apoptosis

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies in women, and is the leading cause of death worldwide for women between the ages of 40 and 55 [1,2]. Increasing evidence suggests that breast cancer might result from interactions between genetic elements, various possible environmental factors, and also the difference in ethnicity [1,3]. This pathology is currently controlled through surgery and/or radiotherapy, and is frequently supported by adjuvant chemo- or hormonotherapies. Unfortunately, these classical treatments are hampered by unwanted side effects and, most importantly, the development of tumor resistance. There is no doubt an urgent need for novel and effective therapies against breast cancer [4].

Apoptosis plays an important role in homeostasis and development of the tissue in organism [5]. Imbalance between cell proliferation and apoptotic cell death will result in serious disease such as cancer. Many studies have demonstrated that cancer treatment by chemotherapy and γ-irradiation kill target cells primarily by the induction of apoptosis [5,6]. Tumor suppressor gene p53 is activated in response to various genotoxic stresses, resulting in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [7–9]. Functional p53 protein has been shown that it is a transcription factor with sequence-specific DNA binding activity [10]. The induction of p21/WAF1 causes subsequent arrest in the G0/G1 or G2/M phase of the cell cycle by binding of cyclin-cdk complex [8–10]. How p53 triggers apoptosis is yet to be elucidated, but it seems to involve both transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms [11–13]. Several previous publications have reported that anti-cancer drugs may induce apoptosis via the Fas/FasL system [14–17]. Fas is a cell surface receptor comprising a type integral membrane protein that expresses a cytoplasmic death domain and belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily [11,18]. Activation of Fas by its ligand (FasL) results in the oligomerization of its intracellular death domain and the recruitment of the intracellular adaptator FADD (Fas-associated death domain). Once bound, FADD is able to activate procaspases-8 and -10 in a death inducing signaling complex. In turn, caspases-8 and -10 activate downstream caspases, resulting in apoptotic cell death [19,20].

Norsolorinic acid has been reported to exhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO)-inhibitory action [21]. This study is the first to determine the cell proliferation inhibition activity of norsolorinic acid and examine its effect on cell cycle distribution and apoptosis in human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells. To establish the pro-apoptotic mechanism of norsolorinic acid, we assayed the levels of p53, p21/WAF1, Fas/APO-1 receptor, and Fas ligand (FasL), which are strongly associated with the signal transduction of apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Fermentation and purification

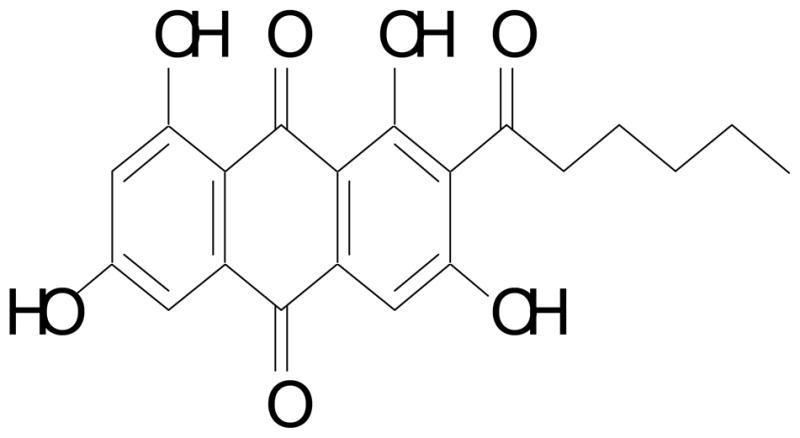

Norsolorinic acid (Fig.1) was isolated from the Aspergillus nidulans. Briefly, Aspergillus nidulans STCE BRE2 mutant strain was cultivated in 20 YAG plates (22.5 106 spores/15 cm plate) at 37 °C. After 5 days, agar was chopped and the chopped materials were extracted with 1L of MeOH followed by 1L of the 1:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH each with 1h sonication. The extract was evaporated in vacuo to yield a residue, which was suspended in H2O (500 ml), and this was then partitioned with ethyl acetate (500 ml×2). The combined ethyl acetate layer afforded maroon syrup (114.4 mg), which was applied to a Si gel column (Merck 230–400 mesh, ASTM, 20×100 mm) and eluted with CHCl3-MeOH mixtures of increasing polarity (fraction A, 1:0, 300 ml; fraction B, 19:1, 300 ml; fraction C, 9:1, 300 ml; fraction D, 7:3, 300 ml). The solvent of fraction A, containing norsolorinic acid, was evaporated in vacuo and re-suspended in CHCl3. Norsolorinic acid, which do not dissolve in CHCl3, was collected by filtration. Enriched norsolorinic acid was further purified by preparative HPLC [Phenomenex Luna 5 m C18 (2), 250×10 mm] with a flow rate of 5.0 ml/min and measured by a UV detector at 254 nm. The gradient system was MeCN (solvent B) in 5 % MeCN/H2O (solvent A) both containing 0.05 % TFA: 70 to 100 % B from 0 to 10 min, 100 % B from 10 to 15 min, 100 to 70% B from 15 to 16 min, and re-equilibration with 70 % B from 16 to 23 min. Norsolorinic acid (14.8 mg) was eluted at 11.8 min. Norsolorinic acid: reddish needles, IR (ZnSe) cm−1 3437, 1626, 1594, 1469, 1409, 1344, 1305, 1248, 1173, 1096, 1016; ESI-MS m/z (negative mode): 369 [M-H]− (100); 1H and 13C NMR data (DMSO-d6) in good agreement with published data [21]. The stock solution of norsolorinic acid was prepared at a concentration of 2 mg/ml of DMSO. It was then stored at −20°C until use. For all experiments, the final concentrations of the test compound were prepared by diluting the stock with DMEM. Control cultures received the carrier solvent (0.1% DMSO).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure norsolorinic acid isolated from the Aspergillus nidulans.

Reagents and materials

Fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin G, streptomycin, amphotericin B and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were obtained from GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ribonuclease (RNase), and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). XTT and p53 pan ELISA kits were obtained from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). Nucleosome ELISA, WAF1 ELISA, Fas Ligand, Fas/APO-1 ELISA, and caspase-8 assay kits, and caspase-8 inhibitor, benzyloxy-carbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (Z-IETD-FMK) were purchased from Calbiochem (Cambridge, MA). Anti-Fas Ab (ZB4) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY).

Cell culture

Breast cancer cell line MCF-7 was obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Normal mammary epithelial cell H184B5F5/M10 was purchased from Bioresource Collection and Research Center (Hsinchu, Taiwan). MCF-7 and H184B5F5/M10 cells were maintained in monolayer culture at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 5 μg/ml insulin, 100 units/ml of penicillin G, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml of amphotericin B.

Cell proliferation assay

Inhibition of cell proliferation by norsolorinic acid was measured by XTT {sodium 3′-[1-(phenylamino-carbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene-sulfonic acid hydrate} assay. Briefly, cells were plated in 96-well culture plates (1×104 cells/well). After 24 h incubation, the cells were treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and various concentrations of norsolorinic acid for 48 h. Fifty μl of XTT test solution, which was prepared by mixing 5 ml of XTT-labeling reagent with 100 μl of electron coupling reagent, was then added to each well. After 6 h incubation, the absorbance was measured on an ELISA reader (Multiskan EX; Labsystems. Thermo Electron Corporation, Milford, USA.) at a test wavelength of 492 nm and a reference wavelength of 690 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

To determine cell cycle distribution, 5×105 cells were plated in 60-mm dishes and treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and various concentrations of norsolorinic acid for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were collected by trypsinization, fixed in 70% ethanol, washed in PBS, re-suspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 1 mg/ml RNase and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide, incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, and analyzed by EPICS flow cytometer. The data were analyzed using the Multicycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA).

Measurement of apoptosis by ELISA

The induction of apoptosis by norsolorinic acid was assayed using the Nucleosome ELISA kit. This kit uses a photometric enzyme immunoassay that quantitatively determines the formation of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (mono- and oligonucleosomes) after apoptotic cell death. MCF-7 cells were treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM) for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. The samples of cell lysate were placed in 96 well (1×106 per well) microtiter plates. The induction of apoptosis was evaluated by assessing the enrichment of nucleosome in cytoplasm, and determined exactly as described in the manufacturer’s protocol [22,23].

Assaying the levels of p53, p21, Fas/APO-1 and Fas ligand (mFasL and sFasL)

p53 pan ELISA, WAF1 ELISA, Fas/APO-1 ELISA and Fas Ligand ELISA kits were used to detect p53, p21, Fas/APO-1 receptor and soluble (sFasL)/membrane-bound Fas ligand (mFasL). Briefly, MCF-7 cells were treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM) for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. The samples of cell lysate were placed in 96 well (1×106 per well) microtiter plates that coated with monoclonal detective antibodies, and incubated for 1 h (Fas/APO-1), 2 h (p53 or p21/WAF1) or 3 h (FasL) at room temperature. It was necessary to determine the soluble Fas ligand in cell culture supernatant by using Fas Ligand ELISA kit. After removing the unbound material by washing with washing buffer (50 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20), the detector antibody that is bound by horseradish peroxidase, conjugated streptavidin, was added to bind to the antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase catalyzed the conversion of a chromogenic substrate (tetramethylbenzidine) to a colored solution with color intensity proportional to the amount of protein present in the sample. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm, and concentrations of p53, p21/WAF1, Fas/APO-1, and FasL were determined by interpolating from standard curves obtained with known concentrations of standard proteins [24,25].

Assay for caspase-8 activity

The assay is based on the ability of the active enzyme to cleave the chromophore from the enzyme substrate, Ac-IETD-pNA. The cell lysates were incubated with peptide substrate in assay buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.4) for 3 h at 37°C. The release of p-nitroaniline was monitored at 405 nm. Results are represented as the percent change of the activity compared to the untreated control [24,25].

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical comparisons of the results were made using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant differences (P<0.05) between the means of control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells were analyzed by Dunnett’s test.

Results

Effect of norsolorinic acid on MCF-7 cell proliferation

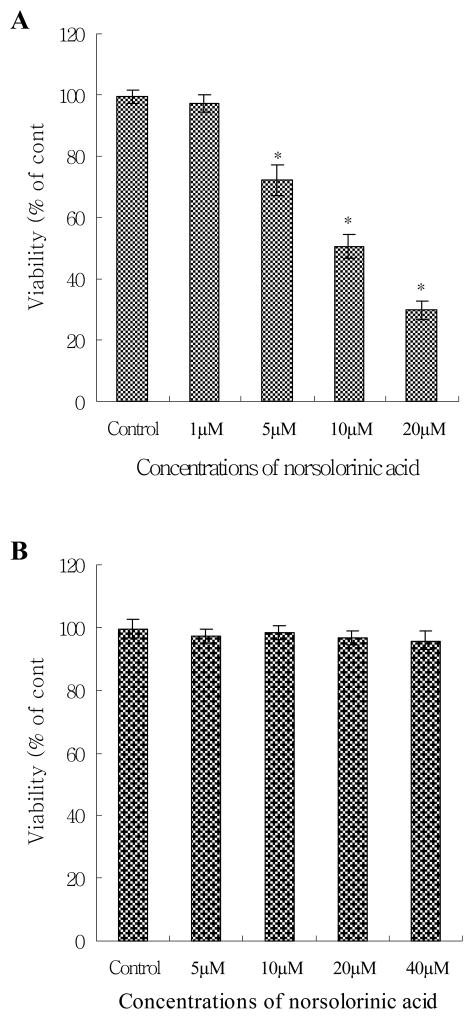

We first tested the anti-proliferative effect of norsolorinic acid in the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. As shown in Fig. 2A, the proliferative inhibitory effect of norsolorinic acid was observed in a dose-dependent manner. At 48 h, the maximal effect on proliferation inhibition was observed with 20 μM norsolorinic acid, which inhibited proliferation in 70.2% of MCF-7 cells. The IC50 value was 12.7 μM. To examine the selection of norsolorinic acid-mediated cell proliferation inhibition, we also evaluated the effect of norsolorinic acid in normal mammary epithelial cell line, H184B5F5/M10. The results showed that treatment of H184B5F5/M10 cells with norsolorinic acid failed to affect the cell proliferation at any of the examined concentrations (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The effects of norsolorinic acid on cell proliferative inhibition in MCF-7 and H184B5F5/M10 cells. (A) Cell proliferative inhibition effect of norsolorinic acid in MCF-7. (B) Cell proliferative inhibition effect of norsolorinic acid in H184B5F5/M10. Adherent cells plated in 96-well plates (104 cells/well) were incubated with different concentrations of norsolorinic acid at 48 h. Cell proliferation was determined by XTT assay. Results are expressed as percent cell proliferation relative to the proliferation of control. Each value is the mean ± S.D. of three determinations. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells, as analyzed by Dunnett’s test (p<0.05).

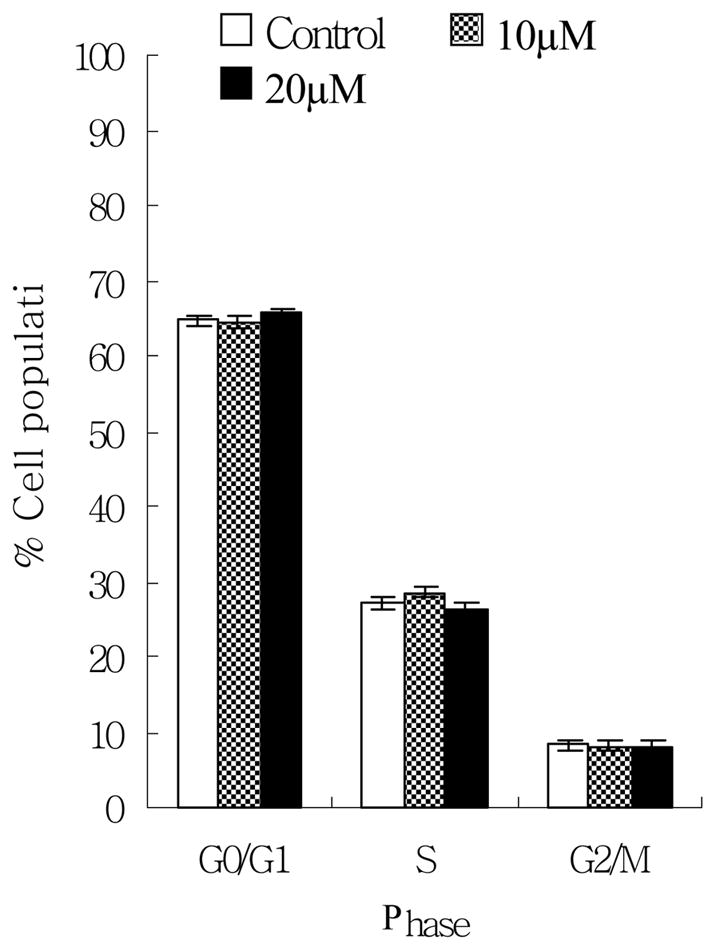

Norsolorinic acid induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells, without affecting the cell cycle distribution

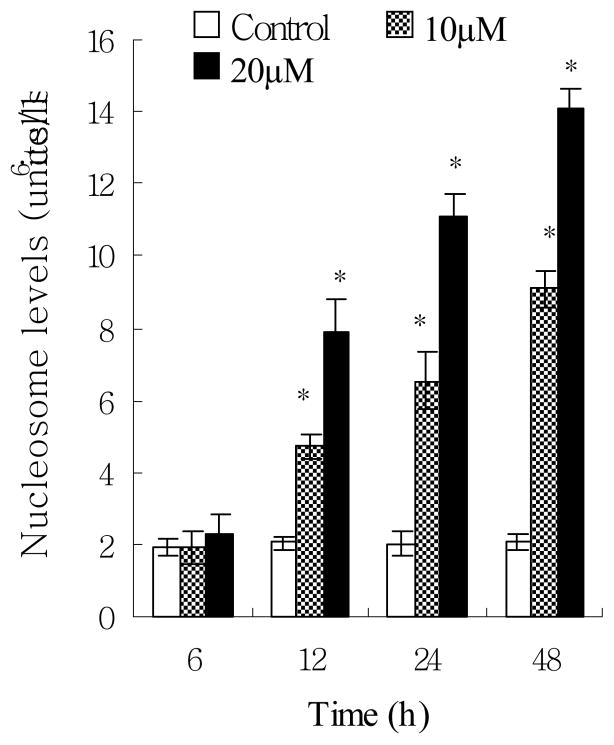

To clarify the mechanism of anti-proliferative effect, EPICS flow cytometer and apoptotic ELISA kits were used to analyze cell cycle distribution and apoptosis respectively. In cell cycle distribution, our results did not show any significant change between the control group and the norsolorinic acid-treated group for up to 20 μM at 24 h (Fig. 3). By using Nucleosome ELISA kit, we demonstrated that norsolorinic acid induced apoptosis of MCF-7 cells in dose-dependent and time-dependent manners (Fig. 4). In contrast to the controls, when cells were treated with norsolorinic acid, the number of cells undergoing apoptosis increased from about 4.4 fold at 10 μM norsolorinic acid to 6.8 fold at 20 μM norsolorinic acid at 48 h.

Fig. 3.

The effects of norsolorinic acid on cell cycle distribution in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells following treatment with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM) for 24 h were fixed and stained with propidium iodide, and cell cycle distribution was then analyzed by flow cytometry. The data indicate the percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle (P>0.05). The results represent the mean values and standard deviations from three individual experiments.

Fig. 4.

Induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 cells by norsolorinic acid. MCF-7 cells were cultured with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM) for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. Cells were harvested and lysed with lysis buffer. Cell lysates containing cytoplasmic oligonucleosomes of apoptotic cells were analyzed by means of Nucleosome ELISA. Each value is the mean ± S.D. of three determinations. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells, as analyzed by Dunnett’s test (P<0.05).

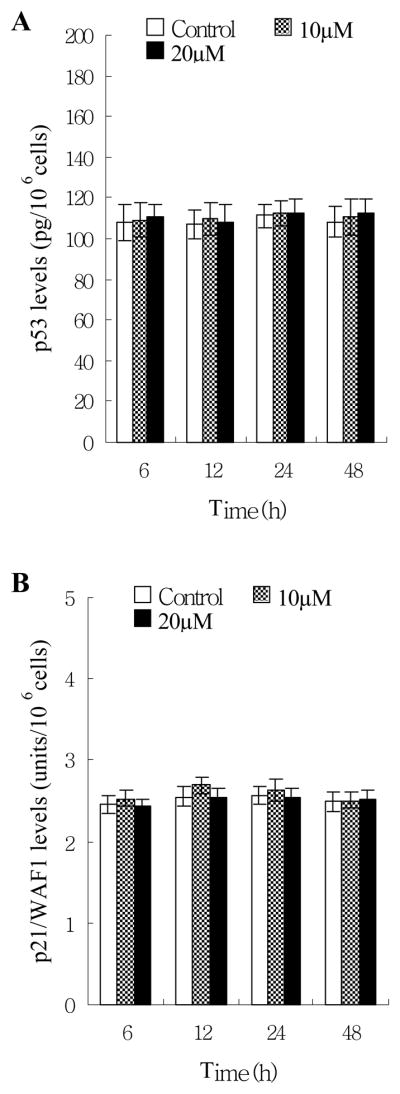

p53 and p21/WAF1 were not involved on norsolorinic acid-mediated cell proliferation inhibition

To understand the molecular mechanism of how norsolorinic acid works to induce apoptosis, the p53 pan ELISA and WAF1 ELISA kits were used to analyze p53 and its downstream molecule p21/WAF1. Treatment of norsolorinic acid for up to 20 μM at 48 h did not affect the protein expression of p53 and p21/WAF1 (Fig. 5). Therefore, norsolorinic acid-induced apoptosis might not be regulated by p53 and p21/WAF1.

Fig. 5.

Effects of norsolorinic acid on protein expression of p53 and p21/WAF1. (A) The level of p53 protein in MCF-7 cells; (B) the level of p21/WAF1 in MCF-7 cells. Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells were treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM). p53 and p21/WAF1 levels were determined by p53 pan ELISA and WAF1 ELISA kit, respectively. The detailed protocol is described in “Materials and Methods”. Each value is the mean ± S.D. of three determinations.

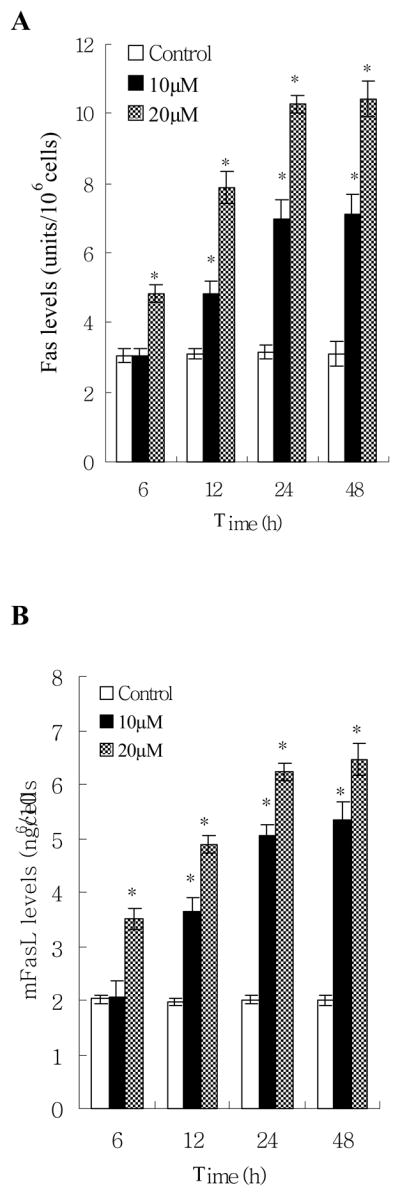

Fas/FasL apoptotic system might be a possible pathway of norsolorinic acid-mediated apoptosis

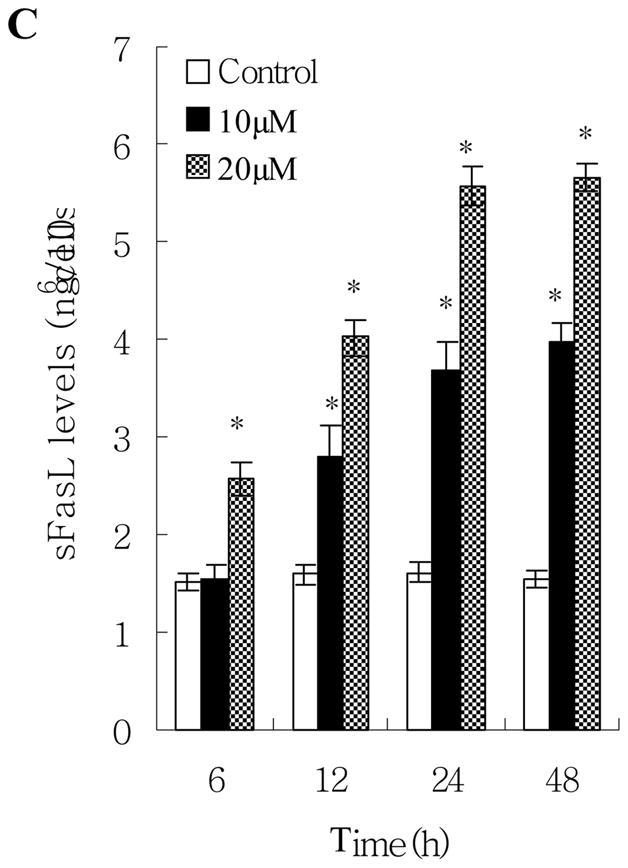

By using Fas/APO-1 ELISA and Fas Ligand ELISA kits, we found that norsolorinic acid increased expression of Fas/APO-1 receptor and soluble/membrane-bound Fas ligand in MCF-7 cells as early as 6 h post treatment in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6). The maximum effect was observed after 48 h of treatment. The time relationship between the expression of Fas/FasL at 6 h of treatment and the occurrence of apoptosis at 12 h of treatment could support the idea that the Fas/FasL system might mediate norsolorinic acid-induced apoptosis of MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 6.

Fas/FasL apoptotic system was involved in norsolorinic acid-mediated apoptosis. MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) and norsolorinic acid (10 and 20 μM) for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. (A) The level of Fas/APO-1 receptor in MCF-7 cells; (B) The amount of mFasL in MCF-7 cells; (C) The amount of sFasL in MCF-7 cells. Each value is the mean ± S.D. of three determinations. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells, as analyzed by Dunnett’s test (P<0.05).

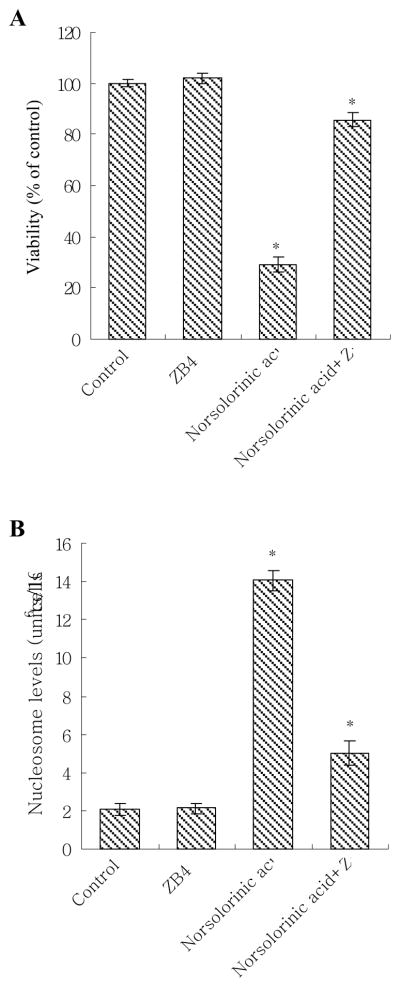

When MCF-7 cells were pre-treated with an antagonistic anti-Fas antibody, ZB4, the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of norsolorinic acid were effectively prevented. At 20 μM of norsolorinic acid, cell proliferation inhibition decreased from 70.2% to 19.2% (Fig. 7A). Compared to the control, the oligonucleosome DNA fragmentation of apoptosis induced by 20 μM of norsolorinic acid decreased from about 6.8 fold to 2.4 fold at 48 h in ZB4 pretreated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effect of antagonistic anti-Fas antibody (ZB4) on norsolorinic acid in MCF-7 cells. (A) The anti-proliferative and (B) pro-apoptotic effect of norsolorinic acid was decreased by Fas antagonist ZB4. For blocking experiments, cells were pre-incubated with 250 ng/ml ZB4 for 1 h and then treated with 20 μM of norsolorinic acid for 48 h. Cell viability and apoptosis induction were examined by XTT and Nucleosome ELISA kit. The data shown are the mean ± S.D. of three determinations. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells, as analyzed by Dunnett’s test (P<0.05).

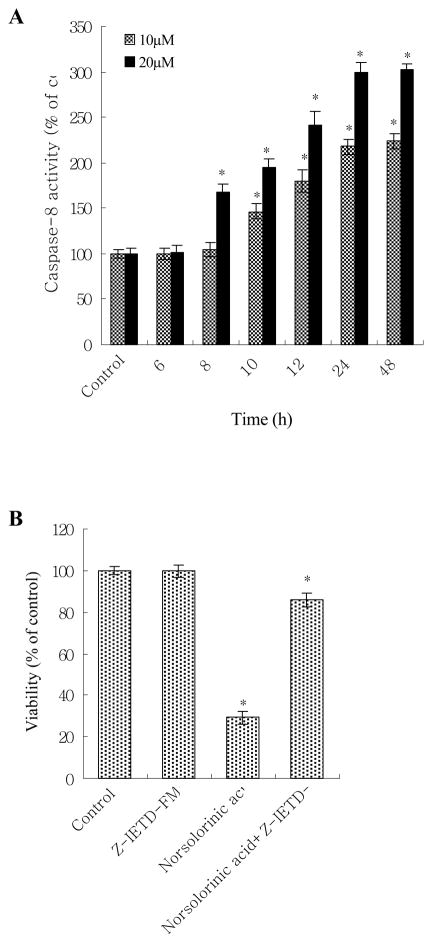

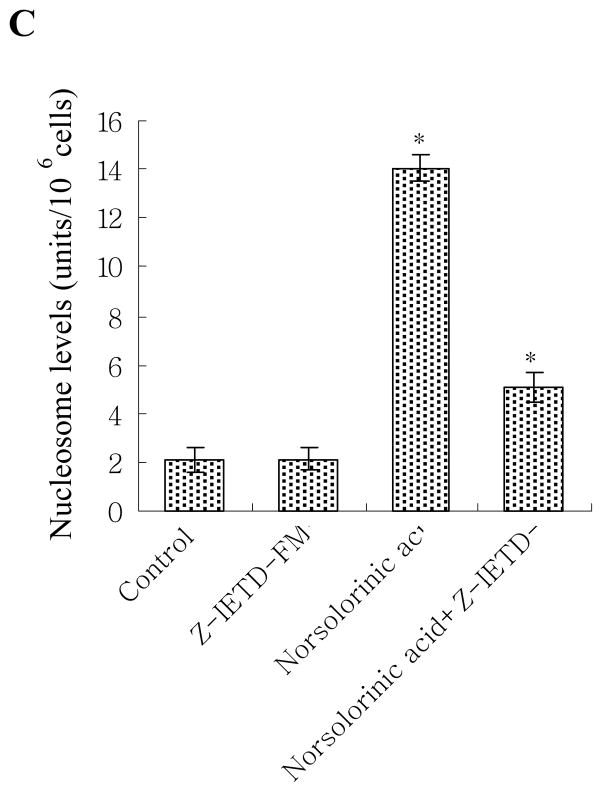

We next measured the downstream caspase of Fas/FasL system. The results showed that caspase-8 activity increased at 8 h, and reached maximum induction at 48 h in 20 μM norsolorinic acid treated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 8A). The activation of caspase-8 (at 8 h) was before the production of oligonucleosome DNA fragmentation (at 12 h) showing caspase-8 activation was required in norsolorinic acid-induced apoptosis. To further provide this hypothesis, we assessed that the effect caspase-8 inhibitor (Z-IETD-FMK) on the norsolorinic acid-mediated anti-proliferation and apoptosis. Our results showed that the anti-proliferative activity and induction of apoptosis by norsolorinic acid were significantly decreased in the presence of inhibitor of caspase-8 (Z-IETD-FMK) (Figs. 8B and C).

Fig. 8.

(A) The activation of caspase-8 in MCF-7 cells by norsolorinic acid; (B) Effect of caspase-8 inhibitor on norsolorinic acid-mediated anti-proliferation; (C) Effect of caspase-8 inhibitor on norsolorinic acid-induced apoptosis. MCF-7 cells were incubated with various concentrations of norsolorinic acid for the indicated times. For blocking experiments, cells were pre-incubated with Z-IETD-FMK (10 μM) for 1 h before the addition of 20 μM norsolorinic acid. After 48 h of treatment, cell viability and induction of apoptosis were measured by XTT and Nucleosome ELISA kit. Each value is the mean ± S.D. of three determinations. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between control and norsolorinic acid-treated cells, as analyzed by Dunnett’s test (P<0.05).

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common neoplasm in human in both developed and developing countries [26,27]. In our study, we have found that norsolorinic acid effectively inhibits tumor cell growth in vitro, concomitantwith induction of apoptosis. Furthermore, because norsolorinic acid does not exhibit any significant toxicity in normal mammary epithelial cell H184B5F5/M10, this suggests that norsolorinic acid possesses selectivity between normal and cancer cells. This selection of norsolorinic acid to cancer cells may be related to the different genomic stability between cancer and normal cells [28,29].

Normal p53 gene is well known to play a crucial role in inducing apoptosis and acting as cell cycle checkpoints in human and murine cells following DNA damage [8]. p21/WAF1 protein blocks the activities of various cyclin-dependent kinase [30–32], and inhibits the phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (RB) protein, thereby preventing the G1-S phase transition [31,33]. Previous studies have shown that p21/WAF1 is transcriptionally regulated by p53-dependent and -independent pathways [34–36]. Our results did not show any significant change between the control group and the norsolorinic acid-treated group for up to 20 μM at 48 h when assayed for protein expression of p53 and p21/WAF1 (Fig. 5), so it is clear that p53 and p21/WAF1 may not participate in norsolorinic acid-inhibited proliferation in MCF-7 cells.

Fas/FasL system is a key signaling transduction pathway of apoptosis in cells and tissues [18]. Ligation of Fas by agonistic antibody or its mature ligand induces receptor oligomerization and formation of death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), followed by activation of caspase-8, then further activating a series of caspase cascades resulting in cell apoptotic death [18,37]. Although p53 has been demonstrated to modulate the expression of Fas, but other factors also clearly regulate the transcriptional activity of the Fas gene because other studies have shown abundant Fas protein expression in the absence of wild type p53 protein expression [38,39]. FasL is a Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) related type II membrane protein [40]. Cleavage of membrane-bound Fas ligand (mFasL) by a metalloprotease-like enzyme results in the formation of soluble Fas ligand (sFasL) [41]. Defects in the Fas/FasL apoptotic signaling pathway provide a survival advantage to cancer cells and may be implicated in tumorigenesis. Indeed, expression of FasL by breast cancer cells is associated with the loss of Fas expression, thus eliminating the possibility of self-induced apoptosis and is involved in drug resistance [42,43] and MCF-7 cell line, which has been described to be Fas-sensitive [44]. Reimer et al. have reported that the selection process leading to highly aggressive breast tumor variants might be enhanced by FasL-mediated tumor fratricide, eventually a possible target for novel therapeutic strategies [45]. Our study indicated that Fas ligands mFasL and sFasL increased in norsolorinic acid-treated MCF-7 cells. Moreover, levels of Fas/APO-1 and the activity of caspase-8 were simultaneously enhanced in FasL-upregulating MCF-7 cells. Furthermore, when the Fas/Fas ligand system was blocked by ZB4, a decrease in both cell proliferative inhibition and the pro-apoptotic effect of norsolorinic acid was noted. Similarly, cell proliferative inhibition and apoptotic induction of norsolorinic acid decreased in MCF-7 cells treated with caspase-8 inhibitor. These findings are novel to show that the Fas/FasL system plays an important role in norsolorinic acid-mediated MCF-7 cellular apoptosis.

Overall, our results have demonstrated that norsolorinic acid inhibits cell proliferation in a p53-independent manner, and that enhanced Fas-mediated apoptosis may present interesting therapeutic prospects for the compound in the treatment of human breast cancer. As down-regulation of Fas is associated with a poor prognosis in breast cancer [4,45], it remains to be determined whether norsolorinic acid treatment will prove useful in the fight against advanced breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (GM075857) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-06-010-11-CDD).

References

- 1.Baselga J, Mendelsohn J. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for therapy in breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;29:127–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00666188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo PL, Chen CY, Hsu YL. Isoobtusilactone A induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through reactive oxygen species/apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 signaling pathway in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7406–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao WC, Young KC, Lin SL, Lin PW. Estrogen receptor-alpha polymorphism in a Taiwanese clinical breast cancer population: a case-control study. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R180–R186. doi: 10.1186/bcr770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopin V, Toillon RA, Jouy N, Le Bourhis X. p21(WAF1/CIP1) is dispensable for G1 arrest, but indispensable for apoptosis induced by sodium butyrate in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:21–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evan GI, Vousden KH. Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer. Nature. 2001;411:342–348. doi: 10.1038/35077213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemp CJ, Sun S, Gurley KE. p53 induction and apoptosis in response to radio- and chemotherapy in vivo is tumor-type-dependent. Cancer Res. 2001;61:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May P, May E. Twenty years of p53 research: structural and functional aspects of the p53 protein. Oncogene. 1999;18:7621–7636. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. p53: good cop/bad cop. Cell. 2002;110:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian H, Wang T, Naumovski L, Lopez CD, Brachmann PK. Groups of p53 target genes involved in specific p53 downstream effects cluster into different classes of DNA binding sites. Oncogene. 2002;21:7901–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopin V, Toillon RA, Jouy N, Le Bourhis X. Sodium butyrate induces P53-independent, Fas-mediated apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:79–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh MS, Fornace AJ., Jr Role of p53 family members in apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:171–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200002)182:2<171::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sionov RV, Haupt Y. The cellular response to p53: the decision between life and death. Oncogene. 1999;18:6145–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glick RD, Swendeman SL, Coffey DC, Rifkind RA, Marks PA, Richon VM, La Quaglia MP. Hybrid polar histone deacetylase inhibitor induces apoptosis and CD95/CD95 ligand expression in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4392–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamsteeg M, Rutherford T, Sapi E, Hanczaruk B, Shahabi S, Flick M, Brown D, Mor G. Phenoxodiol--an isoflavone analog--induces apoptosis in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:2611–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syed V, Ho SM. Progesterone-induced apoptosis in immortalized normal and malignant human ovarian surface epithelial cells involves enhanced expression of FasL. Oncogene. 2003;22:6883–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu W, Israel K, Liao QY, Aldaz CM, Sanders BG, Kline K. Vitamin E succinate (VES) induces Fas sensitivity in human breast cancer cells: role for Mr 43,000 Fas in VES-triggered apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:953–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–56. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juo P, Kuo CJ, Yuan J, Blenis J. Essential requirement for caspase-8/FLICE in the initiation of the Fas-induced apoptotic cascade. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1001–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vergote D, Cren-Olive C, Chopin V, Toillon RA, Rolando C, Hondermarck H, Le Bourhis X. (−)-Epigallocatechin (EGC) of green tea induces apoptosis of human breast cancer cells but not of their normal counterparts. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;76:195–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1020833410523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamazaki M, Satoh Y, Maebayashi Y, Horie Y. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors from a fungus, Emericella navahoensis. Chem Pharm Bull. 1988;36:670–675. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Lin LT, Lin CC. Asiatic acid, a triterpene, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in human breast cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:333–44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgame P, Varadhachary AS, Primiano LL, Fincke JE, Muller S, Monestier M. An ELISA for detection of apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:680–1. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Lin CC. Acacetin inhibits the proliferation of Hep G2 by blocking cell cycle progression and inducing apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:823–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo PL, Hsu YL, Chang CH, Lin CC. The mechanism of ellipticine-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human breast MCF-7 cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2005;223:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houssami N, Cuzick J, Dixon JM. The prevention, detection, and management of breast cancer. Med J Aust. 2006;184:230–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singletary SE, Connolly JL. Breast cancer staging: working with the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:37–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CH, Craise LM. Development of human epithelial cell systems for radiation risk assessment. Adv Space Res. 1994;14:115–20. doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefford CE, Irminger-Finger I. Mechanisms of chromosome instability in cancers. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu Y, Turck CW, Morgan DO. Inhibition of CDK2 activity in vivo by an associated 20K regulatory subunit. Nature. 1993;366:707–10. doi: 10.1038/366707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature. 1993;366:701–4. doi: 10.1038/366701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulic V, Kaufmann WK, Wilson SJ, Tlsty TD, Lees E, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Reed SI. p53-dependent inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase activities in human fibroblasts during radiation-induced G1 arrest. Cell. 1994;76:1013–23. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macleod KF, Sherry N, Hannon G, Beach D, Tokino T, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Jacks T. p53-dependent and independent expression of p21 during cell growth, differentiation, and DNA damage. Genes Dev. 1995;9:935–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michieli P, Chedid M, Lin D, Pierce JH, Mercer E, Givol D. Induction of Waf1/CIP1 by a p53-independent pathway. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahidhara RS, Queiroz De Oliveira PE, Kohout J, Beer DG, Lin J, Watkins SC, Robbins PD, Hughes SJ. Altered trafficking of Fas and subsequent resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis occurs by a wild-type p53 independent mechanism in esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Res. 2005;123:302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou M, Gu L, Yeager AM, Findley HW. Sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with a mutant p53 phenotype and absence of Bcl-2 expression. Leukemia. 1998;12:1756–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayagaki N, Kawasaki A, Ebata T, Ohmoto H, Ikeda S, Inoue S, Yoshino K, Okumura K, Yagita H. Metalloproteinase-mediated release of human Fas ligand. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1777–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landowski TH, Gleason-Guzman MC, Dalton WS. Selection for drug resistance results in resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 1997;89:1854–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toillon RA, Descamps S, Adriaenssens E, Ricort JM, Bernard D, Boilly B, Le Bourhis X. Normal breast epithelial cells induce apoptosis of breast cancer cells via Fas signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:31–43. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson S, Tu S, Oyer R, Anderson SM, Johnson GL. Epidermal growth factor protects epithelial cells against Fas-induced apoptosis. Requirement for Akt activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17612–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reimer T, Herrnring C, Koczan D, Richter D, Gerber B, Kabelitz D, Friese K, Thiesen HJ. FasL:Fas ratio--a prognostic factor in breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2000;15:822–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]