This study established long-term self-renewing prostate cancer stem cell (PCSC) lines from the different stages of transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) progression by application of the neurosphere assay. It was found that TRAMP-derived PCSCs represent a novel and valuable preclinical model for elucidating the pathogenetic mechanisms leading to prostate adenocarcinoma and for the identification of molecular mediators to be pursued as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Cancer, Cancer stem cells, Gene expression, Neoplastic stem cell biology

Abstract

The relevant social and economic impact of prostate adenocarcinoma, one of the leading causes of death in men, urges critical improvements in knowledge of the pathogenesis and cure of this disease. These can also be achieved by implementing in vitro and in vivo preclinical models by taking advantage of prostate cancer stem cells (PCSCs). The best-characterized mouse model of prostate cancer is the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. TRAMP mice develop a progressive lesion called prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia that evolves into adenocarcinoma (AD) between 24 and 30 weeks of age. ADs often metastasize to lymph nodes, lung, bones, and kidneys. Eventually, approximately 5% of the mice develop an androgen-independent neuroendocrine adenocarcinoma. Here we report the establishment of long-term self-renewing PCSC lines from the different stages of TRAMP progression by application of the neurosphere assay. Stage-specific prostate cell lines were endowed with the critical features expected from malignant bona fide cancer stem cells, namely, self-renewal, multipotency, and tumorigenicity. Notably, transcriptome analysis of stage-specific PCSCs resulted in the generation of well-defined, meaningful gene signatures, which identify distinct stages of human tumor progression. As such, TRAMP-derived PCSCs represent a novel and valuable preclinical model for elucidating the pathogenetic mechanisms leading to prostate adenocarcinoma and for the identification of molecular mediators to be pursued as therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the most developed countries [1]. PC is a heterogeneous tumor, characterized by a slow growth rate and an overall long natural history in comparison with other solid tumors, with a wide spectrum of biological behaviors that range from indolent to highly malignant stages [2].

The most likely pathological precursor lesion of PC is the histopathological alteration known as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). PIN can be described as low-grade or high-grade (HG) [3]. HG PIN is currently the only recognized premalignant precursor of prostatic adenocarcinomas (ADs) [4], which, together with small-cell neuroendocrine (NE) carcinoma, are considered the most malignant variants of PC [4]. PC usually arises in the peripheral zone of the gland and develops throughout the prostate capsule by peripheral dispersal. PC frequently invades the seminal vesicles and the bladder neck [5]. Metastatic spread occurs by exploiting both the lymphatic and the circulatory system, and metastases can be retrieved primarily in bone, pelvic lymph nodes, and bone marrow, and less frequently in lungs and liver [6].

A variety of experimental models, including transgenic mouse models and serum-dependent human PC cell lines, have been exploited to investigate PC pathogenesis. Among all the available animal models of PC, the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) mouse model is the most commonly used [5]. The TRAMP mouse model was generated by introducing the −426/+28 minimal rat probasin regulatory sequence to target SV40 early gene (T/t antigen) expression selectively to the prostate epithelium [7]. Probasin expression is regulated by androgens, and therefore, TAg protein production, which is initially restricted to the dorsolateral and ventral lobes of the gland, correlates with sexual maturity [8].

Prostatic disease in TRAMP mice closely resembles the human disease, as they spontaneously develop prostatic disease that progresses from mild-severe PIN (6–12 weeks) to focal adenocarcinoma (well-differentiated adenocarcinoma [WD AD]; 16–20 weeks) that may progress in a low percentage of mice to moderately differentiated (24 weeks) and poorly differentiated (24–30 weeks) AD. The disease often metastasizes to seminal vesicles, lymph nodes, and lungs, and occasionally to bone, kidney, and adrenal glands [5, 9, 10]. TRAMP mice may also develop a very aggressive NE prostate cancer, which represents 5% of all tumors in mice with a C57B6 background [5, 11]. Tumorigenesis in TRAMP mice is triggered by TAg activation, which results in the inactivation of Rb and p53 signaling networks [7, 5], which are commonly inactivated in human prostate cancer [12, 13]. However, additional mutations are also found in the TRAMP model. For instance, TRAMP-derived tumors display somatic mutations in the androgen receptor, a well-known key player in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer [14]. Similarly, TRAMP-derived cell lines show abnormalities in the centrosome-centriol regulation, thus leading to chromosomal instability and the accumulation of mutations [15]. As such, TRAMP cancer development and progression, androgen sensitivity, fine aspects of neoangiogenesis, and the activation of several metabolic pathways closely resemble the human pathology [16]. In fact, the TRAMP model has been validated as an accurate model to test chemical agents for prostate cancer prevention [17] as well as to identify therapeutically relevant targets and markers, such as Sox9, β4 integrin, and KLF6 [18–20], and to isolate circulating prostate tumor cells [21].

To date, more than 200 serum-dependent human PC cell lines have been generated for in vitro and in vivo studies [22, 23]. On the contrary, few mouse cell lines are available, including TRAMP-C1/C2 and RM1 cell lines, which were isolated from a TRAMP-derived AD and from a ras and myc transformed mouse prostate carcinoma, respectively [9, 24]. However, traditional serum-dependent cell lines do not fully mimic the human disease, thus raising many concerns about their applicability to preclinical studies. To overcome this limitation, several research groups set out to isolate normal prostate stem cells (PSCs) as well as prostate cancer stem cells (PCSCs) to be exploited as valuable and reliable preclinical experimental models. The first evidence of the existence of PSCs came from castration experiments, which indicated that prostate regression following androgen deprivation was rescued when physiological levels of androgen were restored, suggesting the existence of a population of stem cells (SCs) in the prostate. The process of serial regression and regeneration could be repeated for many cycles [25], thus indicating that PSCs may persist in the regressed state, similarly to other quiescent SCs residing in other organs [26]. Since most of cells in the basal layer are castration-resistant, PSCs are thought to reside in that layer. Recent studies have suggested that mouse Sca-1+ cells are more efficient in generating prostatic tissue than Sca-1− cells [27, 28], thus being enriched for putative PSCs. Likewise, human and murine PSCs could be isolated by exploiting Trop2 and CD49f expression [28–30].

Interestingly, when PSCs are transduced with a lentiviral vector carrying the activated forms of AKT, ERG, and androgen receptor (AR), they give rise to AD, thus suggesting that they may be considered putative PCSCs [30]. Notably, PCSCs could be enriched from mouse and human PC by using different combination of markers, such as CD44+/α2β1hi/CD133+ [31], Lin−/Sca-1+/CD49fhi [32, 33] and, recently, beta4hiSca-1hi [19]. After cell purification, cells were seeded according to the prostate sphere assay [34]. This method relies on a three-dimensional culture system that allows maintaining and expanding PSCs in vitro, although for a limited number of subculturing passages [34, 35].

The isolation of long-term expanding cancer stem cell (CSC) lines has been successfully achieved from different solid tumors by applying the neurosphere assay (NSA) [36]. Here we report that the application of the NSA to samples representative of the different TRAMP stages allowed the establishment of stage-specific PCSCs, endowed with endless self-renewal ability, multilineage differentiation, tumorigenic potential, and PCSC-specific molecular signatures.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Cell Lines, Primary Cell Cultures, and Cell Culture Propagation

TRAMP-C1 and TRAMP-C2 cells [9] and RM1 cells [24] (kindly provided by Dr. Mariana P. Monteiro, Università di Oporto, Porto, Portugal), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium, http://www.cambrex.com) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy, http://www.invitrogen.com), 150 U/ml streptomycin, and 200 U/ml penicillin (Cambrex). Tissue samples were collected from TRAMP mice [5], after staging was performed by an expert pathologist. Multiple 11-week TRAMP epithelial (11wT-Ep) samples were pooled (up to four different samples for each primary culture), whereas single tumor specimens were used for the other tumor grades. After microscopic dissection, tissues were enzymatically digested with collagenase IV (1,600 units/ml; Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, http://www.worthington-biochem.com) for 1 hour at 37°C. Following the removal of small undigested tissue fragments and differential centrifugation, the single-cell suspension was seeded in serum-free DMEM/F12 medium containing epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) [37]. Cultures were split every 2–10 days, according to the stage of origin. Long-term self-renewal analysis was performed as described previously [37]. The same procedure was applied to subcutaneous tumors formed by serially transplanted PCSC lines. PCSC differentiation was induced by culture in serum-free mitogen-free medium supplemented with 10−8 M dihydrotestosterone for 7–10 days in Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com)-coated flasks.

Molecular Analysis

Total RNA from PCSC lines was extracted using the RNeasy Micro and Mini kits (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, http://www.qiagen.com). cDNA was obtained by using Superscript RNaseH− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). All cDNAs were normalized throughout a β-actin reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available upon request.

Immunocytochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

PCSCs were plated at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells per cm2 onto Matrigel-coated glass coverslips for 48 hours. Immunocytochemistry (ICC) was performed as described previously [37]. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry were performed on 16-μm-thick cryostat sections. Bright-field immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4-μm sections from paraffin blocks, as previously described [38]. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and ICC were as follows: anti-mouse AR (1:50; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, http://www.chemicon.com), anti-mouse synaptophysin (Syn; 1:100; Novocastra Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K., http://www.novocastra.co.uk), mouse anti-TAg (1:100; BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-mouse cytokeratin 5 (CK5; 1:100; Covance, Princeton, NJ, http://www.covance.com), rat anti-mouse CK8 (1:200; kind gift of Dr. Luigi Poliani, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy), and mouse anti-mouse pan-cytokeratins (5, 6, 8) (pan-CKs; 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, http://www.abcam.com).

Marker Analysis by Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested and mechanically dissociated into a single-cell suspension. Cells were then resuspended in blocking solution (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] supplemented with 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8) and kept on ice for 20 minutes. The blocking solution was then removed and the antibody of interest added. All the antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution at specific working concentrations: anti-prominin-1 (1:50; eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, http://www.ebioscience.com) and Sca-1 PE (1:100; BD). Cells were incubated with the antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Acquisition was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCanto II instrument, and the analysis was performed using FCS Express 3.0 software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA, http://www.denovosoftware.com).

Evaluation of Tumorigenicity by Subcutaneous Injection

Each PCSC line was subcutaneously injected into the right flank of male or female nude mice. Cells were resuspended in 200 μl of DMEM supplemented with DNase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com). Tumor development was monitored for several weeks. Each experimental tumor was collected for histological analysis and serial transplantation assay.

Microarray-Based Gene Expression Profiling

The microarray used was the GeneChip Mouse 1.0 array from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, http://www.affymetrix.com). Quality control of hybridization was performed by Image Quality, MAplots, Boxplot, and Density Plot. Array normalization was executed by the RMA algorithms. Divisive clustering algorithms were used to obtain dendrograms, in which the biological samples were clustered based on the differentially expressed genes. The hierarchical clustering algorithms used were (a) distances (Euclidean, correlation), and (b) linkage (complete, single, McQuitty, Ward, centroid). The differentially expressed genes were obtained based on (a) t test moderated empirical Bayes, (b) p value (false discovery rate [FDR] adjusted 0.05), and (c) cut-off (log2 fold change [FC] >1).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

The human homologs and their hgu133plus2 Affymetrix probe identifiers were obtained using the biomaRt Bioconductor (Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA, http://www.bioconductor.org) package. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [39] was used to assess the degree of association between PCSC signatures and the molecular classification of human PCs in patient cohorts included in the data sets GSE17951 and GSE3325 [40, 41]. GSEA ranked genes according to their association with a given phenotype and determined whether genes in a signature tend to present either high (positively enriched) or low (negatively enriched) ranks with FDR <25%.

Results

Putative Prostate Cancer Stem Cells Can Be Isolated and Expanded In Vitro From TRAMP Mice

To assess the presence of putative PCSCs at different stages of cancer progression in the TRAMP mouse model, we collected stage-specific tumor specimens that were diagnosed as (a) mouse PIN at 11 weeks of development (11wT-Ep); (b) WD TRAMP epithelial AD, also infiltrating the seminal vesicles, at 35 weeks (35wT-Ep); and (c) TRAMP neuroendocrine (T-NE) tumor at 30 weeks [5].

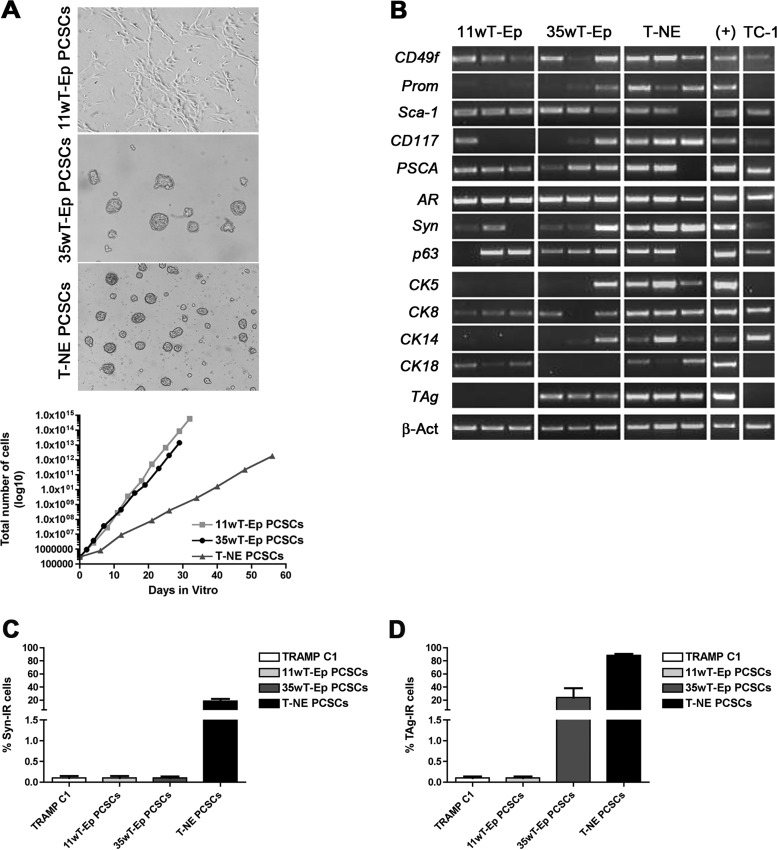

As opposed to standard NSA-based protocols, which take advantage of tryptic enzymes such as trypsin and papain, we digested prostate tumor tissues by using collagenase IV, which allowed good preservation of cell viability and highly efficient tissue disaggregation into single cells. Each single stage-specific tumor cell suspension was seeded according to the NSA (i.e., in serum-free medium containing EGF and FGF2 as mitogens) [42]. Four to 10 days after plating, phase-bright clones resembling classic spheres were observed in primary cultures obtained from 35wT-Ep and T-NE specimens (Fig. 1A). On the contrary, cultures from 11wT-Ep stages grew as a monolayer (Fig. 1A). Of note, the stage-specific in vitro growth of PCSCs as spheres or as cell monolayer was maintained after many subculturing passages. The efficiency of PCSC line establishment was 75% for 11wT-Ep, 32% for 35wT-Ep, and 50% for T-NE PCSCs.

Figure 1.

Putative prostate cancer stem cells (PCSCs) can be expanded in vitro from TRAMP mice and retain the expression of prostate-specific markers. (A): Top: Phase bright-field microphotographs depicting the modality of growth of distinct PCSCs. Magnification, ×200. Bottom: Long-term self-renewing rate of distinct PCSC lines. A representative PCSC line is reported for each tumor stage. (B): Semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction reporting the expression of stem cell and prostate-specific markers. (+): Normal prostate was used as positive control. For TAg amplification, the positive control was a TRAMP prostate. (C): Quantification of the frequency of Syn-IR cells. (D): Quantification of the frequency of TAg-IR cells. Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week TRAMP epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; IR, immunoreactive; PCSC, prostate cancer stem cell; Syn, synaptophysin; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine; TRAMP, transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate.

To rule out the possibility that transient amplifying progenitors, which could be propagated for a limited number of subculturing passages in vitro, might contribute to cell expansion in prostate cell cultures [42], we performed long-term population analysis on all the putative PCSC lines (Fig. 1A). As indicated by growth curves, which analyze the growth trend within a limited time window, all stage-specific PCSC cultures exponentially expanded in number, thus proving that they contained cells endowed with self-renewing ability. Each putative PCSC line could be propagated for up to 50 subculturing passages and displayed peculiar growth kinetics that, however, did not correlate with the tumor stage at which the lines were derived.

To test the multipotency of the different putative PCSC lines, we assessed the expression of PSC markers as well as of basal-, luminal-, or NE-specific markers by semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). The serum-dependent TRAMP-C1 cell line was used as internal control, together with a wild-type or, for TAg, a TRAMP postnatal prostate. Whereas CD49f, Sca-1, PSCA, and AR transcripts were expressed in most if not all putative PCSC types, CD133/Prominin-1, CD117, synaptophysin, and p63 transcripts were retrieved only in some of them. Similarly, transcripts for cytokeratins such as CK5, CK8, CK14, and CK18 were detected at different levels in the PCSC lines derived from the less aggressive tumor stages, while being consistently expressed in all T-NE lines. Surprisingly, TAg mRNA was expressed only in PCSC lines isolated at 35wT-Ep and T-NE stages. When PCSCs were induced to differentiate by dihydrotestosterone, the expression of stemness-related genes, such as CD49f and Prominin, was significantly downregulated in the differentiated progeny of most PCSC types (supplemental online Fig. 2). Interestingly, concurrent upregulation of basal markers, such as CK14 and p63, as well as neuroendocrine markers as synaptophysin, was retrieved in the differentiated progeny of T-NE PCSCs (supplemental online Fig. 2).

Some of the genes tested by RT-PCR were also validated at the protein level by flow cytometry (supplemental online Table 1) and ICC. Whereas Prominin-1 expression was retrieved only in a small fraction of cells in all lines, Sca-1 expression was observed in a higher percentage of cells, ranging from 26% to 95% of the total cell number. Only lines derived from T-NE tumors expressed synaptophysin also at the protein level (Fig. 1C). Likewise, TAg protein expression was detected in all T-NE lines (Fig. 1D) and in one of five 35wT-Ep PCSC lines (data not shown); it was absent in 11wT-Ep PCSC lines.

Stage-Specific PCSC Lines Are Tumorigenic

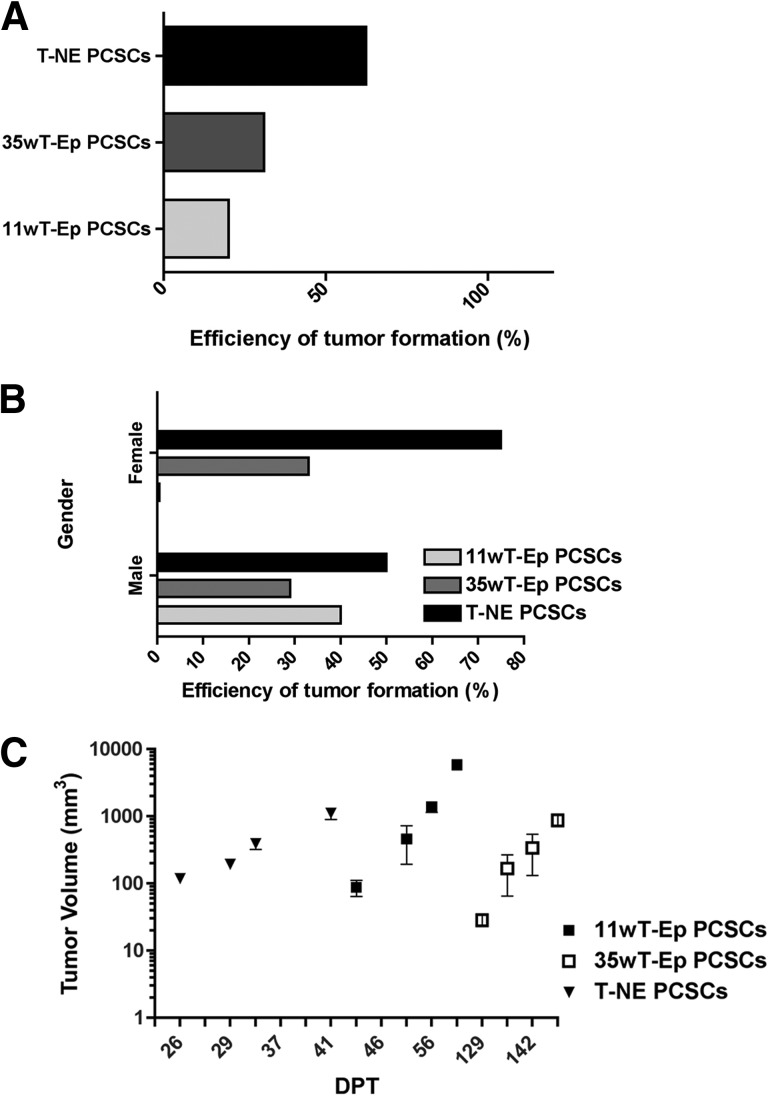

To assess whether putative PCSC lines were endowed with tumor-initiating capacity, thus satisfying the most stringent requirement for qualifying as bona fide cancer stem cells (CSCs), we transplanted stage-specific PCSCs subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice. Tumor formation was observed in all mice receiving 4 × 106 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSCs. For T-NE PCSCs, we also performed limiting dilution analysis, by transplanting 1 × 106, 1 × 105, 1 × 104, and 1 × 103 cells per animal. Tumors developed at every cell concentration but 103. Tumor onset and take efficiency of PCSCs were line- and stage-specific, with the highest take efficiency observed for those lines deriving from the most aggressive stage, that is, the T-NE PCSCs (Fig. 2A). To assess whether tumorigenicity might depend on the presence of sexual hormones, subcutaneous injections were performed in both male and female mice. For 35wT-Ep and T-NE PCSC lines, the efficiency of tumor formation was independent from gender, and, as such, from the presence of androgens. On the contrary, 11wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors developed only in male mice (Fig. 2B; supplemental online Table 2). Notably, whereas tumors from T-NE and 11wT-Ep PCSCs formed after 20–40 and 40–60 days after injection, respectively, 35wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors required more than 4 months to become detectable (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Stage-specific PCSCs are endowed with tumorigenic ability. (A): Efficiency of tumor formation upon PCSC transplantation, calculated over the total number of subcutaneously transplanted mice. (B): Efficiency of tumor formation upon PCSC transplantation, calculated over the total number of subcutaneously transplanted male and female mice. (C): Growth kinetics of PCSC-derived tumors. For each tumor stage, one representative putative PCSC line is reported. Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; DPT, days post-transplantation; PCSC, prostate cancer stem cell; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine.

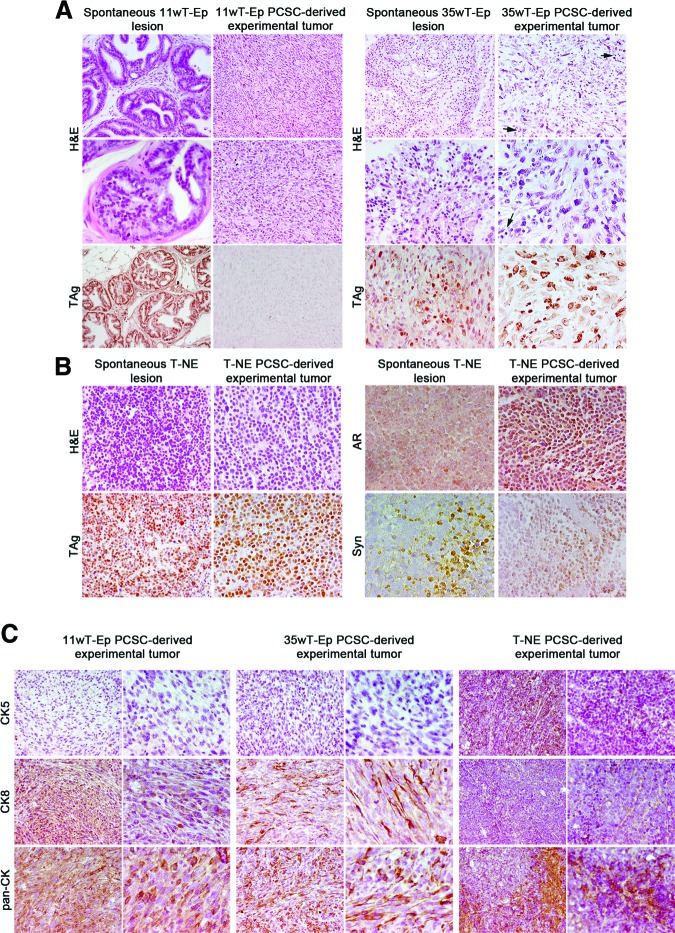

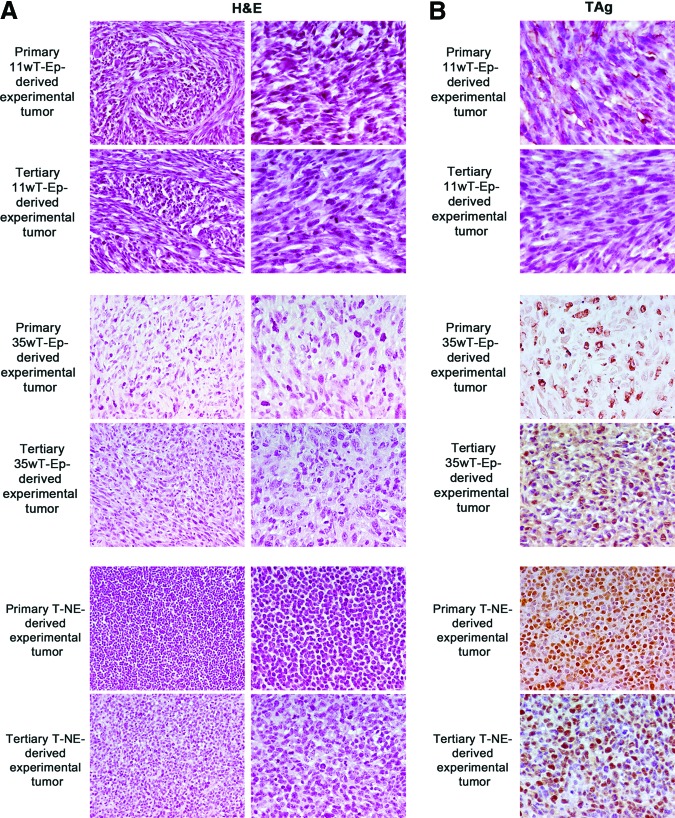

PCSC-Derived Tumors Phenocopy Autochthonous TRAMP Tumors

All the experimental tumors generated by the subcutaneous injection of 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC lines were subjected to histological analysis. H&E staining indicated that tumors induced by 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSC lines were very similar to tumors induced by the injection of TRAMP-C1 cells [9], as they displayed a marked sarcomatoid-epithelial appearance, and contained spindle-like and pleomorphic cells characterized by a large cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). However, whereas experimental tumors generated by 35wT-Ep lines displayed high content of extracellular matrix and infiltrating mast cells, the opposite was observed in tumors generated by 11wT-Ep lines (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, and in agreement with in vitro findings (Fig. 1), although autochthonous 11wT-Ep tumors did express TAg protein, the corresponding 11wT-Ep PCSC-derived experimental tumors did not. Conversely, tumors generated by 35wT-Ep and T-NE PCSCs maintained TAg immunoreactivity in vivo (Fig. 3A). 11wT-Ep PCSC-derived experimental tumors did not express either AR or Syn (supplemental online Fig. 1), whereas 35wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors displayed low AR immunoreactivity and were Syn-negative (not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that experimental tumors generated by 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSCs reproduced to some extent the spontaneous TRAMP tumor of origin and were reminiscent of TRAMP-C1-derived tumors, which typically display a sarcomatoid-epithelial appearance (supplemental online Fig. 1).

Figure 3.

Stage-specific PCSCs give rise to tumors that resemble autochthonous transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) tumors. (A): Comparative histological analysis of spontaneous TRAMP 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep tumors and experimental tumors derived from 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSCs. Magnification (from top to bottom), ×200, ×400, and ×200 for 11wT-Ep lesions; ×200, ×400, and ×400 for 35wT-Ep lesions. Arrows point to intratumoral mast cells (right panels). (B): Comparative histological analysis of spontaneous TRAMP T-NE tumors and experimental tumors derived from T-NE PCSCs. Magnification, ×400. (C): Expression of CK5, CK8, and pan-CK in 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC-derived tumors. Magnification, ×200 and ×400. Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week TRAMP epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; AR, androgen receptor; CK, cytokeratin; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PCSC, prostate cancer stem cell; Syn, synaptophysin; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine.

Most notably, experimental tumors generated by T-NE PCSC lines closely resembled their spontaneous TRAMP NE tumor of origin. In fact, T-NE PCSC-derived tumors comprised small round neoplastic cells, characterized by thin cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). Necrosis was frequently observed, whereas infiltrating mast cells were rare. Similar to spontaneous T-NE tumors, T-NE PCSC-derived tumors displayed a high frequency of TAg immunoreactive cells, as well as focal areas positive for AR and Syn (Fig. 3B).

Experimental PCSC-derived tumors were also tested by IHC for the expression of prostate epithelial markers such as cytokeratins (Fig. 3C). In line with transcriptional data on PCSCs (Fig. 1D), CK8 and the other CKs recognized by a pan-antibody were strongly expressed in experimental tumors generated by 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSCs, whereas CK5 was not retrieved in the same samples. Interestingly, CK8 was expressed in most cells in 11wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors while being restricted to a fraction of tumor cells in tumors derived from 35wT-Ep PCSC lines (Fig. 3C). CK5, CK8, and pan-CK were all expressed in T-NE PCSC-derived tumors (Fig. 3C).

PCSCs Are Endowed With In Vivo Self-Renewal Capacity

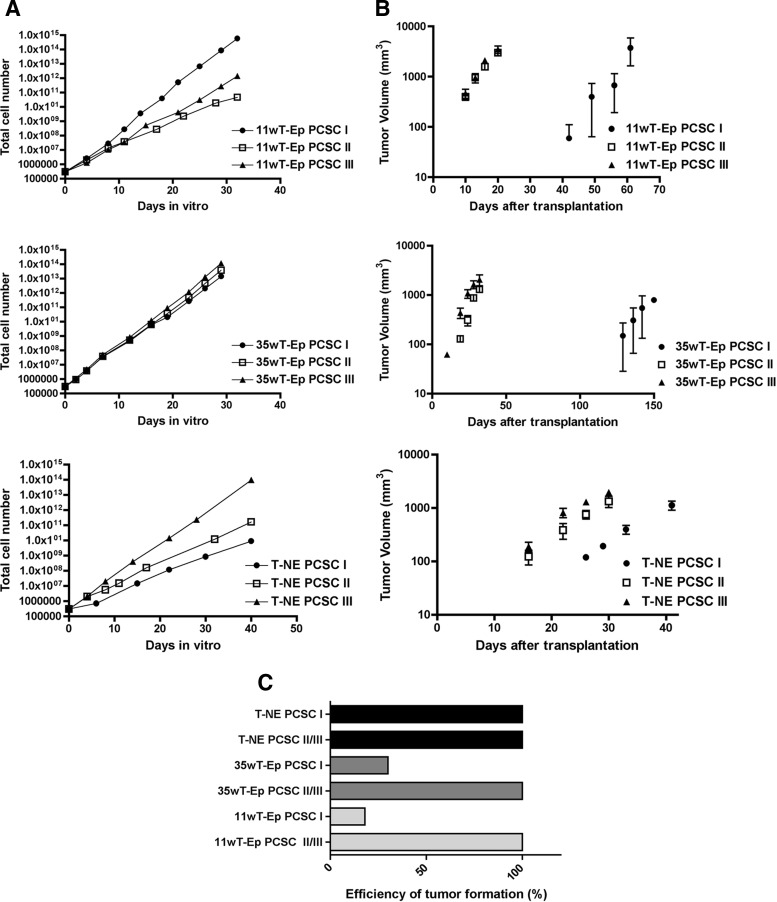

To conclusively demonstrate the stemness of PCSC lines, we performed sequential transplantation experiments by injecting 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSCs (PCSC I) subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice, where they gave rise to primary experimental tumors. From these last tumors, secondary PCSC (PCSC II) lines were established and then transplanted in a secondary recipient. This sequential procedure was repeated up to the third in vivo passage, giving rise to tertiary PCSC (PCSC III) lines.

Secondary and tertiary PCSC lines, together with their primary PCSC lines as controls, were first subjected to in vitro long-term self-renewal analysis (Fig. 4A). Whereas secondary and tertiary 11wT-Ep PCSC lines proliferated significantly more slowly than their parental PCSC lines, secondary and tertiary T-NE PCSC lines expanded in vitro more rapidly than primary T-NE PCSCs, suggesting the progressive enrichment in the stem cell component or the exacerbation of PCSC malignant properties through in vivo passages. On the contrary, secondary and tertiary 35wT-Ep PCSC lines did not show evident changes in their proliferation rate as compared with their parental primary lines. Notwithstanding the differences in growth rate in vitro, when transplanted subcutaneously, secondary and tertiary 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC lines formed tumors, which develop much faster than tumors generated by the corresponding primary lines (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, the formation of secondary and tertiary tumors was detected much earlier than that of primary tumors, thus indicating a progressive increase in PCSC tumor-initiating ability throughout serial transplantation (10 days for secondary and tertiary 11wT-Ep PCSC tumors vs. 42 days for primary 11wT-Ep PCSC tumors; 10 days for secondary and tertiary 35wT-Ep PCSC tumors vs. 130 days for primary 35wT-Ep PCSC tumors; 16 days for secondary and tertiary T-NE tumors vs. 25 days for primary T-NE tumors) (Fig. 4B). Of note, the tumor take efficiency became 100% for all tumors and, for 11wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors, became independent from gender (Fig. 4C; supplemental online Table 3). Thus, serially transplanted PCSCs showed enhanced malignancy that might have been exacerbated by the selection of highly malignant cells upon transplantation, tumor growth, and reculturing.

Figure 4.

PCSCs self-renew in vivo. (A): In vitro long-term self-renewal analysis of primary (I), secondary (II), and tertiary (III) 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC lines. (B): In vivo serial transplantation assay for 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC I–III lines. (C): Efficiency of tumor formation from primary, secondary, and tertiary PCSC lines. Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; PCSC, prostate cancer stem cell; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine.

All the experimental tumors generated through serial transplantation were subjected to IHC (Fig. 5). H&E staining indicated that all secondary and tertiary tumors maintained the same phenotypic appearance of the corresponding primary experimental tumors, with the exception of increasing sarcomatoid features in secondary and tertiary 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSC-derived experimental tumors (Fig. 5A). TAg expression as detected at the third in vivo passage was similar to that of primary experimental tumors (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Secondary and tertiary prostate cancer stem cell (PCSC)-derived tumors maintained the same phenotypic appearance of the corresponding primary experimental tumors. (A): Comparative histological analysis of experimental tumors deriving from 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC I and PCSC III lines. (B): TAg expression in experimental tumors deriving from 11wT-Ep, 35wT-Ep, and T-NE PCSC I and PCSC III lines. Magnification, ×400. Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine.

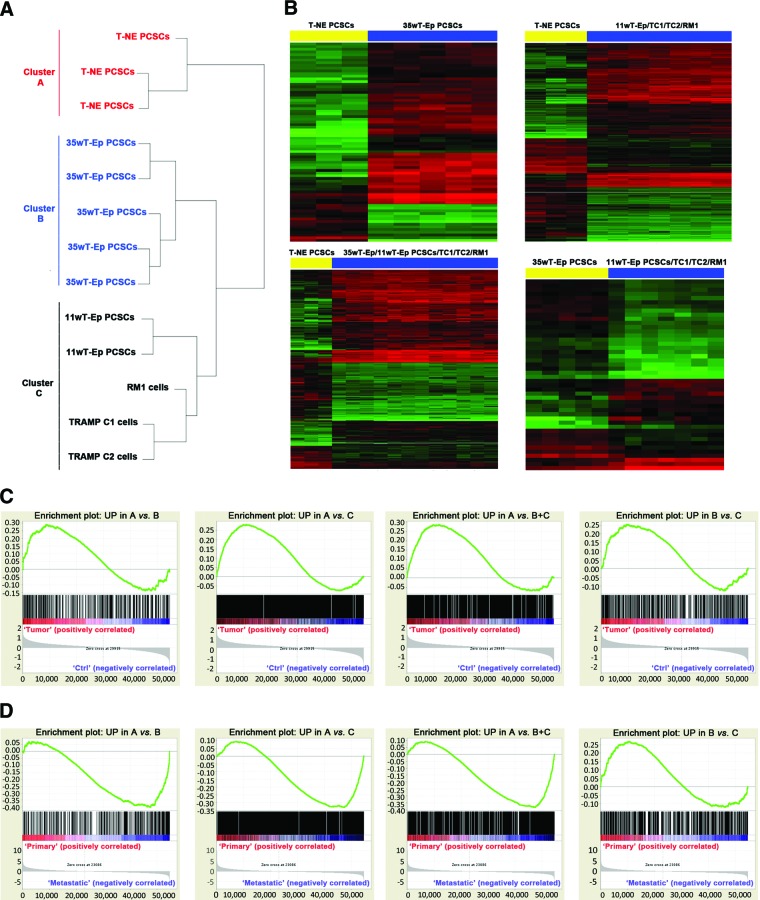

Stage-Specific PCSC Lines Are Molecularly Distinct and Molecularly Resemble Human PC

To characterize the distinct stage-specific PCSC lines from a molecular standpoint, we subjected them to microarray-based whole-transcript analysis. Unsupervised clustering revealed that the gene expression profile of T-NE PCSCs was very different from that of the other stage-specific PCSC lines and of serum-dependent mouse prostate cancer cell lines, such as TRAMP-C1/C2 and RM1 cells (Fig. 6A). Indeed, three different clusters were identified: cluster A, including T-NE PCSCs; cluster B, including 35wT-Ep PCSCs; and cluster C, comprising 11wT-Ep PCSCs as well as TRAMP C1/C2 and RM1. Within cluster C, 11wT-Ep PCSCs were molecularly very similar, while being clearly distinct from TRAMP-C1/C2 and RM1 cells (Fig. 6A). As expected, all tumor cell lines (i.e., PCSCs and TRAMP-C1/C2 and RM1 cells) clustered separately from mouse normal prostate stem cells, whose expression data were obtained from a publicly available data set (GSE15580; supplemental online Fig. 3) [43].

Figure 6.

PCSC-specific gene signatures are enriched in human prostate cancer (PC) transcriptional data sets. (A): Unsupervised clustering of PCSC lines and serum-grown prostate cancer cell lines. (B): Heatmap reporting the global gene expression data in the different comparisons. Differentially expressed genes with a p value <.05 are shown as red (upregulated) or green (downregulated). (C): Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) enrichment plots. Each gene signature was compared with molecular subgroups CTRL and TUMOR from the human PC data set GSE17951. (D): GSEA enrichment plots. Each gene signature was compared with molecular subgroups BENIGN, PRIMARY, and METASTATIC from the human PC data set GSE3325. In (C) and (D), the green line indicates the enrichment profile, the black lines indicate the hits, and the gray curve in the bottom panel indicates the ranking metric scores. The y-axis indicates the enrichment score in the top panels and the ranked list metric (Signal2Noise) in the bottom panels. The x-axis in all panels represents the rank in the ordered data set. The zero cross in the bottom panels is at 29,915 (C) or 23,086 (D). Abbreviations: 11wT-Ep, 11-week transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) epithelial; 35wT-Ep, 35-week TRAMP epithelial; PCSC, prostate cancer stem cell; T-NE, TRAMP neuroendocrine.

Cluster A T-NE PCSCs were sharply distinguishable from cluster B and cluster C stage-specific PCSC lines, with 1,834 and 3,832 differentially expressed probe sets, respectively. Likewise, cluster A PCSCs differ from cluster B+C PCSCs for the expression of 2,879 probe sets. Notably, cluster B PCSCs differentially expressed 2,010 genes versus cluster C PCSCs. Representative heatmaps for each comparison are shown in Figure 6B (linkage complete, log2FC >1, p < .05). Remarkably, many genes upregulated in cluster A T-NE PCSCs in the comparisons A versus B, A versus C and A versus B+C were related to neural differentiation and secretory pathways, such as Sox11 (log2FC 4.07), synaptotagmins (Syt1 and Syt11, log2FC 3.2 and 2.18), synaptogyrin 3 (Syngr3, log2FC 1.8), ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor (Cntfr, log2FC 1.63), neurexin 1 (Nrxn1, log2FC 2.56), and Hes6 (log2FC 1.16). Again, many of these genes were overexpressed in spontaneous NE tumors isolated from the TRAMP mouse as well as from a different mouse model of prostate cancer [44, 45], thus indicating that, in line with the similarities in the histological features observed between spontaneous TRAMP T-NE lesions and T-NE PCSC-derived tumors, T-NE PCSCs resembled faithfully their tumor of origin also at the molecular level. Most relevantly, genes such as Aurora Kinase A (Aurka, log2FC 1.18), MycN (log2FC 2.35), and Ezh2 (log2FC 1.45), which were recently found to be specifically overexpressed in human NE prostate tumors where they induce the expression of NE markers [46], were also significantly upregulated in T-NE PCSCs.

Gene expression data were then exploited to generate gene signatures that reflected the molecular differences between distinct stage-specific PCSCs. The first signature included genes upregulated in T-NE PCSCs versus 35wT-Ep PCSCs (cluster A vs. cluster B; UP in A vs. B, List S1), the second signature comprised genes upregulated in T-NE PCSCs versus 11wT-Ep PCSCs/TRAMP C1/C2/RM1 (cluster A vs. cluster C; UP in A vs. C, List S2), and the third comprised genes overexpressed in T-NE PCSCs versus all the other cell lines (cluster A vs. cluster B+C, UP in A vs. B+C, List S3). A fourth gene signature included the genes upregulated in 35wT-Ep PCSCs vs.11wT-Ep PCSCs/TRAMP C1/C2/RM1 (cluster B vs. cluster C, UP in B vs. C, List S4). Four additional gene signatures were generated by considering the genes downregulated in the same comparisons (not shown).

Next, we investigated whether the different gene signatures could stratify human PCs according to their clinical characteristics, as exemplified by their enrichment in specific clinical subclasses by GSEA [39]. To this end, we took advantage of two different human data sets, which contained molecular profiling of different human PCs linked to clinical data [40, 41]. The first data set, GSE17951, returned clinical information for 154 human samples that were identified as normal prostate tissues (CTRL) and tumor tissues (TUMOR). The second data set, GSE3325, comprised three different groups of 19 human samples, classified based on their clinical features (BENIGN prostate tissues, clinically localized PRIMARY tumors and METASTATIC tumors). Interestingly, the molecular signatures UP in A versus B, UP in A versus C and UP in A versus B+C (i.e., genes upregulated in T-NE PCSCs) were significantly enriched in the TUMOR sample subgroup versus CTRL in the data set GSE17951 (Fig. 6C) and in the METASTATIC subgroup versus PRIMARY in the data set GSE3325 (Fig. 6D). Accordingly, the corresponding DOWN signatures were enriched in the subgroups CTRL and PRIMARY of the two data sets (not shown).

It is notable that the gene signature made by the genes upregulated in the comparison of cluster B PCSCs versus cluster C cells (UP in B vs. C) was significantly enriched in the TUMOR subgroup, indicating that 35wT-Ep PCSCs are more malignant than 11wT-Ep PCSCs, in agreement with the in vivo phenotype of the tumors of origin (Fig. 6C). However, 35wT-Ep PCSCs remained less malignant than T-NE PCSCs, as the gene signature cluster B versus cluster C was enriched in the PRIMARY subgroup and not in the METASTATIC subgroup (Fig. 6D).

As such, from a molecular standpoint, stage-specific murine PCSCs hierarchically resemble the stages of progression of human PC, with T-NE PCSCs being the most malignant and 11wT-Ep PCSCs being the less malignant. Thus, TRAMP-derived PCSCs can be considered a valuable and reliable preclinical model of the corresponding human disease.

Discussion

Considerable effort has been directed toward the identification of markers associated with the initiation and progression of PC. As tumor cells are expected to share some of their antigenic properties with normal SCs, several research groups identified putative CSCs by exploiting the same markers that have been used for the isolation of normal PSCs [31–33, 47]. CSCs have been purified from prostatic tumor tissues as well as from traditional or immortalized prostate cell lines and then cultured in vitro by the prostate sphere assay. However, this assay allows cells to grow in vitro only for a limited number of subculturing passages, thus making it difficult to exploit these cultures for studies that require large quantities of cells [34]. To date, no attempt has been made to establish long-term expanding CSC lines from the TRAMP mouse model by exploiting the NSA functional in vitro assay [48].

In this study, we demonstrated that the application of the NSA to tumor specimens obtained from different stages of prostate tumor progression in the TRAMP mouse results in the establishment of long-term self-renewing, multipotent PCSCs that can be easily expanded in culture without any three-dimensional support. These PCSCs maintain the expression of prostate-specific markers such as basal (p63 and CK14), luminal (AR, CK8/18), and neuroendocrine (Syn) markers [47] and (in particular, T-NE PCSCs) modulate their expression upon differentiation.

These PCSC lines fulfill all the criteria required for qualifying as bona fide CSCs. In particular, stage-specific PCSCs display both tumorigenic potential and, relevantly, self-renewing ability in vivo, as demonstrated by challenge through serial transplantation [37]. Most relevantly, PCSCs gave rise to tumors under these very restrictive transplantation settings, that is, in the absence of external trophic support, as that supplied by urogenital sinus mesenchyme cells [32, 33, 47]. Notably, T-NE PCSC-derived tumors arose at a high frequency and displayed features that correlate well with the malignancy of primitive T-NE tumors. Indeed, this is the first report in which several prostate cell lines were isolated from T-NE lesions and were capable of consistently giving rise to experimental tumors that very closely resembled the tumor of origin, both histologically and molecularly. Remarkably, T-NE PCSC-derived experimental lesions that very faithfully mimicked mouse spontaneous prostate NE tumors bore the significant advantage of developing at a faster rate than the spontaneous ones (25 days and 24 weeks, respectively). As such, T-NE PCSCs might be exploited for all those applications in which short time windows are required.

Notably, 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSC lines generated tumors characterized by a sarcomatoid-epithelial appearance, which is similar to that of tumors induced by TRAMP-C1 cells. This phenomenon might be ascribed to the different cellular origin of the 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep lesions with respect to poorly differentiated T-NE tumors. Indeed, 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep tumors might be the result of TAg-transgene expression in secretory epithelial cells, whereas poorly differentiated T-NE tumors might arise from TAg-transformed transit-amplifying cell already committed to a NE lineage [49]. Another possible explanation concerns the site of injection exploited. Indeed, the subcutaneous milieu might selectively induce 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSCs to acquire a sarcomatoid-epithelial appearance, as also suggested by the progressive increase in sarcomatous features detected 11wT-Ep and 35wT-Ep PCSC-derived tumors in upon serial transplantation. As such, orthotopic transplantation might provide valuable insights into this controversial issue.

From a molecular perspective, genetic comparisons between the different PCSCs underscored their intrinsic molecular differences. Indeed, gene expression profiles associated with specific cellular/biochemical pathways were specifically retrieved in stage-specific PCSCs. As an example, the activation of genes associated with the NE phenotype and previously detected in microdissected tissue specimens derived from different stages of TRAMP PC development [44] was specifically observed only in T-NE PCSCs.

Most importantly, genes upregulated in each stage-specific PCSC line were significantly associated with distinct clinical subgroups, indicating that mouse PCSCs define human PC progression signatures. These findings confirm those reported in a very recent study showing that oncogene-induced experimental transformation of normal mouse prostate cells results in PC cell lines, whose molecular profile is associated with different clinical stages [50], and extend the concept to mouse PCSCs. However, as opposed to TRAMP-derived PCSCs, none of the cell lines described in the study by Ju et al. [50] histologically reproduced the different stages of prostate cancer progression, in particular the NE phenotype.

In conclusion, the NSA can be successfully applied to specimens derived from different stages of PC progression from the TRAMP mouse in order to establish long-term propagating PCSCs. Although further in vivo experiments are required to fully define the tumorigenic potential of PCSCs, this study provides the first evidence that a functional in vitro assay may be used for the isolation of PCSCs from autochthonous mouse tumors. Relevantly, these PCSCs molecularly phenocopy the corresponding human PC. As the current clinical management of PC is still unsatisfactory, especially for PCs that undergo NE differentiation after androgen ablation therapy [51], the functional and molecular characterization of stage-specific PCSCs (i.e., the cells responsible for tumor initiation, progression, and relapse) might lead to the identification of novel potentially relevant mediators of prostate cancer development. Our findings provide a rationale for the exploitation of mouse PCSCs as a valuable preclinical model for human PC, both for the definition of CSC-associated gene signatures holding a highly predictive value when tested across human data sets and for the identification of genes to be targeted therapeutically. In the end, these novel PCSC lines might be exploited for the development of biotherapeutic approaches for the cure of PC, with the aim of targeting the most aggressive cell type found in tumors, namely the CSC.

Conclusion

Here we report that by combining the availability of the primary TRAMP model of human PC with the NSA, we could generate a collection of stage-specific bona fide PCSC lines. Comparison of transcriptome profiles between stage-specific PCSCs from TRAMP mice yielded well-defined gene signatures that identify distinct stages of human PC progression. Thus, PCSCs represent a new tool for elucidating the pathogenesis of PC and for identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Alleanza Contro il Cancro-Istituto Superiore di Sanità (to R.G. and M.B.) and Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (to M.B.).

Author Contributions

S. Mazzoleni and E.J.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; S. Morosini, M.G., I.S.P., M.P., A.B., and M.F.: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; M.B. and R.G.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, financial support.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jadvar H. Prostate cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;727:265–290. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-062-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy-Burman P, Wu H, Powell WC, et al. Genetically defined mouse models that mimic natural aspects of human prostate cancer development. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:225–254. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0110225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson SI. Premalignant and malignant prostate lesions: Pathologic review. Cancer Control. 2010;17:214–222. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan-Lefko PJ, Chen TM, Ittmann MM, et al. Pathobiology of autochthonous prostate cancer in a pre-clinical transgenic mouse model. Prostate. 2003;55:219–237. doi: 10.1002/pros.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurwitz AA, Foster BA, Allison JP, et al. The TRAMP mouse as a model for prostate cancer. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im2005s45. Chapter 20:Unit 20.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg NM, DeMayo F, Finegold MJ, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3439–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Morton RA, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4096–4102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster BA, Gingrich JR, Kwon ED, et al. Characterization of prostatic epithelial cell lines derived from transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3325–3330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiaverotti T, Couto SS, Donjacour A, et al. Dissociation of epithelial and neuroendocrine carcinoma lineages in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model of prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:236–246. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abate-Shen C. A new generation of mouse models of cancer for translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5274–5276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar-Sinha C, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM. Recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:497–511. doi: 10.1038/nrc2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: New prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han G, Foster BA, Mistry S, et al. Hormone status selects for spontaneous somatic androgen receptor variants that demonstrate specific ligand and cofactor dependent activities in autochthonous prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11204–11213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatten H, Wiedemeier AM, Taylor M, et al. Centrosome-centriole abnormalities are markers for abnormal cell divisions and cancer in the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. Biol Cell. 2000;92:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(00)01079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shappell SB, Thomas GV, Roberts RL, et al. Prostate pathology of genetically engineered mice: Definitions and classification. The consensus report from the Bar Harbor meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2270–2305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguewa PA, Calvo A. Use of transgenic mice as models for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:705–718. doi: 10.2174/156652410793384196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Z, Hurley PJ, Simons BW, et al. Sox9 is required for prostate development and prostate cancer initiation. Oncotarget. 2012;3:651–663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshioka T, Otero J, Chen Y, et al. β4 Integrin signaling induces expansion of prostate tumor progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:682–699. doi: 10.1172/JCI60720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiam K, Ryan NK, Ricciardelli C, et al. Characterization of the prostate cancer susceptibility gene KLF6 in human and mouse prostate cancers. Prostate. 2013;73:182–193. doi: 10.1002/pros.22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho FL, Simons BW, Antonarakis ES, et al. Tumorigenic potential of circulating prostate tumor cells. Oncotarget. 2013;4:413–421. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobel RE, Sadar MD. Cell lines used in prostate cancer research: A compendium of old and new lines: Part 2. J Urol. 2005;173:360–372. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000149989.01263.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobel RE, Sadar MD. Cell lines used in prostate cancer research: A compendium of old and new lines: Part 1. J Urol. 2005;173:342–359. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141580.30910.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baley PA, Yoshida K, Qian W, et al. Progression to androgen insensitivity in a novel in vitro mouse model for prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;52:403–413. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00001-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsujimura A, Koikawa Y, Salm S, et al. Proximal location of mouse prostate epithelial stem cells: A model of prostatic homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1257–1265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang ZA, Shen MM. Revisiting the concept of cancer stem cells in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1261–1271. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burger PE, Xiong X, Coetzee S, et al. Sca-1 expression identifies stem cells in the proximal region of prostatic ducts with high capacity to reconstitute prostatic tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7180–7185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502761102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawson DA, Xin L, Lukacs RU, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of murine prostate stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609684104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein AS, Lawson DA, Cheng D, et al. Trop2 identifies a subpopulation of murine and human prostate basal cells with stem cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20882–20887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811411106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein AS, Huang J, Guo C, et al. Identification of a cell of origin for human prostate cancer. Science. 2010;329:568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.1189992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulholland DJ, Xin L, Morim A, et al. Lin-Sca-1+CD49fhigh stem/progenitors are tumor-initiating cells in the Pten-null prostate cancer model. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8555–8562. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao CP, Adisetiyo H, Liang M, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance the gland-forming capability of prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7294–7303. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xin L, Lukacs RU, Lawson DA, et al. Self-renewal and multilineage differentiation in vitro from murine prostate stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2760–2769. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lukacs RU, Goldstein AS, Lawson DA, et al. Isolation, cultivation and characterization of adult murine prostate stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:702–713. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: Accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertilaccio MT, Grioni M, Sutherland BW, et al. Vasculature-targeted tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases the therapeutic index of doxorubicin against prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008;68:1105–1115. doi: 10.1002/pros.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Xia XQ, Jia Z, et al. In silico estimates of tissue components in surgical samples based on expression profiling data. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6448–6455. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varambally S, Yu J, Laxman B, et al. Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of prostate cancer reveals signatures of metastatic progression. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blum R, Gupta R, Burger PE, et al. Molecular signatures of prostate stem cells reveal novel signaling pathways and provide insights into prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kela I, Harmelin A, Waks T, et al. Interspecies comparison of prostate cancer gene-expression profiles reveals genes associated with aggressive tumors. Prostate. 2009;69:1034–1044. doi: 10.1002/pros.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu Y, Ippolito JE, Garabedian EM, et al. Molecular characterization of a metastatic neuroendocrine cell cancer arising in the prostates of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44462–44474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:487–495. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu G, Yuan J, Wills M, et al. Prostate cancer cells with stem cell characteristics reconstitute the original human tumor in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4807–4815. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds BA, Rietze RL. Neural stem cells and neurospheres: Re-evaluating the relationship. Nat Methods. 2005;2:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huss WJ, Gray DR, Tavakoli K, et al. Origin of androgen-insensitive poorly differentiated tumors in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Neoplasia. 2007;9:938–950. doi: 10.1593/neo.07562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ju X, Ertel A, Casimiro MC, et al. Novel oncogene-induced metastatic prostate cancer cell lines define human prostate cancer progression signatures. Cancer Res. 2013;73:978–989. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komiya A, Suzuki H, Imamoto T, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in the progression of prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2009;16:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.