Abstract

In Escherichia coli, FadR and FabR are transcriptional regulators that control the expression of fatty acid degradation and unsaturated fatty acid synthesis genes, depending on the availability of fatty acids. In this report, we focus on the dual transcriptional regulator FadR. In the absence of fatty acids, FadR represses the transcription of fad genes required for fatty acid degradation. However, FadR is also an activator, stimulating transcription of the products of the fabA and fabB genes responsible for unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. In this study, we show that FadR directly activates another fatty acid synthesis promoter, PfabH, which transcribes the fabHDG operon, indicating that FadR is a global regulator of both fatty acid degradation and fatty acid synthesis. We also demonstrate that ppGpp and its cofactor DksA, known primarily for their role in regulation of the synthesis of the translational machinery, directly inhibit transcription from the fabH promoter. ppGpp also inhibits the fadR promoter, thereby reducing transcription activation of fabH by FadR indirectly. Our study shows that both ppGpp and FadR have direct roles in the control of fatty acid promoters, linking expression in response to both translation activity and fatty acid availability.

INTRODUCTION

The biochemical pathways for fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis and for fatty acid degradation have been studied extensively in bacteria, especially in Escherichia coli (1–3). Type II fatty acid synthesis (FASII) takes place in the cytoplasm, and enzymes have been identified that account for each step in the pathway. In this pathway, acyl carrier protein (ACP) acts as a cofactor by shuttling acyl chains between the successive enzymes (1). In contrast, the fatty acid degradation pathway can be envisioned as the reverse of the synthesis pathway, with coenzyme A (CoA) acting as the cofactor instead of ACP (3). The overall biochemistry of these pathways is conserved in bacteria, although there is variation in the exact nature and number of the enzymes involved (1, 4).

The regulatory mechanisms responsible for response to fatty acid availability vary in different bacteria (5–7). Activators and repressors of promoters regulating genes for fatty acid synthesis or degradation have been identified. In E. coli, expression of the fatty acid degradation (fad) genes is inhibited by the transcriptional repressor FadR in its apo form, but when long-chain fatty acids are available, acyl-CoA binds to FadR, releasing the repressor from the promoter and inducing fatty acid degradation (8). Regulators analogous to FadR that repress fatty acid degradation genes have also been described in other bacteria, such as PsrA in the Pseudomonadales (6) and YsiA (FadR) in Bacillus subtilis (9).

The mechanisms responsible for regulation of the fatty acid synthesis (fab) genes are more varied among bacteria than are the mechanisms responsible for regulation of the degradation (fad) genes. In Gram-positive bacteria, fab genes are organized in operons controlled either by repressors or by activators that respond to fatty acid availability (5, 7, 10). For example, in Bacillus subtilis, repression by FapR is relieved by binding short-chain malonyl-CoA or malonyl-ACP (11). In contrast, in Streptococcus pneumoniae, repression is caused by the presence of long-chain acyl-ACP (12). The repressor MabR regulates expression of the FASII genes in mycobacteria (13), whereas in Streptomyces coelicolor, the fab genes are regulated by an activator, FasR (14). In contrast to Gram-positive bacteria, it was thought previously that not all the fab genes in E. coli were controlled by fatty acid availability; rather, it was thought that regulation was restricted to unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis by FadR and FabR regulation of only the fabA and fabB genes. FadR activates transcription of fabA and fabB when it binds in its apo form (15, 16), whereas FabR represses transcription of fabA and fabB in the presence of unsaturated fatty acids (17, 18). However, a recent report showed that overproducing FadR leads to the upregulation of most of the fatty acid synthesis genes, suggesting that genes other than fabA and fabB might be regulated by FadR (19).

In addition to responding to fatty acid availability as described above, lipid biogenesis is also regulated by nutritional conditions, i.e., growth rate, growth phase, and nutrient starvation (the stringent response) (20–22), responses to each of which are mediated, at least in part, by accumulation of the modified nucleotide guanosine 3′-diphosphate 5′-diphosphate (ppGpp). In E. coli, ppGpp binds directly to RNA polymerase (RNAP) (23, 24), and in the presence of the RNAP cofactor DksA, it inhibits transcription from a large number of promoters involved in protein synthesis and other cell processes, whereas it activates a wide variety of promoters involved in stress responses (22). ppGpp has also been proposed to act directly on several types of enzymes other than RNAP (25–27). Hence, in some bacteria, ppGpp does not directly regulate RNAP but impacts the transcription apparatus indirectly (28) by controlling enzymes involved in GTP homeostasis (27).

It has been proposed that ppGpp directly inhibits the PlsB enzyme, the first acyltransferase of the phospholipid synthesis pathway, i.e., regulating lipid synthesis at the enzyme activity level (29, 30). Other reports suggest that ppGpp might control fatty acid synthesis at the level of transcription. For example, expression of the accABCD operon (encoding acetyl-CoA carboxylase) is growth rate dependent (31), and the promoter driving expression of the fabHDG genes encoding the enzymes in the fatty acid elongation cycle is subject to the stringent response (32). Consistent with these reports, transcriptome studies provided evidence for a decrease in fatty acid synthesis gene expression during the stringent response (e.g., accC, accD, fabH, fabF, and fabD) (33, 34).

To clarify the mechanisms responsible for this complex set of regulatory responses in E. coli, we focused our work on the fabH promoter because, as indicated above, previous reports suggested that it might be both a target of the stringent response (32) and subject to activation by FadR (19). fabH is located in what we refer to here as the fab-acpP locus, which includes the fatty acid synthesis genes fabH, fabD, fabG, acpP, and fabF as well as three upstream genes cotranscribed with fabH (35, 36): plsX, which is involved in phospholipid synthesis; rpmF, which codes for the L32 ribosomal protein; and yceD, for which a function has not been reported (Fig. 1A). The control of this region is complex, with previous reports describing at least 4 different promoters and transcripts corresponding to different subsets of the genes in the locus (Fig. 1A) (32, 35, 37, 38).

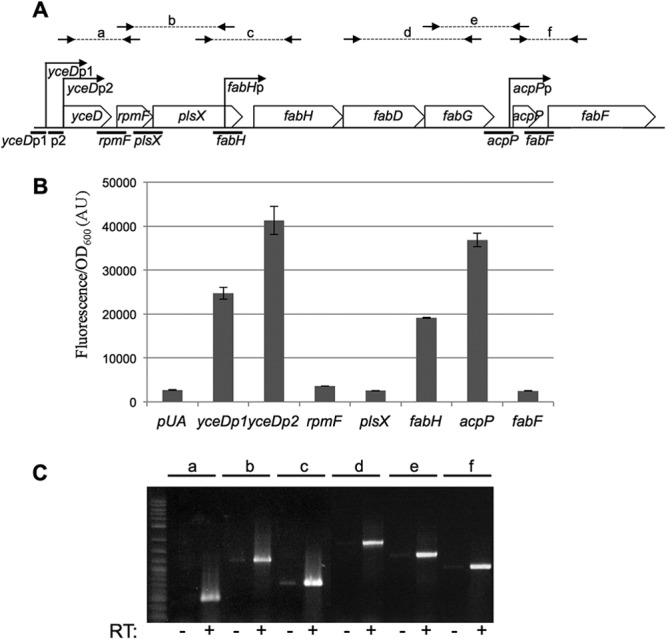

Fig 1.

Genetic organization of the fab-acpP locus. (A) Organization of the fab-acpP locus. The promoters indicated with arrows are the ones characterized in this study and were described previously: yceDp1 and yceDp2 (35), fabH (32), and acpP (37). Thick lines below the locus indicate the DNA regions assayed for promoter activity with transcriptional fusion in the experiment shown in panel B. Small arrows and letters above the panel indicate the positions of hybridization of the oligonucleotides used for the RT-PCR experiment shown in panel C. (B) The MG1655 strain was transformed by the indicated transcriptional fusions with gfp. Relative fluorescence intensities were measured after overnight growth in LB at 30°C (see Materials and Methods). pUA is the control plasmid pUA66 (39). (C) RT-PCRs were performed on total RNA prepared on MG1655 cells in exponential phase, with oligonucleotide pairs as follows: PCR a, ebm567/267; PCR b, ebm266/554; PCR c, ebm553/260; PCR d, ebm270/273; PCR e, ebm272/49; PCR f, ebm48/134 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for the sequences of the oligonucleotides). The positions of hybridization of the oligonucleotides are indicated in panel A. − and + indicate the absence or presence of the reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme in the reaction mixture, respectively.

We first analyzed the genetic organization and promoters of the fab-acpP locus. Then, we demonstrate that the promoter driving expression of the fabHDG operon (the fabH promoter) is in fact activated directly by FadR and inhibited directly by ppGpp/DksA. We also demonstrate that ppGpp affects the activity of FadR indirectly by inhibiting the fadR promoter. Our results support the conclusion that FadR is a global regulator of lipid metabolism, activating multiple operons responsible for fatty acid synthesis in E. coli. In addition, the involvement of ppGpp in the control of fabHDG transcription links fatty acid metabolism not only to the availability of fatty acids but also to the status of protein synthesis in the cell, emphasizing the integration of the synthesis of fatty acids with the synthesis of the cell's other macromolecular building blocks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and chemicals.

Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) medium unless otherwise stated. Plasmids were maintained with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml), or kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Minimal medium consisted of the indicated carbon source plus M9 salts, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 μg/ml vitamin B1, and 0.2% Casamino Acids. Sodium oleate was purchased from Sigma, prepared at 200 mg/ml in 10% NP-40, and then diluted to 2 mg/ml.

Plasmid construction. (i) Transcriptional fusions with gfp.

Gene expression was monitored using transcriptional fusions to gfp on pUA66 or pUA139 plasmids (39). We took advantage of a plasmid library containing nearly all of the intergenic regions from the E. coli chromosome cloned in plasmid pUA66 (39). Transcriptional fusions to the plsX, acpP, fabF, and fadE promoters were from the E. coli promoter library (39), whereas the fabH, yceDp1, and yceDp2 promoters and the yceD-rpmF intergenic region were not included in the library and therefore were constructed independently. Fragments were amplified by PCR with the primer pairs indicated in Table S1 in the supplemental material and purified genomic DNA from MG1655. PCR products were then digested with BamHI and XhoI and cloned into either pUA139 or pUA66, depending on the desired orientation (39).

(ii) Plasmids for protein expression and purification.

The DNA sequence coding for fadR was amplified by PCR on genomic DNA using the oligonucleotides ebm598/599, digested with EcoRI and XhoI, and cloned into pBAD24 (40) digested with EcoRI and SalI to obtain plasmid pBAD-FadR (pEB1210) or into pET-6His-Tev (pEB1188) (41) digested with EcoRI and XhoI to give plasmid pET-6His-Tev-FadR (pEB1209). The DNA sequence coding for fadR-SPA was amplified by PCR on colonies of the EB734 strain using the oligonucleotides ebm598/968, digested with EcoRI and XhoI, and cloned into pBAD24 digested with EcoRI and SalI to obtain plasmid pBAD-FadR-SPA (pEB1502).

(iii) Plasmid templates for in vitro transcription.

Sequences corresponding to the promoter endpoints listed in Table 1 were amplified from the E. coli chromosome by PCR using oligonucleotides containing restriction sites (EcoRI and HindIII) included in the 5′ ends. Fragments were digested and ligated into pRLG770 digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and the resulting clones were sequenced to verify that the correct promoter sequence was inserted.

Table 1.

Plasmidsd

| Lab codea | Name | Descriptionb | Promoter endpointsc | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEB0793 | pJL72 | Ampr Kanr, TAP tag cassette | 45 | |

| pEB0269 | pKD4 | Ampr Kanr | 44 | |

| pEB0267 | pKD46 | ts Ampr, lambda Red genes | 44 | |

| pEB0266 | pCP20 | ts Cmr Ampr, FLP recombinase gene | 47 | |

| pMSB1 | Cloning vector for lambda recombination | 49 | ||

| pEB0227 | pBAD24 | Ampr, ColE1 replication origin, PBAD promoter | 40 | |

| pEB1210 | pBAD-FadR | PCR ebm598/599 EcoRI/XhoI in pBAD24 (EcoRI/SalI) | This work | |

| pEB1502 | pBAD-FadR-SPA | PCR ebm598/968 on EB734 EcoRI/XhoI in pBAD24 (EcoRI/SalI) | This work | |

| pEB1188 | pET-6His-Tev | Ampr, T7 promoter, N-terminal 6His-Tev | 41 | |

| pEB1209 | pET-6His-Tev-FadR | PCR ebm598/599 EcoRI/XhoI in pEB1188 | This work | |

| pEB0898 | pUA66 | Kanr p15A ori, transcriptional fusion gfp | 39 | |

| pEB1301 | pUA-yceDp1 | PCR ebm569/689 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −86/+26 | This work |

| pEB1299 | pUA-yceDp2 | PCR ebm690/570 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −129/+4 | This work |

| pEB1183 | pUA-rpmF | PCR ebm567/568 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | This work | |

| pUA-plsX | 39 | |||

| pEB1179 | pUA-fabH | PCR ebm553/554 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −230/+52 | This work |

| pEB1298 | pUA-fabHmut | PCR mutagenesis ebm625/626 on pEB1179 | This work | |

| pUA-acpP | −250/+104 | 39 | ||

| pUA-fabF | 39 | |||

| pEB1235 | pUA-fabA | PCR ebm632/633 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −265/+100 | This work |

| pEB1386 | pUA-fabB | PCR ebm638/635 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −188/+67 | This work |

| pUA-fadE | −176/+141* | 39 | ||

| pEB1234 | pUA-fadR | PCR ebm630/631 XhoI/BamHI in pUA66 | −256/+75 | This work |

| pRLG770 | Transcription vector | 69 | ||

| pRLG9890 | pRLG770 containing the fabH promoter | −100/+50 | This work | |

| pRLG9885 | pRLG770 containing the fabA promoter | −113/+50 | This work | |

| pRLG9886 | pRLG770 containing the fabB promoter | −100/+50 | This work | |

| pRLG10026 | pRLG770 containing the fadR promoter | −100/+50 | This work |

Lab codes correspond to our stock numbering. Transcriptional fusions from the E. coli promoter library (39) do not have lab codes.

The characteristics are given only for the vectors or the reference plasmids that are highlighted in gray shading.

For the characterized promoters, the limits of the transcriptional fusions are indicated respective to the +1 transcription start site. The asterisk indicates that the fadE promoter has not been mapped experimentally. In this case, the limits are calculated from the predicted +1 start site given in Ecocyc. For the inactive fusions, refer to reference 39 or the indicated PCR primers for the limits of the constructions.

Abbreviations: ts, thermosensitive; Ampr, Cmr, and Kanr, genes coding for ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and kanamycin resistance, respectively.

Strain construction.

Deletion mutant strains were obtained from the Keio collection (42) (Table 2). Sequential peptide affinity (SPA)-tagged strains were available from the collection of tandem affinity purification (TAP) or SPA strains that have served for the tandem affinity purification-based description of the E. coli interactome (43), distributed by Open Biosystems. TAP or protein A (ProtA) strains were constructed by recombination of linear DNA cassettes obtained by PCR from pJL72 (44, 45). For both tagged and deletion strains, the recombinant genes were transferred to the wild-type MG1655 genetic background by P1 transduction (46). When required, the gene for resistance to kanamycin was removed using the pCP20 plasmid (47), so that transformation could be performed with transcriptional fusion plasmids carrying kanamycin resistance.

Table 2.

E. coli K-12 strainsa

| Lab code | Name | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EB509 | BW25113ΔfadR::Kanr | Keio collection; Kanr | 42 |

| EB508 | BW25113ΔfabR::Kanr | Keio collection; Kanr | 42 |

| EB572 | DY330_fabH-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) fabH-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB573 | DY330_fabD-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) fabD-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB574 | DY330_fabG-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) fabG-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB576 | DY330_fabF-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) fabF-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB575 | DY330_acpP-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) acpP-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB723 | DY330_fadR-SPA | ΔlacU169 gal490 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) fadR-SPA-Kanr | 43 |

| EB021 | CF4943 | ΔrelA251 spoT203 Tetr | 70 |

| EB072 | BL21(DE3)pLysS | 71, 72 | |

| MG1655 | Wild-type E. coli K-12 | 73 | |

| EB586 | ΔfadR° | P1 transduction from EB509 in MG1655; Kanr marker removed with pCP20 | This work |

| EB584 | ΔfabR° | P1 transduction from EB508 in MG1655; Kanr marker removed with pCP20 | This work |

| EB421 | ΔrelA° | MG1655 ΔrelA without antibiotic resistance | 41 |

| EB425 | ΔrelA°ΔspoT207 | MG1655 spoT207::Camr ΔrelA | 41 |

| EB544 | ΔrelA°spoT203 | Tetr-P1 transduction from CF4943 in EB421 | This work |

| EB559 | ΔdksA° | MG1655ΔdksA without antibiotic resistance | 41 |

| EB598 | ΔdksA°ΔfadR° | P1 transduction from EB509 in EB559; Kanr marker removed with pCP20 | This work |

| EB607 | MG_fabH-SPA | P1 transduction from EB572 in MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB876 | MG_fabH-SPA° | Kanr marker removed from EB607 with pCP20 | This work |

| EB609 | ΔfadR°fabH-SPA | P1 transduction from EB572 to EB586; Kanr | This work |

| EB413 | ΔplsX°_fabH-SPA | PCR ebm1095/256 on pEB269 recombined in EB876; Kanr marker removed with pCP20 | This work |

| EB730 | MG_fabD-SPA | P1 transduction from EB573 to MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB731 | MG_fabG-SPA | P1 transduction from EB574 to MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB606 | MG_fabF-SPA | P1 transduction from EB576 to MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB742 | MG_acpP-SPA | P1 transduction from EB575 to MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB734 | MG_fadR-SPA | P1 transduction from EB723 to MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB649 | MG_YceD-TAP | PCR ebm661/662 on pJL72 recombined in MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB755 | MG_RpmF-ProtA | PCR ebm915/916 on pJL72 recombined in MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| EB098 | MG_PlsX-TAP | PCR ebm255/256 on pJL72 recombined in MG1655; Kanr | This work |

| VH1000 | MG1655 pyrE+ lacZ lacI | 48 | |

| EB845 | fabA-lacZ | fabA-lacZ lysogen of VH1000 | This work |

| EB846 | fabB-lacZ | fabB-lacZ lysogen of VH1000 | This work |

| EB850 | fabH-lacZ | fabH-lacZ lysogen of VH1000 | This work |

| EB870 | fabA-lacZΔfadR | P1 transduction from EB509 to EB845 | This work |

| EB871 | fabB-lacZΔfadR | P1 transduction from EB509 to EB846 | This work |

| EB872 | fabH-lacZΔfadR | P1 transduction from EB509 to EB850 | This work |

| EB858 | fabA-lacZΔdksA | P1 transduction from RLG8124 to EB845 | This work |

| EB863 | fabH-lacZΔdksA | P1 transduction from RLG8124 to EB850 | This work |

The ° character after a strain name means that the kanamycin cassette was removed using the pCP20 plasmid. Tetr, Camr, and Kanr, genes coding for tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and kanamycin resistance, respectively. The two wild-type strains are highlighted in gray shading.

Endpoints of the promoter fragments used to make lacZ fusions are the same as those for the in vitro transcription assay (Table 1) and numbered relative to the transcription start site. Promoter fragments were amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR from strain VH1000 (48), an MG1655 derivative lacking lacZ, and cloned into plasmid pMSB1 (49). All promoter-lacZ fusions were then inserted into phage λRS468 using an in vivo recombination method (49), the fusions were introduced by infection into VH1000, lysogens were identified on LB plates containing 40 μg/ml X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate), and single-copy λ lysogens were chosen for analysis. Lysogens containing the ΔdksA::tetR or ΔfadR::kanR allele were obtained by transduction with phage P1vir grown on donor strain RLG8124 (50) or EB509, respectively.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

Total RNAs were prepared using the PureYields RNA Midiprep system from Promega, on 10 ml of a culture of MG1655 cells grown at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.3. Reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed using the Access RT-PCR system from Promega.

Transcriptional fusions with gfp and with lacZ.

The MG1655 wild-type E. coli strain or isogenic mutant strains were transformed with plasmids carrying the gfp transcriptional fusions (39) and maintained with kanamycin. For cotransformation, compatible plasmids (pBAD24 and derivatives) were used and ampicillin was added. Selection plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Six hundred microliters of LB medium supplemented with required antibiotics, and with arabinose (0.05% or 0.0001%) when necessary for pBAD-driven expression, was inoculated (3 to 6 independent clones for each assay, as indicated in the figure legends), and strains were grown at 30°C in 96-well polypropylene plates with 2.2-ml wells under aeration and agitation. Fluorescence intensity measurements were performed in a Tecan Infinite M200 reader. One hundred fifty microliters of each well was transferred into a black Greiner 96-well plate for reading absorbance at 600 nm and fluorescence (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 530 nm). The expression levels were calculated by dividing the intensity of fluorescence by the absorbance at 600 nm. The background measured with cells transformed with the pUA66 control was then subtracted, except in Fig. 1B. These results are given in arbitrary units (AU) because the intensity of fluorescence is acquired with a variable gain and hence varies from one experiment to the other.

VH1000 lysogens carrying lacZ transcriptional fusions on lambda prophages were grown in 600 μl LB at 30°C in 96-well polypropylene plates with 2.2-ml wells under aeration and agitation, and β-galactosidase activities were assayed as described previously (51).

FadR purification.

The BL21(DE3)pLysS strain was transformed with plasmid pET-6His-Tev-fadR (pEB1209). The strain was grown in 500 ml LB at 30°C. At an OD600 of 0.9, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added and the cultures were incubated for 6 h at 23°C. After pelleting, the cells were broken by sonication in 10 ml of buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole, 0.2% NP-40) and the extract was then centrifuged for 30 min at 27,000 × g before incubation on 500 μl of Talon beads (Clontech) on a wheel for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with 15 ml buffer 1, then with 5 ml buffer 1 with 1 M NaCl, and finally with 10 ml buffer 1. Proteins were eluted in 5 steps of 500 μl of buffer 1 containing 200 mM imidazole. The fractions containing the purified FadR protein were pooled, concentrated, and dialyzed in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The final protein concentration determined by a Bradford assay was about 2 mg · ml−1 (70 μM).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE, electrotransfer onto nitrocellulose membranes, and Western blot analyses were performed as previously described (52). TAP and ProtA tags were detected with the PAP antibody from Sigma. Monoclonal anti-Flag M2 was also purchased from Sigma.

DNase I footprinting.

Plasmid pRLG9890 (containing a fabH promoter fragment, endpoints −100 to +50) was digested with HindIII (NEB), end labeled by filling in with [α-32P]dATP (Perkin-Elmer) using Sequenase (USB), and digested with AatII (NEB). The DNA was purified after each step by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. The fabH promoter fragment (labeled on the template strand) was excised from a 5% acrylamide gel, purified using an Elutip-D (Whatman), ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 100 μl 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9.

FadR at the indicated concentrations, 15 nM RNAP, or both (or FadR and RNAP storage buffers) were added to ∼0.2 nM template DNA in transcription buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 μg/μl bovine serum albumin [BSA]) for 10 min at 37°C. One microliter of DNase I (to a final concentration of 0.25 μg/ml) was added for 30 s, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 10 mM EDTA, 0.3 M sodium acetate, and phenol. Glycogen was added to the aqueous fraction, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol, washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and suspended in 4 μl loading buffer (7 M urea, 0.5× Tris-buffered EDTA [TBE], 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol). Control reactions were performed without DNase I and RNAP ± FadR (data not shown). Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 7 M urea-9% polyacrylamide gel and quantified by phosphorimaging.

In vitro transcription.

Single-round in vitro transcription assays were performed essentially as described previously (50) using Eσ70 RNAP (2 nM) and supercoiled plasmid templates (1 nM). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 min and contained 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8); 60 mM NaCl; 10 mM MgCl2; 1 mM DTT; 0.1 mg · ml−1 BSA; 200 mM ATP, CTP, and GTP; 10 mM UTP; ∼1 mCi [α-32P]UTP. Heparin (10 μg · ml−1) was added with the nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) as a competitor to prevent reinitiation. Samples were electrophoresed on a 7 M urea-6% polyacrylamide gel and quantified by phosphorimaging.

Acyl-CoAs used for in vitro transcription reactions were synthesized by ligating octanoate and palmitate with coenzyme A. Fatty acid (0.5 mM) and CoA (1 mM) (purchased from Sigma) were added to a reaction buffer containing 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM MgATP. A 10 μM concentration of enzyme Rpa1702 (FcsA) (53) was added to catalyze the ligation, and 0.2 mM pyrophosphatase was added to degrade the released pyrophosphate (a competitor of transcription). The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 60 min. Then, FadR was preincubated at 37°C for 10 min with the products of the reaction, with acyl-CoAs estimated to be 10-fold in excess of FadR. The equivalent of 2 μM FadR with or without acyl-CoA, 2 μM DksA, and/or 100 mM ppGpp (TriLink) was added to the transcription reaction mixture where indicated.

RESULTS

Transcription of the fab-acpP locus.

In order to study expression of the genes in the fab-acpP locus, we used transcriptional fusions to the sequence coding for GFPmut2 on the low-copy-number plasmid pUA66 (39), allowing promoter activity to be monitored by fluorescence (see Materials and Methods for details). This GFPmut2 variant becomes fluorescent less than 5 min after its expression is initiated, and it is highly stable in E. coli. Seven potential promoter regions (thick lines beneath the schematic in Fig. 1A) were examined as fusions to green fluorescent protein (GFP), by amplifying DNA fragments upstream from rpmF, plsX, acpP, fabF, and fabH (which is located within the plsX coding sequence), as well as two fragments upstream of yceD (yceDp1 and yceDp2). Only four of the seven transcriptional fusions (yceDp1, yceDp2, fabH, and acpP) resulted in expression significantly above the background level measured with the control plasmid pUA66 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that these 4 promoters account for expression of the entire locus, consistent with previous reports (36, 38). In addition, in order to confirm that the genes were indeed expressed cotranscriptionally, we performed RT-PCR experiments on total RNA from exponentially growing wild-type cells. Using oligonucleotides amplifying the regions shown in Fig. 1A (lines a to f), it was possible to detect transcripts for pairs of adjacent genes (Fig. 1C). The RT-PCR results were therefore consistent with the operon structure derived from the results with the transcriptional fusions.

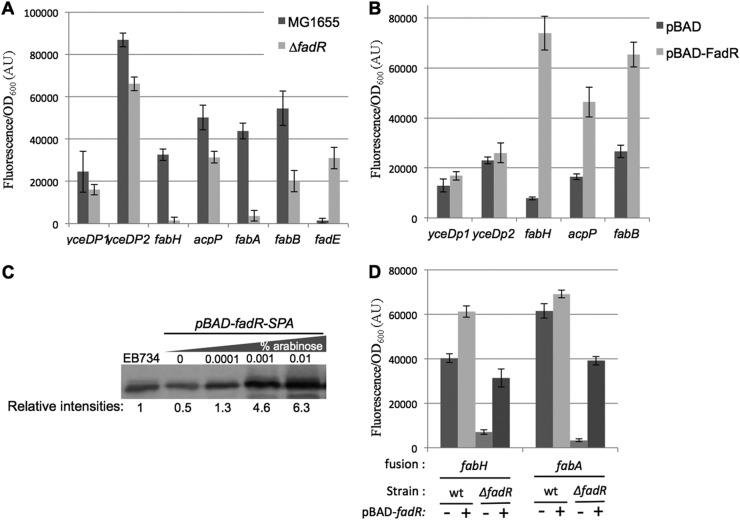

Activation of the fabH promoter by FadR in vivo.

We first checked whether the transcription regulator FadR or FabR regulated the fab-acpP locus by measuring expression from the 4 promoters yceDp1, yceDp2, fabH, and acpP in ΔfadR and ΔfabR mutants. Transcriptional fusions containing the fabA, fabB, and fadE promoters, previously reported as regulated by FadR or FabR, were used as positive controls (15, 16, 54, 55). As expected, the activities of the fabB and fabA promoters declined in the ΔfadR mutant, whereas the fadE promoter was strongly stimulated by the absence of fadR (Fig. 2A). In the fab-acpP locus, the activity of the fabH promoter was strongly decreased in the ΔfadR mutant, similar to the effect observed on fabA and fabB. The activities of the acpP and yceDp2 promoters decreased by a smaller, but significant, amount, and the yceDp1 promoter was affected little if at all. The ΔfabR mutation had no effect on the expression of the promoters of the fab-acpP locus, but it induced the fabA- and fabB-GFP fusions (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), consistent with previous reports utilizing lacZ transcriptional fusions (18).

Fig 2.

FadR activates the fabH promoter. (A) MG1655 and ΔfadR (EB586) strains were transformed by the indicated transcriptional fusions with gfp. Relative fluorescence intensities of 4 independent clones grown at 30°C in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin were measured in log phase. (B) The MG1655 strain was transformed by both the indicated transcriptional fusions with gfp and either the control pBAD24 plasmid or pBAD-FadR (pEB1210). Relative fluorescence intensities were measured after overnight growth at 30°C in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 0.05% arabinose (see Materials and Methods). (C) The amounts of FadR-SPA protein produced in EB734 strain and in MG1655 transformed by pBAD-fadR-SPA (pEB1502) were compared by Western blotting using an anti-Flag antibody and fluorescent secondary antibodies. The intensities of the bands were then quantified with a fluorescent imager (Li-Cor). The results normalized to the EB734 strain are indicated below the gel. (D) MG1655 and ΔfadR (EB586) strains were transformed by both the fabH or fabA transcriptional fusions with gfp and either the control pBAD plasmid or pBAD-FadR (pEB1210). Relative fluorescence intensities of 6 independent clones were measured after overnight growth at 30°C in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 0.0001% arabinose. wt, wild type.

These results suggested that FadR activates transcription of fabH. FadR binds DNA as an apoprotein, and it is released when it binds long-chain acyl-CoA (8). Therefore, we predicted that artificial overproduction of FadR from an arabinose-inducible plasmid construct, pBAD-fadR (pEB1210), might increase expression of promoters activated by FadR. Indeed, transcription from the fabH and acpP promoters increased strongly, similarly to the fabB control (Fig. 2B), consistent with the results obtained in the ΔfadR mutant (Fig. 2A).

We next performed Western blotting assays on the FabH, FabD, and FabG enzymes fused at their C termini to TAP or SPA tags (recognized by anti-protein A or anti-Flag antibodies, respectively; see Materials and Methods for construction of strains with tagged proteins) in order to determine whether effects of FadR on fabH promoter activity resulted in changes in protein production from the fabH operon, as well as effects on transcription. In these strains, the tags were encoded at the 3′ end of the chromosomal open reading frames (ORFs), permitting the production of recombinant tagged proteins from the native promoters.

When FadR was produced by induction of the pBAD promoter, the amounts of the FabH- and FabD-tagged proteins increased more than 3-fold, although the FabG- and FabF-tagged proteins increased by only 40% and 70%, respectively (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). As expected, there was no effect of FadR on production of the YceD-, RpmF-, or PlsX-tagged proteins encoded by genes upstream from the fabH promoter (see Fig. S2A).

To confirm that the increase in the FabH-SPA protein was the direct consequence of activation of the fabH promoter by FadR, we deleted the plsX gene in the FabH-SPA strain, thereby eliminating the fabH promoter (which is located in the plsX open reading frame). Although some FabH-SPA protein was still produced in the ΔplsX strain (see Fig. S2B and its legend in the supplemental material), probably because fabH was expressed by read-through transcription from the relatively strong yceDp1 and yceDp2 promoters (see also references 35 and 36), FadR expression did not increase FabH-SPA production in this construct (see Fig. S2B). This is consistent with the interpretation that the increase in FabH protein produced in the context of the wild-type locus derived from activation of the fabH promoter by FadR.

The amount of arabinose used in the above-described experiments (0.05% or 0.5%) resulted in FadR overproduction. To address whether FadR produced at physiological levels in trans could complement a ΔfadR mutant for fabH expression, we calibrated the concentration of arabinose needed to express FadR with a SPA tag from a pBAD expression plasmid (pEB1502). For comparison, we used a strain in which FadR with the same SPA tag was expressed at the native chromosomal locus (EB734) from the native fadR promoter. The amount of FadR-SPA produced from the pBAD plasmid using 0.0001% arabinose was similar (within 1.5-fold) to that produced in the strain with the tagged protein expressed at the native locus (Fig. 2C). Consistent with this observation, in the presence of 0.0001% arabinose, expression of the fabH and fabA transcriptional fusions with the pBAD-fadR plasmid in the ΔfadR strain was similar to that observed when FadR was produced from the bacterial chromosome (Fig. 2D).

Utilization of GFP transcriptional fusions on the low-copy-number plasmid pUA66 permits analysis of a large number of experiments (39, 56). However, to rule out effects from potential changes in plasmid copy number, we also confirmed our conclusions using lacZ-transcriptional fusions on the bacterial chromosome. The relative effects of the ΔfadR mutation, or of overproduction of FadR, on expression of the fabH-lacZ transcriptional fusions were qualitatively similar to those obtained with the plasmid-encoded GFP fusions (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). The fabA and fabB promoters were also affected by the deletion of fadR, as described previously (15, 16).

FadR is inactivated by long-chain fatty acids after their conversion to acyl-CoA by the acyl-CoA synthase FadD upon import into the cell, releasing ligand-bound FadR from the DNA (8). Therefore, we predicted that the fabH promoter would be shut off by the long-chain fatty acid oleate. As with the control fabA promoter, the fabH promoter was inhibited when grown in oleate compared with when it was grown in acetate or glucose (Fig. 3). In contrast, fadE promoter activity increased in response to oleate. The activation of fabH expression by FadR and its inhibition by oleate suggest that FadR activates the fabH promoter in the absence of long-chain fatty acids.

Fig 3.

Long-chain acyl-CoA inhibits the fabH promoter. The MG1655 strain was transformed by the fadE, fabA, or fabH transcriptional fusions with gfp. Relative fluorescence intensities of 4 independent clones for each assay were measured in log-phase cells, grown at 30°C in minimal medium containing either 0.2% acetate, 0.2% glucose, or 0.2% oleate as the sole carbon source.

FadR binding to the fabH promoter and stimulation of transcription initiation in vitro.

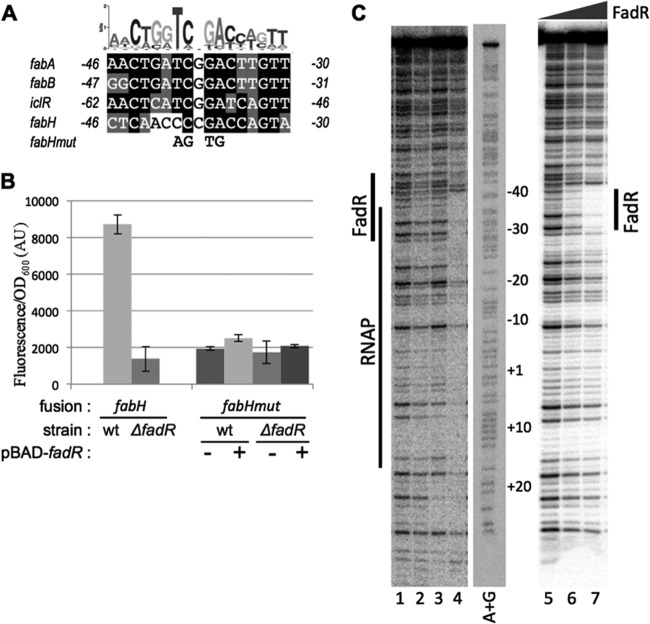

The fabH promoter does not have a canonical −35 hexamer (32), which is not unusual for promoters utilizing activators. Visual inspection of the fabH promoter sequence identified a weak match of the DNA region between positions −30 and −46 to FadR binding sites upstream of the fabA, fabB, and iclR promoters, three other promoters activated by FadR (15, 16, 57) (Fig. 4A). This position of the FadR binding site relative to the transcription start site is similar among the fabA, fabB, and fabH promoters (Fig. 4A). Mutations in the FadR site upstream of the fabH promoter reduced transcription to the level observed in a ΔfadR mutant, in the presence or absence of FadR (Fig. 4B), consistent with the model that FadR activates the fabH promoter directly.

Fig 4.

FadR binding site on fabH promoter. (A) The putative FadR binding site in the fabH promoter is aligned with the sequences of the FadR binding site in fabA, fabB, and iclR promoters described previously (15, 16, 57). The limits of the binding site are indicated relative to the transcription start site. The logo computed for the FadR binding site in Enterobacteriales (6) is shown on top. The mutations introduced in the fabHmut-gfp fusion (pEB1298) are indicated below the alignment. (B) MG1655 and ΔfadR (EB586) strains were transformed by both the indicated transcriptional fusions with gfp and either the control pBAD plasmid or pBAD-FadR (pEB1210). Relative fluorescence intensities of 6 independent clones were measured after overnight growth at 30°C in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 0.05% arabinose. (C) Footprint of FadR and RNAP on the promoter of fabH. Labeled fabH template was incubated with FadR, RNAP, or both FadR and RNAP and subjected to DNase I footprinting assay. Lanes: 1, template alone; 2, 1 μM FadR; 3, 15 nM RNAP; 4, 1 μM FadR plus 15 nM RNAP; 5, template alone; 6, 500 nM FadR; 7, 1 μM FadR. The positions are indicated relative to the +1 transcription start site, using an adjacent A+G sequence ladder (A+G lane). The deduced positions of FadR and RNAP protection are indicated next to the gel images. Lane 2 is somewhat underloaded, but normalization of the profiles confirmed that there was little protection by FadR alone in the region corresponding to the position of the predicted FadR binding site.

To address whether the effect of FadR on the fabH promoter was a direct effect of FadR binding to the predicted site, we purified FadR as a 6His-tagged recombinant protein and DNase I footprint assays were performed (see Materials and Methods). We incubated an end-labeled DNA fragment corresponding to −100/+50 from the fabH promoter region with purified 6His-Tev-FadR in the presence or absence of native RNAP (58) and treated the complex with DNase I (see Materials and Methods). In most experiments, little or no protection was observed in the presence of FadR alone (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 1 and 2). In the presence of RNAP alone (lane 3), again little or no protection was observed. However, in the presence of both FadR and RNAP, strong protection was observed in the region typically recognized by RNAP (∼−40 to +20; Fig. 4C, lane 4) as well as in the putative FadR site. Protection was observed with FadR alone in some experiments in the region corresponding to the predicted FadR binding sequence (∼−31 to ∼−44) (Fig. 4C, lane 7). The position of RNAP in the DNase I footprints (Fig. 4C) further supported our identification of the location of the fabH promoter, as did the decrease in promoter activity observed from mutations in the putative −10 hexamer (data not shown).

Taken together, the position of the FadR binding site with respect to the binding site for RNAP suggests a model in which FadR activates transcription directly by binding to the DNA cooperatively with RNAP, helping to recruit the transcription complex to the fabH promoter. Direct activation by transcription factors bound adjacent to the −35 region usually involves interactions between the activator and either the C-terminal domain of the sigma subunit or the N-terminal domain of the alpha subunit (59).

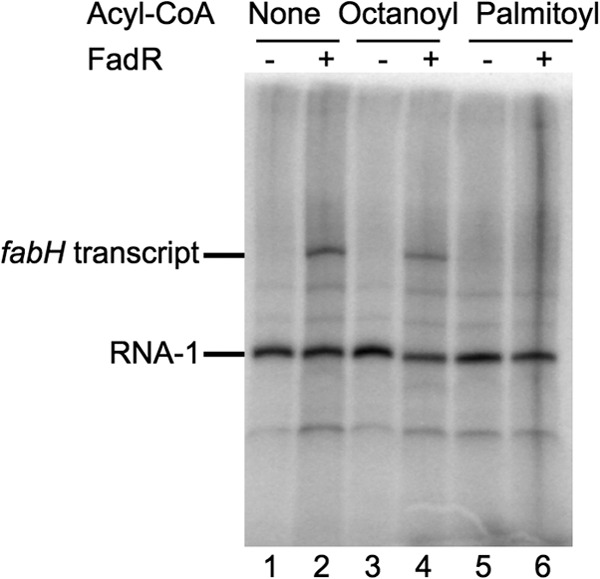

In order to address whether FadR is necessary and also sufficient for activation of transcription, we performed in vitro transcription assays on the fabH promoter. No fabH-specific transcript was detected in the absence of FadR (Fig. 5, lane 1), but a transcript of the expected length (∼200 nucleotides) was obtained in the presence of FadR (lane 2). Thus, RNAP and FadR are sufficient for transcription from the fabH promoter. Because binding of acyl-CoA with a chain length longer than 12 carbons prevents FadR from binding to DNA (8), we tested the effect of acyl-CoA on fabH transcription in vitro. Addition of short-chain acyl-CoA (octanoyl-CoA) to the reaction mixture did not inhibit activation by FadR (lane 4), whereas fabH transcription was eliminated by addition of long-chain acyl-CoA (palmitoyl-CoA) (lane 6). We conclude that binding of long-chain acyl-CoA inhibits FadR-dependent activation of fabH transcription.

Fig 5.

The fabH promoter is activated by FadR in vitro. Single-round in vitro transcription from the fabH plasmid template in the presence or absence of 2 μM FadR, together with octanoyl-CoA or palmitoyl-CoA. The plasmid-derived RNA-1 transcript served as a loading control.

To address whether the concentrations of FadR used in the in vitro experiments were in the physiologically significant range, we compared the intensities of the Western blot signals from FadR-SPA- and ACP-SPA-tagged proteins expressed from their wild-type promoters on the chromosome (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Our estimate of FadR-SPA in log phase was about 60-fold lower than that of ACP-SPA (see Fig. S4). Since the ACP amount has been estimated as 60,000 copies per cell (60), this puts FadR levels on the order of 1,000 molecules per cell, corresponding to ∼1 to 2 μM. Although there may be errors in this estimate because of the use of tagged proteins and an overestimate of ACP, we think it is likely that native FadR concentrations in vivo are in the range used in our in vitro experiments.

In summary, our results in vitro (Fig. 4 and 5) and in vivo (Fig. 2 and 3) demonstrate that FadR directly activates transcription from the fabH promoter and that activation is regulated by long-chain acyl-CoA.

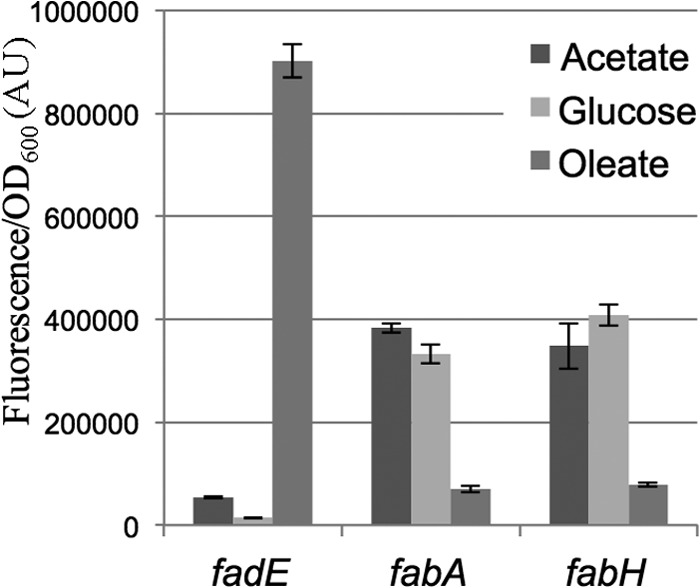

Regulation of fabH expression by ppGpp/DksA.

It was reported previously that the expression of fabH was inhibited during the stringent response (32). fabHDG gene expression was also downregulated by ppGpp induction in a genome-wide transcriptome study (34). However, these in vivo studies did not demonstrate that the observed regulation of the fabH promoter by ppGpp was direct.

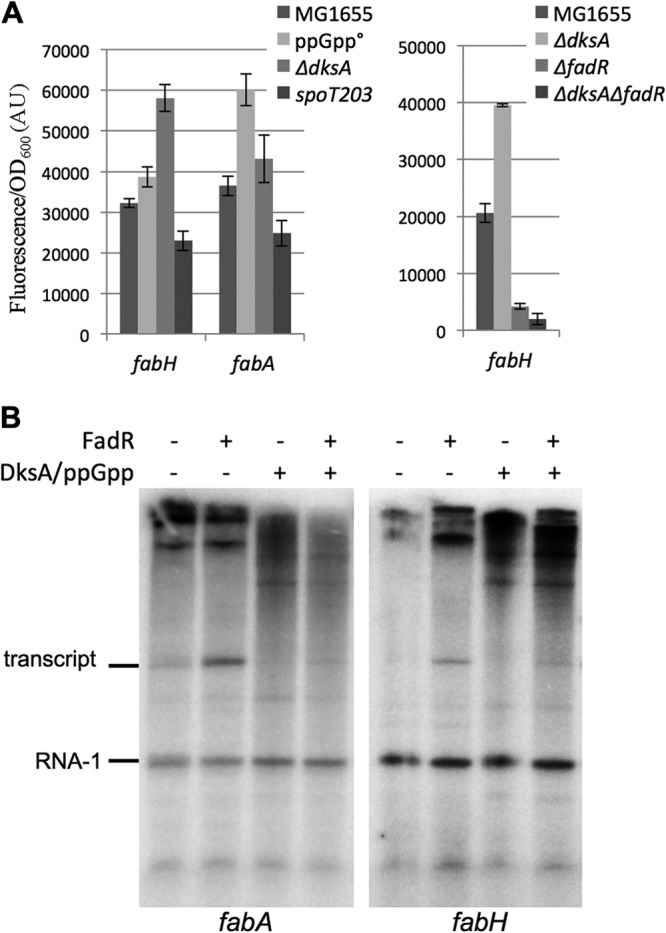

We compared the activities of the fabH promoter-gfp transcriptional fusion in a wild-type strain and in an isogenic ΔrelA ΔspoT strain (EB425, which lacks the two ppGpp synthase activities) (22), in a ΔdksA strain (EB559, which lacks the ppGpp cofactor DksA) (50), and in a spoT203 strain (EB544, which accumulates ppGpp) (61). The activity of the fabH promoter increased modestly but reproducibly in the ΔrelA ΔspoT mutant, it increased to a greater extent in the ΔdksA mutant, and it decreased in the spoT203 strain (Fig. 6A, left panel), consistent with the negative regulation of this operon by ppGpp proposed previously (32) and with the requirement for DksA for regulation by ppGpp (50). Similar conclusions were reached from analysis of the fabH-lacZ and fabA-lacZ transcriptional fusions in wild-type versus ΔdksA strains (see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material). We note that the effects of the ΔrelA ΔspoT mutant and the ΔdksA mutant on the fabH promoter are qualitatively similar to the effects of these mutants on rRNA promoters (50, 62, 63).

Fig 6.

Regulation of fabH by ppGpp. (A) MG1655, ΔrelA ΔspoT (ppGpp°, EB425), ΔdksA (EB559), ΔrelA spoT203 (spoT203, EB544), ΔfadR (EB586), and ΔdksA ΔfadR (EB598) strains were transformed by fabH or fabA transcriptional fusions with gfp. Relative fluorescence intensities of 4 independent clones, grown in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C for each assay, were measured in log phase. (B) Single-round in vitro transcription from the fabH and fabA plasmid templates in the presence or absence of 2 μM FadR, 2 μM DksA, and 100 mM ppGpp. The plasmid-derived RNA-1 transcript served as a loading control.

The effect of DksA on the fabH promoter was also examined in the absence of fadR (Fig. 6A, right panel). As expected, fabH promoter activity was very low in the ΔfadR single mutant and in the ΔdksA ΔfadR double mutant strain. This result is consistent with the model that ppGpp/DksA inhibits RNAP that has been recruited to the promoter by FadR.

To address whether the effects of ppGpp and DksA on the fabA and fabH promoters were direct, we measured their effects on transcription in vitro (Fig. 6B). FadR was required for fabH and fabA promoter activity, as shown above (Fig. 5), and transcription from the FadR-activated fabH and fabA promoters was inhibited by ppGpp/DksA. ppGpp/DksA did not affect transcription from the RNA-1 promoter also encoded by the plasmid (Fig. 6B). Thus, regulation by ppGpp/DksA is direct and specific.

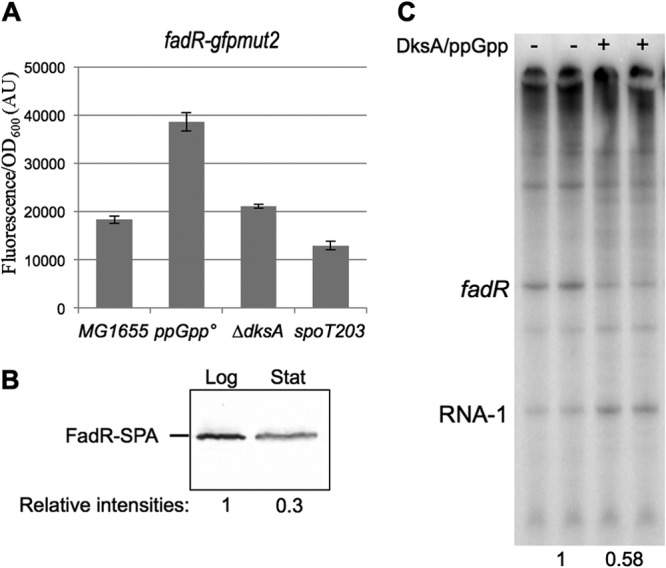

Because the above results did not rule out that ppGpp/DksA might also regulate fabH indirectly by inhibiting expression of fadR, we tested the effects of ppGpp and DksA on transcription from the fadR promoter in vivo and in vitro. The activity of the fadR-gfp fusion increased substantially in the ΔrelA ΔspoT strain and slightly in the ΔdksA mutant, and it decreased modestly in the spoT203 mutant (Fig. 7A), consistent with regulation of the fadR promoter by ppGpp/DksA. We also found that the level of a SPA-tagged FadR protein decreased about ∼3-fold upon entry of cells into stationary phase (when ppGpp levels increase) (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, ppGpp/DksA decreased fadR promoter activity about ∼2-fold in an in vitro transcription assay (Fig. 7C). Therefore, ppGpp inhibits fadR expression directly. Taken together, the data suggest that regulation of fabH expression by ppGpp/DksA occurs both directly by modulation of fabH promoter activity and indirectly by modulation of FadR levels.

Fig 7.

Regulation of fadR expression. (A) MG1655, ΔrelA ΔspoT (ppGpp°, EB425), ΔdksA (EB559), and ΔrelA spoT203 (spoT203, EB544) strains were transformed by the fadR transcriptional fusions with gfp. Relative fluorescence intensities of 6 independent clones were measured after growth overnight in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C. (B) Strain EB734 producing FadR-SPA was grown at 37°C in LB. Equal amounts of total cell extracts prepared at an OD600 of 0.5 (Log) or after growth overnight (Stat) were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-Flag antibody. The Western blot was then analyzed with fluorescent secondary antibodies and a fluorescent imager (Li-Cor) in order to quantify the relative intensities of log- and stationary-phase bands. (C) Single-round in vitro transcription from the fadR plasmid template in the presence or absence of 2 μM DksA and 100 mM ppGpp. The plasmid-derived RNA-1 transcript served as a loading control. The intensities of the bands quantified and normalized to the assay without DksA/ppGpp are indicated below the gel.

DISCUSSION

FadR activates fabH when long-chain acyl-CoA concentrations are low.

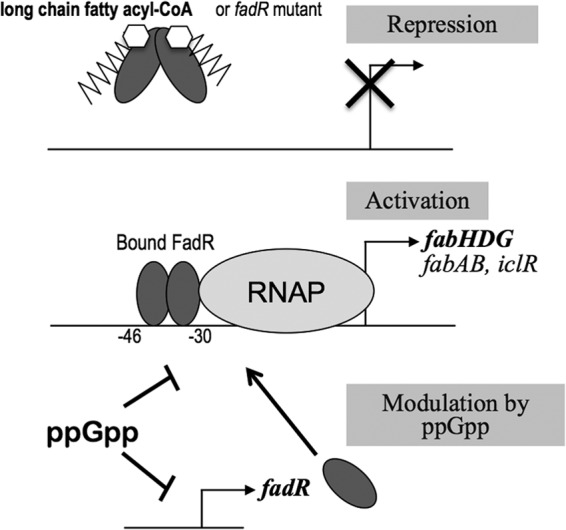

In addition to its role as a repressor of the fatty acid degradation genes in E. coli, FadR was shown previously to activate the fabA and fabB genes required for biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (8). Here, we report that FadR also activates the expression of fabHDG genes, which code for enzymes involved in saturated fatty acid synthesis, and that this activation is reversed by the binding of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA (Fig. 8). These results are in accord with, and provide an explanation for, a recent observation that overproduction of FadR can enhance the production of free fatty acids both saturated and unsaturated, in strains engineered for biofuel production (19). Moreover, Zhang and colleagues reported that overexpression of FadR increased expression of many genes in the fatty acid synthesis pathway, including fabH (19).

Fig 8.

Model for regulation of fabH promoter by FadR. The fabA, fabB, iclR, and fabH genes are similarly regulated. A dimer of FadR binds the fabH promoter between −30 and −46 relative to the transcription start site. It recruits RNAP and activates transcription (middle). Binding of long-chain acyl-CoA results in conformational modification of FadR, which prevents DNA binding, and as a consequence, the transcription is shut down (top). ppGpp directly inhibits the fabH promoter (and fabA and potentially other fab promoters) and the fadR promoter. As a consequence, lower levels of FadR proteins also diminish the transcription from the fabH promoter (bottom).

Further analysis of the results from genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the FadR regulon (16, 54) will be needed to identify the full complement of genes that are directly activated or inhibited by FadR. Our results demonstrate that the effect of FadR on expression of fabHDG is direct. FadR also increased the activity of the acpP promoter in vivo, although to a lesser extent than that for fabH (Fig. 2), but further studies will be needed to determine whether the effect of FadR on this promoter is direct. A potential FadR binding sequence upstream of acpP was reported previously (37). However, those authors concluded that effects of FadR on the acpP promoter might be indirect, because FadR-DNA complexes were not detected in band shift experiments. Our experience with the fabH promoter suggests that the FadR-DNA complex may be short lived, but interactions between RNAP and FadR increase its longevity. Weak binding of FadR on the fabI promoter has also been reported previously (3).

The direct control of fab genes by transcriptional regulators that sense the availability of fatty acids may be widespread in bacteria. Activation of a fab operon by FasR in Streptomyces coelicolor (14) bears some similarity to the activation of fabHDG by FadR described here for E. coli. Bacillus subtilis fab gene expression is also controlled by a transcription factor responsive to fatty acid levels, in this case, a repressor that responds to malonyl-CoA or malonyl-ACP (11). It was also reported recently that FadR inhibits a new target involved in phospholipid synthesis in Vibrio cholerae (64). Studies performed in other species will likely suggest further potential regulatory targets of FadR in E. coli in the future.

fabD and fabG are essential genes (37), but fabH is not essential (65). However, ΔfabH mutants display severe defects in growth, whereas ΔfadR mutants do not have growth defects (reference 65 and our unpublished results). If FadR is needed to activate the fabH promoter, why do ΔfadR mutants not display the same growth defects as do strains deleted for the genes that it controls? We suggest that the fabH promoter may not be the only contributor to fabH expression under all conditions, that other activators might compensate to activate fabH expression when FadR is absent, and/or that basal expression of the fabHDG genes (either from unactivated fabH core promoter activity or from read-through transcription from the upstream promoters, yceDp1 and -p2) might be sufficient for cells to tolerate the absence of FadR.

Dual control of fabH by FadR and ppGpp/DksA.

Our data demonstrate that the fabH promoter, and fatty acid promoter activity more generally, is subject to the interplay of multiple regulators, including FadR and ppGpp/DksA. Several lines of evidence demonstrated that fabH expression is regulated by ppGpp/DksA: (i) fabH promoter activity increased in ΔrelA ΔspoT or ΔdksA mutants, (ii) fabH promoter activity decreased in a strain overproducing ppGpp, and (iii) ppGpp/DksA specifically reduced transcription from the fabH promoter in vitro (Fig. 6). Consistent with these experimental observations, the fabH promoter contains a G+C-rich discriminator region (32), typical of promoters inhibited by ppGpp (24). We conclude that the fabH promoter is regulated directly by ppGpp/DksA (Fig. 8). This does not rule out possible contributions to regulation of fabHDG gene expression from yet other systems. In this regard, we note that the fabH transcription start site is somewhat distant from the fabH start codon (32), and the long mRNA leader sequence (242 nucleotides) could provide a mechanism for additional modes of regulation.

Our results are in accord with the negative regulation of fabH (and most other fatty acid synthesis genes) observed in transcriptome analyses of the stringent response (34). However, this regulation may be insufficient to explain the total arrest of fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis observed during the stringent response; it has been reported that ppGpp also binds to and inhibits enzymes in these pathways (29), and it was also reported that deletions of the spoT and fabH genes are synthetically lethal (65). There are multiple explanations that might account for this synthetic lethality, and we do not consider this observation inconsistent with the effects of ppGpp/DksA on fabHDG transcription reported here.

“Dual control” of promoter activity by FadR and ppGpp/DksA is observed not only for fabH but also for the fabA promoter (Fig. 6). Presumably, control by the two systems allows cells to demand that two conditions be met for production of fabHDG, namely, the absence of long-chain fatty acids and the presence of a full complement of amino acids (or other nutrients), which is signaled by the concentration of ppGpp. Such dual control of promoters regulated by the ppGpp/DksA system appears to be common. For example, efficient synthesis of the master regulator of the flagellar cascade, FlhDC, requires both the presence of amino acids and the absence of cyclic AMP (cAMP), a sensor of glucose availability (66), and rRNA promoter activity requires both the presence of amino acids and the presence of high NTP concentrations (63).

Our results also suggest that fadR expression itself is inhibited in stationary phase (Fig. 7). A reduced amount of FadR protein might then reduce the expression of other genes activated by FadR, such as fabA, fabB, and iclR, in addition to fabH. A decrease in FadR levels during stationary phase might also contribute to derepression of fad genes that are normally repressed by FadR, e.g., those needed for degradation of fatty acids. Indeed, it has been reported that members of the FadR regulon might be activated in stationary phase (20, 67), and several fad genes have been reported to be upregulated during the stringent response (34). A recent report suggested that free fatty acids might accompany envelope remodeling during stationary phase (68), which might explain derepression of the fad genes. The reduced amount of FadR protein in stationary phase observed in our study, coupled with the increase in ppGpp concentration that occurs upon entry into stationary phase (63) and the resulting effects on FadR synthesis, might also contribute to effects on the FadR regulon (Fig. 8).

Our results suggest that FadR, as well as controlling fatty acid degradation, could directly activate much of the fatty acid synthesis pathway under at least some conditions through its effects on the fabH promoter. It is unclear how this result fits in with other aspects of regulation of this very complicated system, as each component of the network must be considered only one part of a much more complex whole. Deciphering the mechanisms that contribute to downregulation of fatty acid synthesis genes and the upregulation of fatty acid degradation genes at different stages in bacterial growth provides a challenge for the future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was funded by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and by ANR (French National Research Agency) grant LipidStress (ANR-09-JCJC-0018) and by U.S. PHS National Institutes of Health R37 GM37048 (to R.L.G.). L. My is the recipient of an FRM (Medical Research Foundation) fellowship.

We thank Rim Maouche, Patrice Moreau, Jorge Escalante, Heidi Crosby, and Wilma Ross for materials and/or helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00384-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cronan JE, Thomas J. 2009. Bacterial fatty acid synthesis and its relationships with polyketide synthetic pathways. Methods Enzymol. 459:395–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang YM, Rock CO. 2008. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DiRusso CC, Black PN, Weimar JD. 1999. Molecular inroads into the regulation and metabolism of fatty acids, lessons from bacteria. Prog. Lipid Res. 38:129–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsons JB, Rock CO. 2013. Bacterial lipids: metabolism and membrane homeostasis. Prog. Lipid Res. 52:249–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujita Y, Matsuoka H, Hirooka K. 2007. Regulation of fatty acid metabolism in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 66:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kazakov AE, Rodionov DA, Alm E, Arkin AP, Dubchak I, Gelfand MS. 2009. Comparative genomics of regulation of fatty acid and branched-chain amino acid utilization in proteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 191:52–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang YM, Rock CO. 2010. A rainbow coalition of lipid transcriptional regulators. Mol. Microbiol. 78:5–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cronan JE, Subrahmanyam S. 1998. FadR, transcriptional co-ordination of metabolic expediency. Mol. Microbiol. 29:937–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsuoka H, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. 2007. Organization and function of the YsiA regulon of Bacillus subtilis involved in fatty acid degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:5180–5194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gago G, Diacovich L, Arabolaza A, Tsai SC, Gramajo H. 2011. Fatty acid biosynthesis in actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:475–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martinez MA, Zaballa ME, Schaeffer F, Bellinzoni M, Albanesi D, Schujman GE, Vila AJ, Alzari PM, de Mendoza D. 2010. A novel role of malonyl-ACP in lipid homeostasis. Biochemistry 49:3161–3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jerga A, Rock CO. 2009. Acyl-acyl carrier protein regulates transcription of fatty acid biosynthetic genes via the FabT repressor in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 284:15364–15368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salzman V, Mondino S, Sala C, Cole ST, Gago G, Gramajo H. 2010. Transcriptional regulation of lipid homeostasis in mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 78:64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arabolaza A, D'Angelo M, Comba S, Gramajo H. 2010. FasR, a novel class of transcriptional regulator, governs the activation of fatty acid biosynthesis genes in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 78:47–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henry MF, Cronan JE. 1992. A new mechanism of transcriptional regulation: release of an activator triggered by small molecule binding. Cell 70:671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell JW, Cronan JE. 2001. Escherichia coli FadR positively regulates transcription of the fabB fatty acid biosynthetic gene. J. Bacteriol. 183:5982–5990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu K, Zhang YM, Rock CO. 2009. Transcriptional regulation of membrane lipid homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 284:34880–34888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feng Y, Cronan JE. 2011. Complex binding of the FabR repressor of bacterial unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis to its cognate promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 80:195–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang F, Ouellet M, Batth TS, Adams PD, Petzold CJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. 2012. Enhancing fatty acid production by the expression of the regulatory transcription factor FadR. Metab. Eng. 14:653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DiRusso CC, Nystrom T. 1998. The fats of Escherichia coli during infancy and old age: regulation by global regulators, alarmones and lipid intermediates. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merlie JP, Pizer LI. 1973. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in Escherichia coli by guanosine tetraphosphate. J. Bacteriol. 116:355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Potrykus K, Cashel M. 2008. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62:35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ross W, Vrentas CE, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Gaal T, Gourse RL. 2013. The magic spot: a ppGpp binding site on E. coli RNA polymerase responsible for regulation of transcription initiation. Mol. Cell 50:420–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haugen SP, Ross W, Gourse RL. 2008. Advances in bacterial promoter recognition and its control by factors that do not bind DNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:507–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dalebroux ZD, Swanson MS. 2012. ppGpp: magic beyond RNA polymerase. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kanjee U, Ogata K, Houry WA. 2012. Direct binding targets of the stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 85:1029–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kriel A, Bittner AN, Kim SH, Liu K, Tehranchi AK, Zou WY, Rendon S, Chen R, Tu BP, Wang JD. 2012. Direct regulation of GTP homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: a critical component of viability and stress resistance. Mol. Cell 48:231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krasny L, Gourse RL. 2004. An alternative strategy for bacterial ribosome synthesis: Bacillus subtilis rRNA transcription regulation. EMBO J. 23:4473–4483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heath RJ, Jackowski S, Rock CO. 1994. Guanosine tetraphosphate inhibition of fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis in Escherichia coli is relieved by overexpression of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (plsB). J. Biol. Chem. 269:26584–26590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cronan JE. 2003. Bacterial membrane lipids: where do we stand? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:203–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li SJ, Cronan JE. 1993. Growth rate regulation of Escherichia coli acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase, which catalyzes the first committed step of lipid biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 175:332–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Podkovyrov SM, Larson TJ. 1996. Identification of promoter and stringent regulation of transcription of the fabH, fabD and fabG genes encoding fatty acid biosynthetic enzymes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1747–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Durfee T, Hansen AM, Zhi H, Blattner FR, Jin DJ. 2008. Transcription profiling of the stringent response in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:1084–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T. 2008. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 68:1128–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanaka Y, Tsujimura A, Fujita N, Isono S, Isono K. 1989. Cloning and analysis of an Escherichia coli operon containing the rpmF gene for ribosomal protein L32 and the gene for a 30-kilodalton protein. J. Bacteriol. 171:5707–5712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Podkovyrov S, Larson TJ. 1995. Lipid biosynthetic genes and a ribosomal protein gene are cotranscribed. FEBS Lett. 368:429–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Y, Cronan JE. 1996. Polar allele duplication for transcriptional analysis of consecutive essential genes: application to a cluster of Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthetic genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:3614–3620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Y, Cronan JE. 1998. Transcriptional analysis of essential genes of the Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthesis gene cluster by functional replacement with the analogous Salmonella typhimurium gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 180:3295–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zaslaver A, Bren A, Ronen M, Itzkovitz S, Kikoin I, Shavit S, Liebermeister W, Surette MG, Alon U. 2006. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat. Methods 3:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wahl A, My L, Dumoulin R, Sturgis JN, Bouveret E. 2011. Antagonistic regulation of dgkA and plsB genes of phospholipid synthesis by multiple stress responses in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1260–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Butland G, Peregrin-Alvarez JM, Li J, Yang W, Yang X, Canadien V, Starostine A, Richards D, Beattie B, Krogan N, Davey M, Parkinson J, Greenblatt J, Emili A. 2005. Interaction network containing conserved and essential protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nature 433:531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zeghouf M, Li J, Butland G, Borkowska A, Canadien V, Richards D, Beattie B, Emili A, Greenblatt JF. 2004. Sequential peptide affinity (SPA) system for the identification of mammalian and bacterial protein complexes. J. Proteome Res. 3:463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gaal T, Bartlett MS, Ross W, Turnbough CLJ, Gourse RL. 1997. Transcription regulation by initiating NTP concentration: rRNA synthesis in bacteria. Science 278:2092–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rao L, Ross W, Appleman JA, Gaal T, Leirmo S, Schlax PJ, Record MT, Jr, Gourse RL. 1994. Factor independent activation of rrnB P1. An “extended” promoter with an upstream element that dramatically increases promoter strength. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1421–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Paul BJ, Barker MM, Ross W, Schneider DA, Webb C, Foster JW, Gourse RL. 2004. DksA: a critical component of the transcription initiation machinery that potentiates the regulation of rRNA promoters by ppGpp and the initiating NTP. Cell 118:311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Battesti A, Bouveret E. 2012. The bacterial two-hybrid system based on adenylate cyclase reconstitution in Escherichia coli. Methods 58:325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gully D, Moinier D, Loiseau L, Bouveret E. 2003. New partners of acyl carrier protein detected in Escherichia coli by tandem affinity purification. FEBS Lett. 548:90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crosby HA, Pelletier DA, Hurst GB, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2012. System-wide studies of N-lysine acetylation in Rhodopseudomonas palustris reveal substrate specificity of protein acetyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 287:15590–15601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Campbell JW, Cronan JE. 2002. The enigmatic Escherichia coli fadE gene is yafH. J. Bacteriol. 184:3759–3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang YM, Marrakchi H, Rock CO. 2002. The FabR (YijC) transcription factor regulates unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:15558–15565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Traxler MF, Zacharia VM, Marquardt S, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Stark SE, Conway T. 2011. Discretely calibrated regulatory loops controlled by ppGpp partition gene induction across the ‘feast to famine’ gradient in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 79:830–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gui L, Sunnarborg A, LaPorte DC. 1996. Regulated expression of a repressor protein: FadR activates iclR. J. Bacteriol. 178:4704–4709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ross W, Gourse RL. 2009. Analysis of RNA polymerase-promoter complex formation. Methods 47:13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee DJ, Minchin SD, Busby SJ. 2012. Activating transcription in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66:125–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vanden Boom T, Cronan JE. 1989. Genetics and regulation of bacterial lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 43:317–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sarubbi E, Rudd KE, Cashel M. 1988. Basal ppGpp level adjustment shown by new spoT mutants affect steady state growth rates and rrnA ribosomal promoter regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 213:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Barker MM, Gaal T, Josaitis CA, Gourse RL. 2001. Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 305:673–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Murray HD, Schneider DA, Gourse RL. 2003. Control of rRNA expression by small molecules is dynamic and nonredundant. Mol. Cell 12:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Feng Y, Cronan JE. 2011. The Vibrio cholerae fatty acid regulatory protein, FadR, represses transcription of plsB, the gene encoding the first enzyme of membrane phospholipid biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 81:1020–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yao Z, Davis RM, Kishony R, Kahne D, Ruiz N. 2012. Regulation of cell size in response to nutrient availability by fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:E2561–E2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lemke JJ, Durfee T, Gourse RL. 2009. DksA and ppGpp directly regulate transcription of the Escherichia coli flagellar cascade. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Farewell A, Diez AA, DiRusso CC, Nystrom T. 1996. Role of the Escherichia coli FadR regulator in stasis survival and growth phase-dependent expression of the uspA, fad, and fab genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:6443–6450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pech-Canul A, Nogales J, Miranda-Molina A, Alvarez L, Geiger O, Soto MJ, Lopez-Lara IM. 2011. FadD is required for utilization of endogenous fatty acids released from membrane lipids. J. Bacteriol. 193:6295–6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ross W, Thompson JF, Newlands JT, Gourse RL. 1990. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 9:3733–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gentry DR, Hernandez VJ, Nguyen LH, Jensen DB, Cashel M. 1993. Synthesis of the stationary-phase sigma factor sigma s is positively regulated by ppGpp. J. Bacteriol. 175:7982–7989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moffatt BA, Studier FW. 1987. T7 lysozyme inhibits transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Cell 49:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bachmann BJ. 1996. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12, p 2460–2488 In Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R, III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE. (ed), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.