Abstract

The symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti harbors a gene, SMc02396, which encodes a predicted outer membrane porin that is conserved in many symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria in the order Rhizobiales. Here, this gene (renamed ropA1) is shown to be required for infection by two commonly utilized transducing bacteriophages (ΦM12 and N3). Mapping of S. meliloti mutations conferring resistance to ΦM12, N3, or both phages simultaneously revealed diverse mutations mapping within the ropA1 open reading frame. Subsequent tests determined that RopA1, lipopolysaccharide, or both are required for infection by all of a larger collection of Sinorhizobium-specific phages. Failed attempts to disrupt or delete ropA1 suggest that this gene is essential for viability. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that ropA1 homologs in many Rhizobiales species are often found as two genetically linked copies and that the intraspecies duplicates are always more closely related to each other than to homologs in other species, suggesting multiple independent duplication events.

INTRODUCTION

Many infective phages are expected to exist for any given bacterial species, but outside Escherichia coli and Lactococcus lactis, very little is known about the cell surface receptors used by phages to gain entry to the cell (1). Adsorption of phage to the bacterial host is the key host range determinant (2). Phage adsorption takes place in two steps: first, reversible contact with the host cell surface, and second, irreversible binding to the host receptor (3, 4). Any molecule exposed on the bacterial cell surface is available as a phage receptor. Bacteriophage receptors in Gram-negative bacteria can be classified into four broad categories: outer membrane proteins, flagella, pili, and extracellular polysaccharides. Within this last group, the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer of Gram-negative bacteria is a common phage target. Outer membrane protein receptors can be further divided into several subcategories: structural proteins, porins, enzymes, high-affinity substrate receptors, and exporters (2). A variety of tactics, including alteration, downregulation, or deletion of the receptor, obstruction of access to the receptor (through production of exopolysaccharides, lipoproteins, or competitive inhibitors), blocking of phage DNA entry (often a consequence of lysogeny), restriction of phage DNA, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-mediated immunity, and even programmed cell death, are employed by bacteria to prevent phage infection (1). With respect to alteration of the receptor, deletion or downregulation can be costly for the bacterium (5), so subtle sequence alteration is a relatively benign mechanism for evolving phage resistance.

Two transducing phages, ΦM12 and N3, are extensively used for transduction in the S. meliloti laboratory strain Rm1021. ΦM12 was originally isolated from a commercial S. meliloti inoculant manufactured in the United States (6), and N3 was originally isolated from soil obtained from an alfalfa field in Coachella Valley, CA (7). Despite the distance separating their respective collection sites, ΦM12 and N3 are predicted to be similar based on their reactions to antisera (6). Despite the frequent use of these phages, the corresponding bacterial receptors have never been described. In this work, we identify an essential outer membrane porin, RopA1, as a receptor for both ΦM12 and N3. Furthermore, we show that RopA1 and LPS account for the entry pathways used by all Sinorhizobium meliloti phages tested from a larger panel of diverse phage isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and phage susceptibility assays.

Escherichia coli and S. meliloti cultures were grown at 37°C and 30°C, respectively, in lysogeny broth (LB) supplemented as follows: CaCl2 (Ca2+; 4 mM), chloramphenicol (Cm; 30 μg/ml), kanamycin (Km; 30 μg/ml), neomycin (Nm; 100 μg/ml), streptomycin (Sm; 200 μg/ml), and tetracycline (Tc; 5 μg/ml). To evaluate phage resistance, 2 μl of phage lysate (108 to 109 PFU/ml) was spotted onto lawns of S. meliloti on LB-Sm-Ca2+ agar.

Isolation of phage-resistant mutants.

S. meliloti Rm1021 was grown overnight in LB-Sm-Ca2+ broth and then 500 μl was subcultured into 3.5 ml. When the subculture had reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 1.0, a 30-μl aliquot of concentrated phage lysate (108 to 109 PFU/ml) of either ΦM12 or N3 was added to 400 μl of culture. After 0.5 h of incubation, phage-infected cultures were embedded in 10 ml of LB-Ca2+ top agar and incubated at 30°C for approximately 3 days until resistant colonies began to appear. Resistant colonies were picked out using a sterile toothpick, spread on LB-Sm-Ca2+ agar, and spotted with 2 μl undiluted phage to confirm resistance.

Plasmid and strain construction.

Plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were constructed using standard techniques with enzymes purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA) The high-fidelity polymerase Pfx50 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for insert amplification. All custom oligonucleotides were purchased from Invitrogen and are listed in Table 2. Mobilization of plasmids was accomplished by triparental mating with helper E. coli B001 (DH5α harboring plasmid pRK600). pRK600 expresses trans-acting proteins required for mobilization of plasmids harboring the RK2 transfer origin (oriT). Tn5-110 minitransposon delivery and identification of transposon insertion sites by arbitrary PCR were described previously (8). Phage-mediated transduction was also described previously (6, 7).

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and bacteriophages used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or bacteriophage | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | E. coli cloning strain | 43 |

| B001 | DH5α harboring helper plasmid pRK600 | 44 |

| Rm1021 | S. meliloti SU47 Smr (progenitor to strains listed below) | 45 |

| B199 | lpsB::Tn5-110 Smr, Nmr | 8 |

| B912 | Rm1021 ropA1G129D N3r | This study |

| B920 | Rm1021 ropA1G84D ΦM12r | This study |

| B955 | Rm1021 ropA1G84A ΦM12r | This study |

| B956 | Rm1021 ropA1G84V ΦM12r | This study |

| B957 | Rm1021 ropA1G84R ΦM12r | This study |

| B958 | Rm1021 ropA1ΔA122-N124 ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| B959 | Rm1021 ropA1ΔG203-V204 ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| B961 | Rm1021 ropA1S87Y ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| B962 | Rm1021 ropA1S87F ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| B970 | Rm1021 ropA1205::GV ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| B971 | Rm1021 ropA1D134Y N3r | This study |

| B972 | Rm1021 ropA1ΔN124-D125 N3r | This study |

| B973 | Rm1021 ropA1126::ND N3r | This study |

| B974 | Rm1021 ropA1A199V ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| C540 | Rm1021 ropA1S89P ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| C551 | Rm1021 ropA1ΔV204-T205 resistant to other phages (see Table 3) | This study |

| C566 | Rm1021 ropA1ΔN121-D123 ΦM12r N3r | This study |

| C617 | ropA2::pJG584 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRF771 | Empty vector for Ptrp transcriptional fusions; Tcr | 46 |

| pRK600 | Self-transmissible helper plasmid; Cmr | 47 |

| pRK7813 | RK2 derivative carrying pUC9 polylinker and λ cos site; Tcr | 16 |

| pJG110 | Transposon delivery vector; Km/Nmr, Apr | 8 |

| pJG194 | 2.2-kb mobilizable suicide vector; Km/Nmr | 8 |

| pJG396 | Wild-type ropA1 (entire coding region) cloned into pRK771; Tcr | This study |

| pJG581 | A 367-bp internal fragment of ropA1 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG582 | A 334-bp internal fragment of hisC4 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG583 | A 405-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG584 | A 314-bp internal fragment of ropA2 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG624 | A 320-bp internal fragment of hisC4 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG627 | A 330-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG628 | A 319-bp internal fragment of ropA1 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG629 | A 291-bp internal fragment of ropA1 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG630 | A 333-bp internal fragment of SMc02397 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| pJG631 | A 330-bp internal fragment of ropA2 cloned into pJG194 | This study |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| ΦM1 | S. meliloti lytic phage | 6 |

| ΦM5 | S. meliloti lytic phage | 6 |

| ΦM6 | S. meliloti lytic phage | 6 |

| ΦM7 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from an alfalfa field | 6 |

| ΦM9 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from a commercial inoculant | 6 |

| ΦM10 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from a commercial inoculant | 6 |

| ΦM12 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from a commercial inoculant | 6 |

| ΦM14 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from a commercial inoculant | 6 |

| ΦM19 | S. meliloti lytic phage | 6 |

| N3 | S. meliloti lytic phage isolated from an alfalfa field | 7 |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Nmr, neomycin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | Direction | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| oJG664 | CAGTTTACTTTGCAGGGCTTCC | Forward | Sequence verification of pJG194 inserts |

| oJG1243 | TGCGAAAAAGGATGGATATACCG | Reverse | Sequence verification of pJG194 inserts |

| oJG524 | GGTGGCGCACTTCCTGATAGC | Forward | Sequence verification of pRF771 inserts |

| oJG525 | CGTTATCAGAACCGCCCAGACC | Reverse | Sequence verification of pRF771 inserts |

| oMC023 | CGCTCTAGACCCAGACCCGTTTGAAACTTTTG | Forward | Clone ropA1 into pRF771 |

| oMC024 | CGCGGATCCGTAGCCATACTCCAGAAAAGAG | Reverse | Clone ropA1 into pRF771 |

| oMC029 | CGAAAGCCTACGATCACAGG | Forward | Sequencing of ropA1 mutants |

| oMC030 | CGAAGAAGAGGTGCTGTTCC | Reverse | Sequencing of ropA1 mutants |

| oMC303 | CGCGGATCCTGAAGCCTACATCCAGCTCG | Forward | Clone a 367-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC304 | CGCTCTAGAGTAAGCGTTCGGGTTGGACG | Reverse | Clone a 367-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC305 | CTGGAACCAGGAAGACTTCG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG581 |

| oMC314 | CGCGGATCCGAAGATCTCGAAGGACTGCTC | Forward | Clone a 334-bp fragment of hisC4 into pJG194 |

| oMC315 | CGCTCTAGAGATTGCGGATCTTGTCGAAGG | Reverse | Clone a 334-bp fragment of hisC4 into pJG194 |

| oMC316 | CGCGGATCCCATGGCTTCCGCAAGGACC | Forward | Clone a 405-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 in pJG194 |

| oMC317 | CGCTCTAGACTTGATGTTCATTTCTGACCTCC | Reverse | Clone a 405-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 in pJG194 |

| oMC318 | CGCGGATCCGTTCAATTCCGATACGGATTCG | Forward | Clone a 314-bp fragment of ropA2 into pJG194 |

| oMC319 | CGCTCTAGACGAGCAGGTCGAAAGTCACG | Reverse | Clone a 314-bp fragment of ropA2 into pJG194 |

| oMC320 | CGCAAGCTTGAAGGTCCGAAGCCAGTCG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG583 |

| oMC326 | CCAATATCGCCATCGGAGAG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG582 |

| oMC345 | CGCGGATCCAAGATTGCGGCACGCATCG | Forward | Clone a 320-bp fragment of hisC4 into pJG194 |

| oMC346 | CGCTCTAGACATAGGGTACCGTGACCAGC | Reverse | Clone a 320-bp fragment of hisC4 into pJG194 |

| oMC347 | AACGTCACAACGCCAAGTGC | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG624 |

| oMC354 | CGCGGATCCAACGATGGGCATATGTACC | Forward | Clone a 330-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 in pJG194 |

| oMC355 | CGCTCTAGAGGATAAAACCGGGCAAGAGC | Reverse | Clone a 330-bp fragment upstream of ropA1 in pJG194 |

| oMC356 | TGACGCGGATCGAATGCAGC | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG627 |

| oMC357 | CGCGGATCCGAGCCCATGGAATACGTTCG | Forward | Clone a 319-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC358 | CGCTCTAGACTTCATCGACGTCGATCAGG | Reverse | Clone a 319-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC359 | GAAGCAAGGGCGGTTGATCG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG628 |

| oMC360 | CGCGGATCCAACCCGAACGCTTACTGG | Forward | Clone a 291-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC361 | CGCTCTAGATCAGGTCAGATTAGAAGTCACG | Reverse | Clone a 291-bp fragment of ropA1 into pJG194 |

| oMC362 | GCTCGCCTACATCTACGACG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG629 |

| oMC363 | CGCGGATCCGACCATCAACAGGAAGATGG | Forward | Clone a fragment of SMc02397 into pJG194 |

| oMC364 | CGCTCTAGACTTTTGCTCTCACCGTAAGCG | Reverse | Clone a fragment of SMc02397 into pJG194 |

| oMC365 | GTCAAGGAGACCACGCTTGC | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG630 |

| oMC366 | CGCGGATCCGCAGCTACGACACGGAATGG | Forward | Clone a second fragment of SMc02400 into pJG194 |

| oMC367 | CGCTCTAGACTGTGTAGTTGATCGCGAAGC | Reverse | Clone a second fragment of SMc02400 into pJG194 |

| oMC368 | GCTTCTTCTACAGCTGGTGG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG631 |

| oMC369 | TTTGCGATGCTTTCGGCATGG | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG581 |

| oMC370 | CAAGATCGGCGGCTTCATCC | Forward | Detection of integration of pJG584 |

Restriction sites used for cloning are underlined.

Transductional mapping.

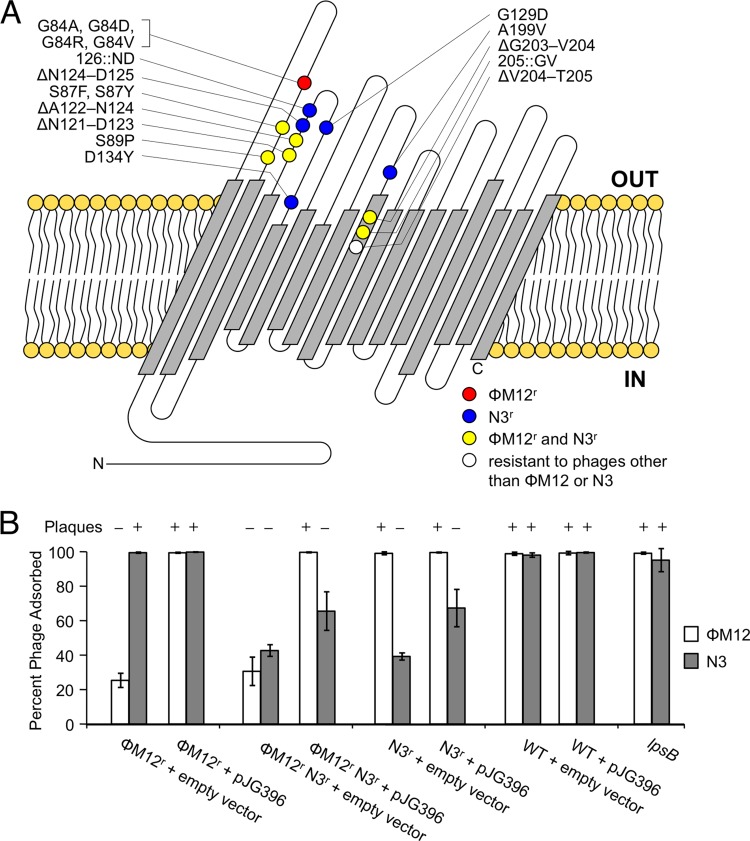

An N3-resistant mutant (G129D) (Fig. 1A) was mutagenized with Tn5-110, and the resulting mutant population was then transduced using ΦM12 into wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021. Cotransducing transposon insertions were characterized by arbitrary PCR. Two doubly marked strains were retransduced using ΦM12 into wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021, and recombination frequencies were calculated in order to determine the approximate location of the resistance mutation. The exact location of the mutation within ropA1 was resolved by Sanger sequencing. Conversely, a ΦM12-resistant mutant (G84D) (Fig. 1A) was mutagenized with Tn5-110 and the resistance mutation was mapped by transduction using N3. All other resistance alleles were identified by directly sequencing ropA1; many of the mutant alleles arose multiple times independently.

Fig 1.

RopA1 is the site of phage adsorption for ΦM12 and N3. (A) Predicted RopA1 outer membrane topology, along with alterations that give resistance to ΦM12 (red), N3 (blue), both (yellow), or other S. meliloti phages (white), is shown. (B) A ΦM12-resistant (ΦM12r) mutant (ropA1G84A), a ΦM12r N3r mutant (ropA1ΔG203-V204), and an N3r mutant (ropA1ΔN124-D125) were tested for phage adsorption (n = 3). Strains harbored either the empty vector control plasmid (pRF771) or the wild-type ropA1 clone pJG396. Error bars represent the standard deviations (SD). The susceptibility of these strains to plaque formation is also indicated.

RopA1 structural prediction.

After removal of a 22-amino-acid (aa) signal sequence predicted by SignalP 4.0 (9), which ends at the consensus peptidase cleavage site (AQA), the amino acid sequence of RopA1 was tested for its consistency with a transmembrane β-barrel configuration using PRED-TMBB (10) (http://biophysics.biol.uoa.gr/PRED-TMBB/).

Phage adsorption assays.

Cultures of S. meliloti strains were grown overnight in LB-Sm-Tc-Ca2+ and then subcultured and grown to an OD600 of approximately 1.0, whereupon 30 μl of concentrated phage lysate (108 to 109 PFU/ml) was added to 400 μl of bacterial culture (or 400 μl of LB as an uninoculated control) and shaken at 225 rpm at 30°C for 1 h (the predetermined time point at which maximum phage adsorption was observed in wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021). Cultures were then centrifuged for 30 s at 13,200 rpm. The supernatant, which contained unadsorbed phage particles, was then serially diluted, added to a fresh 400-μl culture of wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021, shaken at 225 rpm at 30°C for 0.5 h, embedded in 10 ml of LB-Ca2+ top agar, and incubated at 30°C overnight. Following incubation, plaques were counted and used to determine the concentration of unadsorbed phage in the original culture and then compared to the uninoculated control (total phage) with the following equation: % phage adsorbed = (total phage − unadsorbed phage)/total phage.

Genetic knockouts.

Disruption integration plasmids were introduced into S. meliloti Rm1021 via triparental mating performed on LB agar. Mating lawns were suspended in LB supplemented with 10% glycerol, serially diluted, and plated on selective medium (LB-Sm-Nm). PCR checks to verify plasmid integration into intended targets were conducted using a vector-specific primer (oJG1243) and a primer upstream of the intended integration site (Table 2).

Genomic alignments.

The following sequences (GenBank accession numbers in parentheses) were downloaded from the NCBI ftp website (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/): Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 circular chromosome (AE007869.2), Bartonella bacilliformis KC583 chromosome (CP000524.1), Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 chromosome (BA000040.2), Brucella melitensis bv. 1 strain 16 M chromosome I (AE008917.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 chromosome (BA000012.4), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 chromosome (CP001622.1), and Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021 chromosome (AL591688.1). Initial alignments were performed using progressiveMAUVE version 2.3.1 build 18 (11) (http://gel.ahabs.wisc.edu/mauve/) and then manually adjusted.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The following protein sequences (accession numbers in parentheses) were downloaded from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html): Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 Atu1020 (AAK86828.1), Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 Atu1021 (AAK86830.1), Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 Atu4693 (AAK88757.1), Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS 571 AZC_1213 (BAF87211.1), Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS 571 AZC_3535 (BAF89533.1), Bartonella bacilliformis KC583 BARBAKC583_0447 (ABM44571.1), Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 bll4983 (BAC50248.1), Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 bll5076 (BAC50341.1), Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 bll6888 (BAC52153.1), Brucella melitensis bv. 1 strain 16 M BMEI1305 (AAL52486.1), Brucella melitensis bv. 1 strain 16 M BMEI1306 (AAL52487.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 mll4029 (BAB50784.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 mll6389 (BAB52694.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 mll7738 (BAB54137.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 mlr7740 (BAB54139.1), Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 mlr7768 (BAB54159.1), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 Rleg_1139 (ACS55434.1), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 Rleg_2312 (ACS56587.1), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM1325 Rleg_6754 (ACS59793.1), Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021 SMc02396 (CAC45624.1), Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021 SMc02400 (CAC45628.1). Sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE web server (12) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/) with the default settings and then manually adjusted using MacClade version 4.08 (13) (http://macclade.org/index.html). The phylogenetic reconstruction was conducted using maximum parsimony with 1,000 replicates, implemented in PAUP* version 4.0 beta 10 (14) (http://paup.csit.fsu.edu/) using the default settings, and then visualized and exported using FigTree version 1.2.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

RESULTS

S. meliloti mutations conferring resistance to ΦM12 and N3 map to ropA1.

Transductionally mapping mutations which confer resistance to transducing phages presents obvious challenges. As a workaround, we acquired a mutation conferring specific resistance to ΦM12 and mapped it using N3; conversely, a mutation conferring specific resistance to N3 was mapped using ΦM12. All such resistance mutations mapped to the chromosomally carried gene SMc02396 (Fig. 1A). SMc02396 encodes a putative outer membrane porin predicted to form a 16-pass transmembrane β-barrel. Due to the similarity of SMc02396 to ropA (rhizobial outer membrane protein A) in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 248 (15), we propose that SMc02396 be renamed ropA1. Approximately 2 kb downstream of ropA1 is a similar gene, SMc02400, which also encodes an outer membrane porin. Based on its similarity to ropA1 (78% amino acid identity), we propose SMc02400 be renamed ropA2. Despite this similarity, none of our phage resistance alleles mapped to ropA2. Figure 1A describes all resistance alleles of ropA1 that have been sequenced to date. Many of these genetic alterations occurred multiple times in independently isolated resistant mutants. Some ropA1 alleles confer resistance to ΦM12, some confer resistance to N3, and some confer simultaneous resistance to both. It is interesting to note that all phage resistance mutations in ropA1 are either point mutations or small insertions/deletions that do not alter the frame of the coding region. Frameshift mutations, nonsense mutations, or large insertions/deletions have never been observed in ropA1.

RopA1 is the site of phage adsorption during infection.

To test whether ΦM12 and N3 bind to RopA1, we measured adsorption of both phages to ropA1 mutants that were resistant specifically to ΦM12 (ropA1G84A), resistant specifically to N3 (ropA1ΔN124-D125), or resistant to both (ropA1ΔG203-V204) in the presence of an empty vector (pRF771) or a plasmid-borne copy of constitutively expressed ropA1 (pJG396) (Fig. 1B). In the case of ΦM12, expression of wild-type ropA1 from pJG396 completely restored ΦM12 adsorption (P < 0.001). However, we observed only slight restoration of N3 adsorption upon reintroduction of ropA1 on the plasmid (P < 0.1). In the presence of an allele that simultaneously confers resistance to ΦM12 and N3, pJG396 is more effective for restoring adsorption of ΦM12 than of N3. In a plaquing assay, pJG396 restored the ability to form plaques in ropA1 mutant backgrounds resistant to ΦM12 but not in backgrounds resistant to N3 (Fig. 1B). Even when a given mutation conferred resistance to both phages, pJG396 restored plaquing by ΦM12 but not by N3.

Considering the possibility that resistance to N3 may act dominantly, we cloned ropA1ΔN124-D125 and ropA1ΔG203-V204 into pRF771 and introduced them into wild-type S. meliloti Rm1021. Ectopic expression of these resistant forms of RopA1 did not prevent N3 from forming plaques on the transformed strains (data not shown), suggesting that they are not dominant. To test whether ropA1 requires its native promoter for proper complementation, we cloned a copy of ropA1 that includes 720 bp of upstream untranslated sequence and 300 bp of downstream untranslated sequence. This fragment was ligated into pRK7813 (16) in both possible directions. These forward- and reverse-orientation clones behaved exactly like the constitutively expressed clone in that they were able to restore ΦM12 plaque formation but not N3 plaque formation (data not shown).

RopA1 and/or LPS is involved in phage infection for all phages tested.

In addition to ΦM12 and N3, we have acquired eight other S. meliloti phages from diverse sources (Table 1). To test whether the requirement for ropA1 was unique to ΦM12 and N3 or whether it was a general requirement for more phages in our collection, we tested all of our mutant strains against every phage (Table 3). Since LPS has previously been reported as a receptor for some of the phages in this collection (17), we also included an lpsB mutant. LpsB is a glycosyltransferase that may have a role in both incorporating mannose into Kdo2-lipid IVA and constructing the LPS core using ADP- or UDP-glucose (18, 19). Disruption of lpsB results in drastic alteration of the LPS core in S. meliloti (17) but does not prevent attachment of the O antigen (20). Two out of 10 phages required lpsB only (ΦM10 and ΦM14), four out of 10 required ropA1 only (ΦM7, ΦM12, ΦM19, and N3), and four out of 10 required both lpsB and ropA1 (ΦM1, ΦM5, ΦM6, and ΦM9). The last four probably use both LPS and RopA1 as coreceptors. The similarity of RopA1 to the RopA2 protein encoded downstream of ropA1 prompted us to also test phage resistance in a ropA2-disrupted strain. None of the phages tested required ropA2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

ropA1 and/or LPS is required for infection by all phages testeda

| Phage tested | Susceptibility of each RopA1 variant or other allele |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | G84A | G84D | G84R | G84V | S87F | S87Y | S89P | ΔN121-D123 | ΔA122-N124 | ΔG203-V204 | 205::GV | ΔN124-D125 | 126::ND | G129D | D134Y | A199V | ΔV204-T205 | lpsB | ropA2 | |

| ΦM12 | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| ΦM7 | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| ΦM19 | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| N3 | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S |

| ΦM1 | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S |

| ΦM6 | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | S |

| ΦM5 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S |

| ΦM9 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S |

| ΦM10 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S |

| ΦM14 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S |

RopA1 variants are indicated across the top. The Δ symbol indicates amino acid deletions, and the :: symbol indicates amino acid insertions. Loss-of-function alleles of lpsB and ropA2 are also indicated. S, susceptible; R, resistant.

ropA1 appears to be essential for viability in S. meliloti.

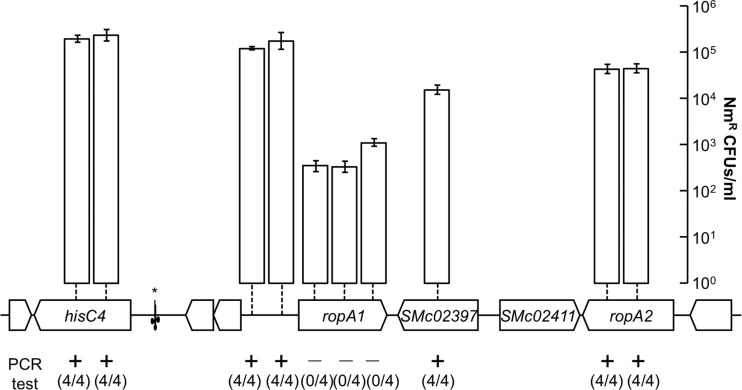

Mutations in ropA1 that conferred resistance to bacteriophages were always point mutations or insertions/deletions that were multiples of three base pairs, strongly suggesting that ropA1-null alleles are not tolerated. Furthermore, a ropA1 homolog in Brucella melitensis, omp2b, was reported to be essential (21), though no experimental evidence was provided. To test whether ropA1 might be essential for viability, we first made several failed attempts to create an in-frame deletion of ropA1 in strain Rm1021 using the pJQ200sk sacB vector (22). Even with the partially complementing plasmid pJG396 (described above), deletion of the chromosomal copy of ropA1 was not possible (data not shown). We then resorted to targeting the disruption of ropA1 by internal fragment (single-crossover) disruption. This experiment was performed with multiple controls: insertion disruptions were targeted to three different ropA1 internal regions as well as to seven arbitrarily chosen regions upstream and downstream of the ropA1 gene that were not predicted to be essential (Fig. 2). For these 10 plasmid insertion targets, PCR-based tests were designed to confirm that the intended integration events had occurred. All disruptions outside ropA1 successfully occurred, but no insertions in ropA1 were able to be generated. This indicates that ropA1 disruption leads to nonviable cells.

Fig 2.

ropA1, but not ropA2, is recalcitrant to genetic disruption. Ten locations targeted for single-crossover disruption are marked by vertical dashed lines. Colony yields for the attempted disruptions are shown by vertical bars (n = 9; error bars represent the standard errors of the means [SEM]). Four colonies from each of the 10 attempts were subsequently tested by PCR for the presence of the desired disruption. Negative results from this test indicate off-target integration elsewhere in the genome. The location of the tRNASer gene is indicated with an asterisk.

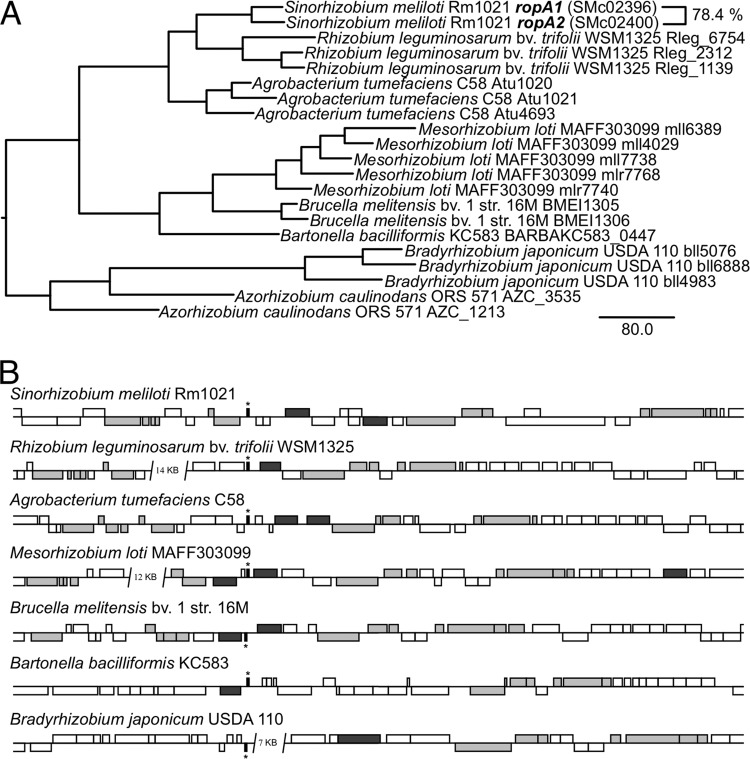

ropA1 orthologs in other Rhizobiales show evidence of recent gene duplication events.

The gene ropA2, which is located near ropA1 (Fig. 2), shares 78.4% identity with ropA1 at the amino acid level, suggesting a recent duplication event. Considering that similar duplications have been reported for other Rhizobiales (23, 24), we investigated whether these duplication events were of ancient origin or whether they had occurred independently in multiple lineages. A phylogenetic comparison of various representative organisms in the Rhizobiales (Fig. 3A) indicates that ropA1 homologs are almost always most closely related to duplicates within the same genus rather than orthologs in other genera. This observation points to some selective pressure for ropA orthologs in many alphaproteobacterial genera to independently duplicate. Considering that S. meliloti ropA1 and ropA2 are not functionally identical, these duplication events may give rise to functional diversification of ropA paralogs.

Fig 3.

RopA1 orthologs show evidence of multiple recent duplication events. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of RopA1 homologs in various representative Rhizobiales species underscores intraspecies nearest neighbors. (B) Duplication of ropA homologs (dark gray) frequently occurs in the vicinity of a tRNASer gene (indicated by an asterisk). Other syntenous genes are indicated in light gray.

Given that ropA1 and ropA2 are so close together spatially, we performed a genomic alignment of S. meliloti Rm1021 with the same organisms used in the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3B). The alignment confirmed that at least one copy of ropA lies in a conserved position in the genome of the various organisms, as evidenced by the conservation of synteny with certain genes both upstream (amn and hisC) and downstream (slt, dapA, smpB, rpoZ, and relA). Also of note is the presence in many strains of a tRNASer nearby. In half of the strains examined, a second copy of ropA was found nearby, and in one case (Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099), there was even a third copy within a few kilobases. An examination of other sequenced Rhizobiales genomes (including Bradyrhizobium sp. BTAi1, Nitrobacter hamburgensis X14, Ochrobactrum anthropi ATCC 49188, Parvibaculum lamentivorans DS-1, Pseudovibrio sp. FO-BEG1, Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2) gave further evidence for one or more duplications of ropA at this locus. It should also be noted that in contrast to most Rhizobium strains, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 248 (which was not included in the genomic alignment since its genome has not yet been sequenced) has two copies of ropA in close proximity to each other (23).

DISCUSSION

RopA1 is highly expressed in free-living S. meliloti (25) and likely forms a major portion of the S. meliloti outer membrane protein population. Thus, it is a convenient target for phage binding. We have shown that certain alterations in the RopA1 amino acid sequence prevent infection by eight of the 10 S. meliloti phages tested (Table 3). In the case of the two transducing phages (ΦM12 and N3), every phage-resistant mutant tested was mutated in ropA1. Additionally, the adsorption of ΦM12 and N3 to various ropA1 mutant strains was reduced (Fig. 1B). This confirms the role of RopA1 as a receptor for these phages. Previous work in Rhizobium leguminosarum correlates phage resistance with a loss of an antigen (26) later identified as RopA, but definitive experiments to test RopA as a susceptibility factor or receptor were not performed.

This system is unique in that both ΦM12 binding and DNA injection (as evidenced by the formation of plaques) are completely restored by plasmid-based expression of ropA1, but for N3, binding is only partially restored and plaque formation is not observed (Fig. 1B). The incomplete-complementation phenomenon is not allele specific but phenotype specific. Additionally, the apparent lethality brought about by a ropA1 disruption seems not to be complemented by a plasmid since repeated attempts to delete or disrupt ropA1 in the presence of a complementing plasmid have failed (data not shown). This is why our evidence for the essentiality of ropA1 has to depend on well-controlled negative data (Fig. 2). We cannot currently explain the mechanistic basis for this incomplete-complementation phenomenon.

Only ΦM10 and ΦM12 of our panel of 10 phages did not exhibit a requirement for RopA1 for infection (Table 3). LPS is also a major component of the Gram-negative bacterial cell surface and frequently occurs as a phage receptor (4). Our observation that the lpsB mutant was resistant to six of the 10 phages is in agreement with a previous report (17). Three of the remaining phages in that study (ΦM7, ΦM12, and ΦM19) were reported to be unaffected by any of a variety of LPS mutants, suggesting that LPS plays no role in infection by these phages. We show here that RopA1 serves as the receptor for all three as well as for N3.

The impossibility of disrupting ropA1 under laboratory conditions leads us to conclude that ropA1 is essential for viability in S. meliloti. Despite the general belief that porins play a role in outer membrane function and stability of Gram-negative bacteria (27), there are very few instances of a porin being shown to be essential. Members of the Omp85/BamA (β-barrel assembly machine protein A) family have been shown to be responsible for the assembly and insertion of proteins and LPS into the outer membrane (28, 29). These proteins are therefore essential for cell viability and are found throughout Gram-negative bacteria. Two genes in S. meliloti Rm1021 belong to the bamA gene family: SMc02094 and SMc03097. While we cannot rule out a role for RopA1 in outer membrane biogenesis, it does not appear to belong to the Omp85/BamA family of porins.

With the exception of Omp85/BamA homologs, no porins are reported to be essential in Escherichia coli (30, 31), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32), Haemophilus influenzae (33), or Salmonella enterica (34). The omp2b gene of Brucella melitensis (a ropA1 homolog) has been reported to be essential, but no experimental evidence is given (21). The porB gene of Neisseria gonorrhea has also been reported to be essential, but again, no experimental evidence is given (35, 36). Since both ropA1 in S. meliloti (this report) and omp2b in Brucella melitensis (21) are believed to be essential, it may be that ropA homologs are essential in most Rhizobiales species which possess them. One possible exception is the single ropA homolog in Bartonella henselae, omp43, which has been successfully disrupted (37).

Homology-based searches of sequence databases do not suggest a specific function for RopA1. The ropA1 expression pattern, as revealed by several studies, points to a specific role for ropA1 in growing cells, since terminally differentiated bacteroids tend to display very low levels of ropA1 expression. Bacteroids are nongrowing, differentiated, nitrogen-fixing forms of rhizobia that occupy host cells within the root nodule. Root nodules can be broadly classified as determinate or indeterminate based on whether the nodule has a persistent apical meristem. Bacteroids in determinate nodules can dedifferentiate upon release from nodule cells, but bacteroids in indeterminate nodules are terminally differentiated (38). Both ropA1 and ropA2 of S. meliloti are highly expressed in free-living conditions (25) but strongly downregulated in the terminally differentiated bacteroids of Medicago truncatula (39). Downregulation of ropA and ropA2 in Rhizobium leguminosarum has been observed for several hosts that form indeterminate nodules (pea, broadbean, vetch, clover), but in a host that forms determinate nodules (common bean), neither is downregulated (40). There is, therefore, a remarkable correlation between cells that are competent for proliferation and the expression of ropA1.

The frequent occurrence of ropA1 duplication at a conserved locus in multiple species (Fig. 3B) suggests some plasticity in this region of Rhizobiales genomes. Acquisition, loss, or duplication of genes may be due to the insertion and incorrect excision of prophage genomes (41). An examination of the genomes of sequenced S. meliloti strains AK83 and Rm41 revealed the presence of two independent prophages which have been inserted into the tRNASer just upstream of ropA1 (not shown). The idea of bacteriophages linking their own DNA near receptor-encoding genes is an intriguing one. Indeed, in a recent multigenome analysis of S. meliloti and the closely related species Sinorhizobium medicae, the authors concluded that ropA1 was the only chromosomal gene that showed evidence of horizontal transfer between the two species (42). This may be due to this region being a hot spot for prophage insertion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Graham Walker (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for providing the phage panel and Ivan Oresnik (University of Manitoba) for providing pRK7813. We also thank Michael Bevans for help with experiments and Camille Porter for help with the phylogenetic analysis.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant IOS-1054980.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakhuba DV, Kolomiets EI, Dey ES, Novik GI. 2010. Bacteriophage receptors, mechanisms of phage adsorption and penetration into host cell. Pol. J. Microbiol. 59:145–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letellier L, Boulanger P, Plançon L, Jacquot P, Santamaria M. 2004. Main features on tailed phage, host recognition and DNA uptake. Front. Biosci. 9:1228–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindberg AA. 1973. Bacteriophage receptors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 27:205–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyman P, Abedon ST. 2010. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 70:217–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finan TM, Hartweig E, LeMieux K, Bergman K, Walker GC, Signer ER. 1984. General transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 159:120–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin MO, Long SR. 1984. Generalized transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 159:125–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffitts JS, Long SR. 2008. A symbiotic mutant of Sinorhizobium meliloti reveals a novel genetic pathway involving succinoglycan biosynthetic functions. Mol. Microbiol. 67:1292–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8:785–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagos PG, Liakopoulos TD, Spyropoulos IC, Hamodrakas SJ. 2004. PRED-TMBB: a web server for predicting the topology of β-barrel outer membrane proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W400–W404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. 2010. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5:e11147. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. 1989. Interactive analysis of phylogeny and character evolution using the computer program MacClade. Folia Primatol. (Basel) 53:190–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swofford D. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Maagd RA, Mulders IH, Canter Cremers HC, Lugtenberg BJ. 1992. Cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of a Rhizobium leguminosarum gene encoding a symbiotically repressed outer membrane protein. J. Bacteriol. 174:214–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones JD, Gutterson N. 1987. An efficient mobilizable cosmid vector, pRK7813, and its use in a rapid method for marker exchange in Pseudomonas fluorescens strain HV37a. Gene 61:299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell GR, Sharypova LA, Scheidle H, Jones KM, Niehaus K, Becker A, Walker GC. 2003. Striking complexity of lipopolysaccharide defects in a collection of Sinorhizobium meliloti mutants. J. Bacteriol. 185:3853–3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanipes MI, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Hozbor DF, Lagares A, Raetz CR. 2003. Relaxed sugar donor selectivity of a Sinorhizobium meliloti ortholog of the Rhizobium leguminosarum mannosyl transferase LpcC. Role of the lipopolysaccharide core in symbiosis of Rhizobiaceae with plants. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16365–16371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagares A, Hozbor DF, Niehaus K, Otero AJ, Lorenzen J, Arnold W, Pühler A. 2001. Genetic characterization of a Sinorhizobium meliloti chromosomal region in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 183:1248–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell GR, Reuhs BL, Walker GC. 2002. Chronic intracellular infection of alfalfa nodules by Sinorhizobium meliloti requires correct lipopolysaccharide core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:3938–3943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laloux G, Deghelt M, de Barsy M, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X. 2010. Identification of the essential Brucella melitensis porin Omp2b as a suppressor of Bax-induced cell death in yeast in a genome-wide screening. PLoS One 5:e13274. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quandt J, Hynes MF. 1993. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roest HP, Bloemendaal CJ, Wijffelman CA, Lugtenberg BJ. 1995. Isolation and characterization of ropA homologous genes from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovars viciae and trifolii. J. Bacteriol. 177:4985–4991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ficht TA, Bearden SW, Sowa BA, Adams LG. 1989. DNA sequence and expression of the 36-kilodalton outer membrane protein gene of Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 57:3281–3291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ampe F, Kiss E, Sabourdy F, Batut J. 2003. Transcriptome analysis of Sinorhizobium meliloti during symbiosis. Genome Biol. 4:R15. 10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-r15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Maagd RA, Wientjes FB, Lugtenberg BJ. 1989. Evidence for divalent cation (Ca2+)-stabilized oligomeric proteins and covalently bound protein-peptidoglycan complexes in the outer membrane of Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Bacteriol. 171:3989–3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairman JW, Noinaj N, Buchanan SK. 2011. The structural biology of β-barrel membrane proteins: a summary of recent reports. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:523–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voulhoux R, Bos MP, Geurtsen J, Mols M, Tommassen J. 2003. Role of a highly conserved bacterial protein in outer membrane protein assembly. Science 299:262–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genevrois S, Steeghs L, Roholl P, Letesson JJ, van der Ley P. 2003. The Omp85 protein of Neisseria meningitidis is required for lipid export to the outer membrane. EMBO J. 22:1780–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto N, Nakahigashi K, Nakamichi T, Yoshino M, Takai Y, Touda Y, Furubayashi A, Kinjyo S, Dose H, Hasegawa M, Datsenko KA, Nakayashiki T, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2009. Update on the Keio collection of Escherichia coli single-gene deletion mutants. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5:335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, Will O, Kaul R, Raymond C, Levy R, Chun-Rong L, Guenthner D, Bovee D, Olson MV, Manoil C. 2003. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14339–14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akerley BJ, Rubin EJ, Novick VL, Amaya K, Judson N, Mekalanos JJ. 2002. A genome-scale analysis for identification of genes required for growth or survival of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:966–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langridge GC, Phan MD, Turner DJ, Perkins TT, Parts L, Haase J, Charles I, Maskell DJ, Peters SE, Dougan G, Wain J, Parkhill J, Turner AK. 2009. Simultaneous assay of every Salmonella Typhi gene using one million transposon mutants. Genome Res. 19:2308–2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fudyk TC, Maclean IW, Simonsen JN, Njagi EN, Kimani J, Brunham RC, Plummer FA. 1999. Genetic diversity and mosaicism at the por locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 181:5591–5599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer FJ, Rudel T, Stein M, Meyer TF. 1999. Mutagenesis of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae porin reduces invasion in epithelial cells and enhances phagocyte responsiveness. Mol. Microbiol. 31:903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vayssier-Taussat M, Le Rhun D, Deng HK, Biville F, Cescau S, Danchin A, Marignac G, Lenaour E, Boulouis HJ, Mavris M, Arnaud L, Yang H, Wang J, Quebatte M, Engel P, Saenz H, Dehio C. 2010. The Trw type IV secretion system of Bartonella mediates host-specific adhesion to erythrocytes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000946. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirsch AM. 1992. Tansley review no. 40. Developmental biology of legume nodulation. New Phytol. 122:211–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnett MJ, Toman CJ, Fisher RF, Long SR. 2004. A dual-genome Symbiosis Chip for coordinate study of signal exchange and development in a prokaryote–host interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:16636–16641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roest HP, Goosenderoo L, Wijffelman CA, Demaagd RA, Lugtenberg BJJ. 1995. Outer membrane protein changes during bacteroid development are independent of nitrogen fixation and differ between indeterminate and determinate nodulating host plants of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 8:14–22 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wibberg D, Blom J, Jaenicke S, Kollin F, Rupp O, Scharf B, Schneiker-Bekel S, Sczcepanowski R, Goesmann A, Setubal JC, Schmitt R, Pühler A, Schlüter A. 2011. Complete genome sequencing of Agrobacterium sp. H13-3, the former Rhizobium lupini H13-3, reveals a tripartite genome consisting of a circular and a linear chromosome and an accessory plasmid but lacking a tumor-inducing Ti-plasmid. J. Biotechnol. 155:50–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein B, Branca A, Mudge J, Bharti AK, Briskine R, Farmer AD, Sugawara M, Young ND, Sadowsky MJ, Tiffin P. 2012. Population genomics of the facultatively mutualistic bacteria Sinorhizobium meliloti and S. medicae. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002868. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:4645–4649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffitts JS, Carlyon RE, Erickson JH, Moulton JL, Barnett MJ, Toman CJ, Long SR. 2008. A Sinorhizobium meliloti osmosensory two-component system required for cyclic glucan export and symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:479–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meade HM, Long SR, Ruvkun GB, Brown SE, Ausubel FM. 1982. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 149:114–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells DH, Long SR. 2002. The Sinorhizobium meliloti stringent response affects multiple aspects of symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1115–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finan TM, Kunkel B, De Vos GF, Signer ER. 1986. Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti carrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J. Bacteriol. 167:66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]