Abstract

Mycobacterium abscessus (M. abscessus sensu lato, or the M. abscessus group) comprises three closely related taxa whose taxonomic statuses are under revision, i.e., M. abscessus sensu stricto, Mycobacterium bolletii, and Mycobacterium massiliense. We describe here a simple, robust, and cost-effective PCR-based method for distinguishing among M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii. Based on the M. abscessus ATCC 19977T genome, regions that discriminated between M. abscessus and M. massiliense were identified through array-based comparative genomic hybridization. A typing scheme using PCR primers designed for four of these locations was applied to 46 well-characterized clinical isolates comprising 29 M. abscessus, 15 M. massiliense, and 2 M. bolletii isolates previously identified by multitarget sequencing. Interestingly, 2 isolates unequivocally identified as M. massiliense were shown to have a full-length erm(41) gene instead of the expected gene deletion and showed inducible clarithromycin resistance after 14 days. We propose using this PCR-based typing scheme combined with erm(41) PCR for straightforward identification of M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii and the assessment of inducible clarithromycin resistance. This method can be easily integrated into a routine workflow to provide subspecies-level identification within 24 h after isolation of the M. abscessus group.

INTRODUCTION

Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) are ubiquitous environmental microorganisms and a significant cause of human disease (1). The prevalence of lung disease due to RGM is increasing and in many areas of the United States exceeds that of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2). Within the RGM, the Mycobacterium abscessus group is a prominent cause of lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic pulmonary disease (bronchiectasis, nodules, and cavitations) and of posttraumatic and postsurgical infections (1, 3). Infections with organisms in the M. abscessus group are difficult to treat, due to both natural broad-spectrum resistance and acquired resistance, with various antibiotic susceptibility patterns being observed among isolates (4). M. abscessus sensu lato, or the M. abscessus group, was recently divided into three closely related taxa, i.e., M. abscessus sensu stricto (hereinafter referred to as M. abscessus), Mycobacterium massiliense, and Mycobacterium bolletii. M. massiliense has been recognized increasingly as an emerging pathogen causing postsurgical wound infection outbreaks (5), and recently it was identified as a cause of respiratory outbreaks in two cystic fibrosis centers, with evidence of transmission between patients (6, 7).

The taxonomic status of the M. abscessus group remains controversial. M. massiliense and M. bolletii were initially proposed as new species mainly on the basis of divergence of their rpoB sequences. However, further studies showed that these organisms could not be separated by biochemical tests and mycolic acid pattern analysis (8) and showed less genomic divergence than would be expected for separate species (8, 9). It was recently proposed to unite M. massiliense and M. bolletii as Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii and to designate the new taxon Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus for M. abscessus isolates (10). However, recent phylogenetic analysis based on whole-genome sequencing data supports the separation of the M. abscessus group into three taxa, namely, Mycobacterium abscessus subsp abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (7).

Due to their high levels of relatedness, members of the M. abscessus group cannot be differentiated on the basis of single-gene sequencing (11, 12). Zelazny et al. combined typing through repetitive sequence-based PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of macrorestricted DNA with three-locus sequence analysis (hsp65, rpoB, and secA1) to resolve ambiguous identification of M. abscessus isolates as M. abscessus, M. massiliense, or M. bolletii (13). Macheras et al. developed a multilocus sequence-based phylogenomic analysis based on eight housekeeping genes (9) and reported the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer among members of the M. abscessus group, including the exchange of alleles of genes used for identification and typing. Recently, Choi et al. (14) used two tandem-repeat loci for identification of the M. abscessus group, and Wong et al. (15) reported variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) analysis for molecular typing of M. abscessus. More recently, Sassi et al. (16) proposed a multispacer typing scheme using 8 intergenic spacers, which are thought to undergo less evolutionary pressure and thus are more variable than housekeeping genes. The recent incorporation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) in clinical laboratories has led to increased speed and accuracy in the identification of mycobacteria (17–20). However, closely related strains such as M. abscessus and M. massiliense could not be distinguished by this methodology (17, 18).

Macrolides, such as clarithromycin and azithromycin, are frequently the only oral antibiotics that are active against M. abscessus and M. massiliense. However, some M. abscessus isolates are resistant to clarithromycin due to point mutations at positions A2058 and A2059 in the region of the rrl gene encoding the peptidyltransferase domain of 23S rRNA (21). A second mechanism confers inducible resistance via a functional erythromycin ribosomal methylase gene, erm(41). This inducible resistance can be assessed in vitro by extended incubation of the organism with clarithromycin (22). The M. massiliense erm(41) gene contains mutations, including a large C-terminal deletion that renders it nonfunctional. Based on size differences of the product, erm(41) PCR was proposed as a simple method to differentiate M. massiliense from M. abscessus and M. bolletii (23, 24).

Recent publications provide evidence that individual subspecies or even strains of the M. abscessus complex are associated with specific patient populations and with differing clinical implications and outcomes (4, 6, 7, 25). Therefore, timely accurate identification of the members of the M. abscessus group is important for patient management and epidemiological purposes.

We describe here a simple, robust, and cost-effective PCR-based method for distinguishing among M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii based on discriminatory regions identified using comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis with M. abscessus strain ATCC 19977T. In addition, we report the presence of a full-length erm(41) gene in M. massiliense clinical isolates that show inducible clarithromycin resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA isolation from reference strains and clinical isolates.

Forty-three clinical isolates belonging to the M. abscessus group were obtained from sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, blood culture, skin, or lymph node specimens, as described in a previous publication by Zelazny et al. (13). Three additional clinical isolates were obtained from sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and blood samples from patients with bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, and interleukin 21 receptor gene-related primary immunodeficiency, respectively. In addition, three reference strains, i.e., M. abscessus ATCC 19977T, M. massiliense CCUG 48898T, and M. bolletii CCUG 50184T, were included. The bacterial strains were stored at −70°C in Tween-albumin broth (Remel, Lenexa, KS). Prior to use, the strains were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS). DNA was extracted from a 10-μl loopful of each mycobacterial colony by use of an UltraClean microbial DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Solana Beach, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microarray design and hybridization.

The Mycobacterium abscessus (ATCC 19977T) genome sequence was downloaded from the NCBI database (GenBank accession number CU458896.1) and was analyzed with DustMasker to identify low-complexity regions. Microarray probe sequences were selected by “tiling” 60-mers end to end (zero overlap) for 100% coverage. A total of 84,452 probe sequences were uploaded to the Agilent eArray website for fabrication of SurePrint microarrays in the 4x180K format (custom array design number 025760), with each probe spotted in duplicate on each array.

Genomic DNA was labeled using the Agilent genomic DNA enzymatic labeling kit, using Cy3 dye for test samples and Cy5 for the reference strain (M. abscessus ATCC 19977T). Arrays were hybridized using the Agilent Oligo CGH hybridization kit and were scanned using an Agilent microarray scanner at 3-μm resolution, using an extended dynamic range setting (XDR) of 100% and 10% photomultiplier tube voltage (PMT). Agilent Feature Extraction version 10.7.3.1 software, protocol CGH_107_Sep09, was used for image analysis.

CGH microarray data analysis.

Normalized log2 signal ratios were calculated for every microarray probe for each of the test strains, with the value for the reference strain (M. abscessus ATCC 19977T) as the denominator. The log ratios therefore represent the genomic contents of the test strands relative to the reference at each 60-mer tiled across the reference genome. The test strains used included M. abscessus clinical isolate CI79, the M. massiliense type strain (CCUG 48898), and M. massiliense clinical isolates CI76, CI11, and CI154.

Chromosomal segments with altered copy numbers (copy number variations [CNVs]), relative to the reference strain, were identified by applying the circular binary segmentation (CBS) algorithm (26) to normalized log ratios ordered by chromosome position. Array data normalization, detection of CNVs, and genomic visualization were performed using JMP/Genomics software (SAS version 4.1). Genomic segments that differed between the M. massiliense and M. abscessus genomes were selected based on the expected product sizes, aiming for 1,000 to 2,000 bp for the full-length PCR product and a difference of at least 300 bp for the strain with deletions (to aid in unambiguous detection).

Generation of primer pairs for genotyping and sequencing.

PCR primers for genotyping were designed using the Mycobacterium abscessus ATCC 19977T sequence (GenBank accession number CU458896.1) upstream and downstream of the differential CGH segments (27, 28). PCR was performed using 4 different primer pairs with 46 clinical isolates and three reference strains, using Qiagen Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA) in a 25-μl total reaction mixture volume with 12.5 μl of master mix composed of buffer, dNTPs, Taq polymerase, 2 to 3 μl (∼50 ng) of extracted DNA, and water to achieve a final volume of 25 μl. Additionally, the region of the erm(41) gene was amplified with the primers ermF (5′-GAC CGG GGC CTT CTT CGT GAT-3′) and ermR1 (5′-GAC TTC CCC GCA CCG ATT CC-3′) (22, 24). The PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 62°C or 66°C (specified below) for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min, with final extension at 72°C for 10 min. An annealing temperature of 62°C was used for PCRs with the erm(41) gene and MAB_4751 primers, while 66°C was used for PCRs with MAB_2396, MAB_2697c, and MAB_4792 primers. PCR products were visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products from the erm(41) gene were purified for sequencing using 0.5-ml Amicon Ultra 100K centrifugal filters (Millipore Ltd., Ireland). In silico PCR was done using NCBI BLASTn (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with this set of primer pairs and the publicly available M. abscessus ATCC 19977T and M. massiliense CCUG 48898T genome sequences to obtain the expected PCR product size for each taxon. The M. bolletii genome was not used since the available sequences were located in more than 20 contigs. Sequencing of PCR amplicons was performed with an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), and data were assembled using Lasergene SeqMan Pro technology (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). Sequences were compared against the GenBank database using NCBI BLASTn (27) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Clarithromycin susceptibility testing.

Clarithromycin MIC values were determined in Mueller-Hinton medium by the broth microdilution method, using Sensititre RGMYCO plates (Trek Diagnosis, Cleveland, OH). Plates were evaluated after 3 to 5 days and were further incubated for 14 days at 30°C for a final reading to ensure detection of inducible resistance, and the interpretative breakpoints used were those recommended by the CLSI (29).

Accession numbers.

Microarray data files were deposited in the NCBI GEO archive (accession number GSE43629). The erm(41), hsp65, rpoB, and secA1 partial gene sequences from strains CI2040 and CI8182 were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KF360854 to KF360861.

RESULTS

CNV detection and selection for use in genotyping.

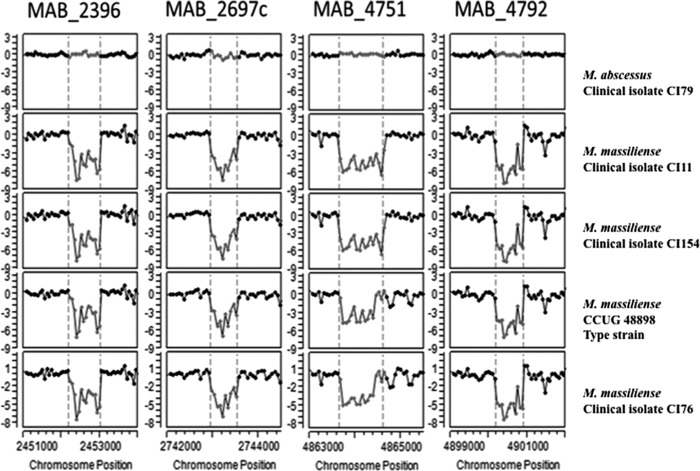

We performed CGH to identify chromosomal aberrations by copy number variation (CNV) to distinguish M. abscessus from M. massiliense, using the type strain ATCC 19977 and clinical isolate CI79 as representatives of M. abscessus and the type strain CCUG 48898 and clinical isolates CI11, CI76, and CI154 as representatives of M. massiliense. Figure 1 shows CGH results against the M. abscessus reference genome for several representative test strains. The log2 ratios (y axis) are plotted against the genomic position of each tiling probe (x axis) for M. abscessus clinical isolate CI79 (Fig. 1, top panel), the M. massiliense type strain CCUG 48898 (Fig. 1, middle panel), and M. massiliense clinical isolate CI76 (Fig. 1, bottom panel). Log ratios close to 0 indicate genomic signal intensity similar to that of the M. abscessus ATCC 19977T reference genome (assumed to have a copy number of 1 for all regions targeted by the tiling probes), while contiguous regions with highly negative ratios indicate putative deletion segments (i.e., signal was absent due to lack of homologous DNA in the test strain). The M. abscessus isolate CI79 generally had the tightest signal ratio (least deviation from 0), consistent with greater sequence homology to probes designed from the M. abscessus ATCC 19977 type strain; however, several apparent deletions relative to the type strain were observed (Fig. 1, top panel). M. massiliense strain CCUG 48898T, and clinical isolate CI76 showed even more numerous deviations relative to the M. abscessus ATCC 19977T reference genome (Fig. 1, middle and bottom panels, respectively). The largest putative deletion segments approached 80 kb and thus were too large for straightforward analysis by PCR; CNVs that can be exploited in PCR assays were drawn from the population of smaller deletions.

Fig 1.

Whole-genome comparative genome hybridization (CGH) patterns of mycobacterial isolates relative to the M. abscessus type strain ATCC 19977. The normalized log2 signal ratios (y axis) for individual probes tiled across the genome (x axis) are shown for M. abscessus clinical isolate CI79 (top panel), the M. massiliense type strain CCUG 48898 (middle panel), and M. massiliense clinical isolate CI76 (bottom panel). Log ratios near 0 indicate genomic signal intensity similar to that of the M. abscessus reference genome, whereas contiguous regions of highly negative ratios indicate putative deletion segments (i.e., signal was absent due to lack of homologous DNA in the test strain).

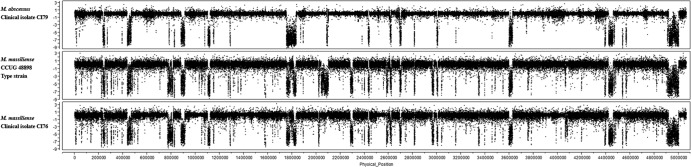

A detailed view of the CGH patterns of four putative CNVs is shown in Fig. 2 for MAB_2396, MAB_2697c, MAB_4751, and MAB_4792 genes, which were among the candidate loci to distinguish M. abscessus from M. massiliense. The borders (as determined by the CBS algorithm) of putative CNVs occurring in the M. massiliense strains relative to the M. abscessus type strain are indicated by dashed vertical lines. These regions reflect genomic losses in M. massiliense strains CI11, CI154, CCUG 48898T, and CI76 but are present in M. abscessus CI79 and ATCC 19977T. Table 1 describes the predicted discriminatory segments that were selected for PCR primer design after filtering for CNVs that were consistent, unambiguous, and in the desired size range. The CGH segments were labeled according to the locus tag of the 5′ most affected gene in that segment region.

Fig 2.

CGH patterns for four putative deletions that were selected as candidates to distinguish M. massiliense from M. abscessus. The normalized log2 signal ratios for individual probes in selected genomic regions are shown for M. abscessus and M. massiliense strains. Consistent log ratios (y axis) near 0 indicate that genomic DNA is present throughout these regions in M. abscessus clinical isolate CI79 and in the reference genome (M. abscessus type strain ATCC 19977). In contrast, the M. massiliense type strain CCUG 48898 and M. massiliense clinical isolates CI11, CI154, and CI76 show regions with negative ratios, suggesting the absence of genomic DNA at those locations.

Table 1.

Distinguishing gene segments in M. massiliense discovered by array CGH against the M. abscessus genome

| M. abscessus ATCC 19977T locus | Gene annotation | CNV in: |

Position of segment at: |

CGH segment length (estimated loss) (bp) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. abscessus isolate CI79 | M. massiliense CCUG 48898T and isolates CI11, CI154, and CI76 | Start | End | |||

| MAB_357 | Conserved hypothetical protein | None | Deletion | 354,601 | 355,621 | 1,020 |

| MAB_0705 | Conserved hypothetical protein | None | Deletion | 706,861 | 707,881 | 1,020 |

| MAB_1313 | Probable transcriptional regulator, AraC family | None | Deletion | 1,313,941 | 1,314,721 | 780 |

| MAB_2396 | Probable acetyltransferase | None | Deletion | 2,452,201 | 2,452,981 | 780 |

| MAB_2697c | Hypothetical protein | None | Deletion | 2,742,961 | 2,743,501 | 540 |

| MAB_4751 | Conserved hypothetical protein (patatin-like) | None | Deletion | 4,863,661 | 4,864,561 | 900 |

| MAB_4792 | Putative transcriptional regulator | None | Deletion | 4,900,201 | 4,900,861 | 660 |

Design and testing of a PCR-based genotyping scheme for the M. abscessus group.

Primers were designed from flanking regions upstream and downstream of four candidate differential regions (Table 2) by using the Mycobacterium abscessus ATCC 19977T sequence (GenBank accession number CU458896.1) as a template. Primers at four locations, i.e., MAB_2396, MAB_2697c, MAB_4751, and MAB_4792, and the erm(41) locus (22, 24) were selected for a large-scale survey of clinical isolates. In silico PCR was performed with the M. abscessus ATCC 19977T and M. massiliense CCUG 48898T genomes using BLAST (27), to confirm the expected sizes of PCR products from the respective genomes (Table 3).

Table 2.

PCR primers targeting regions that differ between M. abscessus and M. massiliense isolates

| M. abscessus ATCC 19977T locus | Gene annotation | Primers |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| MAB_2396 | Probable acetyltransferase | 5′-AGGCGGCCACCGACGTCGCGATGGA-3′ | 5′-TGCGCCCGCCCAGCGCGTATCCG-3′ |

| MAB_2697c | Hypothetical protein | 5′-GACTCCGGTGGCCGCGGCGA-3′ | 5′-GCCGGAGCGCTGGGTGGGCT-3′ |

| MAB_4751 | Conserved hypothetical protein (patatin-like) | 5′-CCCGCATGCAGCTGGCCGCGCA-3′ | 5′-GCGCCAGTGGTGGGGCCACCCGT-3′ |

| MAB_4792 | Putative transcriptional regulator | 5′-GCGGTGACGACCGCGGGGGCGAT-3′ | 5′-TCGGGGCAGGCCAGGGCGCCTA-3′ |

| erm(41) | Erythromycin ribosomal methylase | 5′-GACCGGGGCCTTCTTCGTGAT-3′ | 5′-GACTTCCCCGCACCGATTCC-3′ |

Table 3.

PCR products from differential regions for M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii clinical isolates and type strains

| M. abscessus locus | PCR product size (bp) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted |

Observed |

|||||||

| M. abscessus ATCC 19977T | M. massiliense CCUG 48898T |

M. abscessus |

M. massiliense |

M. bolletii |

||||

| ATCC 19977T | Clinical isolates | CCUG 48898T | Clinical isolates | CCUG 50184T | Clinical isolates | |||

| MAB_2396 | 1,486 | 740 | ∼1,500 and 500 | ∼1,500 and 500 | ∼750 | ∼750 | ∼750 | ∼750 |

| MAB_2697c | 1,049 | 449 | ∼1,000 | ∼1,000 and/or 500 faint | ∼450 | ∼450 | ∼1,000 | ∼1,000 |

| MAB_4751 | 1,338 | 444 | ∼1,400 faint and 500 | ∼1,400 faint and/or 500 | ∼450 | ∼450 or 375 | ∼500 and 400 | ∼500 and 400 or ∼500 |

| MAB_4792 | 1,124 | 605 | ∼1,200 | ∼1,200 or 650 | ∼600 | ∼600 | ∼1,200 | ∼1,200 |

| erm(41) | 700 | 350 | ∼700 | ∼700 | ∼350 | ∼350 or 700 | ∼700 | ∼700 |

PCR genotyping patterns of 46 clinical isolates were compared to those of M. abscessus ATCC 19977T, M. massiliense CCUG 48898T, and M. bolletii CCUG 50184T. A detailed description of the PCR products obtained for each of the clinical isolates, including 29 M. abscessus, 15 M. massiliense, and 2 M. bolletii isolates, is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. PCR products from almost all of the clinical isolates obtained with primers for MAB_2396 and MAB_2697c matched the patterns observed for the reference isolates. Interestingly, PCR primers targeting MAB_4751 produced either a 450-bp or 375-bp amplicon for the M. massiliense clinical isolates. The MAB_4751 region was found to be useful not only for the identification of M. massiliense but also for separation of this taxon into two distinct subgroups, subgroup I including CI510, CI71, CI72, CI73, CI76, CI1210, CI2040, and CI8182 and subgroup II including CI614, CI615, CI74, CI75, and CI122 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Primers targeting MAB_4792 also differentiated between the M. abscessus and M. massiliense isolates. In addition, M. abscessus clinical isolates were separated into two subgroups; subgroup I (CI63, CI65, CI82, CI128, CI1216, CI1219, and CI11220) showed a band at 650 bp, instead of the 1,200-bp product observed for the type strain and the remaining (subgroup II) clinical isolates, using primers targeting MAB_4792 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For M. bolletii, the type strain and clinical isolates CI59 and CI78 yielded PCR fragment sizes identical to those for M. abscessus with primer sets for MAB_2697c and MAB_4792 and fragment sizes identical to those for M. massiliense with the primers for MAB_2396 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The primers for MAB_4751 showed 500-bp and 400-bp bands for M. bolletii type strain and isolate CI59 and a 500-bp band for isolate CI78.

Identification of the tested clinical samples (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was considered unambiguous when the products obtained with all four primer pairs matched the patterns expected for the taxon. Our rapid PCR scheme was unambiguous in identification of the majority of the clinical isolates tested; however, two isolates showed product sizes not expected for the taxon in one of the PCRs. M. abscessus isolate CI1214 showed a 750-bp band for locus MAB_2396 (similar to M. massiliense or M. bolletii), and M. abscessus isolate CI121 showed 500- and 400-bp products (similar to M. bolletii) for locus MAB_4751.

Full-length erm(41) gene and inducible clarithromycin resistance among M. massiliense isolates.

A region of the erm(41) gene was amplified with primers that yielded a full-size product (∼700 bp) for the M. abscessus and M. bolletii type strains and a shorter product (∼350 bp) for the M. massiliense type strain, consistent with a previously described gene truncation (22, 24). Thirteen of 15 clinical isolates of M. massiliense showed the expected truncated erm(41) gene product of ∼350 bp. Surprisingly, two isolates (CI2040 and CI8182) showed products with sizes similar to the M. abscessus full-length erm(41) gene product size of ∼700 bp (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Sequencing of the erm(41) PCR product from M. massiliense strains CI2040 and CI8182 revealed 99.8% and 98.5% similarity, respectively, to the erm(41) gene of M. abscessus M93, 98.9% and 98.1% similarity, respectively, to the erm(41) gene of M. abscessus ATCC 19977T, and 98.7% similarity (for both strains) to the erm(41) gene of M. bolletii CCUG 50184T. In addition, these two novel erm(41) genes were 98.7% identical to each other. Sequence analysis showed the presence of the nucleotide T at position 28 in the erm(41) gene, which has been described for M. abscessus strains showing inducible clarithromycin resistance (30).

Inducible resistance was assessed in vitro by extended incubation of the organisms with clarithromycin (22). Clarithromycin susceptibility testing for these strains (CI2040 and CI8182) showed MIC values of 2 μg/ml (susceptible) at 5 days and >16 μg/ml (resistant) after 14 days, consistent with the presence of inducible resistance seen in the M. abscessus ATCC 19977 type strain. Partial amplification and sequencing of the rrl 23S rRNA gene from these isolates showed no mutations associated with clarithromycin resistance (22).

DISCUSSION

Differentiation among M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii is challenging for clinical microbiology laboratories. Recent work proved the inaccuracy of single-target sequencing for separating these three taxa within the M. abscessus group (11, 12). Sequencing of several targets (such as hsp65, rpoB, and secA1), combined with phylogenomic analysis, has been shown to increase identification accuracy among these different taxa (13). More recently, a multilocus sequence analysis targeting 8 housekeeping genes and a multispacer sequence analysis were reported (9, 16). However, all of these methods require genomic sequencing, which is relatively costly and time-consuming and may not be available in all clinical microbiology laboratories. We describe here a simple, accurate, robust, and cost-effective PCR-based method for distinguishing M. abscessus from M. massiliense and M. bolletii and subtyping M. abscessus and M. massiliense isolates. Although an array-based genomic approach was initially used to determine the features differentiating M. abscessus from M. massiliense and to design the assay, the actual genotyping method is PCR-based, requiring low-cost laboratory equipment, and was designed specifically for use by clinical laboratories.

Our genotyping method was able to rapidly and accurately identify 46 clinical isolates as M. abscessus, M. massiliense, or M. bolletii in agreement with sequence-based identification results (13). The robustness of the method is demonstrated by the combination of product sizes observed for each taxon. For example, primers for MAB_2396 and MAB_2697c were found to be useful in differentiating M. massiliense (750-bp and 450-bp products, respectively) from M. abscessus. The presence of a 375-bp or 450-bp product with primers for MAB_4751 not only identifies M. massiliense but also subtypes this taxon into two groups. A combination of differentiating primers for MAB_2396, MAB_2697, and MAB_4751, yielding product sizes of 750 bp, 1,000 bp, and 500 bp or 500/400 bp, respectively, separated M. bolletii from the other taxa within the M. abscessus group. One limitation of this study is that we did not have a large number of M. bolletii isolates to further validate the findings for this group.

Our previous work on these isolates (13) demonstrated at least two groups within M. massiliense, as determined by targeted sequencing and repetitive sequence-based PCR typing. We and other groups have shown that M. massiliense seems to be a genomically heterogeneous entity. Our genotyping scheme separated M. massiliense into two subgroups according to the product size of 450 bp or 375 bp obtained with the primer set for MAB_4751. This size difference is visually represented in Fig. 2 as a narrower dip segment (smaller loss of genome) in M. massiliense type strain CCUG 48898 and isolate CI76, yielding a PCR product of 450 bp, than in M. massiliense CI11 and CI154, which have a wider dip segment (larger loss of genome), yielding a PCR product of 375 bp. Interestingly, these two subgroups matched the two M. massiliense clusters in the phylogenomic analysis derived from concatenated hsp65, rpoB, and secA1 sequences in our previous study (13). Similarly, M. abscessus clinical isolates were separated into two subgroups based on the PCR product size for locus MAB_4792, which in general followed the clustering of the phylogenomic tree (13). Our rapid PCR scheme was unambiguous in the identification of the majority of the clinical isolates tested; however, two isolates showed product sizes not expected for the taxon in one of the PCRs. The M. abscessus isolate CI1214 showed a 750-bp band for locus MAB_2396 (similar to M. massiliense or M. bolletii). This strain was previously shown to be more divergent than most the M. abscessus isolates on the phylogenomic tree (13). M. abscessus isolate CI121 showed the 500- and 400-bp doublet products (similar to M. bolletii) for locus MAB_4751. These results should not be surprising, considering the requirement to sequence multiple targets for a consensus identification result using multilocus sequence analysis. They are also consistent with the observed phylogenetic trees derived from concatenated multilocus and whole-genome sequences of the M. abscessus group (7, 9), with some strains appearing “between” defined taxa, possibly due to horizontal gene transfer among members in the group.

Distinguishing M. massiliense from M. abscessus is clinically important because of their unique susceptibility patterns and treatment outcomes. The rates of clinical responses to therapy, including clarithromycin, are higher for patients with M. massiliense lung disease than for patients with M. abscessus lung disease (4). Clinically acquired resistance to clarithromycin in M. abscessus isolates occurs via point mutations to G at positions A2058 and A2059 of the rrl gene encoding the peptidyltransferase domain of the 23S rRNA (21) or by a drug-inducible mechanism via a functional erm(41) gene product (22). Partial sequencing of the rrl gene of the M. massiliense clinical isolates CI2040 and CI8182 revealed no mutations at these positions. On the other hand, sequence analysis of the erm(41) gene revealed a full-length gene product, which has not been previously reported for M. massiliense. In addition, it showed the characteristic nucleotide T (instead of C) at nucleotide position 28 previously described for M. abscessus with inducible clarithromycin resistance (30). Most importantly, susceptibility testing confirmed the presence of inducible clarithromycin resistance in both M. massiliense strains.

The M. massiliense erm(41) gene includes several mutations, including a large C-terminal deletion that renders it nonfunctional. Analysis of the size differences of the products obtained with erm(41) PCR was proposed as a simple method to differentiate M. massiliense from M. abscessus and M. bolletii species (23, 24). Our genotyping scheme combined with erm(41) PCR revealed two M. massiliense isolates, CI2040 and CI8182, harboring full-length erm(41) PCR products. We conclude that erm(41) PCR alone is insufficient to differentiate M. massiliense from M. abscessus. It is tempting to speculate regarding possible explanations for a full-length erm gene in clinical isolates of M. massiliense. Horizontal gene transfer of rpoB sequences has been shown to occur within members of the M. abscessus group (9), so one intriguing possibility is that the erm(41) gene was transferred from M. abscessus or M. bolletii into M. massiliense, resulting in a similar phenotype. Consistent with horizontal gene transfer is the presence of a full-length erm(41) gene in CI2040 and CI8182 clinical isolates which are most similar to the erm(41) genes of M. abscessus M93 and ATCC 19977T, while hsp65, rpoB, and secA1 sequences are most similar to those of M. massiliense type strain CCUG 48898. Also consistent with horizontal gene transfer is the presence of the 750-bp band for locus MAB_2396 (similar to M. massiliense or M. bolletii) for M. abscessus isolate CI1214 and the 500- and 400-bp products (similar to M. bolletii) for locus MAB_4751 in M. abscessus isolate CI121. While the molecular mechanisms used by these organisms to recombine foreign DNA into their genomes are not completely understood, the occurrence of different members of the M. abscessus group, as well as other species, coinfecting the same patient provides opportunities for direct exchange of genetic material. The use of a small set of core genes for typing cannot reveal all horizontal gene transfer events that occur, but including key determinants such as antibiotic resistance determinants within the typing scheme can help track transfer events that directly affect therapy.

Our PCR-based genotyping method using four primer pairs for the identification of M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. bolletii, combined with detection of full-length or truncated erm(41) for inducible clarithromycin resistance, can provide useful information for physicians. Moreover, the genotyping protocol provides initial subtyping information for M. massiliense and M. abscessus and highlights possible events of horizontal gene transfer, both of which can be further explored by genomic sequencing. The incorporation of this assay into the workflow of the mycobacteriology laboratory has led to a decrease in the need for multitarget genome sequencing for identification and typing of the M. abscessus group. Our protocol does not require an expensive platform such as a sequencing system or MALDI-TOF MS instrument. It is a relatively simple technique with direct visual results. The turnaround time is about 3 to 4 h from isolation of the organism. The estimated cost of PCR and running the PCR product on an agarose gel is less than $2 per isolate.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Qin Su for expert microarray sample processing and hybridizations.

The Intramural Research Program of the NIH, the NIH Clinical Center, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases supported this research. H.T. was supported in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (contract HHSN272200900007C).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01132-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr 2002. Clinical and taxonomic status of pathogenic nonpigmented or late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:716–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marras TK, Daley CL. 2002. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Chest Med. 23:553–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan ED, Bai X, Kartalija M, Orme IM, Ordway DJ. 2010. Host immune response to rapidly growing mycobacteria, an emerging cause of chronic lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 43:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee SH, Park YK, Kim CK, Shin SJ, Huitt GA, Daley CL, Kwon OJ. 2011. Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183:405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leao SC, Viana-Niero C, Matsumoto CK, Lima KV, Lopes ML, Palaci M, Hadad DJ, Vinhas S, Duarte RS, Lourenco MC, Kipnis A, das Neves ZC, Gabardo BM, Ribeiro MO, Baethgen L, de Assis DB, Madalosso G, Chimara E, Dalcolmo MP. 2010. Epidemic of surgical-site infections by a single clone of rapidly growing mycobacteria in Brazil. Future Microbiol. 5:971–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aitken ML, Limaye A, Pottinger P, Whimbey E, Goss CH, Tonelli MR, Cangelosi GA, Dirac MA, Olivier KN, Brown-Elliott BA, McNulty S, Wallace RJ., Jr 2012. Respiratory outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense in a lung transplant and cystic fibrosis center. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185:231–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Greaves D, Foweraker J, Roddick I, Inns T, Reacher M, Haworth CS, Curran MD, Harris SR, Peacock SJ, Parkhill J, Floto RA. 2013. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 381:1551–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leao SC, Tortoli E, Viana-Niero C, Ueki SY, Lima KV, Lopes ML, Yubero J, Menendez MC, Garcia MJ. 2009. Characterization of mycobacteria from a major Brazilian outbreak suggests that revision of the taxonomic status of members of the Mycobacterium chelonae-M. abscessus group is needed. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2691–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macheras E, Roux AL, Bastian S, Leao SC, Palaci M, Sivadon-Tardy V, Gutierrez C, Richter E, Rusch-Gerdes S, Pfyffer G, Bodmer T, Cambau E, Gaillard JL, Heym B. 2011. Multilocus sequence analysis and rpoB sequencing of Mycobacterium abscessus (sensu lato) strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:491–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leao SC, Tortoli E, Euzeby JP, Garcia MJ. 2011. Proposal that Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii be united and reclassified as Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii comb. nov., designation of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus subsp. nov. and emended description of Mycobacterium abscessus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61:2311–2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HY, Kook Y, Yun YJ, Park CG, Lee NY, Shim TS, Kim BJ, Kook YH. 2008. Proportions of Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii strains among Korean Mycobacterium chelonae-Mycobacterium abscessus group isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3384–3390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macheras E, Roux AL, Ripoll F, Sivadon-Tardy V, Gutierrez C, Gaillard JL, Heym B. 2009. Inaccuracy of single-target sequencing for discriminating species of the Mycobacterium abscessus group. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2596–2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelazny AM, Root JM, Shea YR, Colombo RE, Shamputa IC, Stock F, Conlan S, McNulty S, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ, Jr, Olivier KN, Holland SM, Sampaio EP. 2009. Cohort study of molecular identification and typing of Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium massiliense, and Mycobacterium bolletii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1985–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi GE, Chang CL, Whang J, Kim HJ, Kwon OJ, Koh WJ, Shin SJ. 2011. Efficient differentiation of Mycobacterium abscessus complex isolates to the species level by a novel PCR-based variable-number tandem-repeat assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1107–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong YL, Ong CS, Ngeow YF. 2012. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium abscessus based on tandem-repeat polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3084–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sassi M, Ben Kahla I, Drancourt M. 2013. Mycobacterium abscessus multispacer sequence typing. BMC Microbiol. 13:3. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saleeb PG, Drake SK, Murray PR, Zelazny AM. 2011. Identification of mycobacteria in solid-culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1790–1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotz A, Ferroni A, Beretti JL, Dauphin B, Carbonnelle E, Guet-Revillet H, Veziris N, Heym B, Jarlier V, Gaillard JL, Pierre-Audigier C, Frapy E, Berche P, Nassif X, Bille E. 2010. Rapid identification of mycobacterial whole cells in solid and liquid culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:4481–4486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hettick JM, Kashon ML, Slaven JE, Ma Y, Simpson JP, Siegel PD, Mazurek GN, Weissman DN. 2006. Discrimination of intact mycobacteria at the strain level: a combined MALDI-TOF MS and biostatistical analysis. Proteomics 6:6416–6425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignone M, Greth KM, Cooper J, Emerson D, Tang J. 2006. Identification of mycobacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1963–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace RJ, Jr, Meier A, Brown BA, Zhang Y, Sander P, Onyi GO, Bottger EC. 1996. Genetic basis for clarithromycin resistance among isolates of Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1676–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nash KA, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr 2009. A novel gene, erm(41), confers inducible macrolide resistance to clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus but is absent from Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1367–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blauwendraat C, Dixon GL, Hartley JC, Foweraker J, Harris KA. 2012. The use of a two-gene sequencing approach to accurately distinguish between the species within the Mycobacterium abscessus complex and Mycobacterium chelonae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:1847–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HY, Kim BJ, Kook Y, Yun YJ, Shin JH, Kim BJ, Kook YH. 2010. Mycobacterium massiliense is differentiated from Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium bolletii by erythromycin ribosome methyltransferase gene (erm) and clarithromycin susceptibility patterns. Microbiol. Immunol. 54:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada T, Akiyama Y, Kurashima A, Nagai H, Tsuyuguchi K, Fujii T, Yano S, Shigeto E, Kuraoka T, Kajiki A, Kobashi Y, Kokubu F, Sato A, Yoshida S, Iwamoto T, Saito H. 2012. Clinical and microbiological differences between Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium massiliense lung diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3556–3561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venkatraman ES, Olshen AB. 2007. A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics 23:657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132:365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CLSI 2011. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard—second edition, p 14. CLSI document M24-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastian S, Veziris N, Roux AL, Brossier F, Gaillard JL, Jarlier V, Cambau E. 2011. Assessment of clarithromycin susceptibility in strains belonging to the Mycobacterium abscessus group by erm(41) and rrl sequencing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:775–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.