Abstract

Here, we investigate the endosymbiotic microbiota of the Macrosteles leafhoppers M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus, known as vectors of phytopathogenic phytoplasmas. PCR, cloning, sequencing, and phylogenetic analyses of bacterial 16S rRNA genes identified two obligate endosymbionts, “Candidatus Sulcia muelleri” and “Candidatus Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” and five facultative endosymbionts, Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Burkholderia, Diplorickettsia, and a novel bacterium belonging to the Rickettsiaceae, from the leafhoppers. “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” exhibited 100% infection frequencies in the host species and populations and were separately harbored within different bacteriocytes that constituted a pair of coherent bacteriomes in the abdomen of the host insects, as in other deltocephaline leafhoppers. Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Burkholderia, Diplorickettsia, and the novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium exhibited infection frequencies at 7%, 31%, 12%, 0%, and 24% in M. striifrons and at 20%, 0%, 0%, 20%, and 0% in M. sexnotatus, respectively. Although undetected in the above analyses, phytoplasma infections were detected in 16% of M. striifrons and 60% of M. sexnotatus insects by nested PCR of 16S rRNA genes. Two genetically distinct phytoplasmas, namely, “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris,” associated with aster yellows and related plant diseases, and “Candidatus Phytoplasma oryzae,” associated with rice yellow dwarf disease, were identified from the leafhoppers. These results highlight strikingly complex endosymbiotic microbiota of the Macrosteles leafhoppers and suggest ecological interactions between the obligate endosymbionts, the facultative endosymbionts, and the phytopathogenic phytoplasmas within the same host insects, which may affect vector competence of the leafhoppers.

INTRODUCTION

Leafhoppers, belonging to the insect order Hemiptera, the family Cicadellidae, embrace over 20,000 described species in the world. These hemimetabolous insects have needle-like mouthparts and feed exclusively on plant sap throughout their life. Through the feeding habit, these leafhoppers not only directly damage their host plants but also vector phytopathogenic viruses, bacteria, and fungi and are therefore recognized as notorious agricultural and horticultural pests (1, 2).

Living exclusively on plant phloem or xylem fluid imposes serious nutritional difficulties on the sap-feeding insects. Plant sap may contain some levels of carbohydrates, mainly in the form of sucrose, but is generally devoid of lipids and proteins. Most lipids can be synthesized from carbohydrates, but proteins cannot be synthesized in the absence of nitrogenous precursors such as essential amino acids. Some amino acids may be present in plant sap, but they are mostly nonessential ones. Therefore, most plant-sucking hemipteran insects are associated with symbiotic microorganisms that provide essential amino acids and other nutrients (3–5).

While early microscopic observations consistently identified bacteriome-associated and other bacterial endosymbionts in diverse leafhoppers of the family Cicadellidae (6, 7), modern microbiological characterization has been conducted on a relatively small number of leafhopper species. The ancient bacteriome endosymbiont “Candidatus Sulcia muelleri” is highly conserved not only among leafhoppers but also across cicadas, froghoppers, treehoppers, planthoppers, and other hemipteran insects and exhibits host-symbiont cospeciation, drastic genome reduction, and an ancient origin of the endosymbiosis dating back to 260 million years ago (8, 9). In the glassy-winged sharpshooter Homalodisca coagulata and allied insects of the subfamily Cicadellinae, another endosymbiont, “Candidatus Baumannia cicadellinicola,” coexists with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” in the same bacteriomes and also exhibits host-symbiont cospeciation and drastic genome reduction (10–12). In the leafhoppers Nephotettix cincticeps and Matsumuratettix hiroglyphicus of the subfamily Deltocephalinae, “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” coexists with a different endosymbiont, “Candidatus Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” within the same bacteriomes (13, 14). In addition to these bacteriome-associated endosymbionts of obligate nature, various endosymbionts of facultative nature, such as Wolbachia (11, 15–17), Rickettsia (13, 18), Spiroplasma (19, 20), Cardinium (21, 22), and others (23, 24), have been sporadically recorded from some leafhoppers, although these surveys are not systematic but rather fragmentary, giving no coherent picture of endosymbiotic microbiota in specific leafhopper species and populations.

Recently, it has been reported that some facultative endosymbionts, such as Hamiltonella, Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, Regiella, Serratia, and others, confer resistance on their host insects against parasitic wasps and nematodes and pathogenic fungi and viruses (25–31). In particular, the discovery of Wolbachia-mediated suppression of mosquitoes' vector competence against dengue virus, malaria plasmodium, filarial nematodes, and other insect-borne pathogens (32, 33) has boosted studies and trials toward symbiont-mediated control of insect-vectored human and animal diseases (34–36).

In principle, similar symbiont-mediated controlling approaches may be applicable to insect-vectored plant diseases. The cicadellid leafhoppers are notorious as vectoring phytopathogenic viruses (37) and bacterial plant pathogens of the genus Phytoplasma (38). Phytoplasmas are noncultivable degenerate bacteria of the class Mollicutes, obligatorily associated with plant phloem tissues, vectored by plant-sucking insects, and causing more than 700 diseases in hundreds of plant species. Notably, more than 70% of phytoplasma vectors are leafhoppers of the subfamily Deltocephalinae, including Nephotettix cincticeps for rice yellow dwarf disease; Matsumuratettix hiroglyphicus for sugarcane white leaf disease; Macrosteles striifrons for garland chrysanthemum witches' broom, mitsuba witches' broom, onion yellows, tomato yellows, and other diseases; Macrosteles sexnotatus for aster yellows, etc. (38, 39). Hence, the facultative endosymbiotic microbiota of these deltocephaline leafhoppers is not only of microbiological interest but also of practical relevance.

Here, we performed a detailed investigation of endosymbiotic microbiota of the leafhoppers M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus, which unveiled complex microbial communities consisting of two obligate endosymbionts, five facultative endosymbionts, and two distinct phytoplasmas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insects.

A laboratory strain of M. striifrons, originating from Mito, Ibaraki, Japan, was maintained on the garland chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum coronarium, at 25°C under a long-day regimen of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark. The other samples of M. striifrons were collected by sweeping of grass fields as follows: in Gifu, Gifu, Japan, on 2 September 2011; in Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japan, on 29 September 2011; and in Osaka, Osaka, Japan, on 18 August 2011. The samples of M. sexnotatus were similarly collected in Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japan, on 29 September 2011. These insect samples were preserved in acetone until use (40).

DNA analysis.

The insects were individually dissected in a petri dish filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4]) with fine forceps under a dissection microscope. Each of the dissected bacteriomes and ovaries was crushed and digested in a 1.5-ml plastic tube with a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.2 mg/ml protease K) at 56°C for 2 h. DNA was extracted from the lysate with phenol and chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, dried, and dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 mM EDTA). Endosymbiont-derived bacterial 16S rRNA gene segments were amplified by PCR using the primer sets listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Some of the PCR products were subjected to cloning, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) genotyping, and DNA sequencing as described previously (41).

Molecular phylogenetic analysis.

Multiple alignments of the nucleotide sequences were generated using the program MAFFT 5 (42). The GTR + I + G substitution model was selected using the program JMODELTEST (43). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted by maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian (BA) methods using the programs RAxML version 7.2.1 (44) and MrBayes 3.1.2 (45), respectively. Bootstrap tests were conducted by 1,000 resamplings for ML. Posterior probabilities were calculated for each node that was used for statistical evaluation in BA analysis.

In situ hybridization.

The legs of the insects were removed in PBS to facilitate permeation of reagents into the tissues. After fixation in Carnoy's solution (ethanol-chloroform-acetic acid, 6:3:1) overnight on a shaker, the insects were treated with 6% hydrogen peroxide in 80% ethanol for several weeks to quench autofluorescence of the tissues (46). After thorough washing with 100% ethanol and PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (PBST), the samples were incubated with hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.9 M NaCl, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 30% formamide) three times for 10 min each. Then, the samples were hybridized with the hybridization buffer containing 100 nM (each) probes Macrosteles-Sulcia16R1-A647 (5′-Alexa Fluor 647-CCT CAG GCT ATT CCT CAG C-3′) and Macrosteles-beta16R1-A555 (5′-Alexa Fluor 555-CTC AAT CTT GCG ATA TTG CAA CT-3′) overnight. After thorough washing with PBST, the samples were counterstained with 0.5 μM SYTOX green, mounted with Slowfade antifade solution (Invitrogen), and observed under a fluorescence dissecting microscope (M165 FC; Leica Microsystems) and a laser confocal microscope (Pascal 5; Carl Zeiss).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers AB795320 to AB795359 and AB819331 to AB819337.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

M. striifrons, M. sexnotatus, and their bacteriomes.

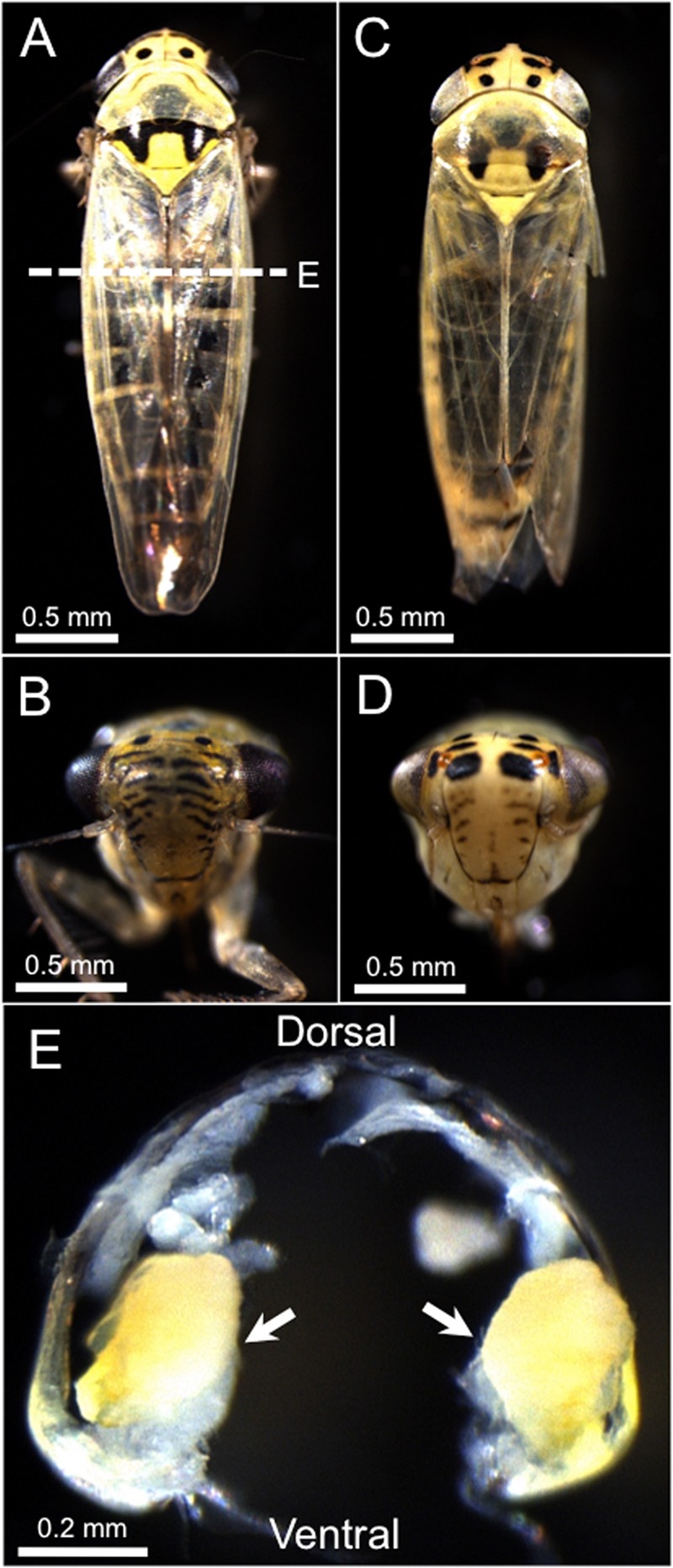

M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus are closely related leafhopper species. Although their morphological traits are very similar, they are externally distinguishable on the basis of black marking patterns on their head and thorax (Fig. 1A to D). Within their body cavity, paired yellow bacteriomes are present on both sides of the abdomen (Fig. 1E).

Fig 1.

The leafhoppers Macrosteles striifrons and Macrosteles sexnotatus. (A and B) External appearance of an adult insect of M. striifrons. (C and D) External appearance of an adult insect of M. sexnotatus. (E) Bacteriomes on both side of the abdominal body cavity of M. striifrons. The cross section of the abdomen corresponds to the dashed line in panel A.

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacteriome and ovary of M. striifrons.

Adult females of a laboratory strain of M. striifrons, which originated from Mito, Japan, were dissected, and their bacteriomes and ovaries were subjected to DNA extraction. Field-collected adult females of M. striifrons from Gifu and Takamatsu, Japan, were also subjected to tissue dissection and DNA extraction. These DNA samples were subjected to PCR amplification of a 1.5-kb region of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers, the PCR products were cloned, the clones were randomly picked and subjected to RFLP genotyping, and representatives of each RFLP genotype were sequenced. Table 1 summarizes these results. From all the bacteriome samples representing three M. striifrons populations, the same RFLP genotype, designated type A, was predominantly detected, whereas diverse minor genotypes, namely, type B and type C from the Mito population, type D from the Gifu population, and type E from the Takamatsu population, were additionally identified, respectively. From the ovary samples representing the Gifu and Takamatsu populations, type A also dominated, while type B was more frequently detected than type A from the ovary samples representing the Mito population. In addition, the following minor genotypes were identified: type D from the Gifu population, type E from the Takamatsu population, and type C and type F from the Mito population. The type A clones yielded the same 1,449-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits included “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbiont from the leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (97.6% [1,436/1,471] sequence identity; accession number AB702993). The type B clones exhibited the same 1,473-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits contained Rickettsia rhipicephali from the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (90.1% [1,281/1,422]; accession no. CP003342). The type C clones showed the same 1,421-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits were represented by Rickettsia bellii from the tick Dermacentor variabilis (98.7% [1,402/1,421]; accession no. CP000087). The type D clones yielded the same 1,426-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits included the Wolbachia endosymbiont from the stinkbug Nysius expressus (99.6% [1,421/1,426]; accession no. JQ726767). The type E clones exhibited the same 1,453-bp sequence, whose top BLASTN hits contained Burkholderia fungorum from oil refinery wastewater (100% [1,453/1,453]; accession no. HM113360). The sole type F clone was a 1,387-bp sequence, whose top BLASTN hit was the “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” endosymbiont from the leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (89.9% [1,211/1,347]; accession no. AB702994) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene clones obtained from the Macrosteles leafhoppers

| Species | Localitya | Sampleb | Tissuec | No. of clonesd | Detected bacteriae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrosteles striifrons | Mito, Ibarakif | Adult, female, n = 5 | Bac | 83 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 64 (30); Rickettsia, 4 (4); novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium, 15 (15) |

| Ov | 71 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 13 (7); “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” 1 (1); Rickettsia, 3 (3); novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium, 54 (20) | |||

| Gifu, Gifug | Adult, female, n = 5 | Bac | 100 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 64 (1); Wolbachia, 4 (4) | |

| Ov | 96 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 76 (1); Wolbachia, 20 (20) | |||

| Takamatsu, Kagawag | Adult, female, n = 4 | Bac | 69 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 67 (1); Burkholderia, 2 (2) | |

| Ov | 61 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 53 (1); Burkholderia, 8 (8) | |||

| Macrosteles sexnotatus | Takamatsu, Kagawag | Adult, female, n = 4 | Bac | 48 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 36 (3); Rickettsia, 20 (20); Diplorickettsia, 9 (9); Pantoea, 3 (3); Wolbachia, 1 (1) |

| Ov | 58 | “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” 19 (3); Rickettsia, 14 (14); Diplorickettsia, 6 (6); Pantoea, 6 (6); Erwinia, 3 (3); Pseudomonas, 3 (3); Xanthomonas, 3 (3); Propionibacterium, 2 (2); Exiguobacterium, 1 (1); Providencia, 1 (1) |

All localities are in Japan.

Stage, sex, and number of insects examined.

Bac, bacteriome; Ov, ovary.

Number of 16S rRNA gene clones subjected to RFLP genotyping.

Bacterial taxon followed by number of RFLP-genotyped clones (number of sequenced clones). Each bacterial taxon was designated after the bacterial genus of the BLAST top hit with >95% sequence identity, except for “novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium,” whose closely allied sequences were not found in the DNA databases.

Laboratory-maintained insect strain.

Field-collected insect samples.

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacteriome and ovary of M. sexnotatus.

Field-collected adult females of M. sexnotatus from Takamatsu, Japan, were similarly subjected to tissue dissection, DNA extraction, PCR, cloning, RFLP genotyping, and sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. In both the bacteriome and ovary samples, the type A genotype was the most predominant, as in M. striifrons, whereas distinct RFLP genotypes, designated type G and type H, were subsequently dominant. From M. sexnotatus, in addition, a number of minor RFLP genotypes of 16S rRNA clones were identified, which are summarized briefly in Table 1. The type A clones yielded the same 1,449-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits included “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbiont from the leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (97.6% [1,436/1,471]; accession no. AB702993). The type G clones exhibited the same 1,421-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hits contained Rickettsia raoultii from the tick Dermacentor sp. (98.9% [1,405/1,421]; accession no. DQ365809). The type H clones showed the same 1,488-bp sequence, whose BLASTN top hit was Diplorickettsia massiliensis from the tick Ixodes ricinus (99.1% [1,474/1,488]; accession no. GQ857549). The other minor genotype clones were identified as follows: a 1,426-bp sequence from the bacteriome with a top BLASTN hit to the Wolbachia endosymbiont of the stinkbug Nysius expressus (99.4% [1,418/1,426]; accession no. JQ726767); a 1,336-bp sequence from the bacteriome with a top BLASTN hit to Pantoea eucrina from soil (99.8% [1,333/1,336]; accession no. HE659514); a 1,338-bp sequence from the bacteriome with a top BLASTN hit to Pantoea eucrina from soil (99.6% [1,333/1,338]; accession no. HE659514); a 1,371-bp sequence from the bacteriome with a top BLASTN hit to Erwinia sp. from soil (99.8% [1,368/1,371]; accession no. JQ612529); a 1,465-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pantoea eucrina from soil (99.8% [1,463/1,466]; accession no. HE659514); a 1,465-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pantoea eucrina from soil (99.5% [1,458/1,466]; accession no. HE659514); a 1,465-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pantoea eucrina from soil (99.5% [1,459/1,466]; accession no. HE659514); a 1,355-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Providencia rettgeri from fish (99.7% [1,351/1,355]; accession no. JX136696); a 1,358-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Exiguobacterium sp. from soil (100% [1,357/1,357]; accession no. JF772578); a 1,447-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Propionibacterium acnes from human skin (100% [1,447/1,447]; accession no. NR_074675); a 1,447-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Propionibacterium acnes from human skin (99.9% [1,446/1,447]; accession no. NR_074675); a 1,381-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pseudomonas oryzihabitans from rice paddy (99.8% [1,378/1,381]; accession no. AB681726); a 1,459-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pseudomonas sp. (99.8% [1,457/1,459]; accession no. HQ728560); a 1,459-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Pseudomonas sp. from the thrips Frankliniella schultzei (100% [1,459/1,459]; accession no. JN793859); and a 1,348-bp sequence from the ovary with a top BLASTN hit to Xanthomonas albilineans from sugarcane (99.6% [1,342/1,348]; accession no. NR_074403) (Table 1).

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences from M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus.

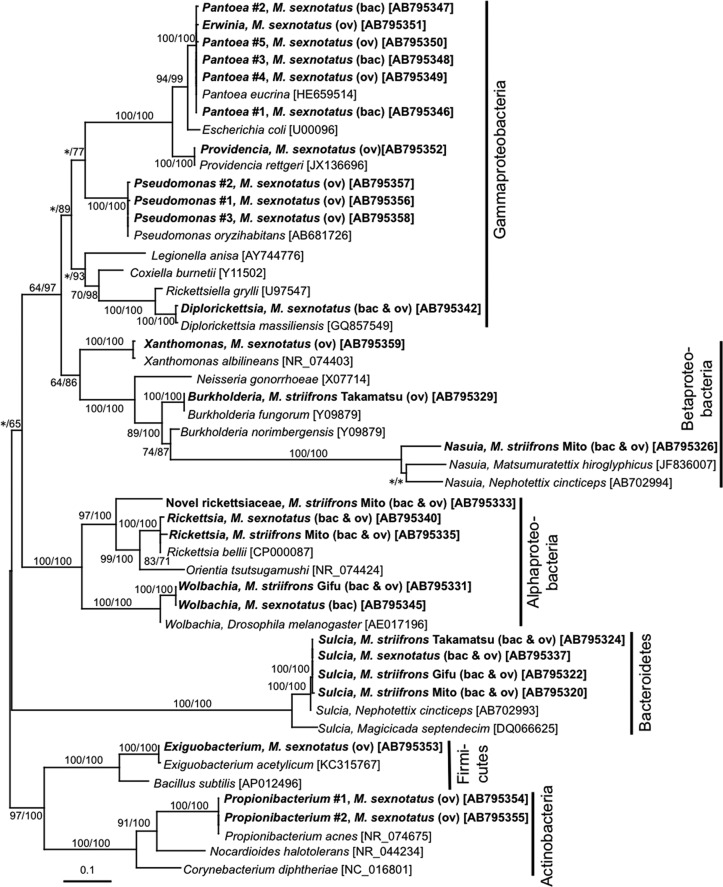

Figure 2 shows phylogenetic placements of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from the dissected bacteriomes and ovaries of M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus. The phylogenetic patterns generally agreed with the BLASTN search results: the type A sequence in the clade of “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” (Bacteroidetes) endosymbionts of hemipteran insects; the type C sequence in the clade of the genus Rickettsia (Alphaproteobacteria), the type D sequence in the clade of Wolbachia (Alphaproteobacteria) endosymbionts of diverse arthropods, the type E sequence in the clade of the genus Burkholderia (Betaproteobacteria), the type F sequence in the clade of “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” (Betaproteobacteria) endosymbionts of leafhoppers of the subfamily Deltocephalinae, the type G sequence in the clade of the genus Rickettsia (Alphaproteobacteria), and the type H sequence closely allied to Diplorickettsia massiliensis (Gammaproteobacteria). Notably, the type B sequence was placed not inside but outside the clade of the genus Rickettsia in the Alphaproteobacteria. The minor bacterial sequences obtained from M. sexnotatus were clustered with Pantoea, Erwinia, Providencia, Pseudomonas, Xanthomonas (Gammaproteobacteria), Wolbachia (Alphaproteobacteria), Exiguobacterium (Firmicutes), and Propionibacterium (Actinobacteria), respectively, as suggested by the BLASTN searches (Fig. 2). Here, more detailed phylogenetic analyses of each of the clades are presented.

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic placement of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from the Macrosteles leafhoppers. A maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogeny inferred from 1,147 aligned nucleotide sites is shown, while Bayesian (BA) analysis gave substantially the same result. Bootstrap probabilities for the ML analysis and posterior probabilities for the BA analysis at 50% or higher are shown at the nodes. Asterisks indicate support values lower than 50%. The sequences obtained from the leafhoppers in this study are highlighted by boldface type, where bacterial taxon, leafhopper species and origin, leafhopper tissue(s) in parentheses (bac, bacteriome; ov, ovary), and nucleotide sequence accession number in brackets are indicated. Scale bar shows branch length in terms of number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Bacterial phyla and classes are indicated on the right side.

“Ca. Sulcia muelleri.”

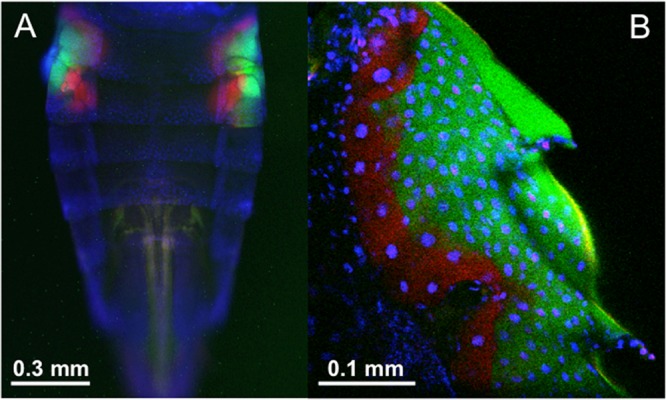

Diverse plant-sucking insects of the order Hemiptera, which embraces cicadas, spittlebugs, leafhoppers, planthoppers, and many others, are ubiquitously associated with an ancient clade of Bacteroidetes endosymbionts of the genus “Ca. Sulcia,” where the intimate host-symbiont association and cospeciation are estimated to date back to 260 million years ago (9). The type A sequences representing three M. striifrons populations and an M. sexnotatus population formed a compact clade within the monophyletic group of “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbionts with 100% statistical support (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In particular, they were closely allied to “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbionts of Macrosteles, Nephotettix, and Ecultanus leafhoppers of the same subfamily, Deltocephalinae (see Fig. S1), reflecting the host-symbiont phylogenetic concordance. In Nephotettix cincticeps, it was demonstrated that the “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbiont is localized in a pair of bacteriomes in the abdomen (13). Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed similar tissue localization of the “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbiont in paired bacteriomes in the abdomen of M. striifrons (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization of the endosymbionts “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” within the bacteriomes of the leafhopper M. striifrons. (A) Epifluorescence image of the whole abdomen. (B) Confocal image of the bacteriome. Red, green, and blue signals indicate “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” and host nuclear DNA, respectively. Note that insect cuticle also emits autofluorescence colored as green in panel B.

“Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola.”

From leafhoppers of the subfamily Deltocephalinae, namely, Nephotettix cincticeps and Matsumuratettix hiroglyphicus, betaproteobacterial “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” endosymbionts have been reported (13, 14). In this study, PCR, cloning, and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene sequences identified only a clone of type F, “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola”-allied sequence from a population of M. striifrons (Table 1). However, we found that, probably because of highly AT-rich “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” genes and consequent primer mismatches, PCR amplification and cloning of the 16S rRNA gene of “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” from Nephotettix cincticeps were quite inefficient (13). Hence, we designed internal “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola”-specific primers on the basis of the single “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” sequence obtained from M. striifrons (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), with which we successfully amplified and sequenced the 16S rRNA gene of “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” endosymbionts representing the other two M. striifrons populations and an M. sexnotatus population. These sequences formed a monophyletic group with the “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” sequences from other deltocephaline leafhoppers with 100% statistical support (see Fig. S2). In Nephotettix cincticeps, it was shown that the “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” endosymbiont and the “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” endosymbiont are localized in the same bacteriomes but separately in different regions of the symbiotic organs (13). Fluorescence in situ hybridization identified similar localization patterns of the “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” endosymbionts in the bacteriomes of M. striifrons (Fig. 3).

Wolbachia.

The majority of insects and other arthropods are associated with endosymbiotic alphaproteobacteria of the genus Wolbachia, which are known for causing various phenotypic effects on their hosts, including parthenogenesis induction, feminization, cytoplasmic incompatibility, and male killing (47), and thereby prevailing among 40 to 70% of millions of insect species (48, 49). The type D sequence from an M. striifrons population was placed in the clade of Wolbachia endosymbionts of the B supergroup supported by nearly 100% statistical values, with allied Wolbachia sequences from the rice planthoppers Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The sole Wolbachia sequence obtained from M. sexnotatus was also allied to these Wolbachia sequences (see Fig. S3). While Wolbachia-induced feminization in the leafhopper Zyginidia pullula (16) and Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in the rice planthoppers (50, 51) have been reported, phenotypic effects of the Wolbachia endosymbionts on Macrosteles leafhoppers are currently unknown and deserve future studies.

Rickettsia.

Endocellular alphaproteobacteria of the genus Rickettsia have been, for a long time, recognized as human and animal pathogens, which cause spotted fever, epidemic typhus, and other diseases and are vectored by ticks, lice, and other blood-sucking arthropods (52). However, recent studies have revealed that diverse insects, ticks, leeches, and amoebae constantly harbor Rickettsia endosymbionts of either parasitic, commensalistic, or beneficial nature at considerable infection frequencies (53, 54). The C type sequence from a population of M. striifrons and the G type sequence from M. sexnotatus constituted distinct lineages in the Rickettsia clade (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). A Rickettsia endosymbiont was also reported from the rice green leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (13). These phylogenetic patterns suggest multiple evolutionary origins of the Rickettsia endosymbionts among deltocephaline leafhoppers. Phenotypic effects of these Rickettsia endosymbionts on the leafhopper hosts are unknown.

Novel endosymbiont belonging to the family Rickettsiaceae.

The B type sequence, which was detected from both the bacteriome and ovary samples of M. striifrons representing the Mito population at considerable frequencies, was placed in the alphaproteobacterial order Rickettsiales, but not within the genus Rickettsia. Its placement was outside the genera Rickettsia and Orientia in the family Rickettsiaceae, constituting a distinct lineage with no closely allied 16S rRNA gene sequences in the DNA databases (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that the B type sequence may represent a novel bacterial taxon in the family Rickettsiaceae. Judging from the high detection frequency in the ovary of M. striifrons (54/71 [76.1%] clones examined) (Table 1), this bacterium is quite likely transmitted to the next host generation via ovarial passage vertically. Other microbiological traits of the novel Rickettsiaceae endosymbiont are of interest and deserve future studies.

Diplorickettsia.

The European sheep tick Ixodes ricinus is the most prevalent tick species in central Europe and is known to vector a number of human and animal pathogens such as Borrelia spp., Rickettsia helvetica, Rickettsia monacensis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia spp., Francisella tularensis, and others (55). Recently, a novel endocellular gammaproteobacterium was isolated from I. ricinus using mammalian and amphibian cell lines, which was allied to insect endosymbionts and pathogens of the genus Rickettsiella in the order Legionellales and was designated Diplorickettsia massiliensis (56). A large-scale serological survey detected three Diplorickettsia-positive cases of over 13,000 human serum samples (57), indicating its potential relevance to human health. Unexpectedly, the type H sequence identified from M. sexnotatus was nearly identical to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of D. massiliensis and thus was regarded as a new member of the genus Diplorickettsia (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). To our knowledge, this study is the second report of Diplorickettsia and the first report of an insect-associated Diplorickettsia.

Burkholderia.

Members of the betaproteobacterial genus Burkholderia are major soil bacteria that are most commonly found on plant roots, in adjacent areas, and in other moist environments (58). Some Burkholderia species and strains possess dinitrogen-fixing ability (59), some are capable of nodulating leguminous plant roots (60), some are associated with plant galls (61), and others promote plant growth and suppress plant diseases (62, 63). Notably, it was reported that some Burkholderia lineages are associated with stinkbugs of the superfamilies Lygaeoidea and Coreoidea as specific and beneficial symbiotic bacteria, which are orally acquired by nymphal host insects from the environment every generation, are localized in a specific region of the posterior midgut, and facilitate growth and reproduction of the host insects (64–67). The E type sequence from a population of M. striifrons was placed in the Burkholderia clade (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The Burkholderia bacterium detected from M. striifrons may be either an environmental contaminant or a gut microbe, but on account of its detection from the bacteriomes and the ovaries (Table 1), the possibility that it may represent a previously unknown type of vertically transmitted Burkholderia endosymbiont cannot be ruled out and deserves future experimental verification.

Other bacteria.

The other bacterial sequences detected from the field-collected samples of M. sexnotatus were generally of low frequencies and genetically polymorphic, phylogenetically clustering with such free-living bacterial species as Pantoea eucrina, Pseudomonas oryzihabitans, Providencia rettgeri, Xanthomonas albilineans, Exiguobacterium acetylicum, and Propionibacterium acnes, respectively (Fig. 2). Probably, these bacteria represent either components of the gut microbiota, casual gut associates taken upon feeding, or contaminants on the insect surface. For example, Pantoea spp. have been frequently identified as insect gut bacteria (68), Pseudomonas oryzihabitans was originally isolated from a rice paddy (69) and is likely associated with grass fields, and Propionibacterium acnes is a common skin microbe (70) and is likely a human-derived contaminant.

Diagnostic PCR detection of the bacterial endosymbionts from M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus.

Table 2 shows diagnostic PCR detection of the bacterial endosymbionts from 68 individuals of M. striifrons representing four populations and 5 individuals of M. sexnotatus representing a population. “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” consistently exhibited 100% infection frequencies irrespective of the host species and populations, reflecting their essential biological roles for the host insects as obligate nutrition-providing bacteriome-associated endosymbionts (9, 13). Meanwhile, the other bacteria exhibited partial infection frequencies in the host populations: Wolbachia in 7.4% (5/68) of M. striifrons and 20.0% (1/5) of M. sexnotatus insects, Rickettsia in 30.9% (21/68) of M. striifrons and 0% (0/5) of M. sexnotatus insects, novel Rickettsiaceae endosymbiont in 23.5% (16/68) of M. striifrons and 0% (0/5) of M. sexnotatus insects, Diplorickettsia in 0% (0/68) of M. striifrons and 20.0% (1/5) of M. sexnotatus insects, and Burkholderia in 11.8% (8/68) of M. striifrons and 0% (0/5) of M. sexnotatus insects. The imperfect infection frequencies strongly suggest that these endosymbionts are not essential but facultative associates for the host insects.

Table 2.

Diagnostic PCR detection of bacterial endosymbionts from the Macrosteles leafhoppers

| Species | Locality | Sample | No. of infected insects/total no. of insects examined (% detection rate) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” | “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola” | Wolbachia | Rickettsia | Novel Rickettsiaceae bacteriuma | Diplorickettsia | Burkholderia | Phytoplasma | |||

| Macrosteles striifrons | Mito, Ibaraki, Japanb | Adult female | 15/15 (100) | 15/15 (100) | 0/15 (0.0) | 15/15 (100) | 11/15 (73.3) | 0/15 (0.0) | 0/15 (0.0) | 0/15 (0.0) |

| Adult male | 6/6 (100) | 6/6 (100) | 0/6 (0.0) | 6/6 (100) | 5/6 (83.3) | 0/6 (0.0) | 0/6 (0.0) | 0/6 (0.0) | ||

| Gifu, Gifu, Japanc | Adult female | 14/14 (100) | 14/14 (100) | 3/14 (21.4) | 0/14 (0.0) | 0/14 (0.0) | 0/14 (0.0) | 3/14 (21.4) | 0/14 (0.0) | |

| Adult male | 4/4 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | ||

| Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japanc | Adult female | 17/17 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 0/17 (0.0) | 0/17 (0.0) | 0/17 (0.0) | 0/17 (0.0) | 5/17 (29.4) | 5/17 (29.4) | |

| Adult male | 8/8 (100) | 8/8 (100) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 5/8 (62.5) | ||

| Osaka, Osaka, Japanc | Adult female | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | |

| Adult male | 3/3 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 1/3 (33.3) | 0/3 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | ||

| Total | 68/68 (100) | 68/68 (100) | 5/68 (7.4) | 21/68 (30.9) | 16/68 (23.5) | 0/68 (0.0) | 8/68 (11.8) | 11/68 (16.2) | ||

| Macrosteles sexnotatus | Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japanc | Adult female | 4/4 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 3/4 (75.0) |

| Adult male | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

| Total | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/5 (0.0) | 0/5 (0.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/5 (0) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Grand total | 73/73 (100) | 73/73 (100) | 6/73 (8.2) | 21/73 (28.8) | 16/73 (21.9) | 1/73 (1.4) | 8/73 (11.0) | 14/73 (19.2) | ||

Novel Rickettsiaceae endosymbiont.

Laboratory-maintained insect strain.

Field-collected insect samples.

Phytoplasma.

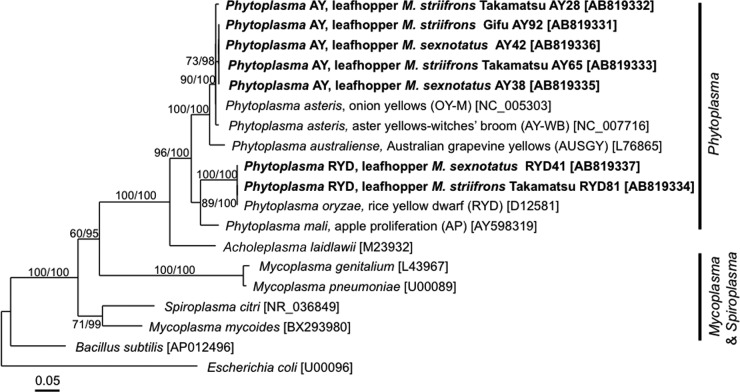

In the PCR, cloning, and sequencing analyses of bacterial 16S rRNA genes described above, no Phytoplasma sequence was obtained from the samples of M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus (Table 1). However, nested PCR detection revealed that 16.2% (11/68) of M. striifrons and 60.0% (3/5) of M. sexnotatus insects are actually associated with Phytoplasma (Table 2). These results probably indicate that the infection titers of Phytoplasma are relatively lower than the infection titers of the obligate and facultative endosymbionts in the Macrosteles leafhoppers. Alternatively, the PCR primers may not match with 16S rRNA gene sequences of Phytoplasma. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the PCR products identified two genetically distinct Phytoplasma strains: a strain (here designated Phytoplasma AY) that belongs to the clade of “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris,” known to be associated with aster yellows and related plant diseases (71), and another strain (here designated Phytoplasma RYD) that clusters with “Candidatus Phytoplasma oryzae,” known to be associated with rice yellow dwarf disease (72) (Fig. 4). Infection frequencies of Phytoplasma AY were 14.7% (10/68) in M. striifrons and 40.0% (2/5) in M. sexnotatus, whereas infection frequencies of Phytoplasma RYD were 1.5% (1/68) in M. striifrons and 20.0% (1/5) in M. sexnotatus (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). These results confirm that the Macrosteles leafhoppers are associated with several Phytoplasma strains at considerable frequencies and vectoring these plant pathogens (38, 39). Thus far, Nephotettix cincticeps has been the only reported vector of Phytoplasma RYD (32). Our results suggest the possibility that the Macrosteles leafhoppers may also vector the phytopathogenic phytoplasmas.

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic placement of 16S rRNA gene sequences of phytoplasmas obtained from the Macrosteles leafhoppers. A maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogeny inferred from 1,115 aligned nucleotide sites is shown, while Bayesian (BA) analysis gave substantially the same result. Bootstrap probabilities for the ML analysis and posterior probabilities for the BA analysis at 50% or higher are shown at the nodes. Asterisks indicate support values lower than 50%. The sequences obtained from the leafhoppers in this study are highlighted by boldface type, wherein bacterial taxon, leafhopper species and origin, and nucleotide sequence accession number in brackets are indicated. Scale bar shows branch length in terms of number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Clades of Phytoplasma, Mycoplasma, and Spiroplasma are indicated on the right side.

Coinfection patterns of obligate endosymbionts, facultative endosymbionts, and Phytoplasma in M. striifrons and M. sexnotatus.

Table S3 in the supplemental material summarizes the coinfection patterns of the endosymbiotic bacteria in the Macrosteles leafhoppers. Of 64 insects of M. striifrons, 24 were double infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola”; 27 were triple infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinocola,” and another bacterium (5 with Rickettsia, 5 with Wolbachia, 7 with Burkholderia, 9 with Phytoplasma AY, and 1 with Phytoplasma RYD); and 17 were quadruple infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” and two additional bacteria (17 with Rickettsia and novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium and 1 with Burkholderia and Phytoplasma AY). Of 5 insects of M. sexnotatus, 1 was double infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalincola”; 3 were triple infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” and Phytoplasma (2 with Phytoplasma AY and 1 with Phytoplasma RYD); and 1 was quadruple infected with “Ca. Sulcia muelleri,” “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola,” Wolbachia, and Diplorickettsia.

Conclusion and perspective.

Here, we demonstrate that at least seven endosymbiotic bacteria, of which two (“Ca. Sulcia muelleri” and “Ca. Nasuia deltocephalinicola”) are obligate and five (Rickettsia, Wolbachia, Burkholderia, Diplorickettsia, and novel Rickettsiaceae bacterium) are facultative, are coexisting in natural populations of the Macrosteles leafhoppers that are known to vector phytopathogenic phytoplasmas. Actually, two genetically distinct phytoplasmas, “Ca. Phytoplasma asteris” and “Ca. Phytoplasma oryzae,” are detected in the populations of the Macrosteles leafhoppers, further expanding the endosymbiont repertoire. The endosymbiont diversity may be striking at a glance, but it should be noted that, considering the limited number of samples examined in this study, more endosymbionts are likely to be identified through wider surveys. On the basis of current data, it is still premature to draw any general conclusion on the superinfection patterns of the endosymbionts. Apparently, however, the obligate endosymbionts, the facultative endosymbionts, and the phytopathogenic phytoplasmas have ample opportunities to interact with each other within the same host insects. Future studies should be directed to survey of more samples, populations, and species of these and allied Macrosteles leafhoppers for their endosymbiotic microbiota and experimental investigation of interactions between the coexisting endosymbionts. In particular, it is of practical interest whether the facultative endosymbionts affect the ability of the host insects to vector the phytopathogenic phytoplasmas.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Norio Nishimura and Satoshi Nakajima (Koibuchi College of Agriculture and Nutrition, Japan) for providing the M. striifrons strain originating from Mito, Ibaraki, Japan.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 238066. Y.I. and Y.M. were supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Fellowship for Young Scientists.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 June 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01527-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maramorosch K, Harris KF. 1979. Leafhopper vectors and plant disease agents. Academic Press, Inc, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nault LR, Rodriguez JG. 1985. The leafhoppers and planthoppers. Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumann P. 2005. Biology of bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:155–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Douglas AE. 2009. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct. Ecol. 23:38–47 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A. 2008. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42:165–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchner P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7. Müller HJ. 1962. Neuere Vorstellungen über Verbreitung und Phylogenie der Endosymbiosen der Zikaden. Z. Morphol. Ökol. Tiere 51:190–210 [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA. 2009. Convergent evolution of metabolic roles in bacterial co-symbionts of insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:15394–15399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moran NA, Tran P, Gerardo NM. 2005. Symbiosis and insect diversification: an ancient symbiont of sap-feeding insects from the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8802–8810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moran NA, Dale C, Dunbar H, Smith WA, Ochman H. 2003. Intracellular symbionts of sharpshooters (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadellinae) form a distinct clade with a small genome. Environ. Microbiol. 5:116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takiya DM, Tran PL, Dietrich CH, Moran NA. 2006. Co-cladogenesis spanning three phyla: leafhoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and their dual bacterial symbionts. Mol. Ecol. 15:4175–4191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu D, Daugherty SC, Van Aken SE, Pai GH, Watkins KL, Khouri H, Tallon LJ, Zaborsky JM, Dunbar HE, Tran PL, Moran NA, Eisen JA. 2006. Metabolic complementarity and genomics of the dual bacterial symbiosis of sharpshooters. PLoS Biol. 4:e188. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Noda H, Watanabe K, Kawai S, Yukuhiro F, Miyoshi T, Tomizawa M, Koizumi Y, Nikoh N, Fukatsu T. 2012. Bacteriome-associated endosymbionts of the green rice leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 47:217–225 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wangkeeree J, Miller TA, Hanboonsong Y. 2012. Candidates for symbiotic control of sugarcane white leaf disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:6804–6811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitsuhashi W, Saiki T, Wei W, Kawakita H, Sato M. 2002. Two novel strains of Wolbachia coexisting in both species of mulberry leafhoppers. Insect Mol. Biol. 11:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Negri I, Pellecchia M, Mazzoglio PJ, Patetta A, Alma A. 2006. Feminizing Wolbachia in Zyginidia pullula (Insecta, Hemiptera), a leafhopper with an XX/XO sex-determination system. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273:2409–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang KJ, Han X, Hong XY. 29 August 2012. Various infection status and molecular evidence for horizontal transmission and recombination of Wolbachia and Cardinium among rice planthoppers and related species. Insect Sci. 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis MJ, Ying Z, Brunner BR, Pantoja A, Ferwerda FH. 1998. Rickettsial relative associated with papaya bunchy top disease. Curr. Microbiol. 36:80–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bové JM, Renaudin J, Saillard C, Foissac X, Garnier M. 2003. Spiroplasma citri, a plant pathogenic Mollicute: relationships with its two hosts, the plant and the leafhopper vector. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41:483–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duron O, Bouchon D, Boutin S, Bellamy L, Zhou L, Engelstädter J, Hurst GD. 2008. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biol. 6:27. 10.1186/1741-7007-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marzorati M, Alma A, Sacchi L, Pajoro M, Palermo S, Brusetti L, Raddadi N, Balloi A, Tedeschi R, Clementi E, Corona S, Quaglino F, Bianco PA, Beninati T, Bandi C, Daffonchio D. 2006. A novel Bacteroidetes symbiont is localized in Scaphoideus titanus, the insect vector of flavescence dorée in Vitis vinifera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1467–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sacchi L, Genchi M, Clementi E, Bigliardi E, Avanzati AM, Pajoroc M, Negri I, Marzorati M, Gonella E, Alma A, Daffonchio D, Bandi C. 2008. Multiple symbiosis in the leafhopper Scaphoideus titanus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae): details of transovarial transmission of Cardinium sp. and yeast-like endosymbionts. Tissue Cell 40:231–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Degnan PH, Bittleston LS, Hansen AK, Sabree ZL, Moran NA, Almeida RPP. 2011. Origin and examination of a leafhopper facultative endosymbiont. Curr. Microbiol. 62:1565–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gonella E, Crotti E, Rizzi A, Mandrioli M, Favia G, Daffonchio D, Alma A. 2012. Horizontal transmission of the symbiotic bacterium Asaia sp. in the leafhopper Scaphoideus titanus Ball (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). BMC Microbiol. 12:S4. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-S1-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. 2008. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322:702. 10.1126/science.1162418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaenike J, Unckless R, Cockburn SN, Boelio LM, Perlman SJ. 2010. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science 329:212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2003. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1803–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scarborough CL, Ferrari J, Godfray HC. 2005. Aphid protected from pathogen by endosymbiont. Science 310:1781. 10.1126/science.1120180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. 2008. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 6:e2. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vorburger C, Gehrer L, Rodriguez P. 2010. A strain of the bacterial symbiont Regiella insecticola protects aphids against parasitoids. Biol. Lett. 6:109–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie J, Vilchez I, Mateos M. 2010. Spiroplasma bacteria enhance survival of Drosophila hydei attacked by the parasitic wasp Leptopilina heterotoma. PLoS One 5:e12149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. 2009. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science 326:134–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL. 2009. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with Dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139:1268–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, Greenfield M, Durkan M, Leong YS, Dong Y, Cook H, Axford J, Callahan AG, Kenny N, Omodei C, McGraw EA, Ryan PA, Ritchie SA, Turelli M, O'Neill SL. 2011. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476:454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, McMeniman CJ, Leong YS, Dong Y, Axford J, Kriesner P, Lloyd AL, Ritchie SA, O'Neill SL, Hoffmann AA. 2011. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476:450–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weiss B, Aksoy S. 2011. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 27:514–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nault LR, Ammer ED. 1989. Leafhopper and planthopper transmission of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 34:503–529 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weintraub PG, Beanland L. 2006. Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51:91–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weintraub PG, Wilson MR. 2010. Control of phytoplasma diseases and vectors, p 233–249 In Weintraub PG, Jones P. (ed), Phytoplasmas: genomes, plant hosts and vectors. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fukatsu T. 1999. Acetone preservation: a practical technique for molecular analysis. Mol. Ecol. 8:1935–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fukatsu T, Nikoh N. 1998. Two intracellular symbiotic bacteria from the mulberry psyllid Anomoneura mori (Insecta, Homoptera). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3599–3606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. 2005. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Posada D. 2008. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25:1253–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koga R, Tsuchida T, Fukatsu T. 2009. Quenching autofluorescence of insect tissues for in situ detection of endosymbionts. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 44:281–291 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. 2008. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. 2008. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 281:215–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zug R, Hammerstein P. 2012. Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS One 7:e38544. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Noda H. 1984. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in allopatric field populations of the small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus, in Japan. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 35:263–267 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Noda H, Koizumi Y, Zhang Q, Deng K. 2001. Infection density of Wolbachia and incompatibility level in two planthopper species, Laodelphax striatellus and Sogatella furcifera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31:727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Raoult D, Roux V. 1997. Rickettsioses as paradigms of new or emerging infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:694–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perlman SJ, Hunter MS, Zchori-Fein E. 2006. The emerging diversity of Rickettsia. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273:2097–2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weinert LA, Werren JH, Aebi A, Stone GN, Jiggins FM. 2009. Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria. BMC Biol. 7:6. 10.1186/1741-7007-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Parola P, Raoult D. 2001. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:897–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mediannikov O, Sekeyova Z, Birg ML, Raoult D. 2010. A novel obligate intracellular gamma-proteobacterium associated with ixodid ticks, Diplorickettsia massiliensis, gen. nov., sp. nov. PLoS One 5:e11478. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Subramanian G, Mediannikov O, Angelakis E, Socolovschi C, Kaplanski G, Martzolff L, Raoult D. 2012. Diplorickettsia massiliensis as a human pathogen. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Woods DE, Sokol PA. 2006. The genus Burkholderia, p 848–860 In Dworkin M, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes: an evolving electronic resource for the microbiological community, vol 5, 3rd ed, release 3.4 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 59. Estrada-De Los Santos P, Bustillos-Cristales R, Caballero-Mellado J. 2001. Burkholderia, a genus rich in plant-associated nitrogen fixers with wide environmental and geographic distribution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2790–2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moulin L, Munive A, Dreyfus D, Boivin-Masson C. 2001. Nodulation of legumes by members of the β-subclass of Proteobacteria. Nature 411:948–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Van Oevelen S, Wachter RD, Vandamme P, Robbrecht E, Prinsen E. 2002. Identification of the bacterial endosymbionts in leaf galls of Psychotria (Rubiaceae, angiosperms) and proposal of ‘Candidatus Burkholderia kirkii’ sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:2023–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bevivino A, Sarrocco S, Dalmastri C, Tabacchioni S, Cantale C, Chiarini L. 1998. Characterization of a free-living maize-rhizosphere population of Burkholderia cepacia: effect of seed treatment on disease suppression and growth promotion of maize. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 27:225–237 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vessey JK. 2003. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant Soil 255:571–586 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kikuchi Y, Meng XY, Fukatsu T. 2005. Gut symbiotic bacteria of the genus Burkholderia in the broad-headed bugs Riptortus clavatus and Leptocorisa chinensis (Heteroptera: Alydidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4035–4043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. 2007. Insect-microbe mutualism without vertical transmission: a stinkbug acquires a beneficial gut symbiont from the environment every generation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4308–4316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. 2011. An ancient but promiscuous host-symbiont association between Burkholderia gut symbionts and their heteropteran hosts. ISME J. 5:446–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. 2011. Specific developmental window for establishment of an insect-microbe gut symbiosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:4075–4081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dillon RJ, Dillon VM. 2004. The gut bacteria of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49:71–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kodama K, Kimira N, Komagata K. 1985. Two new species of Pseudomonas: P. oryzihabitans isolated from rice paddy and clinical specimens and P. luteola isolated from clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 35:467–474 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Perry AL, Lambert PA. 2006. Propionibacterium acnes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 42:185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee IM, Gundersen-Rindal DE, Davis RE, Bottner KD, Marcone C, Seemüller E. 2004. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’, a novel phytoplasma taxon associated with aster yellows and related diseases. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1037–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jung HY, Sawayanagi T, Wongkaew P, Kakizawa S, Nishigawa H, Wei W, Oshima K, Miyata S, Ugaki M, Hibi T, Namba S. 2003. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma oryzae’, a novel phytoplasma taxon associated with rice yellow dwarf disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1925–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.