Abstract

Objective To examine the risk of colorectal cancer after orlistat initiation in the UK population.

Design Retrospective matched cohort study.

Setting Data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink from September 1998 to December 2008.

Participants 33 625 adults aged 18 years or over who started treatment with orlistat; each orlistat initiator was matched to up to five non-initiators (n=160 347) on age, sex, body mass index, and calendar time.

Main outcome measures Associations between orlistat initiation and the risk of colorectal cancer, assessed by calculating hazard ratios with propensity score adjusted Cox proportional hazard models.

Results Of 193 972 patients with a median age of 47 (interquartile range 37-57) years, 77% were women and approximately 90% were obese (body mass index ≥30). Orlistat initiators were more likely to have a previous history of diabetes or hypertension and to receive prescriptions for anti-diabetes drugs, statins, and aspirin compared with non-initiators. In the intention to treat analysis, 57 colorectal cancer events were identified among orlistat initiators and 246 among non-initiators, with median follow-up times of 2.96 and 2.86 years, respectively. The calculated incidence rate of colorectal cancer per 100 000 person years was 53 (95% confidence interval 41 to 69) for orlistat initiators and 50 (44 to 57) for non-initiators. Orlistat initiation was not associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer (adjusted hazard ratio 1.11, 95% confidence interval 0.84 to 1.47). Findings were robust in the as treated analyses and in patients who were aged 50 years or over, were morbidly obese, or had a history of diabetes.

Conclusions This study found no evidence of an increased risk of colorectal cancer after the initiation of orlistat. It is limited by the relatively short follow-up time, and the possibility of adverse effects of long term orlistat use on risk of colorectal cancer cannot be excluded.

Introduction

Orlistat is an anti-obesity drug that reduces the absorption of dietary fat by inhibiting lipase and is currently approved for both prescription (Xenical, Roche) and over the counter (Alli, GlaxoSmithKline) sale in the United States and Europe. Long term treatment with orlistat has been shown to significantly reduce weight and waist circumference and to have beneficial effects on blood pressure, lipids, and type 2 diabetes.1 2 3 4 5

An animal study found that orlistat was associated with a significant increase in the number of colonic aberrant crypt foci, independent of high fat diet.6 This result is supported by another preclinical study, which showed that orlistat induced colonic cell proliferation and severe crypt alternation.7 Aberrant crypt foci are putative precursors of colon cancer, although controversy has arisen about aberrant crypt foci as a biomarker of colorectal cancer.8 9 10 An analysis of pooled clinical trials conducted by orlistat manufactures found no statistically significant difference in risk of colorectal cancer between orlistat and placebo groups.11 Nevertheless, the pooled analysis showed a numerical imbalance in colorectal carcinoma favoring placebo and was not adequately powered to detect a clinically relevant increased risk. Six of 9717 patients taking orlistat developed colon cancer compared with only one of 7912 patients on placebo. Furthermore, randomized trials tend to recruit younger and healthier patients. On the basis of a review of available data and literature, the US Food and Drug Administration concluded that no evidence existed of a causal relation between use of orlistat and the risk of colorectal cancer.12

Orlistat is currently the top selling drug in the global market of anti-obesity drugs, with worldwide sales of $663m (£427m; €496m) in 2011, according to a report from EvaluatePharma.13 Given such extensive use of orlistat, the lack of data from population based studies on its effects on the risk of colorectal cancer is a major concern. In this study, we sought to investigate whether orlistat initiation would affect the risk of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of adults in the United Kingdom.

Methods

We did a retrospective matched cohort study using data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) from September 1998 to December 2008. Orlistat was available only by prescription in the UK during our study period.

We considered patients to be new users of orlistat if they were aged 18 years or over, had been actively recorded in the CPRD for at least 12 months before starting orlistat treatment without use of any prescription for anti-obesity drugs (orlistat, sibutramine, rimonabant, phentermine, and diethylpropion), and had a body mass index recorded within 12 months before starting treatment. We further restricted new users of orlistat to those who had a second orlistat prescription on or before the end of drug supply of the first orlistat prescription plus a 15 day grace period. We used the date of the second prescription to define cohort entry (the start date). For each orlistat initiator, we randomly selected up to five non-initiators from patients who had body mass index recorded and did not start any prescription anti-obesity drug on the start date of the corresponding orlistat initiator or in the previous 12 months, further matched on age, sex, and body mass index (within 1 unit). We assigned each non-initiator the same start date of his/her matched orlistat initiator. We excluded patients in both cohorts if they had diagnosis of colorectal adenoma, familial polyposis, or any type of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) before the start date.

Incident colorectal cancer was the outcome in this study. We ascertained diagnosis of colorectal cancer through Read codes during follow-up, including malignant neoplasm and carcinoma in the colon and rectum.

We did both intention to treat and as treated analyses. In the intention to treat analysis (first treatment carried forward), we considered patients to be exposed to the initial treatment (orlistat versus none) until administrative censoring, ignoring any subsequent changes in treatment. In the as treated analysis, we considered orlistat initiators to be exposed until 180 days after the discontinuation of orlistat or an additional prescription for any other anti-obesity drug; we censored non-initiators for initiation of any anti-obesity drug. We chose 180 days to allow for a carry-over effect or latency period of cancer detection. In both analyses, the follow-up started at 180 days after the start date to account for an induction period of cancer pathogenesis in both cohorts and ended with the earliest of death, any type of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), migration out of the healthcare system, or end of the study period.

Statistical analysis

We used a Cox proportional hazards model with robust variance to estimate the hazard ratios of colorectal cancer, overall and over time, and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. To control confounding, we first assembled cohorts by matching and then controlled for remaining imbalances by using propensity scores weighting.14 15 We used this two step approach because we intended to control tightly for age, sex, and body mass index, which are the most important confounders in this study, without the need to rely on correct specification of multivariable models.

We did sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our assumptions of induction and latency periods. We repeated the main analysis with various lengths of time for induction and latency periods. Note that intention to treat analysis is an extreme form of (infinite) latency. We also did subgroup analyses. We used SAS software (version 9.2) for all statistical analyses.

Results

This study included 33 625 orlistat initiators and 160 347 matched non-initiators. Of all non-initiators, 20 664 started anti-obesity drugs during follow-up. Table 1 compares the characteristics of orlistat initiators and non-initiators. Compared with non-initiators, orlistat initiators had a slightly higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension at baseline and were more likely to receive drugs, including oral anti-diabetes drugs, statins, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. After propensity scores weighting, baseline characteristics were well balanced between orlistat initiators and non-initiators.

Table 1.

Matched cohort characteristics at baseline, before and after propensity score weighting

| Variable | No (%) | Weighted non-initiators* (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orlistat initiators (n=33 625) | Matched non-initiators (n=160 347) | ||

| Female sex | 26 030 (77.41) | 124 647 (77.74) | 77.52 |

| Median (IQR) age, years | 47 (37-57) | 47 (37-57) | 47 (36-57) |

| Median (IQR) BMI | 36 (32.4-40.4) | 35.6 (32.1-39.6) | 36.3 (32.7-40.4) |

| BMI category: | |||

| <25 | 174 (0.52) | 1006 (0.63) | 0.45 |

| 25-30 | 3173 (9.44) | 16 909 (10.55) | 8.64 |

| 30-35 | 11 253 (33.47) | 56 460 (35.21) | 32.09 |

| ≥35 | 19 025 (56.58) | 85 972 (53.62) | 58.83 |

| Smoking status: | |||

| Never | 16 932 (50.36) | 88 103 (54.95) | 50.19 |

| Current | 6941 (20.64) | 34 457 (21.49) | 20.67 |

| Past | 8546 (25.42) | 33 402 (20.83) | 25.56 |

| Unknown | 1206 (3.59) | 4385 (2.73) | 3.59 |

| Alcohol use: | |||

| Never | 3488 (10.37) | 13 259 (8.27) | 10.43 |

| Current | 22 719 (67.57) | 113 466 (70.76) | 67.42 |

| Past | 6575 (19.55) | 30 563 (19.06) | 19.60 |

| Unknown | 843 (2.51) | 3059 (1.91) | 2.54 |

| Family history of bowel cancer | 213 (0.63) | 908 (0.57) | 0.65 |

| Colorectal cancer screening | 145 (0.43) | 559 (0.35) | 0.40 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 52 (0.15) | 141 (0.09) | 0.15 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3193 (9.50) | 8733 (5.45) | 9.70 |

| Hypertension | 2251 (6.69) | 8517 (5.31) | 6.84 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 876 (2.61) | 2728 (1.70) | 2.64 |

| Arrhythmias | 255 (0.76) | 925 (0.58) | 0.78 |

| Heart failure | 110 (0.33) | 438 (0.27) | 0.37 |

| Myocardial infarction | 96 (0.29) | 273 (0.17) | 0.26 |

| Gastrointestinal ulcer | 33 (0.10) | 183 (0.11) | 0.14 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 69 (0.21) | 206 (0.13) | 0.21 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 97 (0.29) | 447 (0.28) | 0.30 |

| Insulin treatment | 1508 (4.48) | 3597 (2.24) | 4.63 |

| Oral anti-diabetes drug | 4434 (13.19) | 11 965 (7.46) | 13.46 |

| Hormone therapy | 2495 (7.42) | 8233 (5.13) | 7.55 |

| Statin | 6415 (19.08) | 20 369 (12.70) | 19.39 |

| Aspirin | 4603 (13.69) | 14 596 (9.10) | 13.90 |

| Non-selective NSAID | 10 662 (31.71) | 34 651 (21.61) | 32.05 |

| COX 2 inhibitor | 1429 (4.25) | 3726 (2.32) | 4.41 |

| Vitamin D | 84 (0.25) | 314 (0.20) | 0.24 |

BMI=body mass index; COX 2 inhibitor=cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitor; IQR=interquartile range; NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

*Propensity score model included age (continuous), sex, BMI (continuous), lifestyle factors (smoking (yes, no, unknown), alcohol use (yes, no, unknown)), comorbidity (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, and rheumatoid arthritis), drug use (insulin, oral anti-diabetes drugs, aspirin, NSAIDs, COX 2 inhibitors, statins, and hormone therapies), family history of bowel cancer, and previous screening for colorectal cancer; all variables were defined during 12 month period before cohort entry date and were controlled for by standardizing to their distribution in orlistat initiators by using weights of 1 for orlistat initiators and the odds of the estimated propensity score for non-initiators.15

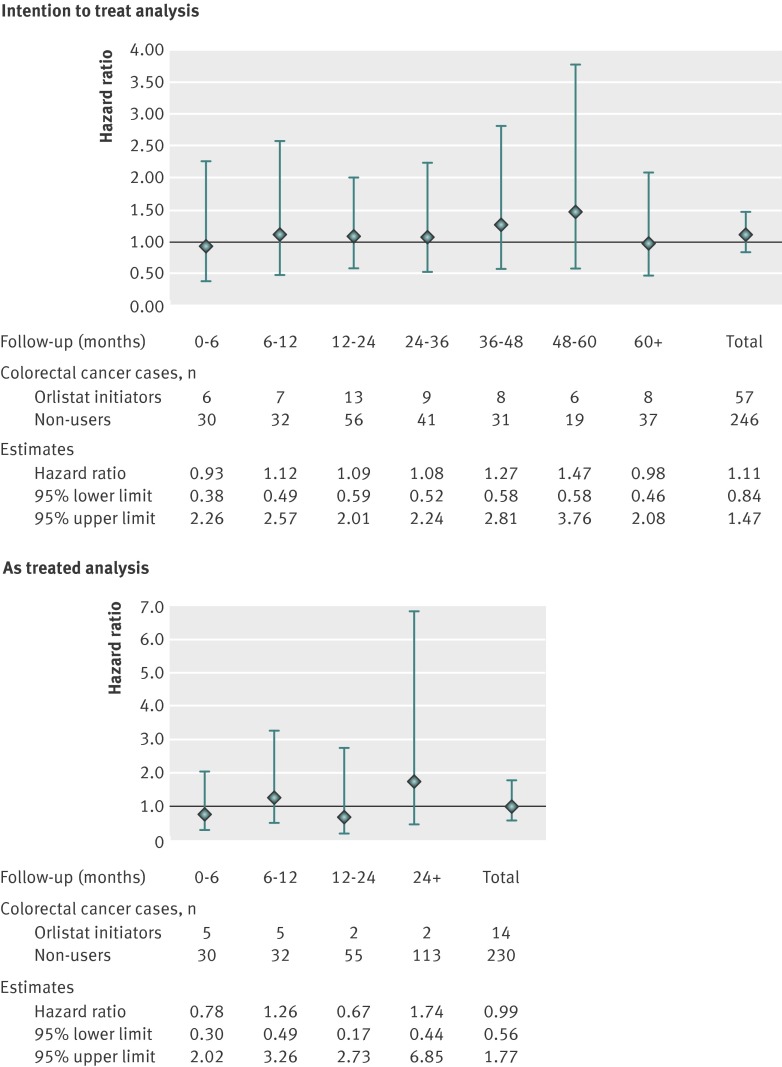

Table 2 shows incidence rates and hazard ratios of colorectal cancer. In the intention to treat analysis, we observed 57 colorectal cancers among orlistat initiators and 246 among non-initiators during 106 708 and 488 526 person years of follow-up. The incidence rate of colorectal cancer per 100 000 person years was 53 (95% confidence interval 41 to 69) for orlistat initiators and 50 (44 to 57) for non-initiators. The hazard ratio of colorectal cancer comparing orlistat initiators with non-initiators was 1.11 (95% confidence interval 0.84 to 1.47) after propensity scores weighting. In the as treated analysis, the mean follow-up time and the number of colorectal cancer cases were lower owing to treatment changes, whereas the hazard ratio estimates were similar to the results of the intention to treat analysis. We further examined the effect of orlistat on the risk of colorectal cancer over the follow-up time (fig 1), and we observed no increased risk of colorectal cancer and no clear trend of the hazard ratios over time.

Table 2.

Incidence rates and hazard ratios for colorectal cancer in orlistat initiators and matched non-initiators

| Cohort | No of colorectal cancers | No of observations | Follow-up (years) | Incidence rates (95% CI) per 100 000 person years | Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | Weighted hazard ratio (95% CI)† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Median (interquartile range) | ||||||

| Intention to treat (ITT) analysisठ| |||||||

| Orlistat initiators | 57 | 31 055 | 106 708 | 2.96 (1.43-5.37) | 53 (41 to 69) | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.40) | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.47) |

| Non-initiators | 246 | 146 133 | 488 526 | 2.86 (1.34-5.24) | 50 (44 to 57) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| As treated (AT) analysis‡ | |||||||

| Orlistat initiators | 14 | 31 055 | 29 971 | 0.75 (0.57-1.16) | 47 (28 to 79) | 0.95 (0.54 to 1.66) | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.77) |

| Non-initiators | 230 | 146 133 | 434 648 | 2.40 (1.08-4.60) | 53 (47 to 60) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

*Because non-initiators were matched on age, sex, and body mass index, unweighted hazard ratios were controlled for these matching variables and standardized to distribution of these variables in orlistat initiators.

†Propensity score weighted hazard ratios were additionally controlled for smoking, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, rheumatoid arthritis, insulin, oral anti-diabetes drugs, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors, statins, hormone therapies, family history of bowel cancer, and previous screening for colorectal cancer, standardized to distribution of these variables in orlistat initiators.

‡Although AT is generally preferred in studies of adverse effects because ITT would tend to mask effects owing to increasing non-adherence to treatment over time, AT could be biased if changes in treatment during follow-up are associated with outcome; ITT ignores subsequent treatment changes and thus avoids potential for selection bias by condition on continuous treatment during follow-up; because of this trade-off in potential biases, both ITT and AT analyses based on different assumptions are presented; use of a time varying exposure classification would be an alternative approach, but it is not compatible with the new user design and thus prone to time varying confounding of treatment changes during follow-up.

§On basis of ITT, 5431 cancer events were observed in whole study cohort (orlistat initiators and non-initiators combined) for overall cancer incidence rate of 791 (95% CI 770 to 812) per 100 000 person years; over study period, 4376 patients died during 657 894 person years of follow-up, resulting in all cause mortality rate of 625 (607 to 644) per 100 000 person years; both rates were higher than in general UK population, likely explained by higher body mass index in study cohort.

Fig 1 Propensity score weighted hazard ratios (95% CI) comparing orlistat initiators and non-initiators, stratified by length of follow-up, in intention to treat (top) and as treated (bottom) analyses

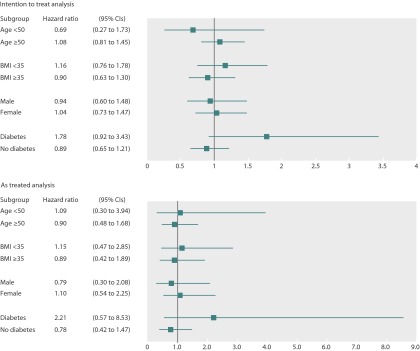

We did sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the results with respect to the assumptions of induction and latency periods (tables 3 and 4). The absence of an effect of orlistat initiation on the risk for colorectal cancer was consistent through the range of induction and latency periods assessed in both intention to treat and as treated analyses. We also did subgroup analyses. The results showed that orlistat was not associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer in analyses stratified according to age (≥50 or <50 years), sex, body mass index (≥35 or <35), or the presence or absence of diabetes at baseline in both intention to treat and as treated analyses (fig 2).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis for induction period in intention to treat analysis

| Induction period and cohort | No of colorectal cancers | No of observations | Follow-up (years)—median (interquartile range) | Weighted hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 days: | ||||

| Orlistat initiators | 58 | 33 625 | 3.20 (1.57-5.64) | 1.00 (0.76 to 1.32) |

| Non-initiators | 272 | 160 347 | 3.03 (1.46-5.47) | 1.00 |

| 90 days: | ||||

| Orlistat initiators | 57 | 32 501 | 3.07 (1.48-5.50) | 1.05 (0.79 to 1.39) |

| Non-initiators | 260 | 153 659 | 2.93 (1.38-5.34) | 1.00 |

| 180 days: | ||||

| Orlistat initiators | 57 | 31 055 | 2.96 (1.43-5.37) | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.47) |

| Non-initiators | 246 | 146 133 | 2.86 (1.34-5.24) | 1.00 |

| 365 days: | ||||

| Orlistat initiators | 51 | 28 463 | 2.72 (1.31-5.14) | 1.14 (0.85 to 1.53) |

| Non-initiators | 215 | 132 631 | 2.63 (1.26-5.04) | 1.00 |

*Propensity score weighted hazard ratios were controlled for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, rheumatoid arthritis, insulin, oral anti-diabetes drugs, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors, statins, hormone therapies, family history of bowel cancer, and previous screening for colorectal cancer, standardized to distribution of these covariates in orlistat initiators.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis for induction and latency period in as treated analysis

| Induction period (days) | Latency period (days) | Cohort | No of colorectal cancers | No of observations | Follow-up (years)—median (interquartile range) | Weighted hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 180 | Orlistat initiators | 15 | 33 625 | 1.21 (1.06-1.60) | 0.77 (0.44 to 1.34) |

| Non-initiators | 256 | 160 347 | 2.61 (1.25-4.75) | 1.00 | ||

| 90 | 180 | Orlistat initiators | 14 | 32 501 | 0.97 (0.82-1.37) | 0.85 (0.47 to 1.52) |

| Non-initiators | 244 | 153 659 | 2.49 (1.16-4.64) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 | 180 | Orlistat initiators | 14 | 31 055 | 0.75 (0.57-1.16) | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.77) |

| Non-initiators | 230 | 146 133 | 2.40 (1.08-4.60) | 1.00 | ||

| 365 |

180 | Orlistat initiators | 9 | 27 234 | 0.32 (0.13-0.73) | 1.12 (0.56 to 2.24) |

| Non-initiators | 199 | 128 276 | 2.32 (1.05-4.48) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 | 0 | Orlistat initiators | 7 | 29 719 | 0.33 (0.14-0.76) | 0.89 (0.40 to 2.01) |

| Non-initiators | 229 | 141 562 | 2.44 (1.12-4.66) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 | 90 | Orlistat initiators | 11 | 30 387 | 0.55 (0.32-0.96) | 0.99 (0.52 to 1.90) |

| Non-initiators | 230 | 143 532 | 2.42 (1.11-4.64) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 | 180 | Orlistat initiators | 14 | 31 055 | 0.75 (0.57-1.16) | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.77) |

| Non-initiators | 230 | 146 133 | 2.40 (1.08-4.60) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 | 365 | Orlistat initiators | 18 | 31 055 | 1.21 (1.08-1.60) | 0.86 (0.52 to 1.41) |

| Non-initiators | 231 | 146 133 | 2.47 (1.17-4.66) | 1.00 | ||

| 180 |

730 | Orlistat initiators | 32 | 31 055 | 2.08 (1.43-2.45) | 1.03 (0.70 to 1.50) |

| Non-initiators | 236 | 146 133 | 2.62 (1.34-4.77) | 1.00 |

*Propensity score weighted hazard ratios were controlled for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, rheumatoid arthritis, insulin, oral anti-diabetes drugs, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors, statins, hormone therapies, family history of bowel cancer, and previous screening for colorectal cancer, standardized to distribution of these covariates in orlistat initiators.

Fig 2 Propensity score weighted hazard ratios (95% CI) comparing orlistat initiators and non-initiators, stratified by age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and history of diabetes at baseline, in intention to treat (top) and as treated (bottom) analyses

Discussion

In our large, non-experimental cohort study, starting orlistat treatment was not associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer among patients aged 18 years or over in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). These findings were consistent in sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses. Orlistat initiators and matched non-initiators had similar baseline characteristics, with only slight difference in previous diagnosis of and treatment for diabetes and hypertension. Our findings provide evidence that use of orlistat does not alter the risk of colorectal cancer.

Although our estimates were based on a small number of events despite the size of the study population, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.11 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.84 to 1.47, showing not only acceptable precision of our estimate but also that our data are not compatible with a meaningful harmful effect of orlistat treatment on the risk of colorectal cancer. Our findings support the US Food and Drug Administration’s conclusion of no increased risk of colorectal cancer associated with the use of orlistat. The FDA’s report was based on the negative results from pooled clinical trials and a small number of cases of colon cancer from the spontaneous adverse event reporting system. Our study, based on a large, population based healthcare database, represents people actually taking orlistat in the real world, who tend to be different from the participants in clinical trials.

Recent studies showed that a reduction in body mass index could decrease the risk of colon cancer,16 17 18 so our results need to be considered in light of the potential protective effect of orlistat induced weight loss in obese people. Unfortunately, we do not have enough follow-up data on body mass index to estimate the magnitude of the effect of orlistat induced weight loss. Given the average orlistat induced weight loss and a short follow-up time in our study, we would not expect a relevant protective effect of orlistat induced weight loss on the incidence of colorectal cancer. Moreover, although this is of scientific interest, we would mainly be interested in the overall effect of orlistat on colorectal cancer incidence from an individual or public health perspective.

In the sensitivity analyses for induction and latency periods, the results were not substantially altered by the length of induction and latency periods, and the absence of association between orlistat and colorectal cancer was consistent throughout all scenarios. Risk of colorectal cancer may change over time after orlistat initiation. We did not observe a monotonic trend of hazard ratios of colorectal cancer over time (fig 1). Although higher risks of colorectal cancer were seen with follow-up of 24 months or longer, the estimates were hampered by wide confidence intervals owing to a small number of colorectal cancer events.

Limitations of study

Our study had several limitations. Non-adherence is of concern. To increase the chances that patients were truly exposed to orlistat, we required at least two continuous prescriptions. We were unable to use an active comparator cohort because the number of patients starting weight reduction drugs other than orlistat was too small. We recognize that the follow-up time is not long enough to observe an effect on initiation of colorectal cancer, so all we can say is that orlistat does not seem to have an effect on promotion of colorectal cancer. Thus, our analysis cannot exclude the possibility of an increased risk of colorectal cancer after long term use of orlistat. Nevertheless, in our data, the short follow-up time based on as treated analysis also indicates that most patients do not take orlistat continuously for a prolonged time.

As this was a non-experimental study, our results may be affected by unmeasured confounding. Fat distribution, usually measured as waist circumference, is a moderate risk factor for colorectal cancer, partially independent of body mass index, and might be positively correlated with the probability of taking orlistat.19 20 Unfortunately, the CPRD fails to capture information on fat distribution. Common side effects of orlistat are gastrointestinal, such as abdominal pain or oily stool, potentially leading to diagnostic endoscopies. This could lead to an earlier diagnosis of (asymptomatic) colorectal cancer, resulting in an increased hazard ratio, but cannot explain our finding; on the other hand, endoscopies also could lead to early removal of colonic adenomatous polyps, resulting in a reduced long term risk of colorectal cancer, but we would expect such a beneficial effect to take several years to become apparent. We also examined the frequency of patients who underwent screening for colorectal cancer within one year after cohort entry and found no difference between orlistat initiator and non-initiators cohorts (0.37% v 0.38%). The generalizability of the results is also limited by the lack of information on race/ethnicity in the CPRD.

Conclusions

Our study provides no evidence of an increased risk of colorectal cancer after starting orlistat treatment in UK adults. The study is limited by the relatively short follow-up time, and we cannot exclude the possibility of adverse effects of long term orlistat use on risk of colorectal cancer.

What is already known on this topic

Orlistat is one of the most widely used anti-obesity drugs and is the only over the counter drug for weight loss approved in the United States and Europe

An animal study showed that orlistat may induce aberrant crypt foci in rodents, but data from population based post-marketing studies on the risk of colorectal cancer are lacking

What this study adds

This study in the UK population showed no evidence of an increased risk of colorectal cancer associated with use of orlistat

The study is limited by the relatively short follow-up time, and the possibility of adverse effects of long term orlistat use on risk of colorectal cancer cannot be excluded

We thank Pascal Egger for help with data management.

Contributors: J-LH, TS, RSS, and CRM conceived and designed the study. TS oversaw the conduct of the study. CRM and SSJ provided the data and oversaw the database programming. J-LH did the data analysis. J-LH and TS interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. TS, RSS, CRM, and SSJ contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript. TS is the guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded by the population research award from the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and R01 AG023178 from the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health. The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study; in the analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: JLH and TS receive(d) salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Epidemiology, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, currently funded by GlaxoSmithKline (a pharmaceutical company that produces Alli, the brand name of orlistat 60 mg); no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for MHRA database research in the UK and was exempt from the Institutional Review Board review at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f5039

References

- 1.O’Meara S, Riemsma R, Shirran L, Mather L, ter Riet G. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of orlistat used for the management of obesity. Obes Rev 2004;5:51-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjostrom L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care 2004;27:155-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutton B, Fergusson D. Changes in body weight and serum lipid profile in obese patients treated with orlistat in addition to a hypocaloric diet: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob S, Rabbia M, Meier MK, Hauptman J. Orlistat 120 mg improves glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic patients with or without concurrent weight loss. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:361-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson K, Sundstrom J, Neovius K, Rossner S, Neovius M. Long-term changes in blood pressure following orlistat and sibutramine treatment: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2010;11:777-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia SB, Barros LT, Turatti A, Martinello F, Modiano P, Ribeiro-Silva A, et al. The anti-obesity agent orlistat is associated to increase in colonic preneoplastic markers in rats treated with a chemical carcinogen. Cancer Lett 2006;240:221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nairooz S, Ibrahim SH, Omar SMM, Affan M. Structural changes of the colonic mucosa induced by orlistat: experimental study. Egypt J Histol 33:635-48.

- 8.Takayama T, Katsuki S, Takahashi Y, Ohi M, Nojiri S, Sakamaki S, et al. Aberrant crypt foci of the colon as precursors of adenoma and cancer. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1277-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta AK, Pretlow TP, Schoen RE. Aberrant crypt foci: what we know and what we need to know. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:526-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mutch MG, Schoen RE, Fleshman JW, Rall CJ, Dry S, Seligson D, et al. A multicenter study of prevalence and risk factors for aberrant crypt foci. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:568-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlistat (Zenical®) preclinical and clinical summary report on colon cancer. 2006. www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/06p0154/06p-0154-c000002-04-Attachment-02-vol3.pdf.

- 12.FDA response to the citizen petition dated April 10,2006 (Petition), and the supplement to the Petition dated June 5, 2006 (Supplement). www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/06p0154/06P-0154-pdn0001.pdf.

- 13.Evaluate. Anti-obesity agents: Top 3 marketed products by therapy area. 2011. www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Entity&entityType=Product&id=35&lType=modData&componentID=1004.

- 14.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41-55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Matsuyama Y. Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization. Epidemiology 2003;14:680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassett JK, Severi G, English DR, Baglietto L, Krishnan K, Hopper JL, et al. Body size, weight change, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2978-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birks S, Peeters A, Backholer K, O’Brien P, Brown W. A systematic review of the impact of weight loss on cancer incidence and mortality. Obes Rev 2012;13:868-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rapp K, Klenk J, Ulmer H, Concin H, Diem G, Oberaigner W, et al. Weight change and cancer risk in a cohort of more than 65,000 adults in Austria. Ann Oncol 2008;19:641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore LL, Bradlee ML, Singer MR, Splansky GL, Proctor MH, Ellison RC, et al. BMI and waist circumference as predictors of lifetime colon cancer risk in Framingham study adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:559-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:2533-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]