Abstract

This paper analyzes how labor market instability since the late 1980s in Europe mediated decisions to second births. In particular, it examines which are the dimensions of economic uncertainty that affect women with different educational backgrounds. First, employing time varying measures of aggregate market conditions for women in twelve European countries as well as micro-measures of each woman’s labor market history, it shows that delays in second births are significant in countries with high unemployment, among women who are unemployed, particularly the least educated, and who have temporary jobs. Holding a very short contract is more critical than unemployment for college graduates. Second, using the 2006 Spanish Fertility Survey, it presents remarkably similar findings for Spain, the country with the most dramatic changes in both fertility and unemployment in the last decades: a high jobless rate and the widespread use of limited-duration contracts were correlated with a substantial postponement of second births.

1 Introduction

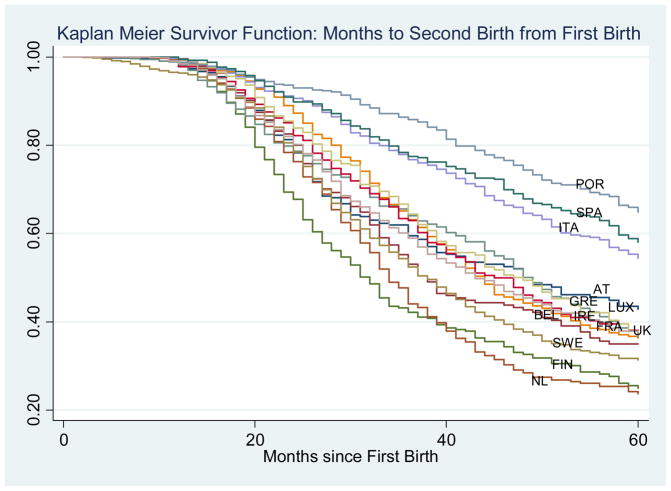

Since the late 1980s, European fertility rates have plummeted, particularly in Southern Europe and German speaking countries, where they dropped to 1.3 or below in recent years (Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002). As shown by an extensive literature, that general trend has resulted from changes in preferences for small families, family planning and the demands of dual-careers (Becker 1981, Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 1988, Galor and Weil 1996, Bongaarts 2002). The cross-country variation in fertility has been attributed to the nature of the welfare state and its social policies (Esping-Andersen 1999, Gauthier 2007, Andersson, Kreyenfeld and Mika 2009) and differences in economic uncertainty (Blossfeld, Klijzing, Mills and Kurz 2005; Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002; Adsera 2005, 2011; Sobotka, Skirbekk and Philipov 2010), among others factors. An additional mechanism leading to the decrease in completed fertility has been delayed motherhood: older mothers are less likely to attain their intended number of children (Morgan 2003). Since the levels of childlessness have not increased much in Europe and there are still substantial fertility differences across countries once differential postponement has been taken into account (Sobotka 2004), a better understanding of the variation in second births is warranted. Figure 1 presents the non-parametric estimates of the survivor function of transitions to second births among women in several European Union countries during the 1990s. Cross-country variation in the timing of the second birth is considerable. Women in Portugal, Spain and Italy are the least likely to have had a second child: five years after their first birth, about 60 percent have not delivered another baby. By contrast, only around 25 percent of Finish and Dutch women have not.

Figure 1.

Non-Parametric Estimates of Transitions to Second birth (ECHP 1994–2000)

Note: Kaplan Meier survivor function of transitions to second births among women in European countries who had a first birth in 1992 or after. Data come from European Community Household Panel 1994–2000.

This paper examines the role that economic conditions played in the decision of women to have more than one child during this time. During the period of analysis, the European labor market was characterized by cycles of high and persistent unemployment and by an upward trend in the share of temporary employment. In addition to looking at how both the lack of work and some insecurity in a job currently held shaped the choices of women in general, the paper also explores the extent to which labor market instability may be related to transitions to second births in a distinct manner for women with different educational backgrounds.

To this end, the paper undertakes two types of analysis. First, it employs the 1994–2000 waves of the European Community Household Panel (ECPH) for women in twelve European countries to estimate proportional hazard models of second births. The estimations include time varying measures of aggregate labor market conditions as well as micro-measures of each woman’s labor market history, employment characteristics and earnings. Second, it employs the 2006 Spanish Fertility Survey to show how those economic conditions—provincial unemployment and share of temporary employment--faced by women either as they enter the labor market in their early twenties or after the birth of their first child are connected to their timing of second births. The analysis of that survey is justified by the fact that Spain was the OECD country that experienced the most dramatic changes in both fertility and unemployment rates in the last decades. The paper shows that both individual and aggregate unemployment as well as temporary employment were positively associated with a delay in second births among all women independently of their educational background. In addition, two other results stand out. First, unemployment slowed down childbearing plans particularly among the least educated whereas its impact was minor among college graduates. Second, short-term contracts (or a labor market with a high proportion of temporary jobs) seemed to have a particular negative effect among the most educated women compared to that of unemployment.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the main changes in economic instability in Europe since the mid 1980s and explores the possible mechanisms through which economic conditions affect women’s decisions to have a second child. Section 3 describes the data and methodology employed in the panel of mothers of twelve European countries during the 1990s and presents results from Cox proportional hazard models of transitions to second births. Section 4 examines the estimations conducted with the 2006 Spanish Fertility survey and includes the simulated proportion of women of different education levels with a second child under various economic scenarios. Section 5 provides a general discussion of the joint effects of educational achievement and economic uncertainty on the transition to second births in Europe.

2. Fertility and the European Labor Market during the 1990s

Fertility behavior is the result of forward-looking and sequential decisions that individuals (or households) make in an uncertain environment under multiple institutional and economic constraints. Economic events not only alter couples’ current demand for children but also their forecasts of future constraints and hence future demands (Butz and Ward 1980, Ermisch 1988).1

The economic environment where household formation and childbearing decisions were made in some European countries during the 1990s was anything but certain. European unemployment went up from under 3 percent before 1975 to about 10 percent in the 1990s. The average female unemployment rate rose from 2.5 percent in 1970 to 6.5 percent in 1980 and then to around 11 percent from the mid 1980s to the late 1990s. Table 1 shows that female unemployment rates in 1998 ranged from 21.1 and 15.4 percent in Spain and Italy to moderate levels around 4 to 6 percent in Luxembourg, United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Table 1.

Female Unemployment Rates, Share of Workers with Contracts of Limited Duration and Their Satisfaction in Europe in the 1990s

| Female Unemployment (a) | Contracts Limited Duration (b) | Relative Satisfaction job security (c) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 5.4 | 7.9 | 84.5 |

| Belgium | 11.6 | 8.2 | 74.6 |

| Denmark | 6.0 | 9.9 | 72.6 |

| Finland | 12.0 | 17.4 | 66.3 |

| France | 12.8 | 13.9 | 61.3 |

| Germany | 9.4 | 12.4 | 82.7 |

| Greece | 16.8 | 12.5 | 57.1 |

| Ireland | 7.3 | 7.2 | 64.9 |

| Italy | 15.4 | 8.6 | 62.1 |

| Luxembourg | 4.0 | 4.9 | 77.9 |

| Netherlands | 5.0 | 13.0 | 73.5 |

| Portugal | 6.2 | 17.2 | 71.5 |

| Spain | 21.1 | 33.0 | 63.6 |

| Sweden | 8.0 | 16.1 | n.a. |

| United Kingdom | 5.3 | 7.3 | 74.3 |

|

| |||

| EU 15 | 10.7 | 13.0 | 70.5 |

Source:

Data are 1998 from EUROSTAT http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/

Ratio of average satisfaction of temporary to permanent workers calculated using ECHP wave 4 data (1996), OECD Employment Outlook (2002)

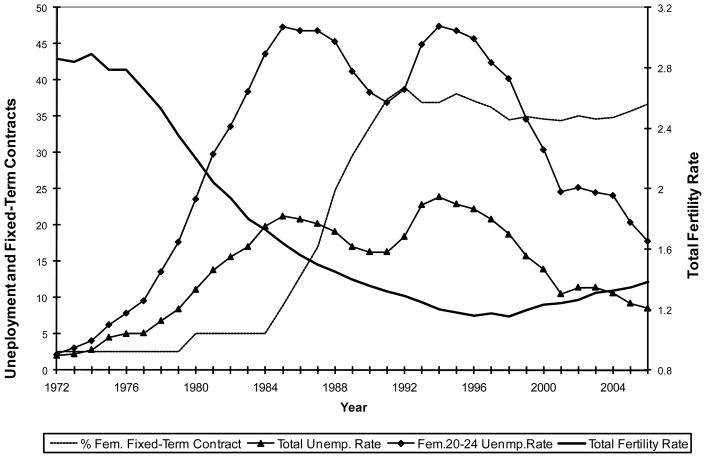

Although the impact of the regulatory environment on the level of unemployment is till debated, there is some evidence that highly regulated markets were hostile environments for young workers (see Addison and Teixeira 2003 for a review). Bertola, Blau and Kahn (2002) note that areas with high employment protection, such as Southern Europe, had lower unemployment rates of prime-aged men compared to young and female workers. Female unemployment rates, for example, climbed beyond 15 percent in Greece and Italy and over 20 percent in Spain by the mid 1990s--about 7 to 12 points higher than their male counterparts (Azmat, Guell, and Manning 2006). To make matters worse, European unemployment during this period was on average very persistent. In 1990, around 50 percent of those unemployed in the European Union had been out of work for more than 12 months. Long-term unemployment delayed household formation (and with it, childbearing) in countries such as Italy or Spain (Aassve, Billari and Ongaro 2001; Gutierrez 2008). Amongst all countries, the level and persistence of unemployment were exceptionally severe in Spain. As shown in Figure 2, the Spanish unemployment rate moved up from around 2–3 percent during the early 1970s to 20 percent by the mid 1980s and stayed at this level throughout the 1990s. The rate of unemployment for young women (20–24 years) almost reached 50 percent in the mid 1980s and again in the 1990s (Figure 2). During the same period, Spain experienced the largest fall in fertility in Europe. The Spanish total fertility rate moved from around 2.8 in 1972 to under 1.3 since the mid 1980s and it was still around 1.2 in the year 2000, only to move up to 1.4 by the end of the decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fertility, Unemployment and Fixed-Term Contracts in Spain, 1972–2006.

In the standard microeconomic model of fertility, the reduction in the opportunity cost of time devoted to children (forgone wages) associated with an unemployment spell is expected to boost fertility (Becker 1981, Galor and Weil 1996). However, if the negative income effect from reduced work earnings is sufficiently large, unemployment may lead to a baby bust. At what point in life unemployment episodes occur and how long they (are expected to) last matters to determine their ultimate impact on fertility. If unemployment is high and persistent, young women (with lower labor market experience on average) may fear that time spent in childbearing (including any eligible maternity leave) may harm their likelihood of re-employment or increase their risk of future unemployment and, as a result, hurt life-time wage-growth, and benefits. Women may choose to postpone maternity to secure their present position or to send a signal of career commitment to their prospective employers. Furthermore, persistent aggregate unemployment may alter the childbearing plans not only of those directly affected by it, but also of those to which it constitutes a threat, as documented, for example, for the interwar period and the 1930s depression (Becker 1981; Murphy 1992). For recent years, Kravdal (2002) finds the effect of unemployment at the municipality level in Norway to be more important than individual unemployment shocks for higher-order birth rates. In Spain, Ahn and Mira (2001) and Gutierrez (2008) show that increases in, respectively, total male and female unemployment rates were associated with large postponement of first births and, in general, family formation.

In addition to high unemployment rates, European labor markets witnessed a strong increase in the share of employees with non-permanent contracts. Permanent contracts (based on high firing costs and generous severance payment schemes born by the employer) were the norm in European countries well into the early 1980s. Temporary work was mainly used for short probation periods (after which the contract became permanent) and for workers under replacement contracts (used to substitute workers on leave for reasons such as sickness and maternity). Firms used fixed-term contracts to adjust to the business or seasonal cycle or for training purposes (Booth, Dolado and Frank 2002). However, precarious short-term contracts proliferated since the mid-eighties after several partial labor reforms eased existing protection regulations in an attempt to reduce unemployment, particularly among the young in Southern Europe (Booth, Dolado and Frank 2002; OECD 2004).

As shown in Table 1, Column 2, in 1998 13 percent of European workers held temporary contracts (as defined by EUROSTAT). Spain, which introduced non-permanent contracts in 1984 encouraging them with temporary subsidies for new hires, had the highest rate: one out of three workers were employed under contracts of limited duration. Among women, that proportion rose from about 5 percent in 1984 to over 35 percent in less than 10 years (Figure 2). Although the proportion of temporary contracts was particularly high in Southern Europe, Finland and Sweden also employed them, mostly for highly cyclical jobs (Holmlund et al. 2002).2

Temporary contracts were especially concentrated among the young and the unskilled workers (OECD 2002). In 2000 one in four 15-to-24 year-old workers countries held a temporary contract (Table 2, Column 1). In some countries the ratio was much higher: one in two for Finland and two in three in Spain. By contrast, among 25-to-54 year-old workers, only 8 percent had temporary contracts in the OECD. Still, the Spanish rate stood at 25 percent and, overall, even though the proportion of 25–54 year old workers that held a non-permanent contract was lower than that of the younger group, they constituted 54.3 percent of all workers with temporary contracts in the OECD. Among different educational attainments, 16 percent of the least educated held temporary contracts. Among the highest educated the proportion was close to 10 percent. In Spain those numbers were 36.6 percent and 26.2 percent respectively. Again, even if the least educated were more likely to be in vulnerable positions, among all temporary workers, one in five had tertiary education. In Spain, Italy, Finland and Sweden the share was one in four or higher.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Temporary Employment across Europe, 2000

| (%) Temporary in total employment for the group | (%)of all Temporary workers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Age | Education | Age | Education | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 15–24 | 25–54 | Low | Medium | High | 25–54 | High | |

| Austria | 28.2 | 3.8 | 21.9 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 38.9 | 10.3 |

| Belgium | 19.7 | 4.5 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 59.2 | 30.2 |

| Denmark | 30.6 | 6.5 | 18.9 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 40.8 | 14.5 |

| Finland | 49.5 | 14.3 | 17.9 | 20.5 | 13.9 | 66.5 | 27.7 |

| France | 34.8 | 6.6 | 16.3 | 15.2 | 13.0 | 54.3 | 22.1 |

| Germany | 38.9 | 6.1 | 29.5 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 41.0 | 16.8 |

| Greece | 28.4 | 12.1 | 17.7 | 12.1 | 9.4 | 67.3 | 18.5 |

| Ireland | 15.1 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 48.9 | 26.7 |

| Italy | 14.7 | 5.4 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 63.1 | 13.6 |

| Luxembourg | 11.3 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 43.3 | 17.4 |

| Netherlands | 24.3 | 6.9 | 17.1 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 50.8 | 20.0 |

| Portugal | 34.4 | 10.9 | 19.4 | 24.0 | 20.6 | 52.1 | 12.3 |

| Spain | 67.4 | 25.2 | 36.6 | 29.5 | 26.2 | 60.4 | 24.2 |

| Sweden | 41.3 | 10.5 | 17.9 | 14.0 | 13.4 | 60.8 | 28.6 |

| United Kingdom | 12.0 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 8.9 | 53.8 | 38.6 |

|

| |||||||

| OECD | 25.0 | 8.0 | 15.7 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 54.3 | 20.5 |

Note: Education levels: low refers to ISCED 0/1/2, medium refers to ISCED 3 and high refers to ISCED 5/6/7.

Source: OECD Employment Outlook (2002)

Workers with contracts of limited duration receive less formal employer-provided training (OECD 2002) and have lower wages than similar workers under permanent contracts (around 16 percent lower for men and 13 percent for women in Britain, and on average 10 percent lower in Spain and 20 percent in France) (Booth, Francesconi and Frank 2002 for Britain; Dolado, García-Serrano and Jimeno 2002 for Spain; Blanchard and Landier 2002 for France). Access to fringe benefits, such as paid vacations, paid sick leave, maternity leave, unemployment insurance and pension schemes, was more precarious among temporary-contract workers. Although conditions vary across countries, most nations impose minimum contributory periods that should certainly harm those holding contracts of limited duration.3 Temporary contracts are generally correlated with higher levels of job turnover and multiple spells of unemployment (Saint-Paul 2000; Blanchard and Landier 2002). Overall, temporary workers in Europe are consistently less satisfied with their job security than those with permanent positions. In the period from 1996 to 2002, the ratio of average satisfaction of temporary to permanent workers averaged 70 percent in OECD countries, ranging from 57 percent in Greece and less than 64 percent in France, Italy and Spain to almost 85 percent in Austria (Table 1, Column 3). The combination of lower earnings, reduced social benefits and more job rotation should have affected long-run fertility choices. Indeed, Adsera (2006) shows that, after taking into account aggregate unemployment as well as demographic and job differences, Spanish women in temporary employment fell short from achieving their desired fertility during the 1990s.4

Even though unemployment and temporary contracts may have affected fertility plans across the board, their impact was probably mediated by the level of education of each woman. First, women of different educational background may search in separate labor markets and for different types of positions. Unemployment rates within European countries were generally lower for the highest educated than for those with less than secondary schooling. Second, women with higher educational background may be able to smooth income shocks due to either holding more savings or to having access to the earnings of a better-employed partner. That allowed them to wait for (and aim at) a better job match or a permanent position. By contrast, less educated women were more budget constrained, in immediate need of work and less confident about obtaining a permanent position in the near future. Third, the degree of selection of women who have already become mothers may be different across skill levels. Highly skilled women who are committed to their careers may postpone maternity until they secure a proper position.5 As a result, the average highly educated working mother in our sample may be in a better bargaining position or more sheltered in a difficult labor market than some of her peers.

3. Second Births across European Countries

3.1 Data and Method

The first part of the paper uses the 1994–2000 waves of the European Community Household Panel Survey (ECHP) across twelve European Union member states (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and United Kingdom). The dataset provides both the year and the month of birth for each individual in the household. With this information, it is possible to reconstruct backwards the childbearing history of women. To minimize excluding children who have already left the household, the sample includes only women who were 40 years old or younger at the time of their first interview.6 Results are robust to restricting the sample to women 38 and younger. Further, in the data less than 0.7 percent of children live with their father and not their mother, so this is not likely to bias the results in any important manner.

I estimate Cox proportional hazard models of the transition to second births. The dependent variable is months to a birth from the first birth. For each woman i in country c and month y who has her first birth at time t=0, the (instantaneous) hazard ratio function at t>0 is assumed to take the proportional hazards form:

| (1) |

where λ0(t) is the baseline hazard function; xicyt is a vector of demographic differences between individuals; mc(y-12) is a vector of 12-month lagged aggregate economic conditions in country c and wic(y-7)t is a vector of 7-month lagged individual labor market status and work income. To account for country unobservables and given that unemployment rates within each country offer sufficient variation over time, I include a vector of country fixed effects, C, to analyze within-country changes in the timing of fertility as a response to changing economic conditions.7 The specification also includes a vector of year dummies, T, to account for world business cycles/shocks and a vector of monthly dummies, M, to account for any seasonality in births. I use a grouped robust variance as estimated by Lin and Wei (1989) and cluster the errors by duration since exposure (that is, from the time elapsed since the individual entered the sample) to take into account the time frame of the sample and avoid underestimating the errors. Results are robust to, alternatively, clustering by country.

All estimates contain basic demographic controls, x′icyt: birthplace age at first birth, sex of first child) as well as time-varying marital status (single, married or cohabiting), and women’s education (and her partner’s if present). The education categories include less than upper secondary, upper secondary and tertiary education.

In addition, I link each woman-monthly observation to the unemployment level and other aggregate conditions prevailing in her country of residence one year ago (mc(y-12)). Country level covariates include female unemployment rates, share of public sector (and its square), index of maternity benefits and log of GDP per capita. Labor market and income per capita series are obtained from OECD Labour Force Statistics, OECD Economic Outlook and national official statistics. I construct a maternity benefits index using the Social Security Programs throughout the World (US Department of Health and Human Services, various years), and Employment Outlook (OECD, various issues). Unemployment rates are monthly whereas the other series are annual.

Finally, models include longitudinal information on labor market status of each woman. The ECHP contains data on the labor market situation of the individual for both the year of the interview and the previous year, unemployment episodes during the five years previous to each interview, the first job the individual ever had as well as the dates when the current job started and the last job ended. Since interviews for the first wave of the panel were conducted in either 1993 or 1994, the earliest year for which there is any complete individual labor market information is 1992. To capture labor market conditions from the moment they become mothers, the sample includes women who had their first child on January 1992 or later. The final sample contains data on 6,920 women with 2,842 observed births by 2001 and its size per country across years is fairly stable. Around six percent of the individuals are lost in each interview but a similar proportion is added from new mothers and the new survey. For those who are lost before a new birth occurs, the observation is censored at the date of the last available interview. The sample appears resilient to potential biases from its panel nature and attrition.8

Since women may change their employment status immediately before or after giving birth, I lag all time varying employment and income covariates by seven months (wic(y-7)t) to reduce any reverse causality problem. Nonetheless, this problem is not as serious for second births as it is for transitions to maternity since most employment reallocations generally occur around the first birth (Browning 1992). Results are robust to using seven to twelve month lags (and estimates are available upon request). I choose the 7-month lag because it affords me a large sample size and it is early enough that I do not expect major changes in employment induced by the pregnancy itself to have taken place already.

In particular, the specification includes covariates of the employment status of the woman (employed, unemployed or inactive) as well as work earnings both from the woman and her partner (if present). Among those employed, the following job characteristics are considered: full or part time (30 hours and less), self-employed and sector of employment (public or private).9 In addition, the ECHP contains information on the length of the woman’s contract if employed. Using this information I construct two separate variables to characterize contracts that are not permanent.

Non Permanent contract (=1) whenever the woman declares her contract not to be permanent regardless of its length.

Very Short Contract (=1) among employed women with no permanent contract it includes both those with casual work or no contract plus those with fixed-term contracts with a duration of less than a year.

3.2 Results

Tables 3 and 4 present the results for the European panel. In addition to the general information on the individual labor market status and type of employment, each table includes one of the measures of contract length just defined above: in Table 3 whether the contract is permanent or not; in Table 4 whether the contract is of very short duration. Models are first estimated jointly for all women in the twelve countries, then separately for each educational group, and finally, in a sample restricted to Southern European countries (Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece), which experienced the largest hikes both in unemployment and in temporary employment across Europe.

Table 3.

Transition to Second Births, Employment Conditions and Non-Permanent Contracts (ECHP 1994–2000).

| (1) All | (2) Low Educated | (3) Mid Educated | (4) High Educated | (5) Southern Europe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||||

| Foreign-born | −0.084 (0.84) | −0.327* (2.09) | −0.099 (0.59) | 0.299 (1.45) | 0.179 (1.11) |

| NonEu-born | 0.049 (0.33) | 0.569* (2.32) | 0.092 (0.36) | −0.341 (1.15) | 0.071 (0.30) |

| Age at First birth | −0.047** (9.22) | −0.049** (5.80) | −0.047** (6.11) | −0.045** (3.76) | −0.033** (4.79) |

| First Boy | −0.034 (1.01) | −0.036 (0.49) | −0.052 (0.77) | −0.016 (0.24) | 0.002 (0.03) |

| Married | 0.527** (7.28) | 0.376** (2.68) | 0.610** (5.11) | 0.624** (4.12) | 0.876** (3.36) |

| In a couple (married or not) | 0.617 (1.56) | 1.648* (2.36) | 0.034 (0.07) | −0.028 (0.05) | −0.290 (0.40) |

| Woman Education (re: Low Secondary or less) | |||||

| Tertiary | 0.258** (4.59) | 0.223+ (1.94) | |||

| Upper Secondary | 0.062 (1.41) | −0.065 (0.95) | |||

| Partner Education (re: Low Secondary or less) | |||||

| Tertiary | 0.210** (4.25) | −0.005 (0.03) | 0.376** (4.17) | 0.092 (1.01) | 0.158 (1.44) |

| Upper Secondary | 0.002 (0.06) | 0.021 (0.23) | 0.065 (1.07) | −0.077 (0.79) | 0.012 (0.17) |

| Individual Level Variables | |||||

| Woman Employment (re: Inactive) | |||||

| Work (t-7) | −0.184** (2.60) | −0.404* (2.49) | 0.137 (1.30) | −0.235+ (1.70) | −0.267* (1.98) |

| Unemployed (t-7) | −0.139* (2.16) | −0.177+ (1.92) | −0.110 (1.23) | −0.039 (0.27) | −0.142 (1.64)+ |

| Public Sector (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.304** (4.83) | 0.387* (2.23) | 0.291** (3.20) | 0.232* (2.24) | 0.253* (2.17) |

| Part-time (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.130* (2.01) | 0.191 (1.17) | −0.109 (1.04) | 0.300* (2.50) | 0.064 (0.41) |

| Self-employed (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.082 (0.78) | 0.357+ (1.68) | −0.318+ (1.72) | 0.173 (1.09) | 0.232 (1.50) |

| No Permanent Contract (if work (t-7)=1) | −0.194* (2.52) | −0.156 (0.96) | −0.224+ (1.87) | −0.153 (1.23) | −0.188 (1.44) |

| Work Income | |||||

| Woman (t-7) | −0.017** (3.40) | −0.029* (2.20) | −0.036** (3.76) | −0.004 (0.83) | −0.012 (1.13) |

| Partner (t-7) | 0.004* (2.02) | 0.006+ (1.89) | 0.005 (1.51) | −0.002 (0.64) | 0.007 (1.58) |

| Country Level Variables | |||||

| Female Unemployment rate (t-12) | −0.042+ (1.82) | −0.113** (3.26) | −0.006 (0.14) | −0.015 (0.32) | −0.047* (1.97) |

| Person-month | 160,451 | 56,370 | 59,255 | 39,116 | 77,811 |

| Subjects | 6,112 | 2,103 | 2,354 | 1,702 | 2,604 |

| Failures | 2,493 | 725 | 931 | 744 | 853 |

Note: Sample includes women in 12 European countries whose first births occurred on January 1992 or after. Coefficients from Cox Proportional Hazard models. All columns include additional country level variables (share of government employment and its square, maternity leave, log income per capita) as well as year, monthly and country dummies. Earnings are adjusted for differences in purchasing power and expressed in thousands of Euros. Exposure to second birth starts at the time of the first birth. Robust z statistics from errors clustered by duration since exposure in parentheses:

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%. All country variables are lagged one year and individual variables are lagged seven-months.

Table 4.

Transition to Second Births, Employment Conditions and Very Short-term Contracts (ECHP 1994–2000).

| (1) All | (2) Low Educated | (3) Mid Educated | (4) High Educated | (5) Southern Europe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Level Variables | |||||

| Woman Employment (re: Inactive) | |||||

| Work (t-7) | −0.180** (2.58) | −0.391* (2.40) | 0.114 (1.11) | −0.217 (1.59) | −0.261* (2.01) |

| Unemployed (t-7) | −0.139* (2.16) | −0.177+ (1.91) | −0.109 (1.22) | −0.041 (0.28) | −0.142 (1.64)+ |

| Public Sector (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.302** (4.84) | 0.380* (2.19) | 0.294** (3.20) | 0.232* (2.27) | 0.254* (2.17) |

| Part-time (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.129* (2.00) | 0.189 (1.16) | −0.108 (1.03) | 0.303* (2.52) | 0.068 (0.44) |

| Self-employed (if work (t-7)=1) | 0.078 (0.75) | 0.357+ (1.68) | −0.320+ (1.73) | 0.192 (1.21) | 0.234 (1.51) |

| Very Short Contract (if work (t-7)=1) | −0.223** (3.00) | −0.204 (1.28) | −0.159 (1.33) | −0.257+ (1.86) | −0.228+ (1.71) |

| Country Level Variables | |||||

| Female Unemployment rate (t-12) | −0.043+ (1.83) | −0.114** (3.27) | −0.006 (0.15) | −0.014 (0.31) | −0.047* (1.98) |

| Person-month | 160,451 | 56,370 | 59,255 | 39,116 | 77,811 |

| Subjects | 6,112 | 2,103 | 2,354 | 1,702 | 2,604 |

| Failures | 2,493 | 725 | 931 | 744 | 853 |

Note: Sample includes women in 12 European countries whose first births occurred on January 1992 or after. Coefficients from Cox Proportional Hazard models. All columns include the same demographic characteristics in Table 3 (presence of a partner, marital status, education and work income of the woman and her partner, place of birth, sex of previous child, age at first birth), country level variables (share of government employment and its square, maternity leave, log income per capita) as well as year, monthly and country dummies. Exposure to second birth starts at the time of the first birth. Robust z statistics from errors clustered by duration since exposure in parentheses:

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%. All country variables are lagged one year and individual variables are lagged seven-months.

In line with the expectation that working women trade off children in favor of less time-demanding alternatives (Becker 1981), all specifications show that active mothers, on average, experience substantially slower transitions to second births than women who remain inactive. Among those who participate in the labor market, there are large differences depending on their sector and hours of employment, even though earnings for each woman (and her partner) are kept constant in all specifications. Women working full time in the private sector have the lowest estimated hazard to a second child (almost 20 percent lower than inactive women on average). The difference is particularly large among the least educated. Working in the public sector, as opposed to the private sector, or working part-time, as opposed to full time, are positively associated with second births. On average the hazard to a second birth among those employed part-time in the public sector is over 25 percent higher than that of stay-at-home mothers. Public employment seems to entail favorable conditions for combining work and children across all educational groups, while for those with tertiary education (who may be less inclined to abandon the labor market) access to part-time matters the most. Additionally, high-skilled women may have achieved larger bargaining power at their current jobs to request part-time positions than those in more menial occupations.

When analyzing these results, it is important to remember that, given that labor supply and fertility are jointly determined, these estimated coefficients cannot be given a direct causal interpretation since they may conceal some unobserved factors. Women who are unemployed and seeking work, for example, are less likely to have a child than economically inactive women in part because they may be less willing or able to trade off work for further offspring. Similarly, highly educated mothers who intend to devote more time to children are more likely to adjust their hours of work by requesting part-time that those more committed to their careers. Still, the paper’s estimates provide information on the types of positions that are associated with faster transitions to second births.

Whether a personal experience of unemployment is associated with more or less fertility depends on either the lower opportunity cost faced by mothers, in terms of wages, with respect to more prosperous times, or the negative income shock connected to unemployment (in particular if it is persistent). The coefficient of a woman’s unemployment is negative and significant at 5 percent in column (1) of Tables 3 and 4. The estimated hazard to a second child of unemployed women is around 13 percent lower than that of inactive women. In columns (2) to (4), the unemployment coefficient is negative. However, it is only significant for the sample of low educated women (Column 2). That group of women is likely to be the frailest of all in an adverse labor market: within that group those who do not drop off and continue to search for work are probably more in need to make “ends meet” than other groups. Among Southern European women the coefficient on unemployment is remarkably similar to that in column (1), though barely significant at 10 percent possibly due to the smaller sample size (column (5) in Tables 3 and 4). The weaker significance may also stem from the fact that, having postponed maternity the most during this period, Southern European women who are already mothers constitute a more selected group in these countries than elsewhere in Europe.

Finally, as discussed in section 2, the length of the current contract among workers is an indicator of how certain they are about their continuous employment--even after the birth of another child. In column (1) of Table 3, second births among European women without permanent jobs (of any contract length) happen significantly later than among those with permanent positions (the coefficient is significant at 5%). The coefficient is negative for women in each educational group, but only marginally significant for middle educated women (high school graduates). In column (5), among Southern Europeans, even if the coefficient is remarkably similar to that in column (1), it fails to reach statistical significance on its own. As noted before, this is likely related to both a small sample and to high selection of women in Southern Europe who were particularly cautious in securing a permanent position before giving birth in an extremely dualized market (Adam 1996; Gutierrez 2008).

Simulations using column (1) estimates indicate that women with non-permanent contracts in the private sector have the slowest transitions to second births among all mothers. Their estimated hazard rate is over 30 percent lower than that of inactive women. Keeping everything else at the mean and allowing the type of employment to vary across individuals, simulations of estimates in column (1) indicate that the proportion of women who have had a second child by the time their first child turns five are 53.5 percent among those working in the private sector and holding a permanent contract, but only 42.5 among those in the private sector with non-permanent contracts.

Moving beyond the distinction between temporary and permanent jobs and to account for of extremely insecure jobs, Table 4 controls for contracts that are either very short (less than one year) or inexistent. The coefficient of very short contracts is negative, larger than that for non-permanent contracts in Table 3, and significant (at 5%) in column (1). In Southern European countries it is significant at 10% (column 5). Across educational groups, it is negative and sizable but only significant amongst the most educated (Columns 2 to 4). As shown in Table 3 the share of highly educated workers in the OECD that hold a temporary contract is close to 10 percent and one in five of all workers with non-permanent contracts are highly skilled. Some positions in Europe that lack formal contracts—or only have verbal contracts—are, in many instances high standing professional jobs (e.g. lawyers, consulting) with very demanding schedules and held by college graduates.

Among aggregate covariates, Tables 3 and 4 only display the coefficients on monthly female unemployment rates for the sake of brevity. Coefficients for the other country-level variables as well as for the country, time and monthly dummies are available from the author. In column (1) the female unemployment rate prevailing in the country a year ago enters negatively in the model, but only at 10 percent significance level.10 This confirms previous findings that second births are still affected by underlying economic uncertainty in the country (Ermisch 1988; Kravdal 2002). When the model is estimated separately by educational group, the coefficient for aggregate female unemployment is also negative, but it is only sizable and highly significant (at 1 percent level) for the least educated (Columns 2 to 4 in Tables 3 and 4). This goes hand in hand with the finding that a personal experience of unemployment deters the least educated the most, among all educational groups, from having a second child. Finally in column (5), for the sample of Southern European countries where local unemployment grew the most during this period, the coefficient is of similar size to that in the complete European sample but more significant (at 5 percent).

4. Second Births in Spain

4.1 Data and Method

The second part of the paper examines whether the relationships between economic conditions and timing of second births unveiled in the European Union data hold with the same strength in Spain, the country with the highest employment shortages during the 1990s. As shown in Table 1, Spain was the country were both unemployment and the share of contracts of limited duration grew the most since the late 1980s. After a long period of stable and low unemployment rates during the 1960s and early 1970s, Spanish unemployment increased sharply from 1978 to 1985 and, after that, it remained high for many years (see Figures 2 and 3). The increase was followed by the partial de-regulation of the labor market in the mid 1980s and a subsequent rise in temporary employment--particularly among women, who were entering the labor market at that time and young cohorts in general. As in other Southern European countries, the ratio of satisfaction with job security of those employed in temporary jobs relative to those in permanent jobs was very low during the 1990s (Table 1). Thus, employees holding a contract of limited duration were likely to perceive their future employment as uncertain.

I use the 2006 Spanish Fertility Survey to study how education and the economic conditions just described interact in explaining the transition to second births. The survey follows the guidelines of the Fertility Surveys from the United Nations. It was conducted during the period of April 17 and May 31st of 2006. One woman was interviewed in each household. The total number of home-interviews conducted was 10,000 and, among those women, close to 5,000 had at least one child and were included in the sample of analysis. The survey contains a rich set of variables on the members of the household and complete fertility and marital histories of the women.

I use a proportional hazard model similar to that employed in Section 3 with the European data. I control for basic demographic background such as age at first birth, sex of the first born, place of birth, size of the municipality of residence, educational attainment, and the woman’s number of siblings as well as a set of 17 regional dummies. All the models are stratified by birth cohort to account for potential changes in preferences across cohorts or other socio-economic conditions idiosyncratic to each generation that may bias our results.11 Errors are clustered by region.

To measure the local economic environment faced by women I use two indicators: (1) Provincial quarterly unemployment rate in the province where a woman resides (out of 50 provinces); (2) Share of temporary employment over total employment in the country.

In addition to both the rate of unemployment and the share of temporary employment, some models include interactions of those two measures with the educational attainment of each woman. With these models I study whether economic conditions are connected to the timing to second births with different intensity across educational groups. The Appendix presents the means and standard deviations of the independent variables for the sample of women in the analysis.

Local economic conditions are measured at two different points in time. The first set of estimates assigns to each woman the economic environment she faced three or four years after she potentially entered the labor market (either working or searching for a job). For those who did not go to college I measure these conditions at age 22 and for those who went on to tertiary education at age 26. I want to analyze whether first labor market experiences, which may have a lasting impact on the speed of household formation, future career prospects and women’s expectations of the type of positions available to them (i.e. permanent versus temporary employment; part-time), are related to second births.

In a second set of estimates I split each woman‘s observation in multiple month-observations from the month of her first birth until either her second birth or the interview date. I introduce time-varying provincial unemployment rates and shares of permanent employment from the moment of the first birth onward to measure the underlying conditions at the time of deciding whether to have a second child or not. As explained below, results with the Spanish data are consistent with those in section 2. The coefficients of the relevant variables have the same sign in both sets of estimates--those with early labor market conditions and those with time-varying conditions since the first birth.

4.2 Results

Table 5 presents the models of transitions to second birth with economic conditions measured early in adult life. The model is estimated first for the whole sample and then for all women born in 1950 or after, who were more likely to participate in the labor market than earlier cohorts and faced the sharpest changes both in labor markets and in social values as they reached their adulthood after the transition to democracy. Overall, the direction and size of all coefficients is remarkably stable across both samples, though the relevance of early labor market conditions increases for the younger sample.

Table 5.

Transitions to Second Birth, Education and Local Economic Conditions Prevalent During Early Labor Market Experience (Spanish Fertility Survey 2006).

| All | Born 1950+ | All | Born 1950+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at first Birth | −0.003** (8.11) | −0.003** (7.37) | −0.003** (7.84) | −0.003** (7.26) |

| First child boy | 0.009 (0.27) | 0.018 (0.42) | 0.005 (0.16) | 0.015 (0.38) |

| Foreign born | −0.080 (1.11) | −0.044 (0.57) | −0.067 (0.92) | −0.040 (0.55) |

| Woman siblings | 0.023** (3.26) | 0.025** (2.69) | 0.023** (3.22) | 0.024* (2.57) |

| Municipality (re: Town) | ||||

| 400,000 or more | −0.206** (5.67) | −0.184** (3.71) | −0.216** (6.50) | −0.192** (4.25) |

| 100,000–400,000 | −0.001 (0.02) | 0.050 (0.77) | −0.009 (0.22) | 0.047 (0.73) |

| 10–100,000 | −0.059 (1.49) | −0.033 (0.55) | −0.063 (1.59) | −0.036 (0.60) |

| Education (re: Low secondary ) | ||||

| Primary or less | 0.042 (1.55) | 0.056+ (1.67) | −0.035 (0.93) | −0.026 (0.37) |

| Highschool/FP | 0.046 (0.86) | 0.012 (0.21) | 0.071 (0.94) | −0.037 (0.34) |

| College | 0.385** (4.30) | 0.446** (4.38) | 0.139 (1.15) | 0.248+ (1.78) |

| Local Labor Market Provincial Quarterly | ||||

| Unemployment Rate: | ||||

| Unemp Rate | −0.853* (1.97) | −1.311** (2.83) | −1.112* (2.04) | −1.524** (3.22) |

| Unemp.Rate × Primary or less | 0.540 (0.72) | 0.246 (0.29) | ||

| Unemp.Rate × Highschool/FP | 0.147 (0.19) | 0.455 (0.56) | ||

| Unemp.rate × College | 1.119 (1.26) | 0.735 (0.93) | ||

| %Temporary Employment | ||||

| Temp.Emp. | −0.828* (1.98) | −1.000* (2.22) | −1.004+ (1.88) | −1.113* (2.07) |

| Temp.Emp × Primary or less | 0.192 (0.22) | 0.415 (0.50) | ||

| Temp.Emp. × Highschool/FP | −0.239 (0.36) | −0.101 (0.15) | ||

| Temp. Emp. × College | 0.624 (1.18) | 0.434 (0.81) | ||

| Subjects | 4,519 | 3,344 | 4,519 | 3,344 |

| Failures | 3,290 | 2,282 | 3,290 | 2,282 |

Note: Coefficients from Cox Proportional Hazard model. Robust z statistics in parentheses:

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%. Errors clustered by 17 regions (Comunidad Autonoma). Dummies for Comunidades Autonomas included in estimates. Stratified by birth cohorts defined as 1. born before 1950; 2. 1950–59; 3. 1960–67; 4. 1968–75; 5. born after 1975. Results are robust to estimating primary education and less than primary education as separate variables and to adding controls for home ownership and religious practice.

Columns (1) and (2) present the basic model. Our two variables of interest show the expected sign and are highly significant (at 5 percent level for the whole sample and at 1 percent level for the sample of those born in 1950 and after). Those women who lived in a province with relatively high unemployment early in their careers took more time to have a second child. Using estimates in column (1) and keeping everything else at the mean for the group, the proportion of women with low secondary education (less than high school) that would have had a second child eight years after their first varies from 70 percent if they faced a 5 percent unemployment rate in their early adulthood to only 65 percent if that rate was 20 percent (in the upper range for the period under analysis). Using estimates in column (2), for cohorts born 1950 and after, those proportions are 73 percent and 66 percent respectively. Similarly, those who experienced a labor market with a high prevalence of temporary employment in their young adulthood tend to postpone second births. The proportion of women with low secondary education who had a second child by the eight birthday of their first born falls from 71 percent if they faced a market where only 5 percent of workers were temporary to 63 percent if that same proportion was 30 percent (as in the most recent years in Spain). Thus, even if the decision of having a second child does not occur at that point in life for many of them, labor market conditions women face in their early to mid-twenties, when they (or their partners) enter the labor market, have a long lasting impact in their childbearing patterns. Having entered the market under adverse economic conditions is likely to be associated with postponement of motherhood and with worse employment trajectories than otherwise.

Columns (3) and (4) present the complete model that includes interactions of economic conditions for each of the educational groups. The aim of these models is to understand whether there is some important interplay between the different aspects of economic uncertainty and educational status, that is, whether women with a given educational background respond more to either unemployment or to the prevalence of contracts of limited duration. In both models the coefficients of provincial unemployment and share of temporary contracts continue to enter negatively and significantly. The estimated coefficients of the interactive variables with both aggregate economic measures increase with the level of education (with the exception of temporary employment for high school graduates) indicating that, on average, the impact of those conditions is somewhat more moderate for the more educated. Even though none of the coefficients of the interactive variables is significant on their own, both interactive variables and the levels of education and economic conditions are, in general, jointly significant. (Tests are available upon request.)

To better grasp these results, Table 6 presents the predicted percentage of women who have had a second child by the time their first child turns eight. Predictions are shown assuming different economic environments during young adult years and for both those with lower secondary school and those with any type of college degree. All the variables are set at the mean except for the age at first birth, which is allowed to vary by educational group. Since in the model economic conditions enter not only linearly but also interacted with education, the gap between educational groups as the underlying economic conditions vary does not remain constant. The top half of the table allows the provincial unemployment rate to vary from 5 percent to 10 percent and then 20 percent and sets the share of temporary employment at 14.5 percent, the mean of the period. Whereas the share of college educated women with a second child does not vary with unemployment, the share among those with lower secondary education falls from 69.6 percent to 63.5 when unemployment rises (Table 6, first row). Unemployment has a strong effect on cohorts born in 1950 and after (Table 6, second row). As unemployment rises from 5 to 20 percent, the share of low educated women with a second child falls from 73.4 percent of the women to only 65.2. Among college graduates, the percentage also falls – but only by four points, from 80.3 to 76.4. The bottom half of Table 6 simulates the impact of a change in the share of temporary employment from levels similar to those prevailing in the earlier years of the analysis of around 5 percent to 15 percent and then to the highest levels observed of 30 percent. Provincial unemployment is set at the mean of 11.5 percent. The decrease in the share of second-time mothers as temporary employment becomes more common is now substantial for both education groups. It falls by 9 points among the least educated and by over 3 points among college graduates. Among those born after 1949, there is a 10-point drop for those with low secondary education and a 6-point drop among those with tertiary education.

Table 6.

Proportion of Second-time mothers by Labor Market Conditions Prevalent in Early Adulthood.

Models: Table 5, columns 3 & 4

| Share of women with a Second Birth 8 years after 1st | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Unemployment Rate (Quarter) | ||||||

| 5% | 10% | 20% | ||||

| Education | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College |

| All | 69.6 | 74.0 | 67.6 | 74.0 | 63.5 | 74.1 |

| Born 1950+ | 73.4 | 80.3 | 70.7 | 79.0 | 65.2 | 76.4 |

| Share Temporary Employment | ||||||

| 5% | 15% | 30% | ||||

| Education | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College |

| All | 70.4 | 75.3 | 66.8 | 74. 0 | 61.3 | 72.0 |

| Born 1950+ | 73.7 | 80.7 | 69.7 | 78.5 | 63.6 | 75.0 |

Note: Age at first birth is set at the mean of each education group, the birth cohort is set for those born 1960–67 and all other variables set at the mean. The share of temporary employment is set at the mean when provincial unemployment is allowed to vary in the first two rows and vice versa for the last two rows. Labor market conditions are measured at age 22 for individuals with high school or less and for age 26 for individuals with tertiary education.

To sum up, results in Tables 5 and 6 show that, first, the negative association of adverse economic conditions and transitions to second births is very large among the least educated, and, second, that, particularly among younger cohorts, an increase in the prevalence of contracts of limited duration is relatively more detrimental to childbearing plans of college graduate mothers than unemployment. Note that the predicted differences shown in Table 6 would be even larger had we allowed both economic conditions to vary jointly as they did during the period. As shown in Figure 2, both the unemployment rate and the proportion of temporary contracts grew at the same time.

Table 7 uses the sample of person-month observations to include time-varying economic conditions from the time of the first birth until the second birth or the interview date. Models in columns (1) to (4) are estimated for the whole sample and those in columns (5) to (8) for all women born in 1950 or after. Results are strikingly similar to those that employ economic conditions in early adulthood. Again, both the provincial unemployment rate and the share of temporary employment enter with a negative sign and are significant in all the models. Except for a couple of cases, the coefficients of the interactions of economic conditions with education are only jointly significant. College graduates are the least affected by bad times, but in relative terms they seem to care more about contractual instability than unemployment. Table 8 presents simulations of results in Table 7, columns (4) and (8) in a similar fashion as done in Table 6. The share of college graduates with a second child drops less than 3 points from 77.2 percent to 74.5 as unemployment moves up from 5 to 20 percent. Among the most recent cohorts, the drop is almost negligible. For the least educated the drop, of around 6 to 7 points, is similar in both samples. Again the story is different when temporary employment instead of unemployment is allowed to vary. The share of women who decide to expand their families fluctuates importantly for both educational categories, and especially for later cohorts. In the last row of Table 8, the share of second births among the most educated moves from 86.1 to 78.3 and among those with only low secondary schooling from 82.1 to 67.4. as the share of fixed-term contracts among the employed increases from 5 to 30 percent.

Table 7.

Transitions to Second Birth, Education and Time Varying Local Economic Conditions since First Birth (Spanish Fertility Survey 2006).

| All | All | All | All | Born 1950 + | Born 1950 + | Born 1950 + | Born 1950 + | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education (re: Low secondary ) | ||||||||

| Primary or less | 0.016 (0.56) | 0.013 (0.28) | 0.018 (0.39) | 0.012 (0.25) | 0.057 (1.39) | 0.121 (1.20) | 0.104 (1.21) | 0.129 (1.20) |

| Highschool/FP | 0.067 (1.61) | 0.188* (2.24) | 0.115+ (1.74) | 0.190* (2.32) | 0.017 (0.31) | 0.031 (0.18) | −0.071 (0.55) | −0.039 (0.21) |

| College | 0.320** (3.95) | 0.138 (1.23) | 0.118 (1.05) | 0.075 (0.60) | 0.379** (4.39) | 0.225 (1.37) | 0.207 (1.20) | 0.110 (0.51) |

| Provincial Quarterly | ||||||||

| Unemployment Rate: | ||||||||

| Unemp Rate | −1.393* (2.50) | −1.388* (2.43) | −1.312* (2.37) | −1.291* (2.53) | −1.284* (2.52) | −1.263* (2.49) | −1.205* (2.36) | −1.196* (2.53) |

| Unemp.Rate × Primary or less | −0.019 (0.05) | 0.175 (0.34) | −0.419 (0.72) | −0.220 (0.32) | ||||

| Unemp.Rate × Highschool/FP | −0.826 (1.32) | −0.836 (1.12) | −0.084 (0.10) | −0.234 (0.27) | ||||

| Unemp.rate × College | 1.403+ (1.78) | 0.625 (0.75) | 0.952 (0.96) | 0.743 (0.76) | ||||

| %Temporary Employment | ||||||||

| Temp.Emp. | −1.147** (2.97) | −1.198** (3.10) | −1.259** (3.07) | −1.263** (3.00) | −1.468** (3.87) | −1.489** (3.91) | −1.541** (3.94) | −1.562** (3.93) |

| Temp.Emp × Primary or less | −0.163 (0.47) | −0.258 (0.59) | −0.357 (0.82) | −0.303 (0.61) | ||||

| Temp.Emp. × Highschool/FP | −0.216 (0.57) | 0.005 (0.01) | 0.371 (0.74) | 0.400 (0.79) | ||||

| Temp. Emp. × College | 1.050* (2.45) | 0.855* (1.96) | 0.702 (1.27) | 0.613 (1.14) | ||||

| Person-month | 418,036 | 418,036 | 418,036 | 418,036 | 203,960 | 203,960 | 203,960 | 203,960 |

| Subjects | 4,943 | 4,943 | 4,943 | 4,943 | 2,999 | 2,999 | 2,999 | 2,999 |

| Failures | 3,553 | 3,553 | 3,553 | 3,553 | 1,965 | 1,965 | 1,965 | 1,965 |

Note: Coefficients from Cox Proportional Hazard model. All columns include the same demographic characteristics in Table 5. Robust z statistics in parentheses:

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%. Errors clustered by 17 regions (Comunidad Autonoma). Dummies for Comunidades Autonomas also included in estimates. Stratified by birth cohorts defined as 1. born before 1950; 2. 1950–59; 3. 1960–67; 4. 1968–75; 5. born after 1975. Results are robust to estimating primary education and less than primary education as separate variables.

Table 8.

Proportion of Second-time mothers by Varying Labor Market Conditions since Their First Birth.

Models: Table 7, columns 4 & 8

| Share of women with a Second Birth 8 years after 1st | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Unemployment Rate (Quarter) | ||||||

| 5% | 10% | 20% | ||||

| Education | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College |

| All | 74.5 | 77.2 | 72.2 | 76.3 | 67.6 | 74.5 |

| Born 1950+ | 77.9 | 82.3 | 75.8 | 82.0 | 71.5 | 81.2 |

| Share Temporary Employment | ||||||

| 5% | 15% | 30% | ||||

| Education | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College | Low Sec | College |

| All | 76.6 | 78.2 | 72.4 | 77.0 | 65.8 | 75.2 |

| Born 1950+ | 82.1 | 86.1 | 76.6 | 83.2 | 67.4 | 78.3 |

Note: Age at first birth is set at the mean of each education group, the birth cohort is set for those born 1960–67 and all other variables set at the mean. The share of temporary employment is set at the mean when provincial unemployment is allowed to vary in the first two rows and vice versa for the last two rows.

Among controls included in the models in Tables 5 and 7, estimates indicate that those who become mothers late or those who live in large cities are less likely to have a second child. Even though Spanish women delayed motherhood during this period, many still had at least one child around age 40 (Gonzalez and Jurado 2006). But, as expected, late motherhood was associated with lower completed fertility (Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002; Morgan 2003). Across education groups, those with college degrees, who postponed motherhood the longest, squeezed the first two births in a short period.12 In additional models not shown in the paper, results are robust to the inclusion of religious affiliation and type of housing – though the sample size is somewhat smaller due to missing information.13

5 Discussion: Employment Uncertainty and Education

This paper analyzes how labor market instability due to rising unemployment and high prevalence of contracts of limited duration affects the decision to have a second child among women of different educational groups. To this end, I first use ECHP data on women from twelve European countries to estimate models of the timing to a second birth that include time varying measures of aggregate market conditions in each woman’s country as well as her individual labor market history as covariates. Second, I estimate similar models with women from the Spanish Fertility Survey 2006. Market instability is measured by the levels of provincial unemployment and temporality faced by women either earlier in their careers or since the birth of their first child. Both analyses show that unemployment and employment insecurity embedded in contracts of limited duration are powerfully connected to those decisions. Postponement of a second child is significant in countries with high unemployment and among the unemployed. Women with temporary contracts or living in a context where those contracts are highly prevalent are less likely to give birth to a second child.

Economic uncertainty and educational levels interact in [two] main ways. First, even though unemployment is negatively associated with transitions to second births among all women, those with low levels of education (less than high school or similar) are the most responsive to changes in both aggregate and individual unemployment conditions both in the European and in the Spanish data. Predictions in Tables 6 and 8 show slow transitions to second births among low educated Spaniards who faced an adverse labor market whereas the impact of unemployment for highly educated women is fairly small. In Tables 3 and 4, low educated women across Europe who were unemployed had significantly slower transitions to a second child than those who were inactive or worked for the public sector. These coefficients were not significant on their own for higher educational categories. As already discussed, the estimated coefficients in the models cannot be given a causal interpretation. However, they are very relevant in showing that, among the least educated who decide (and need) to continue to search for a job (thus remaining in the unemployment ranks) instead of dropping out of the market, the likelihood of a second birth is lower than for those who choose to remain inactive. In the 1999 Spanish Fertility Survey, economic constraints appear as one of the top reasons for restricting fertility among women who report a gap between their preferred family size and their actual fertility. The need to work outside of the home and unemployment of either the woman or her partner are also ranked high (Adsera 2006). It is important to remember that these women are already mothers and that the impact of unemployment has been found to be particularly acute for delaying motherhood altogether (Ahn and Mira 2001, Adsera 2005, 2011). Thus the sample of women that we observe in the paper is likely to be somewhat positively selected since these women have already passed the first hurdle of becoming mothers.

A second important finding is that the increase of temporality in employment hampers second births for women across all educational groups and not only for the least educated. The estimated coefficients in Tables 3 and 4 are negative, large and of reasonably similar size in the three skill-specific columns, but only significant amongst the middle educated in Table 3 for any temporary contract and amongst the most educated in Table 4 for very short contracts. Relative to unemployment, a high prevalence of non-permanent positions seems to be most relevant for middle or highly educated women. The predicted percentage of second-time mothers among college educated women, in Tables 6 and 8, varies now substantially along with the prevalence of fixed-term contracts in the country both in their early adulthood and since the birth of their first child. These findings indicate that there is a general agreement on the desirable characteristics of a labor market but that those may be ranked to some degree differently among individuals depending on their pressing need to bring an extra paycheck to the home and on their ability to wait for a good job match (and absorb the search costs). In that regard, the goal of attaining a permanent employment with secure and generous benefits may be less urgent to some with narrow market options than bringing some additional income to the households. More educated women may hold higher expectations and be ready (and able) to wait for the security in the job.

A last interesting point to highlight is that, in Tables 3 and 4, the specific length of the contract is significant among those with at least high secondary education. For the middle educated (high-school graduates) temporality matters in general. For the college graduates, very short term contracts or the lack of them (even in professional jobs) put them in a situation they may consider too precarious to conceive having a second child in the near future. This finding is not completely surprising since as shown in Table 2 the share of highly educated workers in the OECD that hold a temporary contract is not negligible and 20 percent of all workers with non-permanent contracts are highly skilled. Those workers are, however, more likely to get a permanent contract. The OECD (2002) report shows that mobility into permanent jobs is the highest among middle to highly educated 25-to-34-year olds who have been continuously employed during at least the last five years. Thus, postponing childbearing until obtaining a permanent job seems a rational strategy. Conversely, less educated workers in Europe (with the exception of Austria and UK) face more obstacles to converting their jobs into permanent ones and more likely to become unemployed than the rest. This is particularly true in Southern Europe where low educated workers are 17–24 percent less likely to move to a permanent job (OECD 2002).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank seminar participants at “Employment uncertainty and Family dynamics” Berlin, July 2009 and two anonymous referees for their comments and German Rodriguez for statistical assistance.

Appendix. Means of Variables in Spanish Fertility Survey, 2006

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age at first Birth (in months) | 309 | 57 |

| First Child Boy | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Foreign Born | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| N. siblings of woman | 3.11 | 2.31 |

| Municipality (ref. town) | ||

| 400,000 or more | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| 100,000–400,000 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| 10,000–100,000 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| Education (ref. low secondary) | ||

| Primary or less | 0.29 | 0.46 |

| Highschool/FP | 0.19 | 0.39 |

| College | 0.15 | 0.35 |

| Early Labor Market Conditions | ||

| Provincial Quarterly Unemp. Rate | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| % Temporary Employment | 0.15 | 0.13 |

Footnotes

A large set of studies has unveiled significant relationships between the economic environment, fertility and its timing in many Western nations such as the US (Butz, and Ward 1980), Britain (De Cooman et al. 1987; Ermisch 1988; Murphy 1992), Italy (Aasvee et al. 2001) Spain (Ahn and Mira 2001, Gutierrez 2008), Sweden (Hoem and Hoem 1989; Hoem 2000), Norway (Kravdal 2002), Germany (Kreyenfeld, M. 2009) and Europe (Adsera 2005, 2011), among others.

Temporary employment also rose in Italy during the late 1980s and the 1990s as employers were searching for means to reduce non-wage costs and in many cases took the form of informal continuous agreements where employees would file taxes as self-employed though they would effectively work within a firm. Some of those jobs are not counted under the EUROSTAT definition.

For detailed information on contributory periods and levels of benefits, see OECD 2002. By way of example, maternity leaves required a minimum contributory period ranging from 3 days in Denmark to 6 months in Portugal and 26 weeks in the United Kingdom. In Spain maternity benefits are received for 16 weeks and the current minimum contributory period is 180 days in the last 7 years (shorter for very young mothers). Slightly longer contributory periods were needed to receive unemployment benefits.

Speder and Kapitany (2009) also find that adverse employment conditions limit the realization of fertility intentions in Hungary.

Kreyenfeld (2009) finds that among Eastern and Western German women, the highly educated are the most inclined to postpone first births when subject to employment uncertainties and concerns about the security of their jobs.

Unfortunately, because the survey does not provide complete retrospective fertility history we cannot account for children who have died. However, in the European context we expect this number to be small.

The cross-country variation in labor market characteristics is greater than the within-country, so excluding country dummies is likely to result in more precise estimates. However, because there may be omitted country-specific factors that are correlated with labor market characteristics and fertility, estimates using cross-country variation may be confounded. The use of within-country variation by adding country dummies to account for unobservables addresses this source of confounding, but at the expense of losing some variation (precision).

Several works conclude that attrition biases in the ECHP are relatively mild and low for individuals living in couples as the great majority in this sample (Nicoletti and Peracchi 2002, Ehling and Rendtel 2004).

Estimates are robust to the inclusion of information on the employment conditions of the partner, if present.

In separate models available upon request, when country dummies are excluded, the coefficient on female monthly unemployment is significant at 1 percent level.

Cohorts are defined as 1. born before 1950; 2. 1950–59; 3. 1960–67; 4. 1968–75; 5. born after 1975.

This finding has previously been partly attributed to selection in the European literature (Hoem and Hoem 1989, Kravdal 2001). Also it may be related to economies of scale in raising children.

Practicing Catholics followed by Catholic not practicing transit the fastest to second births. Living in rental housing instead of owning the house is not relevant. Most of the selection arising from housing conditions is more important in the transition to motherhood or leaving the parental home rather than for second births. (Holdsworthet al. 2002).

References

- Aassve FA, Billari C, Ongaro F. The impact of income and occupational status on leaving home: evidence from the Italian ECHP sample. Labour. 2001;15(3):501–529. [Google Scholar]

- Addison JT, Teixeira P. The Economics of Employment Protection. Journal of Labor Research. 2003;24(1):85–128. [Google Scholar]

- Adsera A. Vanishing Children: From high Unemployment to Low Fertility in Developed Countries. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings. 2005;95(2):198–193. doi: 10.1257/000282805774669763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adsera A. An Economic Analysis of the Gap between Desired and Actual Fertility: The Case of Spain. Review of Economics of the Household. 2006 Mar4(1):75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Adsera A. Where Are the Babies? Labor Market Conditions and Fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population. 2011;21(1):1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10680-010-9222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam P. Mothers in an Insider-Outsider Economy: The Puzzle of Spain. Journal of Population Economics. 1996;9:301–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00176690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn N, Mira P. Job Bust, Baby Bust? Evidence from Spain. Journal of Population Economics. 2001;14:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Kreyenfeld M, Mika T. MPIDR Working Papers 2009–026. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research; 2009. Welfare state context, female earnings and childbearing. [Google Scholar]

- Azmat G, Guell M, Manning A. Gender gaps in unemployment rates in OECD countries. Journal of Labor Economics 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bertola G, Blau F, Kahn L. Working Paper No W9043. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2002. Labor Market Institutions and Demographic Employment Patterns. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard O, Landier A. The Perverse effects of partial labour market reform: Fixed-term contracts in France. Economic Journal. 2002;112(480):F214–F244. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, Kurz K. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. Oxford: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J. The End of the Fertility Transition in the Developed World. Population and Development Review. 2002;28(3):419–443. [Google Scholar]

- Booth AJ, Dolado J, Frank J. Symposium on temporary work: Introduction. Economic Journal. 2002;112(480):F181–F188. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Francesconi M, Frank J. Temporary Jobs: Stepping stones or Dead ends? Economic Journal. 2002;112:F189–F213. [Google Scholar]

- Browning M. Children and Household Economic Behavior. Journal of Economic Literature. 1992;30:14–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Butz W, Ward M. Completed Fertility and Its Timing. Journal of Political Economy. 1980;88:917–40. [Google Scholar]

- De Cooman E, Ermisch J, Joshi H. The Next Birth and the Labour Market: A Dynamic Model of Births in England and Wales. Population Studies. 1987;41:237–268. ???. [Google Scholar]

- Dolado JJ, García-Serrano C, Jimeno JF. Drawing Lessons from the Boom of Temporary Jobs in Spain. The Economic Journal. 2002;112:270–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ehling M, Rendtel U. The Change from Input Harmonisation to Ex-post Harmonisation in National Samples of the European Community Household Panel (Chintex) Federal Statistical Office of Germany; 2004. Research Results of Chintex - Summary and Conclusions. [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch J. Econometric Analysis of Birth Rate Dynamics in Britain. The Journal of Human Resources. 1988;23(4):563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Galor O, Weil D. The Gender Gap, Fertility and Growth. American Economic Review. 1996;86:374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier AH. The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review. 2007;26(3):323–346. [Google Scholar]

- González MJ, Jurado T. Remaining childless in affluent economies: a comparison of France, West Germany, Italy and Spain. European Journal of Population. 2006;22:317–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Domenech M. The Impact of the Labour Market on the Timing of Marriage and Births in Spain. Journal of Population Economics. 2008;21(1):83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem B. Entry into motherhood: the influence of economic factors on the rise and fall in fertility, 1986–1997. Demographic Research. 2000:4. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem B, Hoem J. The Impact of Women’s Employment on Second and Third Births in Modern Sweden. Population Studies. 1989;43:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth C, Irazoqui-Solda M. First housing Moves in Spain: An analysis of Leaving Home and First Housing Acquisition. European Journal of Population. 2002;18:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Holmlund B, Kolm AS, Storrie D. Temporary Jobs in Turbulent Times: The Swedish Experience. The Economic Journal. 2002;112:245–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Billari F, Ortega JA. The Emergence of Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe During the 1990s. Population and Development Review. 2002;28(4):599–639. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal O. The High Fertility of College Educated Women in Norway. Demographic Research. 2001:5. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal O. The Impact of individual and aggregate unemployment on fertility in Norway. Demographic Research. 2002:6. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M. Uncertainties in female employment careers and the postponement of parenthood in Germany. European Sociological Review. 2009;26(3):351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Surkyn J. Cultural Dynamics and Economic Theories of Fertility Change. Population and Development Review. 1988;14(1):1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Wei LJ. The Robust Inference of the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP. Low Fertility in the Twenty-First Century. Demography. 2003;40(4):589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. Economic Models of Fertility in Post-war Britain: A Conceptual and Statistical Re-interpretation. Population Studies. 1992;46:235–58. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000146216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti C, Peracchi F. ISER Working Paper 2002–32. 2002. A Cross-Country Comparison of Survey Nonparticipation in the ECHP. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. OECD; Paris: 2002. Chapter 3: Taking the measure of temporary employment. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti C, Peracchi F. OECD Employment Outlook. OECD; Paris: 2004. Chapter 2: Employment protection regulation and labour market performance. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Paul G. IZA, Discussion paper. 2000. Flexibility vs. Rigidity: Does Spain have the Worst of both Worlds? p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Speder Z, Kapitany B. How are Time-Dependent Childbearing Intentions Realized? Realization, Postponement, Abandonment, Bringing Forward. European Journal of Population 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Is lowest-low fertility in Europe explained by the postponement of childbearing? Population and Development Review. 2004;30(2):195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T, Skirbekk V, Philipov D. A literature review, Research Note (produced for the European Commission) Vienna, Austria: Vienna Institute of Demography; 2010. Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Social Security Programs throughout the World. Washington DC: (various years) [Google Scholar]