Abstract

Background

Recent studies have shown that pharmacists have a role in addressing antidepressant nonadherence. However, few studies have explored community pharmacists’ actual counseling practices in response to antidepressant adherence-related issues at various phases of treatment. The purpose of this study was to evaluate counseling practices of community pharmacists in response to antidepressant adherence-related issues.

Methods

A simulated patient method was used to evaluate pharmacist counseling practices in Sydney, Australia. Twenty community pharmacists received three simulated patient visits concerning antidepressant adherence-related scenarios at different phases of treatment: 1) patient receiving a first-time antidepressant prescription and hesitant to begin treatment; 2) patient perceiving lack of treatment efficacy for antidepressant after starting treatment for 2 weeks; and 3) patient wanting to discontinue antidepressant treatment after 3 months due to perceived symptom improvement. The interactions were recorded and analyzed to evaluate the content of consultations in terms of information gathering, information provision including key educational messages, and treatment recommendations.

Results

There was variability among community pharmacists in terms of the extent and content of information gathered and provided. In scenario 1, while some key educational messages such as possible side effects and expected benefits from antidepressants were mentioned frequently, others such as the recommended length of treatment and adherence-related messages were rarely addressed. In all scenarios, about two thirds of pharmacists explored patients’ concerns about antidepressant treatment. In scenarios 2 and 3, only half of all pharmacists’ consultations involved questions to assess the patient’s medication use. The pharmacists’ main recommendation in response to the patient query was to refer the patient back to the prescribing physician.

Conclusion

The majority of pharmacists provided information about the risks and benefits of antidepressant treatment. However, there remains scope for improvement in community pharmacists’ counseling practice for patients on antidepressant treatment, particularly in providing key educational messages including adherence-related messages, exploring patients’ concerns, and monitoring medication adherence.

Keywords: simulated patients, antidepressant medications, medication adherence, community pharmacist

Introduction

Nonadherence to antidepressant medications is a common problem in the treatment of depression, and has been associated with adverse outcomes, such as increased risk of relapse and recurrence.1,2 Nonadherence problems occur at different stages of treatment, and range from patients not filling their initial prescriptions, omitting or self-adjusting their doses, to discontinuing treatment prematurely against medical advice.3 Although clinical guidelines recommend antidepressants be continued for at least 6 months after symptom remission,4,5 approximately one third of patients discontinue antidepressants within the first month of treatment, and 44% discontinue them by the third month of treatment.6 A number of factors have been identified as contributing to antidepressant medication nonadherence, including stigma associated with depression, clinical factors such as substance abuse and presence of comorbidities, side effects of antidepressants, and patients’ beliefs about antidepressant medications.3,7,8

Effective interactions between patients and health care practitioners have been shown to be important in patients’ acceptance of antidepressants and continuation of treatment.9,10 Patients who have received specific educational messages, such as time to onset of action and to continue taking antidepressants even if feeling better, were more likely to adhere to antidepressant treatment.6,11 In addition, patients who discussed adverse effects with their physicians were also more likely to continue treatment.10 However, physicians do not always fulfill the information needs of patients starting antidepressant treatment, and may omit important information necessary for patients to make informed decisions about treatment and to ensure adherence.12,13 Patients themselves have indicated that the information they received from health care practitioners about their antidepressant treatment is generally inadequate.14–16

Given that community pharmacists frequently encounter patients with depression, they can play an instrumental role in addressing antidepressant nonadherence issues and responding to patients’ information needs. Findings from recent systematic reviews indicate that pharmacist interventions can be effective in the improvement of adherence to antidepressant medications.17–19 For patients starting antidepressant treatment, community pharmacists can play an important role by exploring barriers to accepting treatment, clarifying common misconceptions, and providing key educational messages about antidepressant medications. Similarly, community pharmacists are well placed to follow up patients on continued therapy by regularly monitoring their medication use, treatment efficacy, adverse effects, and other medication-related problems that are likely to influence use of antidepressant medications. In a US study, pharmacist monitoring positively influenced both satisfaction and adherence for patients taking antidepressant medications for the first time.20 In addressing medication-related problems though, it is imperative for pharmacists to apply their expertise in a manner that acknowledges individual patient needs, concerns, experiences, and expectations.21,22

Although community pharmacists have expressed positive attitudes towards a wider role in depression care, extending this role in practice has appeared to be more difficult in comparison with care for patients with physical health conditions.23 Data from Belgium, Canada, and the UK suggest that although pharmacists appeared comfortable in providing information with first-time antidepressant prescriptions, they often seemed to have less involvement after treatment has started.23–25 In one study, pharmacists reported that they monitored patients with mental illness (including depression) for medication side effects and adherence less frequently than patients with cardiovascular problems.26 Some major barriers to pharmacists’ communication with antidepressant users have been identified; these include lack of privacy and time, lack of pharmacist education about mental health issues, and pharmacists perceiving that people with depression are not interested in discussing their treatment.23–25

Previous studies have mostly focused on patients starting antidepressant treatment, and have mainly used surveys or interviews to assess pharmacist-patient interactions in depression care. While providing important data, these studies relied on participants’ self-report to assess pharmacists’ counseling process, and may thus be subjected to participants’ recall bias. Hence, in this study, we used an observational, simulated patient method to investigate the current practice of Australian community pharmacists in response to antidepressant adherence-related issues at different phases of treatment. A report of the broad characteristics of pharmacists’ communication behaviors (such as biomedical and lifestyle/psychosocial exchanges, partnership-building, and rapport-building) has been presented elsewhere.27 For the purposes of this paper, we assessed specifically the content of pharmacist consultations in terms of information gathering, information provision including key educational messages pertaining to antidepressant medication adherence, and treatment recommendations.

Methods

Simulated patient methodology

A simulated patient approach was used to assess pharmacist consultations. The methods described here have also been reported elsewhere.27 Trained simulated patients entered the pharmacy and enacted prespecified scenarios to assess pharmacists’ counseling practices, without pharmacists being aware of the simulated patient’s identity. The use of simulated patients in pharmacy practice research has been described as an effective method of obtaining objective and reliable data on pharmacists’ counseling practices.28

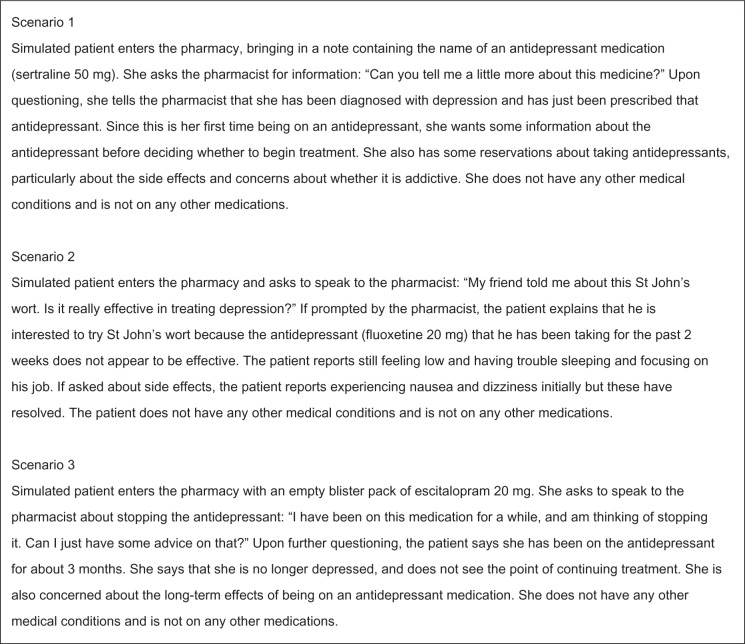

Three case scenarios were developed based on the literature3,29–31 and the researchers’ experiences of common medication-related problems in community pharmacy practice. Previous literature has identified time points during the course of antidepressant treatment when patients may benefit from intervention by a health care practitioner.30 These include at the start of antidepressant treatment, during the latency period of the medication when there is an absence of a noticeable therapeutic effect, and when patients experience a return to function. Thus, scenarios for this study were developed to reflect potential nonadherence issues at these phases of antidepressant treatment: patients receiving a prescription for an antidepressant for the first time and being hesitant to begin treatment; patients who commenced antidepressant treatment 2 weeks ago but perceive that the treatment is ineffective; and patients wanting to discontinue antidepressant treatment after 3 months once they began to feel better (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of simulated patient scenarios.

Three simulated patients were recruited for this study, with each assigned to perform one scenario. The simulated patients received structured training that encompassed review of case scenarios, delivery of scenarios using standardized scripts, and conducting role plays with practicing community pharmacists.

Recruitment of community pharmacists

Pharmacists were contacted by a study information letter that was posted to 120 community pharmacies around Sydney, Australia. Twenty community pharmacists consented to participate. All participating pharmacists gave written informed consent to be visited by three unannounced simulated patients within a 6-month period, and consented to covert audio recording of these visits. Pharmacists were informed that the study was investigating pharmacist-patient communication on common medication-related problems; however they were not informed that the visits would concern the use of antidepressant medications. Upon enrolment, participating pharmacists completed a brief questionnaire on their demographic details, whereas pharmacy managers completed a questionnaire on information regarding the pharmacy. Approval for the conduct of this study was granted by the institution’s human research ethics committee.

Data collection

The main data collection phase was between December 2011 and May 2012. Each pharmacist received three unannounced simulated patient visits, with approximately a month’s gap between visits. The consultations were covertly audio recorded using hidden digital recorders carried by the simulated patients. The simulated patients were instructed, as far as possible, to disclose information only when prompted by the pharmacist. On completion of a visit, the researcher listened to the audio tape and discussed the consultation with the simulated patient. The researcher then entered the pharmacy to inform the pharmacist that a simulated patient visit had just taken place. The pharmacist was given the opportunity to reflect and comment on his or her interaction with the simulated patient.

Data coding

Pharmacist consultations were assessed by analyzing audio recordings of interactions between pharmacists and simulated patients. A detailed checklist was developed for each scenario based on previous literature6,10,11,14,15,20,25,31 and content of the consultations. This checklist was developed by the research team to evaluate the content of consultations in terms of information gathering, information provision, and treatment recommendations by community pharmacists. In addition, provision of key educational messages shown by previous studies to improve antidepressant medication adherence6,10,11 were also assessed. In scenario 1, key educational messages also included the information needs of patients starting antidepressant treatment, as indicated by patients in previous studies.14,15,25

In addition, the length of consultations, number of questions asked, and number of items of information provided in pharmacist consultations were assessed. Adherence-related messages in pharmacist consultations were also examined. These were messages that encouraged consistency in medication-taking behavior in the context of ongoing use (medication compliance), or reinforcing the need to continue the treatment as prescribed and/or according to treatment guidelines (medication persistence).18,32

Results

Demographic details

Twenty community pharmacists from 15 pharmacies participated. The majority of participating pharmacists were male (75%), and most were in the age group 20–29 years (70%). The number of years since registration for pharmacists ranged between one and 39 years, with a mean of 7.7 ± 9.1 years. Of the 15 pharmacies, seven (46.7%) were chain pharmacies while the rest were independent pharmacies. The majority of pharmacies (66.7%) indicated that they dispensed ≤200 prescriptions per day. Twelve (80%) of the pharmacies indicated the availability of a private counseling area.

Content of consultations

Scenario 1: patient starting antidepressant treatment for the first time

Table 1 presents the content of pharmacist consultations in scenario 1. The question most frequently asked by pharmacists concerned the information given by the general practitioner about the antidepressant medication (80%). About two thirds of pharmacists enquired about the patient’s concerns regarding starting antidepressant treatment. Less than half of the pharmacists enquired about the patient’s medical condition (30%).

Table 1.

Content of pharmacist consultations (n = 20 visits) in scenario 1

| Content of information | n | % of visits |

|---|---|---|

| Information gathering | ||

| Who the medication is for | 11 | 55 |

| Patient’s prior use of antidepressant medication or other treatment for depression* | 12 | 60 |

| Information given by general practitioner about antidepressant medication and other treatment options (or reason for prescribed antidepressant) | 16 | 80 |

| Questions about patient’s medical condition (eg, depression symptoms, severity) | 6 | 30 |

| Probe for patient’s concerns about antidepressants* | 13 | 65 |

| If the patient takes any other medications | 8 | 40 |

| If the patient has any other medical conditions | 2 | 10 |

| Information provision | ||

| Indication/mechanism of action | ||

| Explanation of indication/purpose of antidepressant | 16 | 80 |

| Biomedical explanation of depression as an illness and how antidepressant works* | 11 | 55 |

| Technical information | ||

| Dosage or strength of the medication* | 9 | 45 |

| Timing/schedule (how or when to take the medication)* | 7 | 35 |

| Expected benefits | ||

| Expected benefits from antidepressants (eg, target symptoms)* | 14 | 70 |

| Timeframe of treatment | ||

| Time to onset of effects for antidepressants* | 12 | 60 |

| Expected duration of antidepressant treatment* | 7 | 35 |

| Dosage needs to be tapered off slowly before stopping* | 10 | 50 |

| Adherence messages | ||

| Continue to take medicine even if feeling better* | 3 | 15 |

| Don’t stop taking it without checking with a doctor/pharmacist* | 5 | 25 |

| Take it on a daily basis without interruption* | 4 | 20 |

| Not to take any more than the usual dosage | 1 | 5 |

| Side effects | ||

| Common possible side effects of antidepressants* | 15 | 75 |

| Management of common side effects* | 8 | 40 |

| When or how long side effects might be* | 7 | 35 |

| Provides explanation of the term dependency or addiction in the context of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use* | 9 | 45 |

| Information resources | ||

| What to do if there are questions or concerns about the antidepressant* | 8 | 40 |

| Provides written information about antidepressants* | 15 | 75 |

| Recommendations of information sources (eg, websites)* | 3 | 15 |

| Nonpharmacologic management | ||

| Discussions of lifestyle and psychosocial activities* | 3 | 15 |

| Discussions of nonpharmacologic treatment alternatives (eg, seeking counseling or other professional help)* | 8 | 40 |

| Other | ||

| Information about generic versus original brands for medication | 2 | 10 |

Note:

Information shown by previous studies to be associated with improved antidepressant medication adherence, and/or information needs of patients starting antidepressant treatment.

In terms of information provision, information items most frequently provided were pertaining to the purpose of the antidepressant (80%), possible side effects (75%), and expected benefits from antidepressants (70%). In 75% of the consultations, written information in the form of a standardized Australian consumer medicine information leaflet was also provided. A smaller proportion of pharmacists provided information on time to onset of effects (60%), and a biomedical explanation of depression illness and how an antidepressant works (55%).

Other key information associated with improved antidepressant medication adherence and/or patients’ information needs were less often addressed by pharmacists. Less than half of the pharmacists provided information about the usual duration of treatment (35%), the management of side effects (40%), the timing and frequency of side effects (35%), dependency in the context of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use (45%), and nonpharmacologic treatment alternatives (40%). Adherence messages, such as to continue taking antidepressant medication even if feeling better, were also mentioned infrequently (in 5%–25% of consultations, depending on type of adherence messages). Advice on information sources such as websites (15%) and discussions of lifestyle and psychosocial activities (15%) were also rarely mentioned.

Scenario 2: patient interested in st John’s wort as a treatment alternative after perceiving lack of treatment effectiveness with antidepressants

Table 2 details the content of pharmacist consultations in scenario 2. Most pharmacists enquired about how long the patient had been on the antidepressant (90%). In half of the consultations, pharmacists enquired about the way the patient was currently taking the antidepressant. Twelve (60%) pharmacists enquired about the patient’s main concern regarding lack of symptom improvement, while 40% asked whether the patient had any other concerns and barriers to taking antidepressant medication, such as side effects.

Table 2.

Content of pharmacist consultations (n = 20 visits) in scenario 2

| Content of information | n | % of visits |

|---|---|---|

| Information gathering | ||

| Who the product (st John’s wort) is for | 5 | 25 |

| If the patient has sought medical help for depression or is already taking an antidepressant | 14 | 70 |

| How is the patient taking the antidepressant (eg, dose/timing)* | 10 | 50 |

| How long has the patient been taking the antidepressant | 18 | 90 |

| Probe on patient’s main concern about lack of improvement in symptoms (eg, questions on current depression symptoms)* | 12 | 60 |

| Probe for patient’s other concerns and barriers to using the antidepressant (such as side effects)* | 8 | 40 |

| If the patient takes any other medications in addition to the antidepressant | 5 | 25 |

| Information provision | ||

| Use of St John’s wort | ||

| Information about use of St John’s wort in depression | 19 | 95 |

| Interaction | ||

| Precaution about use of St John’s wort together with antidepressants (risk of serotonin toxicity) | 18 | 90 |

| Information on switching fluoxetine to another antidepressant/St John’s wort | 4 | 20 |

| Timeframe of treatment | ||

| Time to onset of effects for antidepressants* | 18 | 90 |

| Expected duration of antidepressant treatment* | 2 | 10 |

| Adherence messages | ||

| Take antidepressant on a daily basis* | 3 | 15 |

| Information resources | ||

| Provides written information about St John’s wort/depression | 3 | 15 |

| Recommendations of information sources (eg, websites) | 4 | 20 |

| Nonpharmacologic management | ||

| Discussions of lifestyle and psychosocial activities or stressors related to depression* | 4 | 20 |

| Discussions of nonpharmacologic alternatives (eg, counseling or psychotherapy) | 7 | 35 |

| Treatment recommendations | ||

| Provides advice to persist with antidepressant treatment* | 14 | 70 |

| Provides advice to go to the general practitioner if still no improvement in symptoms | 18 | 90 |

| Provides reassurance of the availability of other antidepressants as treatment alternatives | 8 | 40 |

| Provides recommendations for over-the-counter products to help with symptom (eg, sleeplessness) management | 5 | 25 |

| Advise patient to return to the pharmacy if any further questions or concerns | 4 | 20 |

Note:

Information shown by previous studies to be associated with improved antidepressant medication adherence.

In terms of information provision, nearly all pharmacists (95%) provided information on St John’s wort, such as its effectiveness in the treatment of depression. All except two pharmacists cautioned the patient about the risk of serotonin toxicity with the concomitant use of St John’s wort and an antidepressant. Most pharmacists (90%) also explained that it would usually take 4–6 weeks for antidepressant medications to show an optimum effect. Information least frequently provided included expected duration of antidepressant treatment (10%), taking the antidepressant medication on a daily basis (15%), other information sources (20%), and discussions on lifestyle/psychosocial activities (20%). Only three pharmacists (15%) provided written information about St John’s wort or depression.

Related to the above information provision on time to onset of effects, the main recommendations by pharmacists were for the patient to persist with antidepressant treatment for another two weeks, and to see the general practitioner if there is still no improvement in symptoms. The majority of pharmacists (60%) made both of these recommendations. Pharmacists who recommended for the patient to persist with treatment reassured the patient that an improvement in symptoms would likely occur over the following weeks. Pharmacists used the following reasons to support their recommendation for the patient to see the general practitioner: the doctor can increase the dosage of the medication, prescribe adjunct treatment, switch the patient to another antidepressant, and/or refer the patient to psychotherapy services.

Scenario 3: patient wanting to discontinue antidepressant treatment after 3 months due to perceived symptom improvement

Table 3 shows the content of pharmacist consultations in scenario 3. Thirteen (65%) pharmacists probed for the patient’s reasons for wanting to discontinue antidepressant treatment, whereas 40% explored additional concerns and barriers to using the antidepressant. As in the previous scenario, pharmacists enquired about the patient’s antidepressant use (including whether the patient was still taking the antidepressant) in half of the consultations. Only 25% of pharmacists ascertained that the patient still had an adequate supply of antidepressant medication.

Table 3.

Content of pharmacist consultations (n = 20 visits) in scenario 3

| Content of information | n | % of visits |

|---|---|---|

| Information gathering | ||

| Why is the patient taking the antidepressant medication | 6 | 30 |

| If the patient has been to see the general practitioner recently | 13 | 65 |

| How has the patient been taking the antidepressant (eg, whether patient is still taking the antidepressant or questions about dose and timing)* | 10 | 50 |

| How long has the patient been taking the antidepressant | 14 | 70 |

| Probes for patient’s reasons for wanting to discontinue antidepressant treatment* | 13 | 65 |

| Probes for patient’s additional concerns (such as long-term effects) and barriers to using the antidepressant (such as side effects)* | 8 | 40 |

| Ascertain patient has adequate supply of antidepressant medication* | 5 | 25 |

| If the patient takes any other medications in addition to the antidepressant | 5 | 25 |

| If the patient has any other medical conditions | 1 | 5 |

| Information provision | ||

| Timeframe of treatment | ||

| Time to onset of effects for antidepressants* | 3 | 15 |

| Duration of antidepressant treatment according to treatment guidelines* | 5 | 25 |

| Explains importance of continuing antidepressant treatment/risks associated with premature discontinuation (eg, increased risk of relapse)* | 6 | 30 |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Address patient’s concerns about harms of long-term antidepressant treatment* | 4 | 20 |

| Information resources | ||

| Provides written information about antidepressant* | 5 | 25 |

| Nonpharmacologic management | ||

| Discussions of lifestyle and psychosocial activities or stressors related to depression* | 2 | 10 |

| Discussions of herbal supplements (eg, St John’s wort) and nonpharmacologic alternatives (eg, counseling, psychotherapy) | 2 | 10 |

| Treatment recommendations | ||

| Encourage patient to go to the general practitioner for treatment follow-up or further advice | 19 | 95 |

| Provides advice against sudden discontinuation of antidepressant (eg, explanation on withdrawal symptoms)* | 19 | 95 |

| Provides instructions on tapering off antidepressant treatment | 11 | 55 |

| Recommend patient to stay on treatment for at least 6 months* | 3 | 15 |

Note:

Information shown by previous studies to be associated with improved antidepressant medication adherence.

Few pharmacists provided information on the duration of antidepressant treatment (25%), the risks associated with premature discontinuation of treatment (30%), lifestyle/psychosocial activities (10%) and other treatment options (10%). In addition, only 20% of pharmacists addressed the patient’s concerns about harms of long-term antidepressant treatment, and only 25% provided written information about the antidepressant.

In 95% of the consultations, pharmacists advised the patient to seek advice from the general practitioner about stopping antidepressant treatment. Pharmacists mostly explained that it was not their role to provide advice on stopping treatment because they do not have adequate information about the patient’s medical history. Pharmacists also emphasized that the patient should not stop treatment abruptly without discussing this with the general practitioner first, and explained the associated risk of withdrawal symptoms. Some pharmacists told the simulated patient that she could stop the medication if she genuinely felt that it was not needed; however, they emphasized that the treatment would have to be tapered down slowly according to the general practitioner’s advice. Only three (15%) pharmacists advised the patient to stay on treatment for at least 6 months.

Summary measures of pharmacist communication

Table 4 presents the summary measures of pharmacist communication in the three scenarios. There was considerable variability among individual pharmacists in terms of the length of consultations within each scenario. Across the scenarios, the median length of consultation was highest in scenario 1 (median 5:11 minutes, interquartile range 4:20–8:43 minutes), as compared with scenario 2 (median 4:56 minutes, interquartile range 2:49–6:14 minutes) and scenario 3 (median 3:58 minutes, interquartile range 3:14–6:23 minutes).

Table 4.

Descriptions of pharmacist consultations on antidepressant-related issues

| Summary measures | Scenario 1 (n = 20) | Scenario 2 (n = 20) | Scenario 3 (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent counseling patients (minutes and seconds) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6:18 (3:13) | 5:20 (3:34) | 4:58 (2:35) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 5:11 (4:20–8:43) | 4:56 (2:49–6:14) | 3:58 (3:14–6:23) |

| Range | 0:45–12:32 | 1:24–16:56 | 2:03–10:48 |

| Number of questions asked | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.9) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 3.0 (2.3–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| Range | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–8.0 |

| Number of information and treatment recommendations provided | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.9 (3.4) | 6.5 (1.9) | 4.0 (1.3) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 9.0 (6.0–11.8) | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Range | 4.0–16.0 | 3.0–10.0 | 2.0–6.0 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Within each scenario, there was also variability in terms of the number of questions asked and number of items of information provided among the individual pharmacists. Across the scenarios, the median number of questions asked by pharmacists was consistent. However, the number of items of information provided was not; this was highest in scenario 1 (median 9.0, interquartile range 6.0–11.8) and decreased across the other two scenarios (median 6.0, interquartile range 5.0–8.0 for scenario 2; median 4.0, interquartile range 3.0–5.0 for scenario 3).

The types and examples of adherence messages and recommendations in pharmacist consultations are listed in Table 5. Most of the adherence messages consisted of advice to persist with antidepressant treatment, mainly in response to the patient’s query about wanting to stop antidepressant treatment due to perceived lack of treatment efficacy (scenario 2) or improvement in condition (scenario 3). Pharmacists mentioned both aspects of adherence (compliance and persistence) in only a few of the consultations.

Table 5.

Examples of adherence messages mentioned by community pharmacists in consultations

| Aspect of adherencea | Types of adherence messages | Study examples |

|---|---|---|

| Compliance | Take antidepressant medication daily | “It’s very important to be taken every day.” (Scenario 1) “And under no circumstances do you miss dose.” (Scenario 1) |

| Antidepressant is not a medication to take on and off | “It’s not a medication where you want to start and stop […] So you’ve got to sort of keep it consistent.” (Scenario 1) “And you need to be taking it regularly to see the full effects.” (Scenario 2) |

|

| Do not take any more than the usual dosage | “Don’t take any more than the usual dosage.” (Scenario 1) | |

| Persistence | Take antidepressant medication even if feeling better | “But it’s not an on and off thing. It’s not a one week – oh no, no I feel fine. You make a decision, you stick to it.” (Scenario 1) “In three months, it’s not long enough […] You feel so much better because you’ve been on it […] In three months, that’s not enough for repair.” (Scenario 3) “And the fact that you are feeling a lot better could be because of the tablets, and if you stop it so quickly then there is a chance, there is that risk that you’re going to hit low again.” (Scenario 3) |

| Continue antidepressant medication although the effect may not be noticed straight away | “The full effect may take about 4–6 weeks to manifest. So you will need to be a little patient when you start taking this medicine.” (Scenario 1) “Definitely stick to the Lovan for now. Don’t feel too discouraged that it’s not going to work straight away. But just to give it some time.” (Scenario 2) “Look, I say persist with it. You may find that, you might start to get the benefit in the next couple of weeks.” (Scenario 2) |

|

| Do not stop antidepressant suddenly/without discussing with the doctor | “You can’t just wake up in the morning and say I don’t want to take it anymore.” (Scenario 1) “My advice to patients is to keep taking their medication, and don’t stop it unless the doctor advises them to.” (Scenario 3) “It’s essential that you keep taking it unless the doctor advises otherwise.” (Scenario 3) |

|

| Take antidepressant for at least 6 months | “If you’re gonna start, then you go for the full 6 months.” (Scenario 1) “Usually once you go on this medication, you stay on it for about 6–12 months. To go off it too quickly, it won’t be as effective.” (Scenario 2) “And we know from research, that people who stay on this for you know, 6 months once they get treated, then they feel better. Then they’re much less likely to have depression coming back, you know.” (Scenario 3) |

Pertaining to pharmacists’ reflections on their interactions with the simulated patients, the majority of pharmacists who commented on the visits were satisfied with the information that they had provided. A few pharmacists acknowledged that they could have spent more time with the simulated patient, and could have provided more information or asked more questions. Time constraint was cited as the main factor for not doing so. Other reasons included the patient not having a proper prescription with her (scenario 1), wanting to focus on the patient’s main concern about stopping antidepressant treatment (scenario 3), and not wanting to seem intrusive with questions (scenario 3). In most of the visits, pharmacists said they did not suspect the visits involved simulated patients, and commented that the scenarios reflected enquiries about medication they would receive in routine practice.

Discussion

This study provides a description of community pharmacists’ current practice pertaining to their roles in improving antidepressant medication adherence, such as in providing key information and adherence-related messages, assessing patients’ medication-taking behavior and concerns, and providing treatment recommendations. The findings of this study add to the literature by examining actual counseling practices of community pharmacists in their practice settings pertaining to their roles in this area, rather than focusing on proxy measures. In addition, it allowed some comparisons with pharmacist self-reported practice from previous studies.23–25,33 In general, there was variability in counseling practices among community pharmacists in terms of the extent and content of information gathered and provided, as well as the length of time spent in each consultation. This variability is consistent with findings from previous research.20,34 The content of consultations was mainly focused on the therapeutic aspects of antidepressant treatment, and few pharmacists questioned the simulated patients about their medical condition, for example, their experiences with depression, or discussed psychosocial-related issues with them. Information provision also appeared to be focused on patients who were initiating antidepressant treatment for the first time compared with patients who were on continuing treatment. This study also identified several areas for improvement in pharmacists’ practice, notably the provision of key educational messages about antidepressants including adherence-related messages, probes for patients’ concerns about treatment, and medication adherence monitoring.

For patients starting antidepressant treatment for the first time (as portrayed in scenario 1), provision of key educational messages is important in improving medication adherence.6 Community pharmacists in this study focused mainly on providing information about the possible side effects and expected benefits from antidepressants. This finding is encouraging, because patients need to be informed about both the potential risks and therapeutic benefits of antidepressant medications in order to make informed decisions about treatment. Early information on side effects has also been shown to offset premature discontinuation of treatment.10 However, other key educational messages were covered less well by pharmacists in this study, including time to onset of effects (60%) and the expected duration of antidepressant treatment (35%). These findings are comparable with those of a previous study by Bultman and Svarstad20 which indicated that although most patients (81%) know about the adverse effects of antidepressants, only 64% know about the onset of benefits and only 30% know the recommended length of treatment. This finding may have important clinical relevance, because early discussion about the timeframe and recovery process associated with antidepressant treatment has been shown to be important in preventing premature discontinuation of treatment.10

Consistent with previous studies,24,25 information provision, including written information, appeared to be focused mainly on first-time antidepressant users compared with patients who are already on treatment. This interpretation is supported by data on the length of consultations, which was highest in scenario 1. However, patients starting antidepressant treatment often report having difficulties recalling information received at the time of diagnosis.14 Thus, it may be essential for pharmacists to reiterate key educational messages at every follow-up opportunity as treatment progresses. Consequently, the development of resources for community pharmacists, such as checklists, may be useful in ensuring that key information about antidepressant medication is provided to patients at the start of therapy and at each follow-up visit.

In terms of adherence messages, this study found that important messages, such as to take the medication on a daily basis and to continue taking medication after symptom remission, were rarely addressed by pharmacists at the start of treatment (scenario 1). This finding contrasts somewhat with another study where 93% of pharmacists reported that they would tell the patient to take the antidepressant medication on a daily basis.33 This difference may be attributed to use of different data collection methods (simulated patient methods versus pharmacist self-report), suggesting that there may be a difference in what pharmacists say they would do compared with their actual practice. However, it is also possible that pharmacists may have intended to encourage adherence indirectly, for example, by reassuring the patient about the rarity of side effects or by providing information about the expected benefits from antidepressant treatment. Nevertheless, provision of these adherence messages has been identified by previous studies to be important in enhancing adherence to antidepressant medications.6,11 In the scenarios involving patients on continued treatment (scenarios 2 and 3), adherence messages to persist with treatment were provided mainly in response to the patient’s query about stopping antidepressant treatment. However, these messages were often not followed by a clear explanation about the importance of medication adherence to depression treatment outcomes; for example, only 30% of pharmacists in scenario 3 explained the risk of relapse with premature discontinuation of treatment.

In addition, pharmacists in this study assessed patients’ medication use in only half of the consultations in scenarios 2 and 3. This is consistent with findings from a previous study,24 which reported low rates of direct questioning from community pharmacists regarding patients’ adherence to antidepressant treatment. Pharmacists in previous studies have also reported feeling unable to monitor how and whether patients were taking their antidepressants.25,31 Our study also indicates the need to strengthen pharmacists’ roles in medication adherence monitoring, in addition to having important adherence-related discussions with patients on antidepressant treatment.

The literature has recommended that nonadherence be viewed from a perspective situated in the patient’s experience of illness.22 Although information provision is important in promoting medication adherence, without adequately exploring and acknowledging the medication concerns of individual patients, this can be regarded as a paternalistic approach to adherence.22 Pharmacists need to be more than just providers of information if they wish to become patient-centered practitioners. In this study, about two thirds of pharmacists enquired about the patient’s concerns regarding starting antidepressant treatment in scenario 1, and probed for details on patients’ main concerns about their treatment in the other scenarios. In 40% of the consultations in scenarios 2 and 3, pharmacists also probed for the patient’s additional concerns and barriers to using the antidepressant, such as side effects. These rates are lower than those reported in the study by Bultman and Svarstad,20 whereby 75% of patients on antidepressant treatment reported that pharmacists asked about their medication concerns. Nevertheless, it indicates that pharmacists’ counseling practices have expanded beyond the traditional medication-oriented approach, although clearly there still remains scope for improvement in patient-centered practice. In this regard, broad questions such as “Have you heard anything about the medication that may be of concern to you?” or “How are you feeling now?” were used by a few pharmacists in this study to elicit patients’ concerns about antidepressant treatment; however, such questions were not used often. In addition to eliciting patients’ concerns, these questions may also be useful in identifying adherence problems and in building concordant relationships with patients.

Most pharmacists in this study were able to identify important medication-related issues pertaining to antidepressant use, such as possible interactions with St John’s wort and the risk of withdrawal symptoms with abrupt discontinuation of antidepressants. In terms of treatment recommendations to address patients’ concerns, however, pharmacists tended to refer the patient back to the prescribing general practitioner. For example, although successful antidepressant treatment requires patients to continue treatment for at least 6 months after symptom remission,5 only three pharmacists in scenario 3 recommended that the patient continue treatment for that period. From the consultations, it is clear that provision of this advice was regarded as the jurisdiction of the physician, and most pharmacists appeared uncomfortable providing recommendations without adequate information about the patient’s medical history. While this may be appropriate, our study supports previous studies, whereby pharmacists report experiencing ethical dilemmas when addressing questions that crossed interprofessional boundaries.25 In fact, it has been suggested that pharmacists may experience role conflict if they perceived their primary role as being to reinforce the physician’s instructions rather than an advocacy role which takes into account patients’ needs and concerns about their treatment.25 From the current study, it appears that this is still a major challenge that needs to be addressed, because it may have implications for the pharmacist’s role in collaborative problem-solving and supporting patients in making treatment decisions. It also signifies the importance of integrating pharmacists into a multidisciplinary collaborative approach in order to provide truly effective care to patients with mental illness.35,36

The strength of this study is that we used audio recordings of pharmacist consultations to analyze directly the actual pharmacist responses in their practice settings, rather than their self-reported practice. This enabled a detailed examination of the content of counseling and therapeutic information discussed, with analyses tailored specifically to each scenario. However, the limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The small sample size limits the generalizability of its findings, and further research is needed to confirm the results of this exploratory study. In addition, pharmacists who agreed to participate may have been more confident about their communication and counseling skills. Also, the simulated patients used in this study may not necessarily reflect the patients typically seen in an average practice. For example, many patients with depression have chronic comorbid medical conditions and are often on complex treatment regimens.37 Both depression symptoms and the associated stigma may also present challenges for provider-patient communication.10 In addition, the study results reflect pharmacists’ consultations during single visits, and do not reflect pharmacist interactions with regular customers. Although we analyzed the type and amount of information gathered and provided, this study did not directly address the quality or clinical accuracy of information (for example, on side effects) given by the pharmacists.

Despite these limitations, this study has provided valuable insights into community pharmacists’ current practice when responding to antidepressant adherence-related issues at key stages of patients’ medication experience. In addition, previous studies have mainly used simulated patient methods to assess the provision of over-the-counter medications in community pharmacies; our study demonstrated the feasibility of using these methods to assess pharmacists’ counseling practices on prescription medications in a mental health context. In line with this, the use of simulated patient methods has also shown promise as an educational tool when used together with performance feedback and coaching of pharmacists immediately after simulated patient visits.38 This should be explored as a potential future strategy in improving pharmacists’ practice behaviors in depression care. Further research is also needed to assess the impact of pharmacists’ practice and communication behaviors on antidepressant medication adherence and clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Community pharmacists clearly have a potential role in supporting patients’ adherence to antidepressant medications throughout their treatment process. The majority of pharmacists in this study provided information on the risks and therapeutic benefits of antidepressant treatment, and were able to identify important medication-related issues, such as possible drug interactions. However, there remains scope for improvement in community pharmacists’ counseling practice, including providing and reinforcing key educational information, such as adherence-related messages, exploring patients’ medication concerns, and monitoring patients’ adherence to antidepressant medications. Further studies are needed to enhance community pharmacists’ roles in these areas, and to assess the impact of pharmacists’ practice on patient outcomes in depression care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the community pharmacists and simulated patients for their participation in this study. In addition, we thank Shervin Amirtabar for his assistance during the data collection process.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653–661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melf CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1128–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demyttenaere K. Risk factors and predictors of compliance in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13(Suppl 3):S69–S75. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(03)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:343–396. doi: 10.1177/0269881107088441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Depression: the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults 2009Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG90Accessed January 28, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995;33:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:164–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivero-Santana A, Perestelo-Perez L, Perez-Ramos J, Serrano-Aguilar P, De Las Cuevas C. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of compliance with antidepressants for depressive disorders: systematic review of observational studies. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:151–169. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S39382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bultman DC, Svarstad BL. Effects of physician communication style on client medication beliefs and adherence with antidepressant treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, et al. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA. 2002;288:1403–1409. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. How can you improve antidepressant adherence? J Fam Pract. 2007;56:356–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young HN, Bell RA, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Kravitz RL. Types of information physicians provide when prescribing antidepressants. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1172–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleath B, Rubin RH, Huston SA. Hispanic ethnicity, physician-patient communication, and antidepressant adherence. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garfield S, Francis S-A, Smith FJ. Building concordant relationships with patients starting antidepressant medication. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Geffen EC, Kruijtbosch M, Egberts ACG, Heerdink ER, van Hulten R. Patients’ perceptions of information received at the start of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor treatment: implications for community pharmacy. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:642–649. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson C, Roy T. Patient experiences of taking antidepressants for depression: a secondary qualitative analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012 Dec 3; doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.11.002. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubio-Valera M, Serrano-Blanco A, Magdalena-Belio J, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacist care in the improvement of adherence to antidepressants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:39–48. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen T. Effectiveness of interventions to improve antidepressant medication adherence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:954–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Jumah KA, Qureshi NA. Impact of pharmacist interventions on patients’ adherence to antidepressants and patient-reported outcomes: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:87–100. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S27436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bultman DC, Svarstad BL. Effects of pharmacist monitoring on patient satisfaction with antidepressant medication therapy. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42:36–43. doi: 10.1331/108658002763538053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah B, Chewning B. Conceptualizing and measuring pharmacist-patient communication: a review of published studies. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2006;2:153–185. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Oliveira DR, Shoemaker SJ. Achieving patient centeredness in pharmacy practice: openness and the pharmacist’s natural attitude. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2006;46:56–66. doi: 10.1331/154434506775268724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheerder G, De Coster I, Van Audenhove C. Pharmacists’ role in depression care: a survey of attitudes, current practices, and barriers. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1155–1160. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner DM, Murphy AL, Woodman AK, Connelly S. Community pharmacy services for antidepressant users. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landers M, Blenkinsopp A, Pollock K, Grime J. Community pharmacists and depression: the pharmacist as intermediary between patient and physician. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10:253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phokeo V, Sproule B, Raman-Wilms L. Community pharmacists’ attitudes toward and professional interactions with users of psychiatric medication. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1434–1436. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen T. Pharmacist-patient communication on use of antidepressants: a simulated patient study in community pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013 Jun 17; doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.05.006. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger K, Eickhoff C, Schulz M. Counselling quality in community pharmacies: implementation of the pseudo customer methodology in Germany. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grime J, Pollock K. Patients’ ambivalence about taking antidepressants: a qualitative study. Pharm J. 2003;271:516–519. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. “Medication career” or “moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Health care providers’ perspectives of medication adherence in the treatment of depression: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012 Nov 20; doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0625-3. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young HN, Dilworth TJ, Mott DA. Disparities in pharmacists’ patient education for Hispanics using antidepressants. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2011;51:388–396. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.09136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sleath B. Pharmacist-patient relationships: authoritarian, participatory, or default? Patient Educ Couns. 1996;28:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Multiple perspectives on shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:223–230. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.767225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gisev N, Bell JS, O’Reilly CL, Rosen A, Chen TF. An expert panel assessment of comprehensive medication reviews for clients of community mental health teams. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:1071–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, Chiao E, Gdovin JM. Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2497–2503. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mesquita AR, Lyra DP, Jr, Brito GC, Balisa-Rocha BJ, Aguiar PM, de Almeida Neto AC. Developing communication skills in pharmacy: a systematic review of the use of simulated patient methods. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]