Abstract

Colon cancer closely follows the paradigm of a single “gatekeeper gene.” Mutations inactivating the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene are found in ~80% of all human colon tumors, and heterozygosity for such mutations produces an autosomal dominant colon cancer predisposition in humans and in murine models. However, this tight association between a single genotype and phenotype belies a complex association of genetic and epigenetic factors that together generate the broad phenotypic spectrum of both familial and sporadic colon cancers. In this Chapter, we give a general overview of the structure, function, and outstanding issues concerning the role of Apc in human and experimental colon cancer. The availability of increasingly close models for human colon cancer in genetically tractable animal species enables the discovery and eventual molecular identification of genetic modifiers of the Apc-mutant phenotypes, connecting the central role of Apc in colon carcinogenesis to the myriad factors that ultimately determine the course of the disease.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Almost half of the population will develop at least one benign adenomatous colonic polyp during life, with less than 3% of those cases going on to develop colorectal cancer. Because symptoms are rare until very late stages, most cases go undetected. Colon cancer manifests itself as polypoid growths that progress to malignancy; metastases to the lymph nodes, liver, and lung are the primary cause of death in patients with advanced disease.

In the study of colon cancer, research is divided between sporadic and familial cases. Although hereditary colon cancer predispositions make up less than 5% of all colon cancer cases worldwide, the extensive pedigree information available in such cases has provided statistical power for isolating both the underlying causes and the genetic, environmental, and dietary modifiers of the phenotypes. The relationship of sporadic to familial colon cancer is highlighted by the successful use of therapeutics such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to treat both diseases.2 At present, a combination of chemotherapy, radiation treatment, and surgery is used to treat colon cancer. The 5-year survival expectation for colon cancer patients ranges from 93% for early stages to 8% in fully advanced stages.3

In this chapter, we will introduce and review the genetics and function of the central gatekeeper gene in colon cancer: Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC/Apc)a

Biology of the human intestine

The small intestine is composed of interdigitated villi and crypts of Lieberkühn (for a more in-depth discussion, see Sansom, this volume). The villi serve an absorptive function in the processing of food.4 The colon does not contain villi, but rather is composed of crypts, invaginated into a flat surface that is folded at various intervals called rugae. During human development, the adult intestine expands in part by a process of crypt fission, where entire crypts divide, producing daughter crypts.5,6 This process “purifies” crypts in that the early polyclonal crypts7 become monoclonal. Thus, each adult crypt lineage is limited to one somatic genotype. Crypt purification also occurs by stem cell succession, whereby a clone becomes dominant within the crypt. Analysis of methylation patterns in human crypts shows that stem cell succession continues over the life of an adult, as measured by random methylation changes that gradually become fixed in a crypt.8 An estimated 4–16 adult stem cells reside as a clonal cohort in a niche near the bottom of each crypt. As cells reach the top of the villus in the small intestine or the collar of the crypt in the colon, they undergo apoptosis and are shed into the intestinal lumen. Cells of crypts thus turn over at a high rate (every 3–5 days9) owing to the continual flow of newly produced cells up the crypt/villus axis (see Potten and Morris10 for a review of a classic body of work).

Intestinal epithelial stem cells can differentiate into a number of different cell types.11,12 Within colonic crypts lie goblet cells that secrete mucus; at the base of small intestinal crypts lie Paneth cells that provide defense and that help to maintain the gut flora. Enterocytes perform an absorptive function for nutrients crossing the epithelium and comprise up to 80% of the small intestine. Finally, rare enteroendocrine cells, comprising ~1% of the intestine, secrete hormones such as serotonin. Below the epithelial layer lies the lamina propria, which comprises the stromal connective and endothelial tissue that lends support and circulation to the epithelial cells. The muscularis mucosa lies immediately below the epithelial layer and separates it from the submucosa, which is composed of connective tissue. Below that is the muscularis externa, the muscle layer along which peristalsis moves food through the intestinal tract. Finally, the serosal layer marks the outermost edge of the intestine and is attached to the mesentery.

Development of human intestinal tumors

Intestinal tumors have been hypothesized to arise from the stem cells near the bottom of crypts, but other interpretations are possible, as discussed below. Accumulating evidence in various fields of cancer research supports the stem cell origin of tumors.13 Such research began with the study of hematopoietic stem cells, for which the genetics and quantitative biology had been well-established for several decades.14 It was noticed that the cells of hematopoietic malignancies exhibited similarities to multipotential hematopoietic precursors, particularly the ability to self-renew.15 Eventually, it was discovered that only a certain subpopulation of hematopoietic cancer cells are capable of transferring cancer to immunocompromised NOD/SCID mice.16 Recently, solid tumors have been investigated in a similar manner. For example, human breast cancers passaged serially through NOD/SCID mice show that a small number of cancer cells expressing a certain profile of surface markers are sufficient to initiate new tumors, whereas a large number of cancer cells with different profiles are not sufficient.17 Such “cancer stem cell” profiles have been shown for other cancer types including myeloma, brain, and prostate.18,19,20 Indeed recent studies have identified CD133 as a marker enriched in a self-renewing, tumor-initiating subpopulation of cells from human colonic tumors.21,22 Progress in the development of diagnostic cell markers will help to resolve the issue of whether the genetic event that initiates tumorigenesis necessarily occurs in stem cells proper or whether, alternatively, they can also occur in undifferentiated or dedifferentiated daughter cells.23

The issue of tumor progenitor cells has led to a debate about whether intestinal tumors form by a “bottom-up” process originating at the stem cell niche, or by a “top-down” process originating in cells in the inter-cryptal space at the top of the crypt/villus axis. Evidence for the “top-down” hypothesis comes from monocryptal human sporadic adenomas in which dysplasia is confined to the top half of the crypt, with normal-appearing cells more basally located in the crypt.24 The implication is that the dysplasia must have started at the top and grown down towards, rather than emerging from the stem cell niche. However, it is possible that the dysplasia originated in the middle of the crypt and expanded upwards. Thus, both the “bottom-up” and “top-down” models could be explained by an upwards expansion of stem cell derivatives25 from the middle of the crypt, or by the transformation of daughter stem cells to becoming tumor-competent. Clearly, the molecular identification of colon cancer stem cells is needed to determine the location of the cell of origin for particular intestinal tumors.

An early stage of colonic tumorigenesis is the benign adenoma that progresses to adenocarcinoma in situ - tumors that have developed high-grade dysplasia but are confined to the region above the submucosa. Progression to adenocarcinomas with invasion into or beyond the submucosa can be classified using different systems. The Dukes staging system (Dukes A, B, C, D, or E) is a measure of how far the invasive front of the cancer penetrates the intestinal wall.26 In the AJCC/TNM system, numbers identifying T (tumor), N (metastasis to the nodes), and M (metastasis to distant sites) provide a comprehensive view of tumor progression.27 For example, a T4N1M0 cancer indicates an adenocarcinoma that has invaded through the wall of the intestine and spread to 1–3 regional lymph nodes, but not yet to distant sites. Finally, the histological classification of polyps can be villous, tubulovillous, tubular, hyperplastic, or serrated. The rare villous adenoma class is believed to have the greatest potential for malignancy.28 Hyperplastic and serrated polyps have traditionally been viewed as benign; however, recent evidence points to a possible hyperplastic-serrated-adenocarcinoma progression sequence that involves somatic hyperactivation of the BRAF oncogene.29 The combination of these classification systems allows for a standardization of terminology among physicians. However, not all tumors fall into only one class, and even tumors in the same nominal class can behave differently between and within patients.

Discovery of APC mutations in human colon cancer

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) was first described as Gardner’s syndrome30 and included extracolonic manifestations such as osteomas and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE). Over time, it became clear that different classes of FAP existed with different symptoms, of which Gardner’s syndrome was only one. For example, “classical” FAP manifests as one hundred or more polyps in the colon, usually developing by twelve years of age, whereas patients with fewer than a hundred polyps are classified as attenuated FAP (AFAP). Many extracolonic symptoms further subdivide FAP.31

Linkage studies and the FAP-associated interstitial 5q Herrera deletion narrowed the genetic region underlying FAP to the 5q21 subchromosomal region (Fig.1).32,33 The APC gene was then linked to FAP concurrently by Kinzler et al.34, Nishisho et al35, Joslyn et al.36 and Groden et al.37 APC mutations were subsequently found in ~80% of sporadic colorectal tumors,38 confirming that Apc acts as a central gatekeeper protein in colorectal tumorigenesis. APC mutations and hypermethylation have also been found in various other cancer types, including pancreatic and gastric cancers.39,40

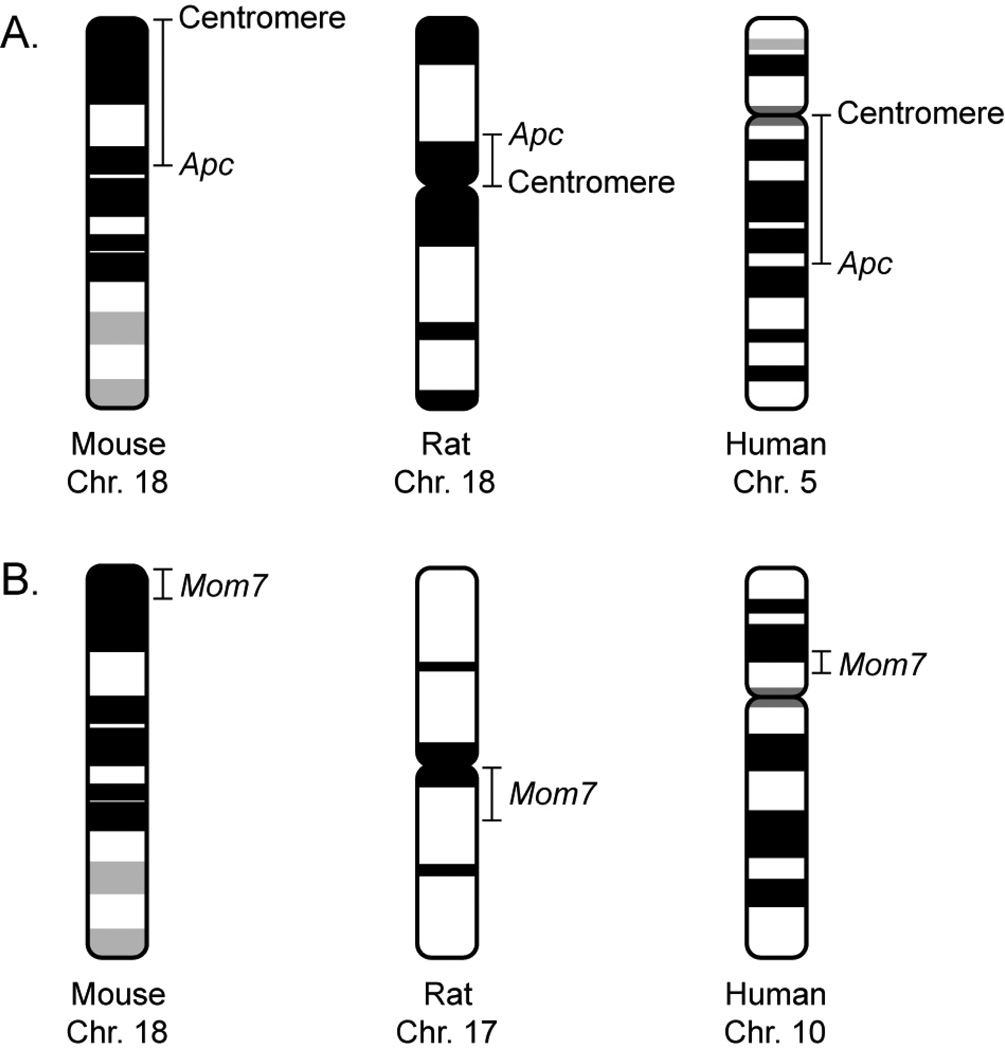

Figure 1. Organization of the mouse, rat, and human chromosomes bearing the APC/Apc and Mom7 orthologs.

A) The Apc locus of the mouse lies on a telocentric chromosome, in contrast to its orthologs in the rat and human, each of which lies on a metacentric chromosome. A metacentric character enables a facile discrimination between whole chromosome loss versus somatic recombination. B) The APC/Apc locus of the mouse is linked to the Mom7 locus on Chr 18, while the orthologs of these two loci are not linked in the rat and human karyotypes.

Function of Apc

Soon after the discovery of the Apc gene, the function of the gene product came under intense scrutiny. The crucial understanding of its function came concurrently from Su et al.41 and Rubinfeld et al.42 who identified the relationship between Apc and the regulation of β-catenin. We now know that the central lesions in both hereditary and sporadic colon tumors result in activation of the Wnt signaling pathway (see Kennell and Cadigan, this volume). In nearly all tumors, deactivating APC or GSK3β mutations or stabilizing CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin) mutations are present.43 More specifically, the canonical tumor suppressor function of Apc is to form a “destruction complex” with Axin/Axin2 and GSK-3β that promotes the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the oncogene β-catenin in the absence of Wnt signaling. Loss of Apc function results in an accumulation of β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus and engages the Tcf/Lef transcription factor complex to activate transcription of a large number of target genes including cyclinD1, c-myc, and CRD-BP.44 The tumorigenic consequences of unregulated β-catenin activity may be related to both the direct stimulation of cellular growth and proliferation, and to the disruption of differentiation programs.

In addition to its role in the Wnt signaling pathway, Apc also functions to promote microtubule stability in a number of cellular contexts. The impact of the disruption of this function on tumorigenesis is not well understood (see see Caldwell and Kaplan, Morrison, and Bahmanyar et al., this volume). However, it is worth noting that two groups have reported that stabilized β-catenin, expressed either from a conditionally activatable allele exposed to Cre or from a transgene, is sufficient to induce intestinal polyposis in mice,45,46 suggesting that loss of the microtubule-binding functions of Apc is not absolutely required for early tumor formation. Furthermore, as discussed below, mice homozygous for the 1638T Apc allele lacking the microtubule- and EB1-binding domains of Apc, but not the β-catenin binding domains, do not develop tumors. Despite these findings, an attractive speculation is that the disruption of microtubule functions contributes to tumor progression rather than to tumor initiation. Investigation of this idea awaits analysis of the progression stages of colonic neoplasia and the construction of mouse lines in which only the C-terminus of Apc can be conditionally deleted.

Structure of APC

The human APC gene spans 58kb, with a 15-exon coding region of 8529bp encoding a 2843 amino acid (aa), 310kD protein. Several exons exist 5’ of exon 1: 0.1, 0.2, 0.3,47 BS,48 and possibly more. The extent to which these isoforms play a role, if any, in colon cancer is unknown; many appear to be neuron-specific.49

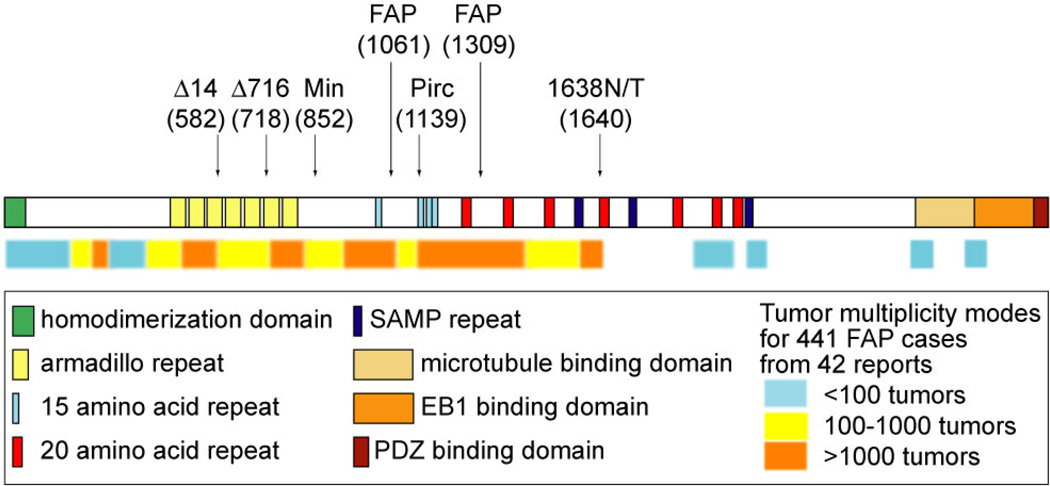

The canonical Apc transcript initiates at exon 1 and produces a protein with eight known functional sub-domains (Fig. 2). The majority of truncating mutations with severe phenotypes remove most of the β-catenin-binding “20 amino acid” (20aa) repeats (1256–2031aa).50 Interestingly, more C-terminal truncations that remove only the Axin-binding SAMP repeats (1568–2053aa),51 microtubule binding repeats (2220–2597aa),52 EB1-binding domain (2670–2843aa), and/or PDZ domain (the C-terminal 73aa that mediates anchoring to the cytoskeleton)53 generally have an attenuated phenotype. N-terminal truncations that apparently affect only the homodimerization domain (6–57aa), owing to bypass through the use of an internal translation restart site, likewise generally give attenuated phenotypes (see Fig 1).54 Mutations that truncate within the armadillo repeats (453–767aa) – which bind several proteins including Asef and KAP3, both involved with different aspects of cytoskeletal function55,56 – or within the β-catenin-binding “15 amino acid” (15aa) repeats (1021–1187aa) tend to be somewhat milder than the 20aa repeat truncations. An interesting molecular correlation in tumors was observed that may explain these findings: germline APC mutations in the mutation cluster region (MCR) spanning most of the 20aa repeats generally exhibit acquired loss of the wildtype allele, while APC mutations outside of this region generally exhibit acquired truncating mutations in the wildtype allele57. Several hypotheses have been put forth: the “just-right”58 and “loose fit”59 hypotheses, each of which proposes that an optimal number of 15aa repeats must remain after biallelic Apc inactivation to produce a severe FAP phenotype. These hypotheses remain to be rigorously tested.

Figure 2. The structure of the Apc protein.

Arrows indicate orthologous locations of mouse model mutations and the two most common FAP mutation sites. The color bar below indicates the genotype-phenotype correlation of sites of protein truncation to disease severity. The data used to generate the color bar can be found at http://www.mcardle.wisc.edu/dove/Data/Apc.htm.

Genotype-phenotype correlation in FAP

One difficulty in understanding the genotype-phenotype correlation is the current lack of a comprehensive public database of FAP patients. For research on mouse models, this lack of data makes it difficult to contextualize observations in terms of the human disease. So far, a literature search has found only one large-scale attempt to compile such information, although it presents only the results of the analysis and does not make the raw data available.60 Compounding this difficulty is that most reports on human cases do not count the multiplicity of tumors, but rather give only an estimate. Further difficulties come from differences in phenotype that may relate to whether the patient has received surgery or chemotherapeutics, and to the age of diagnosis. To address this gap temporarily, we have compiled data on 441 cases from 37 reports (see http://mcardle.oncology.wisc.edu/dove/Data/FAP.htm). We suggest that a curated public database be generated under the aegis of a society for gastroenterology, for easy access to vetted information of this sort.

These data lead to a conclusion different from that of Crabtree et al.,60 who claim that “mutations between codons 1020 and 1169 hav[e] the mildest disease” and that the most N-terminal truncations (i.e., prior to codon 248) do not lead to an attenuated phenotype. Instead, it seems that N-terminal truncations produce the mildest disease, although mutations between codons 1020 and 1169 tend to generate fewer tumors than mutations in the classic MCR (codons 1250–1450; cf. the “loose fit” hypothesis mentioned above, which predicts that MCR mutations leave behind a more optimal number of β-catenin-binding 15aa repeats). These discrepancies could be explained by geographic ancestry, as most of the patients of Crabtree et al. come only from the UK, whereas our compiled data are based on reports from around the world. In this regard, it is interesting to note the significant differences in presentation of colonic cancer in patients from the Middle East compared to those from the United States,61 possibly indicative of segregating modifier alleles (see below).

Biology of the murine intestine: an introduction to murine models of colon cancer

The mouse has long been used as a model for various human diseases, due to its experimental tractability and frequently significant reflection of the human phenotype. For colon cancer, mice readily form polyps after certain chemical treatments or genetic modifications, and have been an invaluable tool for drug and modifier locus discovery, among other benefits. In the following sections, we introduce numerous well-used mouse models, as well as a novel rat model. We also discuss other animal models involving Apc inactivation.

One caveat in using animal models is the deviation from human biology. The murine intestine – both mouse and rat – generally resembles that of the human in both development and structure, particularly in the formation of crypts and villi in the small intestine and in the crypt architecture of the colon. However, a few major differences exist: i) the murine colon and small intestine are intermingled within the peritoneum, rather than separated, ii) the rugae of the proximal murine colon have a diagonal rather than perpendicular pattern, and iii) the murine cecum is proportionately much larger. The extent to which these differences affect tumorigenesis is unknown, but must be taken into consideration when extrapolating from model animals to humans.

Mouse models of intestinal cancer

The first hereditary mouse model of colon cancer was described in 1990. Efficient ENU mutagenesis of the germline of C57BL/6J (B6) mice and subsequent outcrossing to AKR/J mice identified a phenodeviant with both a circling behavior and anemia.62 After continually backcrossing to B6, it was noted that the anemia trait segregated separately from the circling phenotype. Dissection of the anemic mice revealed multiple lesions throughout the intestinal tract, the majority in the small intestine. Histological preparations confirmed these lesions to be adenomas. This line of mice was therefore given the name Min (Multiple intestinal neoplasia). Su and colleagues63 used the link between Apc mutations and FAP to narrow the search for the gene underlying the Min phenotype. Sequencing of the Apc gene of Min mice revealed a single change – from leucine to an amber stop codon at position 850. This mutation segregated perfectly with the small intestinal phenotype of Min mice; the mutant allele was thus termed ApcMin. Min mice have since been extensively characterized in the literature and are currently the fourth best-selling line at the Jackson Laboratory. Its popularity can be attributed in part to several properties: i) Along with more recent targeted Apc mutants, Min is the only mouse cancer model with a single genetic change that produces a fully penetrant, organ-specific, consistent, and discrete tumor phenotype. ii) Adenomas in Min mice develop rapidly, with lesions visible as early as two months. Tumor multiplicities are on the order of 100 per intestinal tract, providing strong statistical power. iii) The multiple pathways impacting tumorigenesis enable many entry points for basic or applied study (see section below on modifiers).

Many other lines of mice with targeted genetic modifications of Apc have since been produced. Table 1 provides a summary of mice generated with these disruptions. When heterozygous, the Δ474, Δ14, Δ716, lacZ, and Δ1309 models all give phenotypes similar to that of Min64,65,66,67,68 In contrast, heterozygosity for the 1638N allele results in 0–2 tumors (none in the colon)69 while the 1638T model is tumor-free and, unlike any other truncating allele, is homozygous viable.70 Each of these two alleles truncates the protein at amino acid 1638; however, 1638N has only approximately 2% the transcript expression level of wild type Apc while 1638T has the full expression level. The latter observation implies that the C-terminus of Apc containing the direct microtubule and PDZ binding domains is nonessential, either for normal embryonic development or for preventing tumor initiation. However, it is important to note that the 1638T allele is not completely wildtype, since animals doubly heterozygous for 1638T and Min are embryonic lethal (as discussed by Sansom, this volume). Nonetheless, the two observations suggest that it is the reduction in Apc protein, not the codon 1638 truncation itself, which results in the 1638N tumor phenotypes. That a reduction in functional Apc protein levels leads to tumor initiation was confirmed by Li and colleagues,71 who inserted a neomycin cassette in either orientation (reverse, neoR, or forward, neoF, see Table 1) into the 13th intron of Apc to generate full-length hypomorphic alleles. These heterozygous mice developed fewer than two adenomas per mouse, with Apc protein levels and activity (as measured by β-catenin transcriptional activity) inversely correlating with tumor multiplicity. However, it is unclear whether the neomycin/hygromycin cassette in these insertion alleles of Fodde et al and Li et al exerts a regional position effect on a neighboring gene(s) that may also contribute to the phenotype.72 In this context, a clear demonstration of modification of the Min phenotype by a cis-linked recessive lethal factor has been provided in the analysis of the modifier locus Mom2.73

Table 1.

Apc mutant mouse lines

| Allele | Truncation codon | Conditional? | Genetic Background |

Intestinal Tumor # |

% of wt protein per allele |

Initial Reference of Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ468 | 468 (armadillo repeats) | Yes | N/Av | N/Av | N/Av | Gounari et al., 200574 |

| Δ474 | 474 (armadillo repeats) | No | B6 | >100 | 100 | Sasai et al., 200064 |

| Δ14 | 580 (armadillo repeats) | Yes | B6 | >100 | 100 | Colnot et al., 200465 |

| 580S | 580 (armadillo repeats) | Yes | Mixed | N/Av | N/Av | Shibata et al., 199775 |

| Δ716 | 716 (armadillo repeats) | No | B6 | >100 | 0* | Oshima et al., 1995149 |

| lacZ | 716 (armadillo repeats) | No | Mixed | >100 | 100 | Ishikawa et al., 2006150 |

| Min | 850 (armadillo repeats) | No | B6 | >100 | 100 | Moser et al., 199062 |

| Δ1309 | 1309 (15aa repeats) | No | B6 | 40 | 100 | Niho et al., 200368 |

| 1638N | 1638 (SAMP repeats) | No | B6 | 1 | 2 | Fodde et al., 199469 |

| 1638T | 1638 (SAMP repeats) | No | B6 | 0 | 100 | Smits et al., 199970 |

| Ex13 NeoR | full-length | No | B6 | 1 | 20 | Li et al., 200571 |

| Ex13 NeoF | full-length | No | B6 | 0.3 | 10 | Li et al., 200571 |

This is suggested, but not proven.71

N/Av = not available.

Recent advances in molecular cloning have enabled the construction of three independent conditional alleles of Apc in which specific exons are flanked by loxP sites (see Table 1): one allele that removes exon 11 upon the administration of Cre recombinase, resulting in truncation at codon 46874 and two alleles that remove exon 14, resulting in truncation at codon 580.65,75 The homozygous ablation of Apc in various organs has broadened the understanding of the known functions of Apc in maintaining homoeostasis in the liver, kidney, thymus, and intestine.76,77,74,78,79 Indeed, carcinomas are induced in the liver and kidney upon tissue-specific deletion of Apc. The ability to temporally control Apc loss, combined with a titration of Cre, opens up novel avenues for understanding the sufficiency of Apc loss for tumorigenesis. The recent finding that somatic c-Myc deletion abrogates the phenotype of concomitant Apc loss in the intestine confirms the power of such conditional alleles for pathway analysis.80

Finally, chemical carcinogens such as AOM81 and ENU82 have been shown to induce intestinal cancer in wild type mice, and have been used as models of colon cancer.eg. 83

Biology of mouse intestinal tumors

Tumors in the small intestine of the Min mouse are composed of dysplastic crypts surrounded and supported by hyperplastic villi and crypts, displaying a characteristic “rose” shape. By contrast, colonic tumors are peduncular, forming a spherical mass of dysplastic cells supported by a stromal stalk84 Tumors have a higher mitotic index than adjacent normal tissue,85 and crypt fission indices in Min intestines are also higher than in wild type.5 In contrast to the top-down/bottom-up controversy in human tumorigenesis,86,24 reviewed by Leedham and Wright,87 there is little controversy over the directionality of tumor development in the Min or Δ716 mouse models: tumors begin as an outpocketing in the crypt and the dysplastic cell population expands in both directions along the crypt-villus axis.84

Rat models of intestinal cancer

Wild type rats develop colon cancer at a very low incidence (<0.1%)88 with the exception of the Wistar-Furth/Osaka line that spontaneously develops adenocarcinomas at a rate of 30–40%.89 However, the genetic factors underlying this predisposition are unknown, and no recent studies have been reported. The majority of current rat models of colon cancer rely on the induction of tumors via treatment with the carcinogens AOM, DMH, or PhIP.90 The advantages of carcinogen-treated rat models are that tumors often progress to adenocarcinomas and that tumors have not been reported in the small intestine; the disadvantages are low polyp multiplicities (<2 in F344), long tumor latencies (>10 months), and laborious carcinogen administration regimens with the potential for inconsistent dosage. Carcinogen treatments have been required in the past, owing to the lack of rat embryonic stem cells required for generating genetically engineered rats. However, the ability to generate target-selected mutations, including nonsense alleles, has recently been implemented by several laboratories.91,92 This capacity has been drawn upon to generate a rat strain carrying a nonsense allele in codon 1137 of Apc. F344 rats heterozygous for this allele develop multiple intestinal neoplasms by three months of age, predominantly in the colon, and survive in the range of one year.93 The important colonic predisposition of tumorigenesis in this strain has led to its designation as Pirc: polyposis in the rat colon.

The size of the laboratory rat confers certain advantages to the Pirc model; for one, classical endoscopy can be used to monitor and biopsy colonic tumors.93 In addition, microCT and microPET imaging can strengthen the annotation of each of the tumors, whose sizes – often exceeding 1cm in diameter – greatly facilitate visualization and biopsy sampling. It can significantly enhance the molecular and morphological analysis of tumor progression to annotate individual neoplasms while keeping the animal alive. While these methods are also feasible in mouse models of colon cancer, the colonic predisposition, size, and longevity of the tumor-bearing Pirc rat can provide significant advantages in developing these experimental avenues. Thus, the rat’s promising utility for genetics combined with its size and feasibility for longitudinal studies of therapeutic regimes poises the Pirc kindred as a model for colon cancer that is complementary to the genetically powerful Min mouse model..

Coincidentally, the rat and mouse Apc loci each lie on Chromosome 18 of their respective genomes. The synteny over Chromosome (Chr) 18 is remarkably conserved between the mouse and the rat. The only difference in synteny is the most proximal 10Mb of the mouse chromosome, the homologous region of which is located on rat Chr 17. However, a more important difference between these two versions of Chr 18 is the placement of the centromere. Apc lies ~30Mb distal of the acrocentric mouse centromere but ~11Mb proximal of the metacentric rat centromere (Fig. 1). By contrast, in the metacentric human Chr 5, Apc is ~65Mb distal of the centromere.

Apc mutations in other organisms

To date, Apc mutants have been isolated in three other experimental organisms. The ApcMCR/+ zebrafish (Danio rerio) develops intestinal, hepatic, and pancreatic neoplasms, demonstrating the conservation of organ-specific gene functions between vertebrate phyla.94 Drosophila melanogaster lines heterozygous for mutations in either of the two Apc homologs, dApc1 or dApc2, develop with a completely normal phenotype despite the evolutionary conservation of Wnt signaling function.95 It is interesting to note in this context that dApc1 can complement the function of human Apc in suppressing β-catenin-mediated transcription in colon cancer cell lines.96 Finally, RNAi-induced reduction of Caenorhabditis elegans Apr-1, a gene homologous to the N-terminal half of human Apc, results in aberrations in blastomere development and endoderm specification.97 Recent studies have linked Wnt signaling and the regulation of WRM-1, a nematode homolog of β-catenin, to Apr-1 function during critical asymmetric cell divisions in development.98

Mechanisms of loss of heterozygosity at the Apc locus

Biallelic loss of Apc function appears to be required for tumorigenesis, but it remains open whether a heterozygous phenotype (also see below) is a necessary preliminary step to the complete loss of Apc function in tumors. In principle, loss of function of the wild type allele from the heterozygote can occur through any of several mechanisms, including: somatic recombination, non-disjunction with or without reduplication, coding or regulatory mutations, epigenetic silencing, or partial or full gene deletion. Early studies in Min mice demonstrated whole-chromosome loss of heterozygosity (LOH),99 narrowing the possibilities to somatic recombination or non-disjunction. However, the acrocentric nature of mouse chromosomes makes it difficult to distinguish between somatic recombination, which results in the homozygosis of all alleles distal to the recombination site, and mitotic non-disjunction, which results in the loss of an entire homolog. Unless the centromere can be marked, each of these processes gives identical results for acrocentric, but not for metacentric chromosomes. Subsequent studies in Min mice harboring an abnormal Robertsonian metacentric Chromosome 18,100 in Pirc rats with a naturally metacentric Chromosome 18 (Fig. 1),93 and in FAP patients with Apc truncations past codon 1286101 are consistent with somatic recombination; the majority of these intestinal tumors exhibit LOH limited to a single chromosome arm. Further, the genomes of the early mouse tumors appear to be stable, as assessed by FISH and karyotypic analysis.102 Somatic recombination has also been shown to be involved in LOH of other tumor suppressors in humans, such as the retinoblastoma gene Rb1.103,104

By contrast, analysis of sporadic rather than familial human colon tumors suggests that the loss event may occur via a karyotypically unstable pathway. For example, Thiagalingam and colleagues105 demonstrated that the observed single p-arm loss seen in 36% of tumors involved complex translocations rather than conservative somatic recombination. However, it is unclear whether the translocations were the cause of LOH, or instead were acquired during tumor progression. A study by Shih and colleagues,106 showed allelic imbalance across the genome by digital SNP analysis; however, this finding will require confirmation using more current technology such as Pyrosequencing.107 Another study has shown that 1638N tumors exhibit significant genomic copy number changes by comparative genomic hybridization;108 this highlights differences between the 1638N and the genomically stable Min models since the 1638N phenotype may be influenced by regional position effects from the neomycin cassette.72 In these investigations, another open issue is whether the earliest stage in tumorigenesis is being analyzed. Thus, the debate over the role of genomic instability in colorectal tumorigenesis remains divided into two hypotheses: that instability is a prerequisite for initiation and will be observed at the “birth” of the neoplasm, or that it is acquired during dysplastic growth along the neoplastic pathway and necessary only for progression.

Mathematical models have been invoked to support each hypothesis. Nowak and colleagues109 showed theoretically that chromosomal instability (CIN) can drive the majority of sporadic LOH events: a hypothesized efficient statistical “tunneling” effect of CIN could drive cells towards an equilibrated LOH population. By contrast, Komarova and Wodarz110 suggested that CIN would not be efficient, owing to the lag time required for the initial genomic hit to create CIN. Furthermore, Tomlinson and colleagues111 used an evolutionary approach to stem cell statistics to show that any instability associated with colonic tumors could be explained by a selective, exponential accumulation of aberrations, rather than by a pre-existing state of instability. Such mathematical models may prove to be valuable frameworks for the design of new quantitative experimental tests.

Are some Apc truncation peptides dominant negative?

Several lines of evidence suggest that certain truncated Apc proteins might act in a dominant negative manner, either by homodimerizing to wild type Apc or by competing for binding to β-catenin. For example, transfection of constructs encoding the N-terminal 750aa, 1309aa, 1450aa, or 1807aa of human Apc into colorectal cancer cell lines induced chromosome segregation dysfunctions, even in diploid cell lines.112,113 Another example is that endogenous N-terminal Apc fragments bind to exogenous C-terminal fragments, altering the former’s ability to bind to its partner Kap3.114 Thus, truncated Apc proteins could dominantly interfere with the function of the remaining allele’s product. Less direct lines of evidence come from analysis of normal tissue in Min mice. For example, differences have been observed between the intestines of Min and wild type mice in enterocyte migration,115 E-cadherin localization,116 and Egfr expression.117 It is not yet resolved whether these effects are autonomous to the heterozygous normal tissue, or are caused by a systemic effect of the tumors carried in the Min mouse.

By contrast, a line of mice transgenic for a Δ716 or Δ1287 fragment of the Apc gene failed to develop intestinal tumors.118 Here, it is unclear whether the transgene expression levels reached a tumorigenic threshold, especially in the presence of two copies of the wild type allele. The question of whether Min is dominant negative has important implications for the study of LOH. If normal heterozygous tissue from Min animals has a phenotype that predisposes to tumorigenesis, then the familial case may differ from the sporadic case, where normal tissue is homozygous wild type for Apc. A full understanding of Apc action must also account for the full-blown polyposis phenotype of locus-wide deletions including the classical Herrera deletion by which the APC locus was first mapped.33,119,120 It is also worth noting that similar C-terminal truncations of APC2 in Drosophila do not exhibit dominant negative effects on Wnt signaling or viability, but in some cases do have dominant effects on cytoskeletal organization in the embryo95. Thus, the question of predisposing haploinsufficiency or dominant negativity requires resolution.

Modifiers of murine intestinal cancer

Many different pathways have an impact on the initiation and/or progression of intestinal adenomas: karyotypic stability, DNA mutation rates, stem cell turnover, cellular growth and proliferation, cellular differentiation, environmental factors, diet, exercise, therapeutic drugs and others. In this chapter we address only genetic modifying factors (for a review of diet and therapeutic drugs, see reference 9390). In experimental genetics, a modifying locus has no phenotypic consequence in the absence of mutation at the primary locus of interest, in this case Apc. In epidemiology, however, the factors controlled by modifying loci may be found to have an impact, since the functional state of the primary locus may vary covertly or overtly in the population being studied.

The phenotypic variation of Min among different inbred strains highlights the importance of modifier alleles. Historically, B6-Min mice develop approximately 100 tumors in the intestinal tract. Other inbred backgrounds on which the ApcMin allele has been introgressed show a broad spectrum of tumor multiplicities (Table 2). For example, BTBR is a strongly enhancing background, with mice becoming moribund by 60 days of age due to the presence of more than 600 tumors.121 At the other extreme lie AKR mice, which develop only one to four tumors per animal and can survive for up to a year of age.122 C3H and 129S6 have milder suppressive phenotypes compared to AKR. General strain effects have led the way for the identification of polymorphic modifier loci by quantitative trait locus analysis of the phenotypes of Min carriers in outcrossed progeny.123

Table 2.

The genetic background dependence of the Min phenotype

| Strain | Mom1 | Age (days) |

Small Intestine |

Colon | N | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 129S6 | S/S | 103–163 | 45 | 1 | 23 | L.N. Kwong, unpublished |

| BTBR/Pas | S/S | 54–82 | 625 | 12 | 74 | Kwong et al., 2007121 |

| C3H/HeJ | S/S | 100–120 | 16 | 0.4 | 89 | Koratkar et al., 2004151 |

| C57BL/6J | S/S | 90–120 | 128 | 3 | 48 | Kwong et al., 2007121 |

| AKR/J | R/R | 146–336 | 4 | 0 | 42 | Kwong et al., 2007121 |

| 129 × B6 F1 | S/S | 92–164 | 82 | 0.2 | 35 | L.N. Kwong, unpublished |

| AKR × B6 F1 | R/S | 104–143 | 25 | 0.1 | 15 | Kwong et al., 2007121 |

| BTBR × B6 F1* | S/S | 80–93 | 117 | 1.6 | 16 | A. Shedlovsky, unpublished |

| BTBR × B6 F1** | S/S | 84–89 | 215 | 1.4 | 19 | A. Shedlovsky, unpublished |

| C3H × B6 F1 | R/S | 130–150 | 8 | 0 | 10 | Koratkar et al., 2004151 |

| CAST × B6 F1 | R/S | 100–120 | 3 | 0 | 14 | Koratkar et al., 2002152 |

| CAST × B6 F1 | R/S | 185–215 | 7 | 0 | 11 | Koratkar et al., 2002152 |

Min from B6 parent

Min from BTBR parent

Perhaps the most well-known modifier is Mom1 (Modifier of Min 1). A quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis using SSLP markers in crosses involving 4 inbred strains found a QTL on chromosome 4 that was shared among all mapping crosses.123 It was apparent that at least two alleles of Mom1 existed: a resistance allele found in AKR/J, MA/MyJ, and CAST/EiJ, and a sensitivity allele in C57B/6J (B6). Mom1 is semidominant where each copy affects tumor number by a factor of about 2. MacPhee and colleagues124 suggested that the Pla2g2a gene (encoding secretory phospholipase 2A) might explain the Mom1 effect. This hypothesis was confirmed in a line of B6 Min mice transgenic for a cosmid containing the resistance allele Pla2g2a,125 which showed reduced polyp number. Subsequent higher resolution genetic analysis showed that the Mom1 locus consists of both Pla2g2a and at least one other distal factor.126 The effect of Mom1 explains a significant proportion of the variance in tumor multiplicity seen in crosses between B6-Min and AKR or C3H mice (Table 2). Interestingly, the Pla2g2a gene seems to act in a cell non-autonomous fashion: it is expressed from post-mitotic Paneth and goblet cells within the micro-environment, affecting the net growth rate of adjacent tumors.85 (Evidence has been reported that the secretory phopholipase A2 can instead stimulate colonic tumor growth when expressed autonomously within the tumor lineage.127) The apparent non-autonomous action of Pla2g2a illustrates the necessity of investigations in the whole animal, as such effects would be lost in cell culture or non-orthotopic xenograft models.128 The exact mechanism by which Pla2g2a exerts its effects on colon tumorigenesis remains unresolved,129 highlighting the challenges of cancer modifier genetics. Furthermore, its relevance to the human disease is unresolved. Three studies have failed to find significant cancer-associated germline or somatic variation in the human PLA2G2A gene.130,131,132 One sporadic colon cancer patient has been reported with a constitutional frameshift mutation in this gene.133 Finally, a correlation has been reported between PLA2G2A expression and gastric adenocarcinoma patient survival.134 Overall, the identification of Mom1 has had a long-lasting impact on modifier genetics, as it was an important proof of principle that such studies could identify at the molecular level genetic determinants modifying a cancer phenotype.

By utilizing similar mapping methods, additional polymorphic Modifiers of Min have been discovered: Mom2, Mom3, and Mom7, each of which resides on Chromosome 18. Mom2 arose spontaneously in a stock of ApcMin/+ mice on the C57BL/6J background and mapped distal to the Apc locus.135 Congenic line, expression, and sequencing analyses pinpointed a recessive embryonic lethal 4bp duplication in the ATP synthase Atp5a1 gene.73 When in cis with the mutant Min allele, this mutant Mom2 allele confers an ~12-fold resistance to tumor multiplicity, but has no effect when in trans. Along with a decreased LOH incidence, these results indicated that somatic recombination proximal to both the Apc and Atp5a1 loci would generate homozygous Atp5a1 segregants that would be cell- and therefore tumor-lethal.

The Mom3 locus was discovered in a line of Min mice that had become strain-contaminated,136 resulting in an increase in tumor multiplicity compared to control B6-Min mice. It mapped to within the first 25cM of chromosome 18, proximal to Apc. However, the lack of additional polymorphic markers, along with the unknown contaminating strain background, prevented further positional refinement. In a separate study, the Mom7 locus mapped to a similar region as Mom3, but came from defined crosses of the B6.ApcMin/+ line to the AKR, BTBR, and A/J strains.121 Congenic line and in silico mapping analyses reduced the Mom7 interval to the first 4.4Mb of chromosome 18, including the complex sequence of the centromere. Unlike Mom2, Mom7 is homozygous viable for all alleles and the B6 allele shows a dominant resistance phenotype in both the trans and cis configurations. Whether Mom7 and Mom3 represent the same underlying modifier must be resolved by complementation testing. Interestingly, the Rb(7.18)9Lub Robertsonian translocation (Rb9), also at pericentromeric Chromosome 18, lowers tumor multiplicity in ApcMin/+ mice.100 FISH analysis showed that the Chromosome 18 homologs were mispaired in the nucleolar organizing region, leading to the hypothesis that the opportunity for somatic recombination at Apc is decreased by this centric fusion. Although Mom7 and Rb9 map to the same location, it is important to note that Rb9 involves a gross physical chromosome abnormality, while Mom7 involves a normal chromosome; furthermore they have qualitatively different effects, with Mom7 resistance fully dominant and Rb9 semidominant, making it unlikely that they represent the same modifier. Furthermore, none of these modifiers shows the “overdominant effect” predicted for sequence heterozygosity, which would suppress somatic recombination in heterozygotes but not in homozygotes.137 Thus, the Mom7 and Mom3 are modifiers distinct from Rb9.

As illustrated by the growing set of modifiers of the Min phenotype, it is clear from Table 3 that strategies for cancer prevention and therapy have many points of entry, providing both a wealth of candidate therapeutic targets and the challenge of converting any of them into potential human therapies. However, the benefit of such modifier studies extends beyond clinical relevance; each dataset informs both the functions of the modifier and of Apc. In turn, each modifier has a role in processes other than tumorigenesis. For example, the increases in both karyotypic instability and tumor multiplicity in BubR1+/−;ApcMin/+ mice provide insight into the normal checkpoint functions of both BubR1 and Apc.138 Another interesting example is that deletion of H19 induces the biallelic expression of Igf2, increasing Min tumor multiplicities.139 This genetic model of loss-of-imprinting (LOI) highlights the functional importance of genomic imprinting. In human sporadic colorectal cancer patients, LOI at Igf2 is often elevated in peripheral blood lymphocytes compared to healthy controls,140 implying that LOI can precede the loss of Apc function and become a risk factor for otherwise normal individuals.

Table 3.

Molecular genetic modifiers of Apc knockout mouse models

| Modifier affects | Modifier gene(s) |

Modifier allele(s) | Allele property |

Apc Model |

Effect of mutant allele on intestinal tumor multiplicity |

Factor of effect |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotypic stability | BubR1 | Bub1bGt(neo-btk)1Dai | Knockout (het) | Min | Decrease/Increasea | 2/10a | Rao et al., 2005138 |

| Cdx2 | Cdx2tm1Mmt | Knockout (het) | Δ716 | Decrease/Increasea | 9/6a | Aoki et al., 2003141 | |

| Terc | Terctm1Rdp | Knockout | Min | Decrease (at G4) | 10 | Rudolph et al., 2001153 | |

| DNA mutation rate | Pms2 | Pms2tm1Lisk | Knockout | Min | Increase | 3 | Baker et al., 1998154 |

| Mlh1 | Mlh1tm1Lisk | Knockout | Min | Increase | 3 | Shoemaker et al., 2000155 | |

| Msh2 | Msh2tm1Mak | Knockout | Min | Increase | 7 | Reitmair et al., 1996156 | |

| Msh3/ Msh6 |

Msh3tm1Rak Msh6tm1Rak |

Knockout | 1638N | Increase | 12 | Kuraguchi et al., 2001157 | |

| Fen1 | Fen1tm1Rak | Knockout (het) | 1638N | Increase | 1.5 | Kucherlapati et al., 2002158 | |

| Myh | Mutyhtm1Jhmi | Knockout | Min | Increase | 1.5 | Sieber et al., 2004159 | |

| Recombination rates | Rb9 | Rb(7.18)9Lub | Translocation | Min | Decrease | 19 | Haigis and Dove, 2003100 |

| Recql4 | Recql4tm1Glu | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Mann et al., 2005144 | |

| Blm | Blmtm3Brd | Hypomorph | Min | Increase | 3 | Luo et al., 2000143 | |

| Differentiation | EphB2 | ΔcyEphB2 | Dom neg Tg | Min | Decrease | 3 | Batlle et al., 2005147 |

| EphB3 | EphB3tm1Kln | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Batlle et al., 2005147 | |

| DNA methylation | Mbd2 | Mbd2tm1Bh | Knockout | Min | Decrease | 10 | Sansom et al., 2003145 |

| Mbd4 | Mbd4tm1Bird | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Millar et al., 2002146 | |

| Dnmt1 | Dnmt1tm1Jae | Knockout (het) | Min | Decrease | 2 | Cormier and Dove, 200085 | |

| Stromal regulation | Foxl1 | Foxl1tm1Khk | Knockout | Min | Increase | 8 | Perrault et al., 2005160 |

| TSP1 | Thbs1tm1Hyn | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Gutierrez et al., 2003161 | |

| Cell growth and proliferation | c-Jun | Juntm2.1Wag | Hypomorph | Min | Decrease | 2 | Nateri et al., 2005162 |

| Cyclin D1 | Ccnd1tm1Wbg | Knockout | Min | Decrease | 6 | Hulit et al., 2004163 | |

| Egfr | Egfrwa2 | Hypomorph | Min | Decrease | 10 | Roberts et al., 2002164 | |

| p21 | Cdkn1atm1Led | Knockout | 1638N | Increase | 2 | Yang et al., 2001165 | |

| p27 | Cdkn1btm1Mlf | Knockout | Min | Increase | 5 | Philippp-Staheli et al., 2002166 | |

| p53 | Trp53tm1Ldo | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Halberg et al., 2000167 | |

| Igf2 | H19tm1Tilg | Activates Ifg2 | Min | Increase | 2 | Sakatani et al., 2005139 | |

| Pleiotropic | Matrilysin | Mmp7tm1Lmm | Knockout | Min | Decrease | 2 | Wilson et al., 1997168 |

| Pla2g2a | Pla2g2aAKR | Tg | Min | Decrease | 2 | Cormier et al., 1997125 | |

| BAH | Asphtm1Jed | Knockout | Min | Increase | 2 | Dinchuk et al., 2002169 | |

| E-cadherin | Cdh1tm1Cbm | Knockout (het) | 1638N | Increase | 9 | Smits et al., 2000170 | |

| PPAR-δ | Ppardtm1Jps | Knockout | Min | Increase | 1.5 | Harman et al., 2004171 | |

| Netrin-1 | Tg-netrin-1 | Tg | 1638N | Enhances progression | N/A | Mazelin et al., 2004172 | |

| Smad4 | Smad4tm1Mmt | Knockout | Δ716 | Enhances progression | N/A | Takaku et al., 1999173 |

Effects on the small intestine and colon, respectively ;

The Robertsonian translocation is centromeric fusion of chromosomes 7 and 18.

Note: The Mom (Modifier of Min) and Scc (Susceptibility to colon cancer)174 loci are in general not yet fully defined in molecular detail (see text) and are therefore not included in Table 3.

Probing deeper into the modifiers organized in Table 3, several interesting patterns are noted. First, mutations in either of the mitotic stability genes BubR1138 or Cdx2141 generate a complex modifying phenotype, whereby the multiplicities of tumors of the small intestine decrease, while multiplicities of colonic tumors increase. This striking disparity between the effects of the same mutation in two different regions of the gut suggests that the small intestine and colon have different abilities to respond to CIN. Perhaps the small intestine expresses a senescence and/or apoptosis response that efficiently blocks CIN-induced tumor formation. By contrast, the hyper-recombination phenotypes of Blm142,143 or Reql144 mutations affect the entire intestinal tract.

The contrast between the regionally diverse response to mitotic instability and the uniform response to hyperrecombinational instability suggests that different responses to different types of instability exist in different regions of the intestinal tract. In the same vein, the Mbd2 and Mbd4 methyl-binding proteins have opposite effects on intestinal tumor multiplicity,145,146 indicating that the epigenetic machinery has both positive and negative indirect regulators of methylation-associated DNA mutation and/or silencing. Indeed, the potency of mutations in mismatch repair genes to generate tumors in the ascending colon illustrates both the centrality of sequence stability to tumor suppression and the regionality of these effects. Next, mutations in the ephrin family of genes147 demonstrate that differentiation is key to tumorigenesis, mirroring the dysregulation of ephrin receptors in mice conditionally inactivated for Apc.78 Finally, many “classic” regulators of numerous tumor pathways – including p53, p27, p21, c-Jun, and cyclin D1 – modify the Min phenotype, raising the possibility that therapies directed towards other classes of cancer could also have an effect on colonic tumors.

Conclusion

The complexity of both morphological and molecular pathways in colon cancer presents a challenge to clinical therapies, which are already multifaceted. For example, the FOLFOX regimen combines fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin, which can be used in addition to standard surgery and radiation treatments. Despite the complexity, the many different animal models now available –mouse, rat, zebrafish, and invertebrates – expand our ability to identify and validate different therapeutic targets. Indeed, the convenience of these animal models simplifies many aspects of colon cancer research that would otherwise be difficult to control from a highly heterogeneous human population. The effectiveness of such models emerged from the discovery of Apc as the central molecule negatively regulating colon cancer. This discovery, a result of Herculean efforts by several centers of human genetics33,34,37,148 allowed for both the identification of the molecular basis of the Min phenotype and the characterization and construction of single-gene mutants with profound cancer phenotypes. Overall, the study of colon cancer radiates out from our understanding of the mechanisms of action of the Apc protein, a central node regulating multiple cancer pathways.

Footnotes

APC and Apc are the designations for the human and murine genes, respectively; Apc is used herein for the function of the gene, regardless of species.

Reference List

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grosch S, Maier TJ, Schiffmann S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-Independent Anticarcinogenic Effects of Selective COX-2 Inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:736–747. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon Cancer Survival Rates With the New American Joint Committee on Cancer Sixth Edition Staging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1420–1425. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radtke F, Clevers H. Self-renewal and cancer of the gut: Two sides of a coin. Science. 2005;307:1904–1909. doi: 10.1126/science.1104815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasan HS, Park HS, Liu KC, et al. APC in the regulation of intestinal crypt fission. J Pathol. 1998;185:246–255. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199807)185:3<246::AID-PATH90>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greaves LC, Preston SL, Tadrous PJ, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations are established in human colonic stem cells, and mutated clones expand by crypt fission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:714–719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponder BAJ, Schmidt GH, Wilkinson MM, et al. Derivation of mouse intestinal crypts from single progenitor cells. Nature. 1985;313:689–691. doi: 10.1038/313689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KM, Shibata D. Methylation reveals a niche: stem cell succession in human colon crypts. Oncogene. 2002;21:5441–5449. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita Y, Cheung AT, Kieffer TJ. Harnessing the gut to treat diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5(Suppl 2):57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potten CS, Morris RJ. Epithelial stem cells in vivo. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1988;10:45–62. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1988.supplement_10.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat. 1974;141:537–562. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potten CS. Epithelial cell growth and differentiation. II. Intestinal apoptosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1997;273:G253–G257. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke MF, Fuller M. Stem sells and cancer: Two faces of Eve. Cell. 2006;124:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Till JE, Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA. The effect of plethora on growth and differentiation of normal hemopoietic colony-forming cells transplanted in mice of genotype W/Wv. Blood. 1967;29:102–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsui W, Huff CA, Wang Q, et al. Characterization of clonogenic multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2004;103:2332–2336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, et al. Prospective Identification of Tumorigenic Prostate Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, et al. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polyak K, Hahn WC. Roots and stems: stem cells in cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12:296–300. doi: 10.1038/nm1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih IM, Wang TL, Traverso G, et al. Top-down morphogenesis of colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051629398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KM, Calabrese P, Tavare S, et al. Enhanced stem cell survival in familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1369–1377. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63223-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood DA, Robbins GF, Zippin C, et al. Staging of cancer of the colon and cancer of the rectum. Cancer. 1979;43:961–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197903)43:3<961::aid-cncr2820430327>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gospodarowicz MK, Miller D, Groome PA, et al. The process for continuous improvement of the TNM classification. Cancer. 2004;100:1–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bond JH. Colon Polyps and Cancer. Endoscopy. 2003:27–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-36410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan TL, Zhao W, Cancer GP, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4878–4881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardner EJ. A genetic and clinical study of intestinal polyposis, a predisposing factor for carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Am J Hum Genet. 1951;3:167–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoemaker AR, Gould KA, Luongo C, et al. Studies of neoplasia in the Min mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:F25–F48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herrera L, Kakati S, Gibas L, et al. Brief clinical report: Gardner syndrome in a man with an interstitial deletion of 5q. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;25:473–476. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodmer WF, Bailey CJ, Bodmer J, et al. Localization of the gene for familial adenomatous polyposis on chromosome 5. Nature. 1987;328:614–616. doi: 10.1038/328614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su L-K, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, et al. Mutation of Chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science. 1991;253:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.1651563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joslyn G, Carlson M, Thliveris A, et al. Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus. Cell. 1991;66:601–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fearnhead NS, Britton MP, Bodmer WF. The ABC of APC. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:721–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horii A, Nakatsuru S, Miyoshi Y, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of the APC gene in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6696–6698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clement G, Bosman FT, Fontolliet C, et al. Monoallelic methylation of the APC promoter is altered in normal gastric mucosa associated with neoplastic lesions. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6867–6873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su LK, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Association of the APC tumor suppressor protein with catenins. Science. 1993;262:1734–1737. doi: 10.1126/science.8259519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, et al. Association of the APC gene product with β-catenin. Science. 1993;262:1731–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.8259518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fearnhead NS, Wilding JL, Bodmer WF. Genetics of colorectal cancer: hereditary aspects and overview of colorectal tumorigenesis. Br Med Bull. 2002;64:27–43. doi: 10.1093/bmb/64.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noubissi FK, Elcheva I, Bhatia N, et al. CRD-BP mediates stabilization of [beta]TrCP1 and c-myc mRNA in response to [beta]-catenin signalling. Nature. 2006;441:898–901. doi: 10.1038/nature04839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, et al. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romagnolo B, Berrebi D, Saadi-Keddoucci S, et al. Intestinal dysplasia and adenoma in transgenic mice after overexpression of an activated β-catenin. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3875–3879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Matsunami N, et al. Demonstration of promoter activity and alternative splicing in the region 5' to exon 1 of the APC gene. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2991–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bardos J, Sulekova Z, Ballhausen WG. Novel exon connections of the brain-specific (BS) exon of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:137–142. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<137::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pyles RB, Santoro IM, Groden J, et al. Novel protein isoforms of the APC tumor suppressor in neural tissue. Oncogene. 1998;16:77–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, et al. Binding of GSK3β to the APC-β-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996;272:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Behrens J, Jerchow BA, Wurtele M, et al. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with β-catenin, APC, and GSK3β. Science. 1998;280:596–599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zumbrunn J, Kinoshita K, Hyman AA, et al. Binding of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein to microtubules increases microtubule stability and is regulated by GSK3[beta] phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2001;11:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polakis P. The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:F127–F148. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heppner Goss K, Trzepacz C, Tuohy TM, et al. Attenuated APC alleles produce functional protein from internal translation initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8161–8166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112072199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jimbo T, Kawasaki Y, Koyama R, et al. Identification of a link between the tumour suppressor APC and the kinesin superfamily. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:323–327. doi: 10.1038/ncb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aoki K, Taketo MM. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC): a multi-functional tumor suppressor gene. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3327–3335. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rowan AJ, Lamlum H, Ilyas M, et al. APC mutations in sporadic colorectal tumors: A mutational "hotspot" and interdependence of the "two hits". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3352–3357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albuquerque C, Breukel C, van der LR, et al. The 'just-right' signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin signaling cascade. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1549–1560. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crabtree M, Sieber OM, Lipton L, et al. Refining the relation between 'first hits' and 'second hits' at the APC locus: the 'loose fit' model and evidence for differences in somatic mutation spectra among patients. Oncogene. 2003;22:4257–4265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crabtree MD, Tomlinson IPM, Hodgson SV, et al. Explaining variation in familial adenomatous polyposis: relationship between genotype and phenotype and evidence for modifier genes. Gut. 2002;51:420–423. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soliman AS, Bondy ML, El Badawy SA, et al. Contrasting molecular pathology of colorectal carcinoma in Egyptian and Western patients. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1037–1046. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sasai H, Masaki M, Wakitani K. Suppression of polypogenesis in a new mouse strain with a truncated Apc{Delta}474 by a novel COX-2 inhibitor, JTE-522. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:953–958. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colnot S, Niwa-Kawakita M, Hamard G, et al. Colorectal cancers in a new mouse model of familial adenomatous polyposis: influence of genetic and environmental modifiers. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oshima M, Oshima H, Kitagawa K, et al. Loss of Apc heterozygosity and abnormal tissue building in nascent intestinal polyps in mice carrying a truncated Apc gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4482–4486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ishikawa T, Tamai Y, Li Q, et al. Requirement for tumor suppressor Apc in the morphogenesis of anterior and ventral mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2003;253:230–246. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niho N, Takahashi M, Kitamura T, et al. Concomitant suppression of hyperlipidemia and intestinal polyp formation in Apc-deficient mice by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6090–6095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fodde R, Edelmann W, Yang K, et al. A targeted chain-termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8969–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smits R, Kielman MF, Breukel C, et al. Apc1638T: a mouse model delineating critical domains of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein involved in tumorigenesis and development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1309–1321. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Q, Ishikawa TO, Oshima M, et al. The threshold level of adenomatous polyposis coli protein for mouse intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8622–8627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haigis KM, Hoff PD, White A, et al. Tumor regionality in the mouse intestine reflects the mechanism of loss of Apc function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9769–9773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403338101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baran AA, Silverman KA, Zeskand J, et al. The modifier of Min 2 (Mom2) locus: embryonic lethality of a mutation in the Atp5a1 gene suggests a novel mechanism of polyp suppression. Genome Res. 2007;17:566–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.6089707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gounari F, Chang R, Cowan J, et al. Loss of adenomatous polyposis coli gene function disrupts thymic development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:800–809. doi: 10.1038/ni1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shibata H, Toyama K, Shioya H, et al. Rapid colorectal adenoma formation initiated by conditional targeting of the Apc gene. Science. 1997;278:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Colnot S, Decaens T, Niwa-Kawakita M, et al. Liver-targeted disruption of Apc in mice activates beta-catenin signaling and leads to hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17216–17221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404761101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sansom OJ, Griffiths DF, Reed KR, et al. Apc deficiency predisposes to renal carcinoma in the mouse. Oncogene. 2005;24:8205–8210. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sansom OJ, Reed KR, Hayes AJ, et al. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1385–1390. doi: 10.1101/gad.287404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Andreu P, Colnot S, Godard C, et al. Crypt-restricted proliferation and commitment to the Paneth cell lineage following Apc loss in the mouse intestine. Development. 2005;132:1443–1451. doi: 10.1242/dev.01700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sansom OJ, Meniel VS, Muncan V, et al. Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature. 2007;446:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature05674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bissahoyo A, Pearsall RS, Hanlon K, et al. Azoxymethane Is a Genetic Background-Dependent Colorectal Tumor Initiator and Promoter in Mice: Effects of Dose, Route, and Diet. Toxicol Sci. 2005 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shoemaker AR, Moser AR, Dove WF. N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea treatment of multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mice: age-related effects on the formation of intestinal adenomas, cystic crypts, and epidermoid cysts. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4479–4485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Biswas S, Chytil A, Washington K, et al. Transforming growth factor beta receptor type II inactivation promotes the establishment and progression of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4687–4692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oshima H, Oshima M, Kobayashi M, et al. Morphological and molecular processes of polyp formation in ApcΔ716 knockout mice. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1644–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cormier RT, Dove WF. Dnmt1N/+ reduces the net growth rate and multiplicity of intestinal adenomas in C57BL/6-Multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min)/+ mice independently of p53 but demonstrates strong synergy with the Modifier of Min 1AKR resistance allele. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3965–3970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Preston SL, Wong WM, Chan AO, et al. Bottom-up histogenesis of colorectal adenomas: origin in the monocryptal adenoma and initial expansion by crypt fission. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3819–3825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leedham S, Wright N. Expansion of a mutated clone - from stem cell to tumour. J Clin Pathol. 2007 doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.044610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goodman DG, Ward JM, Squire RA, et al. Neoplastic and Nonneoplastic Lesions in Aging Osborne - Mendel Rats. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1980;55:433–447. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(80)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miyamoto M, Takizawa S. Colon Carcinoma of Highly Inbred Rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:1471–1472. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.6.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Corpet DE, Pierre F. How good are rodent models of carcinogenesis in predicting efficacy in humans? A systematic review and meta-analysis of colon chemoprevention in rats, mice and men. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1911–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zan Y, Haag JD, Chen KS, et al. Production of knockout rats using ENU mutagenesis and a yeast-based screening assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:645–651. doi: 10.1038/nbt830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smits BM, Mudde JB, van de BJ, et al. Generation of gene knockouts and mutant models in the laboratory rat by ENU-driven target-selected mutagenesis. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:159–169. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000184960.82903.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Amos-Landgraf JM, Kwong LN, Kendziorski CM, et al. A target-selected Apc-mutant rat kindred enhances the modeling of familial human colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4036–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611690104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haramis AP, Hurlstone A, Van DV, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli-deficient zebrafish are susceptible to digestive tract neoplasia. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:444–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McCartney BM, Price MH, Webb RL, et al. Testing hypotheses for the functions of APC family proteins using null and truncation alleles in Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2407–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.02398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hamada F, Murata Y, Nishida A, et al. Identification and characterization of E-APC, a novel Drosophila homologue of the tumour suppressor APC. Genes to Cells. 1999;4:465–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rocheleau CE, Downs WD, Lin R, et al. Wnt Signaling and an APC-Related Gene Specify Endoderm in Early C. elegans Embryos. Cell. 1997;90:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mizumoto K, Sawa H. Cortical beta-catenin and APC regulate asymmetric nuclear beta-catenin localization during asymmetric cell division in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2007;12:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Luongo C, Moser AR, Gledhill S, et al. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haigis KM, Dove WF. A Robertsonian translocation suppresses a somatic recombination pathway to loss of heterozygosity. Nat Genet. 2003;33:33–39. doi: 10.1038/ng1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sieber OM, Heinimann K, Gorman P, et al. Analysis of chromosomal instability in human colorectal adenomas with two mutational hits at APC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16910–16915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012679099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Haigis KM, Caya JG, Reichelderfer M, et al. Intestinal adenomas can develop with a stable karyotype and stable microsatellites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8927–8931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132275099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cavenee WK, Dryja TP, Phillips RA, et al. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma. Nature. 1983;305:779–784. doi: 10.1038/305779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hagstrom SA, Dryja TP. Mitotic recombination map of 13cen-13q14 derived from an investigation of loss of heterozygosity in retinoblastomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2952–2957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thiagalingam S, Laken S, Willson JK, et al. Mechanisms underlying losses of heterozygosity in human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2698–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shih IM, Zhou W, Goodman SN, et al. Evidence that genetic instability occurs at an early stage of colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:818–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xinarianos G, McRonald FE, Risk JM, et al. Frequent genetic and epigenetic abnormalities contribute to the deregulation of cytoglobin in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2038–2044. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cardoso J, Molenaar L, de Menezes RX, et al. Chromosomal instability in MYH- and APC-mutant adenomatous polyps. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2514–2519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nowak MA, Komarova NL, Sengupta A, et al. The role of chromosomal instability in tumor initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16226–16231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202617399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]