Abstract

EVI1 is highly expressed in certain cytogenetic subsets of adult acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), and has been associated with inferior survival. We sought to examine the clinical and biological associations of EVI1high, defined as expression in excess of normal controls, in paediatric AML. EVI1 mRNA expression was measured via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in diagnostic specimens obtained from 206 patients. Expression levels were correlated with clinical features and outcome. EVI1high was present in 58/206 (28%) patients. MLL rearrangements occurred in 40% of EVI1high patients as opposed to 12% of the EVI1low/absent patients (p<0.001). No abnormalities of 3q26 were found in EVI1high patients by conventional cytogenetic analysis, nor were cryptic 3q26 abnormalities detected in a subset of patients screened by next-generation sequencing. French-American-British class M7 was enriched in the EVI1high group, accounting for 24% of these patients. EVI1high patients had significantly lower 5-year overall survival from study entry (51% vs. 68%, p=0.015). However, in multivariate analysis including other established prognostic markers, EVI1 expression did not retain independent prognostic significance. EVI1 expression is currently being studied in a larger cohort of patients enrolled on subsequent Children’s Oncology Group trials, to determine if EVI1high has prognostic value in MLL-rearranged or intermediate-risk subsets.

Keywords: cute myeloid leukaemia, paediatric cancer, MLL, EVI1

INTRODUCTION

Aberrant overexpression of specific genes is a common finding in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), and may define clinically relevant biological subsets that lack other cytogenetic or molecular prognostic markers (Mawad & Estey, 2012). The ectopic viral integration site-1 (EVI1) gene is a proto-oncogene subject to alternative splicing, and encodes a zinc finger protein that functions as a transcriptional regulator in early development (Hoyt et al, 1997). The gene was first identified as a common site of viral integration in retrovirus-induced murine leukaemia, suggesting a role for EVI1 in the transformation of haematopoietic cells (Morishita et al, 1988). Forced over-expression of EVI1 in haematopoietic progenitors was later shown to induce a myeloid differentiation block, also resulting in increased self-renewal and survival of these transformed progenitors (Laricchia-Robbio & Nucifora, 2008).

Although high EVI1 expression in adult AML is commonly found in association with rearrangements of 3q26 (Lugthart et al, 2008), the chromosomal location of the EVI1 gene, cytogenetic rearrangements involving this locus are rare in paediatric AML (Harrison et al, 2010). However, MLL translocations, a cytogenetic subgroup that accounts for approximately 16% of paediatric AML patients (Harrison et al, 2010), have also been reported to occur at high frequencies in patients with EVI1 overexpression (Lugthart et al, 2008; Balgobind et al, 2010). Chromosomal rearrangements involving MLL, a histone methyltransferase gene, frequently lead to deregulation of HOX genes and result in distinct aberrant methylation signatures (Bernt et al, 2011). Likewise, in addition to its role in transcriptional control, EVI1 has recently been implicated in epigenetic processes due to its interaction with both the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 (Cattaneo et al, 2008) and the DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B (Senyuk et al, 2011). Though the molecular mechanism for the association between MLL translocations and EVI1 expression has yet to be elucidated, it is possible that both of these events cooperate in epigenetic dysregulation, leading to myeloid leukaemia.

Overexpression of the EVI1 transcription factor, as determined by calibration against normal samples taken from healthy volunteers, has been reported in 7–10% of adult AML patient samples; further, high expression of any of the common EVI1 isoforms was found to predict significantly decreased survival in these adult AML studies (Lugthart et al, 2008; Groschel et al, 2010). In the single previous study of EVI1 expression in paediatric AML, investigators from several European cooperative groups reported that EVI1 overexpression was prognostic in univariate, but not multivariate, analysis (Balgobind et al, 2010). This study included paediatric patients enrolled on five different clinical trials, and defined EVI1 overexpression on the basis of gene expression profiling. In the present study, we examined the clinical and biological significance of EVI1 overexpression, as measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), in uniformly-treated paediatric AML patients enrolled on the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) pilot trial AAML03P1.

PATIENTS, MATERIALS, AND METHODS

Patient Samples

The COG pilot trial AAML03P1 tested the safety and efficacy of the addition of the calicheamicin-linked anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) to a five-cycle multi-agent chemotherapy backbone (Cooper et al, 2012). Newly diagnosed paediatric de novo AML patients enrolled in the COG-AAML03P1 trial were eligible for the present study. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia, constitutional trisomy 21, or antecedent myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were excluded. Morphological, flow cytometric, cytogenetic, and molecular analyses were performed according to study guidelines (Cooper et al, 2012). Analysis for cytogenetic abnormalities by an AML fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) panel and G-banding of metaphase chromosomes was performed on all patients at diagnosis, and results were available for all patients included in this study. Of the 340 eligible patients enrolled in AAML03P1 between December 2003 and November 2005, 206 patients (61%) had diagnostic specimens with adequate RNA quality available for expression analysis. Demographic, laboratory, and clinical characteristics of patients with vs. without specimens adequate for analysis were compared. Median diagnostic white blood cell (WBC) count (p=0.002) and median diagnostic marrow blast percentage (p=0.039) were both significantly higher in patients with samples analysed, as is common in retrospective studies utilizing cryopreserved specimens. FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) was also more common in patients with samples available for analysis (14% vs. 4%, p=0.035). There were no significant differences in age, race, or cytogenetic distribution between the two groups. Outcome measures were not significantly different between patients with and without specimens available for analysis.

This study was approved by the COG Myeloid Disease Biology Committee, and Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent for study protocol treatment and tissue sample evaluation was obtained from patients or their legal guardians.

Molecular Genotyping and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

The AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit and the QIAcube automated system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used to extract genetic material from cryopreserved diagnostic bone marrow specimens. Molecular genotyping for mutations in FLT3, NPM1 and CEBPA, was performed as previously described (Ho et al, 2011a).

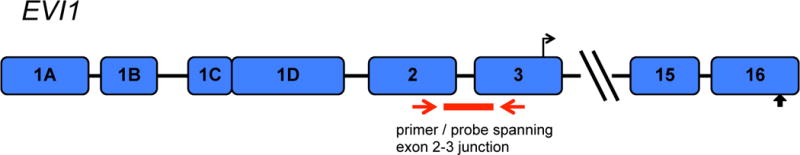

Reverse transcription was performed on 1 μg total diagnostic RNA per standard protocol (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). EVI1 mRNA expression was measured by performing qRT-PCR on cDNA transcripts on a StepOne Plus real-time PCR instrument, using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and TaqMan EVI1 Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with primer / probe set designed to hybridize within a region spanning exons 2 and 3 (Figure 1). These C-terminal exons are common to all of the known major splice isoforms of EVI1, including the four isoforms resulting from the alternate 5’ un-translated exons 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D, as well as the MDS1 and EVI1 complex (MECOM) fusion transcript resulting from intergenic splicing; thus this assay detects “total” EVI1 expression. Patient samples were tested in duplicate and the beta glucuronidase (GUSB) housekeeping gene was quantitated as an internal control. Samples with GUSB cycle time (Ct) >25 were excluded from further analysis. The comparative Ct method (Schmittgen & Livak, 2008) was used to determine EVI1 relative expression levels, normalized against pooled donor normal peripheral blood (PB) controls. EVI1 expression was reported as fold change PB.

Figure 1. Location of qRT-PCR primer / probe.

The primer / probe set utilized is designed to hybridize within a region spanning the exon 2–3 junction. These exons are common to all major splice isoforms resulting from alternate splicing of the first exon, as well as the MDS1 and EVI1 complex (MECOM) fusion transcript, which results from intergenic splicing.

Additionally, next-generation sequencing data from whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq; n=68) and whole genome sequencing (WGS; n=134) performed on COG paediatric AML patients as part of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) Initiative (www.target.cancer.gov) was examined for the presence of 3q26 alterations. RNA-Seq data was analysed by four different bioinformatic algorithms for the detection of cryptic fusion transcripts (deFuse [McPherson et al, 2011], TopHat-Fusion [Kim & Salzberg, 2011], FusionMap [Ge et al, 2011], and SnowShoes-FTD [Asmann et al, 2011]); WGS was performed by Complete Genomics, Inc. (CGI; Mountain View, CA) and cryptic fusions were determined by CGI proprietary algorithms.

Statistical Methods

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS) and disease-free survival (DFS). OS was defined as time from study entry to death from any cause. EFS was defined as the time from study entry to relapse or death. DFS was defined as time from course 1 for patients in complete remission (CR) to relapse or death. CR was defined as bone marrow aspirate containing <5% blasts by morphology and no evidence of extramedullary disease. The significance of predictor variables was tested with the log-rank statistic for OS and DFS. The significance of observed differences in proportions was tested by the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test when data were sparse. The Mann-Whitney test was used to determine the significance between differences in medians. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for univariate and multivariate analyses for OS and DFS. Statistical significance was defined as p-value less than 0.05.

RESULTS

EVI1 Expression and Correlation with Disease Characteristics

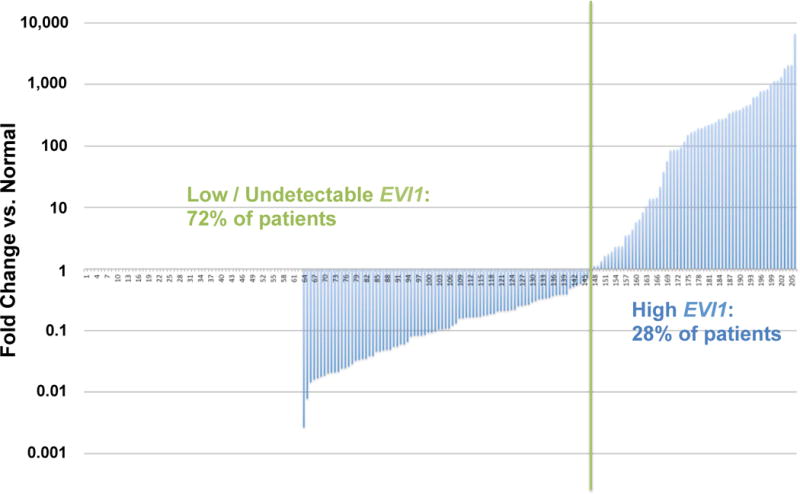

Diagnostic EVI1 expression levels varied widely across our study cohort of paediatric AML patients, (Figure 2). The majority of patients (148/206 patients, 72%) had either undetectable EVI1 expression, or EVI1 expression levels lower than normal PB controls. The remaining subset of patients (58/206 patients, 28%), with EVI1 >1.0-fold normal, were considered to have overexpression of EVI1 (EVI1high). Median EVI1 expression in the EVI1high group was 174.67-fold normal (range 1.13- to 6660.88-fold normal).

Figure 2. Distribution of EVI1 expression in 206 diagnostic pediatric AML specimens.

EVI1 expression ranged from 0 to 6660.88-fold normal. Overexpression of EVI1 was detected in 58/206 (28%) of patients. EVI1 expression is presented graphically on a logarithmic scale.

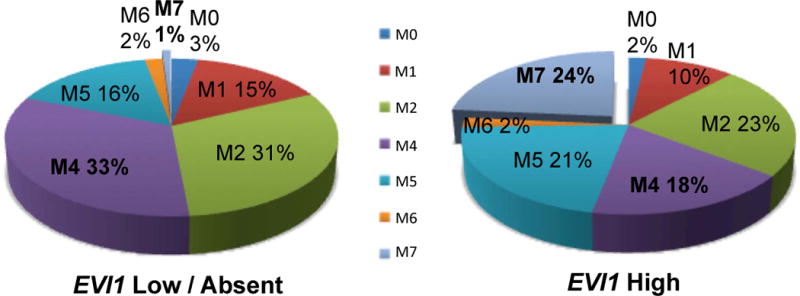

Diagnostic clinical and laboratory parameters were compared between EVI1high patients and the remainder of the study cohort (Table I). There was no difference in gender or racial distribution between the two groups. Infant patients (less than 1 year of age) accounted for 40% of the EVI1high group compared to 14% of remaining patients (p<0.001). Median diagnostic bone marrow blast percentage was similar among the 2 groups, but EVI1high patients had significantly lower median WBC counts at diagnosis (15.4 × 109/l vs. 35.0 × 109/l, p=0.021). French-American-British (FAB) class was non-randomly distributed between the two groups defined by EVI1 expression. FAB class M7 (acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia) was significantly more common in EVI1high patients, accounting for 24% of this group as opposed to 1% of the remaining patients (Figure 3, p<0.001), while FAB class M4 accounted for 18% of EVI1high patients vs. 33% of remaining patients (p=0.038). In terms of cytogenetic subgroups, EVI1high patients were significantly less likely to harbour either of the favourable-risk core binding factor (CBF) translocations (4% vs. 15% prevalence of t(8;21), p=0.030, and 0% vs. 21% prevalence of inv(16), p<0.001). Conversely, all cases of the high-risk monosomy 7 abnormality occurred in EVI1high patients, accounting for 8% of this group (p=0.006). Translocations involving the MLL gene on 11q23 were also enriched in the EVI1high cohort, occurring in 40% of patients vs. 12% of the remaining patients (p<0.001). Although EVI1 expression has been linked to 3q26 rearrangements in adult AML, no chromosome 3 abnormalities at the level of conventional cytogenetics were detected in EVI1high patients in our study.

TABLE I.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics by EVI1 expression status

| EVI1 0–1 (n=148) | EVI1 >1 (n=58) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | p-value |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 92 | 62% | 29 | 50% | 0.111 |

| Female | 56 | 38% | 29 | 50% | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (range) | 10.8 | (0.1 – 20.8) | 4.8 | (0.1 – 20.8) | 0.002 |

| 0–1 years | 21 | 14% | 23 | 40% | <0.001 |

| 2–10 years | 54 | 36% | 15 | 26% | 0.146 |

| 11–29 years | 73 | 49% | 20 | 34% | 0.054 |

| Race | |||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0% | 1 | 2% | 0.277 |

| Asian | 10 | 7% | 2 | 4% | 0.516 |

| Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 3 | 2% | 0 | 0% | 0.562 |

| Black or African American | 21 | 15% | 9 | 17% | 0.755 |

| White | 102 | 75% | 40 | 77% | 0.784 |

| Unknown | 12 | 6 | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 | 16% | 8 | 15% | 0.761 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 118 | 84% | 47 | 85% | |

| Unknown | 7 | 3 | |||

| WBC (x 109/l) – median (range) | 35 | (0.8 – 409) | 15.4 | (1.4 – 495) | 0.021 |

| Bone marrow blasts % | 70 | (5 – 100) | 70.5 | (2 – 100) | 0.615 |

| Platelet count (x 109/l)) – median (range) | 45.5 | (4 – 369) | 52.5 | (7 – 578) | 0.403 |

| Haemoglobin (g/l)– median (range) | 83 | (33 – 137) | 83 | (33 – 156) | 0.707 |

| Cytogenetics | |||||

| Normal | 34 | 25% | 9 | 17% | 0.257 |

| t(8;21) | 21 | 15% | 2 | 4% | 0.030 |

| inv(16) | 29 | 21% | 0 | 0% | <0.001 |

| 11q23 | 17 | 12% | 21 | 40% | <0.001 |

| t(6;9)(p23;q34) | 6 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0.189 |

| monosomy 7 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 8% | 0.006 |

| del(7q) | 3 | 2% | 0 | 0% | 0.562 |

| −5/5q- | 1 | 1% | 1 | 2% | 0.479 |

| 8 | 11 | 8% | 4 | 8% | 1.000 |

| Other | 16 | 12% | 12 | 23% | 0.053 |

| Unknown | 10 | 5 | |||

| FLT3-ITD status | |||||

| ITD + | 22 | 15% | 5 | 9% | 0.286 |

| ITD − | 124 | 85% | 49 | 91% | |

| Missing | 2 | 4 | |||

| CEBPA status | |||||

| CEBPA mutant | 10 | 7% | 1 | 2% | 0.293 |

| CEBPA wild type | 129 | 93% | 49 | 98% | |

| Missing | 9 | 8 | |||

| NPM1 status | |||||

| NPM1 mutant | 10 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 0.065 |

| NPM1 wild type | 111 | 92% | 49 | 100% | |

| Missing | 27 | 9 |

WBC, white blood cell count; ITD, internal tandem duplication

Figure 3. Distribution of FAB class in patients with low / undetectable EVI1 compared to patients with EVI1 overexpression.

French-American-British (FAB) class M7 was significantly over-represented in the EVI1high group, while FAB class M4 was significantly less common.

We next examined the relationship between diagnostic EVI1 expression and the presence of prognostic mutations (Table I; Meshinchi et al, 2006; Brown et al, 2007; Ho et al, 2009). FLT3-ITD mutations were present at similar frequencies in both the EVI1high and low / undetectable EVI1 groups. No EVI1high patients harboured the favourable-risk NPM1 mutation, and only a single EVI1high patient harboured a CEBPA mutation (biallelic). Complete cytogenetic and molecular profiles were available for 195 of the 206 patients included in this study. In recent COG AML trials, cytogenetic and molecular prognostic markers are combined to define the following risk groups: a) favourable-risk: patients without FLT3-ITD who presented with either a CBF translocation, NPM1 mutation, or CEBPA mutation; b) high-risk: patients with either FLT3-ITD with high mutant to wild-type allelic ratio (>0.4) or adverse cytogenetics (either monosomy 5, deletion of 5q, or monosomy 7); and c) intermediate-risk patients: all remaining patients not classified as either favourable-risk or high-risk. The prevalence of cytogenetic / molecular risk groups was non-randomly (p<0.001) distributed among the EVI1 expression groups. The majority (81%) of EVI1high patients belonged to the intermediate-risk group, lacking other cytogenetic or molecular prognostic markers. Favourable-risk patients accounted for only 4% of the EVI1high patients as compared to 48% of remaining patients.

Absence of 3q26 Rearrangements in Paediatric AML

In adult AML, overexpression of EVI1 is often associated with chromosomal abnormalities involving the 3q26 locus itself, most commonly inv(3)(q21q26) and t(3;3)(q21;q26) (Lugthart et al, 2008). These rearrangements are rare in paediatric AML. A recent study of cytogenetic abnormalities in childhood AML from the British Medical Research Council (MRC) reported 3q26 abnormalities in only 2 patients, out of 729 children with AML treated on MRC trials AML 10 and AML 12 (Harrison et al, 2010), and no 3q26 abnormalities were found in EVI1high patients in the single previous paediatric study of EVI1 expression (Balgobind et al, 2010). None of the EVI1high patients in our study harboured a 3q26 rearrangement at the level of conventional cytogenetics. However, novel cytogenetically cryptic 3q26 rearrangements have recently been described in adult AML in association with EVI1 overexpression (Lugthart et al, 2008; Haferlach et al, 2012).

As part of the NCI TARGET Initiative, a cohort of COG paediatric AML patient samples were subjected to either whole transcriptome (n=68) and/or whole genome sequencing (n=134); a proportionate subset of EVIhigh patients were represented in each group. Given the paucity of chromosome 3 abnormalities detected in paediatric AML detected by conventional methodologies, next-generation sequencing data was bioinformatically examined for fusion transcripts involving 3q26. No cryptic rearrangements involving the EVI1 locus at 3q26 were detectable in this childhood AML population by any of the 4 algorithms performed on RNA-Seq data (McPherson et al, 2011; Kim & Salzberg, 2011; Ge et al, 2011; Asmann et al, 2011), or by CGI proprietary algorithms performed on WGS data. In our study, 3q26 cytogenetic abnormalities were absent in paediatric AML.

MLL Translocation Partners

Rearrangements of the MLL gene on 11q23, with a variety of translocation partners, were detected in 40% of EVI1high patients (Table II). The most common MLL translocation in this group was t(9;11)(p22;q23), as is the case in unselected paediatric AML patients. The EVI1high group of patients also included all cases of t(11;19)(q23;p13) (n=3), t(2;11)(q35;q23) (n=1), and t(6;11)(q27;q23) (n=1). A large international retrospective study of MLL translocations in paediatric AML recently identified an association between t(6;11) and inferior survival outcome (Balgobind et al, 2009). No patient with t(1;11)(q21;q23), t(2;11)(q33;q23), t(10;11)(p11.2;q23), or t(X;11)(q13;q23) translocations had high expression of EVI1.

TABLE II.

MLL Translocation Partners by EVI1 Expression Status

| MLL Translocation Partner Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| High EVI1 | Low EVI1 | |

| t(1;11)(q21;q23) | 0 | 1 |

| t(2;11)(q33;q23) | 0 | 1 |

| t(2;11)(q35;q23) | 1 | 0 |

| t(6;11)(q27;q23) | 1 | 0 |

| t(9;11)(p22;q23) | 10 | 9 |

| t(10;11)(p11.2;q23) | 0 | 1 |

| t(10;11)(p12;q23) | 1 | 1 |

| t(11;17)(q23;q21) | 2 | 2 |

| t(11;19)(q23;p13) | 3 | 0 |

| t(X;11)(q13;q23) | 0 | 1 |

| del(11)(q23) | 1 | 0 |

| add(11)(q23) | 1 | 0 |

| 11q23 not otherwise specified | 1 | 1 |

Diagnostic EVI1 Expression and Clinical Outcome

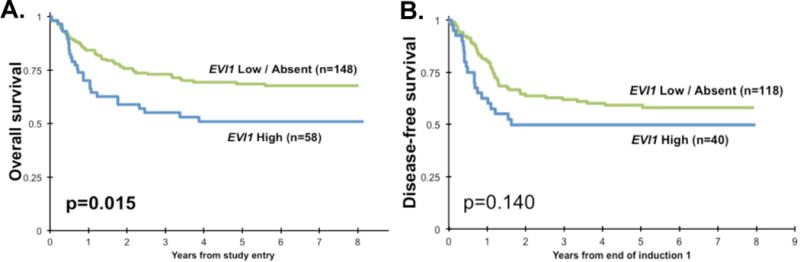

Response to therapy and survival outcomes were compared between EVI1high patients and patients with low / undetectable EVI1 (Figure 4). EVI1high patients had a CR rate of 73% after the first course of induction therapy, as compared to 82% for the remaining patients (p=0.151). Patients in the EVI1high cohort had significantly lower rates of 5-year OS (51 ± 14% vs. 68 ± 8%, p=0.015) and EFS (40 ± 13% vs. 52 ± 8%, p=0.042). For patients who achieved CR, 5-year DFS was 50 ± 16% for the EVI1high cohort vs. 59 ± 9% for the remaining patients, p=0.140. For the 99 intermediate-risk patients included in this study, 5-year OS was 50 ± 16% for EVI1high patients (n=44) vs. 63 ± 13% for the remaining patients (n=55, p=0.263).

Figure 4. Survival outcomes by EVI1 expression.

EVI1high patients had significantly worse (A) overall survival from study entry and (B) trended towards worse disease-free survival from complete remission.

Prognostic Effect of EVI1 Expression In Cytogenetic / Molecular Risk Groups

Cox regression analysis was then performed to evaluate the significance of EVI1 expression as a predictor of outcome in the context of established cytogenetic and molecular risk groups (favourable-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk, as defined above). Risk groups were used as a covariate for both univariate and multivariate models (Table III). In separate univariate models, favourable-risk group was a strong predictor of improved OS (HR for death from study enrollment compared to intermediate-risk group: 0.31, p<0.001) and improved DFS (HR for relapse or death from initial remission: 0.55, p=0.043); for high-risk group, HR was 1.72 for OS (p=0.065) and 1.72 for DFS (p=0.108). In a separate univariate model, high EVI1 expression was also a significant predictor of decreased OS (HR=1.79, p=0.016) but not DFS (HR=1.48, p=0.142). In a multivariate model including high EVI1 expression and the aforementioned risk groups, EVI1high did not retain independent prognostic significance for OS (HR for death from study enrollment: 1.17, p=0.554).

TABLE III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of high EVI1 expression and cytogenetic / molecular risk groups

| Univariate Cox Analyses | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS from study entry | DFS from end of course 1 | |||||||

| N | HR | 95% CI | p | N | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| EVI1 Expression | ||||||||

| Low / Absent EVI1 | 148 | 1 | 118 | 1 | ||||

| High EVI1 | 58 | 1.79 | 1.11 – 2.89 | 0.016 | 40 | 1.48 | 0.88 – 2.49 | 0.142 |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Standard | 99 | 1 | 70 | 1 | ||||

| Favourable | 70 | 0.31 | 0.16 – 0.59 | <0.001 | 59 | 0.55 | 0.31 – 0.98 | 0.043 |

| High | 26 | 1.72 | 0.97 – 3.07 | 0.065 | 19 | 1.72 | 0.89 – 3.35 | 0.108 |

| Multivariate Cox Analyses | ||||||||

| OS from study entry | DFS from end of course 1 | |||||||

| N | HR | 95% CI | p | N | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| EVI1 Expression | ||||||||

| Low / Absent EVI1 | 141 | 1 | 111 | 1 | ||||

| High EVI1 | 54 | 1.17 | 0.70 – 1.96 | 0.554 | 37 | 1.11 | 0.61 – 2.01 | 0.728 |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Standard | 99 | 1 | 70 | 1 | ||||

| Favourable | 70 | 0.33 | 0.16 – 0.65 | 0.002 | 59 | 0.58 | 0.31 – 1.08 | 0.087 |

| High | 26 | 1.76 | 0.99 – 3.14 | 0.056 | 19 | 1.76 | 0.91 – 3.44 | 0.096 |

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study presents an evaluation of the biological associations and clinical relevance of diagnostic EVI1 expression in paediatric AML patients uniformly treated on the COG pilot trial AAML03P1. EVI1 expression levels varied broadly in our study, but only 28% of patients had overexpression of this gene (in excess of normal controls). Even within the cohort of EVI1high patients, a wide range of expression was noted, although the magnitude of this variation is probably amplified by the use of normal tissue, in which the gene is expressed at low levels, as a reference control. Nonetheless, by using overexpression above normal as a threshold for determining high EVI1 expression, we were able to detect intriguing biological differences between EVI1high patients and the remaining patients with low or absent EVI1 expression.

The prevalence of EVI1 overexpression in our study was higher than the 6–10% reported in adult AML (Lugthart et al, 2008; Groschel et al, 2010); this age-dependent discrepancy is not surprising given the preponderance of MLL-rearranged infant patients in the EVI1Ihigh group. The prevalence of EVI1 overexpression in our study was also higher than the prevalence in the single prior paediatric report (Balgobind et al, 2010), although this may reflect a difference in definition. EVI1 over-expression was reported on the basis of gene expression profiling in the Balgobind study, whereas our study defined EVI1high as over-expression relative to normal on the basis of qRT-PCR. The majority (81%) of EVI1high patients in our trial belonged to the intermediate-risk group based on current cytogenetic / molecular risk stratification; only 2 patients with either favourable-risk CBF chromosomal abnormalities, and / or favourable-risk gene mutations, exhibited overexpression of EVI1. Monosomy 7, a rare high-risk cytogenetic abnormality in de novo pediatric AML, occurred in only 4 patients included in our study; all 4 monosomy 7 patients were found to have high EVI1 expression. Although FAB class is not incorporated into current risk-stratification schemes, EVI1 overexpression was also significantly associated with FAB class M7 unrelated to trisomy 21, which has been reported to confer adverse prognosis in paediatric AML (Barnard et al, 2007). High EVI1 expression was a significant predictor of inferior survival outcomes in univariate, but not multivariate, analysis in our study.

As advances in genomic technology improve our molecular understanding of AML, it is becoming increasingly clear that paediatric and adult forms of the disease are biologically distinct (Ho et al, 2011b). Overexpression of EVI1 in adult AML is frequently associated with, and presumed to directly result from, alterations of 3q26. We did not detect any chromosomal rearrangements of 3q26 in our paediatric AML patients, either at the level of conventional cytogenetics, or cryptically in our analysis of whole genome and transcriptome sequencing data. The mechanisms of EVI1 overexpression in paediatric AML appear to be distinct from EVI1 overexpression in the setting of chromosome 3 abnormalities in adult AML.

However, the deregulation of EVI1 function, as a result of EVI1 overexpression, may explain the association between EVI1high patients and certain clinical features common to both paediatric and adult AML. For example, EVI1 overexpression and resultant deregulation occurs in the setting of the adult AML “3q21q26 syndrome”. This syndrome of myelodysplasia and abnormal megakaryopoiesis in acute myeloblastic leukaemia with 3q26 rearrangements is highly associated with acquired monosomy 7, often in the setting of underlying or preceding MDS (Martinelli et al, 2003). It is possible that the paediatric EVI1high patients with monosomy 7 in our study had underlying MDS but were not diagnosed until after the transformation to AML. Further, the association with abnormal megakaryopoiesis may hint at one of the roles of EVI1 in haematopoiesis. In vitro overexpression of EVI1 in murine emybronic stem (ES) cells has been demonstrated to result in cell proliferation, clonogenicity, and differentiation shifted to enhance megakarypoiesis (Sitailo et al, 1999). Thus, it is not surprising that nearly all cases of acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (FAB class M7) had high EVI1 expression in our study.

Rearrangements of the MLL gene on 11q23 are present in 15–20% of de novo paediatric AML patients. MLL-rearrangements comprise a biologically and clinically heterogeneous group, as the MLL gene has over 50 known translocation partners (Balgobind et al, 2009). Thus, this cytogenetic group as a whole is considered intermediate-risk in the present COG risk-stratification scheme, although the recent large international study of 11q23-rearranged paediatric AML identified specific translocations with prognostic associations (Balgobind et al, 2009). Further, in a recent report of nearly 300 11q23-rearranged adult AML patients, overexpression of EVI1 identified a subset of high-risk patients with poor survival outcomes within the MLL-rearranged cytogenetic group (Groschel et al, 2013). Our present study is not powered to determine the prognostic relevance of EVI1 overexpression in paediatric AML with MLL translocations, or robust correlation between EVI1 expression and specific MLL translocation partners. A larger cohort of patients from the AAML03P1 successor Phase III trial, COG-AAML0531, is currently being evaluated for EVI1 expression. This should allow for analysis of outcome based on EVI1 expression in the 11q23-rearranged cohort, as well as expanded analysis of the significance of EVI1 expression in the cytogenetic / molecular intermediate-risk group. The identification of EVI1high patients at diagnosis may have therapeutic as well as prognostic relevance. High EVI1 expression has been recently linked to aberrant overexpression of CD52, a surface glycoprotein normally present on lymphocytes, which is the target of the monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Saito et al, 2011).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and families who consented to the use of biological specimens in this trial, and we thank the COG AML Reference Laboratory for providing diagnostic specimens. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R21 CA10262 (S.M.), R01 CA114563 (S.M.), and COG Chair’s Grant U10 CA98543, as well as the Mary Claire Satterly Foundation, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation (P.A.H.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P. A. H. performed research, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. T. A. A. and R. B. G performed statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. B. H. and S. C. R. performed cytogenetic analysis and edited the manuscript. J. A. P., T. C., and A. S. G. analysed data and edited the manuscript. S. M. designed research, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- Asmann YW, Hossain A, Necela BM, Middha S, Kalari KR, Sun Z, Chai HS, Williamson DW, Radisky D, Schroth GP, Kocher JP, Perez EA, Thompson EA. A novel bioinformatics pipeline for identification and characterization of fusion transcripts in breast cancer and normal cell lines. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:e100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgobind BV, Raimondi SC, Harbott J, Zimmermann M, Alonzo TA, Auvrignon A, Beverloo HB, Chang M, Creutzig U, Dworzak MN, Forestier E, Gibson B, Hasle H, Harrison CJ, Heerema NA, Kaspers GJ, Leszl A, Litvinko N, Nigro LL, Morimoto A, Perot C, Pieters R, Reinhardt D, Rubnitz JE, Smith FO, Stary J, Stasevich I, Strehl S, Taga T, Tomizawa D, Webb D, Zemanova Z, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Novel prognostic subgroups in childhood 11q23/MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia: results of an international retrospective study. Blood. 2009;114:2489–2496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgobind BV, Lugthart S, Hollink IH, Arentsen-Peters ST, van Wering ER, de Graaf SS, Reinhardt D, Creutzig U, Kaspers GJ, de Bont ES, Stary J, Trka J, Zimmermann M, Beverloo HB, Pieters R, Delwel R, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. EVI1 overexpression in distinct subtypes of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:942–949. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard DR, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Lange B, Woods WG. Comparison of childhood myelodysplastic syndrome, AML FAB M6 or M7, CCG 2891: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;49:17–22. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt KM, Armstrong SA. Targeting epigenetic programs in MLL-rearranged leukemias. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology. 2011;2011:354–360. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, McIntyre E, Rau R, Meshinchi S, Lacayo N, Dahl G, Alonzo TA, Chang M, Arceci RJ, Small D. The incidence and clinical significance of nucleophosmin mutations in childhood AML. Blood. 2007;110:979–985. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo F, Nucifora G. EVI1 recruits the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 for transcription repression. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2008;105:344–352. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TM, Franklin J, Gerbing RB, Alonzo TA, Hurwitz C, Raimondi SC, Hirsch B, Smith FO, Mathew P, Arceci RJ, Feusner J, Iannone R, Lavey RS, Meshinchi S, Gamis A. AAML03P1, a pilot study of the safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2012;118:761–769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Liu K, Juan T, Fang F, Newman M, Hoeck W. FusionMap: detecting fusion genes from next-generation sequencing data at base-pair resolution. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1922–1928. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröschel S, Lugthart S, Schlenk RF, Valk PJ, Eiwen K, Goudswaard C, van Putten WJ, Kayser S, Verdonck LF, Lübbert M, Ossenkoppele GJ, Germing U, Schmidt-Wolf I, Schlegelberger B, Krauter J, Ganser A, Döhner H, Löwenberg B, Döhner K, Delwel R. High EVI1 expression predicts outcome in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia and is associated with distinct cytogenetic abnormalities. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:2101–2107. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groschel S, Schlenk RF, Engelmann J, Rockova V, Teleanu V, Kühn MW, Eiwen K, Erpelinck C, Havermans M, Lübbert M, Germing U, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Beverloo HB, Schuurhuis GJ, Ossenkoppele GJ, Schlegelberger B, Verdonck LF, Vellenga E, Verhoef G, Vandenberghe P, Pabst T, Bargetzi M, Krauter J, Ganser A, Valk PJ, Löwenberg B, Döhner K, Döhner H, Delwel R. Deregulated Expression of EVI1 Defines a Poor Prognostic Subset of MLL-Rearranged Acute Myeloid Leukemias: A Study of the German-Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group and the Dutch-Belgian-Swiss HOVON/SAKK Cooperative Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:95–103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach C, Bacher U, Grossmann V, Schindela S, Zenger M, Kohlmann A, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Three novel cytogenetically cryptic EVI1 rearrangements associated with increased EVI1 expression and poor prognosis identified in 27 acute myeloid leukemia cases. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 2012;51:1079–1085. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CJ, HIlls RK, Moorman AV, Grimwade DJ, Hann I, Webb DK, Wheatley K, de Graaf SS, van den Berg E, Burnett AK, Gibson BE. Cytogenetics of childhood acute myeloid leukemia: United Kingdom Medical Research Council Treatment trials AML 10 and 12. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:2674–2681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PA, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Pollard J, Stirewalt DL, Hurwitz C, Heerema NA, Hirsch B, Raimondi SC, Lange B, Franklin JL, Radich JP, Meshinchi S. Prevalence and prognostic implications of CEBPA mutations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML): A report from the children’s oncology group. Blood. 2009;113:6558–6566. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PA, Kuhn J, Gerbing RB, Pollard JA, Zeng R, Miller KL, Heerema NA, Raimondi SC, Hirsch BA, Franklin JL, Lange B, Gamis AS, Alonzo TA, Meshinchi S. The WT1 synonymous SNP rs16754 correlates with higher mRNA expression and predicts significantly improved outcome in favorable-risk pediatric AML: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011a;29:704–711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PA, Kutny MA, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Joaquin J, Raimondi SC, Gamis AS, Meshinchi S. Leukemic mutations in the methylation-associated genes DNMT3A and IDH2 are rare events in pediatric AML: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2011b;57:204–209. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt PR, Bartholomew C, Davis AJ, Yutzey K, Garner LW, Potter SS, Ihle JN, Mucenski ML. The Evi1 proto-oncogene is required at midgestation for neural, heart, and paraxial mesenchyme development. Mechanisms of Development. 1997;65:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Salzberg SL. TopHat-Fusion: an algorithm for discovery of novel fusion transcripts. Genome Biology. 2011;12:R72. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laricchia-Robbio L, Nucifora G. Significant increase of self-renewal in hematopoietic cells after forced expression of EVI1. Blood Cells, Molecules, & Diseases. 2008;40:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugthart S, van Drunen E, van Norden Y, van Hoven A, Erpelinck CA, Valk PJ, Beverloo HB, Löwenberg B, Delwel R. High EVI1 levels predict adverse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence of EVI1 overexpression and chromosome 3q26 abnormalities underestimated. Blood. 2008;111:4329–4337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli G, Ottaviani E, Buonamici S, Isidori A, Borsaru G, Visani G, Piccaluga PP, Malagola M, Testoni N, Rondoni M, Nucifora G, Tura S, Baccarani M. Association of 3q21q26 syndrome with different RPN1/EVI1 fusion transcripts. Haematologica. 2003;88:1221–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawad R, Estey EH. Acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Current Oncology Reports. 2012;14:359–368. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A, Hormozdiari F, Zayed A, Giuliany R, Ha G, Sun MG, Griffith M, Heravi Moussavi A, Senz J, Melnyk N, Pacheco M, Marra MA, Hirst M, Nielsen TO, Sahinalp SC, Huntsman D, Shah SP. deFuse: an algorithm for gene fusion discovery in tumor RNA-Seq data. Public Library of Science Computational Biology. 2011;7:e1001138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K, Parker DS, Mucenski ML, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Ihle JN. Retroviral activation of a novel gene encoding a zinc finger protein in IL-3-dependent myeloid leukemia cell lines. Cell. 1988;54:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshinchi S, Alonzo TA, Stirewalt DL, Zwaan M, Zimmerman M, Reinhardt D, Kaspers GJ, Heerema NA, Gerbing R, Lange BJ, Radich JP. Clinical implications of FLT3 mutations in pediatric AML. Blood. 2006;108:3654–3661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Nakahata S, Yamakawa N, Kaneda K, Ichihara E, Suekane A, Morishita K. CD52 as a molecular target for immunotherapy to treat acute myeloid leukemia with high EVI1 expression. Leukemia. 2011;25:921–931. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senyuk V, Premanand K, Xu P, Qian Z, Nucifora G. The oncoprotein EVI1 and the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3 co-operate in binding and de novo methylation of target DNA. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitailo S, Sood R, Barton K, Nucifora G. Forced expression of the leukemia-associated gene EVI1 in ES cells: a model for myeloid leukemia with 3q26 rearrangements. Leukemia. 1999;13:1639–1645. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]