Abstract

Objective

To compare the effects, safety, and cost effectiveness of antenatal screening strategies for Down's syndrome.

Design

Analysis of incremental cost effectiveness.

Setting

United Kingdom.

Main outcome measures

Number of liveborn babies with Down's syndrome, miscarriages due to chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, healthcare costs of screening programme, and additional costs and additional miscarriages per additional affected live birth prevented by adopting a more effective strategy.

Results

Compared with no screening, the additional cost per additional liveborn baby with Down's syndrome prevented was £22 000 for measurement of nuchal translucency. The cost of the integrated test was £51 000 compared with measurement of nuchal translucency. All other strategies were more costly and less effective, or cost more per additional affected baby prevented. Depending on the cost of the screening test, the first trimester combined test and the quadruple test would also be cost effective options.

Conclusions

The choice of screening strategy should be between the integrated test, first trimester combined test, quadruple test, or nuchal translucency measurement depending on how much service providers are willing to pay, the total budget available, and values on safety. Screening based on maternal age, the second trimester double test, and the first trimester serum test was less effective, less safe, and more costly than these four options.

What is already known on this topic

Screening strategies that combine nuchal translucency measurement with serum testing perform better than either of these tests used alone

Serum testing in the second trimester using the triple test is cost effective compared with screening based on maternal age

What this study adds

The integrated test is the most effective, safest, and most expensive strategy

The choice of screening strategy should be between the integrated test, first trimester combined test, quadruple test, or measurement of nuchal translucency

Screening based on maternal age, the second trimester double test, and the first trimester serum test is less effective, less safe, and more costly than the above options

Introduction

The provision of screening services in the NHS lags far behind advances in performance of screening tests over the past decade.1 In 1998, 57% of antenatal care providers offered the second trimester double test for Down's syndrome and 8% offered screening based only on maternal age.2 Few NHS providers offered the more effective nuchal translucency measurement (7%) or quadruple test (3%). The integrated test, which is the most effective screening test and involves testing in the first and second trimesters,3 is available only privately.

The main considerations for providers of screening for Down's syndrome should be minimising the risk of babies with Down's syndrome being missed by the test, reducing miscarriage due to amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling, and costs. We therefore compared the effects, safety, and cost effectiveness of nine strategies currently available for screening for Down's syndrome in the United Kingdom.

Methods

Decision model

We compared no screening with nine screening strategies offered in the first or second trimesters (table 1). Prenatal diagnosis included abdominal chorionic villus sampling before 15 weeks' gestation or amniocentesis thereafter if screening indicated a greater than 1 in 300 risk of Down's syndrome. We determined the number of liveborn children with and without Down's syndrome, pregnancy losses (including terminations, spontaneous losses, and miscarriages due to chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis), and the healthcare cost of the screening programme in 10 000 women with the age distribution of women delivering in England and Wales in 1995.

Table 1.

Detection rate and estimated uptake, process time, and cost of screening strategies for Down's syndrome

| Procedure | Detection rate | Reported rate | Uptake | Process time* (weeks) | Unit cost† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First trimester screening (10 to 14 weeks)‡: | |||||

| Maternal age | 32%§ | 80% | 0 | £0 | |

| Nuchal translucency measurement | 74%§ | 73%4 | 80% | 0 | £4.40 |

| First trimester double test (PAPP-A, HCG) | 63%§ | 62%5 | 80% | 1 | £11 |

| First trimester combined test (nuchal translucency, PAPP-A, HCG) | 86%§ | 80% 3 85% 6 | 80% | 1 | £15 |

| Second trimester screening (15 to 19 weeks)‡: | |||||

| Maternal age | 32%§ | 80% | 0 | ||

| Second trimester double test (AFP, HCG) | 60%§ | 58%,7 59%3 | 80% | 1 | £10 |

| Triple test (AFP, HCG, uE3) | 68%§ | 67%,8 69%3 | 80% | 1 | £11 |

| Quadruple test (AFP, HCG, uE3, inhibin A) | 79%§ | 76%,3 79%9 | 80% | 1 | £13 |

| Integrated test (first trimester: nuchal translucency, PAPP-A; second trimester: quadruple test) | 95%§ | 94%3 | 80% | 1 | £22 |

| Prenatal diagnosis: | |||||

| Amniocentesis (⩾15 weeks) | 100% | 100%1 | 80% unaffected, 90% affected | 2 (+1)¶** | £208 |

| Chorionic villus sampling (11-14 weeks)‡ | 100% | 100%1 | 0 (+1)¶** | £249 | |

| Termination | |||||

| Surgical dilatation, evacuation (11 to 13 weeks)‡ | 90% | 1¶ | £495 | ||

| Medical with mifepristone (⩾14 weeks) | 90% | 1¶ | £495 | ||

AFP=α fetoprotein, HCG=β human chorionic gonadotrophin, PAPP-A=pregnancy associated plasma protein A, uE3=unconjugated oestriol.

Time between procedure and date results given to the woman.

For details of derivation see technical report.

Refers to completed weeks.

Detection rate for a 5% false positive rate.

1 week allowed before procedure for administration and counselling.

Culture of amniotic fluid takes 2 weeks, preparation of chorionic villus sample takes 2 days.

Model estimates

Estimates used in the model are based on a systematic review,1 other published sources, and discussions with a reference group of UK service providers and users (see acknowledgements). We assumed that 100% of women attend antenatal clinic between 10 and 14 completed weeks of gestation (median 12 weeks gestation) and are offered tests in the first trimester or between 15 and 19 weeks (median 15 weeks) for tests in the second trimester. Table 1 gives the time required for counselling and for processing of screening and diagnostic tests and the proportion of women accepting procedures.

Based on the age specific prevalence of pregnancies affected by Down's syndrome at 10 and 16 weeks' gestation and at term,6,10 we took account of the weekly risk of spontaneous fetal loss in affected and unaffected pregnancies. Overall, we estimated that 45% of affected fetuses would be spontaneously lost between 10 weeks' gestation and term. The test characteristics for nuchal translucency measurements were derived from a study of 326 affected fetuses and 95 476 unaffected fetuses,4,11 adjusted for verification bias due to termination of affected fetuses who would otherwise have been spontaneously lost.4

The test characteristics for all serum tests were derived from the analysis of stored serum samples from 77 women with affected pregnancies and 385 with unaffected pregnancies, all of whom had amniocentesis.6 We selected combinations of serum analytes that, according to the systematic review,6 performed best. Alternative combinations of analytes—for example, substitution of free β human chorionic gonadotrophin for total human chorionic gonadotrophin or inhibin A for unconjugated oestriol, would not substantially affect test performance. We assumed that all women would have an ultrasound dating scan and that, for second trimester serum tests, maternal weight would be taken into account.

We estimated the risk of giving birth to a Down's syndrome baby for each woman, based on the screening test results and maternal age. Firstly, we calculated the distribution of likelihood ratios for the screening test separately for pregnancies affected and unaffected by Down's syndrome using Monte Carlo simulation12 and assumed independence between the nuchal translucency measurement, first trimester serum test (PAPP-A), and quadruple test. We then calculated the distributions of risk of an affected pregnancy for each year of maternal age by multiplying likelihood ratios by the age specific risk of an affected live birth. Finally, we calculated a single, age specific distribution of risk after screening by taking account of the proportion of pregnant women at each maternal age and the age specific risk of Down's syndrome.

Cost

The costs of screening tests included laboratory expenses (consumables and staff), informing the women of the results (by telephone if positive, by post if negative), service costs (including processing results and monitoring the service), overheads, and (for nuchal translucency measurement) training (table 1). The costs of chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis included counselling before the procedure, equipment and staff to do the procedure, laboratory expenses (consumables and staff, non-reagent and labour costs), and overheads. For all these costs, we assumed an existing infrastructure for antenatal screening and diagnosis of Down's syndrome. We also estimated costs of events arising from screening (table 2) All costs were adjusted to June 1998 prices (for full details see www.ich.ucl.ac.uk/srtu).

Table 2.

Risk and costs of events after screening for Down's syndrome

| Event | Risk | Reported range | Unit cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miscarriage due to the procedure | |||

| Amniocentesis | 0.9% | 0.0 to 1.9%1 | £408 |

| Chorionic villus sampling | 0.9% | −2.2% to 2.0%*1 | £408 |

| Sample failure and repeat procedure in all | |||

| Amniocentesis | 0.8% | 0.5 to 1.0%1 | £181 |

| Chorionic villus sampling | 1.3% | 1.0 to 1.6%1 | £181 |

| Spontaneous loss in unaffected pregnancies (10 weeks to term)† | 2.1% | £408 | |

| Spontaneous loss in Down's syndrome pregnancies (10 weeks to term)† | 45% | £408 | |

| Live birth | £597 | ||

Difference compared with second trimester amniocentesis.

Costs incurred because dilatation and evacuation assumed for all losses.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses examined the effect of a 50% increase and decrease in the costs of chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis, the screening test, and nuchal translucency measurement. We also tested the effect of varying the cut-off point for a positive result.

Results

Effects and costs

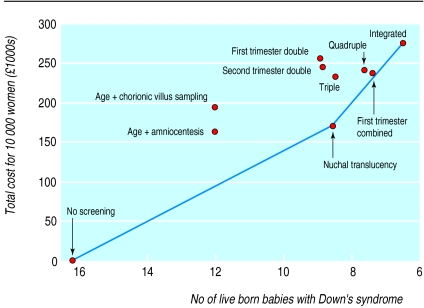

Table 3 and the figure show the effects and costs of no screening and of the nine screening strategies. Measurement of nuchal translucency would result in 7.6 fewer births of babies with Down's syndrome compared with no antenatal screening, at a total cost of £171 000 per 10 000 pregnant women. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio for nuchal translucency compared with no screening is £22 000 (171 000/7.6) per prevented birth of a baby with Down's syndrome. The integrated test results in 2.0 fewer births of babies with Down's syndrome than the nuchal translucency measurement at a total cost of £276 000. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio of the integrated test compared with nuchal translucency is £52 000 (276 000−171 000)/2.0) per affected baby prevented.

Table 3.

Number of live births affected by Down's syndrome, miscarriages due to chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, and total costs per 10 000 pregnancies and incremental cost effectiveness ratios assuming risk of 1 in 300 as cut-off point for positive result

| Screening strategy* | Total No of affected live births | Miscarriages due to testing | Total cost† (£1000s) | Incremental cost per affected birth prevented (£1000s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No screening | 16.2 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Maternal age and amniocentesis | 12.0 | 4.9 | 164 | ED‡ |

| Maternal age and chorionic villus sampling | 12.0 | 4.9 | 195 | D‡ |

| First trimester double test | 9.0 | 4.1 | 256 | D‡ |

| Second trimester double test | 8.9 | 5.0 | 245 | D‡ |

| Nuchal translucency measurement§ | 8.6 | 2.6 | 171 | 22‡ |

| Triple test | 8.5 | 4.0 | 234 | ED¶ |

| Quadruple test | 7.7 | 3.6 | 241 | ED¶ |

| First trimester combined test | 7.4 | 2.0 | 238 | ED¶ |

| Integrated test§ | 6.6 | 1.4 | 276 | 51¶ |

Ranked in order of effectiveness (number of Down's syndrome live births).

Above cost of no screening.

Compared with no screening

Most efficient strategies.

Compared with nuchal translucency.

D=dominance—that is, there is a cheaper and more effective strategy; ED=extended dominance—that is, a more effective option has a lower incremental cost effectiveness ratio.

Service providers with an intermediate total budget should consider the first trimester combined test or the quadruple test. Compared with measuring nuchal translucency, the first trimester combined test costs an extra £57 000 per affected liveborn baby prevented (total cost £238 000). At a similar total cost (£241 000), the quadruple test costs an additional £75 000 per affected baby prevented compared with measuring nuchal translucency.

Effects and safety

The integrated test is the most effective and safest strategy. All other strategies result in more liveborn babies with Down's syndrome and more miscarriages of unaffected pregnancies due to amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. Compared with no screening, the integrated test results in 0.14 miscarriages due to chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis per birth of a Down's syndrome baby prevented. The next safest strategies, compared with no screening, are the first trimester combined test (0.22 miscarriages), nuchal translucency measurement (0.34), and the quadruple test (0.42).

Sensitivity analyses

A 50% increase or decrease in the unit costs of chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis would hardly alter the cost effectiveness. If the cost of amniocentesis fell by 50%, the quadruple test would enter the efficiency frontier (cost effectiveness ratio compared with nuchal translucency £39 000 and for the integrated test compared with the quadruple test £51 000).

The cost effectiveness of the screening strategies is most susceptible to variation in the costs of the screening test. A 50% decrease in the unit costs of all screening tests would increase the cost effectiveness ratio of all strategies above that of the integrated test (£19 000 compared with no screening), although the cost effectiveness ratios would be close for nuchal translucency measurement and the first trimester combined test. A 50% increase in the unit costs of measuring nuchal translucency would increase the cost effectiveness ratio for nuchal translucency compared with no screening to £25 000. The cost effectiveness ratios for the first trimester combined, quadruple, and integrated tests would be similar (£51 000-£56 000). The second trimester double test, triple test, maternal age, and first trimester serum test were not cost effective at any of the assumptions tested.

Varying the cut-off point for doing amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling between risks of 1 in 100 and 1 in 400 did not alter the cost effectiveness ranking of the screening strategies. Similarly, varying the risk cut-off point corresponding to a 5% false positive rate for the screening test did not alter the ranking (see www.ich.ucl.ac.uk/srtu).

Discussion

The nuchal translucency measurement, quadruple test, first trimester combined, and integrated tests represent the best options in terms of effectiveness, cost effectiveness, and safety. All other strategies would be less effective, cost more per additional birth of an affected baby prevented, and be less safe. This finding was robust in the sensitivity analyses.

The choice between the four options depends on how much service providers are willing to pay to prevent one affected liveborn baby, on the total budget available for antenatal screening, and on how much service providers value safety. We would expect service providers to be willing to spend at least £30 000 to £40 000 per additional affected baby prevented, as this reflects the incremental costs paid by most service providers that offer screening to all women.14

Implications for practice

These findings contrast with current practice in the United Kingdom, where the second trimester double test is most commonly offered.2 Moving from the double test to the first trimester combined test or quadruple test would not cost any more and would result in 1.5 (for the first trimester combined) or 1.2 (for the quadruple test) fewer affected liveborn babies for every 10 000 pregnancies (table 2). Alternatively, the nuchal translucency measurement would be more effective than the double test (0.3 fewer affected babies) at a total cost saving of £70 000. Finally, moving from the double test to the integrated test would result in 2.3 fewer affected babies and cost £13 000 per additional affected baby prevented.

Limited research on women's preferences suggests that the choice of screening strategy should be based primarily on minimising the number of affected pregnancies that are missed and miscarriages due to chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis.15,16 Timing of test results and termination seem to be a secondary consideration. Nevertheless, given the realistic distribution of gestation at attendance for antenatal screening that we used in our analysis, only 31% of women would be in time for a surgical termination (before 13 weeks gestation) after nuchal translucency or age based screening and none after the first trimester combined test (see www.ich.ucl.ac.uk/srtu).

Implementation issues

Our results are susceptible to variation in performance of screening tests. The performance of serum markers in pregnancies affected by Down's syndrome is highly consistent across different studies,1 whereas performance of nuchal translucency measurement varies widely.17,18 Such variation may be explained by verification bias, chance, referral patterns, variation in test reliability,19 and the use of repeated measurements. We used performance characteristics for nuchal translucency measurement derived from routine screening of 95 000 pregnancies, which were then adjusted for verification bias.4 However, we do not know how much test performance was optimised by repeated measurements or referral for a second opinion. In addition, the performance of the integrated test, which was derived by combining test characteristics for serum tests and the nuchal translucency measurement from different datasets, needs to be evaluated in a study of pregnant women.

A further concern, examined in the sensitivity analysis, is the possibility of an increased relative risk of spontaneous miscarriage in women with a positive test result (>1 in 300 risk of Down's syndrome) compared with those with a negative result. Reports of an increased relative risk range from 1.6 to 2.8 for nuchal translucency measurements ⩾3mm and would diminish the detection rate of nuchal translucency measurement.20,21 In our analysis, a relative risk of 2.8 would result in 1.3 more liveborn babies with Down's syndrome per 10 000 pregnancies after measuring nuchal translucency, but the strategy would still be cost effective.

The choice of screening strategy may be affected by several factors that were beyond the scope of our analysis. Firstly, we did not adopt a societal perspective,13 which would seek to maximise health gain for a given cost. Such analyses are problematic in terms of measures of effect—for example, should the outcome measure be prevented liveborn baby with Down's syndrome or quality adjusted life years.22 There are also difficult decisions about which costs to include. Some previous cost effectiveness analyses included direct and indirect lifetime incremental costs per liveborn baby with Down's syndrome (including education, health, and lost productivity). These ranged from £85 000 in 199023 to £340 000 in 1996.24 The studies avoided including other indirect costs attributable to fetal losses by assuming a replacement pregnancy.

If the lowest estimate (£85 000) for the incremental lifetime costs associated with a Down's syndrome child is included in our analysis the net saving compared with no screening would be largest for the integrated test. The net saving would be £548 000 (costs avoided (9.7 Down's syndrome babies prevented × £85 000)−screening programme costs (£276 000)).

Factors that could affect results

Three factors that we did not consider may affect our results. Firstly, capital costs for additional laboratory or clinical capacity may be incurred for use of the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for inhibin A (the fourth serum marker in the quadruple test), implementation of routine nuchal translucency measurement, or the creation of additional facilities for chorionic villus sampling. Secondly, uptake of all screening tests and termination may not be the same for all strategies and may be lower for the integrated test, which requires two visits. Decreased uptake of termination in later pregnancy is likely and would mean that our analysis overestimates the effectiveness of the integrated and quadruple tests. Thirdly, service providers need to provide for women who attend antenatal booking clinic after the first trimester (up to 35% based on results from 21 000 women in six inner London maternity units25). Alternative strategies for late attenders include no screening, the quadruple test, or strategies to encourage earlier attendance at antenatal booking clinic—for example, by speeding up referrals from primary care.

Conclusions

The choice of screening strategy should be between the integrated test, first trimester combined test, quadruple test, or nuchal translucency measurement. Screening based on maternal age, the second trimester double test, and the first trimester serum test would be less effective, less safe, and more costly than these four options.

Figure.

Cost effectiveness of screening strategies for Down's syndrome with a risk of 1 in 300 as cut-off point for positive result. The continuous line is the efficiency frontier. Gradient represents the additional cost incurred per additional birth prevented of an affected baby by adopting a more effective strategy (compared with next cheapest strategy). Strategies above the efficiency frontier are dominated (more costly and less effective than nuchal translucency measurement or integrated test) or ruled out by extended dominance (more costly or less effective and resulted in higher costs per prevented birth than a more effective option).13

Acknowledgments

John Kingdom and Susan Bewley provided advice on the development of the project and commented on drafts of the report. Maureen Dalziel chaired the reference group and commented on the study design. Roxanne Chamberlain, Jean Chapple, Nick Fisk, Mike Gill, David Highton, M L Ko, Mike Lobb, Lucy Moore, Tracey Reeves, and Tracy Stein were members of the reference group and commented on the study design and results. Susan Bewley, Elizabeth Dormandy, Ross Hastings, Wayne Huttly, Linda Mulhair, Kypros Nicolaides, and Pran Pandya provided information on screening practices. The report may not reflect the views of the funding body.

Footnotes

Funding: The project was commissioned by Maureen Dalziel, Sally Davies, and Ron Kerr from the London regional office of the NHS Executive.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Wald NJ, Kennard A, Hackshaw A, McGuire A. Antenatal screening for Down's syndrome. J Med Screen. 1997;4:181–246. doi: 10.1177/096914139700400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wald NJ, Huttly WJ, Hennessy CF. Down's syndrome screening in the UK in 1998. Lancet. 1999;354:1264. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald NJ, Watt HC, Hackshaw AK. Integrated screening for Down's syndrome based on tests performed during the first and second trimesters. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:461–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolaides KH, Snijders RJ, Cuckle HS. Correct estimation of parameters for ultrasound nuchal translucency screening. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:519–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald NJ, Hackshaw AK. Combining ultrasound and biochemistry in first-trimester screening for Down's syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht CA, Hook EB. The imprecision in rates of Down syndrome by 1-year maternal age intervals: a critical analysis of rates used in biochemical screening. Prenat Diagn. 1994;14:729–738. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970140814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, Nanchahal K, Royston P, Chard T, et al. Maternal serum screening for Down's syndrome in early pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297:883–887. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6653.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, Kennard A, Smith D. Maternal serum screening for Down's syndrome: the effect of routine ultrasound scan determination of gestational age and adjustment for maternal weight. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wald NJ, Densem JW, George L, Muttukrishna S, Knight PG. Prenatal screening for Down's syndrome using inhibin-A as a serum marker. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:143–153. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199602)16:2<143::AID-PD825>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macintosh MC, Wald NJ, Chard T, Hansen J, Mikkelsen M, Therkelsen AJ, et al. Selective miscarriage of Down's syndrome fetuses in women aged 35 years and older. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:798–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snijders RJ, Noble P, Sebire N, Souka A, Nicolaides KH. UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Fetal Medicine Foundation First Trimester Screening Group. Lancet. 1998;352:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Meulen JHP, Mol BW, Pajkrt E, van Lith JM, Voorn W. Use of the disutility ratio in prenatal screening for Down's syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Torrance GW. Reporting cost-effectiveness studies and results. In: Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 276–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torgerson DJ, Spencer A. Marginal costs and benefits. BMJ. 1996;312:35–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7022.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckerling PS, Verp MS, Hadro TA. Preferences of pregnant women for amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for prenatal testing: comparison of patients' choices and those of a decision-analytic model. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuppermann M, Feeny D, Gates E, Posner SF, Blumberg B, Washington AE. Preferences for women facing a prenatal diagnostic choice: long-term outcomes matter most. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:711–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palomaki GE, Knight GJ, McCarthy JE, Haddow JE, Donhowe JM. TI-Screening of maternal serum for fetal Down's syndrome in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:955–961. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mol BW, Lijmer JG, van der Meulen JHP, Pajkrt E, Bilardo CM, Bossuy PM. Effect of study design on the association between nuchal translucency measurement and Down syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:864–869. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pajkrt E, Mol BW, Boer K, Drogtrop AP, Bossuyt PM, Bilardo CM. Intra- and interoperator repeatability of the nuchal translucency measurement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:297–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyett J, Moscoso G, Papapanagiotou G, Perdu M, Nicolaides KH. Abnormalities of the heart and great arteries in chromosomally normal fetuses with increased nuchal translucency thickness at 11-13 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:245–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07040245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bewley S, Roberts LJ, Mackinson AM, Rodeck C. First trimester fetal nuchal translucency: problems with screening the general population.2. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:386–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganiats TG. Justifying prenatal screening and genetic amniocentesis programs by cost-effectiveness analyses: a re-evaluation. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:45–50. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shackley P, McGuire A, Boyd PA, Dennis J, Fitchett M, Kay J, et al. An economic appraisal of alternative prenatal screening programmes for Down's syndrome. J Public Health Med. 1993;15:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beazoglou T, Heffley D, Kyriopoulos J, Vintzileos A, Benn P. Economic evaluation of prenatal screening for Down syndrome in the USA. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:1241–1252. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199812)18:12<1241::aid-pd440>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibb DM, MacDonagh SE, Gupta R, Tookey PA, Peckham CS, Ades AE. Factors affecting uptake of antenatal HIV testing in London: results of a multicentre study. BMJ. 1998;316:259–261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]