Abstract

Purpose

In some reports, 5-fluorouracil has been associated with modest activity in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Pemetrexed is a multitargeted antifolate with activity in tumor types not significantly responsive to other antifolates. We evaluated the efficacy of pemetrexed in a phase II study of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors.

Methods

Patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (excluding small-cell carcinoma) were treated with pemetrexed administered intravenously at a dose of 500 mg/m2 every 21 days. To reduce potential toxicity, patients also received folic acid, vitamin B12 supplementation, and periinfusional treatment with dexamethasone. Patients were followed for response, toxicity, and survival.

Results

The study was designed with a total accrual goal of 32 patients. Due to lack of radiographic responses in patients during the study period, accrual was terminated at 17. However, one patient achieved a delayed partial response following discontinuation of pemetrexed. Ten patients were evaluable for biochemical response; five (50%) experienced >50% decrease in plasma chromogranin A. Among the 17 patients, 5 (29%) discontinued therapy due to treatment-related toxicity. The median overall survival was 12.1 months.

Conclusion

Pemetrexed does not appear to have significant antitumor activity in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. The limited antitumor activity and potential toxicity associated with pemetrexed mirrors experience with the majority of other cytotoxic agents in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Investigation of novel, molecularly targeted agents may offer more promise in this disease.

Keywords: Pemetrexed, Neuroendocrine tumor, Carcinoid tumor, Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

Introduction

Although neuroendocrine tumors are typically indolent, patients with advanced disease ultimately succumb to complications of disease progression or hormonal excess. The efficacy of standard cytotoxic chemotherapy in the treatment of such patients has been limited. Traditional antifolates such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) are commonly incorporated into such regimens but have been associated with only modest activity. In early studies, single-agent 5-FU was associated with a single-agent response rate of 18–26% [1]. The response rates reported for 5-FU in combination with streptozocin have ranged between 16 and 21% among patients with metastatic carcinoid tumors. In patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, a three-drug combination of streptozocin, 5-FU, and doxorubicin has been associated with an overall response rate of 39% [2-4]. However, these regimens have also been associated with significant side-effects, including renal toxicity and myelosuppression. Similar activity but less toxicity has been observed with the combination of lomustine, a streptozocin derivative, and 5-FU. A retrospective analysis of 31 patients with neuroendocrine tumors treated with the combination of lomustine and 5-FU reported a partial response rate of 21% [5].

A response rate of 71% was reported for the combination of the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine in combination with temozolomide in a study of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [6]. However, the relative contribution of capecitabine to the activity observed with these regimens is uncertain, as activity as also been observed with temozolomide in combination with thalidomide or bevacizumab [7, 8].

Pemetrexed is a multitargeted antifolate that in vitro has been shown to inhibit thymidylate synthase (TS), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GARFT), all folate-dependent enzymes involved in the de novo biosynthesis of thymidine and purine nucleotides [9-11]. Pemetrexed is active in multiple tumor types, including non-small-cell lung carcinoma and malignant mesothelioma, and diseases not known to be responsive to other antifolates [12-14]. In light of the promising activity observed with pemetrexed in other tumor types, and the lack of a standard, effective chemotherapy for neuroendocrine tumors, we conducted a multi-institutional phase II trial to assess the activity of pemetrexed in patients with neuroendocrine tumors.

Patients with metastatic carcinoid or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were treated with pemetrexed at a dose of 500 mg/m2 administered intravenously every 21 days. Folate and vitamin B12 nutritional status affects the toxicity of pemetrexed. Supplementation with low dose folic acid and vitamin B12 reduces pemetrexed-related toxicity and was mandatory in our study [15]. Patients were followed for a primary endpoint of radiologic tumor response, as well as for evidence of biochemical response, toxicity, and survival.

Patients and methods

Patient population

The study population consisted of patients with histologically confirmed, metastatic or locally unresectable neuroendocrine tumors, excluding small-cell carcinoma. Patients were further required to have measurable disease (by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST]), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or better; life expectancy of at least 12 weeks; adequate renal function (creatinine clearance ≥45 ml/min), hepatic function (serum bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dl; AST ≤3 times ULN, or ≤5 times ULN if there was evidence of liver metastases); and bone marrow function (absolute neutrophil count ≥1,500/mm3; platelets ≥100,000/mm3).

Prior treatment with chemotherapy, other than pemetrexed, was permitted, as was prior treatment with chemoembolization or cryotherapy. Prior chemotherapy must have been completed 4 or more weeks before initiation of pemetrexed. Lesions treated with prior radiation, cryotherapy, or chemoembolization were not considered measurable disease for the purpose of this protocol, and concurrent treatment with these treatment modalities was not permitted. Participating centers included Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital (all in Boston, MA).

Patients were excluded if they had clinically apparent CNS metastases or carcinomatous meningitis, history of myocardial infarction in the 6 months before protocol treatment, history of major surgery within 2 weeks before treatment initiation, or history of uncontrolled serious medical or psychiatric illness. Patients who were pregnant or lactating were excluded from study entry. All patients were required to be able to take vitamin supplementation according to protocol requirements, and provided signed, informed consent as required by the institutional review boards of their respective institutions.

Treatment program

Pemetrexed was administered at a dose of 500 mg/m2 as an intravenous infusion given every 21 days until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Three weeks of study drug was considered to be one cycle of treatment. Folic acid was taken as an oral dose beginning 5–7 days prior to the first dose of pemetrexed and continued daily until 3 weeks after the last dose of pemetrexed. Patients took 350–1,000 μg of folic acid or a multivitamin containing folic acid in the range of 350–600 μg daily. Vitamin B12 was administered as a 1,000 μg intramuscular injection 1–2 weeks prior to the first dose of pemetrexed and continued approximately every 9 weeks until 3 weeks after the last dose of pemetrexed. Patients received dexamethasone 4 mg given orally twice daily on the day before, the day of, and the day after each dose of pemetrexed for rash prophylaxis, unless medically contraindicated.

Dose adjustments for pemetrexed were made for hematologic toxicity. Treatment was held if patients developed an ANC less than 1,500/mm3 or a platelet count of less than 100,000/mm3, and was not resumed until full hematologic recovery. On recovery, treatment was resumed with a dose reduction of 75% of the previous dose of pemetrexed. For patients developing treatment-related non-hematologic toxicities, pemetrexed was withheld until resolution to less than or equal to the patient’s pre-therapy value. Treatment was resumed at 75% of the previous dose for any Common Toxicity Criteria grade 3 or 4 toxicity. Pemetrexed was discontinued if a patient experienced any treatment-related hematologic or non-hematologic grade 3 or 4 toxicity after 2 dose reductions. Patients who were unable to resume therapy within 3 weeks were removed from study treatment. Treatment was also discontinued if the patient experienced unacceptable toxicity levels.

Radiologic tumor assessments with computed tomography scan, as well as biochemical assessments with plasma chromogranin A levels were performed every 3 cycles (9 weeks) after initiation of treatment. Radiologic response was classified according to RECIST. Biochemical response, a secondary end point in the protocol, was defined as a decrease in chromogranin A by 50% or more from baseline (in patients with an elevated chromogranin A at baseline).

Statistical considerations

This phase II study was designed with the primary end point of response. A true response rate of ≥15% would have been considered evidence of promising activity in this patient population, whereas a response rate of <5% would have been considered evidence of inactivity. The study used a two-stage design. Once accrual had reached 17 patients, at least one response (CR or PR) was required to proceed to the complete accrual goal of 32 patients. The drug would have been considered active if the second stage was completed with 3 or more responses. With this design, the probability of terminating the study after 17 patients was 0.42 if the true, but unknown, response rate was 5% and 0.06 if the true, but unknown, response rate was 15%. Progression-free and overall survival estimates were calculated using Kaplan–Meier methodology [16]. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from date of study entry to the first documentation of objective tumor progression or death; patients who were removed from the study without evidence of disease progression or death were censored at the time they were removed from the study. Toxicity and complications of treatment were assessed based on reports of adverse events, physical examinations, and laboratory measurements.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study was designed with a total accrual goal of 32 patients. However, due to lack of radiographic response, accrual was terminated at 17 patients. The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients had a median age of 58 years; 76% were male, and 24% were female. The majority (71%) had an ECOG performance status of 1. Eleven patients (65%) had metastatic carcinoid tumors, 5 (29%) had metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and 1 (6%) had metastatic pheochromocytoma. All patients, with the exception of one patient with a poorly differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, had well to moderately differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Thirteen patients (76%) had received prior chemotherapy, which included traditional neuroendocrine tumor regimens containing streptozocin, doxorubicin, fluorouracil, or temozolomide. Nine patients received prior therapy with octreotide and remained on octreotide at the same dose during study therapy. The median chromogranin A level at baseline was 526.6 ng/ml, with a range of 4.4–36,647.1 ng/ml; 10 patients had elevated chromogranin A levels (>36.4 ng/ml) at baseline and were subsequently assessable for biochemical response.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (N = 17) |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 58 | |

| Range | 38–76 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 | 24 |

| Female | 13 | 76 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 4 | 24 |

| 1 | 12 | 71 |

| 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Type of tumor | ||

| Carcinoid | 11 | 65 |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | 5 | 29 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 1 | 6 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||

| Well or moderately differentiated | 16 | 94 |

| Poorly differentiated | 1 | 6 |

| Presence of functional syndromea | 7 | 41 |

| Location of metastasesb | ||

| Liver | 17 | 100 |

| Lymph node | 9 | 53 |

| Other | 7 | 41 |

| Prior treatment | ||

| Chemoembolization | 5 | 29 |

| Chemotherapy | 13 | 76 |

| Octreotide | 9 | 53 |

| XRT | 3 | 18 |

| Interferon | 4 | 24 |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimensc | ||

| 0 | 4 | 24 |

| 1 | 5 | 29 |

| 2 | 3 | 18 |

| 3 | 3 | 18 |

| 4 | 2 | 12 |

| Patients with elevated chromogranin A | 10 | 59 |

| Baseline chromogranin A (ng/mL) | ||

| Median | 526.6 | |

| Range | 4.4–36,647.1 |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Presence of carcinoid syndrome or functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (1 insulinoma)

Does not sum to 100%, as patients may have metastases to more than one location

Prior chemotherapy regimens: streptozocin/doxorubicin (three patients), capecitabine (two patients), dacarbazine (two patients), temozolomide/bevacizumab (seven patients), fluorouracil/bevacizumab (one patient), temozolomide/thalidomide (two patients), bevacizumab (three patients), endostatin (one patient), sunitinib (three patients)

Treatment administration and toxicity

Seventeen patients received treatment for a median of 69 days (range, 15–300 days). Treatment-related adverse events are summarized in Table 2. Neutropenia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia were the most common grade 3 or 4 treatment-related hematologic toxicities, observed in 29, 18 and 18% of patients, respectively. Grade 3 fatigue was observed in 7 (41%) patients. Less common toxicities included edema, skin rash, and mild nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea.

Table 2.

Treatment-related toxicity

| Toxicity | Maximum toxicity grade |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|||||

| No. of patients |

Percent | No. of patients |

Percent | No. of patients |

Percent | No. of patients |

Percent | |

| Hematologic | ||||||||

| Hemoglobin | 4 | 24 | 6 | 35 | 1 | 6 | – | – |

| Leukocytes | 1 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 12 |

| Neutrophils | 1 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 18 |

| Lymphocytes | 3 | 18 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 |

| Platelets | 4 | 24 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 |

| Non-hematologic | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 3 | 18 | 4 | 24 | 7 | 41 | – | – |

| Nausea | 4 | 24 | 4 | 24 | – | – | – | – |

| Constipation | 3 | 18 | 1 | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| Vomiting | 4 | 24 | 2 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Anorexia | 3 | 18 | 2 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Rash | 3 | 18 | 3 | 18 | – | – | – | – |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness | 3 | 18 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Edema | 4 | 24 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 | – | – |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 | – | – |

| Dyspnea | 2 | 12 | – | – | 1 | 6 | – | – |

| Pneumonitis | – | – | – | – | 2 | 12 | – | – |

| Fever | 3 | 18 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dehydration | – | – | 1 | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| Elevated AST | 9 | 53 | 2 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Proteinuria | 1 | 6 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 6 |

Five (29%) patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-related toxicity (Table 3). The median time to treatment discontinuation for toxicity was 69 days. Toxicities resulting in treatment discontinuation included pneumonitis (two patients), edema (one patient), elevation in creatinine (one patient), and thrombocytopenia (one patient). Other reasons for treatment discontinuation included withdrawal of consent (35%) or disease progression (35%). There were no treatment-related deaths.

Table 3.

Reason for treatment discontinuation

| Reason off study | Patients |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | Percent a | |

| Treatment-related toxicity | 5 | 29 |

| Progressive disease | 6 | 35 |

| Patient withdrew consent | 6 | 35 |

Percentages do not add to 100% due to rounding

Efficacy

No patients experienced complete or partial radiologic responses by RECIST guidelines while receiving treatment on study (Table 4). Nine patients (53%) had stable disease at the 9-week follow-up imaging, and of these patients, 4 (24%) continued to have stable disease at 18 weeks. Six patients (35%) had progressive disease as their best response to therapy. Eight patients had radiographic progression of disease prior to initiating therapy with pemetrexed; two of these eight patients had stable disease at the 9-week follow-up imaging. One patient with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, previously treated with the combination of temozolomide and bevacizumab, who stopped treatment after three cycles due to toxicity had stable disease at the time treatment was discontinued. However, she had gradual shrinkage of tumor off therapy and eventually achieved a partial response more than 1 year after stopping treatment. The patient received no additional therapy, including octreotide, and the response has been maintained for over 2 years.

Table 4.

Tumor response among patients receiving pemetrexed

| Disease response | No. | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Complete or partial response | 0 | – |

| Stable disease | 9 | 53 |

| >9 weeks | 5 | 29 |

| >18 weeks | 4 | 24 |

| Progressive disease | 6 | 35 |

| Not evaluablea | 2 | 12 |

One patient was removed from study because of treatment-related toxicity without documented progressive disease by RECIST criteria. One patient was removed from study because of a prolonged treatment delay without documented progressive disease by RECIST criteria

Ten patients had elevated chromogranin A levels at baseline and were subsequently evaluable for chromogranin A response. Of these patients, five (50%) experienced decreases of chromogranin A of more than 50%, and five (50%) had stable or progressive chromogranin A levels (≥25% increase) as their best response to treatment. The five patients with evidence of biochemical response included four patients with carcinoid tumor and one with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Only the patient with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, whose prior treatment included hepatic chemoembolization and multiple lines of systemic therapy consisting of capecitabine, interferon, temozolomide and thalidomide, had a sustained biochemical response lasting more than two cycles of treatment.

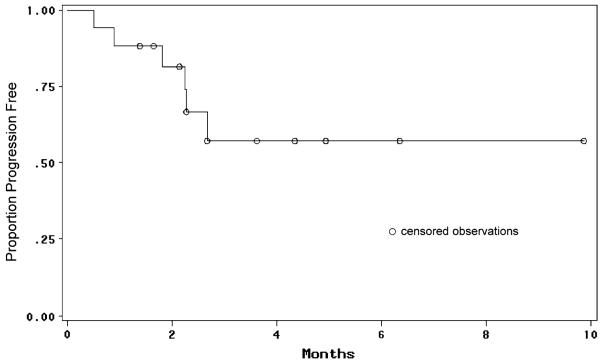

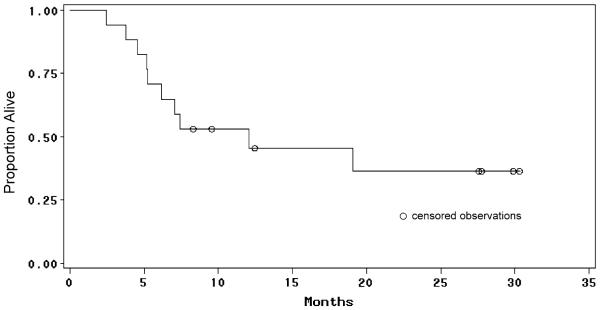

The median follow-up time for the patient cohort was 8.3 months (range, 2.5–30.3 months). Six-month progression-free survival was 61%; median progression-free survival could not be assessed due to the high number of censored patients who withdrew from study treatment without radiological progression (Fig. 1). To date, 10 patients (59%) have died; the median overall survival time for the entire study population was 12.1 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival

Fig. 2.

Overall survival

Discussion

While designed with an original accrual goal of 32 patients, a lack of radiographic tumor responses in the first 17 patients during the study period resulted in early termination of the study. Interestingly, however, one patient with stable disease who stopped treatment due to toxicity had gradual shrinkage of tumor off therapy and eventually achieved a partial response more than 1 year after stopping treatment. Additionally, 5 of 10 evaluable patients experienced biochemical (chromogranin A) responses although the duration of response was limited.

The identification of a single patient with a delayed response, together with evidence of biochemical responses, suggests that pemetrexed may have modest, though limited, activity in neuroendocrine tumors. The relatively limited efficacy of pemetrexed parallels prior experience with 5-FU in neuroendocrine tumors. Pemetrexed, like 5-FU, is an inhibitor of thymidylate synthase. The efficacy of 5-FU has been shown to be inversely correlated with thymidylate synthase (TS) levels. Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors have been shown to have relatively high TS mRNA levels, possibly explaining their relative resistance to fluoropyrimidines and related drugs [17].

A high proportion (29%) of patients discontinued treatment due to toxicity, and an even greater proportion (35%) withdrew consent while on the study. The majority of patients (82%) reported fatigue, and 41% experienced grade 3 fatigue interfering with activities of daily living. These findings contrast with relatively good tolerance of pemetrexed in other tumor types, including mesothelioma and lung cancer. The relatively poor tolerance of pemetrexed in our patient population may be related to the fact that the majority of patients (76%) had undergone prior treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy, and 29% had undergone hepatic-directed therapy with chemoembolization. The presence of carcinoid syndrome and chronic diarrhea in some of our patients may also have resulted in nutritional impairment, making patients more prone to pemetrexed-associated toxicity.

Interstitial pneumonitis has been reported as a rare toxicity associated with pemetrexed [18]. Two patients in this study experienced pneumonitis attributed to pemetrexed. Both patients developed fever, cough, and dyspnea following the third dose of pemetrexed. Chest CT scan revealed scattered ground-glass opacities in one case and bilateral consolidation in the other. Infectious disease evaluation was unremarkable for both patients, one of whom underwent bronchoscopy. In both cases, symptoms and radiographic findings improved after discontinuation of pemetrexed without need for steroids.

To date, alkylating agents have demonstrated the most consistent antitumor activity in neuroendocrine tumors. While the combination of streptozocin and fluorouracil has modest activity in patients with carcinoid tumors, the association of this regimen with both renal and hematologic toxicity has precluded its widespread use, particularly in light of the often indolent nature of this disease. Regimens incorporating either streptozocin or temozolomide appear to have greater activity in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and are increasingly used in this setting. With the exception of temozolomide, most newer cytotoxic agents have proved relatively inactive in neuroendocrine tumors. High-dose paclitaxel, administered with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor, was evaluated in 24 patients with metastatic carcinoid or islet cell tumors [19]. Significant hematologic toxicity was observed, and responses were noted in only 8% of patients. Docetaxel was associated with biochemical responses but did not result in any radiologic responses in a recent Phase II trial involving 21 patients with carcinoid tumors [20]. Similarly, no objective radiologic response were seen in a phase II study of 19 patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors treated with gemcitabine [21].

Novel, targeted agents currently in development or under investigation may prove more promising in neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrine tumors are highly vascular, and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) along with VEGF receptor (VEGFR) subtypes, has been observed in both carcinoid tumors and in pancreatic endocrine tumors [22]. In a phase II trial, 44 patients with advanced or metastatic carcinoid tumors on a stable dose of octreotide were randomly assigned to receive either bevacizumab (15 mg/kg), a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF, or pegylated interferon-α-2b (0.5 μg/kg) [23]. Four of 22 patients (18%) treated with bevacizumab achieved confirmed radiographic partial responses compared with none of the patients who received pegylated IFN-α-2b. After 18 weeks, 95% of patients treated with bevacizumab remained progression free, compared with 68% of patients treated with IFN-α-2b. Sunitinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against VEGFR-1 to 3, platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT-3), c-Kit and RET, has antitumor activity due to both inhibition of angiogenesis and direct antiproliferative effects on tumor cells. In a phase II trial of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors treated with sunitinib, radiographic responses were observed in 16.7% (11 of 66 patients) of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and 2.4% (1 of 41 patients) of patients with carcinoid tumors [24]. High rates of stable disease were also observed. Finally, in another recent phase II trial, 51 patients with carcinoid tumors and 42 patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were treated with sorafenib, a small molecule that inhibits multiple kinases, including VEGFR-2, PDGFR-β and the RAF serine/threonine kinases along the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway [25]. Confirmed partial response rates to treatment were seen in 7% of patients with carcinoid tumors and 11% of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. 58% of patients with carcinoid tumors and 72% of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were progression free at 6 months.

Encouraging results have also been obtained in studies with inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine-threonine kinase that participates in the regulation of cell growth, proliferation, and apoptosis through modulation of the cell cycle. In a multicenter study, 37 patients with advanced progressive neuroendocrine tumors were treated with weekly intravenous temsirolimus. The intent-to-treat response rate for the cohort was 5.6%. Outcomes were similar between patients with carcinoid and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [26]. Additionally, a recent phase II clinical trial examined the combination of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus at a dose of 5 or 10 mg per day and Sandostatin LAR in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors [27]. The response rates to treatment among 30 patients with carcinoid tumors and 30 patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were 17 and 27%, respectively. Clinical trials are ongoing to conWrm the activity of everolimus in this population.

In conclusion, we observed only modest activity associated with pemetrexed in neuroendocrine tumor patients. Our observations are limited to some extent by relatively small patient numbers and the inclusion of a heavily pretreated patient population; furthermore, our trial was not designed to assess a potential impact on time to tumor progression. Nevertheless, the toxicity observed with pemetrexed in this patient population would likely preclude its routine use for this indication. Investigation of novel, molecularly targeted agents may offer more promise in this disease.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the Stephen and Caroline Kaufer Fund for Neuroendocrine Tumor Research. Pemetrexed was supplied by Lilly, Inc. The authors acknowledge additional support from the Saul and Gitta Kurlat Fund for Neuroendocrine Tumor Research, and NCI grants CA093401 (MHK) and P50 CA127003 (DF/HCC SPORE in Gastrointestinal Cancer).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement None.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Chan, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Andrew X. Zhu, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Keith Stuart, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Pankaj Bhargava, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Craig C. Earle, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Jeffrey W. Clark, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Carolyn Casey, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Eileen Regan, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Matthew H. Kulke, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dana 1220, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA

References

- 1.Moertel CG. Treatment of the carcinoid tumor and the malignant carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1(11):727–740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.11.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engstrom P, Lavin P, Moertel C, Folsch E, Douglass H. Streptozocin plus fluorouracil versus doxorubicin therapy for metastatic carcinoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:1255–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.11.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kouvaraki M, Ajani J, Hoff P, Wolff R, Evans D, Lozano R, Yao J. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4762–4771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun W, Lipsitz S, Catalano P, Mailliard JA, Haller DG. Phase II/III study of doxorubicin with fluorouracil compared with streptozocin with fluorouracil or dacarbazine in the treatment of advanced carcinoid tumors: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1281. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4897–4904. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaltsas GA, Mukherjee JJ, Isidori A, Kola B, Plowman PN, Monson JP, Grossman AB, Besser GM. Treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours using combination chemotherapy with lomustine and 5-fluorouracil. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57(2):169–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strosberg J, Choi J, Gardner N, Kvols L. First-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas with capecitabine and temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 (May 20 Suppl):Abstract 4612 (2009 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulke M, Stuart K, Earle C, Bhargava P, Clark J, Enzinger P, Meyerhardt J, Attawia M, Lawrence C, Fuchs C. A phase II study of temozolomide and bevacizumab in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18S) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3147. June 20 Suppl): Abstract 4044 (2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulke MH, Stuart K, Enzinger PC, Ryan DP, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, Vincitore M, Michelini A, Fuchs CS. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):401–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelsohn LG, Shih C, Chen VJ, Habeck LL, Gates SB, Shackelford KA. Enzyme inhibition, polyglutamation, and the effect of LY231514 (MTA) on purine biosynthesis. Semin Oncol. 1999;26(2 Suppl 6):42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz RM, Patel VF, Worzalla JF, Shih C. Role of thymidylate synthase in the antitumor activity of the multitargeted antifolate, LY231514. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(1A):437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih C, Chen VJ, Gossett LS, Gates SB, MacKellar WC, Habeck LL, Shackelford KA, Mendelsohn LG, Soose DJ, Patel VF, Andis SL, Bewley JR, Rayl EA, Moroson BA, Beardsley GP, Kohler W, Ratnam M, Schultz RM. LY231514, a pyrrolo[2, 3-d]pyrimidine-based antifolate that inhibits multiple folate-requiring enzymes. Cancer Res. 1997;57(6):1116–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanauske AR, Chen V, Paoletti P, Niyikiza C. Pemetrexed disodium: a novel antifolate clinically active against multiple solid tumors. Oncologist. 2001;6(4):363–373. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-4-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, Gatzemeier U, Tsao TC, Pless M, Muller T, Lim HL, Desch C, Szondy K, Gervais R, Shaharyar C, Manegold S, Paul P, Paoletti L, Einhorn PA, Bunn Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, Gatzemeier U, Boyer M, Emri S, Manegold C, Niyikiza C, Paoletti P. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2636–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scagliotti GV, Shin DM, Kindler HL, Vasconcelles MJ, Keppler U, Manegold C, Burris H, Gatzemeier U, Blatter J, Symanowski JT, Rusthoven JJ. Phase II study of pemetrexed with and without folic acid and vitamin B12 as front-line therapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(8):1556–1561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceppi P, Volante M, Ferrero A, Righi L, Rapa I, Rosas R, Berruti A, Dogliotti L, Scagliotti GV, Papotti M. Thymidylate synthase expression in gastroenteropancreatic and pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):1059–1064. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loriot Y, Ferte C, Gomez-Roca C, Moldovan C, Bahleda R, Wislez M, Cadranel J, Soria JC. Pemetrexed-induced pneumonitis: a case report. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10(5):364–366. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ansell SM, Pitot HC, Burch PA, Kvols LK, Mahoney MR, Rubin J. A Phase II study of high-dose paclitaxel in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2001;91(8):1543–1548. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010415)91:8<1543::aid-cncr1163>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulke M, Fuchs C, Stuart K, Ryan D, Enzinger P, Vincitore M, Berg D, Clark J, Mayer R. Phase II study of docetaxel in patients with metastatic carcinoid tumors. Cancer Investig. 2004;22(3):353–359. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200029058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulke MH, Kim H, Clark JW, Enzinger PC, Lynch TJ, Morgan JA, Vincitore M, Michelini A, Fuchs CS. A Phase II trial of gemcitabine for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2004;101(5):934–939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terris B, Scoazec J, Rubbia L. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in digestive neuroendocrine tumors. Histopathology. 1998;32:133–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao JC, Phan A, Hoff PM, Chen HX, Charnsangavej C, Yeung SC, Hess K, Ng C, Abbruzzese JL, Ajani JA. Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor in advanced carcinoid tumor: a random assignment phase II study of depot octreotide with bevacizumab and pegylated interferon alpha-2b. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1316–1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulke MH, Lenz HJ, Meropol NJ, Posey J, Ryan DP, Picus J, Bergsland E, Stuart K, Tye L, Huang X, Li JZ, Baum CM, Fuchs CS. Activity of sunitinib in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3403–3410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobday TJ, Rubin J, Holen K, Picus J, Donehower R, Marschke R, Maples W, Lloyd R, Mahoney M, Erlichman C. MC044h, a phase II trial of sorafenib in patients (pts) with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (NET): a phase II consortium (P2C) study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S) June 20 Suppl):Abstract 4504 (2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duran I, Kortmansky J, Singh D, Hirte H, Kocha W, Goss G, Le L, Oza A, Nicklee T, Ho J, Birle D, Pond GR, Arboine D, Dancey J, Aviel-Ronen S, Tsao MS, Hedley D, Siu LL. A phase II clinical and pharmacodynamic study of temsirolimus in advanced neuroendocrine carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(9):1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, Wolff RA, Hess K, Gupta S, Jacobs C, Mares JE, Landgraf AN, Rashid A, Meric-Bernstam F. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4311–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]