Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE

Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressive drug used for the prevention of the allograft rejection in the kidney allograft recipients. It exhibits a narrow therapeutic index and a large pharmacokinetic variability. Tacrolimus is mainly metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 3A5, and effluxed via ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp), encoded by ABCB1 gene. The influence of CYP3A5*3 on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus has been well characterized. On the other hand, the contribution of polymorphisms in other genes is controversial. In addition, the involvement of other efflux transporter than P-gp in tacrolimus disposition is uncertain. The present study was designed to investigate the effects of genetic polymorphisms of CYP3As and efflux transporters on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A total of 500 blood concentrations of tacrolimus from 102 adult stable kidney transplant recipients were included in the analyses. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genes as well as the genes of efflux transporters including P-gp (ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP2/ABCC2) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) were genotyped. For ABCC2 gene, haplotypes were determined as follows: H1 (wild type), H2 (1249G>A), H9 (3972C>T) and H12 (−24C>T and 3972C>T). Population pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using nonlinear mixed effects modeling.

RESULTS

Analyses revealed that CYP3A5 expressers (CYP3A5*1 carriers) and MRP2 high activity group (ABCC2 H2/H2 and H1/H2) decreased the dose-normalized trough concentration of tacrolimus by 2.3-fold (p<0.001) and 1.5-fold (p=0.007), respectively. The pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus was best described using a two-compartment model with first order absorption and an absorption lag time. In the population pharmacokinetic analysis, CYP3A5 expressers and MRP2 high activity groups were identified as the significant covariates for tacrolimus apparent clearance expressed as 20.7 × (Age/50)−0.78 × 2.03 (CYP3A5 expressers) × 1.40 (MRP2 high activity group). No other CYP3A4, ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphisms were associated with the apparent clearance of tacrolimus.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first report that MRP2/ABCC2 has crucial impacts on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in a haplotype specific manner. Determination of ABCC2 as well as CYP3A5 genotype may be useful for more accurate tacrolimus dosage adjustment.

INTRODUCTION

The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus is an immunosuppressive agent used in combination with mycophenolic acid or corticosteroids for the prevention of the allograft rejection in solid organ transplant recipients.[1] Tacrolimus exhibits a narrow therapeutic index and considerable interindividual pharmacokinetic variability.[2] Therefore, routine therapeutic drug monitoring is an integral part of tacrolimus immunosuppressive therapy.[3]

Tacrolimus is extensively metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 3A5 in the liver and small intestine.[4, 5] In addition, it is a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), encoded by multidrug resistance (MDR) 1/ABCB1 gene.[6] Pharmacogenetic studies indicate that the interindividual variability in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics can be partly related to genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A and ABCB1 genes.[7] Among them, the most frequently investigated polymorphism is CYP3A5*3 (6986A>G, rs776746), which causes an alternative splicing and is associated with low levels of CYP3A5 functional protein.[8, 9] CYP3A5 expressers, who carried at least one CYP3A5*1 (wild type) allele, showed a lower dose-adjusted tacrolimus concentration and a higher dose requirement compared to CYP3A5 non-expressers (CYP3A5*3 homozygotes).[7] Several population pharmacokinetic analyses have demonstrated that CYP3A5*3 had a significant impact on the apparent clearance of tacrolimus.[10, 11]

Accumulating evidences indicate that in the small intestine, CYPs and efflux transporters, mainly CYP3A and P-gp, cooperatively function as the absorption barrier.[12] Using the pig intestinal mucosa in an Ussing chamber, Lampen et al.[13] have demonstrated that when tacrolimus was added to the luminal side of the intestinal preparation, more than 90% of the metabolites were transported from the tissue back into the luminal chamber, most likely by active transport. The concentrations of tacrolimus were more than 100-fold higher than the concentrations of the formed metabolites and these findings suggested that the metabolites of tacrolimus either have a higher affinity for the P-gp than the parent or are substrates of a different transporter.[12] In the small intestine, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2: encoded by ABCC2 gene) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP: encoded by ABCG2 gene) as well as P-gp play an important role in the efflux of xenobiotics.[14] Compared to ABCB1 polymorphisms, the information on the association between the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus and polymorphisms in ABCC2 and ABCG2 genes are limited. Therefore, in this study, the effects of polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, ABCB1, ABCC2 and ABCG2 genes on the dose-normalized concentration of tacrolimus have been investigated in adult stable kidney transplant recipients. Furthermore, using a population pharmacokinetic approach, we have examined whether these polymorphisms can account for the interindividual variability in the population pharmacokinetic parameters of tacrolimus.

METHODS

Patients

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rhode Island Hospital (IRB#0159-03, 0054-05, 0066-06, 4060-10 and 4176-10), and all patients gave informed consent to participate. Patients were excluded if they were suffering from severe liver dysfunction, were pregnant, nursing or younger than 18 years of age. In addition, patients with pancreatic transplantation were excluded from the study. In total, 102 adult stable kidney transplant recipients were included in this study. Detail demographic information is presented in Table 1. All study participants received triple immunosuppressive drug regimens including tacrolimus oral tablets (Prograf, Astellas Pharma US Inc., Northbrook, IL, USA), prednisone and mycophenolic acid.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and clinical data of 102 adult kidney transplant recipients.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 74 |

| Female | 28 |

| Ethnicity (n) | |

| Caucasian | 73 |

| Hispanic | 14 |

| African American | 11 |

| Asian | 2 |

| American Indian | 2 |

| Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (n) | |

| Non-diabetics | 38 |

| Diabetics | 64 |

| Age (y) | 50 (18–74) |

| Body weight (kg) | 85.2 (47.7–145.0) |

| Tacrolimus dose (mg/day) | 4 (1–18) |

| Prednisone dose (mg/day) | 5.0 (2.5–50.0) |

| Mycophenolic acid dose (mg/day) | 739.0 (369.5–1477.9) |

| Time post transplantation (mo) | 24 (2–123) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.5 (26.1–54.0) |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.9 (4.0–11.8) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 115 (36–601) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 19 (9–333) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 18 (4–98) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 76 (23–291) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.3 (3.3–4.8) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 21 (9–53) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min)a | 78.3 (33.7–190.0) |

Values are expressed as median (range) unless specified otherwise.

Creatinine clearance was estimated using Cockcroft-Gault formula.

Pharmacokinetic study

On the day of pharmacokinetic study, subjects underwent routine physical examination including blood pressure, height and weight measurement. After collecting the pre-dose (trough) blood sample (4.0 mL) into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) vacutainers (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), immunosuppressive drugs were administered. Blood samples (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10 and 12-hours post-dose) were then collected up to 12 hours from 31 patients, whereas two blood samples (pre-dose and 2-hours post-dose) were collected from 71 patients. We have selected 0 and 2 hour post dose because trough concentration usually reflect the elimination phase whereas concentration at 2 hour post dose, although is not monitored, but it is around the absorption phase of the drug. The whole blood samples were immediately stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Bioanalytical assay

Quantitative analysis of tacrolimus was performed using a previous published and utilized assay using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to an API 4000 tandem mass spectroscopy system (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a turbo electrospray ion source.[15] In brief, sample preparation involved the addition of 800 μL of ZnSO4 (17.28 g/L): methanol (30:70, v/v) containing the internal standard (ascomycin, 100 ng/mL) to a 200 μL aliquot of EDTA anticoagulated whole blood, calibration standards or quality control samples. Samples were vortex mixed, centrifuged (13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C), and 50 μL of supernatant was injected onto an HPLC column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm, Eclipse Zorbax XDB -C8, Agilent Technologies) maintained at 65°C. The mobile phase that consisted of (A) HPLC grade methanol with 0.1% v/v formic acid and (B) 0.1% v/v formic acid was pumped at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The mass spectrometer was run in the single ion mode and focused on the [M+Na]+ of tacrolimus and ascomycin (internal standard). The lower limit of quantification for tacrolimus in human EDTA whole blood was at 62.5 pg/mL and the range of reliable response was from 62.5 pg/mL to 25.0 ng/mL. Inter-day accuracies for tacrolimus was within 85–115% and total imprecision was <15%.

Genotyping of CYP3A4, CYP3A5, ABCB1, ABCC2 and ABCG2 genes

Genomic DNA from patients’ peripheral blood sample was extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and was stored at −80°C until analysis. CYP3A4*22 (rs35599367), CYP3A5*3, ABCB1 1236C>T (rs1128503), 2677G>T,A (rs2032582) and 3435C>T (rs1045642), ABCC2 −24C>T (rs717620), 1249G>A (rs2273697) and 3972C>T (rs3740066), and ABCG2 421C>A (rs2231142) were determined by TaqMan® allelic discrimination assay (Life Technologies, Foster, CA, USA) using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. CYP3A4*1B (rs2740574) was genotyped by polymerase chain reaction amplification and the subsequent direct sequencing using Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies). The primers for the amplification of CYP3A4 gene were described previously.[16] ABCC2 haplotypes were determined using Haploview version 4.1.[17]

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS software (version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 4.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Normal distribution of log transformed tacrolimus concentration was verified using Shapiro-Wilk test and significance level was tested using independent samples t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni correction. Comparisons of tacrolimus dose were carried out using Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test.

Population pharmacokinetic modeling was performed using nonlinear mixed effects modeling with NONMEM (version 7.2.0, ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA). PLT Tools (P Less Than, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used as an interface for NONMEM. Double-precision, first-order conditional estimation (FOCE) with interaction and subroutines ADVAN4 TRANS4 were used. The model selection was based on goodness-of-fit criteria, including diagnostic plots, minimum objective function value (MOFV) after accounting for the number of fitted parameters, precision and the physiological plausibility of the estimates. The inter-subject variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters was modeled assuming an exponential distribution. Additive, proportional and combined proportional and additive models were investigated but a proportional error model has best described the variability in the data.

Covariates (sex, ethnicity, diabetes, age, weight, time post-transplantation, hematocrit, hemoglobin A1c, glucose, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, creatinine clearance, concomitant prednisone dose, concomitant mycophenolic acid dose and genetic polymorphisms) were examined graphically via plots of η vs. covariate values, where η is the individual random effect with a mean of 0 and a variance of ω2. The candidate covariates identified during graphical screening were then tested in NONMEM. The influence of continuous covariates on the pharmacokinetic parameters was modeled according to a power model scaled to the population median covariate value. The influence of categorical covariates on the pharmacokinetic parameters was modeled using a proportional relationship.

The statistical significance of the covariates was assessed using a likelihood ratio test corresponding to a decrease in MOFV of <3.84 (with one degree of freedom: p<0.05) in comparisons between two hierarchical models. These covariates were then included in the basic population model using forward stepwise method until objective function no longer improved. A covariate was retained in the model if the objective function changed by 6.63 or greater (p<0.01) when it was removed from the full model. This was repeated and continued until all remaining covariates were significant in the final model.

The predictability of the final model was evaluated using visual predictive check. Data for 1000 datasets were simulated and compared with the observed data set. Within the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the simulated concentration, a 95% prediction interval was constructed and plotted along with the observed data and the median of the simulated concentration. A bootstrap procedure was performed to determine the stability and robustness of the final model. Thousand bootstrap re-samples of the original dataset were created, and these were evaluated using the final model.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

Demographic characteristics, doses of immunosuppressive agents and biochemical indices of study participants are presented in Table 1. None of the study subjects were administered drugs that are known to inhibit or induce tacrolimus disposition.

Effects of genetic polymorphisms on C0 and C2 of tacrolimus

Allele frequencies of genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, ABCB1, ABCC2 and ABCG2 genes are shown in Table 2. We investigated the effects of these polymorphisms on dose-normalized tacrolimus concentrations at pre-dose (C0/dose) and 2-hour post dose (C2/dose) (Table 3). CYP3A5 expressers (CYP3A5*1 carriers) showed 2.3-fold lower C0/dose and C2/dose of tacrolimus compared to CYP3A5 non-expressers, who were CYP3A5*3 homozygotes (p<0.001). CYP3A4*1B, which is linked with CYP3A5*1, significantly decreased C0/dose (p=0.004) and C2/dose (p=0.003) of tacrolimus, while CYP3A4*22 did not have significant effects on them. No ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphisms affected C0/dose and C2/dose of tacrolimus. ABCB1 haplotypes did not appear to be a significant factor on tacrolimus dose normalized concentrations (data not shown). As for ABCC2 polymorphisms, 1249G>A significantly decreased C0/dose by 1.41-fold (p=0.011) and C2/dose by 1.59-fold (p=0.003), while 3972C>T significantly increased C0/dose by 1.33-fold (p=0.023) and C2/dose by 1.47-fold (p=0.012). ABCC2 −24C>T did not influence them. For further investigation of the effects of ABCC2 polymorphisms, haplotype analysis was carried out according to Laechelt et al.[18] As shown in Table 4, four haplotypes were determined: H1 (wild type, 54.4%), H2 (1249G>A, 20.6%), H9 (3972C>T, 12.3%) and H12 (−24C>T and 3972C>T, 12.7%). ABCC2 haplotype H2 is reported to have a higher protein expression and transport activity of MRP2, while haplotypes H9 and H12 are reported to have a lower protein expression and transport activity of MRP2 compared to wild type (haplotype H1).[18] Therefore, in the following study, the patients were divided into 3 groups according to ABCC2 haplotypes as follows: MRP2 high activity group (H2/H2 and H1/H2), MRP2 low activity group (H9/H9, H12/H12, H1/H9 and H1/H12) and MRP2 reference group (H1/H1, H2/H9 and H2/H12). Tacrolimus C0/dose and C2/dose in MRP2 high activity group were 1.54-fold and 1.80-fold lower than those in MRP2 low activity group and reference group (p=0.007 and p<0.001, respectively, Table 3). There were no significant differences in the concentrations between MRP2 low activity group and reference group. These results suggest that 1249G>A but not 3972C>T has a significant effect on the dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration. In CYP3A4*1B carriers, CYP3A5 expressers or MRP2 high activity group, significant higher tacrolimus doses were required compared to the other group, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2.

Allele frequencies of genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4, CYP3A5, ABCB1, ABCC2 and ABCG2 genes and ABCC2 haplotypes in 102 adult kidney transplant recipients.

| Gene | dbSNP | Position | Allele | Allele frequency | Genotype | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | rs2740574 | *1B | *1 | 0.892 | *1/*1 | 86 |

| *1B | 0.108 | *1/*1B | 10 | |||

| *1B/*1B | 6 | |||||

| rs35599367 | *22 | *1 | 0.966 | *1/*1 | 95 | |

| *22 | 0.034 | *1/*22 | 7 | |||

| *22/*22 | 0 | |||||

| CYP3A5 | rs776746 | *3 | *1 | 0.167 | *1/*1 | 8 |

| *3 | 0.833 | *1/*3 | 18 | |||

| *3/*3 | 76 | |||||

| ABCB1 | rs1128503 | 1236 | C | 0.554 | C/C | 36 |

| T | 0.446 | C/T | 41 | |||

| T/T | 25 | |||||

| rs2032582 | 2677 | G | 0.534 | G/G | 29 | |

| T | 0.451 | G/T | 48 | |||

| A | 0.015 | G/A | 3 | |||

| T/T | 22 | |||||

| rs1045642 | 3435 | C | 0.515 | C/C | 25 | |

| T | 0.485 | C/T | 55 | |||

| T/T | 22 | |||||

| ABCC2 | rs717620 | −24 | C | 0.873 | C/C | 78 |

| T | 0.127 | C/T | 22 | |||

| T/T | 2 | |||||

| rs2273697 | 1249 | G | 0.794 | G/G | 64 | |

| A | 0.206 | G/A | 34 | |||

| A/A | 4 | |||||

| rs3740066 | 3972 | C | 0.750 | C/C | 56 | |

| T | 0.250 | C/T | 41 | |||

| T/T | 5 | |||||

| ABCG2 | rs2231142 | 421 | C | 0.907 | C/C | 85 |

| A | 0.093 | C/A | 15 | |||

| A/A | 2 |

ABC adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, CYP cytochrome P450, dbSNP the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database

Table 3.

Effects of genetic polymorphisms on tacrolimus dose and dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration at pre-dose and 2-hour post-dose.

| Gene | SNP | Genotype | Dose (mg)

|

C0/dose (ng/mL/mg dose)

|

C2/dose (ng/mL/mg dose)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (25–75% Percentile) | P-value | N | Geometric Mean (95% CI) | P-value | N | Geometric Mean (95% CI) | P-value | ||||||

| CYP3A4 | *1B | *1/*1 | 86 | 4.0 | (3.0, 5.0) | <0.001††† | 85 | 2.50 | (2.22, 2.82) | 0.004†† | 81 | 4.49 | (3.91, 5.15) | 0.003†† |

| *1/*1B + *1B/*1B | 16 | 10.0 | (8.8, 12.0) | 16 | 1.23 | (0.80, 1.91) | 15 | 1.83 | (1.07, 3.12) | |||||

| *22 | *1/*1 | 95 | 5.0 | (3.5, 7.0) | 0.172 | 94 | 2.18 | (1.91, 2.51) | 0.213 | 89 | 3.82 | (3.24, 4.49) | 0.312 | |

| *1/*22 + *22/*22 | 7 | 4.0 | (3.5, 4.0) | 7 | 3.01 | (2.31, 3.91) | 7 | 5.16 | (3.41, 7.81) | |||||

| CYP3A5 | *3 | *1/*1 + *1/*3 | 26 | 8.5 | (3.0, 10.8) | <0.001††† | 26 | 1.20 | (0.94, 1.54) | <0.001††† | 24 | 2.09 | (1.46, 2.99) | <0.001††† |

| *3/*3 | 76 | 4.0 | (3.0, 5.0) | 75 | 2.77 | (2.46, 3.12) | 72 | 4.80 | (4.18, 5.53) | |||||

| ABCB1 | 1236C>T | C/C | 36 | 5.0 | (3.8, 8.0) | 0.440 | 36 | 2.11 | (1.63, 2.74) | 0.531 | 34 | 3.47 | (2.51, 4.81) | 0.320 |

| C/T + T/T | 66 | 4.0 | (3.3, 6.0) | 65 | 2.30 | (1.99, 2.66) | 62 | 4.16 | (3.53, 4.89) | |||||

| 2677G>T,A | G/G | 29 | 5.0 | (4.0, 10.0) | 0.064 | 29 | 2.07 | (1.49, 2.87) | 0.537 | 27 | 3.22 | (2.17, 4.77) | 0.203 | |

| G/T + G/A + T/T | 73 | 4.0 | (3.0, 6.0) | 72 | 2.30 | (2.02, 2.62) | 69 | 4.21 | (3.61, 4.90) | |||||

| 3435C>T | C/C | 25 | 5.0 | (4.0, 10.0) | 0.386 | 25 | 2.23 | (1.72, 2.90) | 0.994 | 24 | 3.53 | (2.62, 4.75) | 0.457 | |

| C/T + T/T | 77 | 4.0 | (3.0, 6.0) | 76 | 2.23 | (1.92, 2.60) | 72 | 4.03 | (3.36, 4.84) | |||||

| ABCC2 | −24C>T | C/C | 78 | 5.0 | (3.3, 6.0) | 0.873 | 77 | 2.20 | (1.87, 2.58) | 0.669 | 72 | 3.66 | (3.05, 4.38) | 0.147 |

| C/T + T/T | 24 | 4.0 | (3.8, 6.5) | 24 | 2.35 | (1.93, 2.85) | 24 | 4.74 | (3.53, 6.35) | |||||

| 1249G>A | G/G | 64 | 4.0 | (3.0, 6.0) | 0.020† | 64 | 2.53 | (2.19, 2.93) | 0.011† | 60 | 4.64 | (3.90, 5.52) | 0.003†† | |

| G/A + A/A | 38 | 5.0 | (4.0, 9.5) | 37 | 1.80 | (1.42, 2.29) | 36 | 2.92 | (2.22, 3.85) | |||||

| 3972C>T | C/C | 56 | 5.0 | (4.0, 7.3) | 0.235 | 55 | 1.96 | (1.60, 2.42) | 0.023† | 53 | 3.28 | (2.61, 4.11) | 0.012† | |

| C/T + T/T | 46 | 4.0 | (3.0, 5.8) | 46 | 2.61 | (2.28, 2.98) | 43 | 4.83 | (4.00, 5.84) | |||||

| Haplotype | Low + Reference | 71 | 4.0 | (3.0, 6.0) | 0.044† | 71 | 2.54 | (2.22, 2.90) | 0.007†† | 66 | 4.69 | (3.99, 5.51) | <0.001††† | |

| High | 31 | 5.0 | (4.0, 10.0) | 30 | 1.65 | (1.25, 2.19) | 30 | 2.60 | (1.92, 3.53) | |||||

| ABCG2 | 421C>A | C/C | 85 | 5.0 | (4.0, 6.0) | 0.094 | 84 | 2.15 | (1.89, 2.46) | 0.218 | 81 | 3.73 | (3.16, 4.41) | 0.193 |

| C/A + A/A | 17 | 4.0 | (2.0, 6.0) | 17 | 2.67 | (1.73, 4.11) | 15 | 4.93 | (3.26, 7.45) | |||||

One blood sample at pre-dose and 6 samples at 2-hour post-dose were not obtained among 102 patients. MRP2 high activity group includes H2/H2 and H1/H2; MRP2 low activity group includes H9/H9, H12/H12, H1/H9 and H1/H12); and MRP2 reference group includes H1/H1, H2/H9 and H2/H12. CYP, cytochrome P450.

ABC adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, CYP cytochrome P450, SNP Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001, significant difference between groups.

Table 4.

Frequencies of ABCC2 haplotypes in 102 adult kidney transplant recipients.

| Haplotype | −24 | 1249 | 3972 | Frequency | Diplotype | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | C | G | C | 0.544 | H1/H1 | 25 |

| H2 | C | A | C | 0.206 | H1/H2 | 27 |

| H9 | C | G | T | 0.123 | H1/H9 | 17 |

| H12 | T | G | T | 0.127 | H1/H12 | 17 |

| H2/H2 | 4 | |||||

| H2/H9 | 4 | |||||

| H2/H12 | 3 | |||||

| H9/H9 | 1 | |||||

| H9/H12 | 2 | |||||

| H12/H12 | 2 |

ABC adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette

Combined effects of CYP3A5*1 and ABCC2 haplotype on C0 and C2 of tacrolimus

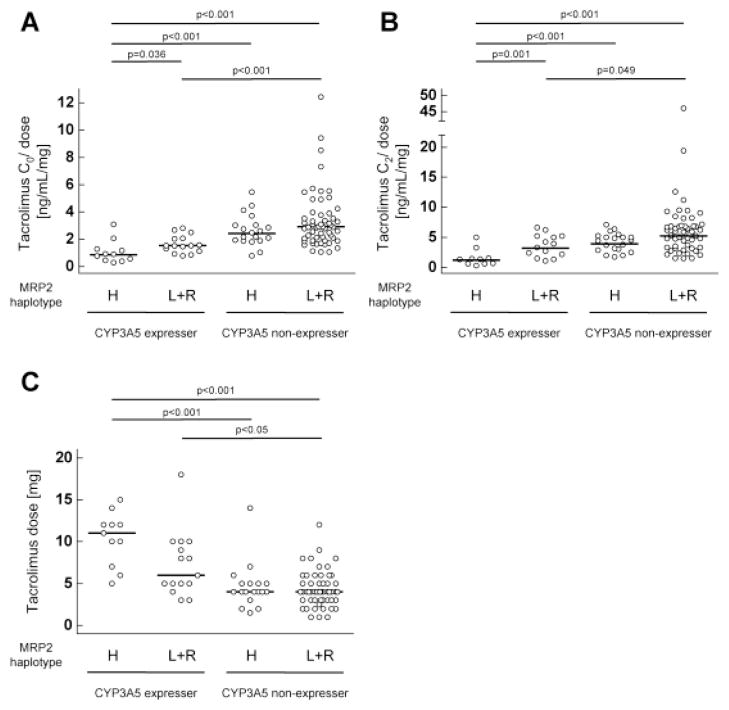

To investigate the combined effects of CYP3A5*1 and ABCC2 haplotype on C0/dose and C2/dose of tacrolimus, the patients were divided into 4 groups with respect to CYP3A5 expressers or non-expressers and MRP2 high activity group or low activity and reference group. CYP3A5 expressers with MRP2 high activity group showed a significant lower C0/dose and C2/dose of tacrolimus compared to other three groups (CYP3A5 expressers with MRP2 low activity + reference group, CYP3A5 non-expressers with MRP2 high activity group, CYP3A5 non-expressers with MRP2 low activity + reference group) (Fig. 1A–B). Tacrolimus dose in CYP3A5 expressers with MRP2 high activity group was significantly higher than that in CYP3A5 non-expressers with MRP2 high activity group or MRP2 low activity + reference group (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Combined effects of CYP3A5 polymorphism and ABCC2 haplotypes on dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration at pre-dose and 2-hour post-dose.

Dose-normalized trough concentrations (A), 2-hour post-dose concentrations (B) and dose (C) of tacrolimus in stable kidney transplant recipients separated according to CYP3A5 polymorphism (CYP3A5 expressers or non-expressers) and ABCC2 haplotypes (MRP2 high activity group (H) or low activity group (L) + reference group (R)). The bars show the geometric means of dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration (A and B) and the median of tacrolimus dose (C) in each group. CYP, cytochrome P450; MRP2, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2.

Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus

To understand the relative impacts of these polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus, population pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out. The pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus was best described using a 2-compartment model with first order absorption and an absorption lag time. Random effect parameters were estimated for the interindividual variability in apparent central volume of distribution (V1/F) and apparent clearance (CL/F). Residual variability was best described by a proportional model. The population pharmacokinetic parameters of the structural model were as follows: absorption rate constant (ka), 0.486 h−1; V1/F, 214 L; CL/F, 27.1 L/h; apparent peripheral volume of distribution (V2/F), 1863 L; apparent inter-compartmental clearance (Q/F), 68.7 L/h; and absorption lag time, 0.339 h.

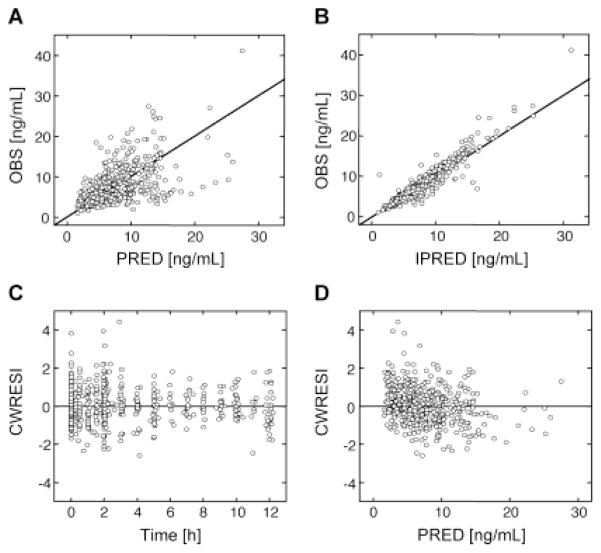

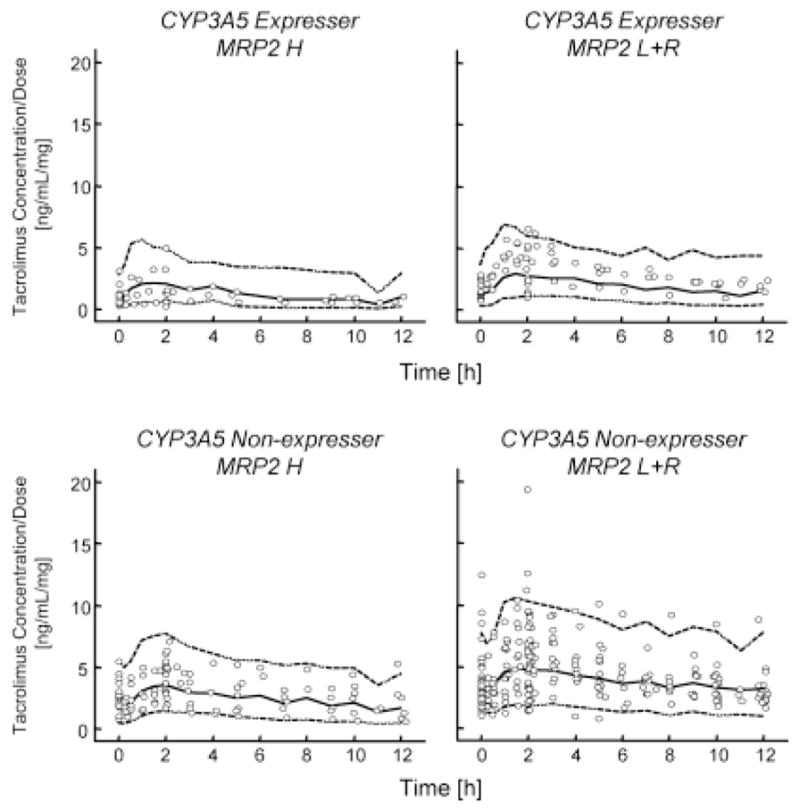

During the preliminary covariate screening (univariate analysis), CYP3A5 expressers, CYP3A4*1B carriers, MRP2 high activity group, Caucasian and age were found to be a significant covariate for CL/F (Table 5). We have previously reported slightly longer tacrolimus Tmax (time to reach the maximum blood concentration following drug administration) in the diabetic patients,[19] which is most likely due to the delayed gastric emptying.[20] Incorporation of diabetes into the model as a covariate for absorption lag time significantly reduced the objective function by 12.96. Therefore, diabetes was included in the following analysis. All the significant covariates were then included in the base model in a forward stepwise manner until there was no further reduction in the objective function. The full model included CYP3A5 expressers, MRP2 high activity group and age on CL/F and diabetes on the lag time. After backward elimination, they were still retained as covariates on CL/F and lag time. The covariates reduced interindividual variability from 66% to 44% for CL/F. CL/F was expressed as: CL/F = 20.7 × (Age/50) −0.78 × 2.03CYP3A5 × 1.40MRP2, where CYP3A5 = 0 for CYP3A5 non-expressers; CYP3A5 = 1 for CYP3A5 expressers; MRP2 = 0 for MRP2 low activity + reference group; MRP2 = 1 for MRP2 high activity group. The parameters of the final model, including bootstrap medians and 95% confidence intervals for the pharmacokinetic parameters, are presented in Table 6. Interindividual variability for V1/F and proportional error in the final model were 157% and 18%, respectively. Figures 2 and 3 present goodness-of-fit plots for the final model, and the visual predictive check for tacrolimus dose-normalized concentration, respectively. The visual predictive check (Figure 3) supports the finding that ABCC2 haplotype as well as CYP3A5 polymorphism significantly affected the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus.

Table 5.

Significant covariates for the univariate and multivariate analysis.

| Significant covariates | ΔMOFV | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Effect of CYP3A5 expressers on CL/F | −27.64 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of age on CL/F | −16.42 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of CYP3A4*1B carriers on CL/F | −12.95 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of MRP2 high activity group on CL/F | −11.45 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of Caucasian on CL/F | −7.24 | < 0.01 |

| Effect of diabetes mellitus on lag time | −12.96 | < 0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Effect of CYP3A5 expressers on CL/F | +37.02 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of MRP2 high activity group on CL/F | +10.02 | < 0.005 |

| Effect of age on CL/F | +22.42 | < 0.001 |

| Effect of diabetes mellitus on lag time | +25.69 | < 0.001 |

MOFV, minimum objective function value; CYP, cytochrome P450; CL/F, apparent oral clearance; MRP2, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2

Table 6.

Population pharmacokinetic parameters of tacrolimus and bootstrap validation.

| Model Parameter | Estimate (%RSE) | Bootstrap median (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| V1/F (L) | 234 (31.6) | 228 (99.2, 420) |

| CL/F (L/h) | 20.7 (6.77) | 20.3 (15.0, 23.2) |

| V2/F (L) | 1319 (41.9) | 1328 (574, 4141) |

| Q/F (L/h) | 70.7 (15.7) | 69.0 (40.2, 93.7) |

| ka (h−1) | 0.544 (25.8) | 0.539 (0.241, 1.20) |

| Lag time (h) | 0.183 (23.4) | 0.184 (0.102, 0.308) |

| Effect of CYP3A5 on CL/F | 2.03 (10.7) | 2.05 (1.62, 2.64) |

| Effect of MRP2 on CL/F | 1.40 (9.54) | 1.41 (1.15, 1.72) |

| Effect of age on CL/F | −0.780 (21.1) | −0.805 (−1.17, −0.480) |

| Effect of diabetes on lag time | 2.60 (23.9) | 2.61 (1.55, 4.91) |

| Random effects | ||

| Interindividual variability | ||

| V1/F (%) | 157 (24.9) | 156 (111, 197) |

| CL/F (%) | 43.9 (15.9) | 43.9 (36.4, 56.1) |

| Residual variability | ||

| Proportional error (%) | 18.4 (17.0) | 18.0 (15.1, 21.4) |

V1/F, apparent central volume of distribution after oral administration; CL/F, apparent oral clearance; V2/F, apparent peripheral volume of distribution after oral administration; Q/F, apparent inter-compartmental clearance; ka, absorption rate constant; CYP, cytochrome P450; MRP2, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2; RSE, relative standard error; CI, confidence interval

Fig. 2. Goodness of fit plots of the final model.

(A) Observed tacrolimus concentration (OBS) vs. population-predicted tacrolimus concentration (PRED), (B) OBS vs. individual-predicted tacrolimus concentration (IPRED), (C) conditional weighted residual with interaction (CWRESI) vs. time and (D) CWRESI vs. PRED.

Fig. 3. The visual predictive check for dose-normalized tacrolimus concentrations.

Comparison of observed dose-normalized tacrolimus concentrations with the 97.5th (upper dashed line), 50th (middle solid line) and 2.5th (lower dashed line) percentiles of the 1000 simulated datasets.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, it is demonstrated that genetic polymorphisms of CYP3A5 and ABCC2 affect the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. Dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration was 2.3-fold lower in CYP3A5 expressers than CYP3A5 non-expressers. In addition, population pharmacokinetic model showed that CL/F was 2-fold higher in CYP3A5 expressers than CYP3A5 non-expressers. There are numerous reports on a strong relationship between CYP3A5 polymorphism and tacrolimus pharmacokinetics in kidney, heart and liver transplant recipients,[7] which are consistent with the finding of the present study. Patients with MRP2 high activity, who is the homozygote of H2 (1249G>A) and the heterozygote of H2 and H1 (wild type), showed a significant lower dose-normalized concentration of tacrolimus compared to MRP2 low activity group and reference group. Furthermore, MRP2 high activity group was an independent covariate for CL/F of tacrolimus. Although 3972C>T had a significant effect on dose-normalized concentration of tacrolimus, haplotype analysis demonstrated that there is no difference in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics between the reference group and MRP2 low activity group, which included 3972C>T. This is probably due to the linkage disequilibrium in ABCC2 gene: 81% (30 out of 37) of the patient population that has at least one 1249G>A did not have 3972C>T. These results suggest that ABCC2 haplotypes, not each individual polymorphism, should be taken into account when characterizing the effects of ABCC2 polymorphisms on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics.

According to the routine practice of our transplant centre, tacrolimus doses are optimized to achieve a blood concentration of 10–12 ng/mL for the first 6 months and 4–6 ng/mL thereafter. CYP3A5 expressers have been reported to show a higher dose requirement compared to CYP3A5 non-expressers,[7] which is in accordance with our findings. Among CYP3A5 expressers, tacrolimus dose in MRP2 high activity group had the tendency to increase compared with MRP2 low activity and reference group although there was no significant difference (median [25th–75th percentiles]: 11.0 mg [8.5–12.0] and 6.0 mg [5.0–9.5], respectively). This finding suggests that characterization of ABCC2 haplotype as well as CYP3A5 genotype may be informative for adjusting tacrolimus dose in the early post-operative period. To evaluate the usefulness of ABCC2 haplotypes in dose adjustment of tacrolimus, further studies using much larger sample size are needed.

This is the first report on the significant influence of ABCC2 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. The association between ABCC2 polymorphism and tacrolimus concentrations was reported in only two studies in transplant recipients in Europe.[11, 21] A population pharmacokinetic approach of tacrolimus in pediatric transplant recipients did not identify ABCC2 polymorphism as a significant covariate.[11] Renders et al.,[21] in adult transplant recipients, found a combined effect of ABCC2 −24C>T and 1249G>A on tacrolimus trough concentration although there were no influences of individual ABCC2 polymorphisms. The discrepancies between the present study and the previous studies can be because of the difference in the environmental factor or the ratio of ethnic groups and diabetes among the transplant recipients. Further studies are needed to confirm the effects of ABCC2 polymorphisms on the tacrolimus disposition.

The mechanism underlying the effect of ABCC2 haplotype on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics is not known. It was recently shown that erythromycin is a substrate for human MRP2.[22, 23] Erythromycin is another macrolide lactone with comparable physicochemical properties to tacrolimus (molecular weight, LogP, topological polar surface area). The metabolism of erythromycin via CYP3A4 was increased in Mrp2 knockout mice and human carrying ABCC2 −24C>T, suggesting the interplay between the metabolism and MRP2.[23] It was suggested that the metabolites of tacrolimus are substrates of other transporters than P-gp.[12] We hypothesize that tacrolimus metabolites or tacrolimus are substrates for MRP2. Thus, MRP2 may be involved in the clearance of tacrolimus in cooperation with CYP3A in the small intestine. Further in vitro studies are warranted to elucidate the transport of tacrolimus and its metabolites via MRP2.

Although CYP3A4*1B significantly reduced the dose-normalized tacrolimus concentration, CYP3A4*1B was not the covariate for any parameters in population pharmacokinetic model. This could be because of a possible linkage between CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A5*1. The frequencies of most of SNPs except for CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A5*3 perfectly agree with those predicted by the Hardy-Weinberg equation. As for CYP3A5*3, Hardy-Weinberg equation predicts *1/*1: n=3 (observed: n=8), *1/*3: n=28 (observed: n=18), *3/*3: n=71 (observed: n=76). This discrepancy is because there is the ethnic difference in the allele frequency of CYP3A5*3 (Caucasian: 91.1%; Hispanic: 75.0%; African-American: 45.5%) and because the ratios of ethnic group were different in our population (73 Caucasian, 14 Hispanic, 11 African-American, 4 others). In this study, we have observed that 81% of the patient population that express at least one CYP3A4*1B allele are also expressing a functional CYP3A5. Our finding that CYP3A4*1B does not have an independent effect on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics is consistent with the previous result.[24] Elens et al.[25] have reported that CYP3A4*22 was associated with reduced tacrolimus clearance. In this study, dose-normalized concentration of tacrolimus in CYP3A4*1/*22 had the tendency to increase compared with CYP3A4*1/*1, but this difference was not significant. This might be because allele frequency of CYP3A4*22 is low and our sample size (n=102) was not enough to evaluate the effect of CYP3A4*22 on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. There were no linkage between CYP3A4*22 and CYP3A5*1 or CYP3A4*1B. Further studies are needed to elucidate the contribution of CYP3A4*22 on the disposition of tacrolimus. ABCB1 1236C>T, 2677G>T, A and 3435C>T and ABCG2 421C>A had no effects on dose-normalized concentration and any population pharmacokinetic parameters of tacrolimus in this study. Influences of ABCB1 polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus are still controversial, but most studies have failed to find an association between them.[7]

The values of the population pharmacokinetic parameters of tacrolimus in this study are comparable to the values reported previously.[26–29] Age was also identified as a covariate for CL/F and the model demonstrated that the apparent clearance of tacrolimus decreases with age. Older age is reported to be associated with higher tacrolimus dose-normalized concentration or lower tacrolimus dose requirement,[30–32] which is in accordance with our finding. Diabetes significantly reduced the objective function by 12.96 as a covariate for an absorption lag time. Patients with long-term diabetes exhibit delayed gastric emptying due to diabetes-induced autonomic neuropathy that may affect the rate of drug absorption.[20] This result support the longer Tmax of tacrolimus in diabetic patients.[19]

Similar to cyclosporine, tacrolimus is highly bound to red blood cells, and the reduced binding to blood cells or plasma proteins increases the values of unbound fraction and apparent clearance.[33, 34] Tacrolimus apparent clearance was higher in patients with low hematocrit levels (< 33 or 35%) as compared to those with normal hematocrit levels.[11, 29, 34, 35] However, in the current study, hematocrit levels did not have any significant influence on tacrolimus CL/F. This discrepancy might be because there were a few patients with low hematocrit levels in our study (only 12 patients have lower hematocrit levels than 35%). Xue et al.[36] reported no effects of hematocrit on tacrolimus clearance in healthy volunteers with normal hematocrit levels, which is consistent with our results.

CONCLUSIONS

ABCC2 haplotype as well as CYP3A5 polymorphism have significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. These findings suggest that MRP2 is involved in the efflux of tacrolimus or its metabolites into the lumen in cooperation with CYP3A in the small intestine. Determination of ABCC2 as well as CYP3A5 genotype may be useful for more accurate tacrolimus dosage adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded in part by R15 GM101599 from National Institutes of Health. Some of the work was conducted at the Rhode Island Genomics and Sequencing Center which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (MRI Grant DBI-0215393 and EPSCoR Awards 0554548 & 1004057), the US Department of Agriculture (Grants 2002-34438-12688, 2003-34438-13111 & 2008-34438-19246), and the University of Rhode Island.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Halloran PF. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 23;351( 26):2715–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43( 10):623–53. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott LJ, McKeage K, Keam SJ, et al. Tacrolimus: a further update of its use in the management of organ transplantation. Drugs. 2003;63( 12):1247–97. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sattler M, Guengerich FP, Yun CH, et al. Cytochrome P-450 3A enzymes are responsible for biotransformation of FK506 and rapamycin in man and rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992 Sep-Oct;20(5):753–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampen A, Christians U, Guengerich FP, et al. Metabolism of the immunosuppressant tacrolimus in the small intestine: cytochrome P450, drug interactions, and interindividual variability. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995 Dec;23( 12):1315–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeki T, Ueda K, Tanigawara Y, et al. Human P-glycoprotein transports cyclosporin A and FK506. J Biol Chem. 1993 Mar 25;268( 9):6077–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staatz CE, Goodman LK, Tett SE. Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin inhibitors: Part I. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010 Mar;49( 3):141–75. doi: 10.2165/11317350-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, et al. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet. 2001 Apr;27( 4):383–91. doi: 10.1038/86882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hustert E, Haberl M, Burk O, et al. The genetic determinants of the CYP3A5 polymorphism. Pharmacogenetics. 2001 Dec;11( 9):773–9. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukudo M, Yano I, Masuda S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenomic analysis of tacrolimus in pediatric living-donor liver transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Oct;80( 4):331–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W, Elie V, Roussey G, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of tacrolimus in de novo pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Dec;86( 6):609–18. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christians U, Jacobsen W, Benet LZ, et al. Mechanisms of clinically relevant drug interactions associated with tacrolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41( 11):813–51. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampen A, Christians U, Gonschior AK, et al. Metabolism of the macrolide immunosuppressant, tacrolimus, by the pig gut mucosa in the Ussing chamber. Br J Pharmacol. 1996 Apr;117( 8):1730–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takano M, Yumoto R, Murakami T. Expression and function of efflux drug transporters in the intestine. Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Jan;109( 1–2):137–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chitnis SD, Ogasawara K, Schniedewind B, et al. Concentration of tacrolimus and major metabolites in kidney transplant recipients as a function of diabetes mellitus and cytochrome P450 3A gene polymorphism. Xenobiotica. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2012.752118. EPub 2013 Jan 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He P, Court MH, Greenblatt DJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype associations of cytochrome P450 3A4 and 3A5 polymorphism with midazolam clearance in vivo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005 May;77( 5):373–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, et al. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jan 15;21( 2):263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laechelt S, Turrini E, Ruehmkorf A, et al. Impact of ABCC2 haplotypes on transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene regulation and function. Pharmacogenomics J. 2011 Feb;11( 1):25–34. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendonza AE, Zahir H, Gohh RY, et al. Tacrolimus in diabetic kidney transplant recipients: pharmacokinetics and application of a limited sampling strategy. Ther Drug Monit. 2007 Aug;29( 4):391–8. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31811f319b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz M, Fraser R. Disordered gastric motor function in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1994 Jun;37( 6):543–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00403371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renders L, Frisman M, Ufer M, et al. CYP3A5 genotype markedly influences the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus and sirolimus in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Feb;81( 2):228–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hariharan S, Gunda S, Mishra GP, et al. Enhanced corneal absorption of erythromycin by modulating P-glycoprotein and MRP mediated efflux with corticosteroids. Pharm Res. 2009 May;26( 5):1270–82. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franke RM, Lancaster CS, Peer CJ, et al. Effect of ABCC2 (MRP2) transport function on erythromycin metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011 May;89( 5):693–701. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hesselink DA, van Schaik RH, van Agteren M, et al. CYP3A5 genotype is not associated with a higher risk of acute rejection in tacrolimus-treated renal transplant recipients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008 Apr;18( 4):339–48. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f75f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elens L, Bouamar R, Hesselink DA, et al. A new functional CYP3A4 intron 6 polymorphism significantly affects tacrolimus pharmacokinetics in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Chem. 2011 Nov;57( 11):1574–83. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musuamba FT, Mourad M, Haufroid V, et al. Time of drug administration, CYP3A5 and ABCB1 genotypes, and analytical method influence tacrolimus pharmacokinetics: a population pharmacokinetic study. Ther Drug Monit. 2009 Dec;31( 6):734–42. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181bf8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benkali K, Prémaud A, Picard N, et al. Tacrolimus population pharmacokinetic-pharmacogenetic analysis and Bayesian estimation in renal transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48( 12):805–16. doi: 10.2165/11318080-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woillard JB, de Winter BC, Kamar N, et al. Population pharmacokinetic model and Bayesian estimator for two tacrolimus formulations--twice daily Prograf and once daily Advagraf. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Mar;71( 3):391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musuamba FT, Mourad M, Haufroid V, et al. A Simultaneous D-Optimal Designed Study for Population Pharmacokinetic Analyses of Mycophenolic Acid and Tacrolimus Early After Renal Transplantation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Dec;52( 12):1833–43. doi: 10.1177/0091270011423661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson PA, Oetting WS, Brearley AM, et al. Novel polymorphisms associated with tacrolimus trough concentrations: results from a multicenter kidney transplant consortium. Transplantation. 2011 Feb 15;91( 3):300–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318200e991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson PA, Schladt D, Oetting WS, et al. Lower calcineurin inhibitor doses in older compared to younger kidney transplant recipients yield similar troughs. Am J Transplant. 2012 Dec;12( 12):3326–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratta P, Quaglia M, Cena T, et al. The interactions of age, sex, body mass index, genetics, and steroid weight-based doses on tacrolimus dosing requirement after adult kidney transplantation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 May;68( 5):671–80. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akhlaghi F, Ashley J, Keogh A, et al. Cyclosporine plasma unbound fraction in heart and lung transplantation recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 1999 Feb;21( 1):8–16. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahir H, McLachlan AJ, Nelson A, et al. Population pharmacokinetic estimation of tacrolimus apparent clearance in adult liver transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2005 Aug;27( 4):422–30. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000170029.36573.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staatz CE, Willis C, Taylor PJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002 Dec;72( 6):660–9. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue L, Zhang H, Ma S, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of tacrolimus in healthy Chinese volunteers. Pharmacology. 2011;88( 5–6):288–94. doi: 10.1159/000331856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]