Abstract

Septin 9 isoform 1 (SEPT9_i1) protein associates with hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α to augment HIF-1 transcriptional activity. The first 25 amino acids of SEPT9_i1 (N25) are unique compared with other members of the mammalian septin family. This N25 domain is critical for HIF-1 activation by SEPT9_i1 but not essential for the protein-protein interaction. Here, we show that expression of N25 induces a significant dose-dependent inhibition of HIF-1 transcriptional activity under normoxia and hypoxia without influencing cellular HIF-1α protein levels. In vivo, N25 expression inhibits proliferation, tumor growth and angiogenesis concomitant with decreased expression levels of intratumoral HIF-1 downstream genes. Depletion of endogenous SEPT9_i1 or the exogenous expression of N25 fragment reduces nuclear HIF-1α levels accompanied by reciprocal accumulation of HIF-1α in the cytoplasm. Mechanistically, SEPT9_i1 binds to importin-α through N25 depending on its bipartite nuclear localization signal, to scaffold the association between HIF-1α and importin-α, which leads to facilitating HIF-1α nuclear translocation. Our data explore a new and a previously unrecognized role of a septin protein in the cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation process. This new level in the regulation of HIF-1α translocation is critical for efficient HIF-1 transcriptional activation that could be targeted for cancer therapeutics.

Keywords: HIF-1α, SEPT9_i1, importin-α, nuclear translocation

Introduction

Mammalian septins are a family of GTP-binding proteins evolutionarily conserved with roles in multiple core cellular functions. The increasingly accumulating data from studies on mammalian septins suggest that septin heteromeric complexes provide higher-order structures that can act as scaffolds of docking sites for other proteins important in key cellular processes. There are 13 genes encoding both ubiquitous and tissue-specific septins.1 SEPT9 has been identified as a potential oncogene, and its amplification and/or overexpression was observed in several carcinomas, including breast,2-4 ovarian,5,6 head and neck,7,8 and prostate.9

We had previously identified SEPT9_i1, a product of transcript SEPT9_v1 that encodes isoform 1 with the largest N-terminal extension, as a positive regulator in the hypoxic pathway. SEPT9_i1 interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), the oxygen-regulated subunit of HIF-1, which is a key regulator of the hypoxic response pathway. The interaction is specific to HIF-1α, but not to HIF-2α, and it increases HIF-1α protein stability as well as HIF-1 transcriptional activity, leading to enhanced proliferation, tumor growth, and angiogenesis.9 HIF transcription factors are members of the basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim transcription factor family.10 Most human cancers exhibit permanent or transient hypoxia.11 Hypoxia has a major role in cancer progression and angiogenesis.12-14 The main mechanism in mediating adaptive responses to hypoxia is the regulation of transcription by HIFs.15,16

The first 25 amino acids of SEPT9_i1 protein (N25) are uniquely different from any other member of the overall septin family. This N25 domain contains a putative bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 1A). N25 was found critical for HIF-1 activation by SEPT9_i1, while it was not required for the protein-protein interaction.9 Because N25 plays an important role in mediating HIF-1 activation by SEPT9_i1, we therefore aimed to further investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms of this activation. Herein, we report that expression of N25 fragment induced a significant dose-dependent inhibition of HIF-1 transcriptional activity in vitro as well as inhibition of cell proliferation, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in vivo. Mechanistically, N25 inhibited HIF-1α cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation through interference of the interactions between HIF-1α and SEPT9_i1 with importin-α. We believe this new level in the regulation of HIF-1α translocation is critical for efficient HIF-1 transcriptional activation that could be targeted for cancer therapeutics.

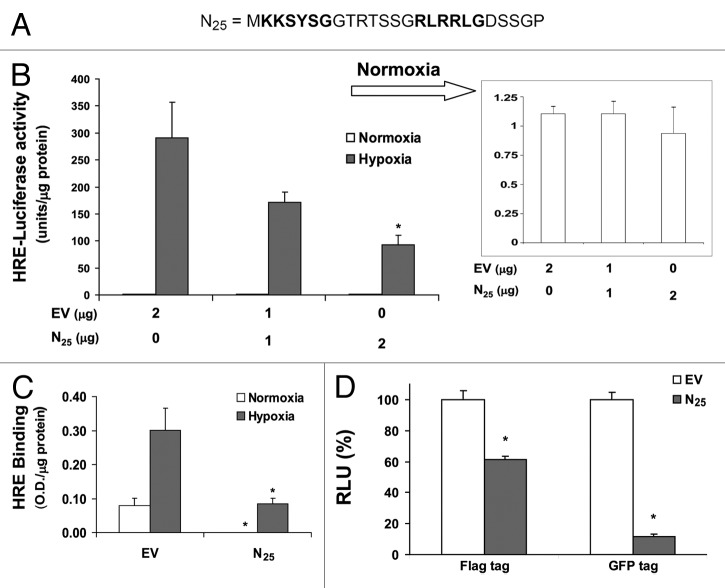

Figure 1. Expression of SEPT9_i1 N25 polypeptide inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity. (A) SEPT9 isoform 1 (SEPT9_i1) unique N25 sequence is outlined and the putative bipartite NLS is marked in bold. (B) HEK 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with increasing amounts of Flag-tagged N25 or empty vector (EV) with vector-expressing luciferase under the control of HRE. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were subjected overnight to normoxia or hypoxia and then analyzed by luciferase luminescence assay. Relative luciferase activity, units/μg protein at each assay point. Normoxia results are presented in the inset. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SD *p < 0.05 compared with hypoxia of EV. (C) PC-3 cells transiently transfected with Flag-N25 or EV. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were subjected overnight to normoxia or hypoxia and nuclear extracts were then prepared and analyzed for HRE binding using TansFac kit. Activity (O.D.) was normalized to the protein amount at each assay point (O.D./µg protein). Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SD; *P < 0.05 compared with normoxia and hypoxia of EV, respectively. (D) HEK 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with Flag-N25 or GFP-tagged N25 and their respective EVs together with the HRE-luciferase reporter plasmid. After 24 h, the cells were subjected overnight to hypoxia. Relative luciferase activity (RLU) units/mg protein at each assay point was normalized (%) to the respective EV. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SD; *P < 0.05 compared with EV.

Results

Expression of SEPT9_i1 N25 polypeptide inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity

To evaluate the functional consequences of N25 on HIF-1 transcriptional activity, the corresponding sequence of N25 domain (Fig. 1A) was constructed into an expressing vector to encode Flag-tagged N25 on its N terminus (Flag-N25). HEK 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with Flag-N25 and a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of hypoxia-response elements (HREs) from the VEGF promoter (Fig. 1B). The cells were subsequently grown under normoxia or exposed to hypoxia. Expression of escalating amounts of Flag-N25 induced a significant dose-dependent inhibition of HIF-1 transcriptional activity under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1B). HIF-1 transcriptional activity was almost undetectable in these cells under normoxic conditions (Fig. 1B, inset). To confirm that the effect of Flag-N25 is not a result of different transfection efficiency, HEK 293T and PC-3 cells were subsequently subjected to dual luciferase reporter assay using the firefly HRE-luciferase and an SV40-dependent renilla luciferase (Fig. S1). After normalization to renilla luciferase activity, still a significant reduction in HIF-1 transcriptional activity was observed in both cells (Fig. S1). We also used another assay to determine HIF-1 transcriptional activity, the TransFactor ELISA-based HRE binding assay (Fig. 1C). PC-3 cells were transfected with Flag-N25, and nuclear extracts were prepared for HRE-binding assay. A significant inhibition in HRE binding capacity by HIF-1 was seen under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1C). Because Flag-N25 is a relatively short polypeptide whose detection by western blot was difficult, PC-3 and MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with SEPT9_i1 in the presence and absence of Flag-N25 and then metabolically labeled with 35S-methionine (Fig. S2). The cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-SEPT9_i1 antibodies, originally directed against the N25 domain9 and analyzed by autoradiography. The immunoprecipitated amount of SEPT9_i1 was substantially reduced in the presence of Flag-N25 in both cancer cells, indicating that there was a direct competition between full-length SEPT9_i1 and Flag- N25 (Fig. S2). N25 was constructed with a GFP tag on its C terminus and transiently cotransfected into HEK 293T cells to further confirm the inhibitory effects of N25 on HIF-1 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1D). N25-GFP also inhibited HIF-1 transcriptional activity to an even greater extent compared with Flag-N25 (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that expression of the N25 fragment inhibited HIF-1 transcriptional activity.

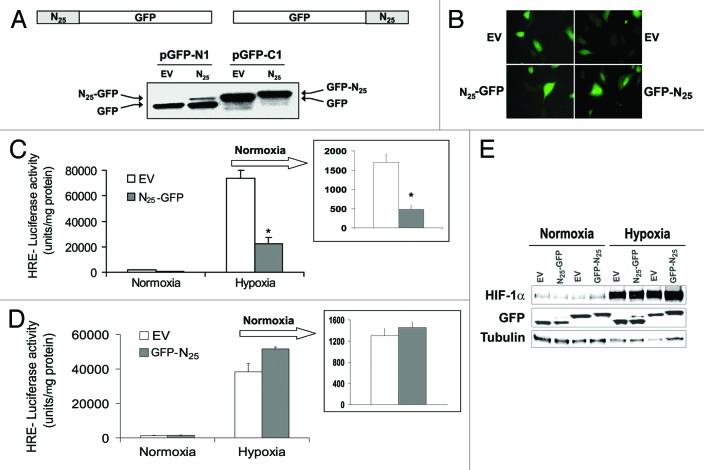

We designed PC-3 cells to stably express N25 to study the biological consequences of N25 expression in greater detail. GFP tagging to N25 was chosen, since it was more active and easier for detection by immunoblotting and fluorescence microscopy. N25 was constructed into retroviral vectors pRetroQ-AcGFP1-N1 (N25-GFP) and pRetroQ-AcGFP1-C1 (GFP-N25) to fuse GFP either on the C terminus or on the N terminus of N25, respectively (Fig. 2A). After retroviral infection, PC-3 cells were analyzed for GFP-tagged N25 expression by western blotting (Fig. 2A) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2B). Infected PC-3 cells were shown to stably express N25-GFP and GFP-N25 chimeras (Fig. 2A and B). While GFP-N25 chimera ran as a single band higher than the GFP as expected, N25-GFP ran as 2 separate bands, the higher one corresponding to the full-length chimera and the lower one corresponding to a “spontaneously” cleaved GFP (Fig. 2A). Live-cell imaging showed that GFP-N25 was predominantly located in the nucleus unlike N25-GFP, which was diffusely distributed in the cell (Fig. 2B). The unique N25 sequence contains a putative bipartite NLS as illustrated in Figure 1A, which may explain the accumulation of GFP-N25 stable chimera in the nucleus. The cells were transiently transfected with HRE reporter plasmid and grown under normoxia and hypoxia in order to assess HIF-1 transcriptional activity in PC-3 cells stably expressing GFP-tagged N25. Expression of N25-GFP significantly decreased HIF-1 transcriptional activity by more than 50% compared with control under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, expression of GFP-N25 did not decrease HIF-1 transcriptional activity (Fig. 2D). These results imply that the addition of GFP on the N terminus of N25 interferes with its action on HIF-1. In contrast to the inhibitory effects of N25-GFP on HIF-1 transcriptional activity, the expression levels of cellular HIF-1α protein were only modestly changed (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. GFP position in N25 polypeptide was critical for inhibition of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. N25 was tagged with GFP on either its C terminus or N terminus using the retroviral vector pGFP1-N1 or pGFP1-C1, respectively. Together with their respective empty vectors (EVs), were infected into PC-3 cells to stably express GFP-tagged N25 or GFP only. The cells were analyzed (A) by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody or (B) by fluorescent microscopy (×40). (C) PC-3 cells expressing N25-GFP or (D) GFP-N25 and their respective EVs were transiently transfected with the HRE-luciferase reporter plasmid. After 24 h, the cells were subjected overnight to hypoxia or normoxia. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SD; *P < 0.05 compared with EV. Normoxia results are presented in the inset. (E) PC-3 cell stably expressing GFP-tagged N25 were grown under normoxia or hypoxia. After 16 h, cells were harvested and whole cellular extracts were prepared, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibodies to HIF1α, GFP, and tubulin.

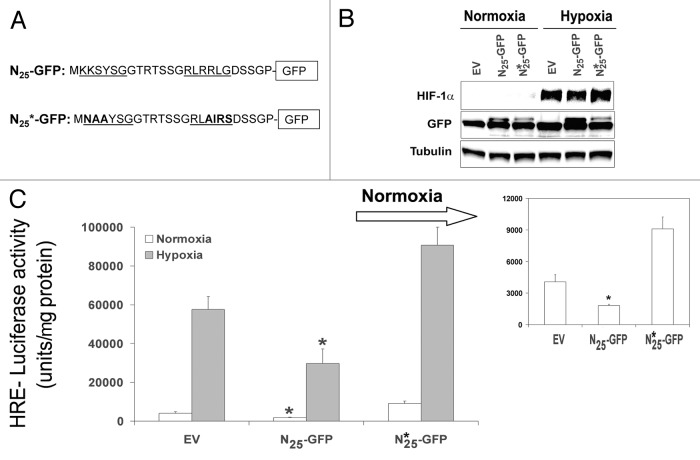

To test whether the inhibitory effect of N25-GFP on HIF-1 activity is dependent on the NLS sequence, it was mutated to NAARIS sequence to keep flexibility and minimize generalized conformational disruption as a result of the substitutions.17 First we mutated each NLS sequence at a time, but it did not significantly affect HIF-1 activation (data not shown), therefore we next double mutated both bipartite NLS sequences (Fig. 3A). Expression of NLS mutated N25 (N25*-GFP) chimera did not affect either HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 3B) or HIF-1 transcriptional activity compared with wild-type N25-GFP (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results showed that the active N25 fragment reduced HIF-1 transcriptional activation without affecting cellular HIF-1α protein expression levels, and that this effect is dependent on the N25 NLS domain.

Figure 3. Mutation in the N25-GFP NLS (N25*-GFP) abrogates its inhibition on HIF-1 transcriptional activity. (A) N25-GFP NLS residue was mutated by side directed mutagenesis as indicated. (B) The N25*-GFP expression was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibody to GFP, HIF-1α, and tubulin. (C) Mutated N25*-GFP was infected into PC-3 cells. The stably infected PC-3 cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing luciferase under the control of HRE and grown under normoxia and hypoxia. Relative luciferase activity was normalized to the protein amount at each assay point. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, ± SD; *P < 0.05.

N25-GFP inhibits cell proliferation, tumor growth and angiogenesis

We hypothesized that reducing HIF-1 transcriptional activity by N25 would directly or indirectly influence the biological fate of cancer cells. We therefore examined the effects of N25 expression on cell proliferation. In vitro, the proliferation rate of PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP was significantly reduced compared with control cells (Fig. 4A), while the proliferation rate of PC-3 cells stably expressing GFP-N25 was similar to that of control cells (Fig. S3A). In addition, N25*-GFP stably infected cells proliferation rate was also not reduced compared with control (Fig. S3B).

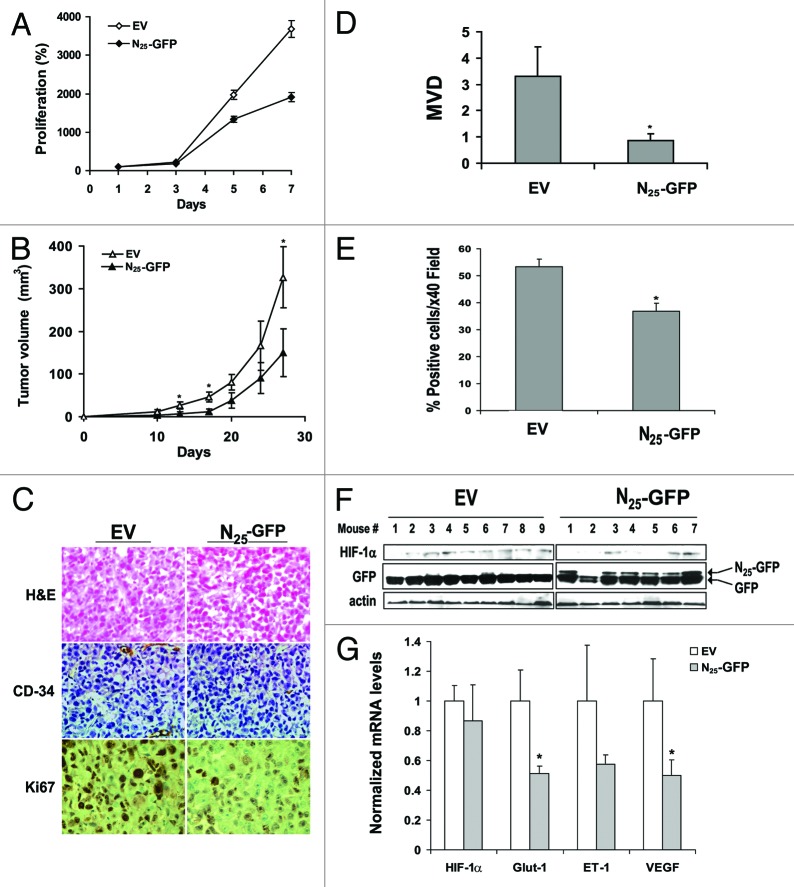

Figure 4. Expression of N25-GFP decreased proliferation, tumor growth and angiogenesis. (A) PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP or empty vector (EV) were grown in 96-well plates and analyzed for XTT proliferation assay. Proliferation was expressed as increase in percentage of the initial absorbance that was measured 24 h after seeding (100%). Growth media were not changed until the end of the experiment. Points, mean (n = 6); bars, SD; *P < 0.001. (B) PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP or EV were implanted (2 x 106) subcutaneously into the hinds of athymic nude mice. Tumor volume was monitored. Points, mean (n = 7 EV, n = 9 N25); bars, SE; *P < 0.05. (C) Tumor sections from EV and N25 tumors were stained with H&E (×20; upper panels) and immunostained with anti-CD34 (×20; middle panels) and anti-Ki67 (×40; lower panels). (D) Microvessel density (MVD) was determined in 5 paraffin-embedded tumor sections from each animal per group. Columns, average of the means of MVD from each animal; bars, SE; *P = 0.03. (E) Ki67 staining (%) was quantified by dividing the number of positive nuclei by the number of total nuclei in a ×40 magnification field multiplied by 100. Samples consisted from 5 paraffin-embedded tumor sections from each animal per group. Columns, average of the means of Ki67 staining from each animal; bars, SE; *P < 0.001. (F) Protein extracts were purified from xenograft tumors of each group and analyzed by western blotting using antibodies to HIF-1α, GFP, and actin. (G) Total RNA was isolated from 4 representative xenograft tumors of each group and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using primers specific to HIF-1α, Glut-1, ET-1, and VEGF. The results were normalized to actin mRNA expression levels, and the mean induction of each gene was normalized to EV. Columns, mean (n = 2); bars, SD; *P < 0.05.

In vivo, using a xenograft model, PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP-derived tumors showed significant retardation in the tumor formation rate compared with the controls and reached an average of a 2-fold smaller tumor volume (Fig. 4B). Another xenograft model consisting either of PC-3 cells stably expressing the inactive GFP-N25 or of empty vector control cells did not show any inhibitory effects on tumor growth rate or tumor volume (Fig. S4). After the animals were sacrificed, the tumors were excised and analyzed by immunohistochemical staining with CD-34 and Ki67 antibodies (Fig. 4C). Tumors derived from N25-GFP cells exhibited a significant reduction in microvessel density, as quantified by CD-34 staining, compared with control tumors (Fig. 4D). To exclude the possibility that the difference in MVD was a result of the fact that the tumors excised from mice from each group were notably of different sizes, we analyzed tumors for MVD with the same volume. Again, the MVD in N25-GFP tumors was significantly less than in the control tumors (Table 1). In addition, N25-GFP tumors also showed a significant reduction in intratumoral cell proliferation, as measured by Ki67 staining (Fig. 4E). Western blot analysis of tumor extracts did not show statistically significant lower HIF-1α protein expression levels in N25-derived tumors compared with control tumors (Fig. 4F). A quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of RNA extracted from the tumors showed that while the expression level of HIF-1α transcript was almost equal in both groups, the levels of selected HIF-target genes transcript, including Glut-1, ET-1, and VEGF, were decreased in N25 tumors compared with control tumors (Fig. 4G). Together, these in vitro and in vivo data indicated that N25-GFP reduced cell proliferation, tumor growth, and angiogenesis of prostate cancer cells.

Table 1. MVD analysis of tumors with equal volume derived from N25-GFP cells and control cells.

| MVD | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor volume (mm3) |

EV |

N25-GFP |

| 400 |

0.4 |

0.29 |

| 500 |

1.63 |

0.3 |

| 700 |

1.36 |

0.4 |

| 900 |

2.33 |

0.13 |

| Average ± SD |

1.43 ± 0.8 |

0.28 ± 0.1 |

| P value | 0.029 | |

MVD, microvessel density; EV, empty vector.

Expression of N25 reduces HIF-1α nuclear translocation

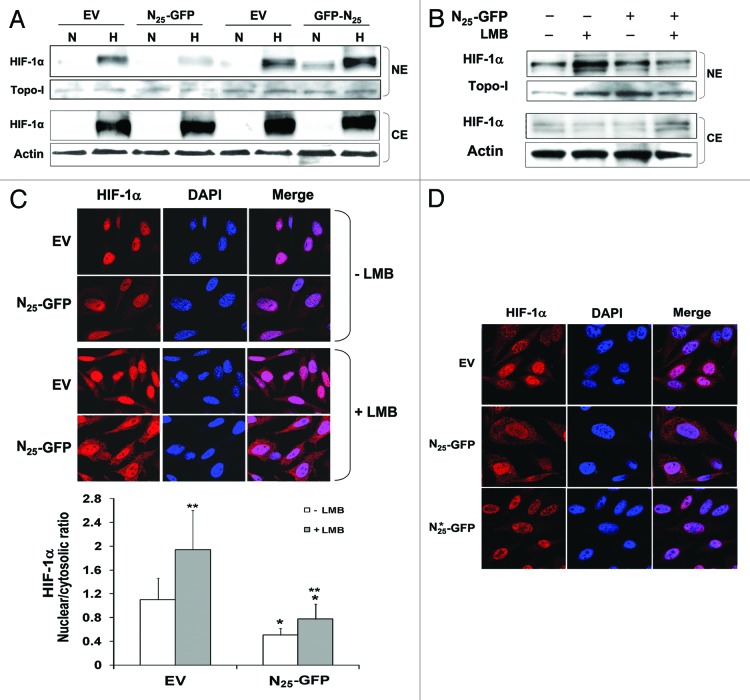

Since N25 significantly decreases HIF-1 transcriptional activity but does not change total cellular HIF-1α levels, we hypothesized that N25 can affect HIF-1α’s subcellular localization. We assessed the subcellular localization of HIF-1α by using both biochemical fractionation and laser scanning confocal microscopy. Nuclear and cytosolic extracts were prepared from PC-3 cells grown under normoxia and hypoxia and analyzed by western blotting (Fig. 5A). HIF-1α nuclear accumulation was observed upon hypoxic exposure in the empty vector controls as well as in cells expressing GFP-N25, while it was reduced in cells expressing N25-GFP only (Fig. 5A). We utilized a specific inhibitor of the principal mammalian CRM1-mediated nuclear protein export pathway, leptomycin B (LMB), to further test the hypothesis that N25-GFP may influence HIF-1α cytoplasmic-nuclear trafficking. PC-3 cells were treated with LMB, grown under hypoxia and analyzed by western blotting (Fig. 5B). HIF-1α nuclear accumulation was more pronounced in the control cells, while it was significantly reduced in the cells expressing N25-GFP (Fig. 5B). Moreover, LMB-treated PC-3 cells grown under hypoxia were also immunostained with antibodies against HIF-1α (Fig. 5C). As expected, HIF-1α staining was restricted to the nucleus in the presence of LMB under hypoxic conditions in the control cells, while it was also present in the cytoplasm in cells expressing N25-GFP (Fig. 5C). Dentsitometric quantification of HIF-1α fluorescent levels showed a significant decrease (50–60%) in HIF-1α nuclear/cytosolic ratio by N25-GFP (Fig. 5C, lower panel). In addition, accumulation of nuclear HIF-1α in the presence of LMB was significantly impaired by N25-GFP compared with control cells (Fig. 5C, lower panel). To further investigate the importance of the N25 NLS residue in HIF-1α translocation, the stably infected mutated N25*-GFP cells were treated with LMB, grown under hypoxia, and immunostained with antibodies against HIF-1α (Fig. 5D). HIF-1α expression in N25*-GFP cells was predominantly in the nucleus as was observed in the control cells (Fig. 5D). These findings suggest that N25, depending on its NLS, reduced HIF-1α translocation to the nucleus by interfering with the HIF-1α nuclear import process.

Figure 5. N25-GFP reduced HIF-1α nuclear translocation. (A) PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP and GFP-N25 and their empty vectors (EVs), pGFP-N1 and pGFP-C1, respectively, were grown under normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 4 h. Nuclear and cytosolic extracts were then prepared, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibodies to HIF-1α,Topo-I and actin, respectively. PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP and the corresponding EV were exposed to 6 h hypoxia in the presence or absence of 20 nM leptomycin B (LMB). Cells were either (B) subjected to nuclear and cytosolic extracts preparation and analysis by immunoblotting with antibodies to HIF-1 α, Topo-I and actin, respectively or (C) fixed and processed for immunofluorescence labeling with anti-HIF-1α antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). Staining was analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscope (magnification ×63). Lower panel, densitometric quantification of HIF-1α fluorescent signal of each cell from 4 different fields. The mean of nuclear/cytosolic ratio was plotted against the different conditions. *P < 0.001 N25-GFP compared with corresponding EV; **P < 0.01 LMB compared with no LMB. (D) PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP, mutated N25*-GFP or empty vector (EV) were exposed to 6 h hypoxia in the presence of 20 nM LMB. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence as in (C) (magnification ×63).

N25 disrupts SEPT9_i1 and HIF-1α interaction with importin-α

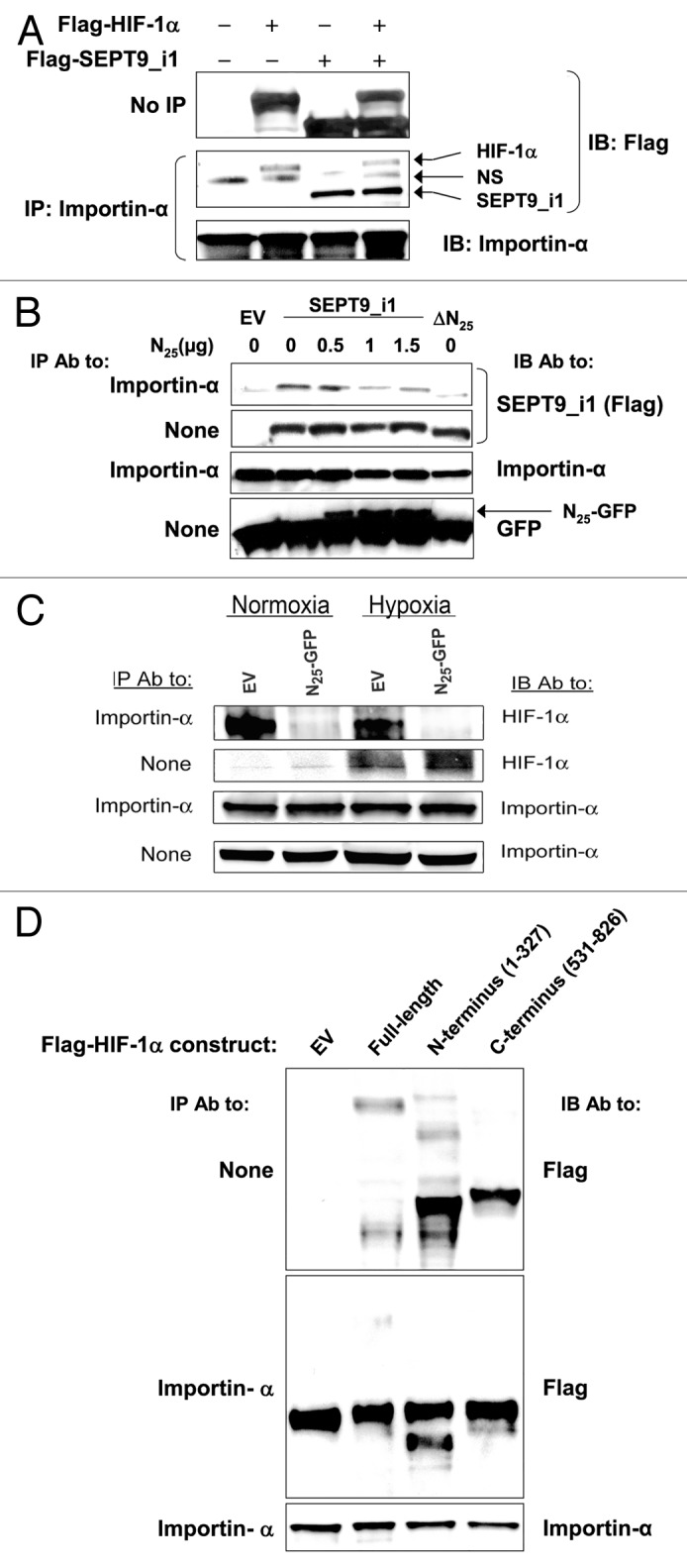

HIF-1α contains a C-terminal bipartite basic NLS that interacts with various members of the importin-α family.18 Since the N25 fragment also contains a bipartite NLS, we hypothesized that N25 reduces HIF-1α nuclear transport through competition with HIF-1α interaction to importin-α. To examine this hypothesis, we first tested whether HIF-1α and SEPT9_i1 interacts with importin-α simultaneously (Fig. 6A). Flag-HIF-1α and Flag-SEPT9_i1 were cotransfected into HEK 293T cells and subjected to immunoprecipitation with importin-α antibody. Both HIF-1α and SEPT9_i1 were immunoprecipitated by importin-α (Fig. 6A). Since both proteins are tagged with Flag, it seemed that there were more SEPT9_i1 molecules (3–4-fold) bound to importin-α than to HIF-1α molecules. Next, we tested the effect of N25 expression on the interaction between SEPT9_i1 and importin-α (Fig. 6B). Full-length SEPT9_i1 was expressed in HEK 293T cells for co-immunoprecipitation with antibodies to importin-α. As shown in Figure 6B, SEPT9_i1 interacted with endogenous importin-α, and this interaction was disrupted in the presence of N25-GFP. Furthermore, the interaction of importin-α with a truncated form of SEPT9_i1 that lacks N25 (ΔN25) was much more reduced compared with its interaction with the full-length SEPT9_i1 (Fig. 6B). We then tested whether N25-GFP affects the interaction between endogenous HIF-1α and importin-α (Fig. 6C). Expression of N25-GFP decreased the interaction between HIF-1α to importin-α (Fig. 6C). It is important to emphasize that N25 neither interacts with HIF-1α nor affects the interaction between HIF-1α with SEPT9_i1 (Fig. S5). HIF-1α contains 2 bipartite NLS sequences, one within the N terminus (amino acids 17–33) and another within the C terminus (amino acids 718–756). Therefore, we used N- and C-terminal HIF-1α constructs to map the interactive regions of HIF-1α with importin-α. As shown in Figure 6D, HIF-1α’s N-terminal part bound importin-α much more strongly than its C-terminal part.

Figure 6. N25 manipulated HIF-1 α and SEPT9_i1 interactions with importin-α. (A) HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-HIF-1α and Flag-SEPT9_i1 or empty vector (EV). Whole cellular extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-importin-α and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies to Flag and importin-α. NS, nonspecific. (B) HEK 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with expression vectors encoding Flag-tagged full-length SEPT9_i1 and increasing amounts of N25-GFP complemented with pGFP-N1 EV to total 1.5 μg DNA/sample, or with Flag-SEPT9_i1-∆N25 (∆N25; lacking N25). After 48 h, whole cellular extracts were prepared and subjected to IP using anti-importin-α antibody (Ab) and then IB with Ab to Flag, importin-α and GFP. None, no immunoprecipitation, whole cellular extract only (input). (C) PC-3 cells stably expressing N25-GFP or EV, were grown under normoxia or hypoxia for 6 h, and then whole cellular extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-importin-α antibody and then IB with Ab to HIF-1α and importin-α. (D) Flag-HIF-1α constructs, full-length (FL), amino acids 1–327, amino acids 531–826 or EV were expressed in HEK 293T cells and subjected to IP with Ab to importin-α and IB with Ab to Flag and importin-α.

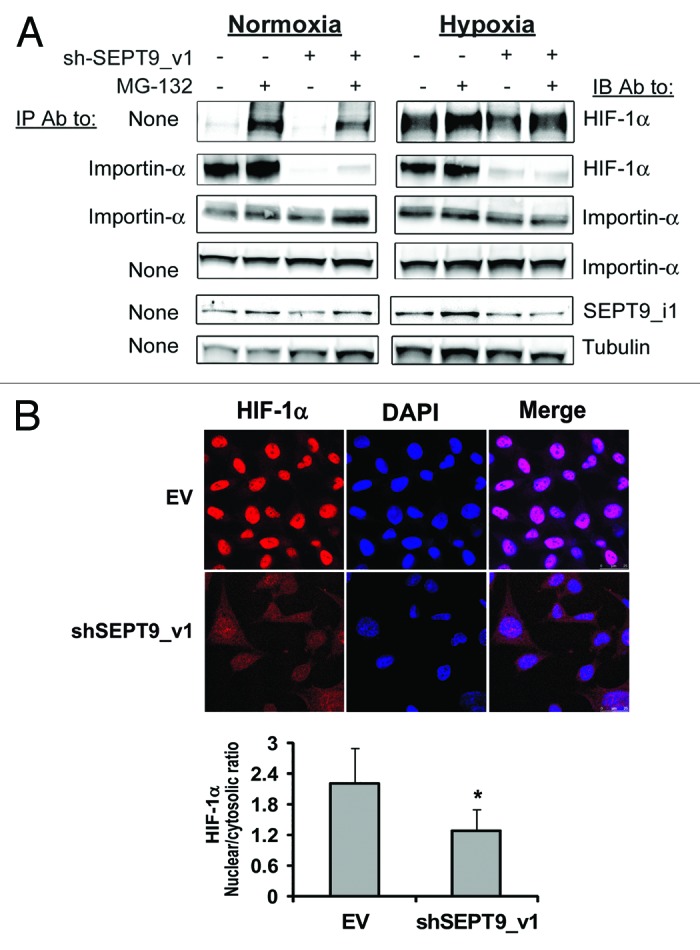

To further confirm the involvement of SEPT9_i1 in importin-α-mediated nuclear translocation of HIF-1α, we used PC-3 cells stably expressing shRNA that specifically knocks down SEPT9_i1. In agreement with previous data,19 silencing SEPT9_i1 (shSEPT9_v1) inhibited total HIF-1α protein expression, and more strikingly interfered with HIF-1α’s association with importin-α, under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 7A). To confirm that the interference of HIF-1α and importin-α was not because of decreased HIF-1α protein levels by silencing SEPT9_i1, the cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Fig. 7A). The results showed that the interaction between HIF-1α and importin-α was not completely restored even in the presence of MG-132 (Fig. 7A). Thus, we conclude that SEPT9_i1 is important for HIF-1α interaction with importin-α. Analysis by confocal fluorescence microscopy clearly showed less nuclear localization of HIF-1α and more cytoplasmic distribution of HIF-1α when SEPT9_i1 was silenced (Fig. 7B). Densitometric quantification of HIF-1α fluorescent levels showed a significant decrease (40%) in HIF-1α nuclear/cytosolic ratio by SEPT9_i1 silencing (Fig. 7B, lower panel). Altogether, these results indicated that SEPT9_i1 interacted with importin-α, and that this interaction was important to enhance the interaction between HIF-1α and importin-α that is required for optimal HIF-1α nuclear translocation (see model in Fig. 8).

Figure 7. SEPT9_i1 knockdown decreased HIF-1α interaction with importin-α and its nuclear translocation. (A) PC-3 cells stably expressing shSEPT9_v1 or control EV were treated or untreated with 10 μM MG-132 and exposed to hypoxia or normoxia for 6 h. Whole cellular extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using antibody (Ab) to importin-α and immunoblotted (IB) with Ab to HIF-1α, importin-α, SEPT9_i1 and tubulin. None, no immunoprecipitation, whole cellular extract only (input). (B) PC-3 cells stably expressing shSEPT9_v1 or EV were seeded on cover glasses, exposed to 6 h hypoxia in the presence of 20 nM of LMB. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence labeling with HIF-1α Ab (red staining) and DAPI. Staining was analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (magnification ×40). Lower panel, densitometric quantification of HIF-1α fluorescent signal of each cell from 4 different fields. The mean of nuclear/cytosolic ratio was plotted against the different conditions. *P = 0.001 shSEPT9_v1 compared with EV.

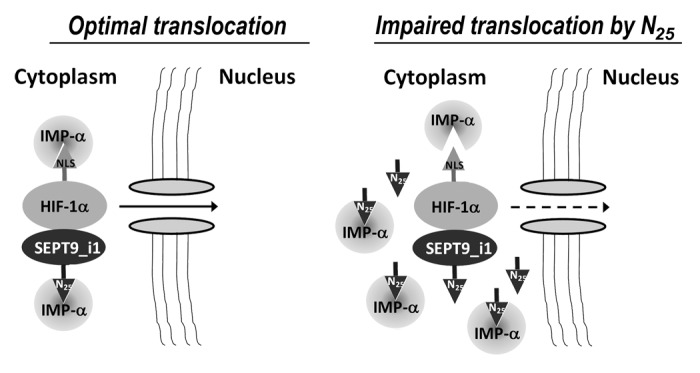

Figure 8. A proposed model for SEPT9_i1-importin-α in HIF-1α nuclear translocation. SEPT9_i1 interacts with both HIF-1α and importin-α to drive HIF-1α nuclear translocation. The interaction between SEPT9_i1 and importin-α is mediated by SEPT9_i1 N25 depending on its NLS sequence. When N25 is overexpressed it competes with the full-length SEPT9_i1 for binding importin-α. As a consequence HIF-1α translocation to the nucleus is impaired. IMP-α, importin-α; NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Discussion

In the present study, we describe a novel mechanism by which SEPT9_i1 promoted HIF-1 transcriptional activation. SEPT9_i1 binds to both importin-α and HIF-1α to facilitate HIF-1α translocation into the nucleus. The interaction between SEPT9_i1 and importin-α occurred through a bipartite NLS located in the unique N terminus of SEPT9_i1, the N25 termed domain. Moreover, expression of N25 competed with the endogenous SEPT9_i1 on its interaction with importin-α (Fig. 6B) and, as a consequence, decreased HIF-1α nuclear translocation (Fig. 5) and HIF-1 transcriptional activation (Figs. 1 and 2C). Most importantly, mutation of the NLS domain abolished this effect (Fig. 3C). The observation that SEPT9_i1 associated with HIF-1α through the GTPase domain20 and with importin-α through N25 supported the hypothesis that SEPT9_i1 acts to facilitate the assembly of importin-α/HIF-1α complex to enable efficient nuclear translocation of HIF-1α.

Interestingly, the position of N25 in the chimera with GFP was critical for the inhibitory effects on HIF-1. We showed that overexpression of the N25-GFP chimera decreased HIF-1 activation (Fig. 2C), whereas GFP-N25 chimera did not inhibit HIF-1 transcriptional activation (Fig. 2D). Since Flag-N25 was active (Fig. 1), and since only the unstable chimera N25-GFP was active (Figs. 2C and 3C), we propose that there could be steric disturbance effects of the relatively long GFP when it is positioned on the N terminus of N25. Moreover, GFP-N25 chimera not only did not have inhibitory effects but even slightly enhanced HIF-1 transcriptional activity (Fig. 2D) and HIF-1α nuclear transport (Fig. 5A). Since most of the N25-GFP chimera is cleaved, it is plausible to presume that only the free N25 is active. In comparison with N25-GFP, the mutated N25*-GFP chimera is still cleaved and is not active at all (Fig. 3), which further strengthens the hypothesis that N25-GFP is the only active form although, or because, it is cleaved. Of note, we observed that the mutated N25*-GFP increased HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Meanwhile, the exact mechanism of this phenomenon is unclear. A possible explanation is that N25*-GFP affects septin hetero-octamer structures as recently described by Sellin et al.21 They showed that the variable N terminus of SEPT9 affects assembly into higher-order structures that could be important for the interactions with importin-α.

Overexpression of N25-GFP inhibited tumor growth and angiogenesis concomitant with decreased HIF-1 transcriptional activity in vivo (Fig. 4). A curious and still not understood feature of the different mammalian septins groups is that a single member of each group has a particularly long N-terminal extension (SEPT4, SEPT8, and SEPT9).22 In SEPT9, the only difference between the SEPT9_v1, SEPT9_v2, and SEPT9_v3 variants is basically the N25 domain. Furthermore, SEPT9_v1 was shown to be the most frequently overexpressed variant in breast cancer cells3 and ovarian carcinoma.6 Our results may explain these structural-functional relationships, since we show that the N terminus in this case is critical to the importins-α-dependent nuclear transport process.

Nuclear entry of HIF-1α subunits is a necessary step for the formation of DNA-binding complex with HIF-1β subunit and for the transcriptional activation of HIF-1 target genes. The HIF-1α nuclear accumulation induced by hypoxia is mediated through a well-conserved bipartite-type NLS in the C terminus of the protein.23 The C-terminal bipartite basic NLS was shown to directly interact with importins-α1, α3, α5, and α7 in vitro.18 HIF-1α also contains a putative N-terminal bipartite NLS, but it was reportedly not effective in interactions with importins-α in vitro.18 In the current work, however, we showed by in vivo co-immunoprecipitation assays that the HIF-1α N-terminal binds importin-α even more efficiently than its C-terminal (the antibody that recognizes importin-α1, α3, α5, and α7) (Fig. 6D). This discrepancy in HIF-1α N-terminal NLS interaction with importin-α may result from the involvement of co-factors and other importins that were not present in the in vitro binding tests described by Depping et al.18 Chachami et al. showed that HIF-1α also contains an atypical hydrophobic CRM1- and phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export signal (NES) and can therefore shuttle in and out of the nucleus.24 Furthermore, those authors showed that importins α4 and α7 accomplish nuclear import of HIF-1α more efficiently than the classical importin α/β NLS receptor. Moreover, the interaction of importin α7 with HIF-1α was mapped at its N-terminal part, encompassing the HLH-PAS domains.24 Here, we showed that SEPT9_i1 directly interacts with importin-α, and since it also interacts with HIF-1α, it mediates and facilitates HIF-1α nuclear transport. Altogether, it appears that HIF-1α nuclear transport can follow more than one pathway into the nucleus, and that it involves a multifaceted fine-tuned regulated process that is dependent on the protein expression pattern in the cell at a given time.

Previous reports from our lab have shown that targeted knockdown of SEPT9_v1 had dramatic effects on tumor growth and angiogenesis in cancer cells.19 Herein, we showed that knockdown of SEPT9_v1 dramatically decreased HIF-1α interaction with importin-α (Fig. 7A), reduced its nuclear accumulation and increased its cytosolic localization under hypoxia (Fig. 7B). These results further support the importance of the role of SEPT9_i1 in HIF-1α nuclear transport and on HIF-1 transcriptional activation.

The findings described in this study support the hypothesis that a significant portion of HIF-1α nuclear translocation is mediated by SEPT9_i1 in cooperation with importin-α as schematically summarized in Figure 8. We suggest that SEPT9_i1 serves as a scaffold protein for enhancing HIF-1α interaction with importin-α to facilitate efficient HIF-1α translocation to the nucleus. We showed that interference of HIF-1α translocation process was feasible by either expression of N25 or by silencing SEPT9_i1, which disrupted the interaction between importin-α and SEPT9_i1/HIF-1α .

In conclusion, the results of the current study provide a novel mechanism that regulates intracellular HIF-1α trafficking, which consequently affects tumor growth and angiogenesis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of the involvement of a septin protein in the importin-α-dependent cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation process. As such, disruption of HIF-1α−SEPT9_i1−importins-α interactions may serve as a target for cancer therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and hypoxia treatment

Human prostate cancer PC-3 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640; human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cells and breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells were maintained in DMEM. All media were supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2 in air. For hypoxic exposure, cells were placed in a sealed modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) flushed with 1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2 and then cultured at 37 °C.

Antibodies and reagents

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal antibody to SEPT9_i1 previously produced and characterized,9 mouse monoclonal anti-HIF-1α (BD Biosciences), mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag and mouse monoclonal anti-importin-α (Sigma-Aldrich), goat polyclonal anti-TOPO-I, and anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), mouse monoclonal anti-CD34 and anti-Ki67 (DakoCytomation), and mouse monoclonal anti-HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals) for immunofluorescence. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch) used for western blotting, MACH 3 Rabbit HRP Polymer (Biocare Medical) for immunohistochemistry and Alexa Flour 594 donkey anti-mouse (Invitrogene) for immunofluorescence. Leptomycin B (LMB) and MG-132 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmids and retroviral vector constructions

Human Flag-tagged HIF-1α (GenBank accession number NM_001530), SEPT9_v1 cDNA sequence (GenBank accession number AF189713) and the NH2-terminal truncated form of SEPT9_v1 (ΔN25; deletion of the first 25 amino acids) were previously constructed into p3XFLAG-myc-CMV-25 (Sigma-Aldrich) to provide the Flag tag at the NH2 terminus.9 Flag-tagged HIF-1α constructs consisting of amino acids 1–327 and 531–826 were designed previously.20 N25 was constructed by RT-PCR using the appropriate primers and subcloned either into the p3XFLAG-myc-CMV-25 at XbaI/HindIII sites, or into the pEGFP-N1 (Clonthech Laboratories) at HindIII/BamHI sites, to provide the GFP tag at the C terminus of N25. To construct N25 into viral vectors, its sequence was amplified by PCR using Flag-N25 vector as template with the following set of primers: forward, 5′- CCGGCGCCTCGAGCTATGAAGAAGTCTTACTCAGGAGGCAC -3′ and

reverse, 5′- CGCGCCCGGATCCTGGGCCACTGGAGTCACC -3′, which contains the XhoI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites (underlined), respectively. The PCR product was subcloned into the pRetroQ-AcGFP1-N1 and pRetroQ-AcGFP1-C1 (Clontech) vectors using the respective cloning sites. The SEPT9_i1-N25 putative bipartite NLS was mutated by 2 sequential site-directed mutagenesis using the Stratagene QuickChange kit, following the manufacturer's protocol. The original sequence of N25 bipartite NLS was mutated from KKSYSG and RLRRLG to naaSYSG and RLairs, respectively, using the pRetroQ-AcGFP1-N1-N25 (N25-GFP) plasmid as a template. The residues were mutated in a manner that will keep flexibility and minimize generalized conformational disruption as a result of the substitutions, using the flexible NAARIS residue.17 The point mutations were introduced with the following oligos: for RLRRLG -

sense, 5′-CTCGAGCTCAAGCTTATGAACGCGGCTTACTCAGGAGGCACGCGG-3′ and antisense, 5′-CCGCGTGCCTCCTGAGTAAGCCGCGTTCATAAGCTTGAGCTCGAG-3 and for NAASYSG -

sense, 5′- CCTCCAGTGGCCGGCTCGCGATCCGTAGTGACTCCAGTGGCCCA-3′ and antisense 5′- TGGGCCACTGGAGTCACTACGGATCGCGAGCCGGCCACTGGAGG-3′. The mutated bases are marked in bold. All mutations were verified by sequencing (Hylabs Ltd).

Retroviral infection

GP2–293 packaging cells (Clontech) grown in 6-well plates were cotransfected with 1 µg of empty pRetroQ-AcGFP1-N1 and pRetroQ-AcGFP1-C1 vectors or the related vectors carrying N25 together with 1 µg of pAmpho vector (Clontech), using 7 µl of GenePORTER transfection reagent (Gene Therapy Systems, Inc) per well. After 48 h of transfection, the supernatants containing the retroviral particles were collected, filtered through a 0.45 µm filter and used to infect PC-3 cells in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene. The cells were reinfected 24 h later. After 3 d of infection, the cells were treated with 1 µg/ml or 0.3 µg/ml puromycin for the selection of stable infected PC-3 cells. Stable infection was verified by GFP fluorescence.

Transient transfection and reporter gene assays

Cells were transfected using GenePORTER transfection reagent (Gene Therapy Systems, Inc), as described.25 Luciferase enzymatic activity was measured using TROPIX commercial kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was measured by BMG Labtechnologies LUMIstar Galaxy luminometer. Arbitrary luciferase activity units were normalized to the amount of protein in each assay point.

HIF-1 DNA binding

HIF-1α transcriptional was also measured using the TransFactor ELISA-based kit (BD Mercury™, Clontech) for HIF-1, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein extraction and western blotting

Whole cellular extracts and nuclear extracts were prepared and analyzed as previously described.26 Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce). For immunoprecipitation, cells grown in 6 or 10 cm plates were washed with ice-cold PBS and processed as described elsewhere.26,27 Protein extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the antibodies as displayed in the Figures. Between 50–70 μg of protein were loaded in each lane.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer's instructions. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Verso cDNA kit (Abgene, Epsom) using anchored oligo(dT) as first-strand primer. qRT-PCRs were done with primers specific to HIF-1α, VEGF, endothelin-1 (ET-1), glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1), and β-actin genes in duplicates using LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Applied Science) as described elsewhere.28 PCR reactions were measured at a total volume of 10 μL using 3 mmol/L MgCl2 and 0.5 μmol/L of each primer. The expression of the each gene was normalized using β-actin expression levels.

2,3-Bis[2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt (XTT) proliferation assay

Cells (1500–2000 per well) were seeded in 96-well plates in a volume of 200 μL for cell proliferation assay using the XTT kit (Biological Industries Ltd). XTT reagent was added in at least triplicates for each time point and processed as previously described.9

Tumor model

PC-3 cells (2 × 106) stably expressing N25 or empty vector were injected subcutaneously into the back of athymic nude mice. All procedures were done in compliance with the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee and NIH guidelines. The animals were monitored for tumor development twice weekly. Tumor dimensions were measured with calipers, and tumor volume was calculated according to the following formula: tumor volume = width2 × length/2. The animals were sacrificed before the tumors reached 1000 mm3 or when the mice started to lose weight. The tumors were excised and cut into 2 pieces. One piece of tumor was fixed with 4% buffered formalin for immunohistochemical staining, and the rest of the tumor was immediately frozen in liquid N2 and kept at −80 °C for protein and RNA extraction.

Protein and total RNA extraction from xenograft tumors

Tumor tissue (20 mg) was manually homogenized in 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 4 mmol/L EDTA, and 2% SDS supplemented with protease inhibitors, incubated on ice for 30 min, and then cleared by centrifugations. Protein extracts were analyzed as described above. Total RNA was extracted from the tumors using manual homogenization and the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunohistochemical staining

For immunohistochemical staining, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned into 3 μm thickness and mounted on Superfrost/plus slides (Menzel-Gläser). The sections were processed for immunostaining with anti-CD34 (1:50 dilution) or anti-Ki67 (1: 25 dilution) for 30 min at room temperature as previously described.9 For negative controls, the exact procedure was done with the omission of either the primary or the secondary antibody. Positive staining cells and microvessels were counted for quantitative analysis of Ki67 (magnification ×40) and CD34 (magnification ×20) staining, and their density was expressed as the number of positive cells per total number of cells or capillaries per total section area excluding necrotic areas, respectively, and compared between control EV and N25 tumors.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal analysis

Cells (105) were plated into 24-well plates with 13-mm diameter cover glasses. After incubation overnight at 37 °C, cells were untreated or treated with 20 nM LMB and grown under normoxia or hypoxia at 37 °C. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and then fixed with cold methanol for 10 min, washed with PBS and permeabilized by cold acetone for 3 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS. Blocking was done in 1% BSA/10% normal donkey serum/PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were subsequently incubated with primary HIF-1α antibody diluted 1:50 in primary antibody dilution buffer (Biomeda) for 2 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed 3 times in PBS and incubated for 1 h in the dark with the secondary antibody (Alexa Flour 594 donkey anti-mouse diluted 1:300 in PBS), after which the slides were washed in PBS, and DAPI was added for 3 min at room temperature. Samples were washed 3 times with PBS, cover glasses were removed, and samples were mounted onto slides using Fluorescent Mounting Medium (Golden Bridge International [GBI] Life Science Inc). Samples were examined under an Olympus microscope or a Leica SP5 confocal microscope using a ×63 NA1.4 lens. Laser and microscope settings were according to the manufacturer's instructions. Identical parameters (e.g., scanning line, laser light, contrast, and brightness) were used for comparing fluorescence intensities. Four microscopic fields were taken from each sample. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). DAPI staining was used to define the nuclear Region of Interest (ROI). Cytosolic ROI was calculated by subtracting the nuclear ROI from whole cell HIF-1α staining ROI for each cell individually as described (http://sciencetechblog.com/2011/05/24/measuring-cell-fluorescence-using-imagej/). Quantitative fluorescence data were exported from ImageJ generated histograms into Microsoft Excel software for further analysis and presentation. Mean nuclear/cytosolic ratio of all cells quantified from 4 different fields was calculated and compared between the different conditions.

Statistical analysis

The experiments presented in the figures are representative of 3 or more independent repetitions. The data are expressed as means ± SD or ± SE. Student t test was used to compare differences between particular conditions. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ms Esther Eshkol is thanked for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Israeli Ministry of Industry and Trade (Nofar program) and the Dr Miriam and Sheldon G Adelson Medical Research Foundation (AMRF).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- SEPT9_i1

septin 9 isoform 1

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- N25

the first 25 amino acids of SEPT9_i1

- HRE

hypoxia-response element

- LMB

leptomycin B

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25379

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25379

References

- 1.Spiliotis ET, Gladfelter AS. Spatial guidance of cell asymmetry: septin GTPases show the way. Traffic. 2012;13:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connolly D, Yang Z, Castaldi M, Simmons N, Oktay MH, Coniglio S, et al. Septin 9 isoform expression, localization and epigenetic changes during human and mouse breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R76. doi: 10.1186/bcr2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez ME, Peterson EA, Privette LM, Loffreda-Wren JL, Kalikin LM, Petty EM. High SEPT9_v1 expression in human breast cancer cells is associated with oncogenic phenotypes. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8554–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montagna C, Lyu MS, Hunter K, Lukes L, Lowther W, Reppert T, et al. The Septin 9 (MSF) gene is amplified and overexpressed in mouse mammary gland adenocarcinomas and human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows JF, Chanduloy S, McIlhatton MA, Nagar H, Yeates K, Donaghy P, et al. Altered expression of the septin gene, SEPT9, in ovarian neoplasia. J Pathol. 2003;201:581–8. doi: 10.1002/path.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott M, McCluggage WG, Hillan KJ, Hall PA, Russell SE. Altered patterns of transcription of the septin gene, SEPT9, in ovarian tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1325–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett KL, Karpenko M, Lin MT, Claus R, Arab K, Dyckhoff G, et al. Frequently methylated tumor suppressor genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4494–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanbery L, D’Silva NJ, Lee JS, Bradford CR, Carey TE, Prince ME, et al. High SEPT9_v1 Expression Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2010;3:239–45. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amir S, Wang R, Matzkin H, Simons JW, Mabjeesh NJ. MSF-A interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and augments hypoxia-inducible factor transcriptional activation to affect tumorigenicity and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:856–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podar K, Anderson KC. A therapeutic role for targeting c-Myc/Hif-1-dependent signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1722–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosse JP, Michiels C. Tumor hypoxia affects the responsiveness of cancer cells to chemotherapy and promotes cancer progression. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:790–7. doi: 10.2174/187152008785914798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semenza GL. Hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:223–4. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9058-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semenza GL. Hypoxia and human disease-and the Journal of Molecular Medicine. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:1293–4. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park EJ, Kong D, Fisher R, Cardellina J, Shoemaker RH, Melillo G. Targeting the PAS-A domain of HIF-1alpha for development of small molecule inhibitors of HIF-1. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1847–53. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner LB, Corn PG. Hypoxic regulation of mRNA expression. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1916–24. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.13.6203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson IA, Haft DH, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA, Lerner RA, Brenner S. Identical short peptide sequences in unrelated proteins can have different conformations: a testing ground for theories of immune recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:5255–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Depping R, Steinhoff A, Schindler SG, Friedrich B, Fagerlund R, Metzen E, et al. Nuclear translocation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs): involvement of the classical importin alpha/beta pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amir S, Golan M, Mabjeesh NJ. Targeted knockdown of SEPT9_v1 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis of human prostate cancer cells concomitant with disruption of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:643–52. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amir S, Wang R, Simons JW, Mabjeesh NJ. SEPT9_v1 up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 by preventing its RACK1-mediated degradation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11142–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808348200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellin ME, Stenmark S, Gullberg M. Mammalian SEPT9 isoforms direct microtubule-dependent arrangements of septin core heteromers. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:4242–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-06-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinoshita M. Assembly of mammalian septins. J Biochem. 2003;134:491–6. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo JC, Shibuya M. A variant of nuclear localization signal of bipartite-type is required for the nuclear translocation of hypoxia inducible factors (1alpha, 2alpha and 3alpha) Oncogene. 2001;20:1435–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chachami G, Paraskeva E, Mingot JM, Braliou GG, Görlich D, Simos G. Transport of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1alpha into the nucleus involves importins 4 and 7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manisterski M, Golan M, Amir S, Weisman Y, Mabjeesh NJ. Hypoxia induces PTHrP gene transcription in human cancer cells through the HIF-2α. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3723–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.12931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, LaVallee TM, Pribluda VS, Swartz GM, Johnson MS, et al. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:363–75. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mabjeesh NJ, Post DE, Willard MT, Kaur B, Van Meir EG, Simons JW, et al. Geldanamycin induces degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha protein via the proteosome pathway in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ben-Shoshan M, Amir S, Dang DT, Dang LH, Weisman Y, Mabjeesh NJ. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Calcitriol) inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1/vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1433–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.