Abstract

Background

Total-pancreatectomy (TP) with intraportal-islet-auto-transplantation (IAT) can relieve pain and preserve beta-cell-mass in patients with chronic-pancreatitis (CP) when other-therapies fail. Reported is a >30-year-single-center-series.

Study Design

409 patients (53 children, 5–18 yrs) with CP underwent TP-IAT from Feb/1977–Sept/2011; (etiology idiopathic-41%; SOD/biliary-9%; genetic-14%; divisum-17%; alcohol-7%; other-12%); mean age-35.3 yrs,); 74% female; prior-surgeries 21%--Puestow procedure 9%, Whipple 6%, distal pancreatectomy 7%; other 2%). Islet-function was classified as insulin-independent for those on no insulin; partial if known C-peptide positive or euglycemic on once-daily-insulin; and insulin-dependent if on standard basal–bolus diabetic regimen. An SF-36-survey for Quality-of-Life (QOL)) was completed before and in serial follow-up by patients done since 2007 with an integrated-survey that added in 2008.

Results

Actuarial-patient-survival post-TP-IAT was 96% in adults and 98% in children (1-year) and; 89% and 98% (5-years). Complications requiring relaparotomy occurred in 15.9%, bleeding (9.5%) being most common. IAT-function is achieved in 90% (C-peptide >0.6 ng/ml). At 3 years, 30% were insulin-independent (25% in adults, 55% in children) and 33% had partial-function. Mean HbA1C was <7.0% in 82%. Prior pancreas surgery lowered islet-yield (2712vs4077/kg, p=.003). Islet yield [<2500/kg (36%); 2501–5000/kg (39%); >5000/kg (24%)] correlated with degree of function with insulin-independent rates at 3 yrs of 12, 22 and 72%, partial function 33, 62 and 24%. All patients had pain before TP-IAT and nearly all were on daily-narcotics. After TP-IAT, 85% had pain-improvement. By two years 59% had ceased-narcotics. All children were on narcotics before, 39% at follow-up; pain improved in 94%; 67% became pain-free. In the SF-36 survey, there was significant improvement from baseline in all dimensions including the Physical and Mental Component Summaries (P<0.01), whether on narcotics or not.

Conclusions

TP can ameliorate pain and improve QOL in otherwise-refractory-CP-patients, even if narcotic-withdrawal is delayed or incomplete because of prior long-term use. IAT preserves meaningful islet function in most patients and substantial islet function in >2/3 of patients with insulin-independence occurring in one-quarter of adults and half the children.

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis is a disease of diverse etiologies in which the pain can be devastating, lead to narcotic dependence, severely impair quality of life and require surgery in an attempt to alleviate pain (1). Pain in chronic pancreatitis may be due to increased intra-ductal pressure secondary to partial or complete blockage of the pancreatic duct. It may also be intrinsic to the diseased gland itself that is riddled with inflammatory changes or the sequelae thereof (2). A principal in surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis is to relieve the pain while preserving as much pancreatic function as possible (3,4).

Procedures to treat chronic pancreatitis that embody this principal include minimally invasive endoscopic duct drainage via a sphincterotomy and/or stent placement (5); surgical drainage (Puestow procedure or modifications thereof, but only applicable to large duct disease, a minority of CP cases), partial resection (Whipple or distal pancreaetectomy) or, with the Beger or Frey procedures, a combination of head resection and distal duct drainage (4,6). All of the procedures preserve at least some of the function which was present at the time of surgery. However, pain is not relieved in all (thus pain was parencymal in those in whom drainage procedures fail and intrinsic to the residual pancreas following partial resection) or it returns over time (2). Thus the rationale for total pancreatectomy (TP) is to completely remove the root cause of the pain (7). TP by itself is an antithesis to the principal mentioned (in the absence of any beta cell function, diabetes is much more difficult to manage, analogous to type 1 diabetes but with exocrine deficiency added), unless combined with an intraportal islet autotransplant (IAT) to preserve as much beta cell mass and insulin-secretory capacity as possible. Although chronic pancreatitis can induce diabetes mellitus by progressive destruction of islets (8), most CP patients are not diabetic when they present for treatment and have beta cell mass worth preserving (7).

At the University of Minnesota, TP-IATs (intraportal) have been performed to treat painful chronic pancreatitis since 1977 (9). The first patient, with small duct disease, was pain-free and insulin-independent for the rest of her life (10). Since that time, more than 400 TP-IATs have been performed in adults and children, over half since 2007, and reports on early cases have been published (10–15).

Other centers adopted or independently applied IAT in a few cases in the 1980s (7,16–18). However, it was not until the mid-90s to early 2000s that relatively large series began at several centers (7,19–23).

Herein reported is the entire Minnesota series, with emphasis on the recent cases. The efficacy of the TP-IAT in terms of islet function, pain relief, narcotic use and quality of life were assessed.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Demographics

A total of 413 intraportal IATs were done in 409 patients (including 53 children) who underwent completion or one-stage TP between February 12, 1977 and September 1, 2011 (Figure 1). Five patients underwent two IATs, the first at the time of a partial pancreatectomy (Whipple in 3, distal in 2) and the second when pain relief did not occur at the time of a complete pancreatectomy. One had the first IAT elsewhere, while the other 4 patients had the first at Minnesota.

Figure 1.

Annual number of TP-IAT cases since the inception of the program in 1977. More than half the cases have been in era 3.

Baseline demographic characteristics at the time of TP-IAT and the eras selected for comparison of some parameters over time are given in Table 1. The oldest patient was 69 years, the youngest 5 years. Nearly three-quarters were female. By etiology of CP, the idiopathic group was the largest followed by pancreas divisum and familial/genetic; in very few was alcohol considered the cause. On average, pain was present for about 9 years before TP-IAT and for about 2 years before the diagnosis of CP was made. The mean interval from diagnosis to initiation of narcotics was about 3 ½ years and the mean duration of narcotic use prior to TP-IAT was also approximately 3 ½ years.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of TP-IAT Patients at the University of Minnesota July 1977–September 2011

| All TP-IAT (1977-Sept 2011) N=409 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Transplant Era | ||

| TP-IAT before 1996 | 49 | 12% |

| TP-IAT 1996 to 2005 | 110 | 27% |

| TP-IAT 2006 to Sept 1, 2011 | 250 | 61% |

| Adult | 356 | 87% |

| Pediatric* | 53 | 13% |

| Mean Age ± SEM | 35.3 ± 0.7 | |

| Adults | 38.3 ± 0.6 | |

| Pediatrics | 12.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 301 | 73% |

| Male | 108 | 27% |

| Mean BMI ± SEM | 24.5 ± 0.3 | |

| Etiology | ||

| Alcohol | 27 | 7% |

| Spincter of Odii Dysfunction/Biliary | 36 | 9% |

| Idiopathic | 169 | 41% |

| Pancreas Divisum | 71 | 17% |

| Familial | 58 | 14% |

| Other | 48 | 12% |

| Pre-transplant Diabetes | ||

| Yes** | 32 | 8% |

| No | 377 | 92% |

| Mean Years on Narcotics ± SEM (Minimum, Maximum) | 3.6 ± 0.3 (0.1, 23.8) | |

| Mean Years Chronic Pancreatitis ± SEM (Minimum, Maximum) | 7.1 ± 0.4 (0.3, 39.2) | |

| Mean Years Abdominal Pain ± SEM (Minimum, Maximum) | 9.2 ± 0.5 (0.2, 57.9) | |

Preteens: 22/Teenagers: 31

All had c-peptide positive diabetes and thus beta cell mass worth preserving

Interventions in attempt to relieve pain prior to TP-IAT

More than a fifth of the patients had direct surgery on the pancreas prior to the TP-IAT. The most common were Puestow procedures, Whipple operations and distal pancreatectomies (Table 2). The proportion undergoing prior direct surgery declined in each era. In contrast, endoscopic pancreatic duct drainage procedures (sphinctertomies or stent placements) prior to TP-IAT were documented in more than half of the patients and there was a progressive increase in application from era to era.; in Era 3 more than two-thirds had been so treated. Nearly a fifth of the patients were documented to have had celiac axis nerve blocks. The impact of previous surgery on pain relief and islet yield was addressed.

Table 2.

Previous Direct Pancreas Surgery at the Time of TP-IAT

| Era | 1. | 2. | 3. | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 to 1995 | 1996 to 2005 | 2006 to 2011 | 1977 to 2011 | |||||||

| % | (N) | 12% | (49) | 27% | (111) | 61% | (253) | (409) | ||

| Direct Pancreas Surgery | 39% | (19) | 28% | (31) | 15% | (38) | 21% | (88) | ||

| Puestow | 20% | (10) | 11% | (12) | 6% | (15) | 9% | (37) | ||

| Whipple | 4% | (2) | 8% | (9) | 6% | (15) | 6% | (26) | ||

| Beger/Frey | 0% | (0) | 1% | (1) | 2% | (4) | 1% | (5) | ||

| Duval | 10% | (5) | 1% | (1) | 0% | (0) | 1% | (6) | ||

| Distal Pancreatectomy | 18% | (9) | 11% | (12) | 3% | (8) | 7% | (29) | ||

| Operative Transduodenal Duct Drainage Procedure | 16% | (8) | 4% | (4) | 7% | (17) | 7% | (29) | ||

| Endoscopic Duct Drainage Procedure | 18% | (9) | 53% | 59 | 68% | (171) | 58% | (239) | ||

| Unspecified Duct Drainage Procedure | 24% | (12) | 17% | 19 | 2% | (4) | 8% | (35) | ||

Diagnosis of CP and Selection of patients or TPIAT

The criteria for selection of patients with CP for TP-IAT has evolved over the years (24). Currently, the patient must have had abdominal pain of > 6 months duration with impaired quality of life such as inability to work or attend school, inability to participate in ordinary activities, repeated hospitalizations, or constant need for narcotics, coupled with failure to respond to maximal medical treatment or endoscopic pancreatic duct drainage procedures.

To ensure that the patient does indeed have CP, the above must be coupled with at least one of the following: (1) Pancreas calcifications on CT scan, or abnormal ERCP, or > =6/9 criteria on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS); (2) Two of three of the following: ductal or parenchymal abnormalities on secretin stimulated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), EUS with 4/9 criteria positive, abnormal endoscopic pancreatic function tests with peak bicarbonate < 80 mmol/L).; (3) Histopathologic confirmed diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis from previous operations; (4) Hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 gene mutation) with a compatible clinical history; or (5) History of recurrent acute pancreatitis with > 3 episodes of pain associated with imaging diagnostic of acute pancreatitis and/or elevated serum amylase or lipase 3 times normal. Contraindications include active alcoholism, pancreatic cancer, illegal drug usage and poorly controlled psychiatric illness with predictable inability to comply with the postoperative regimen. Some of the patients were diabetic but had beta cell function (C-peptide positive) worth preserving with an IAT. All patients are reviewed by a workgroup consisting of surgeons, a gastroenterologist, endocrinologists, pain management physicians and nurse coordinators. A patient is accepted for TP-IAT after a consensus is reached.

Surgical Procedure

TP was done in such a way that the blood supply to the pancreas was preserved until just before removal; only after full mobilization of the entire pancreas was the origin of the splenic artery and termination of the splenic vein ligated. In this way warm ischemic time to the islets was minimized. In cases where head and duodenal mobilization was difficult, the body and tail were removed separately and sent to the islet processing lab before the proximal portion was removed. For those without a prior Whipple procedure, all or part of the duodenum was resected, pylorus sparing when ever possible, distal sparing as well in selected case, allowing reconstruction via a duodenoduodenostomy or end to side duodenojejunostomy with choledochoduodenostomy to the distal duodenum without a Roux-en-y (10). In the cases where the distal duodenum was removed, reconstruction was done via a classic Roux-en-Y choledocho-jejunostomy and gastro- or (if pylorus-spared) duodeno-jejunostomy. Gastrostomy and feeding tube placement at the time of surgery was at the discretion of the surgeon. A spleen sparing TP was done in 124 patients (30%) using techniques previously described (25), including one in which the TP was done laparoscopically with the assistance of the DaVinci robotic device (26). In all of the patients, a cholecystectomy and appendectomy were done if it had not been done previously. Of note, 53 patients had their TP staged, with a Whipple, or Beger/Frey procedure or distal pancreatectomy being done prior to completion pancreatectomy (Table 2).

The islet preparation was generally returned to the operating room 3 ½ to 6 ½ (mean 4 ½) hours after the pancreatectomy. After administration of heparin (70 mg/kg intravenously), the islets were infused over a 15–60 minute period. The larger the tissue volume, the slower the infusion is in order to minimize portal pressure elevation. Currently if the pressure reaches 25 cm water, the infusion is stopped and any remaining tissue is discarded or placed in the peritoneal cavity. The patients were placed on a heparin drip or Lovenox to prevent clotting in the liver or portal vein.

Complications of surgery were assessed by the need and cause for relaparotomy during the admission for TP-IAT.

Islet Isolation

Although modifications have been introduced over the years (27–29), the basic method of islet preparation has been the same over time: dispersion of the pancreas in a stepwise fashion, first by intra-ductal injection of collagenase solution under pressure to disrupt the exocrine pancreas (islets are spared) and then digestion at 37° C in (since 1991) a shaking (Ricordi) chamber to mechanically facilitate dispersion and free the islets as much as possible (30,31). At the University of Minnesota, several enzyme preparations have been used over the years. The current enzyme mixture consists of intact C1 collagenase (Vitacyte) and neutral protease (SERVA}.

After digestion, the islets can be purified or partially purified by a gradient separation method (29) or can be transplanted as an unpurified preparation. Islet purification is performed using density gradients in the COBE 2991 cell processor (29). The decision to purify depends mainly on the post-digest tissue volume and the desire to minimize the increase in portal pressure that occurs during islet embolization to the liver (32). Gradient purification is associated with at least a 30% loss of islets. Currently, a post-digest tissue volume of >0.25 cc/kg is an indication to at least partially purify (32). Gradient purification was performed in 35% of the cases. The islet preparation time ranged from 3.5 to 6.5 hours, median 4.5 hours.

The final islet tissue preparation is suspended in 500 ml of CMRI culture medium (Mediatech, Inc) with human albumin added to a concentration of 2.5%. Mean baseline portal pressure in the series was 2.5 cm. The mean volume of tissue infused was 8.8 cc and mean peak portal pressure was 14.5 cm. Post infusion pressures are clearly a function of tissue volume. The mean closing pressures according to tissue volumes infused of < 5, 5–15 and > 15 cc were 3, 12, and 22 cm of water (p < 0.001).

As far as islet yield, in Era 1 the median was 2640 IE//kg body weight vs. 3249 IE/kg and 3260 IE/kg in Eras 2 and 3 respectively (p<0.05). In the overall series, the yields (IE/kg) were <2500/kg in 36%, 2501–5000/kg in 39% and >5000/kg in 24%. By era, the proportions <2500, 2501–5000 and >5000 IE/kg were 48%, 30% and 23% in Era 1; 33%, 48% and 20% n Era 2; and 34%, 42% and 24% in Era 3. Thus low yields are currently less frequent than in Era 1 but high yields have remained constant, occurring in about a quarter of the cases in all eras. Only 9 pancreases (4%) have yielded > 10,000 IE/kg while <1000 IE/kg was all that was isolated in 62 cases (16%).

Many factors affect islet yield (27), including the histopathology (33,34), and direct surgery on the pancreas prior to TP-IAT. In patients who had had a Puestow operation, the mean yield was 1883 IE/kg and in those who had undergone a distal pancreatectomy the mean was 1973/kg, vs. 3795 IE/kg in those who had not had prior surgery on the pancreas (P<0.01). A prior Whipple did not carry a penalty with a mean yield of 3647 IE/kg.

Insulin Requirement Assessment and Islet function Classification after TP-IAT

Insulin requirements were determined from the medical records and self-reported survey data. During the first three months post TP-IAT nearly all patients were given exogenous insulin to relieve beta cell functional stress during the engraftment (neovascularization) stage. Thereafter, according to protocol (not always exactly followed), an attempt was made to wean the patient off insulin as long as blood glucose levels were in a near normal target range (fasting<125 mg/dl post prandial <180 mg/dl and glycosolated hemoglobin <= 6.5 %) If these parameters were not achieved, the patients were maintained on insulin.

In the overall analysis of all cases, patients were classified as: 1. Insulin-independent; 2. Partial graft function (C-peptide positive, >0.6 ng/dl; or if C-peptide unknown, the ability to maintain near normal glucose and glycohemoglobin levels on once daily long acting insulin only or with only occasional supplementation (less than daily) with short acting insulin ); or 3. Insulin-dependent (C-peptide <0.6 ng/ml; or if unknown on both long and short acting insulin [basal-bolus regimen] to maintain glycemic control. Individual patient classifications as to islet function could change over time. Patient’s insulin-independence could revert to partial graft function or insulin-dependence. Also, insulin-dependence could evolve to partial function or partial function could change to either insulin-independence or -dependence.

In a separate analysis of the Integrated HRQOL survey cohort, patients were classified as taking 0 insulin injections per day (insulin-independent), only 1 injection per day (usually long acting insulin), or more than 1 insulin injection a day. Classification did not depend on C-peptide values but was strictly clinical. However all those on no insulin had to be C-peptide positive.

The proportion of patients in each function category over time was calculated according to the number or IE/kg transplanted (>5000, 2500–5000 and <2500 IE/kg). The HRQOL ratings were compared between groups according to whether the patients were insulin-independent or not.

The mean glycohemoglobin (HbA1cC) levels were calculated for each patient according to islet yield and the proportions with mean glycohemoglobin levels < 7.0% for each yield category were reported. The proportion of patients who achieved C-peptide positivity (>0.06 ng/ml) in each yield category as well as the mean C-peptide level were calculated as well. There was variable compliance with periodic metabolic testing and thus the results are a sample of the patient population. However there is uncertainty when C-peptide determinations are done in the patients with partial function, it is ≥0.6 ng/ml in all (15).

Narcotic Use and Pain after TP-IAT

All patients had been on narcotics before the operation. Narcotic use was determined from the medical records and from self-reported survey data. Patients were classified as either being on narcotics (no matter the dose) or off narcotics, meaning they took no narcotics daily or intermittently. Patients were asked if they had any pain during follow-up and if any component of the pain was similar to what they had considered pancreatic pain before TP-IAT. They also rated the severity of the pain on a scale adjusted between 0 and 100.

Health Related Quality of Life Retrospective (HRQOL) Assessments

Prior to 2006, patients participated in retrospective surveys of outcomes following TPIAT (7). Since January, 2007 the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item Short Form (SF-36) has been used (35). The SF-36 survey gives a health status profile along eight dimensions corresponding to the following scale scores: physical functioning, role limitations attributed to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, vitality, role limitations attributed to emotional health problems, and mental health. The scales ranged from 0 to 100 with 100 signifying more positive health attributes. These scales are the basis of the physical component summary (PSC) and the mental component summary scale (MCS). These latter more global measurements are standard normalized (mean of 50, standard deviation of 10) to represent a sample of the United States (36).

Since October, 2008 an Integrated Survey that includes the SF-36 has been used. The Integrated Survey includes disease specific (CP) questions and outcome related questions specific for TPIAT, including on pain, narcotic use, insulin requirements and satisfaction with the operation. Of 219 patients eligible to participate in the SF-36/Integrated surveys, 193 have done so (88%), all answering the SF-36 questions and 125 the additional Integrated Survey (IS) questions. The baseline demographic characteristics in the SF-36 (n=193) and the IS cohorts (n=125) are similar to those of those in the entire series (Table 1), and thus they are thought to be a representative sample.

The means of the patient scores in the SF-36 post-TP-IAT were compared to baseline in each of the eight categories as well as the PCS and MCS. In addition, the scores were compared in those who did vs. those who did not become insulin-independent as well as in those who were vs. were not on narcotics at the time of follow-up.

In regard to pain assessment in the Integrated Survey, two approaches were used. The first was a rating of pains severity on a 0–100 scale, and the second included questions regarding pain transitions. The pain transition measures are different from the average pain measures, which are captured serially (over time). They are measuring two slightly different facets of pain, both being of importance. The transition measure asks whether the patient has improved looking back on how they remember their pain before TP-IAT (this approach is used frequently when evaluating orthopedic surgery outcomes). The average pain uses a common metric pre-transplant and post-transplant.

Statistical Methods

The complexity of the data and the types of health outcomes were dictated using parametric and non-parametric statistical techniques. Patient survival rates were calculated using Kaplan-Meier actuarial methods. Mixed model methods were used to test for variations in outcomes with time. For the results, continuous variables were summarized as means, whereas categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages. When values were compared across small samples, the Wilcoxon statistic was used.

For analysis of SF-36 Health Survey, mixed model methods were used. This method was chosen because there was missing data frequently encountered in the panel and longitudinal studies. The second mixed method takes into account the dependence of replicate measures. With this approach, follow-up measures were more strongly associated with earlier scores for the subject, within subject variability, that is ignored in least squares regression more fully accounted for. This method takes into account change within subject in testing statistical differences across the scale scores. In addition, a mixed approach allowed us to quantify the effects of IAT in terms of standard metric. Finally, the mixed model methods can be used to specify either a normally distributed outcomes variable, such as an SF-36 scale score, or categorical end-point, such as an improvement in health status. Compound symmetry or unstructured covariance matrices were used in fitting the mixed model; time was treated as a continuous effect. All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT™ Version 9.2.

Other analyses, such as islet graft function rates were cross sectional with significance of differences at various time points or differences between groups at fixed time points determined by non-parametric methods. In analyses that did not include the entire series of TP-IAT, such as HRQOL, cohorts were compared for their pre-transplant characteristics and found nearly identical with the entire series of TP-IAT patients.

Results

Patient Survival

Of the 409 patients, there were 5 in-hospital deaths (1.2%): one from peritonitis due to a perforated colon, one from a pulmonary embolus, one (child) from peritonitis secondary to intestinal perforation from a feeding tube, one from sepsis, and one from multiple organ failure, cause uncertain. In addition to the in-hospital deaths, 53 patients died subsequent to initial discharge. The cause was unknown in 39. In the other 14, only 3 deaths were related to the CP disease process (continued alcohol abuse) or surgery (multiple enterocutaneous fistulae after reoperation for bowel obstruction) or possibly the islet transplant (hepatic steatosis). None of the other deaths (infection/respiratory in 5, vascular in 3, metabolic in 2, non-liver cancer in 1) appear related to the original disease or the subsequent surgery. Figure 2 shows the actuarial patient survival rate following TPIAT for the entire series of 409 patients. Two-thirds are alive at 15 years. There were no significant differences in patient survival according to era. At five years 86% of the patients in era 1, 88% in era 2, and 93% in era 3 were alive. There also were no significant differences in survival for pediatric vs. adult cases.

Figure 2.

Patient survival after TP-IAT. It is similar for adults and children.

Surgical Complications

Surgical complications requiring reoperation during the initial admission occurred in 15.9% of the patients. The most common reason for reoperation was bleeding, occurring in 9.5%. Reoperation for bleeding had a definite link to post infusion portal pressure. In a separate analysis of the last 230 cases, the overall incidence of reoperation for bleeding was 7.4%, but was 15% in those with a postinfusion portal pressure of >25 cm water, 2 ½ time higher than the 6% with a lower portal pressure. Anastamotic leaks occurred in 4.2 % of the patients, biliary in 1.4% and enteric in 2.8 %. Intra-abdominal infection requiring reoperation occurred in 1.9% of patients, wound infections requiring operative debridement in 2.2%. Gastrointestinal issues, such as bowel obstruction, omental infarction, bowel ischemia, delayed reconstruction because of bowel edema, tube perforation, required reoperation in 4.7% of patients. Two patients (<1%) required reoperation to remove an ischemic or bleeding spleen after a spleen sparing TP-IAT (done in 30% of patients).

Insulin Requirement and Islet function classification after TP-IAT

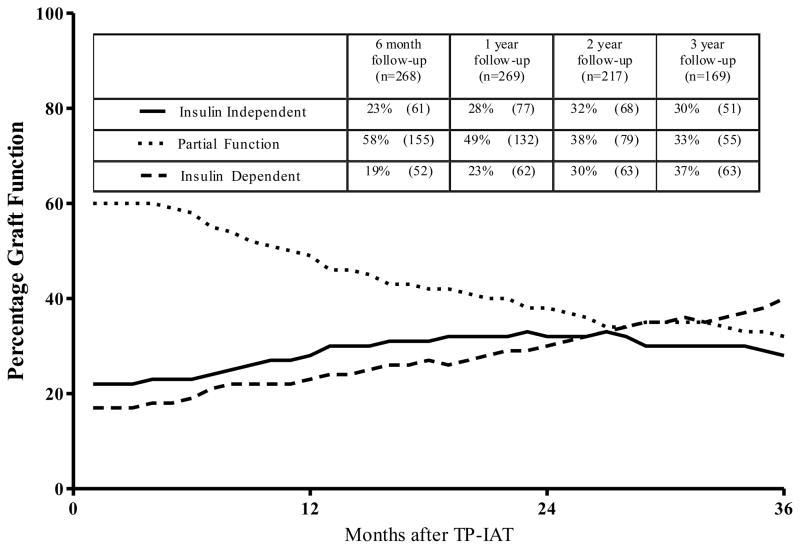

The proportion of patients in each islet function category (insulin-independent; partial function; fully insulin-dependent), regardless of islet yield, from 3 months to three years after TP-IAT, is shown in Figure 3. At 6 months nearly a quarter of the patients were insulin-independent, slightly less than a fifth were completely insulin-dependent, while over half had partial function (thus at this time point more than three quarters were on insulin). By three years, nearly a third were insulin-independent, another third had partial islet function and slightly more than a third were insulin-dependent. Overall, at least two-thirds had some islet function. The proportion of recipients becoming insulin-dependent slowly increases over time since the proportion of patients declining in function is greater than those whose function improves to the point of insulin–independence. Nevertheless at three years two-thirds of recipients have islet function to the degree that they can be insulin-independent or have easily managed diabetes.

Figure 3.

Classification of beta cell function over time in patients undergoing TP-IAT. The incidence of partial function is high at the beginning but then patients in this category evolve to insulin-independence or devolve to insulin-dependence and by three years each category includes about a third of the patients.

Table 3 shows the proportion of patients in the three islet function categories according to the number of IE/kg received. At 3 years, nearly three-quarters of patients receiving > 5,000 IE/kg were insulin-independent (about the same as at year) and nearly a quarter had partial function. Thus given this high yield, very few grafts completely failed. In contrast, of those receiving 2,500 to 5,000 IE/kg, only slightly more than a fifth were insulin-independent at three years. Nearly two-thirds had partial function. Even with a low yield, < 2,500 islet equivalents, more than an eighth achieved insulin-independence and one-third partial function. If >2500 IE/kg were transplanted, islet function was present in at least 90% at three years.

Table 3.

Islet Function Status According to Number of IE/Kg Transplanted

| 6 Month Follow-up | 12 Month Follow-up | 24 Month Follow-up | 36 Month Follow-up | C-Peptide Positive* (> 0.6 ng/ml) | % w/mean HbA1c < 7.0%** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| % | (N) | |||||||||

| < 2500 IE/Kg | (75) | (75) | (54) | (33) | 79% | 71% | ||||

| Insulin Independent | 13% | (10) | 13% | (8) | 15% | (8) | 12% | (4) | ||

| Partial Function | 56% | (42) | 53% | (40) | 48% | (26) | 33% | (11) | ||

| Insulin Dependent | 31% | (23) | 36% | (27) | 37% | (20) | 55% | (18) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2500–5000 IE/Kg | (82) | (83) | (62) | (37) | 97% | 86% | ||||

| Insulin Independent | 20% | (16) | 23% | (19) | 31% | (19) | 22% | (8) | ||

| Partial Function | 78% | (64) | 72% | (60) | 60% | (37) | 62% | (23) | ||

| Insulin Dependent | 2% | (2) | 5% | (4) | 10% | (6) | 16% | (6) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| >5000 IE/Kg | (49) | (49) | (31) | (25) | 100% | 94% | ||||

| Insulin Independent | 31% | (15) | 55% | (27) | 65% | (20) | 72% | (18) | ||

| Partial Function | 67% | (33) | 43% | (21) | 32% | (10) | 24% | (6) | ||

| Insulin Dependent | 2% | (1) | 2% | (1) | 3% | (1) | 4% | (1) | ||

Percent of patients in each islet yield category with C-Peptide Positive values greater than 0.6 ng/ml

Percent of patients in each islet yield category with mean Hb/A1c levels over time at less than 7.0%

The relation of IE/kg transplanted to glycemic control and C-peptide positivity is also shown in Table 3. Overall, 90% of the patients were C-peptide positive and 82% had a mean glycohemoglobin over time of <7.0%. In the three islet yield categories, the percent of patients achieving a mean glycohemoglobin of <7.0% correlated with islet yield, but even within the lowest yield category (<2500 IE/kg), nearly three quarters were achieved, consistent with the fact that more than three quarters were C-peptide positive. In the intermediate (2500–5000 IE/kg), nearly all and in the high (>5000 IE/kg) yield category all patients were C-peptide positive, consistent with the high proportion with mean glychohemoglobin levels <7.0%. If one combines the three yield categories (since this is unknown pre-surgery), 90% were C-peptide positive and 82% had a mean glycohemoglobin <7.0%.

Fasting and post-prandial C-peptide levels in patients tested were also compared across the three islet yield categories. In the <2500 IE/kg group, fasting and 1 and 2 hour pp C-peptide levels were 1.1 and 2.0 and 2.2 ng/ml respectively. In the 2500 IE/kg group the corresponding values were 1.2, 2.4 and 2.3 ng/ml and in the >5000 IE/kg category they were 1.3, 3.4 and 3.0 ng/ml. Thus, C-peptide levels at each time point were higher as the number of IE/kg transplanted increased and the post-prandial differences were significant (p<0.03).

Once insulin-independence was achieved, the attrition rate was also calculated. Five years after insulin independence was achieved, 54% of the patients were still insulin-independent, the rate correlating with IE/kg transplanted. 71% in those receiving > 5,000 IE/kg, 46% of those receiving 2,500 to 5,000 remain insulin-independent, and 30% of those received < 2,500 islet equivalents/kg were insulin-independent.

Long term durability of auto islets is possible and of patients with follow-up at 10 years, 36% were insulin-independent. The longest documented duration of insulin independence is 18 years. The longest documentation of partial function, after being insulin-independent for 16 years, is 22 years.

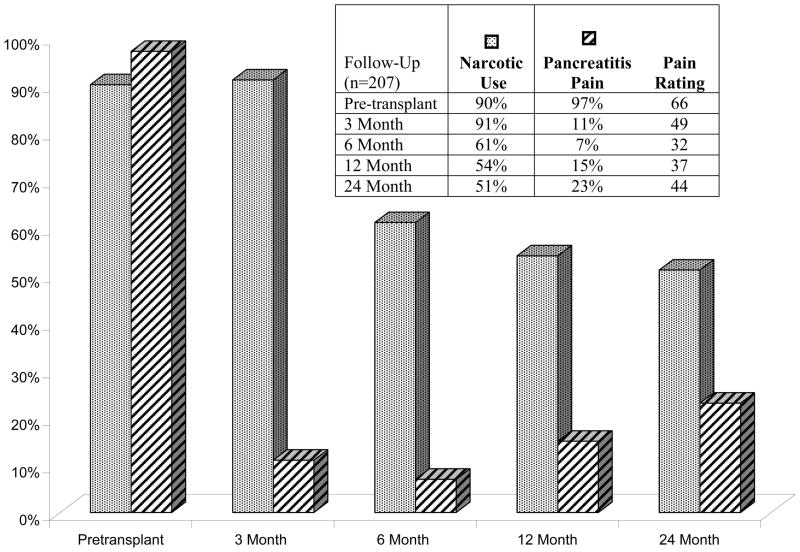

Pain and Narcotic Use after TP-IAT, Retrospective Review of Medical Records of Cases before 2007 (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Narcotic use and pain level before and serially after TP-IAT. The differences from baseline are significant (P<0.001).

In the Medical Record review, information on narcotic use and abdominal pain attributed to CP prior to TPIAT was available on 207 patients. The patients had been on narcotics for a mean duration of 3.6 years. Thus, slow weaning of narcotics was required following TPIAT. At 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after surgery, 91, 61, 54 and 51% of patients were on narcotics. At 1 year 94 % stated their pain had improved. Nevertheless, pain similar to the preoperative pancreatitis pain, though not necessarily of the same degree was stated to be present in 11%, 7%, 15% and 23% at the respective time points. However, the degree of pain, if present, was significantly lower than prior to the TPIAT. The mean pain rating score was 66 pre-transplant. In follow-up at the respective time points, mean pain rating scores were 49, 32, 37 and 44, significantly less than pre-surgery (p<0.001). Pain and narcotic use were also addressed in the patients participating in the survey, as detailed below.

Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes (HRQOL) and Pain and Narcotic Use in Cases Since 2006

Overall, prior to surgery, all patients had below-average HRQOL based on the SF-36 component of the Survey (Table 4). The Physical Component Scale (PCS) and Mental Component Scale (MCS) summary scores were 2 and 1.5 standard deviations lower than the standardized model for the US population respectively. The PCS and MCS both significantly improved over time (p <0.01), and the latter by more than 1 standard deviation. Scale scores for all 8 of SF-36 health dimensions also improved after surgery with the differences being significant for all (p < 0.05). The SF-36 also assessed for subjective impression of improved health since the previous year. At 6 months, 84% said they had improved compared to a year ago; at 1 year, 85% said so, reflecting the early improvement in health after the TPIAT. At 2 years 57% said they improved from their new baseline at 1 year. Thus, in at least half the patients, an improvement in health continues above that achieved by 1 year.

Table 4.

Health-Related Quality of Life Scores for SF-36 and Integrated Surveys

| Baseline (N) | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | Integrated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Insulin Independent | Insulin Dependent | ||||

| SF-36* | (160) | (114) | (70) | (66) | (26) | (37) |

| Physical Functioning | 53 ± 2 | 70 ± 2 | 73 ± 3 | 74 ± 3 | 83 | 68† |

| Role-Physical Limitations | 9 ± 3 | 32 ± 3 | 39 ± 4 | 42 ± 4 | 62 | 32† |

| Bodily Pain | 22 ± 2 | 48 ± 2 | 53 ± 3 | 49 ± 3 | 59 | 45 |

| Perceived Health | 36 ± 2 | 52 ± 2 | 50 ± 3 | 44 ± 3 | 53 | 40 |

| Social Functioning | 32 ± 2 | 55 ± 3 | 61 ± 3 | 60± 3 | 70 | 59 |

| Vitality | 26± 3 | 44 ± 2 | 50 ± 3 | 48 ± 3 | 59 | 43† |

| Role-Emotional Limitations | 37 ± 4 | 50 ± 4 | 61 ± 5 | 70 ± 5 | 77 | 72 |

| Mental Health | 60 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 74 ± 3 | 76 ± 3 | 83 | 76 |

| Physical Component Summary | 29 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 43 | 34 |

| Mental Component Summary | 38 ± 1 | 47 ± 1 | 47 ± 1 | 49± 2 | 51 | 49 |

| Improved Health Since Last Year | 7% | 86% | 86% | 57% | 58% | 57% |

| Integrated** | (102) | (95) | (57) | (51) | ||

| Narcotic Use | 100% (102) | 58% (55) | 56% (32) | 41% (21) | ||

| Pain Rating | 54 ± 2 | 32± 3 | 31± 3 | 30 ± 3 | ||

P<0.001 compared to baseline for all SF-36 scale scores

Integrated survey comparison on narcotic use and pain over time significant p-value <0.05 compared to baseline

Insulin independent vs. insulin dependent significant P-value <0.05 for physical functioning, role-physical limitations, and vitality compared to baseline

Islet function impact on HRQOL

In regard to the impact of islet function, there was a significant improvement in all health dimension scores and PCS and MCS, both in patients who required and did not require insulin. However, the improvement in each dimension was greater for the patients who became insulin-independent than those who did not and was statistically significant for physical functioning, role-physical limitations and vitality (Table 4).

Pain level and effect of narcotics on HRQO after TP-IAT

In the Integrated/SF-36 Survey, the patients were assessed for narcotic use after TP-IAT and if any pain was present, they were asked to rate the degree of pain (Table 4). Pain levels declined significantly (P<0.001), from a mean of 54 at baseline to 32 by 6 months and 24 by two years after TP-IAT. The number of patient’s on narcotics declined over time but slowly; at 2 years 41% were still on narcotics and either static or still weaning (Table 4).

The trajectory of improvement in each component of the SF-36 survey was independent of whether the patients were on or not on narcotics. The patients who were still on narcotics had a statistically significant (P<0.001) improvement in all ten SF-36 scores and the upward score trajectory was not statistically different for each item than those who had weaned off narcotics (examples in Fig. 5). Thus the SF-36 scales shows a positive effect of a TP-IAT even in patients who are not be able to wean off narcotics rapidly or at all either because of prior long-term induces opioid-induced hyperalgesia (37) or because of the duration of pain, neurological central sensitization occurs (38). Considering the long duration of use that makes weaning difficult even when pain is resolved, the inability to wean off narcotics per se is not a treatment failure when indeed the QOL did improve following the TP-IAT.

Figure 5.

SF-36 scale scores for Social Functioning and Role-Physical Limitations before and serially after TP-IAT in those weaned off versus those still on narcotics. The improvement was significant from baseline for both groups (p<0.001) but there was no significant difference between the trajectory of improvement for those on vs. not on narcotics.

The Integrated Survey asked additional questions to assess the impact of TPIAT over time on QOL (Table 5). In regard to pain transition, over 80% said they were much or somewhat better at each time point. Only 3–6% said they were worse than before the TP-IAT. In the Integrated survey, the mean pain rating prior to TP-IAT was 54, while at 6, 12 and 24–36 months after the TP-IAT it was 32, 31 and 24 (p<0.001).

Table 5.

Answers to Integrated Survey Questions of 123 Patients Undergoing TPIAT at the University of Minnesota Since 2008

| 6 months | 12 months | 24–36 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (N) | (64) | (33) | (48) | ||||

| Health Transition | ||||||||

| Much better now | 61% | (39) | 58% | (20) | 54% | (26) | ||

| Somewhat better now | 20% | (13) | 33% | (11) | 33% | (16) | ||

| About the same | 11% | (7) | 3% | (1) | 4% | (2) | ||

| Somewhat worse now | 8% | (5) | 6% | (2) | 6% | (3) | ||

| Much worse now | 2% | (1) | ||||||

| Pain Transition | ||||||||

| Much better now | 64% | (41) | 71% | (24) | 67% | (32) | ||

| Somewhat better now | 16% | (10) | 15% | (5) | 17% | (8) | ||

| About the same | 14% | (9) | 9% | (3) | 10% | (5) | ||

| Somewhat worse now | 3% | (2) | 3% | (1) | 6% | (3) | ||

| Much worse now | 3% | (2) | ||||||

| Recommend TPIAT to Family and Friends | ||||||||

| Definitely yes | 75% | (48) | 70% | (24) | 71% | (36) | ||

| Probably yes | 11% | (7) | 15% | (5) | 14% | (7) | ||

| Not sure | 11% | (7) | 9% | (3) | 6% | (3) | ||

| Probably not | 3% | (1) | 4% | (2) | ||||

| Definitely not | 3% | (2) | 3% | (1) | 4% | (2) | ||

| Overall Results of TPIAT | ||||||||

| Excellent | 51% | (33) | 43% | (15) | 54% | (27) | ||

| Very Good | 22% | (14) | 24% | (8) | 13% | (6) | ||

| Good | 11% | (7) | 24% | (8) | 23% | (11) | ||

| Fair | 8% | (5) | 9% | (3) | 8% | (4) | ||

| Poor | 8% | (5) | 2% | (1) | ||||

In regard to health transition, more than half said they were much better at each time point after TP-IAT and a third said they were somewhat better at each time point. Thus, more than 80% had better health at each time point. Nevertheless, 6 to 8% said they were somewhat worse than before the TP-IAT.

More than 70% of patients at each time point said they would definitely recommend the TPIAT to others while only 3–8% said probably or definitely not. The patients rated the overall results of TPIAT as excellent or very good in more than two-thirds of the patients, while 2–8% said the results were poor.

Impact of Previous Direct Surgery on the Pancreas on HRQOL and Pain Outcome Post TP-IAT

There were 23 patients in the SF-36/Integrated survey who had direct surgery on the pancreas prior to TP-IAT (10 with a Puestow, 10 with a Whipple, 5 with a distal pancreatectomy and 2 with Beger/Frey procedure) who could be compared to 142 without direct surgery for HRQOL and pain rating before and after TP-IAT. In regard to the SF-36 survey, the trajectory of improvement in the 10 scales after TP-IAT was the same for those with prior direct surgery and those without; including when it was broken down to those with a Whipple, Puestow or distal pancreatectomy. Of the patients with previous direct surgery, 87 % said their pain improved after the TP-IAT vs. 90% in those without previous surgery (p=ns). In those with previous surgery, pre-transplant pain rating was 54.3 and at one-year post-transplant was 33.4, a significant reduction (p<0.007). Patients with no previous direct surgery on the pancreas had pain rating pre-transplant of 53.6 and at one year 29.0 (p<0.001). Thus, a TP can provide pain relief when other surgery has failed, showing that the pain is intrinsic to the residual pancreas that remains after the other procedures.

Outcomes in Children

Outcomes in children are at least as good if not better versus adults. Of the 53 cases in the series, the 1, 5 and 10 year patient survival rates are 98%, 98% and 79%. In regard to islet function in children, in the cross-sectional analysis at 3 years, 55% are insulin independent, 25% have partial islet function and only 20 % are fully insulin-dependent, vs. 25%, 35% and 40% in the three function categories in adults.

Current insulin use post-transplant is known in 48 of the pediatric cases and 24 children are insulin independent (50%). The proportion of patients achieving insulin-independence was higher in preadolescent children (less than 13 years of age), compared to adolescents (age 13 to 18 years); 68% of preadolescent children (13/19) were insulin independent compared to 38% (11/29) adolescents (p = 0.04).

Thus, it is apparent that the younger the age the better the outcomes and pre-teenagers suffering from chronic pancreatitis should not be delayed in undergoing TP-IAT.

Discussion

Although many operations have been devised to treat painful chronic pancreatitis (4,6), TP is the only one that completely removes the root cause of the pain. When combined with IAT, it fulfills in part the principal to preserve pancreatic function, in this case endocrine only. In this single center series—the largest published to date—the capacity for TP to relieve pain, permit weaning of chronic narcotic therapy, and restore quality of life, while IAT preserves some degree of islet function in the majority of recipients are demonstrated. TPIAT should be considered as a first line surgical therapy for patient severely affected by chronic pancreatitis.

Historically, reluctance to refer patients for TP in part emulates from the brittle diabetes that results. However, IAT preserves endogenous beta cell function (C-peptide positivity) in 90% of patients, thereby preventing brittle diabetes in the majority of TP-IAT recipients. At three years, one third are insulin-independent, including a quarter of adults and half the children. A significant number of insulin-dependent patients maintain euglycemia on once daily basal insulin. Regardless of insulin use, goal glycemic control is maintained in most: hemoglobin A1c levels are <7% (the goal set by the American Diabetes Association) in over 80% of patients. Insulin-independence, C-peptide positivity, and goal glycemic control are more consistently achieved in those recipients with a moderate to high islet mass transplanted. However, even IAT recipients with the lowest islet yield group (<2500 IE/kg) were C-peptide positive in four of five cases and 71% maintained a mean glycohemoglbin <7.0%. The benefits of being C-peptide positive in terms of glycemic control and prevention of secondary complications of diabetes has been well documented (39), and complications are rare in those type 1 diabetics able to maintain a glycohemoglobin <7.0% (39). Although islet longevity was not a focus of this analysis, at 10 years, a third of the TP-IAT follow-up patients are still insulin-independent, suggesting long-term function and protection from diabetic complications is likely.

It should be noted that islet autografts are more durable than islet allografts (15). On average, twice as many IE/kg are needed for an allograft to induce insulin-independence or C-peptide positivity than for an autograft. Furthermore, even with a lower islet mass associated with and IAT, the attrition rate over time is half that of islet allografts.

Few factors reliably predict metabolic outcomes. In this series of cases, there is a strong association between islet yield and degree of function. Insulin is given liberally early on so as not to stress the beta cells during the engraftment period, in order to preserve beta cell mass. Islet yield is difficult to predict prior to surgery. There is a correlation retrospectively with degree of histopathologic changes, but the scatter is huge, with high yields in some very diseased pancreases and occasional low yields in minimal change disease (34). Thus, all patients are counseled that they must be willing to accept the risk of diabetes as a trade off for pain relief. It was shown the higher the stimulated C-peptide prior to surgery, the greater the probability of high islet yield (40). However, those with low stimulated values (41) are likely to become diabetic even without surgery, given the natural history of the disease in chronic pancreatitis (8), and possibly the liver is a better environment for islets caught in a sea of inflammation and scarring. Indeed, half of the patients classified as having C-peptide positive diabetes prior to TP-IAT remained C-peptide positive after the surgery (data not shown). Those patients with prior surgical drainage procedures or distal pancreatectomy on average have lower islet yields.

While preservation of beta cell function is important, amelioration of diabetes with the IAT is a secondary goal. Chronic pancreatitis is all about pain. Thus the primary goal of TPIAT is ultimately to relieve pain and restore quality of life. Pain management in chronic pancreatitis is difficult and most patients who come to surgery are narcotic-dependent (1) and, if of long duration (average 3.5 years in the series), may have opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), making withdraw difficult (37). Because of the long duration of pain, some patients have a neurological syndrome known as central sensitization resulting in persistent pain to at least some degree after surgical treatment (38). Thus, in this series, as in those of other’s (3,42,43), about 40% were static or still weaning off narcotics at two years after TP-IAT. Never the less, every analysis was statistically favorable in regard to pain control: the medical record review, the SF-36 survey and the integrated survey all confirmed statistically and clinically significant improvements, whether the patients were or were not on narcotics. In addition, in patients with previous direct pancreatic surgery that failed to relieve pancreatic pain, relief occurred after TP-IAT showing that indeed the pain resided in the residual pancreas and was not from another source.

The SF-36 Integrated Survey showed a significant improvement in every HRQOL scale measured after TP-IAT. Similar findings have been documented by other centers’ series, including University of Cincinnati, (3,43), and the University of Leicester in England (22,42,44). Quality of life improved regardless of whether the patients were insulin-independent or insulin-dependent, although it was greater in those who were insulin-independent, demonstrating the value of preserving beta cell mass. Likewise, HRQOL improved in patients who had or had not yet weaned of narcotic analgesics, and there was no difference in degree of improvement between the two groups in all eight scales as well at the component summaries, physical and mental. Thus failure to wean of narcotic analgesics does not necessarily mean the operation was a failure, given the improvement in all the QOL scales, including pain.

The two largest series of TP-IAT cases after Minnesota are the University of Cincinnati (3,43), and the University of Leicester in England (22,42,44). The demographics at Cincinnati are similar to Minnesota, a preponderance of females (more likely the become insulin-independent than males), low incidence of alcohol as the etiology, the same incidence of genetic linked disease, and in both series, insulin-independence correlates with islet yield. In contrast, in the Leicester series, males predominate, alcohol is the most common etiology, and islet yield did not correlate strongly with function. However, in all three centers, glycemic control was good in the majority of patients with normal or near normal glycohemoglobins.

Selection of the patients for TP-IAT is crucial for good outcomes, and a consensus is reached by the workgroup on every patient who undergoes the surgery. As noted in the QOL life studies, a good outcome is achieved in the vast majority of patients who undergo TP-IAT but there is a small subset that did not benefit. The characteristics of the latter group were not substantially different than in those who did benefit. Thus it is a tight line between rejecting those who will benefit (most) and accepting those who will not (few).

Currently about 2/3 of the patients with chronic pancreatitis who come to TP-IAT have had an endoscopic duct drainage procedure with a sphincterotomy and temporary stent placement in an attempt to reduce intra-ductal pressure or remove stones (5). Most cases of chronic pancreatitis are small duct disease, but even if the duct is dilated and pain persists after endoscopic drainage, the approach is to go directly to TP-IAT in order to ablate the source of the pain and avoid the low islet yield when a TP-IAT is done after surgical duct drainage. Indeed the current paradigm is to offer TP-IAT to most patients after failure of endoscopic duct drainage to relieve pain or in those in whom failure of the endoscopic approach is predictable.

About a quarter of the patients (mostly young women with past history of acute pancreatitis) have minimal change chronic pancreatitis (34,45) with no calcifications, but who still meet the criteria for TP-IAT as outlined in the Methods section. Chronic pancreatitis was documented histologically and there was pain resolution when <3/9 criteria were present (33). Thus, minimal change on imaging does not deter us from TP-IAT as long as the other criteria listed are met (45).

There is no standard surgical treatment for chronic pancreatitis. If medical measures or endoscopic duct drainage procedures fail, all surgical procedures except a Whipple operation are associated with decreased islet yield should pain not be relieved and a TP-IAT be necessary. Thus, for patients in whom the disease seems truly head dominant (difficult to discern) and willing to risk persistence of pain in order to minimize the risk of diabetes, a Whipple operation (ideally with an IAT) may be appropriate (46). In the series, nearly all patients who failed to have pain relief with a Whipple operation (most done elsewhere) had pain relief with a completion pancreatectomy with sufficient islet yield for a good metabolic. The fact that pain improved after TP shows that the pain was intrinsic to distal pancreas and did not reside solely in the head.

In regard to the surgical aspects of TP-IAT, the most important point is to preserve blood supply to the pancreas until the moment it is removed, minimizing warm ischemia to the islets (47).

The operative mortality rate in the 30 year series is 1.2%. This is low compared to a review of older literature on TP by itself (4). As far as surgical complications requiring reoperation, a 16% incidence is not unexpected given the magnitude of the operation. Bleeding was the most common complication, in part related to the increased portal pressure and need for heparin following the IAT. There is reluctance in doing IAT without the heparinization because of the previous experience with portal vein clotting and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) when heparin was not used and because of the small incidence of non-occlusive portal vein thrombi. There are no cases of DIC in the Minnesota series. The current protocol on tissue volume infused and upper limit of portal vein pressure has cut the incidence of bleeding in half (32).

Other surgical consideration includes the timing of TP-IAT for painful chronic pancreatitis. Operating earlier rather than later would facilitate narcotic withdrawal, avoid opioid induced hyperalgesia (37) and central pain sensitization (38), as well as the narcotic bowel syndrome that is so prevalent in this population (48). It also would be associated with a larger beta cell mass in the diseased pancreas (8,41).

TP-IAT can also reduce if not totally eliminate the cancer risk in hereditary pancreatitis. Of those with PRSS1 genetic mutations variety, the association between chronic pancreatitis and cancer has been well established (49). Over time, the risk approaches 40 %. A TP by itself would totally eliminate the cancer risk but even with an IAT the risk must be low given the huge reduction in pancreatic tissue volume prior to embolization to the liver. In the entire series, no patients are known to have had pancreatic cancer in the liver.

Finally, a word about the children (50,51). They comprise about an eighth of the experience and nearly all have dramatic improvement in HRQOL (24). The important point is that they do even better than adults, particularly the preteen group where two-thirds are insulin-independent.

In summary, total pancreatectomy is effective in alleviating intractable pain caused by chronic pancreatitis. There are surgical risks associated with the procedure. Except for the high incidence of reoperation for bleeding because of heparinization at the time of IAT, the complication rate is similar to that reported for a Whipple procedure or other operations on the pancreas. A pain syndrome can continue in some patients (although greatly reduced), most likely related to the long duration of pain (central sensitization) and of narcotic use prior to the operation. IAT results in C-peptide positivity in most patients and a third are insulin-independent, more than half of the children and a quarter of the adults. Having endogenous beta cells function makes it relatively easy to have good glycemic control and maintain a normal or near normal glycohemoglobin after TP, with all of the intended benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Louise Berry R.N., B.S., C.C.T.C. and Marie Cook R.N., C.N.P., M.P.H., C.C.T.C. for their superb care of the patients in these studies.

The authors also express appreciation to Ms. Jessica Young for preparing the manuscript and figures for publication, over and over again.

Reference List

- 1.Braganza J, Lee S, McCloy R, McMahon M. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet. 2011;377(9772):1184–1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gachago C, Draganov P. Pain management in chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(20):3137–3148. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad S, Wray C, Rilo H, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: recent advances and ongoing challenges. Curr Probl Surg. 2006;43:127–238. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen DK, Frey CF. The Evolution of the surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2010;251:18–32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ae3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanna S, Tandon RK. Endotherapy for pain in chronic pancreatitis. J of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;23:1649–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King JC, Abeywardina S, Farrell JJ, Rebber HA, Hines JO. A modern review of the operative management of chronic pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2010;76(10):1071–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blondet J, Carlson A, Kobayashi T, et al. The role of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin N Am. 2007;87(6):1477–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malka D, Hammel P, Sauvanet A, et al. Risk factors for diabetes mellitus in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(5):1324–1332. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutherland DER, Matas AJ, Najarian JS. Pancreatic islet cell transplantation. Surg Clin No Amer. 1978;58:365–382. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farney A, Najarian J, Nakhleh R. Autotransplantation of dispersed pancreatic islet tissue combined with total or near-total pancreatectomy for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1991;110:427–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najarian JS, Sutherland DER, Matas AJ, Goetz FC. Human islet autotransplantation following pancreatectomy. Transplant Proc. 1979;11:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najarian JS, Sutherland DER, Baumgartner D, et al. Total or near total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1980;192:526–542. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198010000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahoff D, Papalois B, Najarian J, et al. Autologous islet transplantation to prevent diabetes after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 1995;222:562–579. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199522240-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Dunn DL, et al. Transplant options for patients undergoing total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.024. discussion 568–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland D, Gruessner A, Carlson A, et al. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2008;86(12):1799–1802. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819143ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron JL, Mehigan DG, Broe PJ, Zuidema GD. Distal pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1981;193(3):312–317. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198103000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinshaw DB, Jolley WB, Hinshaw D, Kaiser JE, Hinshaw K. Islet Autotransplantation After Pancreatectomy for Chronic Pancreatitis With a New Method of Islet Preparation. Am J Surg. 2011;42:118–122. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(81)80020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takita M, Naziruddin B, Matsumoto S, et al. Variables associated with islet yield in autologous islet cell transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Proc. 2010;23(2):115–120. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argo J, Contreras J, Wesley M, Christein J. Pancreatic resection with islet cell autotransplant for the treatment of severe chronic pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2008;74(6):530–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berney T, Rudisuhli T, Oberholzer J, et al. Long-term metabolic results after pancreatic resection for severe chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2000;135(9):1106–1111. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.9.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon J, DeLegge M, Morgan K, Adams D. Impact of total pancreatectomy with islet cell transplant on chronic pancreatitis management at a disease-based center. Am Surg. 2008;74(8):735–738. doi: 10.1177/000313480807400812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clayton H, Davies J, Pollard C, et al. Pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation for the treatment of severe chronic pancreatitis: the first 40 patients at the Leicester General Hospital. Transplantation. 2003;76:92–98. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000054618.03927.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad S, Lowy A, Wray C, et al. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(5):680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellin MD, Freeman M, Schwarzenberg S, et al. Quality of Life Improves for Pediatric Patients After Total Pancreatectomy and Islet Autotransplant for Chronic Pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland DE, Goetz FC, Najarian JS. Living-related donor segmental pancreatectomy for transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1980;12:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquez S, Marquez TT, Ikramuddin S, et al. Laparoscopic and da Vinci robot-assisted total pancreatectomy, duodenectomy, and islet auto transplantation: Case report of a definitive minimally invasive treatment for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2010;39:1109–1111. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181df262c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kin T. Islet isolation for clinical transplantation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:683–710. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balamurugan AN, Breite AG, Anazawa T, et al. Successful human islet isolation and transplantation indicating the importance of class 1 collagenase and collagen degradation activity assay. Transplantation. 2010;89(8):954–961. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d21e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anazawa T, Matsumoto S, Yonekawa Y, et al. Prediction of pancreatic tissue densities by an analytical test gradient system before purification maximizes human islet recovery for islet autotransplantation/allotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91(5):508–514. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182066ecb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricordi C, Gray DW, Hering BJ, et al. Islet isolation assessment in man and large animals. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1990;27(3):185–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02581331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balamurugan AN, Bellin MD, Papas K, et al. Maximizing Islet Yield from Pancreata with Chronic Pancreatitis for Use in Islet Auto-Transplantation Requires a Modified Strategy from Islet Allograft Preparations. Pancreas. 2011;40(8):1312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilhelm JJ, Bellin MD, Balamurugan AN, et al. A Proposed Threshold for Dispersed-Pancreatic-Tissue-Volume (TV) Infused During Intraportal-Islet-Autotransplantation (IAT) after Total-Pancreatectomy (TP) to Treat Chronic-Pancreatitis (CP) Pancreas. 2011;40(8):1363. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi T, Manivel J, Bellin M, et al. Correlation of pancreatic histopathologic findings and islet yield in children with chronic pancreatitis undergoing total pancreatectomyand islet autotransplantation. Pancreas. 2010;39(1):57–63. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b8ff71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi T, Manivel JC, Carlson AM, et al. Correlation of Histopathology, Islet Yield, and Islet Graft Function After Islet Autotransplantation in Chronic Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40(2):193–1. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181fa4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):570–587. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolf CJ. Central Sensitization: Implications for diagnosis and treatment of pain. PAIN. 2011;152:S2–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali MA, Dayan CM. Review: The importance of residual endogenous beta-cell preservation in type 1 diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2009;9:248–253. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellin M, Blondet J, Beilman G, et al. Predicting islet yield in pediatric patients undergoing pancreatectomy and autoislet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(4):227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui Y, Anderson DK. Pancreatogenic diabetes: special considerations for management. Pancreatology. 2011;11(3):279–294. doi: 10.1159/000329188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcea G, Weaver J, Phillips J, et al. Total pancreatectomy with and without islet cell transplantation for chronic pancreatitis: a series of 85 consectuive patients. Pancreas. 2009;38(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181825c00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutton J, Schmulewitz N, Sussman J, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation as a means of treating patients with genetically linked pancreatitis. Surgery. 2010;148(4):676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb M, Illouz S, Pollard C, et al. Islet auto transplantation following total pancreatectomy: a long-term assessment of graft function. Pancreas. 2008;37(3):282–287. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31816fd7b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vega-Peralta J, Manivel J, Attam R, et al. Accuracy of EUS for diagnosis of minimal change chronic pancreatitis (MCCP): Correlation with histopathology in 50 patients undergoing total pancreatectomy (TP) with islet autotransplantion (IAT) Pancreas. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruckers F, Distler M, Hoffmann S, et al. Quality of life in patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1143–1150. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Desai CS, Stephenson DA, Khan KM, et al. Novel technique of total pancreatectomy before autologous islet transplants in chronic pancreatitis patients. JACS. 2011;213(6):e29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grunkemeier DMS, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, Drossman DA. The narcotic bowel syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and managment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1126–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitcomb DC. Inflammation and Cancer. V. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G315–G319. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00115.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bellin MD, Carlson AM, Kobayashi T, et al. Outcome after pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:37–44. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815cbaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellin M, Sutherland D. Pediatric islet autotransplantation: indication, technique, and outcome. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(5):326–331. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]