Abstract

Oocyte cryopreservation has become an essential tool in the treatment of infertility by preserving oocytes for women undergoing chemotherapy. However, despite recent advances, pregnancy rates from all cryopreserved oocytes remain low. The inevitable use of the cryoprotectants (CPAs) during preservation affects the viability of the preserved oocytes and pregnancy rates either through CPA toxicity or osmotic injury. Current protocols attempt to reduce CPA toxicity by minimizing CPA concentrations, or by minimizing the volume changes via the step-wise addition of CPAs to the cells. Although the step-wise addition decreases osmotic shock to oocytes, it unfortunately increases toxic injuries due to the long exposure times to CPAs. To address limitations of current protocols and to rationally design protocols that minimize the exposure to CPAs, we developed a microfluidic device for the quantitative measurements of oocyte volume during various CPA loading protocols. We spatially secured a single oocyte on the microfluidic device, created precisely controlled continuous CPA profiles (step-wise, linear and complex) for the addition of CPAs to the oocyte and measured the oocyte volumetric response to each profile. With both linear and complex profiles, we were able to load 1.5 M propanediol to oocytes in less than 15 min and with a volumetric change of less than 10%. Thus, we believe this single oocyte analysis technology will eventually help future advances in assisted reproductive technologies and fertility preservation.

Introduction

Since the first pregnancy using cryopreserved mature human oocytes was reported in 1986,1 oocyte cryopreservation has emerged as an important clinical need for the treatment of infertility and fertility preservation. All cryopreservation protocols share the common goal of cooling cells to subzero temperatures to effectively stop biochemical activity, followed by the subsequent return to physiologic temperatures. Over the last 20 years, protocols for the cryopreservation of oocytes have been proposed with conventional CPAs (e.g., dimethyl sulfoxide, glycerol, propane-1,2-diol (PROH)). Difficulties associated with CPA concentrations result from the potential toxic effects as well as the changes in osmotic pressure associated with their loading and removal.2,3

During the loading and removal of CPAs, cell volume changes occur as CPAs and water enter and exit the cell in response to osmotic and chemical gradients. The changes in cell volume associated with changes in osmotic pressure can impair a cell’s viability.4,5 It has also been reported that the volume changes associated with anisosmotic exposure causes the disruptions of the spindles in MII oocytes.6 Although the step-wise addition of CPAs was introduced to reduce the osmotic stress on the oocyte, the increments in the number of step are physically limited because of long exposure times to CPAs and also it requires tedious and complicated procedures for the measurements with potential for experimental errors. Thus, the determination of the optimal CPA loading profiles to minimize the volume changes or osmotic stresses on oocytes is essential for the successful cryopreservation by enhancing the yield and quality of preserved oocytes. Therefore, a fine balance is required to limit the toxic effects of CPAs while simultaneously removing a sufficient volume of intracellular water. However, the optimal protocol for reducing the damages is still controversial and the techniques lack sufficient quality to become common laboratory practice.

To minimize oocyte volumetric responses to CPAs and to improve oocyte cryopreservation protocols, we undertook a new approach that combines microfluidic and biophysical modeling tools. Microfluidic technologies have gained momentum in studies of cellular behavior and interactions,7-9 single cell analysis10 and cyropreservation.11-14 Our present study demonstrates that microfluidic device is an efficient tool for creating linear and complex CPA loading profiles to avoid potential osmotic and toxic damage to the oocytes. The proposed microfluidic device fulfils several important functions on a single platform. It spatially localizes a single oocyte in a simple manner; it creates continuous CPA profiles to overcome the limitations of step-wise CPA addition; it allows measuring the membrane properties of oocytes such as the hydraulic conductivity (Lp), solute permeability (Ps) and reflection coefficients (σ). Using this microfluidic system we developed a cryopreservation protocol to achieve CPA loading in less than 15 min with less than 10% reduction of the oocyte volume from the isoosmotic values.

Materials and methods

Design of microfluidic device

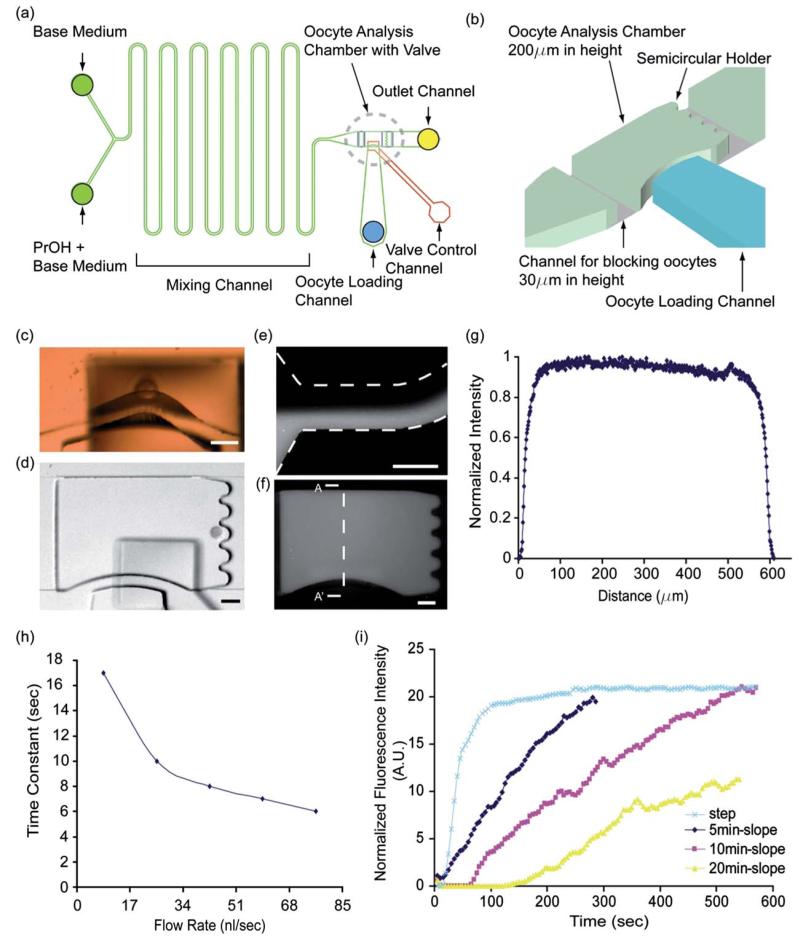

We built a two-layer PDMS device on glass, which incorporates a microfluidic network layer (lower layer) and a control layer (upper layer) in order to handle single mouse oocyte for the measurement and minimization of the volume change excursions. Because oocytes are large, ~75 μm in diameter, and float freely in the channel, a special design had to be considered as shown in Fig. 1. The upper PDMS slab (~5 mm in thick) contained a channel and actuation chamber (500 μm 400 μm) for the pneumatic valves on its bottom surface. The lower PDMS slab (~500 μm in thick) contained microfluidic networks which had two inlet channels merging to a mixing channel (2cm in length), an oocyte analysis chamber (width 600 μm × length 900 μm) with a valve and an outlet channel (Fig. 1a, b). Two shallow channels (width 600 μm × length 200 μm height 30 μm) were located between the chamber and inlet/outlet channel as barriers to prevent the loaded oocyte from moving to the direction of inlet/outlet channel.

Fig. 1.

(a) The design of microfluidic networks in this study; A microfluidic chamber (width 600 μm × length 900 μm) and a two-inlet mixer positioned upstream from the oocyte chamber were fabricated on the first PDMS layer by using multilayer (30 μm and 200 μm thickness) soft lithography. The second top layer of PDMS layer with a valve actuation chamber (width 400 μm and length 500 μm) was bonded on it. (b) The microfluidic oocyte analysis chamber; Three dimensional schematic drawing of the dotted circle areas of (a). (c) Oocyte passing under the valve in active position. (d) A captured single oocyte in the oocyte analysis chamber and holder. Scale bars represent 100 μm. [E-G[ Fluorescent intensity profile inside the oocyte chamber demonstrates efficient mixing of the two inlet solutions. (e) Fluorescent image with two streams at the inlet channel. (f) Fluorescent image of fully mixing of the two streams at the analysis chamber. (g) Intensity of fluorescence across the chamber (A-A′) (h) Time constants (fluid exchange time in chamber) with different flow rates at the analysis chamber. Reduced by 6 s with 85 nl s−1 flow rate. (i) Various concentration gradients such as 0 min (or “Step”), 5 min, 10 min and 20 min slopes were obtained on the microfluidics system using a computer controlled syringe pump.

Fabrication for microfluidic device

Two separate molds were prepared on silicon wafers using standard photolithography techniques as previously described.15 Briefly, the mold for the control channels (the upper layer) used one 200 mm thickness layer of SU8 epoxy (Microlitography Corp., Newton, MA), photopatterned through a Mylar mask (Fineline Imaging, Colorado Springs, CO) and processed according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The mold for the fluidic network layer (the lower layer) used two layers (30 mm and 200 mm) of SU-8 epoxy. The thin layer was processed first and then the thicker layer was aligned and exposed in similar conditions on top of the first one.

Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS, Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To create microchannels in PDMS, a 5 mm thick layer, and separately ~500 μm layer were cast over the control and network molds, respectively. After the thick layer (control) PDMS platform was peeled from the wafer and cut into pieces (1.5 × 2.5 cm), holes were punched through the control layer using a sharpened 25-gauge needle (NE251PL, Small Parts Inc, Miami Lakes, FL). The peeled control layer and thin layer on silicon wafer were exposed to oxygen plasma (50 W, 2% O2, 25 s) in a parallel plate plasma asher (March Inc., Concord, CA) and bonded after contact and heated (100°C, 10 min). Precise alignment between the control and the thin layer patterns on wafer was achieved under a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ8, Leica, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). After peeling the bonded layer from wafer, the inlets and outlets for the network layer were subsequently punched using the same needle size. To prevent the bonding of the control valve on the slide glass, before oxidization the valve was lifted up by applying vacuum on the channel in the control layer with a syringe. The bonding surfaces of the PDMS and the glass slides were treated with oxygen plasma. After the assembly of the device, the control valve was released by removing the vacuum. The rest of the device except the valve was irreversibly bonded.

Retrieval of oocytes

The 6 week-old B6CBF1 female mice (Charles River Laboratories,Boston, MA) were superovulated with 7.5 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotrophin (PMSG) (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and 7.5 IU of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) (Sigma–Aldrich) given by intraperitoneal injections 48-hours apart. Fourteen hours after hCG injection, females were anesthetized with avertin (Sigma–Aldrich) then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and their oviducts were removed. The cumulus-oocyte complex was released from the ampullary region of each oviduct by puncturing the oviduct with a 27-gauge needle. Cumulus cells were removed by exposure to hyaluronidase (80iu/ml) (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) for 3 min and washed 3 times with HTF medium with 10% FBS. Oocytes were transferred and cultured in human tubal fluid (HTF) medium (Irvine Scientific) (Quinn et al., 1995) containing 10% fetal bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air until they were tested on microbioreactor. All animal experiments were carried out with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Cryopreservation solutions

Two solutions were used for the volume change excursions: 1) A base medium, HEPES-buffered physiological salt solution (FHM; Specialty Media, Lavallette, NJ, USA) containing 20% FBS and 2) 1.5M Propane-1,2-diol (PROH) (Sigma–Aldrich) in FHM as a cryoprotectant. All cryoprotectant solutions were filter-sterilized and stored at 4°C prior to use. The concentrations and type of cryoprotectant used were similar to those used in traditional slow freezing protocols for human oocytes.16

Oocyte volume change measurements

The following steps were used to load the oocytes into the microbioreactor. 1) Isolated mature oocytes were placed into HTF medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2) The oocytes were transferred to an organ dish with a base medium (FHM medium containing 20% FBS), 3) Using a Stripper (Midatlantic Diagnostics, Inc, USA), load one or two oocytes into the analysis chamber filled with the base medium, and 4) two 1ml syringes (Hamilton, USA) containing the base media and 1.5M PROH separately were used to generate the diverse concentration profiles with computer controlled syringe pumps (Cetoni Gmbh, Germany). Volumetric responses of oocytes to the concentration profiles were recorded every 3 s using a CCD camera (SPOT imaging/Diagnostic Instruments, USA) mounted on an inverted microscope (TE2000-S, Nikon, Japan) with 10× objective lens. Also the loaded oocytes can be easily retrieved and become available for subsequent steps. The retrieval is performed by applying back flow from exit channel and pushing oocytes back to the inserted Stripper tip at loading channel. For the measurements of flow profiles, fluorescence imaging were recorded in a similar way. Two 1ml syringes (Hamilton, USA) containing distilled water and 1mM fluorescein (Sigma–Aldrich) in distilled water were used to generate the diverse profiles and the images with fluorescence were recorded every 3 s. The oocyte volume at each time point was calculated from the projected cross-sectional areas, assuming the cross-sectional area (C) to be that of a sphere, using the relationship: Vol(4π/3)(C/π)3/2.17,18 The public domain software Image J (National Institute of Health, USA) was used for the analysis of the cross-sectional area (C).

Numerical equations for oocyte volume changes and membrane permeability parameters

The hydraulic conductivity, solute permeability, and reflection coefficient were calculated using coupled differential equations to describe volume changes and solute movement across a membrane as a function of time:19

| (1) |

| (2) |

where S is the amount of solute penetrating into the cell, Lp is the membrane hydraulic conductivity, A is the cell surface area, R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, πi is the intracellular osmolality, and πe is the extracellular osmolality, Ps is the solute permeability, ΔCs is the difference between extracellular and intracellular solute concentration, σ (sigma) is the reflection coefficient, is the mean solute concentration across the membrane, and the subscripts n and s refer to the non-permeating solute and permeating solutes, respectively. Intracellular osmolality was determined from the Boyle van’t Hoff relationship:

| (3) |

where V is the equilibrium cell volume, π is the experimental osmolality, πo is the isotonic osmolality, Viso is the isotonic cell volume, and Vb is the osmotically inactive fraction of the isotonic cell volume, which was previously determined to be 0.2.20

Numerical simulation for complex profiles

To find an ideal CPA loading profile, we simulated potential CPA loading protocols and selected for shorter loading time and minimal cell volume change. We started by considering every possible path for CPA loading in time considering 1% resolution in concentration up to 50% overshoot from maximum concentration level, and 6 s resolution in time. The target was to select and compare the profiles that reached the desired CPA concentration at 15 min, in balance with the intracellular CPA concentration and final cell volume within 99% of the cell original volume. At this resolution, the number of possible protocols in the absence of any restrictions was ~2.6e + 326. To reduce the large number of permutations, loading profiles that lead to cell volume changes greater than 18% at any time were removed and not followed to the end. The permutations were divided into 12 different matrices at each time step and evaluated using Matlab code run in parallel on a 12-processor cluster. For example, at the first time step there were 22,500 possibilities, split and evaluated in 12 parallel processes of which several thousand were then rejected due to constraint violation. Each of those that satisfied the constraints had another 150 permutations associated with it for the next time step and were separated and evaluated in parallel and the process continued until the end time step.

Results

Oocyte handling in the microfluidic device

We built a simple microfluidic device that combines an oocyte trap and a fluidic mixer for generating various concentration gradients. The oocyte trap has micro-structured valves that are used to precisely handle and trap individual oocytes inside the microfluidic device. In the inactive position, the transversal structure rested on the glass. Upon actuation, the transversal barrier was lifted by the upward deformation of the membrane into the valve control channel. The excursion of the membrane was large enough to allow passage of an oocyte up to 100 μm in size (Fig. 1c). The semicircular holders were designed for securely holding single oocyte for further analysis. After entering the chamber through the opened valve, oocytes are positioned at the semicircular holders (90 μm in diameter) allowing single oocyte to fit for easy analysis of its volume change (Fig. 1b and d).

We estimated the shear stresses on the oocyte in the microfluidic devices using 3D computational simulations (COMSOL, Inc, USA). Our simulations show that the oocyte analysis chamber (900 μm ×600 μm Μ200 μm) behaves as a diffuser and reduces flow velocity into 7.1 cm s−1 (average velocity in chamber) while the introducing flow velocity in the shallow channel (channel for blocking oocyte) is relatively high (Supplementary Figure 1a†). Thus, an oocyte placed in the end of chamber experiences a slow flow on most of its surface, and only small sections located near the exit channel experience an increased flow rate. Based on the simulated flow velocity profiles, the estimated shear stress on the oocyte is approximately less than 2.5 ~3.5 dyne/cm2 in most regions and the value goes up to ~70 dyne/cm2 in localized parts near the outlet channel. The effects of the shear stress on embryo developments have been studied in several groups.8,21 While these studies were focused on the long terms effects of flow (24 to 96h), we expected no significant effects of shorter exposures. It is also believed that the zona pellucida surrounding the plasma membrane of oocyte protects oocyte from the external mechanical stresses and give oocyte more tolerances to shear stresses.

To estimate the viability of the oocytes inside the microfluidic devices we monitored the morphological changes of the oocytes. Morphological evaluation is an acceptable method for assessing oocyte viability in IVF clinics and research labs. For example, the zona pellucida will be torn out when the mechanical stresses are too high and the color of cytoplasm becomes instantly dark when oocyte is dead. During our experiments, we observed no changes in oocyte’s morphology, including its cytoplasm color (N = 20) and intactness of zona pellucida (Supplementary Figure 1b†). Furthermore, total handling times are shorter than CPA exposure times. Combining the estimated shear stress and morphological evaluations, we believe oocytes are viable during the loading of CPA on the microfluidic device.

Cryoprotectant concentration control in the microfluidic device

Various concentration gradients were obtained by using computer programmable syringe pumps. Fluid from two syringes filled with cryoprotectant and buffer are mixed in different ratios in a simple channel, long enough for two parallel streams to mix by diffusion. To probe the formation of concentration profiles, two 1 ml syringes containing distilled water and fluorescein separately were connected to the two inlet ports. By adjusting the flow rate of the distilled water and fluorescein in each syringe, we were able to obtain linear profiles with diverse slopes. The accuracy of mixing and time constant (the time it takes the system’s step response to reach 63% of its final (asymptotic) value) of media exchange were characterized with fluorescence intensity and optimized for oocyte analysis. The evenly distributed intensity of fluorescein across the chamber (Fig. 1e, f and g) showed that the mixing channel efficiently worked at in the given flow rate (85 nl s−1). The time constant of media exchange in the chamber was decreased as the flow rate increased (Fig. 1h). The 85 nl s−1 was used as the net flow rate for oocyte analysis because the six second time constant was enough for the oocyte volume change experiment.

Oocyte volume response with “step” and “linear” profiles of CPA concentration

For experimental purposes, step and linear concentration changes over 5 min, 10 min and 20 min were tested using the microfluidic system (Fig. 1i). For example, to get the 10 minslope profile, the flow rate of fluorescein (or CPAs) linearly increases from 0 to 85 nl s−1 while the flow rate of distilled water (or Base Medium) linearly decreases from 85 to 0 nl s−1 in 10 min. The total flow rate (85 nl s−1) was constant over the period. These slopes were used as CPA concentration gradients for the oocyte volume excursion experiments. After the oocyte sat in the semicircular holders in the analysis chamber, 1.5 M PROH was introduced into the chamber with a Step profile (a sudden change of media from 0 M PROH to 1.5 M PROH with the flow rate 85 nl s−1) similar to conventional studies. The oocyte shrank gradually from its original volume and reached a maximum volume change (approximately 25~30% of original) at around 40 s after the start of the initial volume change and then gradually recovered its volume (Supplementary movies are also available on online†). We measured the volumes of N = 5 oocytes and the average volume change excursion were plotted in Fig. 2a for Control and measured data (Supplementary Figure 2†) for curve fitting. The volume change excursion of oocytes under the sudden exposure (“step control”) to the PROH is in agreement with the volume excursions reported using microperfusion techniques.22

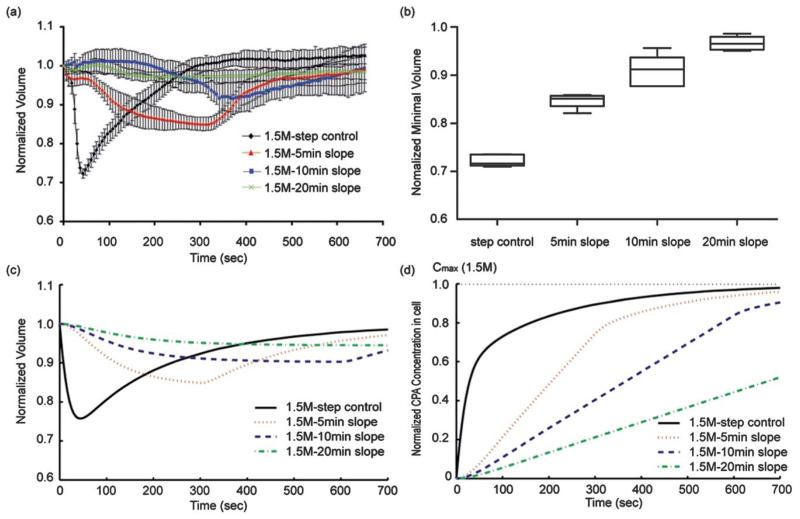

Fig. 2.

Experimental oocyte volumetric responses to the four different profiles. (a) Volume excursion becomes smaller with the increase in the concentration slope. In the case of the 10 min-slope, the volume excursion was dramatically reduced by less than 10% compared to the 25~30% from the “step control”. (b) Box-whiskers plot (Min to Max) of the minimal volume of oocyte (N = 5 for each condition). (c) Calculated oocyte volume change excursions with three flow profiles. (d) Calculated CPA concentration inside oocyte on the course of the external exposure of the three different CPA profiles.

We also measured the volume of N = 5 oocytes in three different conditions: 5 min-, 10 min-, and 20 min- linear slopes. The experimental results with oocytes showed that the volume change excursion from the “10 min–slope” was reduced to less than 10% compared to the 25% volume change from the “Step control” as predicted from the simulation. A 15% volume change was recorded for the “5 min-slope” protocol. Less volume change (~3%) was recorded for the “20 min-slope” than for the “10 min-slope” (~9%). However, the time of exposure to CPA is half for the “10 min-slope” compared to the “20 min-slope”, and the beneficial effect of smaller volume change is offset by the longer exposure to the CPA. The minimal volumes at each condition are 0.72 ± 0.01, 0.85 ± 0.02, 0.91±0.03, and 0.97± 0.01 for step control, 5 min-, 10 min-, and 20 min-slope, respectively (Fig. 2b). Thus, the “10 min-slope” is a practical profile for CPAs loading using the microfluidic device, demonstrating that the proposed microfluidic device can be used as a tool for single oocyte manipulation.

From the measured volume with a “step” profile in Fig. 2a, Lp (0.50±0.03 mm/atm/min), Ps (0.32±0.02 μm s−1) and σ (0.50 ±0.03) were obtained respectively to predict the oocyte responses to the three flow profiles of 1.5 M PROH(Fig. 2c). The simulated results corresponded well to the experimental results by showing that the volume change of an oocyte can be reduced from ~25% (“step control”) to ~15% (“5 min-slope”), ~10%(“10 min- and slope”), and ~15%(“20 min-slope”) as the PROH concentration slope decreases.

Although minimal volume change was achieved with a linear loading protocol compared to a step-wise change, it is important to assure that appropriate intracellular CPA concentrations are also achieved for protection of the oocytes during the subsequent freezing. The simulated result (Fig. 2d) supported that the linear profiles of CPA provide the appropriate level of the intracellular CPA concentration. The accumulated amount of CPA exposure to oocytes over 10 min was reduced to 75% (“5 min-slope”) and 50% (“10 min-slope”) of the amount of the “step control”, which was calculated by integrating the intracellular CPA concentrations profiles over 10 min. The reduced total amounts of CPA exposure within the given time may reduce the osmotic stresses and CPA toxicity which oocytes experience during the conventional step-wise CPA loading.

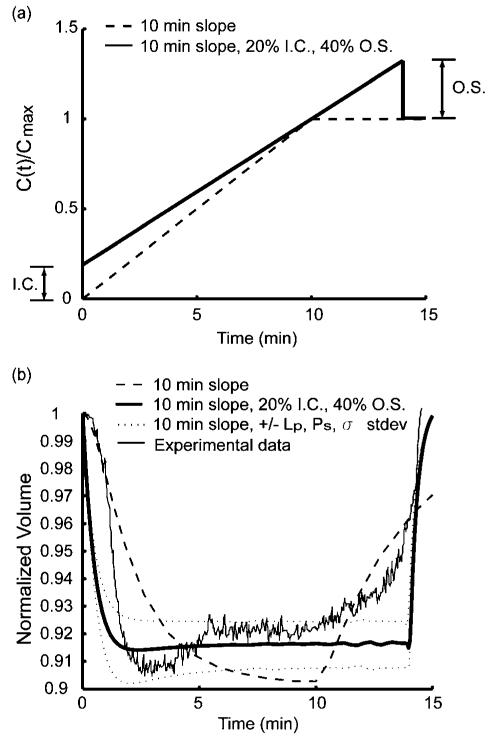

Complex CPA loading protocol using microfluidics

The proposed microfluidic device can generate more complex protocols at will (ex. combined step-wise and linear profiles) rather than just one simple protocol such as a step-wise or a linear profile. One interesting finding from the numerical simulation for the “optimized” profile described in Material and Methods was that cell volume recovers in less time if the concentration is overshot from its target value (Supplementary Figure 3a,b†). It is important to note that this brief overshoot (O. S.) would be very difficult to control using the traditional methods for CPA loading, but could be easily implemented using our microfluidic device. We also found that the initial concentration condition (I.C.) had a strong influence on the maximum relative cell volume change (Supplementary Figure 3c,d†). However, changing the initial condition had only a small effect on the equilibrium time. This implies that with optimal concentration functions, a tradeoff between the volume change and the total CPA loading time to equilibrium exists. For example, if an equilibrium time of less than 15 min is sought after, our simulations predict that a concentration profile with 20% initial concentration and 40% overshoot would be the optimal way to achieve the smallest cell volume change during loading (Supplementary Figure 3e,† Fig. 3a). Compared to the “10 min- slope” with 0% I.C. and 0% O.S., the complex profile gives both faster equilibrium time and less volumetric change (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

“Optimized” loading profile and oocyte volumetric responses. (a) Ideal Initial condition and overshot amount can be determined from the desired equilibrium time. 10 min-slope with and without 20% Initial condition (I.C.) and 40% overshoot (O.S). (b) The volumetric responses of the profiles from 10 min-slope, 10 min-slope with 20% I.C., 40% O.S., 10 min-slope (20% IC, 40% O.S.) with the Max and Min of standard deviation of Lp, Ps, σ. and an experimental oocyte volumetric responses to the optimal profile (10 min-slope with 20% I.C. and 40% O.S.).

A good match between the the measured volumetric responses of oocytes and the simulated “optimal” CPA loading profile, confirms the accuracy of the model and simulations (Fig. 3b). Compared to the volumetric response to the simple linear “10 min-slope” profile, the volumetric response to the optimized profile with 20% I.C. and 40% O.S. has gains of ~2% in minimal volume change and of ~4% in original volume given recovery at the 15 min equilibrium time.

To understand the effect of cell to cell variation of the permeability parameters (water permeability, solute permeability, and the reflection coefficient) on the volume change, a numerical parametric simulation was performed. By evaluating these parameters within their standard deviations in Table 1, we found that oocytes with the fastest permeability to solute and slowest permeability to water and a smaller reflection coefficient yielded a smaller volume change. On the other hand, those oocytes, which had slowest permeability to solute and the fastest permeability to water and a larger reflection coefficient, yielded a larger volume change (lower and upper dashed lines (±Lp, Ps, σ stdev), respectively, in Fig. 3b). The effects of each parameter (Lp, Ps, and σ) on the optimized profile were demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 4.†

Table 1.

Membrane coefficients of mouse oocytes exposed to 1.5 M propanediol (PROH)

| Lp (μm/atm/min) | Ps (μm s−1) | σ | T (°C) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/o CPA | 0.44 ± 0.03 | NA | NA | 20 | Leibo 1980 |

| 0.36 ± 0.07 | NA | NA | 21 | Bernard 1988 | |

| 0.48 ± 0.20 | NA | NA | 20 | Hunter 1992 | |

| W/CPA(PROH) | 2.20 ± 0.86 | 0.48 ± 0.20 | 0.71 ± 0.21 | 20 | Fuller 1992 |

| 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.99 ± 0.005 | 23 | Paynter 1997 | |

| 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 23 | Present study |

We also investigated the impact of various “slope times” (elapsed time to reach the maximum concentration, Cmax of CPA) for the concentration function. If the variable is introduced, ε = 1 – (Vmin/Vo), which is the normalized difference between the original volume (Vo) and the minimum volume (Vmin) the cell reaches in the process, the relationship can therefore be determined between ε and the “slope time”, where smaller values of ε are obviously desirable as it implies smaller volume change. This relationship is shown in Supplementary Figure 5a† and it is noted that to obtain smaller total changes in volume, the required “slope time” becomes larger. On the other hand, the time it takes for the cell to return to equilibrium increases as the “slope time” increases as shown in Supplementary Figure 5b.† The time to cell recovery appears to increase linearly with “slope time” whereas the total volume change of the cell decreases slightly exponentially with “slope time”. Therefore, the gain from increasing “slope time” diminishes exponentially as well since with each increase in “slope time” there is an equal demerit of time to equilibrium. It appears that after about a 10–15 min “slope time”, the beneficial decrease in volume change has tapered off so it is suggested to use this as end “slope time”.

Discussion

We developed a single oocyte analysis technique based on a microfluidic platform, with the final goal of simultaneously minimizing the volumetric changes and avoiding toxic injury during CPA loading for cryopreservation. Using a new microfluidic device, we can securely hold a single oocyte and expose them to external concentration gradients that are precisely controlled as a function of time. Using a biophysical model and measurements of oocyte response to concentration changes, we were able to design the optimized protocols that complete equilibration after CPA loading in less than 15 min, and with less than 10% oocyte volume changes throughout the process.

Single cell analysis using microfluidic devices has recently become a dynamic research area because it allows unique insights into the cellular response to external stimuli.8-10,23 Oocyte preservation is a good example of such potential applications, favored by the fact that oocytes are relatively easy to handle as single cells because of their large size. Since the first pregnancy using cryopreserved mature human oocytes,1 many researchers have studied to improve the cryopreservation protocols by mainly focusing on the optimization of media composition and studying a single function separately. With this microfluidic device, first, we compared the conventional step-wise CPA loading profile with linear CPA loading profiles and demonstrated that the linear CPA profile provided less volume changes and less total amounts of CPA exposure than the step-wise profile. Then, we proposed a complex profile for the “optimization” of the oocyte volume response by combining the benefits of the conventional step-wise profile (i.e. quick volume recovery to original volume) with the benefits of linear profiles (i.e. minimal volume change). Again, this is a first report to precisely control the concentration of cryoprotectants in a continuous manner.

The microfluidic device that we developed might offer valuable advantages in the analysis of single oocyte compared to conventional techniques for the measurement of oocyte volumetric changes such as the microperfusion18,22,24 and the diffusion chambers.25-27 For example, in the microperfusion techniques, the oocyte is handled in an assembled system (holding pipette-oocyte-outer pipette) including micromanipulation system to be moved from the drop of isotonic medium to the drop containing one of the CPA solutions. Thereafter, the oocyte is suddenly exposed to the anisotonic solution by quickly pulling the holding pipette18 and the volumetric changes respond to the sudden change of CPA concentration. In the diffusion chamber technique, cells are maintained in a microvolume sample region, held in position by an envelope of dialysis membrane. The osmotic response of cells is measured by applying the bulk flow of CPA solutions below the sample region, and might introduce confounding error into the permeability measurement. The microfluidic device combines the advantages of precisley controlled CPA concentration changes and gentle handling of oocytes.

The measured mouse oocytes membrane properties in our study, Lp (0.5 μm/atm/min), Ps (0.32 μm s−1) and σ (0.5), were comparable to the values determined by other methods, as shown in Table 1.22,26-29 From the measurements of the volumetric changes using conventional techniques, the membrane transport properties such as water permeability (hydraulic conductivity, Lp), solute (or cryoprotectant) permeability (Ps) and refection coefficient (σ) have been reported for mouse,17,22,28,30 and human oocytes26,31-33 in the presence and absence of different CPAs. Though there have been reports of an increase in Lp of mouse oocytes at room temperature in the presence of CPAs, the particularly high value for the Lp (2.20 μm min −1/atm) reported in the presence of PROH27 may be partially explained by inaccuracy in the modeling of CPA movement through the dialysis membrane of the diffusion chamber used for the study. The values calculated for σ were lower than those of previous reports (0.71~0.99).22,27 There have been reported in wide variations of the s with different cell types and cryoprotectants and thus further work will be required to fully investigate the influence of CPAs on membrane properties including σ under a variety of conditions.

In summary, the results presented here show that the microfluidic technology for single oocyte handling can be used efficiently to load CPAs. We also believe this technology will not be limited to only the oocyte research in the reproductive biology but will also would have a broad impact for single cell analysis in cell biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (EB002503, HD061297) and the Vincent Memorial Hospital Research Fund, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c1lc20377k

References

- 1.Chen C. Lancet. 1986;327:884–886. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90989-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanblerkom J, Davis PW. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1994;27:165–193. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070270209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahy GM, Macfarlane DR, Angell CA, Meryman HT. Cryobiology. 1984;21:407–426. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(84)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RJ, Shaw SK. Cryobiology. 1980;17:530–539. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(80)90067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazur P, Schneider U. Cell Biophys. 1986;8:259–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02788516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullen SF, Agca Y, Broermann DC, Jenkins CL, Johnson CA, Critser JK. Hum. Reprod. 2004;19:1148–1154. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shim J, Bersano-Begey TF, Zhu XY, Tkaczyk AH, Linderman JJ, Takayama S. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003;3:687–703. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heo YS, Cabrera LM, Bormann CL, Shah CT, Takayama S, Smith GD. Hum. Reprod. 2010;25:613–622. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beebe DJ, Mensing GA, Walker GM. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002;4:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.112601.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Carlo D, Lee LP. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7918–7925. doi: 10.1021/ac069490p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen HH, Purtteman JJP, Heimfeld S, Folch A, Gao D. Cryobiology. 2007;55:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song YS, Moon S, Hulli L, Hasan SK, Kayaalp E, Demirci U. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1874–1881. doi: 10.1039/b823062e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mata C, Longmire E, McKenna D, Glass K, Hubel A. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2010;8:457–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A E, Deutsch M, Namer Y, Shafran Y, Sobolev M, Zurgil N, Deutsch A, Howitz S, Greuner M, Thaele M, Zimmermann H, Meiser I, Ehrhart F. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irimia D, Toner M. Lab Chip. 2006;6:345–352. doi: 10.1039/b515983k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gook DA, Edgar DH. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2007;13:591–605. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackowski S, Leibo SP, Mazur P. J. Exp. Zool. 1980;212:329–341. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson JOM, Younis AI, Chan AWS, Gould KG, Eroglu A. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009;76:321–333. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JA, Wilson TA. J. Theor. Biol. 1967;17:304. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter JE, Bernard A, Fuller BJ, McGrath JJ, Shaw RW. Cryobiology. 1992;29:240–249. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(92)90022-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickman DL, Beebe DJ, Rodriguez-Zas SL, Wheeler MB. Comparative Med. 2002;52:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paynter SJ, Fuller BJ, Shaw RW. Cryobiology. 1997;34:122–130. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1996.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heo YS, Cabrera LM, Song JW, Futai N, Tung YC, Smith GD, Takayama S. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:1126–1134. doi: 10.1021/ac061990v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao DY, McGrath JJ, Tao J, Benson CT, Critser ES, Critser JK. Reproduction. 1994;102:385–392. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1020385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath JJ. J. Microsc. 1985;139:249–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1985.tb02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter J, Bernard A, Fuller B, McGrath J, Shaw RW. J. Cell. Physiol. 1992;150:175–179. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuller BJ, Hunter JE, Bernard AG, McGrath JJ, Curtis P, Jackson A. Cryo-Lett. 1992;13:287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leibo SP. J. Membr. Biol. 1980;53:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01868823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard A, McGrath JJ, Fuller BJ, Imoedemhe D, Shaw RW. Cryobiology. 1988;25:495–501. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(88)90295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlsson JOM, Eroglu A, Toth TL, Cravalho EG, Toner M. Hum. Reprod. 1996;11:1296–1305. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van den Abbeel E, Schneider U, Liu J, Agca Y, Critser JK, Van Steirteghem A. Hum. Reprod. 2007;22:1959–1972. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton H, Pegg DE, Barrass R, Gosden RG. Reproduction. 1999;117:27–33. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1170027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paynter SJ, O’Neil L, Fuller BJ, Shaw RW. Fertil. Steril. 2001;75:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01757-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.