Abstract

Background

The group of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancers (both luminal-A and -B) behaves differently from the ER-negative group. At least in early follow-up, ER expression influences positively patients' prognosis. This low aggressive biology flattens out the differences of clinical management. Thus we aimed to produce a prognostic index specific for ER-positive (ERPI) cancers that could be of aid for clinical decision.

Patients and methods

The test set comprised 495 consecutive ER-positive breast cancers. Tumor size, number of metastatic lymph nodes and androgen receptor expression were the only independent variables related to disease-specific survival. These variables were used to create the ERPI, which was applied to the entire test set and to selected subpopulations (grade 2 (G2)-tumors, luminal-A and -B breast cancers). A series of 581 ER-positive breast cancers, collected from another hospital, was used to validate ERPI.

Results

In the test population, 96.9% of patients classified as ERPI-good showed a good prognosis compared with 79.6% classified as ERPI-poor (P < 0.001). ERPI effectively discriminated outcome in luminal-A and luminal-B and in G2-tumors. In the validation series, the ERPI maintained its value.

Conclusion

ERPI is a practical tool in refining the prediction of outcome of patients with ER-positive breast cancer.

Keywords: AR expression, breast cancer, ER expression, lymph nodal status, prognostic index, tumor size

introduction

The therapy of estrogen receptor alpha (ER)-positive breast cancers, which represent more than 70% of breast tumors, is based on anti-hormonal compounds. ER-positive breast cancers, as a unified group, have in general a better prognosis than the ER-negative group [1]. Within this group, the prognosis is mainly related to pathological parameters. However, the prognostic value of grade of differentiation, vascular invasion, HER2 expression and Ki67 counting may be undermined by poor reproducibility [2–5]. In addition, in some cases, parameters of aggressiveness are associated with parameters of good prognosis (e.g. the presence of metastatic lymph nodes in an otherwise well-differentiated G1 tumor). More frequently, one or more of these risk factors are borderline (e.g. G2 tumor; equivocal HER2 expression; borderline HER2-gene status, borderline proliferation index), leading to uncertainty about the tumor behavior, which in turn impairs the ability to reach informed treatment decisions. So far, several prognostic indexes (PI), such as the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) [6–9] and the Adjuvant! Online [10, 11] have been developed and validated. The NPI was created in 1982 using a weighted score of three independent variables (tumor size, grade and number of involved lymph nodes). In the first edition of NPI, patients were classified into three categories of risk [6]; later on, patients were classified into six NPI risk categories [8]. Adjuvant! Online is a web-based tool designed to provide 10-year survival probability of patients with breast cancer as a continuous variable [10]. Strictly, Adjuvant! does consider ER status (positive/negative) as one of its basic parameters.

We aimed to develop a PI purely within the ER-positive breast cancers, hypothesizing that classical and new (androgen receptor: AR) prognostic parameters could have a different weight in patient outcome when compared with that seen in HER2-positive and triple negative breast cancers. We introduced AR because it is expressed in ∼70% of ER-positive breast cancers and positively affects the outcome of patients as a possible tumor suppressor [12, 13]. We constructed a weighted risk score by multivariate analysis of parameters correlated with disease-specific survival (DSS) and, from this, we created a PI able to subdivide patients in two risk categories of good and poor prognoses. Finally, we validated the results in an independent series of ER-positive breast cancers.

patients and methods

study design and population

A series of 543 patients diagnosed with ER-positive breast cancer between 1994 and 2005 was collected at the Breast Unit of the San Giovanni Battista-Molinette Hospital of Turin, Italy, of these, 385 patients were part of a previous recently published study [12].

Sections of the 158 newly collected tumors were reviewed. Multicore tissue microarrays (TMAs), prepared as previously described [14], were retested by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for ER-status; 48 of 543 tumors were ER-negative. These cases, confirmed as negative by IHC carried out on whole tissue sections, were excluded from the study. The medical charts of the remaining 495 patients (test series) were reviewed and updated.

A cohort of 581 ER-positive breast cancers centrally reviewed and collected in the same period from OIRM Sant'Anna Hospital of Turin, Italy, was used as ‘validation series’ (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

IHC was carried out as previously reported [12], to assess AR (mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) clone AR441, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), ER (rabbit mAb, clone SP1, Ventana-Diapath, Tucson, AZ) and progesterone receptor (PR) (rabbit mAb, clone 1E2, Ventana-Diapath). The proliferation index was assessed using the Ki67 mouse mAb (clone MIB-1, Dako). HER2 status was evaluated using the Herceptest™ (Kit Dako). Equivocal (score 2+) cases were investigated by FISH assay (Vysis, Inc., Downers Grove, IL).

The cut-off value for ER- and PR-positivity was set at 1%, and the same cut-off was also adopted for AR-positivity [12]. The percentage of Ki67-positive cells was counted at the section periphery.

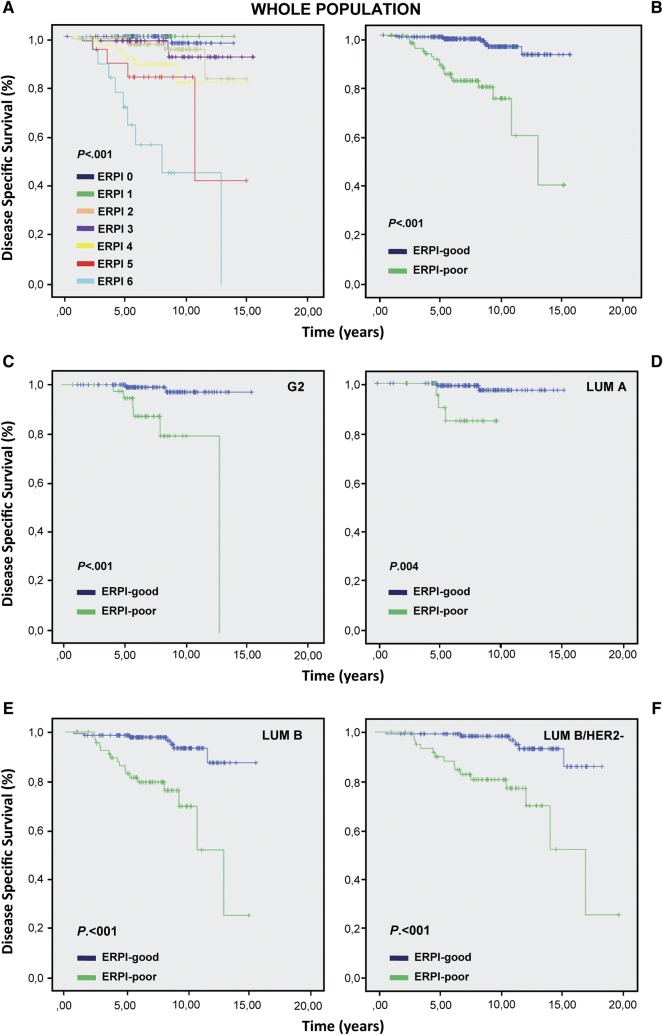

statistical analysis and construction of the prognostic index

The follow-up time was calculated using the median observation time among all patients. The follow-up was censored at the time of death or of the last clinical investigation of the patient. DSS was calculated from the date of definitive surgery to the date of death from the disease. Patients dying from other causes were censored at the time of death. In the test series of 495 patients, DSS was studied using the Kaplan–Meier method and the Log-rank test (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The clinical and pathological parameters used for univariate analysis are reported in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. The best cut-off value of tumor size was established at 15 mm [15–20]. For the multivariable analysis, prognostic factors were selected based on their statistical significance at univariate analysis. A Cox proportional hazard model was used and the effect of single variables was expressed as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Three covariates maintained their statistical significance: tumor size, number of metastatic lymph nodes and AR status. A score was attributed to each variable according to its HR. Its weight value was approximately twofold for tumor size and AR than for number of metastatic lymph nodes (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Thus, a score value of 2 was given to tumors >15 mm and to tumors with AR-negative. Instead, tumors ≤15 mm and tumors with AR-positive were scored as 0. Three score values were used for lymph nodes (0: lymph nodes free of metastases; 1: from 1 to 3 metastatic lymph-nodes and 2: >3 metastatic lymph nodes). A PI for ER-positive cancers (ERPI) was created using the following formula: (tumor size score value) + (number of metastatic lymph nodes score value) + (AR score value) (Table 1). The two extremes of the ERPI were 0 and 6. Kaplan–Meier analysis was then carried out for each ERPI value (Figure 1A). Following the performance curves, we set the cut-off of the ERPI at 3: value ≤3 good prognosis (ERPI-good), value >3 poor prognosis (ERPI-poor) (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Algorithm to calculate the ERPI

| Status | Points | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes | 0 | 0 |

| 1–3 | 1 | |

| >3 | 2 | |

| Tumor size | <15 mm | 0 |

| >15 mm | 2 | |

| Androgen receptor | 0% | 2 |

| ≥1% | 0 |

Algorithm: (tumor size score value) + (number of metastatic lymph nodes score value) + (AR score value).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis carried out on test cohort for each ERPI value (A). Kaplan–Meier analysis carried out for ERPI value using a cut-off of 3: a value ≤3 was considered as ERPI-good and a value >3 as ERPI-poor (B). ERPI on G2 (C), luminal-A (D) luminal-B and luminal-B HER2-negative cases (E, F).

A univariate analysis was carried out to study the effect of the ERPI in the entire test population and in selected subpopulations, namely G2 tumors, luminal-A and luminal-B cancers. The distinction between luminal-A and luminal-B was defined according to the proliferation rate by Ki67 (cut-off of 14%) and to HER2-status [21].

To validate the results, we applied the ERPI to the case series from Sant'Anna Hospital.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate the ERPI performance in predicting DSS by comparing its value with other single prognostic factors.

SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) software, the R environment (www.r-project.org), SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and S-PLUS version 6.1 (Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA) were used for statistical analyses.

results

descriptive analyses of the test and the validation cohorts

The median follow-up time was 7.8 years. The comparison of the two cohorts of patients (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) revealed some differences in the type of treatment (surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy), probably because of the differences in the size of tumors and presence of vascular invasion.

ERPI results on the test cohort

At univariate analysis age, treatment type, ER expression levels and HER2-status did not show any significant correlation with DSS. At multivariate analysis only tumor size, number of metastatic lymph nodes and AR status resulted significant for prognosis (supplementary Tables S2–S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The ERPI, built on the basis of the HR, was applicable to 385 patients, 92.5% of whom were censored at follow-up.

The rate of patients censored for ERPI-good was 96.9% and 79.6% for ERPI-poor, with a highly significant difference (χ2 = 40.037, P < 0.001) (Figure 1B, supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). ERPI maintained its statistical significance both in patients that received hormonal therapy and in those treated with hormonal plus chemotherapy (χ2 = 13.543, P < 0.001 and χ2 = 19.375, P < 0.001 respectively).

ERPI in G2 breast cancer patients

Among 495 breast cancers, 197 (40%) were classified as G2. ERPI, assessable in 160 cases, discriminated two populations with different outcomes (χ2 = 14.179, P < 0.001) (Figure 1C).

As for the entire population, ERPI had a significant correlation with outcome both in the subset of patients treated with endocrine therapy or with the addition of chemotherapy (χ2 = 5.169, P = 0.023 and χ2 = 7.422, P = 0.006).

ERPI in luminal-a and luminal-b breast cancer patients

The significant correlation with DSS of ERPI-good and -poor was maintained in both luminal-A and luminal-B tumors (χ2 = 8.334, P = 0.004 and χ2 = 23.974, P < 0.001) (Figure 1D–E). In luminal-A cancers receiving only endocrine therapy, ERPI discriminated patients with poor outcome (χ2 = 19.273, P < 0.001), while all patients receiving chemotherapy resulted censored. In luminal-B cases, ERPI discriminated patients with poor outcome only in the chemotherapy-treated subgroup (χ2 = 15.688, P < 0.001). Furthermore, ERPI was effective only in the luminal-B HER2-negative/Ki67 >14% cancers (χ2 = 20.721, P < 0.001) (Figure 1F) and not in those HER2-positive (data not shown).

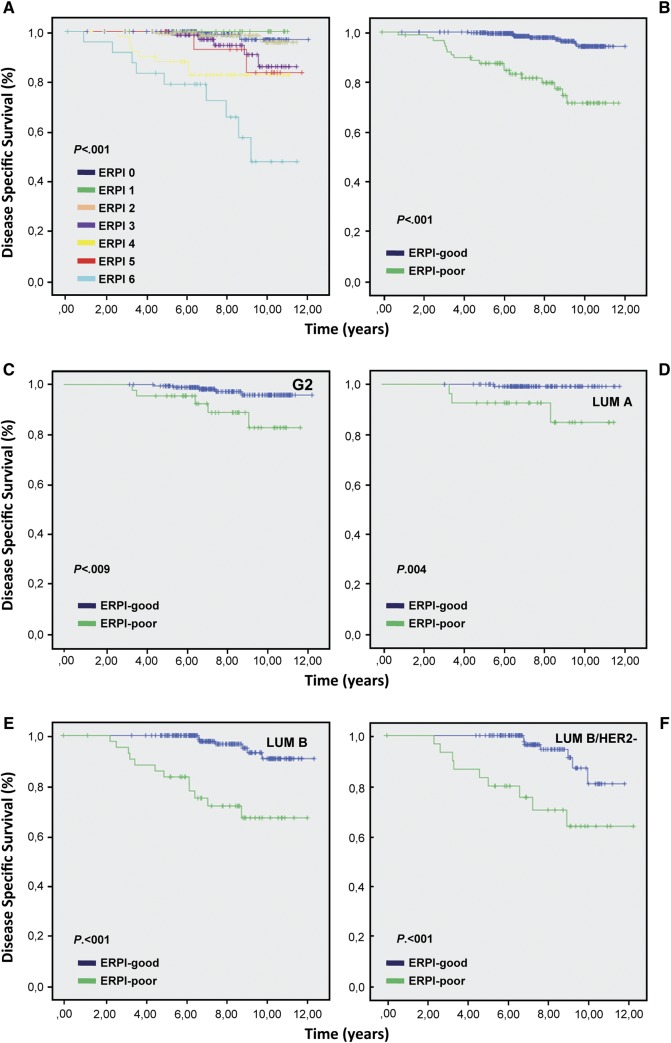

ERPI confirmed its prognostic value in the validation series (Figure 2). The DDS for luminal-A cancers that received endocrine therapy alone was 100% (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis carried out on validation cohort for each ERPI value (A). Kaplan–Meier analysis carried out for ERPI value using a cut-off of 3: a value ≤3 was considered as ERPI-good and a value >3 ERPI-poor (B). ERPI on G2 (C), luminal-A (D) luminal-B and luminal-B HER2 negative cases (E, F).

ERPI was more powerful in predicting survival then each individual parameter in both populations (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

In contrast with other PIs that have been created for breast cancer in general [6, 10, 11], in the present work, we produced a PI specific for luminal cancers. In this cancer subset, ERPI discriminates between patients with good and poor prognoses as a binary system, whereas other PIs, such as NPI, define intermediate risk categories, as well [6, 8].

The ERPI can be constructed from routine diagnosis being largely based on tumor size and number of lymph node involvement. We added the expression of AR, because our group [12] and other authors [13, 22–24] demonstrated the prognostic relevance of its expression in breast cancers. To our knowledge, ERPI is the first tool of risk evaluation, which encompasses AR-expression. The IHC reproducibility of AR is easy to achieve, because we classified cases as negative or positive using a cut-off value of 1%, as previously suggested [12].

Regarding tumor size and lymph-nodal status, they are considered independent prognostic variables [25], both of them have a good reproducibility and, among various ‘biological markers’ of prognosis, they may be considered ‘time-dependent markers’. This means that, in the majority of cancers and in particular in low aggressive ER-positive tumors, these two factors are correlated with the lapse of time between tumor initiation and its diagnosis. Warwick et al. [26] in a study evaluating the time-dependent effects on breast cancer survival, suggested that tumor grade, lymph-nodal status, and tumor size at the time of diagnosis have a lasting influence on subsequent survival, albeit attenuated in later years.

In the present study, we defined a tumor size of 15 mm as the cut-off value to be used in multivariate analysis, based on our experience [17] and on literature data [15, 16, 18–20]. For example an analysis of a large series of breast cancers showed that patient prognosis was very good for tumors up to 14 mm but was significantly worse for larger tumors [19]. Another study on early breast cancer patients demonstrated, by a complex mathematical model, that the relative increase in mortality was considerably higher for each millimeter increment in the size of smaller tumors than in larger tumors and that the transition occurred at ∼15 mm [20]. In the same series, the node-positive status did not abolish the effect of tumor size.

As reported in a detailed review on tumor-related prognostic factors for breast cancer, the lymph-nodal status is the single most influential predictor of post-treatment recurrence and death [27]. However, rather than the node involvement, the absolute number of metastatic nodes is related to the prognostic continuum of recurrence and survival [28, 29]. Different studies showed that patients without metastasis and those with one to three metastatic lymph nodes have similar outcomes [16, 30, 31]. On the other hands, extensive lymph-nodal involvement (>3 involved nodes) is considered an indication to chemotherapy regardless of the biological breast cancer subset [21]. Taking together all these data reinforce our results, which selected the tumor size, the number of lymph nodes affected by metastases and the AR status parameters as independent variables. ERPI was helpful for defining prognosis in G2 tumors, which are both poorly reproducible as an entity and poorly defined in their outcome. The ERPI identified patients with different prognoses even in luminal-A tumors, which are considered to have an indolent outcome, so that after being surgically removed, they could skip further treatment or be treated with endocrine therapy only [21]. Nevertheless, in our study, 19% (test series) and 49% (validation series) of the patients with luminal-A cancers received chemotherapy in addition to endocrine therapy. These differences demonstrate the difficulty in adopting reproducible criteria for the therapy decision.

ERPI was also significant in the group of luminal-B cancers with high Ki67 levels that received chemotherapy. High and low Ki67-labeling indexes provide information regarding the response to chemotherapy and the prognosis in patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer [32, 33]. However, mid-range Ki67 levels such as those proposed for classifying either luminal-A or luminal-B cancers suffer from poor reproducibility [2]. The ERPI lost its significance in ER-positive/HER2-positive breast cancers.

The ERPI may indeed offer several advantages, including the easy application to formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue and the use of standardized parameters, commonly adopted in the diagnosis of breast cancer. The ERPI may thus represent a valuable tool in refining the prognosis in patients with ER-positive breast cancer.

funding

This work was supported by Compagnia San Paolo di Torino, AIRC 2010–2012, MIUR-PRIN 2008.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank Alan Coates for its valuable assistance in statistical data management.

references

- 1.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varga Z, Diebold J, Dommann-Scherrer C, et al. How reliable is Ki-67 immunohistochemistry in grade 2 breast carcinomas? A QA Study of the Swiss Working Group of Breast- and Gynecopathologists. PLoSOne. 2012;7:e37379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longacre TA, Ennis M, Quenneville LA, et al. Interobserver agreement and reproducibility in classification of invasive breast carcinoma: an NCI breast cancer family registry study. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:195–207. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalton LW, Page DL, Dupont WD. Histologic grading of breast carcinoma. A reproducibility study. Cancer. 1994;73:2765–2770. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2765::aid-cncr2820731119>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuda H, Kurosumi M, Umemura S, et al. HER2 testing on core needle biopsy specimens from primary breast cancers: interobserver reproducibility and concordance with surgically resected specimens. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:534. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haybittle JL, Blamey RW, Elston CW, et al. A prognostic index in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1982;45:361–366. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galea MH, Blamey RW, Elston CE, et al. The Nottingham Prognostic Index in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;22:207–219. doi: 10.1007/BF01840834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blamey RW, Ellis IO, Pinder SE, et al. Survival of invasive breast cancer according to the Nottingham Prognostic Index in cases diagnosed in 1990-1999. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1548–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AH, Ellis IO. The Nottingham prognostic index for invasive carcinoma of the breast. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14:113–115. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravdin PM, Siminoff LA, Davis GJ, et al. Computer program to assist in making decisions about adjuvant therapy for women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:980–991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajage D, de Rycke Y, Bollet M, et al. External validation of Adjuvant! Online breast cancer prognosis tool. Prioritising recommendations for improvement. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellano I, Allia E, Accortanzo V, et al. Androgen receptor expression is a significant prognostic factor in estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:607–617. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickey TE, Robinson JL, Carroll JS, et al. Minireview: the androgen receptor in breast tissues: growth inhibitor, tumor suppressor, oncogene? Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1252–1267. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapino A, Marchiò C, Senetta R, et al. Routine assessment of prognostic factors in breast cancer using a multicore tissue microarray procedure. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher B, Slack NH, Bross ID. Cancer of the breast: size of neoplasm and prognosis. Cancer. 1969;24:1071–1080. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196911)24:5<1071::aid-cncr2820240533>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989;63:181–187. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<181::aid-cncr2820630129>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arisio R, Sapino A, Cassoni P, et al. What modifies the relation between tumour size and lymph node metastases in T1 breast carcinomas? J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:846–850. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.11.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Reilly SM, Camplejohn RS, Barnes DM, et al. Node-negative breast cancer: prognostic subgroups defined by tumor size and flow cytometry. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:2040–2046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy SW, Tabar L, Vitak B, et al. Tumor size and breast cancer detection: what might be the effect of a less sensitive screening tool than mammography? Breast J. 2006;12(Suppl 1):S91–S95. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verschraegen C, Vinh-Hung V, Cserni G, et al. Modeling the effect of tumor size in early breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241:309–318. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150245.45558.a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, et al. Strategies for subtypes—dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters AA, Buchanan G, Ricciardelli C, et al. Androgen receptor inhibits estrogen receptor-alpha activity and is prognostic in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6131–6140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S, Koo JS, Kim MS, et al. Androgen receptor expression is significantly associated with better outcomes in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu R, Dawood S, Holmes MD, et al. Androgen receptor expression and breast cancer survival in postmenopausal women. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1867–1874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cianfrocca M, Goldstein LJ. Prognostic and predictive factors in early-stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:606–616. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-6-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warwick J, Tabàr L, Vitak B, et al. Time-dependent effects on survival in breast carcinoma: results of 20 years of follow-up from the Swedish Two-County Study. Cancer. 2004;1007:1331–1336. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donegan WL. Tumor-related prognostic factors for breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47:28–51. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.47.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chagpar AB, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Lymph node ratio should be considered for incorporation into staging for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3143–3148. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danko ME, Bennett KM, Zhai J, et al. Improved staging in node-positive breast cancer patients using lymph node ratio: results in 1,788 patients with long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher ER, Anderson S, Redmond C, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project Protocol B-06: 10-year pathologic and clinical prognostic discriminants. Cancer. 1993;71:2507–2514. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2507::aid-cncr2820710813>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heimann R, Hellman SJ. Clinical progression of breast cancer malignant behavior: what to expect and when to expect it. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:591–599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yerushalmi R, Woods R, Ravdin PM, et al. Ki67 in breast cancer: prognostic and predictive potential. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:174–183. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fasching PA, Heusinger K, Haeberle L, et al. Ki67, chemotherapy response, and prognosis in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:486. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.