Abstract

Background

Perforation is a serious life-threatening complication of lymphomas involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Although some perforations occur as the initial presentation of GI lymphoma, others occur after initiation of chemotherapy. To define the location and timing of perforation, a single-center study was carried out of all patients with GI lymphoma.

Patients and methods

Between 1975 and 2012, 1062 patients were identified with biopsy-proven GI involvement with lymphoma. A retrospective chart review was undertaken to identify patients with gut perforation and to determine their clinicopathologic features.

Results

Nine percent (92 of 1062) of patients developed a perforation, of which 55% (51 of 92) occurred after chemotherapy. The median day of perforation after initiation of chemotherapy was 46 days (mean, 83 days; range, 2–298) and 44% of perforations occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most common lymphoma associated with perforation (59%, 55 of 92). Compared with indolent B-cell lymphomas, the risk of perforation was higher with aggressive B-cell lymphomas (hazard ratio, HR = 6.31, P < 0.0001) or T-cell/other types (HR = 12.40, P < 0.0001). The small intestine was the most common site of perforation (59%).

Conclusion

Perforation remains a significant complication of GI lymphomas and is more frequently associated with aggressive than indolent lymphomas. Supported in part by University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic SPORE CA97274 and the Predolin Foundation.

Keywords: lymphoma, perforation

introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) lymphomas have been reported to constitute up to 10 to 15% of all newly diagnosed non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) [1–3]. The GI tract is the most common site for extra-nodal involvement in NHL [4]. Perforation and peritonitis are known complications of GI lymphomas that can occur either at diagnosis or during the course of treatment. Although unusual, the occurrence of perforations is potentially life threatening and leads to considerable morbidity from sepsis, multi-organ failure, prolonged hospitalization, complications of wound healing, delays in the initiation of chemotherapy and mortality. Several studies have reported an inferior outcome of GI lymphomas when complicated by perforation [2, 4, 5].

There is concern regarding the potential for gut perforation at the time of institution of chemotherapy for GI NHL. Some patients are hospitalized for the first cycle of chemotherapy to be observed for signs and symptoms of perforations. Early identification of patients with impending perforation may permit early surgical intervention. In order to improve management strategies in patients with GI lymphoma, a retrospective review of a single institution experience was undertaken to address the location and timing of perforation in the disease course of these patients.

patients and methods

We utilized the Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Data Base (January 1975–May 2012) and the University of Iowa/Mayo SPORE Database (2002-present) in conjunction with the Mayo Clinic Life Sciences System to identify all patients with biopsy-proven involvement of the GI tract with lymphoma [6, 7]. All pathology specimens were centrally reviewed. Patients who had radiologic evidence of gut involvement without tissue pathology from the gut were excluded. The clinical and surgical records of these patients were reviewed to identify those patients who sustained an intestinal perforation. Perforation was defined as the presence of free air under the diaphragm on abdominal imaging and/or demonstration of a perforated bowel at laparotomy with or without localized abscess or peritonitis. Perforation could have occurred at any point in time from initial diagnosis of lymphoma to date of last follow-up or date of death. For patients who had a complication of perforation(s), data were collected including the date of diagnosis of lymphoma, age at diagnosis, histopathology, date of perforation, site of perforation, surgery carried out, chemotherapy administered, date of last chemotherapy before perforation, date and cause of death, and date of last follow-up. Descriptive statistics are reported as number (percentage) or median (range) as appropriate. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess the risk of perforation with lymphoma subtypes. The results are reported as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The α level was set at 0.05 for statistical significance. This study was approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in accordance with US federal regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

results

Between January 1975 and May 2012, 1062 patients were identified with biopsy-proven involvement of the GI tract with lymphoma. The most common types of GI lymphomas diagnosed at biopsy were diffuse large B-cell NHL (DLBCL) (39%) and extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) (21%) (Table 1). Nine percent (92 of 1062) of these patients had an intestinal perforation. Eight of the 92 (8.7%) patients had two episodes of perforation, thereby increasing the total number of perforation events to 100. The GI tract was the primary site of lymphoma involvement in 72 of the 92 patients at presentation; in the other 20 patients, the GI tract was secondarily involved from systemic lymphoma.

Table 1.

Histopathologic distribution of 1062 patients with biopsy-proven involvement of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with lymphoma and 92 patients who sustained a perforation

| Lymphoma disease type | Patients with biopsy-proven GI involvement with lymphoma (N), % (n = 1062) | Number of patients within each subtype who developed a perforation, % (n = 92) | Hazard ratio (HR), [95% confidence interval (CI)], P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell lymphoma, Indolent | |||

| MALT lymphoma | 221 (21%) | 4 (1.8%) | |

| Follicular, grade 1 | 106 (10%) | 3 (2.8%) | |

| Follicular, grade 2 | 20 (2%) | 0 | |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | 32 (3%) | 0 | |

| Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | |

| Total | 380 (35.8%) | 7 (1.8%) | 1.00 (reference) |

| B-cell lymphoma, Aggressive | |||

| Diffuse large B-cell | 415 (39%) | 55 (13.2%) | |

| High grade B-cell, unclassifiable | 24 (2%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| Burkitt's lymphoma | 15 (1%) | 1 (6.6%) | |

| Follicular, grade 3 | 8 (1%) | 0 | |

| Mantle cell lymphomaa | 95 (9%) | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Total | 557 (52.4%) | 61 (10.9%) | 6.31 (3.09–15.19), P < 0.0001 |

| All others | |||

| Peripheral T-cell | 23 (2%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| Anaplastic | 6 (0.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Angioimmunoblastic | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | |

| Enteropathy-associated | 16 (1.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| NK (natural killer)/T-cell | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 6 (0.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Lymphoma, unclassified | 31 (3%) | 2 (6.4%) | |

| Post-transplant lymphoproliferative | 40 (4%) | 8 (20%) | |

| Total | 125 (11.8%) | 24 (19.2%) | 12.40 (5.65–31.11), P < 0.0001 |

aMantle cell lymphoma can behave clinically as either indolent or aggressive lymphoma but are typically grouped with the aggressive lymphomas.

clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 92 patients with GI perforation are summarized in Table 2. The median age at the time of initial diagnosis of lymphoma in this cohort was 64 years (range, 24–89). The median age at perforation was 66 years (range, 24–90); 65% (60 of 92) of the patients were male. Out of 100 perforation events, 51 occurred as the initial presentation of intestinal lymphoma and 49 occurred during treatment with chemotherapy (Table 3). Of those 49 events, 25 were preceded by their first (initial) chemotherapy regimen; 24 occurred in the setting of relapsed/refractory lymphoma after having received multiple chemotherapy regimens before perforation. In the 25 perforations that occurred after the first chemotherapy regimen, the median day of perforation was 46 days (mean, 83 days; range, 2–298 days) following initiation of chemotherapy. Thirty-two percent (8 of 25) perforations occurred within weeks 1 and 2, 12% (3 of 25) in weeks 3 and 4 and 56% (14 of 25) beyond week 4 of initiating chemotherapy. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) was the most frequent regimen (64%, 16 of 25), while 56% (14 of 25) patients received rituximab either as a single agent (5 of 14) or in combination with CHOP (9 of 14). Among the 24 of the 49 events that occurred in the setting of relapsed/refractory lymphoma, the median time to perforation was 35 days (mean, 67 days; range, 4–493 days) from the initiation of the most recent chemotherapy regimen before perforation. Of note, no perforation event occurred within the first 2 days of chemotherapy administration in either cohort.

Table 2.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of 92 patients who developed a perforation with known gastrointestinal (GI) involvement with lymphoma

| Clinical characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 92 |

| Age at perforation (years); median (range) | 66 (24–90) |

| Sex | |

| Males | 60 (65%) |

| Site of perforation,a % | |

| Stomach | 16% |

| Small bowel | 59% |

| Large bowel | 22% |

| Spleen | 1% |

| Histology | |

| Diffuse, large B- cell | 55 (59.1%) |

| Post-transplant lymphoproliferative (PTLD) | 8 (8.7%) |

| Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 7 (7.5%) |

| MALT lymphoma | 4 (4.3%) |

| High-grade B-cell, unclassifiable | 3 (3.2%) |

| Follicular, grade 1 | 3 (3.2%) |

| Anaplastic T-cell | 2 (2.1%) |

| Mantle cell | 2 (2.1%) |

| Hodgkin | 2 (2.1%) |

| Lymphoma, unclassified | 2 (2.1%) |

| Enteropathy-associated T-cell | 2 (2.1%) |

| NK (natural killer)/T-cell | 1 (1.1%) |

| Burkitt's | 1 (1.1%) |

| Chemotherapy before perforation (%) | 51 (55%) |

| Total deaths (%) | 55 (60%) |

| Due to perforation | 28 |

| Due to progressive/relapsed lymphoma | 12 |

| Due to sepsis | 2 |

| Others/cause unknown | 13 |

aTotal number of perforation events is 100.

Table 3.

Timing of the 100 gastrointestinal (GI) perforation events

| Timing | n (%) | Day of perforation Median (mean, range) | % Perforations within 4 Weeks | Death due to perforation (n = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At presentation | 51 (51) | NA | NA | 14 |

| After chemotherapy | 49 (49) | 35 (75, 2–493) | 43% | 14 |

| Initial regimen | 25 (51) | 46 (83, 2–298) | 44% | 3 |

| Relapsed—multiple regimens | 24 (49) | 35 (67, 4–493) | 42% | 11 |

NA, not applicable since these patients presented with perforations.

histopathology

The histopathologic types of lymphoma of the 92 patients who had a perforation are listed in Table 2. Similar to the prevalence of GI tract involvement in all 1062 cases, DLBCL was the most common lymphoma that perforated. Of the 55 DLBCL cases with a GI perforation, 2 were double hit lymphomas with bcl-2 and c-myc translocations, 7 had transformed from underlying follicular lymphoma, 2 transformed from chronic lymphocytic leukemia and 1 transformed from Hodgkin lymphoma. Compared with B-cell indolent lymphomas, the risk of perforation was significantly higher with B-cell aggressive lymphomas (HR = 6.31, 95% CI 3.09–15.19, P < 0.0001) and the T-cell/post-transplant lymphoproliferative (PTLD)/other group (HR = 12.40, 95% CI 5.65–31.11, P < 0.0001).

site of perforation

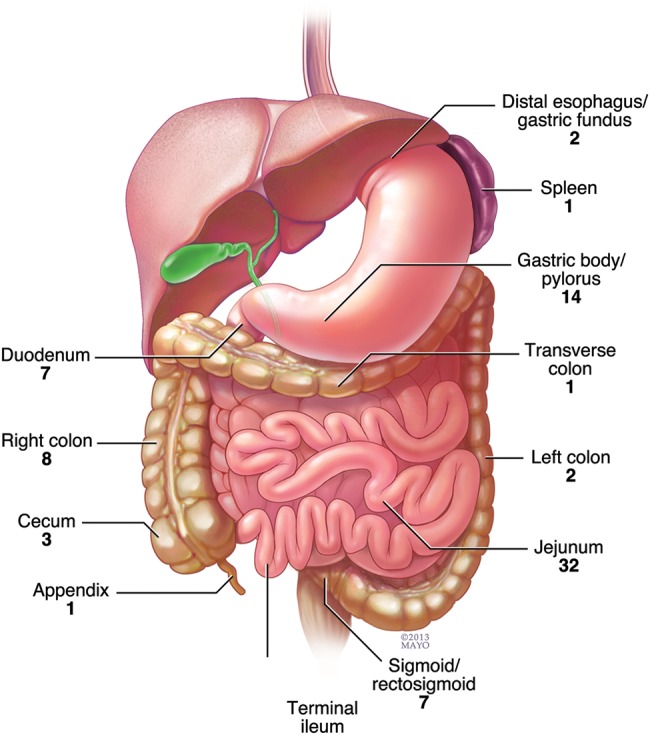

The most common site of perforation was the small bowel (59%), followed by large bowel (22%) and gastric (16%). The spleen and appendix were each involved in one perforation. The distribution of perforation sites is illustrated in Figure 1. Pathology of the specimen removed at the time of surgery for perforation was available for review in 94 of the 100 events. In 73% (69 of 94), there was a tumor at the perforation site. In the remaining 27% (25 of 94), there was no evidence of viable lymphoma. Etiologies of perforation in this group of patients included acute inflammation and/or tumor necrosis consistent with chemotherapy effect (14), radiation enteritis (2), diverticulitis after chemotherapy (2), neutropenic colitis (1), procedure related (3), severe infectious colitis from Clostridium difficile (1) and cytomegalovirus enteritis (1) and colonic pseudoobstruction (Ogilvie syndrome) (1).

Figure 1.

Sites of perforation in 100 perforation events with GI lymphoma (the site was unknown in 2 patients who transitioned to hospice after demonstration of free air in the abdomen on computed tomography imaging).

morbidity and mortality

At the time of last follow-up, 60% (55 of 92) patients with perforation had died. Of these, 30% (28 of 92) died directly due to the perforation or subsequent complications. Among patients who perforated after receiving a single chemotherapy regimen, the median survival was 0.8 years (mean, 3.9 years; range, 0–15.1 years) from the time of perforation. In this group, there were 12 deaths, of which 3 were secondary to perforation. Among patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma who sustained a perforation after multiple chemotherapy regimens, the median survival was shorter at 0.2 years (mean, 2.4 years; range, 0–24.4 years). In this population, there were 18 deaths, of which 11 were secondary to perforation.

discussion

Despite modern tumor imaging methods and effective chemoimmunotherapy for lymphoma, perforation of GI tract lymphomas is an important clinical complication. In this large single-institution study, the rate of perforation in patients with biopsy-proven GI tract lymphomas was determined to be 9% with nearly half the perforation events representing the initial presentation of GI lymphoma. Thus, these perforations are unlikely to have been averted with prior interventions. No events occurred within the first 2 days of chemotherapy dispelling a common notion that these perforations occur very early after chemotherapy. In our series, about half of the perforations post chemotherapy occurred in the first month/cycle, with the other half occurring >4 weeks after starting chemotherapy. These included perforations from the lymphoma itself as well as from treatment-related complications such as neutropenic colitis, infectious colitis, radiation enteritis and colonic pseudoobstruction. Other small series of perforation events in GI lymphoma also report a range of time to perforation from 4 days to >5 weeks from the initiation of chemotherapy [8–10]. We hypothesize that tumor necrosis and inflammation after administration of chemotherapy contribute to these later perforation events. Our finding that nearly 25% of pathology samples at the time of surgery demonstrated no viable residual tumor supports this. Patients and primary care physicians should be counseled on the high risk of perforation in the first month and beyond the time of initial therapy. GI lymphoma patients with new abdominal pain should receive a prompt physical examination and evaluation for free air in the abdomen with appropriate imaging. A delay in diagnosis and treatment results in increased morbidity and mortality. In our cohort, nearly 50% of all deaths were attributable to the perforation or its subsequent complications.

The role of elective surgery in the management of intestinal lymphoma remains debatable. Whether resection of localized disease before initiation of chemotherapy prevents delayed complications of hemorrhage and perforation is not clear. Among 32 patients with intestinal lymphoma, Zinzani et al. reported better outcomes with surgical resection followed by chemotherapy in patients with localized disease [11]. Ibrahim et al. also noted improved event-free survival with resection followed by chemotherapy in 66 patients with intestinal DLBCL, although the effect on overall survival was not significant [12]. The decision to resect a GI lymphoma before chemotherapy depends on several factors including the location and extent of the disease, the pace of the disease, presence of hemorrhage and whether resection would result in long-term complications such as short-gut syndrome. While gastric lymphomas are almost never primarily operated upon [13], resection before chemotherapy is a reasonable intervention for discrete and localized disease in the cecum or small bowel. For aggressive or multifocal disease, resection before chemotherapy may not be technically feasible or advisable due to the extent and location of the disease as well as the resulting delay in chemotherapy necessitated to allow sufficient tissue healing.

A higher percentage of perforations occurred in males compared with females in our study. This may be reflective of epidemiology of intestinal lymphomas, where males have a higher reported incidence than females [1, 14, 15]. Although 60% (55 of 92) of perforations involved DLBCL, perforation only occurred in 13% of all 415 DLBCL cases involving the gut in our series. The risk of perforation was lowest in B-cell indolent lymphomas compared with B-cell aggressive lymphomas as well as other lymphomas including T-cell, Hodgkin, PTLD and lymphoma unclassified. The German Study Group on intestinal NHL similarly reported a higher incidence of perforation in intestinal T-cell compared with B-cell lymphomas [16]. Of interest, in our study, 20% (8 of 40) of cases of PTLD involving the bowel perforated. This is a novel observation and occurred in a patient population with a higher association of extranodal disease, which was characteristically bulky in the area of the small bowel.

A higher percentage of perforations occurred in the small bowel (59%), compared with the stomach (16%) or large bowel (22%). Ara et al. reported similar findings in their case series of eight patients with bowel perforations from lymphoma, where six of the eight perforations occurred in the small bowel and only two involved the large bowel [17]. Two prospective studies of patients with gastric lymphomas treated with chemotherapy reported no perforation events over a follow-up of >5 years [18, 19]. A relatively low proportion of perforations involving the stomach may be explained by the fact that the gastric wall thickness is greater than that of the small or large intestine. Given the retrospective nature of our study, it is difficult to determine the true incidence of organ-specific perforations.

In conclusion, bowel perforation in GI lymphomas contributes significantly to the morbidity and mortality. An appreciation of the natural history of this clinical presentation aids in the management of patients with GI tract lymphomas.

funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma SPORE [P50 CA97274] and the Henry J. Predolin Foundation.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1.d'Amore F, Brincker H, Gronbaek K, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1673–1684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amer MH, el-Akkad S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:846–858. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otter R, Bieger R, Kluin PM, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:745–750. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.351. doi:10.1038/bjc.1989.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gou HF, Zang J, Jiang M, et al. Clinical prognostic analysis of 116 patients with primary intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9783-x. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9783-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kako S, Oshima K, Sato M, et al. Clinical outcome in patients with small-intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1618–1624. doi: 10.1080/10428190903147629. doi:10.1080/10428190903147629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drake MT, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency and prognosis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4191–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6674. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swerdlow SH International Agency for Research on Cancer., World Health Organization. WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada M, Onda M, Tokunaga A, et al. Spontaneous gastrointestinal perforation in patients with lymphoma receiving chemotherapy and steroids. Report of three cases. Nihon Ika Daigaku Zasshi. 1999;66:37–40. doi: 10.1272/jnms.66.37. doi:10.1272/jnms.66.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhai L, Zhao Y, Lin L, et al. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Involving the Ileocecal Region: A Single-institution Analysis of 46 Cases in a Chinese Population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:509–514. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318237126c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maisey N, Norman A, Prior Y, Cunningham D. Chemotherapy for primary gastric lymphoma: does in-patient observation prevent complications? Clin Oncol. 2004;16:48–52. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(03)00250-4. doi:10.1016/S0936-6555(03)00250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Pagliani G, et al. Primary intestinal lymphoma: clinical and therapeutic features of 32 patients. Haematologica. 1997;82:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim EM, Ezzat AA, El-Weshi AN, et al. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: clinical features, management and prognosis of 66 patients. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:53–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1008389001990. doi:10.1023/A:1008389001990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BM, et al. EGILS consensus report. Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224949. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.224949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domizio P, Owen RA, Shepherd NA, et al. Primary lymphoma of the small intestine. A clinicopathological study of 119 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:429–442. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199305000-00001. doi:10.1097/00000478-199305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papaxoinis G, Papageorgiou S, Rontogianni D, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 128 cases in Greece. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study (HeCOG) Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2140–2146. doi: 10.1080/10428190600709226. doi:10.1080/10428190600709226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, et al. Intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2740–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.026. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ara C, Coban S, Kayaalp C, et al. Spontaneous intestinal perforation due to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: evaluation of eight cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1752–1756. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9279-x. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aviles A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, et al. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:44–50. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129354.31318.f1. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000129354.31318.f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnet C, Fillet G, Mounier N, et al. CHOP alone compared with CHOP plus radiotherapy for localized aggressive lymphoma in elderly patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:787–792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0722. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]