Abstract

Background

Cabazitaxel significantly improves overall survival (OS) versus mitoxantrone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel failure. We examined patient survival at 2 years and tumour-related pain with cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone.

Methods

Updated TROPIC data (cut-off 10 March 2010) were used to compare 2-year survival between treatment groups and assess patient demographics and disease characteristics. Factors prognostic for survival ≥2 years were assessed. Pain and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status were evaluated in the overall patient population.

Results

Median follow-up was 25.5 months. After 2 years, more patients remained alive following cabazitaxel than mitoxantrone [odds ratio 2.11; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.33–3.33]. Treatment with cabazitaxel was prognostic for survival ≥2 years. Demographics/baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment arms irrespective of survival. Pain at baseline and pain response were comparable between treatment groups. Average daily pain performance index was lower for cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone (all cycles; 95% CI –0.27 to –0.01; P = 0.035) and analgesic scores were similar. Grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathies were uncommon and comparable between treatment groups.

Conclusions

Cabazitaxel prolongs OS at 2 years versus mitoxantrone and has low rates of peripheral neuropathy. Palliation benefits of cabazitaxel were comparable to those of mitoxantrone.

The study was registered with www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00417079).

Keywords: cabazitaxel, symptom relief, palliative care, prostate cancer, treatment response, quality of life

introduction

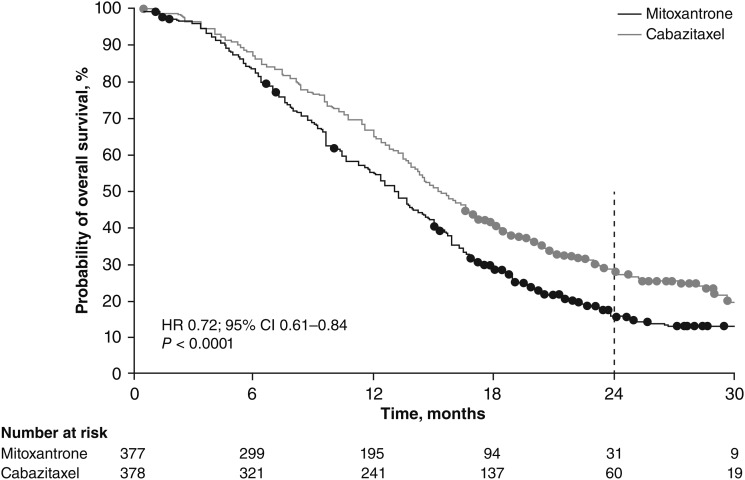

In the past 3 years, several new agents have demonstrated a survival benefit in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) previously treated with docetaxel. Cabazitaxel is a next-generation taxane that has preclinical activity against a range of tumour types (Vrignaud, et al. manuscript submitted), the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier (Semiond, et al. manuscript submitted) and a safety profile consistent with other chemotherapies [1–3]. In the phase III TROPIC trial, cabazitaxel plus prednisone/prednisolone significantly improved overall survival (OS) in patients with mCRPC versus mitoxantrone plus prednisone/prednisolone, with a 30% reduction in the risk of death [hazard ratio (HR) 0.70; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59–0.83; P < 0.0001; data cut-off 25 September 2009] [4]. Based on the results of the TROPIC trial, cabazitaxel (25 mg/m2 once every 3 weeks) plus prednisone was approved by the EMA, FDA and other national health authorities for the treatment of men with metastatic ‘hormone-refractory’ prostate cancer whose disease has progressed after receiving a docetaxel-containing regimen [2, 3]. Extended follow-up (cut-off 10 March 2010) demonstrated continued divergence of the survival curves (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.61–0.84; P < 0.0001) [5].

While the primary aim of therapy for mCRPC is to extend survival, tumour-related pain is associated with increased morbidity, reduced performance status and psychological deterioration [6, 7]. In addition, peripheral neuropathies, a known side-effect of taxanes, can be incapacitating for patients [8].

In this TROPIC trial update, we present follow-up data on the subgroup of patients who survived ≥2 years. Furthermore, we examine the impact of cabazitaxel plus prednisone/prednisolone compared with mitoxantrone plus prednisone/prednisolone on pain, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) and the occurrence of peripheral neuropathies.

patients and methods

The design of the TROPIC study has been described previously [4]. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00417079).

We conducted analyses of several pre-specified end points. Patients alive at ≥2 and <2 years were compared between treatment groups, and a multivariate analysis of factors prognostic for survival was conducted. Data from analyses of present pain intensity (PPI) and analgesic score are reported. Information on ECOG PS deterioration was collected while patients were on treatment. An analysis of occurrence of new or worsening peripheral neuropathies during treatment was also carried out (see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

end points and statistical analysis

overall survival

OS was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The percentage of patients alive at ≥2 years was compared between treatment groups using a χ2-test. To identify prognostic factors for long-term survival of ≥2 years, candidate factors were assessed by multivariate analysis (see supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

pain and analgesic assessment

Pain response and pain progression were pre-specified end points. Pain was assessed using both the McGill–Melzack questionnaire [9], to assess PPI, and an analgesic scoring method (adapted from 10) (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Pain was assessed before each treatment cycle and at the end of the study treatment visit. Pain was evaluated every 6 weeks during the first 6 months of follow-up, and every 3 months thereafter, until documented progression or initiation of other anticancer therapy. Area under the curve (AUC) of PPI and analgesic score were calculated. The average daily PPI and analgesic score for each patient was defined as the AUC of PPI or analgesic score divided by the number of days on which PPI or analgesic score was assessed. Additional detail is provided in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

performance status

Patients with an ECOG PS of 0–2 were enrolled. ECOG PS was assessed before enrolment and at the start and end of each cycle in the intent-to-treat population, until the end of treatment. This analysis recorded changes in ECOG PS on treatment.

peripheral neuropathies

Neuropathy grade at baseline and during treatment was recorded. New or worsening neuropathy was compared between treatments using Fisher's exact test.

results

Between 2 January 2007 and 23 October 2008, 755 patients from 146 centres in 26 countries were randomised within the TROPIC study. At the time of data cut-off (10 March 2010) for the updated analysis, 585 death events (77.5%) had occurred. With time to death used as the duration of follow-up in patients who died before this date, and survival times censored for surviving patients, the median follow-up was 13.7 months. Alternatively, if deaths were censored and survival times were considered events, the median follow-up for both treatment groups combined was 25.5 months (interquartile range: 20.7–30.0 months). Sixty (15.9%) of 378 patients in the cabazitaxel group and 31 (8.2%) of 377 patients in the mitoxantrone group survived ≥2 years (odds ratio 2.11; 95% CI 1.33–3.33). Based on the updated Kaplan–Meier curve (Figure 1), the probability of surviving ≥2 years was 27% (95% CI 23% to 32%) with cabazitaxel versus 16% (95% CI 12% to 20%) with mitoxantrone. Baseline demographic and baseline disease characteristics were well balanced within and between patients who survived ≥2 years and <2 years (Table 1). Patients surviving ≥2 years received a slightly higher median number of cycles versus patients surviving <2 years in both the cabazitaxel [a median of 10 (range 1–10) and 6 (range 1–10) treatment cycles, respectively] and the mitoxantrone groups [a median of 6 (range 1–10) and 4 (range 1–10) treatment cycles, respectively]. Furthermore, in the cabazitaxel group, patients who survived ≥2 years were less likely to discontinue treatment due to disease progression than patients in the mitoxantrone group (Table 1). Adverse prognostic factors were similar between treatment groups in patients who survived ≥2 years (Table 1). Tumour-related symptoms at baseline, including pain as measured by analgesic use, were comparable with the overall patient population enrolled in TROPIC (Table 2) [4].

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of the probability of survival of patients receiving mitoxantrone or cabazitaxel (updated analysis: cut-off 10 March 2010). Originally published in Oudard [5]. With permission from Future Medicine Ltd.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographics and disease characteristics according to OS

| OS ≥2 years |

OS <2 years |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabazitaxel | Mitoxantrone | Cabazitaxel | Mitoxantrone | |

| Total population, N (%) | 60 (15.9) | 31 (8.2) | 318 (84.1) | 346 (91.8) |

| Median age, years (range) | 69 (52–83) | 64 (52–85) | 67 (46–92) | 67 (47–89) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 60 (100) | 31 (100) | 290 (91.2) | 313 (90.5) |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 28 (8.8) | 33 (9.5) |

| Median PSA, ng/ml (range) | 122.8 (9–3205) | 63.4 (7–2268) | 152.0 (2–7842)a | 136.6 (2–11,220)b |

| Measurable disease, n (%) | 30 (50) | 14 (45.2) | 171 (53.8) | 190 (54.9) |

| Visceral disease (liver and/or lung), n (%) | 9 (15.0) | 6 (19.4) | 81 (25.5) | 83 (24.0) |

| Patients completing planned 10 cycles of study treatment, n (%) | 32 (53.3) | 8 (25.8) | 77 (24.8)a | 42 (12.4)c |

| Prior chemotherapy regimens, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 39 (65.0) | 20 (64.5) | 221 (69.5) | 248 (71.7) |

| ≥2 | 21 (35.0) | 11 (35.5) | 97 (30.5) | 98 (28.3) |

| Pain at baseline,d n (%) | 14 (23.3) | 7 (22.6) | 160 (50.3) | 161 (46.5) |

| Median haemoglobin, g/dl (range) | 12.6 (9.6–15.6) | 12.7 (10.8–15.2) | 11.9a (7.3–18.5) | 12.0c (7.6–16.0) |

| Median number of cycles (range) | 10 (1–10) | 6 (1–10) | 6 (1–10)a | 4 (1–10)c |

| Median relative dose intensity, % (range) | 95.5 (67.2–100.4) | 98 (74.8–102.8) | 96.2 (49–108.2)a | 97.1 (42.5–106)c |

| Time from last docetaxel treatment to disease progression, n (%) | ||||

| ≤3 months | 37 (61.7) | 16 (51.6) | 236 (74.2) | 269 (77.7) |

| >3 months | 21 (35.0) | 15 (48.4) | 81 (25.5) | 75 (21.7) |

| Missing | 2 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Median time from last docetaxel dose to disease progression, months | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Median total prior docetaxel dose, mg/m2 | 519.4 | 526.9 | 586.0 | 529.4 |

| Median time from last docetaxel dose to randomisation, months | 6.2 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Median time from first hormonal therapy to randomisation, years | 6.1 | 5.5e | 3.9f | 3.8g |

| Main reasons for treatment discontinuation, n (%) | ||||

| Completed study treatment period | 31 (51.7) | 8 (25.8) | 74 (23.3) | 38 (11.0) |

| Disease progression | 18 (30.0) | 18 (58.1) | 162 (50.9) | 249 (72.0) |

| Adverse event | 8 (13.3) | 3 (9.7) | 59 (18.6) | 29 (8.4) |

CbzP, cabazitaxel plus prednisone; MP, mitoxantrone plus prednisone.

an = 311.

bn = 339.

cn = 340.

dPain was assessed using the McGill–Melzack PPI scale and analgesic score derived from analgesic consumption.

en = 30.

fn = 315.

gn = 343.

Table 2.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics

| Cabazitaxel (n = 378) | Mitoxantrone (n = 377) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median, years (range) | 68 (46–92) | 67 (47–89) |

| ≥75 years, n (%) | 69 (18.3) | 70 (18.6) |

| ECOG PS 0/1, n (%) | 350 (92.6) | 344 (91.2) |

| Pain at baseline,a n (%) | 174 (46.0) | 168 (44.6) |

| Analgesic use at baseline, n (%) | 255 (67.4) | 242 (64.2) |

| Median time from last docetaxel dose to disease progression, months | 0.8 | 0.7 |

aPain was assessed using the McGill–Melzack PPI scale and analgesic score derived from analgesic consumption.

In the multivariate analysis, binary variables identified as prognostic factors for survival ≥2 years were rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) at baseline, treatment group (cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone), baseline pain and time from last docetaxel dose to randomisation in TROPIC (<6 versus ≥6 months). Continuous variables identified as prognostic factors were time in years from first hormone treatment to enrolment in TROPIC and baseline alkaline phosphatase (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors prognostic for survival for ≥2 years (intent-to-treat population; multivariate logistic regression; stepwise selection method)

| Factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Rising PSA at baseline, yes versus no | 2.330 (1.004–5.407) | 0.0488 |

| Treatment, cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone | 1.849 (1.055–3.241) | 0.0318 |

| Time from first hormone treatment to enrolment, years | 1.134 (1.043–1.233) | 0.0033 |

| Baseline alkaline phosphatase | 0.945 (0.916–0.976) | 0.0005 |

| Baseline pain, yes versus no | 0.482 (0.268–0.867) | 0.0149 |

| Time from last docetaxel dose to randomisation, <6 months versus ≥6 months | 0.410 (0.238–0.707) | 0.0013 |

Odds ratio of 1 indicates that presence of factor does not affect odds of outcome; odds ratio >1 indicates that presence of factor is associated with greater odds of outcome); odds ratio <1 indicates that presence of factor is associated with lower odds of outcome.

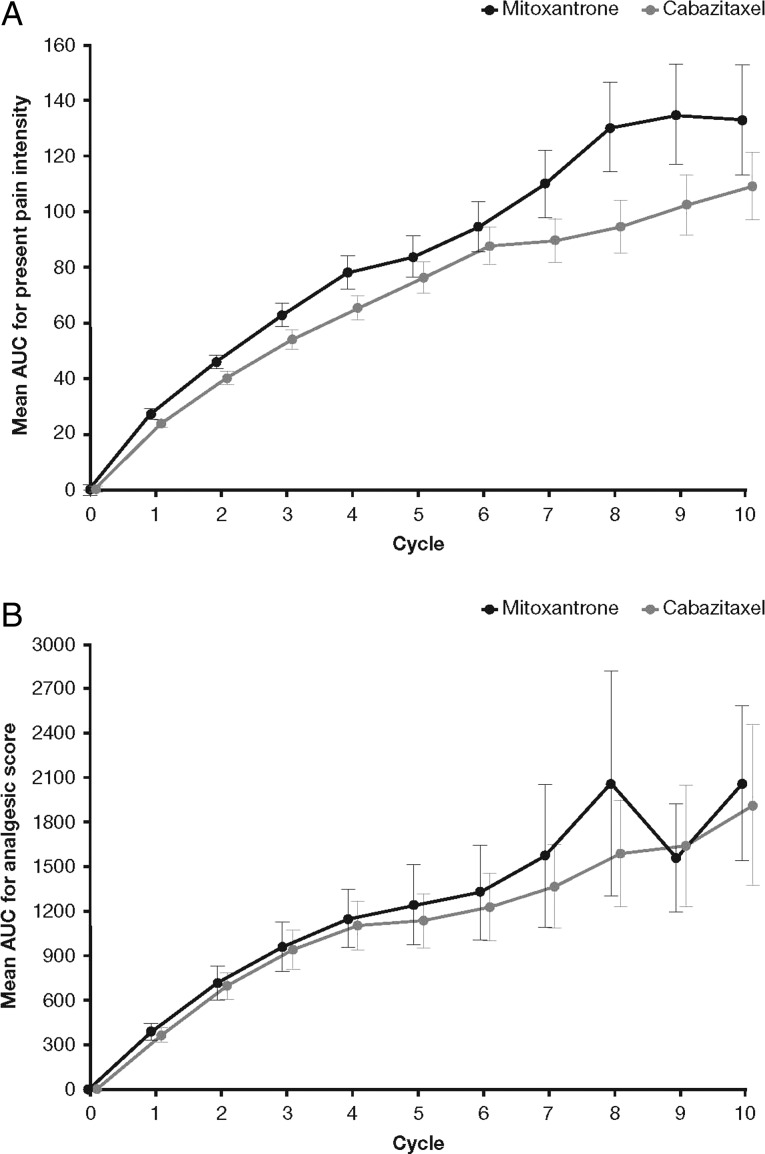

The mean AUC of PPI was lower for cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone (Figure 2A). The average daily PPI score was reduced by 0.138 [95% CI –0.27 to –0.01; P = 0.035 (t-test)] during treatment with cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone. Mean AUC for analgesic score was similar between the two treatment groups, albeit slightly lower in the cabazitaxel group versus the mitoxantrone group (Figure 2B). Average daily analgesic scores were similar for cabazitaxel and mitoxantrone [95% CI –5.06 to 6.06; P = 0.9 (t-test)] and changes in PPI scores were similar for cabazitaxel and mitoxantrone (improvement in 21.3% versus 18.2%, worsening in 32.4% versus 32.1%, and stabilisation in 46.2% versus 49.7%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Mean AUC for (A) PPI and (B) analgesic score, by treatment cycle. Part A originally published in Oudard [5]. With permission from Future Medicine Ltd.

The median time to pain progression was 11.1 months in the cabazitaxel group and was not reached in the mitoxantrone group because a large proportion of patients was censored [279 (74.0%)]. There was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups in time to pain progression [P = 0.5 (stratified log-rank test)] or pain response [9.2% cabazitaxel versus 7.7% mitoxantrone; P = 0.6 (χ2-test)].

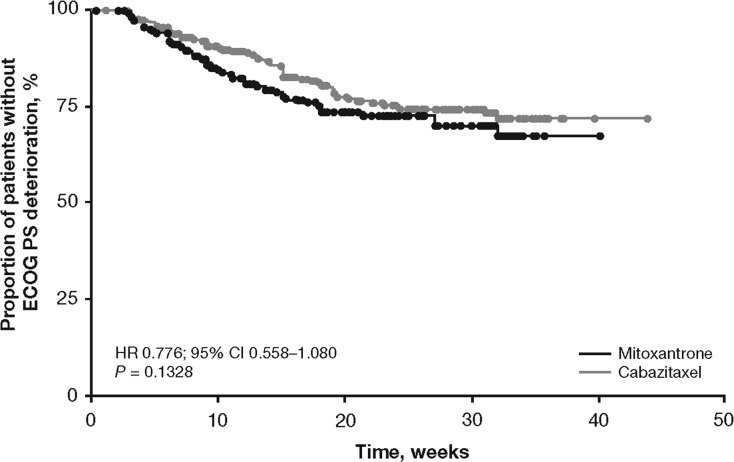

Most patients had an ECOG PS ≤1 at baseline (Table 2) and very few had PS deterioration during treatment (cabazitaxel versus mitoxantrone: deterioration in 19.6% versus 19.8%; improvement in 1.1% versus 2.2%; stabilisation in 79.3% versus 78.0%, respectively). Patients who received cabazitaxel had a statistically non-significant delay in ECOG PS deterioration compared with mitoxantrone [P = 0.1328; HR 0.776; 95% CI 0.558–1.080 (Figure 3)].

Figure 3.

Time to ECOG PS deterioration.

New or worsening peripheral sensory neuropathy/peripheral motor neuropathy was observed in 5.4%/8.4% (20/31 of 371) of patients in the cabazitaxel group versus 1.3%/2.2% (5/8 of 371 patients) of patients in the mitoxantrone group, respectively [P = 0.0035/P = 0.0002 (Fisher's exact test); Table 4]. Overall, the majority of new or worsening peripheral neuropathy was grade 1/2; three patients in each group had grade ≥3. In the cabazitaxel group, only one (5.6%) patient with peripheral sensory neuropathy worsened from grade 1 to grade 3 and two (10.0%) patients with peripheral motor neuropathy worsened from grade 1 to grade 2, compared with baseline. No patient receiving mitoxantrone reported worsening neuropathy. The rate of new grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathies was the same in each group [three patients each (0.8%)]. Only one patient (0.3%) in each treatment group developed drug-related grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathy.

Table 4.

Shift tables of incidence

| Cabazitaxel (N = 371) |

Mitoxantrone (N = 371) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline statusa | Post-baseline statusb, n (%) | Baseline statusa | Post-baseline statusb, n (%) | ||

| (A) Peripheral sensory neuropathy | |||||

| Grade 0, n = 351 | No change | 332 (94.6) | Grade 0, n = 350 | No change | 345 (98.6) |

| Increased to | Increased to | ||||

| Grade 1 | 15 (4.3) | Grade 1 | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Grade 2 | 4 (1.1) | Grade 2 | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Grade 1, n = 18 | No change | 17 (94.4) | Grade 1, n = 19 | No change | 19 (100) |

| Increased to Grade 3 | 1 (5.6) | ||||

| Grade 2, n = 2 | No change | 2 (100) | Grade 2, n = 2 | No change | 2 (100) |

| (B) Peripheral motor neuropathy/neuropathy peripheral | |||||

| Grade 0, n = 351 | No change | 322 (91.7) | Grade 0, n = 348 | No change | 340 (97.7) |

| Increased to | Increased to | ||||

| Grade 1 | 17 (4.8) | Grade 1 | 4 (1.1) | ||

| Grade 2 | 10 (2.8) | Grade 2 | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Grade 3 | 1 (0.3) | Grade 3 | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Grade 1, n = 20 | No change | 18 (90.0) | Grade 1, n = 22 | No change | 22 (100) |

| Increased to Grade 2 | 2 (10.0) | ||||

| Grade 3, n = 1 | No change | 1 (100) | |||

aBaseline events were those reported before treatment (visit = 0).

bPost-baseline events were treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) or pretreatment AEs still ongoing during treatment (visit >0); patients with ≥grade 1 AEs at baseline but no AEs during treatment were assigned the same grade as baseline grade.

discussion

In recent years, several therapies have demonstrated an OS benefit in patients with mCRPC [4, 11–13]. Cabazitaxel significantly improved OS in patients with mCRPC post-docetaxel, with a 30% reduction in risk of death (cut-off 25 September 2009) [4]. Updated analyses of OS (cut-off 10 March 2010) show that this survival benefit was sustained after long-term follow-up. Baseline patient and disease characteristics, as well as treatment history and adverse prognostic factors, were consistent between mitoxantrone and cabazitaxel treatment groups. Patients who survived ≥2 years in the cabazitaxel group were less likely to discontinue treatment due to disease progression compared with those in the mitoxantrone group. As such, it seems logical to conclude that the difference in survival between the two treatment groups is likely due to a treatment effect of cabazitaxel. However, no further predictors of outcome were identified.

Although increased survival is the primary aim for mCRPC treatment, relief of symptoms associated with the disease, particularly pain, should be a key concern, since it significantly impacts patient quality of life and may be undertreated [14]. Mitoxantrone is known to provide palliation of tumour-related pain and accordingly is often used in this setting, despite lack of evidence to suggest an OS benefit [10, 15–17]. We have shown that cabazitaxel provides similar palliation of pain to mitoxantrone, as measured by PPI and analgesic score. Other treatments have demonstrated the ability to provide palliation of symptoms in comparison with prednisone. Abiraterone acetate showed improved fatigue and pain [18, 19], while enzalutamide showed improvements in quality of life [13]. Furthermore, results from a recent study investigating radium-223 chloride versus placebo [20] have shown that treatment with radium-223 chloride prolongs the time to the first skeletal-related events, known to contribute to tumour-related pain [21].

ECOG PS is a further measure of quality of life, and here we show that ECOG PS deterioration was similar between treatment groups, despite patients in the cabazitaxel group receiving a greater number of treatment cycles versus those in the mitoxantrone group. These results suggest that any adverse events observed with cabazitaxel may only have a moderate influence on overall patient status. One such adverse event frequently observed in previous studies of patients receiving treatment with taxanes is peripheral neuropathy [8], which can affect quality of life. Ongoing compassionate-use and expanded-access programmes investigating cabazitaxel in real-world populations have reported a lower incidence of peripheral neuropathies with cabazitaxel compared with first-generation taxanes [1, 8, 22]. We found a similarly low rate of these events in the TROPIC trial: 0.8% of patients experienced grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathy. Furthermore, few patients with pre-existing grade 1/2 neuropathy reported worsening of symptoms.

Prognostic factors are valuable tools to predict outcomes based on patient and disease characteristics. We carried out analyses to assess whether factors found to be prognostic for survival in previous studies [23] were also prognostic for survival ≥2 years in TROPIC. Some previously defined factors were indeed prognostic in our analyses, including pain, alkaline phosphatase and PSA. We also identified that a longer time from first hormone treatment to enrolment was prognostic for survival ≥2 years. This finding is not unexpected, as patients with more aggressive disease would be expected to have a shorter time between first hormone treatment and study enrolment.

Although in recent years, the availability of agents that improve survival in patients with mCRPC has increased, minimal data are available on optimal sequencing strategies for these therapies. For example, data collected on post-study treatments in TROPIC do not show a clear pattern of treatment sequencing (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). As treatment decisions are increasingly influenced by financial considerations, the availability of robust data on sequencing is particularly important to maximise the value of available therapies.

In conclusion, treatment with cabazitaxel is associated with a significant long-term OS benefit compared with mitoxantrone. Furthermore, treatment with cabazitaxel was associated with an impact on pain associated with mCRPC, and had a safety profile consistent with other chemotherapies, with low rates of peripheral neuropathy. Further studies are required to refine our understanding of predictors of outcome that will aid in defining the optimal sequence of agents for patients with mCRPC.

funding

This work was supported by Sanofi.

disclosure

AB has received honoraria from Sanofi, Janssen, Novartis, Amgen and Roche. JSdB, SO, AOS and BT have served as paid consultants/advisors for Sanofi. MO is in a steering committee for a Sanofi-sponsored study. AOS, AB, MO and SH have received research funding from Sanofi. AOS and BT have acted as investigators for Sanofi. LS and JD are employees of Sanofi; LS holds stocks and shares in Sanofi. GG and IK have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families who took part in the study, the coordinators and the investigators. In addition, we thank Peter Trask for his critical review of this manuscript. This analysis was sponsored by Sanofi. The authors received editorial support in the form of medical writing services from Melissa Purves of MediTech Media, funded by Sanofi.

references

- 1.Malik Z, di Lorenzo G, Basaran M, et al. Cabazitaxel (Cbz) + prednisone (P) in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) previously treated with docetaxel (D): interim results from compassionate-use programme (CUP) and early-access programme (EAP). European Society of Medical Oncology Congress; 28 September–2 October, 2012; Vienna, Austria. Poster 931P. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanofi. JEVTANA® (cabazitaxel) Injection, Summary of Product Characteristics. Paris, France: 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002018/human_med_001428.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. (4 April 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanofi U.S. LLC. JEVTANA® (cabazitaxel) Injection, Prescribing Information. Bridgewater, NJ, USA, 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/201023lbl.pdf. (4 April 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oudard S. TROPIC: Phase III trial of cabazitaxel for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7:497–506. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.23. doi:10.2217/fon.11.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colloca G, Colloca P. Health-related quality of life assessment in prospective trials of systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer: which instrument we need? Med Oncol. 2011;28:519–527. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9495-2. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshields T, Potter P, Olsen S, et al. Documenting the symptom experience of cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.suponc.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JJ, Swain SM. Peripheral neuropathy induced by microtubule-stabilizing agents. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1633–1642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0543. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1756–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:983–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apolone G, Corli O, Caraceni A, et al. Pattern and quality of care of cancer pain management. Results from the Cancer Pain Outcome Research Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1566–1574. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605053. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. 2012. http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/08%20Prostate%20Cancer_LR%20March%2013th%202012.pdf. (4 April 2013, date last accessed)

- 16.Kantoff PW, Halabi S, Conaway M, et al. Hydrocortisone with or without mitoxantrone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: results of the cancer and leukemia group B 9182 study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2506–2513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Prostate Cancer (Version 2.2013) http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. (4 April 2013, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Logothetis CJ, Basch E, Molina A, et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate and prednisone compared with placebo and prednisone on pain control and skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: exploratory analysis of data from the COU-AA-301 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1210–1217. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70473-4. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sternberg CN, Molina A, North S, et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate on fatigue in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1017–1025. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds585. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Updated analysis of the phase III, double-blind, randomized, multinational study of radium-223 chloride in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients with bone metastases (ALSYMPCA) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl):LBA4512. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gater A, Abetz-Webb L, Battersby C, et al. Pain in castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-88. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanofi U.S. LLC. NJ, USA: Bridgewater; 2010. TAXOTERE® (docetaxel) Injection Concentrate, Intravenous Infusion (IV) Prescribing Information. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/020449s059lbl.pdf. (4 April 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, de Wit R, et al. Prediction of survival following first-line chemotherapy in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:203–211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2514. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.