Abstract

Background

Meta-analyses were conducted to characterize patterns of mutation incidence in non small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Design

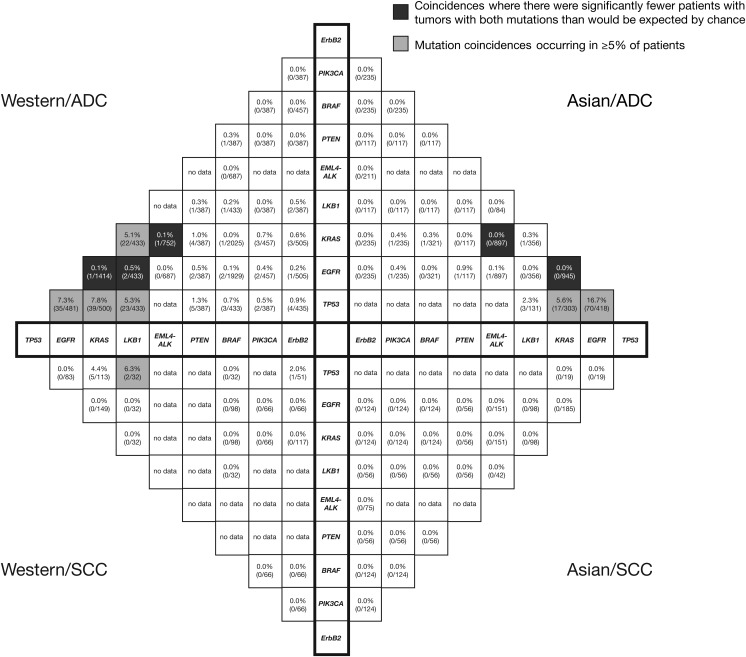

Nine genes with the most complete published mutation coincidence data were evaluated. One meta-analysis generated a ‘mutMap’ to visually represent mutation coincidence by ethnicity (Western/Asian) and histology (adenocarcinoma [ADC] or squamous cell carcinoma). Another meta-analysis evaluated incidence of individual mutations. Extended analyses explored incidence of EGFR and KRAS mutations by ethnicity, histology, and smoking status.

Results

Genes evaluated were TP53, EGFR, KRAS, LKB1, EML4-ALK, PTEN, BRAF, PIK3CA, and ErbB2. The mutMap highlighted mutation coincidences occurring in ≥5% of patients, including TP53 with KRAS or EGFR mutations in patients with ADC, and TP53 with LKB1 mutation in Western patients. TP53 was the most frequently mutated gene overall. Frequencies of TP53, EGFR, KRAS, LKB1, PTEN, and BRAF mutations were influenced by histology and/or ethnicity. Although EGFR mutations were most frequent in patients with ADC and never/light smokers from Asia, and KRAS mutations were most frequent in patients with ADC and ever/heavy smokers from Western countries, both were detected outside these subgroups.

Conclusions

Potential molecular pathology segments of NSCLC were identified. Further studies of mutations in NSCLC are warranted to facilitate more specific diagnoses and guide treatment.

Keywords: geography, histology, lung cancer, mutation coincidence, oncogenes

introduction

Non small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for ∼85% of primary lung cancers, the most common subtypes being adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [1]. Recently, genetic profiling has identified driver mutations, believed to contribute to early carcinogenesis, in over 80% of ADC cases and ∼47% of SCC cases. Supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online shows how understanding of driver mutations has evolved, from reports of KRAS mutations in ADC in 1987 [2], to reports of fusions between KIF3B and RET in 2012 [3].

Therapies targeting driver mutations have provided promising outcomes in relevant populations. For example, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) gefitinib and erlotinib have shown superiority (progression-free survival [PFS] and objective response rate [ORR]) over platinum-based doublet chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of stage IIIB/IV NSCLC with EGFR mutations [4–8]. Activating KRAS mutations also frequently occur in NSCLC; however, while compounds are in development, attempts to target these mutations or downstream signaling pathways have shown limited therapeutic success to date [9].

It is also important to consider mutations in tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) associated with NSCLC, including TP53, LKB1, and PTEN. As TSG mutations often coincide with oncogenic mutations [10], analyses of coincidence may facilitate subdivision of molecular pathology segments. Such analyses should account for ethnicity and histology, which can both impact on mutation incidence [11–13].

Here, we report two meta-analyses: the first investigated patterns of mutation coincidence, and the second investigated incidences of individual mutations, both according to ethnicity and histology. In addition, extended analyses explored the incidence of EGFR and KRAS mutations by ethnicity, histology, and smoking status. These analyses add to ongoing sequencing efforts in NSCLC [14].

materials and methods

literature search

A Medline search identified journal articles reporting studies of mutations in NSCLC (all stages) published before March 2012. The following search criteria were used: [lung OR non small cell lung OR NSCLC] AND [adeno* OR squamous] AND [tumour OR tumor] AND [mutation* OR fusion OR translocation]. The following were excluded: review articles; articles not in English; articles reporting studies where not all samples were screened for all reported genes (e.g. subsets of samples found to be positive/negative for one mutation were subsequently screened for additional mutations); articles with data not assigned to a defined ethnic group or collected from a single center in Europe, North America, Australia, or Asia; articles not reporting histology; articles reporting data exclusively from tumor-derived cell lines. If human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines were studied, only data from human tumors were included. If the same study was analyzed in several articles, only the article reporting the most complete data was included. Supplemental data, available at Annals of Oncology online were included from 126 patients at the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute, China, and 84 at the Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, UK (supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

meta-analysis of mutation coincidence (mutMap)

Articles were reviewed to identify studies reporting the coincidence of mutations in ≥2 genes. References cited in these articles were also searched for additional relevant articles.

Mutation coincidence data were analyzed by ethnicity (Western [Europe, North America, or Australia] or Asian [China, Hong Kong, Jap an, Korea, Singapore, or Taiwan]) and histology (ADC or SCC). Overall, data were analyzed for four patient subgroups: Western/ADC, Western/SCC, Asian/ADC, and Asian/SCC. Data were collated for the nine genes with the most complete mutation coincidence data (not necessarily the most commonly mutated genes in NSCLC). A ‘mutMap’ was created to visually represent mutation coincidence.

meta-analysis of individual mutations

For the nine genes included in the mutMap, a separate meta-analysis evaluated incidences of individual mutations in the same four patient subgroups.

For a comprehensive evidence base, articles retrieved in the original literature search were reviewed again to identify additional articles reporting data for individual mutations. A further Medline search was also carried out using the Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) gene name (and any pseudonyms) together with the following criteria: [lung OR non small cell lung OR NSCLC] AND [adeno* OR squamous] AND [tumour OR tumor].

extended analyses of EGFR and KRAS mutations

Incidences of EGFR and KRAS mutations were explored further in a subsequent expansion of the meta-analyses. Articles were again reviewed to identify studies reporting EGFR or KRAS mutations in (i) NSCLC of non-ADC histology (excluding unclassified NSCLC) or (ii) NSCLC of any histology in patients with a defined smoking status (never/light or ever/heavy [according to the definitions of the original studies]). The incidence of these mutations was evaluated in NSCLC of non-ADC histology by ethnicity (Europe, North America, China [including Hong Kong and Taiwan], Japan, or Korea) and in NSCLC of any histology by ethnicity and smoking status.

statistical analyses

For the two meta-analyses, differences between the patient subgroups were tested for statistical significance using Fisher's exact test, with Bonferroni correction to account for multiple testing [15]; as 139 statistical tests were carried out, the Bonferroni correction factor was 139 times the uncorrected P-value (Pcorr). Differences were considered statistically significant at Pcorr < 0.05.

Extended analyses were only reported descriptively.

results

included studies

In total, 94 studies were included in one or more analyses: 27 in the mutMap, 68 in the meta-analysis of individual mutations, and 59 in each of the extended analyses (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The most common analysis method was sequencing: 71 studies carried out sequencing alone or with prescreening, and 16 used sequencing for part of the analysis alongside other methods (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Articles reporting data on TSGs were examined to assess their scope. Studies of LKB1 and PTEN mutations screened the full coding sequence of the genes. Screening of TP53 was more variable; however, all reports included exons 5–8, where 90% of mutations have been reported [16].

Generally, studies included more males than females: the male : female ratio was 1.1 : 1 across studies of Western populations and 1.4 : 1 in Asian populations (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). There were also more smokers than non smokers: the smoker : non smoker ratio was 3.0 : 1 in Western populations and 1.2 : 1 in Asian populations. Mean/median age was reported in 52 studies, 41 of which reported a mean/median age of 60–70 years.

mutation coincidence (mutMap)

The nine genes with the most complete mutation coincidence data across the four patient subgroups were TP53, EGFR, KRAS, LKB1, EML4-ALK, PTEN, BRAF, PIK3CA, and ErbB2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

‘Compass’ plot depicting the ‘mutMap’: coincidences of mutations across four non small-cell lung cancer patient subgroups (Western/ADC, Western/SCC, Asian/ADC, Asian/SCC). ADC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

There were several mutation coincidences with frequencies of ≥5%: TP53 mutation with KRAS or EGFR mutation in the Western/ADC and Asian/ADC subgroups; LKB1 mutation with TP53 or KRAS mutation in the Western/ADC subgroup; and TP53 mutation with LKB1 mutation in the Western/SCC subgroup. These coincidences were not significantly different from what would be expected by chance given the individual mutation frequencies (Pcorr > 0.05).

EGFR and KRAS mutations were generally mutually exclusive; these exclusivities were significant for the Western/ADC (Pcorr = 1.8 × 10−36) and Asian/ADC (Pcorr = 1.9 × 10−27) subgroups. EGFR and KRAS mutations were also exclusive of EML4-ALK mutation in the Western/ADC, Asian/ADC, and Asian/SCC subgroups (no data for Western/SCC subgroup). These exclusivities were significant in the Western/ADC subgroup for both EGFR and EML4-ALK (Pcorr = 6.8 × 10−4) and KRAS and EML4-ALK (Pcorr = 6.6 × 10−4). In the Asian/ADC subgroup, only the exclusivity between EGFR and EML4-ALK was significant (Pcorr = 7.7 × 10−7). In addition, in the Western/ADC subgroup, there were fewer patients with both EGFR and LKB1 mutations than would be expected by chance (observed frequency, 0.5%; expected frequency, 3.1%; Pcorr = 0.02).

incidence of individual mutations

TP53 was the most frequently mutated gene (Table 1), with greater frequency in the Western/SCC subgroup than the Western/ADC subgroup (54.9% versus 30.8%; Pcorr = 3.2 × 10−4). Similarly, PTEN mutations were more common in the Asian/SCC subgroup than the Asian/ADC subgroup (9.8% versus 1.6%; Pcorr = 8.3 × 10−3). In contrast, EGFR and KRAS mutations were more common in ADC subgroups than SCC subgroups in both Western (EGFR, 19.2% versus 3.3%, Pcorr = 2.6 × 10−15; KRAS, 26.1% versus 6.4%, Pcorr = 3.4 × 10−9) and Asian populations (EGFR, 47.9% versus 4.6%, Pcorr = 1.8 × 10−85; KRAS, 11.2% versus 1.8%, Pcorr = 1.6 × 10−6). BRAF mutations were also more common in the Western/ADC subgroup than the Western/SCC subgroup (3.3% versus 0.2%; Pcorr = 1.3 × 10−2).

Table 1.

Incidence of individual mutations across the four non small-cell lung cancer patient subgroups

| Gene | Incidence of mutation, n/N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western/ADC | Western/SCC | Asian/ADC | Asian/SCC | |

| TP53a | 164/532 (30.8) | 62/113 (54.9) | 325/978 (33.2) | 64/179 (35.8) |

| EGFRa | 940/4890 (19.2) | 11/334 (3.3) | 1492/3117 (47.9) | 22/474 (4.6) |

| KRASa | 613/2352 (26.1) | 12/187 (6.4) | 236/2114 (11.2) | 5/284 (1.8) |

| LKB1a | 99/610 (16.2) | 13/137 (9.5) | 22/550 (4.0) | 0/166 (0.0) |

| EML4-ALK | 55/856 (6.4) | 4/89 (4.5) | 71/1326 (5.4) | 5/277 (1.8) |

| PTENa | 25/419 (6.0) | 0/12 (0.0) | 4/248 (1.6) | 12/123 (9.8) |

| BRAFa | 66/2028 (3.3) | 1/408 (0.2) | 5/321 (1.6) | 0/124 (0.0) |

| PIK3CA | 6/475 (1.3) | 1/71 (1.4) | 4/235 (1.7) | 8/124 (6.5) |

| ErbB2 | 7/505 (1.4) | 2/117 (1.7) | 20/712 (2.8) | 1/259 (0.4) |

aSignificant differences between patient subgroups were observed in the incidences of mutations in the following genes:

TP53: Western/ADC versus Western/SCC (Pcorr = 3.2 × 10−4).

EGFR: Western/ADC versus Western/SCC (Pcorr = 2.6 × 10−15); Western/ADC versus Asian/ADC (Pcorr = 1.7 × 10−158); Asian/ADC versus Asian/SCC (Pcorr = 1.8 × 10−85).

KRAS: Western/ADC versus Western/SCC (Pcorr = 3.4 × 10−9); Western/ADC versus Asian/ADC (Pcorr = 1.1 × 10−35); Asian/ADC versus Asian/SCC (Pcorr = 1.6 × 10−6).

LKB1: Western/ADC versus Asian/ADC (Pcorr = 3.2 × 10−10); Western/SCC versus Asian/SCC (Pcorr = 3.3 × 10−3).

PTEN: Asian/ADC versus Asian/SCC (Pcorr = 8.3 × 10−3).

BRAF: Western/ADC versus Western/SCC (Pcorr = 1.3 × 10−2).

ADC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Regarding ethnicity, for ADC, EGFR mutations occurred more frequently in Asian than Western patients (47.9% versus 19.2%; Pcorr = 1.7 × 10−158), while KRAS and LKB1 mutations were more frequent in Western than Asian patients (KRAS, 26.1% versus 11.2%, Pcorr = 1.1 × 10−35; LKB1, 16.2% versus 4.0%, Pcorr = 3.2 × 10−10). For SCC, LKB1 mutations were significantly more frequent in the Western than Asian patients (9.5% versus 0.0%; Pcorr = 3.3 × 10−3).

EML4-ALK mutations were relatively common in the Western/ADC (6.4%), Western/SCC (4.5%), and Asian/ADC (5.4%) subgroups; PTEN mutations were relatively common in the Western/ADC (6.0%) and Asian/SCC (9.8%) subgroups; and PIK3CA mutations were also relatively common in the Asian/SCC subgroup (6.5%). However, mutations in EML4-ALK, PTEN, PIK3CA, ErbB2, and BRAF were rarer (0.0%–3.3%) in all other cases.

extended analyses of EGFR and KRAS mutations

While EGFR and KRAS mutations occurred more frequently in ADC, these mutations also occurred in tumors of non-ADC histology, although pooled frequencies varied by ethnicity (EGFR, 5.1%–12.7%; KRAS, 0.0%–10.4%; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). In general, EGFR mutations were more frequent in Asian populations and KRAS mutations were more frequent in Western populations.

In NSCLC of any histology, pooled frequencies of EGFR mutations ranged from 8.4% to 35.9% for ever/heavy smokers and from 37.6% to 62.5% for never/light smokers, depending on ethnicity (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Corresponding values for KRAS mutations were 6.7%–40.0% and 2.9%–11.4%, respectively.

discussion

These meta-analyses, which we believe are the largest such analyses to date, investigated mutation incidence in NSCLC to develop the first ‘mutMap’—a visual tool describing mutation coincidence by ethnicity and histology.

Mutations in EGFR, KRAS, EML4-ALK, and BRAF were all exclusive, supporting the view that a single driver mutation is required for oncogene addiction in lung tumors [17]. There was some variation in EGFR and KRAS mutation frequencies between studies, even when grouped by ethnicity and smoking status. As the majority of studies used sequencing, this may reflect more than a variation in mutation testing technique. In addition to tobacco, other environmental factors may contribute to the development of NSCLC, including exposure to radon, air pollution, and cooking oil vapor [18]. Although the involvement of these factors in the development of EGFR and KRAS mutations is not currently understood, differing patterns of environmental factors may contribute to variability in EGFR and KRAS mutation frequencies.

There were several coincidences of driver mutations with TSG mutations: a relevant proportion (≥5%) of ADC tumors had TP53 mutation with KRAS or EGFR mutation, and, in Western populations, relevant proportions of ADC or SCC tumors had TP53 and LKB1 mutations, and a relevant proportion of ADC tumors had KRAS and LKB1 mutations. Such data could help subdefine molecular pathology segments of NSCLC, which may be associated with patient outcomes: higher numbers of coincident mutations correlate with higher tumor grade and stage in ADC, with TP53 mutation rates specifically correlating with tumor grade [10].

Characterization of molecular pathology segments may help guide the development of novel targeted therapies and shape testing protocols, algorithms, or panels for diagnostic mutation testing in NSCLC. For example, combination therapies to target both oncogenic and TSG mutations may benefit patients within a relevant molecularly defined segment. There is already some precedent for this type of approach, including a planned trial of the erlotinib in combination with the phosphoinositide-3-kinase inhibitor BKM120 (which may be expected to compensate for inactivation of PTEN) [19].

EGFR mutations are known to occur most frequently in ADC tumors and those of non smoking patients [11, 12]. However, our analyses support screening for EGFR mutations outside of these groups, as EGFR mutations were present in non-ADC tumors and those of ever/heavy smokers. Furthermore, although PFS and ORRs with EGFR TKIs may be lower for non-ADC tumors than ADC tumors [20], two studies among the limited available data show improved PFS in patients with EGFR mutation-positive tumors of non-ADC histology when treated with EGFR TKIs compared with chemotherapy [6, 7].

Caution is advised when using these data to infer mutation incidence in different populations, since the meta-analyses depended on the available published data, which represent a small sample size with intrinsic limitations. For example, only the genes with the most mutation data were included in the meta-analyses, but other genes may play key roles in some populations, e.g. amplification of FGFR1 in SCC [21]. Also, analysis of the coincidence of three or more mutations was not practical due to the lack of published studies of large gene panels; however, some tumors may have more than 40 coincident mutations in putative oncogenes or TSGs [10]. The Cancer Genome Atlas [22, 23] and the Clinical Lung Cancer Genome Project [24] will provide further large-scale data on mutation coincidence in NSCLC in Western populations.

There were also insufficient data to include several key populations, including African and Latin American populations. Preliminary data suggest that EGFR and KRAS mutation frequencies in Latin American countries (EGFR, 33%; KRAS, 17%) lie between those in Western and Asian populations [25].

Variation in study design should also be considered. Although data were derived from NSCLC of any stage, there was some bias toward stage I/II tumors, as these are most commonly resected [26]. In addition, not all articles reported mutation types. Therefore, these meta-analyses categorized mutations by gene only, without reference to type or potential functional effect (e.g. synonymous substitutions, or non synonymous substitutions of unknown functional relevance).

Additionally, the meta-analyses were not designed to evaluate changes in mutation rates in patients who develop resistance to treatment. It is noted that, the EGFR T790M mutation, which has been reported at low frequency in untreated patients with stage IIIB/IV NSCLC and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0/1 (4.2%) [8], has been detected in 43.8%–50.0% of patients who become resistant to EGFR TKIs [27, 28].

Overall, these meta-analyses demonstrate that mutation profiles in NSCLC are heavily influenced by tumor histology, and the ethnicity and smoking history of patients. Despite these challenges, we have identified potential molecular pathology segments of NSCLC that combine oncogenic and TSG mutations. Advances in our understanding of mutation coincidence may be useful in enabling more specific diagnoses and guiding treatment paradigms. Large studies in Western populations are ongoing [23, 24], but similar studies in Asian populations are also warranted, particularly given the differences between mutation patterns in Western and Asian populations identified here.

funding

This work was supported by AstraZeneca.

disclosure

SD and JS are employees of AstraZeneca, and DB is a former employee of AstraZeneca. YLW has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis, and research funding from AstraZeneca and Roche.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Hannah FitzGibbon, PhD, of Complete Medical Communications.

references

- 1.Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Baade PD. The International Epidemiology of Lung Cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:819–831. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818020eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodenhuis S, van de Wetering ML, Mooi WJ, et al. Mutational activation of the K-ras oncogene. A possible pathogenetic factor in adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:929–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710083171504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY, et al. A transforming KIF5B and RET gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma revealed from whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:436–445. doi: 10.1101/gr.133645.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou C, Wu Y-L, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greulich H. The genomics of lung adenocarcinoma: opportunities for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:1200–1210. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haserlat SM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and gene amplification in non-small-cell lung cancer: molecular analysis of the IDEAL/INTACT gefitinib trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8081–8092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An SJ, Chen ZH, Su J, et al. Identification of enriched driver gene alterations in subgroups of non-small cell lung cancer patients based on histology and smoking status. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu P, Morrison C, Wang L, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in non-small cell lung carcinomas using whole-exome sequencing. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1270–1276. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310:170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucl Acids Res. 2011;39(Suppl. 1):D945–D950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazdar AF, Shigematsu H, Herz J, et al. Mutations and addiction to EGFR: the Achilles ‘heal’ of lung cancers? Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam WK, White NW, Chan-Yeung MM. Lung cancer epidemiology and risk factors in Asia and Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:1045–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trial of erlotinib and BKM120 in patients with advanced non small cell lung cancer previously sensitive to erlotinib. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01487265. (7 March 2013, date last accessed)

- 20.Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Kaira R, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib for non-adenocarcinoma non-small-cell lung cancer patients harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: a pooled analysis of published reports. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1032–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss J, Sos ML, Seidel D, et al. Frequent and focal FGFR1 amplification associates with therapeutically tractable FGFR1 dependency in squamous cell lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:62ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001451. Errata in: Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 130er2. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 66er2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute. The Cancer Genome Atlas. updated 2011 http://cancergenome.nih.gov/ (22 November 2011, date last accessed)

- 23.Hammerman PS, Hayes DN, Wilkerson MD, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas R. Identifying clinically relevant cancer genome alterations in lung cancer: The Clinical Lung Cancer Genome Project initiative. updated 2010 http://www.abstractsonline.com/plan/ViewAbstract.aspx?mID=2626&sKey=9269f5cb-5ea2-48c1-996d-e95d7b1d265e&cKey=7983f06c-92c1-4149-bf81-f7b64bcd8288&mKey=%7BE69F27FB-E294-49DA-92AC-DFC241A99F23%7D. (21 September 2011, date last accessed)

- 25.Arrieta O, Cardona AF, Federico Bramuglia G, et al. Genotyping non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Latin America. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1955–1959. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822f655f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice guidelines in oncology – version V.3.2012 (non-small-cell lung cancer) updated 2012 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. (6 December 2011, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Balak MN, Gong Y, Riely GJ, et al. Novel D761Y and common secondary T790M mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6494–6501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5764–5769. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.