Abstract

Geosmin and 2-MIB are responsible for the majority of earthy and musty events related to the drinking water. These two odorants have extremely low odor threshold concentrations at ng L−1 level in the water, so a simple and sensitive method for the analysis of such trace levels was developed by headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled to gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. In this study, the orthogonal experiment design L32 (49) was applied to arrange and optimize experimental conditions. The optimum was the following: temperatures of extraction and desorption, 65°C and 260°C, respectively; times of extraction and desorption, 30 min and 5 min, respectively; ionic strength, 25% (w/v); rotate-speed, 600 rpm; solution pH, 5.0. Under the optimized conditions, limits of detection (S/N = 3) were 0.04 and 0.13 ng L−1 for geosmin and 2-MIB, respectively. Calculated calibration curves gave high levels of linearity with a correlation coefficient value of 0.9999 for them. Finally, the proposed method was applied to water samples, which were previously analyzed and confirmed to be free of target analytes. Besides, the proposal method was applied to test environmental water samples. The RSDs were 2.75%~3.80% and 4.35%~7.6% for geosmin and 2-MIB, respectively, and the recoveries were 91%~107% and 91%~104% for geosmin and 2-MIB, respectively.

1. Introduction

Musty and earthy odors are troublesome in water samples (such as tap water, reservoirs, and lakes) because they dramatically influence the esthetic quality and consumer acceptability of the drinking water [1, 2]. Metabolites are produced in the process of degradation of green-blue algae, which are responsible for this malodor in water, especially during the period of algae blossom in summer [3–5]. The chemical by-products, geosmin (trans-1,10-dimethyl-trans-9-decalol) and 2-MIB (2-methylisoborneol), are commonly found in lakes and reservoirs, where people can smell the odor of these compounds in the drinking water even at the determination of 10 ng L−1 or less, but it would be difficult to identify and quantify these two trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [6–10]. Therefore, how to extract and enrich them tends to be the key step for qualitative and quantitative analysis at this trace level.

To date, a variety of techniques for extraction and enrichment have been established and applied for analyzing earthy and musty compounds. Among these techniques, closed-loop stripping analysis (CLSA) and some of its modified versions have been widely used for the extraction of trace amounts of malodor such as geosmin and 2-MIB in water samples. The result showed that CLSA was a good tool for the analysis of geosmin and 2-MIB at a low-level threshold [11]. However, it is labor-intensive and time-consuming. Some other methods, such as purge and trap coupled to gas chromatography with mass spectrometry [12, 13] or to GC-FID [14], liquid-liquid microextraction (LLME) [15], stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) [16–18], and solid-phase extraction (SPE) [19], can also be taken to detect the VOCs in water at ng L−1 levels. Although these techniques greatly improve the limits and sensitivity of detection, some shortcomings such as being unsuitable for the analysis of low-boiling-point odors and time-consuming (SPE, SBSE) [20, 21] and lacking the stability of droplet during extraction (LPME) restrict the extensive use of these methods. As technology advances, solid-phase microextraction (SPME) was first developed, and it was reported that headspace SPME (HS-SPME) was effective for collecting volatile organic compounds from Penicillium [22]. HS-SPME has become the most popular technique in pretreating and enriching a variety of water odors [23–27], because of requiring no solvents during extraction by HS-SPME, which cannot be achieved by LLME; being a simpler operation if compared with other methods as SPE, CLSA, and SBSE; and, the most important merit, being able to enrich the target selectively by suitable fiber, which cannot be obtained by SPE and LLME.

It had been reported that the efficiency of HS-SPME was subject to several factors such as extraction temperature, ionic strength, and rotate-speed. The method of “one factor at a time”, the traditional method for optimizing experiment conditions of HS-SPME or purge and trap (P&T), was to change the level of one factor while keeping others constant [12, 24, 26, 28], which was almost the only one to optimize these factors in current reports for determining trace VOCs in water samples. Obviously, this method is time-consuming when these factors and their levels reach a certain number. In addition, it often overlooks the interactions among the factors, despite having no interactions in this study. In this paper, however, the orthogonal experiment design was applied to arrange and optimize experiment conditions, including extraction temperature, desorption temperature, extraction time, solution pH, ionic strength, and rotate-speed. Besides, the process of mass spectrometry was optimized to improve the sensitivity and efficiency during the detection and analysis in this study. The good figures of merit for the analysis of the trace amount of odors in water samples have been obtained by combining them. Finally, the analytical method has been validated and applied to test on water samples.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and SPME Apparatus

Two categories of compounds commonly observed in water, geosmin and 2-MIB, and the internal standard 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine (IBMP) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) at a concentration of 100 mg L−1 in methanol, 1 mg L−1 mixed standard solutions of the two target compounds in methanol, and all of them were stored in the dark at 4°C. The details of the three compounds are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The CAS number, molecular weight, boiling point, and odor threshold of the three compounds.

| Compounds | CAS no. | Molecular weight | Boiling pointa (°C) | Odor threshold concentrationc (ng L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSM | 19700-21-1 | 182 | 270b/249 | 4 |

| 2-MIB | 2371-42-8 | 168 | 210 | 9 |

| IBMP | 24683-00-9 | 166 | 236 | 1 |

Deionized water was prepared on a water purification system (Gradient A10) supplied by Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Sodium chloride (analytical grade, China), which was added to the samples before extraction, was conditioned by heating at 450°C for 4 h before use. The SPME apparatus was purchased from Supelco (USA), including fiber 30/50 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS (no. 57348-U) [26, 29], fiber holder, 60 mL specialized vials for SPME, sampling stand, magnetic stirrer, and injection catheter (no. 57356-U).

2.2. SPME Procedures

The extraction conditions shown in Table 3 were followed. After putting NaCl and a stir bar in a 60 mL vial, 40 mL of mixed standard solutions (50 ng L−1) for orthogonal experiment, or 40 mL of environmental water samples, was added, and 2 μL IBMP (1 mg L−1) was added to every sample. The vial was sealed with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) septum cap and placed in a water bath. Several minutes after the temperature was achieved in the vial, the outer needle of fiber was used to penetrate the septum, and the fiber was exposed to the headspace for extraction. After exposure, the fiber was immediately inserted into the GC injection port for desorption.

Table 3.

The experimental design based on Taguchi's L32 (49) orthogonal array and the response of the peak area count by GC-MSa.

| Exp. no. and order | Factorsb | Responsesc (peak area ×107) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | 2-MIB | GSM | |

| 1 | 40 | 10 | 300 | 15 | 2 | 200 | 5 | 0.462 | 1.305 |

| 2 | 40 | 30 | 500 | 25 | 2 | 240 | 5 | 1.782 | 5.285 |

| 3 | 40 | 40 | 600 | 15 | 3 | 220 | 6 | 2.214 | 7.223 |

| 4 | 40 | 20 | 400 | 25 | 3 | 260 | 6 | 2.155 | 8.261 |

| 5 | 40 | 30 | 500 | 30 | 5 | 220 | 7 | 1.843 | 6.323 |

| 6 | 40 | 10 | 300 | 20 | 5 | 260 | 7 | 0.734 | 2.423 |

| 7 | 40 | 20 | 400 | 30 | 7 | 200 | 8 | 2.013 | 6.054 |

| 8 | 40 | 40 | 600 | 20 | 7 | 240 | 8 | 2.234 | 7.568 |

| 9 | 50 | 40 | 500 | 20 | 3 | 200 | 5 | 2.971 | 8.734 |

| 10 | 50 | 20 | 300 | 30 | 3 | 240 | 5 | 2.225 | 8.334 |

| 11 | 50 | 10 | 400 | 20 | 2 | 220 | 6 | 0.835 | 2.568 |

| 12 | 50 | 30 | 600 | 30 | 2 | 260 | 6 | 2.644 | 8.467 |

| 13 | 50 | 20 | 300 | 25 | 7 | 220 | 7 | 2.325 | 8.407 |

| 14 | 50 | 40 | 500 | 15 | 7 | 260 | 7 | 3.173 | 9.462 |

| 15 | 50 | 30 | 600 | 25 | 5 | 200 | 8 | 2.828 | 8.532 |

| 16 | 50 | 10 | 400 | 15 | 5 | 240 | 8 | 1.122 | 3.586 |

| 17 | 60 | 10 | 600 | 30 | 7 | 220 | 5 | 2.587 | 7.256 |

| 18 | 60 | 30 | 400 | 20 | 7 | 260 | 5 | 3.105 | 9.637 |

| 19 | 60 | 40 | 300 | 30 | 5 | 200 | 6 | 3.235 | 11.38 |

| 20 | 60 | 20 | 500 | 20 | 5 | 240 | 6 | 3.013 | 8.467 |

| 21 | 60 | 30 | 400 | 15 | 3 | 200 | 7 | 3.089 | 9.435 |

| 22 | 60 | 10 | 600 | 25 | 3 | 240 | 7 | 2.793 | 7.315 |

| 23 | 60 | 20 | 500 | 15 | 2 | 220 | 8 | 2.958 | 8.316 |

| 24 | 60 | 40 | 300 | 25 | 2 | 260 | 8 | 3.273 | 11.49 |

| 25 | 70 | 40 | 400 | 25 | 5 | 220 | 5 | 2.843 | 10.78 |

| 26 | 70 | 20 | 600 | 15 | 5 | 260 | 5 | 2.772 | 15.85 |

| 27 | 70 | 10 | 500 | 25 | 7 | 200 | 6 | 2.336 | 9.886 |

| 28 | 70 | 30 | 300 | 15 | 7 | 240 | 6 | 3.131 | 13.41 |

| 29 | 70 | 20 | 600 | 20 | 2 | 200 | 7 | 2.563 | 13.27 |

| 30 | 70 | 40 | 400 | 30 | 2 | 240 | 7 | 2.656 | 12.78 |

| 31 | 70 | 30 | 300 | 20 | 3 | 220 | 8 | 2.895 | 12.92 |

| 32 | 70 | 10 | 500 | 30 | 3 | 260 | 8 | 2.324 | 8.737 |

aIn this table, the error term was not listed. bFactor A: extraction temperature (°C); Factor B: extraction time (min); Factor C: rotate-speed (rpm); Factor D: ionic strength (w/v, %); Factor E: desorption time (min); Factor F: desorption temperature (°C); and Factor G: solution pH. cPeak area was calculated by quantitative ions under SIM mode, and area rejection: 10,000; initial threshold: 1; and peak width: 0.04.

2.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

A Varian 300 GC/MS/MS (Varian, Inc., CA, USA) with ion trap and mass spectrometer was obtained with a Varian VF-5 MS capillarity column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.5 μm). The temperature of the injector was 260°C adjusted to splitless mode. The carrier gas was helium at a flow of 1 mL min−1. The temperature of the oven started at 40°C and was held for 5 min. Then, the temperature was 8°C min−1 to achieve 160°C (total time: 20 min) followed by 20°C min−1 to achieve 260°C (total time: 25 min). The electron impact (EI) MS conditions were as follows: ion-source temperature: 230°C; MS transfer line temperature: 250°C; solvent delay time: 5 min; and ionizing voltage: 70 eV. The mass spectrogram in full-scan mode was obtained at the m/z range of 80–200 u. According to the MS scan function (SIM mode), the process was divided into three main segments as shown in Table 2. The method of internal standard was applied to construct the calibration curve and determine the concentrations of 2-MIB and GSM in water.

Table 2.

The parameters of the MS scan function (SIM mode) for the determination of analytes.

| Compounds | Retention time (min) | Segment (min) | Quantitative ions (m/z) | Secondary ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSM | 22.217 | 22.0–22.4 | 112 | 125 |

| 2-MIB | 18.663 | 18.4–19.0 | 107 | 95,135 |

| IBMP | 18.121 | 15.0–18.4 | 124 | 94,151 |

3. Results and Discussion

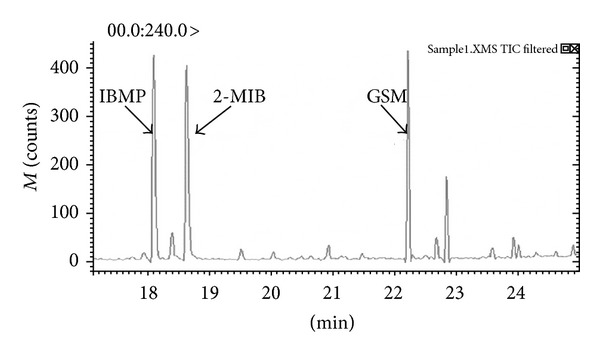

To obtain the qualitative and quantitative ions, the two target analytes and the internal standard compound were first identified simultaneously by HS-SPME/GC-MS in the scan mode. The selected ions and retention time (t R) are listed in Table 2. The chromatogram (full-scan mode) is shown in Figure 1, and the full-scan mass spectra from 17.0 to 24.3 min were obtained with m/z range of 80–200 u.

Figure 1.

To identify the two odors and the internal standard compound by HS-SPME.

3.1. Optimization of Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction and Desorption

In order to optimize the extraction of GSM and 2-MIB by HS-SPME, several parameters were investigated. The orthogonal design experiment is a valid approach by applying the orthogonal table Ln (m k) to arrange experiments. In the orthogonal table, n represents the number of experiments; m is the number of factor levels; and k is the number of factors. The multiple factors as well as the multiple levels can be dealt with by this design, and it also can obtain the optimal design with less experimental effort. And the experimental results can then be calculated by the analysis of variance, which can identify the main significant factors and levels. This method had been applied to optimize experimental conditions for determining the several phytohormones in natural coconut juice by Wu and Hu [31], and it has been used by Huang et al. [32] for the determination of glycol ethers it had been also extraction of fat-soluble vitamins by Sobhi et al. [33] and analysis of 17 organochlorine pesticides in water samples by Qiu and Cai [34]. In this study, utilized orthogonal experiment design L32 (49) was applied to arrange and optimize experiment conditions. The concrete experiments are listed in Table 3, and, all experiments were repeated twice, and then, the average peak area was applied to weigh the efficiency of HS-SPME under different conditions.

According to the analytical results calculated by SPSS 19.0 in Table 4, for the maximum for 2-MIB was K31, K42, K43, K34, K45, K46, and K47, and that for GSM was K41, K42, K43, K34, K45, K46, and K27. In other words, the optimum conditions for 2-MIB were listed as follows: temperatures of extraction and desorption: 60°C and 260°C, respectively; times of extraction and desorption: 40 min and 7 min, respectively; ionic strength: 30% (w/v); rotate-speed: 600 rpm; and solution pH: 8.0. And those for GSM were listed as follows: temperatures of extraction and desorption: 70°C and 260°C, respectively; times of extraction and desorption: 40 min and 7 min, respectively; ionic strength: 25% (w/v); rotate-speed: 600 rpm; and solution pH: 6.0.

Table 4.

The basic analytical results of the orthogonal experiment design L32 (49).

| Compounds (×107) | K value | Factorsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | ||

| 2-MIB | K1 | 13.437 | 13.193 | 18.280 | 18.921 | 17.173 | 19.497 | 18.747 |

| K2 | 18.123 | 20.024 | 17.818 | 18.350 | 20.666 | 18.500 | 19.563 | |

| K3 | 24.053 | 21.317 | 20.400 | 20.335 | 18.390 | 18.956 | 19.176 | |

| K4 | 21.520 | 22.599 | 20.635 | 19.527 | 20.904 | 20.180 | 19.647 | |

|

| ||||||||

| GSM | K1 | 44.442 | 43.076 | 69.669 | 68.587 | 63.481 | 68.596 | 67.181 |

| K2 | 58.090 | 76.959 | 63.101 | 65.587 | 70.959 | 63.793 | 69.662 | |

| K3 | 73.296 | 74.009 | 65.210 | 69.956 | 67.341 | 66.745 | 69.415 | |

| K4 | 97.633 | 79.417 | 75.481 | 69.331 | 71.680 | 74.327 | 67.203 | |

aFactor A: extraction temperature (°C); Factor B: extraction time (min); Factor C: rotate-speed (rpm); Factor D: ionic strength (w/v, %); Factor E: desorption time (min); Factor F: desorption temperature (°C); and Factor G: solution pH.

Table 5 shows the results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the significance of the main factors, which were based on the peak area of headspace in simulative water samples. As to 2-MIB, extraction temperature, extraction time, desorption time, and ionic strength were significant factors (P ≤ 0.01), while other factors did not have a significant effect (P ≥ 0.05) within the studied range. For the GSM, only extraction temperature and extraction time were significant factors (P ≤ 0.01), while others were not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

Table 5.

The analysis of the variance of the main factors on the respective peak area of headspace volatile odors in simulated water samples.

| Sourcea | 2-MIB | GSM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dfb | SUMc | MSd | F-value | Significant | df | SUM | MS | F-value | Significant | |

| A | 3 | 7.90979 | 2.63659 | 100.8 | ∗∗ | 3 | 194.85201 | 64.95067 | 56.1 | ∗∗ |

| B | 3 | 6.59627 | 2.19875 | 84.1 | ∗∗ | 3 | 108.42397 | 36.14132 | 31.2 | ∗∗ |

| C | 3 | 0.77847 | 0.25949 | 9.9 | ∗ | 3 | 11.25019 | 3.75006 | 3.2 | |

| D | 3 | 0.27097 | 0.09032 | 3.45 | 3 | 1.40387 | 0.46795 | 0.4 | ||

| E | 3 | 1.22373 | 0.40791 | 15.6 | ∗∗ | 3 | 5.32751 | 1.77583 | 1.5 | |

| F | 3 | 0.19630 | 0.06543 | 2.50 | 3 | 7.39079 | 2.46359 | 2.1 | ||

| G | 3 | 0.06370 | 0.02123 | 0.81 | 3 | 0.69210 | 0.23070 | 0.2 | ||

| Error | 10 | 0.26148 | 0.02614 | 10 | 11.56231 | 1.15623 | ||||

∗ and ∗∗: significant at P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively. aSource A: extraction temperature (°C); Source B: extraction time (min); Source C: rotate-speed (rpm); Source D: ionic strength (w/v, %); Source E: desorption time (min); Source F: desorption temperature (°C); and Source G: solution pH. bDegree of freedom; csum of square; and dmean of square.

3.2. Effects of Extraction Temperature, Extraction Time, Ionic Strength, and Desorption Time on Responses

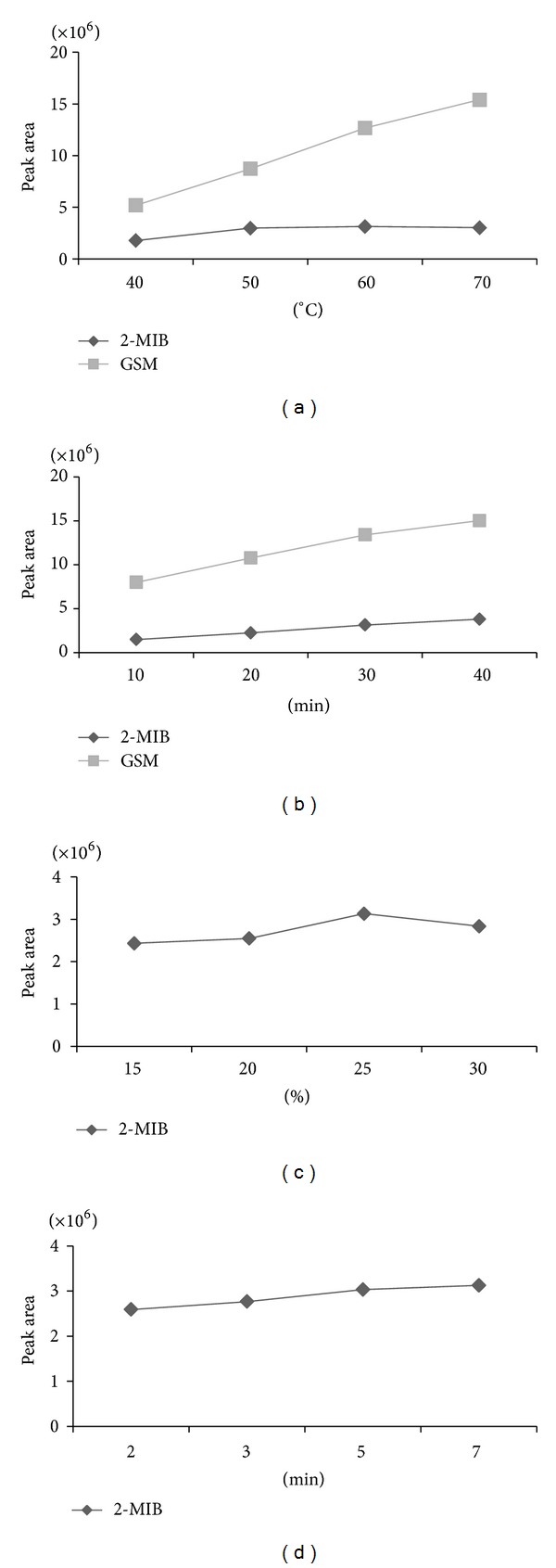

According to the results of ANOVA of the previous main factors, the significant factors were studied at 10 ng L−1 of mixed standard solutions by using the method of “one factor at a time.” Each of them was tested twice, and the results were obtained in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The effects of extraction temperature, extraction time, ionic strength, and desorption time on responses. (a) extraction temperature for GSM and 2-MIB; (b) extraction times for GSM and 2-MIB; (c) ionic strength for 2-MIB; and (d) desorption time for 2-MIB.

3.2.1. Effect of Extraction Temperature

Responses were calculated upon the conditions of 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C extraction temperatures (time of extraction and desorption: 30 min and 5 min, resp.; ionic strength: 25% (w/v); rotate-speed: 600 rpm; desorption temperature: 260°C; the solution pH: 5.0). As shown in Figure 2(a), we studied the SPME analyses run at the selected temperature, the extraction efficiency of the two analytes increased as the extraction temperature was, from 40°C to 60°C while a decrease was observed for 2-MIB and a slow increase was observed for GSM between 60°C and 70°C as reported similarly by Saito et al. [24]. The most likely reasons can be concluded as follows: firstly, as the extraction temperature was growing, the increasing amount of water vapor would be assembled on the fiber, which would lower the extraction efficiency; secondly, the different molecular weight of VOCs was known to be inconsistently susceptive to the extraction fiber [35]; thirdly, this can be explained by the partition coefficient between the fiber and the analytes. In other words, K fs = K 0exp[−ΔH/R(1/T − 1/T 0)] [36]; that is to say, the partition coefficient (K fs) would be altered if the extraction temperature was changed from T 0 to T, because the potential energy of the analyte on the coating material will be less than its potential energy in the sample if the K fs is more than one. Therefore, the value of K fs will decrease as the extraction temperature is increasing, which can result in the decreased extraction efficiency as reported by Chai and Pawliszyn [37]. When considering the extraction temperature, 65°C was the optimal choice as obtained in Figure 2(a).

3.2.2. Effect of Extraction Time

Responses were calculated upon the conditions of 10, 20, 30, and 40 min extraction temperature times (desorption time: 5 min; ionic strength, 25% (w/v); rotate-speed: 600 rpm; extraction and desorption temperatures: 65°C and 260°C, resp.; and solution pH: 5.0). As shown in Figure 2(b), we studied the SPME analyses run at the selected time; the extraction efficiency of the two analytes increased rapidly as extraction time was from 10 min to 30 min, while a slow increase was observed for both of them between 30 and 40 min. However, the equilibrium time for this fiber may be 40 min or more, but we desired shorter extraction time to maximize the sample. Therefore, the extraction time 30 min was selected for experiments, and also this allowed the GC-MS analysis (25 min) to be performed nearly in the approximate time as in the HS-SPME procedure.

3.2.3. Effect of Ionic Strength

The suitable salt addition could improve the transfer of analytes from the aqueous phase to the gaseous phase, so this can result in a higher concentration of the odors in the headspace. Responses were calculated upon the conditions of 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% (w/v) ionic strengths (times of extraction and desorptions: 30 min and 5 min, resp.; rotate-speeds: 600 rpm; extraction, and desorption temperatures: 65°C and 260°C, resp.; and solution pH: 5.0). As shown in Figure 2(c), it was fairly clear that 25% (w/v) was most suitable for the extraction process, and this concentration of salt was selected for the future experiments.

3.2.4. Effect of Desorption Time

As shown in Figure 2(d), the desorption time (2, 3, 5, and 7 min) profile is studied. The peak area of 2-MIB remained unchanged as desorption time after 5 min. In other words, 5 min was enough for desorption. Thus, 5 min was selected as the optimal time.

3.2.5. Effects of Other Factors

According to the results of the analysis of variance, some factors such as rotate-speed, desorption temperature, and solution pH did not have significant effects (P ≥ 0.05) within the given range. Consequently, 600 rpm, 260°C, and 5.0 were chosen, respectively, for rotate-speed, desorption temperature, and solution pH [24, 26].

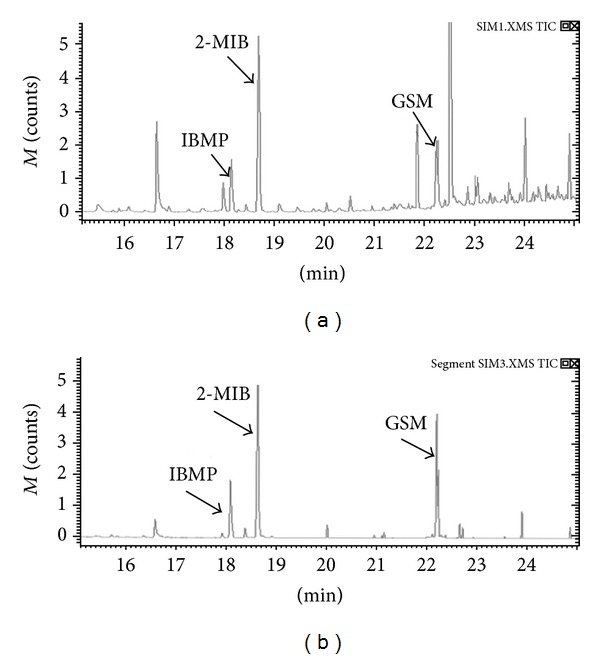

3.3. Optimization of Mass Spectrometry

The 10 ng L−1 spiked mixed standard solutions were detected by two methods later. As shown in Figure 3(b), the MS analysis progress in SIM mode was separated into five segments. To be more specific, segment 1 started from 15.0 min, selected ion m/z = 124, segment 2 from 18.4 min, m/z = 107, segment 3 from 19.0 min, nothing, segment 4 from 22.0 min, m/z = 112, and segment 5 from 22.4 min, nothing. In this case, the peaks can be separated effectively, and some disturbed peaks would be excluded. In contrast, as shown in Figure 3(a), it would result in some unidentified peaks by not using the segments to analyze the compounds. The signal to noise ratio (S/N) was shown in Table 6, and it was fairly clear that the MS scan function was more effective for the determination of analytes.

Figure 3.

The determination of analytes in SIM mode. (a) Not using segments for the determination of analytes in SIM mode. (b) The MS scan function (SIM mode) for the determination of analytes.

Table 6.

The comparison of the signal to noise ratio (S/N) by two methods.

| Compounds | Quantitative ion | Concentration (ng L−1) | S/N1 a | S/N2 b | (S/N1)/(S/N2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBMP | 124 | 10 | 6899 | 1731 | 3.98 |

| 2-MIB | 107 | 10 | 2046 | 906 | 2.26 |

| GSM | 112 | 10 | 737 | 144 | 6.46 |

aS/N1 was obtained by not using segments in SIM mode. bS/N2 was obtained by the MS scan function in SIM mode.

3.4. Method Validation

The proposed HS-SPME/GC-MS method had been validated in terms of accuracy, linearity, limits of detection, relative standard deviation (RSD), and recovery.

3.4.1. Calibration Curves, Limits of Detection, and RSDs

Linearity was studied by extracting the two odors in mixed standard solutions at five levels, ranging from 5 to 100 ng L−1. Calculated calibration curves gave high levels of linearity with a correlation coefficient value of 0.9999 for both of geosmin and 2-MIB, and the RSDs were 2.75%~3.80% and 4.35%~7.6% for GSM and 2-MIB, respectively. Under the optimized experimental conditions, limits of detection (S/N = 3) and limits of quantitation (S/N = 10) for geosmin were 0.04 and 0.14 ng L−1, and those for 2-MIB were 0.13 and 0.42 ng L−1, respectively (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 7.

The calibration curves and limits of detection for 2-MIB and GSM.

| Compounds | Calibration curves | Correlation coefficients (R) | LOD (ng L−1) | LOQ (ng L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-MIB | 0.9999 | 0.13 | 0.4 | |

| GSM | 0.9999 | 0.04 | 0.2 |

Table 8.

The relative standard deviations (RSDs)a for 2-MIB and GSM.

| Exp. no.b | 2-MIB | GSM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 ng L−1 | 100 ng L−1 | 20 ng L−1 | 100 ng L−1 | |

| 1 | 24.2 | 93.8 | 19.3 | 102.1 |

| 2 | 24.3 | 90.1 | 20.5 | 100.7 |

| 3 | 23.2 | 102.0 | 20.6 | 102.1 |

| 4 | 22.6 | 95.1 | 21.9 | 100.6 |

| 5 | 22.1 | 94.0 | 20.6 | 106.7 |

| 6 | 20.2 | 91.0 | 20.4 | 105.7 |

| 7 | 20.2 | 91.2 | 19.8 | 107.2 |

| RSD (%)a | 7.6 | 4.35 | 3.8 | 2.75 |

aUsing IBMP as the internal standard. Compound concentration: 10 ng L−1. bSpiked de-ionized water sample.

3.4.2. Test on Environmental Samples

Tap water, deionized water, and lake water were used to verify the applicability of this method for the analysis of these two odors in water samples. As shown in Table 9, the high recoveries were obtained. This fairly indicated that the proposed method could be used to analyze these musty and earthy odors in water samples.

Table 9.

The recovery of environmental samples.

| Compounds | Samples | Concentration | Test results of spiked samples (ng L−1) | Recovery (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng L−1) | 20 ng L−1 | 100 ng L−1 | 20 ng L−1 | 100 ng L−1 | ||

| 2-MIB | Deionized water | <0.2 | 20.8 | 92.0 | 104 | 92.0 |

| Tap water | 1.8 | 23.9 | 95.3 | 110 | 93.5 | |

| Lake water | 2.9 | 23.6 | 94.0 | 103 | 91.1 | |

|

| ||||||

| GSM | Deionized water | <0.4 | 21.4 | 103.7 | 107 | 104 |

| Tap water | 1.9 | 20.1 | 101.6 | 90.8 | 99.7 | |

| Lake water | 2.6 | 22.1 | 104.8 | 97.3 | 102 | |

4. Conclusion

This study has demonstrated the application of the orthogonal experiment design for screening the significant factors of HS-SPME for the analysis of volatile organic compounds in water samples. Also, the MS scan function was an effective approach for the determination of analytes. The proposed method has been validated by excellent results (i.e., high sensitivity, low limits of detections, and high levels of linearity). Therefore, this method would be most likely to be applied to optimize factors for future study for analysis of some other odors in water (i.e., 2-isopropyl-3-methoxy pyrazine and 2,4,6-trichloroanisole).

Authors' Contribution

Shifu Peng and Zhen Ding contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

This study was jointly supported by Science and Technology Supporting Project of Jiangsu Province, China (BE2011797), Project for Medical Research by Jiangsu Provincial Health Department (H201024), Medical Innovation Team and Academic Pacemaker of Jiangsu Province (LJ201129), and Specialized Project for Scientific Research from Ministry of Health and Public Welfare (201002001).

References

- 1.Mackey ED, Baribeau H, Crozes GF, Suffet IH, Piriou P. Public thresholds for chlorinous flavors in U.S. tap water. Water Science and Technology. 2004;49(9):335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freuze I, Brosillon S, Herman D, Laplanche A, Démocrate C, Cavard J. Odorous products of the chlorination of phenylalanine in water: formation, evolution, and quantification. Environmental Science and Technology. 2004;38(15):4134–4139. doi: 10.1021/es035021i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izaguirre G, Wolfe RL, Means EG. Degradation of 2-methylisoborneol by aquatic bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;54:2424–2431. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.10.2424-2431.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies J-M, Roxborough M, Mazumder A. Origins and implications of drinking water odours in lakes and reservoirs of British Columbia, Canada. Water Research. 2004;38(7):1900–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes KP, Burch MD. Odorous compounds associated with algal blooms in South Australian waters. Water Research. 1989;23(1):115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salemi A, Lacorte S, Bagheri H, Barceló D. Automated trace determination of earthy-musty odorous compounds in water samples by on-line purge-and-trap-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2006;1136(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson SB, Ridal J, Zaitlin B, Lo A. Odours from pulp mill effluent treatment ponds: the origin of significant levels of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol (MIB) Chemosphere. 2003;51(8):765–773. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uwins HK, Teasdale P, Stratton H. A case study investigating the occurrence of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol (MIB) in the surface waters of the Hinze Dam, Gold Coast, Australia. Water Science and Technology. 2007;55(5):231–238. doi: 10.2166/wst.2007.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benanou D, Acobas F, Deroubin MR, David F, Sandra P. Analysis of off-flavors in the aquatic environment by stir bar sorptive extraction-thermal desorption-capillary GC/MS/olfactometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2003;376(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-1868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallevialle J. Identification and Treatment of Tastes and Odors in Drinking Water. chapter 5. Denver, Colo, USA: American Water Works Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitjans D, Ventura F. Determination of fragrances at ng/L levels using CLSA and GC/MS detection. Water Science and Technology. 2005;52(10-11):145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng X, Liang G, Chen J, Qi M, Xie P. Simultaneous determination of eight common odors in natural water body using automatic purge and trap coupled to gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2011;1218(24):3791–3798. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo T, Zhou Z, Lin S. Determination of volatile organic compounds in drinking water by purge and trap gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2006;35(4):504–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu HW, Liu YT, Wu BZ. Process sampling module coupled with purge and trap-GC-FID for in situ auto-monitoring of volatile organic compounds in wastewater. Talanta. 2009;80:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortada C, Vidal L, Canals A. Determination of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in water and wine samples by ultrasound-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2011;1218(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madrera RR, Valles BS. Determination of volatile compounds in apple pomace by stir bar sorptive extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (SBSE-GC-MS) Journal of Food Science. 2011;76(9):C1326–C1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casas Ferreira AM, Möder M, Fernández Laespada ME. GC-MS determination of parabens, triclosan and methyl triclosan in water by in situ derivatisation and stir-bar sorptive extraction. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;399(2):945–953. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossi P, Olivares IRB, de Freitas DR, Lancas FM. A novel HS-SBSE system coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry for the analysis of organochlorine pesticides in water samples. Journal of separation science. 2008;31(20):3630–3637. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B, Wang W, Huang Y. Cigarette filters as adsorbents of solid-phase extraction for determination of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in environmental water samples coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography. Talanta. 2012;88:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López R, Aznar M, Cacho J, Ferreira V. Determination of minor and trace volatile compounds in wine by solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography with mass spectrometric detection. Journal of Chromatography A. 2002;966(1-2):167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)00696-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capriotti AL, Cavaliere C, Giansanti P, Gubbiotti R, Samperi R, Laganà A. Recent developments in matrix solid-phase dispersion extraction. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217(16):2521–2532. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arthur CL, Pawliszyn J. Solid-phase microextraction with thermal-desorption using fused-silica optical fibers. Analytical Chemistry. 1990;62:2145–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang FF, Yu JW, Yang M. Determination of dimethyl trisulfide in water by headspace solid-phase micro-extraction coupled with gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. China Water and Waste Water. 2009;25:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito K, Okamura K, Kataoka H. Determination of musty odorants, 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin, in environmental water by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2008;1186(1-2):434–437. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura S, Daishima S. Simultaneous determination of 22 volatile organic compounds, methyl-tert-butyl ether, 1,4-dioxane, 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin in water by headspace solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2005;548(1-2):79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung Y, Li T, Huang S. Analysis of earthy and musty odors in water samples by solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography/ion trap mass spectrometry. Talanta. 2005;65(2):518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd SW, Lea JM, Zimba PV, Grimm CC. Rapid analysis of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in water using solid phase micro extraction procedures. Water Research. 1998;32(7):2140–2146. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morales-Valle H, Silva LC, Paterson RRM, Oliveira JM, Venâncio A, Lima N. Microextraction and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry for improved analysis of geosmin and other fungal “off” volatiles in grape juice. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2010;83(1):48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen KY, Yu JW, Sun DL. Analysis of odor compounds in water samples by Headspace Solidphase Microextraction Coupled with GC/MS. China Water and Wastewater. 2011;27:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young WF, Horth H, Crane R, Ogden T, Arnott M. Taste and odour threshold concentrations of potential potable water contaminants. Water Research. 1996;30(2):331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, Hu B. Simultaneous determination of several phytohormones in natural coconut juice by hollow fiber-based liquid-liquid-liquid microextraction-high performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A. 2009;1216(45):7657–7663. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang C, Su Y, Hsieh Y. Optimization of the headspace solid-phase microextraction for determination of glycol ethers by orthogonal array designs. Journal of Chromatography A. 2002;977(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobhi HR, Yamini Y, Esrafili A, Abadi RHHB. Suitable conditions for liquid-phase microextraction using solidification of a floating drop for extraction of fat-soluble vitamins established using an orthogonal array experimental design. Journal of Chromatography A. 2008;1196-1197(1-2):28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu C, Cai M. Ultra trace analysis of 17 organochlorine pesticides in water samples from the Arctic based on the combination of solid-phase extraction and headspace solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-electron-capture detector. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217(8):1191–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray RA. Limitations to the use of solid-phase microextraction for quantitation of mixtures of volatile organic sulfur compounds. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73(7):1646–1649. doi: 10.1021/ac001176m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pawliszyn J. Principle and Application of Solid Phase Microextraction. Beijing, China: Chemical; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chai M, Pawliszyn J. Analysis of environmental air samples by solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography/ion trap mass spectrometry. Environmental Science and Technology. 1995;29(3):693–701. doi: 10.1021/es00003a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]