Abstract

The present study examined whether combinations of ethnicity, gender and age moderated the association between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being indicators (depressive symptoms, self-esteem and life satisfaction) in a nationally representative sample of Black youth. The data were from the National Survey of African Life (NSAL), which includes 810 African American and 360 Caribbean Black adolescents. The results indicated main effects such that perceived discrimination was linked to increased depressive symptoms, and decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction. Additionally, there were significant interactions for ethnicity, gender and race. Specifically, older Caribbean Black females exhibited higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction in the context of high levels of perceived discrimination compared to older African American males.

Keywords: African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, Adolescents, Perceived Discrimination, Psychological Well-being

The purpose of the present study is to assess whether demographic constructs (i.e., ethnic, gender and age) moderate the relationship between perceptions of discrimination and psychological well-being among Black youth. This is consistent with an intersectionality approach, which examines the ways in which various socially constructed categories interact on multiple levels that result in perceptions of unequal treatment (Andersen & Collins, 2009). A primary assumption of the intersectional approach is that specific types of discrimination are related such that discrimination may be based on the “intersection” of multiple social categories such as race, ethnicity and gender (Andersen & Collins, 2009). Examining differences in perceived discrimination (i.e., ethnic, gender and age) is comparative with an assessment of which Black youth perceive more or less discriminatory incidents, whereas the intersectional approach addresses whether there are subgroups of Black youth for whom perceived discrimination is more harmful. The difference approach cannot examine whether some youth are more affected by discriminatory treatment than their counterparts, whereas the intersectional approach assesses whether the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being varies for some Black youth.

The intersectional approach is critical for understanding which subgroups may be more affected by discriminatory treatment, given the growing research showing that discrimination is negatively linked to health (see Williams & Mohammed, 2009 for a review). For example, previous research indicates that older youth perceive more discrimination than their younger counterparts (Fisher, Wallace & Fenton, 2000), but it is unclear if perceived discrimination is more negatively linked to the well-being of older youth compared to younger youth. The current study is preliminary in assessing how and why the intersection of ethnicity, gender and age result in qualitatively different reactions to discriminatory treatment.

We suggest that the intersection of ethnicity, gender and age should moderate perceptions of discrimination and there is a small body of research suggesting why these might be key moderators. Ethnicity is important given the historical and cultural differences between African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. In the Caribbean, an African-descended racial majority was created, resulting in Caribbean Blacks minimizing the expectation that racial discrimination will be a significant barrier to their upward mobility (Vickerman, 2001). Alternatively, the normative experience for African Americans is being in the racial minority and encountering legalized racial discrimination and harassment (Rogers, 2001). As such, African American parents engage in racial socialization, which consists of the mechanisms through which parents transmit information, values and perspectives about race and ethnicity to their children (Hughes et al., 2006). Consequently, Caribbean Black youth may have diminished awareness and expectations of encountering racial discrimination, whereas African American youth may be prepared for discriminatory treatment when it occurs. Prior research suggests that Caribbean Black youth exhibited higher depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem in the context of high levels of perceived discrimination compared to their African American counterparts (Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers & Jackson, 2008).

Theoretical work suggests that gender is important because discrimination is practiced against males as opposed to females, to reduce the competition for power among dominant and subordinate males, and that Black males may be perceived as more threatening resulting in Black adolescent males being targeted more than their female counterparts (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Prior work also suggests that African American males expect to have negative experiences such that discriminatory treatment may be “normative” or part of their everyday experiences (Swanson, Cunningham & Spencer, 2003). Consequently, the relationship between perceptions of racial discrimination and behavioral problems was stronger for rural African American males compared to rural African American females (Brody et al., 2006). Similarly, Caribbean Black males may be targeted for discriminatory treatment as consistent with theoretical work (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Caribbean Black females might also be adversely affected by discriminatory experiences given some cultural beliefs that women are responsible for familial upward mobility via mechanisms such as advanced education (Gregory, 2006). These beliefs may be negatively affected by perceptions of discrimination for Caribbean Black females given the different experiences with race in American society compared to their origin countries.

Age may be an important construct because of the cognitive changes occurring during the adolescent period. Formal reasoning, which is the ability to logically examine one’s thoughts as well as the thoughts of others, develops during adolescence and is more likely to be evident among older adolescents (Keating, 2004). Harrell (2000) argued that racial discrimination is complex requiring cognitive sophistication, such that older youth with abstract thinking may be more affected than their younger counterparts. Noh, Kaspar and Wickrama (2007) examined discrimination and cognitive appraisal strategies (i.e., feelings of exclusion, discouragement and shame) among Korean children. The results indicated that cognitive strategies partially mediated the relationship between perceptions of subtle discrimination and depressive symptoms such that greater use of those specific cognitive strategies was linked to increased depressive symptoms (Noh et al., 2007). Thus, cognitions about discriminatory experiences were important in the relationship between discrimination and mental health. Additionally, racial/ethnic identity is developing during this period resulting in increased exploration of racial issues for minority youth such that older African American adolescents, compared to early adolescents, were more likely to have achieved or fully developed racial identities (Seaton, Scottham & Sellers, 2006). While we are not suggesting that age is a proxy for cognitive development and/or identity development, these changes may be two reasons why older minority youth might respond differently to discriminatory experiences compared to their younger counterparts.

The present study assesses the intersection of ethnicity, gender and age as moderators of perceived discrimination and psychological well-being, whereas previous research has focused on one characteristic (i.e., ethnicity or gender) as a moderator. The primary strength of the current study is the examination of combinations of ethnicity, gender and age as moderators for perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among Black youth. Since prior research indicates that African American males (compared to African American females) and Caribbean Black youth (compared to African American youth) were more affected by discriminatory treatment (Brody et al., 2006; Seaton et al., 2008), we anticipate that these relationships might be more complex when age is also considered. For example, the relationship between perceptions of discrimination and psychological well-being may be stronger for older African American males, older Caribbean Black males and older Caribbean Black females compared to their younger counterparts.

Method

Participants

The participants were African American and Caribbean Black youth who participated in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) (Jackson et al., 2004). The sample consists of 1170 African American (n=810) and Caribbean Black (n=360) youth ranging in age from 13 to 17 who were attached to the adult households. The overall sample was equally composed of males (N=563) and females (N=605), and there was an equal gender distribution for African American youth with slightly more females than males among Caribbean Black youth. The mean age was 15 (SD = 1.42), and the age groups were categorized as follows: early (age 13–14; N=477), middle (age 15–16; N=441), and late (age 17; N=252). Approximately, 4% of the Caribbean sample was not born in the United States, 96% of the sample was still enrolled in high school and 9th grade was the average. The median family income, as reported by the adult respondent, was $28,000 (approximately $26,000 for African Americans and approximately $32,250 for Caribbean Blacks) and household income ranged from 0 to $520,000.

Procedure

A national probability sample of households was drawn based on adult population estimates and power calculations for detecting differences among the adult samples. The specific sampling procedures for identification and recruitment of African American and Caribbean Black households have been described elsewhere (see Heeringa et al., 2004; Seaton et al., 2008). The adolescent supplement was weighted to adjust for non-independence in selection probabilities and non-response rates within households, across households and individuals. The weighted data were post-stratified to approximate the national population distributions for gender and age subgroups among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Informed consent was obtained from the adolescent’s legal guardian as well as adolescent assent. Most of the interviews were conducted in homes using a computer-assisted instrument, but 18% were conducted entirely or partially by telephone. Respondents were paid $50 for their participation, and the overall response rate was 81%.

Measures

Demographic questions

Adolescent gender, age and ethnicity were assessed with standard questions as part of the randomized respondent selection process used in the household sampling procedure for the study.

Everyday Discrimination Scale

The Everyday Discrimination Scale assesses chronic, routine and less overt experiences of discrimination that have occurred in the prior year (Williams, Yu, Jackson & Anderson, 1997). The original measure included ten items, but three items were added to reflect perceptions of teacher discrimination, resulting in a 13-item scale. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on random half samples and the results indicated a one-factor structure (Eigenvalue = 4.97), which is consistent with results from adult samples (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman & Barbeau, 2005; Williams et al., 1997). The stem question is: “In your day-to-day, life how often have any of the following things happened to you?” A sample item includes: “You are followed around in stores.” The Likert response scale (α = .86) ranges from 1 (never) to 6 (almost everyday). The responses were coded to indicate whether an event occurred versus an event never occurring, and higher scores indicate a greater number of events that occurred in the previous year.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale

The shortened 12-item version of the CES-D assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced within the past week (Radloff, 1977). This version has demonstrated reliability and validity among minority adolescent populations (see Roberts et al., 1999). The Likert scale (α = .68) consists of responses ranging from 0 (rarely) to 3 (most or all of the time). A sample item includes “I did not feel like eating, my appetite was poor”, and mean scores were used in the analyses.

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-esteem scale is an assessment of self-acceptance (Rosenberg, 1965). The 10-item Likert scale (α = .72) consists of rating items with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A sample item includes “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”, and mean scores were used in the analyses.

General Life Satisfaction

One question was used to assess adolescent perceptions of general life satisfaction (Campbell, 1976). The item read “How satisfied with your life as a whole would you say you are these days?” The responses ranged from 1 (very satisfied) to 4 (very dissatisfied). The item was reversed so that high scores indicate higher levels of life satisfaction.

Data Analytic Strategy

STATA 10 was used to conduct analyses in the present study. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to assess whether the relationship between perceived discrimination and the psychological well-being indicators (depressive symptoms, self-esteem and life satisfaction) varied across combinations of ethnicity, gender and age. All the variables were centered, and tests were run to examine variance inflation factors (VIF), which are indicators of multicollinearity. The model VIF estimates were within the recommended ranges (less than 10) for depressive symptoms (VIF = 3.29), self-esteem (VIF = 3.29) and life satisfaction (VIF = 3.32). African American males were utilized as the reference group. The initial model examined the main effects of the control variables and key predictors as a block in the following order: 1) African American females, 2) Caribbean Black males, 3) Caribbean Black females, 4) age, 5) household income and 6) perceived discrimination. The second model added the interaction terms as a block in the following order: 1) African American females x age, 2) Caribbean Black males x age, 3) Caribbean Black females x age, 4) African American females x perceived discrimination, 5) Caribbean Black males x perceived discrimination, 6) Caribbean Black females x perceived discrimination, 7) Age x perceived discrimination, 8) African American females x age x perceived discrimination, 9) Caribbean Black males x age x perceived discrimination and 10) Caribbean Black females x age x perceived discrimination. Significant interactions were examined to determine if 1) they significantly differed from zero via the coefficient t test and 2) if they significantly differed from each other by graphing them at different levels of the predictor variable.

Results

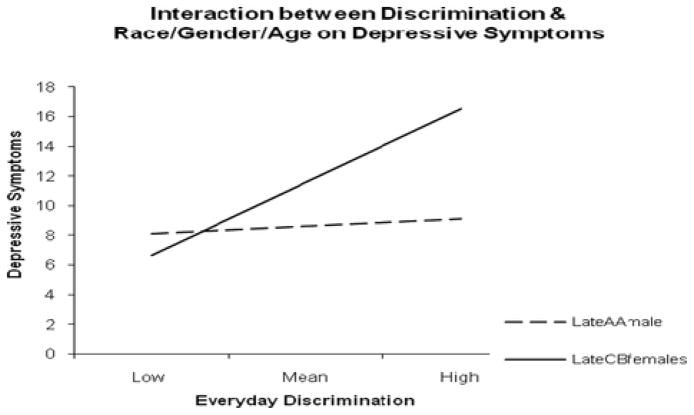

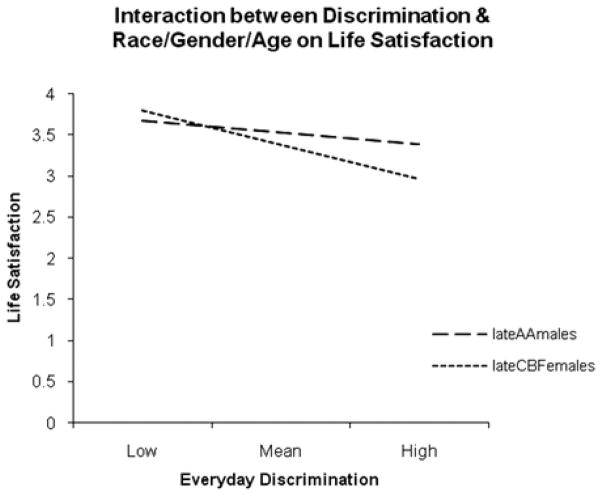

The study correlations suggest that gender was significant in that males perceived more discrimination and had lower life satisfaction levels (see Table 1). Age was also significant in that older adolescents perceived more discrimination and had lower life satisfaction levels. Perceptions of discrimination were linked to depressive symptoms, self-esteem and life satisfaction. Depressive symptoms were also negatively linked to self-esteem and life satisfaction, and self-esteem and life satisfaction was positively associated. A main effect was evident such that perceived discrimination was linked to higher depressive symptoms (see Table 2). The results also indicate two significant two-way interactions, African American x age and Caribbean Black x age, and one significant three-way interaction, Caribbean Black females x age x perceived discrimination. The two-way interactions indicate that older African American females and older Caribbean Black females reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than older African American males. The 3-way interaction was graphed at the following intervals: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean and one standard deviation above the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). An online program was used to calculate simple intercepts, simple slopes and the region of significance, as well as plot the significant interactions (see Preacher, Curran & Bauer, 2006). The results indicate that older Caribbean Black females reported higher levels of depressive symptoms in the context of high perceived discrimination levels compared to older African American males (see Figure 1). The results for self-esteem indicated that perceived discrimination was negatively linked to self-esteem and the 2-way interaction suggested that Caribbean Black females reported lower self-esteem levels than African American males when perceiving high levels of discrimination. Lastly, perceived discrimination was negatively linked to life satisfaction (see Table 4). There was a main effect such that African American females had lower life satisfaction levels than African American males, and older youth had lower life satisfaction levels than their younger counterparts. The 3-way interaction was graphed and indicated that older Caribbean Black females reported lower levels of life satisfaction than older African American males in the context of high discrimination levels (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for the Study Variables

| Variable | Race | Gender | Age | Household Income | Perceived Discrimination | Depressive Symptoms | Self-esteem | Life Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racea | ___ | |||||||

| Genderb | 0.03 | ___ | ||||||

| Age | 0.03 | −0.00 | ___ | |||||

| Household Income | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 | ___ | ||||

| Perceived Discrimination | −0.03 | −0.09* | 0.13** | 0.05 | ___ | |||

| Depressive Symptoms | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.12** | ___ | ||

| Self-esteem | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09** | −0.16** | −0.52** | ____ | |

| Life Satisfaction | 0.02 | −0.08* | −0.14** | 0.02 | −0.22** | −0.32** | 0.33** | ___ |

| M | ___ | ___ | 15 | 81,203 | 5.13 | 9.06 | 3.56 | 3.48 |

| SE | ___ | ___ | .06 | 2219 | .20 | .22 | .02 | .03 |

n. 1 = African American, 2 = Caribbean Black.

n. 1 = Male, 2 = Female.

p<. 05,

p<. .01.

Table 2.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Perceived Discrimination

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | se | B | se | |

| African American Females | −.00 | .04 | .30 | .45 |

| Caribbean Black Males | −.03 | .04 | −1.21 | 1.1 |

| Caribbean Black Females | .02 | .03 | −.76 | 1.01 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | −.09 | .19 |

| Household Income | .00 | .00 | −.00 | .00 |

| Perceived Discrimination | −.02** | .00 | .11* | .08 |

| African American Females x Age | .46* | .22 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age | .20 | .52 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age | 1.15* | .55 | ||

| African American Females x Perceived Discrimination | .11 | .10 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Perceived Discrimination | .22 | .13 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Perceived Discrimination | .36 | .20 | ||

| Age x Perceived Discrimination | .02 | .04 | ||

| African American Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | −.08 | .06 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age x Perceived Discrimination | −.12 | .09 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | .19* | .09 | ||

Note. R2 = .02 for Model 1; ΔR2 = .02 for Model 2 (p < .01).

p < .05,

p < .01.

Figure 1.

The Relationship between Perceived Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms.

Table 4.

Life Satisfaction Regressed on Perceived Discrimination

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | se | B | se | |

| African American Females | −.12** | .05 | −.12** | .05 |

| Caribbean Black Males | .04 | .13 | .05 | .12 |

| Caribbean Black Females | −.00 | .05 | −.01 | .05 |

| Age | −.05** | .02 | −.03 | .03 |

| Household Income | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Perceived Discrimination | −.04** | .01 | −.03** | .01 |

| African American Females x Age | −.04 | .04 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age | .00 | .05 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age | −.02 | .04 | ||

| African American Females x Perceived Discrimination | −.01 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Perceived Discrimination | .00 | .02 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Perceived Discrimination | −.04** | .01 | ||

| Age x Perceived Discrimination | .00 | .00 | ||

| African American Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | −.01 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age x Perceived Discrimination | .01 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | −.04** | .01 | ||

Note. R2 = .07 for Model 1; ΔR2 = .01 for Model 2 (p < .01).

p < .05,

p < .01.

Figure 2.

The Relationship between Perceived Discrimination and Life Satisfaction.

Discussion

The present study used an intersectional approach to examine whether the relation between perceptions of discrimination and psychological well-being varied among subgroups of youth based on the intersection of ethnicity, gender and age. The results suggest that one subgroup may be more affected than other subgroups of Black youth, which is an important and significant contribution to the adolescent literature on discrimination. The association between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being is stronger such that older Caribbean Black females have higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction when they perceive high levels of discrimination compared to older African American males. We suggest that rumination may be influencing the finding regarding older Caribbean Black females. Older adolescents are more likely to have formal reasoning and an enhanced ability to think abstractly about discriminatory experiences. The relationship may differ because females are more likely to ruminate over events than males (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2006). This rumination might explain why perceptions of discrimination are linked to depressive symptoms for late, Caribbean Black females especially since rumination is a concept that has been linked to gender differences in depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2006). Another explanation may be developing racial identity among older Caribbean Black females. Older youth are more likely to have advanced racial identities (Yip et al., 2006), and previous research indicates that racial identity attitudes influenced perceptions of racial discrimination among a sample of Caribbean Blacks (Hall & Carter, 2006). Prior research also indicates that Caribbean Black females have more developed identities in that they are able to claim a racial identity, maintain a stance of racial solidarity and are able to be bicultural compared to their male counterparts (Waters, 1996). Hence, the relationship between perceptions of discrimination, self-esteem and life satisfaction might be stronger for older Caribbean Black females because of their more crystallized racial identities during late adolescence. Lastly, older Caribbean Black females may be an at-risk group. Previous research suggests that Caribbean Black females, aged 16 to 18, were more likely to engage in risky behaviors (i.e., substance use, gang involvement and early sexual initiation) than their younger counterparts (aged 10 to 15) (Ohene, Ireland & Blum, 2005). Caribbean Black females in the later stages of adolescence may already have diminished psychological well-being, which may be especially true since late Caribbean Black females had the highest levels of depressive symptoms among the other subgroups.

We expected that the association between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being would be stronger for late African American, late Caribbean Black males and late Caribbean Black females in comparison to all other subgroups. Although we find this to be true for late Caribbean Black females, this was not the case for late Caribbean Black males who were equivalent to late African American males. Though prior research suggests that Black males perceive more incidents of discrimination than their female counterparts (Seaton et al., 2008), the psychological well-being of Black males appears to be unrelated to discriminatory experiences in the current study. This finding is contrary to previous research which has shown a robust link between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being for males and females of color. One explanation for this finding concerns the type of discrimination assessed, daily hassles, but other types of racial stressors include major discriminatory life events and chronic racial stressors (Harrell, 2000). A significant adolescent life event such as being charged with a juvenile crime or expelled from school and perceiving these to be the result of race/ethnicity might be negatively related to psychological well-being for older, Black males, as has been demonstrated with Black adults (Krieger et al., 2005). Thus, daily racial incidents might not be linked to the psychological well-being of older, African American and Caribbean Black males in the same way as they seem to be for older Caribbean Black females. Another reason for the lack of significant findings concerns the “normative” experiences of discrimination, which may be especially true for Black males since previous research suggests that discrimination is part of the “lived experiences” for urban, African American males (Stevenson, Herrero-Taylor, Cameron & Davis, 2002). Previous research assessing gender differences suggests that Black males perceive more discrimination than their female counterparts (Seaton el al., 2008), yet we find that African American and Caribbean Black males appear unaffected by discriminatory experiences. Though one might assume that males might be more affected by discriminatory experiences because they experience more, the present results do not support this notion. We suggest that longitudinal research using the intersectional approach is necessary to disentangle the mechanisms by which discrimination is linked to various psychological well-being outcomes to determine which subgroup among Black youth is more adversely affected by perceptions of discriminatory treatment.

One of the key findings from this study is the idea that the relationship between perceptions of discrimination and psychological well-being varies for distinct subgroups of Black youth. The present findings suggest that the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being depends on the specific subgroup and the specific indicator since perceptions of discrimination were not linked to the psychological well-being for all adolescent subgroups, but older Caribbean Black females. Future research should consider class, the role of historical context and family socialization goals when trying to understand the specific relations between stressors, moderators and outcome variables, and diverse outcome variables among Black youth. Additionally, one implication from the present study is that prevention and intervention efforts may need to be altered for specific subgroups of Black youth who may be more vulnerable to experiences of discrimination.

There are several limitations in the present study that require consideration. Initially, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents causality from being inferred such that we cannot articulate that perceptions of discrimination predict subsequent psychological well-being. One limitation concerns the fact that the models accounted for a limited amount of variance, as indicative of the small effect size estimates (R2) compared to prior empirical research. Previous research examining perceptions of discrimination among African American youth have shown medium to large effect sizes with depressive symptoms (Sellers, Linder, Martin & Lewis, 2006), self-esteem (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes & Rowley, 2007) and life satisfaction (Tynes, Giang, Williams & Thompson, 2008). While it is apparent that the effect sizes in the current study are smaller than prior empirical research, they may be appropriate estimates of these relationships since the interval of effect size is unknown though comprehensive reviews have indicated a robust relationship between perceived discrimination and various outcomes (see Williams & Mohammed, 2009). An additional limitation concerns the measurement of perceived discrimination, which utilizes an annual time period, when smaller time periods might capture discriminatory experiences more precisely. Another limitation concerns the notion that the measure makes no inherent racial attribution assumptions in the stem or with individual questions; discrimination may be considered a developmental in addition to a racial phenomenon for adolescents. Similarly, some of the reliability scores may be considered “low” in comparison to other studies using the same measures. Yet, standardized measures were used with a nationally representative sample of Black youth and previous research has shown that the CES-D is not psychometrically equivalent across racial or ethnic groups (Perreira, Deeb-Sossa, Harris & Bollen, 2005). Despite these limitations, the major contribution of the present study is that some subgroups of Black youth are more vulnerable to discriminatory treatment and this information is critical for intervention purposes.

The results of the present study enhance existing empirical and theoretical literature examining adolescent perceptions of discrimination among Black youth. Though previous research has illustrated demographic differences in perceptions of discrimination, use of the intersectional approach demonstrates that the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being appears stronger for older Caribbean Black females compared to older, African American males. Although the results support empirical research suggesting that discrimination is a stressor for minority youth during adolescence, not all Black youth appear equally affected by perceptions of discrimination.

Table 3.

Self-esteem Regressed on Perceived Discrimination

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | se | B | se | |

| African American Females | −.00 | .04 | −.00 | .04 |

| Caribbean Black Males | −.03 | .04 | −.03 | .05 |

| Caribbean Black Females | .02 | .03 | .02 | .04 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .02 | .01 |

| Household Income | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Perceived Discrimination | −.02** | .00 | −.02** | .00 |

| African American Females x Age | −.02 | .02 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age | −.01 | .04 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age | −.02 | .02 | ||

| African American Females x Perceived Discrimination | −.01 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Perceived Discrimination | −.00 | .04 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Perceived Discrimination | −.02* | .01 | ||

| Age x Perceived Discrimination | .00 | .00 | ||

| African American Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | .00 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Males x Age x Perceived Discrimination | .00 | .01 | ||

| Caribbean Black Females x Age x Perceived Discrimination | −.01 | .01 | ||

Note. R2 = .04 for Model 1; ΔR2 = .001 for Model 2 (p < .05).

p < .05,

p < .01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/dev

Contributor Information

Eleanor K. Seaton, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Cleopatra H. Caldwell, School of Public Health, University of Michigan

Robert M. Sellers, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan

James S. Jackson, Institute for Social Research and Department of Psychology, University of Michigan

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. California: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ML, Collins PH. Why race, class and gender still matter. In: Andersen M, Collins P, editors. Race, Class & Gender: An Anthology. Belmont CA: Wadsworth Publications; 2009. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170– 1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. Subjective measures of well-being. American Psychologist. 1976;31:117–124. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.31.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679– 695. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory ST. The cultural constructs of race, gender and class: A study of how Afro-Caribbean women academics negotiate their careers. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2006;19:347– 366. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Schekeva P, Carter RT. The relationship between racial identity, ethnic identity and perceptions of racial discrimination in an Afro-Caribbean descent sample. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A Multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669– 682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747– 770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, Trierweiler SJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating DP. Cognitive and brain development. In: Lerner RJ, Steinberg LD, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 45–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickrama KS. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: Preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1269– 1274. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.085316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The etiology of gender differences in depression. In: Mazure C, Keita G, editors. Understanding depression in women: Applying empirical research to practice and policy. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ohene S, Ireland M, Blum RW. The clustering of risk behaviors among Caribbean Youth. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2005;9:91– 100. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-2452-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira K, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris K, Bollen K. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race-ethnicity and immigrant generation. Social Forces. 2005;83:1567–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301– 322. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. Black like who? Afro-Caribbean immigrants, African Americans, and the politics of group identity. In: Foner N, editor. Islands in the city: West Indian migration to New York. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2001. pp. 163–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MJ. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288– 1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Scottham KM, Sellers RM. The status model of ethnic identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77:1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Linder NC, Martin PM, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187– 216. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Pratto F. Social dominance theory: A new synthesis. In: Sidanius J, Pratto F, editors. Social Dominance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Herrero-Taylor T, Cameron R, Davis GY. “Mitigating Instigation”: Cultural phenomenological influences of anger and fighting among “bigboned” and “baby-faced” African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:473– 485. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DP, Cunningham M, Spencer MB. Black males’ structural conditions, achievement patterns, normative needs, and “opportunities. Urban Education. 2003;38:605–633. [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Giang MT, Williams DR, Thompson GN. Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:565– 569. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman M. Tweaking a monolith. The West Indian immigrant encounter with “Blackness”. In: Foner N, editor. Islands in the city: West Indian migration to New York. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2001. pp. 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC. The intersection of gender, race and ethnicity in identity development of Caribbean American teens. In: Leadbeater B, Way N, editors. Urban girls: Resisting stereotypes, creating identities. New York: New York University Press; 1996. pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20– 47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity context and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1503–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]