Abstract

IL-4 contributes to immunopathology induced in mice by primary respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. However, the cellular source of IL-4 in RSV infection is unknown. We identified CD3−CD49b+ cells as the predominant source of IL-4 in the lungs of RSV-infected BALB/c mice. We ruled out T cells, NK cells, NKT cells, mast cells, and eosinophils as IL-4 expressors in RSV infection by flow cytometry. Using IL4 GFP reporter mice (4get) mice, we identified the IL-4-expressing cells in RSV infection as basophils (CD3−CD49b+FcεRI+c-kit−). Because STAT1−/− mice have an enhanced Th2-type response to RSV infection, we also sought to determine the cellular source and role of IL-4 in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. RSV infection resulted in significantly more IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of STAT1−/− mice than in BALB/c mice. CD49b+IL-4+ cells sorted from the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice and stained with Wright-Giemsa had basophil characteristics. As in wild-type BALB/c mice, IL-4 contributed to lung histopathology in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. Depletion of basophils in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice reduced lung IL-4 expression. Thus, we show for the first time that a respiratory virus (RSV) induced basophil accumulation in vivo. Basophils were the primary source of IL-4 in the lung in RSV infection, and STAT1 was a negative regulator of virus-induced basophil IL-4 expression.

Keywords: basophils, cytokines, viral, lung

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of bronchiolitis and viral pneumonia in infants worldwide. In the USA, RSV infection results in the hospitalization of >100,000 infants per year (1). The immunologic features of primary RSV infection are not fully defined. In infants, expression of the Th2 cytokine IL-4 has been correlated with RSV disease severity, but not consistently (2–5). Mechanisms by which primary RSV infection leads to IL-4 expression are unexplained. IL-4 is critical for the development of Th2-type inflammation (6). The role of IL-4 has been investigated in a mouse model of primary RSV infection.

IL-4-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 (B6) background exhibit less lymphocytic inflammation in the lung than B6 control mice, suggesting that IL-4 contributes to recruitment of inflammatory cells (7). However, the cellular source of IL-4 in the mouse model of RSV infection has not been defined nor has the role of IL-4 in RSV-induced cytokine production been completely defined. BALB/c mice are more permissive to RSV replication than B6 mice, and BALB/c is the most common mouse strain used for investigating primary RSV pathogenesis (8, 9). The role of IL-4 in the BALB/c mouse model of RSV infection is not known. Both B6 and BALB/c mice exhibit a dominant Th1-type response to primary RSV infection (8). In BALB/c mice, the immune response to primary A2 strain RSV infection is characterized by abundant IFN-γ-producing NK, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and a robust CTL response (10, 11).

STAT1−/− mice are deficient in transcriptional responses to type I (α/β) and type II (γ) IFNs, have increased susceptibility to viral disease, and have an enhanced Th2 phenotype with virus infection (12, 13). Compared to BALB/c controls, primary A2 strain RSV infection of STAT1−/− mice results in increased viral titers, exacerbated disease, elevated IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 levels in the lung, increased airway mucus, eosinophilia, and airway hyerresponsiveness (14, 15). RSV infection increases IL-4 levels in the lung relatively early, 4–6 days post-infection (p.i.), in STAT1−/− mice (14). The cellular source of IL-4 in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice has also not been elucidated. Thus, BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice provide models of Th1 and enhanced Th2 inflammation in response to primary RSV infection, respectively.

Here, we investigated the role of IL-4 in RSV infection in BALB/c (Th1 response) and STAT1−/− (enhanced Th2-type response) mice. We also sought to identify the cell type producing IL-4 in RSV-infected mice. Basophils were the predominant IL-4-expressing cell type in the lung in RSV infection in both BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice. In addition, we found that STAT1 is a regulator of lung basophil IL-4 expression in a model of primary respiratory virus infection.

Materials and Methods

Virus and mice

The A2 strain of RSV was provided by Robert Chanock (NIH). Viral stocks were propagated and titrated by plaque assay in HEp-2 cells as described (16). Female, 6 to 8 wk old BALB/c were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). STAT1−/− mice and CD1d−/− mice on a BALB/c background are described (14, 17). CD1−/−STAT1−/− mice were generated by mating CD1d−/−mice and STAT1−/− mice with subsequent genotyping. IL4−/− mice on a BALB/c background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice were generated by mating STAT1−/− and IL4−/− mice followed by genotyping. Mice expressing a knockin IL4/IRES/EGFP transgene (4get mice, endogenous IL4 expression remains intact) are described (18). 4get mice backcrossed to BALB/c background (C.129-Il4tm1Lky/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and bred to STAT1−/− mice, with subsequent genotyping, to produce STAT1−/−4get mice. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Six to eleven wk old female mice were lightly anaesthetized and infected i.n. with RSV or with mock-infected cell culture supernatant as described (16).

Flow cytometric analysis of lung mononuclear cells

Mice were euthanized with intraperitoneal sodium pentobarbital (Fort Dodge Labs, Fort Dodge, IA), and the lungs were removed. Lung mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque cushion centrifugation (1.09 specific gravity). Cells were counted with a hemacytometer then treated and stained for cell surface molecules and intracellular cytokines as previously described (19). We used the following Abs from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA): anti-CD49b (DX5), anti-CD3, anti-CD8a, anti-CD4, anti-CD11b, anti-IL-4 (or isotype control rat IgG1), anti-IFN-γ, anti-Ly49 G2, anti-CCR3, anti-CD122, anti-Gr-1, and anti-B220. We used anti-NKG2D, anti-FcεR1 (MAR-1), and anti-c-kit Abs obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). We used anti-Ly49 C/F/I/H and anti-Ly49 A Abs obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD16/32 Ab (BD Pharmingen) was used to prevent nonspecific staining. PE-labeled, α-GalCer-loaded tetrameric CD1d molecules (αGC-tetramer) were prepared as described (20, 21). For staining of intracellular cytokines, cells were stimulated in RPMI/10% FBS/1 μM ionomycin (Sigma)/10 ng/ml PMA (Sigma)/7 μl/10ml Golgi Stop (BD Pharmingen) for 6 hr at 37° C and 5% CO2. Cell samples were analyzed using a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). 3 to 5 × 104 lung lymphocytes per animal were analyzed based on forward and side scatter properties. Data were analyzed using Win MDI 2.8 or FlowJo software.

FACS and Wright-Giemsa Staining

Whole lung mononuclear cells were isolated from RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice 5 or 6 days p.i. as described above. Cells were pooled from 8 or 11 mice and stained with anti-CD49b and anti-IL-4 using the intracellular cytokine staining protocol described above. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward and side scatter properties. CD49b+IL-4+ cells within the lymphocyte gate were sorted into 100% FBS using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Post-sort flow cyometric analyses indicated that the purity of sorted CD49b+IL-4+ cells was > 99%. The sorted cells were washed with PBS/3% FBS, applied to a glass slide by cytospin, and stained with Wright-Giemsa.

Bone-marrow derived mast cells (BMMC)

Bone marrow cells were obtained from BALB/c mouse femurs. BMMCs were derived as described (22). Briefly, cells were cultured in MEM with 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 50% WEHI-3 cell-conditioned medium. The cells were maintained for three weeks, and non-adherent cells were passed once per week to fresh medium. The cultures consisted of >80% differentiated mast cells as determined by flow cytometry (c-kit+FcεRI+) and toluidine blue staining characteristics.

In vivo anti-FcεRI treatment

RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were treated i.p. daily on days 1 to 5 p.i.(seven total injections). Mice were given 200 μl of 0.5 mg/ml anti-FcεRI Ab (MAR-1 clone) or affinity purified Armenian hamster IgG as a control (both from eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

Quantitation of viral load and cytokines in lung tissue

Lungs were individually ground with precooled mortar and pestle and sterile ground glass. Glass and tissue debris were removed from lung homogenates by centrifugation (15 min, 2000 rpm, 4° C). Infectious RSV was titrated by plaque assay in HEp-2 cells as described (16). Levels of IFN-γ and IL-13 were measured in lung homogenates using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Dilutions of recombinant cytokines were included for generation of standard curves.

Histopathology

Heart-lung blocks were harvested 7 days p.i. and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Lungs were transferred to 70% ethanol then embedded in paraffin blocks. Tissue sections (5 μm) were stained with H&E to assess histologic changes, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) to assess goblet cell hyperplasia, and Luna stain to assess eosinophilia. Slides were examined and scored by a single pathologist who was blinded to the experimental groups. Alveolar spaces, airways, interstitium, and vessels (both arteries and veins) were examined. Inflammatory infiltrates were assessed for location, severity, and composition (cell types: eosinophils, PMN, macrophages, small lymphocytes, transformed lymphocytes, plasma cells). We quantified mononuclear cell peribronchial cuffing as a measure of inflammation. H&E-stained slides were digitally scanned using a Zeiss MIRAX MIDI microscope with a 20X objective having a 0.85 numerical aperture (Carl Zeiss, Inc). The maximum thickness of mononuclear cell cuffing around each airway was measured using Histoquant software (3D Histech, Budapest, Hungary). We considered 10 μm the limit of detection and assigned airways with no mononuclear cell cuffing a value of 5 μm All airways involved in the tissues were scored (39 to 87 airways per mouse).

Statistical analyses

P values were determined by a two-tailed t test, assuming equal variance, or by one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparison tests. Data are representative of three experiments (except FACS sorting, two experiments) in which similar results were found in all replicate experiments.

Results

IL-4 regulated lung cytokine levels and contributed to lung inflammation in RSV infection

IL-4 contributes to lung inflammation in the context of RSV infection (7). IL4−/− mice have less lymphocytic lung inflammation than B6 controls, and IL4-overexpressing mice correspondingly have more interstitial and intra-alveolar infiltrating lymphocytes than FVB/N control mice (7). Also, primary infection of BALB/c mice with a recombinant IL-4-expressing RSV resulted in enhanced lymphocytic lung inflammation (23). However, the role of endogenous IL-4 in RSV infection in the BALB/c model of RSV infection is not known. We hypothesized that IL-4 contributes to lung inflammation in RSV-infected BALB/c mice. The role of IL-4 in RSV infection in the context of enhanced Th2-type inflammation is not known. We hypothesized that IL-4 plays a role in RSV pathogenesis in the context of enhanced Th2-type inflammation. In order to test this hypothesis, we generated STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice.

We determined the effect of IL-4 on viral load and disease severity in RSV infection in BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice. BALB/c, IL4−/−, STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice were infected with 105 PFU of A2 strain RSV. Lungs were harvested 6 and 8 d p.i. There was no difference in viral load at 6 d p.i. between BALB/c and IL4−/− mice, and there was no difference in viral load between STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice (Table I). The viral loads were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice than in BALB/c and IL4−/− mice, similar to published results (15). There were no detectable viral titers in RSV-infected BALB/c, IL4−/−, STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice 8 d p.i. We measured weight loss as a surrogate for RSV illness severity (14, 16). BALB/c, IL4−/−, STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice were infected with 105 PFU of A2 strain RSV, and the mice were weighed daily 14 d. The BALB/c and IL4−/− mice did not lose weight in response to this dose of virus (data not shown). The STAT1−/− mice lost significantly more weight than BALB/c mice in response to RSV infection (data not shown), as previously published (14). There was no difference in RSV-induced weight loss between STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice (data not shown). Thus, IL-4 had no effect on viral load, viral clearance, and illness severity in RSV infection in BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice.

Table I.

Effect of IL-4 on Viral Loada

| BALB/c (n=7) | IL4−/− (n=5) | STAT1−/− (n=8) | STAT1−/− IL4−/− (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | 4.1 ± 0.09 | 4.3 ± 0.11 | 4.9 ± 0.09 | 4.8 ± 0.12 |

Mice were infected with 105 PFU of RSV. Lungs were harvested 6 d p.i. Infectious virus in the left lung homogenates was titrated by plaque assay. Data are log PFU/g ± SEM.

It was previously demonstrated that peak lung IFN-γ levels in RSV-infected BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice is 6 d.p.i. and that infection induces higher IFN-γ levels in STAT1−/− mice than BALB/c mice (14, 15). We found that RSV-infected IL-4−/− mice had 1.8-fold higher IFN-γ levels than RSV-infected BALB/c mice, whereas there was no difference in lung IFN-γ levels between RSV-infected STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice (Table II). Compared to infected STAT1−/− mice, RSV-infected STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had lower IL-13 levels 8 d.p.i. (Table II). Thus, IL-4 regulated IFN-γ levels in RSV-infected BALB/c mice, and IL-4 regulated IL-13 levels in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice.

Table II.

IL-4 regulated IFN-γ and IL-13 levels in RSV infectiona

| BALB/c (n=12) | IL4−/− (n=9) | STAT1−/− (n=15) | STAT1−/− IL4−/− (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | ||||

| IFN-γ | 144 ± 13b | 260 ± 15b | 1,552 ± 170 | 1,864 ± 292 |

| IL-13 | NDc | NDc | 80 ± 5 | 92 ± 8 |

| Day 8 | ||||

| IFN-γ | 55 ± 8 | 71 ± 11 | 96 ± 14 | 95 ± 14 |

| IL-13 | NDc | NDc | 75 ± 2d | 41 ± 4d |

Mice were infected with 10 PFU of RSV, and cytokines in the left lung homogenates were quantified. Data in pg/ml ± SEM are combined from two experiments.

These groups were significantly different (P < 0.05) comparing d6 IFN-γ levels by ANOVA.

None detected, below detection limit.

These groups were significantly different (P < 0.05) comparing d6 and d8 IL-13 levels in STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice by ANOVA.

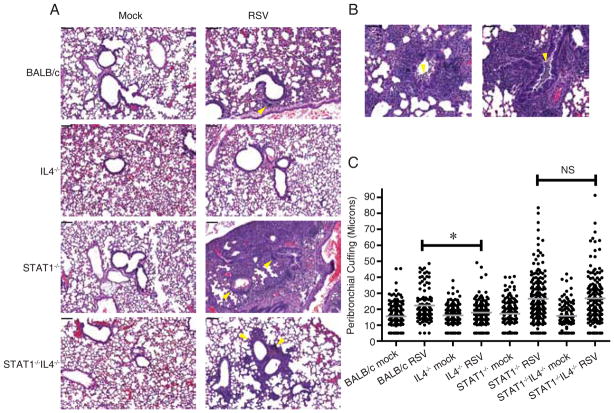

We determined the effect of IL-4 on histopathologic changes induced by RSV infection in BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice. We found that RSV-infected IL4−/− mice on a BALB/c background had less peribronchial lymphocytic inflammation than RSV-infected BALB/c mice (Fig 1A and 1C), results consistent with published data with IL4-deficient mice on a B6 background (7). RSV-infected STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had equivalent bronchovascular (peribronchial and perivascular) cellular infiltrates consisting of eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and small lymphocytes (Fig 1A and 1C). Strikingly, RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice had greater lung consolidation throughout alveolar spaces and more intrabronchial macrophages and eosinophils than RSV-infected STAT1−/− IL4−/− mice (Fig 1A and 1B). RSV-infected STAT1−/− IL4−/− mice did not exhibit significant intrabronchial inflammatory cells. Thus, in the context of Th1-type inflammation seen in BALB/c mice in primary RSV infection, IL-4 contributed to peribronchial lymphocytic inflammation. In the context of enhanced Th2-type inflammation seen in STAT1−/− mice in primary RSV infection, IL-4 contributed to lung consolidation and intrabronchial inflammation.

FIGURE 1.

IL-4 contributed to lung inflammation in RSV-infected BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice. BALB/c, IL4−/−, STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice were mock-infected (n=2 per group) or infected with 105 PFU of RSV (BALB/c, n=2; IL4−/−, STAT1−/−, and STAT1−/−IL4−/−, n=3). Lungs were harvested 7 d.p.i. and processed for H&E staining. A, Representative sections show peribronchial and perivascular inflammation (yellow arrowheads) and consolidation in alveolar spaces (RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice). Scale bars in upper left represent 100 μm. B, Two panels show intrabronchial inflammation (yellow arrowheads) in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. Scale bars in upper left represent 50 μm. C, Peribronchial inflammation was quantified as the maximal distance of mononuclear cell cuffing around bronchi, and all airways involved in the tissues were scored (Materials and Methods). Gray lines show means. *, P < 0.05 (ANOVA). NS, not significantly different.

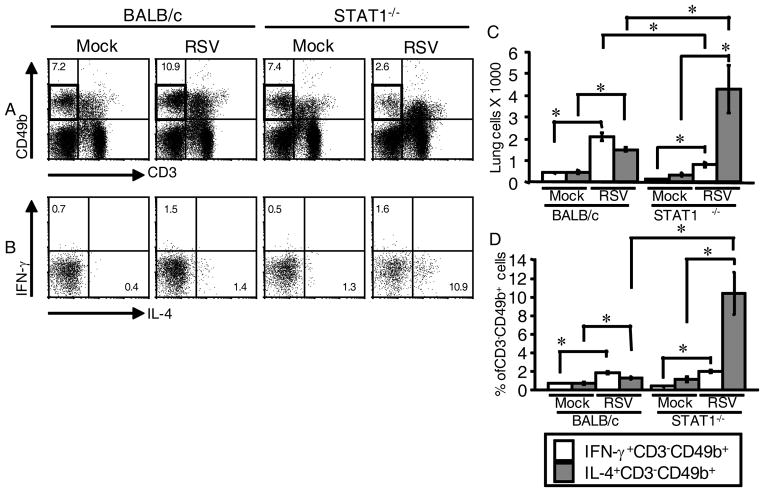

RSV induced IL-4 expression by CD3−CD49b+ cells in BALB/c mice

The immune response to primary A2 strain RSV infection in BALB/c mice is Th1-like, and IL-4 is not detected in lungs by ELISA or ribonuclease protection assay (19). However, IL4−/− mice exhibited significantly decreased lymphocytic inflammation 7 d p.i. in primary RSV infection, as compared to control BALB/c mice (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that RSV infection will induce high levels of IFN-γ expression and low levels of IL-4 expression in CD4+ T cells in the lungs of BALB/c mice.

We measured intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ by flow cytometry. As negative controls for flow cytometric quantification of IL-4, we used an isotype control Ab and IL4−/− mice. Lung mononuclear cells were isolated from mock-infected and RSV-infected BALB/c and IL4−/− mice 6 d p.i, the peak day of T cell numbers and lung IFN-γ levels in response to RSV infection in BALB/c mice. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that RSV induced IL-4 expression in CD3−CD49b+ cells, not T cells. The CD3−CD49b+ immunophenotype defined a cell pool containing both NK cells and basophils (24, 25). Representative dot plots show the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that stained positively for IL-4 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2A) or isotype control Ab for IL-4 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2B). Also shown is the percentage of gated CD4+ T cells that stained positively for IL-4 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2C) and the isotype control Ab for IL-4 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2D). Compared to mock infection, RSV infection increased the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that express IL-4 from 0.3 ± 0.1% to 0.8 ± 0.1%, a 2.7-fold increase (Fig. 2E). RSV infection increased the total number of IL-4+ CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lung 6-fold, from 264 ± 21 in mock-infected mice to 1614 ± 253 in RSV-infected mice (Fig. 2F). RSV infection did not increase the percentage or total number of IL-4+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2, E and F). There were many IFN-γ-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells and CD4+ T cells (Fig 2G), as well as IFN-γexpressing CD8+ T cells (data not shown), in the lungs of RSV-infected BALB/c mice. Taken together, the data are consistent with the phenotype of RSV-infected BALB/c mice being predominantly Th1-like. Nevertheless, primary RSV infection induced IL-4 expression in CD3−CD49b+ cells.

FIGURE 2.

RSV infection induced IL-4 expression in CD3−CD49b+ cells, not CD4+ T cells, in BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice (mock, n=3; RSV, n=4) and IL-4−/− mice (mock, n=5; RSV, n=5) were mock-infected or infected with 105 PFU of RSV. Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 6 d.p.i. and stained with anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD8-APC-Cy7, anti- CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC, anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, and either anti-IL-4 or rat IgG1-PE as an isotype control for IL-4 staining. A–D, Representative dot plots show (A) the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that were IFN-γ-expressing or IL-4-expressing, (B) the IL-4 isotype control staining for CD3−CD49b+ cells, (C) the percentage of gated CD4+ T cells that were IFN-γexpressing or IL-4-expressing, and (D) the IL-4 isotype control staining for CD4+ T cells. E, The percentage of CD3−CD49b+ and CD4+ T cells that were IL-4-expressing was determined for each mouse by subtracting the percentage of PE+ events in the isotype control-stained series from the IL-4-expressing percentage. F, The total number of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ and CD4+ T cells in the lungs. G, The total number of IFN-γ-expressing CD3−CD49b+ and CD4+ T cells in the lungs. *, P < 0.05 comparing RSV to mock.

CD3−CD49b+ cells were the primary source of IL-4 in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice

Primary intranasal (i.n.) RSV infection of STAT1−/− mice increases IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IFN-γ, levels in the lung (14, 15). In order to identify the cellular source of IL-4 in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice, we measured intracellular IL-4 by flow cytometry. For a negative control, we used an isotype control Ab. Whole lung mononuclear cells were isolated 6 d p.i. from STAT1−/− mice that were mock-infected or infected with RSV, and lymphocytes were gated based on forward scatter and side scatter properties (data not shown). We chose 6 d.p.i. because that is the day the number of IFN-γ-producing T cells in the lung (data not shown) and the IFN-γ levels in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice peak (15). Cells that stained positively for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD49b were defined by histogram gates around defined peaks (data not shown). The percentage of CD3−CD49b+ cells that were IL-4+ was 13.8 ± 0.2, and the total number of IL-4+ CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice was 9499 ± 844 (Table III). Compared to mock infection, RSV dramatically increased the percentage (8-fold) and the number (13-fold) of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of STAT1−/− mice (Table III). The percentage of CD4+ T cells that were IL-4+ was 0.1 in both mock-infected and RSV-infected mice (Table III). Thus, RSV infection increased CD3−CD49b+ cell IL-4 expression in STAT1−/− mice 6 d.p.i. and did not increase CD4+ T cell IL-4 expression.

Table III.

Flow cytometric quantitation of CD3−CD49b+ and T cell subsets in lung mononuclear cells isolated 6 d.p.i. from STAT1−/− mice that were mock-infected or infected with 105 PFU of RSV.

| Total number of cells in the lunga | Percentage of parent gateb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Hierarchy | Mock (n=8) | RSV (n=7) | Mock (n=8) | RSV (n=7) |

|

| ||||

| I. Lymphocyte | 383,000 ± 10,800 | 1,080,000 ± 126,000e | N/Ac | N/Ac |

| 1. CD3−CD49b+ | 43,073 ± 2,238 | 69,146 ± 6,225e | 11.3 ± 0.7 | 6.5 ± 1.2e |

| 1a. IFN-γ+ CD3−CD49b+ | 514 ± 204 | 1,599 ± 114e | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1e |

| 1b. IL-4+ CD3−CD49b+ | 724 ± 66 | 9499 ± 844e | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 13.8 ± 0.2e |

| 2. CD4+ Td | 120,357 ± 9,008 | 368,098 ± 75,963e | 31.4 ± 1.9 | 31.1 ± 0.8 |

| 2a.. IFN-γ+CD4+ T | 314 ± 100 | 2,048 ± 223e | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 2b. IL4+CD4+ T | 159 ± 28 | 494 ± 50e | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 3. CD8+ Td | 47,095 ± 4,969 | 128,203 ± 21,994e | 12.2 ± 0.0 | 11.0 ± 0.0 |

| 3a. IFN-γ+CD8+ T | 3,438 ± 1,042 | 22,114 ± 4,776e | 7.0 ± 1.4 | 16.9 ± 0.9e |

| 3b. IL4+CD8 +T | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Total number of cells ± SEM was obtained by calculating the percentage of gated events by the number of lung mononuclear cells isolated.

Lymphocytes were gated using forward and side scatter properties. Values represent mean percentage of gated events within the parental gate ± SEM. For example, in mock-infected STAT1−/− mice, CD3−CD49b+ cells were 11.3% of lymphocytes, and IFN-γ+ CD3−CD49b+ cells were 1.2% of CD3−CD49b+ cells, etc.

There is no gate parental to the lymphocyte gate.

CD4+ T = CD3+CD4+, CD8+ T = CD3+CD8+. These gates were created around histogram peaks.

P < 0.05 compared to mock

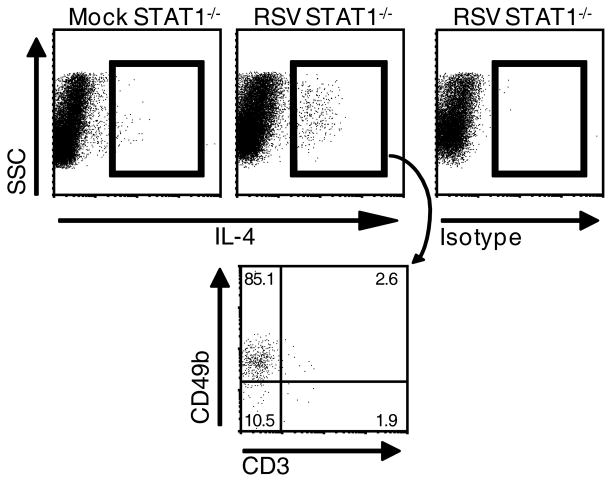

STAT1 regulated CD3−CD49b+ cell IL-4-expression in RSV infection

As RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice have an enhanced Th2 phenotype with RSV infection (14, 15), we hypothesized that the percentage and total number of IL4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells would be greater in the lungs of RSV-infected mice STAT1−/− mice than in the lungs of RSV-infected BALB/c mice. Lung mononuclear cells isolated 6 d.p.i. from STAT1−/− and BALB/c mice that were either mock-infected or infected with RSV were analyzed by flow cytometry. The CD3−CD49b+ gate is outlined in Fig. 3A. Representative dot plots show the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that were IL-4+ or IFN-γ+ (Fig. 3B). RSV infection increased the total number of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells and IFN-γ+CD3−CD49b+ (NK) cells in both STAT1−/− and BALB/c mice (Fig 3C). The total number of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells was 2.8-fold greater in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice than in RSV-infected BALB/c mice, whereas the number of IFN-γ-expressing NK cells was 2.6-fold greater in RSV-infected BALB/c mice than in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice (Fig 3C). A similar pattern was observed when the data were analyzed as the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that were IL-4-expressing or IFN-γ-expressing (Fig. 3D). The number of cells in the lung (Fig. 3C) was calculated using cell counts obtained with a hemacytometer (Materials and Methods). The average total cell counts in each group were 9.27 × 105 (BALB/c mock), 1.15 × 106 (BALB/c RSV), 5.7 × 105 (STAT1−/− mock), and 1.6 × 106 (STAT1−/− RSV). There were significantly more cells in the BALB/c RSV group than the BALB/c mock group, and there were significantly more cells in the STAT1−/− RSV group than the STAT1−/− mock group. There was no significant difference in total cells between the BALB/c RSV and STAT1−/− RSV group. These data show that STAT1 negatively regulates IL-4 expression by CD3−CD49b+ cells and positively regulates IFN-γ expression by NK cells in RSV infection.

FIGURE 3.

STAT1 regulated IL-4 and IFN-γ expression in CD3−CD49b+ cells in RSV infection. BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice were mock-infected (3 mice per group) or infected with 106 PFU of RSV (4 mice per group). Lung mononuclear cells were isolated and stained with anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD49b-APC, anti-CD8-APC-Cy7, anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, and anti-IL-4-PE. A–B, Representative dot plots show (A) Percentage of gated lymphocytes that were CD3−CD49b+ cells and (B) percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that were IFN-γ-expressing or IL-4-expressing. C, The total number of IFN-γ-expressing CD3−CD49b+ and IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs ± SEM. D, The percentage of CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs that were IFN-γexpressing or IL-4-expressing ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 comparing bracketed values.

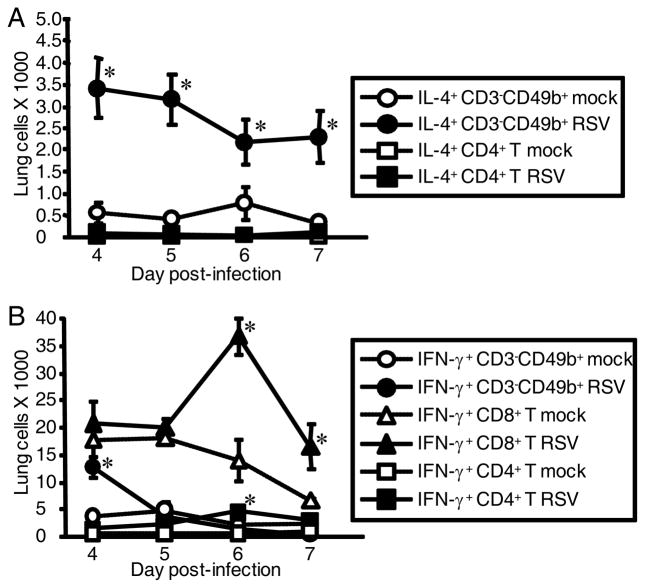

In order to confirm that CD3−CD49b+ cells and not CD4+ T cells are the predominant IL-4-expressing cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice, we back-gated IL-4-expressing cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice and found that approximately 85% of IL-4+ cells were CD3−CD49b+ (Fig. 4). We also performed time course studies to investigate the kinetics and cell type specificity of IL-4 expression in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. Whole lung mononuclear cells were isolated from STAT1−/− mice that were mock-infected or infected with RSV 4, 5, 6, and 7 d.p.i. RSV infection induced IL-4 expression by CD3−CD49b+ cells at all time points assayed, and there was no significant difference in the number of IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells at these time points (Fig. 5A). In contrast, RSV infection did not at any time induce IL-4 expression by CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). We also examined IFN-γ expression by CD3−CD49b+ cells. In BALB/c mice, CD3−CD49b+ is a typical natural killer (NK) cells immunophenotype (25). IFN-γ-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in our system are likely NK cells. The total number of IFN-γ+ NK cells (Fig. 5B) was significantly higher in infected mice than mock-infected mice 4 d.p.i. then decreased. The number of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells (data not shown) and the number of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T and IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells peaked 6 d.p.i. (Fig. 5B). These data are similar to the observation that IFN-γ+ NK cells are detected before IFN-γ+ T cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of RSV-infected BALB/c mice (11). Taken together, RSV infection of STAT1−/− mice resulted in IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lung d 4–7 and resulted in peak IFN-γ+ NK cells at d 4 followed by peak IFN-γ+ T cells at d6.

FIGURE 4.

IL-4-expressing cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice predominantly had a CD3−CD49b+ immunophenotype. Gating of IL-4-expressing lymphocytes (rectangular gate) in experiment described in Figure 1. The percentages of gated IL-4-expressing lymphocytes from RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice that were CD3−CD49b+, CD3−CD49b−, CD3+CD49b+, and CD3+CD49b− is shown in the dot plot indicated by the arrow.

FIGURE 5.

Time course of IFN-γ-expressing and IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ and T cell subsets from the lungs of STAT1−/− mice in response to RSV infection. STAT1−/− mice were mock-infected (3 mice per group) or infected with 106 PFU of RSV (4 mice per group). Lung mononuclear cells were isolated at the indicated day, counted, and cells from individual mice were stained with anti-CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC, anti-CD8-APC- Cy7, anti-CD4-Pacific Blue, anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, and either anti-IL-4-PE or rat IgG1-PE as isotype control for IL-4. CD8+ T cell gate = CD3+CD8+, and CD4+ T cell gate = CD3+CD4+. A, The numbers of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ and IL-4-expressing CD4+ T cells ± SEM were obtained by subtracting the percentage of gated PE+ events in the isotype control-stained cells from the percentage of gated IL-4-expressing cells and multiplying by the total number of cells isolated. B, Total numbers of IFN-γ-expressing CD3−CD49b+, IFN-γ-expressing CD4+ T, and IFN-γ-expressing CD8+ T cells ± SEM cells in the lung were obtained by multiplying the percentage of lymphocytes that were in the indicated gates by the total number of cells isolated. *, P < 0.05 comparing RSV (filled symbols) to mock (open symbols).

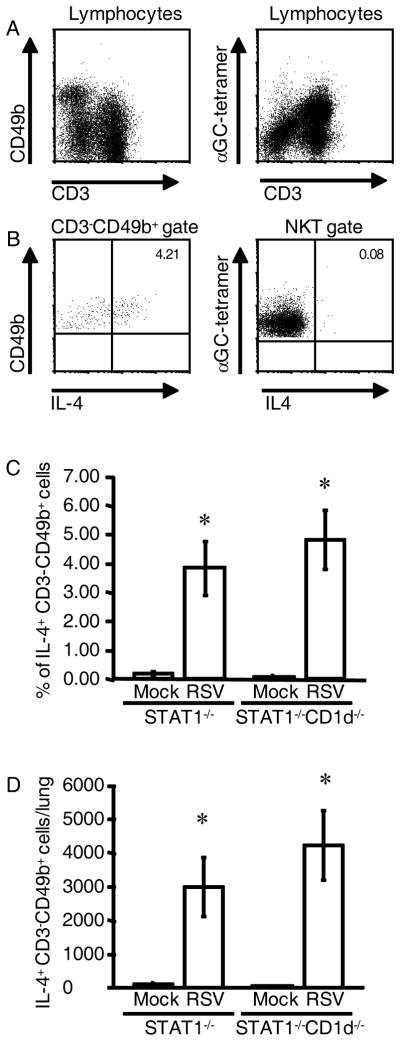

IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were not NKT cells

It has been shown that CD1-restricted natural killer T (NKT) cells can produce abundant IL-4 and IFN-γ upon activation and regulate IL-4 and IFN-γ levels in vivo (26, 27). Also, activated NKT cells transiently down-regulate T cell receptor expression upon activation in vitro (28, 29). Therefore, it was possible that IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice are NKT cells. We tested the hypothesis that NKT cells are the IL-4-producing cells in RSV-infected mice in two ways. First, we quantified IL-4 expression by NKT cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice using tetramers loaded with α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer). NKT cells recognize glycolipid antigens presented by MHC class I-like CD1d, and NKT cells recognize the artificial ligand α-GalCer (28). Gated lymphocytes in lung mononuclear cells from RSV-infected mice 5 d.p.i. contained large numbers of αGC-tetramer+CD3+B220− NKT cells (Fig. 6A). Exclusion of B220+ cells is necessary for staining NKT cells because B cells can express CD1d (30, 31). The percentage of αGC-tetramer+B220− NKT cells (CD3+ or CD3−) that expressed IL-4 was < 0.1%, compared to 4.21% of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells that expressed IL-4 (Fig. 6B). The second way we excluded NKT cells as IL-4-expressing cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice was by generating NKT cell-deficient STAT1−/−CD1d−/− mice and quantifying IL-4-expressing cells in these mice and STAT1−/− mice that were infected with RSV. There was no difference in the percentage (Fig. 6C) or total number (Fig. 6D) of IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−CD1d−/− mice 5 d.p.i. Taken together, these data demonstrate that IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of STAT1−/− mice are not NKT cells with down-regulated CD3 expression. Furthermore, we identified NKT cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice using tetramer staining, and these cells did not express IL-4.

FIGURE 6.

NKT cells were not the source of IL-4 in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. A–C, STAT1−/− mice were mock-infected (n=2) or infected with 106 PFU of RSV (n=2). Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 5 d.p.i. and stained with anti-CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC-Cy7, anti-CD4-PE-Cy7, anti-B220-FITC, α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers-PE (αGC-tetramer), and anti-IL-4-APC. B220+ cells were excluded by gating in the plots in the right column. Representative dot plots from infected mice show (A) populations of CD3−CD49b+ and NKT (αGC-tetramer+, CD3+, B220−) cells, (B) the percentage of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells and αGC-tetramer+ cells that were IL-4-expressing. C-D, STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−CD1d−/− mice were mock-infected (n=4 per group) or infected with 105 PFU of RSV (n=6 per group). Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 6 d.p.i. and stained with anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD8-APC-Cy7, anti-CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC, anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, and either anti-IL-4 or rat IgG1-PE as an isotype control for IL-4 staining. For each mouse, the percentage of IL-4-expressing gated CD3−CD49b+ cells (D) was obtained by subtracting the percentage of PE+ gated CD3−CD49b+ cells in the isotype control-stained series of cells. Percentage ± SEM is shown. E, The total number of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells per lung ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 comparing RSV to mock.

IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice are not NK cells, mast cells, or eosinophils

We analyzed IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected mice by flow cytometry in order to identify their cell type. We used STAT1−/− mice because RSV induces more IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lung in these mice than in BALB/c mice. Experiments described above showed these cells are CD3−CD4−CD8− (Table III). In a series of experiments, STAT1−/− mice were mock-infected or infected with RSV, lung mononuclear cells were isolated d 5 or d6 p.i., and intracellular cytokine and cell surface markers were analyzed by flow cytometry.

As CD3−CD49b+ is an NK cell phenotype, we tested the hypothesis that the IL-4-expressing cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice are NK cells. The IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were NKG2D− and CD122− (data not shown). We used a cocktail (Ly49s) of FITC-labeled anti-Ly49 C/F/H/A Ab, FITC-labeled anti-Ly49 A, and FITC-labeled anti-Ly49 G2. The IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were Ly49s− (data not shown). The IFN-γ+CD3−CD49b+ in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were NKG2D+CD122+Ly49s+, confirming that these cells as NK cells (data not shown). Thus, IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were not NK cells.

It has been shown that mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils can express IL-4, as measured by flow cytometric analyses of GFP expression and cell surface markers of peripheral blood and bone marrow cells of bicistronic IL-4 reporter 4get mice (32). We tested whether the IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice are either mast cells, basophils, or eosinophils by flow cytometry. We defined mast cells as SSChighFcεRI+c-kit+CD3−, basophils as SSClowFcεRI+c-kit−CCR3−CD3−, and eosinophils as SSChighFcεRI−c-kit−CCR3+CD3− (32). We used bone marrow-derived mast cells as positive controls for FcεRI and c-kit staining. Using intracellular cytokine staining, we found that IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were SSClowc-kit−CCR3−, indicating that the IL-4-expressing cells are not mast cells or eosinophils (data not shown). We also found that IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice were CD11b+/−Gr-1−B220− (data not shown). Thus, we ruled out mast cells and eosinophils as the identity of IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice.

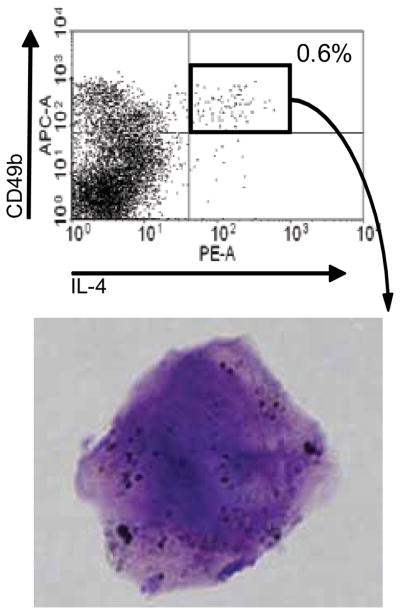

IL-4+CD49b+ cells from the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice had light microscopic characteristics of basophils

We investigated IL-4+CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected mice histologically. We sorted these cells and stained them with Wright-Giemsa. Two experiments were performed. Whole lung mononuclear cells were isolated from RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice 5 or 6 days p.i. Cells were pooled from 8 or 11 mice and stained with anti-CD49b and anti-IL-4. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward and side scatter properties. IL-4+CD49b+ cells were 0.6% of cells within the FSClowSSClow “lymphocyte” gate (Fig. 7). Approximately 2,500 CD49b+IL-4+ cells were obtained from the lungs of each RSV-infected STAT1−/− mouse. Sorted cells were cytospun and stained with Wright-Giemsa. There is considerable debate about the histologic features of mouse basophils. Lee and McGarry recently reviewed the literature on the flow cytometric immunophenotyes, morphology, and staining characteristics of human and mouse basophils (25). Basophils have “metachromatic-stained granules that are asymmetrically distributed throughout the cytoplasm and a lobulate nucleus that has comparatively weak staining chromatin,” and mouse basophils “have relatively few, loosely packed granules of unequal size” (25). The hematologic appearance of the IL-4+CD49b+ cells we sorted was consistent with basophil characteristics (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Sorted IL-4+CD49b+ cells isolated from RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice had histologic features of basophils. Eleven STAT1−/− mice were infected with RSV. Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 5 d p.i. and stained with anti-CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC and anti IL-4-PE. The IL-4+CD49b+ cells were sorted as described in the materials and methods, cytospun, and stained with Wright-Giemsa. Representative cell is shown.

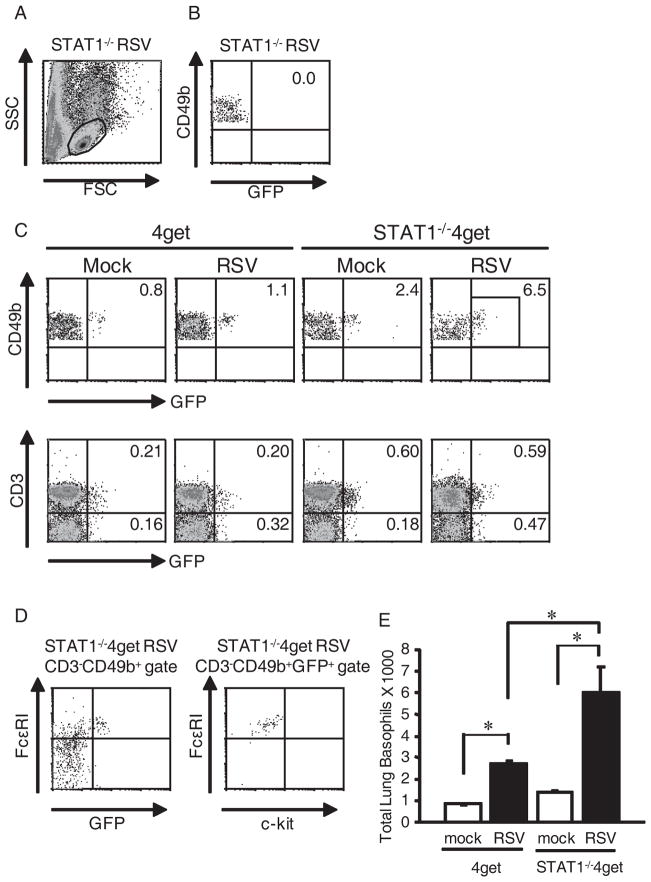

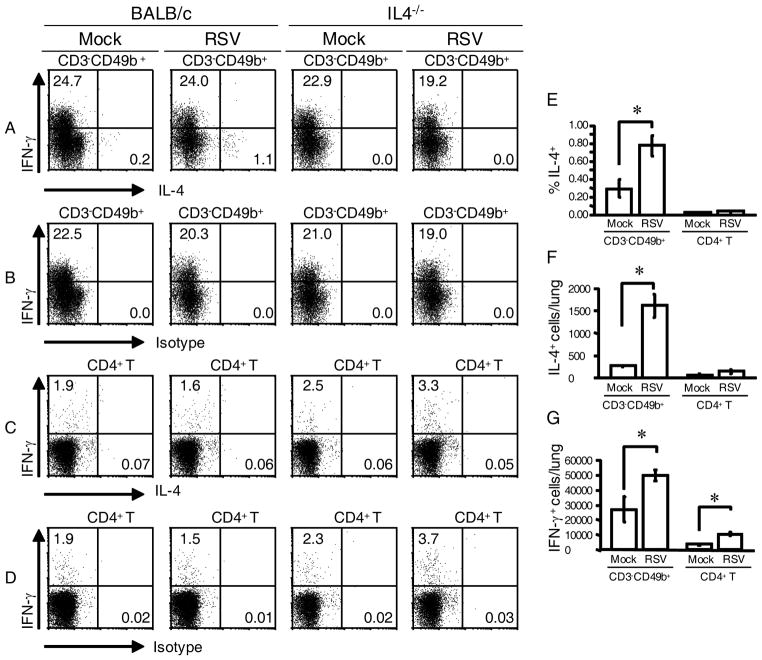

IL-4-expressing cells in RSV-infected BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice were basophils

Using BMMCs, we found that the anti-FcεRI Ab yielded good positive staining when only cell surface markers were analyzed but did not yield definitive positive staining in our intracellular cytokine staining protocol, likely due to effects from cell permeabilization (data not shown). Therefore, we used 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice to test the hypothesis that CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected mice are basophils. 4get mice are useful for investigating IL-4 expression in BALB/c mice. Connective tissue mast cells as well as blood basophils and eosinophils from 4get mice constitutively transcribe IL-4 mRNA, but IL-4 protein expression requires cell stimulation (32). STAT1−/−, 4get, and STAT1−/−4get mice were mock-infected or infected with RSV. Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 6 d p.i., stained with cell surface markers, and analyzed by flow cytometry. FSClowSSClow cells were gated (Fig. 8A). Gated CD3−CD49b+ cells from infected STAT1−/− exhibited no background autofluorescence in the GFP range (Fig. 8B). In both 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice, RSV infection increased the percentage of CD3−CD49b+ cells that were GFP+ but did not increase the percentage of T cells that were GFP+ (Fig. 8C). Gated CD3−CD49b+ cells from RSV-infected STAT1−/−4get mice (Fig. 8D) and RSV-infected 4get mice (data not shown) expressed high levels of FcεRI but did not express c-kit, whereas BMMC controls expressed high levels of FcεRI and c-kit (data not shown). RSV infection increased the total number of IL-4-expressing (GFP+) basophils in the lungs of 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice, and there were significantly more IL-4-expressing basophils in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/−4get mice than RSV-infected 4get mice (Fig. 8E). These data are consistent with the total numbers of IL-4-expressing cells we obtained by intracellular cytokine staining in RSV-infected BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 3). Thus, we identified the IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected mice as basophils.

FIGURE 8.

CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected mice were basophils. STAT1−/−, 4get, and STAT1−/−4get mice were mock-infected (n=2 per group) or infected with RSV (n=3 per group). Lung mononuclear cells were isolated 6 d p.i. and stained with anti-CD3-APC-Cy7, anti-CD49b-biotin/streptavidin-APC, anti-FcεRI-PE, and anti-c-kit-PE-Cy7. (A), Parental lymphocyte gate for all analyses in this experiment is shown. (B), Gated CD3−CD49b+ cells from RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice (negative control for GFP). The percentage of GFP+ cells is indicated. (C), Percentage of GFP+ cells among gated CD3−CD49b+ lung cells in mock-infected and RSV-infected 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice is indicated in the top row. The percentage of GFP+CD3+ (T cells) and GFP+CD3− (non-T cells) cells in the lymphocyte gate in mock-infected and RSV-infected 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice is indicated in the bottom row. (D), FcεRI and c-kit expression by CD3−CD49b+ cells from RSV-infected STAT1−/−4get mice. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (E), Total numbers of gated CD3−CD49b+FcεRI+c-kit−GFP+ cells (basophils) in the lungs of mock-infected and RSV-infected 4get and STAT1−/−4get mice were obtained by multiplying the percentage of cells by the total number of cells isolated. *, P < 0.05.

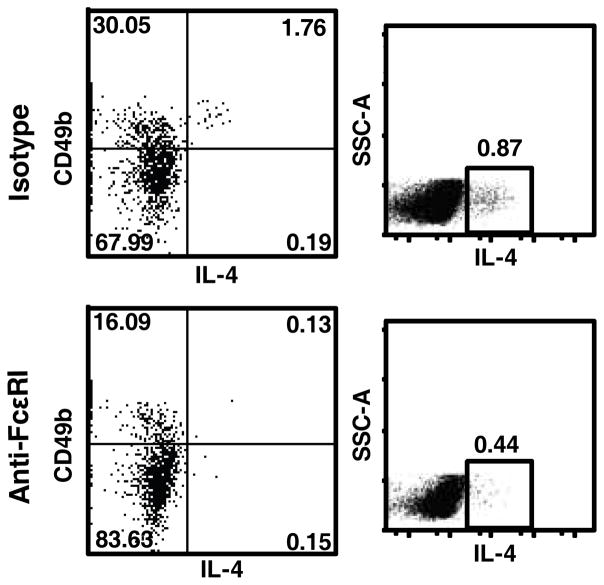

Basophils contributed to lung IL-4 expression in RSV infection

The MAR-1 clone anti-FcεRI Ab has been shown to deplete basophils (33). We depleted basophils in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice using this Ab, or treated mice with an isotype control Ab. The treatment effectively depleted IL-4-expressing basophils from the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 9). Gating on the FSClowSSClow population typical for lymphocytes and basophils, we found that basophil depletion eliminated the majority of IL-4-expressing cells from the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 9). We did not observe IL-4+ cells outside this FSClowSSClow gate, similar to Fig. 4. Thus, basophils were the predominant IL-4-expressing cell type in the lungs of these RSV-infected mice. We assayed IL-4 protein levels by ELISA in RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice, but the levels were below the detection limit (data not shown). Thus, we were not able to determine the effect of basophil depletion on whole lung IL-4 protein levels. We assessed the role of basophils in RSV-induced lung histopathologic changes in STAT1−/− mice. STAT1−/− mice were infected with 105 PFU of RSV, treated with anti-FcεRI Ab or contol Ab (Materials and Methods), and lungs were harvested 7 d.p.i. We observed no effect of basohil depletion on histopathology (data not shown).

FIGURE 9.

Basphils were predominant IL-4-expressing cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. STAT1−/− mice were infected with 105 PFU of RSV. Mice were treated with anti-FcεRI (MAR-1 clone) or with an isotype control Ab (4 mice per group) as described in Materials and Methods. Lungs were harvested 6 d.p.i and cells were stained with anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD4-PE-Cy7, anti-CD49b-APC, and anti-IL-4-PE. Left panels show representative dot plots of gated CD3−CD49b+ cells. Right panels show representative dot plots of gated FSClowSSClow cells.

Discussion

Our study shows for the first time that a respiratory virus (RSV) induces basophil accumulation and basophil IL-4 expression in vivo. We investigated the role and cellular source of IL-4 in RSV infection in BALB/c (Th1-type inflammation) and STAT1−/− mice (enhanced Th2-type inflammation). Our data show that IL-4 is important in RSV pathogenesis in these models. RSV-infected IL4−/− mice had higher IFN-γ levels in the lung than RSV-infected BALB/c mice. In contrast, RSV-infected STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had lung IFN-γ levels similar to RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. We conclude from these data that IL-4 regulation of IFN-γ production is STAT1-dependent. RSV-infected STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had lower IL-13 lung levels than RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice 8 d.p.i. but not 6 d.p.i. Thus, there is IL-4-dependent and IL-4-independent IL-13 production in response to RSV infection in STAT1−/− mice, results seen in mouse models of allergic inflammation (34, 35).

In addition to modulating cytokine levels in the lung, we found that IL-4 contributes to RSV-induced cellularity in the lung in BALB/c mice, in which Th1-type inflammation is characteristic, as well as in STAT1−/− mice, in which enhanced Th2-type inflammation is characteristic. Interestingly, RSV-infected STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had less lung consolidation and fewer intrabronchial inflammatory cells than RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. This is an important finding because RSV is the leading cause of mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure in infants (36), and it is thought that inflammatory cells contribute to airway blockage. IL4 and IL4Rα polymorphisms are have been associated with severe RSV bronchiolitis in infants (37). IL-4 has been shown to mediate RSV disease severity in mice immunized with formalin-inactivated, alum-precipitated RSV and then challenged with RSV, a model of RSV vaccine-enhanced illness (38). Immunocompetent mice exhibit a Th1-dominant response to primary RSV infection. RSV pathogenesis has been studied in the setting of Th2 inflammation using mice immunized with formalin-inactivated virus, using mice primed with vaccinia virus that expresses RSV G, using RSV combined with mouse models of allergic inflammation, and using recombinant RSV that expresses IL-4 (8, 10). Our data with STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice demonstrate that IL-4 contributed to lung inflammation in the setting of Th2-type inflammation induced by primary RSV infection.

We used two different doses of RSV in this study, 105 PFU and 106 PFU per mouse. The reason is as follows. We performed experiments for Figures 3–6 first, using 106 PFU per mouse. Then we performed histopathology experiments using 106 PFU per mouse. At this high dose, STAT1−/− and STAT1−/− IL4−/− mice succumbed to RSV infection at day 7 post-infection (e.g. last time point Fig. 5). As 106 PFU overwhelmed the STAT1−/− mice, we performed histopathology experiments using 105 PFU per mouse (Fig. 1). We then performed viral load, cytokine measurements, and further flow cytometric analyses (Tables I, II, and III, and Figs. 2, 7–9) using 105 PFU. Basophils were the predominant IL-4-expressing cell type in the lung in RSV infection in BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice at both 105 and 106 PFU.

Activated NKT cells are known to produce IL-4 and to down-regulate T cell receptor expression upon activation (28, 29). We excluded NKT cells as the CD3−CD49b+ IL-4-expressing cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. First, by α-GC-loaded CD1 tetramer-staining we showed NKT cells were not the IL-4-expressing cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. Also, we generated NKT cell-deficient CD1d−/−STAT1−/− mice, and NKT cell deficiency had no effect on the percentage or number of IL-4-expressing CD3−CD49b+ cells in the lungs of RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. Emerging cell immunophenotype data continuously redefines our classification of immune cells. For example, cells that express both NK and dendritic cell (DC) markers are described (39, 40). Interferon-producing killer DCs (IKDCs) can transition from cytotoxic effectors to DC-like Ag presentation upon stimulation in vitro (41). CD3−CD49b+IL-4+ cells in our studies are not IKDCs because they are B220− (data not shown).

Several recent studies indicate that basophils play a key role in Th2 inflammation induction, immune memory, and Ag capture. IL-4-expressing basophils were found in the bronchoalveolar lavage of patients following segmental allergen challenge (42). In mice primed with goat anti-mouse IgD and then challenged with goat serum, a model of robust Th2 inflammation in vivo, basophils were found to initiate IL-4 production (43). Infection of mice with the Th2-inducing parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis results in basophils IL-4 expression and basophilia (44). Adoptive transfer of basophils in IgE-mediated allergic inflammation showed that these cells play a role in chronic inflammation (45). Coculture experiments demonstrated that basophil-supported CD4+ T cell Th2 differentiation in vitro depends on IL-4 produced by basophils (46). Immunizing mice with the fluorophore APC showed that basophils can act as Ag-capturing cells (47, 48). Basophils migrated to the draining lymph node and expressed IL-4 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) in mice immunized and challenged with papain (33). Basophils and TSLP were required for Th2 induction in this model (33). Thus, basophils are key innate regulators of Th2 inflammation. STAT1−/− and STAT1−/−4get mice may be useful for studying basophils because basophils are rare in wild-type mice (25).

We found that RSV infection induced pulmonary basophil accumulation and basophil IL-4 expression. Basophils were the vast majority of IL-4-expressing cells in the lung in primary RSV infection. RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice had more IL-4-expressing basophils than RSV-infected BALB/c mice. Thus, STAT1 negatively regulated RSV infection-induced basophil accumulation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of basophil inflammation induced by a respiratory virus. As in important source of IL-4, basophils may provide a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity in RSV infection.

We investigated the role of basophils in RSV pathogenesis in STAT1−/− mice using anti-FcεRI Ab to deplete basophils in vivo, as described (33). Basophils were indeed the primary source of IL-4 expression in the lungs of RSV-infected mice because basophil depletion ablated the majority of IL-4-expressing cells. We did not detect IL-4 protein by ELISA in lung homogenates in any RSV-infected mice in this study (data not shown). We did not observe a difference in mononuclear cell bronchovascular (perivascular and peribronchial) inflammation, a difference in lung consolidation in alveolar spaces, nor a difference in intrabronchial inflammatory cells, between basophil-depleted and control Ab-treated RSV-infected STAT1−/− mice. This result was somewhat surprising because STAT1−/−IL4−/− mice had less lung consolidation and intrabronchial inflammatory cells than STAT1−/− mice in the setting of RSV infection. It may be that systemic IgG Ab treatment (depleting and control Ab) has some immune effects that mask the effect of basophil depletion. Also, although the anti-FcεRI Ab clearly depleted IL-4-expressing basophils in this study and has been used by others for functional assessment of basophils in mice, the mechanism of depletion is not clear (33). It is possible that the anti-FcεRI Ab could have additional effects such as receptor crosslinking on basophils and/or mast cells which could result in immune activation and degranulation. The Ba103 mAb which recognizes CD200R3, has been used to deplete basophils in mice, but this receptor is also expressed on mast cells (49). The field would benefit from a specific basophil-deficient mouse model.

In a collaborative study, we previously found that the line 19 strain of RSV induces greater IL-13, airway hyperreactivity, and airway mucus expression in BALB/c mice than the A2 laboratory strain of RSV (50). In the present study, we use the A2 strain and identified basophils as the source of IL-4 in primary infection in BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice. Further studies will be required to determine whether increased basophil responses contribute to elevated IL-13 levels in response to infection with line 19 or other mucogenic RSV strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sebastian Joyce for the α–GC-tetramers and Kirin Brewery Company (Gunma, Japan) for providing synthetic α-GalCer. We thank John Schroeder (Johns Hopkins Medicine) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, Liu LL, Stout JW, Anderson LJ. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980–1996. JAMA. 1999;282:1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandenburg AH, Kleinjan A, van Het LB, Moll HA, Timmerman HH, de Swart RL, Neijens HJ, Fokkens W, Osterhaus AD. Type 1-like immune response is found in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection regardless of clinical severity. J Med Virol. 2000;62:267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garofalo RP, Patti J, Hintz KA, Hill V, Ogra PL, Welliver RC. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha (not T helper type 2 cytokines) is associated with severe forms of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:393–399. doi: 10.1086/322788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legg JP, I, Hussain R, Warner JA, Johnston SL, Warner JO. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine imbalance in acute respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:633–639. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1148OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roman M, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, Avendano LF, Simon V, Escobar AM, Gaggero A, Diaz PV. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants is associated with predominant Th-2-like response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:190–195. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9611050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopf M, Le Gros G, Bachmann M, Lamers MC, Bluethmann H, Kohler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–248. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer JE, Johnson JE, Kuli-Zade RK, Johnson TR, Aung S, Parker RA, Graham BS. Overexpression of interleukin-4 delays virus clearance in mice infected with respiratory syncytial virus. The Journal of Virology. 1997;71:8672–8677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8672-8677.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore ML, Peebles RS., Jr Respiratory syncytial virus disease mechanisms implicated by human, animal model, and in vitro data facilitate vaccine strategies and new therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prince GA, Horswood RL, Berndt J, Suffin SC, Chanock RM. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in inbred mice. Infect Immun. 1979;26:764–766. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.764-766.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham BS, Johnson TR, Peebles RS. Immune-mediated disease pathogenesis in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Immunopharmacology. 2000;48:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussell T, Openshaw PJ. Intracellular IFN-gamma expression in natural killer cells precedes lung CD8+ T cell recruitment during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 11):2593–2601. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-11-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durbin JE, Fernandez-Sesma A, Lee CK, Rao TD, Frey AB, Moran TM, Vukmanovic S, Garcia-Sastre A, Levy DE. Type I IFN modulates innate and specific antiviral immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:4220–4228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durbin JE, Hackenmiller R, Simon MC, Levy DE. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell. 1996;84:443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durbin JE, Johnson TR, Durbin RK, Mertz SE, Morotti RA, Peebles RS, Graham BS. The role of IFN in respiratory syncytial virus pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2002;168:2944–2952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto K, Durbin JE, Zhou W, Collins RD, Ho SB, Kolls JK, Dubin PJ, Sheller JR, Goleniewska K, O’Neal JF, Olson SJ, Mitchell D, Graham BS, Peebles RS., Jr Respiratory syncytial virus infection in the absence of STAT 1 results in airway dysfunction, airway mucus, and augmented IL-17 levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham BS, Perkins MD, Wright PF, Karzon DT. Primary respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J Med Virol. 1988;26:153–162. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JQ, Singh AK, Wilson MT, Satoh M, Stanic AK, Park JJ, Hong S, Gadola SD, Mizutani A, Kakumanu SR, Reeves WH, Cerundolo V, Joyce S, Van Kaer L, Singh RR. Immunoregulatory role of CD1d in the hydrocarbon oil- induced model of lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2003;171:2142–2153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohrs M, Shinkai K, Mohrs K, Locksley RM. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity. 2001;15:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peebles RS, Jr, Sheller JR, Collins RD, Jarzecka AK, Mitchell DB, Parker RA, Graham BS. Respiratory syncytial virus infection does not increase allergen-induced type 2 cytokine production, yet increases airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Med Virol. 2001;63:178–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Wu L, Wang CR, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2572–2583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanic AK, De Silva AD, Park JJ, Sriram V, Ichikawa S, Hirabyashi Y, Hayakawa K, Van Kaer L, Brutkiewicz RR, Joyce S. Defective presentation of the CD1d1-restricted natural Va14Ja18 NKT lymphocyte antigen caused by beta-D-glucosylceramide synthase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1849–1854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430327100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razin E, Ihle JN, Seldin D, Mencia-Huerta JM, Katz HR, LeBlanc PA, Hein A, Caulfield JP, Austen KF, Stevens RL. Interleukin 3: A differentiation and growth factor for the mouse mast cell that contains chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan. The Journal of Immunology. 1984;132:1479–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bukreyev A, I, Belyakov M, Prince GA, Yim KC, Harris KK, Berzofsky JA, Collins PL. Expression of interleukin-4 by recombinant respiratory syncytial virus is associated with accelerated inflammation and a nonfunctional cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response following primary infection but not following challenge with wild-type virus. The Journal of Virology. 2005;79:9515–9526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9515-9526.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arase H, Saito T, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Cutting edge: the mouse NK cell-associated antigen recognized by DX5 monoclonal antibody is CD49b (alpha 2 integrin, very late antigen-2) J Immunol. 2001;167:1141–1144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JJ, McGarry MP. When is a mouse basophil not a basophil? Blood. 2007;109:859–861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, Van Kaer L, Saiki I, Okumura K. Differential regulation of Th1 and Th2 functions of NKT cells by CD28 and CD40 costimulatory pathways. J Immunol. 2001;166:6012–6018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parekh VV, Singh AK, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Bezbradica JS, Inazawa H, Ehara H, Sakai T, Serizawa I, Wu L, Wang CR, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the in vivo response of NKT cells to distinct alpha- and beta-anomeric glycolipids. J Immunol. 2004;173:3693–3706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson MT, Johansson C, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Stanic AK, Wang CR, Joyce S, Wick MJ, Van Kaer L. The response of natural killer T cells to glycolipid antigens is characterized by surface receptor down-modulation and expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10913–10918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833166100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belperron AA, Dailey CM, Bockenstedt LK. Infection-induced marginal zone B cell production of Borrelia hermsii-specific antibody is impaired in the absence of CD1d. J Immunol. 2005;174:5681–5686. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canchis PW, Bhan AK, Landau SB, Yang L, Balk SP, Blumberg RS. Tissue distribution of the non-polymorphic major histocompatibility complex class I-like molecule, CD1d. Immunology. 1993;80:561–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gessner A, Mohrs K, Mohrs M. Mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils acquire constitutive IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts during lineage differentiation that are sufficient for rapid cytokine production. J Immunol. 2005;174:1063–1072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sokol CL, Barton GM, Farr AG, Medzhitov R. A mechanism for the initiation of allergen-induced T helper type 2 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:310–318. doi: 10.1038/ni1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto K, Sheller JR, Morrow JD, Collins RD, Goleniewska K, O’Neal J, Zhou W, Ji S, Mitchell DB, Graham BS, Peebles RS., Jr Cyclooxygenase inhibition augments allergic inflammation through CD4-dependent, STAT6-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:525–532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrick CA, MacLeod H, Glusac E, Tigelaar RE, Bottomly K. Th2 responses induced by epicutaneous or inhalational protein exposure are differentially dependent on IL-4. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:765–775. doi: 10.1172/JCI8624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoebee B, Rietveld E, Bont L, Oosten M, Hodemaekers HM, Nagelkerke NJ, Neijens HJ, Kimpen JL, Kimman TG. Association of severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis with interleukin-4 and interleukin-4 receptor alpha polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:2–11. doi: 10.1086/345859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang YW, Graham BS. Anti-IL-4 treatment at immunization modulates cytokine expression, reduces illness, and increases cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in mice challenged with respiratory syncytial virus. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1953–1958. doi: 10.1172/JCI117546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Josien R, Heslan M, Soulillou JP, Cuturi MC. Rat spleen dendritic cells express natural killer cell receptor protein 1 (NKR-P1) and have cytotoxic activity to select targets via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;186:467–472. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pillarisetty VG, Katz SC, Bleier JI, Shah AB, DeMatteo RP. Natural killer dendritic cells have both antigen presenting and lytic function and in response to CpG produce IFN-gamma via autocrine IL-12. J Immunol. 2005;174:2612–2618. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan CW, Crafton E, Fan HN, Flook J, Yoshimura K, Skarica M, Brockstedt D, Dubensky TW, Stins MF, Lanier LL, Pardoll DM, Housseau F. Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells provide a link between innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Med. 2006;12:207–213. doi: 10.1038/nm1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeder JT, Lichtenstein LM, Roche EM, Xiao H, Liu MC. IL-4 production by human basophils found in the lung following segmental allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:265–271. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khodoun MV, Orekhova T, Potter C, Morris S, Finkelman FD. Basophils initiate IL-4 production during a memory T-dependent response. J Exp Med. 2004;200:857–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Min B, Prout M, Hu-Li J, Zhu J, Jankovic D, Morgan ES, Urban JF, Jr, Dvorak AM, Finkelman FD, LeGros G, Paul WE. Basophils produce IL-4 and accumulate in tissues after infection with a Th2-inducing parasite. J Exp Med. 2004;200:507–517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukai K, Matsuoka K, Taya C, Suzuki H, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K, Hirokawa K, Etori M, Yamashita M, Kubota T, Minegishi Y, Yonekawa H, Karasuyama H. Basophils play a critical role in the development of IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation independently of T cells and mast cells. Immunity. 2005;23:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oh K, Shen T, Le Gros G, Min B. Induction of Th2 type immunity in a mouse system reveals a novel immunoregulatory role of basophils. Blood. 2007;109:2921–2927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denzel A, Maus UA, Rodriguez GM, Moll C, Niedermeier M, Winter C, Maus R, Hollingshead S, Briles DE, Kunz-Schughart LA, Talke Y, Mack M. Basophils enhance immunological memory responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:733–742. doi: 10.1038/ni.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mack M, Schneider MA, Moll C, Cihak J, Bruhl H, Ellwart JW, Hogarth MP, Stangassinger M, Schlondorff D. Identification of antigen-capturing cells as basophils. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174:735–741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsujimura Y, Obata K, Mukai K, Shindou H, Yoshida M, Nishikado H, Kawano Y, Minegishi Y, Shimizu T, Karasuyama H. Basophils play a pivotal role in immunoglobulin-G-mediated but not immunoglobulin-E-mediated systemic anaphylaxis. Immunity. 2008;28:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lukacs NW, Moore ML, Rudd BD, Berlin AA, Collins RD, Olson SJ, Ho SB, Peebles RS., Jr Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]