Abstract

Objective:

Efficacy and tolerability profiles of Treximet [sumatriptan/naproxen sodium combination tablet (SNC)] have been established in clinical trials but have to date been virtually unstudied in pragmatic research. The primary objective of this study was to compare the overall satisfaction of SNC to its monotherapy components, S/N [one 100 mg Imitrex tablet (S) and two Aleve (naproxen sodium) 220 mg tablets, total dose 440 mg (N)] administered concomitantly using the Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire –Revised (PPMQ-R).

Methods:

Adults with migraine (n = 50) without ‘medication overuse headache’ were treated for up to 18 migraine attacks per 3-month study period with study medication; SNC during one study period and S/N during the other study period. For all endpoints, differences between treatments were compared with paired t tests.

Results:

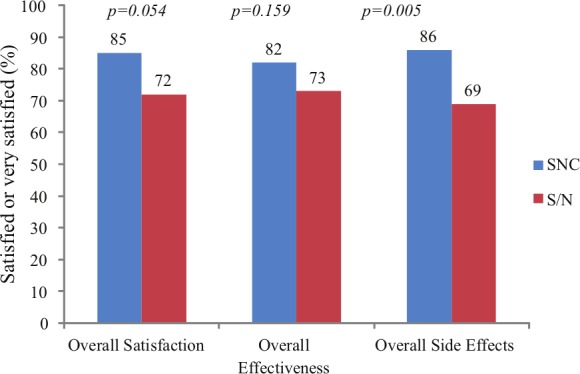

The percentage of patients reporting satisfied/very satisfied for Overall Satisfaction of SNC versus S/N (primary endpoint) was 85% versus 72% respectively (p = 0.054). For Overall Effectiveness, the results were 82% for SNC versus 73% for S/N (p = 0.159); and for Overall Side Effects the results were 86% for SNC versus 69% for S/N (p = 0.005). Mean PPMQ-R scores reflect greater satisfaction with SNC than S/N for Total score and for each of four subscales. The difference between SNC and S/N was significant for the Ease of Use subscale (p = 0.004) and met the criterion of being clinically meaningful for both the Total score and Ease of Use. SNC did not differ from S/N with respect to pain-free response 2 h post dose, pain relief 2 h post dose, sustained 24 h pain-free response, or sustained 24 h pain relief.

Conclusion:

Although the primary endpoint only just failed, the results of this pragmatic outcomes study demonstrate SNC to have benefits over its concomitantly administered components in the acute treatment of migraine.

Keywords: headache, migraine, naproxen sodium, patient treatment satisfaction, sumatriptan

Objective

Background

Sumatriptan/naproxen sodium is a combination tablet containing sumatriptan 85 mg formulated with RT Technology (GlaxoSmithKline, North Carolina) and naproxen sodium 500 mg for the acute treatment of migraine [Cleves and Tepper, 2008]. In two randomized, double-blind, phase III trials of 2956 patients with migraine, treating moderate or severe headache, the sumatriptan/naproxen sodium combination tablet (Treximet, GlaxoSmithKline, North Carolina, hereafter SNC) was superior to monotherapy with sumatriptan 85 mg or naproxen sodium 500 mg and to placebo with respect to 2 h pain relief, 2 h pain-free response, and 24 h sustained pain-free response [Brandes et al. 2007]. In addition, in a post hoc analysis of the phase III data, SNC was demonstrated to be superior to each monotherapy and to placebo with respect to the novel composite endpoint of sustained pain-free/no adverse events, which has been proposed as a more rigorous means of capturing, in a single measure, the attributes of migraine pharmacotherapy that patients consider most important [Landy et al. 2009]. SNC has also been demonstrated in clinical trials to be effective as an early intervention for migraine and in migraine subpopulations, including those with menstrual migraine and those who respond poorly to triptans alone [Silberstein et al. 2008; Mannix et al. 2009; Mathew et al. 2009] and to be more effective than placebo at improving patient satisfaction, increasing patient-reported workplace productivity, and reducing functional disability [Cady et al. 2011; Landy et al. 2007].

The tolerability profile of SNC in clinical trials is similar to that of the individual components administered separately [Brandes et al. 2007]. The efficacy and tolerability profiles of SNC are well established in clinical trials, but SNC has, to date, been virtually unstudied in pragmatic research. Pragmatic studies differ from randomized, placebo-controlled studies by their realistic representation. Pragmatic studies compare, in the clinical setting, the effectiveness and tolerability of interventions that are directly relevant to clinical care (rather than comparing active treatment to an inactive placebo); employ broad eligibility criteria to reflect the range of patients who actually receive the intervention in clinical practice; and otherwise manage participants in a manner that approximates usual clinical care [Ware and Hamel, 2011]. In short, the pragmatic study is designed to assess the performance of an intervention under the conditions that apply during its use in the real world and thereby overcome limitations of randomized, controlled clinical trials, which often fail to reflect the complexity of clinical practice [Ware and Hamel, 2011; Sullivan and Goldmann, 2011; Loder, 2011]. The need for pragmatic studies that complement and extend the results of conventional clinical trials to yield a comprehensive assessment of the therapeutic utility of interventions is increasingly being recognized [Ware and Hamel, 2011]. In particular, pragmatic outcomes studies, conducted with ‘clinical equipoise’ which emphasize outcomes assessed from the perspective and experience of the patient are recognized as being integral to providing information for healthcare decision-making [Krumholz, 2011; Freedman, 1987]. The primary objective of this pragmatic outcomes study is to compare, for the first time, SNC with its monotherapy components administered concomitantly [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01450995].

Pharmacokinetics

The unique pharmacokinetic properties of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium when administered as SNC may explain the greater efficacy and reduction of side effects with the combination tablet compared with its components in clinical trials. In pharmacokinetic studies, naproxen sodium from SNC compared with a single naproxen sodium tablet had a delayed time to peak plasma concentration and a lower peak plasma concentration [Haberer et al. 2010]. Moreover, while the sumatriptan peak plasma concentration and area under the concentration–time curve were similar between SNC and a single sumatriptan 100 mg tablet, sumatriptan time to peak plasma concentration occurred approximately 30 min earlier with SNC [Haberer et al. 2010]. The pharmacokinetics resulting in rapid absorption of sumatriptan coupled with the delayed release and lower peak plasma concentration properties of naproxen sodium from SNC may explain its increased efficacy and ‘blunting’ of side effects.

Methods

Men and women aged 18–65 years without ‘medication overuse headache’ were eligible for the study if they met International Headache Society criteria [Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society, 2004] for migraine headache with or without aura with a minimum of 1-year history of migraine and had, in the three months before enrollment, two to six migraine attacks per month and fewer than 15 headache days per month. Women could not be breastfeeding and were either not physiologically capable of bearing children or, if capable of bearing children, had a negative urine pregnancy test at screening and agreed to use an acceptable contraceptive method during the study. Exclusion criteria included confirmed or suspected ischemic heart disease, evidence or history of ischemic abdominal syndromes, peripheral vascular disease or Raynaud’s syndrome, cardiac arrhythmias requiring medication, history of cerebrovascular pathology or congenital heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension at screening or history of bleeding disorder, inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal ulceration (in the past 6 months), or gastrointestinal bleeding (in the past year). All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

The pragmatic, crossover, open-label outcomes study was conducted at Wesley Neurology and Headache Clinic, an outpatient headache clinic in Memphis, TN, USA. The protocol was approved by the Sterling Institutional Review Board in Atlanta, GA, USA. There were no changes to study methods or outcomes after trial commencement.

Fifty adult subjects with 25 subjects per group were included. No statistical methodology was used to obtain this sample. The first 25 subjects enrolled were assigned to treatment arm one of the study and received the study medication SNC. After 3 months of treatment with SNC, these 25 subjects crossed over to treatment arm two and began treatment with the monotherapy components, S/N, taken concomitantly for the next 3 months. The second 25 subjects enrolled began with treatment arm two, the monotherapy components S/N, taken concomitantly. After 3 months of treatment on arm two, these subjects crossed over to treatment arm one, SNC, for the subsequent 3 months of treatment.

The study included a screening visit and two 3-month treatment periods. During the screening visit, subjects completed the Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) [Kosinski et al. 2003]. Medical and migraine histories were obtained, and physical/neurological examinations were performed. Subjects were instructed to treat up to 18 migraine attacks per 3-month treatment period with study medication. Included with the study diaries were instructions regarding proper dosing of the study drug. In addition, subjects met with the study coordinator at each visit and received verbal instructions. Study medication was SNC during one of the study periods and the monotherapy components S/N taken concomitantly during the other study period. Subjects were instructed to treat attacks only if they had been free of migraine pain for at least 24 h before the treated attack; migraine pain was mild, moderate, or severe; at least 6 h had elapsed since medications for nausea, vomiting, or pain had been taken; at least 24 h had elapsed since any ergotamine-containing medication, dihydroergotamine, or a triptan had been taken. Subjects were permitted to take a second dose of SNC or S/N, dependent on the treatment arm, for persistent or recurring migraine pain at 2 h or more following the first dose.

During the treatment periods, subjects recorded information on their migraine attacks and migraine treatments in diaries and completed the Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire – Revised (PPMQ-R) at 24 h after taking the first dose of study medication for each migraine attack. The PPMQ-R has demonstrated reliability and validity in measuring patient satisfaction with acute migraine treatment [Revicki et al. 2006; Kimel et al. 2008]. The PPMQ-R contains items that contribute to four subscales: Bothersomeness of Side Effects (10 items), Efficacy (11 items), Functionality (4 items), and Ease of Use (2 items). The items contributing to the Efficacy, Functionality, and Ease of Use subscales are scored on a scale ranging from 1 (very satisfied) to 7 (very dissatisfied). The items contributing to the Bothersomeness of Side Effects subscale are scored on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all bothersome) to 5 (extremely bothersome). In addition to the items contributing to the Efficacy, Functionality, Ease of Use, and Bothersomeness of Side Effects subscales, the PPMQ-R contains three global satisfaction items, including Overall Satisfaction, Overall Effectiveness, and Overall Side Effects. The global satisfaction items are scored on a scale ranging from 1 (very satisfied) to 7 (very dissatisfied).

Subjects returned to the clinic at the end of each treatment period to return diaries and to pick up their new medication and diaries. At each study visit, vital signs were recorded and adverse events (defined as any untoward medical occurrences regardless of suspected cause) were assessed and recorded. The adverse events data were not summarized for this manuscript, although these events were evaluated in the ‘Bothersomeness of Side Effects’ subscale of the PPMQ-R.

In summarizing results on the PPMQ-R, scores for each global satisfaction item and the four subscales (Efficacy, Functionality, Ease of Use, and Bothersomeness of Side Effects) were calculated from item scores and transformed to scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction or tolerability. A Total score, the composite of the subscale scores for Efficacy, Functionality, and Ease of Use, was also computed [Revicki et al. 2006; Kimel et al. 2008]. The minimal clinically important difference for the Efficacy, Functionality, and Ease of Use subscales as well as the Total score is an increase of five points [Revicki et al. 2006]. The minimally clinical important difference has not been identified for the Bothersomeness of Side Effects subscale. Global satisfaction items (Overall Satisfaction, Overall Effectiveness, and Overall Side Effects) were summarized as the percentage of subjects satisfied/very satisfied with SNC versus S/N.

The primary endpoint was the Overall Satisfaction score of SNC versus S/N as measured by the proportion of migraine attacks per subject with an Overall Satisfaction score of very satisfied or satisfied comparing SNC with S/N. Secondary PPMQ-R-derived endpoints included the proportion of attacks per subject who scored as very satisfied/satisfied for the PPMQ-R Overall Effectiveness score and the Overall Side Effects score, the mean scores for each PPMQ-R subscale (Efficacy, Function, Ease of Use, and Bothersomeness of Side Effects), and PPMQ-R Total score across all migraine attacks for each subject. Endpoints derived from diary data included the proportion of migraine attacks per subject with pain-free response 2 h post dose; pain relief 2 h post dose; sustained 24 h pain-free response; sustained 24 h pain relief; and use of second dose of study medication. Pain-free response was defined as no pain. Pain relief was defined as migraine pain that was less than baseline pain. Sustained 24 h pain-free response and sustained 24 h pain relief were defined as pain-free response and pain relief respectively from 2 h to 24 h post dose with no use of additional medication. For all endpoints, differences between treatments were compared with paired t tests.

Results

Fifty subjects were enrolled from September 2009 to August 2010. Subjects were treated from December 2009 to May 2011 for up to 18 migraine attacks or 3 months per treatment arm. No additional follow up occurred. All subjects were assigned treatment based on enrollment, received the intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome. There were no losses after treatment assignment. Subjects’ mean age was 39.8 years [standard deviation (SD) = 11.2] (Table 1). Most subjects were women (90%) and white (92%) (Table 1). The mean HIT-6 score at baseline was 64.0 (SD = 6.0) (Table 2). HIT-6 scores fell within the range reflecting very severe impact of headaches in 84% of subjects, substantial impact in 10%, some impact in 4%, and no impact in 2% (Table 2). The proportion of migraine attacks per subject with a score of very satisfied or satisfied on the PPMQ-R was 85% for SNC versus 72% for S/N for Overall Satisfaction (p = 0.054); 82% for SNC versus 73% for S/N for Overall Effectiveness (p = 0.159); and 86% for SNC versus 69% for S/N for Overall Side Effects (p = 0.005) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and baseline characteristics for all subjects.

| Characteristic | All subjects |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| n | 50 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.8 (11.17) |

| Median | 39.0 |

| Min, max | 19, 60 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Men | 5 (10.0%) |

| Women | 45 (90.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 46 (92.0%) |

| Black | 3 (6.0%) |

| Asian | 1 (2.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 50 (100.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

| Migraine history, n (%) | |

| Migraine without aura | 34 (68.0%) |

| Migraine with aura | 7 (14.0%) |

| Both, migraine with/without aura | 9 (18.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

Denominators for percentages are based on the total number of subjects.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Summary of Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) for all subjects.

| HIT-6 | All subjects |

|---|---|

| Score summary | |

| N | 50 |

| Mean (SD) | 64.0 (5.96) |

| Median | 63.0 |

| Min, max | 46, 78 |

| Score impact summary, n (%) | |

| No impact | 1 (2.0%) |

| Some impact | 2 (4.0%) |

| Substantial impact | 5 (10.0%) |

| Very severe impact | 42 (84.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

| When you have headaches, how often is the pain severe? | |

| Never | 0 (0.0)% |

| Rarely | 3 (6.0%) |

| Sometimes | 18 (36.0%) |

| Very often | 23 (46.0%) |

| Always | 6 (12.0%) |

| Total | 50 |

Denominators for percentages are based on the total number of subjects.

SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Proportion of attacks per subject with a score of very satisfied or satisfied for Overall Satisfaction, Overall Effectiveness, and Overall Side Effects.

Mean PPMQ-R scores reflected numerically greater satisfaction with SNC than S/N for the Total score and for each of the four subscales (Table 3). The difference was statistically significant for the Ease of Use subscale (p = 0.004) (Table 3). The difference between SNC and S/N exceeded the five-point minimally clinically important difference [Revicki et al. 2006] for the PPMQ-R Total score and the Ease of Use subscale (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perception of Migraine Questionnaire – Revised results: mean scores.

| SNC (n = 50) | S/N (n = 50) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 86.7 (14.3) | 81.7 (15.3) | 0.07 |

| Efficacy subscale | 83.1 (17.5) | 80.0 (17.1) | 0.34 |

| Ease of use subscale | 94.9 (9.5) | 87.3 (15.3) | 0.004 |

| Functionality subscale | 82.1 (19.2) | 77.7 (19.0) | 0.16 |

| Bothersomeness of side effects subscale | 93.2 (11.6) | 90.0 (13.2) | 0.14 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Based on paired t test for SNC versus S/N.

S/N, monotherapy components of S and N; SNC, sumatriptan/naproxen sodium combination tablet.

SNC did not statistically significantly differ from S/N with respect to the diary-derived endpoints, including pain-free response 2 h post dose, pain relief 2 h post dose, sustained 24 h pain-free response, sustained 24 h pain relief, and use of a second dose of study medication (Table 4). There were no significant concerns in the number and severity of reported adverse events.

Table 4.

Results for diary-derived endpoints.

| SNC (n = 50) | S/N (n = 50) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain relief 2 h | 87 (20) | 83 (21) | 0.22 |

| Pain-free response 2 h | 61 (35) | 60 (37) | 0.91 |

| Sustained 24 h pain relief | 69 (30) | 66 (32) | 0.56 |

| Sustained 24 h pain-free response | 50 (34) | 50 (37) | 0.96 |

| Second dose taken | 22 (25) | 19 (25) | 0.43 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) % of headaches per patient.

Based on paired t test for SNC versus S/N.

S/N, monotherapy components of S and N; SNC, sumatriptan/naproxen sodium combination tablet.

Discussion

In their May 2011 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, ‘Pragmatic trials – guides to better patient care?’, Ware and Hamel note that randomized clinical trials provide the necessary information about the efficacy and tolerability of interventions as used under the conditions of the trials but often lack generalizability to clinical practice [Ware and Hamel, 2011]. Pragmatic studies, when interpreted with knowledge of their strengths and limitations, can provide a more clinically meaningful assessment of interventions as they perform in the real world. Pragmatic outcomes studies, conducted with clinical equipoise, emphasize outcomes assessed from the perspective and experience of the patient and are crucial for informed healthcare decisionmaking [Krumholz, 2011; Freedman, 1987]. This study constitutes the first published comparative, pragmatic, outcomes investigation of SNC versus S/N, its monotherapy components taken concomitantly. The study was conducted with the aim of simulating a realistic comparison. Subjects were monitored and instructed in a manner consistent with usual clinical practice. Further, subjects could choose the time of self medication and could receive treatment at any degree of headache pain (to simulate practical medication use) rather than taking medication only for headaches of a specified intensity as is common in controlled clinical trials [Edmeads, 2005]. Correspondingly, headache response was not defined as a conventional measure of reduction in pain, such as from moderate or severe to mild or none, but instead, as any degree of pain reduction of predose pain (headache relief) or as reduction of any degree of predose pain to no pain (headache free).

S and N were taken concomitantly in this study to approximate a clinically meaningful comparison with the combination tablet. Both sumatriptan and naproxen sodium are available as generic and branded products. To avoid concerns about bioequivalent inconsistencies, branded Imitrex (GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA, USA), formulated with RT Technology, and branded over-the-counter Aleve (Bayer HealthCare, Morristown, NJ, USA) were chosen as comparators. The Imitrex dose and technology (RT) approximates that of the SNC combination as closely as possible. Likewise, Aleve (two Aleve tablets for a total of 440 mg naproxen sodium per attack) was chosen as the closest available comparator to naproxen sodium in SNC.

The results show that the proportion of migraine attacks per patient with a score of very satisfied or satisfied was higher with SNC than with S/N for Overall Satisfaction (p = 0.054), the primary endpoint, Overall Effectiveness (p = 0.159), and Overall Side Effects (p = 0.005). These differences were statistically significant for Overall Side Effects and only just failed to be statistically significant for Overall Satisfaction. The unique pharmacokinetic profile of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium when administered as SNC may help to explain the increased satisfaction of the combination tablet compared with its components in this trial.

In addition, mean PPMQ-R scores reflected greater satisfaction with SNC than S/N for the Total score, meeting the criteria of a minimally clinical important difference [Revicki et al. 2006]. Greater satisfaction was also reflected in each Total score subscale.

Although intuitive, that taking one combination tablet compared with three individual tablets as was the case with S/N, the difference between SNC and S/N was statistically significant for the Ease of Use subscale and also met the criteria of a minimally clinical important difference [Revicki et al. 2006].

SNC did not statistically significantly differ from S/N with respect to conventional clinical trial pain measurement endpoints, including pain-free response 2 h post dose, pain relief 2 h post dose, sustained 24 h pain-free response, and sustained 24 h pain relief. The latter results differ from those of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in which SNC produced a reduction in pain outcomes superior to those with either of its components [Brandes et al. 2007]. This inconsistency may be explained by the fact that, in the pivotal trials and other previous comparative trials of SNC, S and N were taken as monotherapy and each of the individual drugs, taken alone, were compared with SNC. In contrast, during this study, the component drugs were taken concomitantly rather than as monotherapy.

While pragmatic studies such as this one may better represent clinical practice than randomized, controlled clinical trials, this study’s primary limitations are its open-label design, which exposes both its conduct and analysis to various biases, and its ability to make inferences about cause and effect in the absence of a blinded experimental intervention. In addition, the cost of SNC compared with S/N and the impact on the endpoints analyzed were not considered. In aggregate, the results of pragmatic studies and randomized, controlled clinical trials help to yield a comprehensive assessment of the benefits and risks of interventions.

Conclusion

The results of this pragmatic outcomes research demonstrate SNC to have satisfaction benefits over its concomitantly administered components in the acute treatment of migraine.

Acknowledgments

The authors contributed to this study as follows. Stephen Landy, MD: principal investigator, conception and design of study, acquisition of data, patient recruitment, literature search, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript; Rebecca Hoagland, MS: literature search, study design, analysis and statistical evaluation of data, drafting the manuscript, preparation of figures and tables, revision of manuscript, final approval of the completed manuscript; Dakota Hoagland, BS: analysis and statistical evaluation of data, drafting the manuscript, revision of manuscript, final approval of completed manuscript. Jane Saiers, PhD: medical writer, drafting the manuscript; Gena Reuss, MBA: acquisition of data, patient recruitment, revision of manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: GlaxoSmithKline provided funding for the study. GlaxoSmithKline had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and/or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: Stephen H. Landy, MD received funding for this study from GlaxoSmithKline. Rebecca Hoagland, Dakota Hoagland, Jane Saiers and Gena Reuss have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Stephen Landy, Wesley Neurology and Headache Clinic, University of Tennessee Medical School, 8000 Centerview Parkway, Suite 101, Memphis, TN 38018, USA.

Rebecca Hoagland, Cota Enterprises, Meriden, KS, USA.

Dakota Hoagland, Cota Enterprises, Meriden, KS, USA.

Jane Saiers, The WriteMedicine, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Gena Reuss, Wesley Neurology and Headache Clinic, Memphis, TN, USA.

References

- Brandes J., Kudrow D., Stark S., O’Carroll C., Adelman J., O’Donnell F., et al. (2007) Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine: a randomized trial. JAMA 297: 1443–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady R., Diamond M., Diamond M., Ballard J., Lener M., Dorner D., et al. (2011) Sumatriptan-naproxen sodium for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea: satisfaction, productivity, and functional disability outcomes. Headache 51: 664–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleves C., Tepper S. (2008) Sumatriptan/naproxen sodium combination for the treatment of migraine. Expert Rev Neurother 8: 1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmeads J. (2005) Defining response in migraine: which endpoints are important? Eur Neurol 53(Suppl. 1): 22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman B. (1987) Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 317: 141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer L., Walls C., Lener S., Taylor D., McDonald S. (2010) Distinct pharmacokinetic profile and safety of a fixed-dose tablet of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium for the acute treatment of migraine. Headache 50: 357–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2004) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed Cephalalgia 24(Suppl. 1): 9–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimel M., Hsieh R., McCormack J., Burch S., Revicki D. (2008) Validation of the revised Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire (PPMQ-R): measuring satisfaction with acute migraine treatment in clinical trials. Cephalalgia 28: 510–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M., Bayliss M., Bjorner J., Ware J., Jr, Garber W., Batenhorst A., et al. (2003) A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 12: 963–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz H. (2011) Real-world imperative of outcomes research. JAMA 306: 754–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landy S., DeRossett S., Rapoport A., Rothrock J., Ames M., McDonald S., et al. (2007) Two double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-dose studies of sumatriptan/naproxen sodium in the acute treatment of migraine: function, productivity, and satisfaction outcomes. MedGenMed 9: 53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landy S., White J., Lener S., McDonald S. (2009) Fixed-dose sumatriptan/naproxen sodium compared with each monotherapy utilizing the novel composite endpoint of sustained pain-free/no adverse events. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2: 135–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder E. (2011) Manual therapy versus usual GP care for chronic tension-type headache: we now have better evidence, but important questions remain. Cephalalgia 31: 131–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannix L., Martin V., Cady R., Diamond M., Lener S., White J., et al. (2009) Combination treatment for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea using sumatriptan-naproxen: two randomized controlled studies. Obstet Gynecol 114: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew N., Landy S., Stark S., Tietjen G., Derosier F., White J., et al. (2009) Fixed-dose sumatriptan and naproxen in poor responders to triptans with a short half-life. Headache 49: 971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki D., Kimel M., Beusterien K., Kwong J., Varner J., Ames M., et al. (2006) Validation of the revised Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire: measuring satisfaction with acute migraine treatment. Headache 46: 240–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S., Mannix L., Goldstein J., Couch J., Byrd S., Ames M., et al. (2008) Multimechanistic (sumatriptan-naproxen) early intervention for the acute treatment of migraine. Neurology 71: 114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P., Goldmann D. (2011) The promise of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA 305: 400–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J., Hamel M. (2011) Pragmatic trials – guides to better patient care? N Engl J Med 364: 1685–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]