Abstract

We describe a family illustrating the diagnostic difficulties occurring when pyridoxine-responsive cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) deficiency presents with thrombotic disease without associated ocular, skeletal, or CNS abnormalities, a situation increasingly recognized. This family had several thromboembolic episodes in two generations with apparently inconstant elevations of plasma total homocysteine (tHcy). When taking (sometimes even low amounts) of pyridoxine, the affected family members had low-normal tHcy and normal values for cystathionine, methionine, and cysteine. Withdrawal of vitamin therapy was necessary before lower cystathionine, elevated methionine, and decreased cysteine became apparent, a pattern suggestive of CBS deficiency, leading to the finding that the affected members were each compound heterozygotes for CBS p.G307S and p.P49L. To assist more accurate diagnosis of adults presenting with thrombophilia found to have elevated tHcy, the patterns of methionine-related metabolites in CBS-deficient patients are compared in this article to those in patients with homocysteine remethylation defects, including inborn errors of folate or cobalamin metabolism, and untreated severe cobalamin or folate deficiency. Usually serum cystathionine is low in subjects with CBS deficiency and elevated in those with remethylation defects. S-Adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine are often markedly elevated in CBS deficiency when tHcy is above 100 umol/L. We conclude that there are likely other undiagnosed, highly B6-responsive adult patients with CBS deficiency, and that additional testing of cystathionine, total cysteine, methionine, and S-adenosylmethionine will be helpful in diagnosing them correctly and distinguishing CBS deficiency from remethylation defects.

Introduction

In this article, we report the clinical and metabolic findings for a family with four members in two generations with elevated levels of tHcy among whom more than three thromboembolic events occurred before it was found that they are each compound heterozygotes for mutations in the gene that encodes CBS. This history raises two important interrelated issues: (a) Why did these patients go so long without a specific diagnosis? (b) What steps might be taken to improve the ability to determine the cause of abnormally high tHcy? To address these issues, after presenting the facts about the family reported upon, we discuss the several limitations that played a role in delaying their diagnoses, present a compilation of the results of assays of not only tHcy and methionine, but also cystathionine, S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy) in a variety of patients with elevated levels of tHcy, then discuss how these compiled metabolite results may be useful in providing criteria for the differential diagnosis of elevated tHcy.

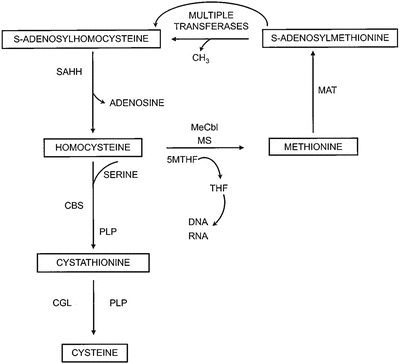

Figure 1 outlines the relevant pathways of homocysteine and methionine metabolism (Mudd 2011). Homocysteine is at a branch point and can be remethylated to methionine by a folate and cobalamin (vitamin B12)-dependent enzyme, methionine synthase (MS, EC 2.1.1.13), or condensed with serine to form cystathionine by the pyridoxal phosphate (B6)-dependent enzyme CBS (EC 4.2.1.22). Cystathionine is cleaved by cystathionine gamma-lyase (EC 4.4.1.1) to form cysteine. Methionine can be converted to AdoMet, the donor in many important transmethylation reactions, including the formation of N-methylglycine (sarcosine). The resulting AdoHcy is hydrolyzed to homocysteine by S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (EC 3.3.1.1). The alternate remethylation of homocysteine using betaine as a donor of the methyl group, is not shown, but may be exploited as an effective homocysteine lowering treatment (Mudd 2011).

Fig. 1.

Pathways of methionine and homocysteine metabolism are shown. Homocysteine is methylated to methionine by methionine synthase (MS) with methyl-cobalamin (Me-Cbl). 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) is demethylated to tetrahydrofolate (THF) in this reaction. Methionine is activated to S-adenosylmethionine by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT). Multiple transferases utilize S-adenosylmethionine producing S-adenosylhomocysteine in the reactions, which can be hydrolyzed to homocysteine and adenosine by S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (SAHH). Homocysteine can be condensed with serine by the pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) to form cystathionine. Cystathionine is cleaved by another PLP-dependent enzyme, cystathionine gamma-lyase (CGL) forming cysteine

Case Report

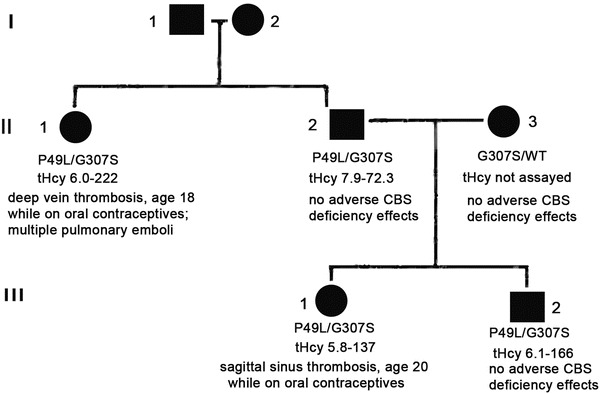

A 55-year-old female of Northern European and Irish ancestry had presented with a deep venous thrombosis at age 18 while on oral contraceptives. She had had multiple pulmonary emboli by age 45. For more than 10 years, tHcy had been known to be at times elevated, ranging from 16 to 186 umol/L, assayed in clinical labs and on varying vitamin regimens. Both methylmalonic acid and methionine had been assayed and said to be normal on several occasions. The subject had no ocular, skeletal, or other physical or cognitive findings suggestive of CBS deficiency. Fibroblast assay had been negative for severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency in the past. Her brother, age 52 years and asymptomatic, according to historical detail had been found to have elevated tHcy of 80 umol/L. He also had normal values on unknown vitamin regimens. His daughter, the 26-year-old niece of the proband, had a sagittal sinus thrombosis with left parietal infarct at age 20 while on oral contraceptives. Her tHcys had been as high as 137 umol/L in the past. Her brother, the 21-year-old nephew of the proband, was asymptomatic but had a documented tHcys value of 166 umol/L. Values of methionine metabolites and vitamin treatments, if known, are shown in Table 1. As will be covered in more detail in the “Discussion,” only when the proband and her brother discontinued all vitamin supplements did metabolite patterns indicative of CBS deficiency become apparent. The four affected family members and the wife of the brother, the mother of the affected niece and nephew, were then analyzed for CBS mutations. The proband, brother, niece, and nephew were each compound heterozygotes for CBS mutations p.G307S and p.P49L; the mother of the niece and nephew, a p.G307S carrier. A pedigree of the case family is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Metabolic values, vitamin treatment, and symptoms in case family members

| Index case | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tHcy | Met | Cysta | tCys | AdoMet | AdoHcy | Vitamin treatment | |||||

| Age (y) | (umol/L) | (umol/L) | (nmol/L) | (umol/L) | (nmol/L) | (nmol/L) | B6 | B12 | Folate | Comments to treatment | Symptoms |

| 42 | (102.1)* | Unknown | DVT age 18 | ||||||||

| (32.9) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| 43 | (186) | Unknown | |||||||||

| 44 | (67.8) | Unknown | |||||||||

| (20.4) | Post B12 injection 24 h | ||||||||||

| (23.1) | Post B12 injection 48 h | ||||||||||

| (68) | PE age 45 | ||||||||||

| 46 | (12.2) | (21) | Unknown | ||||||||

| 50 | (9.4) | (21) | |||||||||

| 51 | (18) | ||||||||||

| 6 | 20 | 74 | 311 | 118 | 8 | 100 mg | 100 mcg | 400 mcg | MVI also | ||

| 52 | (176.8) | Unknown | |||||||||

| (124.2) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| 53 | (184.4) | Unknown | |||||||||

| (33.6) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| (66.6) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| (35.8) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| (92.9) | Unknown | ||||||||||

| 11.7 | 22.5 | 128 | 363 | 69 | 38 | 2 mg | Decrease B6 from 100 to 2 mg × 2 days | ||||

| 49.1 | 47.2 | 210 | 327 | 137 | 20 | 2 mg | 2 mg × 7 days (from 100 mg) | ||||

| (71.1) | (39) | Off all vitamins × 26 days | |||||||||

| 67.8 | 35 | 139 | 253 | 169 | 33.9 | Off all vitamins × 45 days | |||||

| 222 | 135 | 135 | 133 | 1282 | 1539 | Off all vitamins × 53 days | |||||

| (10.4) | (13.4) | 100 mg | |||||||||

| Brother | |||||||||||

| 43 | (7.9) | (31) | Unknown | None | |||||||

| (12.2) | (34) | ||||||||||

| 48 | 8.6 | 28.9 | 136 | 245 | 98 | 8 | 2 mg | 15 mcg | 400 mcg | MVI | |

| 51 | 72.3 | 63.3 | 295 | 245 | 657 | 78 | Off all vitamins × 55 days | ||||

| 15.7 | 27.8 | 208 | 326 | 115 | 21 | Off all vitamins × 62 days | |||||

| 22.1 | 42.5 | 204 | 317 | 210 | 61 | Off all vitamins × 70 days | |||||

| 52 | (14) | 100 mg | |||||||||

| Nephew | |||||||||||

| 16 | (166) | Unknown | None | ||||||||

| 17 | (59) | ||||||||||

| 6.1 | 26.1 | 102 | 236 | 96 | 7 | ? | 1 mg | 1 mg | |||

| Niece | |||||||||||

| 21 | 5.8 | 27.7 | 99 | 242 | 62 | 12 | 100 mg | 500 mcg | 1 mg | Sagittal sinus thrombosis and left parietal infarction at age 20 of treatment | |

| 24 | (137) | None | |||||||||

| (13) | 50 mg | ||||||||||

| 25 | (24) | 100 mg | |||||||||

Reference range (5–14) (13–45) (44–342) (200–361) (71–168) (8–26)

DVT deep venous thrombosis, PE pulmonary embolism, MVI multivitamin

*Values in parentheses assayed elsewhere, usually commercial clinical laboratory

Fig. 2.

The pedigree is shown for the case family. The proband is shown as II-1; her brother, II-2; and brother’s wife, II-3. The proband’s niece is III-1 and nephew, III-2

Methods

Methylmalonic acid, 2-methylcitric acid, tHcy, cystathionine, methionine, and total cysteine were assayed in serum or plasma by capillary stable isotope dilution gas chromatography/mass spectrometry as previously described (Stabler et al. 1988, 1993). AdoMet and AdoHcy were assayed in serum or plasma either by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (Stabler and Allen 2004) or by HPLC separation of naphthalene dialdehyde derivatives with fluorescent detection (Capdevila and Wagner 1998).

The values for metabolites shown in Tables 2–4 and the figures were compiled from samples assayed for diagnosis and treatment of inborn errors and for previously reported cohorts of patients with CBS deficiency or remethylation defects (Stabler et al. 1988; Stabler et al. 1993; Allen et al. 1993; Savage et al. 1994; Tangerman et al. 2000; Mudd et al. 2001; Yaghmai et al. 2002; Stabler et al. 2002; Maclean et al. 2002; Orendäc et al. 2003; Stabler and Allen 2004; Guerra-Shinohara et al. 2007; Strauss et al. 2007; Keating et al. 2011). The group with remethylation defects includes inborn errors of cobalamin metabolism, such as cblC or cblD disorders, defects of methionine synthase or methionine synthase reductase, or severe deficiency of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (not the thermolabile C.677C>T polymorphism) (47 samples), or clinically symptomatic cobalamin or folate-deficient patients with megaloblastic anemia and/or neurologic disease (85 samples). All subjects with cobalamin deficiency or cblC defects also had elevated methylmalonic acid. Many subjects had multiple sample determinations on various treatment regimens such as methionine-restricted diets, with or without cysteine replacement, B6 and/or other vitamin supplements, or administration of betaine. For patients with CBS deficiency or the inborn errors of remethylation, data both for periods of treatment and for no treatment are shown in the Results section, whereas for subjects with cobalamin or folate deficiency, values are shown only for periods of no treatment. The different studies were reviewed by relevant institutional review boards (see references above) as well as the University of Colorado School of Medicine. The numbers of values for CBS-deficient samples were as follows: tHcy – 117, cystathionine – 116, methionine – 118, total cysteine – 100, AdoMet – 40, and AdoHcy – 37. The numbers of values for remethylation defects were as follows: tHcy – 132, cystathionine – 131, methionine – 121, total cysteine – 119, AdoMet – 28, and AdoHcy – 28. All six values were available for 49 samples from adult controls (Stabler and Allen 2004).

Table 2.

Median (range) metabolites* in untreated vs. treated CBS deficiency

| Untreated CBS | Treated CBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 25 | N = 93 | Sig** | ||

| tHcy (umol/L) | (Median) | 125.0 | 119.0 | NS |

| (Range) | (15.7–281.4) | (4.8–312) | ||

| Cystathionine (nmol/L) | (Median) | 78 | 25 | 0.004 |

| (Range) | (25–295) | (25–357) | ||

| Methionine (umol/L) | (Median) | 135 | 160 | NS |

| (Range) | (27.8–1,595) | (11.7–2,823) | ||

| Total cysteine | (Median) | 124 | 138 | NS |

| (Range) | (40–326) | (40–363) | ||

| AdoMet (nmol/L) | (Median) | 804 | 446 | NS |

| (Range) | (115–1,282) | (62–1,130) | ||

| AdoHcy (nmol/L) | (Median) | 160 | 56 | NS |

| (Range) | (21–1,539) | (7–530) | ||

| AdoMet/AdoHcy (ratio) | (Median) | 3.7 | 3.8 | NS |

| (Range) | (0.8–8.6) | (1.5–16.4) |

*See methods for actual number of values of each metabolite

**Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test <0.05 was significant

Table 4.

Median (interquartile range) of metabolites and ratios in CBS deficiency vs. remethylation defects, controls, and case family

| CBS Def | Remethylation defects | Controls | Family | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 118* | N = 132* | Sig** | N = 49 | ANOVA*** | N = 6b | Siga | ||

| tHcy (umol/L) | Median | 124.8 | 79.4 | <0.001 | 7.4 | <0.001 | 58.4 | NS |

| (25–75 %) | (68.9–166.8) | (53.0–108.4) | (6.3–9.2) | (15.7–222) | ||||

| Cysta (nmol/L) | Median | 40c | 839 | <0.001 | 157c | <0.001 | 206 | <0.001 |

| (25–75 %) | (25–76) | (471–1,248) | (121–198) | (135–295) | ||||

| Met (umol/L) | Median | 160 | 18.6c | <0.001 | 22.4c | <0.001 | 44.8 | 0.004 |

| (25–75 %) | (47–813) | (13.4–28.7) | (18.6–27) | (27.8–135.0) | ||||

| tCys (umol/L) | Median | 136 | 221 | <0.001 | 289 | <0.001 | 285 | NS |

| (25–75 %) | (77–201) | (177–262) | (262–318) | (133–327) | ||||

| AdoMet (nmol/L) | Median | 488 | 104c | <0.001 | 107c | <0.001 | 189 | 0.011 |

| (25–75 %) | (155–868) | (93–159) | (93–121) | (115–1,282) | ||||

| AdoHcy (nmol/L) | Median | 73 | 38c | 0.008 | 14c | <0.001 | 48 | NS |

| (25–75 %) | (24–382) | (25–49) | (12–18) | (20–1,539) | ||||

| AdoMet/AdoHcy (ratio) | Median | 3.8c | 3.2c | NS | 7.1 | 0.015 | 5.2 | 0.039 |

| (25–75 %) | (1.8–8.9) | (2.3–4.3) | (6.4–9.0) | (0.8–8.41) | ||||

| tHcy/Cysta (ratio) | Median | 2.8 | 0.1c | <0.001 | 0.05c | <0.001 | 0.2 | NS |

| (25–75 %) | (1.1–4.8) | (0.06–0.18) | (0.04–0.06) | (0.08–1.60) | ||||

| tHcy/Met (ratio) | Median | 0.5c | 3.8 | <0.001 | 0.4c | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.004 |

| (25–75 %) | (0.2–1.5) | (2.0–7.6) | (0.3–0.4) | (0.5–1.9) | ||||

| Cysta/Met (ratio) | Median | 0.2c | 46.0 | <0.001 | 6.6c | <0.001 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| (25–75 %) | (0.05–1.0) | (19.7–85.7) | (5.6–9.3) | (1.0–7.5) | ||||

| Met/tCys (ratio) | Median | 1.5 | 0.09c | <0.001 | 0.08c | <0.001 | 0.1 | 0.013 |

| (25–75 %) | (0.2–6.9) | (0.06–0.13) | (0.06–0.09) | (0.09–1.0) | ||||

| tHcy/tCys (ratio) | Median | 1.0 | 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001d | 0.2 | NS |

| (25–75 %) | (0.3–1.7) | (0.2–0.5) | (0.02–0.03) | 0.019d | (0.5–1.7) | |||

| tCys/Cysta (ratio) | Median | 2.6 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 1.8 | <0.001 | 1.6 | <0.001 |

| (25–75 %) | (1.6–4.2) | (0.1–0.4) | (1.5–2.4) | (0.8–1.8) |

*See Methods for actual number of values of each metabolite since some metabolites had missing values comparing CBS deficiency vs. remethylation defects

**Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test <0.05 was significant for CBS deficiency vs. remethylation defects

***,cANOVA – For a given metabolite or ratio, values sharing a superscript are not significantly different from each other. (Case family values not included due to small “N”). Significance for the multiple comparisons shown for CBS deficiency vs. remethylation defects vs. controls. Post hoc test shown; Scheffe

aIndependent samples Mann-Whitney U test <0.05 was significant for remethylation defects vs. the family when tHcy ≥14umol/L

bMedian and actual range of values from samples when tHcys ≥14 umol/L

dSignificance for CBS deficiency vs. remethylation defects vs. controls <0.001, for remethylation defects vs. controls, 0.019

The testing for CBS mutations in the case family was performed by the University of Colorado DNA Diagnostics Laboratory by PCR amplification and bidirectional DNA sequencing of all 16 coding exons and the exon/intron borders. The reference sequence was NM 000071.1. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Version 19 and < 0.05 was considered significant. To compare two groups, the independent samples Mann-Whitney U test was used. For more than two groups, ANOVA was used with the Scheffe post hoc test for significance.

Results

Family Metabolite Values

As shown in Table 1, when taking supplemental vitamin B6, the proband and the three other members of her family with genetically proven CBS deficiency each had normal values for methionine and methionine metabolites. B6 doses as low as 2 mg/day were enough, on occasion, to normalize tHcy. When the dose of B6 for the proband was decreased from 100 to 2 mg/day, tHcys rose from 11.7 to 49.1 umol/L and methionine doubled from 23 to 47 umol/L. When she was withdrawn from all B6 supplements, tHcy rose after almost 2 months to 222 umol/L. By that time her other metabolites had developed a pattern very suggestive of CBS deficiency with cystathionine relatively low, total cysteine below the normal range, and methionine elevated. Serum S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy) rose to 1,282 and 1,539 nmol/L, 7.6 and 50 times the upper limits of their reference ranges. When the brother was taken off vitamins his tHcy initially rose, as did methionine, AdoMet, and AdoHcy, but cystathionine and total cysteine remained normal. Subsequently, for reasons that are not clear, the elevations of tHcy and methionine diminished.

Compiled Metabolite Values for Other Patients with Either CBS Deficiency or Remethylation Defects

To extend the information available on the metabolites relevant to abnormally elevated tHcy, values obtained for patients assayed in association with previous reports from the authors’ laboratories were gathered and combined into Tables 2–4 and Figs. 3–7. In Table 2 median (range) values for the metabolites are shown for the CBS-deficient samples obtained off treatment (N = 25) as compared to these obtained on standard treatments (N = 93). The only statistically different value was that for cystathionine which, unexpectedly, was higher in the untreated group.

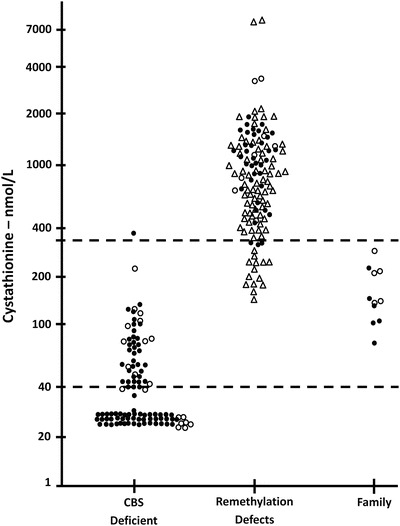

Fig. 3.

Values of serum or plasma cystathionine are shown for CBS-deficient patients, those with remethylation defects and the case family subjects. A previously determined reference range is shown by the dotted lines (44–342 nmol/L). Many subjects with CBS deficiency had cystathionine levels below the limits of detection and they are arbitrarily shown as 25 nmol/L. Closed symbols denote treated patients, open symbols untreated patients. For remethylation disorders, triangles denote acquired cobalamin or folate deficiency, circles denote congenital remethylation defects

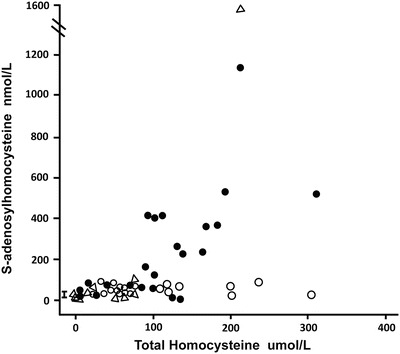

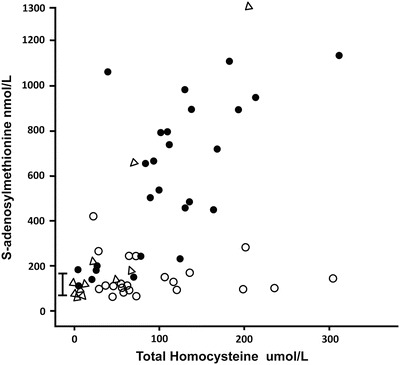

Fig. 7.

The serum or plasma total homocysteine is shown plotted against the plasma or serum S-adenosylhomocysteine values in the three groups of patients. The reference range is shown by the bar, 8–26 nmol/L. The patients with CBS deficiency are shown as closed circles, those with remethylation defects with open circles, and the case family members as open triangles

Table 3 shows values in the congenital remethylation disorders comparing the untreated (N = 8) vs. treated (N = 39). THcy was higher and AdoMet was lower without treatment, but cystathionine and methionine were not different. Table 3 also shows that values in the group with acquired vitamin deficiency were very similar to those with congenital defects.

Table 3.

Metabolite values* (median, range) in congenital disorders of remethylation (N = 47) vs. acquired vitamin B12 or folate deficiency (N = 85)

| Congenital remethylation defects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | |||||||

| No | Yes | ||||||

| Total | (N = 8) | (N = 39) | Sig** | Acquired vitamin deficiency | Siga | ||

| tHcy (umol/L) | (Median) | 66.0 | 130.5 | 62.7 | 0.008 | 80.8 | NS |

| (Range) | (21.3–303) | (55–241) | (21.3-303) | (17.1–254.4) | |||

| Cystathionine (nmol/L) | (Median) | 1,032 | 1,192 | 1,005 | NS | 656 | 0.004 |

| (Range) | (304–3,439) | (434–3,439) | (304–1,963) | (145–7923) | |||

| Methionine (umol/L) | (Median) | 18.0 | 14.8 | 19.8 | NS | 18.7 | NS |

| (Range) | (3.7–88.0) | (6.0–27.0) | (3.7–88.0) | (6.5–315) | |||

| Total cysteine (umol/L) | (Median) | 184 | 142 | 190 | NS | 242 | <0.001 |

| (Range) | (75–328) | (91–213) | (75–328) | (78–816) | |||

| AdoMet (nmol/L) | (Median) | 108 | 86 | 124 | 0.020 | 100 | NS |

| (Range) | (49–421) | (49–186) | (93–421) | (65–234) | |||

| AdoHcy (nmol/L) | (Median) | 26 | 22 | 28 | NS | 44 | 0.009 |

| (Range) | (15–80) | (16–51) | (15–80) | (26–66) | |||

| AdoMet/AdoHcy (ratio) | (Median) | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.9 | NS | 2.5 | 0.005 |

| (Range) | (1.2–16.8) | (1.5–5.8) | (1.2–16.8) | (1.5–4.0) | |||

NS Not significant

*See methods for actual number of values since fewer results were available for some metabolites

**Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test <0.05 was significant for treated vs. untreated congenital remethylation defects

aIndependent samples Mann-Whitney U test <0.05 was significant for congenital remethylation defects vs. acquired vitamin deficiency

Because there were either no or only minor differences in these metabolites due to treatment of the genetic remethylation defects, and because the differences between the remethylation defects and acquired vitamin deficiencies were also minor, these groups were all combined in Table 4 as a single remethylation group for comparison with values from controls and from the case family members when tHcy was elevated (>14 umol/L). The results for each metabolite are as follows:

tHcy

The median tHcys was higher in CBS deficiency than in those with remethylation defects, 124.8 vs. 79.4 umol/L, but the 25–75 % interquartile ranges were very similar, that is, 68.9–166.8 vs. 53.0–108.4 umol/L, respectively. Thus, any specific value of tHcy cannot be used to distinguish between these two types of defects.

Cystathionine

The median cystathionine for CBS-deficient persons was 40 compared to 839 nmol/L for those with remethylation defects (0.001). As shown in Fig. 3, serum cystathionine showed an almost complete separation between these conditions despite the treated status of many of the patients. Figure 3 shows also that about 50 % of those with CBS deficiency had cystathionine values too low to be accurately measured by the method used. Such values are shown arbitrarily as 25 nmol/L, the value used in the statistical calculations. Even the two CBS-deficient subjects (not case family members) with tHcy in the reference range had cystathionine too low to be reliably measured. There were 19 subjects with remethylation defects who presented with elevated tHcys and who also had simultaneous cystathionine values in the reference range, but the median value was markedly higher at 241 nmol/L than the median for the 102 CBS-deficient subjects with elevated tHcy, 25 nmol/L (<0.001).

Methionine

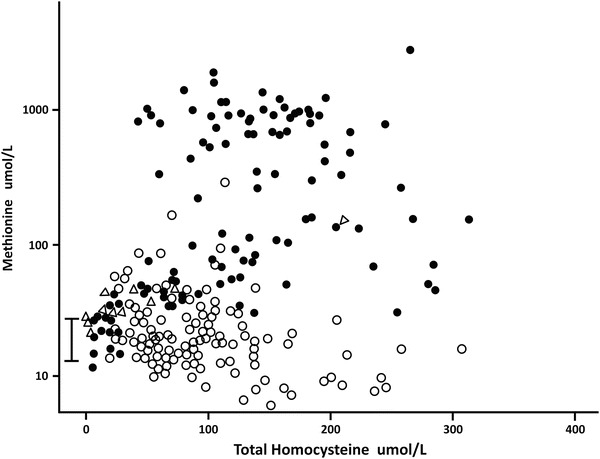

The median methionine value was much higher in the CBS-deficient individuals than in those with remethylation defects, 160 vs. 18.6 umol/L (<0.001). However, as shown in the plot of methionine against tHcy (Fig. 4), when tHcy is low there is some overlap between the two groups. As tHcy increases to over 100 umol/L, the methionine values in CBS-deficient subjects increase markedly and overlap little with the levels for remethylation disorders.

Fig. 4.

The serum or plasma total homocysteine is plotted against the serum or plasma methionine in three groups of patients. The reference range of serum methionine is shown by the bar, 14–43 umol/L. Patients with CBS deficiency are shown as closed circles, patients with remethylation defects are open circles. The case family members are shown as open triangles

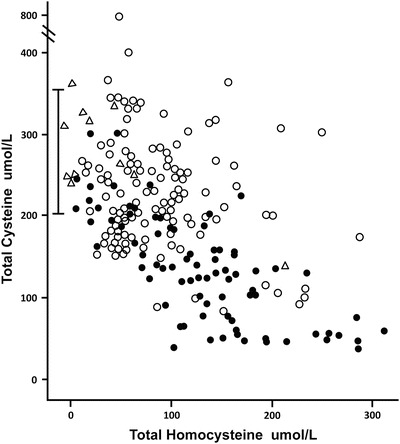

Total Cysteine

Median total cysteine was almost 50 % lower in CBS-deficient patients compared to those with remethylation defects, 136 vs. 221 umol/L (<0.001). A plot of total cysteine against tHcy (Fig. 5) shows that, in general, patients with remethylation defects had normal total cysteine although occasional subjects had low values, and that most CBS-deficient subjects had values below the reference range, even when treated.

Fig. 5.

The serum or plasma total homocysteine is shown plotted against the serum or plasma total cysteine in the three groups of patients. The patients with CBS deficiency are shown as closed circles, the patients with remethylation defects are open circles, and the case family members are shown as open triangles. The reference range for total cysteine is shown by the bar, 200–361 umol/L

AdoMet

Median AdoMet was higher in the CBS-deficient individuals compared to those with remethylation defects: 488 vs. 104 nmol/L (<0.001). A plot of AdoMet against tHcy (Fig. 6) shows that AdoMet values for those with CBS deficiency were generally higher than those for subjects with remethylation defects, especially when tHcy was greater than 100 umol/L, and that those with remethylation defects were generally in the normal range or slightly elevated, rather than low. An AdoMet above 425 nmol/L was found only in CBS deficiency.

Fig. 6.

The serum or plasma total homocysteine is shown plotted against the plasma or serum S-adenosylmethionine values. The reference range is shown by the bar, 71–168 nmol/L. The patients with CBS deficiency are shown as closed circles, the patients with remethylation disorders as open circles, and the case family members are shown as open triangles

AdoHcy

Those with CBS deficiency had a higher median value of AdoHcy than did those with remethylation defects: 73 vs. 38 nmol/L (0.005). As with AdoMet, the values for AdoHcy became markedly elevated in CBS-deficient individuals when tHcy was > 100 umol/L (Fig. 7). An AdoHcy value above 100 nmol/L was seen only in CBS deficiency.

Ratios Between Metabolites

Ratios between different metabolites were analyzed to see whether a more clear distinction between CBS deficiency and remethylation defects would be apparent (Table 4). With the exception of the AdoMet/AdoHcy ratio, all the metabolite ratios analyzed were markedly different between these two groups (0.001). Compared to controls, those with CBS deficiency had statistically different ratios for tHcy/Cysta, Met/tCys. tHcy/tCys, and tCys/Cysta; those with remethylation defects, different ratios for tHcy/Met, Cysta/Met, tHcy/tCys, and tCys/Cysta compared to controls.

Discussion

B6 Responsiveness of the Case Family Members

There was a remarkable response to pyridoxine in this family, with the tHcy levels falling to as low as 6.0, 8.6, and 5.8 umol/L in the proband, her brother, and niece. Among the published values for tHcy during treatment of CBS deficiency there have been few this low (Gaustadnes et al. 2002; Kelly et al. 2003; Ducros et al. 2006; Bermúndez et al. 2006; Weiss et al. 2006; Wilcken et al. 2006; Varlibas et al. 2009; Skovby et al. 2010; Novy et al. 2010; Kanzelmeyer et al. 2011). The definition of pyridoxine responsiveness in CBS deficiency is usually that the posttreatment values of tHcy are less than 50–60 umol/L (Kluijtmans et al. 1999; Yap et al. 2001). In view of the fact that the p.G307S mutation in the homozygous state is clearly B6-nonresponsive, and that even compound heterozygotes carrying p.G307S and the highly responsive p.I278T mutation or any one of at least six other point mutations are nonresponsive (evidence summarized in (Mudd 2011), the unusual responsiveness in the case family is apparently conferred by the second mutation, p.P49L. Compound heterozygotes carrying p.P49L as well as either deletion ΔG151-A159 (de Franchis et al. 1998), or point mutation p.E144K or p.R125Q are B6-responsive (Gaustadnes et al. 2002; Cozar et al. 2011). Expressed in E. coli and assayed either without or with addition of pyridoxal phosphate, the activity of the p.P49L mutant was found to be 2 % and 71 %, respectively, of wild type (Cozar et al. 2011) or 91 % and 82 % of wild type (Majtan et al. 2010). The difference between the relative activities without added pyridoxal phosphate may perhaps be due to the use of a stronger promoter and expression with a fusion partner in the studies of Majtan and coworkers. The close to wild-type activity of p.P49L in both studies fits with the relatively low tHcy values on B6 of compound heterozygotes carrying this mutation.

Limitations in the Current Diagnosis of Elevated tHcy

That the diagnosis of CBS deficiency was made for the case family only as long as 37 years after the proband had had a deep vein thrombosis and 13 years after she was found to have elevated tHcy may be attributed to several limitations of current diagnostic and management practices. Because these difficulties may be relevant for other patients, they will be discussed in the sections that follow.

Expectation That CBS-Deficient Patients Will Have Clinical Abnormalities in Addition to Vascular Problems

Based on the initial 20 or more years experience with homocystinuria due to CBS deficiency, it was apparent that this condition often presents with some combination of mental retardation, dislocated optic lenses, skeletal manifestations, and thrombotic disease (Mudd et al. 1985). However, in recent years it has become increasingly evident that it may also present by means of thromboembolic episodes only, without the other abnormalities (Skovby et al. 2010; Mudd 2011). At least 29 patients with thrombotic presentation in adolescence or adulthood without ectopic lenses, major skeletal or CNS abnormalities, have been reported prior to this article (Newman and Mitchell 1984; Marchal et al. 1989; Cochran et al. 1990; Favre et al. 1992; Lu et al. 1996; Gaustadnes et al. 2002; Gaustadnes et al. 2000a, b; Maclean et al. 2002; Kelly et al. 2003; Linnebank et al. 2003; Sueyoshi et al. 2004; Ducros et al. 2006; Wilcken et al. 2006; Chauveheid et al. 2008; Skovby et al. 2010; Novy et al. 2010; Magner et al. 2011; Cozar et al. 2011), but the true prevalence of such individuals remains unknown. Of those 29 patients, 18 were proven to be B6-responsive, and 6 may be presumed to be responsive because they were homozygotic for the p.I278T mutation. For those responders with data reported, the mean tHcy was 209.2 umol/L when not on B6 (range 58–285 umol/L), and 21.1 umol/L while on B6 (range 8–49 umol/L). For four patients, B6 responsiveness was questionable, but none were clearly not responsive. The available evidence further suggests that perhaps the predominant portion of B6 responders such as p.I278T homozygotes may be clinically normal, without even thromboembolic episodes (Skovby et al. 2010; Magner et al. 2011). Thus, underdiagnosis of CBS deficiency is clearly possible if the diagnosis is made only on the basis of clinical abnormalities.

Failure of Newborn Screening for Elevated Methionine to Detect B6-Responsive CBS Deficiency

Newborn screening for CBS deficiency, usually based on detection of blood methionine elevation, started as early as 1968 in Massachusetts, and is now mandatory throughout the United States (http://genes-r-us.uthscsa.edu/nbsdisorders.pdf). However, it is widely acknowledged that newborn screening for elevated methionine detects mainly B6 nonresponsive forms of CBS deficiency (Mudd et al. 1985; Peterschmitt et al. 1999; Sokolova et al. 2001; Gan-Schreier et al. 2010). Although worldwide such forms are estimated to have prevalences of 1 in 58,000 to 1,000,000 (Mudd 2011). The results of molecular genetic screening predict that CBS deficiency may often be far more common. For example, homozygosity for the p.I278T CBS mutation may occur as often as 1:20,400 in Denmark (Gaustadnes et al. 1999), and the deficiency due to the most common mutations may be as high as 1:6400 in Norway (Refsum et al. 2004), or 1:15,500 in the Czech Republic (Sokolova et al. 2001; Janosík et al. 2009).

B6-responsive patients when taking even minimal doses of B6 may have metabolite values that are normal or so close to normal as to prevent diagnosis. To establish CBS deficiency and to distinguish that abnormality from other causes of elevated tHcy, assays of tHcy must be accompanied by assays of other relevant metabolites

The results for the initial assays carried out at the University of Colorado for each member of the case family were entirely normal. Indeed the initial tHcy values were so low that lab error was considered as a possibility. In retrospect, this was the situation because each was taking vitamins including B6 at the time. After withdrawal of vitamin supplementation, the metabolite patterns of the proband and her brother became diagnostic of CBS deficiency. Vitamin B6 is commonly added to energy bars, drinks, diet supplements, etc., and is present in multivitamins in the United States and Canada. It seems possible that vitamin intake of which neither the patients nor the physicians were aware may have caused the apparently erratic variations in the metabolite levels in the proband and her brother and thus played a role in obscuring the diagnosis. Despite this marked vitamin responsiveness, and the lack of ocular, CNS, or skeletal manifestations, two members of the family had had life-threatening thrombotic events. Of note, both had such events while on oral contraceptives, an additional risk factor for thrombotic events.

Taking into account the newly compiled metabolite data presented in this report, the relative contributions of the various metabolites toward establishing the diagnosis for the case family and distinguishing between CBS deficiency and remethylation defects may be characterized as follows:

Very helpful diagnostically for this family at times of elevated tHcy were the elevations of AdoMet (Fig. 6) that occurred in the brother even when methionine was barely elevated (Table 1), as well as the rise of AdoHcy (Fig. 7), although that occurred most markedly only in the proband (Table 1). Taken together with the sparse data in the literature about AdoMet and AdoHcy values in CBS deficiency and remethylation disorders (Maclean et al. 2002; Stabler et al. 2002; Orendäc et al. 2003; Guerra-Shinohara et al. 2007), our data indicate that in remethylation defects serum or plasma AdoMet is usually normal to mildly elevated, and AdoHcy is modestly increased over the reference range. In contrast, in CBS deficiency AdoMet and AdoHcy may be strikingly elevated, increasing as the tHcy rises above 100 umol/L (Figs. 6 and 7). Thus, assays of AdoMet and AdoHcy may have strong diagnostic utility in separating CBS deficiency from remethylation defects. A limitation is that sample handling, storage, and preparation variables can cause major loss of AdoMet and increases in AdoHcy, factors that have limited their utility in the study of archived samples (Stabler and Allen 2004).

Elevations of methionine are expected in CBS deficiency and are used for screening for that condition (Mudd 2011), and monitoring compliance with methionine-restricted diets, an important part of the treatment of B6 nonresponsive patients. Such elevations, when present, were very useful in establishing the diagnosis for the case family. However, it is not uncommon for patients who present with only thrombotic manifestations of CBS deficiency to have methionines that are within the reference range or only mildly elevated (Lu et al. 1996; Ducros et al. 2006; Novy et al. 2010). Inborn errors of remethylation usually lead to normal or low serum methionine, but methionine values are dependent on the intake of methionine, and methionine was elevated in some of those with remethylation defects (Fig 4), possibly due to liver disease. Acquired cobalamin or folate deficiencies rarely have low methionine (Stabler et al. 1988). Together, these considerations indicate that homocystinuria due to CBS deficiency should not be ruled out based on a normal or only slightly elevated serum methionine value.

Another potentially useful (but rarely employed) diagnostic maneuver is the methionine loading test. However, the results in highly responsive CBS-deficient patients on pyridoxine have not been well studied. Renal insufficiency, common in adults with vascular disease, also causes elevated post-load tHcy and could lead to confusing results.

The results compiled in Fig. 3 show that assay of serum cystathionine may be very useful in distinguishing CBS deficiency (tendency to low cystathionine) from remethylation defects (tendency to elevated cystathionine), even while on vitamin therapy, yet caution is necessary, as shown by the results for the case family whose cystathionine values were generally in the normal range and overlapped the lower end of the range of patients with remethylation defects.

As already mentioned in “Results,” total cysteine tends to be lower in CBS deficiency than in remethylation defects, but there is overlap, even when tHcy is high. For the case family, only the proband’s total cysteine was below the reference range at a time the tHcy was extremely elevated.

To determine if, in addition to being helpful in distinguishing CBS-deficient individuals from those with remethylation defects, ratios in the family members might be suggestive even when the metabolite absolute values were in the normal range, the ratios from the family members in the six samples in which tHcy was elevated were analyzed (Table 4) and compared to the group with remethylation defects. The most striking differences were that the cysta/met ratio was tenfold less, and the tCys/Cysta ratio was eightfold higher in the family vs. remethylation defects.

Issues Relative to the Diagnosis and Management of Individuals with Elevated tHcy

Management issues arise when an undiagnosed patient with CBS deficiency sustains a thrombotic event in adult life. Assay of tHcy is part of the thrombophilia diagnostic panels in many clinical laboratories and hospitals. The most common cause of an elevated homocysteine value in folate-fortified populations is cobalamin deficiency. Appropriately, methylmalonic acid is assayed and, if normal, as in the proband’s case, can eliminate vitamin B12 deficiency. The availability of secondary metabolite testing for an adult general medical patient found to have elevated tHcy is quite limited. Cystathionine assays can be very valuable (Fig. 3), and are available from commercial reference labs in the United States. It is important that sensitive and specific quantitative assays be employed because the standard amino acid analyzer–based methods often define cystathionine normals as <1,000 nmol/L (occasionally 5–10 umol/L), levels that would not distinguish remethylation defects from CBS deficiency. Figure 3 shows that only a minority of subjects with remethylation defects have cystathionine >1,000 nmol/L. Mutation analysis of CBS can be used to confirm the suspected diagnosis in patients with elevated homocysteine although the yield will be better if they are preselected for elevated methionine and lack of clinical features consistent with methylation defects.

Primary care providers and hematologists reviewing homocysteine data frequently employ an empiric treatment approach with high-dose folic acid, vitamin B12, and occasionally vitamin B6, yet vitamin administration to patients with elevated tHcy prior to further testing may be inadvisable, especially for a patient presenting with a thrombotic episode only. Such patients (if similar to the case family members) are the ones most likely to completely normalize tHcys, and other methionine metabolites when taking vitamin supplements, so that to subsequently obtain an accurate diagnosis, the consulting service must decide whether to discontinue the vitamins and re-assay after a 1–2 month “washout period.” This does put the patient at some risk for a thrombotic event, although many such subjects will be on anticoagulation treatment and perhaps have less risk. It was only after all vitamin supplements had been discontinued in the proband and her brother that the metabolic pattern diagnostic of CBS deficiency became apparent, and was then confirmed by molecular genetic studies. A definite diagnosis is important for optimal disease management, prognosis assessment, and reproductive counseling. Because the family members were so responsive to vitamin B6, other typical measures (such as betaine- or methionine restriction) were not instituted but do remain as therapeutic options in the future. Many patients benefit from these additional treatment measures.

Summary

We conclude that there are likely individuals with highly responsive CBS deficiency presenting in adult life, particularly with thrombotic disease, who could be diagnosed by assays of a complete panel of methionine and related metabolites, especially before vitamin therapy is started or after its withdrawal. The cystathionine level has strong discriminatory value in distinguishing hyperhomocysteinemia due to CBS deficiency from remethylation defects and is commercially available with the caveat that only assays sensitive in the low nanomolar range are useful. Serum or plasma AdoMet may be markedly elevated in CBS deficiency and may be diagnostically useful, even when methionine is barely elevated. However, commercial assay is not widely available at present.

Further research on the prevalence of highly responsive CBS deficiency in thrombophilia clinics is clearly needed since CBS deficiency is one of the few causes of thrombophilia that requires therapy other than anticoagulation. It is also important to screen asymptomatic family members.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Carla Ray, Linda Farb, and Bev Raab. Preparation of the manuscript was assisted by Theresa M. Martinez.

Abbreviations

- 5-MTHF

5-methyltetrahydrofolate

- AdoHcy

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- AdoMet

S-adenosylmethionine

- B6

Pyridoxine

- Cbl

Cobalamin

- CBS

Cystathionine B-synthase

- CGL

Cystathionine gamma-lyase

- Cysta

Cystathionine

- MAT

Methionine adenosyltransferase

- Me-Cbl

Methyl-cobalamin

- Met

Methionine

- MS

Methionine synthase

- MTHFR

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- PLP

Pyridoxal phosphate

- SAHH

S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase

- tCys

Total Cysteine

- tHcy

Total homocysteine

Take-Home Message

In connection with the puzzling history of a family with B6-responsive cystathionine B-synthase deficiency without decreased cystathionines, and usually with normal methionines, extensive data are presented on values of relevant metabolites that may facilitate the differential diagnosis of elevated total homocysteine.

Contributions of Authors

SPS, RHA, and SHM were responsible for planning the details in the manuscript. SPS, MK, RJ, RHA, JPK, EBS, CW, and SHM were all involved in the conduct of obtaining the clinical and laboratory measures described in the manuscript. SPS, JPK, CW, and SHM wrote the bulk of the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

Guarantor for Article

Sally P. Stabler serves as the guarantor for this article, accepting full responsibility for the work. She had access to all the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing Interest Statement

Two of the authors, Sally P. Stabler and Robert H. Allen and the University of Colorado have competing interests. A patent on the use of homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, and cystathionine had been obtained by the University of Colorado and the two authors, which is now expired. A company has been formed at the University of Colorado to assay homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, and cystathionine. The other authors do not have competing interests.

Funding for Research

JPK was supported by the American Heart Association Grant NA09GRNT2110159. The authors confirm independence from the sponsors; the content of this article has not been influenced by the sponsors.

Ethics Approval

The compiled data came from studies previously reported which were under the purview of Institutional Review Boards as listed in the References. In addition, Protocol # 00–664 – “Methionine Metabolites in Inborn Errors” – was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Personal patient information for the case family is not included in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: S.P. Stabler and R.H. Allen

Contributor Information

Sally P. Stabler, Email: Sally.Stabler@ucdenver.edu

Collaborators: Johannes Zschocke and K Michael Gibson

References

- Allen RH, Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J. Serum betaine, N, N-dimethylglycine and N-methylglycine levels in patients with cobalamin and folate deficiency and related inborn errors of metabolism. Metabolism. 1993;42:1448–1460. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90198-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúndez M, Frank N, Bernal J, Urreizti R, Briceño I, Begoña M, Perez-Cerdá C, Ugarte M, Grinberg D, Balcells S, Kraus JP. High prevalence of CBS p.T191M mutation in homocystinuric patients from Columbia. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:296–302. doi: 10.1002/humu.9416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila A, Wagner C. Measurement of plasma S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine as their fluorescent isoindoles. Anal Biochem. 1998;264:180–184. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauveheid M-P, Lidove O, Papo T, Laissy J-P. Adult-inset homocystinuria arteriography mimics fibromuscular dysplasia. Am J Med. 2008;121:e5–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran FB, Sweetman L, Schmidt K, Barsh G, Kraus J, Packman S. Pyridoxine-unresponsive homocystinuria with an unusual clinical course. Am J Med Genet. 1990;35:519–522. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320350415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozar M, Urreizti R, Vilarinho L, Grosso C, Dodelson de Kremer R, Asteggiano CG, Dalmau J, Garcia AM, Vilaseca MA, Grinberg D, Balcells S. Identification and functional analyses of CBS alleles in Spanish and Argentinian homocystinuric patients. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:835–842. doi: 10.1002/humu.21514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Franchis R, Sperandeo MP, Sebastio G, Andria G, The Italian Collaborative Study Group on Homocystinuria Clinical aspects of cystathionine β-synthase deficiency: how wide is the spectrum? Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S67–S70. doi: 10.1007/PL00014309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducros V, Rousset J, Garambois K, Boujet C, Rolland MO, Valenti K, Bouillet L, Jaillard A, Favier A. Severe hypermethioninemia revealing homocystinuria in two young adults with mild phenotype. Revue de Medécine Interne. 2006;27:140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre JP, Becker F, Lorcerie B, Dumas R, David M. Vascular manifestations in homocystinuria. Ann Vasc Surg. 1992;6:294–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan-Schreier H, Kebbewar M, Fang-Hoffman J, Wilrich J, Abdoh G, Ben-Omran T, Shahbek N, Bener A, Al Rifai H, Al Khal AL, Lindner M, Zschocke J, Hoffman GF. Newborn population screening for classic homocystinuria by determination of total homocysteine from Guthrie cards. J Pediatr. 2010;156:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaustadnes M, Ingerslev J, Rütiger N. Prevalence of congenital homocystinuria in Denmark. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1513. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaustadnes M, Rüdiger N, Rasmussen K, Ingerslev J. Intermediate and severe hyperhomocysteinemia with thrombosis: a study of genetic determinants. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:554–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaustadnes M, Rüdiger N, Rasmussen K, Ingerslev J. Familial thrombophilia associated with homozygosity for the cystathionine beta-synthase 833T - C mutation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1392–1395. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.5.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaustadnes M, Wilcken B, Oliveriusova J, McGill J, Fletcher J, Kraus JP, Wilcken DEL. The molecular basis of cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in Australian patients: genotype-phenotype correlations and response to treatment. Hum Mutation. 2002;20:117–126. doi: 10.1002/humu.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Shinohara EM, Morita OE, Pagliusi RA, Blaia-d'Avila VL, Allen RH, Stabler SP. Elevated serum S-adenosylhomocysteine in cobalamin-deficient megaloblastic anemia. Metabolism. 2007;56:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janosík M, Sokolová J, Janosíková B, Krijt J, Klatovská V, Kozich V. Birth prevalence of homocystinuria in Central Europe: frequency and pathogenicity of mutation c.1105C>T (p.R369C) in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene. J Pediatr. 2009;154:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzelmeyer N, Tsikas D, Chobanyan-Jürgens K, Beckmann B, Vaske B, Illsinger S, Das AM, Lücke T. Asymmetric dimethyhlarginine in children with homocystinuria or phenylketonuria. Amino Acids. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating AK, Freehauf C, Jiang H, Brodsky GL, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Graham DK, Thomas JA, Van Hove JLK, Maclean KN. Constitutive induction of pro-inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines in cystathionine beta-synthase deficient homocystinuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;103:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Furie KL, Kistler JP, Barron M, Picard EH, Mandell R, Shih VE. Stroke in young patients with hyperhomocysteinemia due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Neurology. 2003;60:275–279. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000042479.55406.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluijtmans LAJ, Boers GHJ, Kraus JP, van den Heuvel LPWJ, Cruysberg JRM, Trijbels FJM, Blom HJ. The molecular basis of cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in Dutch patients with homocystinuria: effect of CBS genotype on biochemical and clinical phenotype, and on response to treatment. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:59–67. doi: 10.1086/302439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnebank M, Junker R, Nabavi DG, Linnebank A, Koch HG. Isolated thrombosis due to the cystathionine β-synthase mutation c.833T>C (I278T) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26:509–511. doi: 10.1023/A:1025129528777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C-Y, Hou J-W, Wang P-J, Chiu H-H, Wang T-R. Homocystinuria presenting as fatal common carotid artery occlusion. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;15:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean KN, Gaustadnes M, Oliveriusova J, Janosik M, Kraus E, Kozich V, Kery V, Skovby F, Rüdiger N, Ingerslev J, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Kraus JP. High homocysteine and thrombosis without connective tissue disorders are associated with a novel class of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) mutations. Hum Mutation. 2002;19:641–655. doi: 10.1002/humu.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner M, Krupková L, Honzik T, Zeman J, Hyánek J, Kozich V. Vascular presentation of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in adulthood. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:33–37. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majtan T, Liu L, Carpenter JF, Kraus JP. Rescue of cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) mutants with chemical chaperones: purification and characterization of eight CBS mutant enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15866–15873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal G, Giroud M, Nivelon A, Saudubray JM, Becker F, Martin F, Dumas R. Révélation tardive d’une homocystinurie par une aphasie et un spasme des artères iliaques externes. Ann Med Interne. 1989;140:520–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd SH. Hypermethioninemias of genetic and non-genetic origin: a review. Am J Med Genet Part C. 2011;157:3–32. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, Pettigrew KD, Wilcken B, Pyeritz RE, Andria G, Boers GHJ, Bromberg IL, Cerone R, Fowler B, Grobe H, Schmidt H, Schweitzer L. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd SH, Cerone R, Schiaffino MC, et al. Glycine N-methyltransferase deficiency: a novel inborn error causing persistent isolated hypermethioninemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:448–464. doi: 10.1023/A:1010577512912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman G, Mitchell JRA. Homocystinuria presenting as multiple arterial occlusions. Q J Med. 1984;210:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy J, Ballhausen D, Bonafé L, Cairoli A, Angelillo-Scherrer A, Bachmann C, Michel P. Recurrent postpartum cerebral sinus vein thrombosis as a presentation of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:871–873. doi: 10.1160/TH09-10-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orendäc M, Zeman J, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Kraus JP, Bodamer O, Stöckler-Ipsiroglu S, Kvasnicka J, Kožich V. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency: novel biochemical findings and treatment efficacy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26:761–773. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000009963.88420.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterschmitt MJ, Simmons JR, Levy HL. Reduction of false negative results in screening of newborns for homocystinuria. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1572–1576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsum H, Fredriksen A, Meyer K, Ueland PM, Kase BF. Birth prevalence of homocystinuria. J Pediatr. 2004;144:830–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage D, Gangaidzo I, Lindenbaum J, Kiire C, Mukiibi JM, Moyo A, Gwanzura C, Mudenge B, Bennie A, Sitima J, Stabler SP, Allen RH. Vitamin B12 deficiency is the primary cause of megaloblastic anaemia in Zimbabwe. Br J Haematol. 1994;86:844–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovby F, Gaustadnes M, Mudd SH. A revisit to the natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova J, Janosikova B, Terwilliger JD, Freiberger T, Kraus JP, Kozich V. Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in Central Europe: discrepancy between biochemical and molecular genetic screening for homocystinuric alleles. Hum Mutation. 2001;18:548–549. doi: 10.1002/humu.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SP, Allen RH. Quantification of serum and urinary S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine by stable-isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2004;50:365–372. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SP, Marcell PD, Podell ER, Allen RH, Savage DG, Lindenbaum J. Elevation of total homocysteine in the serum of patients with cobalamin or folate deficiency detected by capillary gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:466–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI113343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J, Savage DG, Allen RH. Elevation of serum cystathionine levels in patients with cobalamin and folate deficiency. Blood. 1993;81:3404–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SP, Steegborn C, Wahl MC, Oliveriusova J, Kraus JP, Allen RH, Wagner C, Mudd SH. Elevated plasma total homocysteine in severe MAT I/III deficiency. Metabolism. 2002;51:981–988. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss KA, Morton DH, Puffenberger EG, Hendrickson C, Robinson DL, Wagner C, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Chwatko G, Jakubowski H, Niculescu MD, Mudd SH. Prevention of brain disease from severe 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Ashizawa K, Hayashi K. Pulmonary and lower extremity vascular lesions in a patient with homocystinuria: radiologic findings. Am. J. Radiology. 2004;182:830–831. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangerman A, Mudd SH, Wilcken B, Boers GHJ, Levy HL. Methionine transamination metabolites in patients with homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. Metabolism. 2000;49:1071–1077. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.7709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlibas F, Cobanoglu O, Ergin B, Tireli H. Different phenotypy in three siblings with homocystinuria. Neurologist. 2009;15:144–146. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318184a4c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N, Demeret S, Sonneville R, Guillevin R, Bolgert F, Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Bilateral internal carotid artery dissection in cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Eur Neurol. 2006;55:177–178. doi: 10.1159/000093579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcken DEL, Wang J, Sim AS, Green K, Wilcken B. Asymmetric dimethylarginine in homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency: Relevance of renal function. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghmai R, Kashani AH, Geraghty MT, Okoh J, Pomper M, Tangerman A, Wagner C, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Mudd SH, Braverman N. Progressive cerebral edema associated with high methionine levels and betaine therapy in a patient with cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:57–63. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap S, Boers GHJ, Wilcken B, Wilcken DEL, Brenton DP, Lee PJ, Walter JH, Howard PM, Naughten ER. Vascular outcome in patients with homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency treated chronically. A multicenter observational study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2080–2085. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]