Abstract

Cu(I)-responsive fluorescent probes based on a photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism generally show incomplete fluorescence recovery relative to the intrinsic quantum yield of the fluorescence reporter. Previous studies on probes with an N-aryl thiazacrown Cu(I)-receptor revealed that the recovery is compromised by incomplete Cu(I)-N coordination and resultant ternary complex formation with solvent molecules. Building upon a strategy that successfully increased the fluorescence contrast and quantum yield of Cu(I) probes in methanol, we integrated the arylamine PET donor into the backbone of a hydrophilic thiazacrown ligand with a sulfonated triarylpyrazoline as a water-soluble fluorescence reporter. This approach was not only expected to disfavor ternary complex formation in aqueous solution but also to maximize PET switching through a synergistic Cu(I)-induced conformational change. The resulting water-soluble probe 1 gave a strong 57-fold fluorescence enhancement upon saturation with Cu(I) with high selectivity over other cations, including Cu(II), Hg(II), and Cd(II); however, the recovery quantum yield did not improve over probes with the original N-aryl thiazacrown design. Concluding from detailed photophysical data, including responses to acidification, solvent isotope effects, quantum yields, and time-resolved fluorescence decay profiles, the fluorescence contrast of 1 is compromised by inadequate coordination of Cu(I) to the weakly basic arylamine nitrogen of the PET donor and by fluorescence quenching via two distinct excited state proton transfer pathways operating under neutral and acidic conditions.

Introduction

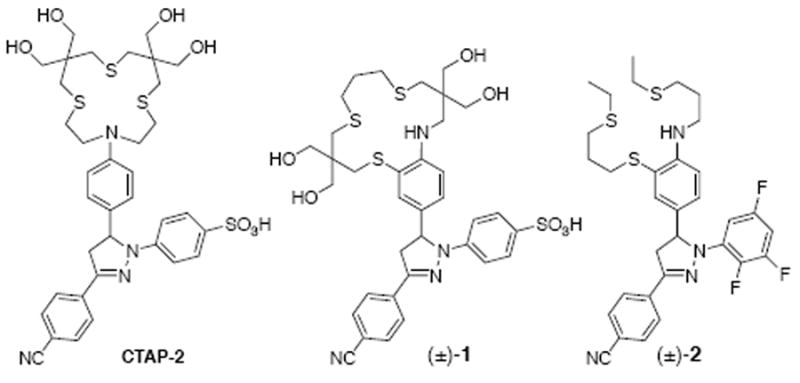

Fluorescence-based sensing with cation-selective probes is becoming a mainstay for the detection of biologically important trace metal ions, including zinc, copper, and iron.1 The reliable detection of the Cu(I) cation is particularly challenging due to its propensity to act as a fluorescence quencher,2 and, as we recently demonstrated, the tendency of thioether-based Cu(I)-selective ligands to aggregate in aqueous solution.3 We previously showed that a high-contrast fluorescence turn-on response to Cu(I) can be achieved with electronically tuned 1,3,5-triarylpyrazoline based probes via a photoinduced electron transfer (PET) switching mechanism.4,5 A balanced solubilization strategy combining hydroxymethylation of a thiazacrown Cu(I) receptor with sulfonation of the triarylpyrazoline fluorophore successfully suppressed aggregation at typical working concentrations in the contrast-optimized Cu(I) selective probe CTAP-2 (Chart 1).3 Although the 65-fold emission enhancement of CTAP-2 upon saturation with Cu(I) compares favorably to earlier Cu(I)-selective fluorescent probes,3-6,7 the fluorescence quantum yield of 0.083 upon saturation with Cu(I) is significantly lower than would be expected upon complete inhibition of PET; related 1,3,5-triarylpyrazolines consistently gave quantum yields above 0.4 in methanol.4 In acidic solution, CTAP-2 itself achieved a quantum yield of 0.25, implying that the fluorescence recovery upon Cu(I)-coordination is less than a third of the intrinsic fluorophore quantum yield. Previous studies in methanolic solution indicated that incomplete fluorescence recovery in structurally related triarylpyrazoline probes bearing an N-aryl thiazacrown Cu(I)-receptor is due to reversible Cu-N bond dissociation and ternary complex formation with solvent molecules.4 As a similar mechanism is likely operative for CTAP-2, we devised Cu(I)-probe 1 in which the thiazacrown ligand backbone is fused to the aryl ring to reinforce the Cu(I)-N interaction (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

This ligand design strategy, which should also provide a synergistic conformational and inductive PET switching effect, was previously implemented in methanolic solution with the water-insoluble Cu(I)-probe 2, which gave a remarkable 210-fold fluorescence enhancement and a quantum yield of 0.49 upon saturation with Cu(I).8 An equivalent fluorescence recovery with the water-soluble CTAP-2 fluorophore would be expected to double the current recovery quantum yield from 0.083 to approximately 0.19.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

The ligand framework of probe 1 was constructed based on the same thietane intermediate as utilized for the synthesis of CTAP-2.3 Iodide 4, obtained by ring opening of the thietane with benzyl chloride in the presence of sodium iodide, was reacted with benzothiazolin-2-one (3) in a one-pot N-alkylation/hydrolysis/S-alkylation procedure to give dibenzyl precursor 5 (Scheme 1). The benzyl protective groups were then removed without disturbing the aryl thioether linkage by the titanium-catalyzed method of Akao et al,9 and the resulting dithiol 6 was cyclized with 1,3-diiodopropane under Kellogg conditions10 to give macrocycle 7 (see Supporting Information). To assemble the pyrazoline fluorophore, 7 was first brominated on the aryl ring without oxidizing the sensitive aliphatic thioethers using 2,4,4,6-tetrabromocyclohexadienone under anhydrous conditions. Bromide 8 was then converted to aldehyde 9 by lithium-halogen exchange followed by quenching with DMF. Aldol condensation with 4-cyanoacetophenone gave chalcone 10. Removal of the acetonide-protecting groups followed by cyclization of the chalcone with 4-hydrazinobenzenesulfonic acid in one pot gave the desired triarylpyrazoline 1, which was isolated as the ammonium salt after HPLC purification (22% yield over 7 steps).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of fluorescent probe (±)-1.

Coordination Chemistry and Fluorescence Response

Compound 1 dissolved rapidly in water to millimolar concentrations. At micromolar concentrations in neutral MOPS-K+ buffer, 1 gave a strong fluorescence enhancement with addition of Cu(I), saturating sharply at one molar equivalent under deoxygenated conditions (Figure 1A). Consistent with a PET switching mechanism, the maximum emission wavelength remained unchanged at 506 nm throughout the titration. The response proved highly selective for Cu(I) over all cations tested including Cu(II), Cd(II) and Hg(II) (Figure 1B). Furthermore, identical fluorescence enhancements were obtained for Cu(I) supplied either as the acetonitrile complex (*) or by in situ reduction of Cu(II) with excess ascorbate (**). Contrary to our expectations, the fluorescence enhancement factor (57-fold) and quantum yield of 1 were not better compared to CTAP-2 (Table 1).3 Furthermore, the response of 1 to acidification was very weak, reaching a maximum quantum yield of only 0.07 at 0.1 M HCl versus 0.25 at 5 mM HCl for CTAP-2.

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence response of probe 1 (4.6 μM) to Cu(I) (provided by in-situ reduction of Cu(II) with 100 μM ascorbate) in aqueous buffer at pH 7.2 (10 mM MOPS/K+, 22°C, λex = 380 nm). (A) Mole-ratio titration of probe 1 with Cu(I). (B) Fluorescence response of probe 1 in the presence of an excess of the indicated analytes (10 mM for Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+; 10 μM for all other cations; *CuI(MeCN)4PF6; **CuIISO4 reduced in situ with 150 μM ascorbate).

Table 1.

Steady-state absorption and emission data of pyrazolines 1, 11, and CTAP-2 in aqueous solution at 22°C.

| compd | medium | abs λmax (nm) | em λmax (nm) | ΦF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pH 7.2a | 394 | 506 | 0.0014 |

| 1 | 0.1 M HCl | 391 | 504 | 0.070 |

| 1-Cu(I) | pH 7.2 a | 388 | 506 | 0.074 |

| CTAP-2 | pH 7.2 a | 396 | 512 | 0.0015 |

| CTAP-2 | 5 mM HCl | 388 | 512 | 0.25 |

| CTAP-2-Cu(I) | pH 7.2 a | 392 | 512 | 0.083d |

| 11 | pH 7.2 a,b | 387 | 511 | 0.28 |

| 11 | 5 mM HCl | 387 | 511 | 0.27 |

| 11 | 0.1 M HCl | 387 | 511 | 0.14 |

| 1-Cu(I) | D2O c | 388 | 506 | 0.089 |

| 11 | D2O | 387 | 511 | 0.48 |

| 11 | MeOH | 390 | 496 | 0.58 |

10 mM MOPS-K+.

identical values were observed in unbuffered H2O.

10 mM MOPS-K+ pH* 7.3 in D2O corresponding to pH 7.2 in H2O.14

65-fold enhancement over Cu(I)-free CTAP-2 (excitation at 380 nm).

In the presence of 2 molar equivalents (10 μM) of Cu(II) at pH 7.2, the fluorescence emission of 1 slowly increased in a time-dependent fashion, resulting in an approximately 6-fold increase after 30 minutes. Addition of only 0.4 equivalents of PEMEA11, a tripodal Cu(I)-chelator (logKCu(I) = 15.4 at pH 7.2), decreased the emission intensity by more than 60% within one minute. This indicates that the observed fluorescence increase is primarily due to reduction of ligand-bound Cu(II) to Cu(I), presumably with the unbound ligand serving as the electron source. A similar behavior was previously noted for probe 2.8

Cyclic voltammetry of the Cu(I)-saturated probe 1 at pH 5 revealed a one-electron process with a large peak separation of 266 mV (at 50 mV s-1 scan rate) and a formal potential of 0.080 ± 0.003 V vs. Fc+/0 (corresponding to 0.480 V vs SHE), suggesting large structural changes associated with the conversion from Cu(I) to Cu(II). Given the large peak separation, the measured potential is not suitable to determine a reliable Cu(I) affinity based on a thermodynamic cycle and the experimental Cu(II) stability constant.12 Instead, we determined the apparent Cu(I)-stability constant of 1 by direct fluorescence titration using acetonitrile as a competing ligand.7,13 Regardless whether the titration was conducted by varying the Cu(I) concentration and keeping acetonitrile constant or vice versa, a uniform apparent Cu(I) affinity of logKCu(I) = 9.72 ±0.03 at pH 7.2 was obtained.

Photophysical Studies

Intrinsic Fluorophore Quantum Yield and Fluorescence Recovery

Given the weak fluorescence response of probe 1 to both Cu(I) and acid, we sought to determine the intrinsic quantum yield of an analogous pyrazoline fluorophore that is devoid of PET quenching. To this end we synthesized reference compound 11, in which the 5-aryl ring is deactivated towards photoinduced oxidative electron transfer, and studied its fluorescence properties under neutral and acidic conditions (Table 1).

In neutral aqueous solution, 11 showed a fluorescence quantum yield of 0.28, which is only slightly higher than the value for CTAP-2 under acidic conditions (0.25 in 5 mM HCl). Consistent with this observation, the quantum yield of 11 was reduced by only 4% in 5 mM HCl; however, upon further acidification (0.1 M HCl) it dramatically decreased to 0.14. No such decrease was observed in 0.1 M KCl, indicating that the effect is not due to the increase in ionic strength or chloride concentration but rather to the reduction in pH. Furthermore, the absorption spectra of 11 in 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M KCl are superimposable, as are those in 1 M HCl and 1 M KCl, suggesting that the observed fluorescence quenching at low pH is due to an excited state proton transfer (ESPT) process rather than ground state protonation.

Prompted by the observations with reference compound 11, we next investigated the behavior of probe 1 under acidic conditions in more detail. In contrast to the reference compound, 1 underwent a significant shift in absorption maximum from 394 nm in 1 M KCl to 388 nm in 1 M HCl. As a similar absorption change from 396 to 388 nm occurred upon protonation of CTAP-2 with 5 mM HCl, the observed shift is presumably due to protonation of the arylamine moiety of the Cu(I)-binding site. In 0.1 M HCl, probe 1 gave an absorption maximum of 391 nm, exactly halfway between the values observed in neutral solution and 1 M HCl. Nonlinear least-squares fitting of a series of absorption spectra acquired in aqueous HCl-KCl mixtures with varying pH but constant ionic strength yielded an extrapolated pKa value of 1.0. This unusually low pKa, combined with the observed fluorescence quenching of reference compound 11 by H3O+, fully explains the low quantum yield observed for 1 upon acidification: high acid concentrations are required to protonate the arylamine PET donor to a significant extent, but H3O+ also directly quenches the pyrazoline fluorophore by ESPT. At 0.1 M HCl, only half of 1 is protonated at the arylamine nitrogen, but the fluorescence quantum yield is further reduced by half due to ESPT quenching of the fluorophore, thus bringing the quantum yield down from 0.28 (the value for reference compound 11) to the observed value of 0.07.

As a large concentration of H3O+ is needed to produce significant quenching by ESPT, an entirely different explanation is required for the incomplete fluorescence recovery of 1-Cu(I) relative to 11 in neutral solution. Fluorescence quenching by PET with Cu(I) as the electron donor is unlikely, because such a pathway would be expected to be orders of magnitude slower than the rapid radiative deactivation rate of the fluorophore.4 A more likely explanation for the incomplete fluorescence recovery might be derived from the low basicity of the arylamine nitrogen in 1, which is expected to coordinate only weakly, if at all, with the Cu(I) center. Such a weak interaction would imply a small change in donor potential, and thus a reduced fluorescence contrast between the free and Cu(I)-bound probe. Inadequate donor strength of the arylamine nitrogen is also consistent with the relatively low Cu(I) binding affinity of 1, which is nearly 120-fold weaker than the corresponding tetrathioether macrocycle [15]aneS4 (log KCu(I) = 11.8)15 and 50-fold weaker than CTAP-2 (log KCu(I) = 11.4).3 A similarly low affinity was recently reported for the NIR Cu(I)-selective probe CS790 (log KCu(I) = 10.5),16 whose chelating moiety is structurally closely related to that of our high-contrast probe 2.8

Time-resolved Fluorescence Decay Studies

Previous studies in methanol demonstrated that the weak Cu(I)-arylamine nitrogen interaction gives rise to the formation of multiple coordination species, presumably also involving ternary complexes with solvent molecules. Although these species are engaged in a dynamic exchange equilibrium that cannot be resolved on the NMR time scale, they can be detected based on their distinct fluorescence lifetimes using picosecond time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy.4 Consistent with the presence of multiple coordination species, both CTAP-2-Cu(I) and 1-Cu(I) gave multiexponential fluorescence decay profiles (Figure 2). Deconvolution of the CTAP-2 decay profile with a biexponential model produced an excellent fit with two lifetime components of 0.82 ns (67%) and 1.36 ns (33%) (Table 2). The decay profile of 1-Cu(I) also fits best to a biexponential model with very similar lifetimes of 0.72 ns and 1.44 ns, respectively; however, in contrast to CTAP-2, the shorter-lived species is by far the dominant component (93%). The predominance of a single component in the decay profile of 1-Cu(I) suggests that the ligand architecture of 1 quite effectively discriminates over the formation of multiple coordination species; however, the rather short fluorescence lifetime of 0.72 ns implies a weak or absent interaction between the arylamine nitrogen and the Cu(I)-center.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence decay profile of reference compound 11 as well as CTAP-2 and 1 saturated with Cu(I) in deoxygenated aqueous buffer at pH 7.2 (10 mM MOPS/K+, 22°C). Each sample was excited at 372 nm (80 ps fwhm), and the emission signal was detected at 506 nm by single photon counting. Non-linear least squares fitted traces are shown as solid lines (see Table 2 for data; IRF = instrument response function).

Table 2.

Time-resolved fluorescence decay data for pyrazolines 1, 11, and CTAP-2 in aqueous and methanolic solution at 22 °C.

| compd | medium | τF (ns) | χ2 | kr (108 s−1) f | knr (108 s−1) g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Cu(I) | pH 7.2 a | 0.72 (0.93)e | 1.094 | 0.95 h | 11.9 h |

| 1.44 (0.07)e | |||||

| 1-Cu(I) | D2O a,b | 0.94 (0.90) e | 1.141 | 0.84 h | 8.64 h |

| 2.04 (0.10) e | |||||

| CTAP-2-Cu(I) | pH 7.2 a | 0.82 (0.67) e | 1.031 | 0.83 h | 9.15 h |

| 1.36 (0.33) e | |||||

| 11 | H2O c, d | 2.07 | 1.167 | 1.35 | 3.48 |

| 11 | D2O c | 3.56 | 1.031 | 1.35 | 1.46 |

| 11 | MeOH c | 3.58 | 1.075 | 1.62 | 1.17 |

Deoxygenated conditions.

10 mM MOPS-K+ pH* 7.3 in D2O corresponding to pH 7.2 in H2O. 14

Air saturated conditions.

Deoxy-genation had no effect on the observed lifetime within experimental error.

normalized pre-exponential factors from fitted biexponential decay function.

radiative deactivation rate constant kr = ΦF/τF.

nonradiative deactivation rate constant knr = (1-ΦF)/τF.

estimated based on the natural decay lifetime τ = f1•τ1+f2•τ2, where f1 and f2 are the fractional contributions of each component.

As expected for a uniform emitter, reference compound 11 yielded a clean monoexponential decay profile, but the deconvoluted fluorescence lifetime of 2.07 ns is significantly shorter than the 3-4 ns lifetimes of related triarylpyrazolines in methanol or acetonitrile.4,8,17 Interestingly, the fluorescence lifetime of 11 increased to 3.58 ns in methanol, indicating that the shorter lifetime in aqueous solution is not an inherent property of the compound, but rather caused by a large increase in the nonradiative deactivation rate from 1.2 · 108 s−1 in MeOH to 3.5 · 108 s−1 in H2O (Table 2). As the absorbance and fluorescence intensity of 11 scaled linearly with concentration (data not shown), the increased nonradiative deactivation rate in H2O is unlikely due to aggregation.

Given the apparent excited state protonation of 11 at low pH, we reasoned that the increased nonradiative deactivation rate in H2O compared to MeOH might be due to an additional excited state proton transfer pathway with neutral H2O as the proton donor. Substitution of D2O for H2O increased the fluorescence lifetime to 3.56 ns, a value that is within experimental error identical with the lifetime observed in methanol. As the fluorescence quantum yield increased proportionally to 0.48 in D2O (Table 1), the radiative deactivation rates in D2O and H2O are identical. The normalized fluorescence spectra in H2O and D2O are also identical within experimental error, indicating that any emission from the species formed by protonation of the excited state is negligible. Furthermore, addition of 0.1 M NaOH had no effect on the fluorescence intensity and emission maximum of 11 in H2O. Taken together, these data suggest that the reduced quantum yield of 11 is due to a nonradiative ESPT pathway in which the initial proton transfer from H2O to the excited fluorophore represents an irreversible and rate-limiting step.

Although the similarly low knr values in methanol and D2O would seem to suggest that ESPT is completely inhibited in both solvents, comparable solvent isotope effects have been observed in methanolic solution for triarylpyrazolines without the strongly electron-withdrawing 3-aryl cyano-group. These effects, which were enhanced by electron donating substituents and diminished by electron withdrawing substituents on the 1-aryl ring, were also attributed to excited-state protonation.18 Therefore, there remains some uncertainty as to whether the ESPT quenching pathway is fully abrogated in D2O and MeOH; however, as the fluorescence lifetimes of structurally related triarylpyrazolines rarely reach values above 4 ns,17,19 the difference between the nonradiative deactivation rate constants in H2O vs D2O may serve as a reasonable estimate for the rate of the ESPT process in neutral H2O, yielding

Furthermore, if the ESPT quenching pathway were not operative for 1-Cu(I) in neutral aqueous solution, the nonradiative deactivation rate constant knr would decrease from 1.2·109 s−1 to 1.0·109 s-1, and the quantum yield would increase accordingly to ΦF = kr/(kr + knr) = 0.088. This estimate is in excellent agreement with the experimentally determined quantum yield of 0.089 in D2O (Table 1). Because of the more than 5-fold slower kinetics of the ESPT pathway compared to nonradiative deactivation resulting from incomplete inhibition of PET by Cu(I)-coordination, the observed quantum yield improvement remains modest. Nevertheless, the impact of ESPT on the recovery quantum yield becomes gradually more relevant with decreasing residual PET quenching in the Cu(I)-bound form. For example, if PET were completely inhibited by Cu(I)-coordination, the quantum yield would rise from 0.074 to 0.28, and in the absence of ESPT would further increase to 0.48, corresponding to an additional 70% improvement. Given that such quantum yields have already been achieved for high-contrast Cu(I)-probes in methanol,8 we anticipate that similar improvements over current water-soluble Cu(I) probes will be attainable with further optimized ligand architectures.

Conclusions

In an effort to improve upon the fluorescence contrast ratio and quantum yield offered by our previous aqueous Cu(I) probe CTAP-2, we integrated the balanced solubilization strategy of CTAP-2 with the PET switch design of our high-contrast methanolic Cu(I) probe 2 to create the water-soluble probe 1. While 1 gave a strong fluorescence turn-on response with high selectivity for Cu(I), it did not exceed CTAP-2 in contrast ratio or quantum yield. Detailed photophysical studies with probe 1, CTAP-2 and reference fluorophore 11 uncovered two separate effects that limit the response of both 1 and CTAP-2 to Cu(I): 1) Concluding from strong solvent deuterium isotope effects, the triarylpyrazoline fluorophore is significantly quenched by ESPT in neutral aqueous solution, and 2) according to fluorescence lifetime analysis, incomplete PET inhibition, presumably due to weak coordination of Cu(I) to the arylamine electron donor, is responsible for the incomplete fluorescence recovery. Because cation-selective fluorescent probes frequently rely on coordination of a single donor atom within a multidentate ligand to translate analyte binding into a strong fluorescence response, the second effect likely has broad significance to fluorescent probe design, including probes for cations other than Cu(I). We anticipate that this work will serve as a guidepost for future design of water-soluble cation-selective fluorescent probes with improved fluorescence contrast and quantum yield.

Experimental

Synthesis

Materials and reagents: 2,4,4,6-tetrabromocyclohexadienone was purchased from Alfa Aesar and the purity was determined via 1H NMR (CDCl3) shortly before use (impurity is 2,4,6-tribromophenol). Diglyme (diethylene glycol dimethyl ether) was distilled from sodium-benzophenone and stored under argon. Dry diethyl ether and dry DMF (EMD DriSolv® grade) were used as received. Other solvents and reagents were purchased from standard commercial sources and used as received. CTAP-2 was synthesized as previously reported.3 NMR: Spectra were recorded at 400 MHz (1H, ppm vs. internal TMS), 376 MHz (19F, ppm vs. internal CCl3F), and 100 MHz (13C, ppm vs. TMS, referenced to CDCl3 (77 ppm) or CD3OD (49 ppm) chemical shifts). Spectra were recorded at ambient temperature (20-23°C) unless stated otherwise. For 1H spectra, the abbreviation “ad” denotes an apparent doublet with additional partially resolved coupling (AA’XX’ spin system). In the 13C spectra, isochronous chemical shifts for nonequivalent carbon nuclei were observed for 1, 6, and 7. The coincident peaks were identified via integration, and the number of carbon nuclei represented by each peak is given in parentheses.

5-((benzylthio)methyl)-5-(iodomethyl)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane (4)

A mixture of 7,7-Dimethyl-6,8-dioxa-2-thia-spiro[3.5]nonane3,20 (8.19 g, 47 mmol), benzyl chloride (5.62 mL 48.9 mmol), NaI (10.6 g, 70.5 mmol), Na2CO3 (1g), and CH3CN (20 mL) was stirred for 10 d in the dark. The resulting yellow mixture was stirred with aqueous Na2SO3 until colorless, diluted with water (200 mL), and extracted with MTBE (200 mL). The extract was washed with water (200 mL) followed by brine (20 mL), dried with MgSO4, and concentrated. The yellow residue was taken up in dichloromethane (100 mL), stirred with silica gel (5g), filtered, and concentrated to give 4 as a colorless oil which was used without further purification. Yield 18.1 g (98%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 2.60 (s, 2H), 3.39 (s, 2H) 3.68 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 2H), 3.72 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 2H), 7.22-7.30 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 12.9, 23.2, 23.9, 35.8, 36.7, 37.9, 66.3, 76.7, 98.6, 127.1, 128.5, 129.0, 138.0. EI-MS m/z 392 (27, [M]+), 334 (68), 91 (100). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C15H21IO2S 392.0307, found 392.0303.

N-((5-((benzylthio)methyl)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)-methyl)-2-(((5-((benzylthio)methyl)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)methyl)thio)aniline (5)

A mixture of 4 (8.13 g, 20.7 mmol), benzothiazolin-2-one 3 (3.13 g, 20.7 mmol), Cs2CO3 (8.1 g, 25 mmol) and DMSO (9 mL) was stirred under argon overnight at 80°C. The mixture was diluted with 30 mL DMSO, and 20% w/v aq. NaOH (16.6 mL, 83 mmol) was slowly injected. A further 28 mL of DMSO was added simultaneously with NaOH as needed to prevent separation of the intermediate from the reaction mixture. After 35 min, acetic acid (1.42 mL, 25 mmol) was added to destroy excess NaOH, and a further 20.7 mmol of 4 was added as a solution in DMSO (11 mL). After 30 min, the mixture was allowed to cool, poured into water (300 mL) and extracted with MTBE (250 mL). The extract was washed with water + brine (2 × (250 mL + 10 mL)), dried with MgSO4, and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes-MTBE) to give 5 as a yellow oil. Yield 10.2 g (75%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.44 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 2H), 2.72 (s, 2H), 2.85 (s, 2H), 3.35 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (s, 2H), 3.69-3.75 (m, 10H), 5.22 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (td, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (ddd, J = 8.6, 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21-7.27 (m, 10H), 7.39 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 22.5, 22.7, 24.7, 25.0, 34.7, 34.8, 37.8, 38.0, 38.3, 38.4, 38.8, 45.9, 65.4, 66.2, 98.3, 98.4, 110.4, 117.0, 117.7, 127.0, 127.1, 128.4, 128.5, 128.9, 129.0, 130.2, 135.8, 137.9, 138.2, 149.4. MALDI-HRMS (matrix: dithranol) m/z calcd for [M+H]+ C36H48NO4S3 654.2745 found 654.2767.

N-((5-(mercaptomethyl)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)- methyl)-2-(((5-(mercaptomethyl)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-5-yl)methyl)thio)aniline (6)

An oven-dried 250 mL three-necked rb flask equipped with a gas inlet, thermometer, magnetic stir bar, and rubber septum was charged with a solution of 5 (10.1 g, 15.4 mmol) in benzene (20 mL). The solution was concentrated under a stream of argon at 80°C, and diglyme (62 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred in an ice bath, and dibutylmagnesium solution (1 M in heptane, 62 mL) was added at a rate such that the temperature did not rise above 15°C. The Ar flow rate was then increased, the rubber septum was removed, solid Cp2TiCl2 (384 mg, 1.54 mmol) was added, and the septum was quickly replaced. The ice bath was removed after 5 min, and after 30 min the reaction was quenched with methanol (10 mL). The mixture was treated with citrate buffer (0.5 M trisodium citrate, 0.5 M citric acid, 120 mL), diluted with water (200 mL), and extracted with MTBE (250 mL). The organic layer was back-extracted with 5% aq. NaOH + methanol (3 × (60 mL + 10 mL)). The combined aqueous extracts were washed with hexanes (200 mL), acidified with citrate buffer (100 mL) + 1 M HCl (180 mL), and the resulting emulsion was extracted with 1:1 MTBE-toluene (300 mL). The extract was washed with water (3 × 500 mL), dried with MgSO4, and concentrated to give 6 as a pale pink oil. Yield 6.82 g (93%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.16 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 1.35 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 3H), 2.74 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 2.80 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 3.35 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 2H), 3.78 (s, 4H), 5.16 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (td, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (ddd, J = 8.5, 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 22.5, 23.2, 24.2, 24.7, 27.2 (2C), 37.6, 37.90, 37.92, 45.2, 65.1, 66.0, 98.4, 98.6, 110.5, 117.4, 117.6, 130.5, 136.0, 149.3. EI-MS m/z 473 ([M]+, 100), 458 (25), 312 (48), 254 (49), 137 (30), 136 (64), 87 (21).). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C22H35NO4S3 473.1728, found 473.1731.

Macrocycle 7

Solutions of dithiol 6 (6.81 g, 14.4 mmol) and 1,3-diiodopropane (4.25 g, 14.4 mmol) in DMF (each 23 mL total volume) were added via a syringe pump over 18 h to a stirred suspension of Cs2CO3 (18.7 g, 57.5 mmol) in DMF (800 mL) under argon at 87°C (internal temperature). After cooling, the liquid phase was decanted, and the solid was washed with warm xylenes (3 × 100 mL). The combined liquid phases were concentrated to dryness, and the residue was stirred in toluene (250 mL). After 10 min, the mixture was filtered through Celite and concentrated to dryness. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes-MTBE), and crystallized from boiling cyclohexane (20 mL) by addition of hexanes (25 mL) under stirring to give 7 as a colorless crystalline powder. Yield 4.91 g (66%). Mp 123-123.5 °C 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.48 (s, 3H), 1.95 (p, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.66 (s, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.85 (s, 2H), 2.94 (s, 2H), 3.52 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.67 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 2H), 3.73 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (s, 4H), 5.58 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (td, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (ddd, J = 8.5, 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 20.9, 22.7, 24.6, 26.6, 27.8, 31.4, 31.8, 34.9 (2C), 37.8, 38.5, 39.7, 44.8, 65.8, 66.7, 98.4, 98.5, 110.7, 117.0, 117.1, 130.4, 136.2, 150.2. EI-MS m/z 513 ([M]+, 100), 498 (27), 220 (18), 150 (33), 137 (80), 136 (74), 83 (18). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C25H39NO4S3 513.2041, found 513.2042.

Bromide 8

Macrocycle 7 (3.43 g, 6.68 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (25 mL, dried over 4Å ms) in a 50 mL three-necked flask equipped with a gas inlet, thermometer, and stir bar. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath under Ar, and solid 2,4,4,6-tetrabromocyclohexadienone (4.10 g of 80% pure material, 8.0 mmol) was added in small portions against a gentle argon current at 0-10°C. After 10 minutes, the reaction was quenched with a solution of Na2SO3 (1.7 g, 13 mmol) and 20% aq. NH3 (1.2 mL, 13 mmol) in H2O (20 mL), then diluted with MTBE (100 mL). The aqueous layer was removed, and the organic layer was washed with water + 5% aq. NaOH (3 × (100 mL + 10 mL)), dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated. The residue was taken up in boiling hexanes (35 mL), filtered through cotton, and crystallized from hexanes-ethanol to give 8 as a colorless crystalline powder. Yield 2.78 g (72%). Mp 121-122.5°C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 3H), 1.95 (p, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.60 (s, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (s, 2H), 2.94 (s, 2H), 3.52 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 4H), 5.60 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.53 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 20.4, 20.8, 24.4, 27.0, 27.6, 31.3, 31.9, 34.9, 35.0, 37.7, 38.5, 39.7, 44.7, 65.7, 66.7, 98.5, 98.6, 107.6, 112.2, 118.6, 133.0, 137.9, 149.3. EI-MS m/z 593 (100), 591 ([M]+, 92), 578 (14), 576 (13), 217 (50), 215 (50), 214 (40), 83 (39). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+C25H38NO4S3Br 591.1146, found 591.1145.

Aldehyde 9

Bromide 8 (2.59 g, 4.37 mmol) was added to an oven-dried two-necked flask equipped with a thermometer and magnetic stir bar, and the flask was sealed with a rubber septum and flushed with argon. Dry Et2O (48 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred until the bromide completely dissolved, then cooled in a dry ice-acetone bath. n-Butyllithium solution (2.5 M in hexanes, 3.5 mL, 8.7 mmol) was added dropwise at a rate such that the temperature did not exceed -60°C. tert-Butyllithium solution (1.6 M in pentane, 8.2 mL, 13 mmol; Caution: highly pyrophoric) was then added likewise. After 30 minutes, dry DMF (2.7 mL, 35 mmol) was added, the dry ice bath was removed, and the reaction was quenched with methanol (5 mL) once the internal temperature reached -30 °C. The mixture was then partitioned between toluene (70 mL) and water (70 mL). The aqueous layer was removed, and the organic layer was washed with water (3 × 70 mL) followed by brine (10 mL), dried with MgSO4, stirred with silica gel (5 g) and filtered. The drying agent and silica were washed with MTBE, and the combined filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure to give a brown oil. This material crystallized from boiling cyclohexane-ethyl acetate (30 mL + 5 mL), and the colorless crystalline powder was collected by filtration after cooling. Yield 2.15 g (91%). Mp 149-150°C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 3H), 1.50 (s, 3H), 1.97 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.58 (s, 2H), 2.81-2.86 (m, 6H), 2.93 (s, 2H), 3.60 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 2H), 3.70-3.74 (m, 4H), 3.76 (s, 4H), 6.44 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 9.69 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 19.8, 22.6, 24.6, 27.1, 27.6, 31.1, 32.2, 34.8, 35.0, 37.6, 38.7, 39.7, 43.8, 65.6, 66.7, 98.5, 98.6, 109.6, 116.9, 126.3, 133.4, 138.8, 154.8, 189.5. EI-MS m/z 541 ([M]+, 100), 526 (16), 178 (18), 165 (87), 164 (53), 83 (29). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C26H39NO5S3 541.1990, found 541.1996.

Chalcone 10

Aldehyde 9 (523 mg, 965 μmol) and 4-cyanoacetophenone (147 mg, 1.01 mmol) were dissolved in ethanol (5 mL) + MTBE (2.5 mL) at 63°C (bath temperature). Pyrrolidine (160 μ L, 1.9 mmol) was added, and the flask was sealed with a Teflon stopper. After 2 hours, a 150 μL aliquot of the reaction mixture was transferred to a glass vial, concentrated to dryness, and crystallized from CH2Cl2-hexanes (0.3 mL each). The crystal slurry was concentrated to dryness, taken up in MTBE, and added back to the reaction mixture, which rapidly crystallized. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 63°C, then for 36 h at 45-50°C. After cooling slowly to 4°C, the product was collected by filtration, washed with cold ethanol, and dried to give 10 as an orange crystalline powder. Yield 588 mg (91%). Mp 148-151°C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.43 (s, 6H), 1.46 (s, 3H), 1.51 (s, 3H), 1.97 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.58 (s, 2H), 2.81-2.86 (m, 6H), 2.98 (s, 2H), 3.62 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 2H), 3.69-3.74 (m, 4H), 3.77 (s, 4H), 6.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77-7.80 (m, 3H), 8.05-8.08 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 19.8, 23.4, 23.9, 27.1, 27.7, 31.3, 32.2, 35.0, 35.2, 37.7, 38.8, 39.7, 44.0, 65.6, 66.8, 98.6, 98.7, 110.5, 115.4, 116.3, 117.1, 118.2, 123.2, 128.7, 132.1, 132.3, 137.9, 142.3, 146.6, 152.8, 188.8. EI-MS m/z 668 ([M]+, 100), 653 (10), 305 (18), 292 (75), 291 (52), 130 (17), 83 (20). EI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C35H44N2O5S3 668.2412, found 668.2413.

Triarylpyrazoline 1 ammonium salt

A mixture of chalcone 10 (56.7 mg, 85 μmol), methanol (3 mL), and 1 M aq. HCl 68 μL) was boiled under stirring in a 90°C bath until the starting material dissolved completely (10 min). Water (0.8 mL) was then added, and the mixture was concentrated to ca. 1 mL. Ethanol (3 mL) was added, and the mixture was concentrated to dryness. Water (1 mL), ethanol (1.2 mL), 4-hydrazinobenzenesulfonic acid hemihydrate (25 mg, 130 μmol) and pyridine (16 μL, 200 μmol) were added. The reaction vessel was flushed with Ar, sealed, and stirred at 90°C for 16 h. The mixture was allowed to cool, then concentrated to dryness under a stream of Ar in a 35°C bath. The residue was completely dissolved in aq. NH4HCO3 (34 mg, 420 μmol, 3 mL), concentrated to dryness, redissolved in 4 mL water, and subjected to RP-HPLC to give (±)-1 as a yellow glassy solid after drying under high vacuum. Yield 50.4 mg (82%). HPLC tr = 16.8 min. (gradient 0-20 min., 28% to 35% MeCN / 0.5% aq. NH4HCO3 at 4 mL/min, 30 × 1 cm C18 column). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 25°C) δ 1.83 (p, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.54 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.57 (overlapping t, J ≈ 7 Hz), 2.60 (s, 2H), 2.75 (s, 2H), 2.87 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 17.4, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (s, 2H) 3.47 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.51 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.53-3.56 (m, 6H), 3.80 (dd, J = 17.4, 12.3 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (dd, J = 12.3, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (ad, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (ad, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (ad, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.86 (ad, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 30.0, 32.1, 32.4, 33.9, 34.9, 40.1, 43.6, 45.9, 46.0, 46.4, 65.0 (br, 2C), 65.06, 65.12, 65.16, 111.7, 112.3, 114.1, 119.8, 120.9, 127.4, 127.9, 128.0, 130.7, 133.5 (3C, 2 equivalent, 1 coincident) 136.7, 138.5, 146.6, 147.8, 150.1. ESI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]- C35H41O7N4S4 757.1853, found 757.1845.

Triarylpyrazoline (±)-11

The chalcone 1-(4-cyanophenyl)-3-(4-di- methylaminophenyl)-prop-2-ene-1-one17 (655 mg, 2.37 mmol) was completely dissolved in CH2Cl2, (10 mL) and methyl triflate (402 μL, 3.56 mmol) was added dropwise to the stirred solution. After 20 h, the precipitated product was collected by filtration, washed with CH2Cl2 followed by diethyl ether, and dried under vacuum to give triflate salt 12 as an off-white crystalline powder. Yield 964 mg (92%). Mp 224-225°C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.66 (s, 9H), 7.85 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 8.05-8.13 (m, 5H), 8.19 (ad, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 8.33 (ad, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H). 19F NMR (DMSO-d6) δ −77.3 (s, 3F). ESI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M]+ C19H19ON2 291.1492, found 291.1484. Above triflate 12 (490 mg, 1.11 mol), 4-hydrazinobenzenesulfonic acid hemihydrate (241 mg, 1.22 mmol), pyridine (136 μL, 1.67 mmol) and methanol (4 mL) were stirred overnight in a sealed vessel under Ar at 75°C. After cooling, the mixture was diluted with water + 20% aqueous ammonia (4 mL + 0.15 mL) and stirred for 1 h at 0°C. A yellow powder (390 mg) was collected by filtration and determined by 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) to be a mixture of isomeric hydrazones. This material was stirred in acetic acid (3 mL) + water (1 mL) for 3 hours at 100°C under Ar. After cooling, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH3CN under rapid stirring, and the resulting yellow crystalline powder was collected by filtration, washed with MeOH, and dried under vacuum to give (±)-11 as a fine orange powder. Yield 220 mg (43% overall). To prepare an analytical sample, the product was dissolved in a minimum volume of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol, filtered through a tight cotton plug, and diluted 10-fold with water to give yellow needles after standing overnight. The needles crumbled to a fine orange powder upon drying. Mp 262°C (dec). UV λmax 387 nm (ε = 2.6 × 104 M-1 cm-1). 1H NMR (2 M LiCl in CD3OD, 35°C) δ 3.17 (dd, J = 17.6, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (s, 9H), 4.05 (dd, J = 17.6, 12.4 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (dd, J = 12.4, 5.8 Hz), 7.09 (ad, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (ad, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (ad, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (ad, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (ad, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (ad, J = 9.1 Hz). ESI-HRMS m/z calcd for [M+H]+ C25H25O3N4S 461.1642, found 461.1636.

Steady-state absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

Sample solutions were filtered through 0.45 μm nylon membrane filters to remove interfering dust particles or fibers. UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded at 22 °C using a Varian Cary Bio50 UV-vis spectrometer with constant-temperature accessory. Steady-state emission and excitation spectra were recorded with a PTI fluorimeter. Path lengths were 1 cm with a cell volume of 3.0 mL. The fluorescence spectra have been corrected for the spectral response of the detection system (emission correction file provided by instrument manufacturer) and for the spectral irradiance of the excitation channel (via a calibrated photodiode). Mole-ratio titrations with Cu(I) were carried out by addition of aqueous copper (II) sulfate stock solution to a 4.6 μM working solution of probe 1 under argon in deoxygenated MOPS-K+ buffer containing 100 μM sodium ascorbate as a reducing agent. Quantum yields were determined using norharmane in 0.1 N H2SO4 as the fluorescence standard (Φf = 0.58).21

Analyte selectivity

A 5 μM solution (100 mL) of 1 in 10 mM pH 7.2 MOPS buffer was prepared and the fluorescence spectrum was recorded over the emission range 400 to 700 nm with 380 nm excitation. Each cation tested was added to a 3 mL aliquot of the probe solution. The solution was mixed thoroughly, and the fluorescence spectrum was recorded after a 1 minute equilibration period. Emission spectra were integrated over the range of 486-526 nm, and the resulting intensities were divided by that of the free probe. Metal cations were supplied as aqueous stock solutions of the following salts: Mg(II), Ca(II), Co(II), and Ni(II) as nitrates, Na+ as NaClO4, Cd(II) as CdCl2, Hg(II) as Hg(OAc)2, and Mn(II), Fe(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) as sulfates. CuI(MeCN)M4PF6 was supplied as a 2.5 mM stock solution in MeCN. To avoid aerial oxidation, Fe(II) stock solution was prepared immediately before use.

Picosecond fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence decay data of 1-Cu(I) (5 μM), CTAP-2-Cu(I) (5 μM), and 11 (2 μM) were acquired at the respective emission maxima using a single photon counting spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments, LifeSpec Series) equipped with a pulsed laser diode as the excitation source (372 nm, FWHM = 80 ps, 10 MHz repetition rate, 1024 channel resolution). Sample solutions of the fluorophore saturated with Cu(I) were prepared based on steady-state fluorescence titrations as described above, and the steady state spectrum was checked after each decay measurement to confirm stability of the solution. The time decay data were analyzed by non-linear least squares fitting with deconvolution of the instrumental response function using the FluoFit software package.22

Potentiometry

To determine the pKa of probe 1, spectrophotometric titrations (10 cm path length) were carried out at a 2.8 μM ligand concentration and 0.1 M KCl as ionic background by varying −log[H3O+] from 3 to 2 with the addition of 0.1M HCl. In the −log[H3O+] range from 2 to 1, the amount of KCl present was adjusted downward such that the ionic strength of the solution remained constant at 0.1 M. The data were analyzed by non-linear least-squares fitting using the Specfit software package.23

Complex stability constants

For the determination of the Cu(I) stability constant of 1 we used acetonitrile as competing ligand. Titrations were carried out at 5 μM concentration of 1 in deoxygenated PIPBS buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0, 60 mM KClO4 ionic background) by either (a) adding aliquots of 0.25 μM CuSO4 at constant acetonitrile concentration (0.7 M) and 100 μM sodium ascorbate (for in situ reduction to Cu(I)) or (b) varying the acetonitrile concentration from 0 to 1.6 M while keeping the Cu(I) concentration constant at 3.6 μM (formed by in situ reduction of copper(II) sulfate with 50 μM sodium ascorbate). The data were analyzed by non-linear least squares fitting with Specfit using published Cu(I)/CH3CN stability constants (log β1 = 2.63, log β2 = 4.02, and log β3 = 4.29).24 In method (b), the data were corrected for volume changes with each acetonitrile addition.

Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammograms were acquired in deoxygenated 10 mM PIPBS buffer, pH 5, containing 0.1M KClO4 as the electrolyte using a CH-Instruments potentiostat. Compound 1 was analyzed at a concentration of 70 μM in the presence of 30 μM [Cu(I)(CH3CN)4]PF6 in a single compartment cell with a glassy carbon working electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and an aqueous Ag/AgCl reference electrode (1 M KCl). The potentials were referenced to ferrocenium (0.40 vs. SHE)25 or ferroin (1.112 vs. SHE)11 as external standards. Measurements were performed with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM067169) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Domaille DW, Que EL, Chang CJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:168. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Que EL, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1517. doi: 10.1021/cr078203u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McRae R, Bagchi P, Sumalekshmy S, Fahrni CJ. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4780. doi: 10.1021/cr900223a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nolan EM, Lippard SJ. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:193. doi: 10.1021/ar8001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tomat E, Lippard SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:225. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sumalekshmy S, Fahrni CJ. Chem Mat. 2011;23:483. doi: 10.1021/cm1021905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang Z, Lippard SJ. Methods in Enzymology, Vol 505: Imaging and Spectroscopic Analysis of Living Cells: Live Cell Imaging of Cellular Elements and Functions. 2012;505:445. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-388448-0.00031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mbatia HW, Burdette SC. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7212–7224. doi: 10.1021/bi3001769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapisarda VA, Volentini SI, Farias RN, Massa EM. Anal Biochem. 2002;307:105. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cody J, Dennisson J, Gilmore J, VanDerveer DG, Henary MM, Gabrielli A, Sherrill CD, Zhang YY, Pan CP, Burda C, Fahrni CJ. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:4918. doi: 10.1021/ic034529j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan MT, Bagchi P, Fahrni CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15906. doi: 10.1021/ja207004v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhry AF, Verma M, Morgan MT, Henary MM, Siegel N, Hales JM, Perry JW, Fahrni CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:737. doi: 10.1021/ja908326z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma M, Chaudhry AF, Morgan MT, Fahrni CJ. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:363. doi: 10.1039/b918311f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cody J, Fahrni CJ. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:11099. [Google Scholar]; Zeng L, Miller EW, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10. doi: 10.1021/ja055064u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dodani SC, Domaille DW, Nam CI, Miller EW, Finney LA, Vogt S, Chang CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dodani SC, Leary SC, Cobine PA, Winge DR, Chang CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8606. doi: 10.1021/ja2004158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lim CS, Han JH, Kim CW, Kang MY, Kang DW, Cho BR. Chem Commun. 2011;47:7146. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11568e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cao XW, Lin WY, Wan W. Chem Commun. 2012;48:6247. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32114a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, McRae R, Henary MM, Patel R, Lai B, Vogt S, Fahrni CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406547102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhry AF, Mandal S, Hardcastle KI, Fahrni CJ. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1016. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00024A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akao A, Nonoyama N, Yasuda N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:5337. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buter J, Kellogg RM. J Org Chem. 1981;46:4481. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambundo EA, Deydier MV, Grall AJ, Aguera-Vega N, Dressel LT, Cooper TH, Heeg MJ, Ochrymowycz LA, Rorabacher DB. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4233. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardo MM, Schroeder RR, Rorabacher DB. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:1241. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balakrishnan KP, Kaden TA, Siegfried L, Zuberbühler AD. Helv Chim Acta. 1984;67:1060. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krezel A, Bal W. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:161. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernardo MM, Schroeder RR, Rorabacher DB. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:1241. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirayama T, Van de Bittner GC, Gray LW, Lutsenko S, Chang CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113729109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cody J, Mandal S, Yang L, Fahrni CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13023. doi: 10.1021/ja803074y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson RS, Pratt JE. Photochem Photobiol. 1984;40:23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahrni CJ, Yang LC, VanDerveer DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3799. doi: 10.1021/ja028266o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizono N, Sugo M, Machida M, Oda K. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11622. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardo A, Reyman D, Poyato JML, Medina F. J Lumin. 1992;51:269. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enderlein J, Erdmann R. Optics Commun. 1997;134:371. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binstead RA, Zuberbühler AD. SPECFIT Global Analysis System 3.0.27. Spectrum Software Associates; Marlborough MA 01752: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamau P, Jordan RB. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:3879. doi: 10.1021/ic001447b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koepp H-M, Wendt H, Strehlow H. Z Elektrochem. 1960;64:483. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.