Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the transition from substance abuse to substance dependence. Objectives: This study aims to estimate the cumulative probability of developing dependence and to identify predictors of transition to dependence among individuals with lifetime alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine abuse.

Methods:

Analyses were done for the subsample of individuals with lifetime alcohol abuse (n = 7802), cannabis abuse (n = 2832), or cocaine abuse (n = 815) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Estimated projections of the cumulative probability of transitioning from abuse to dependence were obtained by the standard actuarial method. Discrete-time survival analyses with time-varying covariates were implemented to identify predictors of transition to dependence.

Results:

Lifetime cumulative probability estimates indicated that 26.6% of individuals with alcohol abuse, 9.4% of individuals with cannabis abuse, and 15.6% of individuals with cocaine abuse transition from abuse to dependence at some point in their lives. Half of the transitions of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine dependence occurred approximately 3.16, 1.83, and 1.42 years after abuse onset, respectively. Several sociodemographic, psychopathological, and substance use-related variables predicted transition from abuse to dependence for all of the substances assessed.

Conclusion:

The majority of individuals with abuse do not transition to dependence. Lifetime cumulative probability of transition from abuse to dependence was highest for alcohol, followed by cocaine and lastly cannabis. Time from onset of abuse to dependence was shorter for cocaine, followed by cannabis and alcohol. Although some predictors of transition were common across substances, other predictors were specific for certain substances.

Keywords: transition, abuse, dependence, cannabis, alcohol, cocaine

INTRODUCTION

Substance dependence is associated with a broad range of negative consequences and represents a tremendous burden to individuals and society (1-3). About 2.0% of adults living in the United States (US) had a DSM-IV drug use disorder in the prior 12 months (1.4% abuse, 0.6% dependence), and 10.3% reported a drug use disorder at any point in their lifetime (7.7% abuse, 2.6% dependence) (4). While several sociodemographic correlates were associated with greater risk of both drug abuse and dependence, other correlates were specific only for abuse or only for dependence (4). Furthermore, recent research showed that alcohol abuse/drug abuse and alcohol dependence/drug dependence populations are not homogeneous and require elucidation of the subgroups to identify etiologies (5,6). These findings highlight the importance of disaggregating different levels of severity among the same spectrum (7).

Factor analytic studies indicate that although the diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV abuse and dependence diagnosis load on different factors (8-11), these factors are highly correlated (12,13), supporting the unification of these two conditions in one disorder of variable severity for DSM-5 (14). Furthermore, although abuse and dependence vary in terms of severity (15,16), several studies have indicated that abuse tends to represent DSM-5 mild/moderate substance use disorder, while dependence is similar to DSM-5 severe substance use disorder (17,18). Therefore, examining transitions from abuse to dependence could be understood as examining transitions between different levels of severity (19,20). That would be in line with previous studies reporting a lower quality of life and psychological functioning of patients with dependence compared with those with abuse (19,20). Several studies have examined predictors of transition to substance dependence, but most of these studies have focused on the transition from use to dependence (19,21-26). Much less is known about the transition from abuse to dependence. For those reasons, identifying risk factors for the transition from a milder substance use disorder, represented in abuse, to dependence is a crucial step in understanding the etiology of substance use disorders, identifying individuals vulnerable to more severe levels of addiction and developing effective treatment and preventive interventions.

Moreover, studying the probability and length of time of transition from abuse to dependence is a useful alternative to estimating the addictive liability of substances, because it examines individuals that have already faced problems due to their use of substances (27). Despite these facts, little is known about the transition from abuse to dependence because most studies examining predictors of transition to substance dependence or estimating the addictive potential of different substances have focused exclusively on the transition from use to dependence (19,21-25).

Existing research suggests that early age of onset of substance use, low educational attainment, urban residency, and being previously married increase the risk of transition from abuse to dependence (28-30). Findings about race are mixed. One study suggested that white race (29) increased the risk of transition but another study failed to replicate that finding (28). Prior research also suggests that the length of time and rate of transition from onset of abuse to dependence varies greatly across drugs (27,31,32).

Important questions remain regarding predictors of transition from abuse to dependence. Some studies examined all substances together (29,30) or focused on a single substance (28), precluding formal examination of similarities and differences of predictors across substances. Other studies used high-risk or clinical populations (27,29,31), focused on certain geographical regions (27,29,31), or examined a limited number of sociodemographic variables (28). No published study has examined psychiatric comorbidity as a possible predictor of transition, despite the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders among individuals with substance use disorders.

We sought to build on prior work by drawing on data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large nationally representative study of the US adult population (33). The main goals of this study were to (1) estimate the cumulative probability of developing dependence among individuals with lifetime alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine abuse (the drugs with the highest levels of abuse or dependence in the United States) (2); (2) estimate the rate of transition from substance abuse to dependence for the three substances; and (3) assess the association between several sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidity, and drug use-related variables for the risk of transition to dependence among individuals with abuse.

METHODS

Sample

The NESARC target population at Wave 1 was the civilian noninstitutionalized population 18 years and older residing in households and group quarters. The final sample included 43,093 respondents. Blacks, Hispanics, and adults 18–24 were oversampled, with data adjusted for oversampling and household- and person-level nonresponse. The overall survey response rate was 81%. Data were adjusted using the 2000 decennial census, to be representative of the US civilian population for a variety of sociodemographic variables. Interviews were conducted by experienced lay interviewers with extensive training and supervision (34,35). All procedures, including informed consent, received full human subjects review and approval from the US Census Bureau and US Office of Management and Budget. This study examined the data of the subsample of individuals with lifetime alcohol abuse (n = 7802), cannabis abuse (n = 2832), or cocaine abuse (n = 815) at Wave 1 interview who did not develop dependence prior to abuse on that substance.

Data were collected using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV) (36). The AUDADIS-IV is a structured diagnostic interview, developed to advance measurement of substance use and mental disorders in large-scale surveys (37). Computer algorithms produced DSM-IV diagnoses based on AUDADIS-IV data.

Measures

Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered DSM-IV criteria for alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine. Age of substance use onset, substance abuse, and substance dependence were assessed via extensive items covering the DSM-IV criteria (38). Age of substance use onset was determined by asking respondents about the age at which they first “had at least 1 drink of any kind of alcohol (not counting small tastes or sips)” (alcohol use), used cannabis (cannabis use), or used cocaine or crack (cocaine use). Drug-specific dependence criteria were aggregated to yield diagnoses of drug dependence for each substance. The good to excellent test-retest reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses is well documented in clinical and general population samples (36,39).

A previous diagnosis of a SUD (abuse or dependence) to any substance other than the one under examination was also included as a covariate in the analysis of transition.

Mood disorders included DSM-IV primary major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar I and II disorders. Anxiety disorders included DSM-IV panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. AUDADIS-IV methods to diagnose these disorders are described in detail elsewhere (35,40-42).

Avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, and antisocial personality disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis at Wave 1 and described in detail elsewhere (35,35). Personality disorders’ diagnosis required long-term patterns of social and occupational impairment (37).

Test-retest reliabilities for AUDADIS-IV mood, anxiety, and personality disorders’ diagnoses in the general population and clinical settings were fair to good (κ = .40 to .77) (36,39,43). Convergent validity was good to excellent for all affective, anxiety, and personality disorders diagnoses (35,40), and selected diagnoses showed good agreement (κ = .64 to .68) with psychiatrist reappraisals (43).

Self-reported race/ethnicity was recorded into five groups: Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans. Other sociodemographic characteristics included gender, age, urbanicity (urban vs. rural), nativity (US-born vs. foreign-born), educational attainment, individual and family income, marital status, and employment status. Early substance use onset, defined as before age 14 (44), and family history of SUD (any alcohol or drug use disorder among first-degree relatives) were also included as substance use-related covariates.

Analyses

Weighted frequencies and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed to characterize the sample. Estimated projections of the cumulative probability of transitioning from abuse to dependence in the general population were obtained by the standard actuarial method (45) as implemented in PROC LIFETEST in SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Separate curves were generated for each substance. We present estimates of the probability of transition to dependence during the first year and first decade after substance abuse onset, as well as the cumulative probability of lifetime transition. Individuals with onset of dependence before abuse were not included in the analyses, representing 16.3% of individuals with lifetime alcohol abuse, 3.6% of those with lifetime cannabis dependence, and 15.1% of those with lifetime cocaine dependence. Including respondents with onset of substance dependence before onset of abuse resulted in similar findings to when they were excluded. For that reason those results are not presented, but are available on request.

Univariate and multivariable survival analyses with time-varying covariates (with person-year as the unit of analysis) (46) were implemented using SUDAAN version 9.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park). These unadjusted and adjusted models aimed at assessing the association between sociodemographic, psychiatric comorbidity, and substance use-related covariates and the hazards of transition to substance dependence. The person-year variable was defined as the number of years from substance abuse onset to age of dependence onset or age at Wave 1 interview (for censored cases). Education, marital status, and presence of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and SUD other than the one under examination were included as time-dependent covariates. Stepwise model selection procedures were used to identify independent correlates based on likelihood-ratio tests. Taylor series linearization methods implemented in SUDAAN were used to estimate standard errors and test for significance, taking into account the complex survey design.

To evaluate the presence of a forward telescoping bias (47) and recall bias among individuals who transitioned from abuse to dependence, we examined the correlation between the years from abuse to the NESARC interview and the years from abuse to dependence.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. The highest proportion of individuals with alcohol abuse was among persons 45 years of age or older, whereas the highest proportion of individuals with cannabis and cocaine abuse was among persons 30–44 years of age. For all three types of substances, the majority of respondents with substance abuse were male, white, US-born, and living in urban areas, had at least some college education, and had an individual income of less than 20,000 dollars per year at the time of the interview. Also, for all three substances, the largest group was married or living with someone and was currently employed or had a history of past employment.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic, psychopathologic, and substance abuse-related characteristics of individuals with lifetime history of alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine abuse by type of substance at NESARC Wave 1.

| Characteristic | Alcohol abuse (n = 7802) |

Cannabis abuse (n = 2832) |

Cocaine abuse (n = 815) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95%CI | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–29 | 19.07 | (18.03–20.14) | 30.02 | (27.69–32.45) | 18.62 | (15.06–22.78) |

| 30–44 | 37.53 | (36.31–38.75) | 42.72 | (40.30–45.18) | 54.09 | (49.50–58.62) |

| >45 | 43.41 | (42.03–44.80) | 27.26 | (25.16–29.47) | 27.29 | (23.47–31.47) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 67.45 | (66.11–68.77) | 67.48 | (65.34–69.55) | 69.31 | (65.71–72.68) |

| Female | 32.55 | (31.23–33.89) | 32.52 | (30.45–34.66) | 30.69 | (27.32–34.29) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Whites | 80.69 | (78.39–82.80) | 78.12 | (75.64–80.42) | 75.99 | (71.82–79.71) |

| Blacks | 7.17 | (6.27–8.19) | 9.24 | (7.90–10.80) | 8.56 | (6.77–10.77) |

| Hispanics | 7.76 | (6.14–9.77) | 7.31 | (5.91–9.00) | 9.40 | (7.01–12.51) |

| Asians | 1.46 | (1.01–2.11) | 1.47 | (.96–2.23) | 1.23 | (.62–2.45) |

| Native Americans | 2.92 | (2.40–3.55) | 3.86 | (2.93–5.07) | 4.82 | (2.91–7.86) |

| US-born | ||||||

| Yes | 94.33 | (92.91–95.49) | 96.01 | (94.70–97.01) | 96.09 | (93.92–97.51) |

| No | 5.67 | (4.51–7.09) | 3.99 | (2.99–5.30) | 3.91 | (2.49–6.08) |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Rural | 21.46 | (18.30–24.99) | 19.89 | (16.46–23.82) | 16.16 | (11.87–21.63) |

| Urban | 78.54 | (75.01–81.70) | 80.11 | (76.18–83.54) | 83.84 | (78.37–88.13) |

| Education | ||||||

| <High school | 11.79 | (10.69–12.97) | 12.17 | (10.68–13.84) | 12.88 | (10.03–16.39) |

| High school | 26.51 | (25.05–28.03) | 27.99 | (25.80–30.29) | 31.85 | (27.95–36.01) |

| ≥College | 61.70 | (59.89–63.49) | 59.84 | (57.39–62.25) | 55.28 | (51.27–59.22) |

| Individual income | ||||||

| 0–$19,999 | 34.47 | (32.95–36.01) | 41.53 | (38.95–44.15) | 38.10 | (33.62–42.79) |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 24.24 | (22.93–25.61) | 24.28 | (22.22–26.46) | 23.23 | (19.92–26.91) |

| $35,000–$69,999 | 28.57 | (27.34–29.83) | 24.33 | (22.24–26.56) | 29.17 | (25.47–33.16) |

| ≥$70,000 | 12.72 | (11.33–14.26) | 9.86 | (8.26–11.73) | 9.50 | (7.11–12.58) |

| Family income | ||||||

| 0–$19,999 | 16.98 | (15.82–18.22) | 21.04 | (19.28–22.93) | 19.61 | (16.64–22.96) |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 19.03 | (17.90–20.21) | 19.55 | (17.91–21.30) | 19.90 | (16.99–23.18) |

| $35,000–$69,999 | 34.00 | (32.55–35.47) | 32.38 | (30.30–34.53) | 37.67 | (33.49–42.05) |

| ≥$70,000 | 30.00 | (27.94–32.14) | 27.03 | (24.44–29.79) | 22.81 | (18.73–27.48) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 64.49 | (63.12–65.84) | 55.30 | (53.17–57.41) | 55.17 | (51.13–59.14) |

| Divorced/separated | 14.11 | (13.20–15.07) | 14.75 | (13.26–16.37) | 20.04 | (17.12–23.31) |

| Widowed | 2.56 | (2.24–2.93) | 1.02 | (0.63–1.66) | .78 | (.37–1.64) |

| Never married | 18.84 | (17.73–20.00) | 28.93 | (27.08–30.84) | 24.01 | (20.51–27.90) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Ever employed | 89.78 | (88.92–90.57) | 94.50 | (93.48–95.37) | 92.07 | (89.84–93.84) |

| Never employed | 10.22 | (9.43–11.08) | 5.50 | (4.63–6.52) | 7.93 | (6.16–10.16) |

| Psychopathology | ||||||

| Any personality disorder | 22.46 | (21.21–23.75) | 32.80 | (30.48–35.22) | 37.48 | (33.37–41.77) |

| Any mood disorder | 24.15 | (22.96–25.39) | 34.51 | (32.27–36.83) | 34.69 | (30.49–39.14) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 22.37 | (21.17–23.63) | 28.22 | (25.99–30.57) | 26.08 | (22.34–30.20) |

| Any conduct disorder | 1.67 | (1.37–2.03) | 2.14 | (1.57–2.91) | 2.11 | (1.17–3.77) |

| Any psychotic disorder | 1.00 | (.79–1.27) | 2.43 | (1.74–3.38) | 2.48 | (1.52–4.00) |

| Substance abuse-related characteristics | ||||||

| Early onset1 (before age 14) | 12.47 | (11.63–13.37) | 21.78 | (19.84–23.85) | 3.52 | (2.31–5.34) |

| Late onset1 | 87.53 | (86.63–88.37) | 78.22 | (76.15–80.16) | 96.48 | (94.66–97.69) |

| Nicotine dependence | 32.35 | (30.96–33.77) | 49.35 | (46.87–51.83) | 49.79 | (45.50–54.08) |

| Alcohol dependence | 20.73 | (19.50–22.01) | 46.13 | (43.91–48.37) | 55.80 | (51.60–59.93) |

| Cannabis dependence | 2.78 | (2.39–3.23) | 7.42 | (6.24–8.80) | 11.40 | (8.89–14.50) |

| Cocaine dependence | 2.24 | (1.87–2.68) | 6.05 | (5.06–7.23) | 14.78 | (12.04–18.01) |

| Family history of SUD | 50.51 | (49.08–51.94) | 59.70 | (57.44–61.92) | 72.25 | (68.48–75.72) |

Note:

Use onset for the substance of interest described in the column (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine).

Psychiatric and Substance Use Comorbid Disorders

Psychiatric comorbid disorders and other substance use-related characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Almost one quarter of individuals with alcohol abuse and about one-third of those with cannabis and cocaine abuse had a personality or mood disorder. About one quarter of individuals with abuse on any of the substances assessed had an anxiety disorder. The majority of respondents initiated the use of the substance under consideration after age 14. Almost 50% of individuals with cannabis or cocaine abuse had a lifetime history of nicotine or alcohol dependence in the year prior to Wave 1. Also, 20.73% of individuals with a lifetime history of alcohol abuse, 7.42% of those with a history of cannabis abuse, and 14.78% of those with a history of cocaine abuse reported dependence to the same substance in the year prior to the interview. The majority of those with cannabis or cocaine abuse had a family history of SUD.

Probability of Transitioning to Substance Dependence among Individuals with Substance Abuse

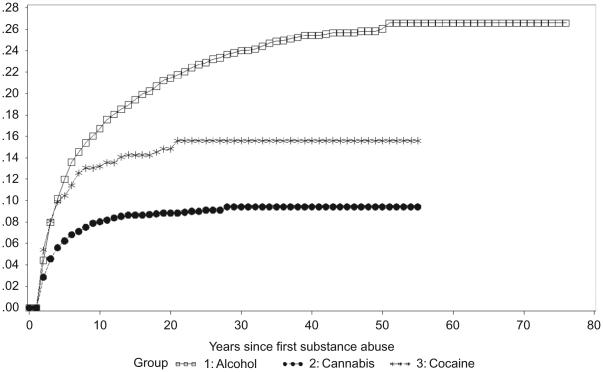

During the first year after the diagnoses of substance abuse were met, the probability of transition to dependence was 4.5% for alcohol, 2.8% for cannabis, and 5.5% for cocaine. The estimated cumulative probabilities of transition to dependence a decade after the onset of abuse were 16.7% for alcohol, 8% for cannabis, and 13.2% for cocaine. Lifetime cumulative probability estimates indicated that 26.6% of individuals with alcohol abuse, 9.4% of individuals with cannabis abuse, and 15.6% of individuals with cocaine abuse would become dependent on those substances at some time in their lives. Half of the cases of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine dependence were observed approximately 3.16, 1.83, and 1.42 years after abuse onset, respectively (Figure 1). The correlation between the years from abuse onset to NESARC interview and years from abuse onset to onset of dependence was r = .42, p = < .0001 for alcohol; r = .35, p = .01 for cannabis; and r = .2, p = .09 for cocaine.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative probability of transitioning to dependence on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine among individuals with abuse of these substances.

Sociodemographic Predictors of Transition from Substance Abuse to Dependence

After controlling for the effect of socioeconomic characteristic, psychiatric comorbidity, and drug use covariates, older age predicted lower risk of transition to alcohol and cannabis dependence (Table 3). Males were more likely than women to progress from alcohol abuse to dependence. Compared to whites, Asians were more likely to transition from cocaine abuse to dependence. Respondents living in urban areas were more likely to transit to cannabis dependence. Being married decreased the risk of transition to alcohol and cocaine dependence.

TABLE 3.

Predictors of progression from abuse to dependence on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine among individuals with specific substance abuse. Multivariable results of survival analyses.

| Characteristics | Alcohol dependence |

Cannabis dependence |

Cocaine dependence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–29 | 4.08 | (3.34–5.00) | 2.59 | (1.48–4.56) | ||

| 30–44 | 1.69 | (1.43–2.00) | 1.14 | (.66–1.98) | ||

| >451 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.28 | (1.11–1.47) | ||||

| Female1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Whites1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Blacks | 1.10 | (.70–1.72) | 1.93 | (.94–3.98) | ||

| Hispanics | .55 | (.28–1.09) | 1.12 | (.61–2.06) | ||

| Asians | 1.16 | (.35–3.91) | 5.04 | (1.43–17.83) | ||

| Native Americans | 1.72 | (.90–3.26) | .89 | (.26–3.07) | ||

| US-born | ||||||

| Yes | .40 | (.15–1.06) | ||||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||||

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Rural1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||||

| Urban | 2.28 | (1.38–3.76) | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Never married | 1.78 | (1.46–2.17) | .77 | (.40–1.47) | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 2.19 | (1.79–2.69) | 2.44 | (1.29–4.62) | ||

| Any personality disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 1.54 | (1.34–1.77) | 2.48 | (1.80–3.43) | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Any mood disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 2.11 | (1.64–2.72) | 2.09 | (1.27–3.43) | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Any psychotic disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 1.98 | (1.35–2.91) | 3.53 | (1.35–9.23) | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Specific substance use onset | ||||||

| Early (before age 14) | 1.25 | (1.06–1.46) | ||||

| Late1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||||

| Nicotine dependence | ||||||

| Yes | 2.92 | (2.46–3.46) | 1.64 | (1.07–2.53) | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Alcohol dependence | ||||||

| Yes | NA | NA | 1.98 | (1.43–2.75) | ||

| No1 | NA | NA | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Cannabis dependence | ||||||

| Yes | 3.15 | (2.09–4.74) | NA | NA | 3.17 | (1.28–7.90) |

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | NA | NA | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) |

| Cocaine dependence | ||||||

| Yes | 2.99 | (1.71–5.22) | 10.23 | (5.93–17.66) | NA | NA |

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | NA | NA |

| Family history of SUD | ||||||

| Yes | 1.38 | (1.21–1.57) | ||||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||||

Note:

Reference category. Significant results (p < .05) are in bold.

Psychiatric and Substance Use-Related Predictors of Transition from Substance Abuse to Dependence

After controlling for the effect of other covariates, a history of personality or mood disorders predicted the transition from abuse to alcohol and cannabis dependence (Table 3).

Individuals with alcohol or cocaine abuse and a history of any psychotic disorder had an increased risk of becoming dependent on these substances. Compared to respondents with onset of use after age 14 years, respondents with earlier onset of use were more likely to transit to alcohol dependence. A history of nicotine dependence increased the risk of transition from alcohol and cannabis abuse to dependence. Individuals with alcohol dependence were at higher risk for cannabis dependence. A history of cannabis or cocaine dependence increased the risk of transition for the other substances assessed. A family history of SUD predicted the transition to dependence among individuals with alcohol abuse.

DISCUSSION

In a large, nationally representative sample of US adults, the lifetime cumulative probability of transition from substance abuse to dependence was the highest for alcohol (26.6%), followed by cocaine (15.6%) and lastly cannabis (9.4%), that is, the majority of individuals with abuse did not transition to dependence. However, the time from onset of abuse to dependence was shorter for cocaine, followed by cannabis and alcohol. Although some predictors of transition were common across substances, other predictors were specific for certain substances.

Several factors, including legal status, higher social acceptability, and more availability of alcohol compared to other substances could explain its higher rates of transition (48-50). Higher availability and mean consumption of alcoholic beverages are related to a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorders (48,51). The legal status and social acceptability of alcohol may also lead individuals to consume over longer periods of their lives, extending the period during which biological mechanisms related to addiction can be affected and increasing the time at risk of transition.

A previous study found that individuals with alcohol use were more likely to transition to dependence followed by cocaine and then cannabis (52). The current study extends those findings by indicating that the probabilities of transition from abuse to dependence follow the same pattern, but the rates of transition are considerably higher. Our results, in line with previous findings (28-30,53), suggest that although abuse of one substance increases the risk of transition to dependence, the majority of individuals with abuse do not transition to dependence. The interplay of individual vulnerability, environment, and exposure to risk factors may determine the differences in trajectories among individuals with substances use disorders.

In accord with previous research (27,31,32,54), time to transition was shorter for cocaine, followed by cannabis and alcohol. These patterns of transition are also consistent with findings of a faster transition from use to dependence on cocaine than from use to dependence on cannabis and alcohol (52). A shorter lag period from abuse to dependence on cocaine could be indicative of greater addictive liability and may be related to its pharmacokinetic properties (27,55). We did not find a negative correlation between years from onset of abuse to time of NESARC interview and years elapsed from onset of abuse to onset of dependence, indicating that forward telescoping and recall biases, if present, are unlikely to be large. Rather, we found a nonsignificant correlation in the case of cocaine and significant positive correlations in the case of alcohol and cannabis. The reasons for these positive correlations are unknown. In the case of alcohol, they may be related to increases in the volume of drinking, frequency of intoxication, and reduction in utilization of treatment services by more recent cohorts (56-58) along with increasingly more tolerant societal norms and attitudes toward alcohol consumption (59). Increases in the potency of cannabis could contribute to explaining the faster transition from abuse to dependence of respondents with an abuse onset closer to NESARC interview (60,61).

Individuals with alcohol or cannabis abuse and a history of any mood or personality disorder, and individuals with alcohol or cocaine abuse and a history of psychotic disorders showed increased risk of becoming dependent. Previous studies have shown that mental disorders increase the risk of substance dependence (4,62-65), as well as the risk of transition from use to dependence (52). Our findings document that mental disorders also increase the risk of transition to dependence among individuals with abuse. The association between mental disorders and substance use has been extensively documented (4,66-68). Several mechanisms may contribute to these associations, including shared genetic predisposition, correlated liabilities, environmental factors, and unidirectional relationships, in which one condition influences the other, or even bidirectional relationships (65-70). Early treatment or prevention of these comorbid disorders could contribute to reducing the risk of transition (65).

A history of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or nicotine dependence predisposed individuals with substance abuse to the development of dependence on the other substances. Many drugs of abuse share common mechanisms of action (71). Consumption of more than one drug may lead to faster neuroadaptations (72,73). Also, drug interactions resulting in decreased adverse effects and synergism of drug effect may favor use of different substances at the same time (72,74,75). Higher genetic liability has been associated with polysubstance use, and allelic variations in several genes have been associated with predisposition to polysubstance use disorders (73,76,77). Polysubstance use behaviors may also be strengthened by environmental influences that allow an easier access to several drugs (78,79).

Males were more likely than women to progress from alcohol abuse to dependence, consistent with prior analyses indicating that, in the general population, the progression from alcohol use to dependence is more common in men than in women (80,81). Men have higher enzymatic activity of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to higher consumption of alcohol and less adverse effects facilitating tolerance (82,83). Previous studies have associated tolerance with a higher transition to alcohol dependence from abuse (84). Other factors like peer behavior and socialization into traditional gender roles could explain part of the difference (30,85).

In the univariate analyses, we found that Blacks and Asians were more likely to transition to cocaine dependence, while Hispanics and Asians were more likely to alcohol dependence. Racial differences in substance use disorders may be partly due to differences in patterns of use that can be influenced by social and cultural factors and may be related to diverse sociocultural contexts of the individuals (86,87). The effect of racial disparities in healthcare access and services may also have contributed to differences in the rates of transition (88-92).

Several sociodemographic, psychopathologic, and substance use-related predictors of transition from abuse to dependence differed from those of transition from use to dependence (52). For example, a history of psychotic disorder increased the risk of transition from alcohol or cocaine abuse to dependence, but not from alcohol or cocaine use to dependence. Respondents with early onset of alcohol use were more likely to transition from alcohol abuse to dependence, but not from alcohol use to dependence. At the same time, although some previously identified risk factors of transition from use to dependence also predicted transition from abuse to dependence (e.g., dependence on another substance, mood or personality disorders), other risk factors of transition did not predict abuse to dependence, such as male gender for cannabis, black race for cocaine, or anxiety disorder for alcohol and cannabis (52). Our findings suggest that risk factors for dependence vary across the different stages of progression from use to dependence. Although treatment interventions that target the main psychopathological risk factors for dependence should be effective regardless of whether individuals are only using or have already progressed to abuse, certain risk factors may offer opportunities for stage-specific interventions.

Our study has limitations common to most large-scale surveys. First, information on substance use and SUD was based on self-report and not confirmed by objective methods. Second, diagnoses may be subject to recall bias and to cognitive impairment associated with the use of drugs. However, those biases, if present, are unlikely to be large, as indicated by absence of negative correlations between years from abuse to NESARC interview and years from abuse onset to onset of dependence. Third, the NESARC excludes institutionalized populations, who have an increased probability of having a diagnosis of substance dependence. It has also some important strengths, including its large sample size, generalizability, careful methodology, and the inclusion of individuals who abused only one substance as well as those who abused multiple substances, allowing the use of those substances as predictors in multivariable models.

Despite the limitations, our study indicates that although the speed of transition from abuse to dependence is fastest from cocaine, followed by cannabis and alcohol, the cumulative probability of transition is highest for alcohol, followed by cocaine and cannabis. A history of mood, anxiety, personality, or substance use disorders strongly predisposed individuals to transition. Identifying and targeting risk factors for substance abuse and developing effective interventions for its treatment may be an important avenue to decrease the prevalence of substance dependence.

TABLE 2.

Predictors of transition from abuse to dependence on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine among individuals with specific substance abuse. Univariate results of survival analyses.

| Characteristics | Alcohol dependence |

Cannabis dependence |

Cocaine dependence |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Age group | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 5.02 | (4.15–6.08) | 3.29 | (1.96–5.52) | .93 | (.41–2.13) | |||

| 30–44 | 1.79 | (1.53–2.09) | 1.40 | (.83–2.35) | .58 | (.30–1.14) | |||

| >45 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1.04 | (.92–1.18) | 1.18 | (.86–1.63) | .81 | (.50–1.30) | |||

| Female1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Whites1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Blacks | 1.07 | (.87–1.32) | 1.21 | (.78–1.87) | 2.27 | (1.17–4.38) | |||

| Hispanics | 1.38 | (1.10–1.72) | 1.05 | (.60–1.83) | 1.07 | (.57–2.01) | |||

| Asians | 1.61 | (1.11–2.34) | 2.54 | (.93–6.90) | 4.64 | (1.25–17.30) | |||

| Native Americans | 1.14 | (.78–1.66) | 1.92 | (.98–3.74) | .86 | (.23–3.24) | |||

| US-born | |||||||||

| Yes | .92 | (.69–1.23) | .40 | (.17–.96) | .52 | (.20–1.37) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Urbanicity | |||||||||

| Rural1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Urban | 1.06 | (.90–1.24) | 2.18 | (1.31–3.61) | 1.07 | (.48–2.38) | |||

| Education (years) | .98 | (.95–1.00) | 1.00 | (.91–1.09) | .97 | (.87–1.07) | |||

| Individual income | |||||||||

| 0–$19,999 | 2.16 | (1.68–2.77) | 1.92 | (1.00–3.70) | 3.32 | (.99–11.15) | |||

| $20,000–$34,999 | 2.02 | (1.57–2.60) | 1.45 | (.76–2.75) | 2.60 | (.78–8.70) | |||

| $35,000–$69,999 | 1.40 | (1.10–1.80) | .97 | (.47–2.03) | 2.25 | (.64–7.87) | |||

| ≥70,0001 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Family income | |||||||||

| 0–$19,999 | 2.11 | (1.73–2.58) | 2.41 | (1.46–3.99) | 1.89 | (.94–3.82) | |||

| $20,000–$34,999 | 1.68 | (1.38–2.04) | 1.41 | (.80–2.46) | 1.35 | (.67–2.72) | |||

| $35,000–$69,999 | 1.31 | (1.09–1.57) | 1.51 | (.90–2.52) | 1.29 | (.66–2.52) | |||

| ≥70,0001 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Never married | 2.00 | (1.65–2.42) | 2.15 | (1.22–3.80) | .86 | (.45–1.62) | |||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 2.48 | (2.03–3.04) | 2.20 | (1.01–4.80) | 2.58 | (1.36–4.88) | |||

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Ever employed1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Never employed | .59 | (.48–.74) | .49 | (.23–1.05) | .54 | (.20–1.49) | |||

| Any personality disorder | |||||||||

| Yes | 2.25 | (1.98–2.55) | 3.36 | (2.44–4.62) | 1.43 | (.91–2.27) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Any mood disorder | |||||||||

| Yes | 3.61 | (2.92–4.47) | 3.58 | (2.26–5.67) | 1.71 | (.72–4.03) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Any anxiety disorder | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.86 | (1.41–2.47) | 2.38 | (1.23–4.61) | 1.18 | (.36–3.89) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Any conduct disorder | |||||||||

| Yes | .87 | (.56–1.34) | 1.55 | (.56–4.27) | <.01 | (<.01–<.01) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Any psychotic disorder | |||||||||

| Yes | 2.90 | (2.08–4.05) | 2.13 | (.94–4.83) | 3.79 | (1.31–10.94) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Specific substance use onset | |||||||||

| Early (before age 14) | 1.77 | (1.51–2.07) | 1.67 | (1.17–2.38) | .85 | (.30–2.42) | |||

| Late1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Nicotine dependence | |||||||||

| Yes | 4.36 | (3.72–5.13) | 2.83 | (1.88–4.26) | 1.95 | (.99–3.83) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

| Alcohol dependence | |||||||||

| Yes | NA | NA | NA | 2.95 | (2.09–4.16) | 1.59 | (.95–2.66) | ||

| No1 | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Cannabis dependence | |||||||||

| Yes | 8.58 | (6.22–11.83) | NA | NA | NA | 3.17 | (1.34–7.49) | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Cocaine dependence | |||||||||

| Yes | 8.27 | (5.26–13.00) | 14.22 | (8.28–24.42) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Family history of SUD | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.55 | (1.36–1.76) | 1.25 | (.88–1.77) | 1.58 | (.91–2.75) | |||

| No1 | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | |||

Note:

Reference category. Significant results (p < .05) are in bold.

Acknowledgments

The NESARC was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the sponsoring organizations. Work on this manuscript was supported by NIH grants DA019606, DA020783, DA023200, DA023973, and CA133050 (Dr. Blanco) and AA014223 and AA018111 (Dr. Hasin), by the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Drs. Blanco and Hasin), and by Spanish Ministry of Education grant PR2010-0501 (Dr. Secades-Villa).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson P. Global use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25(6):489–502. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC. Mortality associated with illegal drug use among adults in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(3):155–164. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.553977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz LY, Cox BJ, Clara IP, Oleski J, Sacevich T. Substance abuse versus dependence and the structure of common mental disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(6):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slade T, Grove R, Teesson M. A taxometric study of alcohol abuse and dependence in a general population sample: Evidence of dimensional latent structure and implications for DSM-V. Addiction. 2009;104(5):742–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulden JD, Thomas YF, Compton WM. Substance abuse in the United States: Findings from recent epidemiologic studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(5):353–359. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harford TC, Muthen BO. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: A multivariate analysis of DSM-IV symptom items in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(2):150–157. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muthen BO, Grant B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: Factor analysis of DSM-III-R and proposed DSM-IV criteria in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey. Addiction. 1993;88(8):1079–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthen BO. Factor analysis of alcohol abuse and dependence symptom items in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey. Addiction. 1995;90(5):637–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthen BO, Yi HY, Hasin DS, Stinson FS. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: Further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2–3):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynskey MT, Agrawal A. Psychometric properties of DSM assessments of illicit drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Psychol Med. 2007;37(9):1345–1355. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DSM-V Development . Substance Use Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Proposed Revision. Available at http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=431# Last accessed on November 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray LA, Miranda R, Chelminski I, Young D, Zimmerman M. Diagnostic orphans for alcohol use disorders in a treatment-seeking psychiatric sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1–2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36(7):931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Stallings M, Young S, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt J, Hopfer C, Crowley T. Toward DSM-V: An item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(11):1329–1339. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien C. Addiction and dependence in DSM-V. Addiction. 2010;106(5):866–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawson DA, Li TK, Chou SP, Grant BF. Transitions in and out of alcohol use disorders: Their associations with conditional changes in quality of life over a 3-year follow-up interval. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(1):84–92. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volk RJ, Cantor SB, Steinbauer JR, Cass AR. Alcohol use disorders, consumption patterns, and health-related quality of life of primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21(5):899–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behrendt S, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Lieb R, Beesdo K. Transitions from first substance use to substance use disorders in adolescence: Is early onset associated with a rapid escalation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1–3):68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CY, O’Brien MS, Anthony JC. Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo J, Collins LM, Hill KG, Hawkins JD. Developmental pathways to alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(6):799–808. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Sydow K, Lieb R, Pfister H, Hofler M, Wittchen HU. What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence? A 4-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68(1):49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence; developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;26(4):479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dierker L, Swendsen J, Rose J, He J, Merikangas K. Transitions to regular smoking and nicotine dependence in the Adolescent National Comorbidity Survey (NCS-A) Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(3):394–401. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridenour TA, Maldonado-Molina M, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL, Cottler LB. Factors associated with the transition from abuse to dependence among substance abusers: Implications for a measure of addictive liability. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Chiu WT, Dierker L, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Merikangas KR, Sampson N, Kessler R. Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use, disorders, and remission in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sussman S, Dent CW, Leu L. The one-year prospective prediction of substance abuse and dependence among high-risk adolescents. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12(4):373–386. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Glantz M, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Sociodemographic risk factors for alcohol and drug dependence: The 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1346–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridenour TA, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL, Cunningham-Williams RM. Is there a progression from abuse disorders to dependence disorders? Addiction. 2003;98(5):635–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridenour TA, Lanza ST, Donny EC, Clark DB. Different lengths of times for progressions in adolescent substance involvement. Addict Behav. 2006;31(6):962–983. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant BF, Kaplan KD. Source and Accuracy Statement for the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th xxv. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. p. 886. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1–3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Saha TD, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Smith S, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. The epidemiology of DSM-IV specific phobia in the USA: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2007;37(7):1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canino G, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Febo VE, Rubio-Stipec M, Fernandez RL. The Spanish HD. Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60(6):790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10(2):63–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machin D, Cheung YB, Parmar MKB. Survival Analysis: A Practical Approach. 2nd Wiley; Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins SP. Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bull Econ Stat. 1995;57(1):129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: An example from cigarette smoking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(3):119–129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caetano R, Cunradi C. Alcohol dependence: A public health perspective. Addiction. 2002;97(6):633–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dent CW, Grube JW, Biglan A. Community level alcohol availability and enforcement of possession laws as predictors of youth drinking. Prev Med. 2005;40(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pavis S, Cunninhanm-Burley S, Amos A. Alcohol consumption and young people: Exploring meaning and social context. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(3):311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rush BR, Gliksman L, Brook R. Alcohol availability, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related damage. I. the distribution of consumption model. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47(1):1–10. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez-Quintero C, Cobos JP, Hasin D, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115(1–2):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Bucholz KK, Reich T, Bierut L. Five-year clinical course associated with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence in a large group of men and women. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1084–1090. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reboussin BA, Anthony JC. Is there epidemiological evidence to support the idea that a cocaine dependence syndrome emerges soon after onset of cocaine use? Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31(9):2055–2064. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35(1):217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caetano R, Baruah J, Chartier KG. Ten-year trends (1992 to 2002) in sociodemographic predictors and indicators of alcohol abuse and dependence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(8):1458–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chartier KG, Caetano R. Trends in alcohol services utilization from 1991–1992 to 2001–2002: Ethnic group differences in the US population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(8):1485–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caetano R, Baruah J, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Ebama MS. Sociodemographic predictors of pattern and volume of alcohol consumption across Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites: 10-year trend (1992–2002) Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(10):1782–1792. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984 and 1995. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(6):659–668. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Arafat R, Yi B, Banahan BF., 3rd. Potency trends of delta9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated marijuana from 1980–1997. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(1):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Behrendt S, Beesdo-Baum K, Zimmermann P, Hofler M, Perkonigg A, Buhringer G, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. The role of mental disorders in the risk and speed of transition to alcohol use disorders among community youth. Psychol Med. 2011;41(5):1073–1085. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Glantz MD, Anthony JC, Berglund PA, Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Kalaydjian A, Merikangas KR, Ruscio AM, Swendsen J, Kessler RC. Mental disorders as risk factors for later substance dependence: Estimates of optimal prevention and treatment benefits. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1365–1377. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneier FR, Foose TE, Hasin DS, Heimberg RG, Liu SM, Grant BF, Blanco C. Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2010;40(6):977–988. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: Results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction. 2010;105(6):1117–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White HR, Xie M, Thompson W, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(3):210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(1):17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saban A, Flisher AJ. The association between psychopathology and substance use in young people: A review of the literature. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(1):37–47. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2010.10399784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Upadhyaya HP, Deas D, Brady KT, Kruesi M. Cigarette smoking and psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(11):1294–1305. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baker TE, Stockwell T, Barnes G, Holroyd CB. Individual differences in substance dependence: At the intersection of brain, behaviour and cognition. Addict Biol. 2011;16(3):458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J. Understanding polydrug use: Review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction. 2003;98(1):7–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schlaepfer IR, Hoft NR, Ehringer MA. The genetic components of alcohol and nicotine co-addiction: From genes to behavior. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(2):124–134. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bechtholt AJ, Mark GP. Enhancement of cocaine-seeking behavior by repeated nicotine exposure in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162(2):178–185. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Desai RI, Barber DJ, Terry P. Asymmetric generalization between the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and cocaine. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10(6–7):647–656. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sherva R, Kranzler HR, Yu Y, Logue MW, Poling J, Arias AJ, Anton RF, Oslin D, Farrer LA, Gelernter J. Variation in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes is associated with multiple substance dependence phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35(9):1921–1931. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang PW, Ishiguro H, Ohtsuki T, Hess J, Carillo F, Walther D, Onaivi ES, Arinami T, Uhl GR. Human cannabinoid receptor 1: 5’ exons, candidate regulatory regions, polymorphisms, haplotypes and association with polysubstance abuse. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(10):916–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Storr CL, Chen CY, Anthony JC. “Unequal opportunity”: Neighbourhood disadvantage and the chance to buy illegal drugs. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(3):231–237. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Into the world of illegal drug use: Exposure opportunity and other mechanisms linking the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(10):918–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, Hasin DS. Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: New evidence from two national surveys. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):969–976. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wittchen HU, Behrendt S, Hofler M, Perkonigg A, Lieb R, Buhringer G, Beesdo K. What are the high risk periods for incident substance use and transitions to abuse and dependence? Implications for early intervention and prevention. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(Suppl. 1):S16–S29. doi: 10.1002/mpr.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chrostek L, Jelski W, Szmitkowski M, Puchalski Z. Gender-related differences in hepatic activity of alcohol dehydrogenase isoenzymes and aldehyde dehydrogenase in humans. J Clin Lab Anal. 2003;17(3):93–96. doi: 10.1002/jcla.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L. Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. J Gen Psychol. 2006;133(4):357–374. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.357-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Behrendt S, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Lieb R, Low NC, Rehm J, Beesdo K. Risk and speed of transitions to first alcohol dependence symptoms in adolescents: A 10-year longitudinal community study in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1638–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(6):535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: Results from a national survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55(1):61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Galvan FH, Caetano R. Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(1):87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmidt L, Greenfield T, Mulia N. Unequal treatment: Racial and ethnic disparities in alcoholism treatment services. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(1):49–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Caetano R. Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(8):1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Galea S, Rudenstine S. Challenges in understanding disparities in drug use and its consequences. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl. 3):iii, 5–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perron BE, Mowbray OP, Glass JE, Delva J, Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Differences in service utilization and barriers among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites with drug use disorders. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4(3) doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: Results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]