Abstract

Background

This investigation examined the mechanisms by which coronary perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT)-derived factors influence vasomotor tone and the PVAT proteome in lean vs. obese swine.

Methods and Results

Coronary arteries from Ossabaw swine were isolated for isometric tension studies. We found that coronary (P=0.03) and mesenteric (P=0.04), but not subcutaneous adipose tissue, augmented coronary contractions to KCl (20 mM). Inhibition of CaV1.2 channels with nifedipine (0.1 μM) or diltiazem (10 μM) abolished this effect. Coronary PVAT increased baseline tension and potentiated constriction of isolated arteries to PGF2α in proportion to the amount of PVAT present (0.1–1.0 g). These effects were elevated in tissues obtained from obese swine and were observed in intact and endothelium denuded arteries. Coronary PVAT also diminished H2O2-mediated vasodilation in lean, and to a lesser extent in obese arteries. These effects were associated with alterations in the obese coronary PVAT proteome (detected 186 alterations) and elevated voltage-dependent increases in intracellular [Ca2+] in obese smooth muscle cells. Further studies revealed that a Rho-kinase inhibitor fasudil (1 μM) significantly blunted artery contractions to KCl and PVAT in lean, but not obese swine. Calpastatin (10 μM) also augmented contractions to levels similar to that observed in the presence of PVAT.

Conclusions

Vascular effects of PVAT vary according to anatomic location and are influenced by an obese phenotype. Augmented contractile effects of obese coronary PVAT are related to alterations in the PVAT proteome (e.g. calpastatin), Rho-dependent signaling, and the functional contribution of K+ and CaV1.2 channels to smooth muscle tone.

Keywords: smooth muscle, perivascular adipose, coronary disease, obesity, vasoconstriction

INTRODUCTION

Adipose tissue normally surrounds the major conduit coronary arteries on the surface of the heart. The volume of this perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) expands with obesity1, 2 and has been shown to be a strong, independent predictor of coronary atherosclerosis3. Recent studies implicate PVAT as a ready source of vasoactive factors and inflammatory mediators capable of influencing vasomotor function4. Thus, there is growing evidence that adipocyte-derived factors originating outside of the coronary vasculature are capable of affecting vascular homeostasis5–8. This “outside-to-inside” signaling paradigm is supported by several studies indicating that adventitial factors significantly diminish vascular function7 and influence compositional changes in the inner intimal layer9. Thus, local adipose in the heart could be an important regulator of vascular function and disease progression.

Although numerous studies indicate that PVAT releases relaxing factors which attenuate vasoconstriction to a variety of compounds in peripheral vascular beds10, 11, data on the vascular effects of coronary PVAT are equivocal12–15. In particular, experiments in isolated arteries from lean and hypercholesterolemic swine show little/no effect of coronary PVAT on coronary artery contractions or endothelial-dependent vasodilation13. In contrast, PVAT has been found to impair coronary endothelial function in vitro and in vivo in normal-lean dogs14 and significantly exacerbate underlying endothelial dysfunction in obese swine with the metabolic syndrome (MetS)15. These differences in the paracrine effects of coronary vs. other peripheral PVAT depots are likely related to alterations in adipocytokine expression profile between these beds, as well as the consequences of underlying co-morbidities (e.g. obesity) on these profiles16, 17. While recent studies have begun to uncover pathophysiologic changes that occur in PVAT12, 18, the functional phenotypic effects of obesity on coronary PVAT remain poorly understood.

Accordingly, the goal of this investigation was to dissect the mechanisms by which lean and obese PVAT-derived factors influence vasomotor tone and the coronary PVAT proteome. In particular, we tested the hypothesis that obesity markedly alters the functional expression and vascular effects of coronary PVAT in favor of an augmented vasoconstriction. This hypothesis is supported by earlier data demonstrating that obesity increases the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in isolated smooth muscle cells19, 20 and enhances coronary vasoconstriction to neurohumoral modulators both in vitro and in vivo 21–23. Our findings provide novel evidence regarding the potential role for specific coronary PVAT-derived proteins in coronary vascular dysfunction in the setting of obesity.

METHODS

Ossabaw swine model of obesity

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Lean animals (n = 37) were fed ~2200kcal/day standard chow containing 18% kcal from protein, 71% kcal from complex carbohydrates, and 11% kcal from fat. Obese animals (n = 23) were fed an atherogenic diet containing ≥ 8000 kcal/day, 16% kcal from protein, 41% kcal from complex carbohydrates, 19% kcal from fructose, 43% kcal from fat and supplemented with 2.0% cholesterol and 0.7% sodium cholate by weight (5B4L and KT-324, Purina Test Diet, Richmond, IN). Swine of either sex were fed their respective diets for 6–12 months. Lean male Sprague-Dawley Rats (n = 4, 250–300 g) were also utilized for aortic ring experiments.

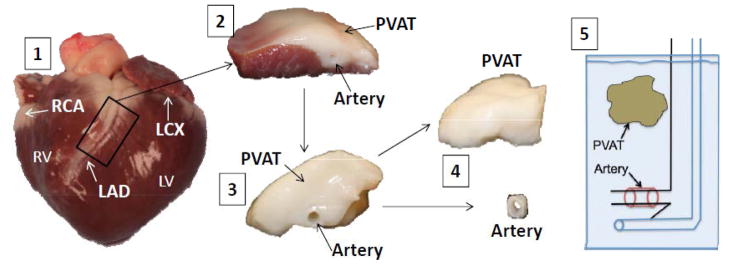

Functional assessment of isolated coronary rings

Studies on isolated coronary arteries in the presence and absence of coronary PVAT were performed as previously described15 (see Supplement for detailed methodology and protocols). Briefly, coronary arteries from lean and obese swine were dissected and cleaned of adventitial adipose tissue. Adjacent adipose was cleaned of myocardium and stored in ice-cold Ca2+-free Krebs for later use. Arteries were cut into 3 mm rings and mounted in organ baths for isometric tension studies (Figure 1). Once an optimal level of baseline passive tension was obtained (~4 g), arteries were stimulated with either KCl (10–60 mM) or prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α; 10 μM) to obtain control responses in the absence of PVAT. Known quantities of adipose tissue (0.1–1.0 g) were then added to the organ baths and arteries allowed to incubate for 30 min at 37°C. Arteries were then stimulated again with KCl or PGF2α in the presence of PVAT; i.e. paired studies in the absence and presence of PVAT were performed on the same arteries. Time control studies were also performed in response to these agonists following a 30 min incubation period in the absence of PVAT. Identical studies were also performed in rat aortic rings exposed to rat peri-aortic adipose tissue. Equimolar replacement experiments of K+ for Na+ revealed no differences in the amount of tension developed in isolated coronary arteries when compared to paired responses without equimolar substitution (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative picture illustrating isolation of coronary artery PVAT and isometric tension methodology. RV (right ventricle), LV (left ventricle), RCA (right coronary artery), LCX (left circumflex artery), LAD (left anterior descending artery), PVAT (perivascular adipose tissue). 1) Lean and obese hearts were excised upon sacrifice and perfused with Ca2+-free Krebs to remove excess blood; 2) Arteries and PVAT were grossly isolated from the heart; 3) the myocardium was removed; 4) arteries were further isolated and surrounding PVAT dissected away; 5) 3 mm lean and obese arteries were mounted in organ baths at 37°C.

For bioassay experiments, organ baths were drained after control responses and filled with a filtered (0.2 μm) PVAT conditioned supernatant (0.3 g PVAT in 5 ml of Ca2+ containing Krebs buffer). Arteries were incubated with this supernatant for 30 min prior to repeat administration of 20 mM KCl. Experiments to examine the effects of lean and obese PVAT on coronary vasodilatory responses to H2O2 (1 μM – 1 mM) were performed in isolated lean and obese coronary arteries pre-constricted with either KCl (60 mM) or U46619 (1 μM).

Additional “crossover” experiments were performed in lean coronary arteries incubated for 30 min with coronary PVAT obtained from a lean or obese animal sacrificed on the same day. Effects of coronary PVAT-derived factors on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) were examined by inhibition of SERCA with cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM). Whole-cell intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2, AM and the InCa++ Ca2+ Imaging System24 (see Supplement). The role of Rho kinase in PVAT-mediated coronary vasoconstriction was assessed by incubation of lean and obese arteries with the Rho kinase inhibitor fasudil (1 μM).25 Further studies to examine the effects of calpastatin (1–10 μM) or negative (scrambled) calpastatin peptide (10μM) on coronary artery contractions were also performed.

Proteomic analyses

Upon sacrifice, hearts were extracted and the aorta immediately perfused with 1L ice-cold Ca2+-free Krebs to remove the blood proteins. Coronary PVAT was excised from the heart, rinsed with PBS and minced. PVAT (0.3 g) was incubated in 5 mL Ca2+-free Krebs in a 37°C shaking bath and filtered (0.2 μm) before flash freezing the filtrate in liquid N2. Filtered protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad)26. Samples were reduced and alkylated by triethylphosphine and iodoethanol and subjected to trypsin digestion as described27. Digested samples were analyzed using a Thermo-Finnigan linear ion-trap (LTQ) mass spectrometer coupled with a Surveyor autosampler and MS HPLC system (Thermo-Finnigan). Tryptic peptides were analyzed using a C18 RP column as described27. Data were searched against the most recent UniProt protein sequence database of Eutheria using SEQUEST (v. 28 rev. 12) algorithms in Bioworks (v3.3). General parameters were set to: peptide tolerance 2.0 amu, fragment ion tolerance 1.0 amu, enzyme limits set as “fully enzymatic - cleaves at both ends”, and missed cleavage sites set at 2. Searched peptides and proteins were validated by PeptideProphet28 and ProteinProphet29 in the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (TPP, v3.3.0) (http://tools.proteomecenter.org/software.php). Only proteins with probability ≥ 0.90 and peptides with probability ≥ 0.80 were reported. Protein quantification by label-free quantitative mass spectrometry (LFQMS) was performed using IdentiQuantXLTM software as described30. Protein quantities are based on the sum of all corresponding peptide ion intensities derived from the area-under-the-curve of their extracted ion chromatograms and thus have no units.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Phenotypic data for lean vs. obese swine were assessed by Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test. For isometric tension studies, two-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of the PVAT (Factor A) relative to doses of specific agonists (Factor B). When statistical differences were found with ANOVA (P < 0.05) a Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed. SigmaPlot version 11.0 was used for graphics and statistical analyses (Systat Software Inc.).

Comparison of individual protein quantity via experimental group means generated by LFQMS was performed within the IdentiQuantXL platform using a student’s t-test. All P-values were transformed into q-values to estimate the False Discovery Rate (FDR)31. To interpret the biological relevance of the differential protein expression data, protein lists and their corresponding expression values (fold change) were uploaded onto the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software server (http://www.ingenuity.com) and analyzed using the Core Analysis module to rank the proteins into top molecular and cellular functions and canonical pathways.

RESULTS

Vascular effect of PVAT from different anatomical depots

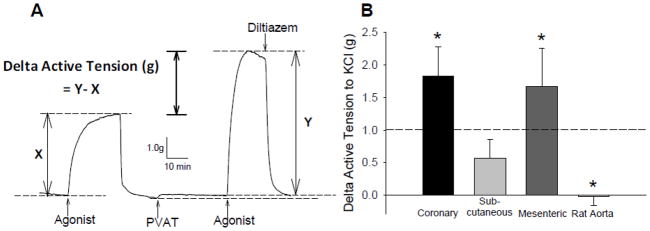

The representative tracing in Figure 2A outlines the protocol utilized to examine the vascular effects of coronary, subcutaneous and mesenteric PVAT on tone of isolated coronary arteries from lean swine at baseline and in response to 20 mM KCl. In these paired studies, arteries were contracted with KCl before and after 30 min incubation with 0.3 g of PVAT. Data are expressed as delta active tension, which reflects the difference in tension generated in response to KCl, independent of modest increases in baseline tension that tended to occur during the incubation period (average 0.67 ± 0.16 g; P = 0.06). Thus, changes in delta active tension do not take into account changes in baseline tension. In lean coronary arteries, coronary (P = 0.03) and mesenteric (P = 0.04) PVAT significantly increased the tension generated in response to 20 mM KCl (Figure 2B) relative to time control KCl responses in the absence of PVAT (dashed line). These coronary contractions were completely reversed by inhibition of CaV1.2 channels with 10 μM diltiazem (Figure 2A) or 0.1 μM nifedipine. In contrast, incubation with subcutaneous PVAT did not significantly alter coronary artery contractions to KCl (P = 0.67), with values similar to time controls. Further studies in tissues obtained from Sprague-Dawley rats also revealed no effect of rat aortic PVAT on KCl-induced contractions of thoracic aortic rings (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Representative tracing of paired experiments to assess the vascular effects of PVAT from different anatomical depots. A, Representative wire myograph tracing of tension generated by arteries before (x) and after (y) the addition of PVAT to the organ bath. Upward deflections indicate an increase in tension (constriction). The difference in tension generated by each artery before (x) and after (y) PVAT is expressed as Delta Active Tension (g) and is independent of changes in baseline with PVAT. B, Delta active tension (g) of coronary arteries before and after exposure to coronary PVAT, subcutaneous adipose or mesenteric PVAT (0.3 g each). *P < 0.05 vs. average of paired time controls (represented by dashed line; 1.01 ± 0.21 g).

Additional bioassay experiments which involved the transfer of swine coronary PVAT-conditioned media, instead of the addition of whole 0.3 g pieces of PVAT to the tissue bath, also revealed similar increases in tension development in response to KCl administration relative to paired, non-PVAT treated control responses (P = 0.04; data not shown).

Vascular effects of lean vs. obese coronary PVAT

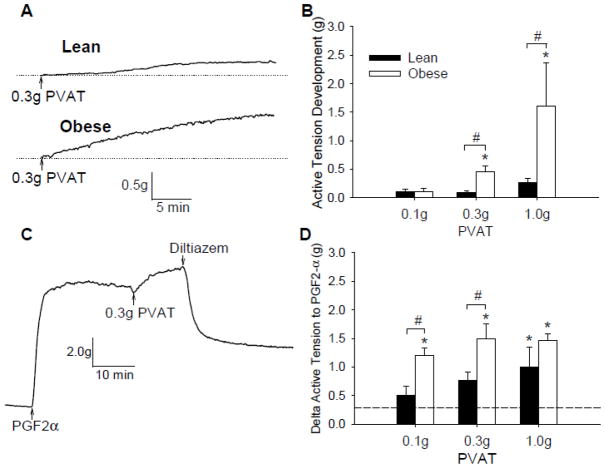

Phenotypic data on a subset of lean (n = 6) and obese (n = 10) swine utilized for this investigation are outlined in Table 1. Swine listed were fed high-calorie atherogenic diet for ~6 months, which resulted in significant increases in body weight, heart weight, total cholesterol and the LDL/HDL ratio. To initially examine the effects of lean vs. obese coronary PVAT on baseline tension, coronary artery rings were incubated with known quantities of PVAT (0.1–1.0g) for 30 min. For these studies, PVAT from lean and obese swine were added to tissue baths containing coronary arteries obtained from the same lean or obese heart; i.e. lean PVAT paired with lean coronary artery and obese PVAT paired with obese coronary artery. We found that coronary PVAT increased baseline tension of both lean and obese coronary arteries (Figure 3A) and noted that this effect was dependent on the amount of PVAT added to the bath (Figure 3B). Importantly, the increase in basal tone was markedly augmented in tissues obtained from obese vs. lean swine (P < 0.001). Administration of coronary PVAT also increased tension of isolated coronary arteries pre-contracted with 10 μM PGF2α(Figure 3C). This increase in tension generated with PVAT was also related to the amount of PVAT present in the bath (P < 0.001) and was significantly augmented in obese vs. lean swine (P < 0.001) (Figure 3D). Coronary contractions to PGF2α + PVAT were only partially reversed by the administration of 10 μM diltiazem (82 ± 7%, Figure 3C), but were completely reversed by 1.0 μM nifedipine (99 ± 0.4%).

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of lean and obese Ossabaw swine. Values are mean ± SE for 12-month old lean (n = 6) and obese (n = 10) swine.

| Lean | Obese | |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (kg) | 52 ± 3 | 82 ± 5* |

| Heart wt. (g) | 183 ± 13 | 278 ± 14* |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 75 ± 2 | 86 ± 5 |

| Insulin (μU/ml) | 21 ± 5 | 27 ± 7 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 88 ± 5 | 567 ± 60* |

| LDL/HDL ratio | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 12 ± 4* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 43 ± 5 | 98 ± 25 |

P < 0.05 Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, lean vs. obese swine.

Figure 3.

Effect of PVAT on baseline tension and response to PGF2α. A, Representative tracings of a lean and obese artery after addition of 0.3 g PVAT for 30 min. B, Addition of coronary PVAT (0.1–1.0g) to the organ bath increased tension in both lean and obese arteries and was dependent on the amount of coronary PVAT added to the bath. C, Representative tracing of a lean artery contracted with PGF2α to plateau, incubation with PVAT and treatment with diltiazem (10 μM). D, Delta active tension of arteries stimulated with PGF2α before and after the addition of coronary PVAT (0.1–1.0 g). *P < 0.05 vs. average of paired time controls (represented by dashed line; 0.29 ± 0.08 g). #P < 0.05 lean vs. obese, same amount of PVAT.

Cumulative responses of endothelium intact and denuded coronary arteries to increasing concentrations of KCl (10 – 60 mM) before and during incubation with coronary PVAT are shown in Figure 4. Addition of 0.3 g of PVAT increased active tension generated by endothelium intact coronary arteries in both lean (P = 0.005, Figure 4A) and obese swine (P = 0.009, Figure 4B). Similar responses in the presence of PVAT were also observed in endothelium denuded coronary arteries from lean (Figure 4C) and obese swine (Figure 4D) (denudation confirmed by < 30% relaxation to 1 μM bradykinin). Further studies also revealed that H2O2-mediated vasodilation was markedly attenuated by the presence of coronary PVAT (Figure 5A) and that this inhibitory effect was much more prominent in tissues obtained from lean (Figure 5B) vs. obese (Figure 5C) swine. Importantly, H2O2-induced dilation was completely abolished by pre-contracting lean and obese coronary artery rings with 60 mM KCl (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

KCl dose-response curves in intact and denuded coronary arteries in the presence and absence of PVAT. Cumulative dose-response data of lean (A) and obese (B) arteries to KCl (10–60 mM) before and after coronary PVAT incubation (30 min). Arteries were incubated with coronary PVAT from the same animal on the same day. Cumulative dose-response data from denuded lean (C) and obese (D) vessels before and after PVAT incubation. *P < 0.05 vs. no PVAT-control at same KCl concentration.

Figure 5.

Effect of PVAT on coronary vasodilation to H2O2. A, Representative tracings of H2O2-induced relaxations of lean control arteries pre-constricted with 1 μM U46619 in the absence and presence of PVAT. Average percent relaxation of lean (B) and obese (C) control and PVAT-treated arteries to H2O2 after pre-constriction with either U46619 (1 μM) or KCl (60 mM). *P < 0.05 vs. control at same H2O2 concentration.

To evaluate the vasoactive properties of lean vs. obese coronary PVAT independent of differences in coronary artery responsiveness, we performed “crossover” experiments in which KCl-induced contractions of coronary arteries from lean-control swine were assessed before and after incubation with PVAT from either lean or obese swine (Figure 6A). For these studies, tissues were obtained from lean and obese swine sacrificed on the same day. We found that lean and obese coronary PVAT augmented contractions of lean coronary arteries to 20 mM KCl to a similar degree (Figure 6B). Further studies also showed that increases in KCl-induced coronary artery contractions to 20 mM KCl in the presence of PVAT were not significantly altered by inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase with cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM, Figure 6C). However, consistent with earlier studies32, fura-2 imaging experiments revealed that increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in response to 80mM KCl were significantly elevated in isolated coronary artery smooth muscle cells not exposed to PVAT from obese vs. lean swine (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Vascular effects of lean vs. obese coronary PVAT. A, Representative tracings of lean arteries treated with 20 mM KCl, exposed to either lean or obese PVAT. B, Delta active tension (g) to 20 mM KCl of lean arteries exposed to time control, lean or obese PVAT. *P < 0.05 vs. control. C, Delta active tension (g) to 20 mM KCl after exposure to SERCA inhibition with CPA (10 μM) P < 0.05 vs. control. D, F360/F380 ratio of fura-2 experiments after stimulation of isolated lean (n = 4) and obese (n = 5) coronary vascular smooth muscle with 80 mM KCl. *P < 0.05 obese vs. lean.

Obesity markedly alters the protein expression profile of coronary PVAT

To examine whether differences in vascular responses to coronary PVAT are associated with changes in the expression profile of PVAT, a global proteomic assessment was performed on supernatants obtained from lean and obese coronary PVAT. Data revealed substantial alterations in the proteome in the setting of obesity. Overall, we detected alterations in 186 proteins (P ≤ 0.05) in obese vs. lean PVAT (complete listing of 1,472 quantified non-redundant proteins provided in Supplemental Table 1). A listing of the top up-regulated and down-regulated proteins is provided in Table 2. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software revealed several proteins involved in cellular growth and proliferation (51 molecules) and cellular movement (39 molecules). In particular, increases in RhoA (2.9-fold) and calpastatin (1.6-fold) are of interest as these pathways are directly linked to smooth muscle contraction, Ca2+ sensitization, and both are implicated in the progression of hypertension33, 34.

Table 2.

Secreted protein expression profile of coronary PVAT in obese versus lean swine. Values for fold change in expression of obese (n = 5) vs. lean (n = 5) coronary PVAT supernatants.

| Up-Regulated Proteins | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Protein Name | Fold Change | P-value |

| RHOA | Transforming protein RhoA | 2.9 | 0.04 |

| LAMC1 | Laminin, gamma 1 | 1.7 | 0.004 |

| CS | Citrate synthase | 1.7 | 0.03 |

| HSPA2 | Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 | 1.7 | 0.05 |

| HSPD1 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | 1.6 | 0.005 |

| CAST | Calpastatin | 1.6 | 0.006 |

| ALDH7A1 | Alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 1.6 | 0.04 |

| PROSC | Proline synthase co-transcribed bacterial homolog protein | 1.6 | 0.05 |

| PGM3 | Phosphoacetylglucosamine mutase | 1.5 | 0.0002 |

| CSTB | Cystatin-B | 1.5 | 0.0006 |

| Down-Regulated Proteins | |||

| Gene Name | Protein Name | Fold Change | P-value |

| DDAH2 | Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (Fragment) | 5.5 | 0.02 |

| VBP1 | Prefoldin subunit 3 | 3.8 | 0.03 |

| CAPG | Macrophage-capping protein | 3.1 | 0.02 |

| PSMA3 | Isoform 2 of Proteasome subunit alpha type-3 | 2.7 | 0.02 |

| HNRNPAB | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | 2.7 | 0.003 |

| ZNF439 | Zinc finger protein 439 | 2.6 | 0.03 |

| F9 | Coagulation Factor IX | 2.6 | 0.002 |

| ME1 | Malic Enzyme | 2.5 | 0.0009 |

| PGK | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 2.4 | 0.02 |

| BLMH | Bleomycin hydrolase | 2.4 | 0.006 |

To examine whether Rho kinase signaling participated in the augmented effects of coronary PVAT in coronary arteries, we performed studies on isolated arteries in the presence of the Rho kinase inhibitor fasudil (1 μM). We found that fasudil alone dramatically decreased maximal active tension development in response to KCl in lean coronary arteries (Figure 7A vs. Figure 4A, P < 0.001) and diminished the effect of PVAT on KCl contractions (Figure 7C). This effect of fasudil was less apparent in obese arteries where maximal contractions to KCl were similar to that of untreated-controls (Figure 7B vs. Figure 4B, P = 0.108). Despite blunting lean coronary KCl contractions, in the presence of fasudil, PVAT still elevated contractions relative to control in both lean and obese arteries (P = 0.003 and P = 0.037, respectively).

Figure 7. Effects of Rho kinase signaling and calpastatin on coronary artery contractions to KCl.

Lean (A) and obese (B) arteries were incubated with 1 μM fasudil for 10 min prior to dose-responses to KCl (10–60 mM) in the absence and presence of coronary PVAT. *P < 0.05 vs. no PVAT-control at same KCl concentration. C, Delta active tension (g) in response to 20 mM KCl in lean and obese PVAT control and PVAT + fasudil-treated arteries *P < 0.05 vs. respective PVAT control. D, Delta active tension (g) to 20 mM KCl after incubation with increasing concentrations of calpastatin (1–10 μM) or scrambled calpastatin peptide (10 μM Neg Cnt) for 30 min. *P < 0.05 relative to time control.

Additional proof-of-principle studies were performed to investigate the effects of calpastatin on coronary artery contractions. In these experiments, lean coronary arteries were incubated with increasing concentrations of calpastatin peptide for 30 min without PVAT (1 – 10 μM, Figure 7D). We found that calpastatin dose-dependently increased tension development of lean coronary arteries to 20 mM KCl (P = 0.008) and that 10 μM calpastatin augmented contractions to a similar extent as PVAT itself (1.82 ± 0.45 vs. 1.49 ± 0.19). Negative control experiments revealed no effect of a scrambled calpastatin peptide (10 μM) on coronary artery contractions to 20 mM KCl (Figure 7D).

DISCUSSION

The present investigation was designed to elucidate the mechanisms by which lean and obese PVAT-derived factors influence vasomotor tone and the coronary PVAT proteome. The studies were designed to test the hypothesis that obesity markedly alters the functional expression and vascular effects of coronary PVAT in favor of an augmented contractile phenotype. The major new findings of this study include: 1) vascular effects of PVAT vary according to anatomical location as coronary and mesenteric, but not subcutaneous adipose tissue augmented coronary artery contractions to KCl; 2) factors derived from coronary PVAT increase baseline tension and potentiate constriction of isolated coronary arteries to PGF2α relative to the amount of adipose tissue present; 3) vascular effects of coronary PVAT are markedly elevated in the setting of obesity and occur independent of effects on, or alterations in coronary endothelial function; 4) augmented effects of obese coronary PVAT are associated with substantial alterations in the PVAT proteome and underlying increases in vascular smooth muscle Ca2+ handling via CaV1.2 channels, H2O2-sensitive K+ channels or upstream mediators that converge on these channels; 5) factors converging on Rho-kinase are largely responsible for the increase in coronary artery contractions to PVAT in lean, but not obese swine. These findings provide the first evidence that factors released from coronary PVAT initiate/potentiate coronary vasoconstriction and that this effect is augmented in the setting of obesity.

Differential effects of coronary PVAT in lean vs. obese swine

Currently, data on the vascular effects of coronary PVAT are rather limited and conflicting, as PVAT has been shown to either decrease endothelial-dependent dilation in lean-healthy dogs35 or to have limited/no effect on endothelial function in lean15, 36 or hypercholesteromic13, 36 swine. In contrast, findings from Payne et al. indicate that coronary PVAT significantly exacerbates underlying endothelial dysfunction in the setting of obesity and the MetS15. Additional findings suggest that coronary PVAT has relatively modest “anti-contractile” effects in lean and hypercholesterolemic swine13, which differs from numerous other studies which found evidence of adipose derived relaxing factors (ADRFs) in PVAT surrounding vessels such as the aorta, mesenteric arteries, and internal thoracic arteries (see 6 for review). Taken together, these earlier studies suggest that the expression and effects of PVAT-derived factors may differ substantially between vascular beds and can be influenced by underlying disease states.

Our present data support differential effects of PVAT from different anatomical depots in that coronary and mesenteric, but not subcutaneous adipose tissue augmented coronary artery contractions in response to smooth muscle depolarization with 20 mM KCl (Figure 2B). Consistent with previous studies37, this effect was not observed in aortic tissues obtained from rats. Further studies supporting the presence of coronary adipose-derived constricting factors showed that the addition of coronary PVAT to PGF2α constricted arteries actually increased coronary vasomotor tone (Figure 3C), as opposed to decreasing tension, which would be expected if ADRFs predominated in coronary PVAT. Bioassay experiments involving the transfer of PVAT-conditioned media to isolated coronary arteries support the release of transferable (paracrine) constricting factors from coronary PVAT (P = 0.04). Importantly, these effects were dependent on the amount of PVAT added to the baths (Figure 3) and were significantly greater than responses observed in parallel time-control studies. Our findings are consistent with studies that found PVAT attenuated vasodilator influences in obese mice38 and potentiated vasoconstriction to electrical field stimulation in rat mesenteric arteries39. A novel finding of this investigation is that the effects of coronary PVAT on baseline and agonist-mediated contractions were markedly elevated in tissue obtained from obese vs. lean swine (Figure 3B and 3D). To address whether this augmentation was related to inherent mechanistic differences in vascular smooth muscle, crossover studies were performed in which coronary PVAT from either lean or obese swine was added to clean, lean coronary arteries. We found that PVAT from lean and obese swine increased coronary contractions to 20 mM KCl to a similar extent (Figure 6B). Additional experiments in clean, obese arteries yielded similar results (data not shown). Consistent with earlier data from our laboratory and others which indicate that obesity augments CaV1.2 current and vasoconstriction19, 40,41, the present fura-2 Ca2+ imaging studies support that voltage-dependent increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration to KCl are significantly greater in isolated smooth muscle cells from obese vs. lean swine (Figure 6D). Based on these findings we propose that the augmented contractile effects of obese coronary PVAT are related to inherent differences in smooth muscle responsiveness between obese and lean coronary arteries, and that this effect is mediated by elevated activity/ expression of CaV1.2 channels and/or alterations in the role of K+ channels in obese arteries41. Importantly, inhibitory effects of PVAT derived-factors on K+ channels (Figure 5) would also serve to activate CaV1.2 channels and augment coronary artery contractions42. However, the exact K+ channel subtypes on smooth muscle and/or the endothelium affected by coronary PVAT warrants further investigation.

We postulate that these effects of PVAT derived factors occur independent of influences on coronary endothelium or decreased Ca2+ buffering by the sarcoplasmic reticulum as endothelial denudation (Figure 4C and 4D) or inhibition of the SERCA pump with CPA (Figure 6C) had little/no effect on the contractile effects of PVAT. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed effects of coronary PVAT are mediated by factors released from endothelial cells within the PVAT vasculature and/or by factors released from other cell types within the PVAT.

Effects of obesity on coronary PVAT proteome and mechanisms of coronary contraction

Although recent evidence indicates that hypercholesterolemia, obesity and diabetes alter phenotypic expression patterns of specific adipokines in coronary PVAT at the protein and mRNA level12, 36, 43, no study has performed global proteomic screening of the coronary PVAT proteome in lean vs. obese subjects. Data from our LC-MS/MS revealed significant dysregulation in the abundance of numerous proteins in obese PVAT supernatant, many of which were not previously reported12. In general, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis indicated that a significant number of altered proteins corresponded with pathways associated with cellular growth-proliferation and movement. In particular, it was intriguing that expression of RhoA was significantly elevated in samples obtained from obese vs. lean coronary PVAT (Table 2), which suggests that the enhanced effects of obese coronary PVAT could be mediated via increases in Rho-kinase-mediated constriction. Interestingly, we documented that inhibition of Rho-kinase with fasudil markedly reduced the maximal contractions to KCl in lean arteries (Figure 4A versus 7A), but had little effect on maximal KCl contractions in obese arteries (Figure 4B versus 7B). In addition, fasudil significantly diminished PVAT-mediated increases in coronary artery contractions to 20 mM KCl in lean but not obese arteries (Figure 7C). These data indicate that PVAT-derived factors increase coronary artery contractions in lean swine via a Rho-kinase dependent mechanism, whereas increases in contraction in obese swine occur via Rho-independent pathways; i.e. alteration in the contribution of K+ channels (Figure 5) or augmented function of CaV1.2 channels (Figure 6D).

Additional proof of principle studies were performed based on our global proteomics data which detected significant up-regulation of calpastatin fragments in PVAT supernatant of obese vs. lean swine. This protein, encoded by the CAST gene, was recently shown to be a partial agonist for the intracellular domain of CaV1.2 channels in smooth muscle44. Our experiments documented, for the first time, that calpastatin dose-dependently augments coronary artery contractions, at levels similar to that observed in the presence coronary PVAT (Figure 7D). Although these data suggest that calpastatin is a coronary adipose-derived constricting factor, further studies are needed to more directly address the vascular effects of calpastatin.

Limitations of the study

It is important to recognize that these studies were conducted using coronary samples obtained from lean and obese swine hearts, thus it is presently unclear to what extent these findings translate to the human clinical setting. However, our data provide direct evidence of differential effects of PVAT from different anatomic depots in the same species as well as the influence of underlying phenotype (obesity) that should be further explored. Coronary artery tension in this study was measured after relatively short term exposure to PVAT in vitro (30 min). Thus, whether such effects of PVAT would manifest in vivo has yet to be established. LFQMS analysis revealed only the most abundant proteins present in the PVAT supernatants and those identifiable/quantifiable by trypic digestion. This approach may not detect potentially relevant proteins present in low concentration (e.g. specific adipokines such as leptin (18kDa) or resistin (11 kDa) or those that were either not effectively proteolyzed or are so small as to yield a few detectable peptides). We acknowledge that the focus on the coronary PVAT proteome eliminates examination of bioactive lipids or other macromolecules that may contribute to the effects of PVAT. However, while we cannot rule out this possibility, our initial studies have demonstrated no effect of lysophosphatidic acid on baseline coronary artery tension or KCl-induced contractions. Furthermore, we submit that it is unlikely that vasoactive factors responsible for the effects of coronary PVAT in this investigation are hydrophobic lipids, as these molecules are insoluble in the Krebs buffer utilized in the present experiments. This point is supported by the recent study of Lee et al. which required the use of a PVAT superfusion bioassay cascade system in order to discern vascular effects of PVAT-derived palmitic acid methyl ester45. Clearly, further investigation regarding the identity of the coronary PVAT-derived factors, the specific cell types involved and the influence obesity has on these cells and factors is warranted.

Conclusions and implications

Data from this investigation provide novel evidence that coronary PVAT is capable of releasing factors that initiate/potentiate contraction of coronary arteries, independent of effects on coronary endothelium. Importantly, the vascular influence of PVAT is specific to anatomic location and is augmented in the setting of obesity. We propose this augmented effect of PVAT is related to alterations in Rho-dependent signaling, increased functional expression of CaV1.2 channels and/or diminished/altered activity of K+ channels in obese coronary arteries. In addition, marked alterations in the expression profile of the coronary PVAT proteome in obese swine uncovers new potential therapeutic target proteins (e.g. calpastatin) and signaling pathways that may not only contribute to the regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone, but to the initiation of smooth muscle differentiation and proliferation observed in obesity-induced cardiovascular disease12, 43, 46, 47.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Adipose tissue normally surrounds the major conduit coronary arteries on the surface of the heart. The volume of this perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) expands with obesity and has been shown to be a strong, independent predictor of coronary atherosclerosis. Recent studies implicate PVAT as a ready source of vasoactive factors and inflammatory mediators capable of influencing vasomotor function, however the vascular effects of coronary PVAT have not been clearly defined. Data from this investigation provide novel evidence that coronary PVAT is capable of releasing factors that initiate/potentiate contraction of coronary arteries, independent of effects on endothelium. Importantly, the vascular influence of PVAT is specific to anatomic location and is augmented in the setting of obesity. Our findings support that this augmented effect of PVAT is related to alterations in Rho-dependent signaling, increased functional expression of CaV1.2 channels and/or diminished/altered activity of K+ channels in obese coronary arteries. Marked alterations in the expression profile of the coronary PVAT proteome in the setting of obesity uncovers new potential therapeutic target proteins (e.g. calpastatin) and signaling pathways that may not only contribute to the regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone, but to the initiation of smooth muscle differentiation and proliferation observed in obesity-induced cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Heather Ringham and Meixian Fang for their technical contributions to the proteomic analysis.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH grants HL092245 (JDT), HL062552 (MS). Meredith Kohr Owen was supported by NIH T32DK064466. This project was supported in part by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute Grant number TR000006 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Mahabadi AA, Reinsch N, Lehmann N, Altenbernd J, Kalsch H, Seibel RM, Erbel R, Mohlenkamp S. Association of pericoronary fat volume with atherosclerotic plaque burden in the underlying coronary artery: a segment analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greif M, Becker A, von ZF, Lebherz C, Lehrke M, Broedl UC, Tittus J, Parhofer K, Becker C, Reiser M, Knez A, Leber AW. Pericardial adipose tissue determined by dual source CT is a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:781–6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boydens C, Maenhaut N, Pauwels B, Decaluwe K, Van d V. Adipose tissue as regulator of vascular tone. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:270–8. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesauro M, Cardillo C. Obesity, blood vessels and metabolic syndrome. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;203:279–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gollasch M. Vasodilator signals from perivascular adipose tissue. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:633–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fesus G, Dubrovska G, Gorzelniak K, Kluge R, Huang Y, Luft FC, Gollasch M. Adiponectin is a novel humoral vasodilator. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:719–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomkalns AL, Chatterjee T, Weintraub NL. Turning ACS outside in: linking perivascular adipose tissue to acute coronary syndromes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H734–H735. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00058.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campia U, Tesauro M, Cardillo C. Human obesity and endothelium-dependent responsiveness. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:561–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohn M, Dubrovska G, Lauterbach B, Luft FC, Gollasch M, Sharma AM. Periadventitial fat releases a vascular relaxing factor. FASEB J. 2002;16:1057–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0024com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenstein AS, Khavandi K, Withers SB, Sonoyama K, Clancy O, Jeziorska M, Laing I, Yates AP, Pemberton PW, Malik RA, Heagerty AM. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Circulation. 2009;119:1661–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne GA, Kohr MC, Tune JD. Epicardial perivascular adipose tissue as a therapeutic target in obesity-related coronary artery disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:659–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunker AK, Laughlin MH. Influence of exercise and perivascular adipose tissue on coronary artery vasomotor function in a familial hypercholesterolemic porcine atherosclerosis model. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:490–7. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00999.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne GA, Bohlen HG, Dincer UD, Borbouse L, Tune JD. Periadventitial adipose tissue impairs coronary endothelial function via PKC-beta-dependent phosphorylation of nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H460–H465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00116.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne GA, Borbouse L, Kumar S, Neeb Z, Alloosh M, Sturek M, Tune JD. Epicardial perivascular adipose-derived leptin exacerbates coronary endothelial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome via a protein kinase C-beta pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1711–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu C, Su LY, Lee RM, Gao YJ. Alterations in perivascular adipose tissue structure and function in hypertension. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;656:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houben AJ, Eringa EC, Jonk AM, Serne EH, Smulders YM, Stehouwer CD. Perivascular Fat and the Microcirculation: Relevance to Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6:80–90. doi: 10.1007/s12170-011-0214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Company JM, Booth FW, Laughlin MH, Arce-Esquivel AA, Sacks HS, Bahouth SW, Fain JN. Epicardial fat gene expression after aerobic exercise training in pigs with coronary atherosclerosis: relationship to visceral and subcutaneous fat. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1904–12. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00621.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borbouse L, Dick GM, Asano S, Bender SB, Dincer UD, Payne GA, Neeb ZP, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Tune JD. Impaired function of coronary BK(Ca) channels in metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1629–H1637. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00466.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturek M. Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms of exercise protection against coronary artery disease in metabolic syndrome and diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:573–86. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00373.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C, Knudson JD, Setty S, Araiza A, Dincer UD, Kuo L, Tune JD. Coronary arteriolar vasoconstriction to angiotensin II is augmented in prediabetic metabolic syndrome via activation of AT1 receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2154–H2162. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00987.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dincer UD, Araiza AG, Knudson JD, Molina PE, Tune JD. Sensitization of coronary alpha-adrenoceptor vasoconstriction in the prediabetic metabolic syndrome. Microcirculation. 2006;13:587–95. doi: 10.1080/10739680600885228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knudson JD, Dincer UD, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Dick GM, Tune JD. Mechanisms of coronary dysfunction in obesity and insulin resistance. Microcirculation. 2007;14:317–38. doi: 10.1080/10739680701282887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards JM, Neeb ZP, Alloosh MA, Long X, Bratz IN, Peller CR, Byrd JP, Kumar S, Obukhov AG, Sturek M. Exercise training decreases store-operated Ca2+entry associated with metabolic syndrome and coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:631–40. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rattan S, Patel CA. Selectivity of ROCK inhibitors in the spontaneously tonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G687–G693. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00501.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai X, Bacallao RL, Blazer-Yost BL, Hong D, Mason SB, Witzmann FA. Characterization of the renal cyst fluid proteome in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) patients. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2:1140–52. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–92. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4646–58. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai X, Wang L, Tang H, Witzmann FA. A novel alignment method and multiple filters for exclusion of unqualified peptides to enhance label-free quantification using peptide intensity in LC-MS/MS. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4799–812. doi: 10.1021/pr2005633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storey J. A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borbouse L, Dick GM, Payne GA, Payne BD, Svendsen MC, Neeb ZP, Alloosh M, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Tune JD. Contribution of BK(Ca) channels to local metabolic coronary vasodilation: Effects of metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H966–H973. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00876.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Satoh H, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, Tamakawa H, Yamagami K, Inui J, Maekawa M, Narumiya S. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–4. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letavernier E, Perez J, Bellocq A, Mesnard L, de Castro KA, Haymann JP, Baud L. Targeting the calpain/calpastatin system as a new strategy to prevent cardiovascular remodeling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2008;102:720–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Payne GA, Borbouse L, Bratz IN, Roell WC, Bohlen HG, Dick GM, Tune JD. Endogenous adipose-derived factors diminish coronary endothelial function via inhibition of nitric oxide synthase. Microcirculation. 2008;15:417–26. doi: 10.1080/10739680701858447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reifenberger MS, Turk JR, Newcomer SC, Booth FW, Laughlin MH. Perivascular fat alters reactivity of coronary artery: effects of diet and exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:2125–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318156e9df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubrovska G, Verlohren S, Luft FC, Gollasch M. Mechanisms of ADRF release from rat aortic adventitial adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1107–H1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00656.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marchesi C, Ebrahimian T, Angulo O, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and perivascular adipose oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to vascular dysfunction in a rodent model of metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2009;54:1384–92. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao YJ, Takemori K, Su LY, An WS, Lu C, Sharma AM, Lee RM. Perivascular adipose tissue promotes vasoconstriction: the role of superoxide anion. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:363–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin YC, Huang J, Kan H, Castranova V, Frisbee JC, Yu HG. Defective calcium inactivation causes long QT in obese insulin-resistant rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1013–H1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00837.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berwick ZC, Dick GM, Moberly SP, Kohr MC, Sturek M, Tune JD. Contribution of voltage-dependent K(+) channels to metabolic control of coronary blood flow. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:912–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dick GM, Tune JD. Role of potassium channels in coronary vasodilation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:10–22. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacks HS, Fain JN, Cheema P, Bahouth SW, Garrett E, Wolf RY, Wolford D, Samaha J. Inflammatory genes in epicardial fat contiguous with coronary atherosclerosis in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: changes associated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:730–3. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minobe E, Asmara H, Saud ZA, Kameyama M. Calpastatin domain L is a partial agonist of the calmodulin-binding site for channel activation in Cav1. 2 Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39013–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee YC, Chang HH, Chiang CL, Liu CH, Yeh JI, Chen MF, Chen PY, Kuo JS, Lee TJ. Role of perivascular adipose tissue-derived methyl palmitate in vascular tone regulation and pathogenesis of hypertension. Circulation. 2011;124:1160–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.027375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thalmann S, Meier CA. Local adipose tissue depots as cardiovascular risk factors. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajsheker S, Manka D, Blomkalns AL, Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Weintraub NL. Crosstalk between perivascular adipose tissue and blood vessels. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.