Abstract

Objective

To estimate the global and regional distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants between 2000 and 2007.

Design

Country-specific HIV-1 molecular epidemiology data were combined with estimates of the number of HIV-infected people in each country.

Method

Cross-sectional HIV-1 subtyping data were collected from 65913 samples in 109 countries between 2000 and 2007. The distribution of HIV-1 subtypes in individual countries was weighted according to the number of HIV-infected people in each country to generate estimates of regional and global HIV-1 subtype distribution for the periods 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

Results

Analysis of the global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in the two time periods indicated a broadly stable distribution of HIV-1 subtypes worldwide with a notable increase in the proportion of circulating recombinant forms (CRFs), a decrease in unique recombinant forms (URFs), and an overall increase in recombinants. In 2004–2007, subtype C accounted for nearly half (48%) of all global infections, followed by subtypes A (12%) and B (11%), CRF02_AG (8%), CRF01_AE (5%), subtype G (5%) and D(2%). Subtypes F, H, J and K together cause fewer than 1% of infections worldwide. Other CRFs and URFs are each responsible for 4% of global infections, bringing the combined total of worldwide CRFs to 16% and all recombinants (CRFs plus URFs) to 20%.

Conclusions

The global and regional distributions of individual subtypes and recombinants are broadly stable, although CRFs may play an increasing role in the HIV pandemic. The global diversity of HIV-1 poses a formidable challenge to HIV vaccine development.

Keywords: HIV, subtype, Circulating Recombinant Form (CRF), recombinant, molecular epidemiology, vaccine

Introduction

HIV-1 remains a global health problem of unprecedented dimensions, with an estimated 33.4 million people living with HIV in 2008. The pandemic is dynamic, with 2.7 million new infections and 2 million deaths occurring in 2008 [1].

HIV originated from multiple zoonotic transmissions of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) from non-human primates to humans in West and Central Africa in the early 1900s. HIV-1 group M, the pandemic branch of HIV, originates from SIVcpz in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes [2]. After transmission to humans, while still confined to western-central Africa, HIV-1 group M diversified into genetic subtypes (named A-D, F-H and J-K) in the first half of the 20th century [3]. HIV genetic variability is the result of the high mutation and recombination rates of the reverse transcriptase enzyme, together with high rates of virus replication. Recombinants between subtypes are designated as circulating recombinant forms (CRFs; 48 different CRFs have been described so far [4]) if fully sequenced and found in three or more epidemiologically unlinked individuals, and unique recombinant forms (URFs) if not meeting these criteria [5]. In the second half of the 20th century the global spread of HIV-1 group M took place resulting in the differential global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants [6].

HIV diversity impacts HIV diagnosis and viral load measurements [7, 8] and may affect the response to antiretroviral treatment and the emergence of drug resistance [9, 10]. Subtypes may differ in the rate of disease progression [11–13] and some evidence suggests that subtypes are transmitted at different rates [14, 15].

HIV infection in humans induces humoral and cellular immune responses which control primary viraemia without completely eliminating infection due to the rapid selection of immune-escape mutants [16, 17]. While the induction of neutralising antibodies and effective CTL responses against HIV-1 through vaccination has proven extremely difficult, an even greater challenge is posed by the extreme genetic diversity of the virus and its continuing evolution [18].

Genetic variation within a subtype is in the order of 8–17%, whereas variation between subtypes is usually between 17–35 %, depending on the subtypes and genome regions examined [19]. This degree of diversity is likely to limit the intra- and inter-subtype cross-reactivity of immune responses [20]. To increase the likelihood of vaccine-induced immune responses cross-reacting with circulating strains, immunogens should match as closely as possible viral sequences circulating in the target population [21]. Candidate HIV vaccines tested in efficacy trials to date have been based on primary sequences of subtype B and CRF01_AE [22–24]. Recent encouraging results of a phase III HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial in Thailand emphasise the importance of further studies on global and regional HIV diversity to inform rational vaccine design and development [24].

Data on the global distribution of HIV subtypes is limited. HIV sequences deposited in the Los Alamos sequence database are not representative for the distributions in the countries of origin [4]. Some studies have relied on pooling published data from a wide range of years, an approach which is hampered by publication bias and a lack of information on trends [25]. Here we present an analysis of the global and regional distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants for the periods 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 using a combination of cross-sectional country-specific HIV-1 molecular epidemiology data, derived from published and unpublished sources, and estimates of the number of HIV-infected people in each country.

Methods

Country-specific cross-sectional subtype distribution data

Data on the distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in individual countries were obtained from researchers in the field and from a comprehensive literature review. Research laboratories across the globe specialising in subtyping of HIV-1 samples were solicited for cross-sectional HIV-1 subtyping data of samples collected between 2000 and 2007. The Medline literature database was searched for HIV-1 subtyping data for each country using the terms “HIV”, “subtype” and the relevant country names. All potentially relevant articles in English were retrieved and HIV-1 subtyping data from samples collected between 2000–2007 were included in our study. Data submitted to us and derived from the literature were combined to determine the overall proportions of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in each country. In addition to information on HIV-1 subtypes, the data sets included country (and region/city) of sample origin, sampling year, transmission route/risk group, detection method, and the genome segment(s) analysed. Overall, subtyping data of 41.8% of the samples originated from previously unpublished data by members of the WHO-UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterisation, 35.6% were derived from the published literature, and 22.6% were both submitted to us and published.

Global HIV-1 epidemiology and regional country groupings

Country-specific HIV-1 epidemiology data were obtained from the UNAIDS/WHO estimates of the burden of HIV-1 in the years 2000 through 2007 [26]. For each country the average number of HIV-1 infections in the periods of 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 was determined and used in further analysis.

Countries were grouped in geographical regions according to the UNAIDS classification [26], with some modifications. Sub-Saharan Africa was divided into five separate regions (West, East, Central and Southern Africa, and Ethiopia), because the region has the largest number of HIV-1 infections and a high level of regional HIV-1 subtype diversity. India and Ethiopia were analysed separately as most infections were caused by a single subtype (C), which would have skewed the distribution in their respective regions, where other subtypes predominate. These modifications resulted in the final grouping of all countries into 15 regions, as specified in the legend of Table 2.

Table 2. Distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants globally (A.) and in each region (B.) in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

Proportions of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in each region and the world (%). The countries making up each region are specified below.

| A. | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | A | B | C | D | F | G | H | J | K | CRF01_AE | CRF02_AG | CRF03_AB | Other CRFs a | URFs b | Total CRFs c | Total CRFs & URFs d | |

| Global | 2000–2003 e | 11.56 | 11.57 | 49.62 | 2.87 | 0.44 | 4.50 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 4.52 | 5.45 | 0.04 | 1.96 | 7.12 | 11.96 | 19.08 |

| 2004–2007 e | 12.03 | 11.33 | 48.23 | 2.49 | 0.45 | 4.60 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 5.09 | 7.73 | 0.00 | 3.65 | 4.01 | 16.47 | 20.48 | |

| Change f | 0.47 | −0.23 | −1.40 | −0.37 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.57 | 2.28 | −0.04 | 1.69 | −3.11 | 4.51 | 1.40 | |

| 2000–2003 g | 3500000 | 3500000 | 14900000 | 860000 | 130000 | 1400000 | 29000 | 71000 | 7100 | 1400000 | 1600000 | 12000 | 590000 | 2100000 | 3600000 | 5700000 | |

| 2004–2007 g | 3900000 | 3700000 | 15800000 | 820000 | 150000 | 1500000 | 85000 | 38000 | 3400 | 1700000 | 2500000 | 100 | 1200000 | 1300000 | 5400000 | 6700000 | |

| Change h | 13.4 | 6.8 | 5.9 | −5.3 | 13.0 | 11.3 | 191.9 | −46.4 | −52.3 | 22.7 | 54.7 | −99.3 | 103.4 | −38.7 | 50.0 | 16.9 | |

| B. | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of the world | Year i | A | B | C | D | F | G | H | J | K | CRF01_AE | CRF02_AG | CRF03_AB | Other CRFs a | URFs b | Total CRFs c | Total CRFs & URFs d |

| North America | 2000–2003 | 0.88 | 95.55 | 1.08 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 2.22 | 2.48 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.70 | 94.20 | 2.46 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 1.44 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.87 | 1.89 | |

| Change | −0.18 | −1.35 | 1.38 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.30 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.24 | −0.36 | −0.59 | |

| Caribbean | 2000–2003 | 0.03 | 89.67 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 8.64 | 1.25 | 9.50 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.00 | 98.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.68 | 0.00 | 1.68 | |

| Change | −0.03 | 8.66 | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −1.22 | −6.96 | −1.25 | −7.83 | |

| Latin America | 2000–2003 | 0.00 | 74.90 | 8.99 | 0.06 | 4.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 2.29 | 9.04 | 2.32 | 11.36 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.00 | 67.89 | 6.53 | 0.04 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 11.29 | 10.67 | 11.34 | 22.01 | |

| Change | 0.00 | −7.01 | −2.46 | −0.02 | −1.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 9.01 | 1.63 | 9.02 | 10.65 | |

| Western and Central Europe | 2000–2003 | 2.22 | 84.13 | 2.90 | 0.73 | 0.41 | 2.82 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 2.94 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.88 | 4.73 | 6.61 |

| 2004–2007 | 1.76 | 85.20 | 1.91 | 0.27 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 2.57 | 6.73 | 9.30 | |

| Change | −0.45 | 1.07 | −0.99 | −0.46 | 0.07 | −1.82 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.22 | 1.56 | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 2.00 | 2.69 | |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 2000–2003 | 78.81 | 14.09 | 1.19 | 0.26 | 2.45 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 1.55 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 2.34 | 2.95 |

| 2004–2007 | 80.01 | 15.20 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.44 | 1.69 | 2.13 | |

| Change | 1.20 | 1.12 | 0.32 | −0.26 | −1.31 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | −0.04 | −1.55 | 0.43 | −0.16 | −0.65 | −0.82 | |

| India | 2000–2003 | 1.40 | 0.31 | 96.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.29 | 0.47 | 1.76 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.89 | 1.34 | 97.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Change | −0.50 | 1.03 | 1.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.10 | −1.29 | −0.47 | −1.76 | |

| South and South-East Asia (excl. India) | 2000–2003 | 2.89 | 9.12 | 3.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 79.57 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 5.03 | 79.89 | 84.92 |

| 2004–2007 | 10.24 | 3.62 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 78.60 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 3.70 | 3.74 | 82.35 | 86.10 | |

| Change | 7.35 | –5.49 | –2.99 | –0.01 | 0.00 | –0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | –0.97 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 3.39 | –1.29 | 2.46 | 1.18 | |

| East Asia | 2000–2003 | 0.66 | 33.06 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 10.58 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 51.53 | 3.93 | 62.22 | 66.15 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.24 | 26.17 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 27.62 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 40.89 | 3.19 | 68.96 | 72.15 | |

| Change | −0.43 | −6.89 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 17.04 | 0.35 | 0.00 | −10.64 | −0.75 | 6.74 | 6.00 | |

| Oceania | 2000–2003 | 0.51 | 87.62 | 5.19 | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.39 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 5.85 | 6.02 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.24 | 31.17 | 66.34 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 1.78 | 2.10 | |

| Change | −0.27 | −56.45 | 61.15 | −0.54 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −3.15 | −0.72 | 0.00 | −0.21 | 0.16 | −4.08 | −3.92 | |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2000–2003 | 0.76 | 57.25 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 2.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.98 | 0.00 | 3.82 | 22.14 | 16.79 | 38.93 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.98 | 53.59 | 0.45 | 2.23 | 0.37 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 18.08 | 0.00 | 21.34 | 1.10 | 39.45 | 40.55 | |

| Change | 0.21 | −3.67 | 0.45 | 1.46 | 0.37 | −0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 5.11 | 0.00 | 17.53 | −21.03 | 22.65 | 1.62 | |

| West Africa | 2000–2003 | 18.73 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 27.87 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 35.23 | 0.00 | 4.79 | 11.59 | 40.37 | 51.96 |

| 2004–2007 | 4.36 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 1.87 | 0.84 | 27.59 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 50.07 | 0.00 | 6.20 | 7.66 | 56.34 | 64.00 | |

| Change | −14.37 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 1.42 | 0.52 | −0.28 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.28 | 14.84 | 0.00 | 1.41 | −3.93 | 15.97 | 12.04 | |

| East Africa (excl. Ethiopia) | 2000–2003 | 38.00 | 0.05 | 19.08 | 16.89 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 25.28 | 0.29 | 25.57 |

| 2004–2007 | 50.80 | 0.01 | 22.97 | 13.80 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 10.90 | 1.12 | 12.02 | |

| Change | 12.80 | −0.03 | 3.89 | −3.08 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.60 | −14.38 | 0.83 | −13.55 | |

| Ethiopia | 2000–2003 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 98.30 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 97.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.56 | 2.56 | |

| Change | −1.28 | 0.00 | −0.86 | −0.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.56 | 2.56 | |

| Central Africa | 2000–2003 | 28.74 | 0.14 | 7.98 | 8.81 | 2.45 | 12.35 | 2.90 | 6.73 | 0.72 | 1.69 | 5.15 | 0.00 | 5.54 | 16.78 | 12.38 | 29.17 |

| 2004–2007 | 11.15 | 0.53 | 5.75 | 8.51 | 2.69 | 18.17 | 7.41 | 1.39 | 0.07 | 4.07 | 7.86 | 0.00 | 24.03 | 8.39 | 35.96 | 44.34 | |

| Change | −17.59 | 0.39 | −2.24 | −0.30 | 0.23 | 5.82 | 4.51 | −5.35 | −0.66 | 2.37 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 18.49 | −8.40 | 23.57 | 15.18 | |

| Southern Africa | 2000–2003 | 0.06 | 0.69 | 98.77 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 2004–2007 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 98.31 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.99 | |

| Change | 0.14 | −0.65 | −0.46 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.76 | |

Circulating Recombinant Forms (CRFs) other than CRF01_AE, CRF02_AE and CRF03_AB.

Unique Recombinant Forms (URFs).

The combined proportions of CRF01_AE, CRF02_AE, CRF03_AB, and other CRFs.

The combined proportions of all CRFs (see c) and URFs (see b).

Global proportions of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants are presented for the periods indicated (%).

Global changes between the two periods in the proportions of each subtype/recombinant (percentage points).

The global number of infections caused by each subtype/recombinant in the periods indicated. Figures are rounded off.

Changes between the two periods in the global numbers of each subtype/recombinant (%).

Proportions of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants are presented for each region for the periods indicated. Changes between the two periods in the proportions of each subtype in each region (percentage points).

Data analysis

The HIV-1 subtype distribution in each region was determined by first multiplying the proportions of all subtypes and recombinants in each country in each period (2000–2003 or 2004–2007) by the estimated (average) number of people living with HIV in the same country in the relevant period. The resulting numbers of each subtype in each country in each region were added up and used to calculate the proportions of the different subtypes and recombinants in each region. Countries for which no HIV-1 subtyping data had been obtained were not included in this part of the analysis.

To determine the global distribution of HIV-1 variants, the regional proportions of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants were multiplied by the number of HIV-1 infected individuals in each region (including countries for which no subtyping data were obtained). The resulting total numbers of people living with each subtype in each region were added up and the global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants was derived.

To determine the spread over the regions of individual subtypes, the estimated number of infections caused by a subtype in each region was taken as a proportion of the global number of infections caused by that same subtype.

Results

Primary HIV-1 subtype distribution data

HIV-1 subtype characterisation data were collected from a total of 65913 samples from HIV-infected individuals in 109 countries between 2000 and 2007. For our analysis the data were divided into two time periods (2000–2003 and 2004–2007) and 15 geographical regions (Methods, Table1, legend to Table2). In 2000–2003, 39148 samples from 95 countries were analysed, and in 2004–2007, 26765 samples from 70 countries were available.

Table 1.

Global and regional HIV-1 epidemiology and sample collection

| Number of individuals living with HIV (n) a |

HIV infections as a proportion of global total (%) b |

Change in the number of HIV infections (%) c |

Number of samples collected (n) |

Depth of sampling (%) d |

Number of countries with HIV-1 subtype data (n) e |

Coverage of region (%) f |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of the world | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | |

| North America | 1100000 | 1200000 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 11.0 | 2097 | 4117 | 0.195 | 0.346 | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Caribbean | 210000 | 230000 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 9.1 | 539 | 56 | 0.258 | 0.025 | 4 | 4 | 39.2 | 90.9 |

| Latin America | 1400000 | 1500000 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 10.7 | 5395 | 3899 | 0.392 | 0.256 | 13 | 7 | 77.9 | 75.2 |

| Western and Central Europe | 620000 | 700000 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 13.2 | 14108 | 7334 | 2.278 | 1.046 | 16 | 8 | 88.3 | 69.6 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 780000 | 1400000 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 81.1 | 2071 | 623 | 0.267 | 0.044 | 11 | 5 | 98.8 | 67.0 |

| India | 2700000 | 2500000 | 9.0 | 7.6 | −7.4 | 685 | 449 | 0.025 | 0.018 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| South and South-East Asia (excl. India) | 1600000 | 1800000 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 13.1 | 2137 | 2084 | 0.136 | 0.117 | 8 | 7 | 84.6 | 67.3 |

| East Asia | 510000 | 690000 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 34.7 | 1972 | 2142 | 0.384 | 0.310 | 3 | 3 | 100.0 | 99.9 |

| Oceania | 28000 | 57000 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 105.2 | 906 | 1105 | 3.286 | 1.953 | 2 | 3 | 56.1 | 97.7 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 310000 | 360000 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 16.2 | 283 | 363 | 0.091 | 0.101 | 5 | 3 | 4.1 | 5.5 |

| West Africa | 4200000 | 4600000 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 7.7 | 3252 | 1398 | 0.077 | 0.031 | 10 | 7 | 94.0 | 87.2 |

| East Africa (excl. Ethiopia) | 4400000 | 4400000 | 14.6 | 13.5 | 0.2 | 3098 | 2002 | 0.071 | 0.046 | 6 | 4 | 98.9 | 95.5 |

| Ethiopia | 920000 | 930000 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 235 | 39 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Central Africa | 910000 | 1100000 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 17.1 | 979 | 388 | 0.107 | 0.036 | 6 | 6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Southern Africa | 10000000 | 11000000 | 34.5 | 34.6 | 9.0 | 1391 | 766 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 7 | 9 | 96.0 | 96.0 |

| Global | 30000000 | 33000000 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 9.0 | 39148 | 26765 | 0.130 | 0.082 | 95 | 70 | 94.0 | 90.1 |

The numbers of individuals living with HIV were obtained from the UNAIDS/WHO estimates of the burden of HIV[26]. The average of the numbers of infections in the periods 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 are shown. Figures are rounded off.

The numbers of individuals living with HIV in each region as a proportion of the global total, based on the averages of the numbers of infections in each period (%).

The change in the number of HIV infections between the periods 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 as a proportion of the number of infections in 2000–2003 (%).

The number of samples collected from a region as a proportion of the number of people living with HIV in the region (%).

Countries for which HIV subtype data was collected are specified in the legend of Table 2.

The combined number of people living with HIV in the countries for which HIV subtype distribution data were collected in a region (see legend of Table 2), as a proportion of the total number of people living with HIV in the region. If any data was available for a country (independent of the number of samples collected), the whole HIV-infected population in that country was deemed to be represented in this analysis.

Worldwide the countries for which HIV-1 subtype distribution data were collected accounted for 94% and 90% of individuals living with HIV-1 in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007, respectively (Table1, last column). In nine out of the 15 regions, for both time periods, the countries with subtype data represented more than 90% of people living with HIV in the region.

The number of samples analysed as a proportion of the number of people living with HIV was higher in 2000–2003 than 2004–2007 globally as well as in all but two regions (Table1, 3rd last column). The proportion of the infected population sampled varied between regions and was higher in the Americas, Western and Central Europe, East Asia, and Oceania, whereas India, Middle East & North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa were less well represented.

Global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants

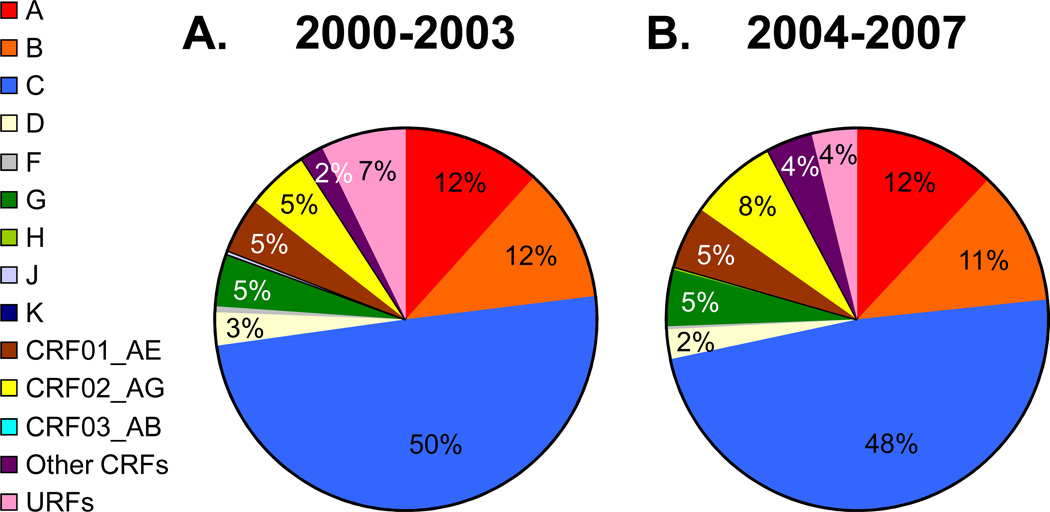

The distribution of HIV-1 subtypes in individual countries was weighted according to the number of HIV-infected people in each country to generate estimates of regional and global HIV-1 subtype distribution for the 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 (Figure1,Table2A). In 2004–2007 subtype C accounted for nearly half (48%) of all global infections. Subtypes A and B caused 12% and 11% of infections, respectively, followed by CRF02_AG (8%), CRF01_AE (5%), subtype G (5%) and D (2%). Subtypes F, H, J and K together caused fewer than 1% of infections worldwide. Other CRFs and URFs are each responsible for 4% of global infections, bringing the combined total of worldwide CRFs (CRF01_AE, CRF02_AG, CRF03_AB and other CRFs) to 16% and all recombinants (all CRFs and URFs) to over 20% (Figure1,Table2A).

Figure 1. Global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

The number of infections caused by HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants are represented as a proportion of the global total number of people living with HIV-1 in 2000–2003 (A.) and 2004–2007 (B.) (see Table 2A). The colours representing the different HIV-1 subtypes are indicated in the legend on the left-hand side of the figure.

Overall, the global distributions of subtypes were similar between 2000–2003 and 2004–2007 and in line with previous estimates [4, 6, 25]. Three epidemiological trends were noted (Table2A). Firstly, an increase in the global proportion (and absolute growth) of the epidemics of subtypes A, F, G, H, CRF01_AE, CRF02_AG and other CRFs was observed. Secondly, the epidemics caused by subtypes D, J, K, CRF03_AB and URFs decreased in size and thus their proportion of the global total became smaller. Thirdly, the epidemics caused by subtypes B and C grew at a rate below the average, resulting in a decrease of their proportion of the global epidemic, though subtype C still caused the largest absolute increase in number of infections.

The global proportion of all CRFs combined increased by 4.5%, which corresponds to a 50% increase in the number of infections. In contrast, the proportion of infections caused by URFs diminished by 3.1%, a 39% decrease of the burden of URFs. Together, all recombinants (CRFs & URFs) increased by 17%, resulting in a 1.4% increase in the proportion of recombinant infections to a total of 20.5% (Table2A). These changes reflect a widespread trend, as an increase in the proportion of other CRFs and a decrease in URFs is widely observed in 10 of the 15 regions (Table2B). It is further notable that, among the major subtypes, subtype A increased and subtype D decreased globally (Table2A).

Regional distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants

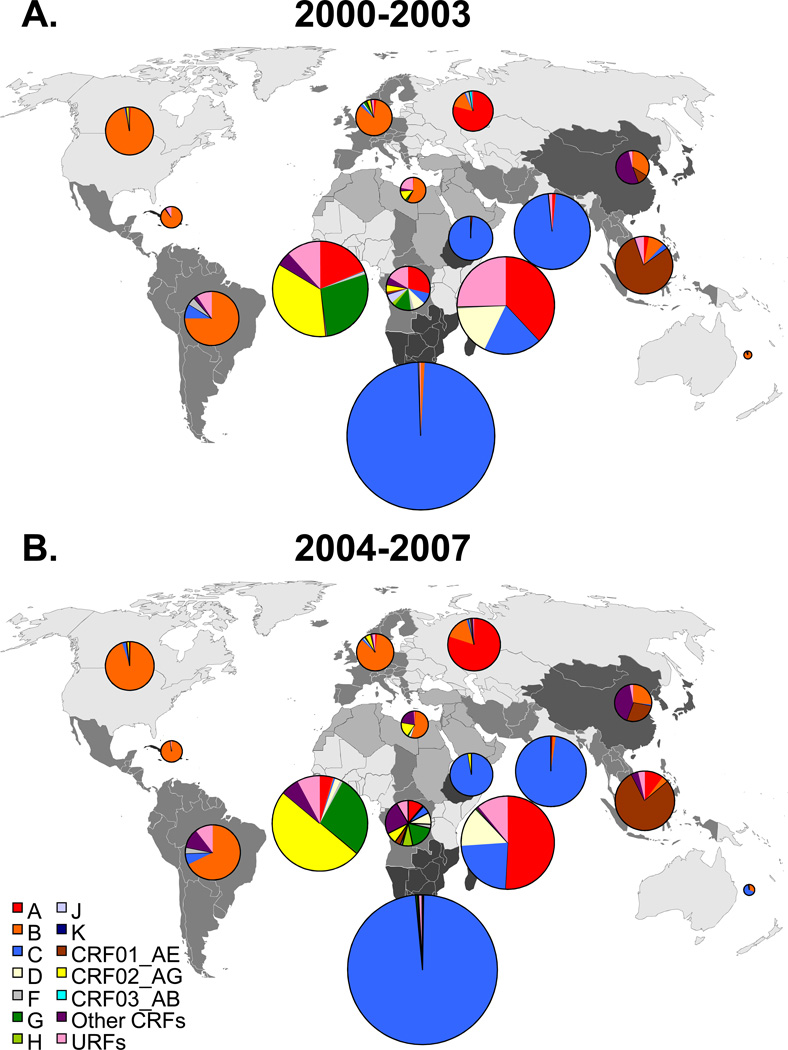

The distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in each region is strikingly different across the world (Figure2, Table2B, and Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows the subtype distribution in individual countries in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007). Changes in regional subtype distributions are shown in table 2B. The regional subtype distributions in 2004–2007 are discussed here.

Figure 2. Regional distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

The world was divided into 15 regions consisting of groups of countries as specified in the Methods. Countries forming a region are shaded in the same colour. Pie-charts representing the distribution of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in each region in 2000–2003 (A.) and 2004–2007 (B.) are superimposed on the regions. The pie-charts were prepared using the data presented in Table 2B. The colours representing the different HIV-1 subtypes are indicated in the legend on the left-hand side of the figure. The relative surface areas of the pie-charts correspond to the relative numbers of people living with HIV in the regions (Table 1).

Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organisation or the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate borderlines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The greatest diversity is found in Central Africa where all subtypes and many CRFs and URFs are represented (Figure2, Table2B, and SDC1). The six countries in this region all harbour a great subtype diversity, but differ in the dominant subtypes (see SDC1). In the Democratic Republic of the Congo all subtypes, CRF01_AE, CRF02_AG and many other CRFs and URFs are found, except subtype B (see SDC1).

In West Africa all subtypes are detected with the dominant variants being CRF02_AG and subtype G. In East Africa the majority of infections are due to subtype A, with the remainder due to subtypes C and D, and URFs. In Southern Africa, Ethiopia and India the epidemics are nearly exclusively caused by subtype C.

Subtype B dominates in North America, the Caribbean, Latin America, Western and Central Europe and Australia. In Western and Central Europe all major subtypes and many CRFs and URFs are detected. The epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia is dominated by subtype A and subtype B.

In South and South-East Asia CRF01_AE is responsible for the vast majority of infections. In this region the combined proportion of all recombinant infections is 86%, which is the highest in the world. In East Asia the epidemic is dominated by CRF07_BC & CRF08_BC, CRF01_AE, and subtype B. The Middle East and North Africa is mainly affected by subtype B and various CRFs.

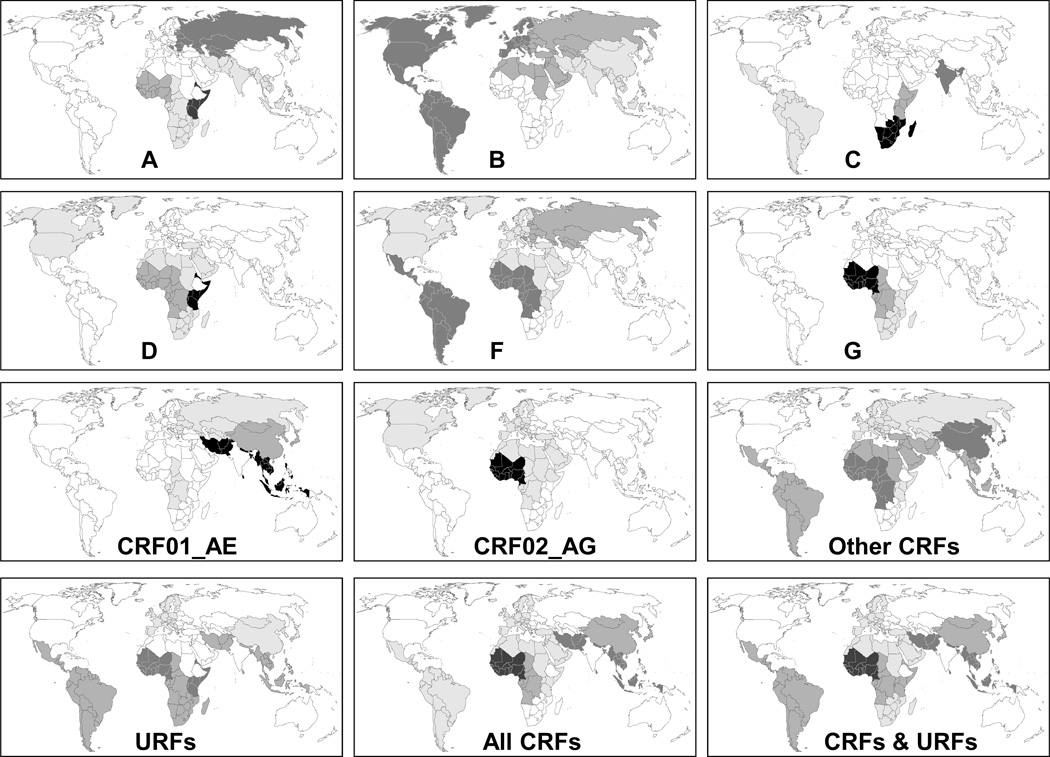

Global spread of individual HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants

The distribution of individual HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants across the globe is shown in Figure3 and Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3. The majority of global dominant subtype C is present in Southern Africa and India, with further infections in East Africa and Ethiopia (Table2). Subtype A is mainly found in East Africa and Eastern Europe & Central Asia, with the remainder in West and Central Africa and South & South-East Asia. The subtype B epidemic is more widely and evenly spread than the other subtypes. For eight subtypes/CRFs analysed 95% of infections are contained in only three or fewer regions. In contrast, 95% of subtype B is spread over 7 regions (Figure3, SDC2&3). Interestingly, hardly any subtype B infections are found in sub-Saharan Africa.

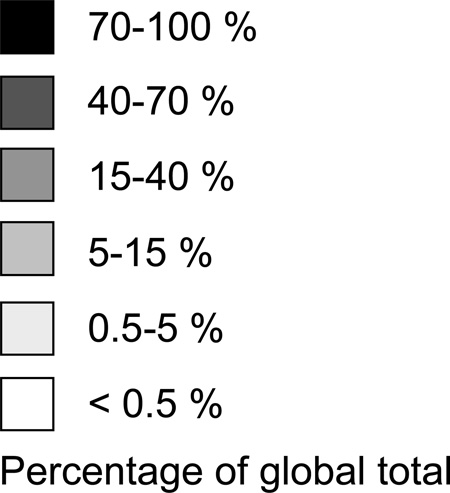

Figure 3. Global distribution of individual HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in 2004–2007.

For each subtype/recombinant indicated each of the 15 regions is shaded according to the proportion of the global number of infections caused by the subtype/recombinant present in each region.

CRF02_AG is the fourth largest variant globally and is concentrated in West Africa, with smaller numbers in Central Africa and the Middle East & North Africa. CRF01_AE is the fifth largest subtype and is found in South & South-East Asia, East Asia and a small number in Central Africa.

Subtype G is concentrated in West and Central Africa. Subtype D is present mainly in Eastern Africa, with further infections in Central and West Africa. Subtype F is widely and evenly spread worldwide, whereas subtype H, J and K are found in Central, Southern and West Africa. CRF03_AB does not play a significant role globally or regionally.

Other CRFs are differentially distributed over West Africa (mainly CRF06_cpx), East Asia (mainly CRF07_BC & CRF08_BC in China), Central Africa (CRF11_cpx among others), Latin America (CRF12_BF, CRF28_BF, CRF31_BC, CRF38_BF, and others), Middle East & North Africa (mainly CRF06_cpx), and South & South-East Asia (mainly CRF35_AD and CRF07_BC). A wide variety of URFs is distributed over sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America (mainly unique BF recombinants) and South and South-East Africa.

Discussion

The global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes was broadly stable over the 2000–2007 period, with an overall increase in recombinants (Figure1,Table2A) and dynamic changes in some regions (Figure2, Table2B, SDC1). The global HIV subtype distribution was broadly similar to estimated distributions obtained using published data only, as well as estimates calculated by combining country HIV subtype distributions in the Los Alamos database with the country-specific numbers of HIV-infected people used in our study [4, 6, 25](data not shown). The observed trends in subtype distribution between the periods were caused by an interplay between changes in subtype distribution in countries and in the numbers of HIV-infected people (Tables1&2, SDC1). These changes over an 8-year period are consistent with a stabilising global epidemic with a significant annual turnover due to new infections and deaths, and rapid growth of certain regional epidemics (Table1)[1].

Our study has some limitations. Some regions had poor coverage because of lack of data (Caribbean, Oceania, Middle East and North Africa; Table 1, last column), some countries and regions had small sample sizes, in particular those which harbour the largest number of infections and have the highest subtype diversity (Table1), and only a small amount of data were obtained from representative national surveys. Moreover, the heterogeneous nature of the data sets from the two time periods precluded a direct comparison and statistical analysis. Sampling biases may have occurred due to patient selection (risk groups, treatment failure, disease progression), limited geographical coverage and consistency within countries, and unknown dates and places of infection. In addition, subtyping methods used and the type and number of genome segments analysed may have affected results. Finally, publication bias may have occurred in the data derived from the literature.

We found a notable increase in the proportion of CRFs, a decrease in URFs and an overall increase in recombinants, although no formal statistical test for trend was used (Table2A). Detailed examination showed that these trends could not be attributed to the subtyping methods used or the type and number of genome segments analysed in the different periods (data not shown). However, given the relatively recent establishment of rules governing CRF nomenclature [5], samples with discordant subtypes in different genome segments may have been classified as recombinants (or URFs), before the relevant CRFs were characterised, especially in the earlier time period. It is probable that the overall proportion of recombinants is underestimated in both periods due to the limited number of full-length sequences available (0.6–5%; data not shown).

Independent studies in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya suggest that subtype D infection is associated with faster disease progression than subtype A in populations where they co-circulate, despite similar plasma viral loads [11–13]. In addition, a higher rate of heterosexual transmission of subtype A than subtype D was reported [14]. A long term study examining the subtype distribution in Kenya during the expanding epidemic found a significant decrease in the proportion of subtype D and a slight increase in subtype A [27]. These reports are consistent with our findings of an increase in the proportion of subtype A and a decrease in subtype D in East Africa and globally.

The explanations for the current global subtype distribution and the recent changes observed are probably multifactorial and include founder effects, population growth and urbanisation, and improved transport links and migration [3, 28]. It is uncertain at present whether biological properties of different subtypes and recombinants play a role in their differential spread.

HIV diversity, in populations and in individuals, is one of the major challenges in HIV vaccine development. It seems clear that vaccine immunogen sequence should match as closely as possible the viral sequences circulating in the target population. Up to date and accurate information on HIV subtype distribution is therefore essential, not least to ensure that efforts and funding are allocated according to the regional and global impact of the various HIV subtypes and recombinants. Our study highlights that the distribution of subtypes and recombinants globally and regionally is extremely complex. This diversity may be addressed by the use of consensus, ancestral, centre-of-tree or mosaic sequences in vaccines [21, 29].

The challenges posed by the genetic diversity of the HIV-1 pandemic to prevention and treatment efforts demand that global molecular epidemiology surveillance is continued and improved. In particular, full length sequencing of samples obtained from nationally representative surveys, taking account of geographical differences and differences in transmission routes/risk groups, are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Regional figures showing subtype distribution in individual countries in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007. Legend as for Figure 2.

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table showing the number of infections caused by a subtype/recombinant in a region as a proportion of the global number of infections caused by that subtype in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Figures showing the global distribution of individual HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007. Legend as for Figure 3.

Acknowledgements

JH conceived and designed the project, collected HIV subtype data from contributors, conducted the literature search, analysed the data, prepared the figures and tables, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. EG provided the HIV epidemiology data, performed statistical analysis and interpreted the data. PDG provided supervision and interpreted the data. SO conceived and designed the project, provided supervision and interpreted the data. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript. Members of the WHO-UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterisation contributed HIV subtyping data to the study.

Financial support:

JH is an Academic Clinical Fellow supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), United Kingdom.

Appendix

Contributing members of the WHO/UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterisation [name of contributor (country where contributor is based)]: S. Agwale (Nigeria), J-P. Allain & L. Fischetti (UK), C. Archibald, J Brooks & M. Ofner (Canada), E. Belabbes (Algeria), J. Brandful (Ghana), M. Bruckova & M. Linka (Czech Republic), F. Buonaguro & L. Buonaguro (Italy), J. Carr (USA), D. Cooper, T. Kelleher, A. Carrera & P. Cunningham (Australia), D. Dwyer & F. Raikanikoda (Australia), B. Ensoli & S. Butto (Italy), M. Essex & V. Novitsky (USA), H. Fleury (France), F. Gao (USA), G-M. Gershy-Damet (Zimbabwe), Z. Grossman & S. Maayan (Israel), X. He (China), D. Ho & L. Zhang (USA), M. Hoelscher (Germany), M. Hosseinipour & J. van Oosterhout (Malawi), P. Kaleebu & R. Goodall (Uganda), M. Kalish (USA), P. Kanki (USA), E. Karamov (Russian Federation), D. Kombate-Noudjo & A. Dagnra (Togo), T. Leitner (USA), I. Lorenzana de Rivera (Honduras), F. McCutchan (USA), F. Mhalu, W. Urassa, F. Mosha & D. Mloka (Tanzania), M. Morgado (Brazil), J. Mullins, M. Campbell, C. Rousseau, J. Herbeck & M. Rolland (USA), J. Najera & M. Thomson (Spain), P. Nyambi (USA), A. Papa (Greece), J. Pape & C. Nolte (Haiti), M. Peeters (France), J-M. Reynes (Cambodia), M. Salminen (Finland), H. Salomon & M. Carillo (Argentina), B. Schroeder (New Zealand), M. Segondy & B. Montes (France), J. Servais, A. Pelletier, K. Kayitenkore & J-C Karasi (Rwanda), R. Shankarappa (USA), Y. Shao, X. He & J. Xu (China), T. Smolskaya (Russian Federation), M. Soares & A. Tanuri (Brazil), E. Songok (Kenya), R. Sutthent (Thailand), Y. Takebe (Japan), H. Ushijima & T. Quang (Japan & Vietnam), P. Van de Perre & Méda (Burkina Faso), A. van Sighem (Netherlands), A-M. Vandamme & J. Vercauteren (Belgium), C. Williamson, H. Bredell & D. Stewart (South Africa), D. Wolday (Ethiopia), J. Xu (China), C. Yang (USA), D. Yirrell (UK), L. Zhang, R. Zhang & Z. Chen (China).

Composition of regions

Countries are underlined if HIV-1 subtype distribution data was obtained for the period 2000–2003 (hatched; ), 2004–2007 (single underlined; ), or both 2000–2003 & 2004–2007 (double underlined; ).

North America: Canada, USA;

Caribbean: Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago;

Latin America: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela;

Western and Central Europe: Albania, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, The Former Yugoslav Republic Macedonia, the United Kingdom;

Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan; India

South and South-East Asia (excl. India): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Viet Nam;

East Asia: China, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Republic of Korea;

Oceania: Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea;

Middle East and North Africa: Algeria, Bahrain, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen;

West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo;

East Africa (excl. Ethiopia): Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Somalia, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania; Ethiopia;

Central Africa: Angola, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon;

Southern Africa: Botswana, Comoros, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Footnotes

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, which does not necessarily reflect the views of the World Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

Conflict of interest:

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update 2009. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Takehisa J, Santiago ML, et al. Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006;313:523–526. doi: 10.1126/science.1126531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worobey M, Gemmel M, Teuwen DE, Haselkorn T, Kunstman K, Bunce M, et al. Direct evidence of extensive diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960. Nature. 2008;455:661–664. doi: 10.1038/nature07390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Los Alamos National Laboratory. http://www.hiv.lanl.gov.

- 5.Robertson DL, Anderson JP, Bradac JA, Carr JK, Foley B, Funkhouser RK, et al. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science. 2000;288:55–56. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.55d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemelaar J, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Osmanov S. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS. 2006;20:W13–W23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247564.73009.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plantier JC, Leoz M, Dickerson JE, De Oliveira F, Cordonnier F, Lemee V, et al. A new human immunodeficiency virus derived from gorillas. Nat Med. 2009;15:871–872. doi: 10.1038/nm.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JE, Beckthold B, Chen Z, Mihowich J, Malloch L, Gill MJ. Short communication: identification of a novel HIV type 1 subtype H/J recombinant in Canada with discordant HIV viral load (RNA) values in three different commercial assays. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1309–1313. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geretti AM, Harrison L, Green H, Sabin C, Hill T, Fearnhill E, et al. Effect of HIV-1 subtype on virologic and immunologic response to starting highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1296–1305. doi: 10.1086/598502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Cajas JL, Pai NP, Klein MB, Wainberg MA. Differences in resistance mutations among HIV-1 non-subtype B infections: a systematic review of evidence (1996–2008) J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiwanuka N, Laeyendecker O, Robb M, Kigozi G, Arroyo M, McCutchan F, et al. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 (HIV-1) subtype on disease progression in persons from Rakai, Uganda, with incident HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:707–713. doi: 10.1086/527416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeten JM, Chohan B, Lavreys L, Chohan V, McClelland RS, Certain L, et al. HIV-1 subtype D infection is associated with faster disease progression than subtype A in spite of similar plasma HIV-1 loads. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1177–1180. doi: 10.1086/512682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasan A, Renjifo B, Hertzmark E, Chaplin B, Msamanga G, Essex M, et al. Different rates of disease progression of HIV type 1 infection in Tanzania based on infecting subtype. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:843–852. doi: 10.1086/499952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiwanuka N, Laeyendecker O, Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Shepherd J, Robb M, et al. HIV-1 subtypes and differences in heterosexual HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2009;23:2479–2484. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330cc08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renjifo B, Gilbert P, Chaplin B, Msamanga G, Mwakagile D, Fawzi W, et al. Preferential in-utero transmission of HIV-1 subtype C as compared to HIV-1 subtype A or D. AIDS. 2004;18:1629–1636. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131392.68597.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goonetilleke N, Liu MK, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Ferrari G, Giorgi E, Ganusov VV, et al. The first T cell response to transmitted/founder virus contributes to the control of acute viremia in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1253–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature. 2008;455:613–619. doi: 10.1038/nature07352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korber B, Gaschen B, Yusim K, Thakallapally R, Kesmir C, Detours V. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br Med Bull. 2001;58:19–42. doi: 10.1093/bmb/58.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JK, Stewart-Jones G, Dong T, Harlos K, Di Gleria K, Dorrell L, et al. T cell cross-reactivity and conformational changes during TCR engagement. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1455–1466. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, et al. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitisuttithum P, Gilbert P, Gurwith M, Heyward W, Martin M, van Griensven F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a bivalent recombinant glycoprotein 120 HIV-1 vaccine among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1661–1671. doi: 10.1086/508748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arien KK, Vanham G, Arts EJ. Is HIV-1 evolving to a less virulent form in humans? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rainwater S, DeVange S, Sagar M, Ndinya-Achola J, Mandaliya K, Kreiss JK, et al. No evidence for rapid subtype C spread within an epidemic in which multiple subtypes and intersubtype recombinants circulate. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:1060–1065. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray RR, Tatem AJ, Lamers S, Hou W, Laeyendecker O, Serwadda D, et al. Spatial phylodynamics of HIV-1 epidemic emergence in east Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:F9–F17. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832faf61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corey L, McElrath MJ. HIV vaccines: mosaic approach to virus diversity. Nat Med. 2010;16:268–270. doi: 10.1038/nm0310-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Regional figures showing subtype distribution in individual countries in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007. Legend as for Figure 2.

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table showing the number of infections caused by a subtype/recombinant in a region as a proportion of the global number of infections caused by that subtype in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007.

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Figures showing the global distribution of individual HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007. Legend as for Figure 3.