Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Information about primary care physicians’ (PCPs) and oncologists’ involvement in cancer-related follow-up care, and care coordination practices, is lacking but essential to improving cancer survivors’ care. This study assesses PCPs’ and oncologists’ self-reported roles in providing cancer-related follow-up care for survivors who are within five years of completing cancer treatment.

METHODS

In 2009, the National Cancer Institute and American Cancer Society conducted a nationally-representative survey of PCPs (n=1014) and medical oncologists (n=1125) (response rate=57.6%; cooperation rate=65.1%). Mailed questionnaires obtained information on physicians’ roles in providing cancer-related follow-up care to early-stage breast and colon cancer survivors; personal and practice characteristics; beliefs about and preferences for follow-up care; and care coordination practices.

RESULTS

Over 50% of PCPs reported providing cancer-related follow-up care for survivors, mainly by co-managing with an oncologist. In contrast, over 70% of oncologists reported fulfilling these roles by providing the care themselves. In adjusted analyses, PCP co-management was associated with: specialty, training in late or long-term effects of cancer, higher cancer patient volume, favorable attitudes about PCP care involvement, preference for a shared model of survivorship care, and receipt of treatment summaries from oncologists. Among oncologists, only preference for a shared care model was associated with co-management with PCPs.

CONCLUSIONS

PCPs and oncologists differ in their involvement in cancer-related follow-up care of survivors, with co-management more often reported by PCPs than by oncologists. Given anticipated national shortages of PCPs and oncologists, study results suggest that improved communication and coordination between these providers is needed to ensure optimal delivery of follow-up care to cancer survivors.

Keywords: neoplasms, survivorship, physicians, primary health care, physicians’ practice patterns

INTRODUCTION

There are nearly 12 million cancer survivors in the United States, about one-third of whom were diagnosed with breast or colorectal cancer.1 Survivors’ post-treatment care may entail monitoring for recurrence and new primary cancers, managing late or long-term effects of cancer treatment, and health promotion counseling.2 Expert groups have issued guidelines for the follow-up care of breast and colorectal cancer survivors.3-6 These guidelines do not, however, specify which health care professionals should be engaged in providing follow-up care.

Survivorship care can be provided by cancer specialists, primary care physicians (PCPs), nurses, psychologists, and social workers.2 Given the variety of health professionals that could play a role in survivor care, it will often be a shared responsibility, and there should be a designated individual who coordinates the care. Several studies have documented differences in the type and intensity of follow-up care received by breast and colorectal cancer survivors depending on whether patients were followed by oncologists versus PCPs, or by both provider types.8-12 Some studies have shown that survivors who see both an oncologist and a PCP receive better overall care than those followed by only one of these providers.13-15 The importance of identifying ways to optimally deliver survivorship care is heightened by the growing survivor population and anticipated shortages of oncologists and PCPs in the U.S.1; 16-17

Information about PCP and oncologist roles in follow-up care for survivors who have completed cancer treatment, or the extent to which these providers share this responsibility, is limited. In this report, we assess these roles in U.S. clinical practice by using data from a national survey to address the following questions: 1) what are the roles reported by PCPs and oncologists in the cancer-related follow-up care of early-stage breast and colon cancer survivors?, and 2) what factors, including care coordination and communication, are associated with PCPs’ and oncologists’ self-reported role patterns for follow-up care? A particular focus of our analysis is to examine the extent to which these physicians share responsibility for, or co-manage, cancer-related follow-up care. Enhanced understanding of physician roles and practices may help in developing improved models of care for cancer survivors.

METHODS

Physician Sample and Study Cohort

We used data from the nationally-representative Survey of Physicians’ Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS), conducted among PCPs and medical oncologists in 2009. SPARCCS defined cancer survivors as individuals who have completed active treatment for their disease, and focused on care of early-stage breast and colon cancer survivors because of their prevalence in the United States and long survivorship period, and the availability of guidelines for their follow-up care.1, 3-4 SPARCCS’ survey methodology has been described in detail previously.18 Briefly, SPARCCS’ sample was drawn from the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile. Eligible respondents were non-Federal physicians under 76 years of age in the specialties of hematology/oncology, family medicine, general internal medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology who spent 20% or more of their professional time providing patient care. The survey was administered by the research firm Westat and approved by their institutional review board and by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Completed questionnaires were received from 1072 PCPs and 1130 oncologists. The survey’s absolute response rate was 57.5%; the cooperation rate was 65.1%.18

Because our study focused on examining follow-up care for breast and colon cancer survivors, we excluded PCPs who reported never (n=51) or not in the past year (n=7) caring for patients diagnosed with these cancers, and oncologists who reported that they did not care for such patients in the past month (n=2). We also excluded 3 physicians who reported their primary specialty as radiation oncology or surgical oncology. The final study cohort comprised 1014 PCPs and 1125 oncologists.

Questionnaire Items

We assessed physicians’ roles in providing cancer-related follow-up care for patients who are within five years of completing active treatment for early-stage breast cancer by asking respondents how the following services are usually delivered in their practice: screening for 1) recurrent breast cancer and 2) other new primary cancers; evaluating patients for 3) breast cancer recurrence and 4) adverse late or long-term physical effects of cancer or its treatment; and 5) managing adverse late or long-term outcomes of cancer treatment. Corresponding questions were asked about delivery of these same services for colon cancer survivors. For PCPs, response options were: “I order or provide this service myself”, “the oncology specialist orders or provides this service”, “the oncology specialist and I share responsibility for ordering or providing this service”, “another specialist orders or provides this service”, or “I am not involved in this care”. Oncologists’ response options were complementary.

We used a 5-point scale (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree) to ask physicians about their beliefs regarding PCPs’ skills in managing cancer survivors, and whether PCPs should have primary responsibility for providing survivors’ cancer-related follow-up care. We also asked about their preferred model for providing follow-up care. We asked PCPs about the frequency with which they receive a summary with detailed cancer treatment information from the oncologist, and a follow-up care plan with recommendations for future care and surveillance (always/almost always, often, sometimes, rarely, never). Two analogous items asked oncologists about the frequency with which they provide this information to the PCP. An additional item asked PCPs and oncologists about the frequency with which they communicate with their patients’ other physicians about which physician will follow the patient for their cancer.

Other items asked about physicians’ demographic, training, and practice setting characteristics, and practice style (i.e., whether affiliated with a medical school, and patient volume). The full survey instruments are available at: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/surveys/sparccs/.

Measures

We categorized physicians based on their primary specialty as either PCPs (family medicine, general internal medicine, obstetrics/gynecology) or oncologists (medical oncology, hematology/oncology, hematology). To characterize follow-up care roles, we created three categories based on physicians’ responses to each role item: 1) provides=“I order or provide this service myself”; 2) co-manages= “the oncology specialist (or PCP) and I share responsibility for ordering or providing this service”; or 3) not directly involved=“the oncology specialist (or PCP) orders or provides this service”, “another specialist orders or provides this service”, or “I am not involved in this care”. Building on this, we further characterized physicians’ overall role pattern in providing follow-up care, as follows: physicians who directly provided three or more of the five breast cancer services were categorized as predominantly provides; those who co-managed three or more services were categorized as predominantly co-manages; and those not directly involved in three or more services were categorized as predominantly not directly involved. All other physicians were categorized as having no dominant role pattern. The same approach was used for the five colon cancer care items. Finally, we created a summary measure to characterize role patterns across both cancer types: physicians categorized as predominantly provides for breast and for colon cancer were assigned to this same role pattern category for both cancer types; the same approach was used for the remaining role pattern categories (i.e., predominantly co-manages, predominantly not directly involved, and no dominant role pattern). Those physicians who had a different role pattern for breast versus colon cancer were assigned to the category: inconsistent pattern between breast and colon cancer.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted separately for PCPs and oncologists, because of the distinctly different training received and patient populations seen by these physicians. We used descriptive statistics to characterize physicians’ demographic and practice characteristics and role involvement. We hypothesized that physicians’ role patterns might vary by their personal and practice setting characteristics, practice style, beliefs about and preferences for survivors’ follow-up care, and care coordination practices. We used Chi-square statistics to assess the bivariate associations of these variables with three dependent measures: physicians’ role patterns for follow-up care 1) of breast cancer survivors, 2) of colon cancer survivors, and 3) across both survivor types. Variables showing a statistically significant association at p<0.10 were retained for inclusion in multivariate regression models.

Three polytomous logistic regression models were estimated for PCPs, with a three-level dependent variable corresponding to: predominantly provides versus predominantly co-manages versus predominantly not directly involved in follow-up care. The first model examined the association of PCP characteristics with this dependent variable for breast cancer survivors’ care; the second for colon cancer survivors’ care; and the third for both survivor types. Three binary logistic regression models were then estimated for oncologists, with the dependent variable comparing predominantly provides versus predominantly co-manages follow-up care. The first model assessed oncologist characteristics associated with care for breast cancer survivors, the second care for colon cancer survivors, and the third care for both survivor types. Because the patterns of association for the breast and colon cancer models were similar, for both PCPs and oncologists, we report only results for the models that examined role patterns across both survivor types.

Survey weights adjusting for undercoverage and survey nonresponse were applied in the analyses; the weighted data yield national estimates. SUDAAN version 10.0.1 was used in the analyses to account for the complex survey design.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Respondents

Characteristics of the 2,139 physicians in our study cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physicians and their practice settings

|

Primary Care

(n=1014) |

Oncology

(n=1125) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n |

Weighted

% |

n |

Weighted

% |

|

| ||||

| Physician | ||||

|

| ||||

| Years since graduation from medical school: | ||||

| <10 | 125 | 12.3 | 174 | 16.1 |

| 10-19 | 343 | 33.4 | 313 | 30.4 |

| 20-29 | 294 | 30.4 | 301 | 27.5 |

| ≥30 | 252 | 23.9 | 337 | 26.0 |

|

| ||||

| Gender (male) | 675 | 64.3 | 834 | 72.9 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity: | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 706 | 70.6 | 724 | 62.8 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 46 | 4.9 | 25 | 2.2 |

| Hispanic | 61 | 6.5 | 43 | 3.9 |

| Asian | 168 | 14.7 | 295 | 27.9 |

| Other/multiple races | 6 | 0.5 | 12 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||

| Primary care specialty: | NA | NA | ||

| Family medicine | 455 | 43.5 | ||

| General internal medicine | 478 | 37.9 | ||

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 81 | 18.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| Board certified | 850 | 83.1 | 1012 | 89.6 |

|

| ||||

| International medical graduate | 263 | 23.3 | 368 | 35.4 |

|

| ||||

| Received training in late/long-term effects of cancer or its treatment: |

||||

| Yes, in detail | 48 | 4.2 | 404 | 35.9 |

| Yes, somewhat | 624 | 60.4 | 636 | 56.8 |

| No | 326 | 34.1 | 82 | 7.0 |

|

| ||||

| Primary practice arrangement: | ||||

| Full/part owner of physician practice | 552 | 55.8 | 527 | 45.2 |

| Employee of physician-owned practice | 95 | 10.2 | 118 | 11.2 |

| Employee of large medical group, HMO, or health care system |

186 | 17.2 | 116 | 10.6 |

| Employee of university hospital/clinic | 61 | 5.8 | 240 | 21.7 |

| Employee of other hospital/clinic | 111 | 10.3 | 99 | 8.7 |

| Other | 9 | 0.8 | 25 | 1.3 |

|

| ||||

| Practice setting | ||||

|

| ||||

| Practice size (# physicians): | ||||

| 1 | 250 | 24.0 | 121 | 10.1 |

| 2-5 | 420 | 42.9 | 434 | 39.2 |

| 6-15 | 222 | 21.8 | 339 | 29.7 |

| ≥16 | 103 | 9.5 | 210 | 19.1 |

| Don’t know | 19 | 1.8 | 21 | 1.9 |

|

| ||||

| Practice located in MSA ≥ 1 million population | 620 | 61.7 | 723 | 65.4 |

|

| ||||

| Census region: | ||||

| Northeast | 215 | 20.7 | 284 | 25.2 |

| Midwest | 255 | 23.5 | 241 | 21.4 |

| West | 325 | 34.4 | 384 | 34.0 |

| South | 219 | 21.3 | 216 | 19.4 |

|

| ||||

| Type of medical record system: | ||||

| Full Electronic Medical Record (EMR) | 326 | 30.8 | 372 | 33.3 |

| Partial EMR | 127 | 13.1 | 215 | 19.3 |

| Transitioning from paper to EMR | 158 | 14.7 | 282 | 24.3 |

| Paper charts | 386 | 40.0 | 246 | 21.7 |

|

| ||||

| % patients uninsured: | ||||

| 0-5 | 634 | 63.4 | 757 | 66.6 |

| 6-25 | 288 | 28.0 | 237 | 20.7 |

| ≥26 | 46 | 4.3 | 47 | 4.3 |

| Don’t know/Missing | 46 | 4.2 | 84 | 8.3 |

|

| ||||

| Physician practice style | ||||

|

| ||||

| Has an affiliation with a medical school | 398 | 40.3 | 580 | 51.6 |

|

| ||||

| Patient volume during a typical week: | ||||

| ≤75 | 319 | 31.4 | 623 | 55.8 |

| 76-100 | 355 | 34.9 | 298 | 26.4 |

| 101-125 | 198 | 20.0 | 123 | 10.6 |

| ≥126 | 123 | 12.0 | 70 | 5.9 |

|

| ||||

| # breast and colon cancer patients seen in past year (mean) |

37.9 | NA | ||

|

| ||||

| # breast and colon cancer patients seen in a typical week (mean) |

NA | 34.9 | ||

Data source: Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS) Some frequencies may not add to 100% due to missing values.

NA = Not Applicable

Physicians’ Cancer-Related Follow-up Care Roles and Role Patterns

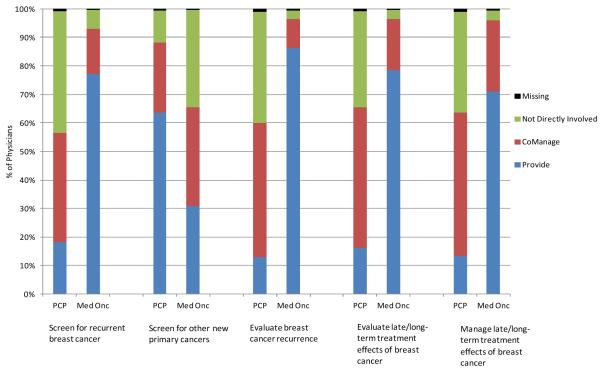

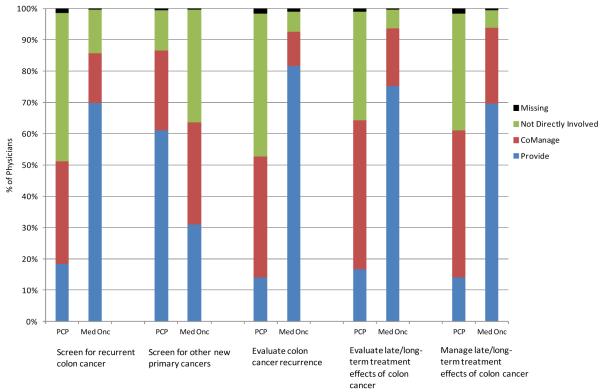

The majority of PCPs reported involvement in cancer-related follow-up care of breast and colon cancer survivors, although they more often co-managed than directly provided this care, with the exception of screening for other new primary cancers (Figure 1). In screening for recurrent cancer, 18% directly provided and 38% co-managed for breast, while 18% directly provided and 33% co-managed for colon cancer survivors. In evaluating for cancer recurrence, 13% directly provided and 47% co-managed for breast, and 14% directly provided while 39% co-managed for colon cancer survivors. In evaluating late/long-term treatment effects, 16% directly provided and 49% co-managed for breast, while 17% directly provided and 48% co-managed for colon cancer survivors; results for managing late/long-term treatment effects were similar. In screening for other new primary cancers, 64% directly provided and 25% co-managed for breast, while 61% directly provided and 26% co-managed for colon cancer survivors. In contrast, 70% or more of oncologists indicated that they directly provided cancer-related follow-up care for all roles except screening for other new primary cancers; for this role, about one-third of oncologists reported directly providing, and another one-third said that they co-managed this care with a PCP.

Figure 1A.

Involvement of primary care physicians (PCPs) and medical oncologists in cancer-related follow-up care for breast cancer survivors

Physicians’ role patterns across both cancers were similar to those for the individual cancer types (Table 2). Co-management with an oncologist was a common pattern for PCPs (42% for breast cancer; 36% for colon cancer; 30% for both cancer types), while directly providing follow-up care was highly prevalent among oncologists (79% for breast cancer; 73% for colon cancer; 70% for both cancer types). In contrast, co-management was a dominant pattern for less than 15% of oncologists, and direct provision of follow-up care was a dominant pattern for relatively few PCPs (15% for breast cancer; 16% for colon cancer; 11% for both cancer types). Small proportions of PCPs (<15%) and oncologists (<10%) had no dominant pattern. Role patterns were inconsistent between breast and colon cancer for 26% of PCPs and 15% of oncologists.

Table 2.

Role patterns for cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors, by cancer type and physician specialty

| Primary care (n=1014) |

Oncology (n=1125) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | (95% CI) | n | % | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| Role pattern1 for breast cancer follow-up care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Predominantly provides | 158 | 14.5 | (12.4-16.9) | 887 | 78.5 | (75.9-80.9) |

| Predominantly co-manages | 441 | 41.8 | (38.4-45.2) | 143 | 12.9 | (11.2-14.9) |

| Predominantly not directly involved | 262 | 29.4 | (26.3-32.7) | 30 | 2.7 | (1.9-4.0) |

| No dominant pattern | 136 | 12.7 | (10.8-14.9) | 61 | 5.5 | (4.3-7.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Role pattern1 for colon cancer follow-up care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Predominantly provides | 184 | 16.1 | (14.0-18.5) | 825 | 73.2 | (70.3-76.0) |

| Predominantly co-manages | 394 | 35.6 | (32.6-38.8) | 152 | 13.6 | (11.5-16.0) |

| Predominantly not directly involved | 279 | 33.6 | (30.8-36.5) | 66 | 5.9 | (4.6-7.6) |

| No dominant pattern | 141 | 13.1 | (11.1-15.5) | 72 | 6.4 | (5.0-8.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Role pattern2 for both cancer types | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Predominantly provides | 121 | 10.9 | (9.1-13.0) | 785 | 69.6 | (66.5-72.4) |

| Predominantly co-manages | 326 | 29.7 | (26.9-32.8) | 114 | 10.2 | (8.5-12.3) |

| Predominantly not directly involved | 208 | 24.5 | (21.7-27.5) | 12 | 1.1 | (0.6-2.1) |

| No dominant pattern | 73 | 6.4 | (5.1-8.0) | 34 | 3.1 | (2.2-4.3) |

| Inconsistent pattern between breast and colon cancer care |

261 | 26.1 | (23.3-29.1) | 169 | 15.0 | (13.0-17.3) |

Data source: Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS)

Frequencies do not always add to 100% due to missing values.

Predominantly provides: “I provide myself” for ≥3 of the 5 roles

Predominantly co-manages: “I share responsibility for or co-manage this care” for ≥3 of the 5 roles

Predominantly not directly involved: “Another specialist orders or provides”/”I am not involved” for ≥3 of the 5 roles

Summary measure of role patterns: physicians categorized as predominantly provides for breast and colon cancer were assigned to this same role pattern category for both cancer types; the same approach was used for predominantly co-manages, predominantly not directly involved, and no dominant role pattern. Physicians whose role patterns differed for breast and colon cancer were assigned to the inconsistent pattern between breast and colon cancer category

Physicians’ Beliefs, Preferences, and Care Coordination

Certain beliefs, preferences, and care coordination activities were associated with physicians’ follow-up care role patterns in bivariate analyses (Table 3). PCPs who agreed that PCPs have the skills to provide follow-up care for survivors or initiate screening or diagnostic work-up to detect recurrent cancer were more likely to directly provide or co-manage as their dominant pattern, as were PCPs who agreed that PCPs should have primary responsibility for cancer-related follow-up care. Among oncologists, those with positive views about PCP skills in providing follow-up care or initiating testing to detect recurrent cancer were more likely to co-manage as their dominant pattern, as were those agreeing that PCPs should have primary responsibility for cancer-related follow-up care. For both provider types, those preferring a shared model of survivorship care were more likely to co-manage as their dominant pattern.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations of physicians’ beliefs, preferences, and care coordination with cancer-related follow-up care for breast and colon cancer survivors, by role pattern1 and specialty

| Total2 | Provides | Comanages | Not directly involved |

Other | P-value | Total2 | Provides | Comanages | Not directly involved |

Other | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |||

| PCPs have the skills to: | Primary care (n=989) | Oncology (n=1114) | ||||||||||

| Provide follow-up care for cancer or its treatment effects: |

<0.0001 | 0.0004 | ||||||||||

| Agree breast and/or colon | 63.1 | 15.0 | 33.6 | 18.3 | 33.1 | 25.1 | 58.5 | 14.6 | 2.2 | 24.7 | ||

| Neutral or disagree | 36.9 | 4.5 | 25.3 | 36.9 | 33.3 | 74.9 | 74.0 | 9.0 | 0.8 | 16.3 | ||

| Initiate appropriate screening or diagnostic work-up to detect recurrent cancer: |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Agree breast and/or colon | 77.7 | 12.3 | 34.0 | 20.1 | 33.6 | 39.4 | 61.6 | 12.7 | 1.6 | 24.0 | ||

| Neutral or disagree | 22.3 | 7.3 | 19.0 | 42.4 | 31.2 | 60.6 | 75.9 | 8.8 | 0.8 | 14.5 | ||

| PCPs should have primary responsibility for cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors |

<0.0001 | 0.0048 | ||||||||||

| Agree breast and/or colon | 34.4 | 20.3 | 34.5 | 12.3 | 32.8 | 14.5 | 57.3 | 12.6 | 5.7 | 24.4 | ||

| Neutral or disagree | 65.6 | 6.4 | 28.3 | 32.0 | 33.3 | 85.5 | 72.6 | 10.0 | 0.3 | 17.2 | ||

| Prefers a shared model of survivorship care |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 12.0 | 41.2 | 16.6 | 30.3 | 18.1 | 54.5 | 24.7 | 1.6 | 19.2 | ||

| No | 58 | 10.6 | 22.1 | 31.6 | 35.7 | 81.9 | 73.7 | 7.1 | 1.0 | 18.1 | ||

| PCP receives/Oncologist provides a summary with detailed cancer treatment information from the oncologist/to the PCP: |

0.0075 | 0.0073 | ||||||||||

| Always/Almost always | 35.0 | 10.1 | 31.4 | 24.8 | 33.7 | 49.5 | 74.2 | 9.6 | 1.1 | 15.1 | ||

| Often | 29.3 | 9.8 | 35.7 | 24.1 | 30.5 | 26.4 | 66.5 | 12.2 | 1.8 | 19.5 | ||

| Sometimes | 21.3 | 12.7 | 31.1 | 18.1 | 38.2 | 15.6 | 66.3 | 10.6 | 0.0 | 23.0 | ||

| Rarely/Never | 14.5 | 14.3 | 16.6 | 37.3 | 31.9 | 8.5 | 64.1 | 9.3 | 1.0 | 25.7 | ||

| PCP receives/Oncologist provides a follow-up care plan with recommendations for future care and surveillance cancer treatment information from the oncologist/to the PCP: |

0.2074 | 0.0008 | ||||||||||

| Always/Almost always | 16.0 | 9.5 | 32.0 | 28.4 | 30.1 | 25.6 | 76.4 | 10.2 | 0.8 | 12.7 | ||

| Often | 20.8 | 11.0 | 34.3 | 22.9 | 31.8 | 28.3 | 68.3 | 11.8 | 2.6 | 17.3 | ||

| Sometimes | 25.8 | 10.9 | 35.5 | 22.7 | 30.9 | 25.2 | 73.3 | 9.6 | 0.4 | 16.7 | ||

| Rarely/Never | 37.3 | 12.2 | 24.3 | 26.1 | 37.4 | 20.9 | 61.1 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 29.2 | ||

| Communicates with patient’s other physicians about who will follow the patient for cancer: |

0.2807 | 0.0009 | ||||||||||

| Always/Almost always | 17.0 | 12.5 | 28.9 | 24.7 | 33.8 | 40.1 | 76.4 | 7.3 | 1.1 | 15.2 | ||

| Often | 25.1 | 11.7 | 32.4 | 23.9 | 32.0 | 32.5 | 66.1 | 13.3 | 1.5 | 19.1 | ||

| Sometimes | 26.0 | 11.8 | 34.8 | 19.3 | 34.1 | 17.7 | 65.2 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 21.2 | ||

| Rarely/Never | 31.9 | 8.9 | 26.2 | 30.9 | 34.1 | 9.7 | 67.3 | 6.6 | 1.8 | 24.3 | ||

Data source: Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS)

Predominantly provides: “I provide myself” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles Predominantly co-manages: “I share responsibility for or co-manage this care” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles

Predominantly not directly involved: “Another specialist orders or provides”/ “I am not involved” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles

Other: no dominant pattern for the 10 breast and colon cancer care roles or dominant role patterns differ for breast and colon cancer care

Total % represents the column percentage for each belief, preference, and care coordination variable.

PCPs who reported that they always/almost always (35%), often (29%), or sometimes (21%) receive treatment summaries from oncologists were more likely to co-manage as their dominant role pattern (Table 3). In contrast, receipt of a follow-up care plan from the oncologist (16% always/almost always; 21% often; 26% sometimes) and communicating with the patient’s other physicians about who will follow the patient for their cancer (17% always/almost always; 25% often; 26% sometimes) were not associated with PCPs’ role patterns. Among oncologists, the care coordination items were not strongly associated with co-management as a dominant role pattern.

Factors Associated with Physicians’ Cancer-Related Follow-up Care Role Patterns

Factors associated with PCPs’ dominant role patterns in adjusted analyses are shown in Table 4. Compared with general internists, obstetrician/gynecologists were less likely to directly provide or co-manage follow-up care as their dominant pattern. In contrast, PCPs who had received training in the late or long-term effects of cancer, saw a higher volume of breast and colon cancer patients in the past year, believe that PCPs should have primary responsibility for survivors’ cancer-related follow-up care, or prefer a shared survivorship care model were more likely to directly provide or co-manage as their dominant pattern. PCPs located in the West Census region were more likely to directly provide follow-up care. Those believing PCPs have the skills to initiate work-up to detect recurrent cancer or who indicated that they always, often, or sometimes receive a written treatment summary from oncologists were more likely to co-manage.

Table 4.

Polytomous logistic regression model of factors associated with primary care physicians’ role patterns1 in the cancer-related follow-up care of breast and colon cancer survivors

| Provides vs. Not directly involved |

Co-manages vs. Not directly involved |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | (95% CI) | O.R. | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Physician characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gender: | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.61 | (0.34-1.11) | 0.85 | (0.51-1.41) |

|

| ||||

| Primary care specialty: | ||||

| General internal medicine | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Family medicine | 0.74 | (0.42-1.31) | 0.74 | (0.44-1.24) |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 0.16 | (0.06-0.43) | 0.17 | (0.08-0.35) |

|

| ||||

| Has received training in late/long-term effects of cancer or its treatment: |

||||

| Yes | 2.96 | (1.55-5.63) | 2.27 | (1.43-3.59) |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Practice setting characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Census region: | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Midwest | 1.67 | (0.70-4.00) | 1.00 | (0.53-1.89) |

| West | 2.97 | (1.32-6.66) | 1.39 | (0.73-2.64) |

| South | 1.44 | (0.66-3.10) | 1.06 | (0.56-2.00) |

|

| ||||

| Type of medical record system: | ||||

| Full EMR | 1.14 | (0.52-2.53) | 1.09 | (0.58-2.04) |

| Partial EMR | 2.03 | (0.88-4.70) | 1.14 | (0.52-2.48) |

| Transitioning from paper to EMR | 0.73 | (0.33-1.59) | 0.85 | (0.46-1.59) |

| Paper charts | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Physician practice style | ||||

|

| ||||

| # of breast and colon cancer patients seen in past year: (quartiles) |

||||

| 1st quartile | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2nd quartile | 0.95 | (0.42-2.13) | 0.93 | (0.51-1.67) |

| 3rd quartile | 1.87 | (0.82-4.29) | 1.53 | (0.79-2.93) |

| 4th quartile | 2.87 | (1.42-5.81) | 2.27 | (1.17-4.41) |

|

| ||||

| Physician beliefs and preferences | ||||

|

| ||||

| PCPs have the skills to provide follow-up care for cancer or its treatment effects: |

||||

| Agree breast and/or colon | 2.20 | (0.92-5.26) | 1.25 | (0.70-2.22) |

| Neutral or disagree | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| PCPs have the skills to initiate appropriate screening or diagnostic work-up to detect recurrent cancer: |

||||

| Agree breast and/or colon | 1.16 | (0.49-2.75) | 2.28 | (1.26-4.12) |

| Neutral or disagree | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| PCPs should have primary responsibility for cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors: |

5.00 | (2.99-8.37) | 1.98 | (1.20-3.26) |

| Agree breast and/or colon | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Neutral or disagree | ||||

|

| ||||

| Prefers a shared model of survivorship care: | ||||

| Yes | 2.00 | (1.14-3.52) | 3.37 | (2.07-5.48) |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Care coordination | ||||

|

| ||||

| Receives a summary with detailed cancer treatment information from the oncologist: |

||||

| Always/almost always/often | 0.87 | (0.41-1.85) | 2.59 | (1.05-6.38) |

| Sometimes | 1.40 | (0.61-3.20) | 3.92 | (1.67-9.20) |

| Rarely/Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Receives a follow-up care plan with recommendations for future care and surveillance from the oncologist: |

||||

| Always/almost always/often | 0.73 | (0.31-1.71) | 0.93 | (0.50-1.75) |

| Sometimes | 1.13 | (0.51-2.50) | 1.47 | (0.82-2.65) |

| Rarely/Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Data source: Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS)

P<0.05 (bolded)

Predominantly provides: “I provide myself” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles

Predominantly co-manages: “I share responsibility for or co-manage this care” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles

Predominantly not directly involved: “Another specialist orders or provides”/“I am not involved” for the majority of breast and colon cancer care roles

Among oncologists, few characteristics were associated with co-management versus directly providing follow-up care as dominant role patterns (data not shown). Those indicating that they preferred a shared model of survivorship care were more likely to co-manage compared with those preferring other care models (OR=4.23; 95% CI: 2.74-6.52).

DISCUSSION

We found that a majority of PCPs perceive themselves as having an active role in the cancer-related follow-up care of survivors, most often in a co-management capacity with an oncologist. In contrast, most oncologists perceive that they directly provide cancer-related follow-up care themselves without much involvement from PCPs or other providers, a finding that parallels recent work documenting medical oncologists’ limited engagement in co-managing breast cancer care.19 In our study, discrepant PCP and oncologist reports of co-management—or sharing responsibility for survivors’ cancer-related follow-up care—are noteworthy, particularly in light of growing calls for adoption of shared-care models to optimally meet cancer survivors’ health care needs.2; 20-24

What explains, and what are possible consequences of, the apparent mismatch between PCPs’ and oncologists’ involvement in cancer-related follow-up care? One potential explanation is that PCPs are engaged in cancer-related follow-up care without oncologists’ awareness. If true, this suggests the possibility of duplication of effort between PCPs and oncologists that could lead to overuse of surveillance testing and other follow-up care. Prior work has shown both underuse and overuse of surveillance testing among cancer survivors8; 25-27 and that survivors continue to see several different providers many years after diagnosis.28 While information technology such as electronic health records (EHRs) has the potential to facilitate delivery of efficient, coordinated, and appropriate follow-up care, this potential may not be fully realized, as many providers still use paper charts—40% of PCPs and 22% of oncologists in our 2009 survey—or have EHR systems with limited interoperability, which is often the case in small practices.29-30

This study also identified several facilitators of PCP co-management of cancer-related follow-up care. We showed that the care coordination activities of oncologists, particularly provision of detailed cancer treatment summaries to PCPs, were associated with PCPs’ co-management. Previous research has documented the value that patients place on effective communication and coordination among their providers.31-33 Our results indicate, however, that not all oncologists consistently engage in care coordination with PCPs. For example, 24% said they did not routinely provide treatment summaries to PCPs, and 45% did not routinely provide follow-up care plans documenting recommendations for future care and surveillance. Furthermore, 27% said they did not routinely communicate with their patients’ other physicians about which physician would provide cancer-related follow-up care. Oncologists’ perceptions of treatment summaries as an uncompensated and time-consuming burden, and their reluctance to discharge their patients to PCPs for survivorship care, have been identified as key barriers to the effective coordination of survivor care.34-35

Other facilitators of PCP co-management of cancer-related follow-up care included receiving training in the late or long-term effects of cancer or its treatment, seeing a higher volume of cancer patients, holding favorable attitudes about PCP involvement in follow-up care, and preferring a shared model of survivorship care. Although 65% of PCPs in our study reported receipt of training in cancer late or long-term effects, only 4% considered this as being “in detail”. In contrast, 93% of oncologists indicated that they were trained in this aspect of survivors’ care “in detail” (36%) or “somewhat” (57%). Furthermore, PCP attitudes were more favorable about their skills in providing follow-up care (≥62% in agreement) than they were regarding assuming primary responsibility for cancer-related follow-up care (34% in agreement). Finally, less than half of PCPs preferred a shared-care model with oncologists. These findings suggest several potential points of intervention for enhancing PCPs’ knowledge about and skills in caring for survivors.

Our study has limitations. It is based on physician self-reports of their involvement in cancer-related follow-up care. The survey asked about care of patients with early-stage breast and colon cancer; physicians’ practices might differ for later-stage disease, or for other cancer types. While our data are nationally-representative, we lacked information that would have allowed closer examination of urban/rural and other practice location differences in physicians’ follow-up care involvement. We did not ask about the composition of the care team that may be managing survivors’ follow-up care, or assess physicians’ views on which provider type should assume lead responsibility for coordinating this care. We also did not ascertain the extent to which respondents engaged in providing survivorship care within an integrated vs. decentralized delivery environment. Beyond a single item asking about the type of medical record system in the physician’s practice, we were unable to explore other practice-level systems features— particularly information technologies22—that may facilitate communication and care coordination across providers. Finally, items asking about provision of treatment summaries and follow-up care plans may not have been uniformly interpreted and physicians’ responses to these items may be susceptible to social desirability bias. All of these are important topics for future research.

Monitoring for cancer recurrence and new primary cancers as well as evaluating and managing late or long-term effects of cancer treatment are critical components of survivors’ cancer-related follow-up care. Our study of U.S. PCPs and oncologists provides an important foundation for understanding physician roles in providing this care. The growing survivor population and projected shortages of PCPs and oncologists heighten the need for more efficient and effective approaches to survivorship care delivery. Although our study documents the active engagement of both provider types in cancer-related follow-up care, discrepancies in PCPs’ and oncologists’ reports of sharing responsibility for this care reinforce concerns that provider roles in survivorship care are often unclear.2 Improved communication and coordination between PCPs and oncologists is required to ensure that the ongoing, often complex, health care needs of cancer survivors are met.

Figure 1B.

Involvement of primary care physicians (PCPs) and medical oncologists in cancer-related follow-up care for colon cancer survivors

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute or the American Cancer Society.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Funding for the Survey of Physicians’ Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS) was provided by the National Cancer Institute (contract number HSN261200700068C) and the American Cancer Society through its intramural research funds.

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None.

This study was presented in part at the Cancer and Primary Care Research International Network (Ca-PRI) annual meeting in Noordwijkerhout, the Netherlands, on May 26, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patients to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press; Washington: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5091–5097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology®. Breast Cancer Guidelines. 2008 Version 2.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology®. Colon Cancer Guidelines. 2010 Version 2.2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Factors related to underuse of surveillance mammography among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(1):85–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Surveillance testing among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1074–1081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan NF, Ward A, Watson E, Austoker J, Rose PW. Long-term survivors of adult cancers and uptake of primary health services: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(2):195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder CF, Earle CC, Herbert RJ, Neville BA, Blackford AL, Frick KD. Preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1073–1079. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder CF, Earle CC, Herbert RJ, Neville BA, Blackford AL, Frick KD. Trends in follow-up and preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):254–259. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haggstrom DA, Arora NK, Helft P, Clayman ML, Oakley-Given I. Follow-up care delivery among colorectal cancer survivors most often seen by primary and subspecialty care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S472–S479. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Kantsiper ME, et al. Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: changes from 1998-2002. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1054–1061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):469–474. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(2):79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodenheimer T. Primary care: will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose DE, Tisnado DM, Tao ML, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and patient outcomes associated with physician co-management: findings from the Los Angeles Women’s Health Study. Health Serv Res. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01359.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganz PA, Hahn EE. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(5):759–767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunfeld E. Primary care physicians and oncologists are players on the same team. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(14):2246–2247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen HJ. A model for the shared care of elderly patients with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(Suppl 2):S300–S302. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz PA. Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2009;36(4):721–741. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Guidice ME, Moineddin R. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(4):174–181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richert-Boe KE. Heterogeneity of cancer surveillance practices among medical oncologists in Washington and Oregon. Cancer. 1995;75(10):2605–2612. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2605::aid-cncr2820751031>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field TS, Doubeni C, Fox MP, et al. Under utilization of surveillance mammography among older breast cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(2):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack LA, Adamache W, Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Richardson LC. Care of long-term cancer survivors: physicians seen by Medicare enrollees surviving longer than 5 years. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5284–5295. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sada YH, Street RL, Singh H, Shada RE, Naik AD. Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: a qualitative study. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(4):259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. New Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6576–6586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Arora NK, et al. Patients’ experiences with care for lung cancer and colorectal cancer: findings from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4154–4161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Earle CC. Associations among cancer survivorship discussion, patient and physician expectations, and receipt of follow-up care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2577–2583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–2273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S459–S466. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]