Abstract

Background

A number of changes have been proposed and investigated in the criteria for substance use disorders in DSM-5. However, although clinical utility of DSM-5 is a high priority, relatively little of the empirical evidence supporting the changes was obtained from samples of substance abuse patients.

Methods

Proposed changes were examined in 663 patients in treatment for substance use disorders, evaluated by experienced clinicians using the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM). Factor and item response theory analysis was used to investigate the dimensionality and psychometric properties of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin abuse and dependence criteria, and craving.

Results

The seven dependence criteria, three of the abuse criteria (hazardous use; social/interpersonal problems related to use; neglect of roles to use), and craving form a unidimensional latent trait for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin. Craving did not add significantly to the total information offered by the dependence criteria, but adding the three abuse criteria and craving together did significantly increase total information for the criteria sets associated with alcohol, cannabis and heroin.

Conclusion

Among adult patients in treatment for substance disorders, the alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin criteria for dependence, abuse (with the exception of legal problems), and craving measure a single underlying dimension. Results support the proposal to combine abuse and dependence into a single diagnosis in the DSM-5, omitting legal problems. Mixed support was provided for the addition of craving as a new criterion, warranting future studies of this important construct in substance use disorders.

Keywords: Item response theory, Substance abuse, Substance dependence, Craving, DSM-IV, DSM-5

1. Introduction

Changes proposed to the substance use disorders (SUD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association) include: (1) dropping the legal problems criterion, an abuse criterion in DSM-IV; (2) adding craving as a new criterion; and (3) combining the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria, the three remaining abuse criteria (hazardous use; social/interpersonal problems related to use; neglect of roles to use) and craving into criteria for a single disorder.

Justification for dropping legal problems included low prevalence in adults (Compton et al., 2009; Gillespie et al., 2007; Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007; Shmulewitz et al., 2010) and adolescents (Piontek et al., 2011) in the general population, low discrimination in adolescents (Hartman et al., 2008), poor fit with other criteria (Saha et al., 2006; Teesson et al., 2002) and little added SUD information (Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007; Martin et al., 2006; Shmulewitz et al., 2010). Theoretical justifications for adding craving include the view of some that it is central to SUD (Goldstein and Volkow, 2002; O’Brien, 2005) and that it can cue drug self-administration leading to relapse (Sinha et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2003). Craving has been studied in animal (Weiss, 2005) and human laboratory models (Sinha, 2011). The consistency of DSM-5 with ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) would be improved byadding craving, whose neural basis makes it an inviting pharmacotherapy development target (Kalivas and O’Brien, 2008).

Justification for combining the dependence and three abuse criteria is found in many studies showing undimensionality of the dependence and three abuse criteria for alcohol and drug use disorders. These studies largely used item response theory (IRT) analyses, although other methods were also used (Beseler and Hasin, 2010; Hasin and Beseler, 2009; Hasin et al., 2006c). Participants in these studies were adults in the general population (Beseler and Hasin, 2010; Compton et al., 2009; Hasin et al., 2006c; Kahler and Strong, 2006; Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007; Proudfoot et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006; Shmulewitz et al., 2010; Teesson et al., 2002) with additional samples of students (Beseler et al., 2010) adolescents (Gelhorn et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2006; Perron et al., 2010; Piontek et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2009b) and emergency room patients (Borges et al., 2010). Among studies that included craving, latent variable modeling showed that craving fit well on a unidimensional latent variable with other DSM-IV alcohol criteria in the U.S. (Keyes et al., 2010) and Australian (Mewton et al., 2011) general population and also in emergency room patients in several countries (Cherpitel et al., 2010), but was redundant with other SUD criteria, thus not adding much information. In addition, in the U.S. general population, adding craving increased DSM-5 SUD prevalence by <.05% (Agrawal et al., 2011) thus not casting a wider diagnostic net.

These studies consistently support a unidimensional model, but their applicability to clinical populations cannot be assumed because the criteria are likely to be distributed differently in patient and non-patient populations. Earlier studies in clinical samples addressed earlier nosologies (Bryant et al., 1991; Hasin et al., 1988; Kosten et al., 1987; Rounsaville et al., 1993) did not include complete (or any) coverage of DSM-IV abuse (Feingold and Rounsaville, 1995a; Kosten et al., 1987; Morgenstern et al., 1994; Rounsaville et al., 1993) or measured dependence criteria with a diagnostic instrument and abuse in a different manner (Feingold and Rounsaville, 1995b). Several studies mixed patients and non-patients (Bryant et al., 1991; Feingold and Rounsaville, 1995a,b; Nelson et al., 1999; Rounsaville et al., 1993). Varying analytic strategies across these studies reflected the evolution in latent variable methodology during this period. These studies were inconsistent on the number and content of factors obtained, and do not directly answer the questions at hand for the proposed DSM-5 SUD changes.

More recent studies among patients in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN) showed good evidence for unidimensionalty and little evidence of differential item functioning by demographic characteristics for DSM-IV alcohol, marijuana, cocaine and opioid dependence (Wu et al., 2009a), but did not include abuse. Other IRT analyses of addiction scales in adult clinical (Kahler et al., 2003; Morey and Hopwood, 2009), twin (Krueger et al., 2004) or mixed convenience samples (Kirisci et al., 2002) did not directly address DSM-5 because the scales included many extraneous items. Only two clinical studies directly addressed the proposed DSM-5 combination of abuse and dependence criteria. Among 372 U.S. northeastern substance abuse patients (Langenbucher et al., 2004), abuse and dependence criteria were unidimensional for alcohol, cannabis and cocaine, but only after removing legal problems and tolerance. Among 1511 opioid-dependent Australian patients, a two-class, one-factor model for opioid abuse and dependence criteria that included legal problems was suggested (Shand et al., 2011), although a well-fitting unidimensional model from these data with only half the parameters appeared more parsimonious (Hasin, 2011). These two studies offered important information on unidimensionality. However, neither study addressed craving, differential item functioning (also known as measurement invariance, i.e., whether the criteria function differently according to characteristics of respondents such as gender or age), or whether abuse criteria and craving added significant information to the existing dependence criteria, which have extensive reliability and validity evidence (Hasin et al., 2006a).

Since clinical utility is the highest priority in revising diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association), understanding the proposed changes in clinical samples is important. We therefore examined the proposed changes to DSM-5 SUD criteria among adult patients in substance abuse treatment settings. In this study, clinicians administered a highly reliable semi-structured diagnostic interview (Hasin et al., 2006b) and four substances were addressed: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin. We examined these questions: (1) could the unidimensionality of the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria be confirmed in this sample? (2) Did evidence support adding craving and dropping legal problems? (3) Was differential item functioning found by patient demographic or clinical characteristics? (4) Did adding abuse criteria and craving add significantly to the information offered by the dependence criteria alone?

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and procedures

The sample included 663 patients age ≥18 years recruited from an inpatient community psychiatric hospital treating co-occurring substance and psychiatric disorders (N = 349), a methadone clinic (N = 270) and an outpatient counseling program (N = 44). To be eligible, patients must have used alcohol, cocaine or heroin within the prior 30 days (or the 30 days prior to admission, if inpatient), and to have completed detoxification if necessary. At each treatment site, clinical staff identified eligible, sequentially admitted patients and obtained their agreement to meet with research staff, who explained the study. Respondents who gave consent then participated in a baseline interview. The research protocol, including informed consent procedures, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York State Psychiatric Institute. Study procedures were described previously (Aharonovich et al., 2002, 2005; Hasin et al., 2002; Nunes et al., 2006). For the present study, patients were considered current users of alcohol (N = 534), cannabis (N = 340), cocaine (N = 483) or heroin (N = 364) if they used the substance during the prior 12 months. Patients’ median age was 37 years, 64.0% were male, 52.3% white, 25.3% Black, 21.1% Hispanic and 1.2% other, and 25.5% had not completed high school.

2.2. Measures

The Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM) is a highly reliable (Hasin et al., 2006b) and valid (Torrens et al., 2004) semi-structured clinician-administered interview designed to evaluate current and lifetime DSM-IV disorders. The PRISM was administered by clinicians who received extensive, structured training and supervision, as described elsewhere (Hasin et al., 2002, 2006b). PRISM interviewers were clinicians who had at least a master’s degree and were experienced in treating patients with substance use and psychiatric disorders. The PRISM obtained detailed information on the 11 abuse and dependence criteria for substance-specific DSM-IV SUDs, as well as craving (i.e., strong desire or urge to use the substance); we analysed these using the prior-12-month timeframe. The PRISM also assesses mood, anxiety, and two personality disorders (antisocial and borderline) according to DSM-IV criteria (Hasin et al., 2002, 2006b). For differential item functioning analyses, we created three combined-disorder variables: mood disorder (major depressive disorder, bipolar I or 2, N = 129); anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety, panic with/without agoraphobia, social and specific phobia, N = 74) and personality disorder (lifetime antisocial and borderline, N = 167). Mood and anxiety disorders were considered positive if respondents met criteria in the prior 12 months, thus overlapping with the timeframe for the substance disorder criteria.

2.3. Statistical analysis

2.3.1. Assessing dimensionality

We investigated whether abuse and dependence criteria follow a single dimension or are better modeled as two separate dimensions several ways. Following conventional methods, we first examined the eigenvalues obtained from the tetrachoric correlations of all 11 criteria (10 criteria for cannabis). A single dimension is supported with one large eigenvalue and a large ratio of the first to second eigenvalue (Hutten, 1980; Lord, 1980). Second, we fit a 2-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model with abuse and dependence criteria on separate factors and estimated the correlation between them. Correlations between factors exceeding 0.85 suggest combining them into a single dimension (Brown, 2006). Third, we considered a useful complement to traditional dimensionality analyses called the confirmatory bifactor model which examines the evidence for items as measures of a single overall “general” factor vs. subgroups of items forming subscalesmeasuring distinct “group” factors (Reise et al., 2007). Specifically, the bifactor model assumes each criterion loads on two factors, one overall “general” factor (shared by all criteria) and another “group” factor shared only by those other criteria potentially measuring the same (sub) construct. The model estimates how strongly the criteria load on the overall general disorder factor versus the specific “group” factors obtained after controlling for the overall general factor. All dependence, abuse, and craving criteria were allowed to load on the general factor. In addition, the dependence and abuse criteria were respectively allowed to load on their own “group” factor, while the cravings criterion was free to load on both the dependence and abuse factors. A single dimension is supported by strong loadings (>0.40) for all criteria on the general factor, with smaller loadings on the group factors (larger loadings on the latter indicating criteria with variability not fully captured by the general factor). Finally, a one-factor CFA model was fit to all criteria (including cravings) and then fit again without including legal problems. Evaluation of model fit for the one-factor model was based on the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the comparative fit index (CFI). For RMSEA, smaller values indicate better fit, with a commonly accepted threshold of <.05. Values of CFI above 0.90 and 0.95 are generally accepted as reflecting adequate and good fit, respectively (Hu and Bentler, 1999). All analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.0.

2.3.2. Item response theory (IRT) models and differential item functioning (DIF)

After confirming unidimensionality, we fit the 2-parameter logistic item response theory (IRT) model to all of the abuse and dependence criteria as well as craving (seeEmbretson and Reise (2000)) for an approachable textbook of IRT methods; the introduction of Langenbucher et al. (2004) for abbreviated summary of these methods, and Shmulewitz et al. (2011) for a glossary of IRT terminology). Because of the low prevalence and likely deletion of legal problems, we also fit the IRT model without legal problems. Criteria were also ranked by their estimated severity. We generated item characteristic curves (ICC) to display the estimated probability of each criterion across the underlying continuum. In the ICC, the severity parameter is the point on the x-axis where the probability of endorsing a criterion is 0.5, and discrimination is the slope of the curve at that point. Steeper slopes indicate greater discrimination. All IRT estimates were obtained using marginal maximum likelihood in the latent trait modeling (“ltm”) package in R2.10.1 (Rizopoulos, 2006).

Chi-square difference tests were used to test for overall DIF (another term for measurement invariance) of all the dependence and abuse items, excluding legal problems and including craving. We first constructed a model where all factor loadings and thresholds were allowed to vary across covariate categories (baseline model). We then compared the baseline model to a model where item thresholds and factor loadings were set equal across covariate categories (constrained model). If the chi-square difference test reaches significance (p < 0.05), then measurement non-invariance exists and the items behave differently in the two groups. DIF covariates included gender, age (≤ or >the median, 37 years), race/ethnicity (white vs. non-white), and the three combined psychiatric disorder variables (mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders). Since we analysed DIF using six covariates, we used Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, considering a result significant at p ≤ 0.008. When significant overall DIF was identified, we explored which items contributed to DIF by identifying anchor items whose thresholds or factor loadings did not significantly differ by group in order to set the metric between groups and allow individual testing for DIF in the remaining items. We next tested each item for DIF by constraining each individual item to be equal across groups. Using the chi-square statistic, we compared each constrained model to the baseline unconstrained model.

2.3.3. Total information

We generated total information curves (TIC) for different criterion sets to show their ability to discriminate individuals along the latent trait severity spectrum (Muthen and Muthen, 1998-2007). Two or more TICs are often visually compared to see whether adding criteria to an initial set adds information. We compared four curves for each substance, representing four sets of criteria: dependence only; dependence and abuse; dependence and craving; and dependence, abuse and craving. A summary of the overall total information provided by each criterion set was indicated by the total information area index (TIA) (De Ayala, 2009), which equals the area under the TIC and is calculated by summing all the respective discrimination parameter estimates (De Ayala, 2009). TIA confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the delta method (R code available at http://www.columbia.edu/~mmw2177/irtprog.html). Non-overlapping 95% CIs for the TIAs indicate that the addition of more criteria provide significantly more information.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of DSM-IV criteria

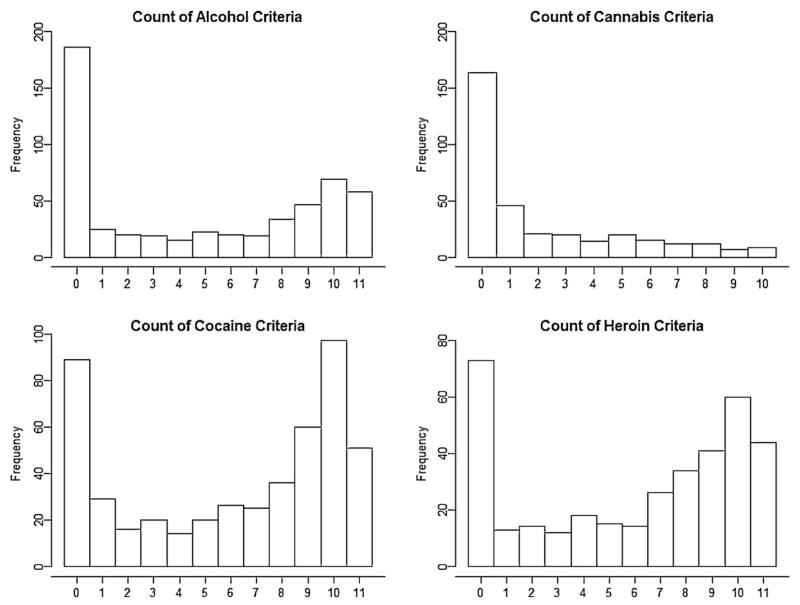

Except for legal problems, which was rare, the prevalence of all DSM-IV criteria and craving was high (Table 1) ranging from 27% to 52% for alcohol, 12% to 29% for cannabis, 29% to 73% for cocaine, and 30% to 73% for heroin. Hazardous use, while endorsed commonly across substances (27-30%), was among the low-prevalence criteria. The prevalence of craving was similar in magnitude to DSM-IV dependence criteria. Except for cannabis, the total number of criteria per patient for each substance was distributed bi-modally: one mode with no criteria and the other mode at 9 or more criteria (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of DSM-IV criteria and craving among patients who used alcohol, cocaine, heroin and cannabis in the last 12 months (N =663).

| Characteristics | % among past year users |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol (N =534) | Cannabis (N=340) | Cocaine (N=483) | Heroin (N=364) | |

| Currenta DSM-IV criteria | ||||

| Tolerance | 48.31 | 20.29 | 50.72 | 64.01 |

| Withdrawal | 37.64 | N/A | 53.21 | 60.16 |

| Larger/longer | 51.31 | 22.94 | 66.46 | 63.74 |

| Tried to cut down or stop | 51.69 | 25.29 | 72.88 | 73.35 |

| Spend time using | 41.39 | 25.00 | 57.35 | 73.35 |

| Reduce activities to use | 46.25 | 20.59 | 61.70 | 56.04 |

| Use despite physical problems | 45.69 | 18.24 | 62.73 | 53.85 |

| Fail to fulfill role obligations | 40.26 | 14.71 | 48.86 | 42.86 |

| Hazardous use | 27.15 | 29.41 | 28.78 | 30.22 |

| Legal problems | 05.24 | 00.29 | 06.00 | 07.97 |

| Use despite social problems | 41.39 | 11.76 | 45.96 | 39.84 |

| Craving (strong desire) | 49.81 | 25.59 | 65.63 | 65.66 |

Current: reported occurrence of the criterion in the last 12 months.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of total counts of dependence and abuse criteria excluding legal problems but including craving.

3.2. Unidimensionality of DSM-IV dependence and abuse criteria and craving

For all substances, the ratio of first to second eigenvalues for the dependence and abuse criteria set was very large (range 6.9-10.9), indicating a highly dominant single dimension explaining the variability in the criteria. The 2-factor CFA model found high correlation between factors measured separately by dependence and abuse criteria (>0.97), not supporting them as separate dimensions. The bi-factor CFA model results (Table 2) provide information on the relationship of each criterion with a single “general factor” compared to its unique relationship with dependence or abuse group dimensions. All alcohol, cocaine and heroin criteria show a strong relationship (>0.50) with the general factor and with little exception the criteria load much more strongly on the general factor than on the respective group factors. Of particular note, the cravings criterion loads very highly on the overall general factor (>0.90) with near zero correlations related to the dependence and abuse group factors. Convergence problems due to only one individual with legal problems for cannabis required legal problems to be dropped from the bifactor model for cannabis. Hazardous use shows a strong negative loading on the abuse group factor for cocaine, and shows factor loading > 0.40 for alcohol, cannabis and heroin on the abuse group factor after controlling for the general factor. This implies that while hazardous use shares substantial common variance with the general factor, it also captures another dimension. For each substance, good empirical fit of a single 1-factor model underlying all the abuse and dependence criteria was found whether the criterion for legal problems was included or not (bottom section, Table 2). Finally, when craving was also included, eigenvalue results were similar and 1-factor CFA fit statistics were nearly unchanged.

Table 2.

Dimensionality assessments of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria and craving.

| Bi-factor CFAa | Alcohol (N = 534) |

Cannabis (N=340) |

Cocaine (N =483) |

Heroin (N=364) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized factor loadings | General factor |

Dependence factor |

Abuse factor |

General factor |

Dependence factor |

Abuse factor |

General factor |

Dependence factor |

Abuse factor |

General factor |

Dependence factor |

Abuse factor |

| Tolerance | 0.882 | 0.378 | - | 0.838 | 0.142 | - | 0.752 | 0.363 | - | 0.896 | 0.341 | - |

| Withdrawal | 0.930 | 0.256 | - | N/A | N/A | - | 0.819 | 0.373 | - | 0.924 | 0.339 | - |

| Larger/longer | 0.943 | 0.124 | - | 0.844 | 0.373 | - | 0.974 | 0.111 | - | 0.945 | −0.128 | - |

| Quit/control | 0.940 | −0.026 | - | 0.745 | 0.577 | - | 0.880 | 0.063 | - | 0.923 | 0.067 | - |

| Time spent | 0.913 | 0.326 | - | 0.901 | 0.132 | - | 0.887 | 0.451 | - | 0.935 | 0.266 | - |

| Activity given up | 0.971 | −0.032 | - | 0.923 | 0.135 | - | 0.935 | 0.227 | - | 0.917 | 0.138 | - |

| Physical/pschological | 0.943 | 0.043 | - | 0.800 | 0.265 | 0.899 | 0.148 | - | 0.878 | −0.051 | - | |

| Neglect roles | 0.952 | - | 0.132 | 0.848 | - | 0.002 | 0.913 | - | 0.040 | 0.786 | - | 0.001 |

| Hazardous use | 0.654 | - | 0.443 | 0.687 | - | 0.170 | 0.556 | - | −0.771 | 0.567 | - | 0.717 |

| Legal probs | 0.504 | - | 0.394 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.575 | - | 0.328 | 0.669 | - | 0.022 |

| Social/interpersonal | 0.912 | - | 0.024 | 0.778 | - | 0.054 | 0.846 | - | 0.019 | 0.852 | - | 0.118 |

| Cravings | 0.924 | 0.046 | 0.038 | 0.914 | −0.043 | 0.140 | 0.902 | 0.089 | 0.016 | 0.943 | 0.099 | 0.057 |

| Fit statistics for one factor CFA | Legal problems |

Legal problems |

Legal problems |

Legal problems |

||||||||

| Included | Not included | Included | Not included | Included | Not included | Included | Not included | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| RMSEA | 0.043 | .052 | 0.036 | .030 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.038 | 0.040 | ||||

| CFI | 0.999 | .999 | 0.993 | .999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | ||||

Fitting the bifactor CFA model46 produced 3 uncorrelated factors: a general factor underlying all criteria and 2 additional group factors separately underlying the dependence and abuse criteria and both underlying cravings. In the bifactor model, these are called group factors because they represent shared variance among the dependence or abuse criteria after controlling for the general factor. Factor loadings indicate the correlation between the criteria and the general or group factors.

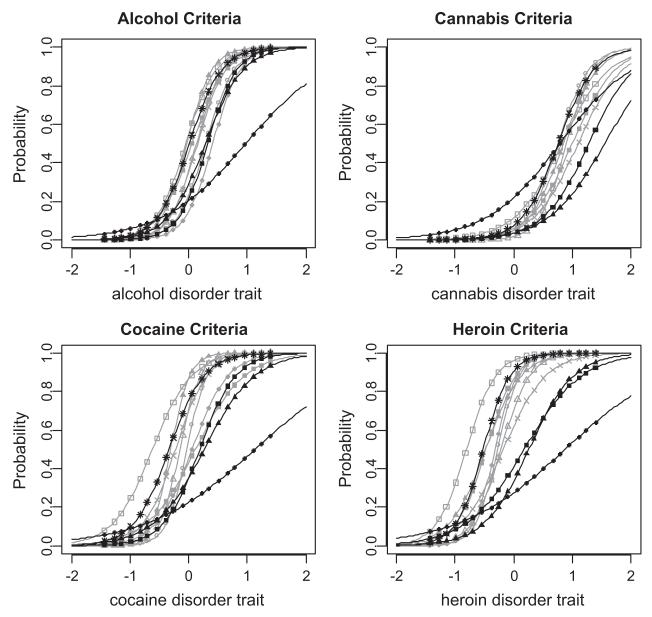

3.3. IRT results

Discrimination parameters across all substances ranged from 1.09 to 6.18 (Table 3; Fig. 2) indicating that each criterion had a strong ability to delineate individuals who were higher vs. lower on the latent trait. For example, the discrimination estimate of 3.13 for the abuse criterion of social/interpersonal problems indicates that an increase of one standard deviation on the latent trait results in a exp(3.13) = 22.9-fold increase in the odds of having the social/interpersonal abuse criterion. The severity parameters (Table 3; Fig. 2) calibrated to the observed sample, estimate the point above or below the mean of the latent trait (in standard deviations) at which 50% of the population will endorse that criterion. In this clinical sample, the severity estimates of ≤0.0 indicate that even patients below average on the latent trait have at least a 50% probability of experiencing the criterion.

Table 3.

Estimates of severity and discrimination from item response theory models of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin, excluding legal problems and including craving. Rank indicates lowest to highest severity across all criteria within substance.

| Alcohol |

Cannabis |

Cocaine |

Heroin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Severity | Discrimination | Rank | Severity | Discrimination | Rank | Severity | Discrimination | Rank | Severity | Discrimination | |

| Dependence criteria | ||||||||||||

| Quit/control | 1 | −0.05 | 3.87 | 4 | 0.82 | 2.49 | 1 | −0.62 | 2.99 | 1 | −0.81 | 3.98 |

| Larger/longer | 2 | −0.03 | 4.66 | 5 | 0.85 | 3.42 | 3 | −0.31 | 6.18 | 3 | −0.48 | 3.26 |

| Tolerance | 4 | 0.06 | 3.46 | 7 | 1.00 | 2.74 | 8 | 0.12 | 2.40 | 4 | −0.47 | 3.98 |

| Activity given up | 5 | 0.13 | 4.48 | 6 | 0.90 | 4.42 | 5 | −0.15 | 5.76 | 7 | −0.22 | 4.06 |

| Physical/psychological | 6 | 0.15 | 4.14 | 8 | 1.10 | 2.64 | 4 | −0.23 | 3.66 | 8 | −0.18 | 2.76 |

| Time spent | 8 | 0.29 | 4.11 | 2 | 0.76 | 3.81 | 6 | −0.03 | 5.78 | 6 | −0.28 | 5.39 |

| Withdrawal | 10 | 0.41 | 4.28 | NA | NA | 7 | 0.06 | 3.26 | 5 | −0.32 | 5.35 | |

| Abuse criteria | ||||||||||||

| Social/interpersonal | 7 | 0.29 | 3.13 | 10 | 1.55 | 2.1 | 10 | 0.27 | 2.32 | 10 | 0.26 | 2.63 |

| Neglect roles | 9 | 0.33 | 4.03 | 9 | 1.28 | 2.56 | 9 | 0.19 | 3.26 | 9 | 0.18 | 2.03 |

| Hazardous use | 11 | 0.97 | 1.40 | 3 | 0.79 | 1.61 | 11 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 11 | 0.87 | 1.11 |

| Additional criteria | ||||||||||||

| Craving | 3 | 0.01 | 3.66 | 1 | 0.76 | 3.28 | 2 | −0.34 | 3.34 | 2 | −0.52 | 4.35 |

Fig. 2.

Item characteristic curves models of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin dependence and abuse criteria (excluding legal problems) and including craving in a clinical sample.  tolerance;

tolerance;  withdrawal;

withdrawal;  larger/longer;

larger/longer;  quit/control;

quit/control;  time spent;

time spent;  activ given up;

activ given up;  physical/psych;

physical/psych;  neglect roles;

neglect roles;  hazardous use;

hazardous use;  social/interpers; -*- craving.

social/interpers; -*- craving.

Although the severity rankings of the criteria were not totally identical across substances, the abuse criteria tended to be more severe than the dependence criteria, while craving was among the least severe (indicating higher prevalence) across all four substances. To quantify the similarity in severity ranking of the criteria across substances, we computed Spearman correlations of the rankings. For alcohol, cocaine and heroin, these correlations were high (alcohol with cocaine, 0.80; alcohol with heroin, 0.78; cocaine with heroin, 0.82), indicating that the criteria had similar patterns of severity for these substances. In contrast, the corresponding correlations for cannabis were more modest (cannabis with alcohol, 0.21; cannabis with cocaine, 0.40; cannabis with heroin, 0.49),driven predominately by the “hazardous use” variable, which was less severe (i.e. more prevalent) for cannabis than in the other substances. In IRT models that included legal problems, the associated severity and discrimination parameters for legal problem were: alcohol (severity = 3.25, discr = 1.04); cannabis (severity = 8.9, discr = .68); cocaine (severity = 2.65, discr = 1.35); heroin (severity = 2.02, discr = 1.63).

For each substance, the legal severity parameter was large, constituting an outlier compared to the other criterion severity parameters. The legal discrimination parameter was the lowest for alcohol and cannabis and was also small for cocaine and heroin, although remaining larger than the discrimination for hazardous use.

3.4. Differential item functioning

We assessed DIF for three key demographic characteristics (sex, age and race/ethnicity) and three co-morbid disorders (anxiety, mood and personality) across four substances. We did not find consistent evidence for DIF across all these substances and characteristics. The AUD criteria showed no DIF in the six covariates examined. The cannabis criteria showed significant DIF only by age (χ2 = 29.9, p = 0.0009). All cannabis criteria except larger/longer and quit/control contributed to measurement non-invariance by age. The cocaine criteria also showed significant DIF by one characteristic: race/ethnicity (χ2 = 31.6, p = 0.0001). All cocaine criteria contributed to measurement non-invariance except craving. The heroin criteria showed significant DIF by one characteristic: having a mood disorder (χ2 = 44.4, p < 0.0001). All heroin criteria contributed to measurement non-invariance by whether patients had a mood disorder or not.

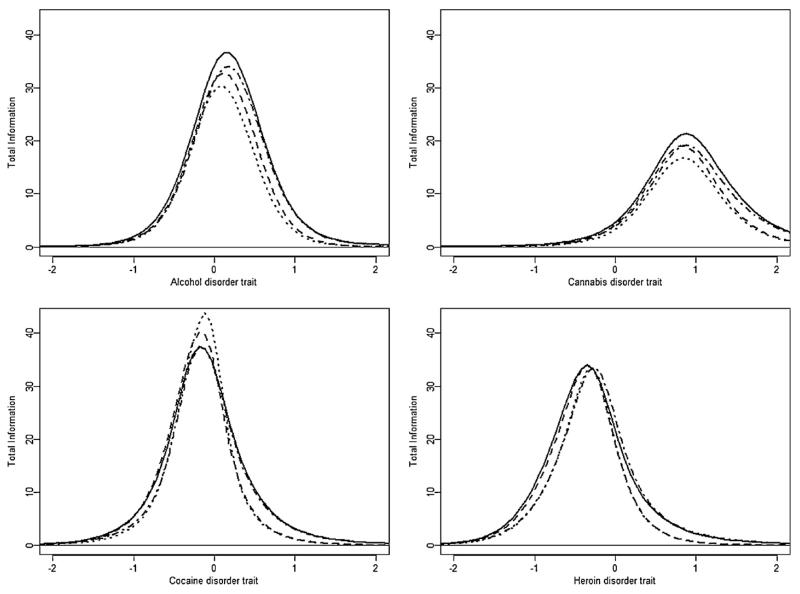

3.5. Total information

Total information curves are shown in Fig. 3. Both alcohol and cannabis show increased information across the entire trait as additional criteria are included, with cannabis criteria providing information on the higher end of the trait. For heroin, the region along the trait measured with high information widened as additional criteria were added. The total information for cocaine associated with just the dependence criteria exhibited a large spike near the mean (=0) of the trait and information decreases in that region as additional criteria were added. Total information area (TIA) and 95% CIs are shown in Table 4. Adding craving alone to the dependence criteria did not significantly increase the total information for any substance. Adding abuse to dependence criteria significantly increased total information for alcohol. The combined addition of abuse and craving significantly increased the information for alcohol, cannabis and heroin, but not for cocaine.

Fig. 3.

Total information curves for DSM-IV alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin dependence and abuse criteria and craving among past year users of that substance… . dependence only; - - dependence plus craving;. - . - dependence plus abuse; — dep/abuse plus craving.

Table 4.

Total information area (TIA) and 95% confidence intervals based on asymptotic standard errors for different criteria sets.

| DSM-IV substance criteria seta | No. of criteria in model | TIA | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol criteria | ||||

| Dependence | 7 | 30.73 | 27.71 | 33.74 |

| Dependence plus craving | 8 | 34.09 | 31.26 | 36.92 |

| Dependence plus abuse | 10 | 37.95 b | 35.09 | 40.80 |

| Dependence plus abuse plus craving | 11 | 41.23 b | 38.23 | 44.23 |

| Cannabis criteria | ||||

| Dependence | 6 | 20.07 | 16.15 | 24.00 |

| Dependence plus craving | 7 | 23.02 | 19.08 | 26.96 |

| Dependence plus abuse | 9 | 25.90 | 21.89 | 29.91 |

| Dependence plus abuse plus craving | 10 | 29.08 b | 25.16 | 33.00 |

| Cocaine criteria | ||||

| Dependence | 7 | 35.06 | 27.10 | 43.00 |

| Dependence plus craving | 8 | 36.30 | 31.55 | 41.05 |

| Dependence plus abuse | 10 | 37.66 | 33.58 | 41.75 |

| Dependence plus abuse plus craving | 11 | 40.04 | 36.10 | 43.98 |

| Heroin criteria | ||||

| Dependence | 7 | 30.66 | 27.01 | 34.32 |

| Dependence plus craving | 8 | 33.66 | 29.95 | 37.37 |

| Dependence plus abuse | 10 | 35.95 | 31.99 | 39.91 |

| Dependence plus abuse plus craving | 11 | 38.91 b | 35.08 | 42.74 |

Abuse criteria except for legal problems.

Bold indicates TIA is significantly different (p-value<.05) from the dependence-only criteria set TIA. Significance is determined by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to address a range of proposed DSM-5 changes in SUD criteria in a clinical sample. We examined dimensionality, criterion severity and discrimination, differential item functioning and total information for the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria and craving for four substances: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin. Consistent findings across analytic methods and substances supported combining DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria into criteria for a single disorder, because the criteria all were indicators of a unidimensional SUD latent trait. However, as was found in other samples, legal problems as a criterion occurred rarely and had low factor loadings and discrimination parameters across substances. Craving fit well within the unidimensional structure but did not add unique information to that already offered by the DSM-IV dependence criteria. Some differential item functioning was found by age, race/ethnicity and by psychiatric status, suggesting the need for further study to understand this better. Finally, compared to the DSM-IV dependence criteria, adding three DSM-IV abuse criteria (excluding legal) and craving significantly increased the total information available from the criteria sets for alcohol, cannabis and heroin, although not for cocaine.

The present findings on unidimensionality of the three abuse and seven dependence criteria are consistent with the many population-based adult studies in the U.S. (Agrawal and Lynskey, 2007; Agrawal et al., 2009; Beseler and Hasin, 2010; Compton et al., 2009; Hasin et al., 2006c; Kahler and Strong, 2006; Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007; Proudfoot et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006; Teesson et al., 2002) and elsewhere (Shmulewitz et al., 2010), in emergency room patients in different countries (Borges et al., 2010; Cherpitel et al., 2010), and in adolescents (Gelhorn et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2006; Perron et al., 2010; Piontek et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2009b). Results are also consistent with two other studies in clinical samples (Langenbucher et al., 2004; Shand et al., 2011) that examined abuse and dependence criteria. The overwhelming weight of evidence is therefore that the unidimensional latent structure of SUD abuse and dependence criteria is consistent across populations, including clinical populations, supporting the combination of abuse and dependence in DSM-5 into a single SUD diagnosis.

In DSM-IV, substance-related legal problems pertain to legal consequences of intoxicated behavior (e.g., arrests for disorderly conduct, assault and battery; driving under the influence) rather than drug possession per se, so changes over time in drug possession laws and their enforcement are unlikely to have affected the utilityof the legal problems criterion. Substance-related legal problems were included in the earliest substance disorder diagnostic criteria because they occurred much more frequently among alcoholic than non-alcoholic prison inmates, the original study population for developing the criteria (Guze et al., 1962). Present clinical concerns about removing legal problems in DSM-5 include that this criterion may be more important for diagnosis in patients than in the general population. We did not find this to be the case. The legal problems criterion was rarely endorsed, was never the only criterion for any patient and in no case would have led to an additional DSM-5 SUD diagnosis among patients who had only one other criterion. In addition, while we did not have to drop legal problems to achieve unidimensionality of the SUD criteria as some studies did (Langenbucher et al., 2004; Saha et al., 2006), legal problems had low loadings on the unidimensional general substance use disorder factor and showed poor discrimination for each of the four substances. These results are consistent with a 1986 factor analytic study of alcohol rehabilitation patients (Svanum, 1986) that showed little relationship of alcohol-related legal problems to the other criteria, suggesting that the value of legal problems as a diagnostic criterion in clinical samples has not changed over the years. The present results contribute to the literature showing that legal problems are, at best, a weak or inconsistent indicator of the underlying substance use disorder latent construct and should be removed. Note that legal problems may be more important in specialized settings, where research and clinical planning should include separate assessments of this type of problem.

Although craving was proposed as an additional DSM-5 SUD criterion, latent variable analyses of craving with the other criteria is limited to studies of alcohol use disorders, three in the general population (Keyes et al., 2010) and one in emergency room patients (Cherpitel et al., 2010). Our study is consistent with the others in that craving fit well on the underlying unidimensional latent SUD variable and its addition did not change factor loadings for other criteria or overall model fit. However, adding craving alone to the DSM-IV dependence criteria did not significantly increase the total information for any of the four substances we examined, suggesting that it is largely redundant with these criteria. However, in contrast to previous studies showing that craving was a mid-to-high severity indicator (Cherpitel et al., 2010; Keyes et al., 2010), we found that craving was a mild-severity criterion, with intermediate-level discrimination compared to the other criteria. We further examined whether addition of craving as a criterion while holding the diagnostic threshold constant would add new cases, thus potentially casting a wider “diagnostic net”. For users of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin, this resulted in 5, 5, 7 and 2 additional cases, respectively, a trivial increase. Thus, results provide only mixed support, at best, for the addition of craving. Non-empirical reasons for adding craving to the DSM-5 SUD criteria are that ICD-10 criteria include craving, and thus its additionwould improve consistency between the two sets of diagnostic criteria (World Health Organization, 1993). Also, some consider craving to be a central feature of SUD and relapse (Goldstein and Volkow, 2002; O’Brien, 2005), although craving has not predicted relapse in all studies (Ahmadi et al., 2009; Garbutt et al., 2009). If craving is added to the DSM-5 SUD criteria, additional studies should examine it for redundancy, research that would in fact be valuable for all the diagnostic criteria.

In general, we found large discrimination parameters. This can be the result of analysing data from a population that largely consists of asymptomatic and highly symptomatic individuals (Reise and Waller, 2009). As shown in Fig. 1, this was the case in our sample, which was bi-modal for alcohol, cocaine and heroin criteria.

Consistent with the well-established understanding that clinical samples consist of more severe cases than those in the general population (Cohen and Cohen, 1984), severity of individual substance use disorder criteria (in IRT, indicated by infrequent occurrence) in this study was far lower than that found in non-clinical samples. Many severity estimates in this sample were around zero and even negative, indicating that even individuals below average in the sample on the latent (disorder) trait would have at least a 50% probability of experiencing the criterion.

Given the extent of DIF tests conducted by the number of patient characteristics and substances, relatively few instances of DIF were detected. However, where DIF occurred, it affected most or all of the criteria for that substance, rather than just a few criteria. DIF by race/ethnicity may occur in the cocaine criteria if cocaine and crack use are differentially associated with race/ethnicity, information unfortunately unavailable in our sample. DIF in the cannabis criteria may occur because of increased potency in available cannabis over time. This could lead to differences in the interest in or perception of this substance between younger and older patients, whose drug preferences become set at a relatively early age but during a different chronological period. We know of no explanation of the DIF by mood disorders for heroin criteria, but all of these issues merit investigation in future studies.

An unusual finding in this study was the high severity of the hazardous use criterion relative to the other criteria. While the prevalence of hazardous use was high in this clinical sample compared to general population adult samples, hazardous use had the poorest discrimination for all four substances, the lowest factor loading for cannabis, cocaine and heroin, and the second lowest factor loading for alcohol. Further, there was indication that a substantial proportion of its variance was captured by a dimension other than the general factor. Future work should consider whether this pattern is specific to the present study or more general to substance abuse treatment samples. In particular, since New York City has a widely used public transportation system, and the most common way to meet criteria for hazardous use is by driving after drinking or using drugs (Hasin and Paykin, 1999; Hasin et al., 1999; Keyes and Hasin, 2008), the result for hazardous use should be replicated in cities where patients are more likely to drive as their main method of transportation.

Study limitations are noted. As with all substance abuse studies, information is vulnerable to self-report bias and biological tests or informant reports were not obtained. However, since self-reported substance use tends to be accurate in the absence of sanctions (Magura et al., 1987), and since the patients reported a high prevalence of the SUD criteria, we doubt that self-report bias influenced the results. In addition, all clinical settings were located in the greater New York metropolitan area. Studies with greater geographic distribution would also be important. For example, if the NIDA Clinical Trials Network could adopt standard assessment of all the DSM-5 SUD criteria among participants in all trials, then a great deal of important research could be conducted with the resulting data. Strengths of our study included reliable assessments administered in a standardized way by experienced clinicians, a relatively large sample in which four substances could be examined, and state-of-the-art statistical procedures.

In conclusion, the present study in a large sample of substance abuse patients supports combining abuse and dependence criteria into one disorder in DSM-5 and eliminating legal problems. Empirical support for adding craving from this study is mixed. Many clinicians may welcome the addition of craving to the DSM-5 SUD criteria, an important consideration, but more research is needed to ensure that craving as a criterion is not simply redundant with the other criteria. To accomplish this, new datasets will need to be gathered that include craving as well as the other DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA018652, R01DA08409; Hasin), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (U01AA018111, K05AA014223; Hasin), the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Hasin, Wall) and Columbia University Department of Epidemiology (Fenton). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

Contributors

Deborah Hasin, Miriam Fenton, Cheryl Beseler, Jung Yeon Park and Melanie Wall had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Deborah Hasin. Analysis and interpretation of data: Cheryl Beseler, Jung Yeon Park, Melanie Wall. Statistical analysis: Cheryl Beseler, Jung Yeon Park, Melanie Wall. Obtained funding: Deborah Hasin. Study supervision: Deborah Hasin, Melanie Wall.

Conflict of interest

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Agrawal A, Heath AC, Lynskey MT. DSM-IV to DSM-5: the impact of proposed revisions on diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03517.x. doi:10.1111/j. 1360-0443.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Grant JD, Pergadia ML, Grucza R, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PA, Martin NG, Heath AC. Evidence for an interaction between age at first drink and genetic influences on DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009;33:2047–2056. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Liu X, Nunes E, Hasin DS. Suicide attempts in substance abusers: effects of major depression in relation to substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1600–1602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Liu X, Samet S, Nunes E, Waxman R, Hasin D. Postdischarge cannabis use and its relationship to cocaine, alcohol, and heroin use: a prospective study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1507–1514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi J, Kampman KM, Oslin DM, Pettinati HM, Dackis C, Sparkman T. Predictors of treatment outcome in outpatient cocaine and alcohol dependence treatment. Am. J. Addict. 2009;18:81–86. doi: 10.1080/10550490802545174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [accessed on 24.10.10];DSM-5 Development, Proposed Revision: Substance-Use Disorder. 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=431.

- American Psychiatric Association [accessed on 1.04.11];DSM-5 Development Frequently Asked Questions. 2011 http://www.dsm5.org/about/Pages/faq.aspx.

- Beseler CL, Hasin DS. Cannabis dimensionality: dependence, abuse and consumption. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Taylor LA, Leeman RF. An item-response theory analysis of DSM-IV alcohol-use disorder criteria and binge drinking in undergraduates. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:418–423. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpitel CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Rubio-Stipec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. The Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ, Rounsaville BJ, Babor TF. Coherence of the dependence syndrome in cocaine users. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1299–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Performance of a craving criterion in DSM alcohol use disorders. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:674–684. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’s illusion. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–1182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Saha TD, Conway KP, Grant BF. The role of cannabis use within a dimensional approach to cannabis use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ayala RJ. The Theory and Practice of Item Response Theory. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Rounsaville B. Construct validity of the abuse-dependence distinction as measured by DSM-IV criteria for different psychoactive substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995a;39:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01142-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Rounsaville B. Construct validity of the dependence syndrome as measured by DSM-IV for different psychoactive substances. Addiction. 1995b;90:1661–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901216618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, Osborne M, Gallop R, Barkenbus J, Grace K, Cody M, Flannery B, Kampov-Polevoy AB. Sweet liking phenotype, alcohol craving and response to naltrexone treatment in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:293–300. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Stallings M, Young S, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt J, Hopfer C, Crowley T. Toward DSM-V: an item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;47:1329–1339. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Factor and item-response analysis DSM-IV criteria for abuse of and dependence on cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants and opioids. Addiction. 2007;102:920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guze SB, Tuason VB, Gatfield PD, Stewart MA, Picken B. Psychiatric illness and crime with particular reference to alcoholism: a study of 223 criminals. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1962;134:512–521. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman CA, Gelhorn H, Crowley TJ, Sakai JT, Stallings M, Young SE, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ. Item response theory analysis of DSM-IV cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;47:165–173. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006a;101(Suppl. 1):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Liu X, Nunes E, McCloud S, Samet S, Endicott J. Effects of major depression on remission and relapse of substance dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:375–380. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. DSM-IV alcohol abuse: investigation in a sample of at-risk drinkers in the community. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999;60:181–187. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A, Endicott J, Grant B. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse: drunk drivers versus all others. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999;60:746–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Samet S, Nunes E, Meydan J, Matseoane K, Waxman R. Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance users assessed with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006b;163:689–696. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Commentary on Shand et al. (2011): opioid use disorder as a condition of graded severity, similar to other substance use disorders. Addiction. 2011;106:599–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Beseler CL. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse, dependence and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF, Harford TC, Endicott J. The drug dependence syndrome and related disabilities. Br. J. Addict. 1988;83:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychol. Med. 2006c;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hutten L. Some Empirical Evidence for Latent Trait Model Selection. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Boston, MA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR. A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the National Epidemiological Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Hayaki J, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. An item response analysis of the Alcohol Dependence Scale in treatment-seeking alcoholics. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003;64:127–136. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, O’Brien C. Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:166–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Socio-economic status and problem alcohol use: the positive relationship between income and the DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis. Addiction. 2008;103:1120–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychol. Med. 2010;12:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Vanyukov M, Dunn M, Tarter R. Item response theory modeling of substance use: an index based on 10 drug categories. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002;16:290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Babor TF, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Substanceuse disorders in DSM-III-R. Evidence for the dependence syndrome across different psychoactive substances. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;151:834–843. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.6.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Nichol PE, Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Using latent trait modeling to conceptualize an alcohol problems continuum. Psychol. Assess. 2004;16:107–119. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113:72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord F. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems. L. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Agrawal A. Psychometric properties of DSM assessments of illicit drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Psychol. Med. 2007;37:1345–1355. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Goldsmith D, Casriel C, Goldstein PJ, Lipton DS. The validity of methadone clients’ self-reported drug use. Int. J. Addict. 1987;22:727–749. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton L, Slade T, McBride O, Grove R, Teesson M. An evaluation of the proposed DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria using Australian national data. Addiction. 2011;106:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ. An IRT-based measure of alcohol trait severity and the role of traitedness in trait validity: a reanalysis of Project MATCH data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Langenbucher J, Labouvie EW. The generalizability of the dependence syndrome across substances: an examination of some properties of the proposed DSM-IV dependence criteria. Addiction. 1994;89:1105–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Rehm J, Ustun TB, Grant B, Chatterji S. Factor structures for DSM-IV substance disorder criteria endorsed by alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate users: results from the WHO reliability and validity study. Addiction. 1999;94:843–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Liu X, Samet S, Matseoane K, Hasin D. Independent versus substance-induced major depressive disorder in substance-dependent patients: observational study of course during follow-up. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:1561–1567. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP. Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1423–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron BE, Vaughn MG, Howard MO, Bohnert A, Guerrero E. Item response theory analysis of DSM-IV criteria for inhalant-use disorders in adolescents. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:607–614. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek D, Kraus L, Legleye S, Buhringer G. The validity of DSM-IV cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in adolescents and the value of additional cannabis use indicators. Addiction. 2011;106:1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot H, Baillie AJ, Teesson M. The structure of alcohol dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Morizot J, Hays RD. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Qual. Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl. 1):19–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Waller NG. Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009;5:27–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D. ltm: an R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory analyses. J. Stat. Softw. 2006;17:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Bryant K, Babor T, Kranzler H, Kadden R. Cross system agreement for substance use disorders: DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10. Addiction. 1993;88:337–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol. Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand FL, Slade T, Degenhardt L, Baillie A, Nelson EC. Opioid dependence latent structure: two classes with differing severity? Addiction. 2011;106:590–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Beseler C, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes KM, Wall MM, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, Spivak B, Weizman A, Frisch A, Grant BF, Hasin D. Nicotine dependence, abuse and craving: dimensionality in an Israeli sample. Addiction. 2011;106:1675–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Modeling relapse situations in the human laboratory. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KI, Hansen J, Tuit K, Kreek MJ. Effects of adrenal sensitivity, stress- and cue-induced craving, and anxiety on subsequent alcohol relapse and treatment outcomes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.49. epub ahead of print, PMID: 21536969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanum S. Alcohol-related problems and dependence: an elaboration and integration. Int. J. Addict. 1986;21:539–558. doi: 10.3109/10826088609083540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Lynskey M, Manor B, Baillie A. The structure of cannabis dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrens M, Serrano D, Astals M, Perez-Dominguez G, Martin-Santos R. Diagnosing comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance abusers: validity of the Spanish versions of the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:1231–1237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Berkman B, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, Barber JP, Blaine J, Salloum I, Moras K. The relationship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:1320–1325. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Pan JJ, Blazer DG, Tai B, Brooner RK, Stitzer ML, Patkar AA, Blaine JD. The construct and measurement equivalence of cocaine and opioid dependences: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009a;103:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Yang C, Reeve BB, Pan JJ, Blazer DG. Construct and differential item functioning in the assessment of prescription opioid use disorders among American adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009b;48:563–572. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819e3f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]