Abstract

A detailed description of treatment utilizing the Unified Protocol (UP), a transdiagnostic emotion-focused cognitive-behavioral treatment, is presented using a clinical case example treated during the most current phase of an ongoing randomized controlled trial of the UP. The implementation of the UP in its current, modular version is illustrated. A working case conceptualization is presented from the perspective of the UP drawing from theory and research that underlies current transdiagnostic approaches to treatment and consistent with recent dimensional classification proposals (Brown & Barlow, in press). Treatment is illustrated module-by-module describing how the principles of the UP were applied in the presented case.

The current paper is a companion to Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione, and Barlow (2010; this issue) and presents a detailed description of treatment utilizing the Unified Protocol (UP), a transdiagnostic emotion-focused cognitive-behavioral treatment designed to be applicable to the full range of anxiety and related disorders. Using a clinical case, we illustrate the application of the core treatment components of the current, modular version of this protocol, updated from earlier versions (Barlow et al., 2008). We focus on describing the development of key aspects of our treatment, specifically illustrating the clinical application of our approach and highlighting its utility across the emotional disorders.

The UP has undergone extensive development, beginning with group and moving to an individual delivery format, over the course of three separate open trials. Ellard and colleagues (2010; this issue) provide a detailed description of these modifications. The current version of the UP (Barlow, Boisseau, Ellard, Farchione, & Fairholme, 2009) consists of four core treatment modules that target key aspects of emotional processing and regulation of emotional experiences: (a) present-focused emotional awareness, (b) cognitive flexibility, (c) emotional avoidance and emotion-driven behaviors (d) interoceptive and situation-based emotion exposure. In addition, the protocol contains three other modules (psychoeducation, motivational enhancement, relapse prevention) consistent with standard cognitive-behavioral protocols. In our research applications of the UP, we have administered all seven modules in a fixed order to ensure that all patients receive each of the treatment components and to try to minimize any order effects that might influence the efficacy of the UP. Flexibility was built into the UP by allowing each of the modules to be completed within a preset range of sessions, thus allowing for individual differences in patient presentations. For instance, individuals with excessive, uncontrollable worry might benefit from an extended focus on nonjudgmental present-focused awareness (Module 3), whereas individuals with repetitive compulsive behaviors might benefit from prolonged practice and attention to emotional avoidance and emotion-driven behaviors (Module 5). Although the modules build upon one another and were designed to proceed sequentially, they can be flexibly administered depending on what seems clinically useful for a particular patient; however, further research for identifying rough guidelines or decision rules for such flexible application has not yet been completed. Treatment is typically conducted over the course of 12 to 18 sessions, with each session lasting approximately 50 to 60 minutes. On occasion, booster sessions are also administered following an initial course of treatment to assist patients in solidifying acquired emotion regulation skills through additional situational and interoceptive emotion exposure practice.

In the following case study, we present material intended to supplement and extend the description of the UP presented in Ellard et al. (2010) in this issue. We refer the reader to that manuscript for an overview of the research that informs the protocol’s development as well as initial outcome data from two open clinical trials. With the case that follows, we briefly present a patient who recently completed treatment using the most current version of our protocol (Barlow et al., 2009). This case provides a detailed overview of our treatment as it is currently conceived and delivered.

Case Example: Background and Presenting Problem

Matt1 is a 23-year-old Caucasian male who works as an administrative assistant. He completed high school and then went on to attend college, but left after 1 year because of difficulty with ritualistic behavior and uncued panic attacks. Matt presented to our Center, reporting difficulty with repetitive, intrusive thoughts and resultant compulsive behaviors, particularly around religion and morality. Similar to other individuals with scrupulosity, Matt imposed strict moral standards upon himself and was hypervigilant to the possibility of committing a moral or religious sin. Thus, any thought or action that did not meet his standards was accompanied by guilt and resulted in compulsive acts to correct that specific thought or action. For instance, if he viewed an image of Jesus (or another religious figure) in a way he found irreverent or otherwise unacceptable, he would engage in tapping rituals; if he thought about a woman in a sexual manner he deemed inappropriate, he would repeat to himself, “No, I didn’t think that.” Matt also struggled with moral thought-action fusion, believing that intrusive, blasphemous, or sexually immoral thoughts were as reprehensible as committing the act itself. Sadly, his scrupulosity made him unable to sustain a romantic relationship, as he would quickly end the relationship after having “impure,” blasphemous images (e.g., images of having sexual intercourse on a church alter). He believed these thoughts were not only a sin against God, but also a prediction of the negative things that would happen in the future should he maintain the relationship.

In addition to his obsessions around religion, Matt also reported a pathological need to prevent harm from coming to others. He was concerned that if he did not perform specific rituals, he or others close to him would contract an illness, become physically or mentally “deformed,” or be otherwise harmed. As a result, Matt engaged in a variety of rituals that served to temporarily ameliorate his anxiety or, in his words, his feelings of “doom,” some of which included: (a) tapping his fingers in a right-left symmetrical pattern, (b) tilting his head, (c) repeating certain phrases, (d) scratching a part of his body, and (e) checking his own food and the food of significant others for signs of contamination or perceived safety risk (e.g., undercooked or raw).

In addition to the constellation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, Matt also experienced difficulty with recurrent, unexpected panic attacks, which caused him to avoid situations such as local and long-distance driving, riding in a car, going to malls, using public transportation, going across bridges, being out of town, going to movie theaters or restaurants, riding on elevators, and going through tunnels. During these panic attacks, which were characterized by palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, hot flushes, and a fear of doing something uncontrolled, Matt would become afraid that he would pass out or permanently stop breathing. He reported that the panic contributed to his dropping out of college, made him unable to pursue a career of his choosing, and occasionally left him housebound.

He also worried excessively about his social/interpersonal relationships, particularly around maintaining friendships, his occupational future, his own health, and the long-term health of other people. He described physical symptoms associated with his worry, including restlessness, difficulty concentrating, and difficulty falling or staying asleep. Based on the initial assessment at our Center using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV-L; DiNardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994), Matt was assigned co-principal (equally severe) diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and panic disorder with agoraphobia (PDA). An additional (somewhat less severe) comorbid diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was also assigned to capture his excessive worry, which he experienced as difficult to control, separate from the OCD and PDA, and predated his difficulties with OCD and PDA. A thorough assessment for other Axis I disorders was completed, including unipolar and bipolar mood disorder, but no others were endorsed at a clinically significant level.

Measures

In addition to the ADIS-IV, Matt also completed a battery of self-report questionnaires designed to assess both diagnosis-specific and general symptom change. Full description of the battery can be found in Ellard et al. (2010). Here, we report on measures relevant to Matt’s case including: Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990; Steer, Ranieri, Beck, & Clark, 1993); Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); Panic Disorder Severity Scale–Self Report Version (PDSS-SR; Houck, Spiegel, Shear, & Rucci, 2002); Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Marks, 1986); Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale–Self Report Version (Y-BOCS-SR; Goodman et al., 1989; Steketee, Frost & Bogart, 1996).

Unified Case Conceptualization

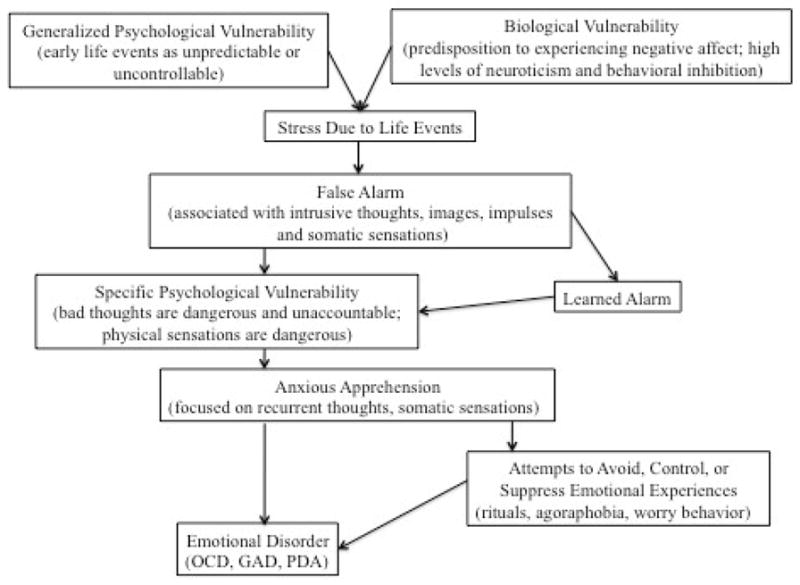

From a unified perspective, case conceptualization focuses on the ways in which patients process and cope with emotional experiences, identifying common patterns that cut across diagnosis-specific treatment manifestations (see Figure 1). From this perspective, Matt exhibited a predisposition to experiencing persistent, intense negative affect, as evidenced by elevated scores on measures of neuroticism, and behavioral inhibition, as evidenced by excessive, difficult-to-control worry about interpersonal relationships, family, and work (GAD in DSM-IV-TR) (cf. Brown & Barlow, in press). Most frequently, this negative affect occurred in response to or was primarily focused on two separate areas: (a) intrusive, distressing thoughts about contamination and blasphemy (OCD), and (b) autonomic surges or heightened physiological arousal (PDA). Through the process of interoceptive conditioning (Barlow, 2002; Bouton, Mineka, & Barlow, 2001), symptoms of physiological arousal can themselves become associated with intense, uncontrollable emotional experiences and ultimately serve as additional cues of threat or danger. Matt judged this persistent, intense negative affect as unacceptable, which led to repeated attempts to avoid, control, and/or suppress his emotional experiences. For example, Matt’s performance of tapping rituals were attempts to control negative affect associated with his intrusive thoughts and his overt behavioral avoidance of situations (such as going over bridges and driving long distances) were attempts to decrease physiological arousal or the probability of experiencing an autonomic surge. These repeated attempts at avoiding his emotions were largely unsuccessful and resulted in more frequent negative emotion, ultimately serving to reinforce the emotion-provoking nature of the various stimuli. Thus, from a UP perspective, the judgments placed on the initial emotional responses as well as the attempts to modify or control the emotions themselves are both the targets for intervention. Through the use of seven treatment modules, the UP is designed to help patients learn how to confront and experience uncomfortable emotions and respond to them in more adaptive ways.

Figure 1.

Unified Protocol model of the origin of emotional disorders.

Module 1: Psychoeducation and Treatment Rationale

The UP begins with gathering a detailed functional assessment about the patient’s presenting complaint, specifically focusing on the emotions experienced on a daily basis, how those emotions might be interfering with patient functioning, as well as any strategies the patient uses to manage these emotions.

THERAPIST: I want to get a sense of what you’re struggling with and what’s bringing you in.

MATT: Just fear in general. Being in constant worry. Premeditated or random panic attacks, like sitting at a red light or in a crowd. I absolutely can’t travel or be away from home. Even when I am in places all I can think about is fainting or losing control. Lately the panic attacks have been taking control. I mean...they have always had control because I’ve basically modified my life to the point where I don’t travel. I don’t go in situations that make me anxious where they can happen.

THERAPIST: Are you aware of any other emotions? I definitely hear there’s some fear, some anxiety.

MATT: Guilt. It’s not just panic attacks, but I’m very obsessive-compulsive. I’ve got this very bad fear. It’s not really a fear.…It’s more like I have to think that everybody’s equal. I can’t think higher of myself than anyone else, then I will become really ugly. So I say we are all equally beautiful and we are all created by the same God. And I feel like I’ll have to say it or else.

THERAPIST: Or else?

MATT: I’m doomed. I just live an overall life of fear. Just 24/7 fear. I woke up today…I started to do things with my pillow. I had to roll over a certain way. I’m constantly doing rituals. If I am not panicking I am doing rituals. I cannot remember the last time I just sat down and watched TV without doing something with the remote or standing up or sitting down. I can’t even remember the last time I had a few hours of peace.

After gaining an understanding of the presenting problem, the therapist presents the treatment rationale and helps the patient gain an understanding of the adaptive nature and function of emotions. Treatment is presented as a way to help patients become more aware of the full range of their emotional experiences, learn how to confront and experience uncomfortable emotions, and how to respond to those emotions in more adaptive ways. While earlier versions of our protocol focused primarily on negative emotions, we now emphasize that positive emotions may also be experienced as uncomfortable or threatening. The therapist helps the patient start to recognize that even the emotions he or she experiences as dangerous or uncomfortable have adaptive functional roles. Through a discussion of several different discrete emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety, sadness, anger, etc.), the therapist presents emotions as tools that provide information about the environment and help motivate us to behave in certain ways. The term emotion-driven behaviors (EDBs), defined as behaviors driven by the height of the emotion itself, is introduced for the first time and provides the foundation for later discussion. Below, the therapist explores some key emotions with Matt, illustrating their functional importance.

THERAPIST: What do you think the purpose of anxiety is? Why do we have it?

MATT: I don’t know. If I knew, I wouldn’t have it. Maybe to give us a sense of what’s safe or what’s right or what’s good for us. But what scares me doesn’t scare other people. I believe that everybody needs a certain amount of anxiety, you can’t be reckless. Maybe just to keep us in check.

THERAPIST: So in some ways…

MATT: Anxiety is a good thing?

THERAPIST: Yes, anxiety can be helpful. Why don’t we take another emotion: fear. Why do we have fear?

MATT: I don’t know. I guess that fear could be another good thing. I mean, no one wants to get hit by a car. I mean, people get fear when they see a car coming when they are crossing the street.

THERAPIST: What about sadness? Why do we need sadness?

MATT: To be human. It shows compassion. It shows we care. It shows our emotions, what can hurt us, what we care about. Just like me with my anxiety, some people have difficulty with sadness and depression to the point where it’s no longer a good thing.

THERAPIST: So one of the things that you have pointed out about emotions, is that we need emotions, we need all of them. Anxiety is a future-oriented emotion that allows us to prepare for and anticipate possible negative events. If you are not anxious at all, for example if you’re giving a presentation, then you might not prepare in a way that allows you to perform well. And then fear is nature’s alarm system and a protective mechanism to keep us from getting hurt. It allows us to jump out of the way of a car coming towards us. Sadness lets us know we have lost something that means something to us and allows us to gather the resources we need to mourn that loss. All emotions tell us important things about our environment and motivate us to behave in certain ways. We like to call these resulting emotional behaviors “emotion-driven behaviors,” or EDBs, because they are driven by the emotion itself.

After a general discussion of emotions, the therapist helps the patient start to identify the different parts of the emotional experience and introduces tools to help the patient gain a better understanding of his or her own emotional experiences. As such, the ABCs (antecedents, behaviors, and consequences) of emotional experience are presented, which helps the patient start to understand when, where, and why emotions are occurring, often helping to make intense emotional experiences more manageable. The three-component model of emotional experience is also presented and the therapist highlights the physiological, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of emotion that will become the targets of treatment in subsequent sessions.

The module concludes with a discussion of learned behaviors, illustrating that both the antecedents to and consequences of EDBs influence how individuals learn to respond to similar situations in the future. Through this discussion, the therapist begins to address how the patient’s attempts to manage uncomfortable emotions may be maladaptive in the long-term, even though they may provide more immediate short-term relief. Thus, the therapist emphasizes that repeatedly engaging in EDBs in order to prevent strong emotions from occurring, or to dampen their intensity, leads to a cycle in which EDBs become automatic, maladaptive, and insensitive to the context in which the behavior is occurring. In addition, the therapist makes it clear that it is the avoidance of emotion, not the emotion itself, that is getting in the way of the patient’s life.

MATT: The panic attacks are getting more severe. You would think avoiding them would help, but it hasn’t.

THERAPIST: The good news is that we can teach you to not avoid panic and to learn how to counter OCD. But it’s a little bit counterintuitive, not what you would usually think to do. It sounds like you think, “Here’s a bad emotion, I want to avoid it.” But ironically it’s fully experiencing that emotion that will allow you the freedom to live. So that’s why we start to look at these things and monitor them. Because like you said, sometimes it’s hard to know why we do things, even what emotions we may be experiencing. So let’s take an example from the previous week. When do you remember experiencing an intense emotion?

MATT: Well at work I was talking to my boss and I walked back to the room and I felt like I was going to pass out and I noticed a bad heartbeat. And I just couldn’t be there any more. I had to walk away. That was a rough one, it didn’t last very long. And I anticipated it too and I know he could see it because I looked really weird and walked away. I knew I was going to panic, so before I even got there I started scanning my body.

THERAPIST: So let’s try to break that down into the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. So the antecedent, or what precedes your emotion experience, is talking to your boss. The behaviors, or the response to the antecedent, are the physical sensations and preoccupation with how you looked to your boss. One of the short-term consequence is that you left the conversation prematurely, while a long-term consequence is that you might be more likely to avoid conversing with your boss in the future out of a fear of having a panic attack. But, even more by avoiding the intense feelings, the fear that comes with the heartbeat, you never get to learn that these feelings will eventually pass on their own. Ironically, all the things you do to get rid of those uncomfortable emotions never allow that new learning to occur.

Consistent with other cognitive-behavioral approaches, homework is assigned after each session, which allows for the practice and consolidation of skills taught in-session. Homework for this module is designed to help patients become more aware of their own emotional experiences. The patient is asked to break down an emotional experience that occurs during the week in accordance with the three-component model presented in session. In addition, the patient is asked to start monitoring their own emotional experiences, tracking the ABCs of any intense emotions. Given that patients come in with different abilities to assess and monitor emotions, the UP includes two different monitoring forms. The first, the Monitoring Emotional Reactions, asks the patient to begin monitoring the ABCs (antecedents, behaviors, and consequences) of their emotional experience. The second expands upon the more basic monitoring form, asking patients to begin monitoring the three components of emotional experiences by further breaking down the “behaviors” column to include thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Using these forms, the patient begins to build their awareness of their experiences and gather information about the ways in which they respond to their emotions.

Module 2: Motivational Enhancement

Module 2 draws on the work of Miller and Rollnick (1991, 2002) and Westra and Dozois (2006) and contains evidence-based strategies for motivation enhancement. These strategies are a new addition to the protocol from previous versions (e.g., Allen, McHugh, & Barlow, 2008; Barlow et al., 2008). These skills were included based on our observations that confronting and altering responses to uncomfortable emotions can be difficult for some patients, and that in order to reap the full benefits of treatment patients must be willing to engage in treatment. Basic techniques for motivation enhancement are incorporated throughout treatment, including increasing self-efficacy and developing discrepancy between the patient’s current situation and the patient’s ideal situation. For Matt, this meant discussing how his avoidance of strong emotion was negatively impacting his ability to form strong relationships with family and friends, pursue jobs of interest, or attend school. For homework, patients are asked to complete a Decisional Balance Worksheet, wherein the pros and cons of changing versus staying the same are weighed. Concepts and principles of motivational enhancement may be applied throughout treatment as necessary, and may be particularly helpful in increasing patient engagement during the emotion exposure phase of treatment.

Module 3: Emotional Awareness

The emotional awareness module is designed to help patients develop a nonjudgmental, present-focused approach to their emotional experiences to preclude emotional avoidance and enhance later emotion-focused exposure. In this module, “emotional awareness” is presented as being aware of both the emotional experience itself as well as the reactions to that emotional experience. As such, the therapist introduces the idea that it is not the emotions that are problematic, per se, but rather how they react to the emotion. Here again, the current version of our protocol (Barlow et al., 2009) emphasizes that patients can react negatively to positive emotions as well.

THERAPIST: We’ve talked a lot about these uncomfortable emotions you experience. I’m interested in knowing how you react to having those emotions. Often people respond to emotions by thinking things like, “I shouldn’t feel this way.” Do you ever find yourself doing that?

MATT: Well, I feel like I shouldn’t have panic, if that’s what you mean? I mean normal people don’t have panic. It’s not normal to have to leave places, to not be able to get on a bus or ride an elevator. I should be able to handle doing things that normal people do without being scared. I freak out for no good reason.

THERAPIST: So essentially, you judge how you’re feeling. You have a negative emotion and then tell yourself you’re not normal for having that emotion. What about positive emotions? Ever react negatively to those as well?

MATT: That’s the thing. Especially with the OCD. If I feel good, the OCD tells me that I’m being cocky or overconfident. I can’t think I should feel good all the time or that I should feel better than anyone else. And then, also, it’s like if I am feeling good then I’m not on the lookout enough. I’m vulnerable to getting sick or something bad happening. No, I know I’ll get sick.

THERAPIST: It seems like you judge having both negative and positive emotions.

MATT: No emotion is the way to go. Feelings suck.

THERAPIST: I understand where you are coming from, but perhaps it’s not the feelings themselves, but how you react to those feelings. The more we tell ourselves that having certain emotions are “bad” or that we are “bad” for having them, the more they linger. By becoming fixated on our reactions to our emotional experience, we prevent our emotions from following their natural course. The more you push emotions away and the more you get caught up in them by judging them, the more they intensify. You don’t get to see that emotions, if you let them, naturally ebb and flow. Even intense, uncomfortable emotions will gradually decrease on their own. So, what I want us to work on is teaching you how not to judge your emotional experience.

Next, the therapist introduces the importance of present-focused awareness in understanding emotional experiences and presents the idea that emotions often trigger past memories or thoughts about what may happen in the future. Becoming caught up in these memories and thoughts makes it difficult to view emotions in the context in which they are occurring. The protocol contains a therapist-guided, nonjudgmental, present-focused emotional awareness exercise that allows the patient to practice anchoring themselves in the present moment. Whereas prior versions of our protocol (see Allen et al., 2008) also contained a mindfulness exercise, in this version we have modified the exercise based upon our observations that patients often need more direct guidance when practicing the skill for the first time. Thus, the current version of the protocol includes a body scan exercise adapted from Segal, Williams, and Teasdale (2002), followed by an emotion-induction exercise used to help the patient practice nonjudgmental, present-focused awareness in the context of an emotional experience.

The homework in this module is designed to help patients continue to build emotional awareness. Patients are asked to repeat the emotion-induction exercise at home by listening to different songs and paying attention to the various emotions elicited as well as their reaction to those emotions. A homework form that helps the patient deliberately practice nonjudgmental, present-focused awareness supplements the mood-induction exercise. Patients are also instructed to engage in a daily exercise intended to condition their breath to serve as a cue for eliciting present-focused awareness. In this exercise, patients are instructed to focus their awareness on a sound or sensation in the environment and to pair this awareness with a deep breath.

Module 4: Cognitive Appraisal and Reappraisal

In Module 4, the first of the three components presented in Module 1 is discussed. Patients are taught to consider the role of maladaptive, automatic appraisals in emerging emotional experiences. As with earlier iterations of our protocol, the main goal of this module is to help patients develop more flexible thinking patterns. After defining cognitive appraisal, the therapist conducts an in-session exercise designed to illustrate the idea that many different appraisals of a given situation are possible, even when the specific aspects of the situation remain the same. In this exercise, the patient is presented with an ambiguous image (we use a card from the Thematic Apperception Test [TAT]; Morgan & Murray, 1935) they are instructed to view for approximately 30 seconds, and then asked to identify their initial or automatic appraisal before generating several alternative appraisals. The ambiguous picture exercise is also used to help patients understand the reciprocal relationship between thoughts and emotions. Through the use of Socratic questioning the therapist helps the patient identify core automatic appraisals that appear to drive their anxious and depressive behaviors. In the excerpt that follows, Matt worries about having a panic attack when entering a mall.

THERAPIST: So you were worried that if you entered the mall you’d have a panic attack. What specifically were you afraid might happen?

MATT: I’d get dizzy, my heart would start racing.

THERAPIST: And if those things happened?

MATT: I’d pass out.

THERAPIST: And what would happen if you passed out?

MATT: I don’t know…maybe I wouldn’t wake up, I’d die. Or even if I did wake up I’d get taken to the hospital.

THERAPIST: So one of the core anxious thoughts driving your anxious behavior is that you’d die, which would make anyone anxious or scared. And if you got taken to the hospital what would happen?

MATT: I hate the hospital. First there is the ambulance which is constantly used for sick people and you never know what those people have. And then there’s the hospital, which is filled with people with all sorts of diseases and things I don’t want.

THERAPIST: You’re afraid that if you faint in public you’ll end up in the hospital, which will cause you to contract a disease?

MATT: I guess that one comes back to death too. I mean I’m afraid that if the panic attack didn’t kill me then I would end up in the hospital where I would contract like AIDS or something else fatal.

From here, the therapist works with the patient to develop an adaptive strategy for evaluating and modifying anxious and negative thoughts. First, the therapist askes the patient to identify possible errors or “traps” in their thinking, including “jumping to conclusions” and “thinking the worst.” Then, similar to traditional cognitive therapy formats, the patient is taught reappraisal skills with the goal of increasing cognitive flexibility. The therapist introduces two reappraisal strategies that help the patient develop more realistic, evidence-based interpretations of emotional provoking situations and break patterns of emotional responding. The first, countering probability estimation, teaches the patient to examine evidence from a patient’s past experience and use that evidence to realistically examine the probability of an outcome happening. The second, decatastrophizing, assists the patient to identify his or her ability to cope, should the feared situation occur. Importantly, reappraisal is taught as antecedent-based strategy that alters the cognitive conditions under which patients encounter emotionally provoking stimuli. In going over patient-generated examples, the therapist emphasizes that the goal is not to eliminate all thoughts related to negative appraisals; rather, it is to allow multiple interpretations of a situation to coexist.

Homework specific to this module allows patients to practice identifying and evaluating automatic appraisals and helps them develop more flexible thinking patterns. While the material presented in the module is consistent with previous versions of our protocol, we now give patients an avoidance strategy checklist to complete before the start of the next module. Based on and modified from the Texas Safety Maneuvers Scale (Kamphuis & Telch, 1998), the Checklist of Emotional Avoidance Strategies (CEASE) helps patients begin to identify subtle ways they may attempt to avoid uncomfortable emotions. For Matt, that included behaviors such as sitting closer to exits to facilitate escape, seeking reassurance from family members, procrastinating on investigating career opportunities, or trying to selectively attend to certain parts of the environment.

Module 5: Countering EDBs and Emotional Avoidance

In this part of our treatment, the therapist begins to discuss the behavioral component of emotional experience and reintroduces the concept of EDBs, behaviors driven by emotions themselves. The therapist notes that while EDBs are often adaptive in certain situations (e.g., immediate danger triggers fear, which elicits an escape response), they become maladaptive when they occur indiscriminately or are inappropriate given the context of the situation (e.g., fear triggered by perceived danger associated with having a panic attack elicits the same escape response). Thus, the therapist works with the patient to identify maladaptive EDBs and helps the patient explore how engaging in those EDBs maintain disordered emotional experiences. For Matt, EDBs were often compulsive behaviors he engaged in reaction to the distress caused by his obsessive thoughts about religion, morals, and, in some cases, fears of contamination:

THERAPIST: In thinking about the past week, were there any behaviors you feel like your emotions drove you to perform?

MATT: I guess all of the tapping, tilting rituals. Like you know how if I see an image of Jesus and I don’t look at it the right way? Well I feel doomed if I don’t tap my fingers, or tilt my head or repeat things to myself. And, it’s not just once—it’s until I get it right.

THERAPIST: And how do you feel when you get it right?

MATT: I don’t feel doomed anymore, unless there is some other trigger and it starts the whole process again.

THERAPIST: It seems for the moment that you feel a little better after doing the rituals, better than that doomed feeling, but that feeling better doesn’t last. What are some others?

MATT: You mean like leaving a situation?

THERAPIST: Right. Like when you leave a situation when you’re feeling panicky and you start to feel dizzy or you’re heart starts beating fast. How does it feel to escape that situation?

MATT: I feel better. I don’t feel like I am going to pass out anymore.

THERAPIST: So, like the tapping, you feel better at least temporary. But one of the things that you pointed out with the tapping is that the feelings of doom return. What happens the next time you try to enter a situation you’ve left?

MATT: Well, I probably won’t go into that situation again. I start to feel panicky even thinking about it.

THERAPIST: See that’s the thing about EDBs: the tapping or the escape, while they provide short-term relief, in the long-term they maintain or heighten the emotion. When you engage in these behaviors and feel better temporarily, it strengthens their association so that the next time you feel doomed or panicky you do the thing that has made you feel better—you tap or you escape.

A second focus of this module is helping patients recognize the ways in which they avoid their emotions. Unlike EDBs, which happen in response to an emotion that has already been triggered, emotional avoidance generally happens before an emotion has occurred. More of a temporal distinction than functional one, emotional avoidance strategies as with EDBs can become powerful habits that perpetuate maladaptive patterns of emotional responding. Here the therapist focuses on helping the patient recognize how they avoid experiencing emotions or modify situations to dampen the intensity of them. As with previous versions of our protocol, the therapist introduces three types of emotional avoidance strategies: subtle behavioral avoidance (e.g., choosing a seat based on proximity to the door in order to more easily escape in the case of a panic attack), cognitive avoidance (e.g., using distraction to prevent negative thoughts and worries), and safety signals (e.g., carrying talismans or item such as anti-anxiety medication that would be calming in times of intense distress). To help patients understand how and why emotional avoidance strategies fail, the therapist conducts a simplified version of Wegner’s (1989) “white bear” experiment:

THERAPIST: For this exercise I want you to describe a memory or situation that is especially emotional for you.

MATT: You know when I got sick a few weeks back with the stomach flu and I was throwing up all the time? I know we’ve already talked about this, but it’s the one that sticks out. Can I use that?

THERAPIST: Of course, from what you told me that would be a good situation to choose. Can you take me through what happened again and what emotions you experienced?

MATT: I just remember being so afraid. There I was puking in the toilet and doing constant rituals because I was scared that something would be seriously wrong with my health if I didn’t. It wasn’t just the fear. I was so distraught and disgusted with myself because I couldn’t stop doing them, not even for a minute. One time I ended up throwing up on myself because completing a ritual was more important than getting to the bathroom. So there I was covered in my own vomit, ritualizing. I just felt horrible, you know? Like I’ll never beat this.

THERAPIST: So I want you, using whatever strategy you can, to not think about that experience and I’ll tell you when to stop.

THERAPIST: [after about 30 seconds] How successful were you in keeping that memory and those emotions away?

MATT: Well, first I tried to think about the pictures on the wall and then I tried to think about what I’m doing later tonight, but I had to keep telling myself to think about something else.

THERAPIST: So it keeps creeping in?

MATT: Yeah.

THERAPIST: That’s what happens when we try to avoid thinking about things, particularly when we try to avoid certain emotions. They keep popping back in. In telling yourself not to think about something, you have to think about it on some level. This is why avoiding emotions doesn’t work and why you’ve seen that trying to distract yourself from thoughts, like the OCD thoughts, doesn’t work.

After discussing EDBs and emotional avoidance the therapist introduces the concept of “acting opposite” to EDBs as a way to break the cycle of emotional responding. The therapist helps the patient generate opposite actions, or to implement incompatible behaviors in order to alter their emotional experiences. For example, Matt practiced walking in the middle of a crowd instead of leaving crowded areas and eating food he believed was contaminated instead of throwing it away. Homework during this module helps the patient identify types of emotional avoidance in accordance with the strategies presented in session. The patient also starts to monitor maladaptive EDBs and begin implementing opposite actions.

Module 6: Interoceptive and Situational Exposures

This module focuses on exposure to both internal and external emotional triggers, which affords the patient opportunities to increase their tolerance of emotions and allows for new contextual learning to occur. The therapist introduces the third component of emotional experience, physical sensations, and describes how physical sensations contribute to overall emotional experience. The therapist works through a series of interoceptive exposures—breathing through a thin straw, running in place, and hyperventilating—designed to elicit emotion through physical activation. In this way, the patient begins to both identify and tolerate physiological aspects of emotional experience. After completing each exercise the patient rates the distress, intensity, and similarity of the experience to the physical sensations they typically experience with strong emotions. Initially, when asked to hyperventilate in session, Matt stopped the exposure prematurely and made several attempts to avoid the emotions provoked by experiencing the sensations.

MATT: I had to stop. I was too lightheaded to continue.

THERAPIST: What do you think would have happened had you continued?

MATT: I was already on the edge, I felt myself beginning to panic. If I had continued I really would have passed out or completely lost it.

THERAPIST: What would be the worst thing that would happen if you passed out? How would you cope with it?

MATT: I understand. I remember all of that thinking stuff we talked about earlier. I know I’ve never passed out and if I did I’d be okay. But losing it is another story.

THERAPIST: Losing it? What would that look like?

MATT: I don’t know.

THERAPIST: Well sometimes what makes things hard is not examining what it is you fear. If it’s a big cloud of “something bad” then it’s much harder to challenge. It’s a much harder thing to test out. So let’s talk about what losing it means.

MATT: Well it could be anything. Like standing up and running out of your office screaming. Maybe I’ll start talking nonsense or not be able to speak real words.

THERAPIST: So now at least we have things we can test.

Interoceptive exposures continue in-session until the patient is able to complete the exercise without any attempts to avoid the emotions evoked. If the therapist believes that formal, repeated practice will be of benefit to the patient, the patient is assigned to complete the exercise several times a day until their distress decreases. After struggling through the interoceptive exposures through the first session and completing the exposures for homework, subsequent sessions with Matt looked quite different.

THERAPIST: Like last time, I want to try some of those exercises that bring on those physical sensations. I know towards the end of the session that spinning in place was really difficult because it was most similar to your experience of panic—so let’s try that one.

[Matt spins in a circle while standing for 30 seconds.]

THERAPIST: What sensations are you experiencing?

MATT: Well I’m dizzy, more dizzy than the last time and it’s not as bad as I thought it would be. I still don’t know how I’d react if I felt this way out in public. You know, I thought you were full of crap when you first suggested this, but it does seem to get better. And, I haven’t run out of the room screaming or anything.

Similar to interoceptive exposures, situationally based exposures increase emotional tolerance, allow for the adoption of adaptive emotion-regulation strategies, and introduce new contextual experiences. Here, the focus of the exposures is the emotional experience itself that arises in situations and can take the form of in-session, imaginal, and in vivo exposures. While the way we present and conduct exposure remains the same as previous iterations of our protocol, we now include exposure to positive emotions as well, as those emotions can also be experienced as uncomfortable. The therapist helps the patient design an emotional avoidance hierarchy that contains a range of situations so that exposures can proceed in a graded fashion. In addition to exposures conducted in-session, the therapist typically assigns three exposures for homework, beginning with the bottom of the patient’s hierarchy. Prior to engaging in these exposures patients are asked to rate their anticipatory distress and identify and reevaluate their automatic appraisals. After completing the task patients describe the emotions they experienced during the task and any attempts to distract themselves from their emotions as well as their distress during the task. One of the early exposures Matt completed was taking a cab around the city, something that he had not done in alone in almost a year. One of the more difficult session exposures for Matt was an in-session exposure that involved looking at a religious image without engaging in compulsions.

THERAPIST: I am going to show you an image. The goal of this exposure is to fully experience any emotions that the image brings without doing anything to avoid or lessen the intensity of those emotions. That means not distracting yourself or engaging in compulsions.

THERAPIST: [After 1 minute] What emotions did you experience?

MATT: I looked at it and felt doomed…horrible.

THERAPIST: So that’s why you tilted your head?

MATT: So you noticed? Yeah, I did a ritual because when I saw the image I thought, “That looks fake,” which is sinful because I didn’t give it the respect it deserves. So I had to do a ritual or I’d be doomed or cursed.

THERAPIST: I definitely could tell that the image brought up a lot uncomfortable emotions. But remember what we’ve talked about happens when you avoid those tough emotions?

MATT: It makes things worse in the long run. It makes the emotions worse too.

THERAPIST: Exactly. That’s why I want to repeat the exposure again.

Module 7: Conclusion and Relapse Prevention

Treatment in the protocol concludes with a discussion of the patient’s progress. All major treatment components are reviewed, including the importance of nonjudgmental present-focused awareness, cognitive flexibility, modifying EDBs, and preventing emotional avoidance. Patients are encouraged to continue informal emotion exposures. The treatment concludes with a discussion of ways to maintain treatment gains. Patients are reminded that a periodic increase in symptoms does not automatically indicate relapse, and that they can apply these same skills learned throughout treatment to new situations that may arise in the future.

Clinical Outcomes

Matt responded well to treatment using the UP, evidenced by decreased diagnostic severity across all disorders and improved psychosocial functioning. For Matt, that included reducing the time spent on obsessions and compulsions by over 60%, entering situations that he had been avoiding for years (e.g., public transportation, malls, crowds, concert halls, arenas), and improved interpersonal relationships (WSAS). At posttreatment2 Matt achieved responder status on principal and comorbid diagnoses evidencing a 30% or greater change in two of three broad assessment categories: ADIS-IV clinical severity, WSAS, or diagnosis-specific measures (see Ellard et al., 2010; this issue). While Matt did not meet criteria for high end-state functioning (see Ellard et al.) because his OCD and PDA were still clinical at posttreatment, both diagnoses were rated as less severe by independent raters using the ADIS-IV. These results were also supported by self-report questionnaires. Namely, his score on the PDSS-SR fell from 14 to 7, placing him below the clinical cut-off suggested by Shear et al. (2001) and his score on the Y-BOCS-SR decreased from 28 (severe) to 19 (moderate). Matt’s GAD also improved with treatment, and he no longer met ADIS-IV diagnostic criteria for that disorder post-treatment. Matt’s score the BDI remained in the minimal range at post-treatment and his score on the BAI decreased from 26 (severe) to 15 (mild).

Conclusion

One of the key advantages of the UP is its ability to be easily adapted and administered to a wide range of different presenting problems. In the case of Matt, the UP was able to target three separate problem areas, covering symptoms of OCD, PDA, and GAD within one single 12 to 18 session protocol. Using traditional single-disorder protocols, treatment would likely have taken significantly longer to address the various key features of Matt’s presenting problem. Although research suggests that comorbid conditions do show some improvement with treatment of a single principal disorder (e.g., Craske et al., 2007), the mechanisms involved in this finding are not yet well understood or adequately accounted for within single-disorder protocols. In capitalizing on the commonalities across these various presenting problems, the UP targets each of these ostensibly separate presenting problems simultaneously using a common language and set of treatment principles. We believe that this facilitates patient improvement by helping them to identify the similarities among their various presenting problems and can ultimately help to improve the generalization process noted in other single-disorder protocol studies (e.g., Craske et al.).

The development of the UP has grown naturally out of, and dovetails nicely with, parallel investigations into the nature and classification of anxiety and mood disorders (Brown, 2007; Brown et al., 1998; Brown & Barlow, in press; Brown & McNiff, 2009). A recent proposal by Brown and Barlow (in press) outlines how different DSM-IV disorders across the range of anxiety and mood disorder categories can be accommodated within a single dimensional classification system, providing targets for clinical change that cut across disorders that is fully compatible with the UP. The UP model of the origins of emotional disorders (see Figure 1), when used in conjunction with the dimensional classification system proposed by Brown and Barlow (in press), provides a flexible approach to diagnosis and treatment.

While Matt did not present with a comorbid mood disorder, we have successfully applied the UP to several cases where comorbid depression was part of the clinical presentation (see Ellard et al., 2010; this issue). Core modules within the UP can be directed towards addressing symptoms of depression, including negative thoughts and rumination; amotivation and social withdrawal; and physical sensations of heaviness and fatigue. For example, Module 3 is applied to increase the patient’s awareness of how depressive thoughts, rumination, behavioral withdrawal, and feelings of fatigue interact to exacerbate low mood. Patients are encouraged to use mindfulness and present-focused awareness exercises to break the cycle of rumination and anchor their mood within the current context (e.g., “I feel low today”), rather than fueling their low mood through ruminations about past events or worries about the future (e.g., “My depression is back, it’s going to be as bad as before, I’ll never get out of this”). As in traditional cognitive therapy for depression (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), Module 4 is applied to directly target automatic negative thoughts and core beliefs that serve to fuel low mood. Module 5 is used to heighten the patient’s awareness of the ways in which specific EDBs like social withdrawal are both triggered by and reinforce low mood. In our experience using the UP for depression, we have encouraged patients to counter these EDBs through behavioral activation and an increase in pleasant activities. Through Module 5, patients are also made aware of how avoidance of situations and activities serves to increase negative mood. For example, avoiding a social gathering as a result of low mood may serve to increase the patient’s sense of isolation, triggering rumination and reducing the possibility of experiencing positive emotions. Module 6 is applied to increase the patient’s awareness of how physical sensations, such as fatigue and heaviness, contribute to low mood. Whereas interoceptive exercises aimed at directly eliciting these symptoms presents an ongoing challenge, in our experience utilizing interoceptive exercise to mimic the physical sensations associated with other emotions such as fear and anxiety have been powerful tools to illustrate the ways in which physical sensations contribute to ongoing emotional experiences, which in turn can be generalized to specific physical sensations experienced during depressive episodes. Finally, emotion exposures are tailored to specifically target triggers for low mood. For example, writing exercises can be used as exposures to core beliefs, and situational exposures can be used to increase the patient’s exposure to positive emotions.

Preliminary evidence from open trials of the UP suggests that it is both feasible and effective for the treatment of a wide range of diagnoses and presenting problems (see Ellard et al., 2010; this issue). To date, we have used the UP to successfully treat a diverse and varied range of anxiety and mood diagnoses, including GAD, OCD, PDA, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, dysthymia, as well as hypochondriasis. The efficacy of the UP in treating a range of anxiety disorders is currently being formally examined in an ongoing randomized controlled trial at our Center. Once initial efficacy has been empirically demonstrated, it will be important for future investigations to examine the boundaries or limits of the applicability of the UP. Nevertheless, as illustrated by the case of “Matt,” early indications suggest the UP may provide an effective approach for addressing common underlying processes that cut across anxiety and mood disorders, simultaneously addressing multiple disorders and thereby providing a more parsimonious option for the treatment of a range of co-occurring diagnoses.

Footnotes

Name and identifying details have been changed to protect anonymity.

Only posttreatment data are available as patient is still in the follow-up period and a follow-up assessment has not yet been completed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen LB, McHugh RK, Barlow DH. Emotional disorders: A unified protocol. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 216–249. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. 4. London: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behaviour Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Boisseau CL, Ehrenreich JT, Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, et al. Unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders. 2008 Unpublished treatment manual. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Boisseau CL, Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP. Unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders: Modular Version 3.0. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. Unpublished treatment manual. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Mineka S, Barlow DH. A modern learning-theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder. Psychological Review. 2001;108:4–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of tempera-ment and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:313–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Diagnostic comorbidity in panic disorder: Effect on treatment outcome and course of comorbid diagnoses following treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:408–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, McNiff J. Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Farchione TJ, Allen LB, Barrios V, Stoyanova M, Rose R. Cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder and comorbidity: More of the same or less of more? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1095–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione T, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS): I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis JH, Telch MJ. Assessment of strategies to manage or avoid perceived threats among panic disorder patients: The Texas Safety Maneuvers Scale (TSMS) Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 1998;5:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Marks I. Behavioural psychotherapy. Bristol, U.K: John Wright; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CD, Murray HA. A method of investigating fantasies: The Thematic Ap-perception Test. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 1935;34:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Sholomskas DE, Barlow DH, Gorman JM, et al. Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) Pittsburgh, PA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Rucci P, Williams J, Frank E, Grochocinski V, Vander Bilt J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale: Replication and extension. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2001;35:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost R, Bogart K. The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: Interview versus self-report. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM. White bears and other unwanted thoughts. New York: Viking/Penguin; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozois DJA. Preparing clients for cognitive behavioural therapy: A randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:481–498. [Google Scholar]